Impact of University Building Thermal Environments on Thermal Comfort and Learning Efficiency: A Study Under Conditions of Hot Summer and Cold Winter

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

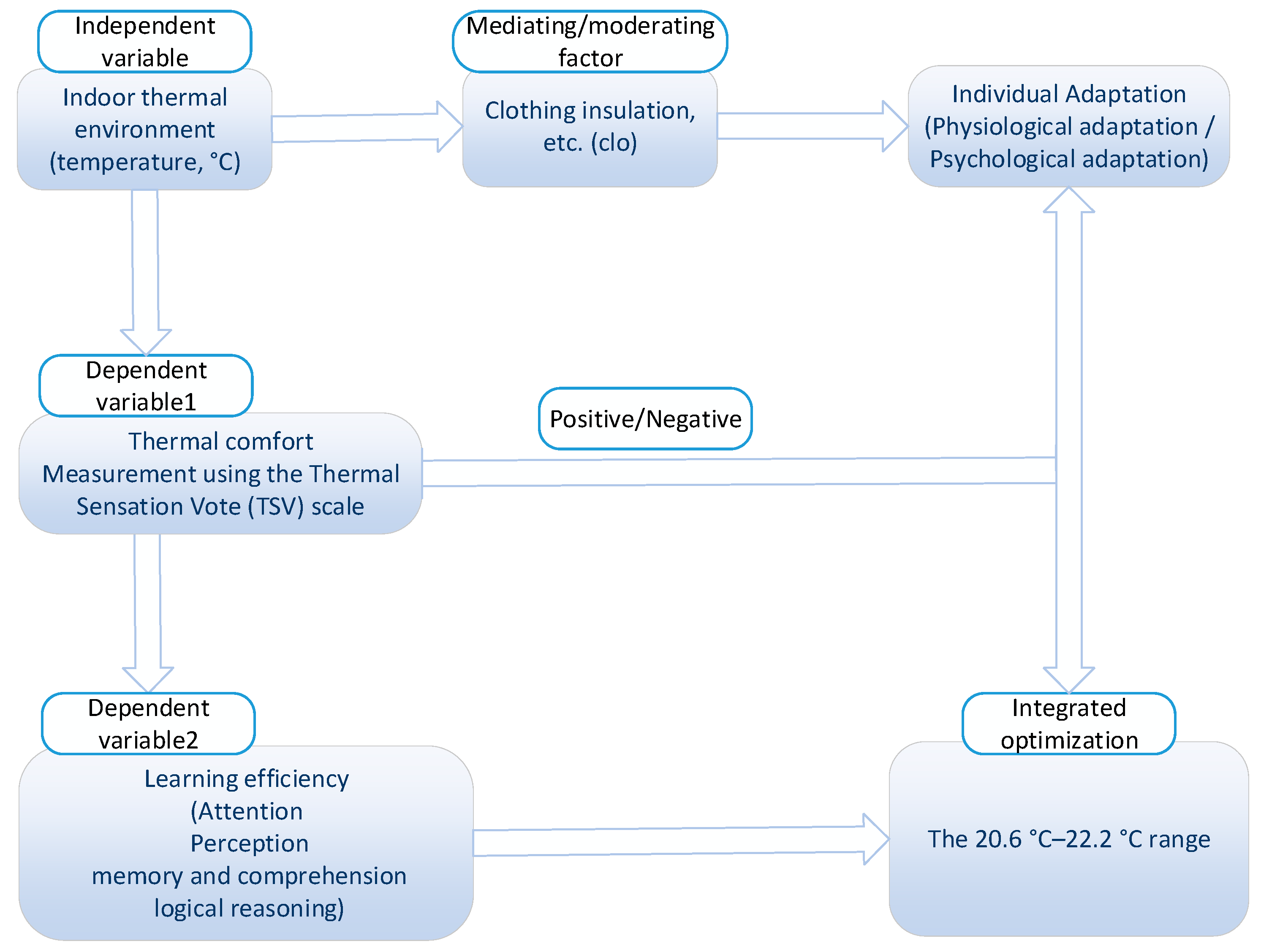

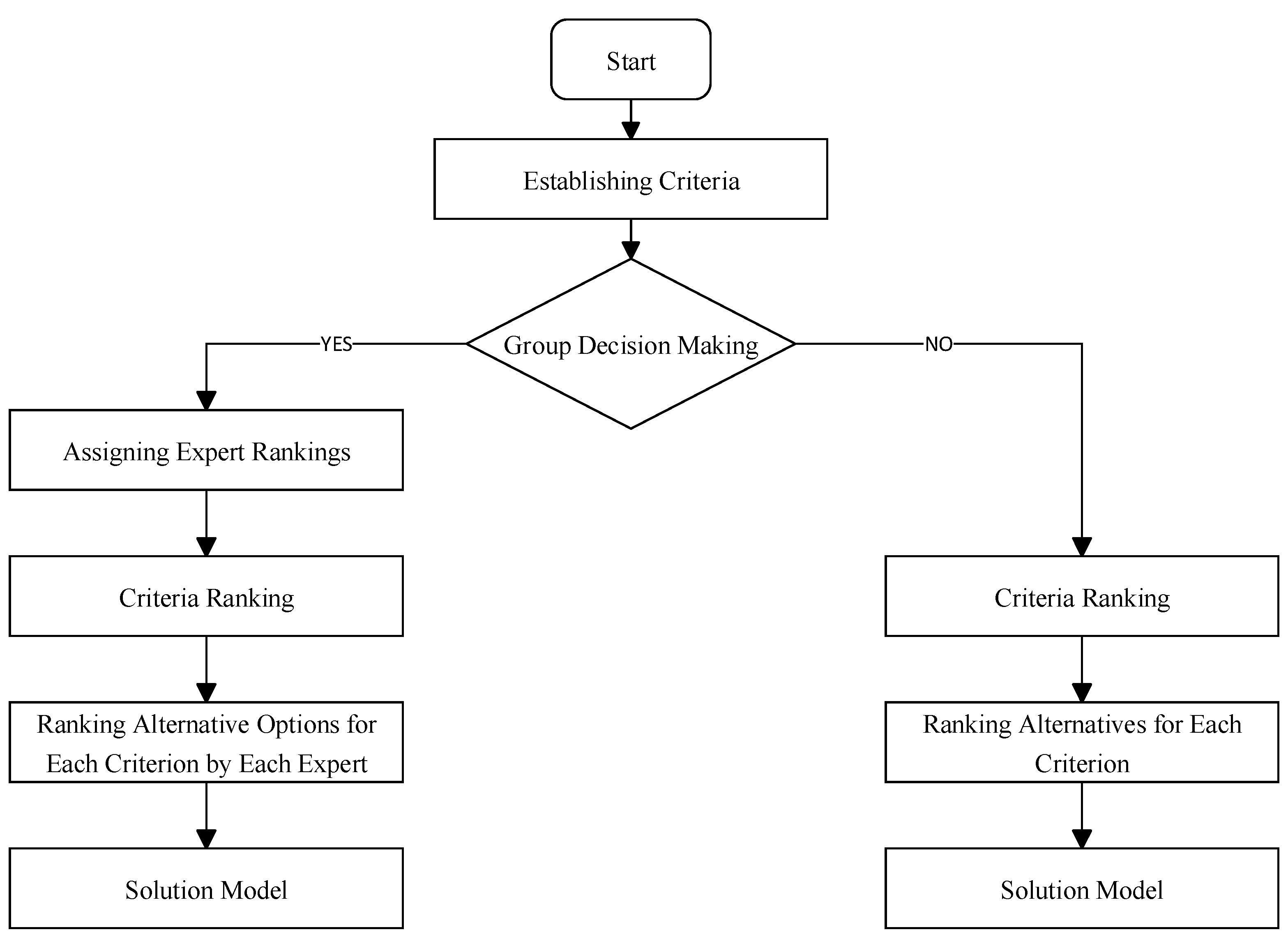

2.1. Study Framework

2.2. Thermal Comfort Research Methods

- Theoretical models based on heat balance, represented by the Predicted Mean Vote (PMV) and its derivative, the Predicted Percentage of Dissatisfied (PPD). Originating from Professor Fanger’s steady-state heat balance equation [38], this model objectively predicts the average thermal sensation (PMV) of most people in a given environment and the expected percentage feeling dissatisfied (PPD) by calculating the balance between human heat production and dissipation. Its strength lies in a complete theoretical framework, making it a core component of international standards. It is particularly suited for fully air-conditioned, steady-state environments with low air velocity, stable metabolic rates, and relatively uniform clothing. However, the model requires high precision in input parameters and has limitations in reflecting individual differences, dynamic environments, or the actual adaptive behaviors of occupants in naturally ventilated buildings.

