Abstract

Despite increasing attention to gender disparities in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) fields, little is known about how these dynamics manifest within interdisciplinary public health domains such as Occupational Safety and Health (OSH). This study presents a bibliometric analysis of 144 empirical publications on work-related stress management interventions published between 1977 and 2023. Drawing from five major academic databases, we examine gender differences in authorship patterns, scientific productivity, citation impact, and collaboration patterns, with a focus on first, corresponding, and last authorship as indicators of contribution and leadership. Our findings reveal a significant increase in women’s participation over time, particularly in first authorship roles, while a persistent gender gap in senior and supervisory positions favors male researchers, in line with the leaky pipeline framework. Productivity, citation rates, and cooperation patterns suggest positive trends toward gender equity, though subtle structural disparities remain. We discuss implications for inclusive research environments, equitable authorship recognition, and the design of gender-sensitive science policy in occupational health. This study contributes to understanding the gendered contours of scientific influence within OSH and highlights the need for more inclusive academic ecosystems.

1. Introduction

Bibliometric studies offer valuable insights into the past, present, and future directions of a specific research field (Zupic and Čater 2015). Such data not only help in advising postgraduate students or early-career faculty but also serve as a valuable tool for understanding publishing dynamics in science. For instance, these studies may provide a deeper understanding of gender biases among disciplines, which can be useful for formulating policies that promote gender equality in academia.

A substantial body of bibliometric research has addressed gender disparity in science and scholarly work (Halevi 2019; Huang et al. 2020; Larivière et al. 2013; Sánchez-Jiménez et al. 2024). Despite significant progress toward gender equality in recent years, women remain underrepresented in science (Astegiano et al. 2019; Holman et al. 2018). The last United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Institute for Statistics (2021) report indicated that 33.3% of researchers worldwide are women, while this proportion falls in senior leadership roles; women represent less than 25.0% of heads of institutions in the higher education sector at the European level (European Commission 2021b). Beyond this representation, gender biases and inequalities in hiring, funding, salary, tenure, and promotion persist, further exacerbating the challenges faced by women in contemporary science (Ceci et al. 2023; Gruber et al. 2021; Llorens et al. 2021; Roper 2019).

Traditionally, research has focused on the “productivity puzzle” to explain the gender imbalances in the scientific field, particularly the gender productivity gap (Cole and Zuckerman 1984; Huang et al. 2020; Larivière et al. 2013; Xie and Shauman 1998). As Astegiano et al. (2019) note, “women’s underrepresentation in science has frequently been associated with women being less productive than men” (p. 1). In academia, the relevance of scientific productivity has made it especially valuable to study the publication patterns of academic scientists and researchers (Barrios et al. 2013; Odic and Wojcik 2020). Among the myriad metrics available, the number of peer-reviewed research publications is one of the most widely used to measure scientific activity (Agarwal et al. 2016). Academic publishing plays a major role in securing grants, tenure, recognition of research periods, access to funding, and promotion decisions for university faculty. Therefore, the underrepresentation of women as authors in academic publications and in the most prestigious authorship positions could negatively impact their representation on university staff. Previous bibliometric studies (e.g., Larivière et al. 2013) support this view, showing that men, on average, publish more articles than women. Moreover, women are less likely to engage in collaborations that lead to publications and are less likely to hold the most prestigious authorship positions on a paper (West et al. 2013).

A substantial body of research has investigated these gender inequalities across multiple disciplinary fields (Astegiano et al. 2019; Larivière et al. 2011; Prpić 2002; Ruggieri et al. 2021; van Arensbergen et al. 2012), highlighting disparities in research productivity (Böhme et al. 2022; Larivière et al. 2013; König et al. 2015), authorship credit allocation (Bendels et al. 2017; Pagel et al. 2019; Shah et al. 2021), citation (König et al. 2015; Lerman et al. 2022; Rajkó et al. 2023), and cooperation patterns (Brück 2023; Naldi et al. 2004; West et al. 2013). Among these, Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) disciplines, portrayed as male-dominated fields (for a detailed description, see United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 2024), have received particular attention (Abramo et al. 2009; Aguinis et al. 2018; Halevi 2019; Holman et al. 2018; Kataeva et al. 2025). For instance, Huang et al. (2020) showed that male scientists publish an average of 13.2 papers over their careers, compared to 9.6 papers for female scientists, and that men’s publications receive approximately 30% more citations. In line with these findings, Li et al. (2025) reported a significant underrepresentation of women in both principal investigator roles and research team membership. Specifically, women principal investigators led only 23.3% of national projects and accounted for just 27.1% of authors involved in these project teams.

However, this trend is also evident in female-dominated disciplines, which makes it even more concerning. The case of psychology is highly illustrative, as the field is dominated by women at the undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral levels, but dominated by men at higher academic levels (Gruber et al. 2021; Eagly and Miller 2016). For example, in the United States, women represent approximately 78% of undergraduates and 71% of graduate students in Psychology (Gruber et al. 2021); nevertheless, Cynkar (2007) reported that only 25% of full professors at graduate departments of Psychology are women, and even more recent estimates still place women below men at this rank, with women accounting for 45.5% of full professors (Casad et al. 2022). In this regard, numerous studies have documented persistent gaps in productivity and scientific impact favoring male researchers (e.g., Barrios et al. 2013; Brown and Goh 2016; D’Amico et al. 2011; González-Álvarez and Sos-Peña 2020; Guyer and Fidell 1973; Mackelprang et al. 2023; Malouff et al. 2010; Mayer and Rathmann 2018).

Notably, Odic and Wojcik (2020), in their analysis of 200,000 publications over a 14-year period across 125 high-impact psychology journals, showed that women publish fewer articles and receive fewer citations than their male counterparts. Similar patterns have been reported in nursing (Shields et al. 2011), political science (Maliniak et al. 2013), and pediatrics (Böhme et al. 2022), where women are underrepresented in productivity, impact, or senior authorship despite constituting the majority of the scientific workforce.

Different frameworks have been proposed to account for these gender disparities in science. For instance, the pipeline theory has been invoked, particularly in STEM disciplines (Cannady et al. 2014), suggesting that current inequalities are largely a legacy of historically low female entry into academic training and research careers, and that disparities will gradually diminish as more gender-balanced cohorts advance through the system (Castleman and Allen 1998; Longman and Madsen 2014; Mariani 2008). In contrast, alternative perspectives such as the leaky pipeline theory argue that women are more likely than men to leave the academic career path at multiple transition points (Blickenstaff 2005), leading to their underrepresentation in senior and leadership positions (Monroe and Chiu 2010), as well as productivity and visibility (Huang et al. 2020). In this regard, research has suggested that these patterns are driven not simply by cohort effects, but by structural barriers and gender bias, including cumulative disadvantages in recruitment, promotion, publication, and access to research funding (Cao et al. 2023; Ceci et al. 2023; Llorens et al. 2021; Roper 2019; van den Besselaar and Sandström 2017).

While several papers have already identified the general bibliometric patterns of female authors across a wide range of scientific disciplines (Abramo et al. 2009; Aguinis et al. 2018; Böhme et al. 2022; Halevi 2019; Holman et al. 2018; Huang et al. 2020; Larivière et al. 2011; Maliniak et al. 2013; Odic and Wojcik 2020; Prpić 2002; Shields et al. 2011; van Arensbergen et al. 2012), research explicitly focusing on interdisciplinary areas remains limited. The expansion of interdisciplinary programs, along with gender and minority participation, have become part and parcel of the social restructuring of contemporary science (Rhoten and Pfirman 2007). In this context, the field of Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) is particularly relevant because it brings together scholars from both female- and male-dominated disciplines. Specifically, it is characterized by great complexity due to its interdisciplinary nature, incorporating models, theories, and findings from diverse disciplines such as Law, Ergonomics, Engineering, Medicine, and Psychology. This study aimed to examine gendered patterns in bibliometric trends related to authorship positions, productivity, scientific impact, and collaboration patterns within the scientific literature on OSH. Specifically, this paper analyzed whether differences exist in these dimensions and explored their evolution across successive five-year cohorts, focusing on work stress intervention research. Work-related stress has long been recognized as a central and representative topic in this discipline, given its strong associations with occupational health outcomes, productivity, absenteeism, and organizational functioning. It has become one of the most studied psychosocial risks internationally (Cassar et al. 2020), and major governmental agencies (e.g., European Commission 2021a; International Labour Organization 2016) identify its prevention and management as a priority area. The topic has been investigated across disciplines that contribute to OSH, including Psychology, Occupational Medicine, Public Health, and Ergonomics, among others. Furthermore, evidence-based reviews (e.g., Kröl et al. 2017; LaMontagne et al. 2007; Richardson and Rothstein 2008; van der Klink et al. 2001) show that work stress intervention research has generated a substantial and cumulative body of empirical studies over several decades. These reviews also identify consistent publication activity in high-impact journals, underscoring the topic’s visibility and relevance within the discipline.

