Abstract

Material circularity in construction requires material information at the end of life for the trading of materials. Different digital technologies (DTs) are essential for such information management. This research aims to review key aspects of developing a blockchain-based material passports (MPs) system when integrating with key DTs used for MPs. This research is based on a critical literature review, with an integrative approach that synthesises both academic and grey literature. The literature search was initiated using chosen keywords relevant to the topic to first identify the key literature. This was followed by using a snowballing technique to expand the search with further relevant literature. Building Information Modelling (BIM), digital twin (DTw) and blockchain technology (BCT) were identified as key technologies for material information management. BIM and DTw are central to the management process as all the information created and collected is modelled, visualised, analysed and stored using BIM platforms. However, existing MP platforms utilising centralised databases to store data were found to be unreliable for managing material data in an industry like construction with a dispersed supply chain and typically longer lifecycle. BCT was realised as necessary for information management in construction, as it allows us to manage information in a more decentralised, transparent and immutable manner. Furthermore, examining current research about blockchain application for information management in construction led to the conclusion that, although the studies on blockchain-based MP platforms covering the entire industry supply chain prevail, the management of material data at the built asset level throughout its lifecycle using such MP systems is underexplored. Thus, building on the literature review, a conceptual model of blockchain-based MP system is proposed in this paper, describing integration with BIM and DTw, and with relevant processes and actors to manage MP information throughout the building lifecycle. Acknowledging the limitations of a subjective literature review, the conceptual model and the ideas are proposed as a foundation for further research and develop MP system with empirical validation. Although theoretically, this study identifies the suitability of blockchain technology for managing product lifecycle information in industry like construction and provides ground for further theoretical research for planning and policy required for blockchain-based MP development and implementation.

1. Introduction

Sustainability, particularly innovative ways of achieving material circularity, is imperative in the construction sector, as it is responsible for a large amount of material consumption, material waste and CO2 emissions. Construction industry accounts for one third of the resource consumption globally [1], and it is responsible for 38% of global energy-related CO2 emissions [2]. According to Australian government statistics in 2023, about 38% of the total annual waste comes from the construction industry [3]. The circular economy (CE) has been identified as one of the key approaches to achieving overall sustainability, including the construction industry [1].

When implementing CE in construction, the existing buildings are the major source of resource extraction for reuse in new buildings. In contrast to other industries, the products (built assets) in construction have longer lifecycles, resulting in difficulties in maintaining reliable material information over long periods. It is important to maintain relevant information about materials by the parties owning and managing the asset and to make it available for possible next users. Therefore, material flow should be managed at a city or regional level [4]. Firstly, a material flow analysis at the city/regional level, which quantifies the material flow and waste management capacity in the region, needs to be conducted to understand the urban metabolism and CE scenarios in any region [5,6]. Further to material quantity, it is important to capture other information about materials contained in built assets within a region, such as information on material suitability, necessary actions for possible next use of secondary-sourced materials [7,8], material composition [9], environmental impacts [10], and instructions for construction and deconstruction [6].

Thus, the management of material information is a prerequisite for achieving material circularity in construction. For any built asset, this should start right from the point of creation of information at the design stage [10,11]. In fact, the building to be constructed can be treated as a material bank [11], and records of material information should be kept considering its end-of-life options early on from the design phase [12]. The information about suitability and the process to be adopted for next use of materials should be ready at the end of each building lifecycle [6]. Overall, a material information management system for construction built asset should be able to capture information at the design stage, update and manage this information throughout its lifecycle, and retrieve it at the end of the lifecycle [7,8].

Material passports (MPs) have been pointed out as a tool for information management in construction. MPs are basically digital datasets consisting of information on materials [13]. In case of construction, the material hierarchy might vary at different levels such as material, component, system and building level. The information has to be maintained as required for all these levels in order to undertake circularity actions [13]. MP information is useful at various lifecycle stages, such as analysing the environmental impacts of design variants and the impacts of the asset’s operation and maintenance activities [6]. During the operation and maintenance phase of a built asset, MP records provide information for analysing and controlling resource consumption [6] and information about maintenance and repair, thereby enabling the tracking of material utility throughout its lifecycle [14]. Collectively, MPs act as an information source for various circularity actions, and for circularity assessments of built assets. With reliable storing and updating of material information in MPs, built assets can be considered as material banks [15].

There are several existing online platforms for MPs, which employ different digital technologies (DTs). One of them is the Madaster online platform, which allows users to create and archive MPs [8,16]. The Madaster platform is under operation, and, in the case of MPs, data are sourced from Building Information Modelling (BIM) for product data spreadsheets [14]. The ‘Building As Material Banks’ (BAMB) was a research project by the European Union (EU), which developed another online MP platform [15]. The BAMB project only developed a validating prototype and set up groundwork for developing and regulating material passports. Another such EU project, the ‘Digital Building Logbook (DBL)’, has put forward the concept of a digital logbook containing information about buildings for sustainability and circularity actions by pooling BIM data [17]. The DBL project is currently piloting implementation by bringing together five different existing logbooks in Europe to develop a common repository [18]. In addition to these platforms that are developed specifically for built environment information management, there are non-digital MP initiatives developed for products in general. For example, ‘Digital Product Passports’ consists of a cross-sectoral regulatory framework for setting eco-design requirements and recording product information [14]. Another similar cross-industry initiative is ‘Product Circularity Data Sheets’, which consists of an open-source industry standard to facilitate exchange of product circularity data [19].

The digital MP platforms discussed above are centralised online databases. Data is centrally managed by a firm and holds the guarantee for the authenticity of information. Keeping records of material information in a database managed by another organisation would necessitate that the owner of the asset share access to information about the asset with the firm co-managing the data [20]. This results in issues regarding ownership and data privacy. Privacy is also compromised when data is stored in a publicly accessible open data platform. Adding to that, data being managed centrally is vulnerable to security risks, as there is a single point of failure (SPOF) for data loss [21]. The vulnerability of centralised data management do not align well with the complexities of construction industry, such as the longer lifecycle of products (buildings), and the widely dispersed network of stakeholders throughout an asset’s lifecycle. Every unique product developed for any project needs to be followed up throughout the lifecycle to ensure the reuse of material at the end of its current use [22]. The material needs to be transferred multiple times from one user to another during its lifecycle, for which the information on the utility of material needs to be reliable. Given the longer lifecycle and multiple users of the material, updating and managing the information becomes uncertain when it is stored in a database where data can be altered if acted with bad faith and go undetected [21]. These issues hinder the tracking of materials’ utility throughout the lifecycle [5,23].

The information management for MPs thus requires a system that can keep track of any changes or updates to the information, maintaining a reliable audit trail for future users to refer to before using the existing material. While the existing platforms are intended to manage the data, given the nature of the construction industry, the immutability of the data is key for MP information management. Considering the longer lifecycle, to avoid vulnerabilities of having SPOF, managing data in decentralised manner is more suitable for the construction sector. Moreover, the information about materials is to be collected from different manufacturers and suppliers during design and construction. Therefore, immutable recordkeeping is needed early in the material supply chain to ensure that reliable information about building products is maintained [24]. Even in the case of vendor going out of business in the long run, the system should maintain unalterable data on the material procured. The research and development in this area only started in recent years, and existing platforms are yet to go through a significant part of any built asset lifecycle. However, considering foreseeable vulnerabilities discussed above, there is a need for a robust mechanism. A decentralised and transparent system, designed in response to the needs posed by dispersed stakeholders and comparatively longer lifecycle, should also meet the privacy requirements of the asset’s owner.

