Abstract

The construction industry is increasingly challenged by an aging workforce and persistent labor shortages, underscoring the need for automation and the integration of construction robotics. However, the high uncertainty and variability of real construction environments impose significant constraints on robot design and deployment. In particular, accurately estimating the required operational force—without unnecessary overdesign—is essential for ensuring operational safety, energy efficiency, and battery endurance. Conducting on-site experiments that reflect diverse field conditions is often impractical, making simulation-based approaches a viable alternative. This study proposes a simulation-driven method for deriving energy-efficient, task-appropriate operational forces for construction robots. As a case study, an aluminum formwork dismantling operation was modeled in NVIDIA Isaac Sim, and a dataset of environmental variables was generated through random sampling. Sensitivity analysis revealed that the dynamic friction coefficient at the aluminum–aluminum interface had the greatest impact on the required dismantling force. To mitigate this influence, a lubrication strategy was introduced to reduce surface friction. With a 10% safety margin applied, the dismantling operation achieved a 99.5% success probability at an operational force of 50 N-representing an 11.71 N reduction and an 18.97% decrease compared to the non-lubricated scenario. These results demonstrate a practical and evidence-based approach for optimizing operational forces in construction robotics, contributing to reduced energy consumption, improved operational efficiency, and mitigation of construction schedule delays.

1. Introduction

The construction industry has been facing increasing challenges due to workforce aging and chronic labor shortages, which has led to growing interest in automation and construction robotics. Despite this trend, the practical deployment of construction robots remains constrained by the high uncertainty and variability of real construction environments. Site-specific working conditions, heterogeneous surface states, and diverse operational constraints introduce significant variability, making robot design and application particularly challenging. Under such conditions, determining the required operational force of construction robots without excessive overdesign is a critical issue for simultaneously achieving energy efficiency and operational safety.

Appropriate force determination is essential for several reasons. Excessive force application results in unnecessary energy consumption and accelerates hardware wear, thereby reducing system efficiency. Conversely, insufficient force may lead to task failure or interruption, compromising the continuity and reliability of automated operations. Moreover, excessive energy consumption increases the frequency of battery replacement or recharging, which can cause schedule delays. Since construction projects consist of tightly coupled and sequential processes, delays in individual robotic tasks may propagate and affect the overall project timeline. These considerations highlight the need for systematic approaches to identify the forces required for task execution and the key factors influencing them, with the aim of reducing energy consumption in construction robotic systems.

Although experimental validation is essential for robot design, verifying robotic performance under diverse construction conditions through on-site experiments poses significant practical challenges. Construction sites are shared environments where workers and equipment operate concurrently, and robotic malfunctions may result in serious safety incidents. In addition, variations in ground conditions, installation accuracy, and working environments across sites make it difficult to repeatedly conduct experiments under identical conditions. As a result, on-site experimentation is limited in terms of safety and reproducibility, and it is challenging to systematically incorporate environmental variability into empirical validation. These limitations motivate the adoption of simulation-based approaches capable of reflecting the characteristics and diversity of construction environments.

The objective of this study is to determine the optimal operational force required for construction robots to achieve task objectives while considering energy efficiency. In this study, operational force refers to the physical force exerted by a construction robot on a target object to perform a given task, which directly affects task stability, power consumption, and battery endurance. Key factors influencing dismantling tasks are defined as environmental variables, and an environmental dataset reflecting site variability is constructed through probability distribution modeling and random sampling. This dataset is used as input for simulation to estimate the required operational force under different conditions. Sensitivity analysis is then conducted to identify the variables that have the greatest influence on the required force. Based on the analysis results, force-reduction strategies targeting these influential variables are formulated and validated through additional simulations. Finally, a distribution-based method for determining the optimal operational force is proposed.

An aluminum formwork removal task is adopted as a case study to demonstrate the applicability of the proposed approach. Aluminum formwork removal involves repetitive handling and transportation of heavy components, requiring substantial physical effort from workers. Through this case study, it is shown that the proposed simulation-based framework can derive the optimal force required for task execution while accounting for energy efficiency. The results indicate that the proposed method can reduce power consumption and extend battery operating time, thereby mitigating schedule delays caused by battery depletion in construction robotic operations.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews previous studies related to construction robotics and force determination. Section 3 describes the overall procedure for determining the optimal operational force, including variable definition, random sampling, simulation, sensitivity analysis, and energy-saving strategy validation. Section 4 presents a simulation-based case study of automated aluminum formwork removal using NVIDIA ISAAC SIM to demonstrate the application of the proposed method. Finally, Section 5 discusses the limitations of this study and directions for future research.

2. Previous Studies on Force Determination for Robot Design

For robotic systems to perform diverse tasks in a stable and reliable manner, it is essential to accurately design and control task-specific forces. Accordingly, extensive research on force determination and optimization for robot design has been conducted across a wide range of application domains, including agriculture, manufacturing, service robotics, and mobile robotics. Table 1 summarizes representative studies on force determination for robot design published between 2015 and 2025.

Table 1.

Summary of previous studies on force determination for robot design.

Previous studies have proposed various force design strategies to minimize potential damage to target objects and ensure operational stability during grasping and contact-based tasks. In particular, research on soft grippers and harvesting end-effectors has focused on deriving minimum stable grasping forces by considering object size, material properties, and frictional characteristics, thereby preventing object damage [1,2]. These studies have demonstrated the validity of force design approaches through contact force distribution, friction cone constraints, and experimental or simulation-based verification.

In the fields of mobile and humanoid robotics, numerous studies have investigated the optimal distribution of ground reaction forces and joint torques to achieve stable locomotion under uneven terrain and dynamic environments [3,4,5]. These studies incorporated terrain uncertainty, external disturbances, and modeling errors into force control and trajectory optimization frameworks, with some explicitly considering actuator torque and power limitations as constraints. The primary objective of such approaches has been to enhance robot stability and robustness during motion.

Meanwhile, in process robotics such as grinding and polishing, force design studies have aimed to improve task quality by maintaining constant contact forces and suppressing vibration [6,7]. These studies derived optimal working forces by accounting for contact models, surface characteristics, and dynamic behavior, and proposed passive or active control mechanisms to prevent force overshoot.

More recently, force determination methods that account for environmental uncertainty and complex contact conditions have been proposed using simulation-based or learning-based approaches [8,9,10,11]. These studies focus on approximating or learning unknown environmental models, friction variations, and external disturbances to improve force control performance, and have introduced design frameworks based on differentiable simulators or reinforcement learning.

Despite these advances, most existing studies have been conducted under relatively controlled environments or single-task conditions. Systematic consideration of environmental variability at the distribution level, as well as joint incorporation of energy efficiency into force reduction strategies, remains limited. This limitation is particularly pronounced in construction environments, where working conditions and environmental variables vary significantly from site to site, yet relatively few studies have addressed force determination methods that explicitly reflect such variability.

Based on these observations, this study proposes a simulation-based framework for force determination that accounts for environmental diversity and uncertainty in construction sites. By defining probability distributions of environmental variables and simulating a wide range of task conditions, the proposed approach aims to derive optimal operational forces that simultaneously consider energy efficiency and operational safety.

3. Simulation-Based Framework for Determining Optimal Forces in Construction Robotics

This study aims to derive the optimal operational force required for construction robots to perform tasks while achieving energy efficiency, by explicitly considering environmental variables that influence force requirements. To this end, environmental uncertainty is modeled using probability distributions, and a simulation-based analysis is conducted to generate force distributions under diverse working conditions. Based on the characteristics of these distributions, a framework for determining the optimal operational force is proposed.

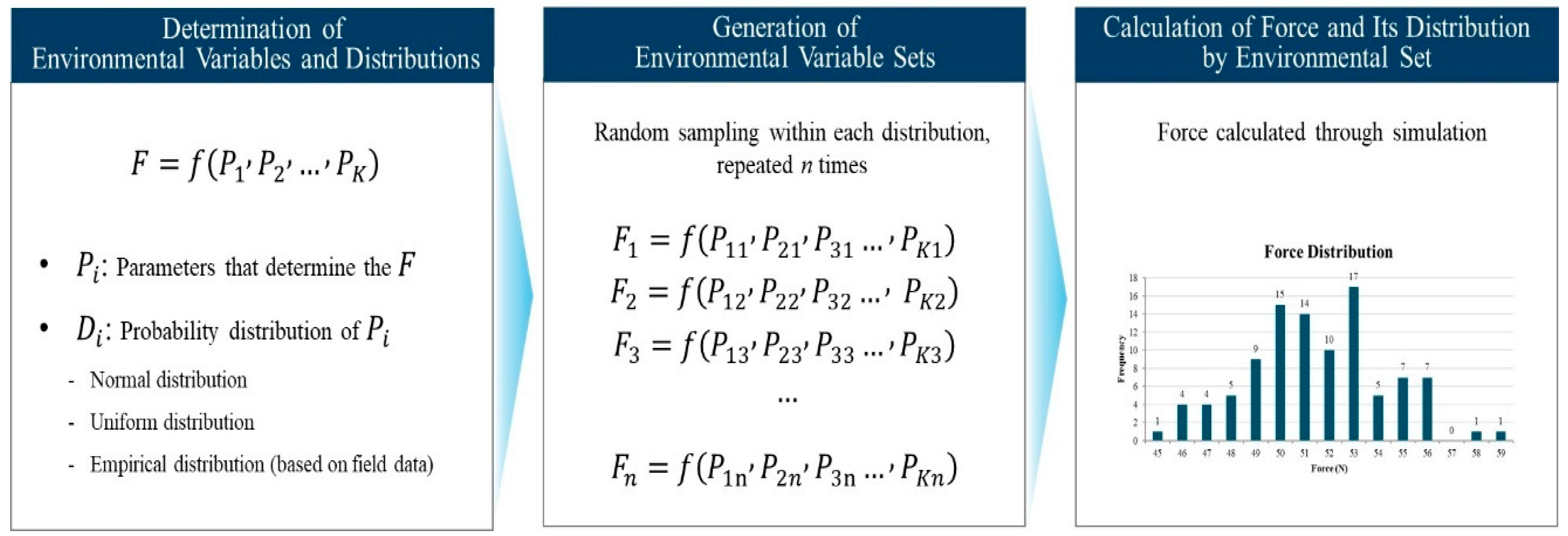

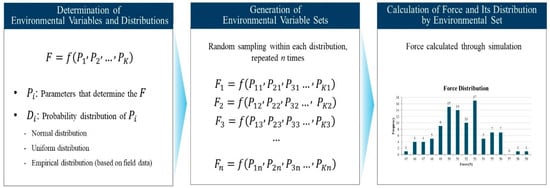

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework of the proposed approach, from the definition of environmental variables to the generation of force distributions. First, key environmental variables that affect the required operational force are identified, and the functional characteristics and value ranges of each variable are defined. Probability distributions are then assigned to individual variables, and random sampling is performed to construct an environmental variable dataset that reflects diverse site conditions. Using the generated combinations of environmental variables as input, task simulations are conducted to calculate the required operational force under each condition, thereby constructing a force dataset corresponding to environmental variability.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for force determination and environmental dataset generation.

