Abstract

The escalating housing crisis and the uncontrolled proliferation of informal settlements in the Global South challenge the modernist ideal of the completed architectural object. While ‘Parasitic Architecture’ is conventionally coded as an act of illegal occupation, ‘Incremental Housing’ strategies propose a controlled evolution; however, a theoretical gap exists in defining the morphological mechanics where these two concepts intersect. This study aims to bridge this gap by proposing the concept of ‘Domesticated Parasitism’. Adopting an instrumental case study model, the research analyzes the morphological evolution of the Quinta Monroy housing complex in Chile. To mitigate interpretive bias and ensure analytical objectivity, the visual reading follows a structured coding protocol that categorizes the intervention zones into three distinct layers: (1) Fixed Structural Matrix, (2) Defined Expansion Zones, and (3) User-Generated Infill. Findings from the diachronic analysis comparing the initial state with current saturation levels reveal that the host structure functions as a ‘spatial cage’ that disciplines the growth of user additions. Unlike uncontrolled urban sprawl, the visual evidence confirms that the parasitic additions strictly adhere to the vertical void geometry defined by the architect. The research concludes that the architect’s role transforms from an author of static forms to an enabler, positioning domesticated parasitism as a sustainable spatial grammar for urban densification.

1. Introduction

Historically, the discipline of architecture has been predicated on the ideal of completeness. According to the prevailing paradigm that extends from Modernist doctrine to the present day, an architectural work is perceived as a static object whose boundaries are delineated, functions are prescribed, and state is frozen the moment its construction is finalized. However, the rapidly escalating urban population of the 21st century, coupled with the deepening housing crisis in the Global South, has rendered this ideal of the finished object an unsustainable luxury. Conventional social housing models, which remain insufficient to meet the shelter needs of millions, alongside the parallel and uncontrolled proliferation of informal settlements on the urban peripheries, have brought the discipline of architecture to a radical crossroads. The question now stands: will the architect continue to attempt to design the city with absolute control, or will they share this authority with the user, thereby opening a space for uncertainty?

The formulation of the research problem is predicated on the theoretical tension between two dominant discourses in urbanization. Quantitatively, the magnitude of the crisis is underscored by the exponential rise in informal settlements in the Global South, a phenomenon described by Davis as a planet of slums [1]. Qualitatively, the study relies on the autonomy framework proposed by Turner [2] and supports the theory by Habraken [3], which argues that user participation is not a chaotic disruption but a fundamental requirement for housing. The specific research gap addressed herein emerges from the intersection of these views: while the theoretical necessity of user involvement is established in the literature, the specific morphological mechanics of how this involvement can be structurally disciplined within a host system remain underdefined.

At this critical crossroads, strategies of Incremental Housing, and most significantly the Half-House approach developed by Alejandro Aravena and Elemental, propose a paradigm shift that fundamentally shakes the foundations of architectural production. This approach conceptualizes architecture not as a finished commodity, but as an open-ended process that evolves over time through the active interventions of the user. Here, the architect renounces the role of constructing the complete structure; instead, the design effort focuses on establishing a strategic starting point onto which future additions can securely anchor themselves.

What is particularly intriguing is that this strategy of leaving unfinished precipitates an unforeseen outcome within the realm of urban morphology. The additions constructed through the user’s own means begin to behave formally in a manner akin to a parasite in the natural world. These additions, which cling to the existing structure, infiltrate the voids, and feed upon the host building, represent the very embodiment of the morphological reflexes typically coded in architectural literature as informal or illegal. Yet, within the context of these projects, the reflexes in question do not constitute an error or a violation. On the contrary, they function as a mechanism of growth that is both anticipated and actively encouraged by the design itself. Consequently, a previously undefined symbiotic collaboration emerges here between uncontrolled growth, which is one of the oldest fears of architecture, and design, which remains one of its most fundamental instruments.

1.1. Problem

In contemporary architectural and urban planning literature, Parasitic Architecture is predominantly defined as an act of occupation that challenges the boundaries of the existing urban fabric, violates established regulations, and typically evolves as an informal or unregistered phenomenon. Previous studies and developed morphological typologies have generally classified the relationship established between the parasite structures and the host as interventions that occur subsequently, remain unforeseen, and possess a contentious nature. Within this context, the parasite is coded as an external entity that either assaults the static integrity of the host or mechanically exploits it.

However, the escalating housing crisis in the Global South and the rise in Incremental Housing strategies, particularly the Half-House practices of Alejandro Aravena and the Elemental group, generate a paradoxical gap within these theoretical assumptions. In the approach of Aravena, the architectural product or the host is not conceived as a finished object but as an infrastructural base to be completed over time through the additions of the user, which function as the parasite. Here, the host structure does not reject or merely endure its parasite. Instead, it integrates this addition into the system by reserving specific structural voids for its accommodation.

The fundamental problem in the current literature is the absence of a theoretical bridge between the morphological mechanics of parasitic architecture and the strategic framework of incremental housing. While incremental housing literature generally discusses the subject through the perspectives of economic sustainability and participation, parasitic architecture literature interprets the subject primarily as informal occupation. In this context, the literature lacks a terminological foundation to define this hybrid mechanism that behaves formally like a parasite by wedging or clinging, yet is strategically tamed and legalized by the host.

This research interrogates how the traditional definition of the occupying parasite has evolved into a controlled model of Domesticated Parasitism. The research problem centers on how informal settlement dynamics are domesticated by the formal architectural structure and how the host–parasite relationship should be morphologically defined during the transition of the architect from the role of an author to that of an enabler providing infrastructure.

1.2. Purpose

The primary objective of this study is to theorize the concept of “Domesticated Parasitism” by reinterpreting the phenomenon of parasitic architecture through the lens of Incremental Housing strategies. While architectural literature typically codes this phenomenon as an uncontrolled, illicit, and destructive act, this research proposes a new reading. The study aims to analyze the Half-House approach of Alejandro Aravena and the Elemental group not merely as a socio-economic housing model but as a symbiotic morphological strategy constructed between the host and the parasitic addition. In this direction, the research seeks to construct a theoretical foundation wherein the parasitic action ceases to be a perceived threat and transforms into a domesticated and constructive design instrument. In this model, the boundaries are delineated by the architect and structural safety is assured, allowing the addition to complete the host. Consequently, the study offers an original conceptual framework to the literature by liberating parasitic architecture theory from the dichotomy of legality versus illegality and redefining it along the axis of mechanical dependency and symbiotic evolution.

1.3. Questions

This study seeks answers to three fundamental questions structured around ontological, morphological–mechanical, and methodological dimensions, respectively, to realize the aforementioned aim and ground the concept of Domesticated Parasitism.

RQ1: How is the host–parasite relationship, traditionally defined through conflict and occupation, reconstructed in Incremental Housing strategies on the axis of domestication and symbiotic collaboration?

RQ2: Through which structural dependency and prepared interface mechanics does the physical relationship operate between the Half House designed by the architect and the Addition constructed by the user?

RQ3: In this framework where the role of the architect is redefined as an enabler, what role do the parasitic additions produced by the user assume in the completion process of the architectural object?

