Abstract

The growing influence of social media on political processes extends beyond electoral campaigns and is rapidly transforming the communication practices of incumbent leaders. We address the gap between populist practices in electoral marketing and the implementation of the Ecuadorian president’s discursive strategies from a geopolitical perspective, with a special focus on the use of two platforms: Instagram and TikTok. While existing scholarship has generally analyzed populist discourse on social media, this article applies theoretical and methodological tools to analyze the grammar of war and the performative strategies used to build leadership in contexts of high social unrest. Grounded in contemporary perspectives. This article reveals how populist leaders mobilize emotions through narratives on digital platforms to frame political crises. Using qualitative critical discourse analysis with multimodal and semiotic tools, we examined 156 posts from the official TikTok and Instagram accounts of Ecuadorian President Daniel Noboa, published between January and July 2024. The findings highlight the strategic use of patriotic symbolism, personalization, and emotional appeals to legitimize executive actions and disseminate polarizing narratives. The proposed framework demonstrates how social media communication simplifies complex crisis scenarios into affect-laden “good versus evil” narratives. This model is transferable to other geopolitical and digital contexts, offering both conceptual and methodological tools for analyzing conflict-driven political communication.

1. Introduction

1.1. Discursive Strategies of Daniel Noboa on TikTok and Instagram During the Internal Armed Conflict in Ecuador (2024)

In recent years, socio-digital platforms have emerged as key arenas for political communication, exerting significant influence and gaining legitimacy in matters of broad social relevance (). Scholarly literature has approached this transformation from diverse theoretical and methodological perspectives. Research has explored the effects of socio-digital networks on political mobilization and civic engagement (), the construction of political image and the use of digital platforms for political marketing (), the circulation of banal political discourse through digital media (), as well as the detrimental consequences of these platforms in fostering disinformation and intensifying political polarization. Political polarization—defined as the divergence of political opinions, beliefs, and attitudes (ideological polarization), along with the intensification of negative emotions toward political opponents (affective polarization)—has been identified as a defining characteristic of contemporary political dynamics (). This phenomenon represents a growing global concern, significantly exacerbated by the role of social media platforms. Digital media contribute to the deepening of polarization by facilitating the formation of “echo chambers” and “filter bubbles,” mechanisms that amplify pre-existing beliefs due to users’ tendencies toward homophily and selective exposure to ideologically congruent content (; ). These dynamics are particularly leveraged by populist leaders (; ; ), who employ a stylistic repertoire centered on “friend-enemy” polarization and antagonistic “us versus them” narratives (; ). As () explains, “this understanding of populism tends to highlight how ideas are conveyed, and the discourse is performative through a certain stylistic repertoire that appeals to friend-enemy polarization, the ‘us versus them’ antagonism”. Political polarization is one of the foci of the present study.

From a communicative standpoint, socio-digital networks have become relevant spaces that facilitate direct interaction between citizens and political leaders. These platforms promote dialogue and interactivity and have even been associated with increased voting intentions (). As () observe, “importantly, social media marketing allows politicians to reduce their psychological distances with the voters”. Certain platform-specific characteristics—such as immediacy, personalization, and bidirectional communication—enhance their widespread adoption in political contexts, particularly during electoral campaigns. However, it is crucial that research continues to investigate these dynamics, as () warn that “today’s digital environment frequently cultivates division, the spread of disinformation, and hostility. This transformation poses a significant threat to the quality of democratic discourse, as genuine political engagement risks being replaced by superficial interactions and increasing polarization” (p. 6). From the perspective of critical discourse analysis, it is possible to deepen the scholarly understanding of how the Internet and digital social networks have changed the ways in which the political world communicates with citizens. This method follows the approach of Fairclough, Machin and Mayr, who consider political communication to be a multimodal discursive practice where text, image and visual design configure ideological meanings. Digital formats go beyond the linguistic, incorporating video, photographs, phrases, design and live broadcasts that seek impact and virality (; ). This digital environment, by fostering more horizontal and decentralized communication, has fundamentally redefined civic participation and political discourse, where visibility and impact are paramount (; ; ).

In this global context, the Latin American political landscape is highly susceptible to the increasing influence of digital strategies, especially concerning populism, disinformation, and political polarization (). A notable example is Ecuador, where recent presidential elections have been significantly shaped by digital communication strategies (). The 37-year-old President Daniel Noboa, a prominent political figure and candidate for re-election, is an active user of socio-digital networks and has been described as an “influencer” (). His personal TikTok account possesses significantly more followers than the institutional accounts of the Presidency and Secretariat of Communication (). On both Noboa’s personal and the presidency’s institutional TikTok accounts, security is one of the most frequently addressed topics (). However, on his personal TikTok, these messages share prominence with aspects of his personal life and strategies to position his political slogan “El Nuevo Ecuador” (). Importantly, both Noboa’s first term and the campaign for his re-election were marked by one of the worst security and violence crises the country has faced in its history, in addition to a serious energy crisis and dire economic situation. The January 2024 declaration of a state of exception, widely publicized through social media posts, illustrates how governmental measures were converted into emotionally resonant digital storytelling that aligned with the ‘grammar of war ().

The contextual background is acknowledged—marked by violence, insecurity, and governance challenges—but its analytical function lies in showing how such events were discursively reframed in Noboa’s digital communication. Rather than repeating statistical details, the study demonstrates how crises became narrative resources that legitimize measures, frame leadership, and mobilize emotional cohesion. In this context, the main objective of this research is to analyze the discursive strategies of Ecuadorian President Daniel Noboa on Instagram and TikTok from January to July 2024, to delineate conceptual distinctions and practical implications for the professional field of political communication. We aim to answer the following two research questions:

- (1)

- Which discursive strategies characterize the official governmental communication of President Daniel Noboa during the internal conflict in Ecuador (January 2024), and how do these strategies align with crisis communication frameworks in governmental political communication?

- (2)

- To what extent do the discursive strategies and media formats utilized in the presidential communication of Daniel Noboa contribute to the propagation of polarized and homogenizing narratives, and what role does disinformation play in shaping these communicative patterns?