The research questions guiding this study are as follows:

- RQ1: How has women’s participation in first, last, and corresponding authorship positions evolved?

- RQ2: To what extent can the gender differences observed be explained by the composition of cohorts (pipeline effect) versus structural disadvantages (leaky pipeline effect)?

- RQ3: Are there gender differences in research productivity, citation impact, and patterns of collaboration?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

The dataset used to conduct the current study was compiled through a comprehensive and systematic scientific literature review on work stress management interventions (Appendix A). Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al. 2021), an exhaustive search was conducted across five leading abstract and citation databases of peer-reviewed scientific research: ProQuest PsycINFO, EBSCO Education Resources Information (ERIC), EBSCO MEDLINE, Web of Science (WOS), and Scopus. Additionally, reference lists of previous meta-analytic reviews (Kröl et al. 2017; Richardson and Rothstein 2008; van der Klink et al. 2001) were screened for related studies. The literature search was performed using the following keywords connected by Boolean operators: (“work stress” OR “occupational stress” OR “occupational neurosis” OR “employee well-being” OR “occupational health” OR “occupational health psychology” OR “occupational adjustment” OR “job demands” OR “job resources”) AND (“stress management”) AND (intervention OR “workplace intervention” OR prevention OR “program evaluation” OR evaluation OR “organizational effectiveness” OR “health promotion”). The search was limited to articles published after 1976 (Appendix B) in peer-reviewed journals, written in English or Spanish, and focused on the adult population.

In order to gather data from relevant primary studies on stress management at work, the following inclusion criteria were established:

- The study evaluates the effects of work-related stress management interventions.

- The sample includes participants from the working population, employed within an organization, without a known diagnosis or treatment for chronic illnesses or physical and/or psychological problems (e.g., hypertension or depression), and who are not on sick leave.

- The study has an experimental or quasi-experimental design, including comparisons between the intervention and at least one control group without intervention (e.g., waitlist, treatment as usual) or another intervention group.

- The study reports information about the intervention (e.g., contents, duration, and results).

- The study has been published after 1976.

- The study has been written in English or Spanish.

On the other hand, study eligibility was assessed using the following exclusion criteria:

- The study has not been published in peer-reviewed journals (e.g., dissertations, book chapters).

- The study is not empirical research (e.g., reviews, meta-analysis).

- The study does not include outcome variables related to psychosocial health and well-being (e.g., economic outcomes).

- The data are gathered entirely through qualitative measures.

- The study focuses on tertiary interventions rather than primary or secondary interventions.

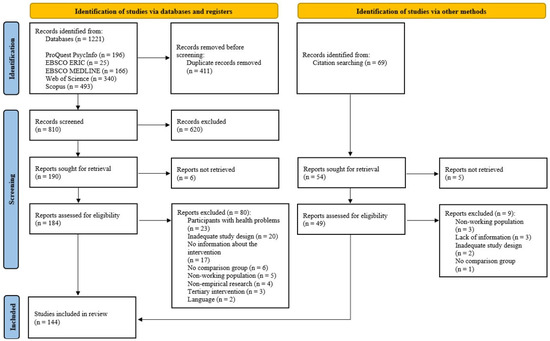

As summarized in Figure 1, a total of 1290 potentially relevant works were retrieved from the databases and reference lists of previous meta-analytic studies. In the first step, 411 duplicate records were eliminated using Zotero 6.0 for Windows, a reference management software. Next, titles and abstracts of 810 publications were screened to determine whether the full text of the studies should be reviewed in detail. After this screening, 620 records were excluded for not meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The full texts of 244 reports were then sought for retrieval and further screening. Ultimately, 144 studies were included in the review, covering nearly 50 years of research in the field of OSH (the complete list of studies is available upon request from the corresponding author). To identify evolving trends in this period, these studies were classified by the 5-year intervals in which they were published, aligning with the typical duration of graduate training programs (Cascio and Aguinis 2008; Filardo et al. 2016).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the decision process of searching and eligibility of studies in the review. Note: Adapted from Page et al. (2021).

2.2. Sample

The final sample consisted of 144 articles included in the literature review, signed by 672 author entries corresponding to 570 unique authors. To address the problem of author name disambiguation (Gurney et al. 2012; Smalheiser and Torvik 2009; Strotmann and Zhao 2012), each author was identified by their first and last name through the manual inspection of full bibliographic records. This involved examining full-text articles and cross-referencing with other sources, such as academic or personal webpages. This method is the most accurate for matching bibliographic records with individual researchers and mitigating issues related to author name ambiguities (Milojević 2013).

2.3. Variables

2.3.1. Gender

In accordance with previous research (e.g., Cislak et al. 2018; González-Álvarez and Sos-Peña 2020; Mackelprang et al. 2023; Thelwall 2020), each author was classified as either female or male (Appendix C) based on strongly gendered first names and publicly available information (e.g., descriptions and pronouns on professional or private websites, or other online records). When gender could not be determined through these methods, it was inferred using Gender API (https://gender-api.com/), an online service that assigns a gender probability based on the author’s name and country. Specifically, “Gender API includes approximately 815,000 unique first names from 189 countries and assigns labels based on a combination of the sex assigned at birth and genders detected in social media profiles” (Fulvio et al. 2021, p. 4). This gender assignment strategy has been successfully employed in other bibliometric studies (Abramo et al. 2022; Dworkin et al. 2020; Fulvio et al. 2021; Thelwall 2020). In the present sample, the names of 42 authors (7.4%) was submitted to Gender API, which provided a probability greater than 0.70 for their gender, in line with the criteria used by Dworkin et al. (2020) and Fulvio et al. (2021). Additionally, to evaluate the suitability of Gender API for the current dataset, we validated the algorithm’s inference against manual coding using 100 randomly selected cases. Gender API correctly classified 97% of manually coded names (K = 0.94) with an average accuracy of 96.5%, almost 30 percentage points above the threshold commonly applied in previous studies (Dworkin et al. 2020; Fulvio et al. 2021).

2.3.2. Bibliometric Indicators

For the purposes of this study, the subjects of the analysis occupied first, corresponding, and last authorship positions, as these positions are widely considered the most prestigious (Ayyala and Trout 2022; Fox et al. 2018; González-Álvarez and Cervera-Crespo 2019; Odic and Wojcik 2020; Pagel et al. 2019; West et al. 2013). Specifically, first authorship is typically associated with the researcher who led the study and contributed most substantially to the manuscript (Fox et al. 2018). Corresponding author denotes the individual responsible for managing the submission process, communicating with the journal, and responding to inquiries (Pagel et al. 2019). Last authorship is commonly reserved for the senior researcher or principal investigator who oversaw the project and provided strategic guidance, thereby representing leadership and supervisory responsibility (Baerlocher et al. 2007). These authorship positions can influence the credit researchers receive for their contributions and are crucial for hiring, promotion, and tenure decisions in scientific fields (Fox et al. 2018; Wren et al. 2007).

The proportion of female authorship (FAP) was determined using Bendels et al.’s (2018) formula, as follows:

where FemaleN is the number of female authorship positions and MaleN is the number of male authorship positions. The same procedure was performed to calculate the proportion of male authorship (MAP). The proportions are presented as percentages in the text for better readability.

The authorship-specific odds ratios for female authorship compared to male authorship were also calculated (female authorship odds ratio; FAOR; Bendels et al. 2017, 2018), including the corresponding confidence intervals (CIs) at a confidence level of 95%. For instance, the formula used for the first authorship was as follows:

where FemaleNF and MaleNF are the number of female and male first authorship positions; FemaleNCo and MaleNCo are the number of female and male co-authorship positions; and FemaleNL and MaleNL are the number of female and male last authorship positions. The FAOR for corresponding and last authorship positions was calculated equivalently. A FAOR greater than 1 indicates higher female than male odds for the authorship analyzed. In line with other bibliometric works (Bendels et al. 2018; Böhme et al. 2022), single authorship was considered first authorship, and the authorship of articles with two authors was counted as first and last authorship. Therefore, the FAOR for first authorship was computed by considering all articles, whereas the FAORs for last authorship were determined by considering all articles with at least two signatures.

