Abstract

In the global wave of energy transition, ground-source heat pump (GSHP) systems are widely adopted for their ability to efficiently provide space heating and cooling. By utilizing stable shallow geothermal energy, these systems significantly reduce operational energy consumption in buildings, playing a crucial role in enhancing building energy efficiency and achieving low-carbon strategies. However, large-scale ground heat exchanger (GHE) clusters with non-identical circuits often face hydraulic and thermal imbalances, leading to degraded system performance. This study investigates the hydraulic and thermal behavior of a large-scale GHE system in Shandong Province, China. Hydraulic and thermal models are first developed based on Kirchhoff’s laws and the principle of energy conservation, and then used to simulate and analyze the influence of the number and depth of boreholes on hydraulic and thermal conditions. The results indicate that the flow imbalance rate and pipe length ratio follows a power-law relationship, δf = a (Lv/h)^b + d, with fitted coefficients, a = 0.0677–0.1294, b = −0.7086 to −1.0805, d = 0.0036–0.0921, while the heat exchange imbalance rate follows a linear relationship, δq = kδf + o, with k = 0.0906–0.265 and o = 0.0028–0.0039. Increasing the number of boreholes or decreasing depth exacerbates flow imbalance (10–58%), but soil thermal resistance dominates, limiting the increase in the heat exchange imbalance rate (2.2–9%). The formula and the quantitative relationship proposed in this paper aim to provide guidance for the engineering design of large-scale non-identical circuit GHE clusters.

1. Introduction

Ground source heat pump (GSHP) systems are widely adopted efficient renewable technologies for building heating and cooling. The core component is the Ground heat exchanger (GHE), which facilitates heat transfer between the circulating fluid and the soil. Currently, the global energy crisis caused by increasing demand is a pressing challenge [1], while the depletion of fossil fuels has intensified concerns regarding energy security [2]. Since the building sector accounts for a significant share of total energy consumption [3] and directly influences indoor environmental quality [4], the transition to efficient renewable solutions is urgent. Geothermal energy is highly valued for its vast reserves and stability, making GSHP systems a strategic choice for future energy supply [5,6,7]. Reducing carbon emissions is a major goal in modern development [8]. Thus, GSHPs are vital for achieving low-carbon and sustainable growth [9,10,11]. As of 2020, they accounted for 71.6% of the total heat pump installed capacity, demonstrating their dominance in geothermal energy utilization [12].

In these large-scale GHE networks, non-identical circuits are often adopted to reduce pipe investment costs. However, differing resistance levels in these circuits lead to hydraulic imbalances as the system operates over time. This causes actual flow rates to deviate from the design specifications, which ultimately degrades system performance. Consequently, mitigating these imbalances has become a primary focus for researchers [13].

A key strategy involves optimizing the physical characteristics of the pipes. Song et al. [14] found that increasing the diameter of horizontal pipes or shortening their length effectively reduces pressure drop by 17–21%. They suggest that ensuring Pdi < 400 Pa/m can minimize losses. The internal structure of the GHE also matters. Javed [15] compared different pipe types and found that coaxial GHEs demonstrate the lowest pressure losses. In contrast, pipes with irregular ridged inner surfaces or inserted fiber optic cables cause a sharp increase in pressure loss. These findings demonstrate that optimizing geometric dimensions and internal pipe structures is a fundamental measure to effectively reduce the hydraulic resistance of the system.

Beyond individual pipes, the overall network layout significantly impacts hydraulic stability. Zhang et al. [16] identified that vertical GHEs account for 80% of the total resistance in the pipe network. Their study highlights that optimizing borehole spacing is critical, with a 3 m spacing achieving the maximum performance coefficient. The connection configuration is equally important. Qi [17] compared series and parallel connections using numerical modeling. The results showed that the pressure drop in series connections is 19.85 to 36.0 times higher than in parallel ones. This indicates that parallel connections are generally more favorable for hydraulic balance under certain conditions.

Apart from optimizing traditional designs, new models are being developed to enhance efficiency. Agson-Gani et al. [18] proposed a novel semi-closed-loop double-tube concept. This design incorporates controlled fracturing at the well bottom. Although this method increases pumping power by about 28%, it significantly boosts heat extraction efficiency by 48% to 144% compared to closed-loop models. In summary, optimizing the pipe network connection mode and adopting novel GHE structures are crucial approaches for improving the hydraulic balance and heat exchange efficiency of GSHP systems.

In the application research of GSHP systems, heat exchange capacity significantly impacts overall system efficiency [19,20]. The heat exchange process between GHEs and the surrounding soil is relatively complex. The theoretical foundation for analyzing this process was significantly advanced when Kelvin proposed the linear heat source theory. This work was later extended by Ingersoll and Plass [21], who developed it into an infinite linear heat source model for the design of GSHP systems. To address the complexity of heat transfer both inside and outside the borehole, Zeng et al. [22] proposed applying the finite-length line heat source model to the external domain, while the internal borehole model evolved from a cylindrical source model to a quasi-three-dimensional model. Subsequently, Cui et al. [23] introduced a quasi-three-dimensional model incorporating variable borehole wall temperatures, further refining the modeling approach.

As rock and soil temperatures generally increase with depth, research attention has expanded to include medium-deep geothermal energy utilization. The classical linear heat source model overlooks the natural geothermal gradient. Consequently, researchers have developed various numerical models for medium-deep coaxial and U-tube heat exchangers [24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. However, considering the constraints of drilling complexity and cost in deep systems, Wang et al. [31] proposed the concept of medium-shallow depth GHEs and established numerical models for coaxial boreholes. Subsequently, Gao et al. [32] developed heat exchange models for single and double U-tube configurations in medium-shallow depth systems. In summary, theoretical models have evolved from classical analytical solutions to numerical methods adaptable to various depths. This progress establishes a comprehensive framework for accurately predicting GSHP performance.

To comprehensively evaluate the efficiency and potential savings of GSHP systems, priority must be given to two critical dimensions: hydraulic balance and heat exchange performance. Hydraulic balance primarily determines the pumping power consumption and flow uniformity of the GHE network. Heat exchange performance depends on the GHE’s capacity to transfer heat and mitigate thermal imbalance. These factors directly dictate the reliability and effectiveness of the underground loop. However, while previous studies have optimized these aspects individually, few have addressed the complex coupling effect in large-scale systems with non-identical circuits. In particular, research specifically investigating the impact of hydraulic imbalance on thermal imbalance remains limited.

Currently, in terms of system design, GSHP systems predominantly adopt non-identical circuits. For large-scale clusters with non-identical circuits, hydraulic and thermal imbalances are intertwined in the least favorable and nearest loops, significantly degrading system performance. In response to these challenges, this study utilizes actual construction drawings from a project in Shandong to construct a comprehensive model. Specifically, we establish a coupled hydraulic–thermal simulation framework that uniquely accounts for the hydraulic imbalance caused by non-identical branch lengths in large-scale clusters. Building on this framework, the study quantifies the coupling mechanism through explicit mathematical relationships that link the pipe length ratio to flow and heat exchange imbalances. Consequently, design-oriented empirical correlations are derived to incorporate frictional head loss variations. Unlike general theoretical models, these provide a more accurate reference for optimizing extensive GHE networks.

2. System Description

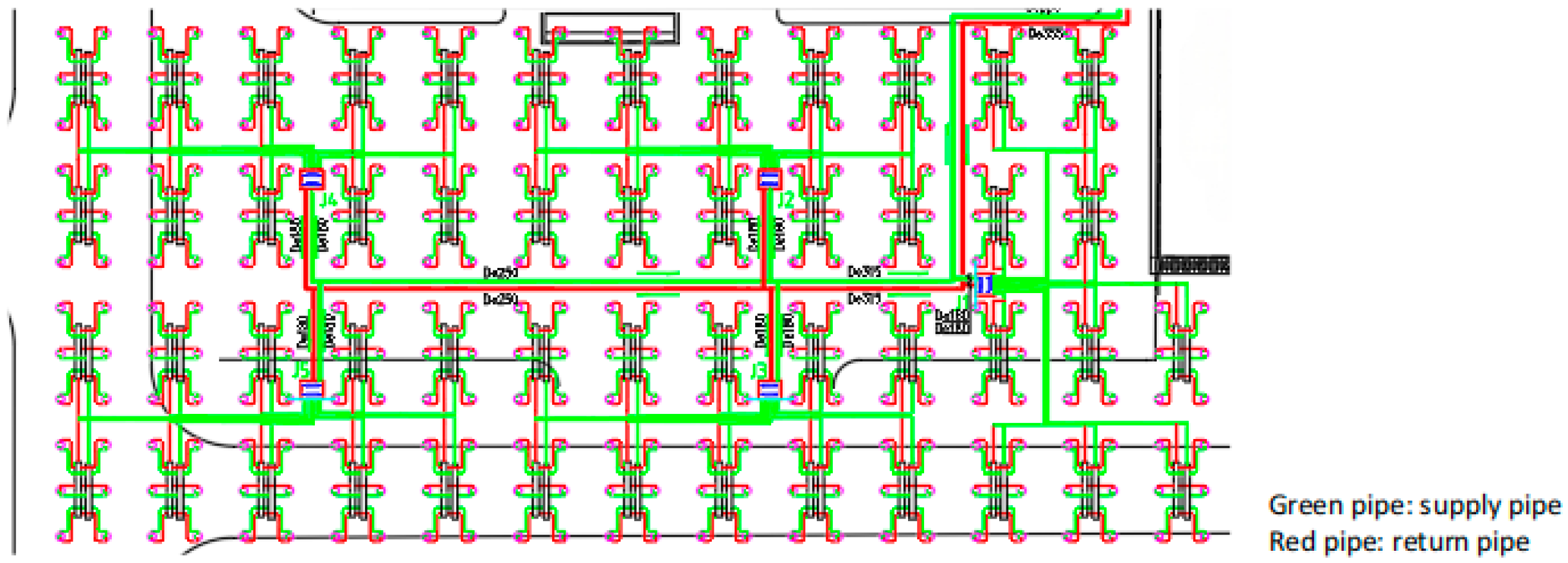

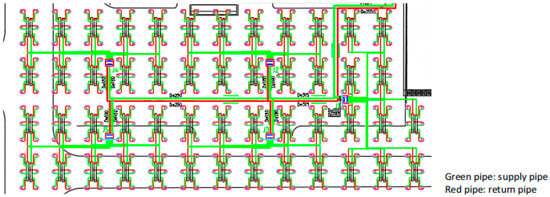

The GSHP system considered in this study is located in Dongying (118°07′ E, 36°55′ N), Shandong Province, China. A geothermal thermal response test revealed the thermal conductivity of the local soil and rock to be 1.833 W/(m·K), with a volumetric specific heat capacity of 1.885 × 106 J/(m3·K). According to GSHP engineering design specifications, the flow velocity in single U-tubes must not be less than 0.6 m/s. As shown in Figure 1, the project comprises 300 boreholes. Six boreholes are connected via manifolds to form a small cluster. Every ten such clusters are then connected to a distribution manifold, resulting in a total of five distribution manifolds for the system. Non-identical circuits are employed between the distribution manifolds, while the small clusters connect directly to them. The borehole locations are distributed as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Distribution of borehole locations.

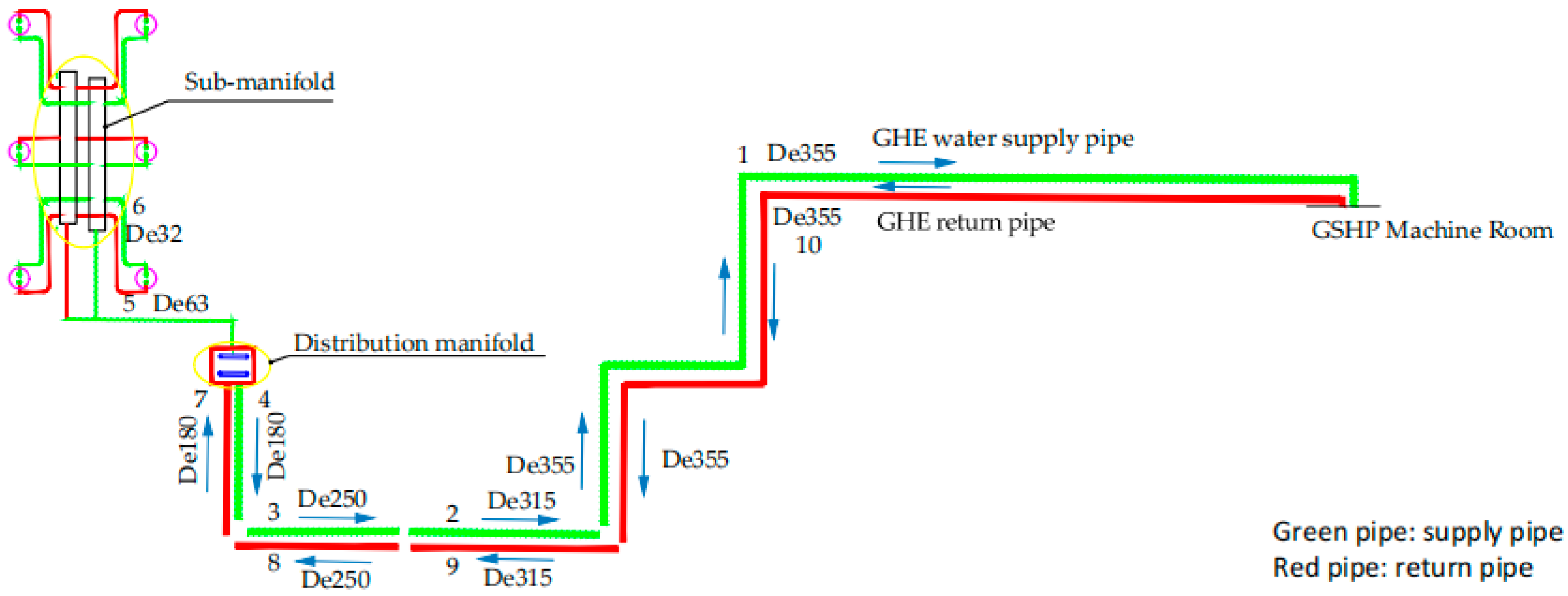

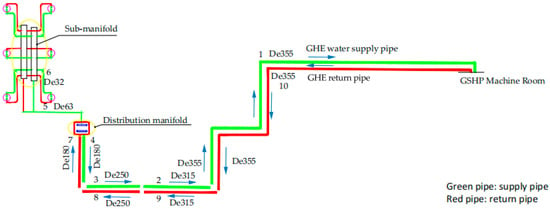

The schematic diagram of the least favorable loop in the system pipe network is shown in Figure 2. The ‘least favorable loop’ refers to the circuit path with the highest hydraulic resistance. It is typically furthest from the pump and receives the lowest flow rate. In contrast, the ‘most favorable loop’ is the path with the minimum resistance. It is usually closest to the source and tends to have excess flow. The depicted least favorable loop employs a single U-shaped pipe with a diameter of De32 and a borehole depth of 120 m. In the diagram, Sections 1–5 and 7–10 represent horizontal pipe segments with diameters of De355, De315, De250, De180, and De63, respectively. The corresponding flow rates and lengths for these segments are 334 m3/h and 88 m, 267 m3/h and 20 m, 133.6 m3/h and 49 m, 66.8 m3/h and 11 m, and 6.6 m3/h and 66 m, respectively. Other parameters are listed in Table 1.

Figure 2.

The most critical loop diagram.

Table 1.

Frictional head loss of outdoor buried pipes.

3. Methodology

3.1. Pipe Network Model Simplification

Given that the small pipe clusters connect directly to the distribution manifold, their representation poses significant challenges when constructing pipe network diagrams, necessitating simplification. Within the pipe network system, the circulating fluid flows from the distributor into the bundle of small pipe clusters and then returns to the collector. Since the collector and distributor are co-located, it can be determined that the bundle of small pipe clusters constitutes a non-identical circuits configuration. Horizontal pipes with larger diameters and shorter lengths are used to connect small pipe clusters, aiming to reduce the impact of horizontal pipe impedance on flow distribution between these clusters. Under the condition of ensuring constant impedance, this study employs the parallel impedance method to simplify the small pipe clusters bundle into a single branch [33]. The piping connecting the manifold to the group of small pipe clusters constitutes the main trunk line relative to the manifold circuit. The main trunk line functions as a common series resistance for the entire network. While it determines the total system pressure drop, it does not influence the relative flow distribution among downstream branches.

