Abstract

Families raising children with autism face financial planning challenges, particularly in countries with limited social support. Using data from 497 Chinese families, this study examined saving behavior for children with autism. Results showed that only 46% of families had saved for their children’s future, with an average of 104,000 RMB. Key predictors of saving probability included debt (β = −0.02, p < 0.05), financial skills (β = 0.10, p < 0.01), financial attitude (β = 0.09, p < 0.05), and subjective financial well-being (β = 0.09, p < 0.05). Factors associated with savings amount were assets (β = 0.12, p < 0.05), debt (β = −0.07, p < 0.05), financial attitude (β = 0.57, p < 0.001), and subjective financial well-being (β = 0.56, p < 0.001). Findings highlight the need for financial capability interventions and policy support to help families manage debt, build assets, and improve long-term financial planning.

1. Introduction

Systematic reviews have shown that the global prevalence of autism, while varying across regions and studies, ranged from 0.4% (Salari et al. 2022) to 1% worldwide (Solmi et al. 2022; Zeidan et al. 2022). One estimate suggested a 39% increase in the total population of autism from 20 million in 1990 to 28 million in 2019 (Solmi et al. 2022). Similar prevalence rates of autism have been found in China. For example, Jiang et al. (2024) reported a prevalence rate of 0.7% based on a review of 21 studies. However, another study targeting children aged 6 to 12 years found a lower prevalence rate of 0.29% in China. Recognized as a global public health challenge, autism affects a significant population of families in China and worldwide (Wallace et al. 2012; Zhou et al. 2022, 2023).

Autism is a lifelong neurodevelopmental disorder that imposes a significant economic burden on families and society. Individuals with autism often experience high levels of anxiety, stress, and isolation, while their families face substantial financial challenges (Bozkurt et al. 2019; Cohrs and Leslie 2017; Gordon-Lipkin et al. 2018). For example, in the United States, the direct and indirect costs of caring for children and adults with autism in 2015 were estimated at USD 268.3 billion, exceeding the costs of stroke and hypertension. Overall, the annual cost of education, healthcare, and other lifelong services for an autistic patient varies from USD 1.4 million to USD 2.4 million (Leigh and Du 2015; Durkin et al. 2017). This economic burden is particularly severe in countries and societies with limited social support and services for individuals with autism, such as China (Zhou et al. 2022). In the Chinese context, families face a significant “service gap.” While government support for early rehabilitation (typically for children aged 0–6) has expanded, public services for school-aged children and adults with autism remain severely underdeveloped (Zhou et al. 2022, 2023). Consequently, families are often forced to fill this gap through the private market, bearing the full cost of lifelong care, housing, and medical needs (Zhou et al. 2022, 2023). The financial demands associated with autism necessitate substantial economic and financial investments from families and society to provide essential services in areas such as healthcare, rehabilitation, education, housing, and employment.

Given its lifelong nature, long-term financial planning and asset building for children with autism are particularly crucial. Drawing on the Financial Capability and Asset Building (FCAB) framework, saving and asset building have been considered significant determinants of individual and family well-being beyond income and consumption (Sherraden 1991; Sherraden et al. 2013). They reflect the optimization of decision-making within families and society in balancing the current and future economic resource needs of individuals with autism. Savings, investments, and other financial preparations undertaken by families for the long-term development of their children with autism are especially important for disadvantaged families, particularly those living in societies with limited social support policies for this population. Faced with competing demands for financial resources between current and future needs of individuals with autism, these families often have more systemic barriers, fewer opportunities, and limited family economic resources, making it more challenging for them to plan financially for the future of children with autism.

However, while the questions of whether and how families plan financially for their children with autism in the long term are of paramount importance, they remain under-researched in the autism literature. Most research focuses on the current economic burden of autism-related expenses, the financial stress experienced by families caring for a member with autism, and the financial well-being of individuals with autism (Cai et al. 2024; Chasson et al. 2007; Ganz 2007; Sharpe and Baker 2011; Zhou et al. 2022). Few studies have taken a future perspective, and explored families’ savings, financial planning, and long-term preparations for individuals with autism (Cai et al. 2023). To fill this knowledge gap, this study utilized survey data collected from nearly 500 families raising a child with autism in China to examine their family savings for their children with autism.

