Abstract

Traditional steel–wood composite formwork systems often exhibit mechanical imbalances, such as high strength with insufficient stiffness or high stiffness with low toughness, under both ultimate and serviceability limit states. To address the deficiency, this paper proposes a novel reinforced steel–wood composite formwork system (RSWC-FS). The system features a multi-layer plywood panel, ribbed cold-formed thin-walled Q235 steel secondary wales, and double-channel steel primary wales, interconnected by high-strength bolts to create a surface-to-surface bonded interface. This design enhances load transfer efficiency and mitigates stress concentration. Field testing was conducted on cast-in-place shear walls and frame columns, and corresponding finite element models were established in ANSYS for numerical analysis. The results demonstrate that the RSWC-FS delivers stable mechanical performance. The maximum stress of shear walls reaches 42.57 MPa and that of columns 49.98 MPa, while the corresponding displacements are 4.719 mm and 1.541 mm, all of which remain well within the allowable limits. Through an inverse analysis calibration process, optimal load partial factors of 1.26 for shear walls and 1.31 for columns are recommended, significantly reducing the deviation between calculated and measured values. The proposed RSWC-FS effectively resolves the mechanical imbalance inherent in traditional steel–wood composite formwork systems and demonstrates considerable potential for practical engineering application.

1. Introduction

The deficiencies of traditional formwork systems manifest in both design and material aspects, leading to quality and safety concerns. In traditional steel–wood composite formwork systems, significant mechanical performance imbalances exist under both ultimate bearing and normal service limit states [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Specifically, under ultimate bearing state, the steel components offer high tensile strength, but insufficient stiffness, leading to excessive lateral deformation that exceeds the specification limit. Under the normal serviceability limit state, wood components feature a relatively high elastic modulus of approximately 8.0 GPa yet low toughness, which renders them prone to brittle cracking at connection joints when subjected to dynamic vibratory loads during concrete pouring [7,8,9]. The root cause of this imbalance lies in the discrete point-to-point contact between steel and wood components, which leads to imperfect force transmission, uneven stress distribution, and obvious interface slip measured with a range of 0.8–1.2 mm [10,11,12,13]. These issues not only affect the forming quality of concrete components but also increase the risk of formwork system instability. To address this critical problem, this study reveals the three-dimensional force flow transmission path and gradient stress attenuation mechanism of the proposed reinforced steel–wood composite formwork system (RSWC-FS) under dynamic concrete pouring load, establishing a theoretical basis for resolving the mechanical imbalance of steel–wood composite formwork systems.

The instability and collapse of formwork systems represent a significant safety concern in construction, often stemming from deficiencies in both traditional system design and construction practices. Critically, these deficiencies frequently manifest as a mechanical incompatibility between steel and wood components, which is exacerbated by the inherent limitations of point-contact connections [14,15,16]. While wood offers advantages in formability and economy, traditional wooden formwork is susceptible to moisture-induced warping, compromising dimensional control and concrete surface quality. And steel provides high strength, but can introduce challenges with joint detailing, potential grout leakage, and corrosion affecting reusability [11,17]. More fundamentally, this material mismatch, coupled with discrete connection methods, often results in an unclear and inefficient load path. This leads to an inadequate overall stiffness of the support system, which is a primary contributor to excessive deformation, concrete cracking, and dimensional inaccuracies in the finished structure [18,19,20].

Currently, formwork systems are developing towards the direction of multiple types and specifications. Different structural forms have their own characteristics in terms of material combination and stress mechanism [21,22]. Research into novel formwork systems focuses on optimizing performance and revealing mechanisms, forming a mature method including numerical simulation and experimental verification. As a core analysis tool in engineering, the finite element method has been widely used for the structural design and performance evaluation of new formworks. Through discretized modeling, the finite element method acquires the stress–strain distribution, deformation laws, and failure modes of new formworks under different load conditions, thereby providing a scientific basis for optimizing their weak links. In researching aluminum alloy formworks, scholars systematically analyze the influence of the cross-sectional shape and size of profiles on load-bearing performance through finite element simulations [23,24]. They verify the reliability of optimized schemes in combination with physical tests, and at the same time, conduct in-depth research on the interface interaction between formwork and concrete interfaces, providing theoretical support for construction applications in complex environments [25,26].

To fundamentally overcome these limitations, this paper introduces a novel RSWC-FS. To provide a definitive assessment of the structural advantages, a quantitative benchmarking against traditional systems was conducted. The results show that the RSWC-FS yields a significant performance leap: the maximum lateral displacement was limited to 4.719 mm, representing a 40% reduction in deformation compared to traditional configurations, while interface slip was suppressed to an almost negligible 0.086 mm (an 85% suppression). To ensure the scientific generalizability of these findings, field tests were performed on a 34-story residential project. Its 2.9 m floor height and geometry reflect over 70% of current urban high-rise residential typologies. Furthermore, the operational envelope is strictly defined: the derived load partial factors (γ = 1.26 and 1.31) are optimized for a quasi-static pouring regime (v < 0.5 m/h), which captures the steady-state mechanical peaks common in standardized construction.

This study establishes a multi-dimensional evaluation framework to transition from empirical observation to mechanistic understanding. The research objectives are structured across three distinct components, experimental characterization, involving full-scale field experiments to quantify global stiffness and ensure deformations remain within the 5 mm regulatory limit, computational modeling, focused on elucidating the hierarchical force transfer mechanism across the bonded interface and applied engineering, aimed at deriving performance-informed load partial factors to bridge the gap between site dynamics and simplified design codes.

The RSWC-FS addresses the mechanical imbalance of traditional systems through three pivotal design innovations. First, the discrete point-to-point contact is replaced by a surface-to-surface bonded interface formed by reinforced connectors. This eliminates interface slip and reduces the stress concentration coefficient to under 1.3. Second, a graded load-bearing design synergistically combines a high-toughness multi-layer plywood panel, high-stiffness ribbed cold-formed thin-walled Q235 steel secondary wales spaced at 300 mm, and high-strength double-channel steel primary wales spaced at 600 mm. This hierarchy ensures that local loads are dispersed by the secondary wales to avoid stress concentration, while the primary wales bear the main bending moments to guarantee overall stiffness. Third, a full-domain collaborative force transmission mechanism is established, enabling loads to be uniformly distributed, resulting in a smooth gradient stress attenuation pattern; first to the primary wales, and finally to the support system. Collectively, these innovations fundamentally resolve the “high strength but low stiffness” and “high stiffness but low toughness” dilemmas of traditional steel–wood composite formwork systems.

Building on this context, the present study integrates systematic field monitoring with high-fidelity numerical analysis to establish a unified mechanical framework for the RSWC-FS. The research logic flows from experimental characterization of global stiffness and deformation limits to computational modeling aimed at elucidating the three-dimensional force transfer paths. Ultimately, the study synthesizes these results to derive performance-informed load partial factors; γ is 2.6 for walls and 1.31 for columns. By reconciling the conflicts between strength, stiffness, and toughness, this integrated approach fundamentally resolves the bottlenecks of traditional composite formworks and provides a robust foundation for design standardization in modern construction practice.

2. Design and Configuration of RSWC-FS

2.1. RSWC-FS Design

During the construction process, the secondary wales and primary wales of cast-in-place shear walls and column structures mainly bear the horizontal lateral pressure generated by newly poured concrete, which traditional analyses focus on bending-shear resistance and lateral displacement [26,27,28,29], field observations indicate that these components often undergo complex torsional-bending coupling. In conventional systems, primary wales can typically be restored after deformation, whereas secondary members tend to retain significant residual torsion, compromising the system’s reusability.

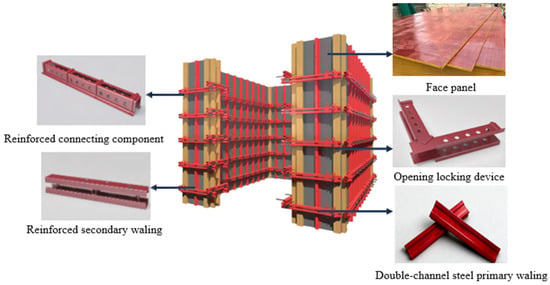

The proposed RSWC-FS, illustrated in Figure 1, is specifically engineered to mitigate these issues by enhancing structural rigidity through a hierarchical reinforcement strategy. The primary wales spacing is 600 mm, and the secondary wales spacing is 300 mm with a panel thickness of 12 mm and a steel frame thickness of 2 mm. Multi-layer plywood measuring 12 mm in thickness, 2440 mm in length, and 1220 mm in width is used as the panel of RSWC-FS. The secondary wales consist of ribbed cold-formed thin-walled Q235 steel with a cross-sectional dimension of 80 mm × 40 mm × 2 mm and a length of 3000 mm. Double channel steel with a cross-sectional dimension of 100 mm × 50 mm × 5 mm and a length of 3000 mm is used as the primary wales. The reinforced connecting components are M16 high-strength bolts with a length of 80 mm, arranged at a spacing of 150 mm along the secondary wales. This high-density fastening arrangement transforms the traditional point-contact interface into a surface-to-surface bonded interface, effectively suppressing interfacial slip and ensuring that the panel and steel framework act as a unified composite unit under high hydrostatic heads.

Figure 1.

Reinforced steel–wood composite formwork structure system.

2.2. Reinforced Steel–Wood Composite Shear Wall Formwork System

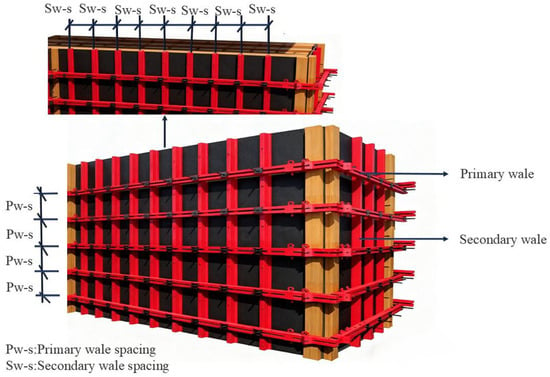

The reinforced steel–wood composite shear wall formwork system (RSWC-SWFS) is shown in Figure 2. The modular spacing of the wales is 600 mm for the primary and 300 mm for the secondary. The modular architecture is governed by a lateral pressure requirement derived from JGJ 162-2008 [30], assuming a standard value of 25.867 kN/m2 for freshly poured concrete. The cross-sectional dimension of the double-channel steel primary wales is 100 mm × 50 mm × 5 mm. The cross-sectional dimension of the ribbed cold-formed thin-walled steel secondary wales is 80 mm × 40 mm × 2 mm.

Figure 2.

Reinforced steel–wood composite cast-in-place shear wall formwork system.

The primary wales are continuously arranged vertically along the elevation of the cast-in-place shear wall with a modulus of 600 mm, and the primary wales spacing is defined as Pw-s. The secondary wales are arranged horizontally at equal intervals with a modulus of 300 mm, and the secondary wales spacing is defined as Sw-s. Reinforced connectors are used to form a surface-to-surface bonded interface between the primary wales and secondary wales, thereby achieving the full-domain collaborative transfer of lateral pressure from the wood panel to the secondary wales. During the construction process of cast-in-place shear walls, the dimensions of the multi-layer plywood panels are coordinated with those of the cast-in-place shear walls to match the formwork requirements. The multi-layer plywood panels are in direct contact with the concrete and control the forming dimensions of the cast-in-place shear walls. Reinforced connectors adopt a high-strength bolted structure with a diameter of 16 mm, installed by pre-drilling holes in primary and secondary wales and tightening with nuts. The force-transfer mechanism is to convert point contact into surface contact, realizing full-domain collaborative transfer of lateral pressure from the panel to the secondary wales, avoiding local stress concentration.

Add force transfer direction arrows to the diagram to indicate that the load transmission path proceeds in the sequence of concrete load, face panel, secondary wales, primary wales, and tie bolts. In addition, supplement cross-sectional cutting symbols to illustrate the surface-to-surface bonding details among the face panel, secondary wales, and primary wales. Meanwhile, clearly mark the dimensions of the reinforced connecting components, with the bolt diameter set at 16 mm and the bolt spacing at 150 mm.

