Abstract

Political rhetoric on immigration has increasingly framed it as a threat to public safety—fueling aggressive immigration enforcement strategies, including the expanded use of federal agents, mass deportations, and strict border controls. In particular, the immigration-crime narrative has been built on four key themes or “pillars,” which suggest that immigration (1) increases crime, (2) fuels gang violence, (3) is responsible for drug problems, and (4) requires mass deportation and strict border control policies to combat these issues and reduce crime. Using data from a 2025 Lucid survey and a review of existing literature, this article provides a clear and focused summary describing the extent to which these four claims of the immigration-crime narrative are supported by (1) public opinion and (2) findings from scientific research. As we highlight in the following sections, all four of these “pillars” of the immigration-crime narrative are in fact myths with no consistent empirical support.

1. Introduction

Political rhetoric in the United States on immigration has increasingly framed it as a threat to public safety. In the years leading up to 2025, this narrative intensified, giving rise to a renewed moral panic framing immigration as a key driver of crime and related problems throughout the United States. In particular, the immigration-crime narrative has been built on four key themes or “pillars,” which suggest that immigration (1) increases crime, (2) fuels gang violence, (3) is responsible for drug problems, and (4) requires mass deportation and strict border control policies to combat these issues and reduce crime.

These claims have become pervasive, and there is substantial “noise” surrounding these topics, especially in U.S. conservative media and political discourse. Thus, it has been difficult for research to cut through the noise to provide clarity on these topics for the public. As we note below, social science research has resoundingly rejected the first claim and shown that immigration does not increase crime overall (Martinez and Lee 2000b; Light and Miller 2018; Ousey and Kubrin 2018; among others). However, the other three pillars have received less attention in research. In addition, it is unclear how much the U.S. public believes each of these specific claims. There are some sources (e.g., Pew Research, General Social Survey) that have examined attitudes surrounding immigration broadly, and some notable studies that have assessed immigration and crime perceptions more specifically. Past research has suggested anywhere from 20 to 42% of the public believes immigration increases crime (Kulig et al. 2021; Simon and Sikich 2007; Smith 2006), with some findings suggesting increasing fear among the public in recent years (Barba 2025). However, few public opinion analyses have focused on the four specific pillars we outline here. As such, the purpose of this short article is to provide a clear and focused summary describing how much each of these four claims on immigration and crime are supported by (1) public opinion and (2) findings from scientific research.

In the following sections, we briefly describe each of the four pillars of the immigration-crime narrative listed above. Using data from a Lucid Theorem Survey, we then describe public perceptions on each of these four claims. Notably, this survey was designed and administered to 1220 adults to specifically gauge public opinion on these four immigration-crime claims.1 As we highlight in the following sections, the survey data show substantial buy-in to these narratives. This suggests that political “smoke” on the topic has led the public to believe there is a real “fire” linking immigration to crime, drugs, and gangs, which they believe should be dealt with through mass deportation and restrictive migration policies.

In response, we then provide a summary of the empirical literature related to each of these four immigration-crime claims. Notably, the goal of this research note is not to provide a comprehensive literature review that details every study on immigration and crime. Instead, the purpose here is to provide a clear and concise overview of “what we know” about each of the leading immigration-crime claims, which can be used as a tool for researchers, policy makers, and the public to sort through the noise on these topics. As we highlight in the following sections, all four of these “pillars” of the immigration-crime narrative are in fact myths with no consistent empirical support.

1.1. Myth 1: Immigration Increases Crime

The first and broadest claim in this narrative is that immigration contributes to higher crime rates. For instance, a recent article in the New York Post alleged that migrants are “beating cops in Times Square,” “running prostitution rings,” and “robbing pedestrians” (McCaughey 2024). In terms of U.S. public opinion, our Lucid survey shows substantial public belief in general claims linking immigration and crime—similar to those seen in recent Gallup polls (see Kulig et al. 2021). Specifically, 45% of respondents said they are worried that more immigration into the United States results in more crime, and 44% believe that when immigration rates go up, so too does the crime rate. In contrast, only 5% believe immigration results in less crime—which is what academic research tends to show, as we highlight below. Table 1 below presents the questions and results from a select set of questions in our survey that illustrate these opinions and perceptions about each of the other three pillars described in later sections of this paper.

Table 1.

Public Perception on Immigration, Crime, Gangs, and Drugs.

What Does the Research Show?