Prevailing BIM-based centralised information management is implemented for asset delivery and management within a project or asset organisation. However, it cannot provide the security and trustworthiness of material information required among supply chain members spanning throughout the lifecycle, from pre-construction procurement and manufacturing to deconstruction of the built asset and trading of reclaimed materials. The adoption of blockchain-based technologies is one of the solutions for fulfilling the requirements of MP management in the construction sector. While Incorvaja, et al. [25] and Wilson, et al. [26] suggest the adoption of blockchain throughout construction supply chains, Jaskula, et al. [27] and Tao, et al. [28] go a step further by suggesting the adoption of blockchain for managing information in a BIM common data environment for individual built assets. Blockchain technology (BCT) enables the development of a decentralised and transparent system for managing MPs while ensuring the immutability of data records [29]. The selection of a suitable blockchain platform also enables achieving the required level of privacy [30]. Given the need for industry-encompassing MP platform incorporating blockchain-based technologies, and the focus of existing studies on such industry-wide platforms, it is also necessary to study the management of built asset data throughout its lifecycle using such a platform. While studies focusing on built asset organisation-level BIM CDE management using blockchain exists [27,28], this review investigates the management of information developed in built assets’ BIM CDE within an industry-wide blockchain-based MP platform. As the information on built assets is developed within BIM CDE, firstly as BIM models and later as digital twins in the operation phase, the process of developing MP-relevant information needs to go through the rigour of BIM-based information management to finalise the information on built asset elements that will go into their MPs. As briefly mentioned above, this study intends to further emphasise the blockchain adoption for MPs in construction sector, review the existing concepts of adoption to identify the limitations and put forward the approach required to manage MPs of built assets throughout their lifecycle. As the main contribution, this review has synthesised a conceptual model of a blockchain-based MP system integrating of BIM and blockchain technology (BCT) to manage information on built assets for material circularity through MPs. Coming out of the critical literature review, the conceptual model of the system is developed out of the research done in this area, added with some conceptual decisions about tools, actors and processes in the system. Considering the limitations of the review, the intention was to subject the idea to further evaluation and improvement in future empirical studies involving stakeholders’ input and prototype development.

The following section (Section 2) briefly describes the adopted research method. Section 3 comprises the review of BIM, digital twin (DTw) and BCT leading to justification of blockchain adoption for MPs and possible ways of adoption. In Section 4, the conceptual model for an MP system is presented, which includes the outline of technologies, actors and processes in the system. Section 5 includes a discussion about the conceptual model considering contextual aspects for further development and implementation. Section 6 is the conclusion, including the implications of this review, its limitations and recommendations for further research and practice.

2. Research Method

This study adopts a critical literature review [31] also known as an integrative review [32]. A critical review, as explained by Grant and Booth Grant and Booth [31], involves reviewing significant articles in a field by going beyond simple narration to conceptually and chronologically synthesise the information in order to develop a new theory. It involves analysing the literature leading to some conceptual innovation. Typically, the result of the review is a conceptualised hypothesis or a model [31,32]. Based on a critical review, a conceptual representation of new relationships and perspectives on the topic can be derived [33]. The review can be undertaken for a mature topic to provide an overview of the knowledge base and reconceptualise its theoretical basis, or for an emerging topic to create new preliminary conceptual models [32]. Given the topic under review is a developing one, this review analyses the existing literature and adopts an integrative approach by synthesising information from different fields of digital technologies (DTs), construction and information management. Finally, by integrating different technologies, industry standards and actors, a conceptual model of blockchain-based MP system is developed. The adopted critical review approach is based on Grant and Booth Grant and Booth [31] and is intended to identify the significant items in the research area rather than going through the exhaustive list of literature obtained from keyword searches. The search and selection of the literature need not be systematic and can include research articles, books and other relevant published texts [32]. The selection of literature does require formal quality assessment and can be based on the evaluated contribution of the literature [31].

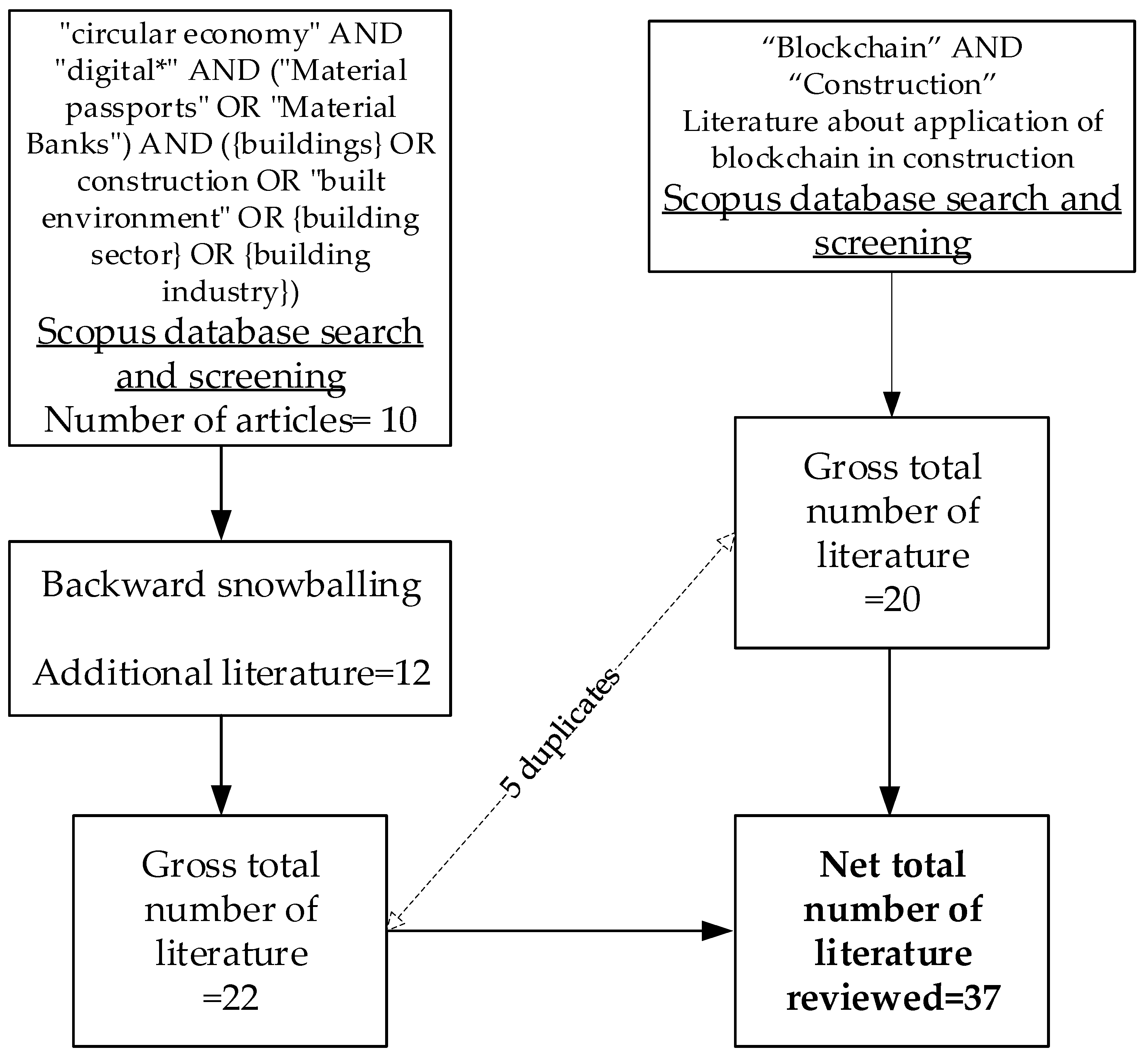

The backward snowballing technique has been adopted to select further relevant studies as observed during the detailed review of the literature obtained in the initial search [34]. The academic articles obtained from the database search were used as the starting set for snowballing. It was realised during the review of these articles that significant work in the research area is being conducted outside of academia. Thus, snowballing included both additional academic literature and grey literature. During backward snowballing, the preliminary list of literature initially obtained from the citation list was further screened by reading abstracts in the case of academic literature and by reading executive summaries or introductions in case of grey literature, in order to select a limited number of articles. The grey literature on industry reports, guidelines and standards was included. In order to obtain credible and controlled literature and avoid bias, the selected grey literature is restricted to either the reports already cited in academic publication or the standards generally adopted in the industry. There are limitations to the adopted methodology. The analysis is interpretive and subjective, and the resulting conceptual model is a starting point for further evaluation, not the final solution for the research problem, which is typically in line with a critical review [31]. The literature selection process is represented in Figure 1 and described further below.