- Adaptive models based on behavioral adaptation. This model posits that thermal comfort is not determined solely by physical parameters but is significantly influenced by behavioral adjustments, psychological expectations, and past thermal experiences. It typically establishes regression relationships between outdoor temperature and the actual acceptable or neutral indoor temperature through field studies. Adaptive models are more aligned with naturally ventilated, semi-open, or user-adjustable indoor environments and are used to define comfort zones for such contexts. Their limitation is a stronger dependency on regional and cultural factors, resulting in relatively lower model universality.

- Direct subjective evaluation metrics. These methods obtain immediate feedback from users via questionnaires and form the cornerstone of empirical research. Commonly used metrics include:

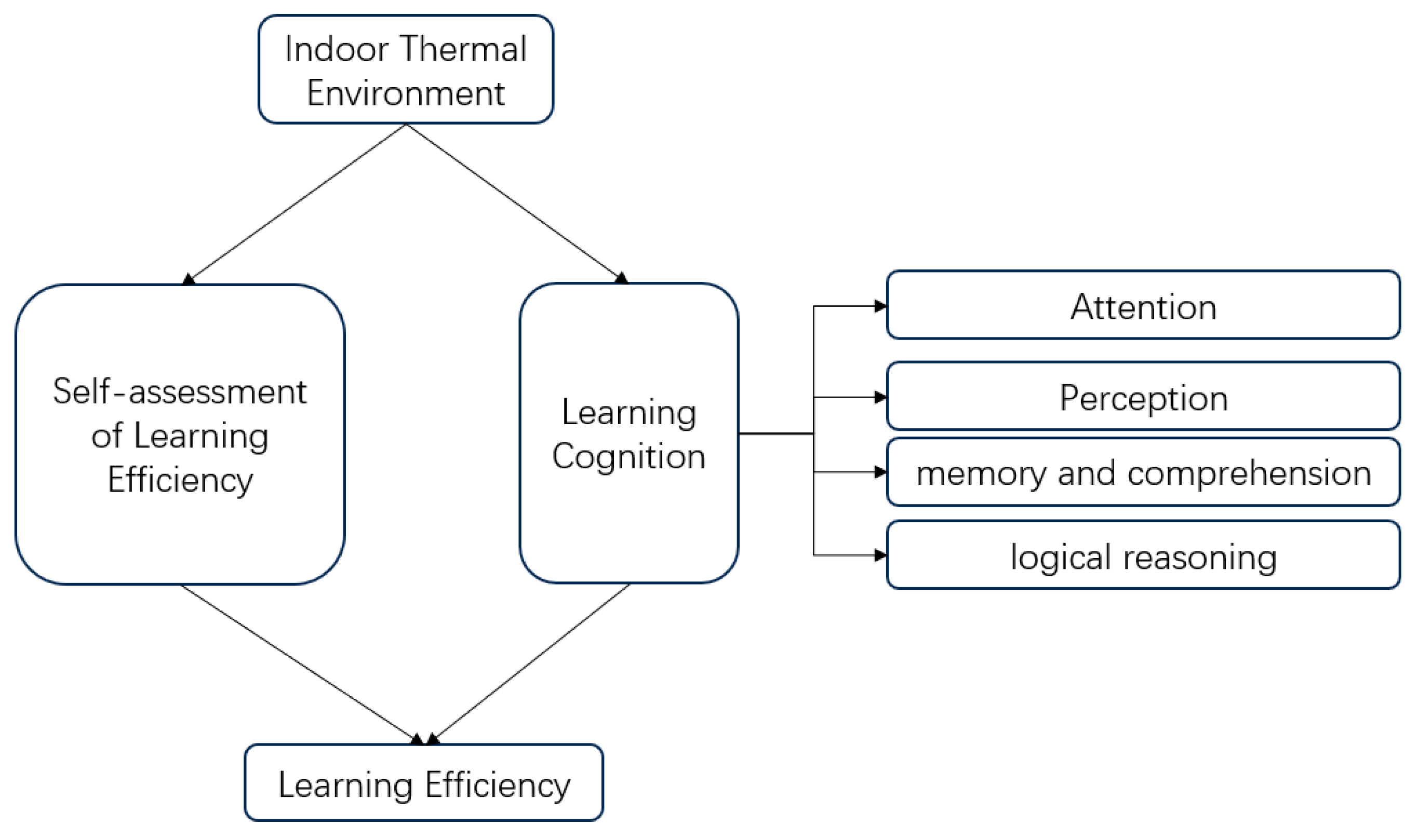

2.3. Methods of Evaluating Learning Efficiency

Mechanisms of the Effect of Indoor Thermal Environments on Learning Efficiency

- Self-evaluation of Learning Efficiency

- 2.