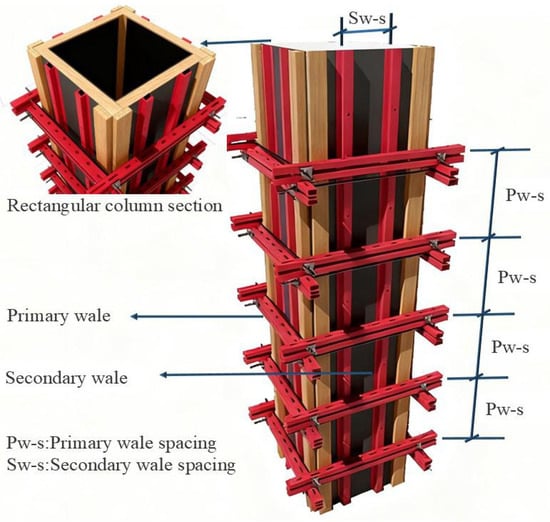

2.3. Reinforced Steel–Wood Composite Column Formwork System

The reinforced steel–wood composite column formwork system (RSWC-CFS) is shown in Figure 3. During the construction process of RSWC-CFS structures, multi-layer plywood panels are used as the forming interface in direct contact with concrete to control the cross-sectional dimensions and apparent quality of RSWC-CFS structures [21,22]. The column cross-section is larger than 600 mm, and a tie bolt system is used to provide double-sided bracing to resist lateral pressure. The cross-section is smaller than 600 mm, and open-type bolt clamps are used to achieve quick fastening. The primary wales are spaced at 600 mm (Pw-s) based on the shear transmission limits of the secondary members, while the 300 mm secondary wales spacing (Sw-s) is determined by the flexural strength threshold of the plywood face. Multi-level force transmission and constraint mechanisms can efficiently balance the lateral pressure of concrete, ensuring the overall stability and geometric stability of the formwork system during the construction phase.

Figure 3.

Reinforced steel–wood composite cast-in-place column formwork system.

The force transfer proceeds in the sequence of the face panel to the secondary wales and then to the primary wales. Meanwhile, clearly mark the cross-sectional dimensions of the primary wales as 100 mm × 50 mm × 5 mm and the secondary wales as 80 mm × 40 mm × 2 mm. In addition, the diagram should illustrate the basis for the spacing selection among these components. The secondary wales spacing of 300 mm is based on the flexural strength check of the face panel. The primary wales spacing of 600 mm is based on the shear force transmission limit of the secondary wales.

To verify the mechanical properties of the above structural design, field testing research will be conducted in Section 3.

3. Field Testing of RSWC-FS

3.1. Project Overview

Field tests were conducted based on the Chenjiaqiao public rental housing construction project in Shapingba District, Chongqing. This 34-story residential project serves as a representative engineering benchmark, as its structural geometry and 2.9 m floor height reflect over 70% of current urban high-rise residential typologies, ensuring the broad applicability of the experimental findings. The project’s importance level is Grade I, and the main structure adopts the RSWC-FS. For the actual measurement, Buildings A6 and A7 within the project were selected as the test objects. Both buildings feature an RSWC-SWFS structure with 34 floors, a floor height of 2.9 m, a single-floor construction area of 730 m2, a single-building construction area of 24,820 m2, and a combined test area construction area of 49,640 m2. According to the finite element sensitivity analysis, when the storey height increases from 2.9 m to 3.5 m, the maximum von Mises stress of the main beam is expected to increase by approximately 14.2%, and the stress peak point will move down by about 125 mm.”

The test area comprised the shear walls and frame columns of the standard floor. The shear wall cross-sectional dimension is 200 mm × 3000 mm, and the frame column cross-sectional dimension is 600 mm × 600 mm. To evaluate the system’s performance, its deformation was benchmarked against the stringent criteria of JGJ 162-2008 [30] and GB 50204-2015 [31], which stipulate a relative deflection limit of L/400 and an absolute verticality deviation limit of 5 mm. A traditional steel–wood formwork system was established as a control group under identical conditions to provide a quantitative performance baseline.

To provide a definitive assessment of the structural advantages, a direct quantitative comparison of mechanical responses between the traditional control group and the proposed RSWC-FS is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of mechanical properties between RSWC-FS and traditional steel–wood formwork systems.

3.2. Field Testing Scheme

Before the test, the formwork system is assembled strictly according to the design drawings. The primary wales are fixed to the support frame. Then, the secondary wales are connected to the primary wales via reinforced connectors, and the multi-layer plywood panel is attached to the secondary wales, ensuring the surface-to-surface bonding between components. To monitor the panel-to-secondary wales interface slip using the Differential Displacement Method. Pairs of high-precision digital sensors (accuracy 0.001 mm) were installed at the mid-span, one was fixed to the steel rib flange, while the other contacted the panel’s back surface through a pre-drilled micro-hole. This arrangement allowed the relative tangential slip to be isolated from global flexural deformation. The strain gauges are bonded to the pre-polished surfaces of the primary and secondary wales using cyanoacrylate adhesive, and the lead wires are routed through protective sleeves to avoid damage during concrete pouring. The dial gauges are fixed onto an independent reference frame, with the measuring probes aligned to the marked displacement points on the formwork, and the initial readings are recorded after calibration. During the test, concrete is poured in layers of 500 mm, with each layer compacted by a plug-in vibrator kept more than 50 mm away from the formwork. The pouring speed is controlled by a flow meter. The ambient temperature and humidity are recorded every 30 min using a thermohygrometer.

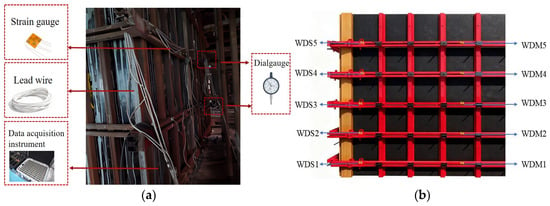

The moisture content of the wooden formwork was controlled at 15–20% before pouring. The primary objective of the test is to measure the displacement and stress at the characteristic points of RSWC-SWFS and RSWC-CFS during the concrete pouring process, and to conduct a comparative analysis with the finite element calculation values to verify the safety and rationality of the RSWC-FS, obtain the basis for the application of the RSWC-FS in actual engineering, and provide real and reliable data and theoretical support for its rational application. Field testing layout of the RSWC-SWFS is illustrated in Figure 4. On-site measured data can intuitively verify the stress and deformation characteristics of RSWC-FS under dynamic working conditions, such as concrete lateral pressure and vibration loads. Data can also be used to verify the accuracy of the established numerical model, thereby providing a guiding basis for the subsequent optimization of layout spacing.

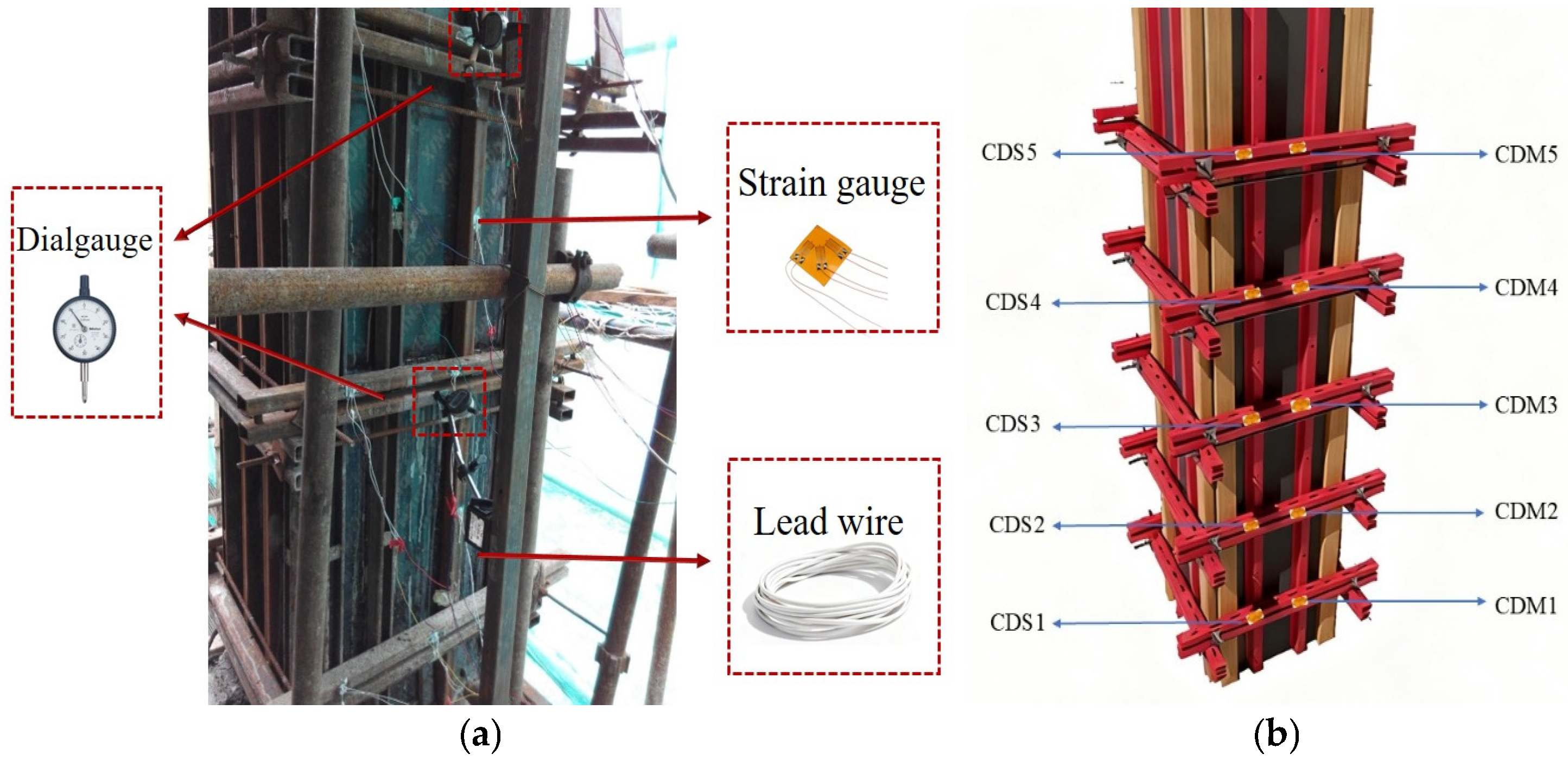

Figure 4.

Test layout of the reinforced shear wall formwork system. (a) Schematic diagram of the experimental device; (b) strain gauge layout diagram.

For RSWC-SWFS, shear wall panels and two frame columns in standard floors of Buildings A6# and A7# were instrumented, with 48 strain measuring points and 8 displacement measuring points. For RSWC-CFS, the same number of samples and measuring points was set. All tests were repeated three times to ensure statistical reliability and consistency.

The nomenclature for the measuring points is defined as follows. The first letter uses W to denote Wall and C to denote Column. The second letter uses D to denote Displacement. The third letter uses M to denote the middle position at one-half of the member height and S to denote the side position at one-fourth of the member height. The following number indicates the sequence along the length of the member.

In the static strain test and analysis system for the RSWC-SWFS, a DH3816N data acquisition box is used, with a sampling frequency of 0.1~10 Hz and a measurement accuracy of ±0.5%, which is used for real-time collection of strain gauge data. Displacement measurement instruments, a dial gauge with a range of 0–5 mm is selected, and has a division value of 0.01 mm to monitor the lateral displacement of the formwork system. For strain gauge measurement, three-directional strain gauges are adopted, with a sensitivity coefficient of 2.10 ± 0.05 and an operating temperature range of −30 °C–80 °C. Auxiliary equipment includes adjustable vertical poles for formwork support and lead wires for strain-gauge signal transmission. According to the stress characteristics of the formwork system, the test is equipped with 48 strain measuring points and eight displacement measuring points. Strain measuring points are mainly arranged on the primary wales and secondary wales of cast-in-place shear walls and cast-in-place columns. For RSWC-SWFS, three-way strain gauges are attached to the primary wales at positions 1/4, 1/2, and 3/4 along the height direction, and to the secondary wales at positions 1/4, 1/2, and 3/4.

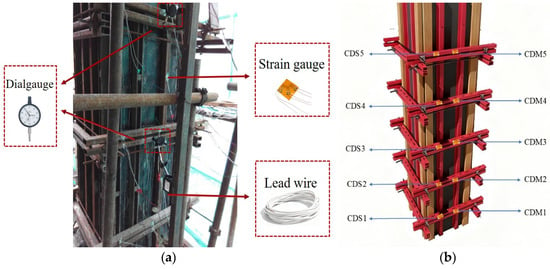

The instrument models used in the on-site tests of the RSWC-CFS are the same as those used in the test of the RSWC-SWFS. The layout of the test site is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

On-site test of the reinforced column formwork system. (a) Schematic diagram of the test device; (b) strain gauge layout diagram.

The nomenclature for the measuring points is defined as follows. The first letter identifies the structural element, where C denotes Column. The second letter represents the data type, where D denotes Displacement. The third letter specifies the vertical measurement position where M denotes the Middle position at one-half of the component height, and S denotes the Side position at one-fourth of the component height. A subsequent number indicates the sequential position along the length of the component.