There is now an extensive body of research that has examined this first claim, showing that, in contrast to political rhetoric and public fears, immigration does not increase crime in the United States. At the macro-level, studies examining immigration effects on community levels of crime usually have one of three findings. First, many studies find that immigration is associated with lower levels of crime and violence across places (Feldmeyer 2009; Ousey and Kubrin 2014; Martinez et al. 2010, 2016; among others). Second, a substantial body of work finds no significant association between immigration and community crime rates (Akins et al. 2009; Lee et al. 2001; Lee and Martinez 2002; Schnapp 2015; among others). Third, some studies indicate that findings are context-dependent—moderated by factors such as regional context or neighborhood characteristics (Feldmeyer et al. 2015; Ousey and Kubrin 2009; Martinez and Lee 2000a; Ramey 2013; Shihadeh and Barranco 2010; Velez 2009). Taken together, the common thread of these works is that there is no consistent evidence that immigration increases community levels of crime and violence in the United States. This is perhaps best summarized Ousey and Kubrin’s 2018 meta-analysis (a powerful technique to synthesize evidence across numerous studies, yielding more robust, precise, and generalizable conclusions than individual analyses alone) which summarized 51 macro-level studies on immigration and crime and found that immigration has either neutral or slight protective effects on crime and violence. In turn, they found no consistent evidence linking immigration to increased crime across these studies (Ousey and Kubrin 2018).

To be clear, there is no shortage of research examining immigration effects on community crime rates. There are now nearly 100 studies on the topic. Moreover, they have examined these relationships across a wide array of locations (Miami, Chicago, El Paso, New York, California, Texas), crime outcomes (homicide, violence, total crime rates, property crime), time frames (1990 to 2020), study units (counties, MSAs, cities, census tracts), destination types (new vs. traditional), race/ethnic groups, and other comparisons.2 Across all of these different approaches and analyses, the findings are remarkably consistent. Immigration does not increase crime, and if anything, it may help protect communities from crime and violence.3 To explain these findings, researchers have drawn upon the immigrant revitalization thesis, which suggests that immigration bolsters community growth and insulates areas from crime and other social problems (Martinez and Lee 2000b; Ousey and Kubrin 2018). In these communities, immigrants typically uphold traditional pro-social values, such as a strong emphasis on employment, familial bonds, and connections to faith and the community, which protect locales from crime (Feldmeyer et al. 2019; Martinez and Lee 2000b; Ousey and Kubrin 2009). Although political rhetoric on the topic would suggest otherwise, the research on this claim is undoubtedly clear. Immigration is not elevating crime across U.S. communities, and as Hagan and Palloni (1999) summarized more than 30 years ago, “the link drawn between immigration and crime is misleading, to the extent of constituting a mythology”.

Notably, these findings are similar or even stronger in individual-level studies examining whether immigrants commit more or less crime than the U.S.-born. Research routinely finds that foreign-born individuals are less likely to commit violent, property, and drug offenses than their native-born counterparts. For example, in their study of Chicago neighborhoods, Sampson et al. (2005) found that Mexican Americans exhibit significantly lower rates of violence than other groups. Similarly, Bui (2009) found that foreign-born youth were less likely to commit a range of delinquent behaviors compared to similarly situated U.S. born youth. Moreover, there is a long line of research with similar findings showing that immigrants are less likely, not more likely, to commit crime than those born in the United States (for example, see Chen and Zhong 2013; Morenoff and Astor 2006; Ramos and Wenger 2020; Sampson et al. 2005).

These highlighted studies represent just a portion of a large body of research from the past 25 years examining immigration-crime relationships. Notably, immigration and related fears began to increase well before this period (including the 1970s and 1980s). However, it was not until the 1990s and the turn of the 21st century that academia began to closely assess immigration-crime relationships. Given the extensive body of research addressing this first claim about immigration and crime, our aim is not to list every study on the topic. Instead, the goal is to provide a straightforward synthesis of this work as a tool for both public and scholarly audiences. As this review illustrates, we can no longer say “we do not know much” about immigration and crime. We know quite a bit, and the results are remarkably consistent, showing that immigration generally does not increase crime in U.S. communities.

1.2. Myth 2: Immigrants Increase Gang Activity and Gang Violence

The second pervasive claim in the immigration and crime narrative suggests that immigration increases gang problems. This rhetoric has often labeled immigrants (particularly Hispanic immigrants) as prone to gang violence, suggesting that “migrant gangs are the biggest danger” to U.S. communities (McCaughey 2024). Similarly, Donald Trump infamously claimed “We have people coming into the country… you wouldn’t believe how bad these people are. MS-13, these are animals coming into our country…” (Colvin 2018). In terms of public opinion, results from our Lucid survey indicate that nearly half (47%) of respondents are worried that more immigration into the United States will result in more gang problems, and 44% believe that as immigration increases, so too does gang violence. Notably, only 6% believe immigration reduces gang violence. In addition, over one-third (36%) of respondents believe immigrants are more likely to join a gang than U.S.-born citizens, and 40% believe Hispanic/Latino immigrants are more likely to join a gang (while only 13–14% believe U.S.-citizens are more likely to join a gang).

What Does the Research Show?