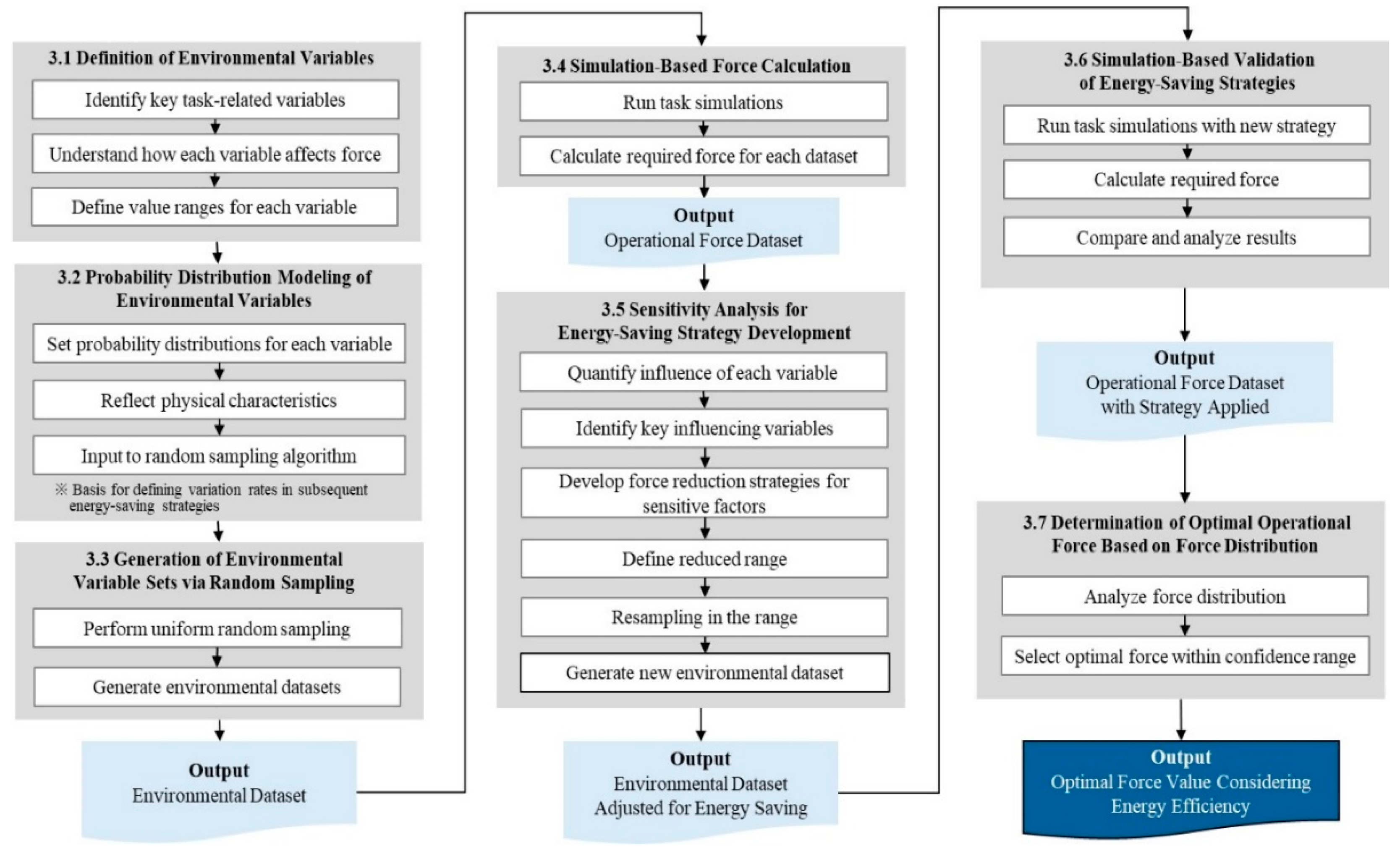

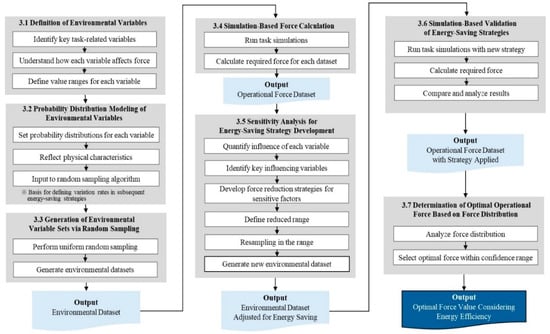

Figure 2 presents the detailed workflow of the proposed simulation-based procedure for optimal operational force determination. Based on the simulation results, sensitivity analysis is performed to quantify the influence of individual environmental variables on the required force and to identify key influencing factors. Energy-saving strategies are subsequently developed by targeting variables with the greatest impact on force and energy consumption. New environmental datasets are generated by resampling within the reduced ranges defined by these strategies, and the same simulation procedure is applied to compare the required forces before and after strategy implementation. Finally, the force distributions obtained from the simulations are statistically analyzed to determine the optimal operational force within a confidence range that simultaneously satisfies operational stability and energy efficiency. By incorporating environmental variability at the distribution level, the proposed framework provides a practical criterion for determining operational force in construction robotics, while avoiding excessive overdesign and improving energy efficiency under diverse site conditions.

Figure 2.

Simulation-based workflow for optimal operational force determination. (※: This symbol indicates an important remark).

To clarify the procedural flow of the proposed framework, the overall methodology can be summarized as a sequential seven-step workflow. First, key task-related environmental variables are identified and their physical influence on the required operational force is defined (Section 3.1). Second, probability distributions are assigned to these variables to represent environmental uncertainty (Section 3.2). Third, environmental variable sets are generated through random sampling based on the defined distributions (Section 3.3). Fourth, simulation-based force calculation is performed for each environmental dataset to obtain the corresponding operational force (Section 3.4). Fifth, sensitivity analysis is conducted to quantify the influence of individual variables and identify key factors for force reduction (Section 3.5). Sixth, energy-saving strategies are applied and validated through re-simulation under modified variable distributions (Section 3.6). Finally, the optimal operational force is determined based on the resulting force distributions and confidence levels (Section 3.7). This structured workflow enables readers to clearly follow and reproduce the proposed procedure.

3.1. Definition of Environmental Variables

This study defines key environmental variables that determine the operational force required during task execution in order to improve the energy efficiency of construction robots, and proposes a simulation-based approach for optimal force determination based on these variables. In construction tasks, the required operational force is influenced by various factors, including material properties of the target object, contact conditions, and the surrounding working environment. As these conditions vary across sites and tasks, the required force also changes accordingly. Therefore, this study formulates the operational force not as a fixed deterministic value, but as a function of multiple stochastic environmental variables, which are used as input parameters for simulation.

The operational force refers to the physical force exerted by a construction robot on a target object to achieve a given task objective, and can be expressed as a function of environmental variables as follows:

where denotes an environmental variable that influences the required operational force. Each variable is defined as a random variable with an associated probability distribution (e.g., normal, uniform, or empirical distributions) to reflect uncertainty in environmental conditions.

As an illustrative example, the operational force can be represented as a function of variables such as:

where represents the static and dynamic friction coefficients of the target object, denotes the contact area between the robot and the target object during task execution, and represents the torque generated by the robot’s actuation system. Additional variables, such as ambient temperature and surface condition of the object, may also be included to reflect task-specific environmental characteristics. Since these variables vary dynamically under real construction site conditions, the operational force is treated as a stochastic function rather than a deterministic scalar.

The environmental variables considered in this study were selected based on experimental observations and analyses of previous studies, and represent major factors that repeatedly influence force requirements in construction tasks. The definition of environmental variables follows a three-step process: (1) identification of relevant variables, (2) characterization of how each variable affects the operational force, and (3) specification of value ranges for each variable. This process forms the foundational basis for constructing simulation input data, conducting sensitivity analysis, and developing energy-saving force reduction strategies.

3.2. Probability Distribution Modeling of Environmental Variables

Each environmental variable is defined as a stochastic variable that follows a statistical distribution rather than a fixed single value, in order to reflect the heterogeneous working conditions and inherent uncertainty across construction sites. In this study, appropriate probability distributions are assigned to individual environmental variables by considering their physical characteristics and practical applicability in construction environments, thereby enabling the construction of a realistic simulation setting.

For example, variables that directly affect contact conditions, such as friction coefficients and adhesion forces, exhibit significant variability depending on measurement conditions, surface states, and usage frequency. Considering these characteristics, such variables are modeled using uniform distributions within predefined ranges. This modeling choice represents a conservative assumption that avoids bias toward specific values and allows a wide range of working conditions to be reflected in the simulation.

The probability distribution modeling of environmental variables serves multiple purposes. First, it ensures physical consistency of the simulation environment by reflecting the variability observed in experimental data and material specifications. Second, probabilistic sampling enables the reproduction of diverse task conditions, thereby improving the representativeness of the analysis beyond specific cases. Third, the defined distributions provide a quantitative basis for determining variable reduction ratios in subsequent energy-saving strategy development, allowing for systematic comparison of effects before and after strategy application.

The defined probability distributions are subsequently used to generate diverse combinations of environmental variables through random sampling, which enhances the flexibility of the simulation-based analysis and supports generalization of the results. In this study, environmental variable datasets were automatically generated using random sampling implemented in a Python 3.11.9-based environment. For variables following uniform distributions, the numpy.random.uniform function was used to generate simulation input values. The resulting datasets reflect a wide range of environmental variations that may occur in real construction tasks.

Accordingly, this step constitutes a critical component of the proposed framework, as it directly influences the accuracy and reliability of subsequent simulation execution, sensitivity analysis, and energy-saving strategy development, ultimately determining the precision of optimal operational force estimation.

3.3. Generation of Environmental Variable Sets via Random Sampling

In this study, probabilistic sampling techniques were employed to generate diverse combinations of environmental variables for simulation-based analysis of task execution. Random sampling enables a wide range of working conditions that may occur on construction sites to be represented, and higher degrees of randomness have been reported to increase sample diversity and improve the statistical stability of simulation results [12,13]. Moreover, probabilistic approaches provide an effective means of generating diverse conditions in situations where sufficient real-world data are difficult to obtain [14,15].

Based on the predefined probability distributions and value ranges of environmental variables, random sampling was performed to construct simulation input datasets. The primary objective of this sampling process was to generate representative combinations of environmental conditions that reflect variability in real construction tasks, while avoiding bias toward specific scenarios. Since the reliability of simple random sampling can be highly sensitive to the selected variable ranges, particular attention was paid to defining physically plausible ranges for each variable prior to sampling [16].

The random sampling code is presented in Appendix B Algorithm A1, titled “Pseudo-code for generation of environmental parameter sets via random sampling”. Environmental variable sampling was implemented in a Python-based environment, and the random seed was fixed to ensure reproducibility of the simulation results. In this study, the total number of samples was set to 100, such that identical sets of environmental variable combinations could be regenerated in repeated experiments. Under static conditions, variables such as static friction coefficients and adhesion forces were sampled using uniform distributions. For each sampled case, the dynamic friction coefficient was subsequently derived by randomly applying a reduction ratio within the range of 0.70–0.80, thereby modeling the physical principle that dynamic friction coefficients are smaller than their static counterparts.

The resulting combinations of environmental variables were organized into datasets and used as direct input for subsequent simulations. This random sampling-based construction of environmental variable sets aims to ensure both environmental diversity and physical plausibility, and provides the foundational data for simulation execution and force distribution analysis in the proposed framework. The results of the random sampling procedure are presented in Appendix A.1 titled “Sampled Environment Parameters via Random Sampling”.