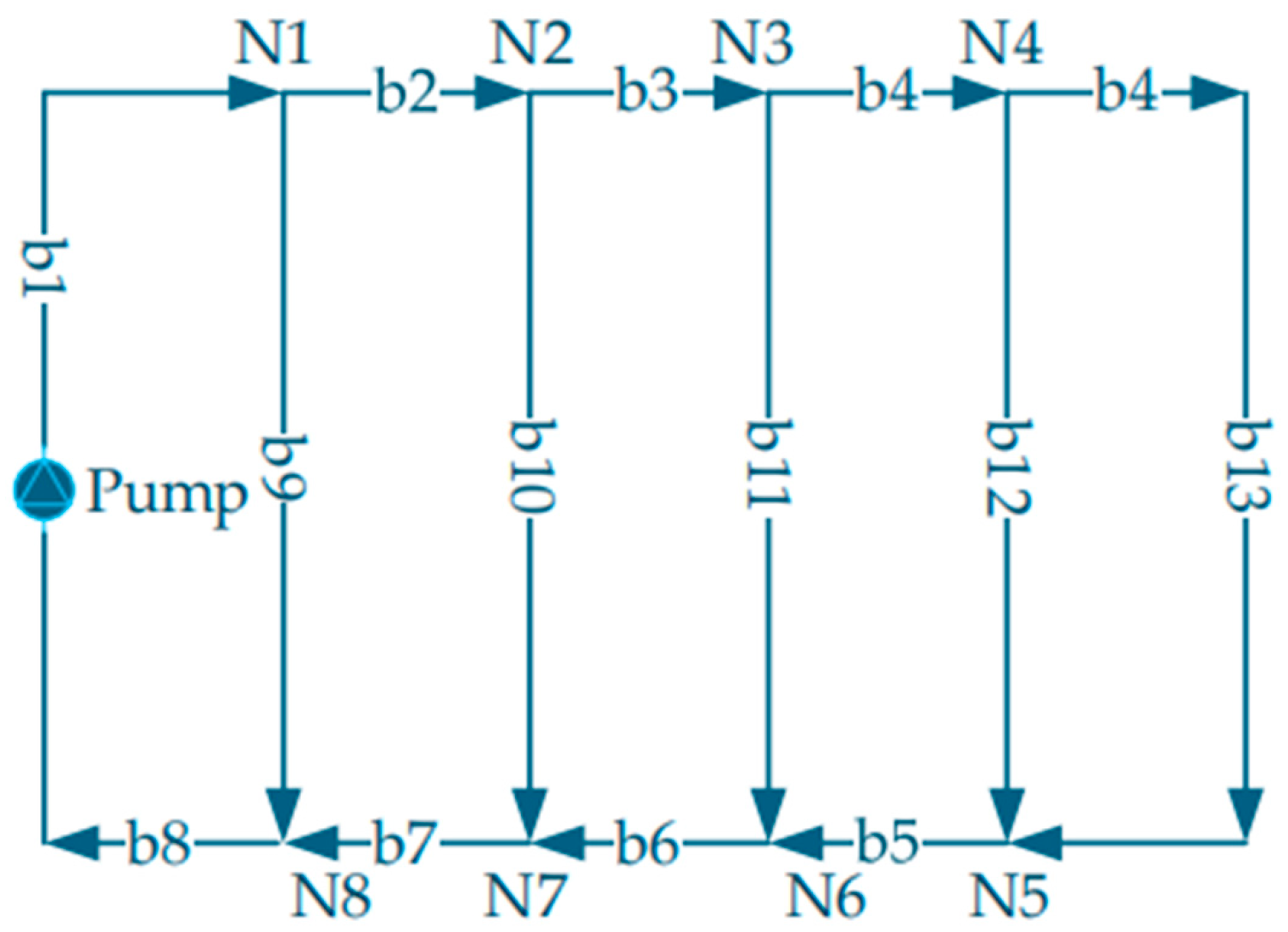

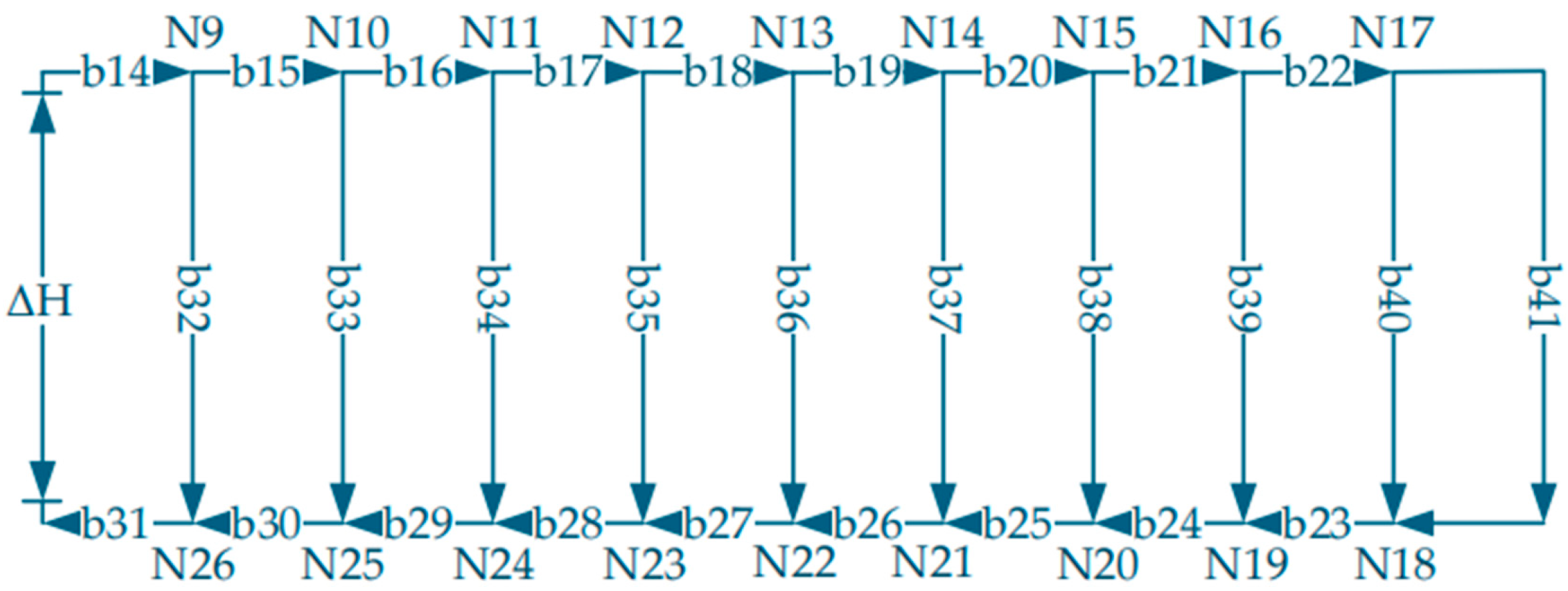

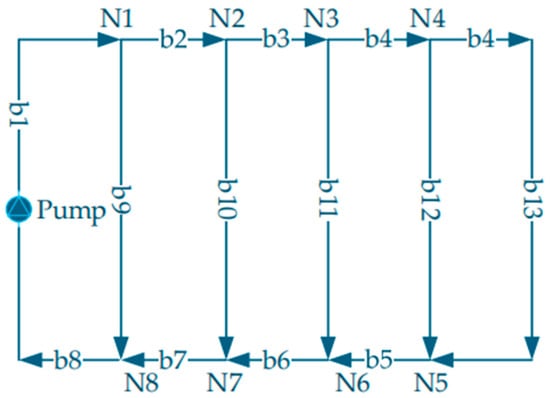

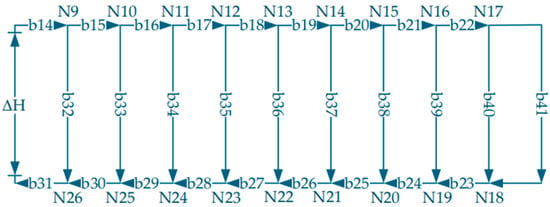

Based on this approach, the parallel impedance method is employed to perform the simplification. Each manifold circuit is simplified into an equivalent branch to calculate the flow rate distribution. The simplified configuration of the main pipe is shown in Figure 3. In this figure, segments b1–b8 represent the main trunk lines of the overall circulation loop, while b9–b13 correspond to the five manifold circulation loops. These five manifold loops share identical configurations, with nodes N1–N8 denoting the branch points. Figure 4 shows the detailed pipe schematic for the manifold circulation loop labeled b9 in Figure 3. Here, segments b14–b31 represent the main pipes connected to the branches formed by the small pipe groups, b32–b41 denote the ten branches themselves, and N9–N26 indicate the branch nodes.

Figure 3.

Pipe network schematic diagram.

Figure 4.

Detailed schematic diagram of the sub-network represented by branch b9.

3.2. Hydraulic Model Development and Solution

The flow distribution among individual boreholes in a GHE network can be analyzed using a hydraulic pipe network model. This model, grounded in graph theory, is governed by Kirchhoff’s laws, the hydraulic characteristics of the pipe network components, and the principle of energy conservation. It is represented by a system of mathematical equations and a pipe network topology diagram [34]. The governing equations of the hydraulic pipe network model are formulated as follows:

where A denotes the correlation matrix A = (aij); Bf represents the basic loop matrix Bf = (bkj); ΔH is the column vector of pressure drops across system pipe sections ΔH = (Δhi)T, mH2O; S is the diagonal matrix composed of system pipe section impedances, s2/m5; |G| is the diagonal matrix formed by the absolute values of branch flow rates across pipe sections, m3/s; and DH is the pump head, mH2O.

The hydraulic impedance Si for each pipe section is determined based on its frictional head loss Δhi (converted from pressure drop Pi) and mass flow rate Gi, defined as

This impedance serves as a constant characteristic parameter for the pipe section in the hydraulic network model.

where Δhi denotes the pressure drop of the i-th branch, mH2O.

In the hydraulic analysis of a pipe network, the topological structure is assumed to be fixed. Consequently, the incidence matrix A and the fundamental loop matrix Bf are known a priori. The nodal flow rates and pump operating parameters are given as input conditions to calculate the pipe resistances. The pipe network model contains 2B unknowns and 2B independent equations. Since the number of equations equals the number of unknowns, a unique solution can be obtained.

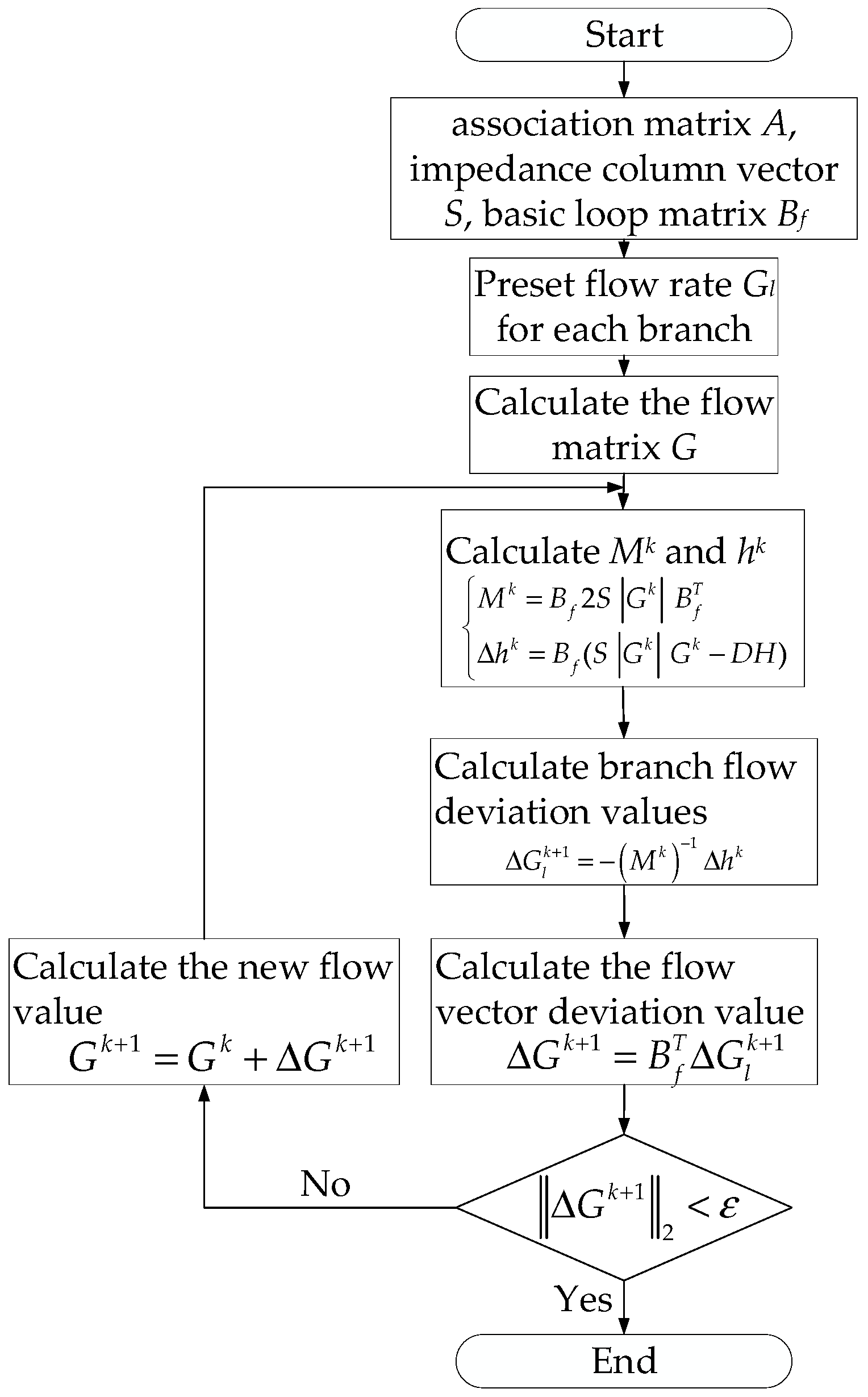

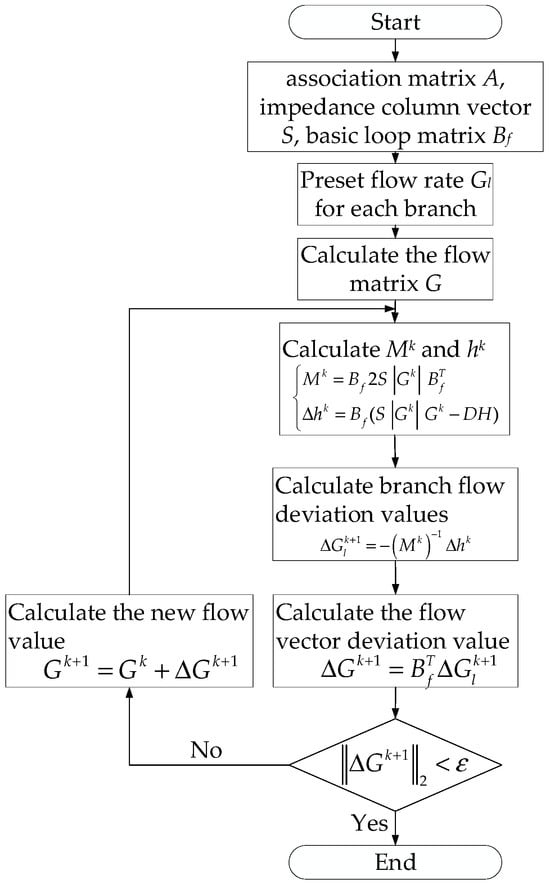

The specific procedure for solving the pipe network is as follows:

- For a given project, draw the pipe network diagram based on the actual borehole distribution. From this diagram, establish the incidence matrix A and the fundamental loop matrix Bf, and calculate the impedance matrix S.

- Specify the initial branch flow rates Gl0 and the iteration tolerance ε (set to 10−16 in this study).

- Calculate the pipe network flow rates based on the branch flow rates, obtain parameter Gtk, then derive Gk; subsequently, determine Mk and Δhk, and finally obtain ΔGlk;

- Derive ΔGlk from Gk+1.

- Evaluate parameter ||ΔGk+1||2 < ε. If the specified condition is satisfied, terminate the iteration and output the result G* = Gk+1; otherwise, update k = k + 1 and repeat Step (3).

This solution process employs the fundamental loop method based on graph theory. In the flowchart (Figure 5), the adjacency matrix A is decomposed into the branch matrix At and the link matrix Al. Accordingly, the flow vector G is divided into branch flows Gt and link branch flows Gl. During iteration (step k), Mk denotes the coefficient matrix obtained by linearizing the loop energy equation, and ∆hk represents the residual pressure drop vector of the loop. The term ∆Gkl represents the adjusted value of link traffic in the current iteration.

Figure 5.

Flowchart of the basic loop iterative calculation method [35].

3.3. Heat Exchange Model

Single U-tube heat exchangers are extensively employed in shallow GSHP systems due to their practical design and reliable performance. In this study, a single U-tube heat exchange model [32] is adopted for the analysis of underground heat exchange processes.