1.4. Significance

The significance of this research resides in its construction of a previously unestablished theoretical and operational bridge between two distinct bodies of literature that have typically progressed in isolation within architectural discourse. These are the morphological narrative of Parasitic Architecture and the strategic framework of Incremental Housing. Whereas existing scholarship predominantly treats parasitic architecture as singular, provocative, and decontextualized artistic or political gestures, this study reframes the subject as a viable solution mechanism for addressing urgent and tangible challenges such as the global housing crisis.

The most distinct and original contribution this study offers to the literature is the concept of “Domesticated Parasitism” developed herein. Through this concept, the research liberates the parasitic phenomenon from its definition as a pathological infestation to be avoided and transforms it into a symbiotic production model that can be designed, managed, and actively encouraged.

Consequently, the study presents a concrete morphological grammar demonstrating how the spontaneous growth energy inherent in informal settlements can be absorbed by the structural infrastructure or host provided by formal architecture rather than being eradicated. This approach fundamentally transforms the role of the architect as well. The architect is no longer positioned as the creator of finished and static objects but assumes the elevated role of an enabler who orchestrates open-ended infrastructures to which parasitic additions can securely attach.

Ultimately, this research holds critical importance as it demonstrates through the practice of Alejandro Aravena that parasitic architecture is not merely a marginal act of occupation. Instead, it proves to be a morphologically defined and strategically planned model of urban densification capable of responding to the housing challenges of the Global South.

2. Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework of this study is predicated upon the synthesis of two fundamental paradigms that are typically treated as antithetical poles within the literature of architecture and urban design. On one side stands Parasitic Architecture, which serves as a symbol of informal urbanization and resistance, while on the other lies Incremental Housing, representing an institutional and planned housing strategy. At the intersection of these two domains, the study opens up for discussion a new ontological plane through the concept of “Domesticated Parasitism.” In this context, the parasite metaphor is transcended beyond its biological and political roots, transforming into an operational spatial grammar for urban densification and participatory design processes.

The disciplines of architecture and urban design exhibit a tendency to conceptualize the built environment as a static entity, one that is strictly delineated by precise boundaries and perceived as a completed whole. Within this traditional narrative, the ultimate objective of design is the production of an immutable order and a permanent form. However, Serres radically destabilizes this static understanding by elevating the concept of the parasite to a philosophical plane [4]. According to Serres, the parasite is not merely a passive consumer that exploits a system. Rather, it functions as a catalyst that enters the system as noise, interrupting its flow yet thereby enhancing the complexity and adaptive capacity of that very system. This perspective found its early expression within the architectural realm through the work of Ungers [5]. In his seminal work City Metaphors, Ungers defines parasitic architecture as an informal mode of organization that interprets the act of clinging to infrastructure as a fundamental survival instinct. Contemporary studies, such as those by Baroš and Katunský, revisit this approach within the framework of biomimetic design, emphasizing its potential to generate architectural diversity [6].

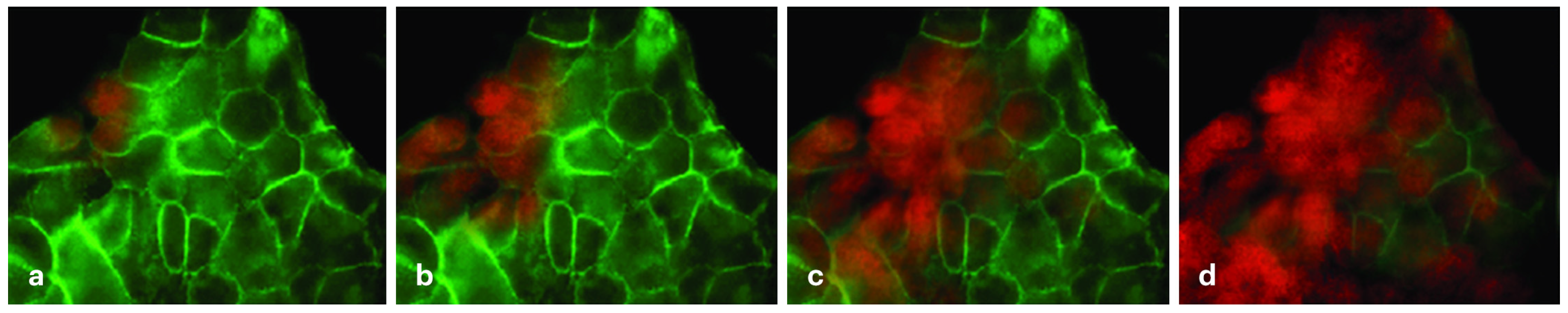

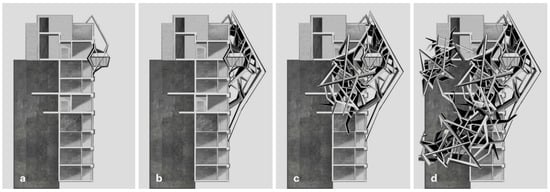

Current morphogenetic discourse focuses on the translation of these biological strategies into architectural practice. To comprehend the operational logic of parasitic structures, which are viewed as a speculative method attempting to maintain their presence amidst chaotic urban conditions, it is necessary to first focus on the survival strategies and evolutionary adaptation phases found within the biological realm (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The parasitic evolution and the process of host adaptation (Source: Illustrated by the authors). (a) Phase I: Intrusion; (b) Phase II: Invasion; (c) Phase III: Proliferation; (d) Phase IV: Dominance. In this representation, green indicates the host structure, while red indicates the parasitic invasion.

