Abstract

This study challenges the traditional perception of cultural values as uniform at the national level, particularly in light of globalization and demographic changes that reveal substantial intra-nation diversity. Utilizing a person-centered approach through Latent Profile Analysis (LPA), the research synthesizes Schwartz’s value orientations and Hofstede’s cultural dimensions to analyze data from 595 respondents in the United States, exemplifying a multicultural diverse society. The findings indicate that cultural value profiles primarily cluster around hierarchy and power distance, reflecting sociocultural attitudes toward authority and relational dynamics relevant to current social and political contexts. Notably, individual-level analysis reveals significant variations in how cultural values are internalized and enacted, suggesting that these values influence personal behavior rather than merely serving as collective descriptors. The study emphasizes the coexistence of conflicting cultural and value orientations within an individual and highlights the need to consider individual differences in cultural analysis. While the research contributes valuable insights into cultural psychology, the research is limited by its cross-sectional design and focus on a single nation, suggesting the need for future studies to adopt longitudinal and cross-national approaches. This research advances a more nuanced understanding of cultural values, with implications for management, policymaking, and education in multicultural societies.

1. Introduction

Culture significantly influences individual cognition, emotion, and behavior, particularly in a diverse and ideologically polarized society like the United States. Understanding the structure of value systems is important, especially given the limitations of traditional cultural frameworks such as Schwartz’s value theory (Schwartz 1992) and Hofstede’s cultural dimensions (Hofstede 2001), which often focus on national or group averages and overlook individual variability.

Social science faces challenges in measuring culture and values effectively, as traditional frameworks have been extensively used across various disciplines to clarify concepts like institutional trust and social cohesion (Hofstede et al. 2010; Schwartz 1992, 2012). However, these frameworks often assume cultural homogeneity at the national level, which can obscure significant intra-societal variations and lead to ecological fallacies (Boer and Fischer 2013; Taras et al. 2010). This reliance on national averages confounds theory testing and diminishes validity, masking critical individual-level differences. To overcome these challenges, person-centered methodologies like LPA have emerged, allowing researchers to identify subgroups with distinct value configurations (Morin et al. 2016; Spurk et al. 2020).

The current study seeks to integrate Schwartz’s and Hofstede’s cultural frameworks within the U.S. context, aiming to enhance quantitative theory testing by addressing the heterogeneity often overlooked by traditional cultural research methods (Schwartz 1992, 2006, 2012; Hofstede 1980). While both frameworks have significantly influenced cultural studies, their differing theoretical foundations and analytical levels have resulted in parallel research traditions that limit opportunities for integration. Most cultural studies focus on mean-level differences between nations, which can obscure the individual diversity in cultural orientations (Fischer and Schwartz 2011). Cultural values play a crucial role in shaping individual behavior and social interactions (Schwartz 1992, 2012). Although Schwartz and Hofstede have laid the groundwork for understanding systematic variations in motivational orientations, much of the existing research has relied on national averages, treating populations as homogeneous and neglecting individual-level variability, particularly in diverse societies like the U.S. (Fischer and Schwartz 2011). The current study adopts a person-centered approach to investigate cultural values among U.S. individuals, revealing a range of value profiles within a single national context.

Furthermore, the evolution of the concept of “national character” into structured frameworks of cultural values has been essential for understanding cultural priorities. However, empirical research often emphasizes national averages, leading to ecological fallacies that misattribute group characteristics to individuals (Fischer and Derham 2016; Taras et al. 2010). Yeganeh (2024) presents a conceptual framework that elucidates the complexities of cultural change, highlighting the impacts of modernization, demographic transitions, and globalization on value systems. His analysis contests the notion of national cultural homogeneity, instead illustrating the fluidity of cultural orientations in a globalized context. This perspective aligns with the current study’s aim to explore value diversity using person-centered methods (Yeganeh 2024). Furthermore, this approach may obscure significant intra-national variability, especially in multicultural contexts where demographic factors contribute to diverse value orientations (De Mooij and Beniflah 2017). While national means can be useful for mapping broad cultural differences, they often fail to capture the nuanced and varied value systems present within a nation (Fischer and Derham 2016; Oyserman et al. 2002; Schwartz and Bardi 2001; Taras et al. 2012). Research indicates that cultural values often vary more within nations than between them, with up to 90% of value orientation variance occurring at the individual level (Steel et al. 2018; Fischer et al. 2010; van Hoorn 2015). For instance, ethnic groups in the U.S. may share converging value systems while also displaying significant individual differences. This intra-national variability challenges the reliance on national aggregates and emphasizes the need for a more nuanced analysis of culture as it manifests in individual experiences (De Mooij and Beniflah 2017; Taras et al. 2016; Fischer and Poortinga 2012; Matsumoto and Yoo 2006).

Scholarship increasingly advocates for a person-centered approach to cultural values, recognizing that individuals internalize multiple, sometimes conflicting, cultural narratives (Cooper et al. 2020; Na et al. 2010; Vignoles et al. 2016). While Hofstede’s dimensions of Individualism-Collectivism and Power Distance align with Schwartz’s concepts of Autonomy vs. Embeddedness and Hierarchy vs. Egalitarianism, Hofstede’s Uncertainty Avoidance and Long-Term Orientation lack direct equivalents in Schwartz’s framework (Kaasa 2021; Minkov and Kaasa 2024). This suggests that although both frameworks enhance the understanding of cultural differences, their infrequent combined application at the individual level limits insights into how individuals assimilate various cultural narratives (Benet-Martínez and Haritatos 2005; Spencer-Rodgers et al. 2007; Na et al. 2010; Vignoles et al. 2016). Consequently, cultural values are essential for understanding how individuals and groups navigate the social landscape, influencing decision-making, interpersonal relationships, and social frameworks (Schwartz 1992).

While Schwartz’s and Hofstede’s frameworks have significantly contributed to defining cross-cultural differences, their predominant use at the national level often obscures the variability within nations, particularly in multicultural societies like the United States. There is a growing demand for methodologies that explore cultural values at the individual level, revealing the diversity that country-level analyses may overlook. This study aims to analyze the foundations of Schwartz’s and Hofstede’s frameworks, highlighting their contributions and limitations while contextualizing the current study within the literature on individual-level approaches to cultural values. In order to accomplish this, the study employs LPA to identify subgroups defined by unique combinations of cultural and personality traits, synthesizing Schwartz’s value orientations and Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. This approach allows for a deeper understanding of individual cultural profiles in the U.S., moving beyond national averages to examine the interaction of values and personality at the individual level (Taras et al. 2010; Yoo et al. 2011). It addresses the limitations of national aggregates in cross-cultural research and the person-situation debate in personality psychology, revealing systematic variability often overlooked by variable-centered approaches (Fleeson 2004; Fleeson and Noftle 2008; Stewart and Barrick 2004).

This research advances the understanding of cultural value by shifting from a variable-centered to a person-centered approach, which uncovers latent subgroups of individuals sharing similar value configurations within a specific national context. This methodological transition is particularly relevant in light of global migration, transnational labor movements, demographic diversification, and the rapid spread of cultural content across borders, which have fundamentally altered the internal cultural dynamics of many nations (Hofstede et al. 2010; Schwartz 2006). Traditional models that assume cultural uniformity at the national level are increasingly insufficient because they ignore the complexities introduced by these global phenomena that challenge the idea of cultural homogeneity. By employing a person-centered methodology, this study acknowledges that cultural values are not uniformly accepted; rather, they exist in overlapping and sometimes conflicting clusters within national boundaries. This theoretical contribution challenges rigid notions of cultural identity and offers practical tools for understanding value pluralism and its implications for social cohesion, policy development, and intercultural dialog. The research highlights significant heterogeneity in cultural and personality configurations within a U.S. sample, elucidating variability and demonstrating how cultural values function as psychological dispositions that influence personal priorities and behaviors.

