Abstract

Classroom acoustic conditions significantly affect students’ learning outcomes and teachers’ occupational health, yet a systematic gap persists between optimal acoustic standards established in research and their implementation in practice. Although peer-reviewed literature has defined performance thresholds, guidance on which design strategies effectively achieve these targets across different school spaces remains limited. Grey literature—project documentation from architectural firms, acoustic consultants, and material suppliers—contains valuable practice-based evidence. This study aimed to map practice-based evidence in K–12 school acoustic design, identify dominant space–strategy patterns, and appraise evidence quality through systematic mapping of grey literature. Following PRISMA-ScR guidelines, systematic searches were conducted across 27 websites representing three source types, yielding 142 projects from 22 countries. Data extraction employed a standardised coding framework encompassing project metadata, 19 space types, and 16 acoustic strategy subcategories within five major categories. Evidence quality was assessed using a quantified AACODS framework (score range 6–30), with inter-rater reliability (ICC = 0.989). The evidence landscape revealed geographic concentration in North America (41.5%) and the Asia–Pacific region (26.8%), with architectural firms contributing most documentation (54.2%). Space–strategy analysis identified dominant patterns: classrooms and corridors primarily employed absorptive ceilings combined with wall treatment, gymnasiums relied on suspended absorbers, and performance spaces used multi-strategy packages including variable acoustics systems. Open-plan learning spaces displayed high strategy diversity without consensus solutions. Mean quality score was 15.2/30 (SD = 3.0), with only 16.9% of projects reporting quantitative performance indicators. These findings reveal a substantial research-to-practice gap and provide an empirical basis for developing targeted acoustic design guidance for practitioners, informing policy, standards, and future research directions.

1. Introduction

1.1. Acoustics in K–12 Learning Environments

Classroom acoustics may be one of the most important yet most frequently overlooked factors in the design of educational facilities [1]. Systematic reviews have shown that, in schools worldwide, students often experience speech intelligibility of only 75% or lower, meaning that they may miss one quarter of instructional content, with measurable consequences for learning outcomes [2]. Poor acoustic conditions turn a basic precondition of teaching, students being able to hear and understand the teacher, into an uncertain proposition.

The effects of inadequate acoustics on student learning have been widely reported at three interrelated levels. At the student level, excessive background noise levels and reverberation time impair speech perception, listening comprehension, and short-term memory [3,4]. Experimental research further indicates that different types of environmental noise have significantly different degrees of interference with students’ attention [5]. Evidence indicates that children are more affected than adults because their executive functions are still developing and their capacity to compensate for degraded listening conditions is limited [6]. Long-term exposure to noisy classrooms is significantly associated with poorer performance on verbal tasks, reduced reading ability, and lower standardised test scores [7,8]. More recent studies further confirm that poor acoustic conditions affect not only basic cognitive functions (e.g., attention and memory) but also performance on complex academic tasks such as reading, writing, and arithmetic [9,10].

At the teacher level, inadequate acoustics impose substantial occupational costs. Epidemiological studies and meta-analyses show that, compared with the general population, teachers have a markedly elevated risk of voice disorders: approximately 11% report a current voice disorder, and nearly 60% experience voice problems over the course of their careers [11,12]. When classroom acoustic conditions are poor, teachers tend to compensate by increasing vocal intensity, a response termed the Lombard effect, which increases vocal fold collision forces and accelerates the development of phonotraumatic injury [13,14]. Recent scoping reviews further indicate that classroom noise not only causes vocal fatigue but is also associated with teachers’ mental health problems, increased work stress, and overall occupational burnout [15]. This hazard affects teachers’ physical and psychological health and also generates systemic costs for educational systems by increasing absenteeism and healthcare utilisation.