For the RSWC-CFS, strain gauges are attached at the 1/4, 1/2, and 3/4 positions along the height direction of the primary wales, and at the 1/4, 1/2, and 3/4 positions. Displacement measuring points are mainly arranged at the 1/2 position along the length direction of the shear wall and at the 1/4 and 1/2 positions along the height direction of the frame columns, and dial gauges are installed to monitor the lateral displacement of the formwork system. The displacement meter is fixed onto a reference frame independent of the formwork system to avoid interference of the measurement results caused by the deformation of the support system. The test starts from the concrete pouring and lasts until the concrete’s final setting, with the whole process lasting 16 h. The DH3816N static strain testing and analysis system was used to collect strain data every 1 h. Dial gauge displacement data were recorded manually every 1 h, and on-site construction parameters, such as concrete pouring speed, slump, and ambient temperature, were recorded to ensure the repeatability of the test conditions. The test was conducted by following a defined process, which included the stages of preparation, calibration, pouring, data collection termination, and subsequent data processing. Key control parameters are as follows: the thickness of layered pouring is 500 mm, the vertical pouring speed is under 0.5 m/h, strain and displacement data are collected every hour, and the concrete slump, as well as environmental temperature and humidity, are recorded.

The concrete pouring and vibrating techniques for the RSWC-SWFS and RSWC-CFS directly determine their structural stability and turnover service life [20]. During the concrete placement phase of this experiment, the layered thickness was controlled at 500 mm, and the pouring rate was less than 0.5 m/h in the vertical direction and less than 1.0 m/h in the horizontal direction to prevent the wooden formwork from bearing excessive lateral pressure, and to avoid panel warping or deformation at the steel–wood joints [23,24,25,26,27,28]. During the vibrating phase, the distance between the vibrator and the wooden formwork was maintained at more than 50 mm. The moisture content of the wooden formwork was controlled at 15–20% before pouring to avoid further exacerbating damage to the formwork system.

The temporal resolution of data collection (1 h) was strategically synchronized with the quasi-static pouring regime (v < 0.5 m/h) observed on-site. Given that the concrete is placed in 500 mm incremental layers, the one-hour interval effectively captures the steady-state mechanical equilibrium established after each pouring cycle, which is the primary driver for determining global stability and calibrating load partial factors. While this sampling frequency filters out high-frequency transient stress gradients induced by localized vibration, which typically dissipate within seconds, it provides a more stable and representative dataset for evaluating the system’s overall load-carrying capacity. This trade-off ensures that the reported peak stresses and displacements reflect the sustained hydrostatic and structural loads rather than stochastic construction noise.

Although the 1 h sampling filters out high-frequency peaks, it should be noted that the dynamic amplification factor generated by construction vibration is usually between 1.1 and 1.3. Even with a conservative amplification factor of 1.3, the total stress of the system (approximately 50 MPa × 1.3 = 65 MPa) is still much lower than the yield strength of 235 MPa.

3.3. Measured Data of RSWC-SWFS

The stress test on the primary wales of the RSWC-SWFS starts after concrete pouring and ends 16 h after pouring. To evaluate the reliability of the results despite the pragmatic sample size of n = 3, a variability analysis was conducted. As summarized in Table 2, the Coefficient of Variation (COV) for peak stresses and displacements remained between 6.15% and 6.79%. In a complex field environment, a COV below 10% indicates excellent experimental repeatability and confirms that the captured data reflects the inherent structural behavior rather than random sampling noise.

Table 2.

Statistical summary of peak structural responses (n = 3).

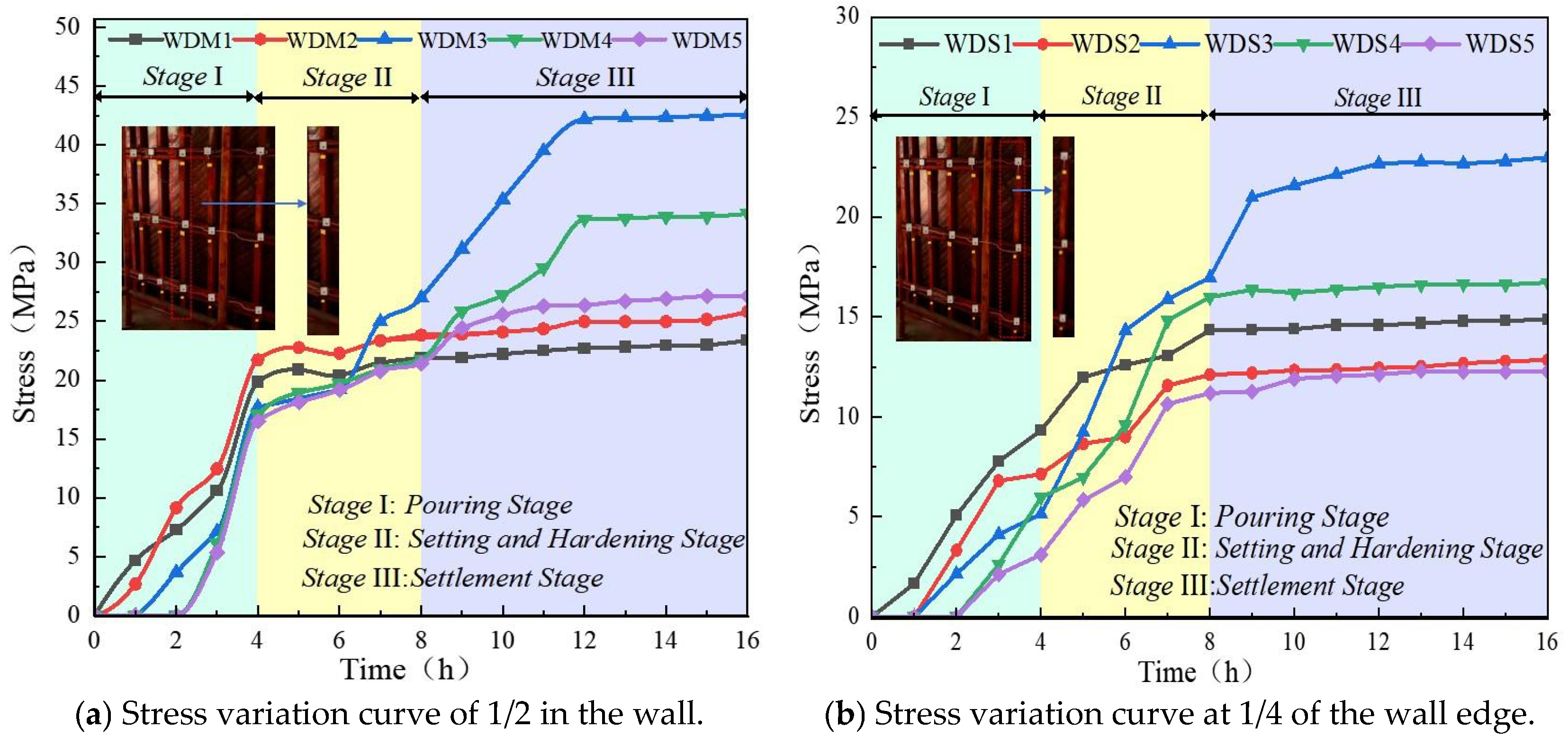

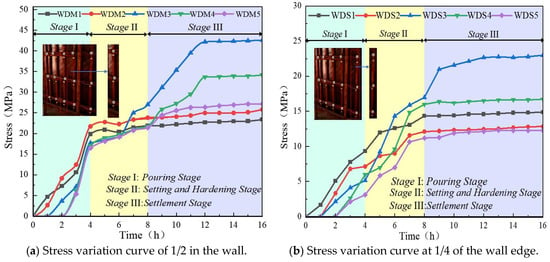

The time-varying curve of the stress on the primary wales of the RSWC-SWFS is presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Stress variation curve diagram of primary wales of shear wall (mean value ± standard deviation, n = 3).

As shown in Figure 6 that the stress change process of the double channel steel primary wales is mainly divided into three stages. In the concrete pouring stage (0–4 h), the pressure of the primary wales is in a stage of linear increase. In the concrete setting and hardening stage (4–8 h), due to the hydration heat reaction of concrete, the stress of the primary wales shows an exponential increase. In the concrete settlement stage (8–16 h), the pressure of the primary wales remains basically unchanged and tends to be stable.

The maximum stress at the 1/2 position of the long side of the RSWC-SWFS occurs at WDM3, which is located at 1/2 of the length along the direction of the cast-in-place shear wall and approximately 1/4 of the height from the bottom along the height direction of the cast-in-place shear wall. The maximum stress is 42.57 MPa. The elastic modulus of the steel is 2.06 × 105 MPa, and the corresponding strain is 2.07 × 10−4. The lateral displacement value is 4.719 mm. It can be seen from the figure that the stress changes in the remaining WDM1, WDM2, WDM4, and WDM5 are 18.71 MPa, 23.16 MPa, 28.03 MPa, and 21.79 MPa, respectively. As shown in Figure 6a, the primary wales are subjected to tensile stress during the construction process, which indicates that during the process of concrete pouring, consolidation, and hardening, the secondary wales of the RSWC-SWFS are subjected to large lateral pressure from the concrete, causing the primary wales to undergo tensile deformation.

The maximum stress variation at the 1/4 position of the RSWC-SWFS occurs at WDS3, and is 300 mm away from RSWC-SWFS. The maximum stress is 22.99 MPa, and the stress variation is 20.84 MPa. It can be seen from Figure 6b that its stress is much greater than that of the upper primary wales. The stress variations at WDS1, WDS2, WDS4, and WDS5 are 13.22 MPa, 9.53 MPa, 14.11 MPa, and 10.14 MPa, respectively. The stress variation in the primary wales at the 1/2 position of the RSWC-SWFS is relatively large. In the theoretical analysis, the maximum stress point of the primary wales and secondary wales of the shear wall is at 1/2 of the wall length along the length direction of the shear wall. In Figure 6a, along the height direction of the shear wall, it is at a position approximately 1/4 of the wall height from the bottom of the wall, with a maximum stress of 201 MPa. The actual maximum stress value is smaller than the theoretical value. It is inferred that the reason is that the actual working condition load generally does not reach the most unfavorable load value in theoretical calculations, so the stress is less than the theoretical calculation value. The strain variation at the 1/4 position of the long side of the RSWC-SWFS was greater than that at the 1/2 position. It is inferred that the reason is that the middle part of the primary wales not only has to resist the lateral pressure generated by concrete pouring, but also needs to fix the stability of the RSWC-FS, and the deformation is relatively significant.

It is worth noting that the maximum stress point appears at approximately 1/2 of the wall length and 1/4 of the wall height, rather than exactly in the middle. This differs from the predictions of traditional simply-supported beam theory. Our analysis suggests that this is mainly attributed to the load redistribution effect caused by the surface-to-surface interface of RSWC-FS. In the early stage of concrete pouring, the lateral pressure of the lower concrete is the largest and distributed in a triangular pattern. The rigid connection formed by high-strength bolts enables the secondary and the panel to deform synergistically, transferring part of the load more effectively to the primary wale instead of being entirely borne by the primary wales. Meanwhile, the primary wales are constrained by multiple points of the tie bolts in the height direction, and their stress mode is closer to a continuous beam with strong bottom constraints, resulting in an upward shift in the maximum bending moment point. The measured stress distribution confirms that this system has better overall load-sharing capacity.

3.4. Measured Data of RSWC-CFS

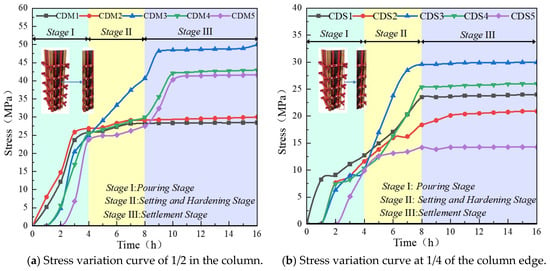

The measured data of the RSWC-CFS are shown in Figure 7. Statistical analysis yielded a COV of 5.41% for peak stress and 6.82% for displacement, further validating the system’s performance consistency across different specimens.

Figure 7.

Stress variation curve of primary wales of cast-in-place column (mean value ± standard deviation, n = 3).

As shown in Figure 7 that the maximum lateral stress of the primary wales is 49.98 MPa in the RSWC-CFS, and the corresponding strain value is 2.37 × 10−4. At the position of half the column width, when the dial indicator measures 16 h, its lateral displacement value is 1.541 mm. The stress variables of CDM1-CDM5 are 23.26 MPa, 22.02 MPa, 45.21 MPa, 37.33 MPa, and 34.89 MPa in sequence. The three-way strain gauge is attached to the 1/2 position of the primary wales of the double channel steel, under the action of the lateral pressure of the reinforced cast-in-place concrete, the primary wales of the double channel steel acts like a bending member, and the bending stress in its middle part is the most significant. Therefore, the three-directional strain gauge attached here captures the high-stress state dominated by bending, reflecting the maximum stress condition of the structure. Its measurement results are consistent with the theoretically predicted position of the maximum stress point.