This nuanced perspective recognizes the pluralistic value landscape of the United States while aligning with the emphasis on individual differences in personality science. By focusing on individual-level variability within a multicultural population, the study diverges from most research that aggregates responses to the national level. This focus is critical because cultural values, akin to personality traits, serve as psychological orientations that guide behavior and social interaction, yet they may not be evenly distributed across a nation. Through the analysis of cultural value profiles at the individual level, the research moves beyond stereotypes of national character and highlights the heterogeneity that more accurately reflects the lived experiences of individuals in diverse societies like the United States. This approach contributes to personality science by emphasizing individual differences in cultural orientations, and it provides a methodological bridge between cultural psychology and the study of personality processes.

The study poses research questions rather than formal hypotheses, reflecting the intricate nature of cultural dynamics. These questions include: What individual cultural profiles emerge from Schwartz’s seven value orientations? What cultural profiles arise from Hofstede’s individual-level six value dimensions? And what patterns can be observed when cross-tabulating Schwartz and Hofstede’s profiles? By addressing these questions, the study seeks to provide a more detailed and comprehensive understanding of cultural values as they manifest in individual behaviors and preferences.

The subsequent sections are organized as follows: first, a review of the relevant literature will outline the theoretical foundations underpinning the study. This is followed by a detailed account of the participant sample and research methods. The empirical findings are then presented and analyzed. Finally, the discussion addresses the theoretical and practical implications of the study, considers directions for future research, and concludes with key insights.

2. Literature Review

The study of cultural values synthesizes Schwartz’s theory of value orientations with Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. Schwartz (1992) introduced a universal value structure based on motivational goals, identifying seven value orientations, offering a more psychologically nuanced understanding of values. Conversely, Hofstede’s (2001) framework was derived from IBM employee data, and despite its impact, Hofstede’s framework has been criticized for oversimplifying national cultures and neglecting within-country variations (McSweeney 2002).

Both Schwartz’s and Hofstede’s frameworks have been predominantly used in variable-centered analyses, which limits insights into how individual value orientations interact. Recent methodological advancements, particularly LPA, present a person-centered approach that can uncover subgroups with shared value configurations (Spurk et al. 2020). This is particularly relevant in culturally diverse societies like the United States, where social fragmentation and pluralism suggest multiple coexisting value systems. This section emphasizes the importance of Schwartz’s and Hofstede’s frameworks in cross-disciplinary research, their methodological shortcomings, and the potential of emerging person-centered alternatives. It underscores the challenges of utilizing national-level data and highlights the rationale for this study’s analytical strategy, highlighting the need for a more effective approach to integrating frameworks and operationalizing culture at the individual level.

2.1. Conceptualizing Culture and Values

Cultural values are persistent beliefs regarding preferred goals and behaviors, directing individuals and societies in the prioritization of actions (Schwartz 1992, 2006). In contrast to norms that govern situational conduct, values serve as motivational orientations that function across various contexts, thereby connecting them to the examination of personality and individual differences (Roccas et al. 2002). Two prominent frameworks in cross-cultural research are Schwartz’s theory of value orientations (Schwartz 1992, 2006, 2012) and Hofstede’s cultural dimensions (1980). Hofstede’s framework, derived from extensive surveys of IBM employees, identifies key dimensions such as individualism vs. collectivism, power distance, uncertainty avoidance, and masculinity vs. femininity, which provides a structured approach to understanding cultural characteristics at a national level, and later added two additional dimensions: Long-Term vs. Short-Term Orientation, and Indulgence vs. Restraint (Hofstede et al. 2010). Schwartz expanded on this by identifying seven value orientations: Mastery, Affective Autonomy, Intellectual Autonomy, Egalitarianism, Hierarchy, Harmony, and Embeddedness. These orientations represent the concept that cultures resolve universal societal problems through seven competing priorities for societies, such as self-enhancement versus group welfare, and are arranged in a coherent circular structure where compatible values are adjacent and conflicting values are distant.

2.2. Schwartz’s Value Orientations

Schwartz (2004) defines culture as a complex amalgamation of meanings, rituals, symbols, norms, and values that shape social interactions, emphasizing its ties to social institutions, history, demography, and environment. The measurement of culture can be complex, leading to various interpretations of cultural differences. Sagiv and Schwartz (2022) describe values as broad goals that reflect fundamental motivations and create a stable hierarchy influencing behavior and decision-making. Cultural value theory posits that values shape a culture’s concepts and actions, addressing societal challenges through interpersonal interactions and ethical behavior (Witte et al. 2020). This theory identifies three interrelated dimensions: autonomy vs. embeddedness, egalitarianism vs. hierarchy, and mastery vs. harmony. These dimensions arise from individual differences in value significance and impact beliefs and behavior structures (Schwartz 2006, 2012). The autonomy vs. embeddedness dimension contrasts individual independence with group integration, where high autonomy cultures promote personal distinctiveness, while embeddedness cultures emphasize solidarity. The hierarchy vs. egalitarianism dimension addresses social structure preservation, with egalitarian cultures fostering equality, in contrast to hierarchical cultures that accept unequal power distribution. The harmony vs. mastery dimension highlights the relationship between individuals and their environment, where harmony values adaptation and environmental protection, while mastery focuses on control and advancement (Schwartz 2006).

2.3. Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions

Hofstede (1980) proposed that cultures systematically differ across dimensions including individualism–collectivism, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance. These insights significantly influenced research in cross-cultural psychology and management (Hofstede et al. 2010). Nonetheless, the methodology has faced criticism for depending on data from a singular corporation and for simplifying cultural diversity to national averages (McSweeney 2002). The six cultural dimensions identified by Hofstede include Uncertainty Avoidance, which gauges the discomfort individuals feel in unstructured situations; Masculinity vs. Femininity, which contrasts achievement and material success with quality of life and nurturing; Power Distance, which measures the acceptance of hierarchy and unequal power distribution; Individualism vs. Collectivism, which assesses the prioritization of personal identity versus group belonging; Long-term vs. Short-term Orientation, reflecting decision-making time horizons; and Indulgence vs. Restraint, which evaluates the emphasis on leisure and pleasure (Hofstede et al. 2010; Hofstede 2011; Minkov 2007). Hofstede’s framework has been widely utilized in cultural studies, influencing numerous researchers globally (e.g., Beugelsdijk and Welzel 2018; Bond et al. 2004; House and Javidan 2004).

While Schwartz emphasizes individual-level motivations (Fog 2021; Kaasa 2021). Hofstede’s extensive research, involving over 100,000 questionnaires from IBM employees across 50 countries, established a significant framework for analyzing cultural characteristics at a national level, culminating in six cultural dimensions that provide a structured approach to measuring and comparing cultural traits (Hofstede 2011; Hofstede et al. 2010; Dan 2018). Hofstede defined culture as the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes one group or category of people from another, highlighting its collective nature while also recognizing individual variations within cultures (Hofstede 2001; Hofstede 2011).

2.4. The Intersection of Personality, Culture and Values

Comparative studies show both overlaps and distinctions between Schwartz’s and Hofstede’s frameworks, with Fischer and Poortinga (2012) highlighting similarities and Magnusson et al. (2008) arguing for minimal overlaps. According to Gouveia and Ros (2000), Hofstede’s framework is better suited to macroeconomic contexts, whereas Schwartz’s is more appropriate for macrosocial settings. Kaasa and Welzel (2023) emphasize the importance of incorporating Schwartz’s dimensions into larger cultural frameworks, cautioning against making cultural comparisons solely based on keyword associations. Taras et al. (2009) emphasize the importance of distinguishing between values based on culture and those influenced by individual personality. Research highlights the significance of cultural contexts in understanding individual differences (Heine and Buchtel 2009; McCrae and Terracciano 2005; Church 2016). Person-centered methods, such as LPA, effectively identify subgroups with similar value configurations, calling into question cultural homogeneity.

