Abstract

Adolescent school victimization is a socially regulated experience, making it important to consider classroom-level compositional effects beyond individual characteristics. This study investigated the role of classroom characteristics, specifically, classroom socioeconomic status, average academic achievement, sex composition, immigrant density, and class size, in shaping students’ experiences of school victimization. Victimization was analyzed using a doubly latent multilevel modeling approach, which accounts for measurement error at both individual and classroom levels. The analyses drew on the entire Italian 10th grade student population (N = 254,177; Mage = 15.58 years; SDage = 0.74) and a considerable number of classrooms (N classrooms = 14,278), a sample size rarely available in the social sciences. Results indicated that classroom characteristics played a significant role in victimization, beyond individual-level variables. The most important factors were sex and prior academic achievement: classrooms with a higher proportion of male students experienced greater victimization, whereas higher average achievement was associated with lower victimization. A greater proportion of second-generation immigrant students, but not first-generation students, was also associated with increased victimization. By contrast, classroom socioeconomic status and class size were not significant predictors of victimization. In conclusion, these findings highlight the importance of considering the additional influence of the classroom context for school-based interventions, particularly the composition of classrooms in terms of sex and academic achievement, when addressing student victimization.

1. Introduction

Bullying victimization at school poses a serious risk for adolescents in Western countries (Cosma et al. 2020). Globally, according to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO 2019), almost one in three students (32%) has been bullied by their peers at school at least once in the past month. Furthermore, a recent cross-national study (Cosma et al. 2020) conducted in 37 countries has revealed different trends across Europe and North America.

According to Olweus, bullying victimization occurs when a student “is exposed, repeatedly and over time, to negative actions on the part of one or more other students” (Olweus 1994, p. 1173). These negative actions can take various forms, including physical aggression (direct bullying, e.g., being hit by a peer), verbal abuse (direct verbal bullying, e.g., being insulted by other students), or social exclusion (relational bullying), where a student is intentionally left out of a group (Olweus and Breivik 2014). During adolescence, aggression may become less overt, and other forms of bullying, such as social exclusion, as well as dynamics of peer contagion may also emerge (Dishion and Tipsord 2011).

Over the past few decades numerous studies have highlighted the harmful effects of bullying on young victims. They are more likely to experience a range of internalizing problems, including psychosomatic symptoms (Gini and Pozzoli 2013; Natvig et al. 2001; Zwierzynska et al. 2013). They also show elevated levels of anxiety and depression (Arseneault et al. 2010; Balluerka et al. 2023; Brunstein Klomek et al. 2019; Sweeting et al. 2006; Ttofi et al. 2011a), in addition to increased feelings of loneliness, social withdrawal, and avoidance behaviors (Coelho and Romão 2018; Espelage and Holt 2001). They are also at greater risk of suicidal ideation (Brunstein Klomek et al. 2019) and, in the most extreme cases, of suicide attempts (Kaltiala-Heino et al. 2000; Klomek et al. 2011; Rigby and Slee 1999; Yang et al. 2021). Victimization is also associated with a general sense of sadness, low self-esteem, and poor academic performance, which, in severe cases, can lead to dropout from school (Cornell et al. 2013; Hutson 2018; Nakamoto and Schwartz 2010; van Geel et al. 2018; Zych et al. 2015). Numerous studies have also documented that the negative consequences of bullying can persist in the long term (Arseneault et al. 2010; McDougall and Vaillancourt 2015; Ttofi et al. 2011a, 2011b; Walsh et al. 2013; Wolke et al. 2013; Wolke and Lereya 2015).

Bullying is a social phenomenon, which makes it essential to examine it within the broader social context in which it occurs (Alivernini 2013; Paletta et al. 2017; Williford et al. 2019). Although bullying can occur in various social settings, including sports, children’s residential care homes, and online environments (e.g., Cheever and Eisenberg 2022; Monks et al. 2009; Strohmeier and Gradinger 2022), schools remain particularly significant for adolescents. In these contexts, students spend a substantial amount of time developing social relationships, which may foster positive bonds such as friendships but may also expose them to bullying (Rambaran et al. 2020). Because the classroom often constitutes the immediate peer context in which bullying dynamics unfold, it is important to consider not only individual characteristics but also group-level factors (Salmivalli et al. 1998; Salmivalli 2010b). Previous studies have emphasized the importance of classroom effects, particularly with regard to class norms (see for example, Salmivalli 2010a), and social status (Wiertsema et al. 2023). However, less attention has been paid to class-level characteristics related to compositional factors (e.g., sex composition or classroom socioeconomic status) and to structural features such as class size.

In the present study, we examined several contextual characteristics related to classroom composition and size. Specifically, we considered the proportion of males in the classroom, immigrant density (including first- and second-generation students), classroom socioeconomic status (SES), average academic achievement, and class size. These characteristics reflect aspects of the classroom context that are relatively less malleable than individual-level variables, such as academic motivation or self-efficacy. However, understanding how such compositional characteristics influence the experiences of students is essential to identify structural conditions that may hinder or foster a safe and inclusive learning environment. Previous research has already emphasized the role of classroom context in shaping psychological well-being (e.g., Alivernini et al. 2019a) and intergroup dynamics such as prejudice (Albarello et al. 2023). Nonetheless, studies focusing on classroom-level factors remain relatively scarce, and the findings to date are often mixed.

In the next section, we provide a brief review of the literature that examines the relationship between victimization and classroom composition and class size.

1.1. Victimization and Classroom Characteristics

1.1.1. Sex Composition

While several studies have consistently shown that, on average, male students are more frequently involved in bullying episodes than their female counterparts, including as victims (Bokhove et al. 2022; Bouffard and Koeppel 2017; Cook et al. 2010; Seals and Young 2003; Whitney and Smith 1993), findings remain mixed with regard to compositional effects. Some studies have reported a non-significant relationship between bullying and victimization and the classroom’s sex composition (Garandeau et al. 2014; Saarento et al. 2013), whereas others suggest that a higher proportion of male students within a class is associated with increased levels of bullying victimization (Coelho and Sousa 2018; Khoury-Kassabri et al. 2004; Thornberg et al. 2017). For example, Thornberg et al. (2017) found that classrooms with a higher number of boys reported higher levels of victimization, possibly because male students are more likely than female students to engage in bullying behaviors.

1.1.2. Classroom Socioeconomic Status (SES)

Schools located in disadvantaged areas, or those with a high proportion of students of lower socioeconomic backgrounds, tend to report a higher incidence of bullying-related issues (Q’Moore et al. 1997; Whitney and Smith 1993). Wolke et al. (2001) identified a significant, albeit weak, relationship between greater social disadvantage in schools and victimization. Similarly, Khoury-Kassabri et al. (2004) found a significant association between being a victim of bullying and coming from a lower socioeconomic background. The systematic review by Azeredo et al. (2015) showed that contexts marked by a greater income inequalities were associated with an increased risk of bullying. Other studies have suggested that a higher prevalence of students from very low socioeconomic backgrounds may contribute to the development of an unsafe school climate, which in turn is associated with increased levels of bullying and victimization (Bradshaw et al. 2009; Malecki et al. 2020). However, some researchers argue that it is not poverty per se, but rather perceived economic disparities between students that can drive bullying behaviors in school settings (Attree 2006; Chaux et al. 2009). In contrast, other studies have not found a statistically significant relationship between socioeconomic background and bullying-related issues (Ma 2002; Olweus 1994; Thornberg et al. 2022).