The temporal scope of the investigation was determined considering the style, tone and positioning metrics on the videos published in the official accounts, from the issuance of Executive Decree 111, in which the president acknowledged the existence of an internal armed conflict in Ecuador. The article is structured into four sections: a theoretical review of digital political discourse, a methodological description of the multimodal analysis, the results of the analysis and a discussion with conclusions.

In contrast to existing studies centered on more frequently examined regions and platforms, this article contributes a novel perspective by analyzing the case of Ecuador—a country largely underrepresented in the field of digital political communication (). It focuses specifically on presidential discourse during an internal armed conflict, framed through the aesthetic and affective affordances of Instagram and TikTok. This dual emphasis—on a geopolitically neglected context and on highly performative platforms—offers new analytical ground for understanding how digital media are mobilized to construct legitimacy, identity, and symbolic authority in crisis scenarios.

1.2. Discursive Strategies in Socio-Digital Networks: Polarization, Homogenization and Bullshit in Governmental Communication

The field of governmental political communication has been approached from various disciplinary perspectives, reflecting the complexity of its objects of study and methodological approaches (). However, the rapid evolution of socio-digital networks has transformed the logic of political discourse, requiring a reevaluation of how messages are constructed, disseminated, and received in highly mediatized contexts (). In this framework, it is essential to examine not only the formats and platforms used by political actors, but also the discursive strategies that produce symbolic legitimacy and emotional adhesion within digital arenas marked by fragmentation and virality. Drawing from critical discourse analysis (; ) and media ecology (), the present study adopts an integrative analytical lens that considers socio-digital networks as environments of affective production and narrative framing. These environments are shaped by the logics of personalization (), theatricalization (), and algorithmic amplification, which jointly redefine the modes of interaction between political leaders and citizens. As () note, the adoption of digital technologies is not merely instrumental but structural, reshaping civic participation through hyperconnectivity and symbolic immediacy.

Conceptually, this study introduces and applies the notion of a “grammar of war” as a strategic discursive framework through which political actors legitimize exceptional measures during states of crisis. This concept is analytically productive and aligns with broader theories of political communication that emphasize the performative and securitizing function of language in emergency contexts. As () notes, crisis narratives often operate through binary oppositions and the strategic use of fear to construct cohesion and authorize executive action. Similarly, () has shown how metaphorical war framings—such as the “war on terror” or “war on drugs”—activate emotional frames that reduce complexity, enable symbolic polarization, and mobilize public support. By grounding the concept of the “grammar of war” in contemporary perspectives (; ; ; ) and employing multi-modal discourse analysis, this study contributes to understanding how affective, sym-bolic, and aesthetic resources are orchestrated on platforms like Instagram and TikTok to portray leadership as heroic and the opposition as an existential threat. In this sense, the grammar of war functions as a flexible rhetorical tool that transforms crises into morally charged narratives of good versus evil, reinforcing a politics based on fear and urgency

The Ecuadorian case during the 2024 internal armed conflict illustrates this with clarity. Governmental discourse employed deliberate strategies of narrative simplification and emotional intensification, using war metaphors to construct meaning, legitimizing military intervention, and creating polarized identity binaries. These rhetorical mechanisms include the construction of antagonistic oppositions—such as “us versus them” (; )—and the deployment of emotionally charged imagery that positions the president simultaneously as protector, father, and commander. As () suggest, this grammar is not incidental but instrumental: it symbolically reconfigures reality by reframing insecurity as a battlefront and governance as wartime leadership. The deployment of fear as a mobilizing effect () further deepens this dynamic.

Future research would benefit from expanding the operationalization of the “grammar of war” to include comparative, cross-platform, and longitudinal approaches that explore how this framework adapts across regimes, technologies, and political ideologies.

The personalization of political discourse operates as a central axis of digital legitimacy. Through curated representations of private life, emotive appeals, and symbolic gestures, political actors construct what () terms “the show of the self”—a public performance of authenticity that simultaneously humanizes and mythologizes the leader. This personalization, far from diluting the political, reinforces strategic branding by associating the leader with desirable affective traits such as strength, closeness, and resilience (; ).

Complementarily, marketing-oriented strategies such as inbound political communication () emphasize engagement through structured processes of attraction, conversion, and emotional retention. These dynamics are especially visible in electoral or crisis-driven scenarios, where the call to action is embedded in emotionally charged narratives that appeal to collective fears and hopes. The personalization and spectacularization of leadership are thus embedded in a broader communicative model where political discourse becomes both a product and a performance (; ).

The notion of bullshit, introduced by (), is a key analytical category for understanding contemporary political discourse in digital environments. Unlike lying—where the speaker deliberately knows the truth and seeks to distort it—bullshit is characterized by indifference toward the truth. The bullshitter does not aim to conceal or falsify facts but rather to persuade, impress, or mobilize emotions regardless of whether statements are true or false. In this sense, bullshit operates less as a mechanism of information and more as a discursive practice oriented toward symbolic and affective effects on audiences.

Several scholars have expanded on this framework. () and () emphasize that bullshit shifts the focus of discourse away from questions of truth and falsity toward questions of rhetorical efficacy. () situate it within the epistemological concerns of the digital era, where the boundaries between error, lies, and spectacle are blurred. () further demonstrates that “bullshit pays” in politics, insofar as ambiguity, vagueness, and empty promises prove effective in maximizing attention without requiring factual accountability. In the Latin American context, () link these discursive practices to post-truth dynamics, where emotional resonance and virality outweigh empirical verification.

In governmental social media communication, bullshit manifests through ambiguous statements such as “we will never yield to evil”; through grandiose yet unfeasible promises such as “restoring peace”; and through conspiratorial accusations lacking verifiable evidence, which are intended to mobilize popular indignation. These discursive maneuvers function as what () terms affective disinformation: strategies designed to generate emotional resonance and digital shareability rather than factual accuracy. Moreover, the contradiction between campaign promises and subsequent governmental actions—such as increasing the VAT despite earlier denials of tax reform—illustrates what () describes as discursive manipulation of truth. Ultimately, bullshit aligns with what () identified as the “society of the spectacle,” in which the political value of discourse derives not from its factuality but from its ability to circulate as images, symbols, and affects across media platforms. Far from being a marginal or accidental residue of political communication, bullshit constitutes a strategic resource in the construction of legitimacy. It reinforces simplified narratives, sharpens polarized identities, and erodes the conditions of democratic deliberation based on rational argumentation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study employs a qualitative–interpretative methodology grounded in Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), drawing upon the theoretical frameworks of Fairclough and van Dijk. This approach facilitates the examination of power relations, ideological formations, and symbolic domination within political discourse. In addition, a semiotic and performative analysis was incorporated, which is particularly well-suited for analyzing content on visual and interactive platforms such as Instagram and TikTok, where meaning is constructed through gesture, scenography, music, and visual effects.