Additionally, scholarship criticizes traditional cultural frameworks such as Hofstede’s (1980) and Schwartz’s (1992), arguing for a more dynamic understanding of personality and self-concept. Church et al. (2013) challenge the frameworks’ static nature, emphasizing intraindividual variability in personality traits based on situational cues, which contradicts Hofstede’s concept of cross-situational stability. This is consistent with Schwartz’s emphasis on motivational values, implying that values like autonomy and benevolence can contextually influence personality states. Church et al. (2013) propose person-centered methodologies to capture this variability, which goes beyond national averages. As Du et al. (2019) operationalize Schwartz’s values on an individual level, they show that cultural fit does not always result in positive outcomes, complicating Hofstede’s static cultural dimensions. Furthermore, Rozin (2003) criticizes the emphasis on broad cultural differences, advocating for analyses that account for individual variation. Empirical evidence indicates interactions between traits, culture, and situational context, with situational variability being more pronounced in collectivistic contexts (Church et al. 2008). Hong and Mallorie (2004) propose a culture X situation interaction model, which views culture as a dynamic system that requires real-time monitoring of behavioral changes. Building on this dynamic perspective, Anglim et al. (2017) synthesize Hofstede and Schwartz’s frameworks in a person-centered approach, distinguishing between environmental values and genetically anchored personality traits. This supports the need for cultural frameworks that account for biopsychosocial variability. This review emphasizes the significance of incorporating cultural values into personality research, which improves our understanding of individual differences and places personality within sociocultural frameworks.

2.5. From National Averages to Individual-Level Approaches

Cultural value frameworks, such as Schwartz’s orientations (Schwartz 1992, 2012) and Hofstede’s dimensions (Hofstede et al. 2010), are essential for testing theories across social science disciplines, influencing concepts like institutional trust, organizational behavior, and social cohesion. However, these frameworks have faced criticism for their reliance on national averages, which can lead to assumptions of homogeneity within societies, obscuring individual differences and resulting in ecological fallacies (Taras et al. 2016; Fischer 2006; Boer and Fischer 2013). This generalization risks undermining the validity of theoretical claims in sociology, economics, and psychology, as neglecting intra-national variability may weaken theoretical robustness. To address these limitations, there is a growing demand for methodologies that account for sample heterogeneity. Recent advancements in person-centered methods, particularly LPA, provide promising solutions. This shift in scholarship emphasizes the significant intra-national variations in value orientations, allowing researchers to identify meaningful subgroups within nations and offering a more nuanced understanding of cultural diversity. These methodologies align with personality studies by treating values as individual-level orientations, thereby bridging cultural and personality psychology (Morin et al. 2016; Spurk et al. 2020; Fischer and Schwartz 2011).

Traditionally, empirical research has relied on national averages to define cultures, with Hofstede’s indices and Schwartz’s surveys being prominent in management, psychology, and sociology (Schwartz 2006). However, this approach often consolidates individual responses to national scores, reinforcing the perception of countries as cohesive cultural entities. While useful for identifying general disparities, this reliance on aggregates risks ecological fallacies, as national averages may not accurately reflect individual experiences within those nations (Fischer 2009). For example, while the United States is often characterized as a highly individualistic society according to Hofstede’s framework, this characterization may obscure significant diversity among its subgroups. The assumption of cultural homogeneity is particularly contentious in diverse nations like the United States, where studies indicate that ethnic and immigrant groups often differ in their value endorsements, influenced by cultural heritage and adaptation to the host society. For instance, Asian American groups may endorse more collectivist values compared to European Americans, while Latino populations might prioritize relational harmony and benevolence more than national averages suggest. Schwartz’s comparative analysis further indicates that intra-society variance can equal or exceed inter-society variance, highlighting the importance of examining value priorities at subnational levels (Oyserman et al. 2002; Schwartz 2006; Fischer and Schwartz 2011; Varnum 2008). These findings suggest that viewing the United States as culturally homogeneous undermines the recognition of significant intra-national disparities with psychological and social implications.

Cultural values research aims to uncover shared principles that influence human thought and behavior across different societies, highlighting the significance of values in understanding cultural and psychological diversity. Two prominent frameworks in this field are Schwartz’s theory of value orientations and Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, both of which have greatly impacted cross-cultural research (Hofstede 1980; Schwartz 1992, 2006, 2012). These frameworks demonstrate that values function as collective constructs while also reflecting individual orientations, similar to personality traits that indicate consistent patterns in thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (Roccas et al. 2002). This intersection of cultural values with culture and personality studies reveals a complex relationship. However, a critical limitation in cross-cultural research is the tendency to rely on national averages, which can obscure the diversity of values present in multicultural societies, such as the United States.

2.6. Towards Individual-Level Strategies: LPA—Person-Centric Approach

Prior research has established the effectiveness of latent profile models in identifying hidden subgroups across various domains, including gender role attitudes (Barth and Trübner 2018), environmental concern (Rhead et al. 2018), and distributive justice preferences (Van Hootegem 2022). These studies reveal a critical methodological insight: relying on averages can obscure meaningful latent diversity. Hofstede’s dimensions and Schwartz’s value orientations provide frameworks for understanding cultural and motivational orientations, yet their application at the national level has faced critiques regarding ecological validity (Hofstede et al. 2010; Schwartz 2012; Boer and Fischer 2013).

The literature on cultural values has traditionally viewed nations as uniform entities, often relying on frameworks such as Hofstede’s dimensions. However, recent studies emphasize the importance of individual-level values, revealing significant diversity within societies. For example, Leite et al. (2021) employed Schwartz’s values to cluster individuals in Europe, highlighting notable heterogeneity in value priorities within national borders. Similarly, Dupuy et al. (2021) demonstrated how cultural norms shape parental feeding practices, underscoring the significance of micro-level cultural processes in daily behaviors. These insights align with Dingil et al. (2019), who linked Hofstede’s dimensions to urban travel patterns, suggesting that cultural orientations influence not only abstract attitudes but also everyday decisions. Together, these studies challenge the idea of cultural homogeneity and advocate for person-centered methodologies, such as LPA, to identify distinct subgroups with shared value orientations. By shifting the focus from aggregate national scores to individual-level analysis, researchers can gain a more nuanced understanding of cultural values in diverse societies (Leite et al. 2021; Dupuy et al. 2021; Dingil et al. 2019). A person-centered approach, particularly through LPA, offers a promising alternative by allowing for integration and application at the individual level. Its application across fields such as developmental psychology, education, and public health underscores its utility in exploring individual pathways beyond aggregate trends. Furthermore, advancements like longitudinal and multilevel LPA are enhancing its applicability while maintaining its core strengths (Jeon et al. 2022).

Analyzing cultural values at the individual level is key, as these values significantly influence behavior and identity, aligning closely with personality science (Roccas et al. 2002). In multicultural contexts, this individual-level analysis provides a nuanced understanding of cultural diversity, challenging the perception of countries as homogeneous entities (Taras et al. 2012). In the U.S., where diverse value orientations arise from migration and regional differences, focusing on individual-level data is essential for comprehending culture as both communal and contentious (Fischer 2009; Schwartz 2006, 2012). A person-centered approach addresses the limitations of traditional methods by identifying typologies that link personality with motivational and cultural orientations (Howard and Hoffman 2018; Laursen and Hoff 2006; Donnellan and Robins 2010; Li and Wilt 2025). This perspective aligns with the understanding that personality is stable yet contextually influenced (Fleeson 2004; Stewart and Barrick 2004).

Synthesizing Schwartz’s and Hofstede’s frameworks through a person-centered lens allows researchers to better understand how cultural values affect personality expression and the variability within national cultural frameworks (Matsumoto and Yoo 2006; Fischer and Poortinga 2012). However, studies comparing Schwartz’s and Hofstede’s frameworks have produced mixed results regarding their applicability at the individual level, emphasizing the need for reliable assessments that capture the unique thoughts and behaviors that national culture may overlook (Blodgett et al. 2008; Messner 2016; Yoo et al. 2011). This underscores the necessity of individualizing cultural analysis to enrich the understanding of the interplay between culture and individual behavior. To illustrate the feasibility and superiority of this approach, the following section outlines our method and analytic strategy.