At the spatial level, the acoustic complexity of K–12 school buildings extends well beyond the traditional classroom. Contemporary educational facilities include diverse space types, from standard classrooms and open-plan teaching space to gymnasiums, performance halls, cafeterias, and circulation corridors. Each presents distinct acoustic challenges and requires tailored design strategies [16,17]. Of particular concern is the increasing prevalence of open-plan learning spaces. Although such spaces offer pedagogical flexibility, they also entail specific acoustic vulnerabilities: students must extract target speech amid competing speech signals generated by adjacent learning activities [18]. Unlike the relatively predictable reverberation issues in enclosed classrooms, the disruptive effect of irrelevant speech in open-plan settings is more cognitively damaging because the human auditory system processes speech information involuntarily, consuming cognitive resources that would otherwise support learning [19,20]. Recent work indicates that students in open-plan classrooms show significantly slower reading development than those in traditional enclosed classrooms and report significantly lower acoustic comfort [10,21].

Despite decades of research establishing recommended acoustic parameters for schools, and the development of design standards such as ANSI S12.60 (United States) [22], BB93 (United Kingdom) [23], and DIN 18041 (Germany) [24], a fundamental question remains unresolved: what acoustic conditions actually exist in built schools, and what design strategies have practitioners used to achieve them? Addressing these questions requires moving beyond laboratory research and peer-reviewed literature to examine evidence embedded in design practice itself.

1.2. The Research–Practice Gap in School Acoustic Design

Academic literature on classroom acoustics has produced robust conclusions regarding optimal acoustic parameters; however, a systematic disconnection persists between research evidence and design practice. This disconnection is not attributable to any single side but rather reflects structural misalignment between research production and practical application.

On the research side, existing investigations have largely focused on standardised classroom settings, especially traditional enclosed classrooms [1]. Yet spatial typologies in contemporary K–12 school architecture are increasingly complex: a single school may contain more than twenty functionally distinct space types, such as gymnasiums, cafeterias, open learning areas, and circulation corridors, which remain comparatively underexamined [18,25]. Integrative reviews have noted that educational building acoustics research concentrates mainly on three themes, acoustic conditions and their improvement, the effects of acoustic quality on student performance, and impacts on student and teacher health, while cross-cutting research across these themes and explicit linkages to design practice remain limited [26]. Moreover, much foundational evidence derives from controlled laboratory conditions that may not adequately represent variability in real educational environments [2].

On the practice side, designers and acoustic consultants confront constraints far more complex than those represented in research settings. They must address multiple space types simultaneously; balance acoustic performance against competing demands such as thermal comfort, daylighting, and natural ventilation; coordinate across architecture, mechanical engineering, and interior design [27]; and work within budget limitations that may preclude optimal acoustic solutions [28]. While standards such as ANSI S12.60 and BB93 specify performance targets for reverberation time and background noise level, international comparisons indicate that at least 15 different school acoustic standards and guidelines exist globally, differing in parameter requirements, scope of application, and legal enforceability [29]. Unless explicitly adopted by local authorities, these standards often lack mandatory force.

This research–practice gap is manifested across three stages of the knowledge translation chain:

- Input-stage gap: lack of strategy-oriented guidance. Research often specifies threshold targets (e.g., RT ≤ 0.6 s; background noise ≤ 35 dBA) yet provides limited guidance on which design strategies most effectively achieve these targets across different functions, forms, and budget conditions [30]. Practitioners face not only the question of “what should be achieved,” but, more critically, “how can it be achieved”, a question that the research literature addresses less frequently.

- Process-stage gap: a broken feedback loop. Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE) data that could validate design decisions and inform future practice are rarely published. Although POE is essential for closing the “design–construction–use” feedback loop, acoustics is often neglected in POE for educational buildings, receiving lower priority than thermal comfort and lighting quality [31].

- Output-stage gap: the tacit nature of practice knowledge. Knowledge and experience accumulated through completed projects, embedded in design documentation, project portfolios, and technical reports, typically circulate within professional networks and are seldom systematically documented or analysed. Architectural research has long recognised that much design knowledge remains tacit: acquired through experience and expressed through action rather than formal codification [32,33]. Research on professional practice communities similarly indicates that tacit knowledge shared within architectural firm networks is central to communities of practice yet difficult to capture in formal publications [34]. In school acoustic design, this means that valuable experience, such as how to select ceiling absorption materials under budget constraints, or which combinations of strategies are effective in open-plan settings, often remains outside the field of academic visibility.