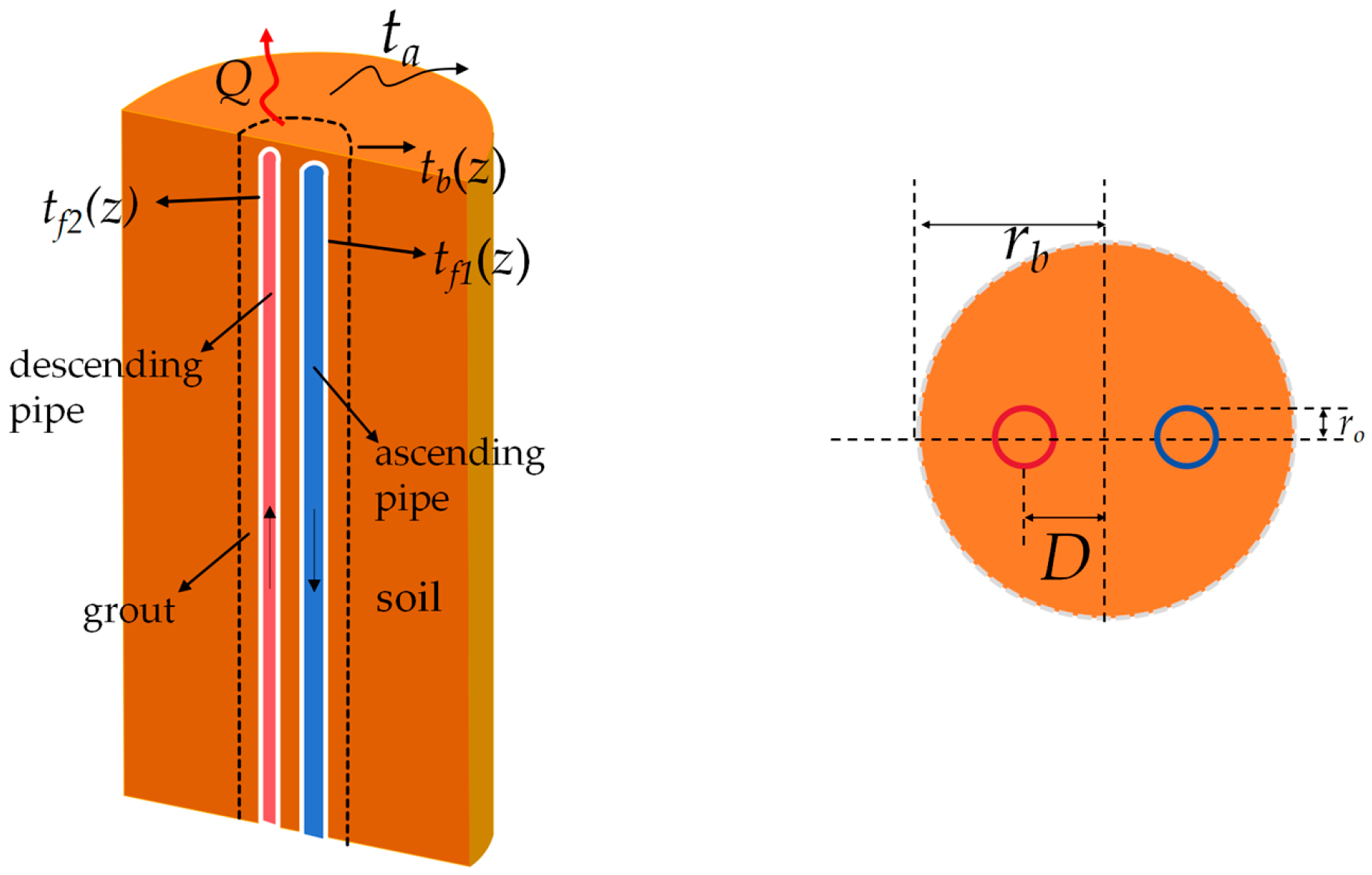

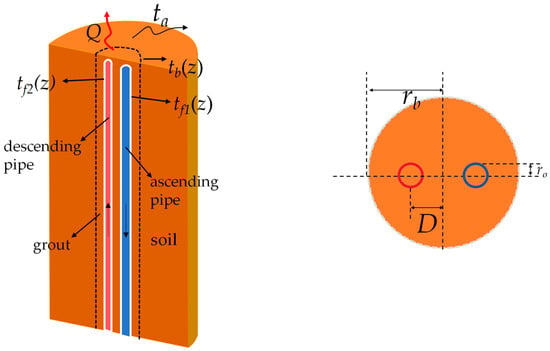

The GHEs are installed vertically inside boreholes, with the annular space between the tube and the borehole wall filled with grout. During heating mode, the circulating fluid inside the tubes absorbs heat from the surrounding soil; during cooling mode, it rejects heat into the ground.

A schematic of the single U-tube configuration is presented in Figure 6. The blue pipe represents the descending pipe, transporting fluid into the underground circuit, while the red pipe denotes the ascending pipe, returning fluid to the surface. The following key parameters are indicated: tb denotes the borehole wall temperature, tf1 and tf2 represent the temperatures of the circulating fluid in the ascending pipe and descending pipe, respectively, ta is the annual average ground temperature, and D denotes half the center-to-center distance between the two legs of the U-tube.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of U-tube arrangement in borehole.

In this paper, the following assumptions are applied to the heat exchange model.

- The surface temperature is assumed to be the annual average temperature and remains constant.

- Geothermal heat exchange is treated as a simple heat conduction problem, disregarding the influence of groundwater seepage.

- The geotechnical boundary is set sufficiently far from the borehole, such that its temperature distribution remains unaffected.

Heat exchange within GHEs involves complex interactions between the circulating fluid and the ground. Therefore, the analysis is divided into two distinct zones: the internal and external borehole regions [32].

3.3.1. Borehole Outer Model

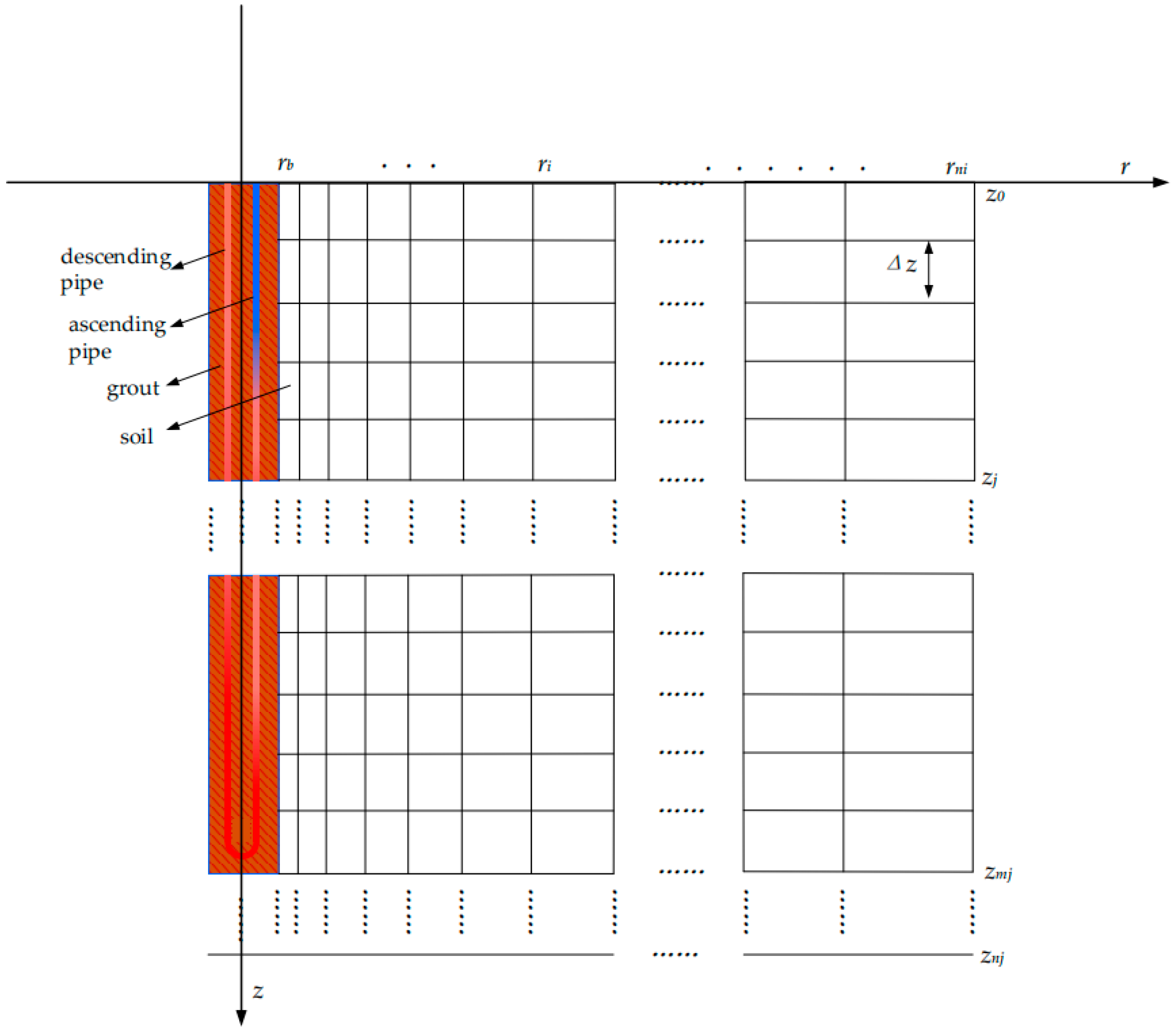

Due to the significant radial temperature gradient near the borehole and the negligible heat flux in the far field, variable step sizes can be applied in the radial direction. A coordinate transformation method is employed to define a transformed coordinate system.

The heat exchange in the borehole is described by the heat conduction differential equation. This equation is transformed into the γ-coordinate form and simplified to yield:

3.3.2. Borehole Internal Model:

Heat exchange within boreholes involves both conduction and convection processes, thus described using the energy conservation equation. Since borehole heat exchange is a transient process, the equation is simplified using a quasi-three-dimensional transient model to yield

In the equations, C1 and C2 represent the specific heat capacity per unit length of the downpipe and riser, respectively, including the circulating fluid within the pipes, U-tubes, and grout, J/(m·K); tf1 denotes the temperature of the circulating fluid in the downpipe, °C; tb denotes the borehole wall temperature, °C; tf2 denotes the temperature of the riser, °C; gf denotes the flow rate of the circulating fluid in the GHE, kg/s; and cf denotes the specific heat capacity of the circulating fluid in the GHE, J/(kg·K).

In the equation, rb denotes the borehole radius, m; r0 denotes the outer diameter of the U-tube, m; ri denotes the inner diameter of the U-tube, m; ρg denotes the density of the grout, kg/m3; ρ1 denotes the density of the U-tube, kg/m3; ρf denotes the density of the circulating fluid, kg/m3; cg denotes the specific heat capacity of the grout, J/(kg·K); and c1 denotes the specific heat capacity of the U-tube, J/(kg·K).

where R1 denotes the thermal resistance between the circulating fluid inside the pipe and the borehole wall, m·K/W; R2 denotes the thermal resistance between the circulating fluid in the ascending pipe and the descending pipe, m·K/W; λb denotes the thermal conductivity of the grout, W/(m·K); λs denotes the thermal conductivity of the surrounding rock and soil, W/(m·K); h represents the convective heat exchange coefficient between the fluid and the inner wall of the U-tube, W/(m2·K); and D indicates half the distance between the centers of the descending pipe and the ascending pipe.

3.3.3. Initial and Boundary Conditions

The model assumes a uniform initial temperature distribution at any given depth, with temperature varying with depth. Owing to the assumption of a uniform terrestrial heat flow, different geological layers exhibit distinct temperature gradients. Consequently, the initial ground temperature at any depth can be expressed as:

where λsj and λsnj represent the thermal conductivities of the geotechnical material at nodes zj and zj+1, respectively, W/(m·K), and zj, zj−1, and znj−1 denote the depths of these respective nodes.

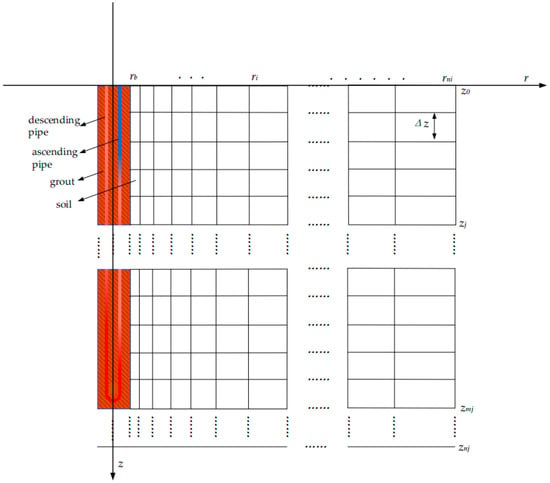

The borehole node division is shown in Figure 7. In the figure, rb denotes the borehole wall, ri denotes the radial node, rni denotes the node at the radial boundary, z0 denotes the initial axial boundary node, zj denotes the axial node, zmj denotes the node at the bottom of the borehole, znj denotes the axial boundary node, and Δz denotes the axial node spacing.

Figure 7.

Node partitioning diagram.

Before system operation, the circulating fluid temperature was assumed to be in equilibrium with the undisturbed ground temperature at the corresponding depth.

To compare the heat exchange rates of the U-tube borehole heat exchanger under various flow conditions, the instantaneous heat exchange rate is computed under a constant inlet fluid temperature. A boundary condition of the Dirichlet condition is applied at the inlet of the circulating fluid, with a fixed temperature of tf = 5 °C at z = 0. Given that the ascending and descending legs are connected at the bottom of the borehole, the fluid temperatures at this specific junction are assumed to be equal.

A convective boundary condition is applied at the surface. The bottom of the borehole is considered thermally insulated. The vertical boundary at the far end of the borehole and the lateral boundary are considered thermally insulated.

where ha denotes the surface convective heat exchange coefficient, W/(m2·K); rni represents the lateral boundary, m; zmi indicates the depth of the borehole bottom, m; and znj denotes the vertical boundary, m.

The borehole model is discretized using the finite difference method to establish a system of nodal equations, which is subsequently solved by the Thomas algorithm. To ensure the accuracy of the numerical solution, an iterative calculation process is employed, with the convergence tolerance for the temperature field set to 5 × 10−5.

4. Simulation Results and Analysis

To comprehensively investigate the coupling characteristics between hydraulic imbalance and heat exchange performance, a parametric simulation study was designed based on the reference project. The simulation matrix comprises thirty distinct operating scenarios, formed by the combination of five borehole cluster scales (300, 600, 900, 1200, and 1500 boreholes) and six varying borehole depths (60, 80, 100, 120, 140, and 160 m).

4.1. Hydraulic Analysis and Results

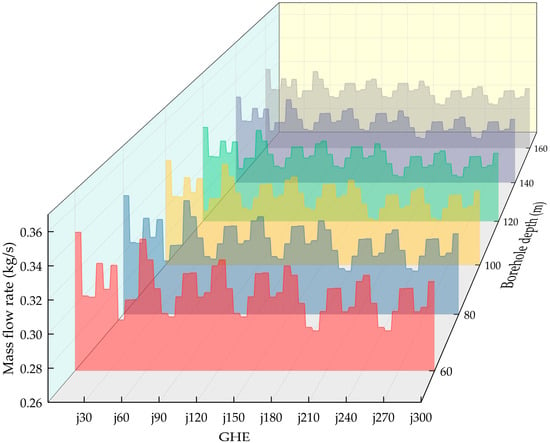

To investigate typical hydraulic imbalance conditions, the flow distribution was analyzed based on the simulation scenarios defined above. The results for the 300-borehole system across varying depths are presented in Table 2 and Figure 8.

Table 2.

Flow rate distribution across the 300 boreholes.

Figure 8.

Flow distribution across the 300 boreholes.