- Evaluation of Cognitive Learning Abilities

- 3.

- Factor Analysis of Cognitive Learning Abilities Evaluation

- 4.

- Calculation of Effect Size

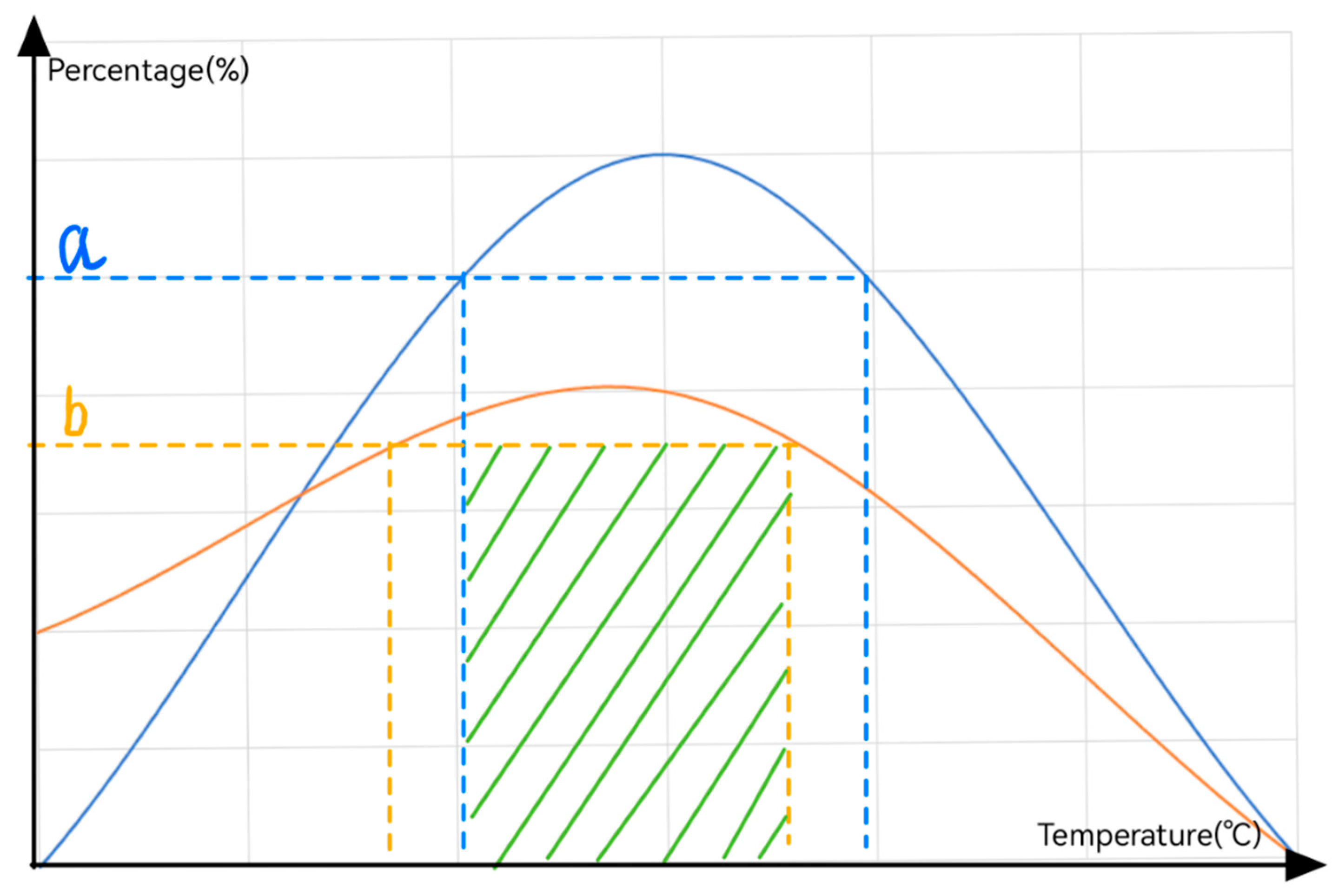

2.4. Comprehensive Analysis of the Impact of Thermal Comfort on Learning Efficiency

- Method of Determination

2.5. Overview of the Experiment

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.1.1. Subjective Thermal Comfort Evaluation