A Foucauldian lens was also applied, particularly the notion of “domains of truth,” to interrogate how certain discursive statements become legitimized as truth claims without requiring empirical validation. Furthermore, to deepen the multimodal analysis of political content on social media, the study draws on the analytical framework proposed by (), which identifies key elements for evaluating individual political content on platforms such as Instagram and TikTok. These include visual resources (e.g., gendered signifiers conveyed through clothing, posture, gesture, and facial expression), linguistic and discursive strategies (e.g., forms of self-presentation, rhetorical style, the use and function of hashtags, and figurative language), and explicit or implicit forms of political stance-taking (e.g., engagement with political controversies, and the evaluative language used to construct adversarial positions).

2.2. Justification of the Period Analyzed

The period from 1 January to 31 July 2024 was selected due to its high political relevance. It begins with the issuance of Executive Decree No. 111, which declares an internal armed conflict in Ecuador, and it includes the campaign prior to the referendum and popular consultation promoted by the president. This interval allows us to observe a phase of high discursive intensity and strategic positioning in government communication.

2.3. Corpus Definition and Sampling

The corpus for this study consists of 156 audiovisual publications extracted from the verified official accounts of President Daniel Noboa on Instagram and TikTok. The sample follows a comprehensive theoretical–intentional sampling strategy, rather than a partial or randomized selection. Inclusion criteria were as follows:

Content published through the president’s verified official accounts.

Exclusively audiovisual formats (videos, reels, live broadcasts).

Politically relevant content, either explicit or implicit, addressing themes such as security, governance, polarization, or citizen participation.

High levels of user interaction, measured by number of “likes,” comments, shares, and overall digital visibility.

Posts of a strictly protocolary nature or lacking recognizable political content were excluded from the corpus.

2.4. Data Collection and Processing

Data was collected through non-participant observation of the official social media profiles. The final dataset includes:

94 Instagram posts;

26 TikTok videos;

36 cross-posted publications appearing on both platforms.

All content was downloaded and securely archived using digital tools, and subsequently processed using MAXQDA software, enabling both categorical coding and semantic trend analysis.

To guide the multimodal analysis of visual content, this study employs the analytical framework (see Table 1) proposed by (), which provides a systematic and theoretically grounded model for interpreting political communication on social media platforms. The framework facilitates an integrated examination of the semiotic, discursive, and affective components that underpin digital political discourse. It is structured around three core analytical dimensions:

Table 1.

Overview of elements to consider of individual political content on Instagram and TikTok. Analytical framework Source: ().

- (1)

- Visual resources, which include gendered signifiers expressed through elements such as clothing, posture, gestures, and facial expressions.

- (2)

- Linguistic and discursive strategies, referring to modes of self-presentation, rhetorical style, the use and communicative function of hashtags, and the deployment of figurative language; and

- (3)

- Political stance-taking, encompassing references to political controversies and the use of evaluative language aimed at constructing or reinforcing adversarial relationships. This last dimension is analyzed in connection with the argumentative chaining model developed by (), which allows for a deeper understanding of how discursive alignments and oppositions are rhetorically structured.

2.4.1. Analytical Categorization and Coding Matrix

A coding matrix consisting of four analytical axes was constructed, based on the critical literature and political communication studies:

- Homogenization of minds and bodies: discourses that promote symbolic, ideological or aesthetic uniformity in institutions and media.

- Narrative encirclement: narrative restrictions imposed by the logics of digital platforms, which define what is visible and what is decipherable.

- Show of the self: spectacularized personalization of the presidential figure, based on strategies of emotionality and closeness.

- Bullshit: a category based on Harry Frankfurt’s concept, which allows for the identification of empty or evasive contents that are presented as truth, without worrying about their veracity, and which appeal to emotional persuasion.

Each category was operationally defined and applied to the corpus through a structured process of open coding, which made it possible to identify semantic maneuvers, prevalence and discursive trends.

2.4.2. Analytical Rigor and Validation

To ensure the validity of the analysis, the following strategies were applied:

- Analytical triangulation between platforms and categories.

- Theoretical saturation, concluding the coding when no new discursive patterns emerged.

- Peer review, where experts in political communication and digital media reviewed the coding matrix and preliminary findings.

Ethical considerations

The study analyzes publicly available content issued by a public figure in the exercise of his or her duties. In accordance with standard ethical principles, informed consent was not required. A rigorous, critical and respectful approach was maintained, avoiding any partisan bias or subjective interpretation.

3. Results

The results of this study are divided into two parts: first, the identification of the discursive strategies of President Daniel Noboa, and second, the description and analysis of how bullshit and polarization operate in the official discourse.

3.1. Strategies Identified in Daniel Noboa’s Discourse

This research focused on the analysis of discursive strategies in the governmental communications of President Daniel Noboa in Ecuador, in the context of the internal armed conflict of January 2024. It also sought to understand political communication as a permanent field of polarization that is potentially based on misinformation. Based on the application of the different methodological tools of critical discourse analysis, four strategies were identified in President Noboa’s discourse:

- Use of a grammar of war

The first is directly linked to the communicative event from a semantic–pragmatic perspective. In this sense, the predominant discursive strategy in the context of the internal armed conflict (the processual perspective of discourse) is the use of a grammar of war through the terms “Internal Armed Conflict”. This grammar installs domains of truth and reconfigures the understanding of reality and the place of the actors in this framework which, according to (), allows for a configuration and recalibration of the roles of the political actors at a specific juncture.