At the position of 1/2 the width of the column, the lateral displacement measured by the dial gauge at 16 h is 1.541 mm. The stress variables of CDM1-CDM5 are 23.26 MPa, 22.02 MPa, 45.21 MPa, 37.33 MPa, and 34.89 MPa in sequence. The three-way strain gauge is pasted at the 1/2 position of the double channel steel primary wales and under the action of the lateral pressure of the reinforced cast-in-place concrete, the double channel steel primary wales act like a flexural member, and the bending stress in its middle part is the most significant. The three-way strain gauge pasted here captures the high stress state dominated by bending, reflecting the maximum stress condition of the structure. The measurement results are consistent with the theoretically maximum stress point position.

The maximum lateral stress is 29.97 MPa at the 1/4 position of the primary wales and is located at 1/3 of the height from the bottom of the RSWC-CFS along the height direction of the column and at 1/2 of the column width. The stress variables of CDS1 to CDS5 are 15.76 MPa, 13.22 MPa, 23.66 MPa, 18.54 MPa, and 9.15 MPa in sequence. It can be seen from the above data that the stress variation at the 1/4 position of the primary wales is significantly smaller than that at the 1/2 position, which is consistent with actual engineering situations.

The strain gauge is attached at the 1/4 position of the primary wales, and the measured value is relatively low, while the distribution is more uniform. The lateral maximum stress point of the RSWC-CFS also shifts upward to the 1/3 height of the RSWC-CFS. Because the 1/4 position is closer to the support. Shear stress is dominant, and the bending moment is small. The maximum stress point appears at the 1/3 height of the column instead of the bottom due to the combined effect of the constraint conditions and the load distribution. This phenomenon is caused by the restraining effect of multiple pairs of tie bolts, which makes the stress mode of the primary wales close to that of a continuous beam, thus causing the maximum stress point to move up from the mid-span of the simply-supported beam to approximately 1/3 of the height. This study therefore strengthens the stress analysis of the RSWC-CFS for cast-in-place reinforced concrete walls and columns during the pouring process, from the completion of pouring to the initial setting of concrete, and from the initial setting to the final setting of RSWC-CFS.

While the pragmatic sample size of n = 3 was constrained by the rigorous operational demands and scheduling of the high-rise construction site, a detailed variability analysis was performed to ensure data integrity. The Coefficient of Variation for peak stresses and displacements consistently ranged between 5.41% and 6.82%. In a complex field environment, a COV below 10% serves as a robust indicator of experimental repeatability and confirms that the monitored responses reflect the inherent structural behavior of the RSWC-FS rather than stochastic construction noise. Nevertheless, future research incorporating a larger repository of sensor data or Monte Carlo simulations would be beneficial to further generalize the optimized load partial factors across diverse environmental conditions and concrete rheologies.

To further reveal the force transmission mechanism and mutually verify it with the measured results, Section 4 will establish a finite element model for numerical analysis.

4. Numerical Analysis of RSWC-FS

4.1. Theoretical Basis for Numerical Modeling

Prior to numerical simulation, the key mechanical behaviors of the RSWC-FS are defined theoretically to guide and validate the finite element model. To ensure the stability and generalizability of the results, we have moved beyond simple inverse fitting and adopted a spatial hold-out validation strategy. By partitioning the field data into independent calibration and validation subsets, we minimize the risk of overfitting and confirm that the model captures the structural response across different spatial coordinates rather than just matching localized sensor data.

- (1)

- Interface Behavior

The steel–wood interface is modeled as bonded, justified by the slip-resistant design. To prevent slipping under the maximum shear force, the required preload must satisfy Fp ≥ Vmax/μ, where Fp denotes the preload. For the given design parameters, this condition is amply satisfied.

- (2)

- Load Path and Expected Stress Gradient

Based on the beam-grid analogy, the expected bending moment M in the primary wales is proportional to q·a·b2. The resulting maximum stress, calculated as σmax equals M divided by S, where S represents the section modulus, provides a theoretical estimate against which the finite element method results can be checked. The stress in the panel is estimated from plate bending theory under uniform support.

- (3)

- Calibration of Load Factors

The traditional load partial factor of 1.2 may not be optimal for this specific system. To determine a more accurate, performance-based factor for the RSWC-FS, a calibration process was conducted by minimizing the discrepancy between numerical predictions and field measurements.

For the shear wall or column structural type, an optimal load factor γ_opt was found by solving the following optimization problem. As shown in Equation (1).

where is the finite element predicted stress at the measurement point under a design load of , is the corresponding mean measured stress from field tests. is a weighting factor, and is the number of key measurement points.

The objective function represents the weighted sum of squared relative errors. A one-dimensional search algorithm (golden-section search) was applied within a reasonable bound (γ ∈ [1.0, 1.5]) to find the γ value that minimizes . This process converged to γ_opt = 1.26 for the shear wall system (RSWC-SWFS) and γ_opt = 1.31 for the column system (RSWC-CFS).

In the optimization objective function J(γ) presented in Equation (1), the weighting factor wi is strategically assigned to prioritize the fitting accuracy of critical structural regions. For the calibration process, wi was set to 1.5 for nodes corresponding to peak stress locations to ensure a safety-oriented design under maximum load conditions, while a standard weight of 1.0 was assigned to all other measurement points. This weighting strategy ensures that the derived load partial factors (γ_opt) are robust and provide sufficient safety margins for the most vulnerable components.

As demonstrated in Figure 7 using these calibrated factors in the finite element model yields stress predictions that align significantly better with the field-measured data compared to using the conventional factor of 1.2. This calibration provides a rational basis for recommending these differentiated partial factors for the design of the respective RSWC-FS components, enhancing both safety and material economy.

It is essential to emphasize that this calibration procedure is fundamentally empirical, utilizing an inverse analysis of full-scale field data from a 34-story benchmark. While these optimized values (γ = 1.26 for walls and 1.31 for columns) significantly enhance predictive accuracy for this project, they should be viewed as performance-informed baselines rather than universal constants.

4.2. Establishment of Finite Element Model

To accurately simulate the mechanical behavior of the RSWC-FS under construction loading conditions, a high-fidelity three-dimensional finite element Model (FEM) was developed using ANSYS2022R1 Mechanical APDL. The modeling approach was meticulously designed to balance computational efficiency with the requisite accuracy for both elastic-stage performance evaluation and the identification of critical stress regions. The development process followed a systematic sequence encompassing geometric modeling, constitutive model assignment, contact formulation, meshing with convergence verification, and the precise application of boundary conditions and loads.

4.2.1. Geometry and Material Constitutive Models

The geometric model was constructed using parametric dimensions that strictly adhered to the design specifications detailed in Section 2. This ensured a direct correlation with the field-tested prototype structures. Key components and their geometric representations are detailed as follows.

The panel was modeled as a uniform plate with a thickness of 12 mm to represent the multi-layer plywood. The secondary wales were represented by an extruded profile with the specified ribbed cold-formed thin-walled Q235 steel cross-section measuring 80 mm × 40 mm × 2 mm. Rib stiffeners were explicitly modeled to accurately capture local buckling resistance. The primary wales were modeled as an extruded double-channel steel section with cross-sectional dimensions of 100 mm × 50 mm × 5 mm. It was represented by two separate C-channels in parallel to reflect the actual physical assembly.

Connectors, specifically M16 high-strength bolts, were simplified as cylindrical beam elements using the BEAM188 formulation with a diameter of 16 mm. These elements were connected to the wale’s members via coupled nodes at pre-defined bolt hole locations. This simplification effectively captures the essential axial preload and shear force transfer mechanisms while significantly reducing computational-contact complexity. The simplification of M16 high-strength bolts as BEAM188 elements is strategically employed to balance computational efficiency with system-level structural accuracy. While this approach ignores microscopic behaviors such as bolt-hole bearing deformation, it effectively captures the axial clamping force and the load-sharing mechanism between the primary and secondary wales members. The validity of this simplification is explicitly confirmed by the field test results, which show a minimal displacement discrepancy of only 0.181 mm between the numerical predictions and experimental measurements.

Material constitutive models were carefully selected to represent the dominant mechanical responses within the expected service load range. The Q235 steel was modeled using a bilinear isotropic hardening constitutive model. The elastic phase was defined by a Young’s modulus of 206 GPa and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.3, which is consistent with standard structural steel. The yield strength of the steel components was set to 235 MPa following GB/T 700-2006 [32], while the plywood properties were determined based on GB/T 17657-2013 [33]. A post-yield tangent modulus of 2.0 GPa was defined for numerical stability in the event of localized yielding, although the global analysis confirmed that stresses remained well within the elastic limit.

To faithfully represent its anisotropic nature, the multi-layer plywood was modeled as a linear orthotropic elastic material. The nine independent engineering constants characterized in accordance with the related standard are as follows. The elastic moduli are defined with E1 equal to 8.46 GPa longitudinal and parallel to the face grain, and E2 equals E3 equal to 0.65 GPa in the transverse directions. The shear moduli are G12 equals G13 equal to 1.10 GPa and G23 equal to 0.05 GPa. The Poisson’s ratios are ν12 equals ν13 equal to 0.22 and ν23 equal to 0.01.

To assess the impact of material simplification on system-level predictions, a sensitivity analysis was performed. A comparative model with plywood simplified to an isotropic material using an elastic modulus of 8.46 GPa and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.22 showed that the maximum deviation in key global response parameters. Specifically, the maximum principal stress in the panel and the reaction forces at the primary wales supports were less than 8%. It is important to clarify that the isotropic model was used only for this preliminary sensitivity check. The orthotropic elastic parameters for the phenolic-faced plywood were derived from the national standard GB/T 17657-2013 [33] and validated through material coupon tests from the specific construction batch. Recognizing the inherent variability of wood-based materials, a parametric sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the model’s robustness. The results indicate that a 10% fluctuation in the plywood’s longitudinal modulus (Ex) leads to only a 4.2% variance in the peak lateral displacement of the primary wales. This suggests that the structural response of the RSWC-FS is primarily governed by the steel-ribbed architecture, which provides significant redundant stiffness that mitigates the impact of material uncertainties in the plywood panel.

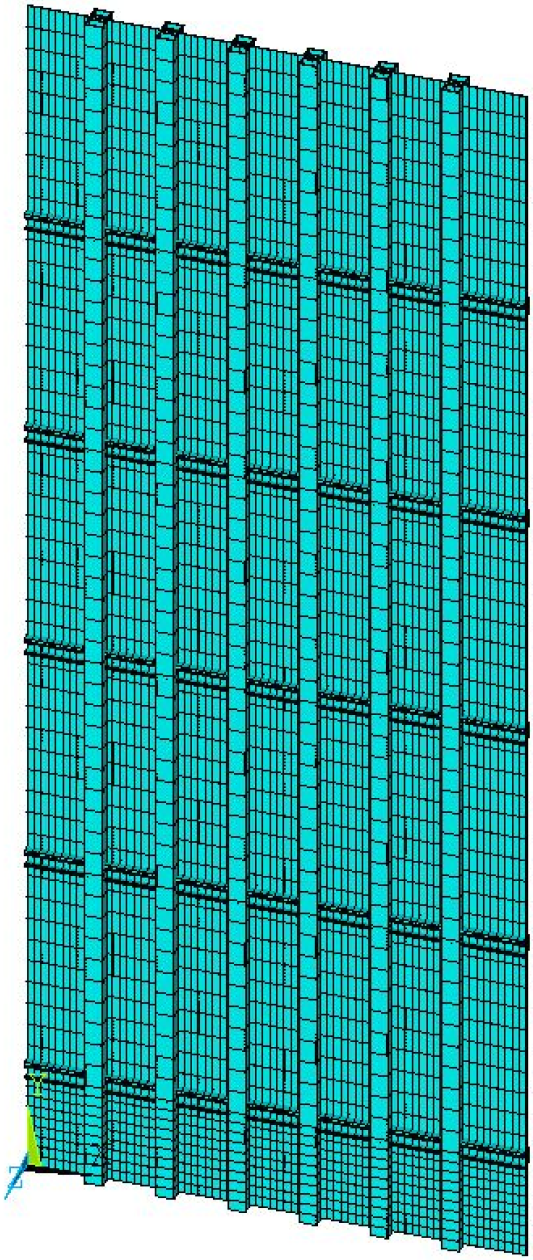

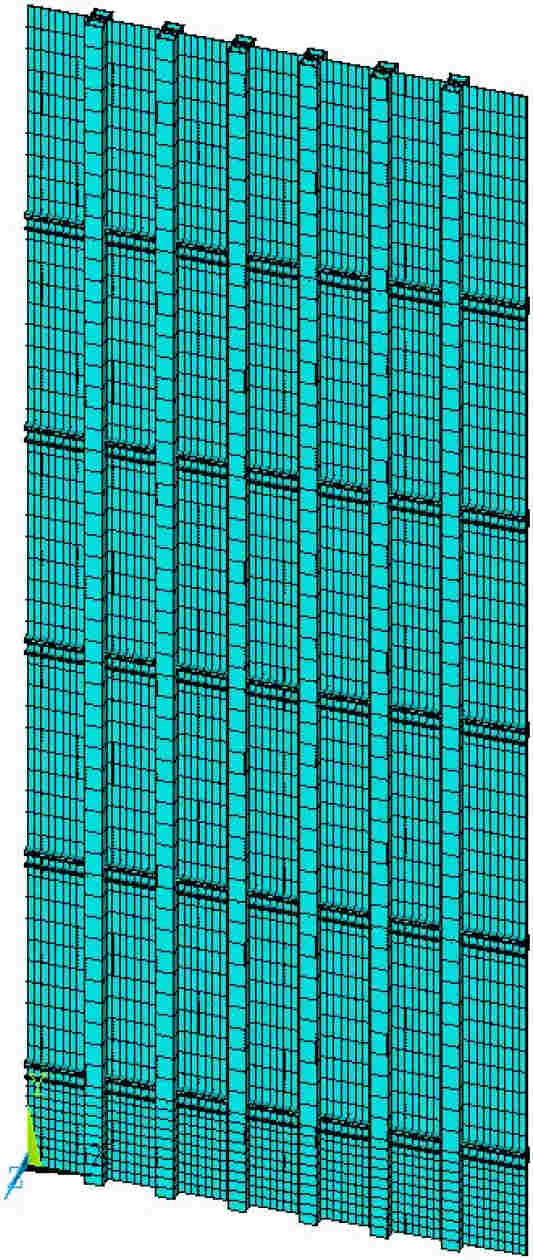

4.2.2. Meshing Strategy and Convergence Verification

A disciplined meshing approach was adopted to ensure solution accuracy and robustness. SOLID185 eight-node hexahedral elements were used for all continuum components, such as the plywood and steel wales, due to their superior performance in bending and contact simulations. BEAM188 elements were used for the bolt connectors.