As an indicator of research productivity, the number of publications was counted (Agarwal et al. 2016). In this study, all publications were articles published in peer-reviewed journals. Furthermore, the number of citations for each article was measured to assess scientific impact. Following previous works (e.g., Chan et al. 2013; Martín-Martín et al. 2018; Mukherjee 2009), citations were extracted from Google Scholar. Although the articles were identified from various databases, which showed some overlap and differences in citation counts, Google Scholar was used as a common source due to its comprehensive coverage of citations across journals and other sources (Martín-Martín et al. 2017; Meho and Yang 2007). Since citation counts evolve over time and older articles are generally cited more frequently than newer ones (Thelwall 2020), raw citation counts were adjusted. Following the normalized citation procedure introduced by Chan et al. (2013), an age-adjusted citation measure was calculated to mitigate the impact of the papers’ age. For example, if an article published in 2013 has 50 citations in 2023, its normalized citation count would be 5.00 (50 citations divided by 10 years). Lastly, to analyze collaborative contributions, participation, presence, and contribution bibliometric indicators were computed to process publications produced by cooperation among authors of different genders. These metrics include the number of publications with at least one author of a given gender, as well as the total count and proportion of authors of a given gender in each publication’s author team, respectively (Cislak et al. 2018; Kretschmer et al. 2012; Naldi et al. 2004).

2.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, percentages, and measures of central tendency and dispersion, were computed for the variables under study. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk goodness-of-fit tests indicated that none of the variables studied met the assumptions of normal distribution (D = 0.12–0.54, p < 0.001; W = 0.25–0.54, p < 0.001). Consequently, non-parametric tests were employed. Specifically, the Chi-squared test, the Mann–Whitney U test, and the Kruskal–Wallis test were used to assess the gender differences in bibliometric indicators. Effect sizes were calculated using the Phi coefficient (ϕ) for the Chi-squared test and Cohen’s r for the Mann–Whitney U test, with values of 0.10 indicating a small effect, 0.30 a medium effect, and 0.50 a large effect for both statistics (Cohen 1988; Fritz et al. 2012). For the Kruskal–Wallis test, Cohen’s f was used to report the effect size (small: 0.10; medium: 0.25; large: 0.40; Cohen 1988). Furthermore, as in other bibliometric studies examining authorship trends (e.g., Brinker et al. 2018; Khan et al. 2018), the Cochran linear trend test was employed to examine gender trends over time. All contrasts were conducted using two-tailed tests, and the significance level was set at p < 0.05 for all tests. Data analyses were performed using SPSS 29.0 for Windows.

3. Results

A total of 144 articles published during the years 1977–2023 were included in the literature review from the ProQuest PsycINFO, EBSCO Education Resources Information (ERIC), EBSCO MEDLINE, Web of Science (WOS), and Scopus databases. The articles were authored by 672 researchers, averaging 4.67 authorship positions per publication. At the global level, female authorship was significantly overrepresented with a FAP of 54.2%, while 45.8% of the authorship was attributed to men, χ2(1) = 4.67, p = 0.03, ϕ = 0.08.

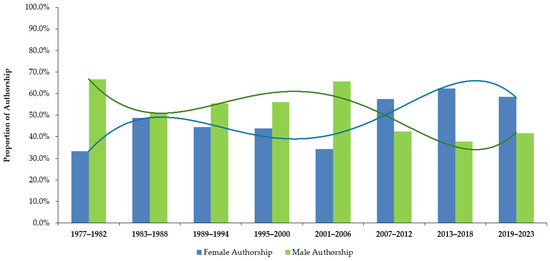

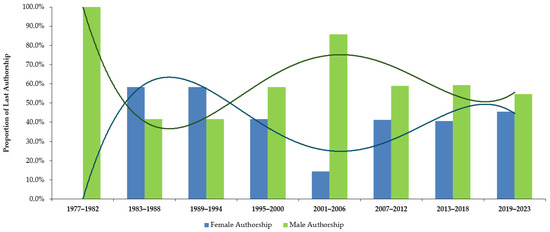

As shown in Figure 2, authorship patterns have evolved markedly across cohorts. Traditionally, the proportion of male authorship consistently exceeded the number of female authorship positions in published works. However, this trend has shifted, especially in recent years. This change is evident, as the FAP increased from 33.3% in 1977–1982 to 58.5% in the years 2019–2023, reaching the highest point during 2013–2018, at 62.3%. Notably, female authorship from just the last two decades accounts for 56.6% of all recorded signatures. In contrast, male authorship followed an opposite trajectory, declining by 37.8% from 66.7% in 1977–1982 to 41.5% in 2019–2023. The highest proportion of male authorship was observed in 1977–1982 (66.7%), followed by 2001–2006 (65.6%), which marked the turning point when the trends began to reverse (Cochrane linear trend, p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Time trend in the proportion of authorship positions. Note. The blue line represents the polynomial trend for female authorship (R2 = 0.88), while the green line represents the trend for male authorship (R2 = 0.88).

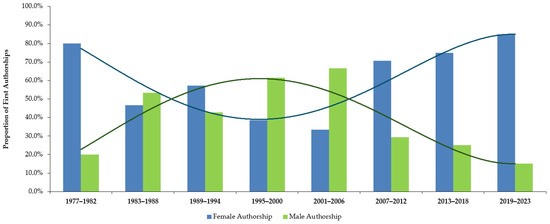

These general authorship patterns vary substantially depending on the authorship position. In the case of first authorship, there is a clear gender gap favoring women, who occupy 64.6% of first positions compared to men with a MAP of 35.4% [χ2(1) = 12.25, p < 0.001, ϕ = 0.29]. The FAOR was 1.73 (95% CI = 1.18–2.53) for first authorship, revealing that women have almost 2-fold higher odds of occupying the first position than men. From a longitudinal perspective (see Figure 3 and Table 1), the proportion of female first authorship follows a U-shaped trend. Earlier years of scientific production were more closely associated with female authorship, with a FAP of 88.0% in 1977–1982 (FAOR = 45.00, 95% CI = 1.49–1358.27), though there was no clear dominance over male authorship for the next years. Between 1995–2000 (MAP = 61.6%) and 2001–2006 (MAP = 66.7%), men represented the majority of first authorship positions, whereas women’s odds of being first author were lower (FAOR = 0.72, 95% CI = 0.19–2.76; FAOR = 0.94, 95% CI = 0.27–3.20, respectively). However, from 2007 onwards, female participation increased again, reaching 84.8% in 2019–2023, compared with only 15.2% for men (Cochrane linear trend, p = 0.002), with the FAOR ranging from 2.08 (95% CI = 0.65–6.69) to 4.74 (95% CI = 1.76–12.75).

Figure 3.

Time trend in the proportion of first authorship positions. Note. The blue line represents the polynomial trend for female authorship (R2 = 0.79), while the green line represents the trend for male authorship (R2 = 0.79).

Table 1.

Time trend in the female authorship odds ratio.

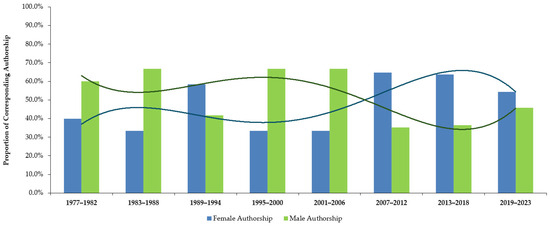

Regarding corresponding authorship, no significant gender differences were observed. Women accounted for 51.8% of corresponding authorship positions, whereas men held 48.2% [χ2(1) = 0.18, p = 0.67, ϕ = 0.04]. In this case, the FAOR was 0.90 (95% CI = 0.62–1.31), suggesting odds close to gender parity, but tilted toward men. As depicted in Figure 4, male corresponding authorship dominated until 2001–2006 (58.5%), in contrast to 41.5% for women. Cohort-specific FAORs in Table 1 align with this pattern. Except for 1977–1982 and 1989–1994, men generally had higher odds of serving as corresponding author. Similar to the pattern observed for first authorship, this trend reversed in later years, with women representing a higher proportion of corresponding authorship positions during 2007–2012 (FAP = 64.7%; MAP = 35.3%), 2013–2018 (FAP = 63.6%; MAP = 36.4%). Nevertheless, in the most recent period (2019–2023), women’s odds dipped slightly below parity (FAOR = 0.82, 95% CI = 0.39–1.69), despite a majority share by count (FAP = 54.3%; MAP = 45.7%). The Cochrane linear trend test did not reveal a statistically significant change over time (p = 0.08).