Information processing shows how the use of basic linguistic units adopted in the 156 publications operates in the selected context: Ecuador, security, peace, country, Ecuadorians, the new Ecuador, and families. From this perspective, based on the social structures, we first observe the reconfiguration of the scenario of crisis and social upheaval, in which polarized and radical discourses easily permeate audiences’ awareness. In addition, it establishes a positive correlation with the implementation of actions against organized crime groups and generates in the population the feeling of permanent and timely work in the face of the political discourse on welfare.

Speeches and messages are conveyed through rhetorical figures in the form of monologues designed with high levels of detail to excite, offer, mystify, terrorize or hide important details about national problems; additionally, concealment that is neither problematized nor questioned is also typical of the complex relationship between rulers and the ruled. To support the above analysis, we conducted argumentative chaining of communications with the highest degree of virality to understand how the social construction of fear operates (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Argumentative chaining own elaboration.

Thus, in terms of the orders of discourse, these manifest in the representations of the world, the roles of people, or ways of seeing life; thus, the links between these linguistic units establish new forms of reason and almost unquestionable truths in terms of discursive variations. Thus, these units also represent verbal markers that establish identities for the speakers themselves and their adversaries, as shown in the following subsection.

- b.

- The configuration of good guys and bad guys

The second strategy is related to the approach to social reality, based on the questioning of social structures and power relations. The configuration of good guys and bad guys establishes a critique of the democratizing promise of technologies, because socio-digital networks are increasingly presented as favorable spaces for the amplification of polarized and radical viral discourses. These discourses are especially prevalent when working on issues related to armed conflicts and communication.

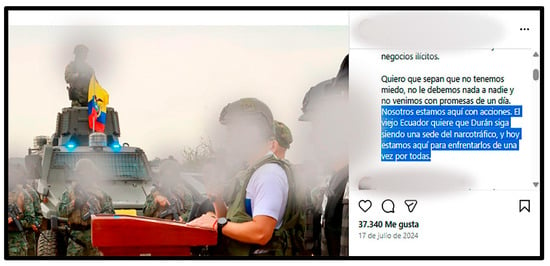

In this analysis, the discourse on “us” in publications with greater levels of virality among the public was taken as a reference, in such a way that it is possible to observe (see Figure 1) the process of the construction of “good” and “bad”. This shows the persuasive strategies in dialogue with the argumentative tactics of an “us–them” through the simplification of ideas, which generates stereotypes, achieving the permanent inoculation of negative imaginaries about adversaries and enemies.

Figure 1.

Publication on the construction of we–they. Source: https://www.instagram.com/p/C9h2Q3TxjWs/?img_index=1 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

Based on the analysis of the categories, Figure 1 shows the application of semantic maneuvers related to the use of traditional colloquial terms, which would only be understood according to specific cultural frameworks, and which are implemented to gain mass agreement. Here, it is worth mentioning the construction of one’s own image, whereby one distances oneself from others but, at the same time, constructs the image of those others. The use of deictic elements such as “us–them” and “honest–criminal” once more reflects the binarism’s and the heroic image to be shown and strengthened, versus the configuration of “them” not as anti-heroes, but as enemies. On this basis, it is determined that the Armed Forces and the National Police in the digital media narrative of the “good guys versus bad guys” are exalted by Noboa as the true heroes of the homeland. It is therefore possible to affirm that there is a reiterative manipulation of public opinion by presenting the government and the forces of order as the only defenders of the good, while any criticism or dissent is seen as a threat.

This finding manifests in everyday life, where Noboa’s government has created an “excluding us” called “The New Ecuador” and a ‘them’ referred to as “The Old Ecuador”. This strategy, according to the study, serves to feed the idea that political opponents or the non-aligned are enemies to be defeated.

- c.

- The creation of content related to inbound marketing

Third, there is the application of strategies based on political marketing: specifically, on the creation of content related to inbound marketing. Here, we observe the characteristics of the “call to action” as a discursive social practice that appeals to the emotions and affections of the public. To better understand this subsection of findings, it is necessary to refer to the contextual level of the analysis; after the declaration of the internal armed conflict, a popular consultation and constitutional referendum were called in April 2024, with the purpose of making legally viable the governmental decisions regarding the fight against insecurity.

It should be noted that, in this type of call to action, known as interaction, actions predominate. These are based on emotional reactions such as “I like,” commenting directly on publications, and sharing the original message to amplify governmental political discourse. According to the data obtained, the predominant call to action is related to support for popular consultation, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Argumentative chaining, own elaboration.

Now, if we consider again the chaining of texts, we can identify how the call to action is related to basic units such as country, Ecuador, government, peace, order and the hardening of laws (see Table 4). It should be noted that this finding allowed us to focus the analysis on the argumentative function of the general text (copy) and to interpret, from a microtextual dimension of the call to action, the discursive maneuvers as explanations, justifications, objectives, ways of seeing life, and ways of doing some things and not others. This argumentative chaining is not gratuitous and allows us to reflect on the configuration of a macrostructure that functions discursively to invite a position in favor of the national government on the popular consultation. This position is linked to security and a hypothesis of future peace that would be restored through actions related to social order and the tightening of laws, as shown in Figure 3.

Table 4.

Argumentative chaining call to action. Own elaboration.

In light of the above analysis, the tactic of the call to action emerges; in times of electoral pre-campaigns (with a concrete objective of reelection), political actors make frequent use of the appellative function, which is only possible through a communicative machinery in which the presidential figure is presented as loaded with signs and spectacle, rather than focused on social dialogue.

- d.

- The theatricalization, spectacularization and dramaturgy of power

The last finding regarding discursive strategies has to do with the theatricalization, spectacularization and dramaturgy of power, which allows us to analyze the image as a product in a large consumer market of intangibles. In this case, a public figure—such as the President of the Republic of Ecuador—plays a role in the theatrical plot of digital social network platforms, highlighting his performance and the representation of the good leader, the good citizen, the good administrator and the good father of the family. This represents a sort of media show business tactic, alongside Faustian proposals for the presentation of everyday life.

We highlight the ways in which the “I” and many “I’s” are presented on socio-digital networks and how spectacularization and dramaturgy are applied to represent normative ideals of success, leadership and management by objectives. To this end, use is made of the humanization of the political actor, which is also called personalization. Personalization is shown as a successful formula of persuasive characteristics that takes symbolic resources and personal characteristics to build, from a social perspective, the image of a good leader with sufficient power, authority and leadership.