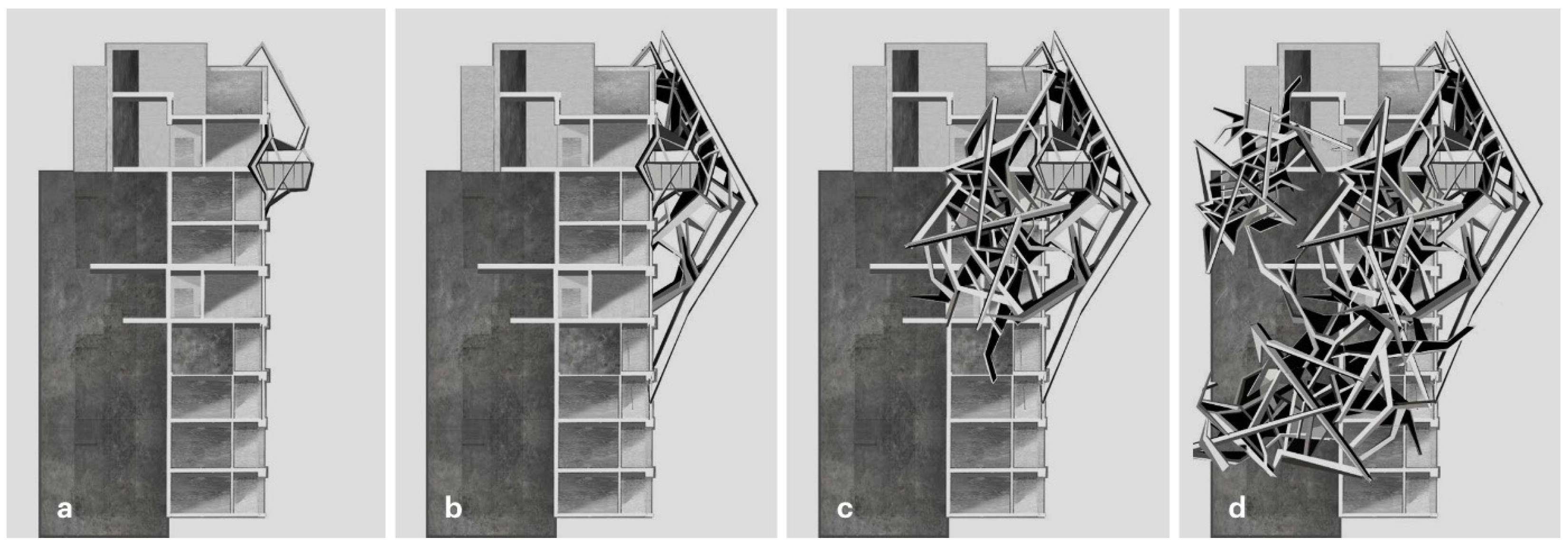

When transposed into the architectural domain, this process of biological adaptation finds a spatial counterpart. Parasitic design, referencing the ecological relationship between the parasite and the host, acquires a symbiotic significance at the architectural scale. In this context, the reflexes that enable the parasite to adapt to the host through an evolutionary process are transformed into structural and morphological actions (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The parasitic architecture and the process of host adaptation [7]. (a) Phase I: Intrusion; (b) Phase II: Invasion; (c) Phase III: Proliferation; (d) Phase IV: Dominance.

This philosophical and biological foundation found its counterpart in the architectural realm within the radical movements of the 1960s. By perceiving the city as a living organism rather than a finished composition, Archigram and the Japanese Metabolists established the technological infrastructure of parasitic logic through plug-in capsules attached to existing infrastructure. However, the concept underwent a definitive politicization through the radical reconstruction projects of Woods [8]. For Woods, the parasite constitutes an architecture of resistance in war-torn cities; it clings to the old while simultaneously rejecting its authority and regulations. In this context, the parasite is defined as an unpredictable and undisciplinable act of invasion that challenges the established hierarchy of the host fabric.

The fundamental deficiency within contemporary literature is that parasitic architecture continues to be discussed predominantly on this political and metaphorical plane and has not been systematized as a physical strategy of construction. Yet, parasitic additions do not emerge as arbitrary forms; rather, they are specific morphological responses to the physical constraints presented by the host. At this juncture, the study proposes to interpret parasitic interventions not merely as an addition or a stylistic anomaly, but through the lens of a strategy of spatial completion and disciplined infill pre-configured by the architect. This approach constitutes an operational language defining not the haphazard attachment of the addition to the host, but how it integrates into the structural matrix allocated to it and how it advances the structure toward its final form.

The reflexes of subsequent attachment and growth over time inherent in these morphological actions establish a robust ontological affinity with Incremental Housing strategies in residential literature, thereby constructing a novel platform for discourse. Within this context, Incremental Housing defines the dwelling not as a static object but as a dynamic process that evolves concurrently with the financial capacity and socio-cultural necessities of the household. The insufficiency of mortgage systems in developing nations compels low-income groups toward an informal invasion of urban space [9]. However, the half-house approach of the Elemental group transforms this parasitic action from a perceived threat into a design instrument where boundaries are delineated and structural safety is assured by the architect [10]. The physical improvements realized by residents through the method of sweat equity convert this unilateral dependency over time into an organic urban symbiosis. Consequently, the dwelling ceases to be a static shelter and evolves into a living organism that derives its social legitimacy from its own developmental process [11].

Turner similarly posits that housing should be conceptualized not as a noun denoting an object but as a verb representing a process [2]. He asserts that the autonomy of the user to construct their own living environment is an indispensable prerequisite for achieving both economic and social sustainability. This perspective advocated by Turner establishes a structural foundation through the Supports theory developed by Habraken [3]. Habraken emphasizes that the primary responsibility of the architect is not to finalize the building. Instead, the architect must provide an infrastructural framework or support which the user can inhabit, transform, and personalize over the course of time. In this context, the dwelling transforms into a dynamic organism composed of distinct layers such as structure, services, skin, and plan that evolve at varying velocities, as articulated in the Shearing Layers theory of Brand [12]. Conversely, the Modernist paradigm exhibits a tendency to perceive the dwelling as a static and finalized commodity. Challenging this prevailing notion, Schneider and Till advance the concept of Flexible Housing and position the principle of indeterminacy at the very center of the design process [13]. According to their argument, architecture should not attempt to predict future alterations. Rather, it must define the soft and hard zones that will accommodate and facilitate these inevitable changes.

Within this theoretical continuity, the Half-House strategy of the Elemental group transforms the Supports concept of Habraken into a concrete construction protocol. It evolves into a model where the architect, rather than dictating the final form, designs an open-ended structural matrix to be completed over time through the actions of the user. In the evolutionary process of incremental housing, Participatory Design (PD) serves as the fundamental dialectical instrument that transports the initial character of invasion to a stage of symbiosis compatible with the system. Contrary to traditional design processes, this approach positions mutual learning and empowerment at its center, thereby removing the user from the position of a passive object of design and establishing them as the primary subject of the process [14]. Overcoming the mechanical dependency observed in the visuals is made possible through the practices of located accountabilities and design-by-doing offered by PD [15]. Participatory processes balance power relations by breaking the cognitive domination of experts and present a strategy of symbiotic evolution that transforms the tension between the parasite and the host into an ethical and political realm of liberation [16]. Consequently, parasitism domesticated through participatory design becomes not an element that weakens the urban fabric but the nodal point of a sustainable urban symbiosis where the community acts as the agent of its own transformation [17].

This study synthesizes the two discussed lines of literature, namely Operational Parasite Morphology and Incremental Housing Theory, to propose the concept of Domesticated Parasitism for defining this new mode of production. Traditional parasitic architecture, such as squatting or activist interventions, typically manifests as a wild process of invasion that develops without the consent of the host, violates property boundaries, and threatens structural integrity. Conversely, within the proposed model, this relationship evolves into a strategic symbiosis pre-configured by the architect. In the Domesticated Parasitism model, the architect does not design how the parasite or the user addition will appear visually. Instead, the architect constructs a spatial cage that determines exactly where and according to which rules the addition can attach itself.

At this point, morphological actions within the parasitic architecture literature regain function as a design strategy. Rather than appearing as uncontrolled interventions, these actions are redefined under the framework of Domesticated Parasitism. This concept emerges as a hybrid production model, much like the Remodeling theory described by Machado [18]. It transforms the past by adding a new layer onto it, yet it remains faithful to the rules of the host, including infrastructure, structure, and regulations. In this model, parasitism is not a state of urban crime or disorder. Instead, it is a growth mechanism domesticated by the architect and integrated into the system to make urban densification and housing provision sustainable.

3. Materials and Methods

The research program is grounded in a qualitative–interpretive framework regarding the spatial dynamics of habitation. Phenomenologically, the study approaches the housing unit not as a static finished object, but as a dynamic lived space that evolves through the residents’ daily needs and interventions. In this view, the tension between the architect’s designed order and the user’s spontaneous adaptation is not a defect, but the core subject of the inquiry. Within this context, visual analysis functions as a hermeneutic tool to read these adaptations. Specifically, the method isolates the physical additions made by residents to analyze their relationship with the original structure. Through this examination, the study seeks to understand how the user-initiated additions integrate with the formal architecture, thereby offering a morphological reading of this symbiotic coexistence.