Specifically, we focused on the associations between the probability and amount of family savings for children with autism and family financial status and demographic characteristics. This study aims to address three specific research questions: (1) What is the prevalence of family savings for the future of children with autism in China, and what is the typical amount saved? (2) How is each household finance factor (e.g., income, assets, debt, financial capability) individually associated with the probability and amount of family savings? (3) How are these household finance factors associated with family savings when accounting for the concurrent influence of other economic and demographic characteristics? The findings of this study will help us further understand the financial decisions of these families regarding savings and investments for their children’s future development. These findings will also inform public health, social policy, and social service responses to improve the long-term financial security of individuals with autism and their families worldwide.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data and Sample

The data were collected as part of the 2023 Family Financial Health Project, a nonprofit initiative by YiBao in China, aiming to improve the financial well-being of families raising children with autism through financial education, counseling, and asset building. The data were obtained from a pre-service intake survey completed by parents or guardians, based on YiBao’s nationwide financial education network. Informed consent was obtained from all participants via a cover letter accompanying the survey, which detailed the study’s purpose and data protection measures; a copy of this cover letter has been submitted to the journal editors. The survey collected information on demographics, children’s disabilities and health, respondents’ financial capabilities, family financial status, and other relevant factors.

To ensure national representativeness, the project categorized the 34 provinces of China into five regions (East, South, Central, West, and North). A stratified sampling method was employed, with researchers inviting 150 parents of children with autism from each region (totaling 750 potential participants). At least half of the provinces in each region were included in the sampling frame to reflect geographic diversity. Ultimately, 539 parents from 12 provinces across five regions completed the survey, with a final analytical sample of 497 respondents after excluding duplicate and incomplete responses. The data were fully de-identified by YiBao before being shared with the researchers, ensuring participant confidentiality.

This study strictly adhered to ethical standards to protect the rights and well-being of all participants. Ethical approval for the project was granted by YiBao’s Institutional Review Board (IRB), which reviewed the study protocols to ensure compliance with international ethical guidelines, including the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before survey completion, and respondents were fully informed about the purpose of the study and the intended use of their data. The survey was carefully designed to minimize any risks to participants, and no interventions or procedures were included that could cause potential physical or psychological harm.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Dependent Variables

Savings for children with autism. A single survey question asked respondents whether families had savings or investment for their children with autism (1 = Yes and 0 = No). For families with savings, the savings amount was collected in increments of 1000 RMB (approximately USD 140). A savings amount variable was constructed, assigning a value of “0” to families without savings. Preliminary analysis of the savings amount variable revealed extreme positive skewness (15.81) and kurtosis (298.86), indicating a distribution with a substantial right tail and significant outliers. To address this deviation from normality and accommodate zero values (i.e., families with no savings), we recoded zero values to 1 prior to applying a natural logarithmic transformation.

2.2.2. Family Financial Variables

Family Income, Assets, and Debt. To assess family financial status, we employed three continuous variables measured in 1000 RMB units: household income, assets, and debt. To address the skewness in the distributions, we recoded zero values to 1 prior to applying a natural logarithmic transformation.

Financial Access. The financial access variable gauges the extent to which individuals or families have access to mainstream financial services and products. It is constructed by counting the number of mainstream financial services (0–4) owned by the family, including bank accounts, loans, insurance, and trust. This count serves as a proxy for their familiarity and utilization of financial services.

Financial Knowledge. The survey incorporated four multiple-choice questions to evaluate respondents’ understanding of financial concepts such as interest, inflation, mortgage rates, and bond prices (e.g., “suppose you have a 1-year term deposit of 10,000 yuan with an annual interest rate of 3%, if there is no early withdrawal, how much money will you have upon maturity?”, “If the annual interest rate on a bank savings account is 3% and the inflation rate is 5% per year, then after one year, how much will you be able to buy with the money in this account?”, “Compared to a 30-year mortgage, is the total interest paid on a 15-year mortgage over the loan term less, the same, or more?”, and “If bank interest rates rise, what usually happens to bond prices?”). These questions measure their knowledge to accurately answer fundamental financial questions. The scale demonstrated good internal consistency in the current sample (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87). The number of correct responses (0–4) indicates a respondent’s overall financial knowledge level.

Financial Skills. Five survey questions were administered to assess respondents’ financial management abilities, encompassing financial planning, consumption, borrowing, fraud prevention, and risk mitigation. The survey questions on financial skills included “Have you established a comprehensive and clear financial plan for your family?”, “Before borrowing from others or financial institutions, you seriously consider your ability to repay.”, “When choosing to purchase financial products or services, you are able to correctly distinguish between legal and illegal investment channels.”, “You know how to use insurance to avoid financial risks and protect family financial security.”, and “You are able to pay all bills and expenses on time.” The Cronbach’s alpha value of this scale was 0.78. A higher mean score on these 5-point Likert questions indicates greater proficiency in managing finances.

Financial Attitude. To capture responding families’ views on dealing with household finance in their daily lives, we included survey questions such as “Do you think financial matters play a significant role in your family life?”, “Do you have confidence in financial products and financial institutions?”, and “Does your family rely on finances for daily living and future growth?”. Each question was evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from strong disagreement to strong agreement. The scale demonstrated a very high internal consistency score (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93). We created a mean score on these variables to measure participants’ financial attitude.