3.4. Simulation-Based Force Calculation

In this study, simulation-based force calculation was performed using combinations of environmental variables generated through probability distribution modeling and random sampling. The simulations were conducted to quantitatively estimate the operational force required for task execution under different environmental conditions, and to derive force distributions corresponding to variations in environmental variables. The resulting force data serve as the basis for identifying influential variables and for subsequent development of energy-saving strategies. The results of the simulation-based force calculation are presented in Appendix A.2 titled “Force results before applying the energy-saving strategy”.

Construction tasks require more than simple force application, as robotic manipulation and posture control must be adapted to the geometry and condition of the target object. To reflect these characteristics, interactions between the robot and construction objects, as well as changes in robot posture, were explicitly implemented within the simulation environment. Through this process, the required operational force was calculated for each environmental condition. The calculated force results were subsequently used as input data for sensitivity analysis and for validating energy-saving force reduction strategies.

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis for Energy-Saving Strategy Development

This section identifies key environmental variables that significantly influence the required operational force based on simulation results and derives design strategies for force reduction from an energy-saving perspective. This step plays a central role in moving beyond overly conservative robot design approaches, while maintaining operational stability and simultaneously improving energy efficiency and practical applicability.

In this study, the Pearson correlation coefficient was employed to quantitatively evaluate the influence of individual environmental variables on the required operational force. The Pearson correlation coefficient measures the strength of linear relationships between two variables on a scale from −1 to 1, where larger absolute values indicate stronger associations. A positive correlation indicates that the required force increases as the variable increases, whereas a negative correlation indicates that the required force decreases as the variable increases [17].

The Pearson correlation coefficient was selected because it enables intuitive comparison and interpretation of both the direction and relative importance of individual variables. In simulation-generated datasets, capturing overall increasing or decreasing trends is often more directly useful for developing energy-saving design strategies than modeling complex nonlinear interactions. In addition, this method is computationally simple and provides stable results even when the sample size is limited [18].

Based on the correlation analysis, variables with a strong influence on the required operational force were identified, and physically grounded design strategies were derived to effectively reduce energy consumption. For example, reducing friction coefficients by approximately 30–40% through lubrication was found to significantly decrease the required force under identical task conditions. Such reductions can lower battery consumption, extend continuous operating time, and mitigate mechanical fatigue during repetitive tasks. Similarly, reducing adhesion forces through surface treatment methods, such as removal of cement residue or high-pressure cleaning, was shown to decrease the initial force threshold and increase the likelihood of successful dismantling.

The derived force-reduction strategies are subsequently applied by adjusting the ranges of the corresponding environmental variable distributions and reintroducing them into the simulation framework. By comparing force distributions before and after strategy implementation, the energy-saving effects are quantitatively validated. Through this iterative analysis process, the proposed framework effectively links sensitivity analysis results to practically applicable energy-saving design strategies.

3.6. Simulation-Based Validation of Energy-Saving Strategies

The simulation-based validation stage was conducted to examine whether the variable reduction strategies derived in the previous section effectively contribute to reducing the required operational force and improving energy efficiency. Rather than limiting the study to strategy formulation, this work directly compares force distributions before and after strategy implementation under identical simulation conditions to evaluate the practical effectiveness and reliability of the proposed strategies.

To this end, new probability distributions of environmental variables were defined by incorporating the proposed reduction strategies, and random sampling and simulation were repeated using the same number of samples as in the baseline scenario. In this process, only the distribution ranges of key variables with significant influence on energy consumption, such as friction coefficients and adhesion forces, were adjusted, while all other conditions were kept constant in order to isolate the effect of strategy application. The results of the simulation-based validation of energy saving strategies are presented in Appendix A.3 titled “Force results after applying the energy-saving strategy”.

Simulation results obtained before and after strategy implementation were compared based on statistical metrics, including the mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum values, and confidence intervals of the required operational force. This comparison enables evaluation of not only shifts in the central tendency and dispersion of force distributions, but also the mitigation of extreme force requirements. Such analysis aims to simultaneously verify the potential for energy savings through force reduction and the preservation of operational stability.

The proposed validation procedure is not limited to a single scenario, but follows a feedback-based structure in which the same analysis can be iteratively applied after adjusting variable distributions. Through this process, the proposed approach can be generalized as an iterative design framework comprising strategy formulation, simulation-based validation, and design refinement. This framework offers flexibility for application to a wide range of construction robotic systems and task conditions.

3.7. Determination of Optimal Operational Force Based on Force Distribution

The primary objective of this study is to determine the optimal operational force that enables construction robots to perform tasks under diverse environmental conditions while maintaining energy efficiency. Through simulation execution, sensitivity analysis, and the application of force reduction strategies, the resulting force data are obtained in the form of probability distributions rather than single deterministic values. These distributions reflect the uncertainty and variability arising from different combinations of environmental variables. Accordingly, this section statistically analyzes the force distributions derived from the simulation results and determines the required operational force at specified confidence levels.

Distribution-based force analysis provides a rational basis for minimizing energy consumption while avoiding overly conservative design approaches that rely solely on maximum force values. Instead of adopting the upper bound of the force distribution as the final design value, this study determines the optimal operational force within a confidence interval by simultaneously considering distribution characteristics and task stability requirements. Here, the optimal operational force refers to the force level that satisfies the required operational stability under given task conditions while minimizing energy consumption. The reduction in operational force directly lowers the mechanical load applied to the actuator, thereby decreasing the required torque and overall power consumption. This relationship can be described by the equation where is the power, is the force, and is the velocity. As the required force decreases, so does the electrical power input, resulting in reduced current draw and heat generation. Ultimately, this contributes to extended battery life and improved energy efficiency. These benefits are particularly critical in mobile construction robotics, where battery capacity and recharging opportunities are limited, and continuous operation is essential for maintaining productivity on-site.

This distribution-based approach to optimal force determination offers several advantages. First, it allows flexible adjustment of operational force in response to changes in environmental conditions, supporting informed decisions on robot hardware specification and energy budget planning. Second, it provides a foundational framework for standardized force design in automated construction tasks characterized by repetitive operations. Third, by adopting a statistical design approach based on simulation and empirical data, the proposed method can be extended toward modular robot design frameworks capable of adapting to a wide range of construction environments.

Overall, this approach is not limited to a specific task scenario, but offers a generalized design framework applicable to a broad class of repetitive construction operations. The proposed methodology thus provides a scalable and extensible basis for determining energy-efficient operational forces in construction robotics under diverse and uncertain working conditions.

4. Case Study

The objective of this study is to propose a generalized methodology for determining optimal operational forces in construction automation tasks while considering energy efficiency. To examine how the proposed simulation-based force determination framework can be applied to real construction operations, an aluminum formwork removal task was selected as a case study.

Aluminum formwork removal is characterized by high repetitiveness and significant variability in working conditions, with required operational forces strongly influenced by friction, adhesion, and contact conditions. Owing to these characteristics, this task represents a typical construction automation scenario in which excessive force design can lead to unnecessary energy consumption, whereas insufficient force may result in task failure. Accordingly, aluminum formwork removal provides a suitable case for validating the necessity and effectiveness of a force distribution-based approach.

The purpose of this case study is not to propose an optimal removal strategy for a specific dismantling task, but to evaluate the applicability and effectiveness of the proposed force determination procedure across diverse working conditions. Through this case study, the potential for extending the proposed methodology beyond aluminum formwork removal to other repetitive construction automation tasks are assessed.

4.1. Determination of Optimal Operational Force Based on Force Distribution

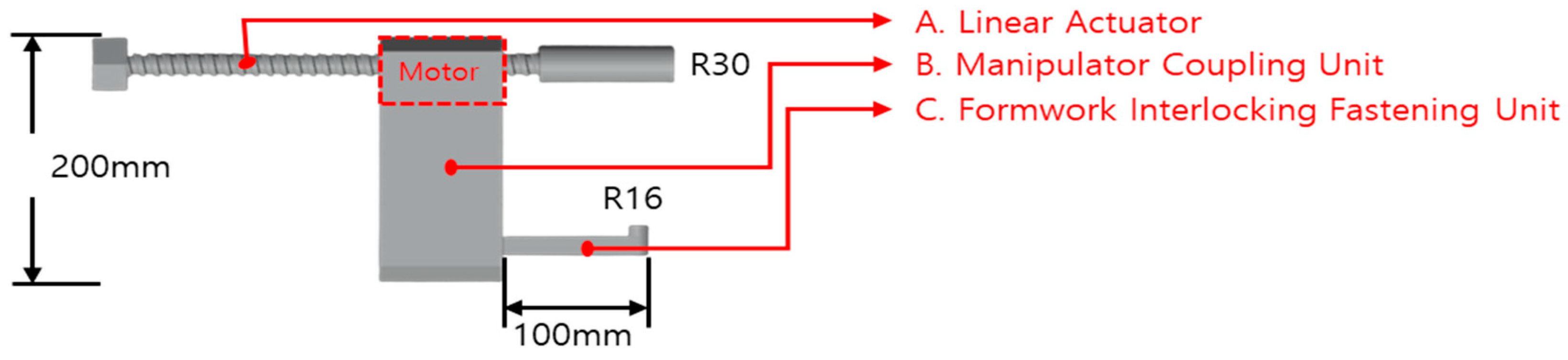

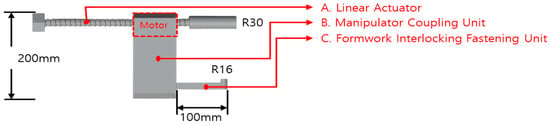

In this study, an automated aluminum formwork removal task was selected as a case study for deriving the required operational force through simulation. The configuration of the automation device applied to this task is presented in Table 2 and Figure 3. The device was designed to transmit the tensile force required for aluminum formwork removal through a robotic system.

Table 2.

Components of the aluminum formwork removal automation device.

Figure 3.

Structure of the aluminum formwork removal automation device.

The automation device consists of three main components. A. Linear Actuator serves as the primary actuation unit that directly generates the tensile force required to pull the aluminum formwork during the removal process. The actuator converts motor-driven rotational motion into axial force through a lead screw mechanism. B. Manipulator Coupling Unit connects the linear actuator to the fastening unit and transmits rotational motion, thereby coordinating the operation between components. C. Formwork Interlocking Fastening Unit is inserted into the removal hole of the aluminum formwork and mechanically interlocks with the formwork, providing stable fixation between the device and the formwork during the removal process and ensuring operational stability.

In conventional aluminum formwork removal operations, workers remove fastening pins and apply manual force to separate the formwork panels. Each aluminum formwork panel weighs approximately 26.5 kg, and in typical apartment construction sites where multiple panels are installed sequentially, the same force-intensive task must be repeatedly performed. This repetitive manual operation leads to accumulated worker fatigue and increased risk of safety accidents, while differences in individual skill levels also make it difficult to ensure consistent removal quality.