The current section operationalizes this research program by comprehensively presenting the methodological framework adopted to answer the research questions (RQs). The method section is structured around the research model that guided the study’s design, the selection process and justification for the dataset, or corpus, included in the analysis, the data collection procedures employed, and the data analysis strategy utilized to synthesize the findings. The research is based entirely on publicly available and open-access secondary sources. At all stages of the research, the principles of scientific research and publication ethics were rigorously adhered to, particularly regarding the transparent and accurate citation of all references used.

3.1. Model

This study is designed as an instrumental case study situated within the framework of qualitative research methods. In accordance with the methodological distinction established by Stake [19], the instrumental case study model is adopted because the selected case is utilized not merely to comprehend its own idiosyncrasies but as a vehicle to elucidate and substantiate a broader phenomenon or theoretical concept, which is Domesticated Parasitism in this context. Rather than seeking causal or statistical correlations, the research adopts an interpretive approach. This aligns with the perspective of Yin [20], who argues that case studies are essential for investigating complex phenomena where the boundaries between the phenomenon and its context are not clearly evident.

3.2. Sample

The sample of the research was determined using the Criterion Sampling method, which is a specific technique within the broader category of Purposive Sampling. As articulated by Patton [21], this sampling strategy is particularly rigorous for qualitative inquiry as it involves selecting cases that meet some predetermined criterion of importance, thereby ensuring that the selected case is information-rich regarding the central issues of the study.

Within this methodological scope, the selection of the case was predicated upon three fundamental criteria. The first criterion is Morphological Intent, which necessitates that the project possesses a structural configuration or host that was intentionally left half or incomplete by the architect. The second criterion is Processual Documentation, which requires the accessibility of visual data such as photographs and drawings documenting the transformation between the initial moment of construction and the subsequent stages where user interventions are finalized. The third criterion is Typological Representation, which demands that the project clearly exemplifies the structural void and infill strategy that constitutes the core mechanics of the proposed Domesticated Parasitism model.

In strict accordance with these criteria, the Quinta Monroy housing complex (2004, Chile), designed by the Elemental group, was selected as the singular sample of the research. Recognized as the canonical pioneer of the Incremental Housing literature and the initial prototype of this specific typological approach, Quinta Monroy provides the most lucid and observable data for analyzing the transition from a designed void to a user-generated completion.

3.3. Data Collection

The data corpus of the research is constituted not by fieldwork based on primary sources but by secondary sources obtained through a systematic document review method. The dataset is compiled from official architectural drawings, including plans, sections, diagrams, and project reports published by the Elemental office, alongside high-resolution photographic records located in international digital architectural archives that document the transformation of the structures in question over time.

During the data collection process, a specific emphasis was placed on diachronic datasets. In this context, a visual inventory was established by matching photographs taken during the initial year of construction with those captured in subsequent periods. This comparative approach enables the monitoring of the morphological evolution of the parasitic addition.

3.4. Data Analysis

The visual and graphic data obtained were analyzed using the Morphological Content Analysis technique. This analysis was conducted through a three-stage deconstruction process aimed at testing the proposed Domesticated Parasitism theory. To control potential interpretive bias and ensure the reproducibility of the visual reading, a strict Morphological Coding Protocol was implemented. This protocol classifies visual data into three verifiable categories derived from the theoretical framework rather than subjective observation: (1) Fixed Structural Matrix (Host), (2) Defined Expansion Zones (Void), and (3) User-Generated Infill (Parasite) (Table 1).

Table 1.

The Morphological Coding Protocol utilized in the study.

This categorization provides a systematic basis for distinguishing between the architect’s intent and the user’s intervention, thereby securing the internal validity of the qualitative inferences.

The process begins with the first stage, Deconstructing the Host, which involves the identification of fixed components designed by the architect, such as the structural framework, wet cores, and infrastructure, and the analysis of how these components constitute a plinth for the parasite. Following this, the second stage, Defining the Void, focuses on analyzing the geometric boundaries, growth potential, and structural rules of the void reserved for the parasitic addition. The process concludes with the third stage, Reading the Parasite, which entails the identification of the materials, construction techniques, and modes of attachment to the host of the additions constructed by the user over time.

Throughout the analysis process, graphical encodings applied to the section and elevation drawings of the structures were utilized to concretize the interface between the formal boundary designed by the architect and the informal infill produced by the user.

4. Results

Before presenting the specific morphological readings, it is important to clarify that in this analysis, the term ‘architect’s intent’ refers strictly to the fixed attributes of the structural host matrix, while ‘user intervention’ defines the variable geometry of the parasitic infill. Therefore, the study evaluates the physical interface between these two distinct morpho-genetic layers, rather than the subjective motivations or socio-economic constraints behind them. Consequently, conceptual labels such as ‘symbiosis’ are assigned based on the observable structural alignment between the provided matrix and the inhabited void, treating the resulting form as a measurable morphological fact.