3. Materials and Methods

The methodological approach of this study is grounded in theoretical foundations and addresses empirical gaps identified earlier. The research design encompasses sample selection, data collection methods, and analytical techniques aimed at synthesizing Schwartz’s and Hofstede’s frameworks. Data was gathered from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk), resulting in a final sample of 595 respondents. Participants were required to be over 21 years old, have at least one year of professional work experience, and work a minimum of 20 h per week. The sample consisted of 306 men (51.4%) and 289 women (48.6%), with three participants (0.5%) opting not to disclose their gender. The age distribution of participants ranged from 18 to 71 years, with a mean age of 36.8 years (SD = 10.9). The age groups were as follows: 25–34 years (34.6%, n = 206), 35–44 years (36.1%, n = 215), 45–54 years (18.3%, n = 109), 55–64 years (8.4%, n = 50), and over 64 years (2.5%, n = 15). A significant majority, 551 participants (92.6%) reported residing in the U.S., while 44 (7.4%) indicated non-U.S. residency.

To ensure data quality, several response-control procedures were implemented. Responses with missing data, completion times below one-third of the median, or straight-lined responses were excluded. Additionally, three attention-check items were included, and participants failing any of them were removed from the dataset. The initial collected response sample included over 1500 respondents, but after applying these screening measures, only N = 595 valid responses were utilized for analysis, consistent with best practices in online survey research (Meade and Craig 2012; Hauser et al. 2019; Peer et al. 2022). Analysis was conducted using the original response values for the analyses, since standardizing the data would not change the number of profiles identified or the accuracy of classification (entropy) (Masyn 2013; Nylund et al. 2007). A sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the impact of indicator scaling on model selection and classification quality. For the Schwartz values instrument, the optimal solution was K = 7 for both unstandardized and standardized indicators, with minor entropy differences (Δ ≤ 0.02). Similarly, for the Hofstede cultural dimensions, K = 6 was preferred, with small entropy differences (Δ ≤ 0.03). The profiles’ shape and substantive interpretations remained consistent across scaling conditions, reinforcing the robustness of the study’s conclusions.

3.1. Measures

The instruments were chosen based on existing empirical research that supports their reliability and validity in the relevant scholarly literature.

The Schwartz Cultural Value Orientation is assessed using the Schwartz Value Survey (SVS), which consists of a 57-item questionnaire where respondents rate the importance of various values in their lives on a nine-point Likert scale (Schwartz 2021). The scale ranges from (−1) (minus one) (“contrary to my values”) to 7 (“of supreme importance”), with a midpoint of 3 indicating that a value is considered important. A score of 0 means the value is not relevant as a guiding principle (Schwartz 2021). The respondents rank their guiding principles in their lives and answer “What values are important to ME as guiding principles in MY life, and what values are less important to me?” The survey evaluates values such as equality, freedom, social justice, and environmental protection, categorizing them into seven higher-order orientations: Embeddedness, Intellectual Autonomy, Affective Autonomy, Hierarchy, Egalitarianism, Mastery, and Harmony (Schwartz et al. 2012). The SVS was chosen over the Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ) due to its focus on the cognitive importance of values, aligning with the study’s emphasis on absolute value endorsement (Schwartz 2006). The internal consistency of the SVS is confirmed, with Cronbach’s α values ranging from 0.45 to 0.76 (median = 0.66), indicating reliable measurement across different domains. Additionally, an internal consistency and composite reliability was conducted for Schwartz 7 dimensions. Please see Table 1.

Table 1.

Schwartz (7) Cultural-Level Dimensions: Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega.

3.1.1. Measuring Hofstede’s Individual Cultural Dimensions

Two instruments were used to measure Hofstede’s six cultural dimensions on an individual level. Power Distance, Uncertainty Avoidance, Individualism-Collectivism, Masculinity-Femininity and Time Orientation were administered through the scale developed by Yoo et al. (2011). Indulgence-Restraint was administered using Heydari et al. (2021). Both scales use a five-point Likert scale.

Yoo et al. (2011) developed a 26-item scale, based on the Hofstede national-level CVSCALE scale, to assess an individual’s cultural orientations as reflected on Hofstede’s (1980, 2001) renowned five dimensions of culture. This tool allows us to assess the cultural orientations of individuals and to use primary data instead of cultural stereotypes. CVSCALE exhibited appropriate reliability and validity. Cronbach alpha reliability, ranging from 0.74 to 0.91, was achieved for the cultural dimensions. The cultural dimensions items were evaluated using five-point Likert-type scales anchored as 1 “very unimportant” and 5 “very important” for the long-term orientation dimension, and 1 “strongly disagree” and 5 “strongly agree” for the remaining dimensions. Sample questions include: For power distance “People in higher positions should make most decisions without consulting people in lower positions;” for uncertainty avoidance “It is important to have instructions spelled out in detail so that I always know what I am expected to do;” for collectivism/individualism “Individuals should sacrifice self-interest for the group;” for long-term orientation “How closely do you associate with the following qualities? Careful management of money (Thrift);” for masculinity/femininity “It is more important for men to have a professional career than it is for a woman.”

3.1.2. Hofstede’s Dimension of Indulgence vs. Restraint (Heydari et al. 2021)

Yoo et al. (2011) developed the CVSCALE, i.e., Hofstede’s scale at the individual level with good reliability and validity. At the time, Hofstede’s framework consisted of five dimensions. The CVSCALE did not include the sixth dimension (i.e., indulgence vs. restraint) as a cultural value, on different aspects of indulgent behavior. It fills a theoretical gap and provides a valid and reliable scale to measure individual-level indulgence vs. restraint. This research clarifies and includes the distinct and important role of individual-level indulgence vs. restraint, demonstrating that measuring culture at the individual level is more accurate and valid than using national-level scores; it avoids a possible ecological fallacy, and it is in line with the individual-level psychological approach. Cronbach’s α reliability for individual-level indulgence was 0.839. Respondents were required to indicate the degree to which they agree with each of the six items, based on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1, indicating strongly disagree, to 7, indicating strongly agree. Sample questions include: “Desires, especially with respect to sensual pleasure should not be suppressed” and “Gratification of desires should not be delayed.” Additionally, an internal consistency and composite reliability was conducted for Hofstede 6 dimensions. Please see Table 2.

Table 2.

Hofstede Cultural Dimensions: Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega.

3.1.3. Reliability of Measurement as a Basis for Interpretation

The internal consistency of both Schwartz and Hofstede dimensions demonstrated a robust level, confirming the reliability of the composite indicators. The analysis revealed high reliability coefficients for Embeddedness (α = 0.92; ω = 0.91), Egalitarianism (α = 0.87; ω = 0.86), Indulgence (α = 0.91; ω = 0.90), and Individualism (α = 0.90; ω = 0.89), indicating strong internal consistency across these constructs. Dimensions exhibiting moderate reliability, including Hierarchy (α = 0.78; ω = 0.78) and Long-/Short-Term Orientation (α = 0.77; ω = 0.76), were found to be within acceptable limits for interpretation at the group level. The coefficients established here serve as a psychometric basis for understanding contrasts between profiles. Enhanced reliability of dimensions contributes to increased inferential confidence, especially in cases where distinctions between profiles are nuanced. In instances of lower reliability, it is essential to qualify interpretations and enhance them with effect size estimates and confidence intervals. The consistency observed between Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega across all dimensions provides additional evidence for the assumption of unidimensionality within each construct, thereby affirming the appropriateness of these composites for LPA.

3.2. Analysis

This study adopts a person-centered approach to analyze the interrelations between Schwartz’s value orientations and Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, utilizing LPA to identify culturally relevant profile differences. LPA is a person-oriented methodology that contrasts with traditional variable-oriented methods by focusing on individual patterns and interactions among multiple characteristics (Ferguson et al. 2020). The analysis aimed to categorize populations into distinct latent profiles based on their responses to cultural dimensions and values, enhancing the understanding of cultural and value orientation profiles. (data and code available upon request). Before conducting the LPA, the study adhered to validated theoretical frameworks, Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and Schwartz’s value orientations, and cross-scale harmonization or z-score standardization were not conducted. This decision preserved the original metrics, enhancing the interpretability of latent profiles and preventing distortion of within-scale variance (Pastor et al. 2007; Masyn 2013; Nylund et al. 2007). Best practices indicate that standardization is only essential when integrating indicators from different constructs into a single latent model (Morin et al. 2016; Spurk et al. 2020). The analysis concentrated on modeling latent profiles within homogeneous measurement systems, making scale harmonization unnecessary and potentially counterproductive. This methodological choice aligns with recent recommendations for transparent and replicable reporting of data preprocessing in person-centered research (Aguinis et al. 2013).