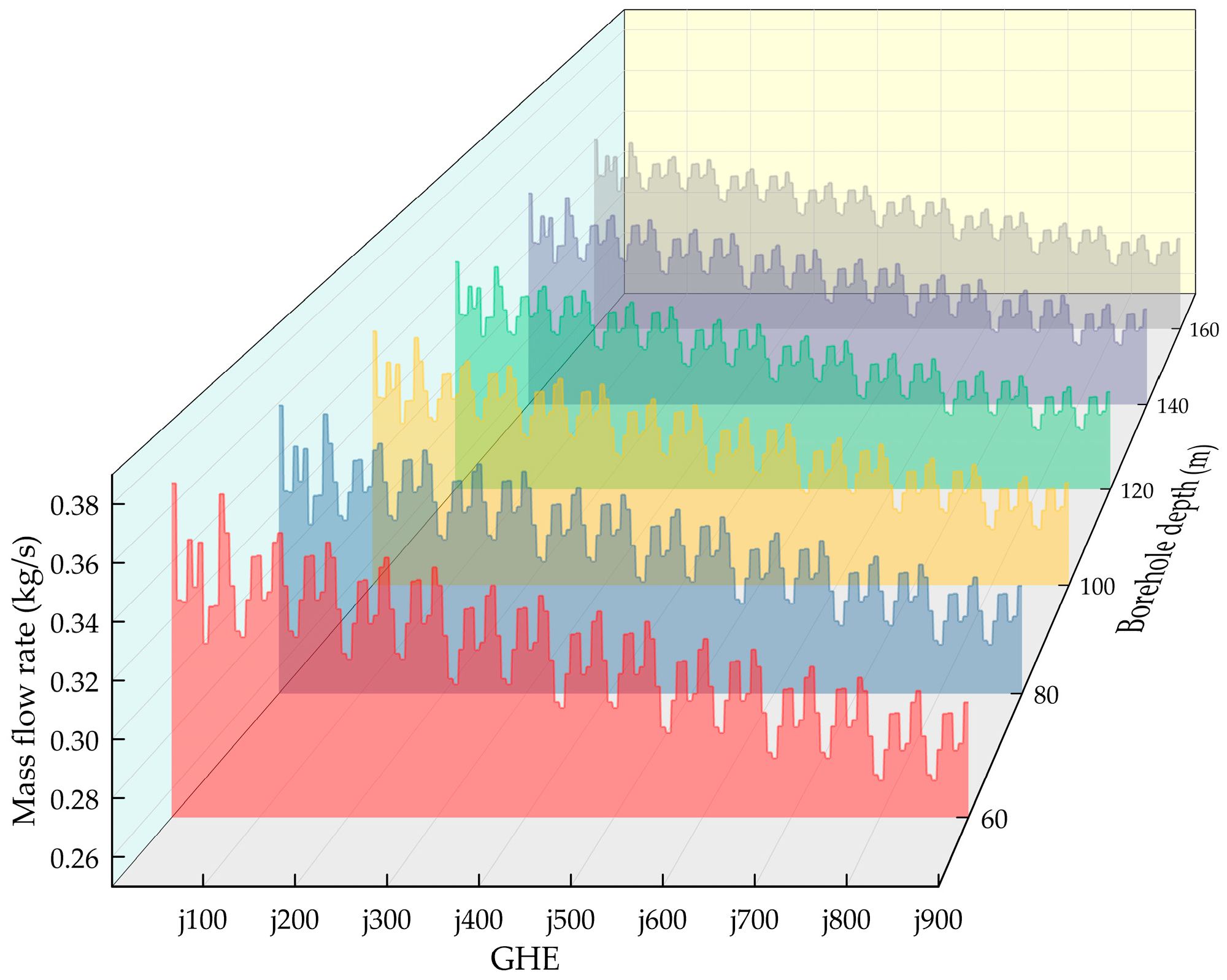

The flow distribution results for the 300-borehole system at depths of 60 m, 80 m, 100 m, 120 m, 140 m, and 160 m are shown in Table 2 and Figure 8. The maximum flow rate occurs at borehole j1, while the minimum rate is observed at borehole j260 across all depths. Analysis of the results shows that the most extreme flow rates for a single borehole were both found at the 60 m depth, with values of 0.3443 kg/s (maximum) and 0.2844 kg/s (minimum), respectively. The flow imbalance rate was highest (0.21) at the 60 m depth, whereas the minimum rate (0.1) occurred at the 160 m depth.

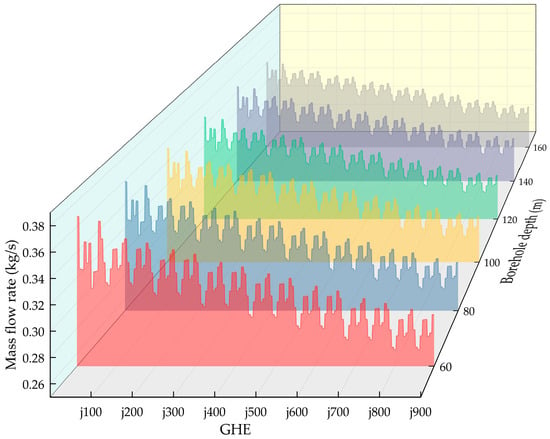

With the number of boreholes set at 900, the borehole depth was varied, being set to 60, 80, 100, 120, 140, and 160 m. Simulation results are presented in Table 3 and Figure 9. For this borehole count, boreholes j1 and j860 exhibited the maximum and minimum flow rates, respectively. Both the maximum flow rate (0.3679 kg/s) and the minimum flow rate (0.2631 kg/s) occurred at a borehole depth of 60 m. The maximum flow imbalance rate also occurred at the 60 m depth, with a value of 0.4, while the minimum rate (0.22) was observed at the 160 m depth. The flow imbalance rate was generally higher than in the 300-borehole scenario, and the downward trend in flow rate shown in Figure 9 is much more pronounced than that in Figure 8.

Table 3.

Flow rate distribution across the 900 boreholes.

Figure 9.

Flow distribution across the 900 boreholes.

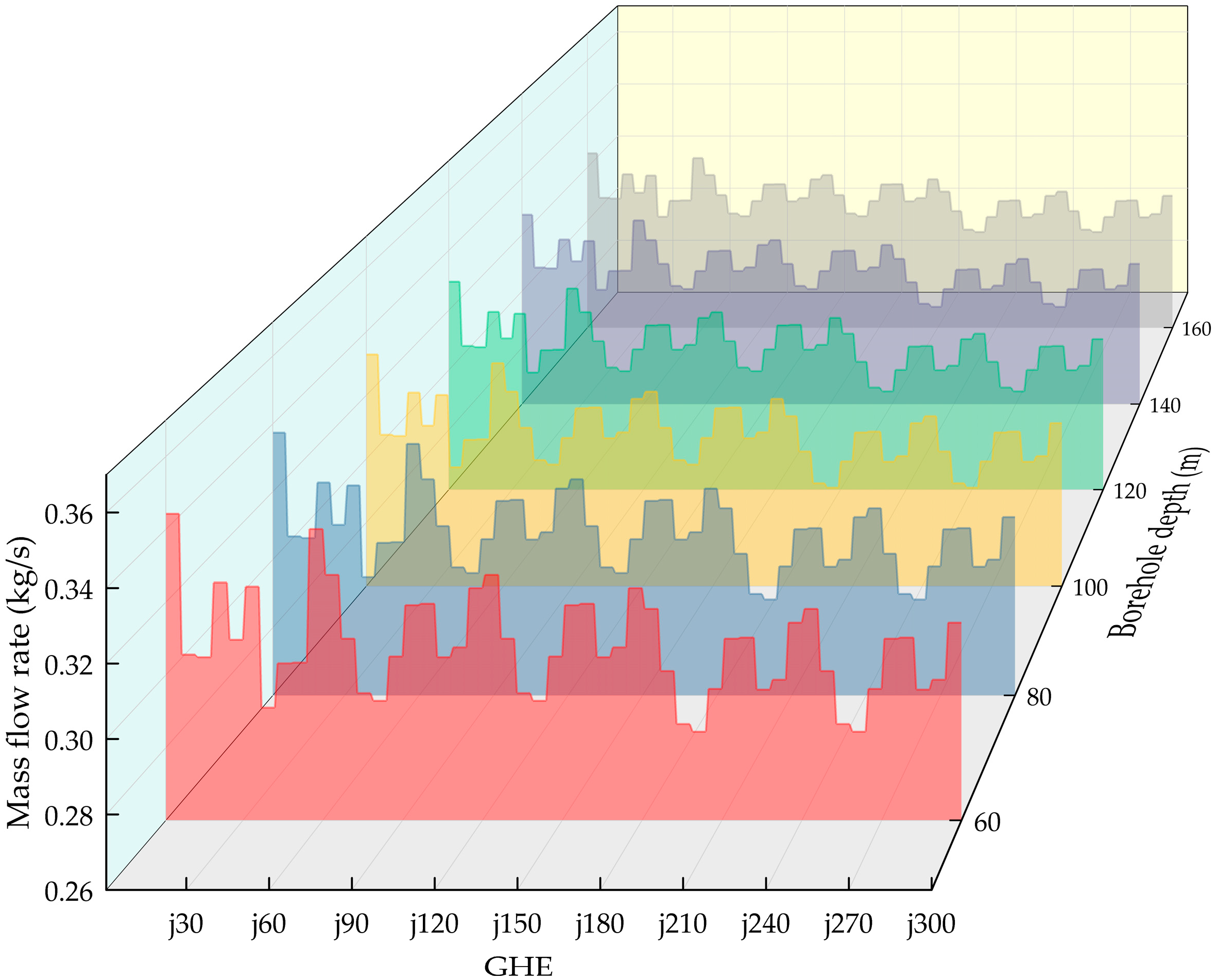

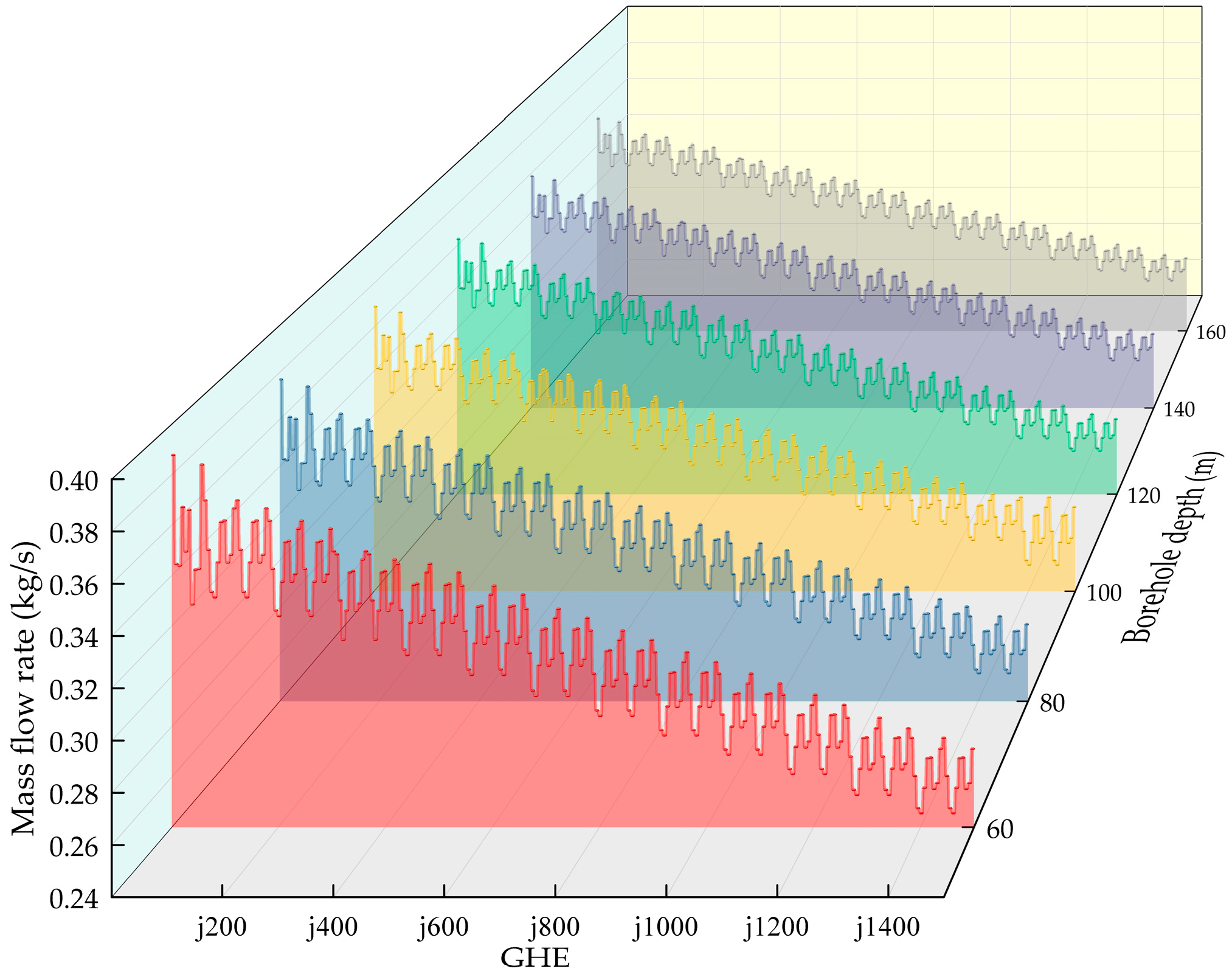

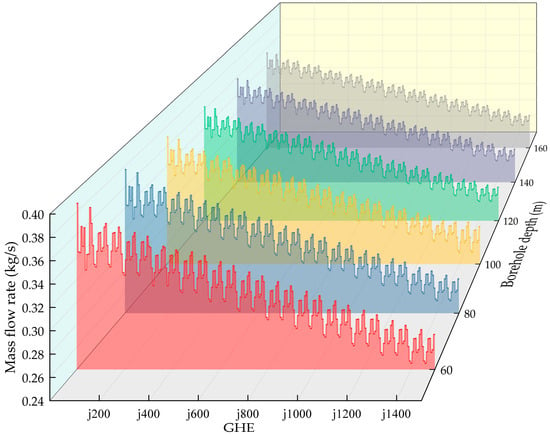

Under the condition of setting the number of boreholes to 1500, the borehole depth was set to 60, 80, 100, 120, 140, and 160 m. The specific simulation results are shown in Table 4 and Figure 10. Under these conditions, boreholes j1 and j1460 exhibited the maximum and minimum flow rates, respectively. The simulations showed a maximum flow rate of 0.3878 kg/s and a minimum flow rate of 0.2456 kg/s. The maximum flow imbalance rate reached 0.58, while the minimum was 0.33. The flow imbalance was more pronounced than in the scenario with 900 boreholes.

Table 4.

Flow rate distribution across the 1500 boreholes.

Figure 10.

Flow distribution across the 1500 boreholes.

The most pronounced change in flow imbalance rate occurs at the 60 m borehole depth. As the number of boreholes increases from 300 to 1500, the flow imbalance rate rises by 36.9%. When the number of boreholes remains constant, the difference in the flow imbalance rate between the 60 m and 160 m configurations is 11.1% for a system with 300 boreholes. This difference expands to 25.3% when the number of boreholes reaches 1500.

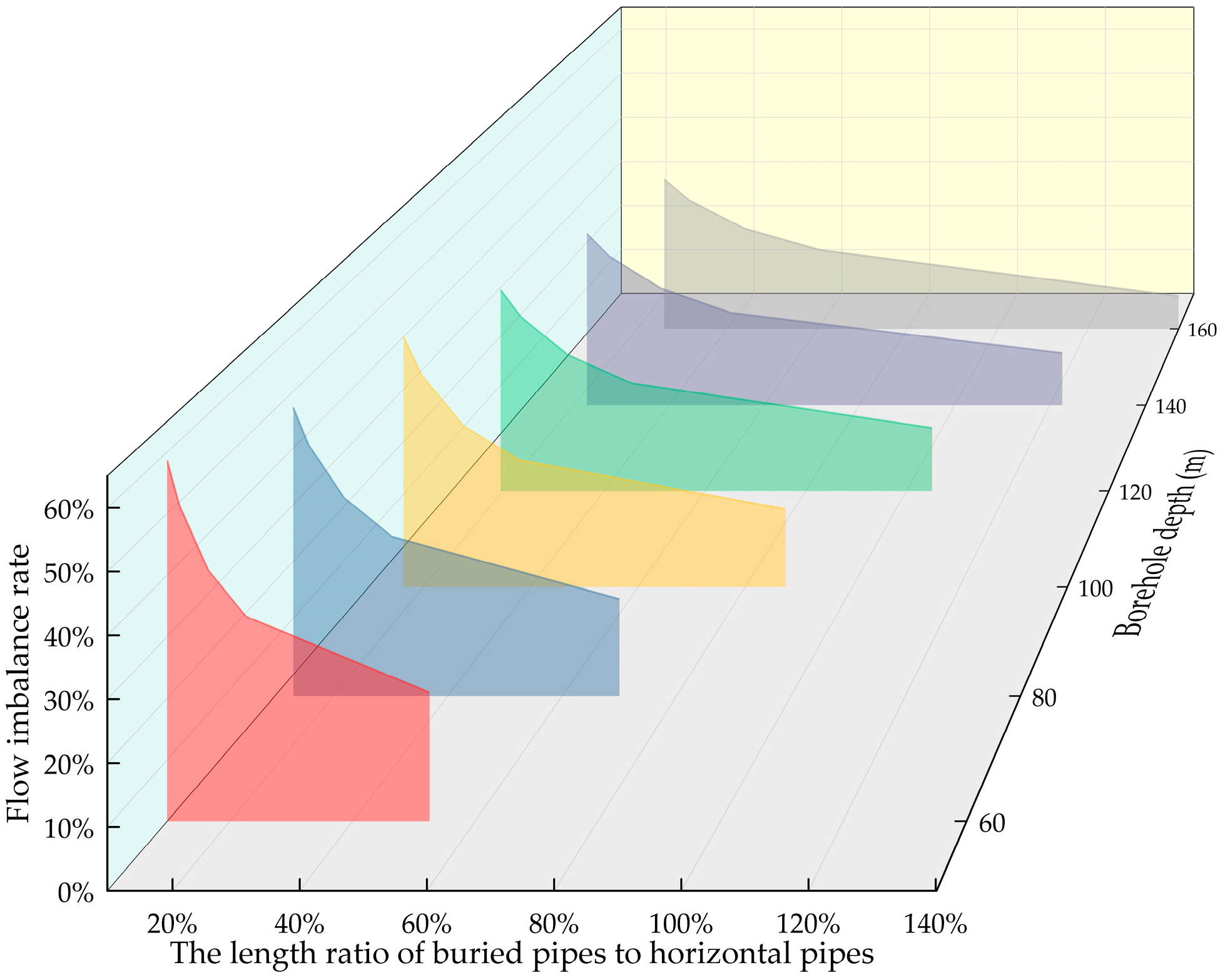

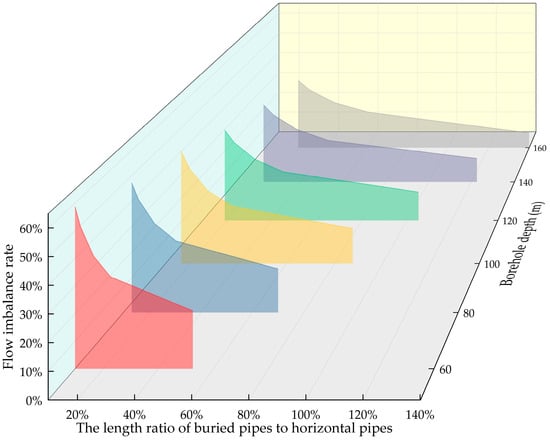

Simulation results indicate that the flow imbalance rate increases with either a greater number of boreholes or a shallower borehole depth. Variations in borehole quantity and depth alter the ratio of vertical to horizontal pipe lengths (hereinafter referred to as the ‘length ratio’). This study established a formula describing the relationship between the flow imbalance rate and this length ratio, and a corresponding trend diagram is plotted in Figure 11. The main trunk line has little influence on the overall flow distribution. Therefore, the horizontal pipe length is defined as the distance from the start of the trunk lines at the first manifold to the endpoints of the horizontal pipes in the least favorable loop.