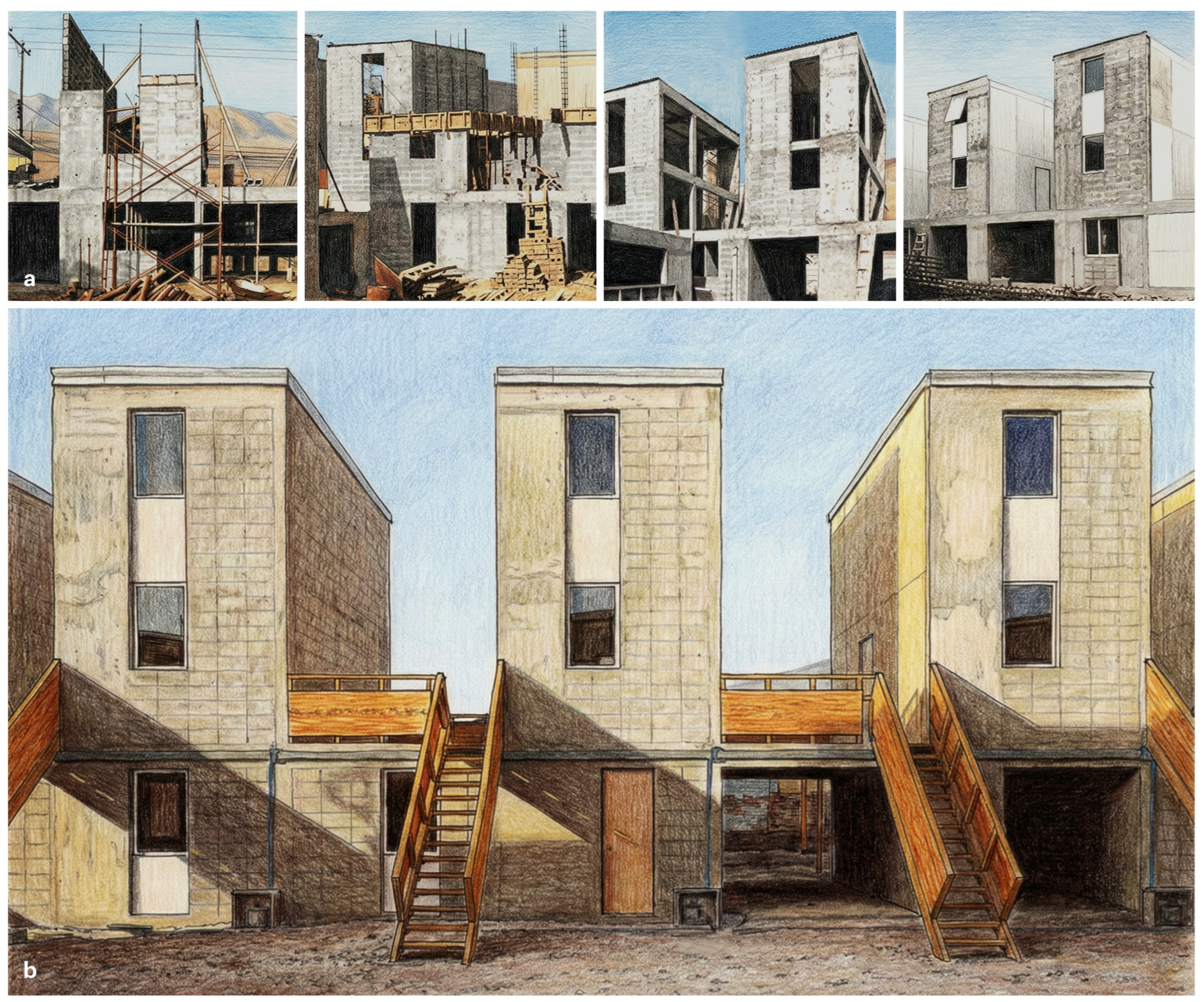

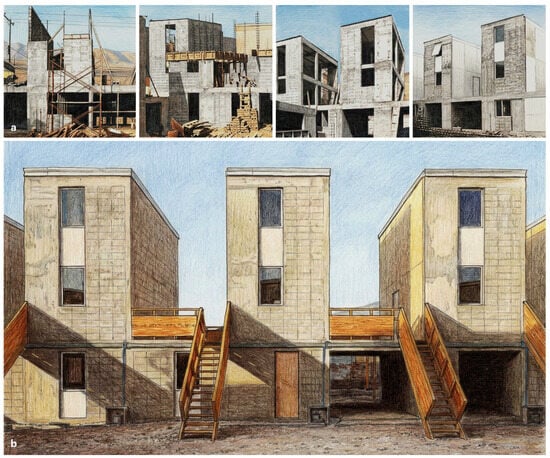

The morphological analyses conducted on the Quinta Monroy settlement within the scope of this study reveal how the wild and informal nature of parasitic architecture undergoes a strategic domestication process through architectural design. In this context, rather than dictating the final form of the structure, the architect designed an open-ended structural matrix intended to be completed over time through the actions of the user (Figure 3). This strategic approach provides a clear answer to the first research question (RQ1) and demonstrates that the host–parasite relationship, conventionally coded as conflict and occupation, is reconstructed in the Incremental Housing model on an axis of symbiotic collaboration and conscious domestication.

Figure 3.

The genesis of the host structure. (a) Construction stage of the fixed structural skeleton encoded by the architect as the DNA [22]. (b) Raw initial state of the Half House delivered to the user before intervention [23]. (Redrawn by the authors based on [22,23]).

The analysis process initially identified a transformation in the ontological definition of the host structure. As evidenced by the construction photographs in Figure 3, the initial reinforced concrete core constructed at Quinta Monroy serves as more than a passive unit merely satisfying the need for shelter. This structure functions as an active regulatory device transforming the core into a parasitic interface.

The exposed concrete framework of the host acts as a political demarcation of property lines and a technical guarantee for seismic safety, ultimately providing a clinging surface for future parasitic additions. Rather than designing the entire building, the architect encoded the DNA of the structure, including its envelope, rhythm, and void ratios, through this host and thereby secured control over the process from the very beginning (Figure 4).

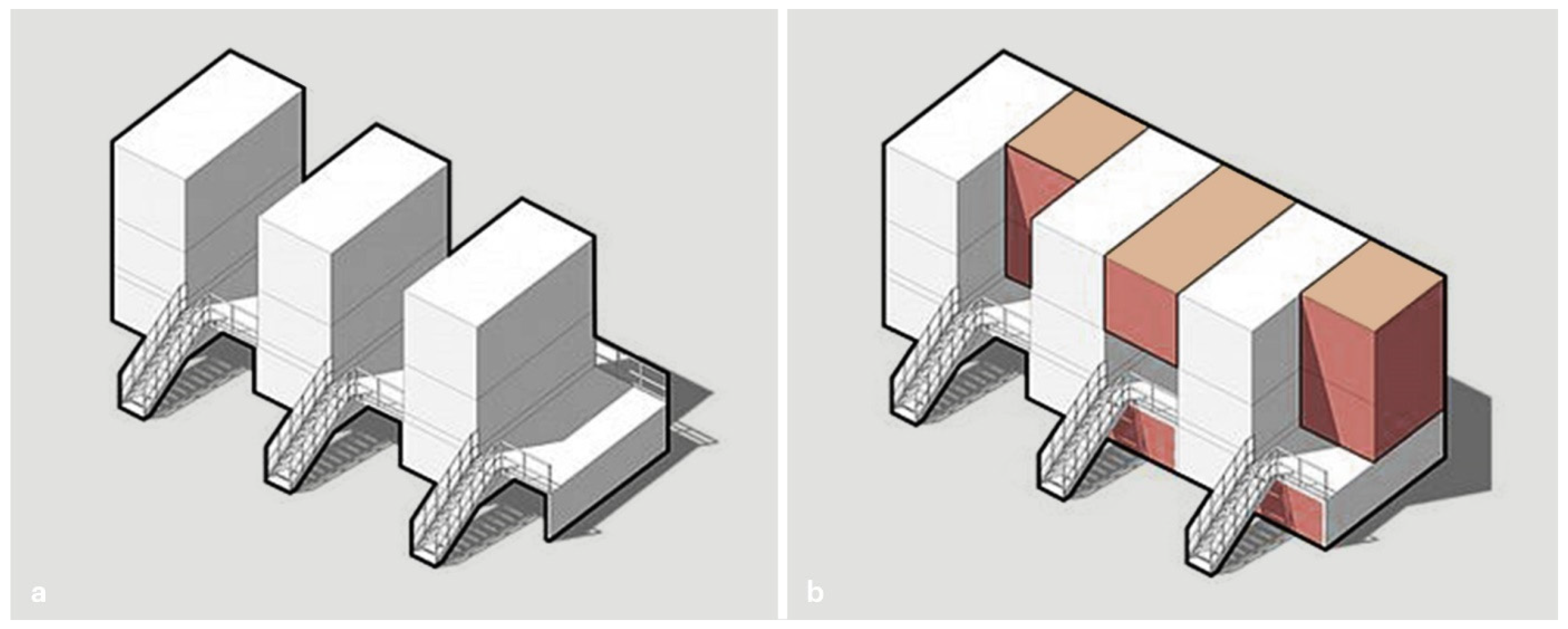

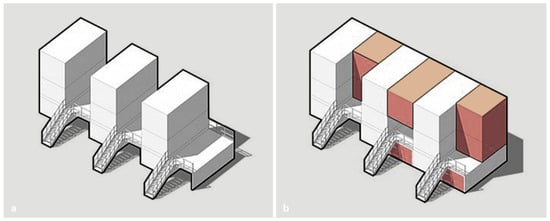

Figure 4.