Figure 1.

Literature selection process.

The literature search for this review was initiated by conducting a keyword search in the Scopus database using the following keyword string: “circular economy” AND “digital*” AND (“Material passports” OR “Material Banks”) AND ({buildings} OR construction OR “built environment” OR {building sector} OR {building industry}). The keyword search was limited to title, abstract, and keywords. This keywords string was intended to find the literature related to material passports based on DTs in the construction industry. As publications relevant to digitalisation and material passports have started only few years ago, from the late 2010s, the articles selected were from 2019 up to the time of the search, i.e., October 2025. The Scopus database was adopted because it is the largest database, and generally includes all recent publications [35]. Given the recency of the research topic, the Scopus database provides an exhaustive list of literature to be reviewed. As mentioned above, the selection criteria for the literature related to the application of DTs and MPs for circularity in construction were adopted. After reviewing the abstract and the relevant literature was selected from the obtained list. The initial list obtained after search contained sixty articles, and after screening, ten articles were reviewed in detail. Using the snowballing technique, the citations related to information relevant to this study in those articles were screened and selected to add to this review. Initially, around fifty articles were listed and then screened to select twelve comprising both academic and grey literature. The grey literature, including reports and standards, was about the use of DTs for information management and the purpose of material passports in construction.

For the BCT-related literature review, the search started with highly cited literature on the application of BCT in construction. Using keywords “blockchain” and “construction”, a literature search was conducted in the Scopus database to select highly cited studies and review them to analyse the potential of blockchain in construction. The initial search gave more than 3000 articles, but the selection started from the most highly cited ones. The Scopus database was selected for reasons mentioned previously. Later, the more recent articles from the same Scopus list, even with low citations but relevant to material information management, were selected to review their applicability for material passports. To further review the blockchain-based technologies mentioned in those articles, a few knowledge articles from institutional websites of such technologies have also been reviewed. In this case, relevancy was the focus instead of the article publication year, and articles from 2017 to 2025 have been selected. A total of twenty articles were reviewed to study blockchain aspects. However, there was an overlap between the literature previously selected for DTs and MPs, and five articles were relevant to both streams of study.

Altogether, 37 articles have been reviewed to present the key findings of the papers, with additional articles reviewed to establish the review background and support the findings in the discussion. As previously discussed in this section, the literature selection was not fully systematic and exhaustive, but has rather tried to include significant items based on their contribution to the research topic [31,32,33]. To overcome the limitations of the selected literature not being exhaustive, efforts have been made to review a wide range of literature, starting with academic literature database, but also including grey literature. Given hat this is an emerging topic being researched in different quarters of academia and industry, including areas outside of construction, this study focuses on research within the construction sector, as it has been the key sector for research and adoption of MPs in recent years.

3. Blockchain Technology Application for Material Passports

3.1. Introduction of BIM, Digital Twin and Blockchain as Tools for Material Passports

Upon reviewing the relevant literature, BIM has been identified as the most widely adopted tool in the construction industry. The application of BIM starts with the development of digital models of buildings, which contain the physical properties about material in the modelled building component. Physical properties of the material are the basic information that goes into MPs [14,36]. In the design phase, BIM can be integrated with life cycle assessment (LCA) data and tools to determine the environmental scores and compare different design alternatives accordingly [37].

In later stages, BIM is used to model the asset’s lifecycle, trace any changes to any material and enable optimised operation of assets [16]. BIM models utilised for project management at early stages are supplemented with details about as-built work and handed over. A digital twin (DTw) is one of way of handing over as-built information from the BIM model after construction completion in digital form [16]. Such a DTw model not only keeps records of geometric and material data but is also a dynamic model allowing simulation analysis of performance, corresponding to any changes in materials or conditions. In other words, a DTw is the continuation of the BIM model into the post-construction stage. While BIM and DTw are the main information management tools for information creation and analysis, there are other digital tools used in information creation and analysis for BIM and DTw models. However, various studies have identified the shortcomings of BIM-based centralised information management, such as vulnerability to data tampering, and the resulting lack of trustworthy collaboration between dispersed supply chain stakeholders, both across horizontal supply chain and throughout the longer lifecycle [38]. The need for a decentralised system was also discussed in Section 1. Blockchain technology (BCT) has been proposed as one of the solutions to such information management issues in the construction industry [38].

BCT stands out for its application in the construction industry for information management (including models and descriptive information) because of its immutability and transparency features [29]. The application of BCT has been suggested due to the necessity of security and transparency of information management required in the dispersed supply chain [24] and for managing asset information throughout a longer lifecycle [39]. As BCT is a decentralised database, which is functioning within a peer-to-peer network under a consensus mechanism, it maintains the integrity and accuracy of the data [29,40]. BCT, abetted by smart contracts, enables tracking of material information throughout lifecycle stages [16]. The immutability feature of BCT also helps reduce the lengthy documentation process otherwise required to ensure security and transparency of information records throughout the lifecycle [8]. BCT itself does not generate data but is useful for managing data while using BIM and DTw as the central platform for visualisation, analysis and sharing of data [14,39].

Therefore, with the integration of BCT with BIM and DTw, the key requirements for MPs such as storing and updating of information, managing operation and usage of information throughout the lifecycle, secure information storage and update, transparency in information management, immutability in information management, and sharing of information [36,41,42] can be achieved. This is discussed further in the following Section 3.2.

3.2. BIM, Digital Twin and Blockchain: Features and Synergies for Material Passports

3.2.1. Features of BIM and Digital Twin Enabling Material Passports

BIM undertakes the development of building information about the construction and operation of an asset in a digital format. It adopts an object-oriented approach for model development [43], which means the digital model of any component contains information about both its attributes and functions, designed in way that makes it reusable as modular components. Any model contains both graphical and non-graphical information required to describe material properties and function [43]. BIM models are created in different file formats, and Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) are an open international standard that allows development of models in IFC file format, which is interoperable among all BIM platforms [44]. IFC also defines a data schema that structures information on any physical element being modelled, consisting of data about identity, physical characteristics, relationships with other elements, object type, processes driven or enabled by the product, quality and cost information and supply chain actors involved [45]. The information about every other type of object can be coded using the Uniclass system, which allows the classification and organisation of any built environment information at any stage of a lifecycle for different scale of projects with a consistent approach [46]. It makes it easier to identify and refer to information about any building element. Information management for BIM models and processes is undertaken as outlined by ISO 19650 [47]. The digital BIM models created for a project, which store information about materials obtained from manufacturer or as built in the project, are known as the project information model (PIM). Such a model is supplemented with necessary information for operation and maintenance and handed over to the owner as asset information model (AIM) [47]. Thus, a BIM model can consist of all necessary information for MPs of any product, required for its construction, maintenance and next use at the end of its lifecycle, thereby facilitating the implementation of circular economy practices at all stages of the lifecycle [16].

While BIM enables static modelling for information management in all phases of an asset’s lifecycle, a DTw makes the processes more detailed with its dynamic modelling. A DTw represents how the entity behaves and how it reacts to an external stimuli [48]. Any DTw requires a physical asset and a sensor network, where real-time information is transmitted from the physical asset to the virtual twin, which helps monitor and optimise the functioning of the physical asset [49]. For an advanced DTw, physical models respond to results fed from the analysis of information from sensors. In addition to any temporary responses in an asset, such as a change in the indoor environment, any permanent changes resulting from maintenance actions are also updated in the digital model [50]. The real-time information about physical assets helps in decision-making for smart asset management, maintaining energy efficiency and reducing consumption [51]. Thus, DTw facilitates managing dynamic information for MP systems, i.e., information that can vary during the lifecycle, such as energy consumption and material changes like maintenance or repair.

BIM and DTw can make sure all necessary information required for MPs are recorded into the models and related information containers. As discussed in the Section 3.1, BIM and DTw do not guarantee a secure, immutable and transparent information management required for MPs in construction, which can be achieved by adopting blockchain, and is discussed in the following Section 3.2.2 and Section 3.2.3.