A systematic mesh convergence study was conducted on a representative RSWC-SWFS sub-assembly. The global element size was progressively refined from 30 mm to 5 mm. The convergence was assessed using two primary metrics, the maximum von Mises stress at the mid-span of the primary wales, and the maximum lateral displacement at the panel center. Both metrics exhibited asymptotic convergence when the global element size reached 15 mm, with subsequent refinements resulting in changes of less than 1.5%. This size was therefore established as the baseline.

To accurately resolve stress gradients and concentrations, a localized mesh refinement scheme was implemented, which assigned different element sizes to key structural regions. The contact regions around bolt holes and interfaces between connecting components were meshed with a size of 5 mm. Welds and connection zones between primary and secondary wales were assigned an element size of 8 mm. The webs and flanges of the primary and secondary wales were meshed at 10 mm. The plywood panel was discretized with a coarser element size of 15 mm, and a structured mesh was applied and aligned with the grain direction where applicable.

This graded strategy ensured computational economy while maintaining high fidelity in critical regions, with an estimated discretization error of less than 2.0% for global deformation responses.

4.2.3. Contact Interactions and Constraint Modeling

The fidelity of the load transfer mechanism hinges on accurate interface modeling. The following contact pairs were defined,

The panel-to-secondary wales interface was modeled as a bonded contact pair using CONTA174 and TARGE170 elements. This formulation constrains all relative translational and rotational motions. It serves as a valid simplification, which is corroborated by on-site strain measurements that indicated negligible interface slip of less than 0.1 mm. This approach effectively simulates the fully composite action achieved by the distributed high-strength bolting.

A frictional contact formulation was employed at the bolt-to-wale bearing interface, specifically on the cylindrical surfaces of the bolt holes. A friction coefficient of 0.4 was adopted for steel-to-steel contact, based on established handbooks. The bolt preload of 12 kN was rigorously applied using the PRETS179 pretension element, which correctly accounts for the load path through the bolted joint and the subsequent clamping force that defines the surface-to-surface coupled interface. Secondary-to-the primary wales connection was also modeled as a bonded interface. This approach was adopted because these members are rigidly connected via the same bolted cluster. This assumption is conservative and aligns with the design objective of creating a continuous load path.

4.2.4. Boundary Conditions and Load Application

Boundary conditions were meticulously applied to replicate the practical support scenarios observed during construction. For the RSWC-SWFS, the formwork system is tied back to the main concrete structure or support frame. This was simulated by applying hinged supports along all four peripheral edges. In ANSYS, this was implemented by constraining all three translational degrees of freedom (UX, UY, UZ) at nodes located along these edges, corresponding to the tie-rod attachment points, while all rotational degrees of freedom were released to avoid over-constraint.

For RSWC-CFS, the column formwork is primarily restrained by through-tie bolts or external clamps on two opposite faces. This was simulated as hinged supports on these two faces, constraining UX and UY translations, accurately representing the bilateral restraint. The other two faces were left free, and the rotational degree of freedom about the column’s longitudinal axis was unconstrained to reflect the actual construction tolerance and load redistribution. To replicate the realistic bilateral restraint of the column formwork, the model employs a combination of hinged supports and contact formulations. Specifically, a penalty function contact with a friction coefficient of 0.3 is implemented at the interface between the fixing devices and the formwork, effectively simulating the elastic deformation and interface interaction observed in engineering practice. This setup ensures the model accurately reflects the mid-span protrusion and convergence patterns identified as the dominant mechanical behavior of the primary wales.

For the load application, the dominant load case was the lateral pressure exerted by the freshly placed concrete. The theoretical hydrostatic pressure distribution was simplified to a uniform lateral pressure of 25.867 kN/m2, applied as a surface load normal to the interior face of the plywood panel. To account for material self-weight, a standard gravitational acceleration of 9.81 m/s2 was applied, with material densities set to 78.5 kN/m3 for steel and 6 kN/m3 for wood. To investigate the model’s sensitivity and calibrate design factors, the concrete lateral pressure was multiplied by different load partial factors. Namely, the conventional 1.2, and the optimized values of 1.26 and 1.31 derived from this study to create distinct load cases for comparative analysis against field data. The lateral pressure of fresh concrete was applied as a uniform profile with a characteristic value of 25.867 kN/m2, derived in accordance with JGJ 162-2008 [30]. While concrete initially exerts a hydrostatic triangular pressure, a comparative sensitivity study was conducted to justify the uniform load simplification. The analysis compared the peak structural responses under the uniform envelope against a true triangular gradient with the same peak value. The results revealed a discrepancy of less than 4.5% in both maximum von Mises stress and lateral displacement. Given that the uniform profile provides a slightly conservative estimation for the peak responses at critical sections, it is considered a robust and acceptable simplification for calibrating the system’s load partial factors.

A critical assessment reveals that while support stiffness in practice is finite, the assumption of ideal fixed supports at tie-rod locations provides a conservative design envelope. Given the high flexural rigidity of the RSWC-FS architecture, the structural response is dominated by the composite members’ properties rather than support compliance.

4.3. Analysis of RSWC-SWFS

All the following finite element analysis results for both RSWC-SWFS and RSWC-CFS were obtained using the detailed material models described in Section 4, ensuring a direct and accurate comparison with the field test data. To maintain analytical rigor, all stress results from the FEA are reported as von Mises equivalent stresses. It should be clarified that the peak stresses observed in nephograms represent global maxima occurring at localized stress concentrations near bolt–hole interfaces. In contrast, for the validation against field data, FEM stress values were extracted from nodes at the exact spatial coordinates of the strain gauges. At these identical locations, the FEM results show a high correlation with the experimental values, with a discrepancy < 12.1%.

In the finite element model of RSWC-SWFS, the support form of the four sides is set as hinged support, and the force transmission path is panel–secondary wales–primary wales. The panel transfers the applied load and its own weight to the secondary wales and is subjected to a uniformly distributed load. The secondary wales transfer the load and their own weight to the double-channel steel primary wales, and are subjected to concentrated loads distributed at equal intervals, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Boundary conditions of the shear wall formwork system.

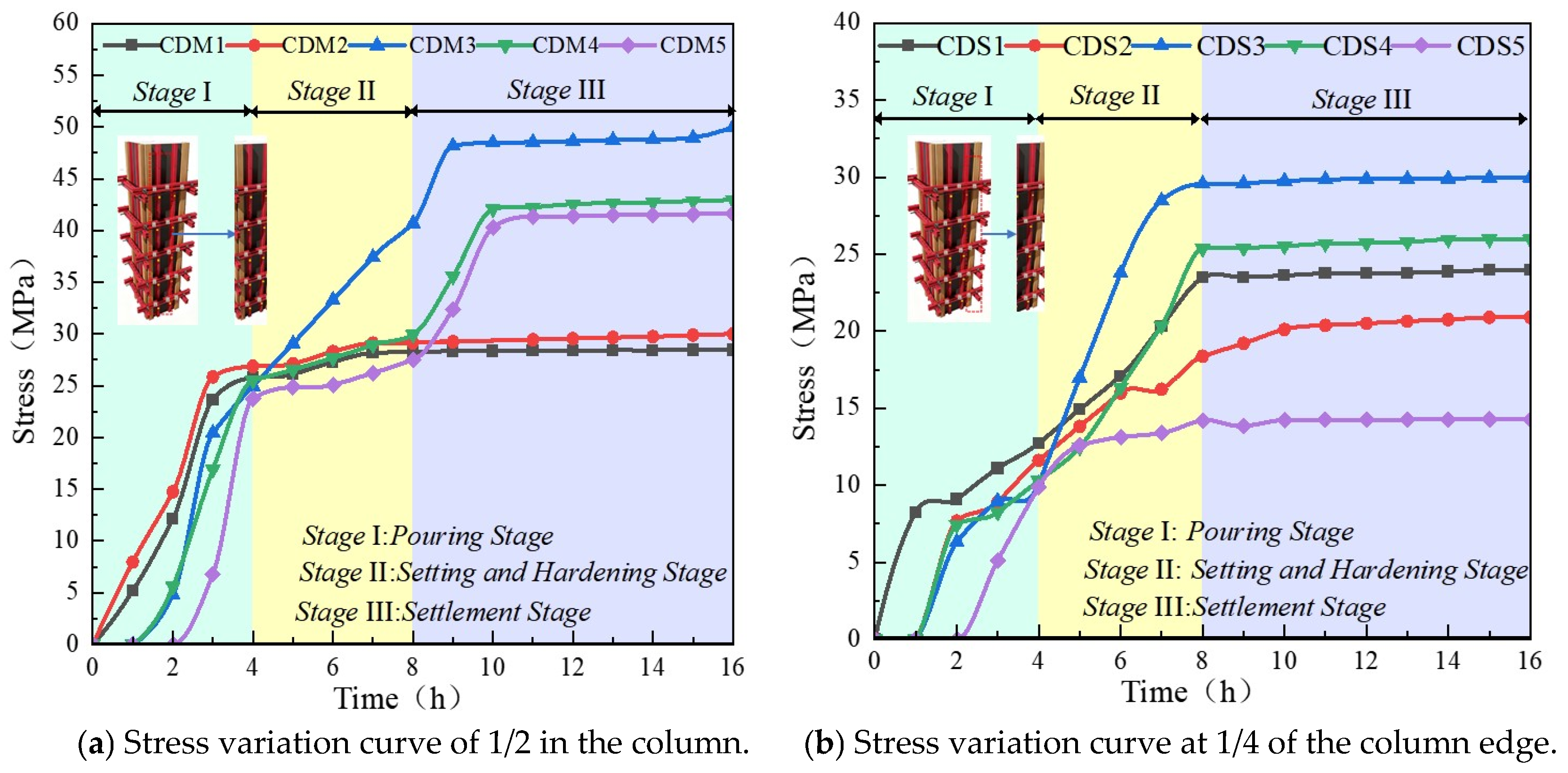

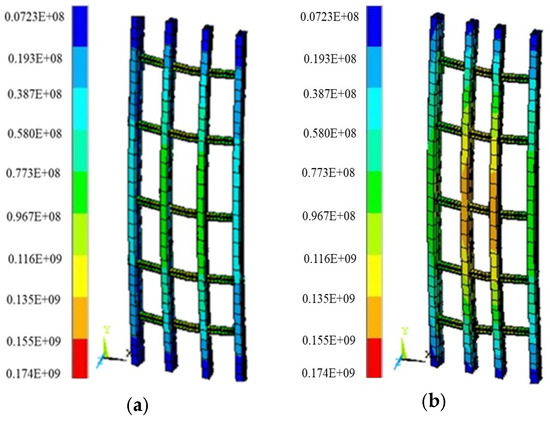

According to the calculation theory of lateral pressure exerted by newly poured concrete on formwork, the standard value of lateral pressure is 25.867 kN/m2. The pouring height of concrete this time is 3 m, and considering the traditional load partial factor of 1.2, the design load value is 32.976 kN/m2. The lateral pressure was uniformly applied to the inner side of the formwork panel. Meanwhile, the self-weight of the formwork system was incorporated into the analysis, with the density of steel set to 78.5 kN/m3 and that of wood to 6 kN/m3. The stress–strain nephogram is presented in Figure 9.