Figure 4.

Time trend in the proportion of corresponding authorship positions. Note. The blue line represents the polynomial trend for female authorship (R2 = 0.52), while the green line represents the trend for male authorship (R2 = 0.52).

The gender gap is more pronounced for last authorship, favoring men. The proportion of male last authorship was significantly higher than female last authorship, with 58.5% versus 41.5%, respectively [χ2(1) = 3.92, p = 0.04, ϕ = 0.17]. The FAOR was 0.54 (95% CI = 0.37–0.79), indicating that men have almost 2-fold higher odds of occupying the last position. The patterns of last authorship over the years were reversed compared to those observed for first signatures (see Figure 5); across most cohorts, publications with male last authorship outnumber those with female last authorship, yielding lower odds for women (see Table 1). Women seemed to occupy the last position on papers more frequently than men only during 1983–1988 and 1989–1994 (FAP = 58.3%; MAP = 41.67%), with FAOR of 1.96 (95% CI = 0.45–7.99) and 2.55 (95% CI = 0.65–9.95), respectively. Nevertheless, the share of male last authorship predominated in all other periods, reaching the largest difference in 1977–1982 (Δ%MAP-%FAP = 100.0%) and ranging from 9.1% (2019–2023) to 71.4% (2001–2006) throughout the rest of the timeline. Despite a slight narrowing of this gap in recent years, the change over time was not statistically significant (Cochran linear trend, p = 0.80).

Figure 5.

Time trend in the proportion of last authorship positions. Note. The blue line represents the polynomial trend for female authorship (R2 = 0.91), while the green line represents the trend for male authorship (R2 = 0.91).

The analysis of unique authorship entering each cohort provides valuable insight into whether gender differences in authorship positions are due to composition (pipeline effect) or to structural barriers (leaky pipeline effect). Overall, female newcomers are over-represented, with a FAP of 54.5% [χ2(1) = 4.72, p = 0.03, ϕ = 0.09]. FAORs are 1.62 (95% CI = 1.08–2.41) for first authorship, 0.80 (95% CI = 0.53–1.20) for corresponding authorship, and 0.57 (95% CI = 0.37–0.86) for last authorship. As shown in Table 2, the proportion of female entrants increased markedly over time, from only 22.2% in 1977–1982 to 58.1% in 2019–2023 (Cochran linear trend, p < 0.001). The FAOR for first authorship among new entrants exceeded 1 in most periods, reaching 4.05 (95% CI = 1.47–11.12) in the most recent cohort, which indicates that women were over four times more likely than men to occupy a first authorship position when entering the publication system. However, these gains at entry do not fully translate into senior authorship positions. Despite women representing the majority of newcomers since 2007, with a FAP higher than 58.0%, their odds of occupying corresponding or last authorship positions remained below parity (FAOR < 1) across most cohorts. This pattern closely mirrors the trends observed when considering all authorship positions (see Table 1), suggesting that women do not consistently advance into roles associated with coordination and leadership responsibility. Taken together, these findings suggest the existence of a leaky pipeline dynamic. Women predominate in the field, increasingly enter the publication system, and frequently lead studies as first authors, yet their progression toward senior authorship positions remains constrained.

Table 2.

Time trend of unique authorship positions at the entry of each cohort.

Regarding scientific productivity, the 364 female authorship positions corresponded to 310 (54.5%) different authors, yielding a mean productivity of 1.17 articles per author (SD = 0.62; Mdn = 1.00; Range = 5). In contrast, the 308 male authorship positions corresponded to 259 (45.5%) individuals, resulting in an average of 1.18 articles per author (SD = 0.70, Mdn = 1.00; Range = 6). While the number of female authors was significantly higher than that of male authors [χ2(1) = 4.39, p = 0.04, ϕ = 0.09], the gender difference in productivity was not significant, U = 40068.50, z = −0.22, p = 0.82, r = 0.009.

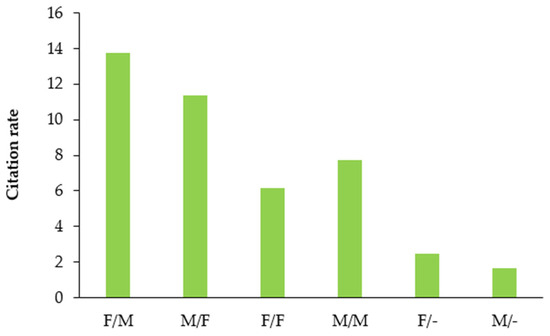

In terms of scientific impact, the articles in this study received on average 9.44 citations per article (SD = 19.32, Mdn = 4.88; Range = 162.80). Papers with male last authorship attained the highest citation rates of 11.35 citations per article (SD = 23.46; Mdn = 5.31; Range = 162.80), followed by articles with female first authorship, 9.69 citations per article (SD = 21.53; Mdn = 4.62; Range = 162.80). Publications with male first authorship and female last authorship were the least cited, accounting for 8.97 (SD = 14.71; Mdn = 5.54; Range = 95.20) and 7.91 cites per article (SD = 13.31; Mdn = 4.96; Range = 94.8), respectively. There were no significant differences in citation rates between female and male-authored groups, H(3) = 1.08, p = 0.78, f = 0.00. Additionally, citation rates by gender–position combinations (Böhme et al. 2022) were examined (see Figure 6). Papers signed by a women as first author and a man as last author were the most cited on average, 13.72 citation per article (SD = 29.18; Mdn = 5.00; Range = 162.80), followed by publications with male first authorship and female last authorship (M = 11.36; SD = 5.33; Mdn = 21.17; Range = 94.17) In contrast, single-authored articles were the least cited. The Kruskal–Wallis test revealed no significant differences across these combinations, H(5) = 7.68, p = 0.18, f = 0.14.

Figure 6.

Gender-specificity of citations. Note. F/M = Female first authorship/Male last authorship; M/F = Male first authorship/Female last authorship; F/F = Female first authorship/Female last authorship; M/M = Male first authorship/Male last authorship; F/- = Female first authorship (single-authored); M/- = Male first authorship (single-authored).

Finally, in order to address gender differences in the authors’ teams of publications, bibliometric indicators of participation, presence, and contribution (Naldi et al. 2004) were assessed. First, participation counts the number of publications with at least one author of a given gender. Of the 135 multi-authored articles in the dataset, 90.4% had at least one female author, while 87.4% had at least one male author. The Chi-squared test revealed no significant differences between women’s and men’s participation, χ2(1) = 0.07, p = 0.79, ϕ = 0.05. Second, presence counts the number of authors of a given gender in each publication. Female authors constituted 53.7% of the total authorship, but this was not significantly higher than the presence of male authors, who made up 46.3%, χ2(1) = 3.62, p = 0.06, ϕ = 0.07. And, lastly, contribution measures the involvement of each gender in the production of a publication, assuming equal contribution from all authors. Women’s contribution amounted to an average of 51.9% of the overall research production, which is almost equal to their presence. A Mann–Whitney U test showed no statistically significant difference in contribution between female (M = 0.52, SD = 0.29, Mdn = 0.50, Range = 1.00) and male authors (M = 0.48, SD = 0.29, Mdn = 0.50, Range = 1.00), U = 8516.50, z = −0.94, p = 0.35, r = 0.05.

4. Discussion

The main objective of the current research was to examine gender differences in bibliometric trends within the field of OSH. Specifically, this study investigated a sample of 144 peer-reviewed empirical studies focused explicitly on work stress interventions over a 47-year period, authored by people occupying 672 authorship positions. Overall, the findings reveal significant gender differences. Consistent with recent bibliometric studies (González-Álvarez and Sos-Peña 2020; González-Sala et al. 2021; Sánchez-Jiménez et al. 2024; West et al. 2013), the data indicated a growing representation of women in academic publications, particularly in recent years. The proportion of female authorship positions was significantly higher than that of male authorship positions, accounting for 54.2% versus 45.8%, respectively. The difference in the number of individual authors was also significant, with female authors representing 54.5% and male authors 45.5%. Temporal analyses reveal a clear upward trend in female authorship and a corresponding decline in male authorship from 1977 to 2023, underscoring significant shifts in the academic landscape, with women significantly outnumbering men. Although previous research has reported an underrepresentation of female authorship and/or authors in science (Abramo et al. 2009; González-Álvarez and Cervera-Crespo 2019; González-Álvarez and Sos-Peña 2020; Holman et al. 2018; Huang et al. 2020; Larivière et al. 2013; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Institute for Statistics 2021; West et al. 2013), these findings are congruent with the gender distribution observed in specific disciplines and subdisciplines, such as health services research, education, and the social sciences, as well as developmental and educational psychology (Böhme et al. 2022; González-Álvarez and Cervera-Crespo 2019; González-Sala et al. 2021; Holman et al. 2018; Odic and Wojcik 2020).