Figure 11.

Relationship between flow imbalance rate and the ratio of GHE to horizontal pipe length.

Simulation results indicate a significant negative correlation between the system flow imbalance rate and the length ratio. Specifically, for borehole depths of 60 m and 160 m, increasing the borehole count from 300 to 1500 significantly increased the total horizontal pipe length. Consequently, the length ratio decreased from 0.53 to 0.1 and from 1.4 to 0.26, respectively. Concurrently, the flow imbalance rate increased from 21% to 57.9% and from 9.9% to 32%, respectively. At varying borehole depths (60–160 m), as the number of boreholes increases, the length ratio between vertical and horizontal pipes continues to rise, accompanied by a corresponding increase in flow imbalance rates. This demonstrates that increasing the length ratio effectively optimizes flow distribution uniformity. Consequently, this finding provides crucial theoretical support for the hydraulic balancing design of GSHP systems. Based on simulation results, empirical formulas were developed to fit the length ratio and flow imbalance in GHEs for depths ranging from 60 to 160 m. The formula format is as follows:

In the formula, Lv/h denotes the ratio of the vertical GHE length to the horizontal pipe length; δf represents the flow imbalance rate. The parameters vary within the following ranges: a ∈ [0.0677, 0.1059], b ∈ [−1.0805, −0.7886], d ∈ [0.0192, 0.0921].

Table 5.

Numerical values for a, b, and d.

This study selected the case of 300 boreholes with depths of 90 m to validate the established formula. Simulation results showed a flow imbalance rate of 15.62% under this configuration. When the borehole depth is set to 90 m, the values of parameters a, b, and d are determined by linear interpolation using existing data from the table.

At this borehole depth, the length ratio is 0.79. Through linear interpolation, the specific values of a, b, and d are calculated as 0.0655, −0.9656, and 0.0741, respectively. Substituting the above parameters into the formula yields a flow imbalance rate of 15.63%. Comparing the simulation results with the formula-derived results, the discrepancy is less than 1%, which falls within the acceptable range for engineering applications.

Distinct from conventional hydraulic calculations that often assume uniform flow distribution or focus on optimizing single-pipe parameters [14,15], Formula (15) specifically characterizes the hydraulic behavior of large-scale clusters with non-identical circuits. In such extensive networks, the assumption of identical circuits may lead to underestimations of resistance variations. Thus, the derived formula offers an effective evaluation criterion for detecting potential flow instability in large-scale engineering applications where geometric irregularity is unavoidable.

The observed power-law relationship reflects the hydraulic resistance distribution. Zhang et al. [16] indicated that vertical GHEs account for the majority (e.g., 80%) of the total network resistance. Our results confirm this mechanism. As borehole depth increases, the length ratio rises. Consequently, the resistance of the vertical pipes becomes dominant. Since these vertical pipes are identical, their dominance reduces the impact of unequal horizontal pipe lengths. This naturally improves hydraulic balance. In contrast, shallow arrays have a low Lv/h ratio. In these cases, the resistance of horizontal manifolds becomes significant. Therefore, the strict layout optimization proposed in this study is essential for shallow, large-scale systems. Finally, it should be noted that Formula (15) applies to conventional buried pipe network systems with drilling depths ranging from 60 to 160 m.

4.2. Heat Exchange Simulation Results and Analysis

The specific parameters used in the heat exchange model calculations are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Heat exchange calculation parameters.

4.2.1. Effect of Different Borehole Quantities on Heat Exchange

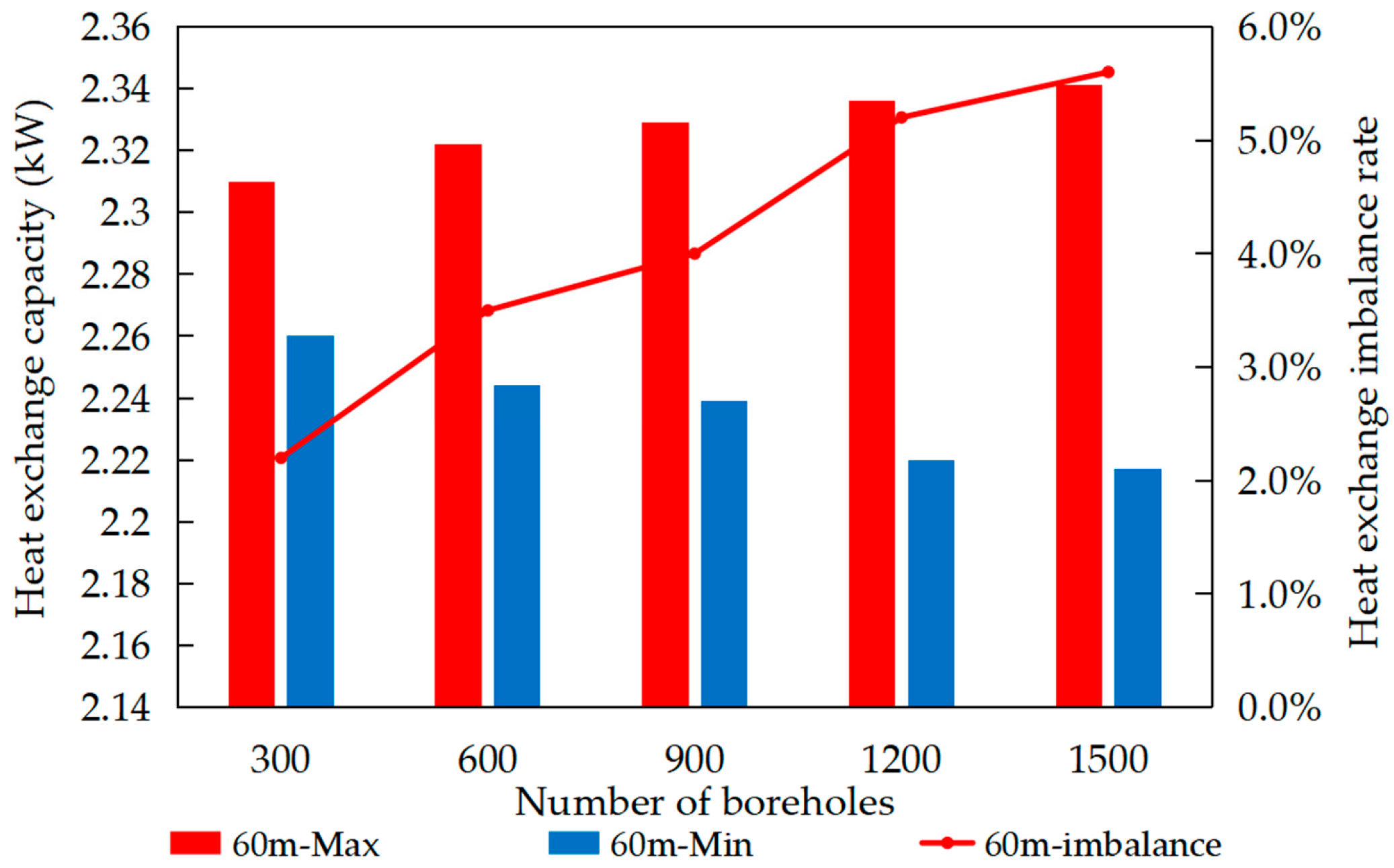

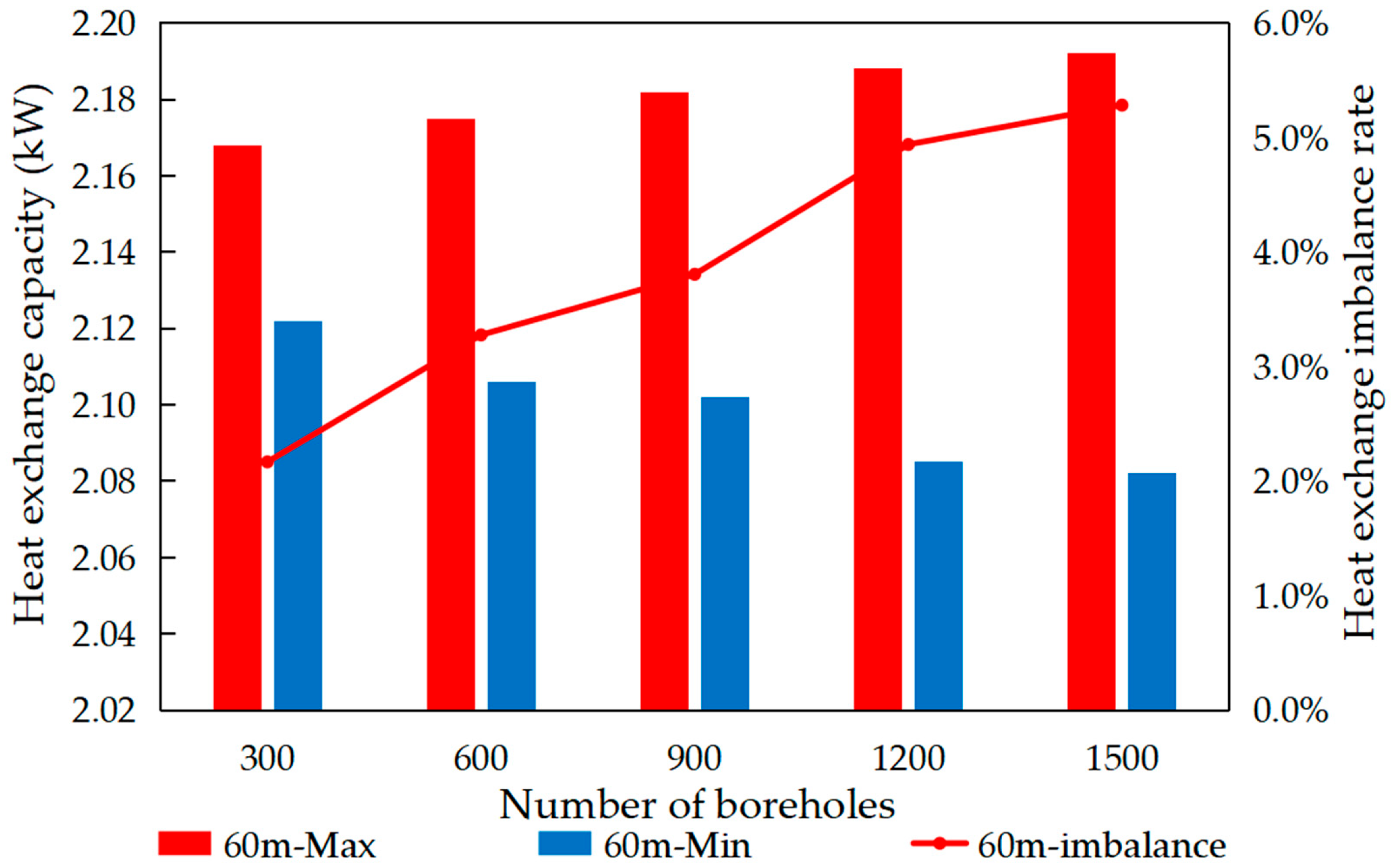

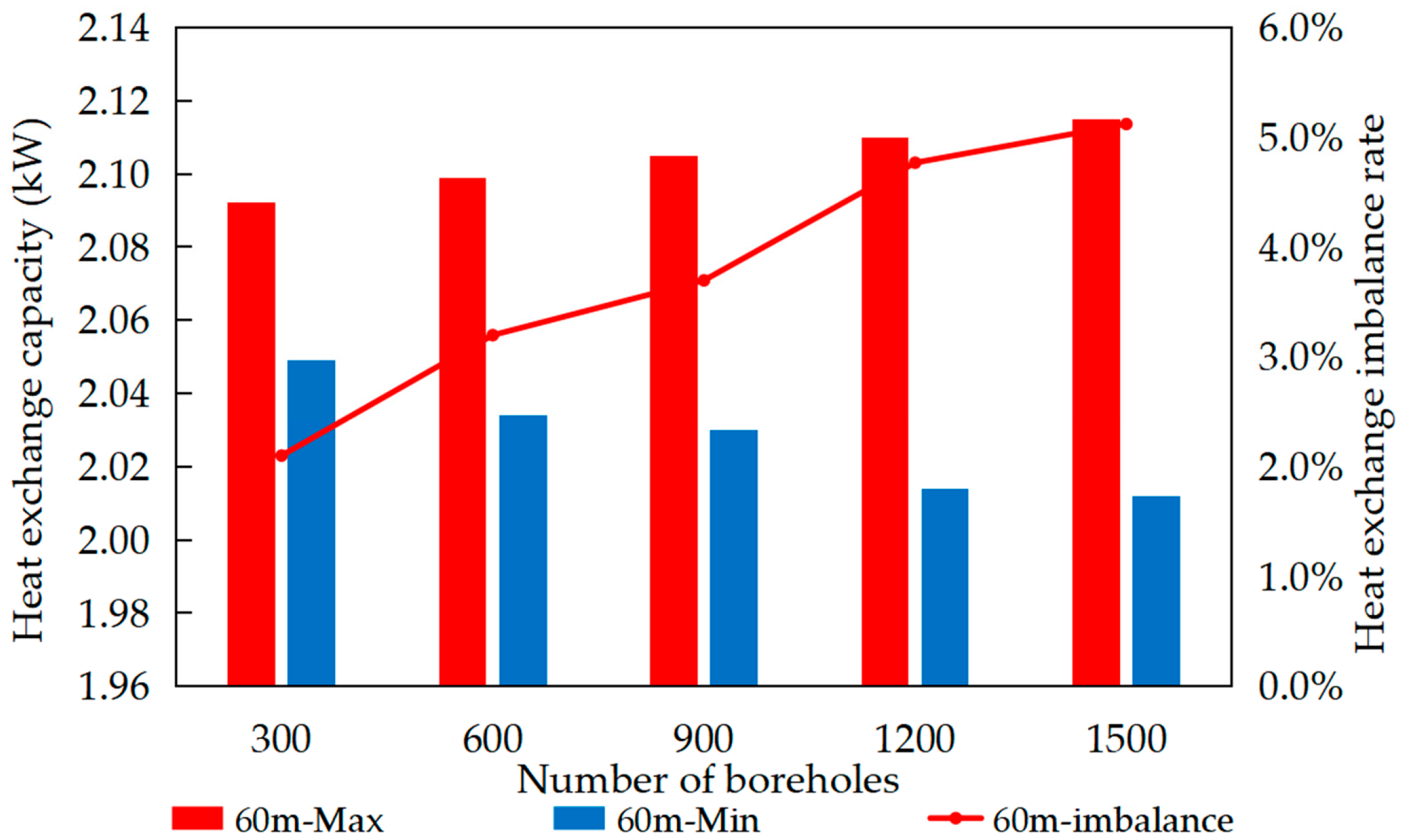

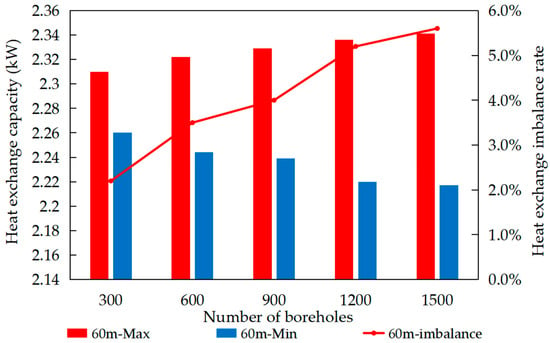

To investigate the impact of borehole quantity on heat exchange performance, simulations were conducted with a fixed borehole depth of 60 m. The simulations considered five borehole quantities (300, 600, 900, 1200, 1500) operating under a continuous mode for durations of 10, 20, and 30 days. The results are presented in Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14.