1.1.3. Immigrant Composition

While some research indicates that immigrant students are at higher risk of being victims of aggressive behaviors compared to their non-immigrant peers (Alivernini et al. 2019b; Bjereld et al. 2015; Fu et al. 2013; Graham and Juvonen 2002; Pistella et al. 2020; Pottie et al. 2015; Strohmeier et al. 2011), regardless of whether they are first- or second-generation (Walsh et al. 2016), the role of compositional effects remains unclear. Some research has reported a significant, albeit modest, association between higher immigrant density and increased levels of physical fighting and bullying perpetration among both immigrant and non-immigrant adolescents (Walsh et al. 2016). However, other studies have found no significant relationship between the number of immigrant students in a classroom or school and the risk of bullying victimization (Basilici et al. 2022). For instance, evidence suggests that it is not the proportion of immigrant students per se, but rather the classroom climate and levels of support that influence bullying victimization (Dimitrova 2017).

1.1.4. Classroom Academic Achievement

Previous research has examined student academic performance both as a potential consequence of bullying and as a predictor of involvement in such episodes (Card and Hodges 2008). In addition to individual-level effects, it has also been shown that the academic level of the peer group is a relevant contextual factor in understanding bullying dynamics. For example, Garandeau et al. (2011) found that aggressive students were more disliked in classrooms where academic achievement was highly valued, suggesting that a learning-oriented classroom climate may discourage aggressive behaviors by reducing their social rewards. Similarly, classrooms characterized by overall lower academic performance appear to be at higher risk for antisocial behaviors among students (Junger-Tas et al. 2010). Finally, schools with a high proportion of students who have repeated a grade—often a proxy of low academic achievement—tend to report increased levels of victimization (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD 2017).

1.1.5. Class Size

Previous studies have produced mixed findings on the relationship between class size and bullying behaviors (Menesini and Salmivalli 2017; Garandeau et al. 2019). Some studies have found a non-significant relationship between class size and bullying (Coelho and Sousa 2018; Wang and Chen 2023; Whitney and Smith 1993). On the contrary, other research has shown a positive association between victimization and larger class sizes (Garandeau et al. 2014). For example, in nationally representative study by Khoury-Kassabri et al. (2004) of more than 10,000 students, higher levels of victimization were observed in larger classrooms. On the contrary, several studies suggest the opposite, namely, that smaller class sizes may be associated with increased levels of aggressive behaviors. Q’Moore et al. (1997) reported significantly higher levels of bullying in smaller secondary school classrooms. Similarly, Garandeau et al. (2014) found that bullying was less prevalent in larger classes. A subsequent study by Garandeau et al. (2019) using peer-reported measures confirmed a similar pattern for both bullying and victimization. Consistent with these findings, Saarento et al. (2013) reported higher levels of peer-reported victimization in smaller classrooms. According to the authors, this may be explained by the increased visibility of bullying episodes in smaller settings, which makes it easier for students to identify who among their peers is being targeted.

1.2. Objectives

Acknowledging the importance of considering the social context in which bullying occurs (Hong and Espelage 2012; Williford et al. 2019), and drawing on previous evidence consistently showing that peer victimization varies significantly between classrooms (Saarento et al. 2015; Stefanek et al. 2011; Thornberg et al. 2022; Thornberg et al. 2024), the present study aims to investigate the role of classroom composition and class size in students’ experiences of bullying victimization at school. We focused on the classroom context because studies examining classroom-level factors remain relatively limited (Thornberg et al. 2024) and have yielded mixed results. Moreover, prior research has indicated that differences in bullying between classrooms are equal to, or even greater than, those between schools (Kloo 2025; Thornberg et al. 2024).

This study analyzed victimization using a doubly latent multilevel modeling approach with cross-level measurement invariance (Lüdtke et al. 2011; Marsh et al. 2012), thereby accounting for potential measurement errors at both levels. In addition, in our model we have included several classroom characteristics related to compositional variables (i.e., classroom socioeconomic and academic achievement levels, male student proportion, immigrant density) and class size, drawing on a considerable number of classrooms (N classrooms = 14,278). Such a large sample is rarely available in social sciences and allows for highly accurate estimates (Núñez et al. 2013), for a recent review see (Asampana Asosega et al. 2024).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The data analyzed in this study were drawn from a large-scale Italian national assessment of learning conducted by the National Institute for the Evaluation of the Education System (INVALSI). This assessment, based on a cross-sectional design, covered the entire population of 10th-grade students in Italy. In each upper secondary school, all students enrolled in second-year classes (equivalent to 10th grade) participated by completing standardized paper and pencil tests of reading comprehension in Italian and mathematical skills. In addition, students filled out a paper and pencil questionnaire that included the victimization scale and demographic information, which are the focus of the present study.

2.2. Sample and Procedures

Data are based on the population of Italian 10th-grade students (N = 254,177; Mage = 15.58 years; SDage = 0.74; N classrooms = 14,278, average class size = 21.2 students) who participated in the national assessment of learning conducted by INVALSI in 2015.

In the Italian educational system, the 10th grade corresponds to the second year of upper secondary education (ISCED 3), typically attended by students aged 15–16 years old. Upper secondary schools in Italy are structured into three different paths. The general education path (i.e., “licei” in Italian) prepares students to higher-level studies and to the labor world by providing broad knowledge, key competences, and cultural instruments for developing their own critical point of view. Technical education (i.e., “istituti tecnici”), provides students with scientific and technological competences in the technological and economic professional sectors. Vocational education (i.e., “istituti professionali”), provides technical and vocational general background in the sectors of services, industry and handicraft, to facilitate access to specific occupations. In Italy, as in many other countries, upper secondary classrooms are stable groups of approximately 20–30 students (Decreto del Presidente della Repubblica 20 marzo 2009, n. 81 2009) who spend most of their school time together, attending all subjects throughout the academic year (with the exception of optional subjects or extracurricular activities). Subject-specific teachers rotate between classrooms, while the student groups remain largely unchanged from grade 9 to grade 13.

All participants completed the anonymous questionnaires in class during the first part of a typical school day. Before starting, students received a standardized introduction to the survey that explained its purpose and provided instructions on how to complete the questionnaire. The evaluation adhered to the ethical guidelines of INVALSI (2015), which reviewed and approved the evaluation process. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the National Institute for the Evaluation of the Education and Training System (INVALSI). Data collection was approved by the Ministry of Education, University and Research, with Directive No. 85 of 12 October 2012, ensuring that the study adheres to both national and international guidelines. Each school was responsible for managing informed consent and obtaining parental permission according to the national assessment protocol. Informed consent was obtained from all the parents of the students involved in the study. Data are available at https://serviziostatistico.invalsi.it/en/catalogo-dati/ (accessed on 24 September 2024).