Special attention was given to the order and position of the authorship (RQ1), as first, corresponding, and last authorship positions are often viewed as the most prestigious positions in a paper and are highly relevant to academic advancement (Ayyala and Trout 2022; Odic and Wojcik 2020; Thelwall 2020; West et al. 2013). Regarding first authorship, the proportion of female authorship (64.6%) was significantly higher than that of male authorship (35.4%), highlighting the growing number of publications led by women over the last decade. These results might seem unusual given the male domination in academia and the prestigious positions they occupy on papers (Larivière et al. 2013; West et al. 2013). However, the observed FAORs were comparable to those reported in other studies (e.g., Bendels et al. 2017, 2018; Böhme et al. 2022). Furthermore, these findings support past bibliometric research showing that, while women have historically been underrepresented as first authors, this trend has been changing recently, with some disciplines even showing an overrepresentation of female first authors (for a detailed description, see González-Álvarez and Cervera-Crespo 2019; González-Álvarez and Sos-Peña 2020; Holman et al. 2018; Kretschmer et al. 2012; Odic and Wojcik 2020; Thelwall 2020; West et al. 2013).

In contrast, the analysis of corresponding authorship revealed a different pattern. In this case, no significant gender differences were observed. The temporal dynamics showed fluctuations across cohorts. Male corresponding authorship predominated until 2001–2006, after which the pattern reversed, without significant changes in trends over time (Ayyala and Trout 2022). These fluctuations may be explained by the nature of the corresponding author role, which typically involves responsibility for manuscript submission, revisions, and publication logistics (Pagel et al. 2019). This position is often occupied by the first author, with the last author being the next most common corresponding author (Baerlocher et al. 2007)—roles that, in this study, were predominantly held by women and men, respectively. Although women accounted for a slightly higher share of corresponding authorship overall, men continued to have greater odds of occupying this position, particularly in the most recent cohort (2019–2023; FAOR = 0.82). In this regard, similar gender disparities in corresponding authorship have also been reported in previous studies (e.g., Fox et al. 2018; Pagel et al. 2019; Shah et al. 2021), which found that women remain less frequently designated as corresponding authors, despite their growing presence in academic publishing.

The gender gap widens notably in the last authorship position. Here, 58.5% of authorship positions were held by men, while female last authorship positions were significantly fewer, a trend that persisted since the 1995–2000 period. Although there has been an increase in female last authorship over time, the slow pace of change and the lack of statistical significance in the overall trend suggest that achieving gender equity in senior authorship remains a challenging goal. Indeed, across most cohorts, women had lower odds of occupying the last position, with FAORs consistently below 1, in line with values reported by Bendels et al. (2017; FAOR = 0.57), Bendels et al. (2018; FAOR = 0.47), and Böhme et al. (2022; FAOR = 0.63). This finding is consistent with previous studies in overall science and specific fields such as STEM, Psychology, and Medicine (Brück 2023; González-Álvarez and Cervera-Crespo 2019; González-Álvarez and Sos-Peña 2020; Holman et al. 2018; Odic and Wojcik 2020; West et al. 2013), which have shown a pronounced gender gap in last authorship, with women being underrepresented.

These analyses were complemented by the examination of unique authorship entering each cohort to explore whether the observed gender differences were related to a pipeline effect or a leaky pipeline dynamic (RQ2). Overall, the number of women entering the field has steadily increased over time, reflecting both a higher proportion and greater likelihood of women occupying first authorship positions compared to men. By contrast, this pattern was not observed for corresponding and last authorship positions. These results suggest that, although women increasingly enter the publication system, fewer do so in positions associated with seniority or leadership. In most medical and social sciences, first authors are typically associated with early-career researchers who contribute most significantly to the article, while last authors are generally more senior (Ceci et al. 2023; Wren et al. 2007). This pattern suggests that women are more likely to be early-career researchers, whereas men are more likely to occupy senior positions. Other studies (González-Álvarez and Cervera-Crespo 2019; Larivière et al. 2013) indicate that age may play a major role in these gender patterns, reflecting the influx of new female researchers into OSH who publish their initial studies under the guidance of senior researchers. This trend is similar to other fields, such as Psychology, where most of today’s eminent psychologists began their careers several decades ago, when fewer women pursued the discipline. Notwithstanding the growing participation and overrepresentation of women in entry-level authorship positions, men continue to have higher odds of occupying senior and leadership positions, suggesting that women’s advancement to these roles remains limited, consistent with the leaky pipeline theory (Blickenstaff 2005; Monroe and Chiu 2010). Similar trends have been observed in other disciplines, such as Psychology (Eagly and Miller 2016) and Pediatrics (Böhme et al. 2022), in which women are over-represented at early-career stages, but their proportion declines along the academic ladder and only a few reach senior leadership positions. It is important to note that in the academic system, promotion from assistant to associate professor may require 5–7 years, and an additional 5–7 years may be needed to reach full professorship, resulting in a total trajectory of approximately 10–15 years (Papaconstantinou and Laimore 2006). Taking these timelines into account, researchers entering the earliest cohorts (e.g., 1983–1988) would be expected to reach senior positions and appear more prominently in last authorship roles 10–15 years later (e.g., 1995–2000), similarly for more recent cohorts. However, this expected progression is not reflected in the authorship patterns observed, indicating the persistent underrepresentation of women at senior levels. A concerning issue here is the potential gender bias and discrimination underlying this gap, which may cause women to exit the field or produce research at a slower rate as they advance to more prestigious roles (Cao et al. 2023; Ceci et al. 2023; Llorens et al. 2021; Roper 2019; van den Besselaar and Sandström 2017). This perpetuates that male “star” researchers outperform female “star” scientists (Aguinis et al. 2018) and that women receive less prominence and recognition at senior levels compared to men (Eagly and Miller 2016).

Regarding RQ3, no significant gender difference in productivity was found, suggesting a gender balance in terms of scientific production within the field of OHS. This finding is surprising, as numerous studies on gender disparities in science and research have typically shown a productivity gap in favor of men (e.g., Abramo et al. 2009; Aguinis et al. 2018; Astegiano et al. 2019; Böhme et al. 2022; Cole and Zuckerman 1984; D’Amico et al. 2011; González-Álvarez and Sos-Peña 2020; Guyer and Fidell 1973; Huang et al. 2020; König et al. 2015; Larivière et al. 2011; Mackelprang et al. 2023; Malouff et al. 2010; Mayer and Rathmann 2018; Odic and Wojcik 2020; Prpić 2002; van Arensbergen et al. 2012; Xie and Shauman 1998). The authorship type could help explain these results. Although women accounted for most single-authored papers (88.9%), the publications analyzed were predominantly multi-authored (93.8%). This strong prevalence of team-based research, coupled with the broader decline in single-authored papers (Larivière et al. 2015; Wuchty et al. 2007) may reduce observable differences in individual productivity, as publication output is shared across team members rather than reflecting solely the productivity of a single author. On the other hand, the observed balance in productivity within OSH could also be attributed to the field’s interdisciplinary nature. OSH encompasses knowledge and researchers from diverse disciplines, each of which may have different gender-related productivity patterns. For example, scientific activity in engineering and technology is often more male-dominant (Huang et al. 2020), whereas disciplines like nursing or social sciences tend to have a more balanced gender representation (Holman et al. 2018). Additionally, work preferences and career behaviors might play a role. Research suggests that women in earlier career stages may engage in more cross-disciplinary “knowledge producing” relationships than their male peers, as well as migrate toward new interdisciplinary fields rather than established disciplines to avoid the hierarchical structure and competitive nature of traditional science (Rhoten and Pfirman 2007). These factors may contribute to the observed gender balance in productivity within the field of OSH.