Figure 12.

Simulation results for 10 days of operation under five operating conditions.

Figure 13.

Simulation results for 20 days of operation under five operating conditions.

Figure 14.

Simulation results for 30 days of operation under five operating conditions.

As the number of boreholes increases, influenced by the flow imbalance, the heat exchange capacity of the most favorable loop decreases, while that of the least favorable loop increases. This results in a corresponding increase in the heat exchange imbalance rate. Specifically, after 10 days of system operation, when the number of boreholes increased from 300 to 1500, the heat exchange capacity of the most favorable loop decreased from 2.34 kW to 2.31 kW. Conversely, the heat exchange capacity of the least favorable loop increased from 2.26 kW to 2.22 kW. Consequently, the heat exchange imbalance rate increased from 2.3% to 5.6%.

After 10 days of operation compared to 20 days, the heat exchange capacity of the GHEs in both the most favorable and the least favorable loops changed by 6%. Similarly, when the operating duration increased from 20 days to 30 days, the heat exchange capacity of the GHEs in both the most favorable and the least favorable loops decreased by 3%. As the system operating time extends, the overall heat exchange capacity gradually stabilizes.

When the number of boreholes is set to 300, the difference in heat exchange capacity between the most favorable and least favorable loops is 0.05 kW. When the number increases to 1500 boreholes, the difference rises to approximately 0.12 kW. Thus, the impact of increasing borehole count on heat exchange capacity is relatively limited. Given the complexity of heat exchange in GHEs, the process is typically analyzed in two parts: heat exchange inside and outside the boreholes. During heat exchange, the key physical parameter affecting heat exchange capacity is thermal resistance. Research indicates that the heat exchange resistance outside the borehole constitutes the major portion, while the resistance inside the borehole accounts for a smaller proportion. Changes in the circulation fluid flow rate within the borehole directly affect the internal heat exchange resistance, thereby influencing the heat exchange capacity [36,37]. In non-identical circuits large-scale GSHP systems, increasing the number of boreholes significantly impacts the system’s flow imbalance rate but has a relatively minor effect on heat exchange performance.