Compared to the general body of immigration-crime research reviewed above, there is far less work specifically examining relationships between immigration, gangs, and gang activity. There are a handful of noteworthy studies that have explored these relationships, but findings are somewhat mixed. On the one hand, a small set of studies suggest that immigration could be related to greater gang activity. For example, research by Katz and Schnebly (2011) report that immigrant-dense neighborhoods may have a higher presence of gang members. However, this does not necessarily mean immigration generates gang activity—it may simply be that immigrants settle in places with greater gang presence. A study by Alexis (2021) indicates that immigrant youth may be more vulnerable to gang recruitment because they face unique marginalization. In addition, Esbensen and Carson (2012) report that by high school, immigrant youth were slightly more likely than U.S. born youth to be gang involved.

On the other hand, a slightly larger body of research indicates that immigration either has no impact on gang violence, or may even reduce it, by contributing to lower levels of gang activity among U.S. communities. In contrast to the studies noted above, Esbensen and Carson (2012) found that immigrants were less likely to be gang-involved during middle school, the period when youth are most likely to affiliate with gangs. Even when immigrant youth did affiliate, they exhibited lower rates of offending than U.S.-born gang members and were also less likely to report involvement in gang-related fights (Morenoff and Astor 2006). Other research has shown that stress from discrimination results in more gang-involvement among U.S.-born youth, but no stressors examined contributed to greater immigrant gang-involvement (Barrett et al. 2013). At the macro-level, several studies have found lower rates of gang membership in communities with larger immigrant populations (Ashton and Bussu 2020; Garcia-Rojo et al. 2025). Research by Pyrooz (2012) found that immigration is unrelated to gang activity and homicide. More recent research also suggests that immigration may provide protective effects against gang-related homicides (Proffit 2025). Taken together, there is evidence that immigrants are not inherently more likely to be gang involved (Barrett et al. 2013; Esbensen and Carson 2012) and higher levels of immigration may either have no impact on gang violence or may contribute to broader protective effects that extend to gang activity (Martinez and Lee 2000b; Proffit 2025; Pyrooz 2012). These findings have led some to conclude that there is no distinct “immigrant effect” in predicting gang membership or offending behavior (Esbensen and Carson 2012).

1.3. Myth 3: Immigration Adds to Drug Problems in American Communities

The third claim and perhaps one of the most contentious debates surrounding the immigration and crime narrative is that immigration increases U.S. drug problems. Political leaders, including Donald Trump, have routinely associated Mexican immigrants with drug cartels and drug trafficking, stating they bring “drugs and death” (Marshall Project 2024). Notably, Trump has routinely alleged that immigration is a main source of drug trafficking, claiming that “drugs [are] pouring across our border” (Reuters 2024). Importantly, public opinion appears to mirror these claims. Our Lucid survey results indicate that 43% percent of respondents believe immigrants bring drugs with them when coming into the country, and 42% of respondents believe most drugs are coming into the country because of immigration. In addition, nearly half (46%) of respondents believe that when immigration increases, so does drug-related crime—while less than 6% believe immigration decreases drug-related crimes.

What Does the Research Show?

Immigration and drug activity may be one of the more understudied areas of the immigration-crime discourse, but there are several notable studies that have begun to explore the topic. Notably, findings across these studies again show that immigration has protective effects on community drug problems, and immigrants are less likely to use drugs compared to their U.S. born counterparts (Canino et al. 2008; Feldmeyer et al. 2022; Katz et al. 2011; Light et al. 2017).

At the individual-level, there is a growing body of research indicating that immigrants are less likely to use drugs than their native-born counterparts (see Bui 2009; Canino et al. 2008; Katz et al. 2011; Ojeda et al. 2008). For example, Katz et al. (2011) found that undocumented immigrants are less likely to use drugs (i.e., marijuana, crack cocaine, opiates, methamphetamine) compared to U.S.-born citizens, with the exception of powder cocaine. Both documented and undocumented immigrants reported half the use compared to U.S.-born citizens. In another example, Ojeda et al. (2008) found that the odds of lifetime substance use by Latino and non-Latino White immigrants were lower than U.S.-born Whites. In addition, several other studies have reported similar findings, suggesting lower levels of drug use among foreign-born populations (Canino et al. 2008; Feldmeyer et al. 2022; Katz et al. 2011; Ojeda et al. 2008).

Although there are fewer macro-level studies examining immigration effects on community patterns of drug problems, findings tend to show null or protective relationships. For instance, Light et al. (2017) found that increases in undocumented immigration were linked to reductions in drug arrests, drug overdoses deaths, and DUI arrests from 1990 to 2014 in the United States. Feldmeyer et al. (2022) assessed the influence of immigration on overdose deaths using national county-level data. Results showed that growth in immigration was not tied to rising county levels of drug overdose deaths during the 2000–2015 period, and in many cases, immigration was associated with lower levels of drug overdose deaths. Some studies have also found protective effects of immigration on drug-related homicides rates (Ousey and Kubrin 2009, 2014). For instance, Martinez et al. (2003, 2004) and Nielsen et al. (2005) found that immigration was generally associated with fewer drug-related homicides in Miami neighborhoods, but findings were mixed in San Diego.