Model Selection Criteria

Latent profile analyses (LPA) were performed independently for each cultural value framework (Schwartz and Hofstede) to discern subgroups according to countries’ cultural value orientations. For each framework, a range of models was estimated, delineating between 2 and 9 latent profiles, in accordance with established practices for mixture modeling (Masyn 2013; Nylund et al. 2007). Model selection utilized a multi-criteria decision framework that integrated statistical fit indices, classification quality, and substantive interpretability. The statistical fit was assessed utilizing the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and log-likelihood. Reduced values of AIC and BIC, signify superior relative fit, whereas entropy serves to evaluate classification accuracy, with values of 0.80 or above interpreted as indicative of high classification quality. The Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT) was employed to compare nested models that differ by a single profile. A substantial BLRT p-value was regarded as support for the model with a greater number of profiles (Nylund et al. 2007). Due to the potential for AIC and BIC to diminish with the addition of profiles in extensive samples, the BLRT, along with considerations of parsimony and interpretability, was emphasized in establishing the final number of profiles.

All analyses were performed in R (version 4.1.2) utilizing the tidyLPA package (version 1.1.2). Models were estimated using maximum likelihood with the package’s default optimization parameters. A fixed random seed (set.seed(12345)) was employed to guarantee reproducibility before estimation, and tidyLPA utilized a standard multiple-random-start methodology, comprising 50 initial random initiations and 10 final-stage optimizations. Solutions were preserved solely if the optimal log-likelihood value was consistently reproduced during final-stage optimizations, thus mitigating the risk of local maxima. Indicators were examined in their original, unstandardized format, consistent with the default behavior of the package and to maintain absolute levels of value endorsement for interpretative purposes (Hofstede et al. 2010; Schwartz 2012; Yoo et al. 2011).

The LPA models presumed local independence, with covariances among indicators set to zero within profiles and indicator variances estimated freely across profiles. Missing data were addressed through listwise deletion, in accordance with the existing functionality of tidyLPA, which lacks support for full-information maximum likelihood. To evaluate the stability and robustness of the profile solutions, each model was estimated repeatedly with various random initializations. The stability was assessed by examining the consistency of log-likelihood values, entropy, and profile size proportions across multiple runs.

Profile-specific means were calculated for all indicators for each selected model. The uncertainty associated with these estimates was measured through nonparametric bootstrap resampling at the individual respondent level. A substantial quantity of bootstrap samples (B) was generated, the LPA model was re-estimated, and profile-specific means were recalculated for each resample. The percentile method was subsequently employed to calculate 95% confidence intervals for each indicator within each profile. Indicators of model adequacy comprised significant reductions in BIC and AIC up to the chosen number of profiles, elevated entropy values reflecting distinct separation among profiles, and consistent profile sizes and means across random initiations and bootstrap samples. Profiles were illustrated through plots of profile-specific means, accompanied by error bars that denote the bootstrap-derived 95% confidence intervals. The visualizations were created independently for the Schwartz and Hofstede frameworks and subsequently juxtaposed to enable cross-framework comparisons. The final model selection for each framework was determined by the convergence of statistical fit indices, BLRT outcomes, classification quality, parsimony, theoretical coherence of the profiles, and the exclusion of very small or unstable classes, in accordance with best practices in latent profile modeling (Masyn 2013; Nylund et al. 2007).

All LPAs were executed independently for each cultural value framework utilizing established country-level scores for Hofstede’s cultural dimensions (Hofstede et al. 2010) and Schwartz’s value orientations (Schwartz 2012). Scores were intentionally not ipsatized to preserve information regarding absolute levels of value endorsement, thereby improving the interpretability of differences across profiles (Fischer 2017; Schwartz 2006). Research questions 1 and 2 utilized the same modeling approach to evaluate the emergence of culturally significant profiles based on individual-level variations. LPA was employed to assess both the quantity and the configuration of latent cultural profiles extracted from the data for each question.

RQ 1: What cultural profiles emerge from Schwartz’s seven value orientations?

The first research question utilized Schwartz’s cultural value orientations to analyze individual-level scales, focusing on how individuals perceived various attributes and the resulting profiles. LPA was performed on the seven dimensions. Subsequently, these profiles were evaluated to determine their characteristics and then analyzed to understand how individuals perceived one or more attributes, as well as the profiles that were produced. Model selection (R package 2021) was based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC) (Akaike 1974), Bayesian information criterion (BIC) (Schwartz 1978), entropy (Celeux and Soromenho 1996), and a bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (McLachlan 1987). Lower values for the AIC, BIC, and a-BIC indicate better model fit; higher values for entropy indicated higher classification utility; and significant bootstrapped likelihood ratio test p-values indicated better model fit with the inclusion of an additional profile. Heavy emphasis was placed on the utility and theoretical interpretation of a solution.

RQ 2: What cultural profiles emerge from Hofstede’s individual-level six value dimensions?

An identical process as described in RQ 1 was conducted for RQ 2 addressed by Hofstede’s cultural attributes on the individual level. Two instruments were used to measure Hofstede’s six cultural dimensions Yoo et al. (2011) and Heydari et al. (2021). LPA was performed on the six cultural dimensions. Subsequently, these profiles were evaluated to determine their characteristics and then analyzed to understand how individuals perceived one or more attributes, as well as the profiles or that were produced.

RQ 3: What patterns emerge when crosstab Schwartz and Hofstede’s profiles?

The third research question explores the potential relationships between the latent profiles determined through Schwartz’s and Hofstede’s cultural value frameworks. It specifically assesses the degree of congruence between the individual-level value profiles derived from Schwartz’s model and those obtained from Hofstede’s model. Thus, a cross-tabulation analysis was conducted on the latent profile memberships obtained from research questions 1 and 2. This method enables the examination of the relationship between individuals’ classifications within a single framework, such as one that highlights Embeddedness and Hierarchy, and their classifications within another framework characterized by high Power Distance or low Individualism. The objective is to uncover systematic patterns of convergence or divergence that can illustrate the structural and conceptual connections between these two significant frameworks of cultural values. Moreover, pinpointing areas of convergence (e.g., where high Embeddedness coincides with high Power Distance) or divergence (e.g., where a Schwartz autonomy profile fails to align with Hofstede individualism) will clarify the degree to which the two models embody distinct or overlapping frameworks of cultural significance. This analysis establishes a basis for evaluating the potential integration of these frameworks in person-centered research, or whether they present complementary yet distinct perspectives.

4. Results

LPA was used to identify subgroups within the sample based on patterns across Schwartz and Hofstede frameworks. The optimal number of latent profiles was calculated using model fit indices, entropy values, and profile interpretability. The findings show that cultural variation within the U.S. is patterned by latent profiles, not adequately represented by national averages. All latent profile analyses were performed on non-ipsatized data to preserve absolute variance across individuals, ensuring that the resulting profiles reflect meaningful differences in overall value endorsement rather than relative intra-individual rankings.

Table 3 (Schwartz) encapsulate the comparative fit statistics for the latent profile models. Despite the continued decline of AIC and BIC with an increasing number of classes, the BLRT results endorsed the retention of these solutions up to k = 7 and k = 6, respectively, beyond which the enhancement in fit was not statistically significant. The entropy values for the chosen models demonstrated satisfactory classification accuracy, and the profiles in both solutions were theoretically consistent and substantively distinct. The combined evidence supported the retention of the seven-class Schwartz solution and the six-class Hofstede solution.

Table 3.

Schwartz model fit indices and classification quality across latent profile solutions (k = 2–9).

RQ 1: What cultural profiles emerge from Schwartz’s seven value orientations?