3.2.2. Features of Blockchain Technology Enabling Material Passports

BCT can provide this platform for information management and ensure trust in the stored information through a system-based approach rather than conventional relation-based approach [52]. BCT can securely manage project data while incorporating smart contracts to keep an automatic record of information transactions and ensuring that necessary procedures are followed [29]. Information in BIM common data environment (CDE) contains all information transactions and enables transparency in the process during the design and construction phases, which is mostly maintained by the entity responsible for asset development. However, as the ownership of the asset changes during the lifecycle, the common data environment maintained by such and entity might be disbanded [21]. Changing the ownership of materials at different stages of the lifecycle makes it difficult to keep reliable and up-to-date records of material information when the information is centrally managed [26]. Using BCT, on the other hand, can provide traceability of any changes made to information [53]. Lee, et al. [54] distinguish how a DTw updates the BIM model in real time with the use of sensors and how blockchain can authenticate the transactions in the DTw with timestamps and a secured record of the process. As an integral component of a blockchain-based system, smart contracts can be employed for triggering the recording of transactions when compliance with any information update is achieved [55].

3.2.3. Synergies Between Technologies for Material Passports

As discussed earlier in Section 3.1, some requirements of MP systems, presented in Table 1, match the requirements for the technologies (BIM/DTw/BCT) which cover each requirement. While the information creation is done through BIM, storing, updating, and sharing can be done through BIM and DTw, with BCT as an additional component. However, security, transparency and immutability are key functionalities achieved via blockchain technology.

While the integration of BCT with BIM and DTw appears to offer a promising solution for information management for MPs in construction, there BCT has limitations which are to be considered while designing the MP information system. The following Section 3.2.4 delves into these aspects.

3.2.4. Blockchain Limitations to Be Considered in the Design of Material Passport System

Regardless of the suitability of BCT for MPs, there are different aspects of BCT to be considered before its adoption, as blockchain has limitations regarding performance and scalability [29]. While decentralisation and immutability are key features contributing to MP requirements, they hinder design aspects such as the developability and maintainability of the system [24]. Blockchain systems are inherently complex to develop and demand more time and cost. Therefore, while designing the MP system, the type of blockchain platform and the consensus mechanism should be chosen based on how the system can meet its requirements. The key requirements of MPs, as mentioned in Table 1, must be achieved while making sure that the system is feasible to develop and maintain.

In a permissionless blockchain network like Bitcoin, with consensus mechanism like proof of work (PoW), a lot of energy is required to conduct the calculation for PoW. Also, it takes around 10 min to add blocks, and the size of one block is around 1.7 MB (as of 2024). Adding a high number of blocks about MP records in this type of network would require a lot of energy and processing time [56]. Also, maintaining a large storage space in all nodes of a public blockchain would significantly increase the cost and energy of maintaining the network [29]. When it comes to blockchains like Ethereum, with consensus mechanisms like proof of stake (PoS), the energy spent to add blocks is low, but performance is still slower. AS a public blockchain, there are a large number of nodes with sufficient stakes to decide the addition of a new block. It has a similar issue with the larger storage required, as running bigger storage on all the nodes would be costly and energy-consuming.

Table 1.

MP system requirements fulfilled by BIM, DTw and BCT.

Table 1.

MP system requirements fulfilled by BIM, DTw and BCT.

| MP System Requirements | Digital Technologies | Source Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Information creation | BIM | [14,36,43] |

| Storing of information | BIM | [16,57] |

| DTw | [16,48] | |

| BCT | [16,40] | |

| Update of information | BIM | [16,44] |

| DTw | [37,48] | |

| BCT | [16,40] | |

| Managing operation and usage information throughout lifecycle | BIM | [16] |

| DTw | [37,49,50,51] | |

| BCT | [16,40] | |

| Secured information storage and update | BCT | [14,40] |

| Transparency in information management | BCT | [39,40,53] |

| Immutability in information management | BCT | [40,54] |

| Sharing of information | BIM | [16,44,57] |

| DTw | [16,37] | |

| BCT | [40,58] |

In a permissioned private blockchain, only selected nodes are allowed in the consensus process, which makes it efficient performance-wise and consumes less energy [56]. The limited number of nodes allows maintaining a system which can manage a larger amount of data. However, this type of governance mechanism is suitable only for processes within an organisation. Consortium blockchain on the other hand is partly decentralised, as there are preselected nodes in the consensus process, but the nodes belong to several organisations [29]. This type of blockchain can represent an industry or market sector as the nodes can belong to the key organisations involved in the supply chain, which helps maintain a checking mechanism before adding information to the blockchain. Such a limited number of nodes would always be online and can quickly record the relevant MP transactions. While being governed by a group for checks and balances, it provides performance and scalability. A limited number of resourceful nodes also makes the system feasible to develop in terms of cost and infrastructure. As consortium blockchain developability and performance seem to suffice for the requirement of an MP system, it would be the most suitable choice for MP management and will be discussed further along with the conceptual model.

Apart from the above, the immutability of blockchain-based systems also hinders system requirements like modularity, required to modify and replace individual modules like smart contracts. In case of long-lived assets where there might be changes in governance and access rules, the immutability of smart contracts does not allow changes at the protocol level to modify smart contracts [59], which necessitates extensive reviews before deploying the smart contract. A solution to that issues is to deploy an upgraded superseding smart contract, which is changed at the architecture level where new smart contract is introduced and governance change is required to redirect the users to the new smart contract [60]. Similarly, if there are changes to MP-relevant information on materials, records of previous versions cannot be removed from the blockchain when new records are added. Immutability causes similar issues when incorrect material information is added to the system and cannot be removed—only new entries with correct information can be added. The duplication issue must be avoided by instructing users to refer to only the older versions. Nevertheless, storage space will still be occupied by the older versions.

Apart from the above-discussed features to be considered for design, development and maintenance of a blockchain-based MP system, inherent failure modes of the blockchain should also be considered when choosing the blockchain and platform type, especially given the system’s necessity for a longer built asset’s lifecycle. In the PoW mechanism, if a mining pool of miners joins together and exceeds 51% of the computing power, they can take control of the blockchain [61]. A similar takeover can also occur when handful of entities control a large portion of stakes in PoS chains. Forking of the chain is another issue that can lead to blockchain failure when the forks are contentious. For example, when new rules are not agreed upon by all the nodes, and some nodes fail to update the agreement and continue to operate with previous rules, the existing chain is split [61]. This creates two chains vulnerable to majority attack and confuses users as transactions might be replicated, leading to users, and eventually developers, quitting the platform. Too much centralisation of power through the concentration of tokens or mining power by a few agents, termed “whales”, can also influence the governance decision making in the blockchain in favour of those agents. This can create discontent and lead to forking of the chain, eventually resulting in to failure [62]. Considering the longer lifecycle of the built asset, node attrition is another blockchain failure that should be considered, as nodes might not be able to sustain the hardware requirements for blockchain network in the long run. Additionally, the reduced incentives to maintain nodes, for example, when tokens are not worth the cost of maintaining the nodes, result in nodes leaving the network [63]. Forking, as discussed above, is another reason for node attrition.

Most of the failure modes discussed above are prevalent in permissionless blockchain like PoS and Pow where anyone is allowed to join the network. However, consortium blockchain types discussed previously as fit for an MP system based on developability and performance are also fit to tackle the failure modes discussed above. The nodes are maintained by the agents, which are key organisations involved in production and regulation in industry supply chain and are known to each other. The rules for adding records for MP information are already defined and so are the responsibilities of nodes. The network is maintained based on the agreement among the parties to fulfil the requirements of a decentralised MP system. There are no clear scenarios when the nodes would try to takeover or fork the chain. The infrastructure is also funded and maintained as part of the MP system. The incentive is to maintain authentic information on material utility and its quantity in any given region, supporting trading for material circularity. Further details of the consortium blockchain-based mechanism are provided later in the discussion of the conceptual model.