Despite pervasive political rhetoric suggesting that immigration increases U.S. drug problems, empirical research shows no support for such claims. Although more research is needed on the topic, existing work indicates that immigration tends to be linked to lower, not higher, community levels of drug use and drug-related problems (Feldmeyer et al. 2022; Light et al. 2017), and immigrants are less likely than their native-born counterparts to engage in drug use (Canino et al. 2008; Katz et al. 2011).

1.4. Myth 4: Mass Deportations and Stronger Border Policies Will Reduce Crime

The fourth pillar of the immigration-crime narrative asserts that mass deportation and border control are the solution to the three claims outlined above. In early 2025, a series of widely publicized detentions drew substantial attention to the consequences of rhetoric making these claims. Marcelo Gomes da Silva, an 18-year-old high school student, was detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) on his way to volleyball practice. Officials cited threats to public safety, though Marcelo had no criminal record (Deliso 2025). In another case, ICE apprehended a Tufts University Ph.D. student, Ozge Ozturk, based on vague allegations of “promoting violence.” After six weeks in detention, a judge ordered her release, citing a complete lack of evidence (Garcia 2025). Cases like those of Marcelo and Ozge are not isolated incidents—they are symptomatic of a broader climate shaped by political rhetoric and media coverage suggesting that deportation and border control are solutions to the crime problem (see Gaviria et al. 2025).

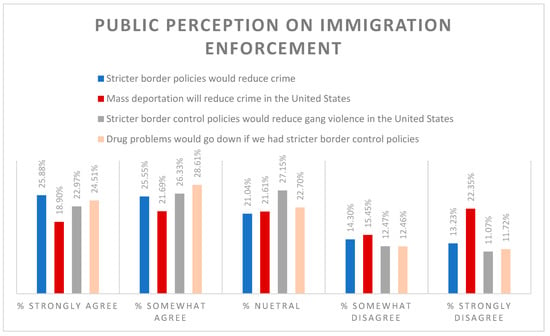

Where does public opinion lie on this topic? When asked to rank seven strategies for reducing crime, respondents in our Lucid survey sample ranked “stricter immigration (border control) policies” as the second most effective, behind stricter gun control policies.4 According to respondents, over half (51%) believe stricter border control policies will reduce crime, 50% said it would lower gang violence, 54% felt it would reduce drug problems, and 42% think mass deportations will reduce crime. Only around 20% of respondents believed that stronger immigration enforcement is unlikely to reduce these crime problems. See Figure 1 for more details.

Figure 1.

Public Perception on Immigration Enforcement.

What Does the Research Show?

What happens when immigrants are removed from communities? Assessing deportation effects can be difficult due to data limitations, but several works have assessed the links between deportation and crime, showing that deportation does not have the crime reducing effects that politicians claim. Stowell et al. (2013) assessed how deportation efforts between 1994 and 2004 influenced violent crime and aggravated assaults. Overall, the results indicated that deportation had no discernible impact on violent crime across U.S. Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs). However, when comparing MSAs in border versus non-border sectors, the results indicated that higher deportation levels were associated with significantly more violent crime and aggravated assaults in non-border MSAs—challenging the notion that deportation reduces crime. These findings align with a broader body of research on immigration enforcement and crime. For example, studies examining sanctuary cities—jurisdictions that limit cooperation with U.S. federal immigration enforcement—have found that these areas tend to experience lower crime rates or show no meaningful difference in crime compared to non-sanctuary cities (Kubrin 2014; Lyons et al. 2013; Martínez et al. 2018)

Deportation efforts may also have unintentional consequences. Immigration enforcement policies, such as 287 (g), which allow local police to check immigration status of detainees, can harm police-community relations in immigrant dense areas. In addition, deportation could disrupt the protective “immigrant revitalization” effects seen in these communities, including the economic opportunities, friendship and kinship networks, and support systems commonly found in immigrant communities (Feldmeyer et al. 2019; Ousey and Kubrin 2009; Martinez and Lee 2000b). When assessing the pre and post effects of implementing 287 (g) in Prince William County, Viriginia, findings suggested 287 (g) had no discernible impact on most forms of crime (i.e., robberies, property crimes, drug offenses, disorderly behaviors, and drunk driving), except for a reduction in aggravated assault. In a similar study, Treyger et al. (2014) found that immigration enforcement by local police does not offer measurable public safety benefits. Chalfin and Deza (2020) corroborated this, finding that as a large share of the foreign-born population left Arizona after the “E-Verify” law went into effect (requiring employers to verify the immigration status of new employees), they found no evidence that immigrant men committed more crime than native-born men. Even those who are considered “deportable aliens” are not found to be more likely to reoffend (Hickman and Suttorp 2008). Supporting this, other research on recidivism indicates that immigrants are actually less likely to reoffend than nonimmigrants—showing a 33% lower recidivism rate compared to the U.S.-born (Ramos and Wenger 2020).