To access this dispersed professional knowledge, it is necessary to move beyond conventional academic databases and examine the grey literature produced and used by practitioners.

1.3. Grey Literature as a Source of Practice-Based Evidence

Grey literature refers to documents produced outside commercial and academic publishing channels, including government reports, technical guidelines, conference proceedings, organisational white papers, and professional project documentation [35,36]. In systematic reviews, grey literature helps reduce publication bias, strengthens comprehensiveness, and provides evidence that may not appear in peer-reviewed journals, particularly findings reporting null effects or highly context-dependent results [37,38]. Although grey literature is well recognised in health sciences and public policy, systematic synthesis of such materials remains comparatively limited in architecture and acoustics [39,40].

In school acoustic design, grey literature is particularly important because substantial practice knowledge exists as project documentation rather than academic publications. Architectural firms record completed projects through design narratives and visual presentations; acoustic consultants prepare technical reports detailing performance targets and noise control strategies; and material suppliers publish project case studies demonstrating product applications. Grey literature often offers contemporaneity by documenting recent developments and industry dynamics [37]. Together, these sources constitute a body of practice-based evidence, recording what has actually been designed, built, and, in some cases, verified through measurement.

The concept of practice-based evidence reverses the conventional epistemic direction of evidence-based design [41,42]. Evidence-based design asks the following: what does research indicate practitioners should do? Practice-based evidence mapping asks the following: what have practitioners actually achieved, and what can be learned from those actions? This shift acknowledges the bidirectionality of knowledge production in architecture: research can guide practice, and practice itself contains experiential knowledge that warrants extraction and systematisation. By systematically extracting, coding, and evaluating grey literature across professional sources, researchers can render previously internal, tacit experience more explicit, enabling broader scholarly scrutiny and cumulative knowledge building.

In this study, grey literature is drawn from three source types:

- Architectural firm sources (Source_Architect): design descriptions, project pages, and portfolios documenting completed school projects, typically reviewed internally and representing an integrated architectural perspective.

- Acoustic consultant sources (Source_Acoustic Consultant): technical case studies and consultancy reports that include detailed acoustic parameters and design strategies, reviewed by professional acoustic engineers and representing a specialised technical perspective.

- Material supplier sources (Source_Material Supplier): project case studies documenting product applications in educational environments. Although commercially oriented, these sources often include performance data and represent an applied, product-focused perspective.

However, grey literature varies considerably in methodological rigour and transparency, requiring a systematic quality appraisal approach. Among available tools, this study adopts the AACODS framework (Authority, Accuracy, Coverage, Objectivity, Date, Significance), a checklist specifically developed for appraising grey literature in systematic reviews [43]. This framework has been applied in systematic reviews across multiple fields including health sciences, management, and public policy. The six-dimensional structure supports systematic and reproducible evaluation of materials that differ substantially in format, purpose, and intended audience [37,44].

Importantly, through the systematic mapping of practice-based evidence within these grey literature sources, this study aims to complement rather than replace existing laboratory and field research. Prior studies have established the scientific basis for acoustic performance parameters; the present work seeks to characterise how the design community has translated (or failed to translate) research evidence into the realities of the built environment, thereby identifying the translation gap between theory and practice and providing empirical grounding for efforts to narrow that gap.

1.4. Research Aims and Questions

Although the importance of school acoustics is widely acknowledged, existing research has mainly followed two lines of inquiry: (1) laboratory-based studies examining how acoustic parameters affect cognitive performance [1,3], and (2) field measurements and Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE) studies conducted in specific schools [28]. However, systematic examination of design practice itself remains limited, namely which acoustic strategies practitioners actually adopt in real projects, the extent to which these strategies reflect research recommendations, and how the quality of practice-based evidence varies across sources.