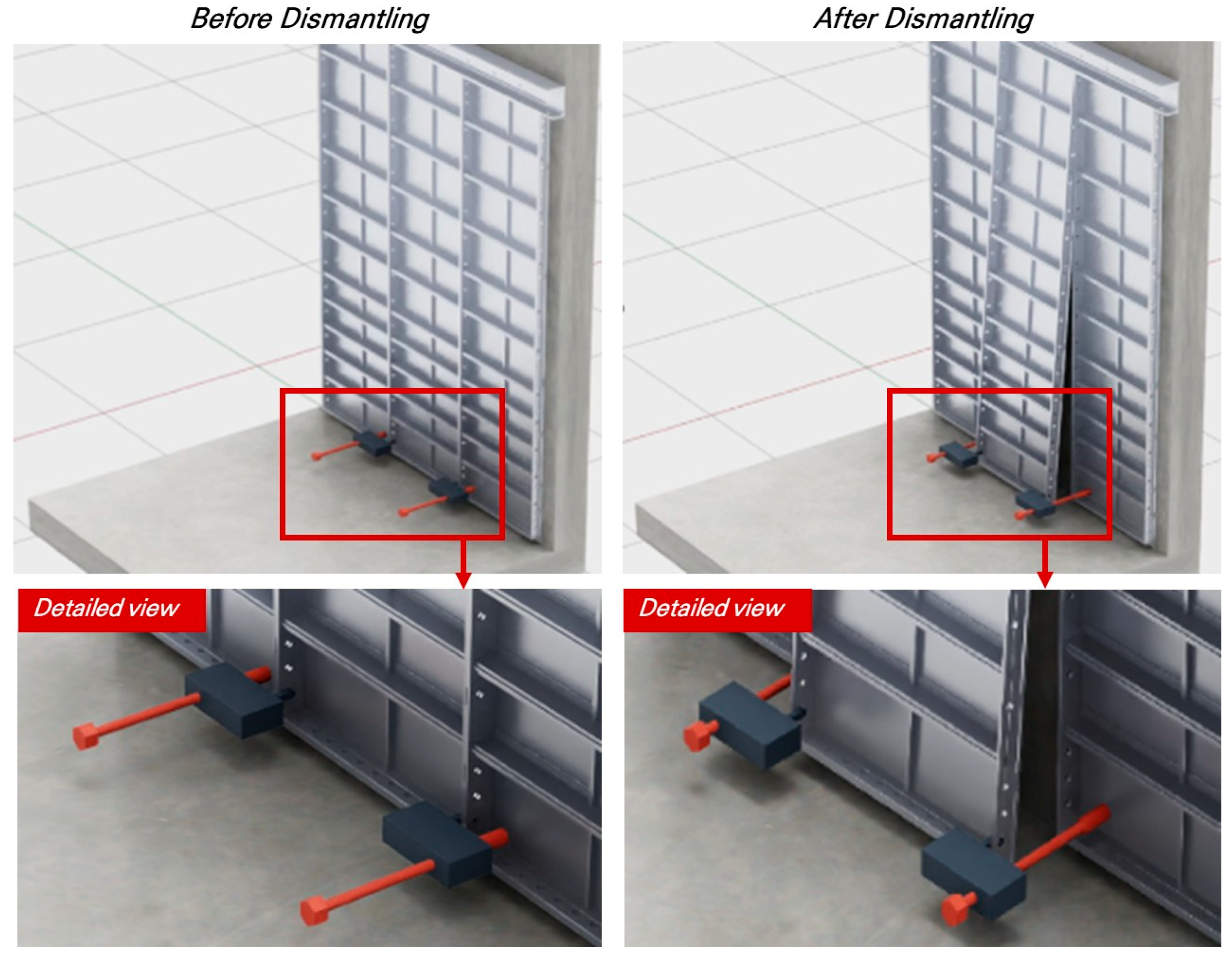

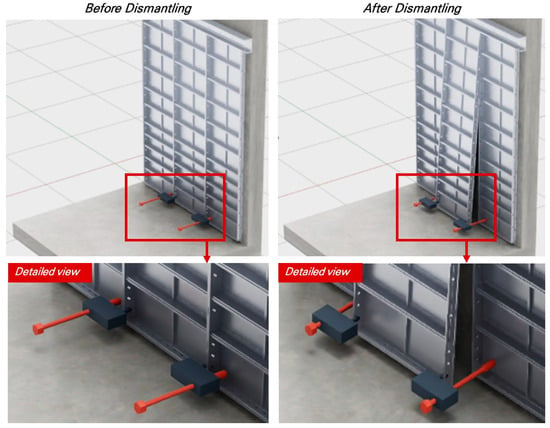

To address these limitations of conventional removal methods, this study reconstructs the aluminum formwork removal task as a robot-oriented automation scenario and aims to derive the optimal operational force required for task execution through simulation-based analysis. Figure 4 illustrates an automated removal process in which three aluminum formwork panels are installed, and the central panel is removed. The left image shows the formwork interlocking fastening unit engaged with the removal hole of the aluminum formwork, while the right image depicts the separation of the lower part of the formwork as the lead screw mechanism is actuated by the internal motor.

Figure 4.

Automated aluminum formwork removal process.

This automated aluminum formwork removal scenario offers several advantages, including the reduction in manual labor demands in repetitive tasks and the achievement of more consistent removal quality. Furthermore, by transforming a labor-intensive removal process into a robot-compatible automation task, worker safety can be improved and productivity and operational efficiency in construction automation environments can be enhanced.

4.2. Simulation-Based Determination of Optimal Operational Force

4.2.1. Definition of Environmental Variables

This study aims to derive the optimal operational force for aluminum formwork removal by reflecting diverse environmental conditions through simulation-based analysis. This section defines the key physical variables that influence the required operational force during the removal process and explains how these variables are incorporated into force determination.

During aluminum formwork removal, the required operational force is primarily governed by frictional forces and adhesion forces. Frictional forces arise under two contact conditions. The first occurs at the lateral contact surfaces between adjacent aluminum formwork panels, while the second occurs at the interface between the bottom of the aluminum formwork and the concrete floor. Aluminum formwork panels are installed sequentially and fastened using pins to support concrete placement; during removal, relative motion between adjacent panels is induced following pin removal, generating frictional resistance. In addition, as the removal progresses from the lower section, frictional forces also develop between the aluminum formwork and the concrete floor.

The second force component considered is the adhesion force between the aluminum formwork and concrete. Adhesion force is a critical physical variable that determines the initial operational force required for removal and must be considered in robot design [19]. This force originates from bonding effects that develop during the concrete curing process and tends to increase with longer curing times. Moreover, repeated use of formwork can lead to accumulation of surface residues and increased surface roughness, which further enhances adhesion.

Based on these physical characteristics, this study defines friction coefficients and adhesion force as the primary environmental variables influencing the operational force required for aluminum formwork removal. The operational force for the removal task is formulated as:

where the variables are defined as follows:

- : static friction coefficient between aluminum–aluminum;

- : static friction coefficient between aluminum–concrete;

- : dynamic friction coefficient between aluminum–aluminum;

- : dynamic friction coefficient between aluminum–concrete;

- : adhesion force between aluminum formwork and concrete (N).

Since these environmental variables exhibit significant variability depending on actual removal conditions, the following section specifies probability distributions for each variable and applies probabilistic sampling to generate simulation input datasets.

4.2.2. Probability Distribution of Environmental Variables

The operational force required for aluminum formwork removal varies significantly depending on site conditions and environmental changes. To enable removal under diverse construction conditions, this study defines reasonable ranges and probability distributions for key environmental variables and generates combinations of environmental conditions through random sampling. In this case study, friction coefficients and adhesion force are selected as the primary environmental variables, and the sampling ranges for each variable are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Sampling ranges of environmental variables used in the simulation.

- Friction coefficients

Frictional forces during aluminum formwork removal primarily arise from contact between the bottom of the formwork and the concrete floor, as well as from contact surfaces between adjacent aluminum formwork panels installed in sequence. These frictional interactions directly influence the operational force required for removal. Accordingly, both static and dynamic friction coefficients are considered in this study. Since actual removal involves an initial static phase followed by sustained relative motion, both coefficients are incorporated into the force model.

The static friction coefficient between aluminum–aluminum contact surfaces was set within the range of 1.05–1.35 based on material property data reported in the literature [20]. Direct experimental data for aluminum–concrete friction coefficients are limited; therefore, this study references friction coefficients for steel–concrete interfaces, which exhibit similar contact characteristics, and adopts a range of 0.45–0.60 as reported in previous experimental studies [21].

The dynamic friction coefficient was derived as 70–80% of the corresponding static friction coefficient. This ratio follows commonly reported relationships in friction coefficient comparison studies and represents a conservative yet physically plausible assumption [22]. Dynamic friction coefficients were modeled using uniform distributions within this range.

- Adhesion force

Adhesion force is a key variable that directly affects the total operational force required for removal, and its magnitude tends to increase due to changes in formwork surface conditions caused by repeated use. When cement paste or residues adhere to the aluminum formwork surface in contact with concrete, surface roughness increases, which in turn enhances interfacial adhesion between materials [23]. In addition, factors such as the number of reuse cycles, cleaning practices, and surface treatment conditions significantly influence adhesion behavior.

To reflect these site-specific conditions in the simulation, the probability distribution of adhesion force was defined based on ranges reported in previous experimental studies on aluminum formwork removal. In [24], experiments were conducted under conditions involving post-removal scraping cleaning and application of release agents, and the maximum adhesion force was reported as 82.9 N for a 1200 mm-high aluminum formwork after nine reuse cycles. Given the similarity of these experimental conditions to the present study, and considering a formwork height of 2400 mm, the adhesion force range was conservatively extended to 100–170 N and modeled using a uniform distribution.

4.2.3. Generation of Environmental Variable Sets via Random Sampling

Based on the ranges and probability distributions defined in Section 4.2.2, environmental variable sets were generated through random sampling and used as input for simulation. The static friction coefficient between aluminum–aluminum contact surfaces () was sampled from a uniform distribution within the range of 1.05–1.35, while the static friction coefficient between aluminum and concrete () was sampled from a uniform distribution within the range of 0.45–0.60. The adhesion force () was sampled using the same approach within the range of 100–170 N.

For each sampled case, the dynamic friction coefficient was calculated as 70–80% of the corresponding static friction coefficient, thereby accounting for the transition from static to dynamic contact conditions. Using this procedure, a total of 100 combinations of environmental variables were generated, with each combination representing an independent working condition in the ISAAC SIM 4.5.0 environment. Accordingly, the 100 environmental variable sets correspond to 100 distinct aluminum formwork removal scenarios.

This random sampling-based construction of environmental variable sets was intended to reflect variability in site conditions and uncertainty in formwork states that may arise in real construction environments. The resulting datasets enable systematic analysis of force distribution characteristics under diverse frictional and adhesion conditions in the subsequent simulation-based evaluation.

4.2.4. Simulation Setup and Force Calculation

In this section, simulations were conducted in the NVIDIA ISAAC SIM environment to calculate the operational force required for aluminum formwork removal. ISAAC SIM provides a physics-based simulation engine that enables accurate modeling of interactions between robots and objects, and supports parallel simulation for efficient analysis under diverse environmental conditions [25]. By leveraging USD and PhysX-based physics engines, changes in object posture, contact conditions, and force transmission processes can be consistently modeled within a unified physical framework [26]. The key physical parameters used in the simulations are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Physical and simulation parameters in ISAAC SIM.

The mass of the aluminum formwork was specified as 26.5 kg to reflect actual site conditions. Material properties were defined based on standard reference values, with densities of 2700 kg/m3 for aluminum and 2400 kg/m3 for concrete. Gravitational acceleration was set to the standard Earth gravity of 9.8 m/s2, and built-in Aluminum and Concrete materials provided by ISAAC SIM were used to represent material behavior.

Isaac Sim supports a feature called Physics Materials, which allows users to define mechanical properties for simulation objects. We created separate material definitions for aluminum and concrete, specifying parameters such as Density, Static and dynamic friction coefficients, and Friction combine mode. These properties were assigned to simulation objects using the built-in Physics Material Editor. The Friction Combine Mode setting was applied to control how interacting surfaces compute the effective friction coefficient during contact. We selected the “average” mode to reflect real-world contact behavior under typical construction site conditions.