Subjective Financial Well-being. A series of 5-point Likert questions was used to assess families’ subjective perceptions of their financial status, including income stability (e.g., “How stable has your family income been over the past year?”), budgeting (e.g., “How well has your family balanced its income and expenses over the past year?”), basic needs satisfied, emergency savings, risk preparedness, and satisfaction. The Cronbach’s alpha value of this scale was 0.88. A higher mean score on these variables reflects greater self-perceived or subjective family financial well-being.

2.2.3. Control Variables

Children’s demographic and health variables. We included multiple variables related to children’s demographics and health conditions. These variables included child age (in years), disability levels [assessed on a 4-point Likert scale from “1” (mild) to “4” (severe)], self-care skills [rated on a 5-point Likert scale from “1” (very uncapable) to “5” (very capable)], injury accidents (Yes/No) and hospitalizations (Yes/No) within the past year, participation in rehabilitation programs (Yes/No), and overall health condition [rated on a 5-point Likert scale from “1” (poor) to “5” (excellent)], Family demographic variables. These variables included family size, education level of the responding parent (categorized as 1 = middle school and below, 2 = high school, 3 = college and above), urban or rural residence, marital status (classified as married and others), employment status (categorized as employed and others), and the participation status of social security programs (Yes/No). In addition, we also included a 5-point Likert measure of parents’ concerns about children’s future (assessed on a 5-point Likert variable from “1” = Completely not concerned to “5” = Very concerned).

2.3. Analyses

To address research question 1, we reported demographic characteristics of the entire sample and by families’ savings status for children with autism (Table 1). Given the study’s focus on the relationships between families’ financial preparation for children and their financial status, to address research question 2, we employed linear regression models to assess the associations of each dependent variable with each family financial variable separately, controlling for child and family characteristics (Table 2). For the first column of Table 2, we also defined savings status as a dichotomous variable and tested the same model specifications using Logit models. The results of Logit models were consistent with the linear probability models reported in Table 2; therefore, these results are not presented but are available from the authors upon request.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics by Families’ Saving Status for Children (N = 497).

Table 2.

Results of Linear Regression Models with Single Family Financial Variable (N = 497).

Finally, for research question 3, we included all eight family financial variables along with control variables in a single linear regression model (Table 3). We tested for multicollinearity among the independent variables, particularly given the theoretical relationships between financial skills, attitudes, and well-being. The largest Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) value was approximately 3.9, well below the standard threshold of 5.0, indicating that multicollinearity was not a concern in the multivariate models. Since the first dependent variable (the probability of family savings for children) is dichotomous, we also modeled it using a Logit model in supplementary analyses. In another set of supplemental analyses, we combined the two dependent variables simultaneously in a two-part model: we modeled the probability of family savings for their children in a Logit regression, and for those with savings, we modeled the amount of savings in a linear regression. The results of these supplemental analyses align with those reported in Table 3. Post-estimation diagnostics indicated no violations of the regression assumptions regarding normality or homoscedasticity.

Table 3.

Results of Regression Models with All Family Financial Variable (N = 497).

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

The sample included 228 respondents who have saved or invested for their children’s future (savers; 45.88%) and 269 who have not (non-savers; 54.12%). Families had an average savings amount of 103,610 RMB (SD = 505,970 RMB) for their children with autism. Reflecting the large proportion of non-savers and extreme distribution skewness, the median savings amount was 0 RMB, with an interquartile range (IQR) of 0 to 600,000 RMB. Household income averaged 107,860 RMB, while household assets and debt averaged 809,130 RMB and 250,180 RMB, respectively. The sample also reflected a moderate level of financial access (mean = 2.38 on a 0–4 variable range) and financial knowledge (mean = 1.80 on a 0–4 variable range). Among three variables with a range from 1 to 5, the means for financial skills (3.52), financial attitudes (3.18), and subjective financial well-being (3.03) were all greater than 3, indicating that respondents overall had relatively positive financial skills, attitudes, and subjective financial well-being.

The average age of the children with autism was 12.5 years, with a moderate mean disability level (2.08 on a scale from 1 = mild to 4 = severe) and self-care skills (3.15 on a scale from 1 = very incapable to 5 = very capable). Around 31% experienced injury accidents, and 38% had been hospitalized in the past year. The average overall health of the children was rated at 3.69 (on a scale from 1 = poor to 5 = excellent). The majority of respondents having at least a high school education. Urban residence was reported by 64% of the sample, 93% were married, and 86% were employed.