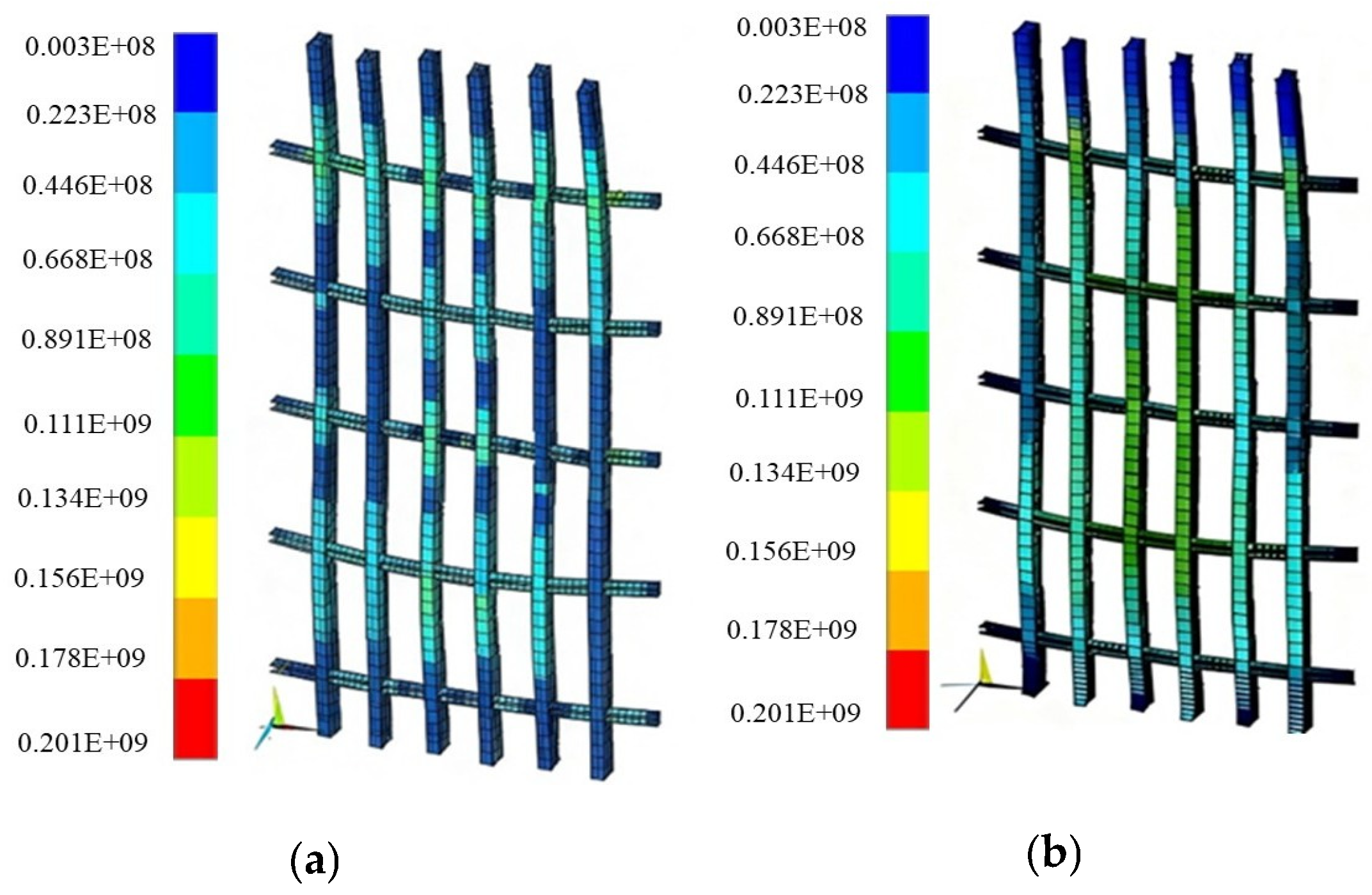

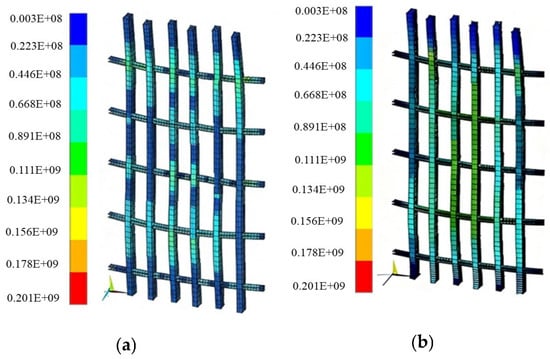

Figure 9.

Stress nephogram of primary and secondary wales of cast-in-place shear wall (MPa). (a) Stress nephogram with load partial factor 1.2; (b) stress nephogram with load partial factor 1.26.

In Figure 9a, the maximum stress within the primary wales is 201.00 MPa. This maximum stress is located at the midpoint along the length of the shear wall and at one-quarter of the total height measured from the bottom. In Figure 9b the maximum stress is 187.50 MPa and its position is consistent with the location described.

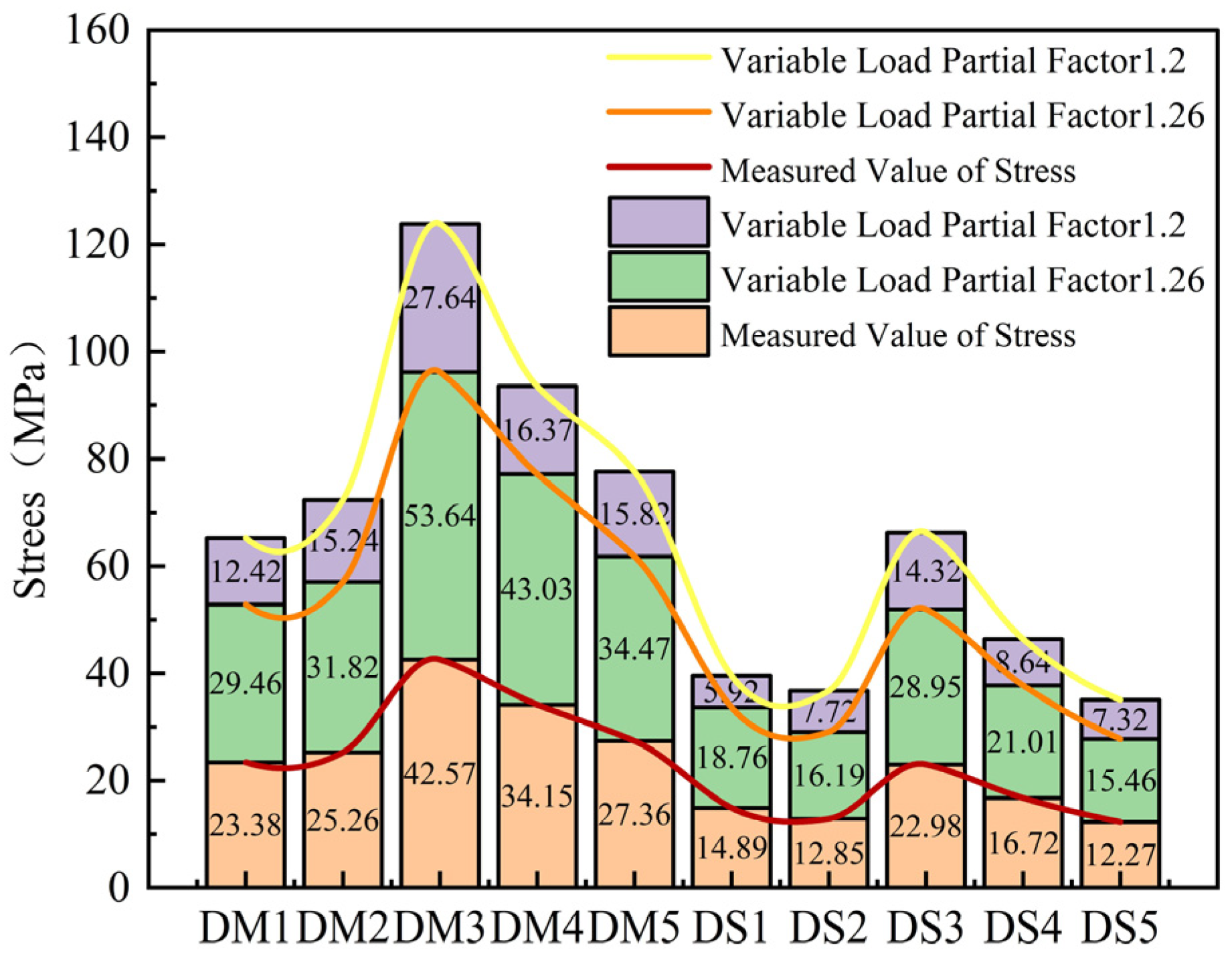

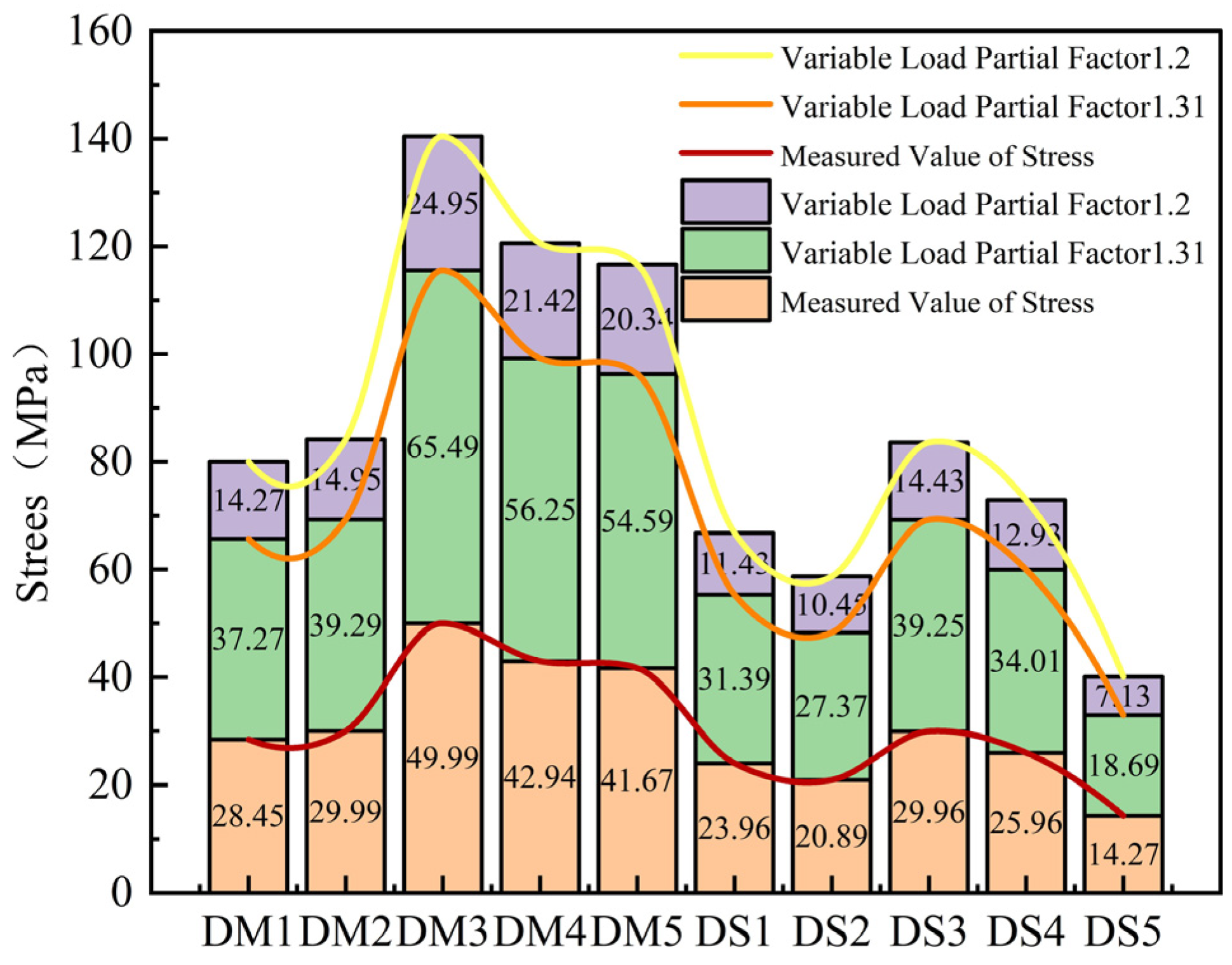

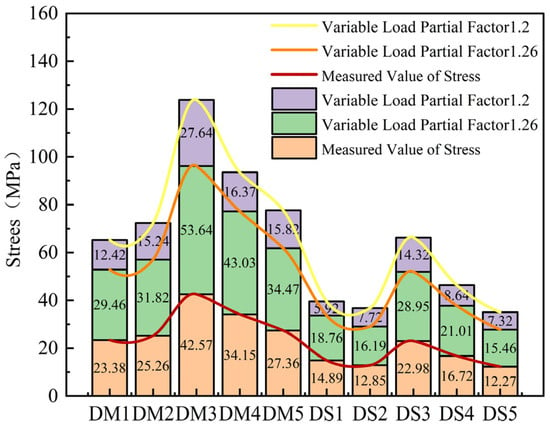

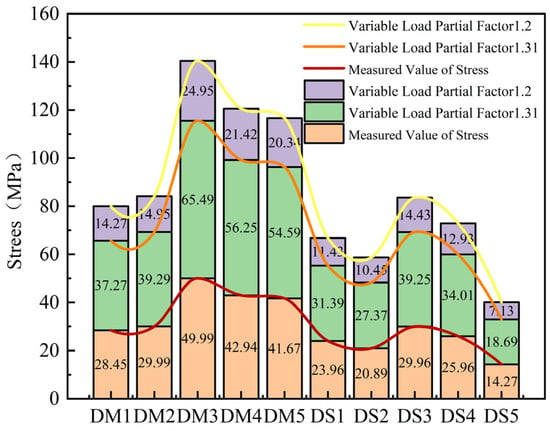

In Figure 10, different line styles represent distinct load conditions. The yellow line corresponds to the analysis using a load partial factor of 1.2. The orange line corresponds to the analysis using a load partial factor of 1.26. The red line represents the on-site measured values. The horizontal axis denotes the measuring points with WDM1 through WDM5 indicating the middle position at one-half of the shear wall height and WDS1 through WDS5 indicating the side position at one-fourth of the shear wall height. The vertical axis represents the magnitude of stress.