LPAs were conducted and analyzed to determine the optimal number of profiles. The findings of these analyses, performed for profile models ranging from 2 to 9, are presented in Table 1, which outlines the fit criteria for each profile model. The determination of the optimal number of profiles was based on a comparative assessment of the fit criteria, as outlined in the table. Statistical metrics including Log Likelihood, AIC, BIC, and entropy indicated that model fit enhanced with a greater number of profiles, peaking at the seven-profile solution, beyond which the fit decreased (Lawrence and Zyphur 2011). This indicates that the seven-profile solution is optimal for adequately representing the data. Schwartz’s seven-profile solution not only provided the optimal fit but also offered clear conceptual distinctions among clusters of motivational values.

The analysis revealed that both the AIC and BIC values decreased consistently across models, indicating a better fit with an increasing number of profiles. High entropy values (0.82 to 0.92) confirmed strong classification accuracy, surpassing the acceptable threshold of 0.80 for distinguishing profiles. The BLRT showed significant results (p = 0.010) for models with up to six profiles but was not significant for the seven-profile model (p = 0.455), suggesting no substantial improvement in fit with the additional profile. Despite this, the seven-profile solution was chosen as the final model based on a comprehensive evaluation of statistical fit, entropy, interpretability, and theoretical coherence. The AIC (10.036.37) and BIC (10.308.47) reached their lowest values at this solution before stabilizing. The seventh profile added a unique and interpretable subgroup, enhancing the model’s conceptual framework without introducing minor or unstable profiles. This supports the recommendation of prioritizing parsimonious models that are theoretically interpretable over those with slightly superior fit but unstable higher-order solutions (Nylund et al. 2007; Morin et al. 2016). Model selection was informed by statistical metrics and interpretability standards, following established protocols (Nylund et al. 2007; Masyn 2013; Morin et al. 2016).

The study identified seven distinct value orientation profiles based on participants’ responses across seven dimensions: Mastery, Affective Autonomy, Intellectual Autonomy, Egalitarianism, Harmony, Embeddedness, and Hierarchy, aligning with Schwartz’s universal human values (Schwartz 1992). The profiles were categorized into three thematic groups: those supportive or indifferent to hierarchy (Profiles 3, 4, 5, and 7), those rejecting hierarchy (Profiles 1 and 2), and an apathetic profile (Profile 6). The identified profiles highlight the varying ways through which individuals give precedence to these values, suggesting a complex interplay between personal values and cultural context and revealing insights into how value priorities differ among individuals across cultures. Profiles supporting or indifferent to hierarchy exhibited varying degrees of endorsement for structured social roles. Profile 7 (n = 200; 33.6%) the predominant profile demonstrated uniformly elevated scores across all dimensions, including Hierarchy (M = 5.741), Egalitarianism (M = 6.116), and Intellectual Autonomy (M = 5.926). This pattern reflects a value orientation that harmonizes individual liberties with social order, aligning with a modern institutionalist perspective that advocates for autonomy within an organized society (). Profile 5 (n = 120; 20.2%) exhibited moderate scores across dimensions, with marginally lower endorsement of Affective Autonomy (M = 3.953) and Hierarchy (M = 4.814). These individuals may exhibit a moderately conforming orientation, appreciating structure and independence without a strong affiliation to either extreme (Bilsky et al. 2011). Profile 4 (n = 88; 14.8%) exhibited comparatively low scores across all values, including Hierarchy (M = 3.874) and Mastery (M = 4.169). This indicates a low-value differentiation profile, potentially signifying value ambivalence, or normative conformity without robust internalization of either autonomy or tradition-based values (Boer and Fischer 2013; Spini and Doise 1998). Profile 3 (n = 59; 9.9%) achieved elevated scores in all dimensions, specifically Hierarchy (M = 6.409), Embeddedness (M = 6.571), and Intellectual Autonomy (M = 6.640). This profile seems to embody cultural integration with individuals who harmonize authority and personal freedom (Roccas et al. 2002).

In contrast, Profiles 1 (n = 37; 6.2%) and 2 (n = 44; 7.4%) exhibited resistance to hierarchy, albeit with divergent motivational frameworks and value priorities. Profile 1 (n = 37; 6.2%) exhibited minimal endorsement of Hierarchy (M = 2.501) alongside elevated scores in Intellectual Autonomy (M = 6.339) and Embeddedness (M = 6.374). These individuals seem to prioritize self-direction in conjunction with robust social connections, reflecting the communitarian values observed in democratic egalitarian societies (Inglehart and Welzel 2005). Profile 2 (n = 44; 7.4%) similarly rejected hierarchy (M = 1.883) but significantly differed from Profile 1 due to their low endorsement of Mastery (M = 3.160), Affective Autonomy (M = 2.963), and additional values. This profile may reflect a disengaged or alienated orientation, consistent with low civic engagement and a critical stance toward dominant cultural frameworks (Schwartz 2006). Profile 6 (n = 47; 7.9%) exhibited persistently low mean scores across all dimensions, specifically Mastery (M = 2.858), Hierarchy (M = 2.778), and Intellectual Autonomy (M = 3.055). This profile indicates a weak identification with any value orientation and may signify value apathy, a condition linked to low motivation, detachment, or even anomie (Srole 1956). This profile is significant in discussions regarding marginalization or cultural disorientation in transitional societies. Essentially, these findings stress the multifaceted character of value systems and their correspondence with social orientation. Some profiles (e.g., Profile 7) illustrate the coexistence of autonomy and hierarchy, while others (e.g., Profiles 1 and 2) exhibit differing levels of resistance to authority. The generalized disengagement of Profile 6 highlights the necessity of recognizing value apathy as a unique sociopsychological phenomenon. The findings substantiate theories of value pluralism (Rohan 2000; Hitlin and Piliavin 2004) and cultural hybridity (Berry 1997), indicating that individuals do not conform to a singular axis of individualism or collectivism but rather develop intricate, context-dependent value identities shaped by structural, cultural, and experiential influences. The findings reveal that a significant majority of participants support hierarchy to differing extents, while a smaller segment opposes hierarchy, favoring egalitarian and autonomy principles. Additionally, there exists a minor group exhibiting low-intensity endorsements across the various value domains. Table 4 reports the means and standard errors of each indicator variable for every latent profile, together with profile sizes and proportions. These values represent the response means and their standard errors, used to interpret the substantive meaning of each profile.

Table 4.

Schwartz Profiles Means and Standard Error.

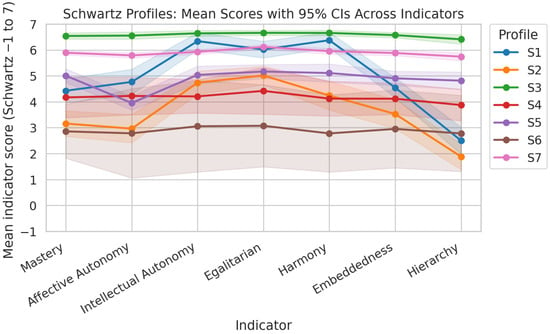

The analysis of Schwartz value profiles, as depicted in Figure 1, reveals distinct patterns of value endorsement among the seven identified profiles (S1–S7) across various higher-order value indicators, including Mastery, Affective Autonomy, Intellectual Autonomy, Egalitarian, Harmony, Embeddedness, and Hierarchy. Each profile’s mean scores are represented with 95% confidence intervals, which not only provide a visual representation of the data but also enhance the transparency and reproducibility of the findings (Masyn 2013; Morin et al. 2016).

Figure 1.

Schwartz Profile Mean Scores with 95% CI.

The profiles can be categorized based on their attitudes towards hierarchy. Profiles S1 and S2 are characterized as “profiles disliking hierarchy,” as they exhibit low scores on Hierarchy and Embeddedness while showing higher scores on Egalitarian; Harmony; and Autonomy indicators. This configuration suggests a strong preference for equality and personal freedom; with their confidence intervals indicating a clear divergence from more hierarchical profiles (S3; S4; S5; S7). In contrast; the “profiles neutral/favoring hierarchy” profiles (S3; S4; S5; and S7) display higher scores on Hierarchy and Embeddedness; often coupled with elevated Mastery scores; while their scores on Egalitarian and Autonomy are comparatively lower. This indicates a greater acceptance of traditional power structures and role obligations; distinguishing them from the egalitarian leanings of S1 and S2. Profile S6 stands out as an “apathetic profile,” characterized by relatively flat scores across the value indicators; clustering around the midpoint. The overlapping confidence intervals with other profiles suggest a lack of strong endorsement or rejection of any specific value dimension; indicating a less differentiated value structure. The findings as presented in Figure 1 indicate that Schwartz values are organized into coherent constellations rather than existing as isolated dimensions.