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Victimization

Victimization was assessed using an adapted version of the scale developed by Roland and Idsøe (2001) which addresses general and specific victimization behaviors through four items (i.e., bullied/hassled by other students at school by being hit, kicked, or shoved). The students responded using a 4-point scale (1 = never; 2 = now and then; 3 = weekly; 4 = daily), with higher scores indicating a more frequent victimization at school. The scale has demonstrated good psychometric properties in previous studies (Alivernini et al. 2019b; Bianchi et al. 2021), and its reliability was also confirmed in the present study (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76; Omega coefficient = 0.79).

2.3.2. Sex

Sex was assessed via self-report and subsequently categorized into two groups: 0 for female and 1 for male.

2.3.3. Immigrant Background

Following the OECD classification (OECD 2014), the immigrant background was coded into three categories. Native students were defined as those born in Italy and with at least one parent also born in Italy. First-generation immigrants included students who were defined as foreign-born and with parents born abroad. Second-generation immigrants referred to those born in Italy and with parents born abroad. In this study, the immigrant background was coded by using two dummy variables (0/1): one indicating first-generation immigrants and the other indicating second-generation immigrants. Native students served as the reference category.

2.3.4. Socioeconomic Status (SES)

Socioeconomic status (SES) is a composite score based on four indicators. The first indicator, “parents’ highest level of education”, was assessed through students’ reports of their parents’ educational attainment, categorized according to the six levels of the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) (UNESCO 2012). This indicator reflects the higher level of schooling attained by students’ parents. The second indicator, “parents’ highest occupational status”, was derived from students’ reports of their parents’ occupations (e.g., manager, teacher, clerk), which were coded into six groups ranked by occupational status. This indicator reflects the higher occupational status of students’ parents. The third indicator, “home literacy resources”, was measured by students’ reports of the number of books available at home, ranging from “0 to 10 books” to “more than 500 books”. Lastly, the “home possessions” indicator was based on students’ reports of household items and facilities, such as personal computers, internet access, and desks for homework. A principal Component Analysis (PCA) was conducted on these indicators, and the factor scores from the first component were used as SES scores. Previous studies have shown that the first component explains more than 56% of the total variance (Campodifiori et al. 2010). Based on this procedure, SES was computed as a standardized index, with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.

2.3.5. Prior Academic Achievement

Prior academic achievement was assessed using the final grades of the students from the national state examination taken at the end of the lower secondary school (grade 8) in Italy. The grading scale ranged from 6 to 10, with honors being the highest distinction. At the time of the study, the state examination consisted of four written tests (in Italian, mathematics and two foreign languages), standardized assessments of Italian comprehension and mathematical skills, as well as an oral exam covering all subjects.

2.3.6. Class Size

The class size was defined as the total number of students enrolled in each class during the school year in which the study was conducted. This information was obtained from the official school records provided by the participating schools. The reported numbers included all enrolled students, even those who, for various reasons, did not participate in the study. In the present study, the average class size is 21.2.

2.4. Data Analysis

We first conducted a multilevel confirmatory factor analysis (MCFA) to assess the factor structure of the victimization scale. A one-factor model was specified at both the within-class level (L1) and the between-class level (L2). All factor loadings were constrained to be equal across levels (Mehta and Neale 2005). Intraclass correlation (ICC) was also calculated.

Subsequently, we implemented a multilevel structural equation model. At L1, the following variables were included: sex of the student, immigrant background (first and second generations), SES, and prior academic achievement. SES and prior achievement were centered at their grand mean. Therefore, the estimates of SES and prior achievement aggregated at the classroom level were interpretable as compositional effects (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002; Marsh et al. 2012). Compositional effects refer to the influence of an L2 variable on an L2 outcome, after accounting for the effect of the corresponding L1 variable on the L1 outcome. Class size was also included as a continuous predictor. The stable structure of the classrooms in the Italian school system allows for consistent peer groups across school years and facilitates the analysis of classroom-level effects. School type (Liceo, Technical Institute, or Vocational Institute) was included as a class-level control variable to account for potential influences and to obtain results net of these effects.

Analyses were conducted using Mplus 8 software version 1.6(1) (Muthén and Muthén 2017) with the Robust Maximum Likelihood (MLR) estimator, which is robust to nonnormality and accounts for nested data structures. Model fit was assessed using the MLR chi-square test statistic and multiple fit indices (comparative fit index [CFI], root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] and standardized root mean square residual [SRMR]), referring to conventional criteria for an acceptable model fit (Hu and Bentler 1999).

Victimization was analyzed using a doubly latent approach with cross-level measurement invariance (Lüdtke et al. 2011; Marsh et al. 2012). In this approach, the construct is modeled as latent at the item level, and a latent aggregation of individual student responses is used to form indicators at classroom-level (Televantou et al. 2015). Employing latent measurement models at both levels allowed us to account for potential measurement errors.

Missing data, which ranged from 1.5% to 4.7%, were handled using the Full Information Maximum Likelihood method implemented in Mplus.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the frequency table for the victimization items.

Table 1.

Frequencies (%) for the four items of the victimization scale.

The MCFA results confirmed the one-factor structure for victimization: CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.03; SRMR = 0.013. Intraclass correlation (ICC) for victimization was 0.087, indicating that 8.7% of the variance in victimization is attributable to differences between classes.

Table 2 shows the standardized factor loadings for this model at both the within- and between-levels. At the within-level, the factor loadings of the items range from 0.50 to 0.81. The items load strongly onto the single factor at the between-level, ranging from 0.59 (“Bullied/hassled by other students at school by being hit, kicked, or shoved”) to 0.99 (“Bullied/hassled by other students at school”).

Table 2.

Standardized factor loadings of victimization scale items.

The fit statistics of the tested model were adequate (CFI = 0.953; RMSEA = 0.028; SRMR = 0.023; SRMRbetween = 0.104). At the student level (L1), the model explained 1.5% of the total variance in victimization (see Appendix A). All predictors showed significant effects: male students and students with an immigrant background (both first- and second-generation) reported higher levels of victimization, whereas students with higher socioeconomic status (SES) and better prior academic achievement reported lower levels of victimization than their peers.

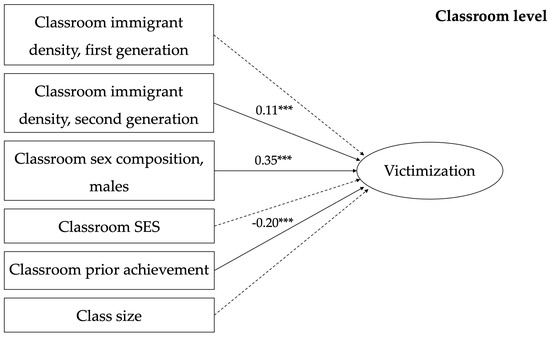

The results of the multilevel SEM analysis at the classroom level are shown in Figure 1. The findings revealed that a higher proportion of male students in the class was associated with higher levels of victimization (β = 0.35, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001). Similarly, classrooms with a higher percentage of second-generation immigrant students (β = 0.11, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001), but not first-generation students (β = 0.01, SE = 0.02, p = 0.34), reported higher levels of victimization. In contrast, classroom academic achievement was negatively associated with victimization rates (β = −0.20, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001), after controlling for students’ individual achievement: students with similar academic performance tended to report less victimization in classrooms with higher average achievement. Classroom SES (β = −0.02, SE = 0.02, p = 0.30) and class size (β = 0.03, SE = 0.01, p = 0.06) were not significantly associated with victimization. At the classroom level, the model explained 31.7% of the variance in victimization.