This is articulated with the chameleonic forms adopted by Noboa, which allow him to turn from a loving father and husband to a civilian who plays the role of the country’s savior hero with the clothing of the forces of order or loaded with patriotic symbolic codes (see Figure 3). This shows a sort of mosaic identity that is expressed in a distributed manner in its attributes or features, according to the intentions, context and political objectives of any public figure with a high level of exposure. Furthermore, following the analysis of personalization and the show of self, the application of “the person as message” proposed by Orejuela 2009, stands out. The image of the president is itself the center of the discursive strategy and the point of reference and context of the messages disseminated, as shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Daniel Noboa highlights his role as a father in an image with one of his children. Source: https://www.instagram.com/p/C8KaOtnRHNN/ (accessed on 15 January 2025).

Figure 3.

Daniel Noboa with patriotic symbols. Source: https://www.instagram.com/p/C2Dn7wyruoi/?img_index=1 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

The contextualization of Ecuador’s crisis—defined by violence, the declaration of an internal armed conflict, and governance instability—serves as a backdrop rather than the analytical center of this study. Instead of detailing homicide rates or isolated violent episodes (; ), the focus is on how such events were translated into narrative resources within presidential digital communication. Emblematic incidents, such as the January 2024 state of exception or the TC Televisión takeover, are significant insofar as they were discursively reframed to legitimize exceptional measures and position the president as a heroic figure.

Through Instagram and TikTok, Noboa deployed a “grammar of war” that reduced structural insecurity into emotionally resonant binaries of “heroes” versus “villains”. This performative framing aligns with broader research on securitizing discourse and the transformation of politics into spectacle (; ). Visual symbols (military uniforms, patriotic emblems, family imagery), combined with linguistic devices (deictics, war metaphors), reinforced cohesion through fear and polarization (; ). Finally, the study identifies the role of bullshit as an affective disinformation tool. Ambiguous statements such as “we will not yield to evil” and vague promises like “restoring peace” exemplify what () terms affective disinformation—discursive maneuvers designed for virality and emotional impact rather than factual accountability. By showing how crisis events became discursive assets, the analysis demonstrates how leadership was spectacularized, affect strategically mobilized, and deliberative dialogue eroded.

3.2. Governmental Political Communication as a Field of Polarization Potentially Based on Disinformation

The type of story and narrative presented in the publications from the voice of power is analyzed in the light of concepts such as homogenization and bullshit. In this specific context, the positioning of the unified political discourse predominates through narratives transferred to textual and audiovisual formats in micro videos. In this sense, this study shows that the homogenization of thought operates according to the domains of truth installed from socially legitimized voices, as well as according to the dynamics of the channels through which a particular discourse is amplified based on the logics of information consumption and all kinds of cultural artifacts such as memes, gifs and videos that exalt the voice of power. The use of micro videos (in 121 out of 156 publications) and images (25 out of 156 publications) was predominant, and the prevalence of cinematographic narratives, musicals, image sequences and parodies.

Regarding the predominant use of micro videos, we highlight that this is the most consumed format in terms of the economy of language and economy of attention, according to the case study. The informative framing presents between 30 and 45 s of a thread of ideas set to epic music in most cases or, in turn, hopeful melodies with a specific cast that contribute to the story being told (especially for citizens and elements of the public force). However, if the dialogic spaces of governmental political communication are more frequently replaced by the video politics of socio-digital networks, the characteristics of a deliberative politics change and spectacle appear.

It is a micro video, as a cultural artifact, which determines how to tell a story in terms of conveying a desired image to the public. Therefore, this format connects with the homogenizing process in terms of the communication expected from the constituents. From that moment on, everything is possible, and we find ourselves facing a weak party system hidden behind a strong communicational industry, governed by three rules: spectacle, television format and simulacrum.

In this order of ideas, homogenization—as a political strategy—operates with docile minds and bodies that permanently adapt to the communication systems in force in time and form: very short videos, preventive inoculation of enemies, fashionable music, the call to “bury the past” and the use of popular culture characters, which establish a way of thinking and doing through the constant mobilization of emotions and isolated data that could not be understood as information, let alone knowledge.

Moreover, data processing shows that one of the ways in which disinformation operates has to do with bullshit. As discussed above, as an analytical category, bullshit allows us to identify the predominant discursive maneuvers of the Ecuadorian president. In this case, the maneuver identified is unfulfilled promises and justification with the use of the appellative functions of language. Although Daniel Noboa promised not to carry out tax reforms during his electoral campaign, in 2024, as president, he decided to increase value added tax (VAT) from 12% to 15%. His arguments were that financing was required for the internal armed conflict. In this way, he appealed to citizen support through his networks to recover security and welfare, as shown in Figure 4; however, this measure was taken mainly to ensure the country’s fiscal sustainability. This situation sparked criticism not only because of the contradictions between his campaign speech and official acts, but also due to the destination of the economic resources collected with this additional contribution.

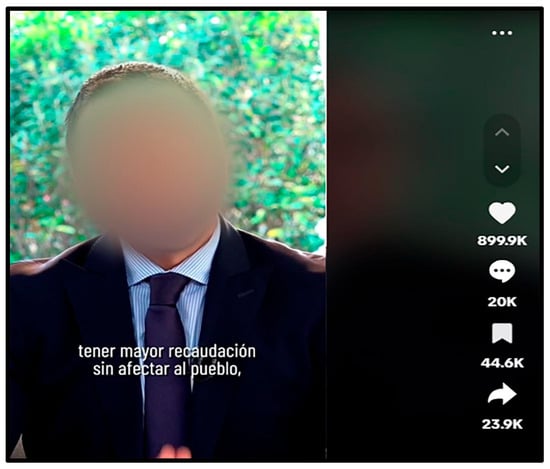

Figure 4.