To address this gap, this study employs a systematic mapping approach to collect, code, and appraise grey literature on K–12 school acoustic design. Systematic mapping is a review method intended to describe the overall evidence landscape in a field. Unlike systematic reviews that concentrate on the effects of specific interventions, systematic mapping is exploratory and is suited to domains with high heterogeneity and limited prior synthesis [45,46]. Given the fragmented nature of school-acoustics grey literature and the lack of prior structured synthesis, systematic mapping provides an appropriate methodological framework for this study.

This study is guided by three research questions:

RQ1 (Evidence Landscape): What are the characteristics of existing grey literature on K–12 school acoustics? This question maps the distribution of practice-based evidence by examining (a) the distribution of source types providing acoustic design information (architectural firm, acoustic consultant, material supplier); (b) the geographic and temporal distribution of projects; and (c) the types of school buildings recorded (primary, secondary, or mixed).

RQ2 (Practice Patterns): What space–strategy combinations dominate current practice? This question identifies consensus and divergence in design practice by examining (a) acoustic intervention strategies commonly used across different space types (general classrooms, specialist classrooms, and public/common spaces) and (b) potential “design blind spots”, meaning space categories that are frequently addressed in academic research but sparsely documented in practice records.

RQ3 (Evidence quality): How reliable is this practice-based evidence, and what gaps exist in performance data? This question evaluates the methodological quality and information completeness of grey literature by examining (a) the distribution of evidence quality ratings based on the AACODS framework; (b) the extent to which projects report quantitative acoustic indicators (e.g., reverberation time, NC, Speech Transmission Index (STI)) rather than only qualitative descriptions; and (c) quality differences across source types.

By answering these questions, this study is expected to make three contributions:

Contribution 1 (Empirical): This study establishes the first systematic database of K–12 school acoustic design practice, covering 142 built projects across 22 countries. Beyond supporting future comparative studies and meta-analyses, the database consolidates practice knowledge that was previously dispersed within professional networks into a searchable and analysable public resource.

Contribution 2 (Methodological): This study develops and validates a grey-literature systematic mapping methodology suitable for the built environment domain, including a multi-source search strategy, an iterative parallel screening process, and a quantitative quality appraisal framework. This methodological framework is transferable to other building-performance topics with rich grey literature, such as daylighting design and thermal comfort optimisation.

Contribution 3 (Knowledge translation): This study empirically identifies the translation gap between academic recommendations and design practice, revealing which research evidence has been incorporated into practice and which remains largely confined to publications. These findings are critical for narrowing the current research–practice divide in school acoustics, providing an empirical basis for more targeted design guidance and improved knowledge translation strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Scope

This study adopts a systematic mapping approach to collect, code, and appraise grey literature on K–12 school acoustic design. The study follows the six-stage scoping review framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley [47] and incorporates methodological refinements recommended in subsequent guidance [45,48,49]. Reporting is prepared in accordance with the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [50].

This study focuses on K–12 educational buildings, including primary/elementary schools (typically serving students aged 5–11) and secondary schools (typically serving students aged 11–18), and includes both new construction and renovation/extension projects. No time restriction is applied in order to capture historical changes in acoustic design practice. The geographic scope is global to achieve broad representation of practice-based evidence [46].

Grey literature sources are classified into three categories according to the professional identity of the publisher to differentiate perspectives and levels of technical detail:

- Architectural firm sources (Source_Architect): design narratives, project pages, and portfolios documenting completed school projects, representing an integrated architectural perspective.

- Acoustic consultant sources (Source_Acoustic Consultant): technical case studies and consultancy reports that include detailed acoustic parameters and design strategies, representing a specialised acoustic-engineering perspective.

- Material supplier sources (Source_Supplier): project case studies presenting product applications in educational settings. Although commercially oriented, these sources often include verified performance data and represent an applied, product-focused perspective.