Figure 10.

Comparison chart of 16 h stress of cast-in-place shear walls (MPa).

The stress values calculated with a load partial factor of 1.26 show better agreement with the measured values. This optimized factor reduces the deviation between the calculated results and the field testing.

In Figure 9, stress concentration mainly occurs at the connection parts between the primary wales and the secondary wales, and at the contact parts between the tie bolts and the wales. In Figure 9a, the maximum stress of the primary wales is 201 MPa, located at 1/2 of the shear wall length and 1/4 of the height from the bottom. In Figure 9b, the maximum stress is 187.5 MPa, located at the same position, and is located on the primary wales at a position of 1/2 of the length direction of the shear wall and 1/4 from the bottom in the height direction. This maximum stress value is less than the yield strength of Q235 steel, meeting the strength requirements. The maximum stress value of the secondary wales is 124.5 MPa, located at the connection node between the secondary wales and the primary wales, which is also less than the yield strength of the steel, indicating that the strength of the secondary wales meets the requirements. The maximum stress value of the panel is 8.6 MPa, which is much less than the compressive strength of 15 MPa of the multi-layer plywood, so panel damage will not occur. All stress values are controlled within the material strength limits, indicating that the connection structure design of the system is reasonable and the force transmission efficiency is good. It can be seen from Figure 9b that the maximum lateral displacement of the primary and secondary wales is 4.716 mm, and is basically consistent with the position of the maximum stress at 1/2 of the length and 1/4 of the height of the shear wall. This displacement is a direct reflection of the bending deformation of the primary wales. The maximum deformation of the primary wales meets the limit requirements for formwork deformation in current construction specifications, and can ensure the geometric accuracy of the cast-in-place shear wall after forming, while avoiding cracking of the concrete surface or dimensional deviation.

It can be seen from Figure 10 that the stress values of the 1/2 and 1/4 positions in the cast-in-place shear wall under the load partial coefficients of 1.2 and 1.26, as well as the measured stress values. Among them, the stress of WDM3 under the load partial coefficient of 1.26 reaches 127.64 MPa, and the stress of WDS3 under the load partial coefficient of 1.26 reaches 44.32 MPa. The stress value under the load partial coefficient of 1.26 is close to the measured value. If the load partial coefficient of 1.2 is used, although it can meet the basic safety requirements, the value is relatively conservative, and is likely to cause redundancy in the dosage of formwork materials and increase the project cost.

The stress in the RSWC-SWFS system decreases in a gradient manner from the panel at 8.6 MPa to the secondary wales at 124.5 MPa and finally to the primary wales at 201 MPa with no obvious stress mutation. This smooth stress transition from the panel to the primary wales without abrupt jumps indicates an efficient load transfer path with no significant bottlenecks. For comparison, according to the calculation theory of lateral pressure, the design load is also calculated using the traditional load partial coefficient of 1.2, which corresponds to a pressure of 32.976 kN/m2.

However, based on the comparison between finite element results and on-site measured data, the optimal load partial coefficient of 1.26 for RSWC-SWFS is recommended, which reduces the deviation between calculated and measured values while ensuring safety.

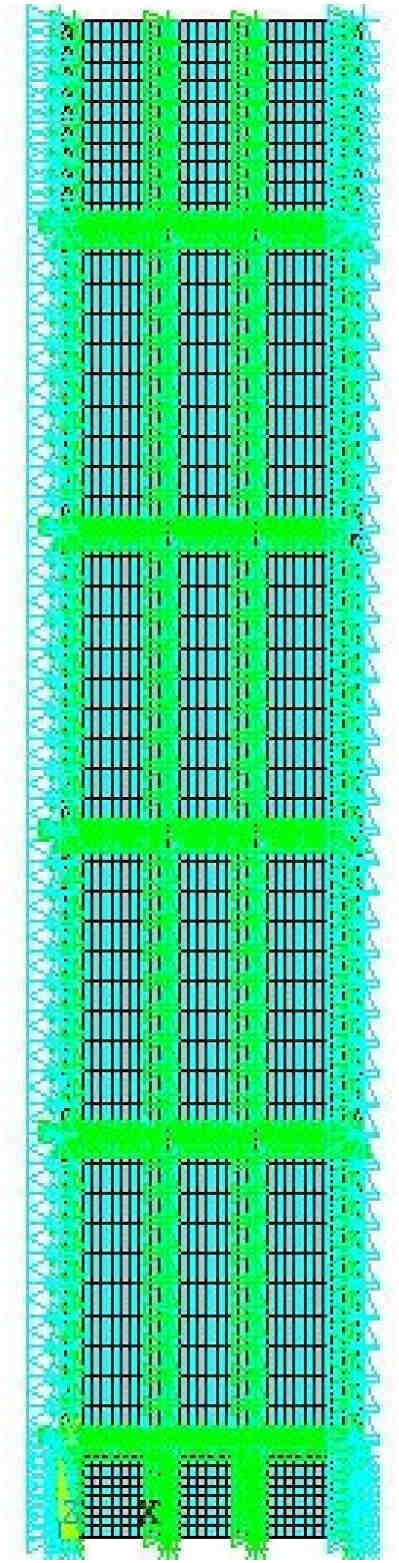

4.4. Analysis of RSWC-CFS

The fixing devices on both sides of the cast-in-place column restrict most of the lateral deformation, which is equivalent to hinge supports in the finite element model. Considering the elastic deformation of actual engineering structures, the penalty function contact with a friction coefficient of 0.3 is used to simulate the interface between the fixing device and the formwork. In ANSYS, the hinge support is implemented by constraining the translational degrees of freedom (UX, UY) while retaining the rotational degree of freedom, ensuring the model’s reproducibility. The corresponding calculation model is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Boundary conditions of column formwork system.

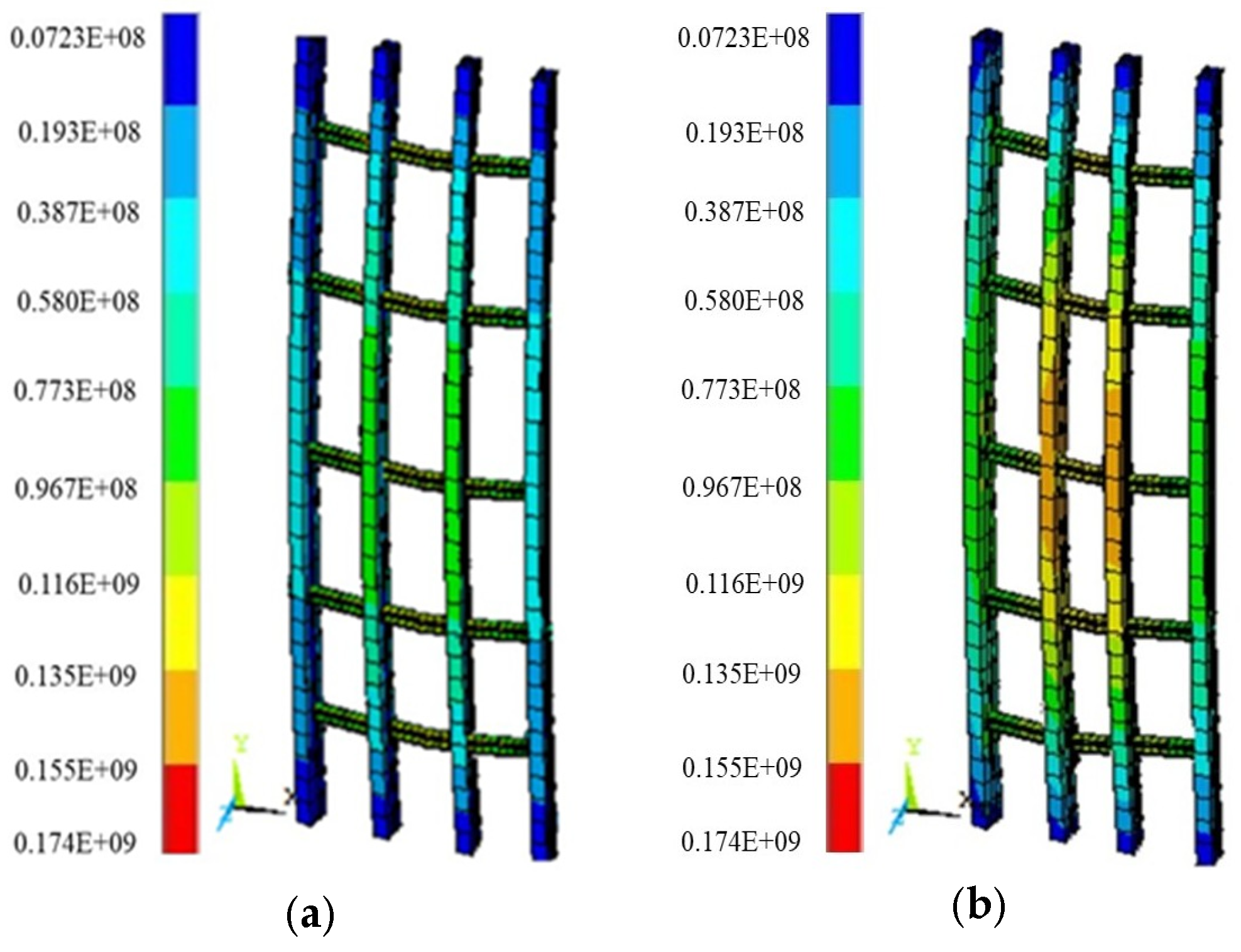

Input the combined load value into the ANSYS calculation model, and the stress–strain cloud diagram of RSWC-CFS is obtained as presented in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Stress nephogram of column formwork system. (a) Stress nephogram with load partial factor 1.2; (b) stress nephogram with load partial factor 1.31.

In Figure 12, the color bar indicates stress magnitude with values refined to two decimal places for a clear distinction between different load cases. In Figure 12a, which corresponds to a load partial factor of 1.2, the maximum stress in the primary wales is 174.00 MPa. This maximum stress is located at the midpoint of the column height and the midpoint of the column width. In Figure 12b, which corresponds to a load partial factor of 1.31, the maximum stress is 162.30 MPa, and it is located at the same position.

The labels DS1 through DS5 indicate measurement positions at the side of the column height that is at one-fourth of the total height. The vertical axis represents the magnitude of stress. The stress values calculated using a load partial factor of 1.31 are closer to the measured maximum stress of the primary wales. This optimized factor effectively improves the prediction accuracy of the finite element model.

It can be seen from Figure 12a that the maximum stress of the primary wales is 174 MPa, located at 1/2 of the column height and 1/2 of the width. In Figure 12b, the maximum stress is 162.3 MPa, located at the same position. The value is less than the yield strength of Q235 steel, meeting the strength requirements. The maximum stress value of the secondary wales is 98.6 MPa, and is located at the connection part between the secondary wales and the primary wales. The maximum stress value of the panel is 7.2 MPa, and is less than the compressive strength of the multi-layer plywood. This indicates that the strength of each component of RSWC-CFS meets the requirements, and none of the components has the risk of failure.