4.2.2. Effect of Hydraulic Imbalance on Heat Exchange at Different Borehole Depths

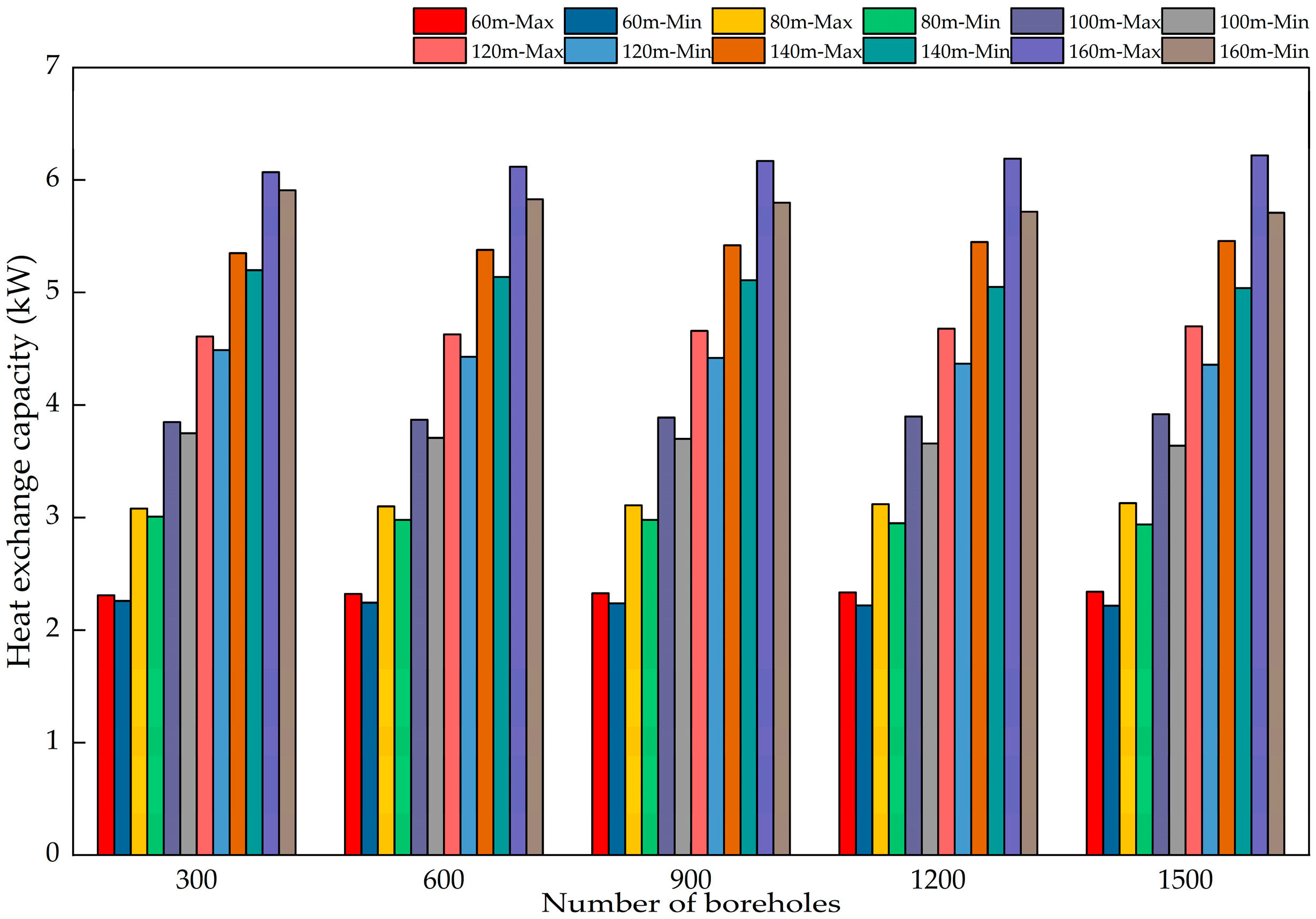

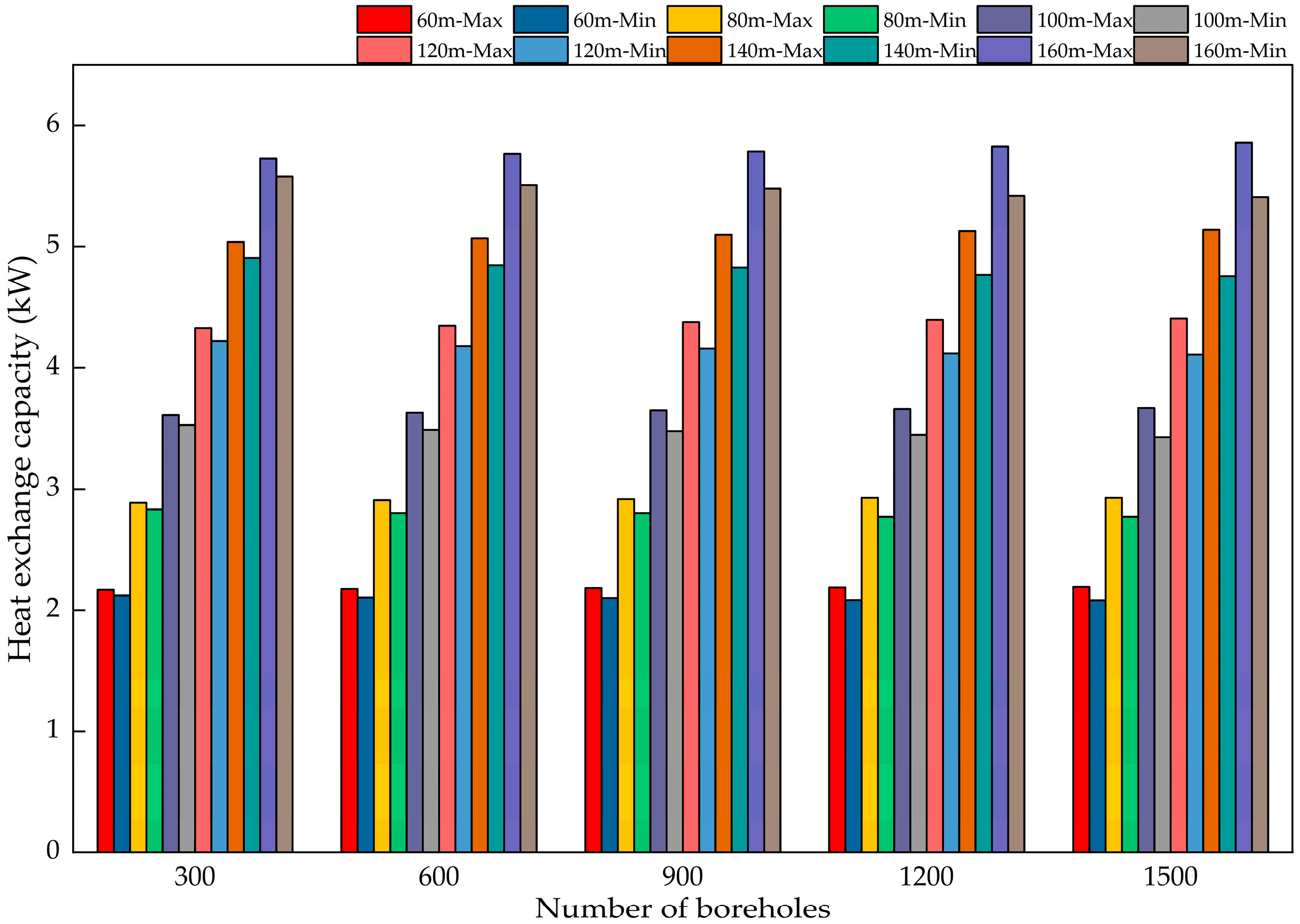

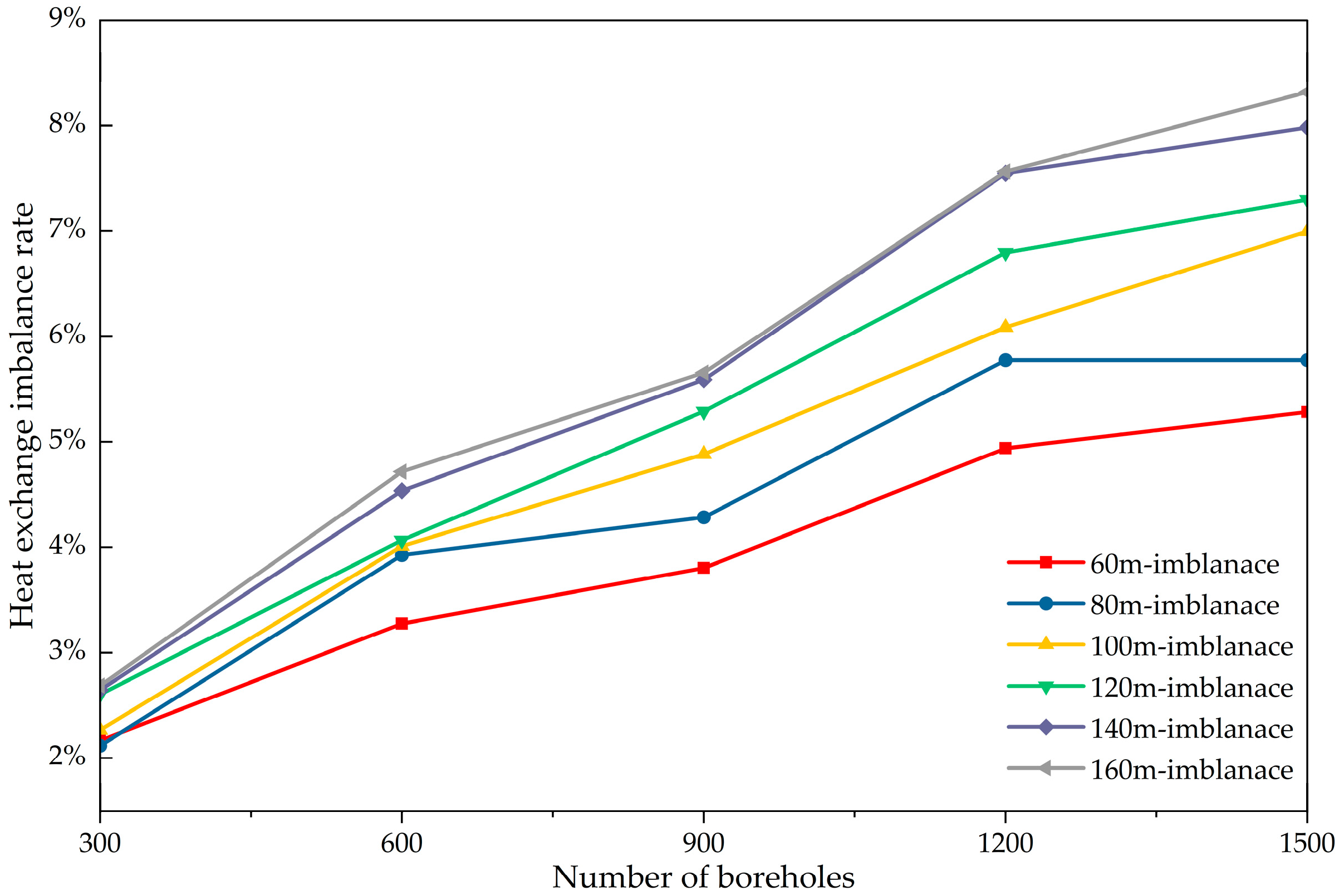

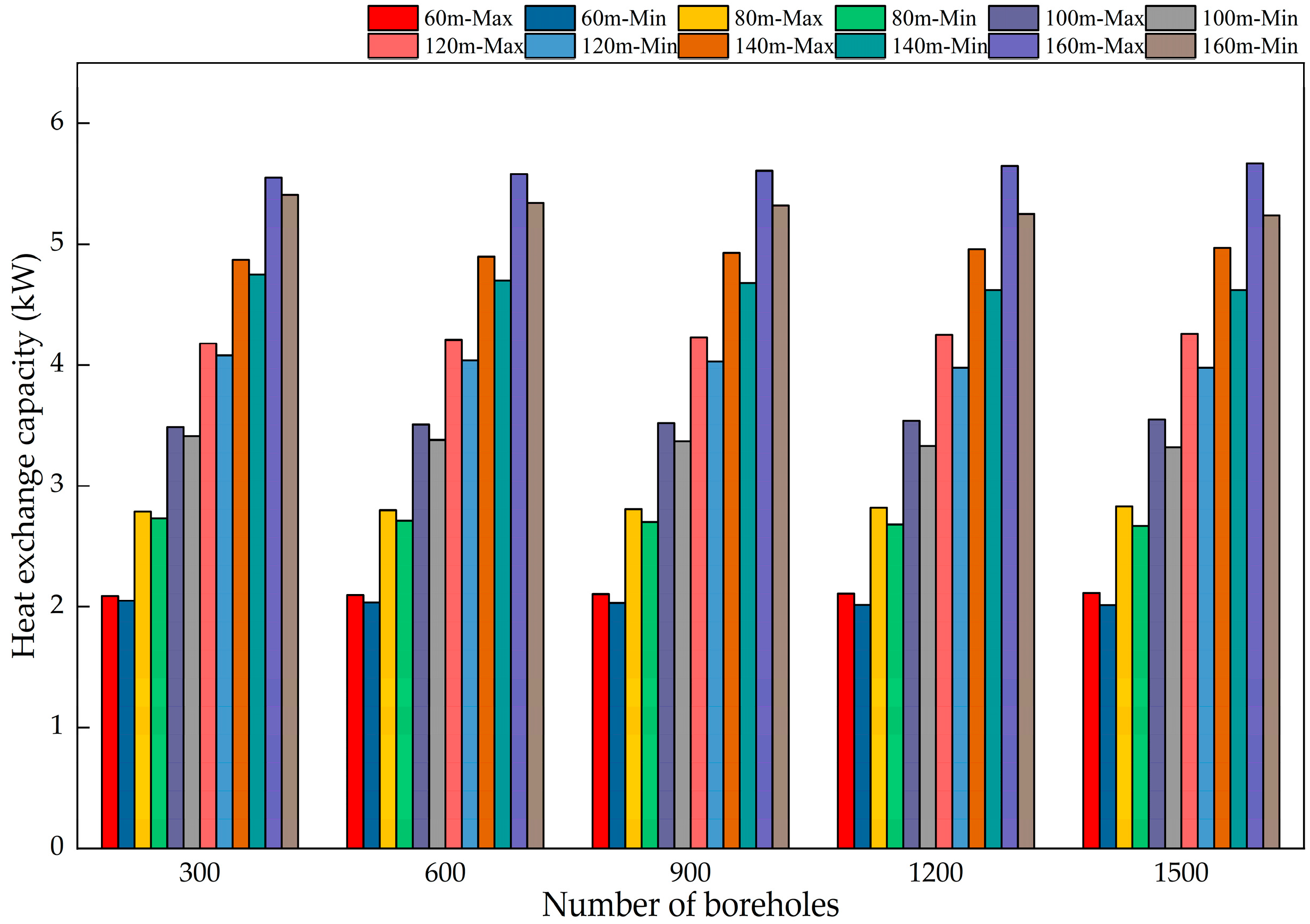

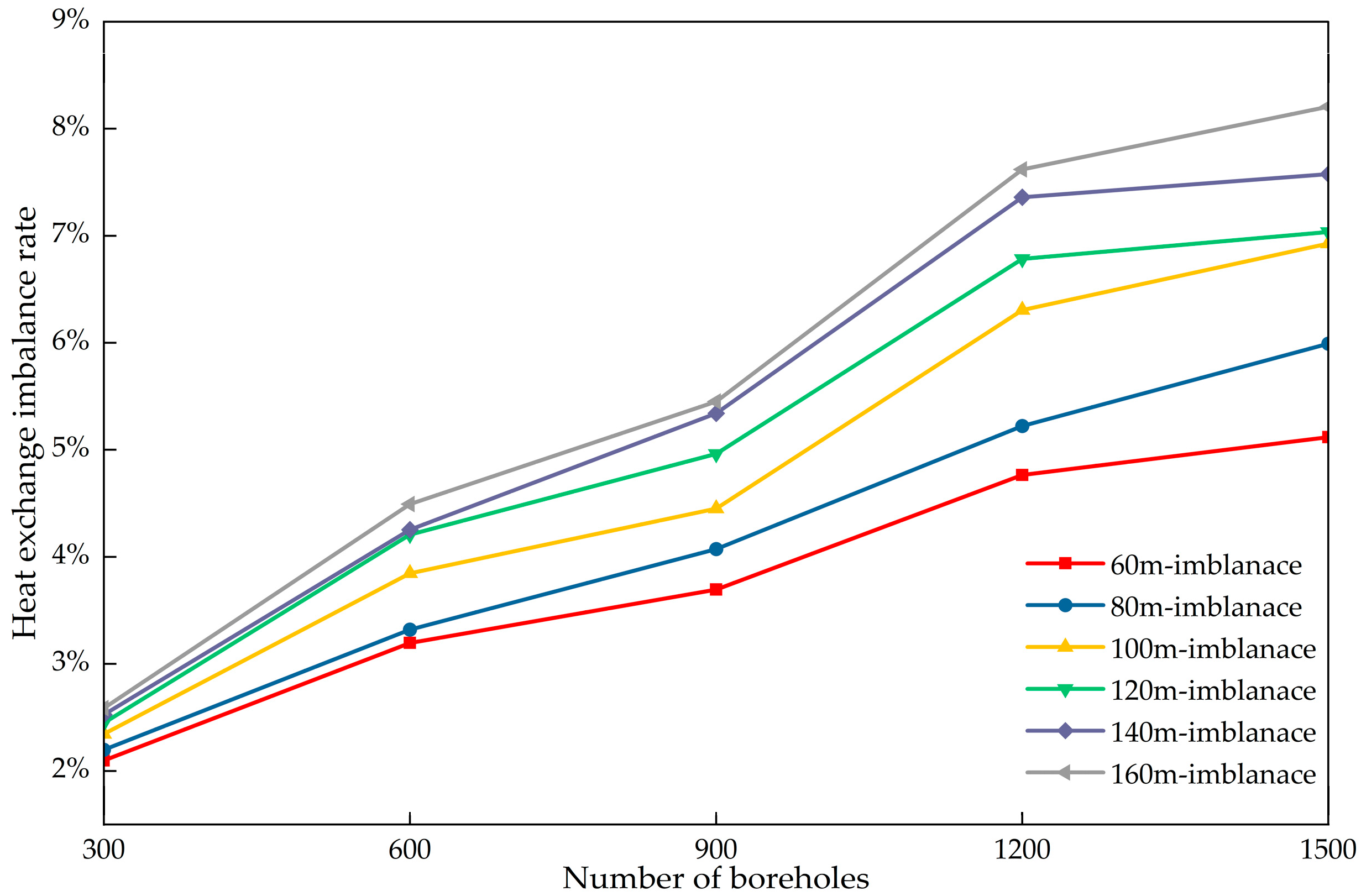

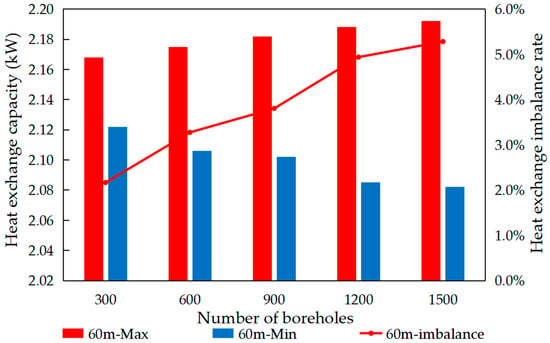

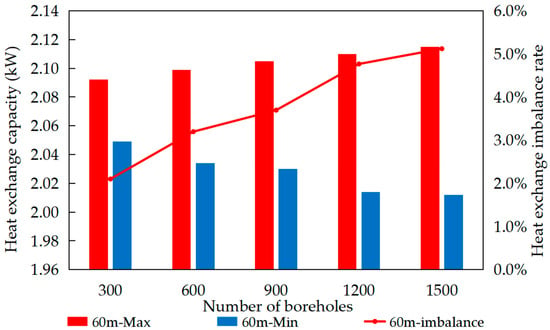

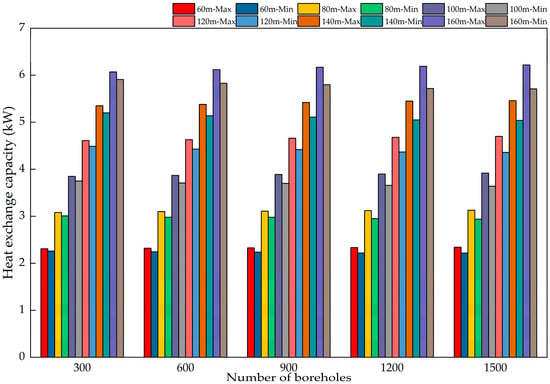

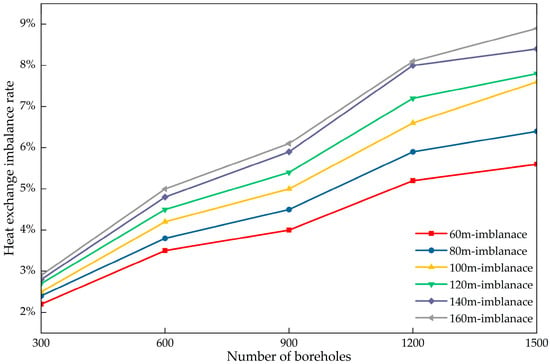

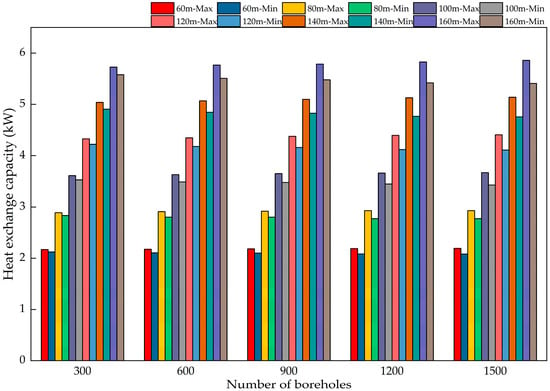

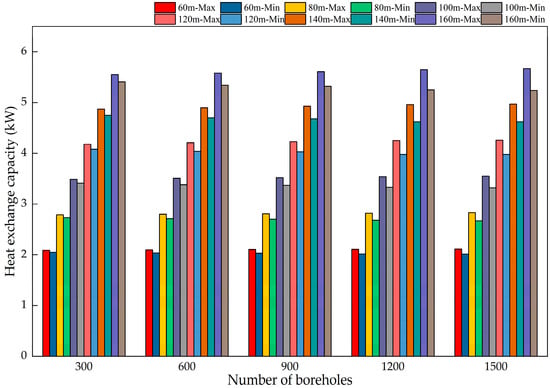

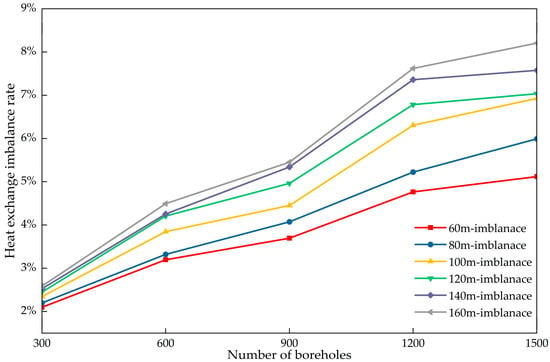

To further analyze the mechanism by which hydraulic imbalance affects heat exchange, simulations were conducted across the full range of 30 operating conditions. Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18, Figure 19 and Figure 20 present the heat exchange capacities and imbalance rates for the most and least favorable loops after operating durations of 10, 20, and 30 days, respectively.

Figure 15.

Simulation results of heat exchange for 30 different operating conditions within 10 days.

Figure 16.

Simulation results of heat transfer imbalance rate for 30 different operating conditions within 10 days.

Figure 17.

Simulation results of heat exchange for 30 different operating conditions within 20 days.

Figure 18.

Simulation results of heat transfer imbalance rate for 30 different operating conditions within 20 days.

Figure 19.

Simulation results of heat exchange for 30 different operating conditions within 30 days.

Figure 20.

Simulation results of heat transfer imbalance rate for 30 different operating conditions within 30 days.

As shown in Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18, Figure 19 and Figure 20, the heat exchange capacity increases with borehole depth for a given number of boreholes. At 60 m depth, the heat exchange capacities of the most and least favorable loops are approximately 2.3 kW and 2.2 kW, respectively. At 160 m, the corresponding capacities are approximately 6.0 kW and 5.9 kW.

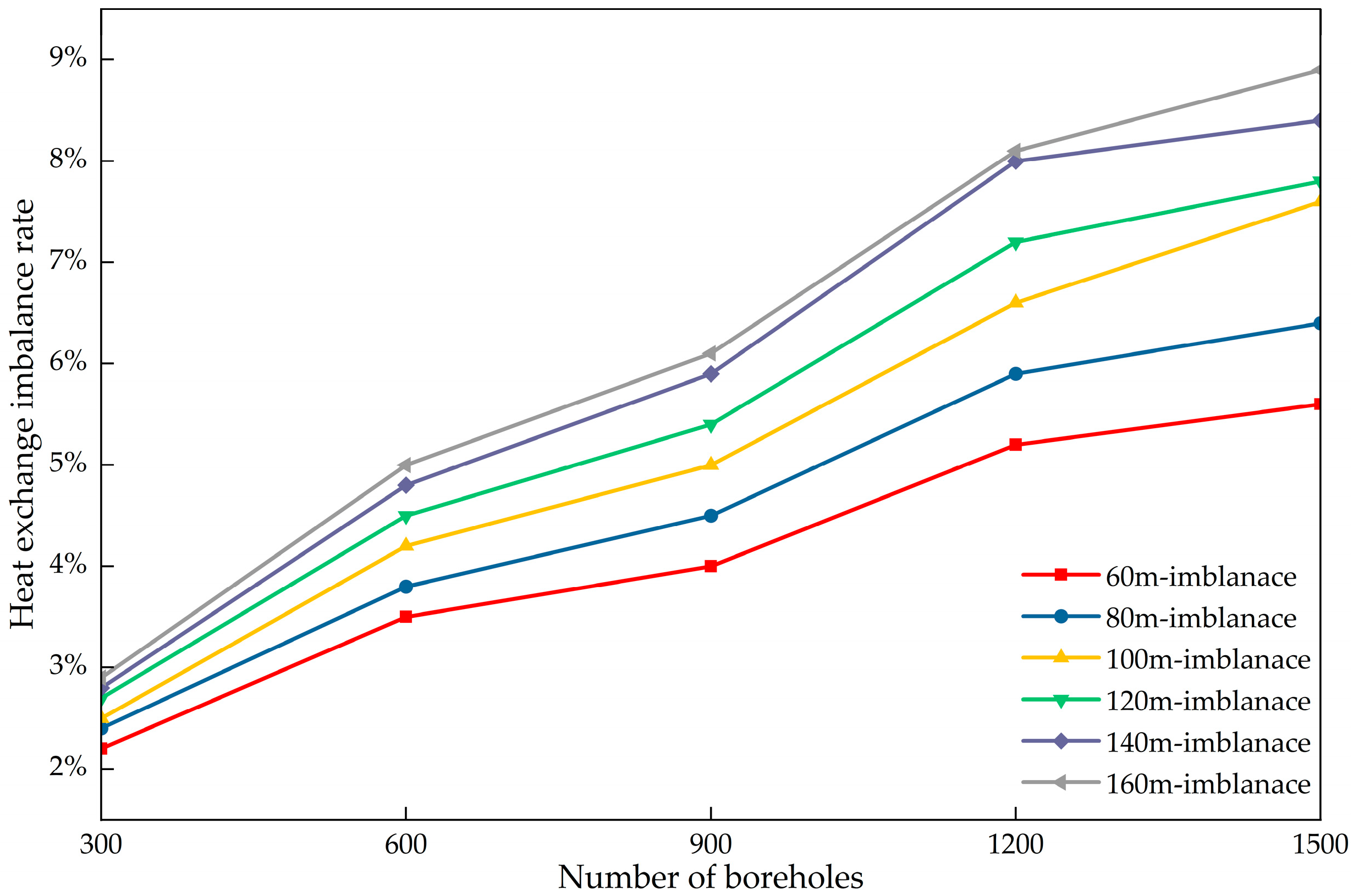

When the number of boreholes remains constant, the heat exchange imbalance rate steadily increases with increasing borehole depth. Furthermore, as the number of boreholes increases, the heat exchange imbalance rate grows more rapidly at greater depths. With 300 boreholes, the heat exchange imbalance rate is 2.2% at a borehole depth of 60 m and 2.9% at a depth of 160 m. When the number of boreholes reaches 1500, the heat exchange imbalance rate is 5.6% at a borehole depth of 60 m and 8.9% at a depth of 160 m. Increasing the number of boreholes from 300 to 1500 resulted in a 3.4% increase in the heat exchange imbalance rate at a depth of 60 m and a 6.0% increase at a depth of 160 m. At greater borehole depths, the heat exchange imbalance rate increases more rapidly as the system scale expands. This indicates that the heat exchange imbalance becomes more pronounced in systems featuring greater depths and larger scales.