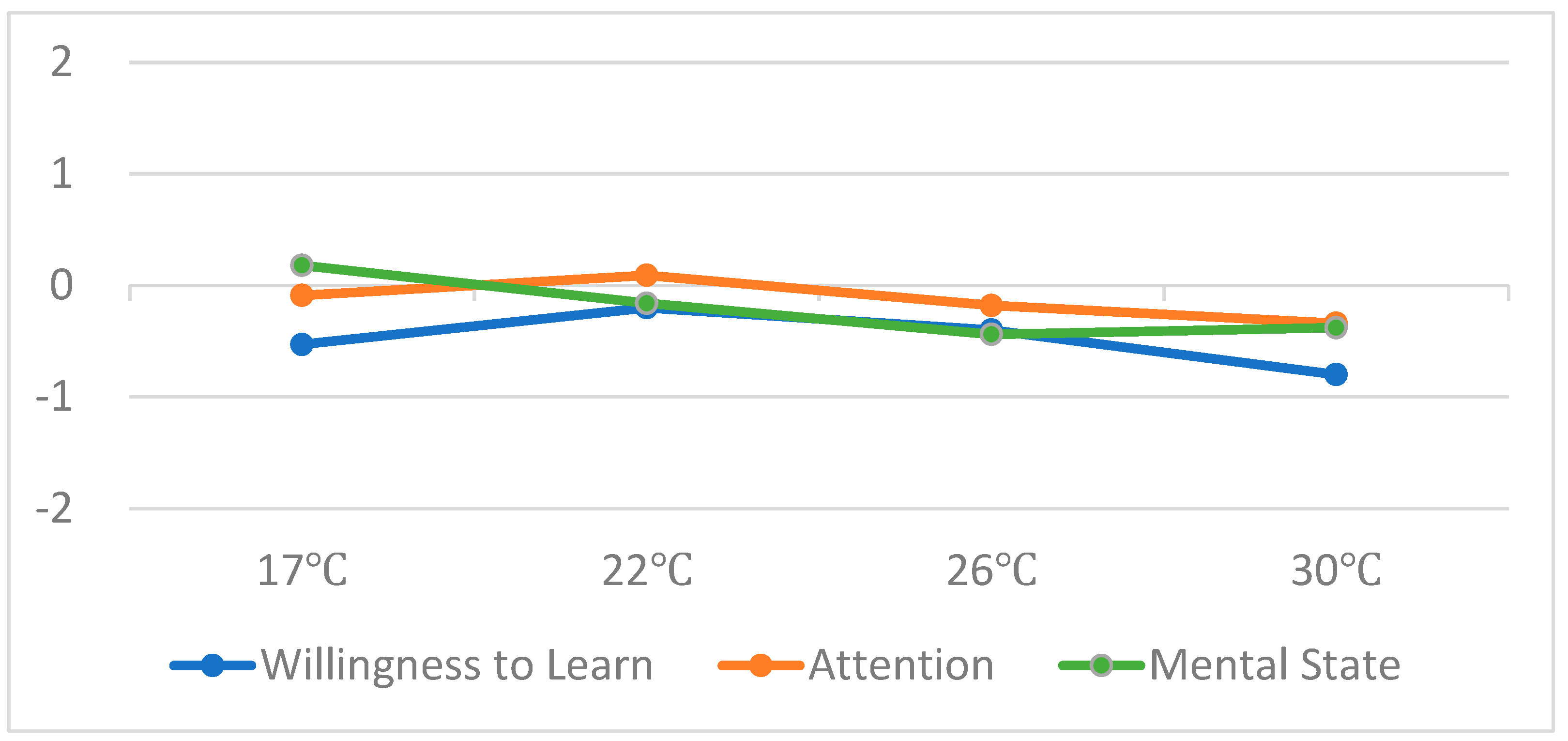

3.1.2. Self-Evaluation of Learning Efficiency

3.1.3. Results of Cognitive Learning Abilities Testing

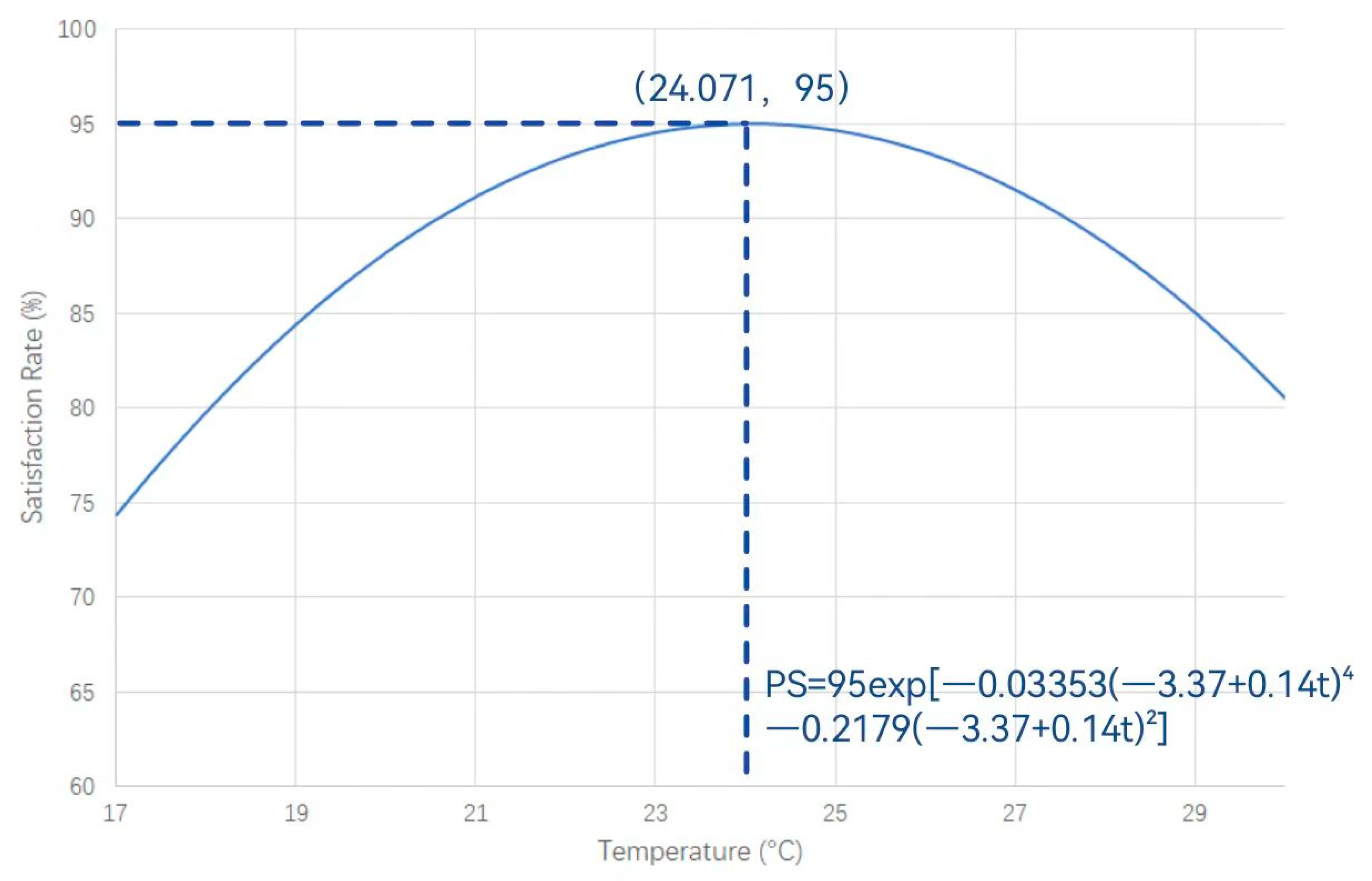

3.2. Quantitative Analysis of the Impact of Temperature on Thermal Comfort

- PS refers to Percentage of Satisfied.

- TSV refers to the actual thermal sensation vote curve.

3.3. Quantitative Analysis of the Impact of Temperature on Learning Efficiency

- Pi refers to the Percentage Normalized Score.

- xi refers to the composite index of the i-th participant.