Based on current empirical research, deportation appears unlikely to produce significant reductions in crime across U.S. communities. In fact, it may have unintended consequences, such as damaging police-community relations or disrupting revitalization effects that insulate immigrant communities from crime and related social problems. In terms of border security, it is undoubtedly important to have the necessary systems and protections in place to ensure border safety and appropriate passage for immigrants, but the supposed connection that stricter border policies will reduce crime, violence, and other social harms is unlikely based on existing research. By 2008, the U.S. government spent more on immigration enforcement agencies than it did on all other criminal law enforcement agencies combined (Light and Miller 2018), citing crime reduction as their primary justification. Based on the research highlighted here, this is unlikely to make a dent in U.S. crime rates, and there are likely more effective and efficient ways to combat U.S. crime.

2. Conclusions

The topic of immigration and crime has become pervasive within U.S. political rhetoric, media coverage, and public discourse, and it shows no signs of waning. This narrative has been built largely on 4 claims or “pillars,” which suggest that immigration (1) increases crime, (2) fuels gang violence, (3) is responsible for drug problems, and (4) requires mass deportation and strict border control policies to combat these issues.

The goal of this short article is to provide a clear and focused summary of the extent to which these four pillars of the immigration-crime narrative are supported by (1) public opinion and (2) findings from scientific research. As we highlight above, there has been substantial public buy-in to these claims. Large portions of the public believe that there must be some “fire” behind the political “smoke” surrounding immigration and crime. Nearly half of those in our Lucid Theorem survey believe that immigration adds to crime, gang activity, and drug problems, and many believe that deportation and border control will fix these problems. Only a small handful of respondents (less than 10%) believe that immigration makes these problems better or thought that deportation could create more problems.

Although this study provides important insight into research and public opinion on immigration and crime, future research should expand this work to examine public perceptions on related topics. For example, a potential fifth pillar could explore immigration and terrorism/extremism; as our survey did not include questions on this topic, we did not address this literature, but future work should investigate public sentiment in this area. Moreover, while the present study focuses on immigration and crime, research should also consider attitudes and emotions toward immigration more broadly, as individuals may hold distinct perceptions of immigration that are not tied to criminality.

In sum, our review of empirical research finds no support for these four claims. If anything, evidence consistently shows that immigration tends to reduce, not worsen, crime-related problems. Likewise, it does not appear to drive up gang activity or drug use, and there is no evidence that mass deportation and increased border control addresses crime problems in a meaningful way. In sum, the core “pillars” of the immigration-crime narrative have no consistent empirical foundation. They are built on sand, are more of a myth than reality, and are essentially a political ghost story: haunting but untrue.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P.; Methodology, C.P. and B.F.; Software, C.P.; Validation, C.P. and B.F.; Formal Analysis, C.P.; Investigation, C.P. and B.F.; Resources, C.P.; Data Curation, C.P.; Writing—C.P.; Writing—Review and Editing, C.P. and B.F.; Project Administration, C.P. and B.F.; Funding Acquisition, C.P. and B.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by internal funding from the Department of Criminal Justice and the College of Education, Criminal Justice, Human Services, and Information Technology at the University of Cincinnati.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of University of Cincinnati (protocol code HRP-503E; 27 February 2025). Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to non-identifiable data.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study were obtained through a restricted-access grant and are not publicly available due to confidentiality agreements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Survey Methodology

This research draws on data from a sample matched to U.S. population benchmarks of 1220 adults, collected via the Lucid Theorem platform from 30 May to 12 June 2025. Lucid operates as a leading online marketplace in the United States for obtaining survey samples, where sample providers route potential participants to Lucid, which then redirects them to clients—often marketing research organizations—that compensate respondents for their participation. Upon entering the Lucid ecosystem, adult participants share demographic details such as age, gender, race, ethnicity, education, income, and ZIP code. However, no personal identifiable information is provided to researchers. The platform typically engages with around 375,000 unique users daily (Coppock and McClellan 2019) and enables the creation of nationally representative samples through quota-based sampling and screening techniques. Prior studies have confirmed the validity of Lucid-generated data (Coppock and McClellan 2019), aligning well with broader research on opt-in samples (Berinsky et al. 2012; Mullinix et al. 2015; Peyton et al. 2022; Roche et al. 2024).

Data collection initially yielded responses for 2048 participants. After screening out respondents who did not consent or were incomplete (208 cases), respondents who failed the attention check (602 cases), and respondents with possible artificial intelligence (AI) use (18 cases), the final sample size was reduced to 1220 respondents. When benchmarked against national demographics from the 2023 American Community Survey (ACS figures in parentheses), the sample is 71.63% White (60.5%), 46.10% male (49.5%), 39.62% married (48.1%), with an average age of 50.2 (compared to the national average of 38.7 years). Additionally, 35.36% of respondents identified as Democrats, compared to 49% nationally as estimated by the Pew Research Center. As such, the sample tends to be older, includes a higher proportion of women and single individuals, and contains fewer self-identified Democrats—with 25.84% reporting independent political affiliation.