Daniel Noboa affirms that the VAT increase will contribute to financing the internal armed conflict. Source: https://www.tiktok.com/@danielnoboaok/video/7329933839046937861 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

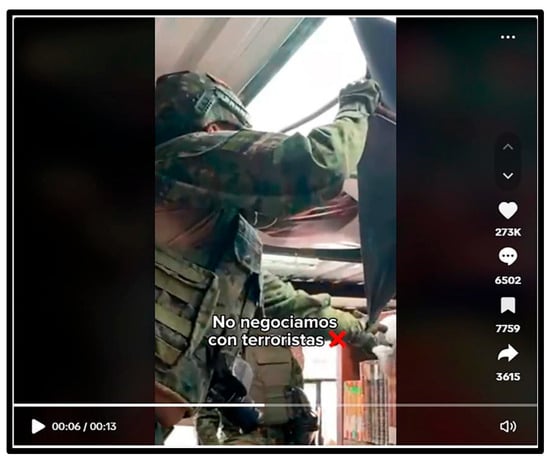

Between events and the construction of events, audiences can become lost, unable to distinguish between what is true and what is not or not at all. This is because narratives and finely constructed stories operate in a sophisticated way, such that all interest is lost in the search for details about the stories being told. The artifices of bullshit are expressed in ways that are increasingly crafted to appear as spontaneous as possible, leaving no room for doubt but for imagination or the interpretation of those events. This is visualized in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Daniel Noboa: “Never give in to evil”. Source: https://www.tiktok.com/@danielnoboaok/video/7323378683547274501 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

The president’s statement, which is included in this reel and is part of a speech made during the declaration of war against organized crime groups, is reinforced by other insights that make up this narrative. The following statement stands out: “We do not negotiate with terrorists”. This corroborates Noboa’s government’s insistence on attributing to its main opponents a pact with the mafias, which would make them supposedly responsible for the insecurity experienced by the country. This is how diverse bullshit strategies are evidenced in four key respects, as analyzed below.

- Strategic ambiguity: when Noboa states that he “will never give in to evil,” he uses an ambiguous construction that insinuates firmness and principles but does not specify which “evil” he is referring to. This results in his phrase being interpreted in different ways by the receivers, since he could be referring to criminal gangs, to his political opponents, or to both actors. This ambiguity allows him to evade responsibility and shape his discourse (in “saying without saying”) towards the identification of culprits in past governments, as is also observed in the frequency content in the copy of the publications examined.

- Use of conspiracy theories: the above strategy is connected to conspiracy theories, a characteristic resource of bullshit. The narrative is fabricated with the idea that the opposing group is the villain and the one that is constantly boycotting “the good deeds” of those who exercise power to “fight tirelessly” to solve inherited problems. This accusation is almost never accompanied by verifiable evidence. The aim is a kind of political entertainment that convinces the citizenry that, to put an end to the insecurity in the country, the opposition must be “buried forever”.

- Appealing to nostalgia, guilt and condemnation: among the appellative functions is the technique of nostalgia and condemnation—in this case, the condemnation of treason, with the purpose of provoking popular indignation. The construction of this rhetoric is based on the fact that a political group that governed in the past betrayed its constituents by “allying” with members of criminal groups, a situation that would not be repeated in the current government where unlike “the others,” values prevail.

- The fanciful metaphor: In the fourth and final aspect of the bullshit of Noboa’s discourse, as shown in Figure 5 promises that are difficult to fulfill are made. Noboa promises “to return peace to the Ecuadorian people”. This is supported by a fanciful metaphor about a heroic struggle against evil that does not give details about the means of combatting insecurity in the short, medium, or long term.

Thus, the media narrative is based on promises that often lack a foundation and viability. This narrative simplifies violence and insecurity in the country to a fight between “heroes” and “villains (see Table 5)”. This does not imply that we do not recognize that there are elements of subjectivity in the truth; however, it is necessary to recover the need for accuracy. The attempt to pass off the false as true is what damages the truth, because it is not easy to distinguish what is true from what is not, especially if, based on the current forms of access and consumption of information on digital platforms, audiences are lost in speeches that prevent the swamp from being drained of charlatanism.

Table 5.

Minimal Descriptive Quantification of Discursive Strategies in Noboa’s Instagram and TikTok Posts (January–July 2024).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The findings of this study allow us to understand how political–governmental communication strategies in digital networks operate within deeply affective, performative, and polarizing logics. An important element in the grammar of war is the social construction of fear that operates according to the principle of the symbolization of difference.

This is achieved through the hashtag #ElNuevoEcuador, which is repeatedly present at the base of the storyline.

Based on the qualitative analysis of presidential discourse on Instagram and TikTok during the internal armed conflict declared in Ecuador in 2024, we identified discursive maneuvers that transcend the simple dissemination of information. These maneuvers align with processes of symbolic construction, power legitimation, and the diffusion of simplified narratives around structurally complex issues.

This research does not propose a technophobic stance but rather a critical analysis of the unfulfilled promise of socio-digital platforms as spaces of democratic deliberation. The evidence shows how dialogue is displaced by narrative simplification and emotional spectacle. Considering ’s () framework, we interpret these phenomena as a “staging of governance,” in which political leadership is no longer legitimized by verifiable arguments but by its performative, aesthetic, and viral effectiveness.

4.1. Discursive and Institutional Homogenization: Semiotic Circulation and Repetition

The homogenization axis reveals a sustained tendency to replicate uniform messages across public institutions, marked by similar narrative and aesthetic structures. This logic follows the algorithmic rationality of digital platforms, which reward viral formats while simultaneously restricting discursive diversity. As () observed, this dynamic extends the docility of bodies and minds to the digital realm. Within ’s () analytical framework, such repetition functions as a strategy of meaning fixation, where dominant signs are strategically recirculated to generate public alignment and minimize interpretive dissent.

4.2. Narrative Encirclement: Platforms as Epistemic Fences

Social media platforms act as semantic fences, regulating what can be said and amplifying meanings that align with official discourse (e.g., security = strong hand) while rendering structural causes of violence invisible. This phenomenon resonates with ’s () and ’s () notions of “epistemic reduction,” and aligns with ’s () idea of “restrictive communicative design,” whereby binary, emotionally resonant narratives are favored over cognitively complex ones.

4.3. Political Performativity and the Aestheticization of Leadership

The “show of self” axis reveals a systematic theatricalization of the presidential persona, who is represented as a heroic, sensitive, and effective leader. These representations are strategically constructed through emotional content, symbolic gestures, and key rhetorical terms (“unity,” “values,” “honesty”). Following (), this performative aesthetic transforms the political subject into a symbolic commodity, where the leader’s body functions as a visual and affective authority device. This reflects ’s () “society of the spectacle,” in which politics becomes performance, and public policy is overshadowed by image management.