3.4. Analysis of Indoor Temperature Values Based on the Requirements for Thermal Comfort and Learning Efficiency

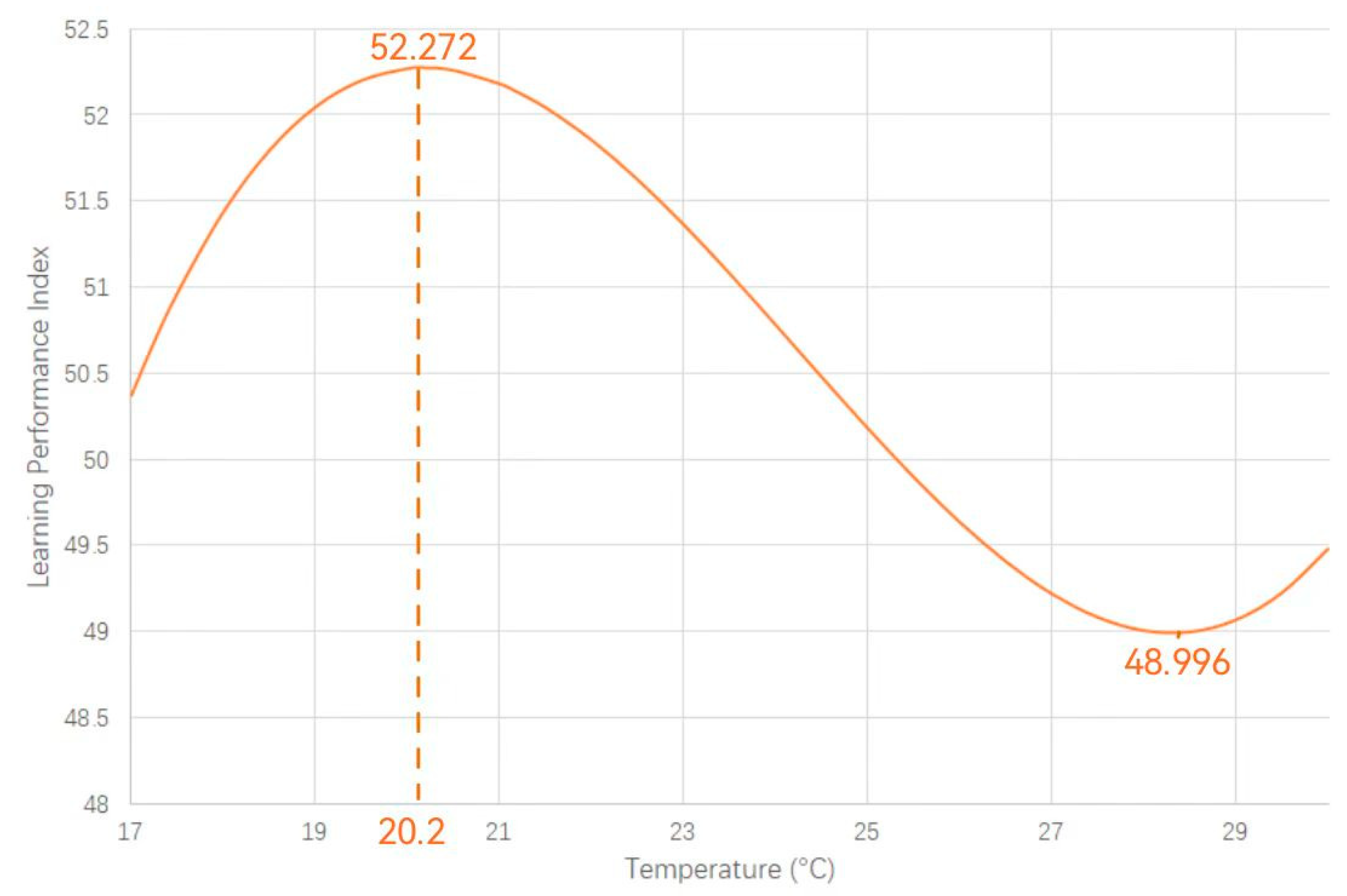

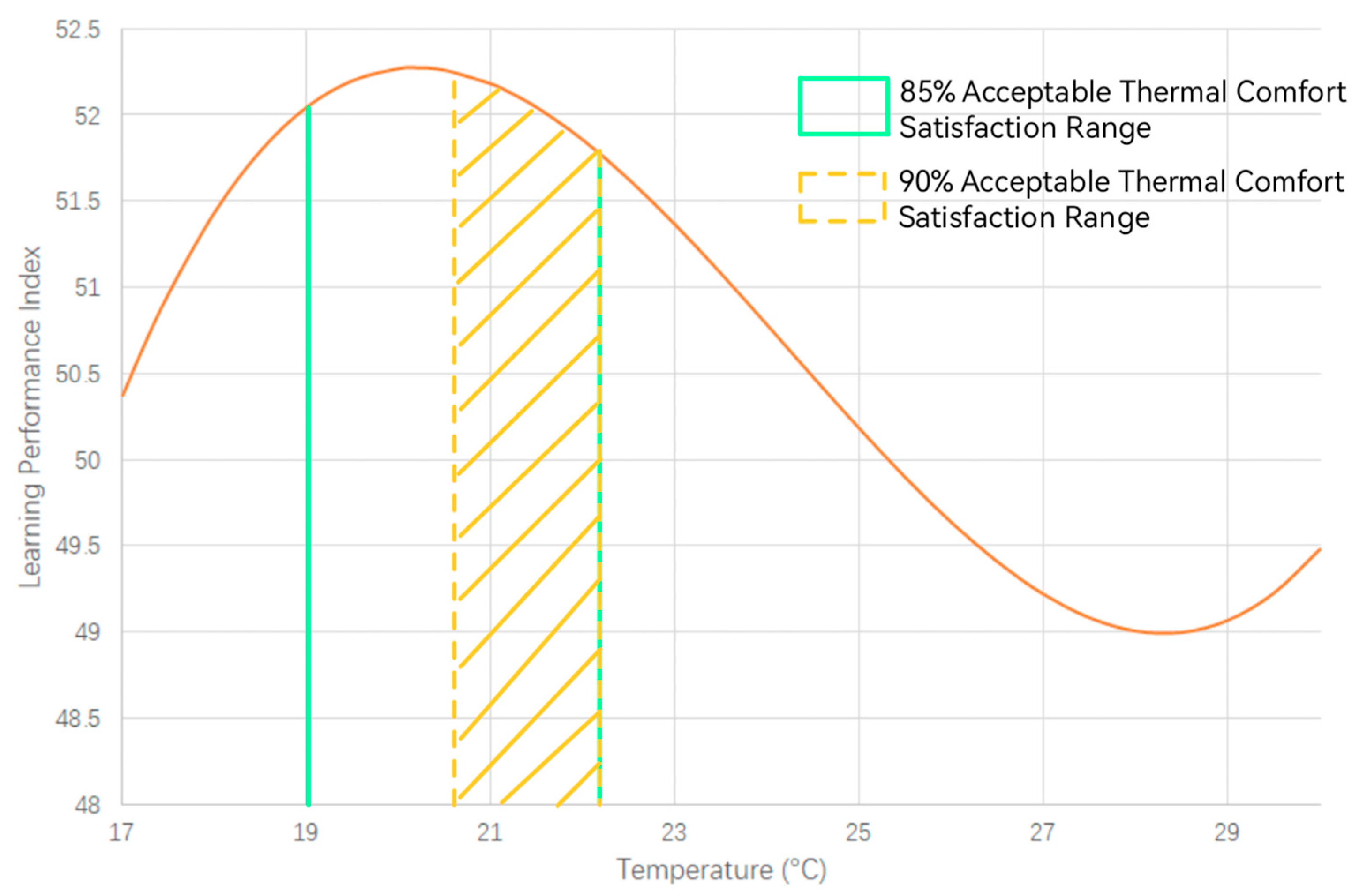

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary and Recommendations

- Between 17 °C and 24 °C, as the temperature increases, the thermal sensation shifts from −1 to 0 (subjectively feeling cold to comfortable). Between 24 °C and 30 °C, with further temperature rise, the thermal sensation changes from 0 to 1 (subjectively feeling comfortable to warm). The most comfortable thermal sensation is reported at 24 °C.