Figure 1.

Multilevel SEM results. Note. Standardized coefficients. *** p < 0.001. The dashed lines represent statistically non-significant effects. At the classroom level, the coefficients and explained variance in the model account for the type of school attended by the students (general, technical, and vocational upper secondary schools). Intraclass correlation (ICC) = 8.7%.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the impact of classroom composition and size on bullying victimization in a population of 254,177 Italian 10th grade students. As pointed out in previous studies, bullying is a peer-group phenomenon (Williford and Zinn 2018) and classroom characteristics can influence group-level experiences. Our results are in line with this theoretical framework, as they indicated that classroom composition played a key role in bullying dynamics. Specifically, sex composition emerged as the most important factor, followed by classroom academic performance. Furthermore, a higher proportion of second-generation immigrant students in the classroom, but not first-generation immigrants, was associated with a slight but statistically significant increase in victimization. In contrast, neither socioeconomic composition nor class size showed a significant effect on bullying victimization.

The results concerning sex are consistent with previous studies that indicate that classrooms with a higher proportion of male students tend to exhibit higher levels of bullying victimization (Coelho and Sousa 2018; Khoury-Kassabri et al. 2004; Thornberg et al. 2017). A male-dominated classroom environment can contribute to a more aggressive school climate (Khoury-Kassabri et al. 2004), characterized not only by a higher prevalence of perpetrators but also by an increased number of male victims. Given the relationship between sex and the type of bullying, where boys are more often involved in physical forms and girls in relational or verbal forms of aggression (Menesini and Salmivalli 2017), it is crucial to consider not only the prevalence of male students, but also how classroom norms may shape these behaviors. For example, when the majority of students are male, physical forms of aggression may be more normalized, and even rewarded as a marker of social dominance, reinforcing peer group dynamics that sustain victimization (Rosen and Nofziger 2019). Conversely, in more gender-balanced classrooms, alternative pathways to recognition and status may weaken the link between male prevalence and bullying, reducing the likelihood of persistent victimization. These mechanisms help explain why sex composition emerges as an important contextual factor and highlight the need for interventions that target classroom climate and peer norms rather than individual students alone.

Regarding classrooms’ prior academic achievement, our findings build on previous research showing that students with lower academic performance are more likely to be victims of bullying. Academic ability may shape peer group perceptions, which could lead to the exclusion or mistreatment of students who underperform (Cavicchiolo et al. 2022; Plenty and Jonsson 2017; Schwartz et al. 2002). The present study extends these findings to the classroom level: regardless of individual achievement, students experience less victimization in higher-performing classrooms. This suggests that the overall academic performance of the class not only influences students’ well-being and academic self-concept (Alivernini et al. 2020; Belfi et al. 2012; Cavicchiolo et al. 2025), but also acts as a protective factor against negative school experiences such as victimization. Previous studies have highlighted that a learning-oriented classroom climate may discourage aggressive behaviors by reducing their social rewards (Garandeau et al. 2011). Garandeau et al. (2011) found that in classrooms where academic achievement was highly valued, aggressive students were more disliked, indicating that a learning-oriented classroom climate may discourage aggressive behaviors by reducing their social rewards. The importance of classroom-level academic performance is particularly salient in educational contexts such as Italy, where classrooms consist of stable groups of students and a substantial share of the variability in academic outcomes is attributable to the class or school attended (OECD 2023). In such settings, differences between classes can be considerable and persist across school years, potentially creating classroom environments in which students are at greater risk of victimization.

As regards immigrant density, our findings showed a significant positive association between the proportion of second-generation immigrant students and victimization, whereas the concentration of first-generation students showed no effect. This pattern is in line with the so-called “immigrant paradox” (Coll and Marks 2012; Suárez-Orozco et al. 2018). According to this phenomenon, second-generation youth exhibit less optimal school adjustment compared to their first-generation peers (Marks et al. 2014). This pattern appears to be paradoxical, as one might expect the opposite: first-generation students have less time to adjust to the difficulties of schooling in a new country and often possess lower proficiency in the host country’s language than later generations (Cavicchiolo et al. 2020, 2023; Diemer et al. 2014). One possible explanation is that, unlike first-generation students, second-generation students do not have the advantage of a dual frame of reference (i.e., one from the family of origin and one from the host country) (Suárez-Orozco et al. 2018) that might protect them from integration challenges. Our results show that when a high number of second-generation students are in the same classroom, these challenges may intensify, creating peer dynamics that might foster increased victimization.

In the present study, classroom SES was not significantly associated with victimization, consistent with previous findings highlighting the limited impact of group-level SES on bullying (Bokhove et al. 2022). One possible explanation relates to the levels of equity in education, which reflect the extent to which the school system provides learning opportunities to all students (OECD 2018). According to the OECD (2018), equity levels and socioeconomic segregation in schools vary across countries, with Italy being among those with the highest levels of equity and relatively low segregation (OECD 2018). This suggests that disadvantaged students in our sample might attend schools with resources and opportunities comparable to those of their more advantaged peers, potentially mitigating the effects of group-level SES on bullying. However, the absence of significant classroom SES effects may also reflect the complexity of group-level mediating mechanisms. Previous research has suggested that classroom SES can influence bullying behavior primarily through more proximal factors, such as teacher-student relationship quality, school climate, and teachers’ attitudes toward bullying (Thornberg et al. 2024).

Regarding class size, although larger classrooms are often assumed to be associated with more bullying episodes, empirical evidence supporting this claim is limited (Saarento et al. 2015). Consistent with this, in our study, class size was not significantly related to self-reported victimization. One possible explanation is that class size may influence victimization indirectly. Similarly to classroom SES, class size may operate through indirect pathways rather than direct mechanisms. Specifically, class size may affect victimization through its impact on classroom management, teacher style, and peer group dynamics. These factors may be more proximal predictors of victimization than structural characteristics like class size.

5. Limitations

Bullying victimization is a socially regulated experience, and the present study sheds new light on the role of classroom characteristics, which represent the most proximal and prominent environment for adolescents. Despite its strengths, this study is not without limitations. The variables considered referred to group characteristics present at the beginning of socialization processes (i.e., entry into high school), but longitudinal data would be needed to provide stronger evidence of causal relationships.

The study included the entire population of 10th grade students and a very large number of classes, in a context where classroom structures remain relatively stable throughout adolescence. While this enhances the robustness of the findings, it may also limit their generalizability to other age groups.

One of the strengths of our study, namely the use of the entire population, could also be regarded as a potential limitation, given the increased likelihood of detecting statistically significant results in very large samples. However, the fact that not all tested relationships were significant suggests that statistical power alone does not account for the observed findings.