Operational scheme of the Domesticated Parasitism model [24]. (a) The structural framework provided by the host and the defined void reserved for the parasite. (b) The act of domesticated parasitism emerging from the filling of this void through user initiative. (Redrawn by the authors based on [24]).

The diagrammatic analysis presented in Figure 4 concretizes the operational logic of the Half House strategy. Represented in white within the left diagram, the host functions not merely as a housing unit but also as a template defining property boundaries in a vertical dimension. Conversely, the diagram on the right illustrates the wedging action executed by the user as they infiltrate this template.

A notable aspect of this process is that the form of the parasitic addition, depicted as red masses, is dictated entirely by the geometry of the void intentionally left by the architect. Consequently, the architect did not design the solid but rather ensured the final form of the infill by meticulously designing the void. This mechanism effectively prevents the parasitic addition from exhibiting wild growth, converting it instead into an act of domesticated parasitism that aligns with the established structural rhythm.

As indicated by this visual reading, the most critical component of the system is not the built portions but, paradoxically, the unbuilt voids. Here, the void functions as a spatial cage with boundaries clearly delineated by the architect and defined by floor levels and roof eaves. Consequently, the geometry of the void prevents the parasitic addition from expanding horizontally and compels it to grow vertically by wedging between two blind walls (Figure 5).

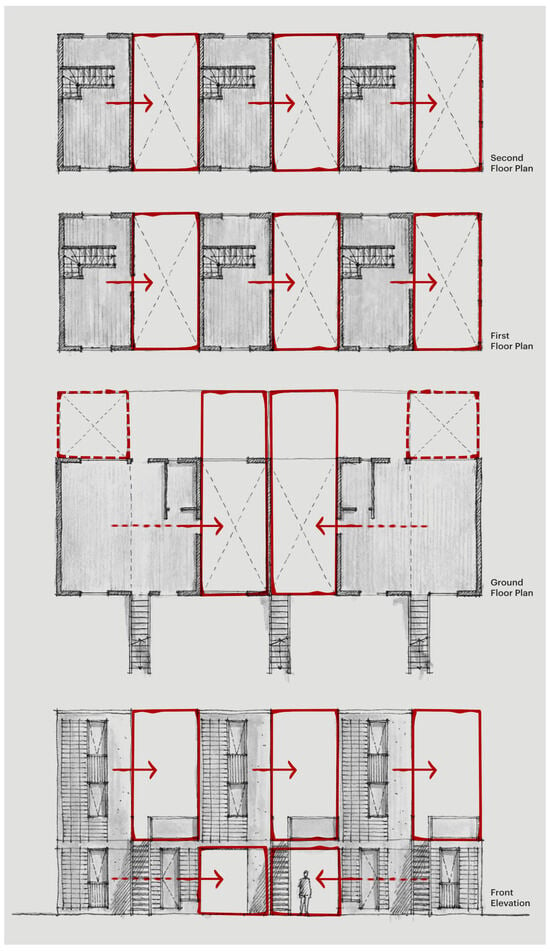

Figure 5.

Technical analysis illustrating the defined void reserved by the host structure for the parasite and the corresponding growth boundaries (Source: Illustrated by the authors).

The plan and elevation analysis presented in Figure 5 clearly articulates the architectural codes underlying this constraint. Observations from the ground floor and upper floor plans indicate that the void allocated for the parasitic addition is structurally encompassed by the utility core of the host structure and the blind walls located at the neighboring plot boundaries. The red boundaries depicted in the visual representation symbolize the rigid physical limits to which the parasite can adhere but which it cannot transcend.

Through this technical configuration, the growth vector acquires the character of a centripetal infill that adheres to the center and vertical axis rather than the centrifugal sprawl typically observed in informal settlements. The boundaries delineated by the architect do not eliminate user initiative but rather compel it to remain within the confines of structural safety and urban order. These morphological findings constitute the response to the second research question (RQ2) by demonstrating that the physical relationship between the host designed by the architect and the parasite constructed by the user is not a random articulation. Instead, it is constructed through a prepared interface defined by blind walls and utility cores as well as a mechanism of structural dependency.

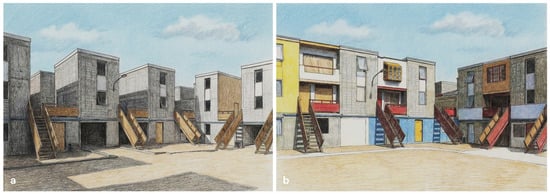

Diachronic data reveal how users have filled these voids over time (Figure 6). This analysis, comparing occupancy rates of Quinta Monroy in 2004 and 2017, demonstrates that parasitic additions have created significant morphological saturation by filling not only the vertical voids allocated to them but also the residual spaces in the backyards, as observed in 30 out of 34 households.

Figure 6.

Diachronic analysis of the transformation within the Quinta Monroy [25]. (a) Handover condition in 2004 with high porosity. (b) Current state in 2017 with morphological saturation. (Redrawn by the authors based on [25]).

As clearly demonstrated by the black-and-white contrast in Figure 6, parasitic additions have nearly eliminated the porosity of the settlement and established a solid texture. However, a critical detail emerges in that while the growth in the backyards expands like an amorphous stain, the alignment along the street facade persists in maintaining the strict order delineated by the architect. This observation visually validates that the Domesticated Parasitism model facilitates densification without compromising the integrity of the urban silhouette.

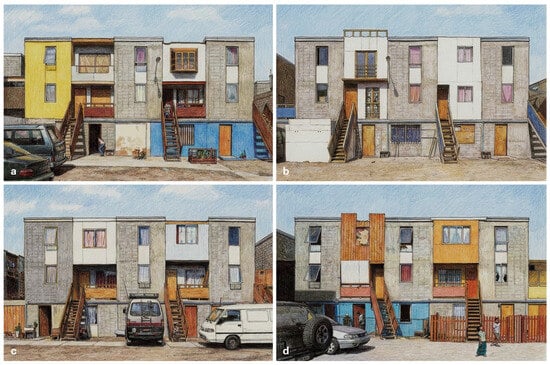

The visual transformation presented in Figure 7 further confirms that the additions produced by the user utilize the infrastructural possibilities offered by the host to push the boundaries of the structure while simultaneously exhibiting complete submission to its structural rules.

Figure 7.

Diachronic comparison of the transformation within the Quinta Monroy. (a) Handover condition in 2004 [26]. (b) Current state in 2024 [27]. (Redrawn by the authors based on [26,27]).

The volumetric growth process observed in Figure 7 has evolved into a differentiated facade formation. As users fill the neutral frame provided by the architect according to their own socioeconomic realities, a non-uniform, heterogeneous, and multi-layered facade character has emerged (Figure 8). These morphological findings provide the answer to the third research question (RQ3) by visually demonstrating the variations generated by user interventions.

Figure 8.

Unique facade variations generated by users according to their socioeconomic means and aesthetic preferences. (a) [28]; (b) [29]; (c) [30]; (d) [31]. (Redrawn by the authors based on [28,29,30,31]).

When examined tectonically, the photographic data in Figure 8 reveals a diversity created by heterogeneous materials such as wood, brick, and metal. Furthermore, the specific detail point where the user’s brick wall joins the architect’s concrete column serves as the physical interface of this integration (Figure 9).