- The analysis shows that the optimal thermal comfort temperature corresponds to 24 °C, while the optimal learning efficiency temperature is 20.2 °C, with a temperature difference of 3.8 °C. A comprehensive comparison reveals that university students exhibit better learning efficiency in slightly cooler environments.

- Based on the combined optimal values for both thermal comfort and high learning efficiency, the ideal temperature range lies between 20.6 °C and 22.2 °C.

5.2. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TSV | Thermal Sensation Voting |

| OPA | Ordinal Priority Approach |

| DEST | Digit-Symbol Substitution Test |

| AC | Accuracy |

| RT | Response time |

| LP | Learning Performance |

| ES | Effect size |

| PS | Percentage of Satisfied |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Subjective Sensation Evaluation Table

| 1. Basic Information |

| Gender: □ Male □ Female Age: ______ Height: ______ Weight (kg): ______ Upper Clothing: □ Sleeveless □ Short-sleeve Shirt □ Long-sleeve Shirt □ Thin Long-sleeve □ Other______ Lower Clothing: □ Casual Pants □ Jeans □ Shorts □ Short Skirt □ Mid-length Skirt □ Long Skirt □ Other______ Shoes: □ Sandals □ Sports Shoes □ Canvas Shoes □ Other______ 2. How do you currently feel about the thermal sensation? (Single-choice question) □ Very Hot □ Hot □ Comfortable □ Cool □ Very Cool 3. How would you like the indoor temperature to change? (Single-choice question) |

| □ Higher □ Slightly Higher □ No Change □ Slightly Lower □ Lower |

| 4. Are you satisfied with the thermal comfort of the current environment? □ Very Satisfied □ Satisfied □ Neutral □ Dissatisfied □ Very Dissatisfied |

Appendix A.2. Self-Evaluation of Learning Efficiency

| 1. What is your current willingness to learn? (Single choice question) □ Very high □ High □ Moderate □ Low □ Very low 2. How would you describe your current attention level? (Single choice question) □ Very focused □ Focused □ Moderate □ Low □ Very low 3. Do you feel drowsy during the test? (Single choice question) □ Very alert □ Quite alert □ Just right □ A bit drowsy □ Drowsy |

Appendix A.3. Scale Items

| Digital-Symbol Test | ||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||

| Λ | σ | = | < | > | Χ | Π | + | − | ||

| 3 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 9 | 2 | |

| 5 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 9 | |

| 1 | 4 | 8 | 9 | 2 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 7 | |

| 5 | 3 | 8 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 2 | |

| 3 | 9 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 9 | |

| 5 | 9 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 6 | |

| Time Taken: | ||||||||||

| Digit Recognition (Adjacent Numbers Add Up to 10) |

23687569826765796916786493852869 56826457851913765867864729856746 54687326584968361568456969445967 67342757964578627895764657947458 56486485169865264735796237465545 66285693668967565485756458648768 Time Taken: |

| Meaningless Pattern Recognition |

|

|

| Logical Reasoning |

| During a 6-day vacation period, the company needs to arrange one person on duty each day. The finance, research and development, human resources, logistics, legal, and sales departments each recommended two people, so there are 12 people to choose from. Each person can be on duty for at most one day. The scheduling requirements are: 1. People from the legal department should not be scheduled for duty on the second and fourth days. 2. If a person from the logistics department is scheduled for duty, they can only be scheduled on a day immediately after a person from the legal department. 3. If a person from the research and development department is scheduled for duty, they can only be scheduled on a day immediately after a person from the logistics department. 1. Regarding the selection of people for the 6 days, which of the following schedules meets the above conditions? (A) Finance, Human Resources, Logistics, Legal, Finance, Human Resources (B) Sales, Finance, Legal, Human Resources, Finance, Sales (C) Human Resources, Finance, Legal, Research and Development, Legal, Logistics (D) Legal, Sales, Human Resources, Logistics, Finance, Sales 2. On which days can the logistics department personnel be scheduled for duty? (A) Only the second, fourth, and fifth days (B) Only the first, third, and fifth days (C) Only the second and sixth days (D) Only the first and third days 3. If two people from the logistics department are scheduled for duty, which of the following is definitely incorrect? (A) The first day arranges a person from the research and development department for duty (B) The sixth day arranges a person from the human resources department for duty (C) The third day arranges a person from the finance department for duty (D) The fifth day arranges a person from the legal department for duty 4. If two people from the finance department are scheduled for duty on the third and fifth days, which of the following sets of people could be scheduled for duty on the first and sixth days? (A) Logistics department and legal department (B) Legal department and sales department (C) Finance department and sales department (D) Research and development department and human resources department |