Another limitation concerns the measurement of victimization, which was assessed through a scale with good psychometric properties but based solely on student self-reports. These may be influenced by biases such as social desirability. Future studies could strengthen the assessment by incorporating multiple informants (e.g., peers, teachers, or parents) to capture a broader perspective on bullying-related behavior (Casper et al. 2015).

Finally, the study was conducted within the Italian educational system, whose distinctive features may shape peer dynamics and victimization processes. While our findings may offer useful insights into educational systems with similar characteristics, caution is warranted when generalizing them to countries with different school structures.

6. Conclusions

This study highlights the important role of classroom context in student victimization. Specifically, when planning school-based monitoring and prevention programs, classroom composition in terms of sex and academic achievement should be carefully considered. Classrooms represent one of the most significant social contexts for adolescents, where they develop and sustain both positive and negative interactions with their peers. Therefore, intervention strategies aimed at promoting safer and more supportive relational environments should take into account the characteristics of the class attended by students, in addition to their individual characteristics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.C. and F.A.; methodology, E.C., F.A. and S.M.; formal analysis, E.C.; investigation, S.M. and I.D.L.; data curation, S.M., I.D.L. and L.G.; writing—original draft preparation, E.C.; writing—review and editing, G.R., L.G., M.Z., J.D., I.D.L., P.D., T.P., A.C., F.L., F.A. and S.M.; visualization, G.R., M.Z. and J.D.; supervision, S.M. and F.A.; project administration, F.A.; funding acquisition, F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by Sapienza University of Rome, “Economically deprived and immigrant youth: the protective role of psychological resources and educational context”, project number RD12318A949D7606.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the National Institute for the Evaluation of the Education and Training System (INVALSI). Data collection was approved by the Ministry of Education, University and Research, with Directive No. 85 of 12 October 2012, ensuring that the study adheres to both national and international guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Each school dealt with the process of informed consent and parental permission according to a National assessment protocol provided by the National Institute for the Evaluation of the Education and Training System (INVALSI). Informed consent was obtained from all the parents of the students involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here upon free registration: INVALSI—Statistical Office https://serviziostatistico.invalsi.it/catalogo-dati (accessed on 24 September 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Estimates and standard errors from multilevel analyses. Student level (L1).

Table A1.

Estimates and standard errors from multilevel analyses. Student level (L1).

| Student Level (L1) | Estimate | SE |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, male | 0.03 *** | 0.003 |

| Immigrant background, first generation | 0.04 *** | 0.003 |

| Immigrant background, second generation | 0.09 *** | 0.003 |

| SES | −0.06 *** | 0.003 |

| Prior academic achievement | −0.01 ** | 0.003 |

Note. Standardized estimates. SE = standard error; SES = socioeconomic status. ** p < 0.01. *** p < 0.001.