Isaac Sim uses NVIDIA PhysX 5, which models contact dynamics using classical mechanics and the Coulomb friction law. The frictional force is computed as:

- : tangential friction force;

- : friction coefficient;

- : normal contact force.

Two key contact scenarios were modeled (Table 5):

Table 5.

Summary of normal force sources and friction force equations by contact pair.

For aluminum–aluminum side contact, the simulator generates a restoring force in response to slight interpenetration, simulating the real-world wedging effect observed between tightly fitted panels. This restoring force acts as the normal force in the Coulomb friction model. This contact pressure acts as the normal force in the Coulomb model.

To realistically simulate contact behavior during the removal process, the restitution coefficient was set to 0.05, considering the low elastic characteristics of aluminum–concrete interactions. In addition, the Continuous Collision Detection (CCD) option was enabled to prevent numerical artifacts such as interpenetration or abnormal rebound during contact events.

Since PhysX does not natively support adhesion force modeling due to its complex dependence on chemical bonding, surface roughness, and curing conditions, we implemented adhesion behavior manually. An adhesion force vector was applied to the aluminum panel surface in the direction opposite to the pulling force, simulating the initial resistance caused by bonding between the formwork and the concrete wall. This force was uniformly distributed across the contact area (600 mm × 2450 mm) with a magnitude ranging from 100 to 170 N. As the panel was gradually separated, the contact area decreased, and the adhesion force was proportionally reduced to reflect realistic detachment behavior. Simulation logs confirmed that adhesion force decreased as displacement increased.

To ensure numerical stability and accurate contact resolution, the number of PhysX solver iterations was set to the maximum value of 255 for both position and velocity corrections. This configuration allows more precise reproduction of frictional and collision behavior at the aluminum formwork contact surfaces and minimizes numerical errors in force calculation. Under these conditions, simulations were performed using various combinations of environmental variables, and the required operational force was calculated for each scenario.

Using the 100 environmental variable datasets generated through random sampling as input, simulations were conducted to estimate the operational force required for aluminum formwork removal under each environmental condition. Removal success was defined as the moment when the lower part of the formwork was displaced by at least 10 cm, and the operational force at the first occurrence of this criterion was recorded as the required force for the corresponding condition.

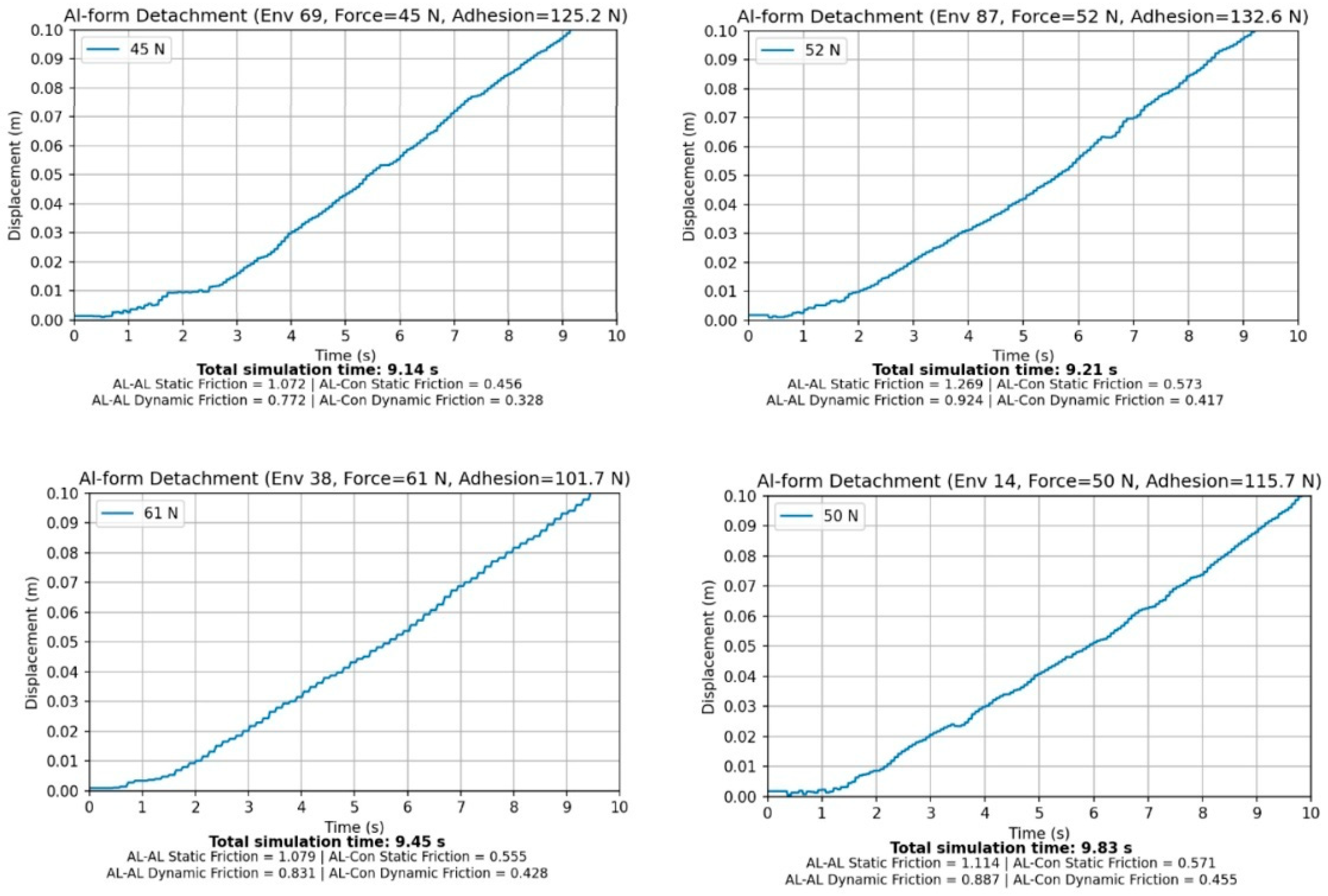

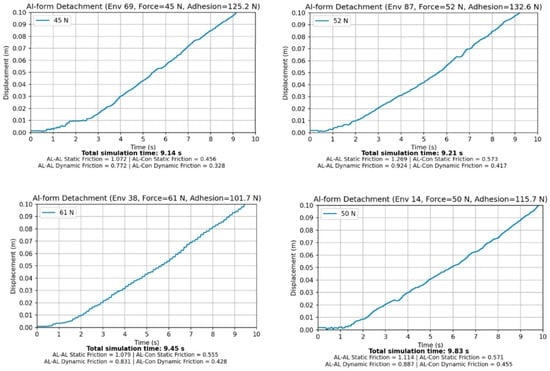

Figure 5 presents a representative simulation result illustrating the temporal evolution of operational force and removal displacement during aluminum formwork removal. As time progresses, the removal displacement increases gradually, and in most simulations, successful removal was achieved after approximately 9–10 s. This behavior indicates that the removal process follows a gradual separation mechanism rather than an abrupt failure mode.

Figure 5.

Simulation results of aluminum formwork removal.

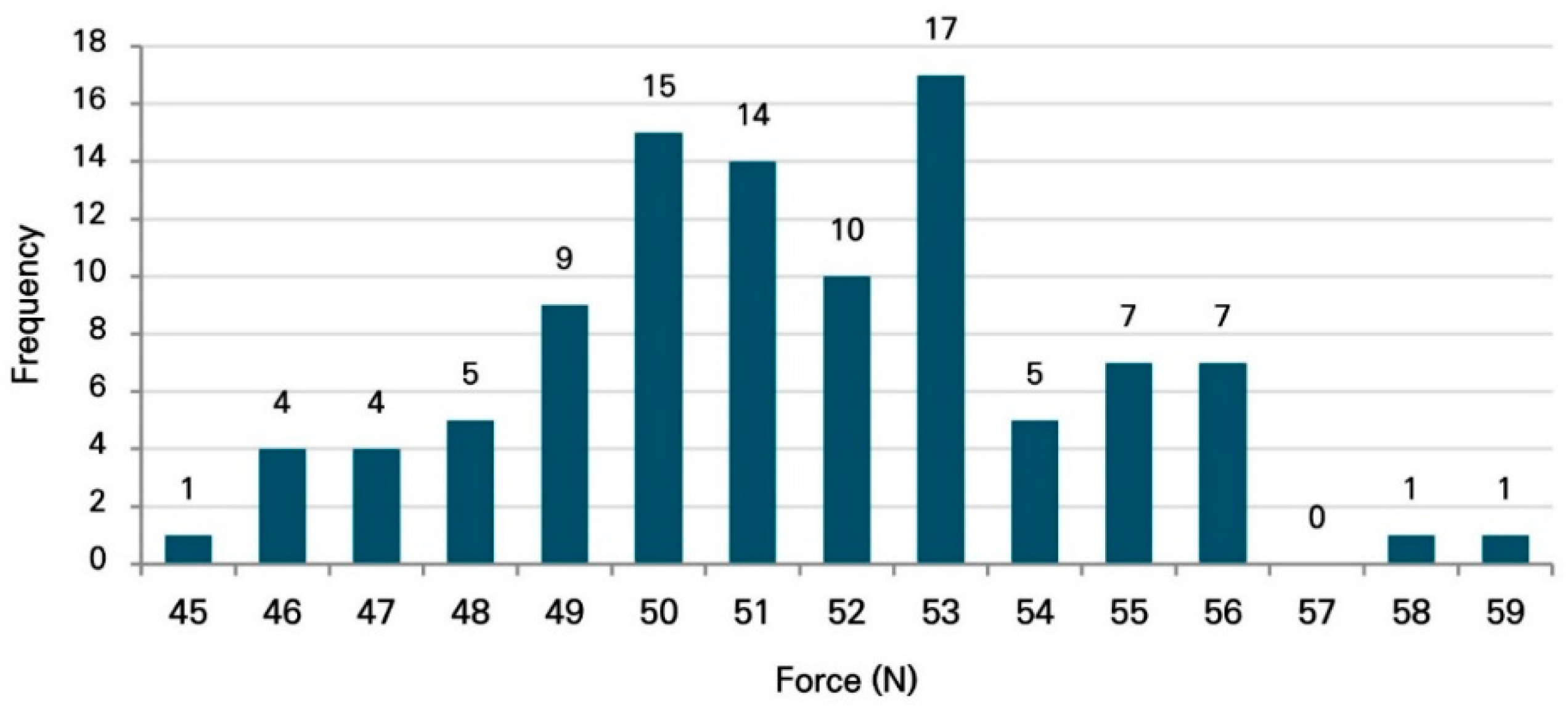

A statistical summary of the results obtained from all 100 simulation runs is presented in Table 6. The average operational force required for aluminum formwork removal was 51.47 N, with a standard deviation of 2.82 N. The maximum and minimum required forces were 59 N and 45 N, respectively. Quartile analysis further indicates that the first quartile (Q1), median (Q2), and third quartile (Q3) were 50 N, 51 N, and 53 N, respectively, demonstrating that the force distribution is concentrated within a relatively narrow range. These results suggest that the required operational force does not exhibit extreme dispersion, but instead follows a relatively stable distribution pattern.

Table 6.

Statistical summary of required force for aluminum formwork removal ( = 100).