Lastly, another major limitation of blockchain to be considered is storage capacity. The storage space is limited and only records of MP data should be maintained, while for the detailed MP data, i.e., BIM models of larger sizes, it becomes imperative to find a feasible way to store larger size files containing material information secured by using BCT, although the complete data itself is not stored in the blockchain network. This aspect is further discussed contextually in Section 3.3 and Section 4. Section 3.3 also reviews and synthesises several existing studies that investigate BCT for material information management in construction to highlight the key research gap in this study.

3.3. Review of Existing Literature on Blockchain Applications for Material Information Management

There are existing studies on the application of blockchain for material information management in construction supply chains, as well as in the production and maintenance phases. These studies are reviewed in this section to understand the exact applications of blockchains, identify any research gaps and establish how existing research could be extended to propose a blockchain-based MP system for material circularity. The summary of the discussion on adopting different blockchain platforms and information management processes required for MPs and circularity are presented in Table 2 and discussed in detail in different sub-sections representing different themes identified in the literature.

Table 2.

Analysis of studies on blockchain adoption for information management.

3.3.1. Theme 1—Blockchain-Based MP System for Entire Construction Supply Chain

Incorvaja, et al. [25] discussed how blockchain can be used for MPs to support material provenance. They developed MPs considering the whole of the supply chain, involving actors external to the project organisation, such as manufacturers, suppliers, and government authorities. The Ethereum-based blockchain platform is about the transfer of ownership of materials. Wilson, et al. [26] is another study on the use of BCT for information management for MPs at a larger supply chain scale. Three main stakeholders were identified by them in the broader supply chain: the manufacturer, the logistics supplier and the construction company. Based on the Polkadot blockchain platform, their study assigns each stakeholder a smaller, independent segment of a larger blockchain network, called shards, which operates as its own small blockchain. They proposed to store detailed data about the material using the InterPlanetory File System (IPFS). Storing detailed material information in a larger file in a database outside of the blockchain is called off-chain storing of information. IPFS, adopted in this case for off-chain storage, is a distributed file system that can be used to create a decentralised and efficient method for storing and sharing files online [69]. Storing information within the blockchain itself is called on-chain storage. Wilson, et al. [26] proposed on-chain storing of the Content Identifier (CID), which is hash of files stored in IPFS and allows tracing the file stored in IPFS. The information stored both on-chain and off-chain form MPs. Mankata, et al. [64] suggested using blockchain to tackle data fragmentation issues in the construction supply chain. A suggestion for a blockchain-based web marketplace has been put forward, where different stakeholders, from manufacturers to users, can participate to store and share material information. The product description must be recorded in the blockchain itself, although the use of off-chain storage for project documentation and multimedia files has been suggested. Mankata, et al. [64] presented a proof-of-concept prototype in the Ethereum platform including a side chain for carrying the material marketplace tasks, which is later bundled together into blocks in the main network, but the type of off-chain storage is not mentioned. While all these studies intend to enable MPs in the construction supply chain, information management for MPs throughout the built asset’s lifecycle has not been considered.

3.3.2. Theme 2—NFT-Based Material Passports

Hunhevicz, et al. [21] on the other hand suggest blockchain use for managing information for longer lifecycle of the asset, in addition to supply chain. Gaia decentralised storage has been selected for user-controlled off-chain storage of information, where the location of data storage can be chosen and data stored on Gaia can be mapped to on-chain ‘Stacks’ identity. This study explored a different approach to information ownership/mapping based on assigning a Role or a Non-Fungible Token (NFT) to an address. However, this study only presents different cases for the application of role-based access and token-based access of data in a blockchain network and does not propose possible stakeholders involved and the processes required for information management throughout supply chain and the lifecycle. Another study suggesting the use of NFTs for products passports is Byers, et al. [65], which proposes the tokenisation of the set of digital information on any physical asset to develop a tokenised product passport of the physical asset being represented. Although lifecycle management of information has been suggested, where token’s metadata would contain links to off-chain storage of data too large to be stored on-chain, the possible options for off-chain storage have not been discussed. A similar study by Wu, et al. [66] also suggests the use of Hyperledger fabric blockchain-based NFTs to enable construction waste MPs to track and transfer the ownership of waste across different jurisdictions. A typical token developed using Hyperledger fabric is fungible [70]. Therefore, Wu, et al. [66] suggested assigning a unique identifier to prevent duplicated issuance.

3.3.3. Theme 3—BIM and Blockchain Integration for Information Management

Different authors have highlighted the risks of centralised information management and introduced the integration of blockchain-based technologies into existing tools like BIM CDE to make the system decentralised, transparent and secured [28,67]. For example, Tao, et al. [28] suggested the use of blockchain and IPFS for design data management to overcome possible issues with centralised design data. They suggested recording all irreversible design changes in the blockchain, while the actual files would be saved in IPFS. All ‘work in progress’ information containers are also uploaded into IPFS for other parties to review and add to. The uploader of files into IPFS will also upload the CID and other metadata of the files into the blockchain via a smart contract. The blockchain platform suggested here is Hyperledger fabric, and stakeholders in the design process act as nodes of the blockchain network, thus having access to the metadata stored. Also, the design parties are peers in the IPFS network, and by using the CID from blockchain, they can access the file from IPFS. This way, the files can be shared in CDE, as well as reviewed and updated.

Similar to Tao, et al. [28], Jaskula, et al. [67] proposed an approach of using blockchain, IPFS and smart contract integration with BIM CDE for information management throughout the lifecycle of the built asset. They suggested the adoption of Hyperledger fabric for an enterprise blockchain network, and a similar process using BIM CDE, IPFS, blockchain and smart contracts, as discussed above, has been adopted for information management. In a later study by the same authors, Jaskula, et al. [68] presented a prototype integrating IPFS into CDE information management, as discussed above. While Tao, et al. [28] focused on managing information during the design process, Jaskula, et al. [67] focused on the handover of information between stakeholders at different stages of asset’s lifecycle to deal with the issue of probable breaking of information chain, and integration of information from different tools and platforms used along the lifecycle of the asset. Bucher, et al. [71] conducted a study suggesting different decentralised data networks for lifecycle information management, where network selection is based on the features required, like immutability and privacy. However, the use of blockchain along with the data network has been reiterated as a necessity to meet the use case requirements for data management in a built environment.

3.3.4. Research Gap

Various possible techniques for application of BCT in the construction sector are discussed in the above Section 3.3.1, Section 3.3.2 and Section 3.3.3. Some studies focused on information management for material passports, whereas some focused on decentralised information management required for fragmented supply chains in the construction sector, and some covered both. These studies highlight the need for blockchain-based MPs throughout the supply chain. Any developed MP system should be possible to implement at the industry level. In this way, the data on materials, right from virgin extracted materials to constructed building elements can be managed in a trustworthy manner. Among the above-mentioned studies, Tao, et al. [28], Jaskula, et al. [67], and Jaskula, et al. [68] suggest integration of blockchain into managing the BIM CDE itself. However, with an already existing industry-wide blockchain system, necessary for data reliability, the MPs of built asset elements can be developed within the existing system. In such cases, the management of built asset lifecycle data, as developed in BIM CDE of the built asset and managed through such blockchain systems for MPs, is the subject for this study. The focus is on the processes within BIM CDE and interaction between CDE and MP system including stakeholders involved. Although the information during asset delivery is the main source of information for MPs, to achieve material circularity, the material information updates throughout the lifecycle also need to be considered. The actors and their responsibilities at each stage of the lifecycle need to be outlined. The MPs, once created with as-built asset information, should be up to date with the as-is information on the asset [41]. This study builds on these existing works and adapts the concept of integrating BIM and blockchain with off-chain storage, with attention on MPs for elements at the built asset level. In addition to BIM and blockchain integration, DTw has been considered as the dynamic post-construction BIM model and an integral component for managing information for MPs throughout the built asset’s lengthy lifecycle. To address the realised need for a blockchain-based MP system to manage authentic information on material throughout the asset’s lifecycle, based on the synthesis of blockchain adoption ideas above, this study proposes a conceptual model for a blockchain-based MP system, which is discussed in detail in the following Section 4.