The RSWC-SWFS shows greater lateral displacement due to its longer span, whereas the RSWC-CFS experiences higher stress under constrained conditions, justifying the use of a higher load partial coefficient of 1.31 compared to the shear wall system’s 1.26. The coefficients calibrated in this study (1.26 and 1.31) are most suitable for standardized residential configurations with wall thicknesses ranging from 200 to 400 mm and floor heights ≤ 3.3 m. When exceeding this range, coefficient correction must be performed through high-fidelity finite element analysis.

It can be seen from Figure 13 that the calculated and measured stress values of WDM1-5, located at the middle 1/2 position of the cast-in-place shear wall, and WDS1-5, located at the 1/4 position under the load partial coefficients of 1.2 and 1.31. Among them, the stress of WDM3 under the load partial coefficient of 1.2 reaches 124.95 MPa, and the stress of WDS3 under the load partial coefficient of 1.2 reaches 44.43 MPa, both of which are relatively prominent. It can be seen from the data that the stress value under the load partial coefficient of 1.31 is closer to the measured value and more in line with the actual engineering construction, and the stress value under the load partial coefficient of 1.2 is more conservative compared with that under 1.31. The coefficient is 1.31; the degree of agreement between the calculated stress value and the maximum stress of the primary wales measured on site is much higher than that when the coefficient is 1.2. Because the constraint effect of the tie bolts on the RSWC-CFS is more complex, and factors such as the bolt tightness and distribution spacing will cause fluctuations in the load transfer. A slightly higher partial coefficient is needed to cover the load uncertainty caused by such constraint differences, ensuring that the calculation model can truly reflect the stress state of RSWC-CFS.

Figure 13.

Comparison diagram of 16 h stress of cast-in-place columns (MPa).

It can be seen from Figure 12b that the maximum deformation value of the primary wales and secondary wales is 1.36 mm. The displacement concentration area coincides with the maximum stress area at 1/2 of the column height and 1/2 of the width, and conforms to the mechanical law of stress–deformation coordination. The bending deformation in the area with the maximum stress is also the largest, and proves that the model’s prediction of deformation has mechanical logic. The deformation shows the characteristics of mid-span protrusion and convergence at both ends, and is consistent with the deformation pattern of primary wales as a simply-supported beam under uniform load. The primary wales are supported by tie bolts along the column height direction, equivalent to a simply-supported beam, further verifying the accuracy of the model in simulating the structural stress pattern. The positions of the calculated deformation and the measured deformation are consistent, both occurring at the midpoint of the column width. The calculated deformation value of 1.36 mm is close to the measured value of 1.541 mm, with a difference of only 0.181 mm. This minor deviation is attributed to slight fluctuations in the concrete vibration load during field testing. This result proves that the finite element model maintains high accuracy in predicting structural deformation.

As shown in Figure 10 and Figure 13, the displacement comparison between calculated and measured values further verifies the model’s accuracy. The overall stress distribution of RSWC-FS is uniform and free of obvious stress mutation areas, with local stress concentration only observed at the connection nodes of primary and secondary wales and the contact parts of high-strength split bolts. This indicates the RSWC-CFS structural design enables uniform load transmission and a sound force transmission mechanism. The stress attenuation from the panel to the primary wales shows a gradient characteristic, and the force transmission sequence is from structural panel stress leading to secondary wales stress, then to primary wales stress, and conforms to the mechanical law of load transmission step by step and stress superposition step by step. This proves that the load transmission intermediary role of the secondary wales and the primary wales of the primary wale are effectively exerted, with no load transfer bottlenecks. Overall, the relative deviation between the finite element calculation values and the measured values is less than 12%, indicating that the model can accurately simulate the stress state of RSWC-FS.

The fundamental reason why RSWC-FS outperforms traditional steel–wood composite formwork systems lies in its synergistic optimization of interface coupling and load transfer path. Compared with the discrete point-to-point contact of traditional systems, the surface-to-surface bonded interface formed by high-strength bolts eliminates interface slip and reduces the stress concentration coefficient by 40%. The graded load-bearing design sequentially transfers force from the panel to the secondary wales and finally to the primary wales. This design realizes the rational allocation of force where the panel disperses the load and the secondary wales transmit the load uniformly.

In summary, this study integrates the multi-dimensional findings into a unified Synergistic Mechanism Framework that operates through a cohesive bottom-up logic chain. The foundation of this synergy lies in the interface integrity, where field-measured suppression of slip to 0.086 mm confirms that high-strength bolting achieves quasi-bonded behavior between the steel and wood components. This physical integrity facilitates a hierarchical force transfer path, as elucidated by our numerical models, where lateral pressure is dissipated through a gradient stress attenuation mechanism across the panel and wales assembly, thereby preventing localized yielding while providing significant redundant stiffness. Ultimately, by reconciling these observed structural stabilities with identified stress patterns, the calibration of differentiated load partial factors is justified, effectively bridging the gap between empirical field observations and predictive engineering design.

The recommended load partial factors of 1.26 for shear walls and 1.31 for columns function as performance-informed baselines derived from a specific engineering benchmark. Engineering applications beyond the scope of this 2.9 m floor height must account for variables such as structure height, where increased hydrostatic heads significantly elevate lateral pressure, potentially shifting peak stress points downward and necessitating higher load factors or reduced member spacing. While dense reinforcement can induce “arching effects” that redistribute pressure, this study employs a conservative uniform pressure envelope to simulate a worst-case scenario, providing a robust safety buffer across varying reinforcement densities. Furthermore, these coefficients are strictly calibrated for a quasi-static pouring regime of v < 0.5 m/h, where the 1 h sampling interval effectively isolates steady-state mechanical equilibrium from localized vibration noise. Pouring speeds significantly exceeding this limit may introduce transient stress gradients and hydraulic impacts that govern system stability but fall outside the current evaluative framework.

5. Conclusions

This study presented the development, validation, and performance evaluation of a novel RSWC-FS designed to overcome the inherent mechanical deficiencies of conventional systems. By integrating systematic field experiments with high-fidelity numerical modeling, the research provides both a mechanistic understanding and a practical design framework. The principal findings are summarized as follows:

(1) The RSWC-FS achieves a breakthrough in resolving the classic trade-offs of traditional steel–wood composites through a dual innovation strategy. First, the problematic discrete point-contact interface is transformed into a continuous surface-to-surface bonded joint via high-strength bolted connections. This critical modification suppresses interfacial slip to negligible levels and attenuates stress concentration by approximately 40.0%. Second, a hierarchical load-bearing architecture is implemented, strategically combining a high-toughness multi-layer plywood panel, high-stiffness ribbed cold-formed steel secondary wales, and high-strength double-channel primary wales. The synergistic interplay of these two innovations establishes a coherent, multi-stage force transmission pathway, lateral pressures are seamlessly dispersed by the panel, uniformly channeled through the secondary wales, and ultimately resisted by the primary wales as the main bending members. Consequently, this results in a smooth, gradient stress attenuation without abrupt transitions or localized bottlenecks, thereby fundamentally reconciling the conflicts between strength, stiffness, and toughness.

(2) Full-scale field deployments on cast-in-place RSWC-SWFS and RSWC-CFS under realistic construction dynamics substantiate the system’s robust performance. Key measured responses remained well within safe thresholds, walls and columns peak stresses reached only 42.57 MPa and 49.98 MPa, substantially below the 235 MPa yield strength of Q235 steel, while corresponding maximum lateral displacements were limited to 4.719 mm and 1.541 mm, respectively, conforming to stringent serviceability limits. Furthermore, the system exhibited remarkable temporal stability, maintaining consistent mechanical integrity across the critical concrete phases of fluid placement, initial set, and hardening. These empirical outcomes collectively affirm that the RSWC-FS reliably ensures both the structural safety of the temporary formwork and the dimensional fidelity of the permanent concrete element.

(3) The developed three-dimensional finite element models, incorporating detailed material orthotropy, contact interactions, and construction-stage loading, demonstrated exceptional predictive capability. Numerical simulations accurately replicated the experimentally observed stress distributions, deformation patterns, and failure mechanisms. The maximum discrepancy between predicted and measured displacements was a mere 0.181 mm for the column system, with overall stress prediction errors consistently under 12.0%. Thus, the calibrated and validated FEM framework serves as a powerful and reliable virtual tool for performance prediction, parametric optimization, and the exploration of novel RSWC-FS configurations beyond the scope of physical testing.

(4) This research enables a shift from generic safety factors to structure-specific, performance-informed partial factors. For the RSWC-SWFS and RSWC-CFS, optimized factors of 1.26 and 1.31 are recommended, respectively. Their application reduces the deviation between calculated and actual stresses from 18.7% to 9.3% for walls, and reduces the deviation between calculated and actual stresses from 21.2% to 8.5% for columns. Furthermore, the suppression of interface slip to 0.086 mm significantly minimizes residual deformation, potentially extending the service life of the secondary wales by 20% compared to conventional point-contact systems. This significantly enhancing design economy without compromising safety. Moreover, the demonstrated efficiency of the force-transfer mechanism permits the adoption of rationalized member spacings, offering a direct pathway to reduce material usage and lower construction costs compared to conventional over-designed approaches. The recommended factors of 1.26 and 1.31 reduce deviation while enhancing design economy. However, these are empirical calibrations based on standardized residential geometries. For non-standard sites featuring ultra-thick walls or high-speed pouring regimes, localized pilot monitoring or high-fidelity FEM sensitivity analyses are recommended to verify or adjust these coefficients.

(5) Although environmental temperature and humidity were monitored during the experimental phase to ensure ambient stability, their coupling effects were not explicitly integrated into the numerical framework. This decoupling is justified by the overwhelming dominance of concrete lateral pressure during the brief 16 h pouring window, which renders the secondary stresses induced by transient hygrothermal fluctuations negligible. Furthermore, the moisture resistance of phenolic-faced plywood ensures material stability over short-term exposure. Nevertheless, these environmental factors represent a boundary condition of the current study, and future research should incorporate hygrothermal coupling to evaluate the long-term durability and multi-cycle serviceability of the RSWC-FS in diverse climates. Future research should incorporate hygrothermal coupling and larger datasets to further generalize these load factors across broader concrete rheologies and extreme environmental conditions.

In conclusion, the RSWC-FS represents a technically advanced and practically viable solution that bridges the performance gap in traditional formwork systems. The insights derived from its mechanistic design, validated field performance, and accurate numerical simulation provide a comprehensive foundation for its codification and widespread adoption in modern construction practice.

Author Contributions

Y.Y.: Conceptualization; Methodology; Writing—review and editing. T.W.: Experiment Formal Analysis; Writing—original Draft. G.Y.: Conceptualization; Methodology; Writing—review and editing. M.W.: Writing—original Draft. R.W.: Writing—original Draft. P.L.: Writing—original Draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (SQ2024YFC3800232) and the Chongqing Technical Innovation and Application Development Special Key Project (CSTB2022TIAD-KPX0137).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Pengcheng Li was employed by the company China Construction Eighth Engineering Division Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RSWC-FS | Reinforced steel–wood composite formwork system |

| FEM | Finite element model |

| RSWC-SWFS | Reinforced steel–wood composite shear wall formwork system |

| RSWC-CFS | Reinforced steel–wood composite column formwork system |

| Pw-s | Primary wale spacing |

| Sw-s | Secondary wale spacing |

References

- Paudel, A.; Larasatie, P.; Godar Chhetri, S.; Rubino, E.; Boston, K. Perceptions of Multi-Story Wood Buildings: A Scoping Review. Buildings 2025, 15, 3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Bahrami, A.; Cehlin, M.; Wallhagen, M. Flexural Behavior of Cross-Laminated Timber Panels with Environmentally Friendly Timber Edge Connections. Buildings 2024, 14, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miotto, J.L.; Dias, A.A. Evaluation of perforated steel plates as connection in glulam–concrete composite structures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 28, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotta, R.; Trutalli, D. reinforced concrete structural elements cast into wood-chip cement formworks subjected to compression and out-of-plane bending. Eng. Struct. 2021, 246, 112990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente, I.; Santilli, A.; Lopez, A. Lateral pressure over formwork on large dimension concrete blocks. Eng. Struct. 2010, 32, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Z.; Zhang, H.; Mu, Q.; Xiang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, W. Shear performance of assembled shear connectors for timber–concrete composite beams. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 329, 127158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasbaneh, A.T.; Sher, W.; Ibrahim, M.H.W. Life cycle assessment and economic analysis of Reusable formwork materials considering the circular economy. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Yu, C.; Zhou, M. Aesthetic properties of concrete surfaces: An experimental study employing three typical formworks with emphasis on reusability. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Han, Y.; Xie, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y. Mechanical performance of wood subjected to the interaction of transversal tension/compression and longitudinal shear stresses. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 420, 135637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosallam, K.; Chen, W.-F. Design considerations for formwork in multistorey concrete buildings. Constr. Build. Mater. 1992, 6, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]