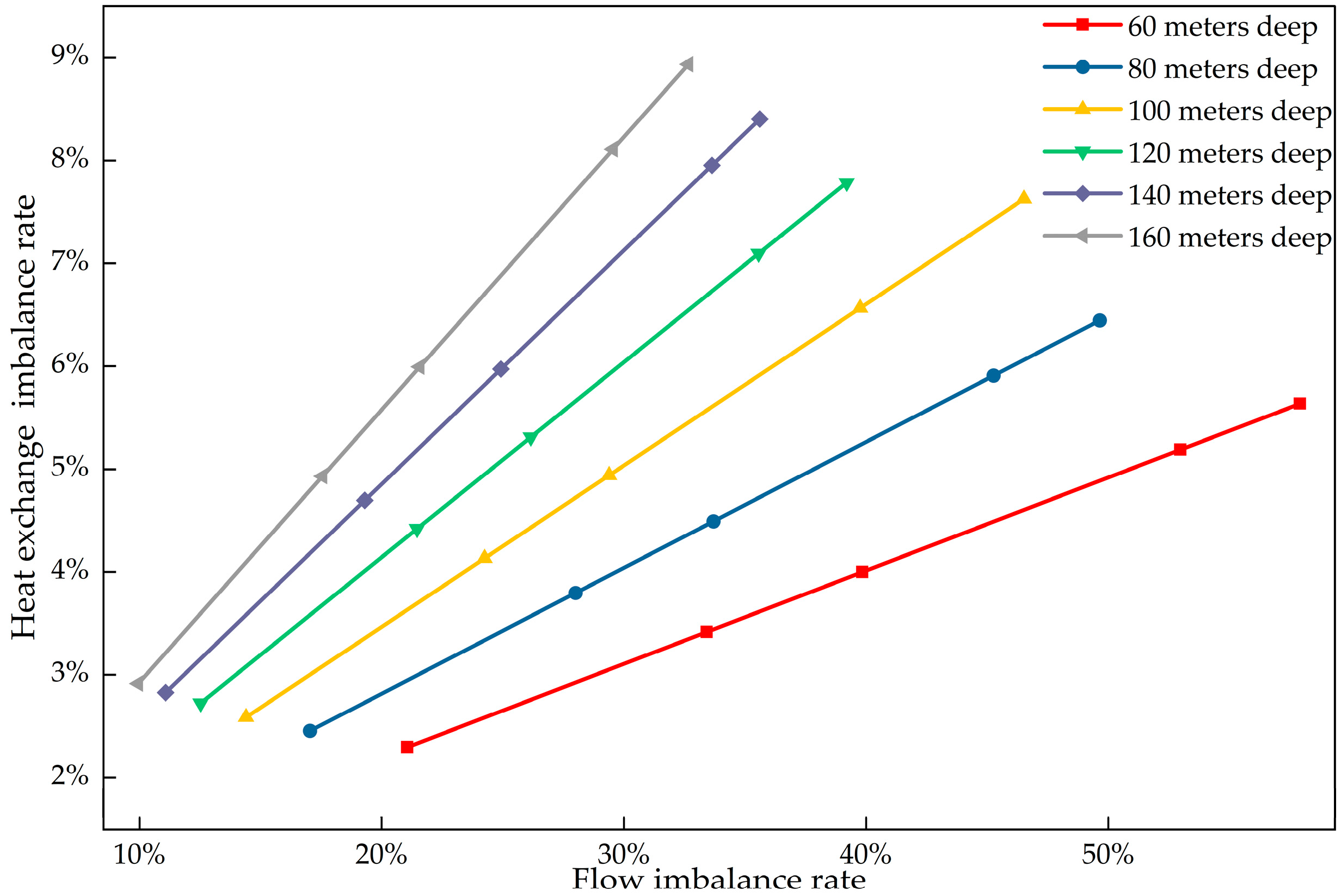

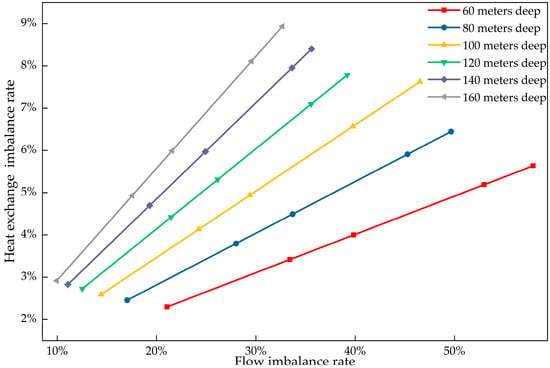

Based on the hydraulic and heat exchange simulation results from 30 operating conditions, a linear chart was plotted to illustrate the relationship between the flow imbalance rate and the heat exchange imbalance rate, as shown in Figure 21. This chart provides a clear visual tool for further optimization of system design and operating parameters.

Figure 21.

Relationship diagram between the heat exchange imbalance rate and the flow imbalance rate.

As clearly observed in Figure 21, for a borehole depth of 60 m, the corresponding straight line has the smallest slope, indicating the slowest increase in the heat exchange imbalance rate. Conversely, at a depth of 160 m, the slope is the steepest, indicating the most rapid increase. Empirical formula relating the flow imbalance rate to the heat exchange imbalance rate for borehole depths between 60 and 160 m were fitted based on the simulation results, as shown in Formula (15).

In the formula, δq denotes the heat exchange imbalance rate, k denotes the rate of change, and o denotes the intercept.

Table 7.

Numerical values for k and o.

In GHEs, convective heat transfer resistance has a relatively minor impact. Formula (15) and its corresponding parameters apply to borehole depths ranging from 60 to 160 m under similar geological conditions. In practical engineering applications, once the spatial distribution of the boreholes and the specific layout of the pipe system are defined, the lengths of the vertical and horizontal pipes can be precisely calculated. Based on this, the flow imbalance rate can be directly calculated, and subsequently, the heat transfer imbalance rate can be further determined based on the calculation results.

Here, we also selected a scenario with 300 boreholes and a drilling depth of 90 m to validate the formula. Based on the simulation results, the heat exchange imbalance rate under this operating condition was determined to be 2.46%.

Using linear interpolation to calculate k and o yields the following results: k = 0.13965; o = 0.0036. Substituting these values into the formula gives a heat transfer imbalance rate of 2.53%. Compared to the simulation results, the error of 2.8% falls within an acceptable range.

A critical finding is the limited impact of flow imbalance on heat exchange. Simulation results show that while the flow imbalance rate reaches 58%, the heat exchange imbalance rate remains below 9%. This is due to the dominance of soil thermal resistance. The total thermal resistance consists of internal convective resistance and external soil conduction resistance. Flow rate variations mainly affect the internal resistance. However, the external soil resistance is much larger than the internal resistance [38]. Therefore, even large flow fluctuations cause only minor changes in the total heat transfer coefficient. This explains the flat slope observed in Figure 21.

4.3. Applicability and Limitations of the Empirical Correlations

The proposed empirical correlations provide quantitative tools for predicting system imbalances. However, defining their range of applicability is essential.

Regarding the physical mechanism, the numerical model assumes pure heat conduction [25]. However, the thermal conductivity used here is an effective value. It is derived from in situ thermal response tests. This effective parameter implicitly accounts for groundwater advection. Therefore, the results reflect the actual geological heat transfer conditions.

In terms of the fitted parameters, the hydraulic parameters (a, b, d) in Formula (15) are primarily topology-dependent. In standard engineering, pipe diameters are selected to maintain specific frictional resistance. Under these conditions, hydraulic impedance is determined mainly by pipe length variations. Therefore, these parameters are transferable to other large-scale clusters with similar non-identical architectures.

In contrast, the thermal parameters (k, o) in Formula (16) apply to regions with comparable geology. As analyzed in Section 4.2.2, soil thermal resistance dominates the process. Consequently, the sensitivity coefficient k remains consistent for similar soils. Formula (16) thus serves as a valid engineering reference. Site-specific recalibration is not required for minor geological variations. It should be noted that the valid data range covers borehole depths of 60–160 m and cluster sizes of 300–1500 boreholes. Additionally, the system must operate within turbulent or transition flow regimes.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically analyzed the impact of borehole quantity, borehole depth, and operational duration on the hydraulic and thermal performance of large-scale GSHP systems. While the specific coefficients (a, b, d, k, o) reflect the geological parameters of the Shandong region, the underlying power-law mechanism and hydraulic–thermal coupling are transferable to similar large-scale projects. In practical engineering applications, the length ratio can be calculated during the construction design phase based on borehole distribution and pipe layout, thereby predicting hydraulic and thermal imbalances within the system. This allows for the prediction of potential hydraulic and thermal imbalances, thereby facilitating early issue identification and enabling the implementation of targeted optimization strategies to enhance system efficiency and stability. Key conclusions include the following:

- The length ratio Lv/h is related to the system flow imbalance rate by an formula of the form δf = a (Lv/h)^b + d, where Lv/h ranges from 0.1 to 1.4.

- The system flow imbalance rate satisfies a formula of the form δq = kδf + o with the heat exchange imbalance rate, where δf ranges from 10% to 58%. The deeper the borehole depth, the larger the value of k.

- In non-identical circuits for large-scale GSHP networks, an increase in the number of boreholes (from 300 to 1500) or a decrease in borehole depth (from 60 m to 160 m) can elevate the system flow imbalance rate (from 10% to 58%). This increase in the flow imbalance rate directly affects the heat exchange imbalance rate. However, external thermal resistance at the boreholes dominates the heat exchange process. Consequently, flow-induced variations remain relatively small at low fluid velocities, typically ranging from 2.2% to 9%.

It should be noted that the findings in this study are derived from comprehensive numerical simulations. Therefore, the proposed empirical correlations can serve as a theoretical reference for engineering design, particularly for systems with similar characteristics. Future research will aim to collect long-term operational data from actual engineering projects to further validate and refine these models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.C.; hydraulic calculation methods, T.C., Z.W. and J.L.; heat exchange calculation methods, W.Z., Z.W. and J.L.; data curation, Z.W. and J.L.; result analysis, Z.W. and J.L.; software, Z.W., J.L. and X.Z. (Xinlei Zhou); project administration, X.Z. (Xudong Zhao) and W.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.W.; supervision, P.C. and T.C.; validation, X.Z. (Xudong Zhao), X.Z. (Xinlei Zhou) and P.C.; writing—review and editing, X.Z. (Xudong Zhao), X.Z. (Xinlei Zhou) and P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work described in this paper is sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China through “Research on the Coupling Characteristics of Solar-Assisted Ground Source Heat Pump Direct Heating and Building Dynamic Load” (Grant Number: 52278115).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Jie Liu was employed by the company China Construction Industrial & Energy Engineering Group Co., Ltd. All authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GSHP | ground-source heat pump |

| GHE | ground heat exchanger |

| COP | coefficient of performance |

References

- Jia, L.; Lu, L.; Chen, J.; Gong, Q. Model development of deep space-source heat pump system and its feasibility analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 430, 139556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Lu, L.; Gong, Q.; Jiao, K. Analytical and experimental analyses on cooling performances of radiative SkyCool radiators with various interior flowing channels. Energy 2024, 295, 130907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.R.; Li, Q.Y.; Yang, J.; Han, J.; Lee, C.C.; Chen, J.H. Investigation of the Energy-Saving Potential of Buildings with Radiative Roofs and Low-E Windows in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.R.; Han, J.; Chen, X.; Li, Q.Y.; Lee, C.C.; Fung, Y.H. Interaction between thermal comfort, indoor air quality and ventilation energy consumption of educational buildings: A comprehensive review. Buildings 2021, 11, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Zhang, Y. An overview of world geothermal power generation and a case study on China—The resource and market perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 112, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.S.; Kolo, I.; Banks, D.; Falcone, G. Comparison of the thermal and hydraulic performance of single U-tube, double U-tube and coaxial medium-to-deep borehole heat exchangers. Geothermics 2024, 117, 102888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, P.; Yang, W.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, K.; Spitler, J.D.; Yu, M. Advances in ground heat exchangers for space heating and cooling: Review and perspectives. Energy Built Environ. 2024, 5, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, N.; Zhou, C.; Luo, Y.; Shen, J.; Tian, Z.; Sun, D.; Fan, J.; Zhang, L.; Deng, J.; Rosen, M.A. Thermal behavior and performance of shallow-deep-mixed borehole heat exchanger array for sustainable building cooling and heating. Energy Build. 2023, 291, 113108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, P.; Diao, N.; Gao, C.; Fang, Z. Thermal investigation of in-series vertical ground heat exchangers for industrial waste heat storage. Geothermics 2015, 57, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.; Bae, S.; Chae, H.; Nam, Y. Feasibility study on the optimal design method of ground-water source hybrid heat pump system applied to office buildings. Renew. Energy 2024, 228, 120555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Rohn, J.; Xiang, W.; Bertermann, D.; Blum, P. A review of ground investigations for ground source heat pump (GSHP) systems. Energy Build. 2016, 117, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, J.W.; Toth, A.N. Direct utilization of geothermal energy 2020 worldwide review. Geothermics 2021, 90, 101915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, C.J.; Liu, H.; Riffat, S.B. Comparative performance of ‘U-tube’ and ‘coaxial’ loop designs for use with a ground source heat pump. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2012, 37, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Yang, J.; Zheng, C. Research on Hydraulic Characteristics of U-Tube Heat Exchanger Loop in Ground-Coupled Heat Pump System. Procedia Eng. 2017, 205, 3186–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, S.; Spitler, J.D. Vertical ground heat exchanger pressure loss—Experimental comparisons and calculation procedures. Geothermics 2022, 105, 102546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Gong, G.; Zeng, L. Investigation for a novel optimization design method of ground source heat pump based on hydraulic characteristics of buried pipe network. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 182, 116069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.; Pu, L.; Ma, Z.; Xia, L.; Li, Y. Effects of ground heat exchangers with different connection configurations on the heating performance of GSHP systems. Geothermics 2019, 80, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agson-Gani, P.H.; Zueter, A.F.; Xu, M.; Ghoreishi-Madiseh, S.A.; Kurnia, J.C.; Sasmito, A.P. Thermal and hydraulic analysis of a novel double-pipe geothermal heat exchanger with a controlled fractured zone at the well bott. Appl. Energy 2022, 310, 118407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.; Bolisetti, T.; Ting, D.S.-K.; Reitsma, S. Short-term fluid temperature variations in either a coaxial or U-tube borehole heat exchanger. Geothermics 2017, 67, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Xu, G.; Cheng, N. Proposing stratified segmented finite line source (SS-FLS) method for dynamic simulation of medium-deep coaxial borehole heat exchanger in multiple ground layers. Renew. Energy 2021, 179, 604–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll, L.R.; Zobel, O.J.; Ingersoll, A.C. Heat conduction with engineering, geological, and other applications. Phys. Today 1955, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.Y.; Diao, N.R.; Fang, Z.H. A finite line-source model for boreholes in geothermal heat exchangers. Heat Transf. Asian Res. 2002, 31, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, P.; Zhang, W.; Liu, R.; Lu, L.; Jia, L. Analytical model development for vertical medium/deep ground heat exchangers with U-tube(s). Int. Commun. Heat Mass. 2024, 159, 107969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Diao, N.; Shao, Z.; Zhu, K.; Fang, Z. A computationally efficient numerical model for heat transfer simulation of deep borehole heat exchangers. Energy Build. 2018, 167, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingzhi, Y.; Wei, L.; Fangfang, Z.; Wenke, Z.; Ping, C.; Zhaohong, F. A novel model and heat extraction capacity of mid-deep buried U-bend pipe ground heat exchangers. Energy Build. 2021, 235, 110723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Yu, J.; Yan, T.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X. Improved analytical modeling and system performance evaluation of deep coaxial borehole heat exchanger with segmented finite cylinder-source method. Energy Build. 2020, 212, 109829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Guo, H.; Meggers, F.; Zhang, L. Deep coaxial borehole heat exchanger: Analytical modeling and thermal analysis. Energy 2019, 185, 1298–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, W.; Sørensen, B.R.; Cui, P.; Man, Y.; Yu, M.; Fang, Z. Comparative analysis of heat transfer performance of coaxial pipe and U-type deep borehole heat exchangers. Geothermics 2021, 96, 102220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; You, S.; Zheng, X.; Cong, P.; Shi, J.; Li, B.; Wang, L.; Wei, S. Mathematical modeling and periodical heat extraction analysis of deep coaxial borehole heat exchanger for space heating. Energy Build. 2022, 265, 112102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.J.; Jia, L.R.; Zhang, W.S.; Yu, M.Z.; Zhao, X.D.; Cui, P. Study of Heat Transfer Characteristics and Economic Analysis of a Closed Deep Coaxial Geothermal Heat Exchanger Retrofitted from an Abandoned Oil Well. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, W.; Ding, G.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, X.; Zhang, L.; Cui, P. Analysis of the factors influencing heat transfer and control strategy optimization for Medium-Shallow array borehole heat exchangers. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 244, 122788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Cui, P.; Yu, M. Investigation on the heat transfer characteristics of the U-tube and the coaxial tube medium-shallow borehole heat exchangers. Renew. Energy 2025, 248, 123145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Xiao, Y. Fluid Network for Transportation and Distribution, 4th ed.; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2018; pp. 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Ateş, S. Hydraulic modelling of closed pipes in loop equations of water distribution networks. Appl. Math. Model. 2016, 40, 966–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Han, Y. Variable Pressure Difference Control Method for Chilled Water System Based on the Identification of the Most Unfavorable Thermodynamic Loop. Buildings 2024, 14, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, N.; Cui, P.; Fang, Z. The thermal resistance in a borehole of geothermal heat exchanger. In Proceedings of the 12th International Heat Transfer Conference, Grenoble, France, 18–23 August 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lamarche, L.; Kajl, S.; Beauchamp, B. A review of methods to evaluate borehole thermal resistances in geothermal heat-pump systems. Geothermics 2010, 39, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, H. Comprehensive analysis for thermal resistance of ground heat exchanger and hydraulic balance. Renew. Energy Resour. 2014, 32, 1359–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.