Interestingly, the analysis of citation counts (RQ3) for each publication revealed no significant differences based on the gender of the first and last authors. This finding contrasts with the traditional trend where publications by male authors are cited more frequently than those by female authors (e.g., Eagly and Miller 2016; González-Álvarez and Cervera-Crespo 2019; König et al. 2015; Larivière et al. 2011, 2013; Lerman et al. 2022; Odic and Wojcik 2020; Rajkó et al. 2023). Nevertheless, the data from this research suggest a balance and equal recognition of scientific contributions between women and men, in line with other studies (e.g., Barrios et al. 2013; Haslam et al. 2008; Lönnqvist 2022; Peñas and Willett 2006; Thelwall 2020). This seemingly contradictory result may indicate a shift in publication impact patterns related to gender, at least within the field of OSH. In this regard, van Arensbergen et al. (2012) examined gender differences in citation counts across two generations of scientists: established researchers (associate or full professors) and young researchers (Ph.D. graduates within the last 3 years). They found that while men in the older generation received more citations than women, this difference was not observed among younger scientists, suggesting that traditional disparities may be diminishing over time.

Regarding gender differences in the authors’ teams (RQ3), female and male authors are rather equally distributed in cooperative research. Specifically, women contributed to 90.4% of all multi-authored articles, while men contributed to 87.4%. In terms of presence, women constituted 53.7% of the total authors, which closely aligns with their contribution of 51.9%; that is, more than one in two authors of each co-authored publication are women. These results highlight a balanced gender distribution within co-authorship teams and contrast with findings from other studies in scientific and technological disciplines (e.g., Kretschmer and Aguillo 2004; Naldi et al. 2004; West et al. 2013), which have reported that women are less likely to be involved with collaborative research projects leading to publications. However, as noted by Larivière et al. (2013), the gender gaps vary between fields and subfields. Indeed, the participation of women in this study is comparable to findings from a bibliometric analysis of gender studies journals, where women’s participation reached 91.6%, with high rates in both presence (85.6%) and contribution (87.5%). This suggests that gender differences in cooperation patterns may be related to the subject matter of the research (Kretschmer et al. 2012).

4.1. Limitations and Future Research

This study, like all research, has some limitations that need to be addressed. First, in this initial attempt to examine gender differences in bibliometric trends within the interdisciplinary field of OSH, the study focused primarily on work stress management, a central and representative topic in this discipline (Cassar et al. 2020; Kröl et al. 2017; Richardson and Rothstein 2008; van der Klink et al. 2001). However, other important research topics within this field, such as burnout, mobbing, workplace violence, or ergonomic risks, were not addressed. Future studies should explore these areas for a more holistic and comprehensive view. Second, Gender API was employed to assign gender to those authors whose gender could not be determined from public sources (e.g., descriptions and pronouns on professional or private websites, or other online records). Although this tool has been widely used in bibliometric research (Abramo et al. 2022; Dworkin et al. 2020; Fulvio et al. 2021; Thelwall 2020) and has provided good levels of accuracy in the sample under study, name-based algorithms can produce errors (Sebo 2021), as names may be unisex or culturally ambiguous. Future studies might therefore consider validating the gender detection tool on the specific sample to determine its classification error rate. Third, while this study effectively identified gender differences in bibliometric trends, it did not explore the underlying causes of these gender gaps. In this sense, a successive five-year cohort approach (Cascio and Aguinis 2008; Filardo et al. 2016) was employed to examine evolving patterns and track authors’ entry in the field. However, this study did not capture individual-level information on critical exit points or on factors that may disrupt researchers’ productivity, particularly those with a significant gender burden (e.g., career interruptions linked to maternity or caregiving responsibilities). Understanding these reasons is crucial for a better grasp of gender dynamics in research and for developing targeted interventions to promote gender equality in OSH and science more broadly. Further research should therefore incorporate methods to assess researchers’ experiences, challenges, and perceptions, for example, combining scientometric data with surveys (König et al. 2015). Furthermore, the scope of this study was restricted to quantitative intervention designs, following the standards established in the core evidence-based reviews of work-related stress interventions (Kröl et al. 2017; LaMontagne et al. 2007; van der Klink et al. 2001; Richardson and Rothstein 2008). Future research should therefore examine whether gender patterns emerge across different methodological traditions, particularly qualitative approaches. Lastly, scientific impact was measured using citation counts, a common metric in bibliometric research (Agarwal et al. 2016). While widely employed, a high citation count does not always indicate positive recognition; some citations may be critical or negative (Xu et al. 2022). Thus, new works should consider employing additional impact indicators, such as societal impact measures for scientific papers (Bornmann and Haunschild 2019), in order to provide a more comprehensive assessment of research publications.

4.2. Implications

The results of the present study offer valuable insights for bibliometric research. Specifically, they enhance our understanding of the integration of female scientists within the field of OSH, shedding light on gender dynamics in the interdisciplinary area, which has been underexplored due to its complexity involving theories, methods, and researchers from multiple disciplines (Thelwall et al. 2023). Additionally, the findings provide further support for the leaky pipeline framework (Blickenstaff 2005; Cao et al. 2023; van den Besselaar and Sandström 2017), which posits that gender inequalities are not merely a matter of lower female entry into research careers, but persist throughout the academic ladder stages due to structural barriers and gender bias. The present study revealed a women’s underrepresentation in senior and supervisory positions within work stress intervention research, despite an overrepresentation of female authorship and the growing number of women entering the field.

This research also has practical implications. Overall, the results indicated an increase in women’s representation and positive trends toward gender equality in scientific publications and impact within the field. However, this progress contrasts with the underrepresentation of women in prestigious positions, such as Fellows in key scientific organizations like the International Association of Applied Psychology (IAAP) and the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology (SIOP), which are prominent in occupational health. Despite recent advancements, barriers to recognition and leadership for women in science still exist. These findings reinforce the need for continued efforts to address gender bias and promote equitable opportunities in academia, including areas such as hiring, tenure, promotions, funding, and recognition (Llorens et al. 2021).

5. Conclusions

This study contributes to a deeper comprehension of gender differences in bibliometric patterns within the interdisciplinary field of OSH. It highlights an upward trend in women’s scientific activity on psychosocial risks at work, particularly work-related stress management. Certainly, significant progress has been made in recent years, solidifying the presence of female authors in this field, yet there is still considerable room for improvement. To fully capitalize on women’s potential and contributions to research, ongoing efforts are needed to reduce inequality and foster a more equitable and inclusive scientific environment. Academic institutions and publishers should consider implementing policies that support diverse authorship and ensure equitable opportunities for all researchers. This includes enacting specific actions to guarantee equal representation of women in academia (Forman-Rabinovici et al. 2024; Galán-Muros et al. 2023) and developing targeted initiatives that actively support and promote their contributions to scientific research (e.g., Llorens et al. 2021).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.D.-C. and C.M.; methodology, C.D.-C. and C.M.; investigation, C.D.-C. and C.M.; data curation, C.D.-C. and C.M.; formal analysis, C.D.-C. and C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.D.-C.; writing—review and editing, C.D.-C. and C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Partial financial support for this research was provided by the Instituto de Seguridade e Saúde Laboral de Galicia (ISSGA), part of the Xunta de Galicia, Spain, and by the Spanish Government’s Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities (MICIU) through the grants for University Teaching Staff Training (Ayudas para la Formación del Profesorado Universitario FPU), grant number FPU22/01518 (to CD-C).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| STEM | Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics |

| OSH | Occupational Safety and Health |

| FAP | Female Authorship Proportion |

| MAP | Male Authorship Proportion |

| FAOR | Female Authorship Odds Ratio |

Appendix A

The literature review is part of a broader project aimed at analyzing the effectiveness of stress management intervention programs in improving employees’ psychological health. A study protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (registration number CRD42023470964). Although the same search protocol is used, the current work offers original and independent bibliometric information and data aligned with the objective of the study.

Appendix B

In 1976, the American Psychological Association (APA) Task Force on Psychological Health Research published a report urging psychologists, including industrial/organizational psychologists, to play a role in addressing the psychological health problems of the American population (Beehr and Newman 1978).

Appendix C

Although the authors of this article recognize that gender is not a binary variable (American Psychological Association 2015), it was operationalized into female and male categories, consistent with the procedure of previous gender bibliometric research.