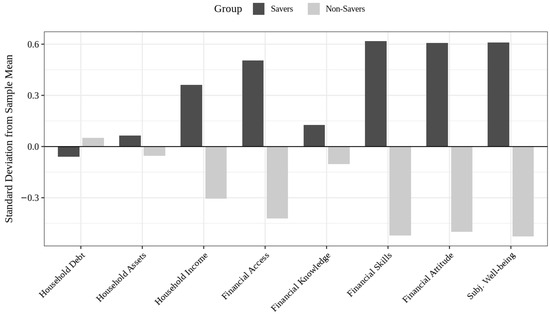

Comparing savers and non-savers reveals distinct differences in their financial and demographic profiles. Savers had an average savings amount of 225,860 RMB for their children, whereas non-savers had no savings (p < 0.001). Savers reported significantly higher household incomes (148,920 RMB) compared to non-savers (73,050 RMB; p < 0.001), indicating that families who save operate effectively double the annual income of those who do not. While savers also had higher household assets (913,900 RMB vs. 720,330 RMB) and lower household debt (172,680 RMB vs. 315,870 RMB), these differences were not statistically significant. Savers exhibited significantly better financial access (2.93 vs. 1.92, p < 0.001), financial knowledge (1.96 vs. 1.67, p < 0.01), financial skills (4.10 vs. 3.03, p < 0.001), financial attitudes (3.80 vs. 2.67, p < 0.001), and subjective financial well-being (3.61 vs. 2.53, p < 0.001), indicating a stronger financial foundation compared to non-savers. In practical terms, the difference in financial skills represents a full-point gap on the 5-point scale, suggesting that savers possess a fundamentally higher level of financial competency and confidence compared to non-savers.

In terms of children’s characteristics, savers had children with lower disability levels (1.80 vs. 2.32, p < 0.001) and higher self-care skills (3.57 vs. 2.80, p < 0.001). Children of savers also had better overall health than those of non-savers (3.96 vs. 3.46, p < 0.001). Demographically, savers were more likely to be married (96% vs. 90%, p < 0.05), employed (91% vs. 83%, p < 0.01), and participating in social security programs (94% vs. 81%, p < 0.001). These differences underscore the financial and social advantages that savers tend to have over non-savers, highlighting disparities in financial security and socioeconomic status between the two groups. However, surprisingly, savers’ children were more likely to have been injured or hospitalized in the past year.

Figure A1 in Appendix A displays the standardized differences between families who save (N = 228) and those who do not (N = 269). Savers score consistently higher across all dimensions except debt. Notably, the gap in Financial Skills and Financial Attitude (approx. +0.6 SD for savers vs. −0.5 SD for non-savers) is substantial, reinforcing the importance of non-monetary financial capabilities.

3.2. Relationships Between Savings for Children and Family Financial Variables

We first regressed each dependent variable on one of the financial variables, controlling for all children’s and families’ characteristics. The first column of Table 2 reports results on the probability of family savings for children, and the second column reports results on the amount of savings. The coefficients of the family financial variables, but not the coefficients of the control variables, are reported in the table. For example, in the model using log-transformed household income and control variables to predict the probability of family savings, the coefficient of household income was 0.15 (p < 0.001). That is, each cell in Table 2 represents one regression model.

As shown in the first column of Table 2, each family financial variable was a statistically significant predictor of the probability of family savings for children with autism, even controlling for children’s and families’ characteristics. With the exception of household debt, all other financial variables had a positive relationship with this probability. For example, controlling for the characteristics of children and families, a one percent increase in household income was associated with a 0.15% increase in the probability of family savings (p < 0.001). Similarly, a one percent increase in household assets was associated with a 0.04% increase in this probability (p < 0.001). Compared to other financial variables, three variables—financial skills, financial attitude, and subjective well-being—had relatively larger associations with the probability of family savings: a one-unit increase in any of these variables was associated with a 22% to 26% (p < 0.001) increase in the probability of family savings.

The second column of Table 2 demonstrates that all family financial variables, except household debt, had statistically significant and positive relationships with the amount of family savings for children. For example, a one percent increase in household income was associated with a 0.87% increase in the amount of family savings for children (p < 0.001). In contrast, a one percent increase in household debt was associated with a 0.15% decrease in the amount of family savings for children (p < 0.001). Additionally, a one-unit increase in financial skills, financial attitude, or subjective well-being was associated with a 118% to 134% increase in the amount of family savings for children (p < 0.001).