Respondents were asked questions and their opinions pertaining to immigration across five themes: (1) general attitudes, (2) crime, (3) gangs, (4) drugs, and (5) immigration enforcement. Each block ranged from four to seven questions or statements, with response options on a five-point scale (e.g., strongly agree—strongly disagree, increases a lot—decreases a lot) with neutral options available for each response. For instance, in the immigration-crime section, one question stated—When more people immigrate to the U.S., do you think the crime rate increases, decreases, or stays about the same?—with response options ranging from “increases a lot” to “decrease a lot.” Another question from the gang’s section included—Do you think immigrants are more or less likely to be in a gang?—with response options ranging from “much more likely” to “much less likely.” From this, descriptive statistics can be examined pertaining to perceptions surrounding each theme.

Notes

| 1 | Lucid Survey results (collected in May–June 2025) stem from a sample matched to U.S. population benchmarks and examine topics relating to immigration and crime, gangs, drugs, the economy, and other related social issues. Data collection initially yielded responses from 2048 individuals. After screening out respondents who did not consent or were incomplete (208 cases), respondents who failed the attention check (602 cases), and respondents with possible artificial intelligence (AI) use (18 cases), the final analytic sample included 1220 respondents. Response options were given on a 5-point scale (e.g., strongly agree to strongly disagree) with a neutral option. See Appendix A for more details. |

| 2 | In immigration research, traditional destinations are long-established gateway areas with large, historic immigrant communities, while new destinations are places that have only recently experienced rapid immigrant growth, creating distinct social, economic, and integration dynamics. |

| 3 | It is important to note that some research has indicated immigration effects are context dependent. While immigration is often linked to lower violence in traditional destination cities, newer immigrant areas may not see the same protective effects (Shihadeh and Barranco 2010, 2013)—yet overall, studies do not find consistent evidence that more immigration leads to more crime. |

| 4 | Response options included (one being most effective): (1) stricter gun control policies, (2) stricter immigration (border) policies, (3) reductions in poverty and unemployment, (4) increases in community policing, (5) youth intervention programs, (6) harsher prison sentences, and (7) increase rehabilitation for incarcerated populations. |

References

- Akins, Scott, Rubén G. Rumbaut, and Richard Stansfield. 2009. Immigration, economic disadvantage, and homicide: A community-level analysis of Austin, Texas. Homicide Studies 13: 307–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexis, Dorian. 2021. Push, Pull, Prevention: The Propensity for Undocumented Immigrant Latinx Youth to Join Gangs and How to Prevent It: A Policy Report. Ph.D. dissertation, Haverford College, Department of Political Science, Haverford, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, Sally-Ann, and Anna Bussu. 2020. Peer groups, street gangs and organized crime in the narratives of adolescent male offenders. Journal of Criminal Psychology 10: 277–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, Lloyd. 2025. Why the Second Trump Administration Is making Americans’ Perception of Migrant Crime Central to Its Communications; Public Religion Research Institute. Available online: https://prri.org/spotlight/why-the-second-trump-administration-is-making-americans-perception-of-migrant-crime-central-to-its-communications/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Barrett, Alice N., Gabriel P. Kuperminc, and Kelly M. Lewis. 2013. Acculturative stress and gang involvement among Latinos: US-born versus immigrant youth. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 35: 370–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berinsky, Adam J., Gregory A. Huber, and Gabriel S. Lenz. 2012. Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon. com’s Mechanical Turk. Political Analysis 20: 351–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, Hoan N. 2009. Parent—Child conflicts, school troubles, and differences in delinquency across immigration generations. Crime & Delinquency 55: 412–41. [Google Scholar]

- Canino, Glorisa, William A. Vega, William M. Sribney, Lynn A. Warner, and Margarita Alegría. 2008. Social relationships, social assimilation, and substance use disorders among adult Latinos in the US. Journal of Drug Issues 38: 69–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalfin, Aaron, and Monica Deza. 2020. Immigration enforcement, crime, and demography: Evidence from the Legal Arizona Workers Act. Criminology & Public Policy 19: 515–62. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Xi, and Hua Zhong. 2013. Delinquency and crime among immigrant youth—An integrative review of theoretical explanations. Laws 2: 210–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colvin, Jill. 2018. Trumps says he’ll keep using ‘animals’ to describe gang members. PBS News, May 18. [Google Scholar]

- Coppock, Alexander, and Oliver A. McClellan. 2019. Validating the demographic, political, psychological, and experimental results obtained from a new source of online survey respondents. Research & Politics 6: 2053168018822174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliso, Meredith. 2025. Massachusetts high schooler detained by ICE on way to volleyball practice speaks out following release. ABC News, June 6. [Google Scholar]