2.2. Search Strategy

Grey literature searching differs fundamentally from searching academic databases. Professional project documentation is dispersed across heterogeneous platforms without centralised indexing, complex Boolean search is often unsupported, and standardised metadata for screening is frequently absent [51]. Accordingly, this study adopts a multi-source approach combining targeted website searching with snowball sampling, comparable to hand-searching specific journals in systematic reviews [52]. To improve transparency and replicability, we prospectively specified platform selection rules, structured inclusion/exclusion criteria, and bias mitigation steps for firm- and supplier-authored records and applied these consistently during retrieval and screening (see Section 2.3).

Search sources included 27 professional platforms across three categories (Table A1):

- Architectural firm sources (n = 14): architectural firms with documented experience in educational projects were identified through industry award databases (e.g., education-facilities design awards), professional architecture media platforms (e.g., ArchDaily, Dezeen), and education-architecture rankings.

- Acoustic consultant sources (n = 8): relevant consultancies were identified through professional association member directories and through publicly documented educational building acoustic projects.

- Material supplier sources (n = 5): major manufacturers of acoustic ceilings, wall panels, and flooring were included, prioritising education project case studies that reported third-party performance testing data.

Search terms combined building-type terms with acoustic intervention-related terms (Table A2). Because platform search functions varied, the strategy was adapted as follows: term combinations were used on platforms supporting Boolean operators; single terms were searched separately on platforms permitting only keyword searching; and manual browsing by project category was used when internal search was unavailable.

Searches were conducted from 1 November to 10 December 2025. Languages were limited to English and Chinese, which provide broad coverage of documentation within architecture and acoustics. This pragmatic restriction improves feasibility and captures a large share of internationally disseminated practice documentation, but it may under-represent projects published primarily in other languages; therefore, geographic patterns reported in Section 3.1 should be interpreted as visibility within English- and Chinese-language professional channels rather than a complete census of global practice.