RQ 2: What cultural profiles emerge from Hofstede’s individual-level six value dimensions?

The study utilized LPA based on Hofstede’s (2011) framework to investigate cultural profile differences related to individual variations in cultural dimensions. The analysis considered up to a nine-profile solution, with fit indices such as Log Likelihood, AIC, BIC, and entropy demonstrating improved model fit up to the sixth-profile solution, after which fit declined. Thus, the six-profile solution was identified as optimal for data representation (Lawrence and Zyphur 2011). Fit statistics presented in Table 3 indicated that AIC and BIC values decreased consistently with the addition of profiles, a common outcome in mixture modeling due to increased complexity. The final profile count was determined by balancing fit improvement and parsimony, with the six-profile solution offering a favorable balance of statistical fit (BIC = 8133.771, entropy = 0.846306) and interpretability. Higher-profile solutions resulted in redundant subgroups, supporting the preference for parsimonious models (Nylund et al. 2007; Morin et al. 2016).

Model selection conformed to optimal methodologies, integrating statistical fit indices with substantive interpretability (Masyn 2013; Morin et al. 2016; Nylund et al. 2007). Across solutions, fit indices typically enhanced with the inclusion of additional profiles, while entropy values ranging from 0.76 to 0.85 signified satisfactory classification accuracy. The Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT) was significant for the two- to five-profile solutions, demonstrating that models with up to five profiles exhibited a significantly superior fit compared to the models with one fewer profile. The BLRT comparing the six-profile solution to the five-profile solution was not significant, indicating no evident statistical benefit in incorporating a sixth profile. Despite the BLRT for the seven-profile model being significant, AIC and BIC values began to stabilize, and higher-order solutions yielded smaller, less stable classes with diminished entropy and restricted substantive interpretability. Given the declining enhancements in AIC/BIC, satisfactory entropy, the nonsignificant BLRT at six profiles, and the theoretical consistency of the profile structure, the six-profile solution was maintained as the most parsimonious and substantively meaningful representation of Hofstede’s cultural value data. The alignment of statistical and theoretical criteria endorses the six-profile model as the optimal solution. Table 5 (Hofstede) encapsulate the comparative fit statistics for the latent profile models

Table 5.

Hofstede model fit indices and classification quality across latent profile solutions (k = 2–9).

The analysis identified six distinct cultural orientation profiles based on participant responses across six dimensions of Hofstede’s (2001) national culture framework: Power Distance, Uncertainty Avoidance, Individualism-Collectivism, Masculinity-Femininity, Time Orientation, and Indulgence-Restraint. These profiles offer a person-centered viewpoint on how individuals organize cultural values, highlighting intra-cultural diversity and surpassing simplistic national aggregates (Taras et al. 2009; Fischer and Schwartz 2011). The total sample comprised 595 participants, unevenly allocated across profiles, with the largest cluster accounting for 27.6% and the smallest for 10.3% of the sample. Profiles were categorized into three principal orientations based on Power Distance: those neutral or favorable towards hierarchy (Profiles 3 and 6), (2), those opposed to power distance (Profiles 1, 2, and 5), and an apathetic profile (Profile 4) characterized by minimal endorsement across most dimensions (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Hofstede Profiles Means and Standard Error.

Profiles Favorable or Neutral Toward Power Distance. Profile 6 (n = 94; 15.8%) exhibited the highest Power Distance score (M = 4.016, SE = 0.072), indicating a strong endorsement of hierarchical relationships and authority. This group demonstrated high scores in Uncertainty Avoidance (M = 4.477) and Time Orientation (M = 4.397), reflecting a preference for predictability, long-term planning, and structured institutions. These patterns correspond with cultures that emphasize hierarchical status, social regulation, and continuity (House and Javidan 2004; Schwartz 2006). Profile 3 (n = 164; 27.6%), the largest subgroup, demonstrated moderate acceptance of Power Distance (M = 3.199), reflecting a flexible disposition toward authority. The scores for Masculinity-Femininity (M = 3.562) and Indulgence-Restraint (M = 3.429) were moderate, while Uncertainty Avoidance (M = 3.828) and Time Orientation (M = 3.785) were relatively high. This profile may denote conformist pragmatists; individuals who prioritize stability while acquiescing to moderate authority (Hofstede 2001).

Profiles Disliking Power Distance. Profiles 1, 2, and 5 demonstrated low Power Distance scores (M = 1.811 to 1.973), signifying egalitarian inclinations and resistance to rigid authority hierarchies. However, their configurations differed across various dimensions, reflecting unique motivational frameworks and cultural priorities. Profile 2 (n = 111; 18.7%) demonstrated the lowest Power Distance (M = 1.811), alongside relatively high Collectivism (M = 3.891), and reduced Masculinity (M = 1.578). Participants demonstrated high scores in Uncertainty Avoidance (M = 4.441) and Time Orientation (M = 4.386). This group likely embodies cooperative, security-oriented egalitarians, associated with feminine collectivist cultures that emphasize caregiving, harmony, and group loyalty over competition (Bilsky et al. 2011; Hofstede 2001). Profile 1 (n = 92; 15.5%) similarly rejected Power Distance (hierarchical authority) (M = 1.925) while supporting reduced Individualism (M = 2.113) and moderate Masculinity (M = 2.090). The amalgamation signifies anti-authoritarian communitarians who emphasize group cohesion and humility while promoting egalitarian social structures characteristics commonly found in participatory or democratic collectivist settings (Inglehart and Welzel 2005). Profile 5 (n = 73; 12.3%) demonstrated low Power Distance (M = 1.973), higher Individualism (M = 4.185), and high Masculinity (M = 3.971). This pattern suggests that individuals are achievement-oriented and prioritize autonomy, favoring independence and personal success over hierarchical frameworks. This group may align with liberal individualists who prioritize performance and control over outcomes while resisting centralized authority (Triandis 1995).

Apathetic Profile. Profile 4 (n = 61; 10.3%) demonstrated consistently low scores across all dimensions, namely Power Distance (M = 2.515), Individualism (M = 2.822), and Masculinity (M = 2.666). Uncertainty Avoidance (M = 3.005) and Time Orientation (M = 3.147) exhibited moderate levels. This profile may suggest value apathy or disengagement, marked by individuals exhibiting minimal adherence to established social norms or guiding value systems. These profiles have been linked to anomic conditions, social marginalization, or ambivalence towards cultural norms (Srole 1956; Rohan 2000).

Essentially, these findings support the concept that cultural values operate at an individual level with multidimensional variability, rather than solely as national averages. Rather than adhering to simplistic dichotomies (e.g., collectivism versus individualism), individuals often integrate diverse cultural values in complex and occasionally contradictory ways (Vignoles et al. 2016). The presence of an apathetic profile highlights the need to examine value disengagement as an independent social and psychological phenomenon. Such configurations may signify alienation, uncertainty, or cultural fragmentation, especially in transitional or multicultural contexts (Berry 1997; Schwartz 2006). The results underscore the efficacy of person-centered approaches in cultural psychology and sociology, offering a more profound comprehension of the diversity of cultural orientations among populations. Please see Table 6 for the profiles.

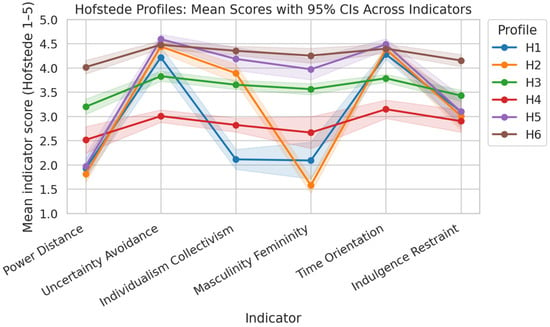

Figure 2 illustrates these profiles through mean scores with 95% confidence intervals, providing a visual representation of the convergence and divergence among the different cultural dimensions. The shaded bands around each line in the figure indicate the uncertainty of the estimated means, enhancing the transparency and reproducibility of the findings (Masyn 2013; Morin et al. 2016).