References

- Albarello, Flavia, Sara Manganelli, Elisa Cavicchiolo, Fabio Lucidi, Andrea Chirico, and Fabio Alivernini. 2023. Addressing Adolescents’ Prejudice Toward Immigrants: The Role of the Classroom Context. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 52: 951–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alivernini, Fabio. 2013. An Exploration of the Gap Between Highest and Lowest Ability Readers Across 20 Countries. Educational Studies 39: 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alivernini, Fabio, Elisa Cavicchiolo, Laura Girelli, Fabio Lucidi, Valeria Biasi, Luigi Leone, Mauro Cozzolino, and Sara Manganelli. 2019a. Relationships Between Sociocultural Factors (Gender, Immigrant and Socioeconomic Background), Peer Relatedness and Positive Affect in Adolescents. Journal of Adolescence 76: 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alivernini, Fabio, Elisa Cavicchiolo, Sara Manganelli, Andrea Chirico, and Fabio Lucidi. 2020. Students’ Psychological Well-Being and Its Multilevel Relationship With Immigrant Background, Gender, Socioeconomic Status, Achievement, and Class Size. School Effectiveness and School Improvement 31: 172–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alivernini, Fabio, Sara Manganelli, Elisa Cavicchiolo, and Fabio Lucidi. 2019b. Measuring Bullying and Victimization Among Immigrant and Native Primary School Students: Evidence From Italy. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 37: 226–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arseneault, Louise, Lucy Bowes, and Sania Shakoor. 2010. Bullying Victimization in Youths and Mental Health Problems: ‘Much Ado About Nothing’. Psychological Medicine 40: 717–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asampana Asosega, Killian, Atinuke Olusola Adebanji, Eric Nimako Aidoo, and Ellis Owusu-Dabo. 2024. Application of Hierarchical/multilevel Models and Quality of Reporting (2010–2020): A Systematic Review. Scientific World Journal 2024: 4658333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attree, Pamela. 2006. The Social Costs of Child Poverty: A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Evidence. Children & Society 20: 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeredo, Catarina Machado, Ana Elisa Madalena Rinaldi, Claudia Leite de Moraes, Renata Bertazzi Levy, and Paulo Rossi Menezes. 2015. School Bullying: A Systematic Review of Contextual-Level Risk Factors in Observational Studies. Aggression and Violent Behavior 22: 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balluerka, Nekane, Jone Aliri, Olatz Goñi-Balentziaga, and Arantxa Gorostiaga. 2023. Asociación Entre El Bullying, La Ansiedad Y La Depresión En La Infancia Y La Adolescencia: El Efecto Mediador De La Autoestima. Revista de Psicodidáctica 28: 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basilici, Maria Chiara, Benedetta Emanuela Palladino, and Ersilia Menesini. 2022. Ethnic Diversity and Bullying in School: A Systematic Review. Aggression and Violent Behavior 65: 101762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfi, Barbara, Mieke Goos, Bieke De Fraine, and Jan Van Damme. 2012. The Effect of Class Composition By Gender and Ability on Secondary School Students’ School Well-Being and Academic Self-Concept: A Literature Review. Educational Research Review 7: 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, Dora, Elisa Cavicchiolo, Sara Manganelli, Fabio Lucidi, Laura Girelli, Mauro Cozzolino, Federica Galli, and Fabio Alivernini. 2021. Bullying and Victimization in Native and Immigrant Very-Low-income Adolescents in Italy: Disentangling the Roles of Peer Acceptance and Friendship. Child & Youth Care Forum 50: 1013–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjereld, Ylva, Kristian Daneback, and Max Petzold. 2015. Differences in Prevalence of Bullying Victimization Between Native and Immigrant Children in the Nordic Countries: A Parent-Reported Serial Cross-Sectional Study. Child Care Health Development 41: 593–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokhove, Christian, Daniel Muijs, and Christopher Downey. 2022. The Influence of School Climate and Achievement on Bullying: Comparative Evidence From International Large-Scale Assessment Data. Educational Research 64: 18–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouffard, Leana A., and Maria D. H. Koeppel. 2017. Sex Differences in the Health Risk Behavior Outcomes of Childhood Bullying Victimization. Victims & Offenders 12: 549–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, Catherine P, Anne L Sawyer, and Lindsey M O’Brennan. 2009. A Social Disorganization Perspective on Bullying-Related Attitudes and Behaviors: The Influence of School Context. American Journal of Community Psychology 43: 204–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunstein Klomek, Anat, Shira Barzilay, Alan Apter, Vladimir Carli, Christina W. Hoven, Marco Sarchiapone, Gergö Hadlaczky, Judit Balazs, Agnes Kereszteny, Romuald Brunner, and et al. 2019. Bi-Directional Longitudinal Associations Between Different Types of Bullying Victimization, Suicide Ideation/attempts, and Depression Among a Large Sample of European Adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 60: 209–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campodifiori, Emiliano, Elisabetta Figura, Monica Papini, and Roberto Ricci. 2010. Un Indicatore di Status Socio-Economico-Culturale Degli Allievi Della Quinta Primaria in Italia. Working Paper N 02/2010. Rome: INVALSI, pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Card, Noel A., and Ernest V. E. Hodges. 2008. Peer Victimization Among Schoolchildren: Correlations, Causes, Consequences, and Considerations in Assessment and Intervention. School Psychology Quarterly 23: 451–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, Deborah M., Diana J. Meter, and Noel A. Card. 2015. Addressing Measurement Issues Related to Bullying Involvement. School Psychology Review 44: 353–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavicchiolo, Elisa, Fabio Lucidi, Pierluigi Diotaiuti, Andrea Chirico, Federica Galli, Sara Manganelli, Monica D’Amico, Flavia Albarello, Laura Girelli, Mauro Cozzolino, and et al. 2022. Adolescents’ Characteristics and Peer Relationships in Class: A Population Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 8907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavicchiolo, Elisa, Sara Manganelli, Dora Bianchi, Valeria Biasi, Fabio Lucidi, Laura Girelli, Mauro Cozzolino, and Fabio Alivernini. 2023. Social Inclusion of Immigrant Children At School: The Impact of Group, Family and Individual Characteristics, and the Role of Proficiency in the National Language. International Journal of Inclusive Education 27: 146–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavicchiolo, Elisa, Sara Manganelli, Fabio Lucidi, and Fabio Alivernini. 2025. Measuring Emotional Well-Being At School Among Students With Different Characteristics: A Population Study. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. online first. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavicchiolo, Elisa, Sara Manganelli, Laura Girelli, Andrea Chirico, Fabio Lucidi, and Fabio Alivernini. 2020. Immigrant Children’s Proficiency in the Host Country Language is More Important Than Individual, Family and Peer Characteristics in Predicting Their Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 22: 1225–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaux, Enrique, Andrés Molano, and Paola Podlesky. 2009. Socio-Economic, Socio-Political and Socio-Emotional Variables Explaining School Bullying: A Country-Wide Multilevel Analysis. Aggressive Behavior 35: 520–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheever, Jamie, and Marla E. Eisenberg. 2022. Team Sports and Sexual Violence: Examining Perpetration By and Victimization of Adolescent Males and Females. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 37: NP400–NP422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, Vitor Alexandre, and Vanda Sousa. 2018. Class-Level Risk Factors for Bullying and Victimization in Portuguese Middle Schools. School Psychology International 39: 121–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, Vítor Alexandre, and Ana Maria Romão. 2018. The Relation Between Social Anxiety, Social Withdrawal and (Cyber)bullying Roles: A Multilevel Analysis. Computers in Human Behavior 86: 218–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll, Cynthia García Ed, and Amy Kerivan Ed Marks. 2012. The Immigrant Paradox in Children and Adolescents: Is Becoming American a Developmental Risk. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Clayton R., Kirk R. Williams, Nancy G. Guerra, Tia E. Kim, and Shelly Sadek. 2010. Predictors of Bullying and Victimization in Childhood and Adolescence: A Meta-Analytic Investigation. School Psychology Quarterly 25: 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, Dewey, Anne Gregory, Francis Huang, and Xitao Fan. 2013. Perceived Prevalence of Teasing and Bullying Predicts High School Dropout Rates. Journal of Educational Psychology 105: 138–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosma, Alina, Sophie D. Walsh, Kayleigh L. Chester, Mary Callaghan, Michal Molcho, Wendy Craig, and William Pickett. 2020. Bullying Victimization: Time Trends and the Overlap Between Traditional and Cyberbullying Across Countries in Europe and North America. International Journal of Public Health 65: 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decreto del Presidente della Repubblica 20 marzo 2009, n. 81. 2009. Norme per la riorganizzazione della rete scolastica e il razionale ed efficace utilizzo delle risorse umane della scuola, ai sensi dell’articolo 64, comma 4, del decreto-legge 25 giugno 2008, n. 112, convertito, con modificazioni, dalla legge 6 agosto 2008, n. 133. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana, n. 151, 2 luglio 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Diemer, Matthew A., Cheng-Hsien Li, Taveeshi Gupta, Nazli Uygun, Selcuk Sirin, and Lauren Rogers-Sirin. 2014. Pieces of the Immigrant Paradox Puzzle: Measurement, Level, and Predictive Differences in Precursors to Academic Achievement. Learning and Individual Differences 33: 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, Radosveta, ed. 2017. Is There a Paradox of Adaptation in Immigrant Children and Youth Across Europe? A Literature Review. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion, Thomas J., and Jessica M. Tipsord. 2011. Peer Contagion in Child and Adolescent Social and Emotional Development. Annual Review of Psychology 62: 189–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espelage, Dorothy L., and Melissa K. Holt. 2001. Bullying and Victimization During Early Adolescence. Journal of Emotional Abuse 2: 123–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Qiang, Kenneth C. Land, and Vicki L. Lamb. 2013. Bullying Victimization, Socioeconomic Status and Behavioral Characteristics of 12th Graders in the United States, 1989 to 2009: Repetitive Trends and Persistent Risk Differentials. Child Indicators Research 6: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garandeau, Claire F., Hai-Jeong Ahn, and Philip C. Rodkin. 2011. The Social Status of Aggressive Students Across Contexts: The Role of Classroom Status Hierarchy, Academic Achievement, and Grade. Developmental Psychology 47: 1699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garandeau, Claire F., Ihno A. Lee, and Christina Salmivalli. 2014. Inequality Matters: Classroom Status Hierarchy and Adolescents’ Bullying. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 43: 1123–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garandeau, Claire F., Takuya Yanagida, Marjolijn M. Vermande, Dagmar Strohmeier, and Christina Salmivalli. 2019. Classroom Size and the Prevalence of Bullying and Victimization: Testing Three Explanations for the Negative Association. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gini, Gianluca, and Tiziana Pozzoli. 2013. Bullied Children and Psychosomatic Problems: A Meta-Analysis. Pediatrics 132: 720–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, Sandra, and Jaana Juvonen. 2002. Ethnicity, Peer Harassment, and Adjustment in Middle School. The Journal of Early Adolescence 22: 173–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Jun Sung, and Dorothy L. Espelage. 2012. A Review of Research on Bullying and Peer Victimization in School: An Ecological System Analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior 17: 311–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Li-tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutson, Elizabeth. 2018. Integrative Review of Qualitative Research on the Emotional Experience of Bullying Victimization in Youth. The Journal of School Nursing 34: 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INVALSI. 2015. Rilevazioni Nazionali Degli Apprendimenti 2014–2015 Rapporto Tecnico. Rome: INVALSI. [Google Scholar]