- Esbensen, Finn-Aage, and Dena C. Carson. 2012. Who are the gangsters? An examination of the age, race/ethnicity, sex, and immigration status of self-reported gang members in a seven-city study of American youth. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 28: 465–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmeyer, Ben. 2009. Immigration and violence: The offsetting effects of immigrant concentration on Latino violence. Social Science Research 38: 717–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldmeyer, Ben, Arelys Madero-Hernandez, Carlos E. Rojas-Gaona, and Lauren Copley Sabon. 2019. Immigration, collective efficacy, social ties, and violence: Unpacking the mediating mechanisms in immigration effects on neighborhood-level violence. Race and Justice 9: 123–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmeyer, Ben, Casey T. Harris, and Jennifer Scroggins. 2015. Enclaves of opportunity or “ghettos of last resort?” Assessing the effects of immigrant segregation on violent crime rates. Social Science Research 52: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmeyer, Ben, Diana Sun, Casey T. Harris, and Francis T. Cullen. 2022. More immigrants, less death: An analysis of immigration effects on county—Level drug overdose deaths, 2000–2015. Criminology 60: 667–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, Armando. 2025. Tufts University doctoral student out of ICE custody after judge orders her release. ABC News, May 9. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Rojo, Marina, Beatriz Talavera-Velasco, and Lourdes Luceno-Moreno. 2025. Risk factors associated with urban gang membership in juveniles: A systematic review. Crime & Delinquency 71: 2922–43. [Google Scholar]

- Garviria, Marcela, M. Smith, and B. Funck. 2025. Targeting El Paso. PBS. Available online: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/documentary/targeting-el-paso/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Hagan, John, and Alberto Palloni. 1999. Sociological criminology and the mythology of Hispanic immigration and crime. Social Problems 46: 617–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, Laura J., and Marika J. Suttorp. 2008. Are deportable aliens a unique threat to public safety-comparing the recidivism of deportable and nondeportable aliens. Criminology & Public Policy 7: 59. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Charles M., Andrew M. Fox, and Michael D. White. 2011. Assessing the relationship between immigration status and drug use. Justice Quarterly 28: 541–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, Charles M., and Stephen M. Schnebly. 2011. Neighborhood variation in gang member concentrations. Crime & Delinquency 57: 377–407. [Google Scholar]

- Kubrin, Charis E. 2014. Secure or insecure communities? Seven reasons to abandon the Secure Communities program. Criminology & Public Policy 13: 323. [Google Scholar]

- Kulig, Teresa C., Amanda Graham, Francis T. Cullen, Alex R. Piquero, and Murat Haner. 2021. ‘Bad hombres’ at the Southern US border? White nationalism and the perceived dangerousness of immigrants. Journal of Criminology 54: 283–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Matthew T., and Ramiro Martinez, Jr. 2002. Social disorganization revisited: Mapping the recent immigration and black homicide relationship in northern Miami. Sociological Focus 35: 363–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Matthew T., Ramiro Martinez, and Richard Rosenfeld. 2001. Does immigration increase homicide? Negative evidence from three border cities. The Sociological Quarterly 42: 559–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, Michael T., and Ty Miller. 2018. Does undocumented immigration increase violent crime? Criminology 56: 370–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Light, Michael T., Ty Miller, and Brian C. Kelly. 2017. Undocumented immigration, drug problems, and driving under the influence in the United States, 1990–2014. American Journal of Public Health 107: 1448–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, Christopher J., María B. Vélez, and Wayne A. Santoro. 2013. Neighborhood immigration, violence, and city-level immigrant political opportunities. American Sociological Review 78: 604–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall Project. 2024. Fact Checking over 12,000 of Donald Trump’s Quotes About Immigrants. The Marshall Project. Available online: https://www.themarshallproject.org/2024/10/21/fact-check-12000-trump-statements-immigrants (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Martinez, Ramiro, Jr., Amie L. Nielsen, and Matthew T. Lee. 2003. Reconsidering the Marielito legacy: Race/ethnicity, nativity, and homicide motives. Social Science Quarterly 84: 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, Ramiro, Jr., and Matthew T. Lee. 2000a. Comparing the context of immigrant homicides in Miami: Haitians, Jamaicans and Marels. International Migration Review 34: 794–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, Ramiro, Jr., and Matthew T. Lee. 2000b. On immigration and crime. Criminal Justice 1: 486–524. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, Ramiro, Jr., Jacob I. Stowell, and Janice A. Iwama. 2016. The role of immigration: Race/ethnicity and San Diego homicides since 1970. Journal of Quantitative Criminology 32: 471–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, Ramiro, Jr., Jacob I. Stowell, and Matthew T. Lee. 2010. Immigration and crime in an era of transformation: A longitudinal analysis of homicides in San Diego neighborhoods, 1980–2000. Criminology 48: 797–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, Ramiro, Jr., Matthew T. Lee, and Amie L. Nielsen. 2004. Segmented Assimilation, Local Context and Determinants of Drug Violence in Miami and San Diego: Does Ethnicity and Immigration Matter? International Migration Review 38: 131–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, Daniel E., Ricardo D. Martínez-Schuldt, and Guillermo Cantor. 2018. Providing Sanctuary or Fostering Crime? A Review of the Research on “Sanctuary Cities” and Crime. Sociology Compass 12: e12547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaughey, B. 2024. The migrant surge brings killers and criminal gangs, victimizing innocents like Laken Riley. New York Post, February 27. [Google Scholar]