Figure 2.

Hofstede Profile Mean Scored with 95% CI.

The empirical categorization of profiles is segmented into three primary classifications: profiles that oppose Power Distance, profiles that are neutral or supportive of Power Distance, and an indifferent profile. Profiles 1, 2, and 5 exhibit a “dislike for Power Distance,” with mean scores ranging from 1.8 to 2.0, markedly below the scale’s midpoint. The confidence intervals for these profiles do not intersect with those of the higher Power Distance profiles, indicating a definitive rejection of pronounced hierarchies and significant status disparities. These profiles demonstrate elevated levels of Uncertainty Avoidance and Long-Term Orientation, indicating a preference for explicit regulations, predictability, and future-oriented planning. Conversely, Profiles 3 and 6 are classified as “neutral/favoring Power Distance.” The profiles exhibit mean scores at or above the midpoint for Power Distance, with confidence intervals clearly distinct from those of the disliking profiles. Individuals in these profiles typically endorse hierarchical relationships, often integrating this acceptance with a performance-driven and systematic approach. Furthermore, they exhibit heightened levels of Uncertainty Avoidance and Time Orientation, as well as increased scores in Individualism and Masculinity in certain instances. Finally, Profile 4 is designated as the “apathetic profile,” characterized by moderate and relatively uniform scores across the different dimensions.

Values are not isolated constructs; they constitute coherent constellations that mirror broader cultural profiles. This concept is corroborated by the data depicted in Figure 2, which demonstrates the clustering of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions into discrete value profiles, with Power Distance serving as the primary dimension that differentiates groups, while Uncertainty Avoidance and Time Orientation are typically elevated across profiles.

RQ 3: What patterns emerge when crosstab Schwartz and Hofstede’s profiles?

The analysis of cultural profiles based on Hofstede’s and Schwartz’s frameworks reveals intricate relationships between individual preferences for power distance and hierarchical structures. The study identified six distinct profiles for Hofstede (labeled H1 to H6) and seven for Schwartz (labeled S1 to S7), and a cross-tabulation of these profiles was conducted to explore the distribution of participants among them. The results, as illustrated in Table 7, highlight significant patterns in how individuals align with these profiles, indicating both congruence and divergence in cultural values.

Table 7.

Crosstabs of Schwartz and Hofstede latent profiles.

Profiles H1 and H2, characterized by a rejection of power distance, show a relatively even distribution between Schwartz profiles S1, which also rejects hierarchy, and S7, which supports it, albeit with a slight preference for S7. Conversely, profiles H3 and H5, which endorse hierarchy, along with H6, the apathetic profile, exhibit notable clustering. Specifically, H3 is predominantly found in Schwartz profiles S4, S5, and S7, all of which favor hierarchical structures. H5, which opposes power distance, is almost exclusively associated with S7, while H6, which supports power distance, is primarily located within profiles S3, S5, and S7. The apathetic profile H4 is more evenly distributed but shows a significant presence in S6, its corresponding apathetic profile in Schwartz’s framework. This distribution suggests a partial alignment between the two sets of profiles, with certain Hofstede profiles closely mirroring specific Schwartz profiles, while others display a more hybrid relationship.

The analysis further identifies three principal themes concerning Hofstede’s cultural dimensions in relation to Schwartz’s value profiles. Profiles H3 and H6 demonstrate a positive inclination towards power distance, aligning with Schwartz profiles S3, S4, S5, and S7, which advocate for authority and social hierarchies. The findings indicate both concordance and discordance among the profiles, particularly highlighting the correlation between H6 and Schwartz profiles S3 and S4, suggesting shared behavioral traits. In contrast, profiles H1, H2, and H5, which exhibit low power distance preferences, align with Schwartz profiles S1 and S2, indicating a shared aversion to hierarchy and a preference for equality and decentralized authority. The neutral stance of H4 on power distance corresponds with Schwartz profile S6, indicating a lack of strong cultural coherence or guiding principles.

When considered collectively, the visual representations of Schwartz and Hofstede converge on a shared underlying structure. First, Schwartz profiles that reject hierarchy (S1, S2) align conceptually with Hofstede profiles that also reject power distance (H1, H2, H5). Both frameworks reflect a rejection of hierarchical relations while simultaneously valuing order and structure, as evidenced by related Schwartz dimensions and Hofstede’s high Uncertainty Avoidance and Time Orientation. Second, Schwartz profiles that are neutral or favor hierarchy (S3, S4, S5, S7) correspond to Hofstede profiles that are neutral or favor These groups: Accept or favor hierarchical distinctions (higher Schwartz hierarchy/embeddedness; higher Hofstede Power Distance). Combine hierarchy with strong appreciation for norms, planning, and sometimes performance (elevated mastery in Schwartz; elevated Uncertainty Avoidance, Time Orientation, and sometimes Masculinity and Individualism in Hofstede). Third, the Schwartz apathetic profile (S6) parallels the Hofstede apathetic profile (Profile 4), with both visuals depicting: Midrange, relatively flat scores across value dimensions. A less crystallized or lower-salience value configuration. The aligned results show that hierarchy vs. equality is the primary organizing dimension in both frameworks, while preferences for structure, predictability, and long-term orientation are relatively widespread, cutting across both hierarchy-accepting and hierarchy-rejecting groups.

The analysis of cultural dimensions through Hofstede’s and Schwartz’s profiles reveals intricate patterns of alignment and divergence among various participant profiles. The study identifies six distinct Hofstede profiles (H1 to H6) and seven Schwartz profiles (S1 to S7) and employs cross-tabulation to explore the distribution of individuals across these profiles. The findings, as presented in Table 5, illustrate significant trends in how these profiles interact, particularly in relation to power distance and hierarchy. Profiles H1 and H2, characterized by a general aversion to power distance, show a relatively balanced distribution between Schwartz profiles S1, which rejects hierarchy, and S7, which supports it. This distribution indicates a nuanced relationship where individuals with low power distance preferences do not strictly conform to a single hierarchical stance. Conversely, profiles H3 and H5, which endorse hierarchy, alongside H6, the apathetic profile, exhibit a more pronounced clustering. Specifically, H3, which supports power distance, is predominantly associated with Schwartz profiles S4, S5, and S7, all of which favor hierarchical structures. H5, despite opposing power distance, is almost exclusively found in S7, suggesting a complex interplay between personal values and hierarchical acceptance. Meanwhile, H6, which also favors power distance, is primarily linked to profiles S3, S5, and S7, reinforcing the notion that individuals who endorse power distance tend to align with hierarchical values. The apathetic profile H4 presents a more varied distribution, though it is notably prevalent in S6, its corresponding apathetic Schwartz profile. This suggests that H4 may represent a distinct subgroup that lacks strong cultural coherence or guiding principles. The analysis further identifies three principal themes regarding Hofstede’s cultural dimensions in relation to Schwartz’s value profiles. Notably, profiles H3 and H6 demonstrate a positive inclination towards power distance, aligning with Schwartz profiles S3, S4, S5, and S7, which advocate for authority and social hierarchies. The findings reveal both concordance and discordance among the profiles, highlighting significant correlations between profile H6, which endorses power distance, and profiles S3 and S4, which advocate hierarchy, suggesting related behavioral traits. The apathetic profile H4 displays a varied distribution, indicating it may represent a distinct subgroup. Profiles H1, H2, and H5 display low power distance preferences, aligning with Schwartz profiles S1 and S2, indicating a dislike for hierarchy and a heightened inclination towards equality and decentralized authority. Ultimately, the neutral stance of H4 on power distance corresponds with Schwartz profile S6, the apathetic profile, signifying a deficiency in strong cultural coherence or guiding principles.