4.4. Bullshit as a Strategy of Affective Disinformation

We identified a consistent use of what () termed “bullshit”: ambiguous statements (“we will not yield to evil”), vague promises (“we will restore peace”), and emotional justifications for controversial decisions such as the VAT increase. These are not merely rhetorical inconsistencies, but deliberate mechanisms of affective disinformation aimed at generating public support without factual accountability. As () notes, bullshit serves as a highly effective semiotic tool in digital contexts—adaptable, emotionally resonant, and easily shareable.

4.5. Critical Appraisal and Limitations

Although this study offers a rigorous interpretation of a specific case, we acknowledge the limitations of its qualitative design in terms of generalizability. Nevertheless, our aim was to produce a deep, context-sensitive reading of discursive processes amid political crisis and media acceleration. We recommend that future research adopt mixed-method or longitudinal designs to assess the public impact of these strategies and their implications for democratic engagement.

4.6. Comparative Dimension

Although this study centers on Ecuador, placing Daniel Noboa’s crisis communication strategies within a broader global framework enhances the significance of the findings. The use of multimodal, emotionally resonant social media messaging, anchored in personalization, symbolism, and spectacle, is part of a widespread trend in digital political communication during times of crisis.

For example, the European Union utilized Twitter strategically during the COVID-19 pandemic to manage its reputation and assert a unified, values-based response amid uncertainty. Through computational and qualitative methods, () demonstrates that the EU’s digital diplomacy evolved from hierarchical messaging to more original and consistent crisis narratives, reinforcing joint identity and institutional credibility.

Simultaneously, in crisis contexts, misinformation and user fatigue compromise the effectiveness of digital messaging. A recent study reveals that fatigue from social media overload not only reduces engagement but also fosters misinformation spread, particularly among users with lower cognitive ability and higher narcissistic traits (). () further confirm these dynamics, showing that fatigue and disengagement—combined with imbalance between user-generated and official content—erode trust in platforms as reliable crisis communication tools.

By aligning Noboa’s “grammar of war” with these global patterns—where leaders enact personalized, visually compelling narratives in turbulent times—this comparative lens emphasizes both the transnational features of crisis communication and the shared pitfalls of misinformation, fatigue, and diminishing public trust.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A.M.; Methodology, N.A.M. and M.L.-P.; Validation, M.L.-P.; Formal analysis, N.A.M., M.L.-P. and T.S.P.; Investigation, M.L.-P., C.R.-M. and T.S.P.; Data curation, N.A.M., C.R.-M. and T.S.P.; Writing—original draft, N.A.M., M.L.-P. and T.S.P.; Writing—review & editing, N.A.M., C.R.-M. and T.S.P.; Funding acquisition, M.L.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, grant number QIPR0049-IBYA103261070.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abid, Aman, Sanjit Roy, Jennifer Lees-Marshment, Bidit L. Dey, Syed S. Muhammad, and Satish Kumar. 2023. Political social media marketing: A systematic literature review and agenda for future research. Electronic Commerce Research 25: 741–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Saifuddin, and Muhammad E. Rasul. 2023. Examining the association between social media fatigue, cognitive ability, narcissism, and misinformation sharing: Cross-national evidence from eight countries. Scientific Reports 13: 15416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balandier, Georges. 1997. El poder en escenas. De la representación del poder al poder de la representación. Barcelona: Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Barberá, Pablo. 2020. Social Media, Echo Chambers, and Political Polarization. In Social Media and Democracy Chapter. Edited by Nathaniel Persily and Joshua A. Tucker. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 34–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier, Gwen, and David Machin. 2020. Critical discourse analysis and the challenges and opportunities of social media. In Critical Discourse Studies and/in Communication: Theories, Methodologies, and Pedagogies at the Intersections, 1st ed. Edited by Susana Martínez Guillem and Christopher Toula. Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouvier, Gwen, and Lyndon C. S. Way. 2021. Revealing the politics in “soft”, everyday uses of social media: The challenge for critical discourse studies. Social Semiotics 31: 345–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climent, José, and Charo Toscano. 2024. Modelo de inbound marketing como estrategia de comunicación política y de gobierno: Atraer e involucrar a la ciudadanía. Cuadernos de Gobierno y Administración Pública 11: e92831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, R. 2008. Harry G. Frankfurt. 2005. On bullshit. Sobre la manipulación de la verdad y Sobre la verdad. Revista Cultura Económica 26: 78–79. Available online: https://erevistas.uca.edu.ar/index.php/CECON/article/view/2605 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Cruz, Manuel J. 2024. A narrativa populista do Chega na Assembleia da República. Coimbra: Universidade de Coimbra. [Google Scholar]