4. Conceptualising Blockchain-Based Material Passport System with Building Information Modelling and Digital Twin

4.1. Blockchain, BIM and DTw Integration for Material Passports of Built Asset Elements

In the literature discussed in Section 3.3, blockchain has been recognised as necessary throughout the lifecycle to ensure that trustworthy information on construction materials and products can be maintained in the dispersed construction supply chain. The actors in the supply chain, such as manufacturers, suppliers, logistics teams, contractors, users, and others, are responsible for managing information in the blockchain [72]. While the information on materials needs to be tracked early, from extraction or manufacturing, blockchain-based systems, BIM and DTw comes into play when the information to be managed relates to a specific built asset. As BIM and DTw are used for the creation and management of information within a project and for the built asset throughout its lifecycle, the mechanism used for the transfer of information to and from the blockchain to the BIM environment for the purposes of MPs should be clearly outlined.

In the case of BIM, ISO 19650 defines BIM common data environment (CDE) as the agreed source of information for any asset or a project. It is where information containers are collected, managed and shared from, while adopting standard procedures [47]. Information containers, as defined by ISO 19650.1, are retrievable sets of information, which can be information files (model, document, schedule) or subsets of an information file (section, layer). Such information containers are the source of information for MPs of built assets. Any built asset’s material and products information recorded for MPs is the product of the BIM CDE workflow. Thus, a blockchain-based system is part of the information management process in line with ISO 19650 and is applicable for information management throughout the lifecycle of the built asset to ensure trust and transparency. The information requirements are defined for the project based on the necessities for MPs. The BIM project information model (PIM) [47], also defined in Section 3.2.1, is developed during the project delivery phase, in accordance with the information requirements developed for the MPs. Similar requirements are maintained for DTw too, as DTw is the asset information model (AIM) developed for the operational phase [47]. In conventional BIM, there is CDE archiving, which involves keeping a journal of all information transactions (archiving) to maintain an audit trail of information container development. Authors Tao, et al. [28] and Jaskula, et al. [67] suggest using blockchain-based record-keeping for the archiving process for inter-organisational purposes. However, in the case of industry-wide blockchain-based MPs, only the final version of information about the materials used or built is required. While the PIM is subjected to change during the construction phase, only the as-built information developed for AIM is needed for asset operation and maintenance, as well as for trading at the end of the asset lifecycle. Material circularity is supported by the final information about the building element as constructed and repaired. Therefore, MPs are created for the final constructed building element by sourcing files containing material information published in BIM and indexing these files and records of the published information containers of the corresponding element in the blockchain. This usually represents the as-built information for the AIM. The final as-built information is also incorporated into the DTw, which is maintained throughout the operation phase. Any significant update on the AIM based on DTw modelling, representing changes in assets, would also be registered as MPs.

4.2. Actors and Lifecycle Stages of Information Management for MPs at Built Asset Level

In addition to the CDE concept, the actors responsible for information management for a built asset are also derived based on the hierarchy described in ISO 19650. Different parties in the information management process, as outlined in ISO 19650.1, are briefly discussed below:

- Appointing party: The client or someone managing information on behalf of the client, is responsible for managing CDE and is the final authority of the process [73].

- Appointed party: They are providers of information, and in case of a ‘delivery team’, a ‘lead appointed party’ is identified to interact with the appointing party. Guidance 2 [73] mentions that the ‘lead appointed party’ is appointed by the client for works like architecture, engineering, project management, construction, etc., and the former appoints further appointed parties as required for the delivery of works.

- Delivery teams: As mentioned in ISO 19650.1, a delivery team comprises the ‘lead appointed party’ and their appointed parties. However, its size can vary from a single individual conducting all functions to multiple ‘task teams’ working on different assigned tasks, depending on the size and complexity of the project.

The latter two actors are responsible for carrying out all processes of sharing, coordinating, reviewing and revising until the information is agreed upon by the required task teams and/or delivery teams and, finally, by the appointing party. The RIBA plan of work provides a comprehensive list of outcomes at each stage of the construction lifecycle and is used as the standard in this study to determine different actors that are involved in information management. Those actors have been identified in terms of the delivery teams that are responsible for the outcomes, as outlined in the RIBA plan of work. Delivery teams are the focus here, as the information creation and updating is the function of such teams in BIM-based information management, which are then taken for MPs. Those actors vary across different phases of the lifecycle, as the type of work to be delivered also varies. Such actors (delivery teams) and the tasks to be performed across three overarching lifecycle phases have been obtained by adapting the RIBA plan of work [74] lifecycle stages and their core tasks and are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Different tasks and stakeholders during the lifecycle phases in line with RIBA stages.

Table 3 identifies different tasks that are undertaken at relevant stages (RIBA stages 2 to 6), which indicate the type of actors involved and information created at each stage. Lifecycle stages prior to concept design (i.e., Stage 0, Strategic definition, and Stage 1, Preparation and briefing) do not create any substantial information that would be included in MPs. The ‘end of life’ phase is not considered in the RIBA plan of work [74], but it is crucial for circularity and has therefore been added to identify the tasks and actors associated with this stage. The actors discussed above are responsible for managing information at the mentioned lifecycle phases and thus contribute to creating and updating MPs for the built asset. The MP information on different materials as provided by the manufacturers and suppliers is utilised by the actors within project organisation when they create information about the built asset elements. BIM CDE workflow involving multiple actors is adopted to finalise the information. The final information published for any built asset element is taken into the MP of the element.

During the design phase, particularly the technical design stage, information contributes to the development of MPs, which are primarily applicable to sustainability and circularity assessment of the design and construction. Although the information contributes to the design of circular built assets, it remains subject to change and therefore does not represent the final information for material circularity. The architecture and engineering design teams act as the delivery team stakeholders responsible for creating information relevant for MP. It is during the end of manufacturing and construction phase that the material information is finalised and ready to be added to the MP system for material circularity purposes. The manufacturing and construction teams are the main delivery teams for information creation or update in this stage. Moving on to the use phase, the asset management team is the information delivery team responsible for MP-relevant information updates, which would involve any small-scale changes undertaken by the team within the organisation. In case of significant repairs undertaken as a project, the information management for the delivery phase, as outlined by the ISO 19650, will be applicable and will follow the process for the design and construction phase. In all phases, the appointing party, typically the asset owner, verifies the information before it is stored in the MP system. During end-of-life stage, any updates to existing MPs or the creation of new MPs required for material recovery are undertaken by the deconstruction team. Interested buyers subsequently obtain the information from the MP system. The conceptual model representing these processes, including the actors and technologies involved, is presented in the following Section 4.3.