The models in Table 2 used only one financial variable at a time to predict the probability and amount of family savings. However, these financial variables are dynamically related, interact with each other, and are highly correlated. For example, the correlation between financial skills and both financial attitude and subjective financial well-being was 0.73. Therefore, in Table 3, we included all eight financial variables along with control variables related to children’s and families’ characteristics. With the inclusion of all financial variables, only four remained statistically significant in predicting the probability of family savings for children. A one percent increase in household debt was associated with a 0.02% decrease in this probability (p < 0.05). Additionally, a one-unit increase in financial skills, financial attitude, and subjective financial well-being was associated with a 9% to 10% increase in the probability of family savings (p < 0.05). Similarly, when predicting the amount of family savings, only four financial variables remained statistically significant. A one percent increase in household assets and debt was associated with a 0.12% increase and a 0.07% decrease, respectively, in the amount of savings (p < 0.05). Furthermore, a one-unit increase in financial attitude and subjective financial well-being was associated with a 56% to 57% increase in the amount of family savings (p < 0.001).

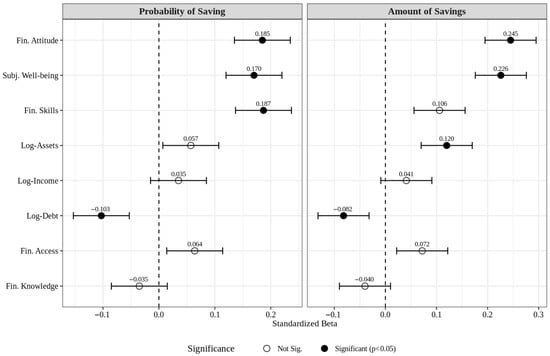

To facilitate a direct comparison of these effects, Figure 1 illustrates the standardized coefficients from the final multivariate models (Table 3) to facilitate a direct comparison of effect sizes. The forest plot highlights that subjective financial assessments—particularly financial attitude (ꞵ = 0.245) and subjective well-being (ꞵ = 0.226)—exhibit the strongest relative associations with savings outcomes, surpassing the relative magnitude of objective economic indicators such as household income and assets.

Figure 1.

Standardized Coefficients (Beta) for Predictors of Family Savings. Comparison of relative effect sizes in multivariate models.

3.3. Relationships Between Savings for Children and Characteristics of Children and Families

Table 3 also reports the results on the characteristics of children and families. Two variables were associated with the probability of family savings for children: injury accidents and respondents’ marital status. The experience of a child’s injury accident was associated with an 11% increase in the probability of family savings, while married respondents had a 17% higher probability of saving compared to those who are not married.

However, more variables of the characteristics of children and families were statistically associated with the amount of family savings. A one-year increase in a child’s age was associated with a 3% increase in the savings amount. Both the experience of injury accidents and hospitalization were associated with approximately a 45% increase in the amount of savings. Married respondents had 64% more savings than those who were not married, but, surprisingly, employed respondents had 62% less savings than those who were not employed.

4. Discussion

This study aims to address the knowledge gap on family savings for children with autism by analyzing data from 497 families to better understand whether and how families with children with autism in China prepare for their children’s financial futures. Such an understanding is essential for developing effective policies and interventions to support the economic well-being of these families and the individual development of children with autism.

4.1. Probability and Amount of Family Savings for Children

In this geographically diverse sample of Chinese families, nearly half (46%) had already begun planning for their child’s long-term financial security through savings and investments. The average savings for these children was 104,000 RMB, approximately 15,000 USD. If we limit the sample to those families with savings, the average amount increases to 226,000 RMB, approximately 32,000 USD. Given that the participating families were recruited based on their interest in family financial health services, they likely had a higher level of concern and worried about their children’s future financial security and were therefore more likely to save, invest, and make financial preparations for their children. It is reasonable to infer that the general population of Chinese families with children with autism may have a lower probability and level of financial preparation for their children’s future.

But is the total amount of financial preparation sufficient? Our previous research indicated that Chinese families with children with autism spend an average of 5000 RMB per month on their child’s autism-related expenses. For families with savings, the current savings can cover approximately 45 months of these expenses. However, it is important to note that there is significant variance in these savings; for families with savings in the sample, the median savings was 100,000 RMB, which can cover 20 months of expenses. Typically, emergency savings are considered to be equivalent to three to six months of household expenses. Measured by this standard, families who had made financial preparations appear to have prepared more adequately, possibly due to concerns about the uncertainty of their child’s future and the overall economic insecurity and risk that a child with autism brings to the family. This further highlights the unique financial planning needs of this population.

4.2. Significance of Family Financial Status

Two sets of variables were used to explore their relationships with families’ financial preparation for their children: basic demographic characteristics, and socioeconomic characteristics of families, particularly family financial variables. The results clearly show that socioeconomic characteristics of families, especially their financial status, have the most significant correlation with families’ long-term financial planning and preparation for children with autism. As shown in Table 2, each of the eight family financial variables was statistically significant in relation to the likelihood and adequacy of families’ savings for children, even when controlling for basic demographic characteristics.