References

- Abramo, Giovanni, Ciriaco Andrea D’Angelo, and Alessandro Caprasecca. 2009. Gender differences in research productivity: A bibliometric analysis of the Italian academic system. Scientometrics 79: 517–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramo, Giovanni, Ciriaco Andrea D’Angelo, and Ilenia Mele. 2022. Impact of COVID-19 on research output by gender across countries. Scientometrics 127: 6811–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, Ashok, Durairajanayagam Durairajanayagam, Suresh Tatagari, Sandro Esteves, Avi Harlev, Ralf Henkel, Sudip Roychoudhury, Sheryl Homa, Nicolás Puchalt, Ranjith Ramasamy, and et al. 2016. Bibliometrics: Tracking research impact by selecting the appropriate metrics. Asian Journal of Andrology 18: 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguinis, Herman, Yoon Hee Ji, and Hyeon Joo. 2018. Gender productivity gap among star performers in STEM and other scientific fields. Journal of Applied Psychology 103: 1283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. 2015. Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. American Psychologist 70: 832–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astegiano, Julia, Enrique Sebastián-González, and Carolina de Toledo Castanho. 2019. Unravelling the gender productivity gap in science: A meta-analytical review. Royal Society Open Science 6: 181566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyala, Rama S., and Andrew T. Trout. 2022. Gender trends in authorship of Pediatric Radiology publications and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatric Radiology 52: 868–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baerlocher, Mark Otto, Marshall Newton, Tina Gautam, George Tomlinson, and Allan S. Detsky. 2007. The Meaning of Author Order in Medical Research. Journal of Investigative Medicine 55: 174–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, Maite, Anna Villarroya, and Ángel Borrego. 2013. Scientific production in psychology: A gender analysis. Scientometrics 95: 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beehr, Terry, and John Newman. 1978. Job stress, employee health, and organizational effectiveness: A facet analysis, model and literature review. Personnel Psychology 31: 665–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendels, Michael H. K., Eileen Wanke, Norman Schöffel, Jan Bauer, David Quarcoo, and David A. Gronenberg. 2017. Gender equality in academic research on epilepsy—A study on scientific authorships. Epilepsia 58: 1794–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendels, Michael H. K., Ruth Müller, Doerthe Brueggmann, and David A. Gronenberg. 2018. Gender disparities in high-quality research revealed by Nature Index journals. PLoS ONE 13: e0189136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blickenstaff, Jacob Clark. 2005. Women and science careers: Leaky pipeline or gender filter? Gender and Education 17: 369–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornmann, Lutz, and Robin Haunschild. 2019. Societal Impact Measurement of Research Papers. In Springer Handbook of Science and Technology Indicators. Edited by Wolfgang Glänzel, Henk Moed, Ulrich Schmoch and Mike Thelwall. Cham: Springer, pp. 609–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhme, Katja, Doris Klingelhöfer, David A. Groneberg, and Michael H. K. Bendels. 2022. Gender disparities in pediatric research: A descriptive bibliometric study on scientific authorships. Pediatric Research 92: 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinker, Ashley, Jing Liao, Kristen Kraus, Jordan Young, Michelle Sandelski, Catherine Mikesell, Daniel Robinson, Michael Adjei, Sarah Lunsford, Jason Fischer, and et al. 2018. Bibliometric analysis of gender authorship trends and collaboration dynamics over 30 years of Spine 1985 to 2015. Spine 43: E849–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Alexander, and Joshua Goh. 2016. Some evidence for a gender gap in personality and social psychology. Social Psychological and Personality Science 7: 437–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brück, Oliver. 2023. A bibliometric analysis of the gender gap in the authorship of leading medical journals. Communications Medicine 3: 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannady, Matthew A., Eric Greenwald, and Kimberly N. Harris. 2014. Problematizing the STEM Pipeline Metaphor: Is the STEM Pipeline Metaphor Serving Our Students and the STEM Workforce? Science Education 98: 443–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Lijuan, Jing Zhu, and Hua Liu. 2023. Research performance, academic promotion, and gender disparities: Analysis of data on agricultural economists in Chinese higher education. Agricultural Economics 54: 307–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casad, Bettina J., Christina E. Garasky, Taylor R. Jancetic, Anne K. Brown, Jillian E. Franks, and Christopher R. Bach. 2022. U.S. Women Faculty in the Social Sciences Also Face Gender Inequalities. Frontiers in Psychology 23: 792756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascio, Wayne, and Herman Aguinis. 2008. Research in industrial and organizational psychology from 1963 to 2007: Changes, choices, and trends. Journal of Applied Psychology 93: 1062–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassar, Vincent, Frank Bezzina, Sarah Fabri, and Simon Buttigieg. 2020. Work stress in the 21st century: A bibliometric scan of the first 2 decades of research in this millennium. Psychology of Management Journal 23: 47–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castleman, Tanya, and Margaret Allen. 1998. The ‘Pipeline Fallacy’ and Gender Inequality in Higher Education Employment. Policy and Society 15: 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ceci, Stephen J., Shulamit Kahn, and Wendy M. Williams. 2023. Exploring gender bias in six key domains of academic science: An adversarial collaboration. Psychological Science in the Public Interest 24: 15–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, Kam, Chih-Hsiang Chang, and Yuan Chang. 2013. Ranking of finance journals: Some Google Scholar citation perspectives. Journal of Empirical Finance 21: 241–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cislak, Aleksandra, Magdalena Formanowicz, and Tamar Saguy. 2018. Bias against research on gender bias. Scientometrics 115: 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Jacob. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, Jonathan R., and Harriet Zuckerman. 1984. The productivity puzzle: Persistence and change in patterns of publication of men and women scientists. Advances in Motivation and Achievement 2: 217–58. [Google Scholar]

- Cynkar, Amy. 2007. The changing gender composition of psychology. Monitor on Psychology 38: 46. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico, Antonella, Patrizia Vermigli, and Silvia Canetto. 2011. Publication productivity and career advancement by female and male psychology faculty: The case of Italy. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 4: 175–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, Jordan, K. Adam Linn, Eric Teich, Philipp Zurn, Russell Shinohara, and Danielle Bassett. 2020. The extent and drivers of gender imbalance in neuroscience reference lists. Nature Neuroscience 23: 918–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, Alice, and David Miller. 2016. Scientific eminence: Where are the women? Perspectives on Psychological Science 11: 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2021a. EU Strategic Framework on Health and Safety at Work 2021–2027: Occupational Safety and Health in a Changing World of Work. Available online: https://visionzero.global/node/607 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- European Commission. 2021b. She Figures 2021. Gender in Research and Innovation: Statistics and Indicators. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Filardo, Giovanni, Briget da Graca, Danielle M. Sass, Benjamin D. Pollock, Emma B. Smith, and Melissa Ashley-Marie. 2016. Trends and comparison of female first authorship in high impact medical journals: Observational study (1994–2014). BMJ 352: i847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forman-Rabinovici, Aliza, Hadas Mandel, and Alexandra Bauer. 2024. Legislating gender equality in academia: Direct and indirect effects of state-mandated gender quota policies in European academia. Studies in Higher Education 49: 1134–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, Charles W., Josiah P. Ritchey, and Timothy Paine. 2018. Patterns of authorship in ecology and evolution: First, last, and corresponding authorship vary with gender and geography. Ecology and Evolution 8: 11492–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, Catherine, Peter Morris, and Jennifer Richler. 2012. Effect size estimates: Current use, calculations, and interpretation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 141: 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulvio, Jacqueline, Isabela Akinnola, and Bradley Postle. 2021. Gender (Im)balance in Citation Practices in Cognitive Neuroscience. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 33: 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán-Muros, Victoria, Maarten Bouckaert, and Jordi Roser-Chinchilla. 2023. The Representation of Women in Academia and Higher Education Management Positions: Policy Brief. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000386876 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- González-Álvarez, Juan, and Raquel Sos-Peña. 2020. Women publishing in American Psychological Association journals: A gender analysis of six decades. Psychological Reports 123: 2441–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Álvarez, Juan, and Teresa Cervera-Crespo. 2019. Contemporary psychology and women: A gender analysis of the scientific production. International Journal of Psychology 54: 135–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Sala, Francisco, Jorge Haba-Osca, and Julia Osca-Lluch. 2021. Spanish research in educational psychology from a gender perspective (2008–2018). Annals of Psychology 37: 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, June, Jane Mendle, Kristen A. Lindquist, Toni Schmader, Lori A. Clark, Emily Bliss-Moreau, Modupe Akinola, Lauren Atlas, Deanna M. Barch, Lisa Feldman Barrett, and et al. 2021. The future of women in psychological science. Perspectives on Psychological Science 16: 483–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurney, Tammy, Erica Horlings, and Peter van den Besselaar. 2012. Author disambiguation using multi-aspect similarity indicators. Scientometrics 91: 435–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Guyer, Laurie, and Linda Fidell. 1973. Publications of men and women psychologists: Do women publish less? American Psychologist 28: 157–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halevi, Gali. 2019. Bibliometric studies on gender disparities in science. In Springer Handbook of Science and Technology Indicators. Edited by Wolfgang Glänzel, Henk F. Moed, Ulrich Schmoch and Mike Thelwall. Cham: Springer, pp. 563–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, Nick, Lily Ban, Laura Kaufmann, Steve Loughnan, Kate Peters, Jennifer Whelan, and Simon Wilson. 2008. What makes an article influential? Predicting impact in social and personality psychology. Scientometrics 76: 169–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, Luke, Devi Stuart-Fox, and Cindy E. Hauser. 2018. The gender gap in science: How long until women are equally represented? PLoS Biology 16: e2004956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Junming, Alexander J. Gates, Roberta Sinatra, and Albert-László Barabási. 2020. Historical comparison of gender inequality in scientific careers across countries and disciplines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117: 4609–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Labour Organization. 2016. Workplace Stress: A Collective Challenge. Geneva: International Labour Office. [Google Scholar]