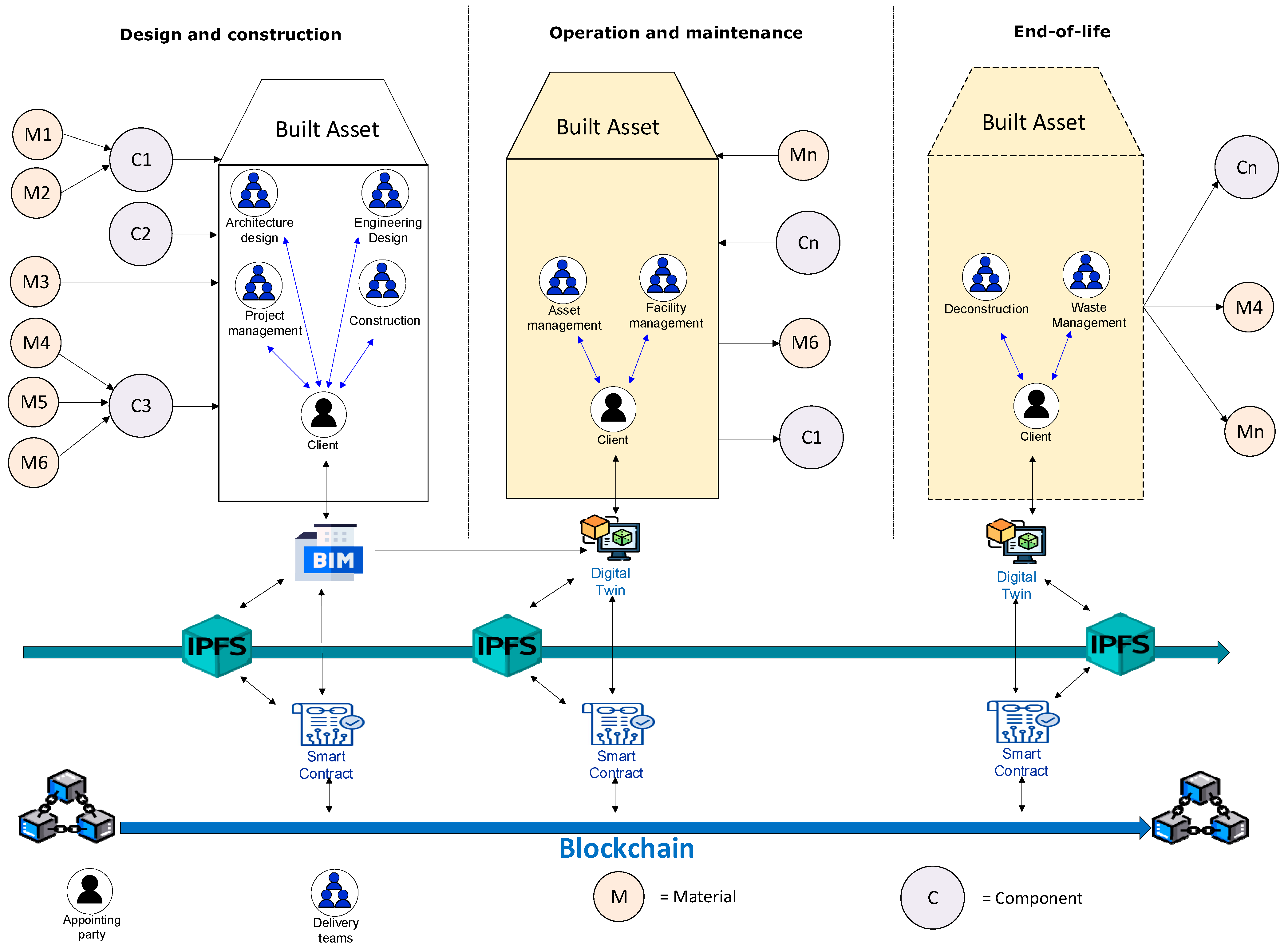

4.3. Conceptual Model of Blockchain-Based Material Passport System

The conceptual model is the outcome of the critical literature review, synthesising the blockchain, BIM and DTw aspects proposed by other researchers. As discussed in earlier sections, MPs are intended to exist throughout the supply chain, from material manufacturing to reuse [25,26]. It would also include the virgin raw materials extracted to comprise the entire supply chain. Such raw materials are used to develop components (products), and both are used to construct built assets. Typically, for any built asset, the materials and components accumulate during design and construction. The accumulation and dispersion of materials both happen to some extent during the operation phase, and the dispersion of materials takes place in the end-of-life phase. The integration of blockchain and BIM, as discussed above, when visualised alongside material flows across the supply chain throughout the asset lifecycle, can be represented as shown in Figure 2, illustrating the blockchain-based MP system. It shows the flow of materials at different stages of the asset lifecycle. The MPs would be developed accordingly, with MPs for market items developed by producers/manufacturers, and MPs of built asset elements by actors and processes, as discussed in Section 4.1 and Section 4.2. The MPs of the built asset elements would be linked to material passports of the materials and products utilised to construct the element. Similarly, the MPs of reclaimed materials at the end-of-life stage would also be linked to MPs of the built asset elements from which they are sourced. The different actors involved at each lifecycle stage are also represented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Conceptual diagram of blockchain-based material passport system.

As further suggested by Wilson, et al. [26] and Hunhevicz, et al. [21], the MPs are created in supply chain comprising both the decentralised off-chain storage, where the detailed material information is stored, whereas the on-chain storage would only store the index of such information. InterPlanetory File System (IPFS)-based off-chain storage [26,28,67] is chosen for this purpose, as it can be independently developed and implemented by industry stakeholders. The IPFS would exist alongside blockchain as an inherent part. Detailed information on built assets would also be stored in the IPFS alongside BIM models, as decentralised storage enables secured and trustworthy information management. This approach eliminates the risk of a single point of failure and allows detection of any data tampering. The smart contracts created would allow us to add data and read it from the blockchain. The user, which in case of a built asset would be the appointing party, would have access to the blockchain-based system to add the data to IPFS and the blockchain. The BIM IFC files [45], populated with all the information required for the MPs, are stored in IPFS. Since they are interoperable file formats and can run on different BIM platforms, this would enable probable future users to easily access the information about the materials. In Figure 2, BIM represents the project information model (PIM) during the design and construction stages, which forms the MPs developed for circularity assessment during the delivery phase. Upon handover, once the as-built asset information model (AIM) is developed, it becomes the source for the finalised MPs. MPs created for any built asset element consist of the detailed material information stored in IPFS, and the corresponding CIDs, BIM metadata and unique identifier added to the blockchain, thereby creating an indexing for the information. Furthermore, the digital twin (DTw) serves as the dynamic AIM of the built asset during the post-construction stages of its lifecycle, and the updates made to the AIM of a built asset element are also reflected in the MPs for that element. Each update would retain the previous version, and new version would be added to the MP system. During the retrieval of information during the end-of life stage, the CIDs of files stored in the blockchain are compared with the rehashed CID values of the IPFS files to verify file integrity. Once verified, the files are considered authentic and can be retrieved as MPs.

5. Discussion

The conceptual model for the system, developed based on the relevant research to date, is also proposed for further evaluation and development. The existing idea of for blockchain-based material passports has been enriched by incorporating BIM and DTw aspects to outline the creation of information and MPs at the built asset level. However, many aspects still require further research to develop a complete MP system, ranging from decisions regarding the detailed use of technologies to administrative aspects of information management.

The blockchain network adopted for the system must consider implementation aspects, such as the ability to deploy smart contracts and accommodate larger volume of data across the prevailing network types. Financial and energy consumption considerations also need to be optimised. Given the large volume of data, consensus mechanisms that require longer transaction processing times would not be suitable from a performance perspective. Moreover, using a network that requires transaction fees is not feasible given the scale of information. Privacy must also be considered, as information about the private properties of built asset owners needs to be managed. Different privacy and access levels must be assigned for different users and types of information. Considering these factors, and as discussed in Section 3.2.2, a consortium blockchain [29,30] managed stakeholders with access to built asset information, such as building regulation authorities, seems to be a feasible solution, but it requires further research and market study. Similar considerations apply to IPFS storage, which must also be developed with authorised parties acting as the nodes for the network. Since built asset data must be maintained over longer durations, typically around 30 years or more [75], the system requires a durable infrastructure to support its development and operation.

Given the need for a continuously available infrastructure, the blockchain-based system is only feasible if many industry stakeholders, including entities with a permanent presence, such as government authorities, collaborate to provide the decentralised infrastructure for blockchain and IPFS. This approach requires policy-level action for the circular economy, consistent with the idea that CE actions should be policy-driven, and led by government bodies [76,77]. Parties such as “building authorities”, who issue building approvals, conduct inspections for work quality and release occupancy certificates, can act as nodes for blockchain and IPFS. Multiple authorities from different government levels can collaborate to develop the networks. The authorities responsible for a region can store the material data for that region, and CIDs can be shared among the responsible parties, such as the ones mentioned above, at state or national level and with the asset owners [78]. As the data is only held by peers who already have authority over the asset and its data, the privacy of asset information can be maintained. Combined with the storing of such CIDs in the blockchain network, also maintained by similar authorities for material information record-keeping, the system would hold parties accountable for maintaining authentic information throughout the long asset lifecycle. Other aspects that require policy-level intervention include standardising MP requirement, such as content, and legislating aspects like the standard duration of storage and intervals of audits, to ensure all relevant information is recorded and updated as required throughout the lifecycle. These measures are necessary to enable scalable implementation across different regions with differing policies and practices.