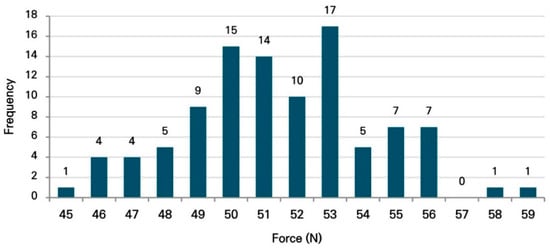

Figure 6 illustrates the force distribution derived from the 100 simulation results using a histogram. The horizontal axis represents the required force at the moment of successful removal, while the vertical axis indicates the frequency of successful removal within each force interval. Most results are concentrated in the range of 50–53 N, which is consistent with the mean value and quartile analysis. This distributional characteristic demonstrates that a distribution-based force determination approach, rather than reliance on a single maximum value, can provide a rational and reliable basis for force design.

Figure 6.

Histogram of force distribution obtained from the simulation.

4.2.5. Sensitivity Analysis and Energy-Saving Strategy Identification

Based on the operational forces estimated for the 100 environmental variable combinations generated through ISAAC SIM-based simulations, variations in the required force were observed across different environmental conditions. To quantitatively assess the relative influence of individual environmental variables on the required operational force, Pearson correlation analysis was performed. This analysis was used as an interpretive tool to identify overall increasing or decreasing trends between environmental variables and the required force.

Table 7 presents the Pearson correlation coefficients between the required operational force and each environmental variable. The results indicate that the dynamic friction coefficient between aluminum–aluminum contact surfaces () exhibits the highest correlation coefficient (0.58), identifying it as the most influential variable affecting the force required for formwork removal. This finding suggests that friction generated at the lateral contact surfaces between adjacent aluminum formwork panels plays a critical role in increasing the overall operational force during the removal process.

Table 7.

Pearson correlation coefficients between required force and environmental variables.

The static friction coefficient between aluminum–aluminum contact surfaces () shows the second-highest correlation coefficient (0.41), while the remaining variables exhibit positive correlations with relatively lower influence. These results indicate that aluminum–aluminum friction consistently contributes to increases in the required operational force and should be considered a key design parameter in the development of automated formwork removal systems.

Based on the correlation analysis results, this study proposes reducing the dynamic friction coefficient at aluminum–aluminum contact interfaces as an effective energy-saving strategy for formwork removal. Such a strategy can be implemented through physical treatments such as lubrication, and previous studies have reported that lubrication significantly reduces aluminum–aluminum friction compared to dry and clean surface conditions [27]. Reducing friction in this manner decreases the required operational force during removal and can consequently lower energy consumption, thereby extending battery operating time for robotic systems.

Since construction projects involve tightly coupled processes in which delays in individual tasks can propagate to affect overall project schedules, energy-efficient force design strategies are directly linked to operational stability. Accordingly, the proposed friction-reduction strategy is expected to contribute to maintaining continuous robotic operation and improving overall task efficiency in construction automation environments.

4.2.6. Simulation-Based Validation of Energy-Saving Strategy

This section quantitatively validates the effectiveness of the proposed energy-saving strategy by applying a reduction in the aluminum–aluminum friction coefficient, identified as the most influential variable in the previous analysis. To this end, a lubrication condition was assumed at the lateral contact interfaces of aluminum formwork panels to reduce friction, and the simulation was re-executed following the same procedure as the baseline scenario.

Under the lubrication condition, the sampling range of the static friction coefficient between aluminum–aluminum contact surfaces () was adjusted to 0.15–0.45, while the dynamic friction coefficient was set to 70–80% of the corresponding static value, consistent with the baseline modeling approach. All other environmental variables, including adhesion force and ISAAC SIM simulation settings, were kept identical to those in the baseline scenario in order to isolate the effect of friction reduction on the required operational force. The sampling ranges used under the lubrication condition are summarized in Table 8.

Table 8.

Lubrication-applied sampling ranges of environmental variables.

Using the redefined environmental variable distributions, a total of 100 simulation runs were performed. The results show that the required operational force for aluminum formwork removal was markedly reduced compared to the baseline condition.

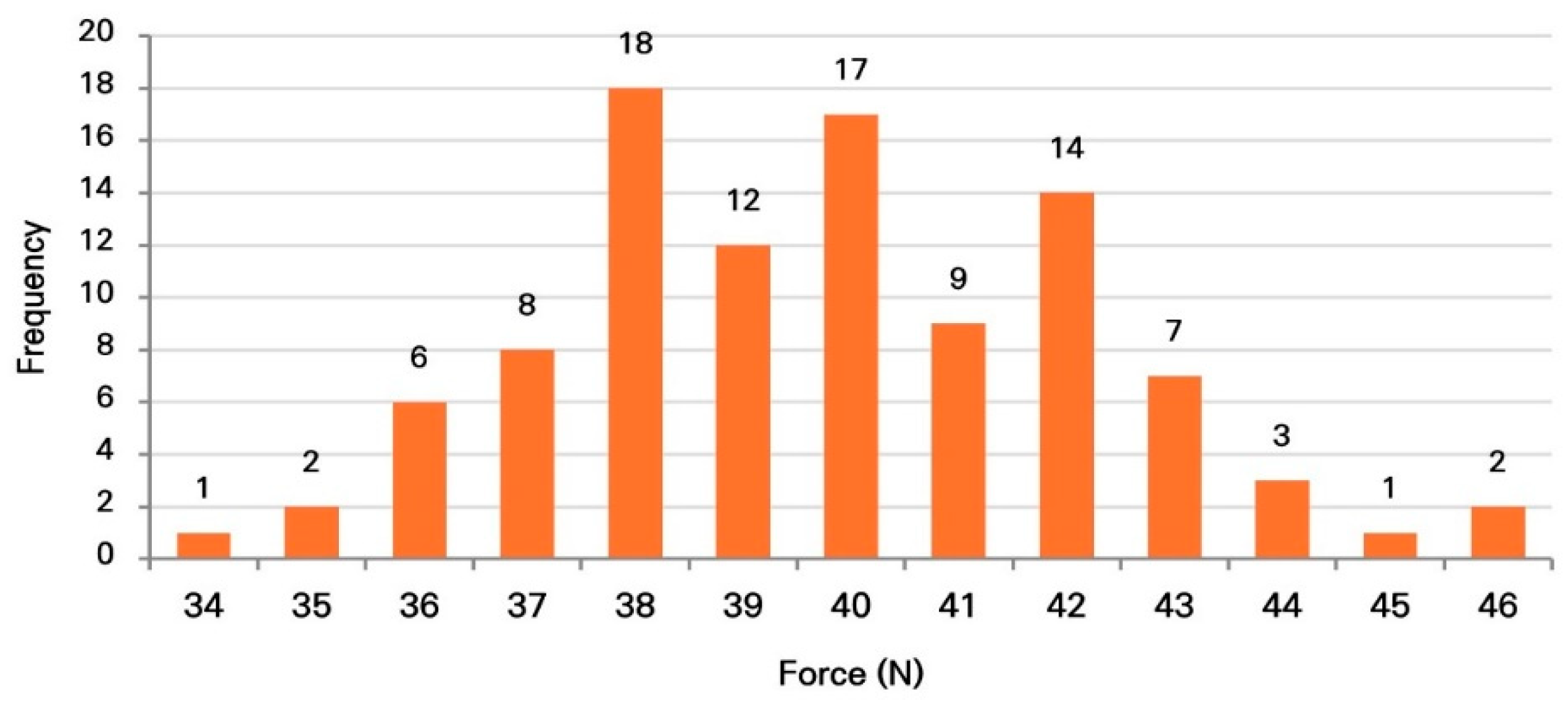

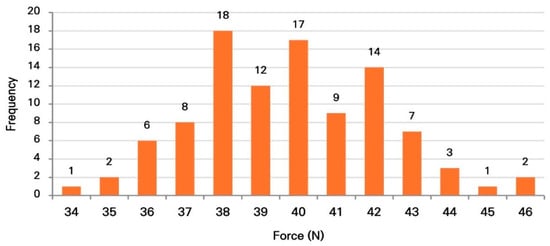

Figure 7 illustrates the force distribution obtained under the lubrication condition. As shown in the figure, the distribution remains approximately symmetric around its mean, with the highest frequency of successful removal occurring at 38 N. The second-highest frequency is observed around 40 N, indicating that the center of the force distribution shifts toward lower values relative to the baseline scenario.

Figure 7.

Force distribution histogram after reducing aluminum–aluminum friction.

According to Table 9, the average required force for aluminum formwork removal after applying the lubrication condition was 39.75 N, with a standard deviation of 2.46 N. The minimum and maximum required forces were 34 N and 46 N, respectively. Quartile analysis shows that the first quartile (Q1), median (Q2), and third quartile (Q3) were 38 N, 40 N, and 42 N, respectively, indicating that the force distribution shifted toward a lower range compared to the baseline condition.

Table 9.

Statistical summary of the required force for aluminum formwork removal ( = 100), after reducing aluminum–aluminum friction.

These results suggest that reducing the aluminum–aluminum friction coefficient effectively decreases the operational force required for formwork removal, while simultaneously maintaining mechanical reliability and stability during repetitive operations through a distribution-based force setting. For example, when the mean and variance of the force distribution are considered, applying an operational force of approximately 43.8 N enables successful removal with a confidence level of 97.5%. This finding demonstrates the validity of a distribution-based operational force determination approach that prioritizes energy efficiency, rather than relying on conservative design based solely on maximum force values.