- Debord, Guy. 2007. La sociedad del espectáculo. Berlin: Kolectivo Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Divita, David. 2022. The Gendered Semiotics of Far-Right Populism on Instagram: A Case from Spain. Discourse & Society 34: 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-García, Ricardo, João P. Baptista, Concha Pérez-Curiel, and Daniela E. M. Fonseca. 2025. From Emotion to Virality: The Use of Social Media in the Populism of Chega and VOX. Social Sciences 14: 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, Norman. 2003. Analysing Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research. Available online: https://howardaudio.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/n-fairclough-analysing-discourse.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Feenberg, Andrew. 2000. Introducción. El parlamento de las cosas. In Critical Theory of Technology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 2002. Vigilar y castigar: Nacimiento de la prisión. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Frankfurt, Harry. 2005. On Bullshit. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes, José, and Magnolia Rosado. 2008. La construcción social del miedo y la conformación de imaginarios urbanos maléficos. Iztapalapa: Revista de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades 64: 93–115. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/393/39348722005.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Gensollen, Mario. 2007. Harry G. Frankfurt, On bullshit. Sobre la manipulación de la verdad. Euphyía 1: 146–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, Adam F. 2024. Bullshit in Politics Pays. Episteme 21: 1002–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Mario. 2025. Ecuador cerró 2024 con la Segunda Peor Tasa de MUERTES violentas de su Historia, Pese a una Importante Reducción. Available online: https://www.primicias.ec/seguridad/ecuador-2024-tasa-muertes-violendas-segunda-peor-historia-87118/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Grusell, Marie, and Lars Nord. 2020. Not so Intimate Instagram: Images of Swedish Political Party Leaders in the 2018 National Election Campaign. Journal of Political Marketing 22: 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Coba, Liliana, and Carlos Rodríguez-Pérez. 2023. Estrategias de posverdad y desinformación en las elecciones presidenciales colombianas 2022. Revista De Comunicación 22: 225–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidegger, Martin. 2021. La pregunta por la técnica. Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Kharel, Aswasthama B. 2024. Cyber-Politics: Social Media’s Influence on Political Mobilization. Journal of Political Science 24: 103–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krywalski, Joanna, Maria T. Borges, and Flávio Tiago. 2025. Social media challenges: Fatigue, misinformation and user disengagement. Management Decision. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubin, Emily, and Christian von Sikorski. 2021. The role of (social) media in political polarization: A systematic review. Annals of the International Communication Association 45: 188–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, George. 2004. Don’t Think of an Elephant! Know Your Values and Frame the Debate. London: Chelsea Green Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lotman, Iuri. 2002. El símbolo en el sistema de la cultura. Forma y Función 15: 89–101. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/219/21901505.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- López, Marco, and Andrea Carrillo. 2024. Cartografía de consumo de medios en Ecuador: De las mediaciones e hipermediaciones a una sociedad ultramediada. Palabra Clave 27: e2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machin, David, and Andrea Mayr. 2023. Conclusion: Multimodal critical discourse analysis and its discontents. In Conclusion: Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis and Its Discontents, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, Alison, and Ibrar Bhatt. 2020. Lies, bullshit and fake news: Some epistemological concerns. Postdigital Science and Education 2: 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Fresneda, Humberto. 2010. Estrategias persuasivas en la comunicación. Comunicación y Hombre 6: 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moral, Pablo. 2023. Restoring reputation through digital diplomacy: The European Union’s strategic narratives on Twitter during the COVID-19 pandemic. Communication & Society 36: 241–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naya, Albert. 2025. Daniel Noboa, el influencer millonario que a lomos del ‘ave fénix’ seguirá al mando de Ecuador. France 24. Available online: https://www.france24.com/es/am%C3%A9rica-latina/20250412-daniel-noboa-el-influencer-millonario-que-a-lomos-del-ave-f%C3%A9nix-busca-seguir-al-mando-de-ecuador (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Orejuela, Sandra. 2009. Personalización política: La imagen del político como estrategia electoral. Revista de Comunicación 8: 60–83. Available online: https://revistadecomunicacion.com/article/view/2797 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Ortega Jarrín, Maria G., and Marta Escribano. 2024. Análisis de la comunicación audiovisual de la presidencia de Ecuador en TikTok durante los primeros meses del Gobierno de Daniel Noboa. Revista Más Poder Local 57: 101–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanassopoulos, Stylianos, and Iliana Giannouli. 2025. Political Communication in the Age of Platforms. Encyclopedia 5: 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posligua, Isabel, and Marlon Ramírez. 2024. Comunicación política y redes sociales. La influencia en la opinión pública de la comunidad TikTok. Ñawi: Arte, Diseño y Comunicación 8: 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, Heldér. 2024. Social media and the rise of radical right populism in Portugal: The communicative strategies of André Ventura on X in the 2022 elections. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 11: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintanilla, Pablo. 2007. Frankfurt, Harry G: Sobre la manipulación de la verdad. Discusiones Filosóficas 8: 316–29. Available online: http://scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0124-61272007000200018 (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Rivera Magos, Sergio, and Gabriela González Pureco. 2024. Populismo, desinformación y polarización política en la comunicación en redes sociales de los presidentes populistas latinoamericanos. Revista Mexicana de Opinión Pública 19: 79–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríspolo, Florencia. 2020. El campo de la comunicación política: El lugar de la comunicación de gobierno. POSTData: Revista de Reflexión y Análisis Político 25: 73–98. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/522/52272877005/html/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Sayago, Sebastián. 2022. Encadenamientos argumentativos en los textos noticiosos. Forma y Función 35: 93–120. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=8459717 (accessed on 12 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Sengul, Kurt. 2025. How are far-right online communities using X/Twitter Spaces? Discourse, communication, sharing. Discourse, Context & Media 65: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, Yeny, and Wilson López. 2008. Estrategias de comunicación militar y dinámicas mediáticas: ¿Dos lógicas contradictorias? Diversitas: Perspectivas en Psicología 4: 269–77. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/dpp/v4n2/v4n2a05.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Sibilia, Paula. 2013. El hombre postorgánico: Cuerpo, subjetividad y tecnologías digitales. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, Orlando. 2025. Publicidad Electoral en Redes, ¿qué Candidatos Invirtieron más en Facebook e Instagram? El Comercio. Available online: https://www.elcomercio.com/elecciones/publicidad-electoral-redes-candidatos-invierten-facebook-instagram/ (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Subekti, Dimas, and Dyah Mutiarin. 2023. Political Polarization in Social Media: A Meta-Analysis. Thammasat Review 26: 1–23. Available online: https://sc01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/tureview/article/view/240560 (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Valencia Londoño, Paula A., and Oscar I. Muñoz Giraldo. 2020. El framing (encuadre) de los líderes políticos durante el “Plebiscito por la Paz” en Colombia ¿Preparando la opinión pública para las elecciones 2018? Kepes 17: 193–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, Teun A. 2010. Discurso, conocimiento, poder y política. Hacia un análisis crítico epistémico del discurso. Revista de Investigación Lingüística 13: 167–215. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/ril/article/view/114181 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Wodak, Ruth. 2015. The Politics of Fear: What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Zegarra, Gonzalo. 2025. Violencia y seguridad en Ecuador: Un análisis de 2024. CNN en Español. Available online: https://cnnespanol.cnn.com/2025/02/06/latinoamerica/ecuador-violencia-seguridad-analisis-mano-dura-elecciones-orix (accessed on 6 February 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).