2.3. Selection Process

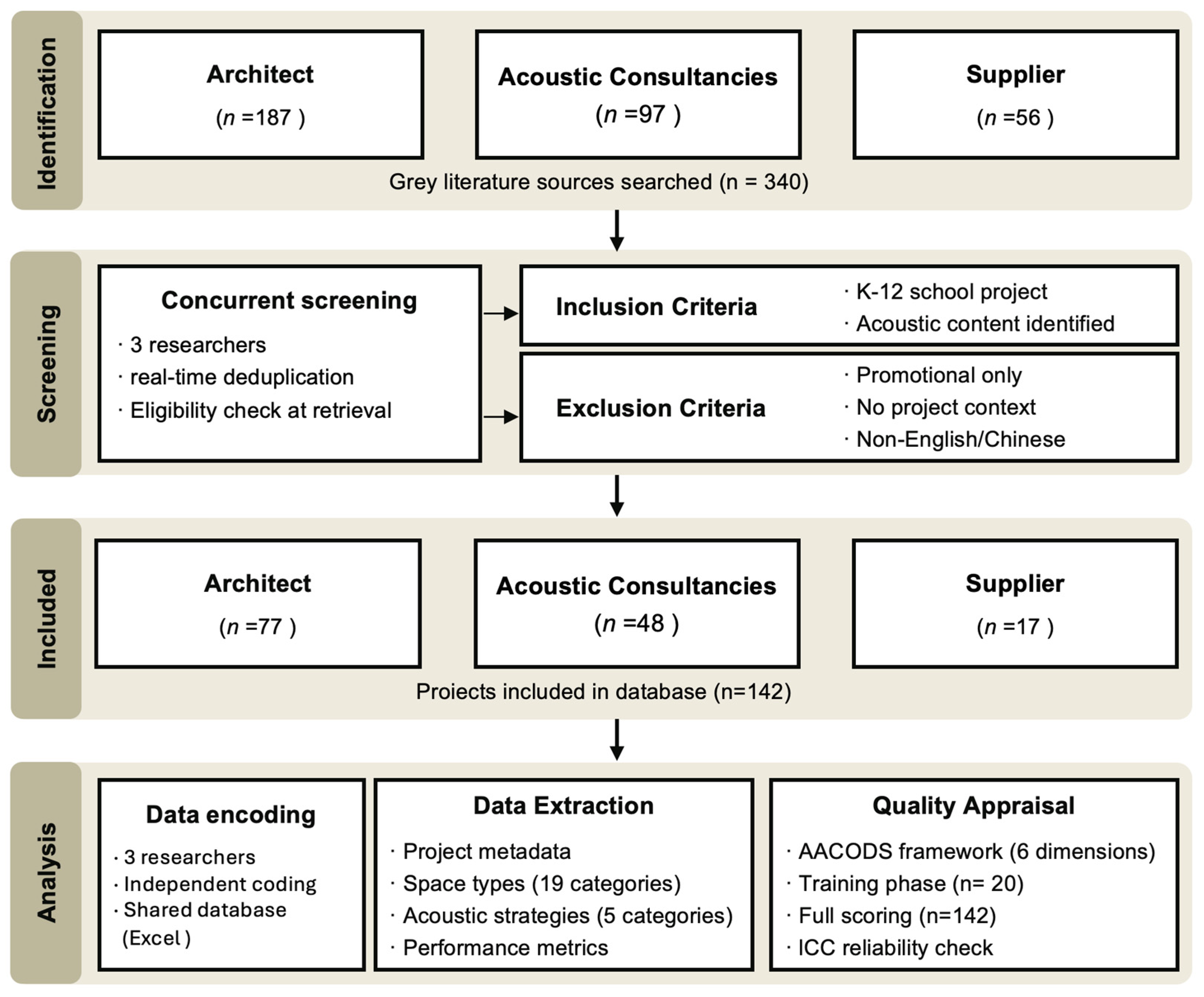

Screening followed an iterative parallel approach suited to grey literature (Figure 1). Unlike conventional academic database reviews, where records are retrieved in bulk, deduplicated, and then screened in staged steps, grey literature materials are diverse in format, unstable in availability, and often lack standardised metadata. Therefore, materials were appraised at the time of retrieval [37]. Three researchers conducted searches in parallel across their assigned platforms and evaluated materials during the search process using predefined criteria.

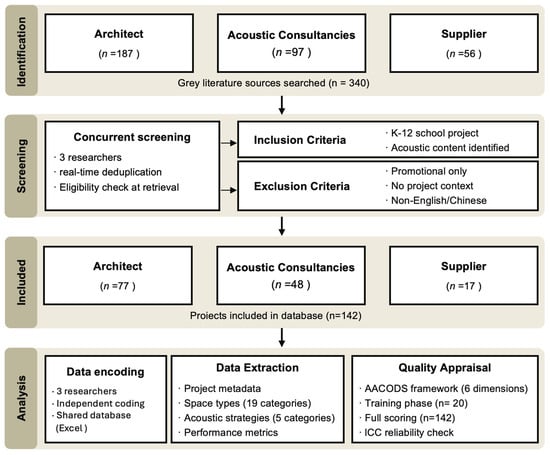

Figure 1.

Systematic mapping workflow. Grey literature sources were identified across three categories and screened concurrently by three researchers with real-time deduplication. Included projects (n = 142) underwent independent data coding, extraction using a standardised framework, and quality appraisal using the AACODS checklist.

Before formal screening, the three researchers independently conducted a pilot screening of 20 randomly selected candidate projects. Disagreements were discussed to calibrate interpretation and application of the inclusion/exclusion criteria [49].

Materials were included if they met both conditions: (1) they documented a K–12 school building project (primary, secondary, or mixed) and (2) they contained identifiable and substantive acoustic design content, including but not limited to the application of acoustic materials/products, descriptions of acoustic performance parameters, explanations of design strategies addressing acoustic issues, or documentation of acoustic consultant involvement.