Ownership of data should remain with the asset owner, even when it is stored within government-managed storage. The use of blockchain determines governance rather than the actors, and parties can rely on the system for data integrity. The managing of such a system, along with all associated infrastructure, needs sustained funding from government-level organisations, while part of the funding can come from fees charged to asset owners and the industry supply chain stakeholders. Determining the utility of materials at the end of their lifecycle would have to be regulated as mandatory before deconstruction, encouraging asset owners to adopt the MP system to maintain material data. The credibility of material utility information would enable the trading of such materials at the end-of-life stage, providing incentives for asset owners to use the system. This would enable both authorities to maintain the system and industry stakeholders to use it.

The conceptual model suggested in this review study could be an initial step towards further research into the exact components of the system. The exact network type, stakeholders and users of the system, and information governance aspects can be further studied based on the ideas conceptualised in this review study. The implementation can be done in phases. The main thing MPs rely on is the mature adoption of BIM, encompassing lifecycle management aspects from the outset. This also underscores the urgency of standardising MP content and integrating it into project and asset information requirements. Establishing government-managed blockchain and IPFS infrastructure will require intervention at the legislative and policy levels to support action towards circular economy. While these actions are necessary to initiate the MP system, in longer term it will also require revisions to information archiving and privacy laws to manage private information over periods exceeding four decades.

6. Conclusions

This study highlighted the necessity of creating material passports (MPs) to achieve circularity in construction. Building information modelling (BIM) was identified as the central digital tool for managing material information during design and construction, while digital twins (DTws) will help manage information during the use phase of a built asset. However, using BIM and DTw with an open-access MP platform based on centralised databases to manage material information throughout an asset’s lifecycle presents limitations in terms of security, privacy, and transparency, particularly among dispersed stakeholders across industry and over a longer asset lifecycle. Blockchain was proposed as a decentralised, immutable and transparent record-keeping mechanism to manage information in construction. Upon reviewing existing studies suggesting blockchain application for information management and MPs in construction, it was observed that although a blockchain-based MP system has been proposed for implementation throughout the industry supply chain, the managing of built asset information on such a platform throughout the asset lifecycle to obtain reliable data at the end of life is overlooked. Accordingly, the integration of blockchain technology with the BIM and DTw was proposed in this study to overcome the identified gap in managing MP relevant information at the built asset level throughout its lifecycle using the BIM common data environment (CDE) apparatus and the blockchain-based industry-wide MP system. In case of a built asset, information management must be designed for its lifecycle by considering all lifecycle processes, actors involved, technologies required and exact methods of information creation, update, and retrieval. Combining all these aspects, this study offers a conceptual model of a blockchain-based MP system.

The conceptual model is the outcome of a critical review of current research relevant to MPs and the implementation of BIM and blockchain in construction. However, there are limitations, as it is the result of an interpretive review leading to conceptual synthesis and lacks empirical validation. As a review, the scope of this study is to propose a synthesised model for further evaluation and development. Further development and validation would require prototyping and piloted implementation to validate the concept, understand its suitability and improve industry-wide implementation. Although conceptual, this review addresses practical aspects of BIM and blockchain integration for MPs in construction for material circularity, and the necessary collaboration required among government actors to make infrastructure and implementation feasible. The governance model discussed in this study requires further research based on input from industry actors. Understanding industry readiness and capacity building is another area of research to enhance the adoption of such systems in an industry with comparatively low digitalisation. Research can also be undertaken to facilitate policy formulation required for MP implementation. Therefore, this study can provide a foundation for future empirical and policy-related research on MP development and implementation in the construction sector. More broadly, it also contributes to knowledge development towards achieving circular economy in construction and supports the ongoing transition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K., S.S., S.P. and S.N.; methodology, A.K., S.S., S.P. and S.N.; validation, S.S. and S.P.; formal analysis, A.K., S.S. and S.N.; investigation, A.K., S.S. and S.N.; resources, A.K. and S.S.; data curation, A.K. and S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K. and S.S.; writing—review and editing, S.P. and S.N.; visualisation, A.K.; supervision, S.S. and S.P.; project administration, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Australian Government. Australia’s Circular Economy Framework: Doubling Our Circularity Rate; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2024.

- Global ABC. 2021 Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction: Towards a Zero-Emission, Efficient and Resilient Buildings and Construction Sector; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government. National Waste Report 2022; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2023.

- Heisel, F.; Rau-Oberhuber, S. Calculation and evaluation of circularity indicators for the built environment using the case studies of UMAR and Madaster. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.U.; Ng, S.T.; Antwi-Afari, P.; Amor, B. Circular economy and the construction industry: Existing trends, challenges and prospective framework for sustainable construction. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 130, 109948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munaro, M.R.; Tavares, S.F.; Bragança, L. Towards circular and more sustainable buildings: A systematic literature review on the circular economy in the built environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 121134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedir, F.; Hall, D.M.; Brantvall, S.; Lessing, J.; Hollberg, A.; Soman, R.K. Circular information flows in industrialized housing construction: The case of a multi-family housing product platform in Sweden. Constr. Innov. 2023, 24, 1354–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talla, A.; McIlwaine, S. Industry 4.0 and the circular economy: Using design-stage digital technology to reduce construction waste. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2022, 13, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck, S.; Dewil, R.; Allacker, K. Circularity and LCA—Material pathways: The cascade potential and cascade database of an in-use building product. In Proceedings of the SBEfin 2022 Conference on Emerging Concepts for Sustainable Built Environment, SBEfin 2022, Helsinki, Finland, 23–25 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Benachio, G.L.F.; Freitas, M.D.D.; Tavares, S.F. Circular economy in the construction industry: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 121046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, P.A. Waste to Wealth: The Circular Economy Advantage; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Leising, E.; Quist, J.; Bocken, N. Circular Economy in the building sector: Three cases and a collaboration tool. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 976–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luscuere, L.; Mulhall, D. Circularity information management for buildings: The example of materials passports. In Designing for the Circular Economy; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 369–380. [Google Scholar]

- Çetin, S.; Raghu, D.; Honic, M.; Straub, A.; Gruis, V. Data requirements and availabilities for material passports: A digitally enabled framework for improving the circularity of existing buildings. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 40, 422–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luscuere, L.; Zanatta, R.; Mulhall, D.; Bostrom, J.; Elfstrom, L. Deliverable 7—Operational Material Passports; European Union Horizon 2020 Framework; BAMB: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Çetin, S.; Gruis, V.; Straub, A. Digitalization for a circular economy in the building industry: Multiple-case study of Dutch social housing organizations. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2022, 15, 200110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourlens-Quaranta, S.; Carbonar, G.; De Groote, M.; Borragán, G.; De Regel, S.; Toth, Z.; Volt, J.; Glicker, J.; Lodigiani, A.; Calderoni, M.; et al. Study on the Development of a European Union Framework for Digital Building Logbooks—Final Report; European Commission Executive Agency for Small Medium-Sized Enterprises: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Karonen, C.; Gokarakonada, S. Unlocking the Potential of Digital Building Logbooks for a Climate-Neutral Building Stock; Buildings Performance Institute Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mulhall, D.; Ayed, A.-C.; Schroeder, J.; Hansen, K.; Wautelet, T. The Product Circularity Data Sheet—A Standardized Digital Fingerprint for Circular Economy Data about Products. Energies 2022, 15, 3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volt, J.; Toth, Z.; Glicker, J.; De Groote, M.; Borragán, G.; De Regel, S.; Dourlens-Quaranta, S.; Carbonari, G. Definition of the Digital Building Logbook—Report 1 of the Study on the Development of a European Union Framework for Buildings’ Digital Logbook; European Commission Executive Agency for Small Medium-Sized Enterprises: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hunhevicz, J.J.; Bucher, D.F.; Soman, R.K.; Honic, M.; Hall, D.M.; De Wolf, C. Web3-Based Role and Token Data Access: The Case of Building Material Passports. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computing in Construction, Crete, Greece, 10–12 July 2023. [Google Scholar]