References

- De Giuli, V.; Da Pos, O.; De Carli, M. Indoor environmental quality and pupil perception in Italian primary schools. Build. Environ. 2012, 56, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, P.; Buratti, C. Environmental quality of university classrooms: Subjective and objective evaluation of the thermal, acoustic, and lighting comfort conditions. Build. Environ. 2018, 127, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendell, M.J.; Heath, G.A. Do indoor pollutants and thermal conditions in schools influence student performance? A critical review of the literature. Indoor Air 2005, 15, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mors, S.T.; Hensen, J.L.M.; Loomans, M.G.L.C.; Boerstra, A.C. Adaptive thermal comfort in primary school classrooms: Creating and validating PMV-based comfort charts. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 2454–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbhuiya, S.; Barbhuiya, S. Thermal comfort and energy consumption in a UK educational building. Build. Environ. 2013, 68, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Gao, X.-Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.-R.; Zhong, L.-L. Current Situation and Countermeasures of Drought Resistance Plan Construction. J. Catastrophology 2024, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S.L.; Péan, C.; Berger, S.; Caud, N.; Chen, Y.; Goldfarb, L.; Gomis, M. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Contribution of working group I to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change; Cambridge University: Cambridge, UK, 2021; Volume 2, p. 2391. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, S.; Gomez, D.; Dawidowski, L. Artificial neural network for the identification of unknown air pollution sources. Atmos. Environ. 1999, 33, 3045–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjiiski, L.; Hopke, P. Application of artificial neural networks to modeling and prediction of ambient ozone concentrations. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2000, 50, 894–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, L.; Liu, Y. Carbon monoxide levels in popular passenger commuting modes traversing major commuting routes in Hong Kong. Atmos. Environ. 2001, 35, 2637–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Leung, A.Y.; Yuen, K. A preliminary study of ozone trend and its impact on environment in Hong Kong. Environ. Int. 2002, 28, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corani, G. Air quality prediction in Milan: Feed-forward neural networks, pruned neural networks and lazy learning. Ecol. Model. 2005, 185, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.-Z.; Wang, X.-K. Investigation of respirable suspended particulate trend and relevant environmental factors in Hong Kong downtown areas. Chemosphere 2008, 71, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.-Z.; He, H.-D.; Leung, A.Y. Assessing air quality in Hong Kong: A proposed, revised air pollution index (API). Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 2562–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.-Z.; Wang, D. Learning machines: Rationale and application in ground-level ozone prediction. Appl. Soft Comput. 2014, 24, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Zou, T.; Guo, B.; Li, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.; Huang, H.; Chen, S.X. Assessing Beijing’s PM2. 5 pollution: Severity, weather impact, APEC and winter heating. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2015, 471, 20150257. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Ding, W. Prediction of air pollutants concentration based on an extreme learning machine: The case of Hong Kong. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadalavada, S.; Faust, O.; Salvi, M.; Seoni, S.; Raj, N.; Raghavendra, U.; Gudigar, A.; Barua, P.D.; Molinari, F.; Acharya, R. Application of artificial intelligence in air pollution monitoring and forecasting: A systematic review. Environ. Model. Softw. 2025, 185, 106312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standard 55-2017; Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy. ANSI: Washington, DC, USA; ASHRAE: Peachtree Corners, GA, USA, 2023.

- Teli, D.; Jentsch, M.F.; James, P.A.B. Naturally ventilated classrooms: An assessment of existing comfort models for predicting the thermal sensation and preference of primary school children. Energy Build. 2012, 53, 166–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teli, D.; James, P.A.; Jentsch, M.F. Thermal comfort in naturally ventilated primary school classrooms. Build. Res. Inf. 2013, 41, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corgnati, S.P.; Ansaldi, R.; Filippi, M. Thermal comfort in Italian classrooms under free running conditions during mid seasons: Assessment through objective and subjective approaches. Build. Environ. 2009, 44, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lin, Z. Extending Predicted Mean Vote using adaptive approach. Build. Environ. 2020, 171, 106665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lin, Z. Extended predicted mean vote of thermal adaptations reinforced around thermal neutrality. Indoor Air 2021, 31, 1217–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Cheng, Y.; Fang, Z.; Lin, Z. Improved algorithm for adaptive coefficient of adaptive Predicted Mean Vote (aPMV). Build. Environ. 2019, 163, 106318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.T.; Lim, J.H.; Cho, S.H.; Yun, G.Y. Development of the adaptive PMV model for improving prediction performances. Energy Build. 2015, 98, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, R.; Yu, W.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, B.; Essah, E.; Yao, R. Assessing energy saving potentials of office buildings based on adaptive thermal comfort using a tracking-based method. Energy Build. 2020, 208, 109611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Gao, S.; Zhai, Y. Field study on thermal comfort of open-plan office buildings in Xi’an in summer. Heat. Vent. Air Cond. 2024, 54, 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Liao, H. Study on Thermal Comfort in Indoor Environments During the Transitional Season Before and After Heating Cessation in Northern Office Buildings. Ind. Constr. 2023, 53, 145–149. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Chen, Y.; Hua, Y.; Kong, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Xu, Y. Characteristics of Residential Thermal Comfort and Energy Consumption in Winter in Hangzhou Based on Personal Comfort Systems. J. Tongji Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2024, 52, 480–488. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H. The effects of summer heat on academic achievement: A cohort analysis. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2017, 83, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyon, D.P.; Andersen, I.; Lundqvist, G.R. The effects of moderate heat stress on mental performance. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 1979, 5, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, P. Positive Analysis of the Relations of Study Efficiency and Indoor Temperature: Taking Guangdong Zhanjiang Normal College Library as an example. J. Libr. Inf. Sci. Agric. 2010, 22, 147–149+152. [Google Scholar]

- Sarbu, I.; Pacurar, C. Experimental and numerical research to assess indoor environment quality and schoolwork performance in university classrooms. Build. Environ. 2015, 93, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, S.; Weil, B. The relationship between comfort perceptions and academic performance in university classroom buildings. J. Green Build. 2016, 11, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50176-2016; Code for Thermal Design of Civil Buildings. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China; Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Lin, H. Research on the Effect of Indoor Environment of Buildingon Comfort and Learning Performance. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fanger, P. Fundamentals of thermal comfort. In Advances in Solar Energy Technology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1988; pp. 3056–3061. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. Influence and Evaluation Model of Indoor Physical Environment in Colleges and Universities Based on Learning Efficiency. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. Study on the Effects of Indoor thermal Environment on Students’ Concentration Ability and Learning Performance. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X. Analysis of Indoor Thermal Environment and Energy-Saving Optimization Design Based on Human Thermal Comfort at Jinan University for the Aged. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fariborzi, P.; Nguyen, K.; Mott, J. Classroom Conditions in Higher Education: Thermal Comfort and Effect on Student Success. ASHRAE Trans. 2023, 129, 385. [Google Scholar]