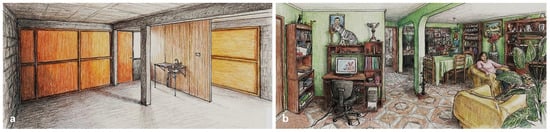

Figure 9.

Transformation of the interior space of Quinta Monroy [32]. (a) The bare structural shell and utility wall delivered by the architect. (b) The living space personalized after being transferred to user ownership. (Redrawn by the authors based on [32]).

When descending to the interior scale, which constitutes the final stage of the morphological analysis (Figure 9), the visual data presents a dichotomy. In the image on the left, the naked potential offered by the architect presents an industrial infrastructure characterized by exposed concrete columns, plywood dividers, and exposed utility elements. Conversely, in the image on the right, the user has transformed this industrial shell through the use of paint, furniture, personal objects, and floor coverings. In terms of resource usage, a material division is observed: the architect constructed the heavy, permanent elements with a high carbon footprint, such as reinforced concrete and infrastructure, while the user built the light, flexible elements using wood, brick, or steel.

5. Discussion

The morphological evidence presented in the previous section allows for a theoretical reconstruction of the host–parasite relationship, moving beyond visual analysis to a discussion on urban strategy and architectural epistemology. The multi-layered examination demonstrates that the findings morphologically validate the thesis proposed by Pratama et al. [33]. Their argument suggests that parasitic structures are not destructive elements within the urban fabric but can instead serve as strategic instruments for sustainable resource management and urban densification. Furthermore, the Half House strategy challenges the modernist paradigm that views housing as a static and completed object. It converts the principle of indeterminacy, defined in the Flexible Housing literature by Schneider and Till [13], into a concrete construction protocol.

From a structural perspective, the findings indicate that the active regulatory function of the host aligns with the Supports theory proposed by Habraken [3]. However, a critical distinction emerges regarding the nature of the intervention. While McGuirk characterizes such interventions in Latin American cities as activist architecture, the findings of this study indicate that the host structure establishes a mechanism of strict morphological control rather than activism [34].

In this specific model, the function of the void diverges significantly from the ambiguity advocated in Sennett’s Open City concept [35]. Unlike an undefined opening, the void here operates as a disciplined spatial cage. Although Boano and Vergara-Perucich criticize this model as a management tool of neoliberal policies that shifts responsibility to the user [36], from a morphological perspective, this strategy constitutes the foundation of the Domesticated Parasitism model. Furthermore, the growth reflex observed in traditional informal settlements and described as sprawl by Davis [1] has been effectively disciplined in this project through these defined voids.

Regarding the horizontal growth observed in the backyards, a divergence in interpretation arises. While Carrasco and O’Brien describe this expansion as unplanned in their research [25], the findings of this study suggest reading it not as a systemic error but as a disciplined sprawl impulse. Even in this state of saturation, the growth remains governed by the plot boundaries initially defined by the host.

The resulting densification process strongly supports the proposal by Given to reclassify parasitic structures as active agents of urban sprawl rather than passive additions [37]. Furthermore, the findings elevate the discussion by Roy regarding the epistemology of informality to a new dimension where informality serves as the complement of formality rather than its opposite [38]. Consequently, the principle of autonomy described by Turner assumes a parasitic morphology here and evolves into an economic model in which the user acts as both a resident and a builder [2].

Beyond the quantitative gain in space, the transformation represents a qualitative process of identity construction. In this new production model where the architect shares authority, parasitic additions cease to be secondary patches appended to the structure and instead assume the role of an essential and founding component in the process by which the architectural object achieves its final form and function. This shift in authority and morphological control fundamentally separates the theorized concept from traditional squatter dynamics. As conceptualized in Table 2, Domesticated Parasitism redefines the governance, spatial order, and urban status of informal growth.

Table 2.

Conceptual comparison between Informal Parasitism and Domesticated Parasitism.

This conceptual redefinition also manifests itself in the physical realm. From a tectonic standpoint, the resulting material diversity should not be read as an aesthetic failure or disorder. On the contrary, this situation is a contemporary and living interpretation of the hybrid aesthetic in Venturi’s Complexity and Contradiction theory [39]. This unity between the exposed concrete language of the host structure and the bricolage aesthetic of the parasitic addition is the concrete manifestation of the mechanical balance established between the control of the architect and the initiative of the user. Consequently, the tectonic junction where the formal and informal elements meet marks the moment where the distinction usually seen as a conflict zone in the literature is erased.

At the interior scale, the concept of Domesticated Parasitism transforms into a spatial act of appropriation. The critical point here is that the structural boundaries designed by the architect do not restrict the freedom of the user but rather offer a clear framework. Consequently, the parasitic action functions not as a destructive force but as a layer that humanizes the space. The ecological and economic dimensions of this symbiotic relationship also parallel current sustainability discussions. Plevoets and Van Cleempoel emphasize that articulations made to the existing building stock, known as adaptive reuse, prevent embodied energy loss [40]. Similarly, Mehaffy and Salingaros state that urban resilience can only be achieved through such processes of adaptive morphogenesis [41]. In the case of Quinta Monroy, a radical optimization in resource usage was achieved, extending the lifespan of the existing infrastructure. This demonstrates that the proposed Domesticated Parasitism model is not merely a formal fantasy but a sustainable resource management strategy for the Global South.

Ultimately, the proposed concept of Domesticated Parasitism is constructed not on the specific stylistic or material choices of the Quinta Monroy project, but on the operational syntax established between the Host and the Void. While the empirical evidence is derived from a singular case study within the Latin American context, the transition from conflict to symbiosis claimed herein is not a case-specific anomaly but a transferable structural mechanism. The definition of the defined void as a regulatory apparatus offers a universal morphological grammar that can be adapted to different regulatory regimes and incremental typologies across the Global South, transcending the specific architectural language of the Elemental group. Although the specific lightweight materials (wood/metal) observed in Quinta Monroy are responses to the arid climatic and seismic conditions of Iquique, the operational syntax of the ‘Structural Matrix’ is adaptable to different economic-technical conditions. For instance, this strategy can be projected to geographies like Türkiye or India, where informal additions are typically constructed with heavier materials like brick or reinforced concrete. In such contexts, the ‘spatial cage’ provided by the host simply needs to be dimensioned to support the local vernacular load, proving that Domesticated Parasitism is not a stylistic choice but a scalable methodology for the Global South. In this framework, the shift from conflict to symbiosis is theoretically accounted for by the capacity of the structural matrix to absorb informal growth within prenegotiated boundaries, regardless of the specific geographic or cultural setting.

In parallel with this operational syntax, it is critical to distinguish between the parasite as a biological metaphor and Domesticated Parasitism as an operational design mechanism. While Serres’ philosophy provides the epistemological background for the intruder, this study operationalizes the concept by translating the biological ‘host’ into the ‘structural matrix’ and the ‘parasite’ into the ‘infill unit’. Thus, the term ceases to be a mere semantic analogy and functions as a tangible morphological syntax defined by specific attachment rules and void geometries.