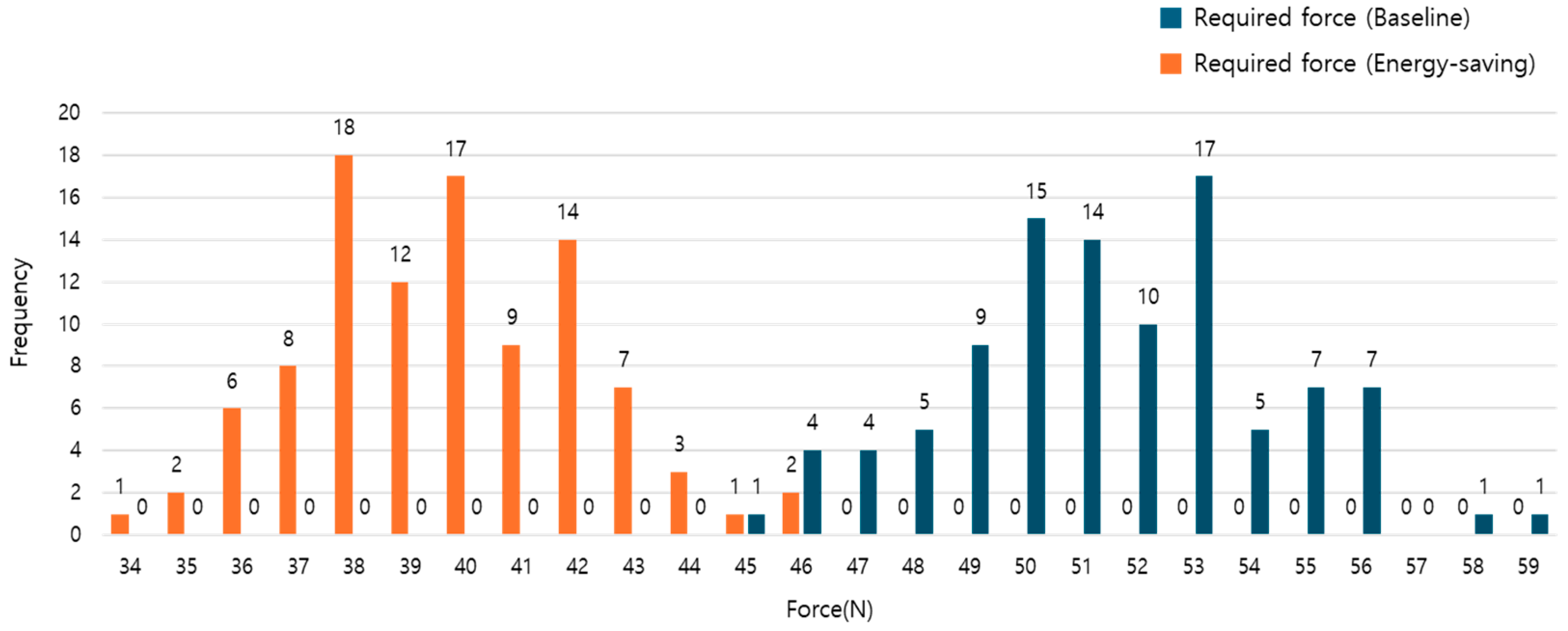

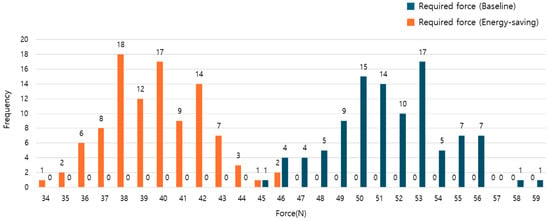

4.2.7. Determination of Optimal Operational Force Considering Force Distribution

Figure 8 compares the force distributions obtained before and after applying the energy-saving strategy based on lubrication. As shown in the figure, the mean value of the force distribution decreases after the strategy is applied, indicating that friction generated at the lateral contact interfaces between aluminum formwork panels is a key factor influencing the required operational force during the removal process. Accordingly, this study applies a friction-reduction strategy by lubricating the contact surfaces to reduce friction coefficients. As a result, the average required operational force after applying the lubrication strategy decreased by approximately 18.97% compared to the baseline condition.

Figure 8.

Force distribution before and after applying the energy-saving strategy.

In this study, we aimed to collect normally distributed force data based on 100 randomly generated environmental variable sets. A histogram analysis of the simulated force outputs from these 100 datasets showed a bell-shaped distribution consistent with normality. To further verify this, we conducted an additional simulation using another 100 randomly generated datasets, totaling 200 samples. The resulting force distribution also exhibited a similar bell-shaped curve, further supporting the assumption of normality. Given the strong consistency observed in the distribution patterns between the initial 100 samples and the extended 200 samples, we concluded that 100 samples were sufficient to represent the overall statistical behavior of the force distributions. This sampling approach ensures both computational efficiency and statistical reliability for subsequent analysis.

To check the normality assumption required for confidence-level estimation, we applied the Shapiro–Wilk test to a set of 100 simulated force values. The result showed W = 0.983 and a p-value = 0.210, which suggests that the data can be considered normally distributed. Combined with the histogram, which exhibited a bell-shaped distribution both before and after optimization, these results support the use of normality-based confidence interval estimation in our analysis.

Assuming a normal distribution for estimation purposes, the required operational forces corresponding to different confidence levels before and after applying the energy-saving strategy are summarized in Table 10. Based on the mean and standard deviation of the force distribution, an operational force of 42.90 N enables successful removal with approximately 95% confidence, while forces of 43.79 N, 44.80 N, and 45.47 N correspond to confidence levels of 97.5%, 99%, and 99.5%, respectively.

Table 10.

Comparison of required force by confidence level with and without the energy-saving strategy.

To ensure sufficient reliability in practical operation, a safety factor of 10% was applied to the derived force values. As a result, the final optimal operational force required for aluminum formwork removal was determined to be 50.01 N, representing a reduction of 11.71 N compared to the baseline condition. This corresponds to an approximate reduction of 18.97% in the required force, demonstrating that adequate operational stability can be maintained while effectively reducing energy consumption and power demand associated with excessive force application.

These findings indicate that reducing friction through targeted energy-saving strategies can prevent overly conservative force design, thereby lowering power consumption and extending battery operating time for construction robots. Given the tightly coupled nature of construction processes, where delays in individual tasks can propagate to affect overall project schedules, the proposed distribution-based optimal operational force determination method provides a practical and reliable design criterion for improving both stability and efficiency in construction automation systems. Furthermore, the simulation-based approach incorporating diverse environmental conditions through random sampling offers a generalized framework that can be extended to other construction automation tasks and force design problems.

5. Conclusions

This study presented a simulation-based methodology for determining the optimal operational force in construction robot design while explicitly considering energy efficiency. Using aluminum formwork removal as a case study, key environmental variables influencing the required operational force were defined, and probability distributions were assigned to these variables to reflect site variability. Environmental datasets incorporating such variability were generated through random sampling and used as input for simulation-based analysis, enabling characterization of force distributions required for formwork removal under diverse conditions.

Simulations were conducted using NVIDIA ISAAC SIM to virtually reproduce aluminum formwork removal environments, and operational force results were obtained based on 100 randomly sampled datasets incorporating friction coefficients and adhesion forces. The results demonstrate that the required operational force for automated formwork removal is more appropriately represented as a probability distribution rather than a single deterministic value, highlighting the necessity of a distribution-based force determination approach. Sensitivity analysis further revealed that the dynamic friction coefficient at aluminum–aluminum contact interfaces () is the most influential variable affecting the required operational force.

Based on this finding, a friction-reduction design strategy was implemented by applying lubrication at formwork contact interfaces, and its effectiveness was quantitatively evaluated through simulation-based validation. The results show that the average required operational force decreased by approximately 18.97% after applying the lubrication strategy, corresponding to a force reduction of 11.71 N. These improvements indicate practical benefits, including reduced power consumption of automated equipment, extended battery operating time, and mitigation of schedule delays associated with battery replacement or recharging.

Several limitations of this study and directions for future research should be noted. First, sensitivity analysis was limited to the Pearson correlation coefficient, which reflects only linear relationships between environmental variables and operational force. However, due to the diverse and complex nature of environmental conditions, some variables may exhibit nonlinear relationships that cannot be fully captured by this method. For such cases, future studies may adopt nonlinear analysis techniques such as SHAP or Random Forest to more accurately evaluate variable influence.

Second, we acknowledge that although the simulation environment modeled environmental variables such as friction coefficients and adhesion forces with probabilistic distributions, several real-world factors remain unaccounted for. These include the following:

- Residual cement or contaminants on the aluminum formwork surface;

- Surface irregularities and misalignment due to installation error;

- Variations in environmental conditions, such as temperature, humidity, and site cleanliness;

- Mechanical backlash or slippage in actual actuation systems.

Such uncontrolled variables can potentially lead to deviations in the actual force required for dismantling compared to the simulated estimations. To compensate for this gap, we proposed an additional 10% safety margin on the optimal operational force derived from simulation. This margin aims to accommodate uncertainties not captured in simulation while avoiding overdesign. Incorporating task-specific environmental conditions through additional experiments may enable more tailored force determination for different construction processes. Third, this study focused on the force required for initial formwork removal; however, in actual construction scenarios, the required force may vary depending on the removal sequence. Integrating vision-based systems to account for removal order could allow adaptive force adjustment and further reduction in unnecessary energy consumption. Finally, detailed mechanical design aspects of the removal device, such as screw mechanisms and joint connections, were not considered. Future work incorporating mechanical stress analysis and component-level optimization could further enhance energy efficiency.

Overall, the simulation-based operational force determination methodology proposed in this study offers a practical means of preventing overly conservative design by explicitly accounting for uncertainty in environmental variables, while providing a quantitative basis for force specification in construction robot design. The core contribution of this work lies in presenting a distribution-based optimal force determination approach applicable to robots performing repetitive, load-intensive tasks across diverse construction site scenarios. Although validated through an aluminum formwork removal case study, the proposed framework is extensible to similar construction automation processes, such as slab dismantling and large panel removal, and provides a foundational basis for developing energy-efficient and reliable construction robotic systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Y.; Methodology, J.Y.; Validation, J.K. (Jaemin Kim) and T.Y.; Investigation, T.Y., M.L. and J.K. (Jiyeon Kim); Data curation, J.K. (Jaemin Kim), T.Y., M.L., J.K. (Jiyeon Kim) and S.L.; Writing—original draft, J.K. (Jaemin Kim); Writing—review & editing, S.L.; Visualization, J.K. (Jaemin Kim), T.Y. and S.L.; Supervision, S.L. and J.Y.; Project administration, J.Y.; Funding acquisition, J.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The present Research has been conducted by the Research Grant of Kwangwoon University in 2025.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Sampled Environment Parameters via Random Sampling