- Kataeva, Zumrad, Naureen Durrani, Zhanna Izekenova, and Valeriya Roshka. 2025. Investigating Trends and Developments in Academic Research and Publications on Gender and STEM: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sage Open 15: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Faisal, Michelle Sandelski, John Rytlewski, Jennifer Lamb, Carlos Pedro, Michael Adjei, Sarah Lunsford, Jason Fischer, Andrew Wininger, Elizabeth Whipple, and et al. 2018. Bibliometric analysis of authorship trends and collaboration dynamics over the past three decades of BONE’s publication history. Bone 107: 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, Cornelius, Carina Fell, Laura Kellnhofer, and Guido Schui. 2015. Are there gender differences among researchers from industrial/organizational psychology? Scientometrics 105: 1931–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretschmer, Hildrun, and Isidro Aguillo. 2004. Visibility of collaboration on the Web. Scientometrics 61: 405–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretschmer, Hildrun, Ramesh Kundra, Donald Beaver, and Tobias Kretschmer. 2012. Gender bias in journals of gender studies. Scientometrics 93: 135–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröl, Christian, Philipp Doebler, and Stephan Nüesch. 2017. Meta-analytic evidence of the effectiveness of stress management at work. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 26: 677–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMontagne, Anthony D., Tessa Keegel, Amber M. Louie, Aleck Ostry, and Paul A. Landsbergis. 2007. A Systematic Review of the Job-stress Intervention Evaluation Literature, 1990–2005. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health 13: 268–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larivière, Vincent, Chaoqun Ni, Yves Gingras, Blaise Cronin, and Cassidy R. Sugimoto. 2013. Bibliometrics: Global gender disparities in science. Nature 504: 211–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larivière, Vincent, Ève Vignola-Gagné, Claudine Villeneuve, Pierre Gélinas, and Yves Gingras. 2011. Sex differences in research funding, productivity and impact: An analysis of Québec university professors. Scientometrics 87: 483–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larivière, Vincent, Yves Gingras, Cassidy R. Sugimoto, and Andrew Tsou. 2015. Team size matters: Collaboration and scientific impact since 1900. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 66: 1323–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, Kristina, Yulin Yu, Fred Morstatter, and Jay Pujara. 2022. Gendered citation patterns among the scientific elite. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 119: e2206070119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Kai, Xiang Zheng, and Chaoqun Ni. 2025. Gender disparities in the STEM research enterprise in China. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 12: 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorens, Ana, Athina Tzovara, Laura Bellier, Inbal Bhaya-Grossman, Anne Bidet-Caulet, Winnie K. Chang, Zoë R. Cross, Rosa Dominguez-Faus, Andrew Flinker, Yael Fonken, and et al. 2021. Gender bias in academia: A lifetime problem that needs solutions. Neuron 109: 2047–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longman, Karen A., and Susan R. Madsen. 2014. Women and Leadership in Higher Education. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lönnqvist, Jan-Erik. 2022. The gender gap in political psychology. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 1072494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackelprang, Jessica, Emily Johansen, and Christian Orr. 2023. Gender disparities in authorship of invited submissions in high-impact psychology journals. American Psychologist 78: 333–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliniak, Daniel, Ryan Powers, and Barbara F. Walter. 2013. The Gender Citation Gap in International Relations. Interntional Organizations 67: 889–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malouff, John, Neil Schutte, and Jamie Priest. 2010. Publication rates of Australian academic psychologists. Australian Psychologist 45: 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, Mack D. 2008. A Gendered Pipeline? The Advancement of State Legislators to Congress in Five States. Politics & Gender 4: 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martín, Alberto, Enrique Orduna-Malea, and Emilio Delgado López-Cózar. 2018. A novel method for depicting academic disciplines through Google Scholar Citations: The case of Bibliometrics. Scientometrics 114: 1251–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martín, Alberto, Enrique Orduna-Malea, Anne-Wil Harzing, and Emilio Delgado López-Cózar. 2017. Can we use Google Scholar to identify highly-cited documents? Journal of Informetrics 11: 152–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, Susan, and Judith Rathmann. 2018. How does research productivity relate to gender? Analyzing gender differences for multiple publication dimensions. Scientometrics 117: 1663–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meho, Lokman, and Kiduk Yang. 2007. Impact of data sources on citation counts and rankings of LIS faculty: Web of Science versus Scopus and Google Scholar. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 58: 2105–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milojević, Staša. 2013. Accuracy of simple, initials-based methods for author name disambiguation. Journal of Informetrics 7: 767–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, Kristen Renwick, and William F. Chiu. 2010. Gender Equality in the Academy: The Pipeline Problem. PS: Political Science & Politics 43: 303–08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, Bhaskar. 2009. Do open-access journals in library and information science have any scholarly impact? A bibliometric study of selected open-access journals using Google Scholar. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 60: 581–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naldi, Fiorella, Daniela Luzi, Andrea Valente, and Ilaria Parenti. 2004. Scientific and Technological Performance by Gender. In Handbook of Quantitative Science and Technology Research. Edited by Henk Moed, Wolfgang Glänzel and Ulrich Schmoch. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odic, Darko, and Elizabeth H. Wojcik. 2020. The publication gender gap in psychology. American Psychologist 75: 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Matthew, Joanne McKenzie, Patrick Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy Hoffmann, Cynthia Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Julian Tetzlaff, Elie Akl, Steve Brennan, and et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372: n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagel, Paul S., Julie K. Freed, and Cynthia A. Lien. 2019. A 50-year analysis of gender differences in United States authorship of original research articles in two major anesthesiology journals. Scientometrics 121: 371–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaconstantinou, Harry T., and Terry C. Laimore. 2006. Academic Appointment and the Process of Promotion and Tenure. Clinic in Colon and Rectal Surgery 19: 143–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peñas, Cristina, and Peter Willett. 2006. Brief communication: Gender differences in publication and citation counts in librarianship and information science research. Journal of Information Science 32: 480–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prpić, Katarina. 2002. Gender and productivity differentials in science. Scientometrics 55: 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkó, Andrea, Csilla Herendy, Manuel Goyanes, and Marton Demeter. 2023. The Matilda Effect in Communication Research: The Effects of Gender and Geography on Usage and Citations Across 11 Countries. Communication Research 52: 209–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoten, Diana, and Stephanie Pfirman. 2007. Women in interdisciplinary science: Exploring preferences and consequences. Research Policy 36: 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, Kathleen, and Howard Rothstein. 2008. Effects of occupational stress management intervention programs: A meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 13: 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roper, Rebecca L. 2019. Does gender bias still affect women in science? Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 83: e00018-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri, Roberta, Fabrizio Pecoraro, and Daniela Luzi. 2021. An intersectional approach to analyse gender productivity and open access: A bibliometric analysis of the Italian National Research Council. Scientometrics 126: 1647–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Jiménez, Rocío, Patricia Guerrero-Castillo, Vicente P. Guerrero-Bote, Gali Halevi, and Félix de Moya-Anegón. 2024. Analysis of the distribution of authorship by gender in scientific output: A global perspective. Journal of Informetrics 18: 101556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]