Materials were excluded if any of the following applied: (1) they provided only generic marketing statements (e.g., “excellent acoustic solutions”) without technical specificity; (2) they described product features without presenting the project application context; or (3) the building type was a higher-education institution, kindergarten/childcare facility, training centre, or another non-K–12 educational facility. Records outside the English/Chinese language scope were also excluded by design (Section 2.2).

Eligible projects were entered directly into a shared Excel database, recording project name, source URL, source type, and the initial rationale for inclusion. Borderline cases were flagged and resolved through discussion in weekly team meetings. Ongoing duplicate checks were performed within the shared database: if the same project appeared across multiple sources, the most information-rich record was retained as the primary record, while all identified sources were noted to enable cross-source triangulation and reduce reliance on any single promotional narrative.

Because many records were authored by architectural firms or material suppliers, we anticipated promotional framing and “success bias” (i.e., preferential public reporting of exemplary projects) [37]. To mitigate this bias, we (i) linked multiple sources per project when duplicates occurred; (ii) coded and analysed the most information-rich record as the primary unit while retaining alternative sources for cross-checking; (iii) extracted only verifiable design facts using the predefined coding framework (spaces, strategies, and reported metrics) rather than subjective claims; and (iv) evaluated Objectivity as an explicit AACODS dimension, enabling the interpretation of evidence quality to account for promotional tone.

A total of 142 unique school building projects with documented acoustic design information were included. The complete flow diagram is provided in Figure 1, reported in accordance with PRISMA-ScR [50].

2.4. Data Extraction Framework

A standardised coding framework was developed to extract comparable data from heterogeneous grey literature sources. The framework draws on scoping-review guidance for data charting and comprises four levels [48]:

- Project metadata recorded contextual information, including project name, country, completion year, education stage (primary, secondary, or mixed), project type (new build, renovation, or extension), and source category. Projects lacking time information were coded as “Not reported”.

- Space types were classified according to the functional spaces in which acoustic interventions were implemented. Based on functional zoning approaches [53] in architectural programming literature and on typical school-space groupings discussed in major school-acoustic guidance (e.g., ANSI S12.60 and BB93) [22,23], and refined through pilot coding, a final classification framework comprising 19 space types was established (Table 1). Each project could be coded to multiple space types to reflect the multi-space character of school buildings; complete subcategory coding is provided in Table A3. To improve practical interpretability, “Function Hall” was defined to cover multi-purpose/multi-functional halls (e.g., assemblies, exhibitions, community events), whereas outdoor or semi-outdoor learning areas were not coded because they were rarely documented with explicit acoustic strategies in the retrieved grey literature and fall outside enclosed-room acoustic metrics.

Table 1. Data extraction framework for K–12 school acoustic design.

Table 1. Data extraction framework for K–12 school acoustic design. - Acoustic strategies were categorised using a classical hierarchy of architectural acoustic interventions [54], grouping strategies by their physical control mechanisms into five major categories with 16 subcategories (Table 2): interior surface treatment (Interior Surface, IS), room acoustic elements (Room Acoustic Elements, RA), spatial planning (SP), envelope and partition (EN), and systems and equipment (Systems and Equipment, SE). Coding was conducted at the subcategory level; the full codebook is provided in Table A4. Subcategory definitions were iteratively refined during pilot coding to maximise coverage of heterogeneous grey literature reports while maintaining mutual exclusivity across categories.

Table 2. AACODS scoring criteria for grey literature quality.

Table 2. AACODS scoring criteria for grey literature quality. - Performance indicators captured quantitative acoustic parameters reported in the grey literature. Indicators were classified by type (reverberation time, speech intelligibility, background noise, and sound insulation ratings) and by reporting status (design targets, simulation predictions, or post-completion measurements), thereby distinguishing design intent from verified outcomes [55]. Referenced acoustic standards (e.g., ANSI S12.60, BB93, DIN 18041, GB 50118 [56]) were also recorded.

Three researchers independently coded all 142 projects using the shared database. Prior to full coding, a pilot coding exercise on 20 projects was conducted, yielding an agreement rate of 82%. Disagreements during formal coding were resolved through team discussion and then entered into the final database.