- Morenoff, Jeffrey D., and Avraham Astor. 2006. Immigrant assimilation and crime. In Immigration and Crime: Race, Ethnicity, and Violence. New York: NYU Press, pp. 36–63. [Google Scholar]

- Mullinix, Kevin J., Thomas J. Leeper, James N. Druckman, and Jeremy Freese. 2015. The generalizability of survey experiments. Journal of Experimental Political Science 2: 109–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, Amie L., Matthew T. Lee, and Ramiro Martinez, Jr. 2005. Integrating race, place and motive in social disorganization theory: Lessons from a comparison of black and Latino homicide types in two immigrant destination cities. Criminology 43: 837–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, Victoria D., Thomas L. Patterson, and Steffanie A. Strathdee. 2008. The influence of perceived risk to health and immigration-related characteristics on substance use among Latino and other immigrants. American Journal of Public Health 98: 862–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ousey, Graham C., and Charis E. Kubrin. 2009. Exploring the connection between immigration and violent crime rates in US cities, 1980–2000. Social Problems 56: 447–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ousey, Graham C., and Charis E. Kubrin. 2014. Immigration and the changing nature of homicide in US cities, 1980–2010. Journal of Quantitative Criminology 30: 453–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ousey, Graham C., and Charis E. Kubrin. 2018. Immigration and crime: Assessing a contentious issue. Annual Review of Criminology 1: 6384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyton, Kyle, Gregory A. Huber, and Alexander Coppock. 2022. The generalizability of online experiments conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Experimental Political Science 9: 379–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proffit, Calvin. 2025. Gang Homicide and the Unequal Distribution of Disadvantage: Revisiting Krivo and Peterson’s Threshold Effects 25 Years Later. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyrooz, David C. 2012. Structural covariates of gang homicide in large US cities. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 49: 489–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramey, David M. 2013. Immigrant revitalization and neighborhood violent crime in established and new destination cities. Social Forces 92: 597–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, Javier, and Marin R. Wenger. 2020. Immigration and recidivism: What is the link? Justice Quarterly 37: 436–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuters. 2024. Trump says he will put tariff on Mexico to stop flow of fentanyl into U.S. Reuters. November 5. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/us/trump-says-he-will-put-tariff-mexico-stop-flow-fentanyl-into-us-2024-11-05/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Roche, Sean Patric, Heejin Lee, Justin T. Pickett, Amanda Graham, and Francis T. Cullen. 2024. Validation of short-form scales of self-control, procedural justice, and moral foundations. Justice Quarterly 41: 1002–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, Robert J., Jeffrey D. Morenoff, and Stephen Raudenbush. 2005. Social anatomy of racial and ethnic disparities in violence. American Journal of Public Health 95: 224–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnapp, Patrick. 2015. Identifying the effect of immigration on homicide rates in US cities: An instrumental variables approach. Homicide Studies 19: 103–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shihadeh, Edward S., and Raymond E. Barranco. 2010. Latino immigration, economic deprivation, and violence: Regional differences in the effect of linguistic isolation. Homicide Studies 14: 336–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shihadeh, Edward S., and Raymond E. Barranco. 2013. The imperative of place: Homicide and the new Latino migration. The Sociological Quarterly 54: 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, Rita J., and Keri W. Sikich. 2007. Public attitudes toward immigrants and immigration policies across seven nations. International Migration Review 41: 956–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Gregory A. 2006. Attitudes toward immigration: In the pulpit and the pew. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2006/04/25/attitudes-toward-immigration-in-the-pulpit-and-the-pew/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Stowell, Jacob I., Steven F. Messner, Michael S. Barton, and Lawrence E. Raffalovich. 2013. Addition by subtraction? A longitudinal analysis of the impact of deportation efforts on violent crime. Law & Society Review 47: 909–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treyger, Elina, Aaron Chalfin, and Charles Loeffler. 2014. Immigration enforcement, policing, and crime: Evidence from the secure communities program. Criminology & Public Policy 13: 285–322. [Google Scholar]

- Velez, Maria B. 2009. Contextualizing the immigration and crime effect: An analysis of homicide in Chicago neighborhoods. Homicide Studies 13: 325–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).