It helps to further clarify the relationship between specific financial variables and families’ financial preparation by including all eight financial variables in the regression model (see Table 3). First, in terms of the likelihood of families’ savings for their children, financial stress (as measured by debt), subjective financial assessment (including assessment of financial well-being and financial attitude), and skills related to financial practices had more significant associations, compared to other financial variables. If families had a significant amount of current debt, they may not have the capacity to consider and plan for their children’s future. Also, compared to external financial opportunities (measured by financial access) and general financial literacy (measured by financial knowledge), practical skills and subjective financial attitude seem to have a more direct correlation with families making financial decisions such as saving for children.

Second, in terms of the amount of savings families accumulated for their children, household assets and debts had a more significant impact than income. This is understandable, as family savings for children were also a manifestation of their overall wealth and should be more directly related to assets and debts. Even with the same income, assets, and debts, families with positive financial attitudes and assessments of their financial well-being were more likely to save and prepare financially for their children with autism. This may reflect the unique role of subjective financial assessments in future planning, going beyond objective assessments such as income, assets, and debts. Alternatively, it may indicate that, reversely, financial preparation for children had a positive impact on families’ subjective assessment of financial well-being. It is important to note that this is an exploratory study, and this correlation could also reflect the potential impact of families’ financial preparation on their subjective assessment of financial well-being.

4.3. Significance of Family Demographic Characteristics

Among the examined demographic characteristics, marital status, child health events, and respondents’ employment status were found to be statistically significant in relation to family savings. While it is important to acknowledge that the lack of significance for other factors may be due to the inclusion of a wide range of highly correlated demographic and socioeconomic characteristics in our regression models, the significance of these specific variables warrants closer attention. The significance of marital status suggests that a stable family structure—often characterized by greater human, economic, and social resources—may enable parents to make concrete preparations and arrangements for their children’s future. Child health events, including injuries and hospitalizations, highlight the impact of unexpected events and health risks on families’ long-term planning. Families who had experienced or were more concerned about such risks and uncertainties were more likely to prepare for the future.

The negative correlation between respondents’ employment and family financial preparation for their children’s future was unexpected. In bivariate relationships, employment status was statistically and positively correlated with both the likelihood and amount of family savings for children. This negative correlation emerged after controlling for other factors in the model. We hypothesize that this may reflect a trade-off between current income security and precautionary savings. It may simply indicate that, when families had similar demographic and socioeconomic characteristics and faced the same economic and financial risks associated with having a child with autism, employed individuals may feel a greater sense of economic security and therefore had less concern about future risks, making them less likely to financially prepare for their children’s future.

4.4. Interpreting Findings Within the Chinese Context

These findings must be interpreted within China’s specific social, cultural, and policy landscape regarding disability and family financial responsibility. Unlike countries with comprehensive social insurance systems for individuals with disabilities, China’s support infrastructure for autism remains severely underdeveloped, particularly for adults. Government disability benefits are modest, and long-term residential care facilities are scarce and often prohibitively expensive. Consequently, families face a stark reality: personal savings are often the only strategy available for ensuring a child’s future security.

Furthermore, the legacy of China’s one-child policy and traditional values of filial piety (xiao) profoundly shape parents’ perspectives. Many parents in our sample cannot rely on siblings to share caregiving responsibilities. The cultural stigma surrounding autism may further discourage families from seeking external support, reinforcing privatized saving strategies. This contrasts with Western contexts where parents might prioritize advocacy for public services or rely on special needs trusts—mechanisms largely unavailable in China. Thus, while the financial stress of autism is universal, the specific behavior of aggressive saving seen in our sample is a rational response to the unique institutional gaps in the Chinese context.

4.5. Policy and Practice Implications

Our findings point to several specific, actionable interventions to support these families:

- Integrated Financial Counseling: Rather than treating financial strain as separate from autism support, service providers should incorporate debt counseling and financial planning into existing family support programs. Given that debt was a strong negative predictor of savings, helping families manage high-interest debt could free up resources for future planning.

- Matched Savings Programs: The strong association between financial attitudes and savings suggests that incentive-based programs could be effective. China could pilot Child Development Accounts (CDAs) with matched contributions for families of children with autism, modeled on the SEED for Oklahoma Kids initiative.

Specialized Financial Education: Since financial skills were a robust predictor of savings even after controlling for income, developing specialized financial literacy curricula for disability families—covering long-term cost projection and legal planning—is a low-cost, high-impact intervention.