6. Conclusions

The research has repositioned the phenomenon of parasitic architecture, which has long been coded in architectural literature as a zone of conflict, as a strategic production method for solving the global housing crisis. The morphological analyses conducted on the Quinta Monroy settlement confirm that ‘Domesticated Parasitism’ is not merely a theoretical abstraction but a measurable spatial grammar. Quantitative evidence from the diachronic analysis reveals that the defined voids have successfully absorbed the growth pressure, with parasitic additions achieving morphological saturation in 30 out of 34 households while strictly adhering to the vertical boundaries set by the ‘Structural Matrix’. This finding demonstrates that informal growth dynamics can be disciplined through architectural design rather than eradication.

The most critical scientific result of the study is the redefinition of the architect’s ontological position. The findings demonstrate that the architect transforms from an ‘author’ dictating static forms into an ‘enabler’ providing resilient infrastructure. In this framework, the ‘void’ functions as an active regulatory device rather than a passive emptiness. Consequently, the study offers three distinct contributions to the literature: (1) transforming Incremental Housing from a financial model into a morphological discipline; (2) evolving Participatory Design from idea exchange to active construction; and (3) redefining Urban Densification as a vertical, pre-planned strategy rather than horizontal sprawl.

Regarding the prospects for applied development, three limitations of this study point to future research directions. First, since this study relies on visual morphology, future research must corroborate these findings with structural performance tests to verify the load-bearing capacity of user-generated additions. Second, the sustainability of the model should be quantified through embedded energy analyses in future studies. Third, and most critically, the contextual validity of the model requires legal adaptation. As discussed, while the structural syntax is transferable to geographies like Türkiye or India, existing zoning regulations in these regions often prohibit such flexibility. Therefore, in countries with high earthquake risks and dense informal settlements, it is mandatory to develop new legal frameworks defining the ownership of the void beyond architectural design for this system to be applicable. Ultimately, this research underscores that the future of housing in the Global South lies not in finished objects, but in symbiotic systems that integrate user energy into the design equation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T. and N.Y.; Methodology, A.T. and N.Y.; Validation, A.T. and N.Y.; Formal analysis, A.T. and N.Y.; Investigation, A.T. and N.Y.; Resources, A.T. and N.Y.; Data curation, A.T. and N.Y.; Writing—original draft, A.T. and N.Y.; Writing—review & editing, A.T. and N.Y.; Visualization, A.T. and N.Y.; Supervision, A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the authors.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Davis, M. Planet of Slums; Verso: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.F.C. Housing by People: Towards Autonomy in Building Environments; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Habraken, N.J. Supports: An Alternative to Mass Housing; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Serres, M. The Parasite; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ungers, O.M. City Metaphors; Walther Konig Verlag: Köln, Germany, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Baroš, T.; Katunský, D. Parasitic Architecture. J. Civ. Eng. 2020, 15, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomigalova, M. Parasitic Architecture: A Embodiment of Dystopia. Ph.D. Dissertation, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, L. Radical Reconstruction; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, B.; Navarrete, J. A financial framework for reducing slums: Lessons from experience in Latin America. Environ. Urban. 2003, 15, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravena, A.; Iacobelli, A. Elemental: Incremental Housing and Participatory Design Manual; Hatje Cantz: Ostfildern, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Olagunju, R.E.; Atamewan, E.E. Incremental construction for sustainable low-income. J. Sustain. Archit. Civ. Eng. 2017, 19, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S. How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They’re Built; Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, T.; Till, J. Flexible Housing; Architectural Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen, J.; Robertson, T. (Eds.) Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ehn, P. Participation in design things. In Proceedings of the Participatory Design Conference (PDC), Bloomington, IN, USA, 1–4 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bossen, C.; Dindler, C.; Iversen, O.S. Evaluation in participatory design: A literature survey. In Proceedings of the 14th Participatory Design Conference (PDC), Aarhus, Denmark, 15–19 August 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Noorloos, F.; Cirolia, L.R.; Friendly, A.; Jukur, S.; Schramm, S.; Steel, G.; Valenzuela, L. Incremental housing as a node for intersecting flows of city-making: Rethinking the housing shortage in the global South. Environ. Urban. 2020, 32, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, R. Old buildings as palimpsest. Towards a theory of remodeling. Progress. Archit. 1976, 11, 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Viva, A. Quinta Monroy Housing, Iquique. Available online: https://arquitecturaviva.com/works/viviendas-quinta-monroy-1 (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Bostjan. Quinta Monroy. Architectuul. 2017. Available online: https://architectuul.com/architecture/quinta-monroy (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Inspireli. Scalable Housing: The Scalable Typical Unit at Vertical Housing for a Changing Society. Inspireli Awards. Available online: https://www.inspireli.com/en/awards/detail/5940 (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Carrasco, S.; O’Brien, D. Beyond the freedom to build: Long-term outcomes of Elemental’s incremental housing in Quinta Monroy. Rev. Bras. Gestão Urbana 2021, 13, e20200001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalocha, T. Quinta Monroy Housing Project. Elemental. Available online: https://www.elementalchile.cl/works/iquique-violeta-parra-ex-quinta-monroy (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Palma, C. Quinta Monroy Housing Project. Elemental. Available online: https://www.elementalchile.cl/works/iquique-violeta-parra-ex-quinta-monroy (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Elemental. Quinta Monroy Housing. Area. 2014. Available online: https://www.area-arch.it/en/quinta-monroy-housing/ (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Cidade, S. Pequenas Moradias: Uma Alternativa Para Atender às Novas Configurações Familiares. 2023. Available online: https://somoscidade.com.br/2023/12/21/pequenas-moradias-uma-alternativa-para-atender-as-novas-configuracoes-familiares/ (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Maganga, M. The Commons: Dissecting Open-Source Design. ArchDaily. 2022. Available online: https://www.archdaily.com/980865/the-commons-dissecting-open-source-design (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Chow, V. Justin McGuirk’s Radical Cities Is Released in the U.S. Today, Following the Author’s Op-Ed in Al Jazeera. Verso. 2014. Available online: https://www.versobooks.com/en-gb/blogs/news/1616-justin-mcguirk-s-radical-cities-is-released-in-the-u-s-today-following-the-author-s-op-ed-in-al-jazeera (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Mangukiya, J. Quinta Monroy Housing Project by Alejandro Aravena: The Need for Simplicity. Rethinking the Future. Available online: https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/case-studies/a4832-quinta-monroy-housing-project-by-alejandro-aravena-the-need-for-simplicity/ (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Pratama, P.P.; Hayati, A.; Dinapradipta, A. Parasitic Architecture and the Conversion of Abandoned Buildings into Green Open Space. Space 2023, 10, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuirk, J. Radical Cities: Across Latin America in Search of a New Architecture; Verso: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sennett, R. Building and Dwelling: Ethics for the City; Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Boano, C.; Vergara Perucich, F. Half-happy architecture. Viceversa 2016, 4, 58–81. [Google Scholar]

- Given, D. Developing parasitic architecture as a tool for propagation within cities. J. Archit. Urban. 2021, 45, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A. Urban informality: Toward an epistemology of planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2005, 71, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturi, R. Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture; The Museum of Modern Art: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Plevoets, B.; Van Cleempoel, K. Adaptive reuse as a strategy towards conservation of cultural heritage: A literature review. In Structural Studies, Repairs and Maintenance of Heritage Architecture XII.; WIT Press: Southampton, UK, 2011; Volume 118, pp. 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehaffy, M.; Salingaros, N.A. Design for a Living Planet: Settlement, Science, and the Human Future; Sustasis Foundation: Portland, OR, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.