| 1.16 | 0.45 | 0.82 | 0.32 | 144.94 |

| 1.34 | 0.55 | 1.01 | 0.41 | 105.89 |

| 1.27 | 0.50 | 0.96 | 0.37 | 111.31 |

| 1.23 | 0.53 | 0.94 | 0.40 | 162.90 |

| 1.10 | 0.59 | 0.85 | 0.45 | 142.45 |

| 1.10 | 0.49 | 0.87 | 0.39 | 100.64 |

| 1.07 | 0.51 | 0.80 | 0.38 | 107.10 |

| 1.31 | 0.56 | 0.96 | 0.41 | 146.45 |

| 1.23 | 0.48 | 0.96 | 0.38 | 100.35 |

| 1.26 | 0.46 | 0.92 | 0.34 | 111.26 |

| 1.06 | 0.49 | 0.79 | 0.37 | 138.41 |

| 1.34 | 0.47 | 0.95 | 0.34 | 148.43 |

| 1.30 | 0.59 | 0.91 | 0.41 | 145.64 |

| 1.11 | 0.57 | 0.89 | 0.45 | 115.70 |

| 1.10 | 0.55 | 0.87 | 0.43 | 149.85 |

| 1.11 | 0.58 | 0.85 | 0.45 | 116.61 |

| 1.14 | 0.57 | 0.85 | 0.42 | 122.78 |

| 1.21 | 0.48 | 0.87 | 0.34 | 152.25 |

| 1.18 | 0.58 | 0.84 | 0.42 | 145.47 |

| 1.14 | 0.53 | 0.82 | 0.38 | 159.45 |

| 1.23 | 0.57 | 0.93 | 0.43 | 146.03 |

Appendix A.2. Force Results Before Applying the Energy-Saving Strategy

| Force (N) | |||||

| 1.232263 | 0.513 | 0.906 | 0.377 | 155.637 | 59.000 |

| 1.20682 | 0.559 | 0.948 | 0.439 | 153.900 | 58.000 |

| 1.340875 | 0.586 | 1.006 | 0.440 | 120.611 | 56.000 |

| 1.20427 | 0.579 | 0.917 | 0.441 | 127.517 | 56.000 |

| 1.056175 | 0.493 | 0.786 | 0.367 | 138.411 | 56.000 |

| 1.326562 | 0.486 | 1.014 | 0.372 | 138.976 | 56.000 |

| 1.278236 | 0.585 | 0.942 | 0.431 | 157.582 | 56.000 |

| 1.33185 | 0.472 | 1.020 | 0.361 | 159.580 | 56.000 |

| 1.227724 | 0.451 | 0.911 | 0.335 | 162.443 | 56.000 |

| 1.316164 | 0.529 | 1.020 | 0.410 | 120.058 | 55.000 |

| 1.149269 | 0.589 | 0.877 | 0.449 | 126.291 | 55.000 |

| 1.28254 | 0.486 | 1.008 | 0.382 | 126.957 | 55.000 |

| 1.281381 | 0.554 | 1.005 | 0.434 | 155.881 | 55.000 |

| 1.229598 | 0.526 | 0.939 | 0.402 | 162.899 | 55.000 |

| 1.294638 | 0.484 | 0.995 | 0.372 | 163.927 | 55.000 |

| 1.109902 | 0.573 | 0.838 | 0.433 | 168.111 | 55.000 |

| 1.318448 | 0.523 | 0.944 | 0.375 | 122.185 | 54.000 |

| 1.236989 | 0.467 | 0.952 | 0.359 | 123.660 | 54.000 |

| 1.096806 | 0.586 | 0.847 | 0.453 | 142.450 | 54.000 |

| 1.057626 | 0.583 | 0.820 | 0.452 | 143.602 | 54.000 |

| 1.308931 | 0.501 | 0.932 | 0.357 | 162.300 | 54.000 |

| 1.335214 | 0.545 | 1.006 | 0.411 | 105.890 | 53.000 |

| 1.298621 | 0.545 | 0.969 | 0.406 | 109.806 | 53.000 |

| 1.269598 | 0.497 | 0.957 | 0.375 | 111.314 | 53.000 |

| 1.22937 | 0.598 | 0.869 | 0.423 | 111.864 | 53.000 |

| 1.33969 | 0.591 | 0.944 | 0.417 | 113.667 | 53.000 |

| 1.285553 | 0.514 | 0.995 | 0.398 | 117.079 | 53.000 |

| 1.186821 | 0.484 | 0.944 | 0.385 | 118.564 | 53.000 |

| 1.141384 | 0.528 | 0.897 | 0.415 | 119.654 | 53.000 |

| 1.218383 | 0.545 | 0.947 | 0.424 | 125.213 | 53.000 |

| 1.322796 | 0.495 | 0.983 | 0.368 | 125.911 | 53.000 |

| 1.198139 | 0.502 | 0.950 | 0.398 | 136.557 | 53.000 |

| 1.063935 | 0.527 | 0.771 | 0.382 | 144.180 | 53.000 |

| 1.309853 | 0.563 | 0.959 | 0.413 | 146.445 | 53.000 |

| 1.092277 | 0.498 | 0.870 | 0.397 | 148.791 | 53.000 |

| 1.15754 | 0.591 | 0.905 | 0.461 | 149.138 | 53.000 |

| 1.290659 | 0.478 | 1.020 | 0.378 | 149.174 | 53.000 |

| 1.212809 | 0.575 | 0.896 | 0.425 | 151.854 | 53.000 |

| 1.147555 | 0.549 | 0.895 | 0.428 | 102.516 | 52.000 |

Appendix A.3. Force Results After Applying the Energy-Saving Strategy

| Force (N) | |||||

| 0.330 | 0.484 | 0.258 | 0.378 | 100.354 | 37.000 |

| 0.197 | 0.487 | 0.157 | 0.389 | 100.644 | 39.000 |

| 0.228 | 0.493 | 0.168 | 0.365 | 101.082 | 38.000 |

| 0.179 | 0.555 | 0.138 | 0.428 | 101.702 | 43.000 |

| 0.186 | 0.464 | 0.149 | 0.371 | 102.135 | 37.000 |

| 0.248 | 0.549 | 0.193 | 0.428 | 102.516 | 40.000 |

| 0.364 | 0.585 | 0.270 | 0.433 | 102.614 | 40.000 |

| 0.435 | 0.545 | 0.328 | 0.411 | 105.890 | 36.000 |

| 0.182 | 0.567 | 0.141 | 0.440 | 105.974 | 42.000 |

| 0.238 | 0.498 | 0.182 | 0.381 | 106.557 | 39.000 |

| 0.169 | 0.582 | 0.133 | 0.458 | 106.579 | 42.000 |

| 0.248 | 0.559 | 0.188 | 0.424 | 106.802 | 41.000 |

| 0.167 | 0.512 | 0.126 | 0.385 | 107.103 | 40.000 |

| 0.381 | 0.501 | 0.280 | 0.368 | 108.894 | 37.000 |

| 0.399 | 0.545 | 0.297 | 0.406 | 109.806 | 42.000 |

| 0.362 | 0.462 | 0.264 | 0.336 | 111.257 | 35.000 |

| 0.370 | 0.497 | 0.279 | 0.375 | 111.314 | 38.000 |

| 0.329 | 0.598 | 0.233 | 0.423 | 111.864 | 40.000 |

| 0.282 | 0.596 | 0.200 | 0.423 | 112.398 | 40.000 |

| 0.440 | 0.591 | 0.310 | 0.417 | 113.667 | 41.000 |

| 0.278 | 0.585 | 0.207 | 0.434 | 115.107 | 41.000 |

| 0.214 | 0.571 | 0.170 | 0.455 | 115.699 | 43.000 |

| 0.205 | 0.581 | 0.158 | 0.447 | 116.607 | 44.000 |

| 0.386 | 0.514 | 0.298 | 0.398 | 117.079 | 42.000 |

| 0.287 | 0.484 | 0.228 | 0.385 | 118.564 | 40.000 |

| 0.241 | 0.528 | 0.190 | 0.415 | 119.654 | 42.000 |

| 0.416 | 0.529 | 0.323 | 0.410 | 120.058 | 40.000 |

| 0.446 | 0.539 | 0.315 | 0.381 | 120.551 | 38.000 |

| 0.441 | 0.586 | 0.331 | 0.440 | 120.611 | 40.000 |

| 0.418 | 0.523 | 0.300 | 0.375 | 122.185 | 38.000 |

| 0.241 | 0.571 | 0.179 | 0.423 | 122.778 | 43.000 |

| 0.337 | 0.467 | 0.259 | 0.359 | 123.660 | 36.000 |

| 0.172 | 0.456 | 0.124 | 0.328 | 125.164 | 35.000 |

| 0.318 | 0.545 | 0.248 | 0.424 | 125.213 | 40.000 |

| 0.260 | 0.467 | 0.189 | 0.340 | 125.740 | 37.000 |

Appendix B

| Algorithm A1 Pseudo-Code for Generation of Environmental Parameter Sets via Random Sampling |

| Input: - Ranges and probability distributions of static friction coefficients (, ) - Range and probability distribution of adhesion force () - Number of samples N Output: - Environmental parameter dataset for simulation-based force calculation 1. Initialize random seed for reproducibility 2. For i = 1 to N do 3. Sample from Uniform(μ_AA_min, μ_AA_max) 4. Sample from Uniform(μ_SC_min, μ_SC_max) 5. Sample from Uniform(F_adhesion_min, F_adhesion_max) 6. Sample dynamic_ratio from Uniform(0.70, 0.80) 7. Compute = × dynamic_ratio 8. Compute = × dynamic_ratio 9. Store all parameters as one environmental parameter set 10. End for 11. Return the dataset for subsequent simulation analysis |

References

- Liu, C.-H.; Chung, F.-M.; Chen, Y.; Chiu, C.-H.; Chen, T.-L. Optimal design of a motor-driven three-finger soft robotic gripper. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2020, 25, 1830–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ji, W.; Xu, B.; Yu, X. Optimizing contact force on an apple picking robot end-effector. Agriculture 2024, 14, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Meng, L.; Kang, R.; Liu, B.; Gu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, F.; Ming, A. Design and dynamic locomotion control of quadruped robot with perception-less terrain adaptation. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 2022, 2022, 9816495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chignoli, M.; Kim, D.; Stanger-Jones, E.; Kim, S. The MIT humanoid robot: Design, motion planning, and control for acrobatic behaviors. In Proceedings of the IEEE-RAS 20th International Conference on Humanoid Robots (Humanoids); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sombolestan, M.; Chen, Y.; Nguyen, Q. Adaptive force-based control for legged robots. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 7440–7447. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, W.; Zheng, L.; Yun, C. Force control-based vibration suppression in robotic grinding of large thin-wall shells. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2021, 67, 102031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Xu, Q. Design of a new passive end-effector based on constant-force mechanism for robotic polishing. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2022, 74, 102278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yang, C.; Chen, C.P. Optimal robot–environment interaction under broad fuzzy neural adaptive control. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 51, 3824–3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Yang, Z.; Lum, G.Z. Small-scale magnetic actuators with optimal six degrees-of-freedom. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2100170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Chen, T.; Zlokapa, L.; Foshey, M.; Matusik, W.; Sueda, S.; Agrawal, P. An end-to-end differentiable framework for contact-aware robot design. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.07501. [Google Scholar]

- Ikemura, K.; Dong, Y.; Blanco-Mulero, D.; Longhini, A.; Chen, L.; Pokorny, F.T. Sim-to-real gentle manipulation of deformable and fragile objects with stress-guided reinforcement learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.25405. [Google Scholar]

- Tillé, Y.; Wilhelm, M. Probability sampling designs: Principles for choice of design and balancing. Stat. Sci. 2017, 32, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Y.G. Rate of convergence to normal distribution for the Horvitz–Thompson estimator. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 1998, 67, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.L.; Sturrock, H.J.; Olives, C.; Solomon, A.W.; Brooker, S.J. Comparing the performance of cluster random sampling and integrated threshold mapping for targeting trachoma control using computer simulation. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn, W.; Hong, E.H. Monte Carlo simulation for verification of nonparametric tests used in final status surveys of MARSSIM at decommissioning of nuclear facilities. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2021, 53, 1664–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G. Pros and cons of different sampling techniques. Int. J. Appl. Res. 2017, 3, 749–752. [Google Scholar]

- Janse, R.J.; Hoekstra, T.; Jager, K.J.; Zoccali, C.; Tripepi, G.; Dekker, F.W.; Van Diepen, M. Conducting correlation analysis: Important limitations and pitfalls. Clin. Kidney J. 2021, 14, 2332–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correlation and Regression Analysis. Available online: https://sesricdiag.blob.core.windows.net/oicstatcom/TEXTBOOK-CORRELATION-AND-REGRESSION-ANALYSIS-EGYPT-EN.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- Mazkewitsch, A.; Jaworski, A. The adhesion between concrete and formwork. In Adhesion Between Polymers and Concrete; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1986; pp. 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Engineering ToolBox. Available online: https://www.engineeringtoolbox.com/ (accessed on 24 January 2026).

- Pallett, P.; Gorst, N.; Clark, L.; Thomas, D. Friction resistance in temporary works materials. Concrete 2002, 36, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Engineers Edge. Coefficients of Friction. Available online: https://www.engineersedge.com/coeffients_of_friction.htm (accessed on 24 January 2026).

- Jiang, Q.; Yu, C.; Zhou, M. Aesthetic properties of concrete surfaces: An experimental study employing three typical formworks with emphasis on reusability. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.S.; Kim, S.I.; So, S.Y. Safety and concrete quality evaluation according to surface treatment methods and reuse numbers of aluminum formwork. J. Korean Soc. Struct. Diagn. Maint. 2025, 29, 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Makoviychuk, V.; Wawrzyniak, L.; Guo, Y.; Lu, M.; Storey, K.; Macklin, M.; State, G. Isaac Gym: High performance GPU-based physics simulation for robot learning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.10470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]