4.6. Limitations and Implications

The research faces four limitations. First, it is an exploratory study on families’ savings and financial preparation for children with autism. We did not propose a specific theory regarding families’ financial planning for the future economic security of children with autism. The findings can serve as a foundation for future theoretical exploration and hypothesis testing in this area. Second, while the current sample was collected from a wide range of administrative regions in China, it is not nationally representative. We cannot be certain whether these findings can be generalized to all families with children with autism across the country. Third, furthermore, we do not know if these findings can be applied to other countries and societies. They may vary across different cultural, economic, political, and social contexts. Fourth, because all measures were collected through a single self-reported survey, the results may be subject to Common Method Variance (CMV), particularly regarding the correlations between subjective constructs such as financial attitude and subjective financial well-being. Nonetheless, these research findings provide an initial foundation for future studies aimed at addressing these limitations.

Overall, this article suggests several critical family factors related to the long-term economic and financial security of children with autism: (1) A relatively stable family structure and support system. We are not suggesting that the nuclear family with a married couple is the only stable and supportive structure. Rather, our research underscores the need for society to provide more resources for other types of family structures to help them prepare for the long-term economic and financial security of children with autism. (2) The socioeconomic status of the family, particularly their financial status, including their subjective assessment of their financial well-being. Conventional measures of family socioeconomic status include income, education, and employment. However, our findings indicate that, for the long-term economic and financial preparation of children with autism, assets, debts, and subjective financial assessments serve as more salient indicators. (3) Risks and uncertainties associated with autism. The higher the risks and uncertainties (e.g., injury accidents), the more likely families are to financially prepare for children’s future.

Research findings have significant implications for practice and policy development related to the long-term financial security of children with autism. First, these findings can help us identify disadvantaged families raising children with autism who are less likely to engage in long-term financial planning, allowing us to provide targeted services to help these families. For instance, families with high debt and low assets, or those with generally low assessments of their family financial well-being, require greater attention and support from policymakers and social service providers. In other words, these findings can help us identify high-risk families that lack adequate financial preparation for children with autism.

Second, these findings can help identify effective strategies and entry points to assist families in developing long-term savings and financial plans for children. Specifically, increasing families’ ability to build assets, managing family debt, improving families’ assessment of their financial situation, and enhancing families’ understanding of the financial impact and risk of autism can all contribute to further long-term savings and financial planning.

These intervention strategies could be further integrated into existing social services and policies for children with autism. For example, the ABLE accounts in the United States are savings accounts with tax benefits to encourage families to save to pay for qualified disability expenses (Kelly and Hershey 2018); our research findings can be applied to the outreach of ABLE accounts in the US context. In addition, universal asset building social policies for children have been proposed in the United States and many other countries (Huang et al. 2020, 2021). These policies should take into consideration the special needs of families raising a child with autism. Thus, our findings can inform the design and implementation of effective social policies and social services. By institutionalizing support measures for families through policy and service interventions, we can ensure that they are available to the entire population of families with children with autism. For example, parents of children with autism often face the challenge of marital dissolution, which necessitates social policies that support families of diverse structures in ensuring adequate resources for their children’s long-term development and planning.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, ensuring economic security and financial preparation for individuals with autism is a significant societal challenge faced by all societies. Today, researchers, policymakers, and practitioners worldwide have access to a wealth of scientific evidence relevant to public policies and professional services for individuals with autism. However, remaining gaps in evidence regarding supporting long-term savings and financial planning among families raising children with autism limit the implementation of research-oriented and evidence-based policy and service practices. Addressing this challenge requires further scientific investigations in all aspects of this area, including understanding these families’ financial status, financial decisions, and the effectiveness of related policies and interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Z. (Ling Zhou), J.H., and L.Z. (Li Zou); methodology, L.Z. (Ling Zhou), and J.H.; software, J.H. and X.X.; validation, L.Z. (Ling Zhou), J.H., and Y.Z.; formal analysis, J.H., Y.Z., X.H., and X.X.; investigation, L.Z. (Ling Zhou); resources, L.Z. (Ling Zhou); data curation, L.Z. (Ling Zhou) and J.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H.; writing—review and editing, L.Z. (Ling Zhou), J.H., and Y.Z.; visualization, J.H., X.H., and X.X.; supervision, J.H.; project administration, L.Z. (Ling Zhou); funding acquisition, J.H. and L.Z. (Li Zou). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the Global Incubator Seed Grant through the McDonnell International Scholars Academy and the Office of the Provost at Washington University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave informed consent. No identifying data were collected, and formal IRB approval was not required by the affiliated institution (YiBao) for minimal-risk social research.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants in the study provided informed consent prior to participating in the survey.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the inclusion of sensitive personal and family information that may compromise privacy, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Comparison of Financial Characteristics: Savers vs. Non-Savers. Values represent standardized differences from the sample mean (Z-scores).