- Junger-Tas, Josine, Ineke Haen Marshall, Dirk Enzmann, Martin Killias, Majone Steketee, and Beata Gruszczynska. 2010. Juvenile Delinquency in Europe and Beyond: Results of the Second International Self-Report Delinquency Study. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 227–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltiala-Heino, Riitta, Markku Rimpelä, Pauli Rantanen, and Anna Rimpelä. 2000. Bullying At School—An Indicator of Adolescents At Risk for Mental Disorders. Journal of Adolescence 23: 661–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury-Kassabri, Michal, Rina Benbenishty, Russell A. Astor, and Avital Zeira. 2004. The Contributions of Community, Family, and School Variables to Student Victimization. American Journal of Community Psychology 34: 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klomek, Anat Brunstein, Marjorie Kleinman, Elizabeth Altschuler, Frank Marrocco, Lia Amakawa, and Madelyn S Gould. 2011. High School Bullying as a Risk for Later Depression and Suicidality. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 41: 501–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloo, Mattias. 2025. Individual and Classroom-Level Associations of Within Classroom Friendships, Friendship Quality and a Sense of Peer Community on Bullying Victimization. Social Psychology of Education 28: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdtke, Oliver, Herbert W. Marsh, Alexander Robitzsch, and Ulrich Trautwein. 2011. A 2 × 2 Taxonomy of Multilevel Latent Contextual Models: Accuracy-Bias Trade-Offs in Full and Partial Error Correction Models. Psychological Methods 16: 444–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Xin. 2002. Bullying in Middle School: Individual and School Characteristics of Victims and Offenders. School Effectiveness and School Improvement 13: 63–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malecki, Christine K., Michelle K. Demaray, Thomas J. Smith, and Jonathan Emmons. 2020. Disability, Poverty, and Other Risk Factors Associated With Involvement in Bullying Behaviors. Journal of School Psychology 78: 115–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, Amy K., Kida Ejesi, and Cynthia García Coll. 2014. Understanding the U.s. Immigrant Paradox in Childhood and Adolescence. Child Development Perspectives 8: 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, Herbert W., Oliver Lüdtke, and Benjamin Nagengast. 2012. Classroom Climate and Contextual Effects: Conceptual and Methodological Issues in the Evaluation of Group-Level Effects. Educational Psychologist 47: 106–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, Patricia, and Tracy Vaillancourt. 2015. Long-Term Adult Outcomes of Peer Victimization in Childhood and Adolescence: Pathways to Adjustment and Maladjustment. American Psychologist 70: 300–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, Paras D., and Michael C. Neale. 2005. People Are Variables Too: Multilevel Structural Equations Modeling. Psychological Methods 10: 259–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menesini, Ersilia, and Christina Salmivalli. 2017. Bullying in Schools: The State of Knowledge and Effective Interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine 22 Suppl. S1: 240–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monks, Claire P., Peter K. Smith, Paul Naylor, Christine Barter, Jane L. Ireland, and Iain Coyne. 2009. Bullying in Different Contexts: Commonalities, Differences and the Role of Theory. Aggression and Violent Behavior 14: 146–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, Linda K., and Bengt O. Muthén. 2017. Mplus Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables User’s Guide. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto, Jonathan, and David Schwartz. 2010. Is Peer Victimization Associated With Academic Achievement? A Meta-Analytic Review. Social Development 19: 221–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natvig, Gerd Karin, Grethe Albrektsen, and Ulla Qvarnstrøm. 2001. School-Related Stress Experience as a Risk Factor for Bullying Behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 30: 561–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, José C., Guillermo Vallejo, Pedro Rosário, Elián Tuero, and Antonio Valle. 2013. Student, Teacher, and School Context Variables Predicting Academic Achievement in Biology: Analysis From a Multilevel Perspective//Variables Del Estudiante, Del Profesor Y Del Contexto En La Predicción Del Rendimiento Académico En Biología: Análisis. Revista de Psicodidactica/Journal of Psychodidactics 19: 145–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2014. Pisa 2012 Technical Report. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2017. Pisa 2015 Results (Volume III). Students’ Well-Being. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2018. Equity in Education. Breaking Down Barriers to Social Mobility. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2023. Pisa 2022 Results (Volume I). The State of Learning and Equity in Education. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus, Dan. 1994. Bullying At School: Basic Facts and Effects of a School Based Intervention Program. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 35: 1171–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, Dan, and Kyrre Breivik. 2014. Plight of Victims of School Bullying: The Opposite of Well-Being. In Handbook of Child Well-Being. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 2593–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletta, Angelo, Fabio Alivernini, and Sara Manganelli. 2017. Leadership for Learning. International Journal of Educational Management 31: 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistella, Jessica, Emanuela Baumgartner, Fiorenzo Laghi, Marco Salvati, Nicola Carone, Fausta Rosati, and Roberto Baiocco. 2020. Verbal, Physical, and Relational Peer Victimization: The Role of Immigrant Status and Gender. Psicothema 32: 214–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plenty, Sara, and Jan O. Jonsson. 2017. Social Exclusion Among Peers: The Role of Immigrant Status and Classroom Immigrant Density. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 46: 1275–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottie, Katherine, Gopal Dahal, Katherine Georgiades, Khalid Premji, and Ghayda Hassan. 2015. Do First Generation Immigrant Adolescents Face Higher Rates of Bullying, Violence and Suicidal Behaviours Than Do Third Generation and Native Born. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 17: 1557–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Q’Moore, Anne M., Caroline Kirkham, and Michael Smith. 1997. Bullying Behaviour in Irish Schools: A Nationwide Study. The Irish Journal of Psychology 18: 141–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaran, J. Ashwin, Jan Kornelis Dijkstra, and René Veenstra. 2020. Bullying as a Group Process in Childhood: A Longitudinal Social Network Analysis. Child Development 91: 1336–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudenbush, Stephen W., and Anthony S. Bryk. 2002. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Rigby, Ken, and Phillip Slee. 1999. Suicidal Ideation Among Adolescent School Children, Involvement in Bully—Victim Problems, and Perceived Social Support. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 29: 119–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roland, Erling, and Thormod Idsøe. 2001. Aggression and Bullying. Aggressive Behavior 27: 446–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, Nicole L., and Stacey Nofziger. 2019. Boys, bullying, and gender roles: How hegemonic masculinity shapes bullying behavior. Gender Issues 36: 295–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarento, Silja, Antti Kärnä, Ernest V. E. Hodges, and Christina Salmivalli. 2013. Student-, Classroom-, and School-Level Risk Factors for Victimization. Journal of School Psychology 51: 421–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarento, Silja, Claire F. Garandeau, and Christina Salmivalli. 2015. Classroom- and School-level Contributions to Bullying and Victimization: A Review. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 25: 204–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmivalli, Christina. 