- Zeidner, M.; Endler, N.S. Handbook of Coping: Theory, Research, Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Research on The Impact of Indoor Light Environment on The Work Efficiency. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, M.W.; Dorling, S.R. Artificial neural networks (the multilayer perceptron)—A review of applications in the atmospheric sciences. Atmos. Environ. 1998, 32, 2627–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreutzer, J.; Deluca, J.; Caplan, B. Symbol digit modalities test. In Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; p. 2444. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, D.A.; Skalik, I.; House, D.E.; Hudnell, H.K. Neurobehavioral Evaluation System (NES): Comparative performance of 2nd-, 4th-, and 8th-grade Czech children. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 1996, 18, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lezak, M.D.; Howieson, D.B.; Loring, D.W.; Hannay, H.J.; Fischer, J.S. Neuropsychological Assessment, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004; Volume 162, p. 1237. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, L.; Lian, Z.; Pan, L.; Ye, Q. Neurobehavioral approach for evaluation of office workers’ productivity: The effects of room temperature. Build. Environ. 2009, 44, 1578–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataei, Y.; Mahmoudi, A.; Feylizadeh, M.R.; Li, D.-F. Ordinal Priority Approach (OPA) in Multiple Attribute Decision-Making. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 86, 105893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, S.; Cuthill, I.C. Effect size, confidence interval and statistical significance: A practical guide for biologists. Biol. Rev. 2007, 82, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, R.C.; Shenhav, A.; Straccia, M.; Cohen, J.D. The Eighty Five Percent Rule for optimal learning. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. Mechanism and Evaluation of the Effects of Indoor Environmental Quality on Human Productivity. Ph.D. Thesis, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y. Building Environment Science; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J. Research on Classroom Thermal Environment under the Comprehensive Impact of Thermal Comfort and Learning Performance During Winter in Rural Areas of NorthwestChina. Ph.D. Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, X.; Lei, Y.; Jing, S.; Yin, H. Research on Indoor Thermal Environment and Thermal Comfort of College Classrooms in Cold Regions. J. Huaqiao Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2022, 43, 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Ma, X.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, X.; Chen, Y.; Kojima, S. Study on the relationship between thermal comfort and learning efficiency of different classroom-types in transitional seasons in the hot summer and cold winter zone of China. Energies 2021, 14, 6338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppanen, O.; Fisk, W.J.; Lei, Q. Room Temperature and Productivity in Office Work. 2006. Available online: https://indoor.lbl.gov/publications/room-temperature-and-productivity (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Tanabe, S.; Nishihara, N. Productivity and fatigue. Indoor Air 2004, 14, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKay, D.G. The problems of flexibility, fluency, and speed–accuracy trade-off in skilled behavior. Psychol. Rev. 1982, 89, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wargocki, P.; Wyon, D.P. The Effects of Moderately Raised Classroom Temperatures and Classroom Ventilation Rate on the Performance of Schoolwork by Children (RP-1257). HVAC&R Res. 2007, 13, 193–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wargocki, P.; Porras-Salazar, J.A.; Contreras-Espinoza, S. The relationship between classroom temperature and children’s performance in school. Build. Environ. 2019, 157, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppanen, O.; Fisk, W.J.; Lei, Q. Effect of Temperature on Task Performance in Office Environment. 2006. Available online: https://indoor.lbl.gov/publications/effect-temperature-task-performance (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Yan, Z.; Wang, X.; Boud, D.; Lao, H. The effect of self-assessment on academic performance and the role of explicitness: A meta-analysis. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2023, 48, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification | Testing Tasks |

|---|---|

| Attention | Digit-Symbol Substitution Test (DEST) [49] |

| Perception | Amfimov Table—Digit Recognition [50] |

| memory and comprehension | Meaningless Figure Recognition [51] |

| logical reasoning | Verbal Deductive Reasoning [52] |

| Test Task | Indicator | 17 °C | 22 °C | 26 °C | 30 °C | p | ES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digit-Symbol Substitution Test (DEST) | AC (%) | 98.04 ± 7.97 | 97.28 ± 7.75 | 98.28 ± 6.94 | 98.10 ± 7.34 | 0.916 | 0.064 |

| RT (s) | 79.94 ± 13.17 | 78.76 ± 18.30 | 87.44 ± 17.01 | 91.32 ± 26.95 | <0.05 | 0.312 | |

| LP (AC/AT) | 1.25 ± 0.20 | 1.30 ± 0.31 | 1.16 ± 0.19 | 1.15 ± 0.29 | <0.05 | 0.286 | |

| Digit Recognition | AC (%) | 88.67 ± 6.82 | 86.38 ± 9.31 | 86.64 ± 8.02 | 88.58 ± 7.83 | 0.434 | 0.149 |

| RT (s) | 93.88 ± 22.17 | 94.02 ± 23.08 | 98.67 ± 27.74 | 114.16 ± 36.07 | <0.05 | 0.342 | |

| LP (AC/AT) | 0.98 ± 0.20 | 0.97 ± 0.23 | 0.93 ± 0.24 | 0.84 ± 0.26 | 0.057 | 0.249 | |

| Meaningless Figure Recognition | AC (%) | 60.30 ± 16.96 | 71.00 ± 18.79 | 73.60 ± 20.44 | 72.50 ± 20.09 | <0.05 | 0.287 |

| RT (s) | 25.32 ± 7.26 | 28.65 ± 13.78 | 24.94 ± 6.49 | 32.31 ± 14.18 | <0.05 | 0.273 | |

| LP (AC/AT) | 2.56 ± 0.98 | 2.90 ± 1.33 | 3.06 ± 0.96 | 2.57 ± 1.13 | 0.166 | 0.204 | |

| Logical Reasoning | AC (%) | 68.38 ± 24.08 | 69.76 ± 24.44 | 75.00 ± 23.39 | 74.31 ± 22.75 | 0.547 | 0.131 |

| RT (s) | 328.96 ± 114.14 | 325.42 ± 98.94 | 394.22 ± 155.28 | 324.46 ± 99.12 | <0.05 | 0.273 | |

| LP(AC/AT) | 0.23 ± 0.12 | 0.23 ± 0.10 | 0.21 ± 0.10 | 0.25 ± 0.11 | 0.573 | 0.127 |

| Satisfaction Rate (%) | Temperature Range (°C) |

|---|---|

| a > 94 | 22.5–25.6 |

| a > 90 | 20.6–27.6 |

| a > 85 | 19.1–28.9 |

| Learning Efficiency Range | Temperature Range |

|---|---|

| b > 85% | 18.5–22.2 °C |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ao, Y.; Liu, B.; Peng, P.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, B.; Martek, I. Impact of University Building Thermal Environments on Thermal Comfort and Learning Efficiency: A Study Under Conditions of Hot Summer and Cold Winter. Buildings 2026, 16, 598. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030598

Ao Y, Liu B, Peng P, Li M, Wang Y, Wang B, Martek I. Impact of University Building Thermal Environments on Thermal Comfort and Learning Efficiency: A Study Under Conditions of Hot Summer and Cold Winter. Buildings. 2026; 16(3):598. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030598

Chicago/Turabian StyleAo, Yibin, Bingjie Liu, Panyu Peng, Mingyang Li, Yan Wang, Bo Wang, and Igor Martek. 2026. "Impact of University Building Thermal Environments on Thermal Comfort and Learning Efficiency: A Study Under Conditions of Hot Summer and Cold Winter" Buildings 16, no. 3: 598. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030598

APA StyleAo, Y., Liu, B., Peng, P., Li, M., Wang, Y., Wang, B., & Martek, I. (2026). Impact of University Building Thermal Environments on Thermal Comfort and Learning Efficiency: A Study Under Conditions of Hot Summer and Cold Winter. Buildings, 16(3), 598. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030598