References

- Bozkurt, Gülay, Gül Uysal, and Dilek Sönmez Düzkaya. 2019. Examination of Care Burden and Stress Coping Styles of Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 47: 142–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Rui Ying, Elise Gallagher, Kate Haas, Amy Love, and Victoria Gibbs. 2023. Exploring the Income, Savings, and Debt Levels of Autistic Adults Living in Australia. Advances in Autism 9: 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Rui Ying, Graham Hall, and Elizabeth Pellicano. 2024. Predicting the Financial Well-Being of Autistic Adults: Part I. Autism 28: 1203–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chasson, Gregory S., Geoffrey E. Harris, and William J. Neely. 2007. Cost Comparison of Early Intensive Behavioral Intervention and Special Education for Children with Autism. Journal of Child and Family Studies 16: 401–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohrs, Andrea C., and Douglas L. Leslie. 2017. Depression in Parents of Children Diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Claims-Based Analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 47: 1416–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durkin, Maureen S., Matthew J. Maenner, Jon Baio, Deborah Christensen, Julie Daniels, Robert Fitzgerald, Pamela Imm, Laura C. Lee, Laura A. Schieve, Kim Van Naarden Braun, and et al. 2017. Autism Spectrum Disorder among US Children (2002–2010): Socioeconomic, Racial, and Ethnic Disparities. American Journal of Public Health 107: 1818–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganz, Michael L. 2007. The Lifetime Distribution of the Incremental Societal Costs of Autism. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 161: 343–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon-Lipkin, Eliza, Amanda R. Marvin, Joyce K. Law, and Paul H. Lipkin. 2018. Anxiety and Mood Disorder in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and ADHD. Pediatrics 141: 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Jin, Li Zou, and Michael Sherraden, eds. 2020. Inclusive Child Development Accounts: Toward Universality and Progressivity. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Jin, Michael Sherraden, Margaret M. Clancy, Sondra G. Beverly, Trina R. Shanks, and Youngmi Kim. 2021. Asset Building and Child Development: A Policy Model for Inclusive Child Development Accounts. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 7: 176–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Xiaoqian, Xin Chen, Jing Su, and Na Liu. 2024. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Mainland China over the Past 6 Years: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Psychiatry 24: 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, Andrew, and Lucy Hershey. 2018. A 50-State Review of ABLE Act 529A Accounts. Journal of Financial Service Professionals 72: 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Leigh, J. Paul, and Jenny Du. 2015. Brief Report: Forecasting the Economic Burden of Autism in 2015 and 2025 in the United States. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 45: 4135–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salari, Nader, Sara Rasoulpoor, Samira Rasoulpoor, Sharifah Shohaimi, Sara Jafarpour, Neda Abdoli, Bahareh Khaledi, and Masoud Mohammadi. 2022. The Global Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Italian Journal of Pediatrics 48: 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharpe, Deanna L., and David L. Baker. 2011. The Financial Side of Autism: Private and Public Costs. In A Comprehensive Book on Autism Spectrum Disorders. Vienna: InTech. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherraden, Michael. 1991. Assets and the Poor: New American Welfare Policy. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sherraden, Michael, Lissa Johnson, Margaret M. Clancy, Sondra G. Beverly, Margaret S. Sherraden, Mark Schreiner, and Chang-Keun Han. 2013. Asset Building: Toward Inclusive Policy. In Encyclopedia of Social Work. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available online: https://csd.wustl.edu/18-15/ (accessed on 1 January 2013).

- Solmi, Marco, Minji Song, Dae Kyung Yon, Si Woo Lee, Eric Fombonne, Mi Sun Kim, Soohyun Park, Mi Hyun Lee, Jae Hwan Hwang, Rachel Keller, and et al. 2022. Incidence, Prevalence, and Global Burden of Autism Spectrum Disorder from 1990 to 2019 across 204 Countries. Molecular Psychiatry 27: 4172–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, Sarah, Deborah Fein, Michael Rosanoff, Geraldine Dawson, Saiful Hossain, Leanne Brennan, Arianne Como, and Andy Shih. 2012. A Global Public Health Strategy for Autism Spectrum Disorders. Autism Research 5: 211–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeidan, Jude, Eric Fombonne, Jennifer Scorah, Alaa Ibrahim, Maureen S. Durkin, Shekhar Saxena, Ahmad Yusuf, Andy Shih, and Mayada Elsabbagh. 2022. Global Prevalence of Autism: A Systematic Review Update. Autism Research 15: 778–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Li, Jintong Wang, and Jin Huang. 2022. Brief Report: Health Expenditures for Children with Autism and Family Financial Well-Being in China. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 52: 3712–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Li, Sarah L. Porterfield, Shaobing Fang, Jin Huang, and Yingying Zhang. 2023. Unintentional Injuries among Children with Developmental Disabilities Are a Public Health Challenge in China. Child: Care, Health and Development 49: 1054–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).