2010a. Bullying and the Peer Group: A Review. Aggression and Violent Behavior 15: 112–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmivalli, Christina. 2010b. Participant Role Approach to School Bullying: Implications for Interventions. Journal of Adolescence 22: 453–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmivalli, Christina, Kirsti Lagerspetz, Kaj Björkqvist, Karin Österman, and Ari Kaukiainen. 1998. Bullying as a Group Process: Participant Roles and Their Relations to Social Status Within the Group. Aggressive Behavior 22: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, David, JoAnn M. Farver, Lei Chang, and Yoolim Lee-Shin. 2002. Victimization in South Korean Children’s Peer Groups. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 30: 113–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seals, Deborah, and John Young. 2003. Bullying and Victimization: Prevalence and Relationship to Gender, Grade Level, Ethnicity, Self-Esteem, and Depression. Adolescence 38: 735–47. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanek, Elisabeth, Dagmar Strohmeier, Rens van de Schoot, and Christiane Spiel. 2011. Bullying and Victimization in Ethnically Diverse Schools: Risk and Protective Factors on the Individual and Class Level. International Journal of Developmental Science 5: 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohmeier, Dagmar, and Petra Gradinger. 2022. Cyberbullying and Cyber Victimization as Online Risks for Children and Adolescents. European Psychologist 27: 141–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohmeier, Dorothea, Anita Kärnä, and Christina Salmivalli. 2011. Intrapersonal and Interpersonal Risk Factors for Peer Victimization in Immigrant Youth in Finland. Developmental Psychology 47: 248–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Orozco, Carola, Frosso Motti-Stefanidi, Amy Marks, and Dalal Katsiaficas. 2018. An Integrative Risk and Resilience Model for Understanding the Adaptation of Immigrant-Origin Children and Youth. American Psychologist 73: 781–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeting, Helen, Robert Young, Patrick West, and Geoff Der. 2006. Peer Victimization and Depression in Early–Mid Adolescence: A Longitudinal Study. British Journal of Educational Psychology 76: 577–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Televantou, Ioulia, Herbert W. Marsh, Leonidas Kyriakides, Benjamin Nagengast, John Fletcher, and Lars-Erik Malmberg. 2015. Phantom Effects in School Composition Research: Consequences of Failure to Control Biases Due to Measurement Error in Traditional Multilevel Models. School Effectiveness and School Improvement 26: 75–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornberg, Robert, Bertil Wegmann, Linda Wänström, Ylva Bjereld, and Jun Sung Hong. 2022. Associations Between Student–Teacher Relationship Quality, Class Climate, and Bullying Roles: A Bayesian Multilevel Multinomial Logit Analysis. Victims & Offenders 17: 1196–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornberg, Robert, Linda Wänström, Björn Sjögren, Ylva Bjereld, Silvia Edling, Guadalupe Francia, and Peter Gill. 2024. A Multilevel Study of Peer Victimization and Its Associations With Teacher Support and Well-Functioning Class Climate. Social Psychology of Education 27: 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornberg, Robert, Linda Wänström, Jun Sung Hong, and Dorothy L. Espelage. 2017. Classroom Relationship Qualities and Social-Cognitive Correlates of Defending and Passive Bystanding in School Bullying in Sweden: A Multilevel Analysis. Journal of School Psychology 63: 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ttofi, Maria M., David P. Farrington, Friedrich Lösel, and Rolf Loeber. 2011a. Do the Victims of School Bullies Tend to Become Depressed Later in Life? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research 3: 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ttofi, Maria M., David P. Farrington, Friedrich Lösel, and Rolf Loeber. 2011b. The Predictive Efficiency of School Bullying Versus Later Offending: A Systematic/meta-Analytic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health 21: 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNESCO. 2012. International Standard Classification of Education Isced 2011. Paris: UNESCO-UIS. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2019. Behind the Numbers: Ending School Violence and Bullying. Paris: UNESCO-UIS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Geel, Mitch, Anouk Goemans, Wendy Zwaanswijk, Gianluca Gini, and Paul Vedder. 2018. Does Peer Victimization Predict Low Self-Esteem, or Does Low Self-Esteem Predict Peer Victimization? Meta-Analyses on Longitudinal Studies. Developmental Review 49: 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Sophie D., Bart De Clercq, Michal Molcho, Yossi Harel-Fisch, Colleen M. Davison, Katrine Rich Madsen, and Gonneke W. J. M. Stevens. 2016. The Relationship Between Immigrant School Composition, Classmate Support and Involvement in Physical Fighting and Bullying Among Adolescent Immigrants and Non-Immigrants in 11 Countries. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 45: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Sophie D., Michal Molcho, Wendy Craig, Yossi Harel-Fisch, Quynh Huynh, Atif Kukaswadia, Katrin Aasvee, Dora Várnai, Veronika Ottova, Ulrike Ravens-Sieberer, and et al. 2013. Physical and Emotional Health Problems Experienced By Youth Engaged in Physical Fighting and Weapon Carrying. PLoS ONE 8: e56403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yu-Jiao, and I-Hua Chen. 2023. A Multilevel Analysis of Factors Influencing School Bullying in 15-Year-old Students. Children 10: 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, Ian, and Peter K. Smith. 1993. A Survey of the Nature and Extent of Bullying in Junior/middle and Secondary Schools. Educational Research 35: 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiertsema, Maria, Charlotte Vrijen, Rozemarijn van der Ploeg, Miranda Sentse, and Tina Kretschmer. 2023. Bullying Perpetration and Social Status in the Peer Group: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Adolescence 95: 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williford, Anne, and Andrew Zinn. 2018. Classroom-Level Differences in Child-Level Bullying Experiences: Implications for Prevention and Intervention in School Settings. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research 9: 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williford, Anne, Paula J. Fite, Debbie Isen, and Jonathan Poquiz. 2019. Associations Between Peer Victimization and School Climate: The Impact of Form and the Moderating Role of Gender. Psychology in the Schools 56: 1301–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolke, Dieter, William E. Copeland, Adrian Angold, and E. Jane Costello. 2013. Impact of Bullying in Childhood on Adult Health, Wealth, Crime, and Social Outcomes. Psychological Science 24: 1958–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolke, Dietmar, and Sibel T. Lereya. 2015. Long-Term Effects of Bullying. Archives of Disease in Childhood 100: 879–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolke, Dietmar, Sally Woods, Kathy Stanford, and Henning Schulz. 2001. Bullying and Victimization of Primary School Children in England and Germany: Prevalence and School Factors. British Journal of Psychology 92 Pt 4: 673–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Bin, Bo Wang, Nan Sun, Fei Xu, Lianke Wang, Jiajun Chen, Shiwei Yu, Yiming Zhang, Yurui Zhu, Ting Dai, and et al. 2021. The Consequences of Cyberbullying and Traditional Bullying Victimization Among Adolescents: Gender Differences in Psychological Symptoms, Self-Harm and Suicidality. Psychiatry Research 306: 114219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwierzynska, Karolina, Dietmar Wolke, and Sibel T. Lereya. 2013. Peer Victimization in Childhood and Internalizing Problems in Adolescence: A Prospective Longitudinal Study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 41: 309–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zych, Izabela, Rosario Ortega-Ruiz, and Rosario Del Rey. 2015. Systematic Review of Theoretical Studies on Bullying and Cyberbullying: Facts, Knowledge, Prevention, and Intervention. Aggression and Violent Behavior 23: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).