2.5. Quality Appraisal

Grey literature sources vary substantially in methodological rigour and reporting transparency, making systematic quality appraisal essential. This study appraised grey literature quality using the AACODS framework. AACODS is a checklist developed specifically for evaluating grey literature within systematic reviews and has been widely used in health sciences and management research [37,43]. The framework evaluates six dimensions: Authority, Accuracy, Coverage, Objectivity, Date, and Significance.

To enable quantitative analysis, the original checklist was converted into a 5-point Likert scale (Table 1 Panel B), and explicit scoring criteria were developed for each dimension (Table A5). Total scores ranged from 6 to 30. Using an equal-interval approach, overall quality was categorised into four levels: low quality (6–12), moderate quality (13–18), moderate-high quality (19–24), and high quality (25–30).

Inter-rater reliability was examined using a two-stage procedure.

- Calibration phase: Three researchers independently rated a random sample of 20 projects. Inter-rater reliability was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient under a two-way random-effects model for absolute agreement. Initial mean ICC values varied across dimensions, ranging from 0.697 (Objectivity) to 1.000 (Authority and Date), with a total-score ICC of 0.965. For dimensions with lower agreement, the research team clarified scoring boundaries through discussion and established shared interpretations.

- Formal rating phase: Following the calibration, three raters independently assessed all 142 projects. The inter-rater reliability was found to be excellent across all dimensions. Specifically, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for average measures on the total score increased to 0.989 (95% CI [0.986, 0.992]). Based on the criteria established by [57]—where values greater than 0.90 indicate excellent reliability—the consistency among raters was deemed highly satisfactory. The complete results of the reliability analysis are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3. Inter-rater reliability of AACODS scoring.

Table 3. Inter-rater reliability of AACODS scoring.

All AACODS dimensions were scored independently by three raters. During calibration and full scoring, items with a difference of >1 point on any dimension were flagged for discussion; raters revisited the underlying project record to identify the specific evidence supporting each score. When disagreements could not be resolved, the corresponding author adjudicated using the operational rubric, and the final rationale was logged in the database to preserve an audit trail. An anonymised worked example linking reported evidence to AACODS scores is provided in Appendix A Table A9.

For each project, the arithmetic mean of the three raters’ scores was calculated for each dimension; the six dimension means were then summed to yield the total AACODS score (range: 6–30).

2.6. Data Analysis

Data analysis proceeded in three stages aligned with the three research questions. The unit of analysis differed by question—RQ1 and RQ3 used projects as the unit (n = 142), whereas RQ2 used space instances as the unit (n = 224)—because a single project could include multiple space types and acoustic strategies were coded independently for each space type.

RQ1 (evidence landscape): Descriptive statistics were used to characterise the sample by source type, geographic distribution, temporal pattern, education stage, and project type. Frequency distributions and contingency tables were used to identify patterns in evidence availability across regions and time periods.

RQ2 (design typologies): Associations between space types and strategies were analysed by constructing a space–strategy co-occurrence matrix. Rows represented the 19 identified space types, and columns represented five strategy categories comprising 16 subcategories. Cell values indicated the number of occurrences of a given strategy in a given space type. To support cross-space comparison, absolute frequencies were converted to row percentages. Results were visualised as a heatmap using a continuous colour scale to represent co-occurrence frequency, with rows and columns ordered in descending totals to highlight high-frequency combinations.

RQ3 (evidence quality): Means, standard deviations, and frequency distributions were used to summarise AACODS total scores and dimension scores. Reporting rates for performance indicators were calculated as the proportion of projects reporting each indicator type and reporting status. Frequencies of referenced standards were tabulated to examine alignment between practice documentation and regulatory frameworks. Differences in quality by source type were tested using one-way ANOVA, with α = 0.05.

Statistical analysis was conducted in SPSS 24.0. Data visualisation was produced in Origin 2024.

3. Results

3.1. Evidence Landscape (RQ1)

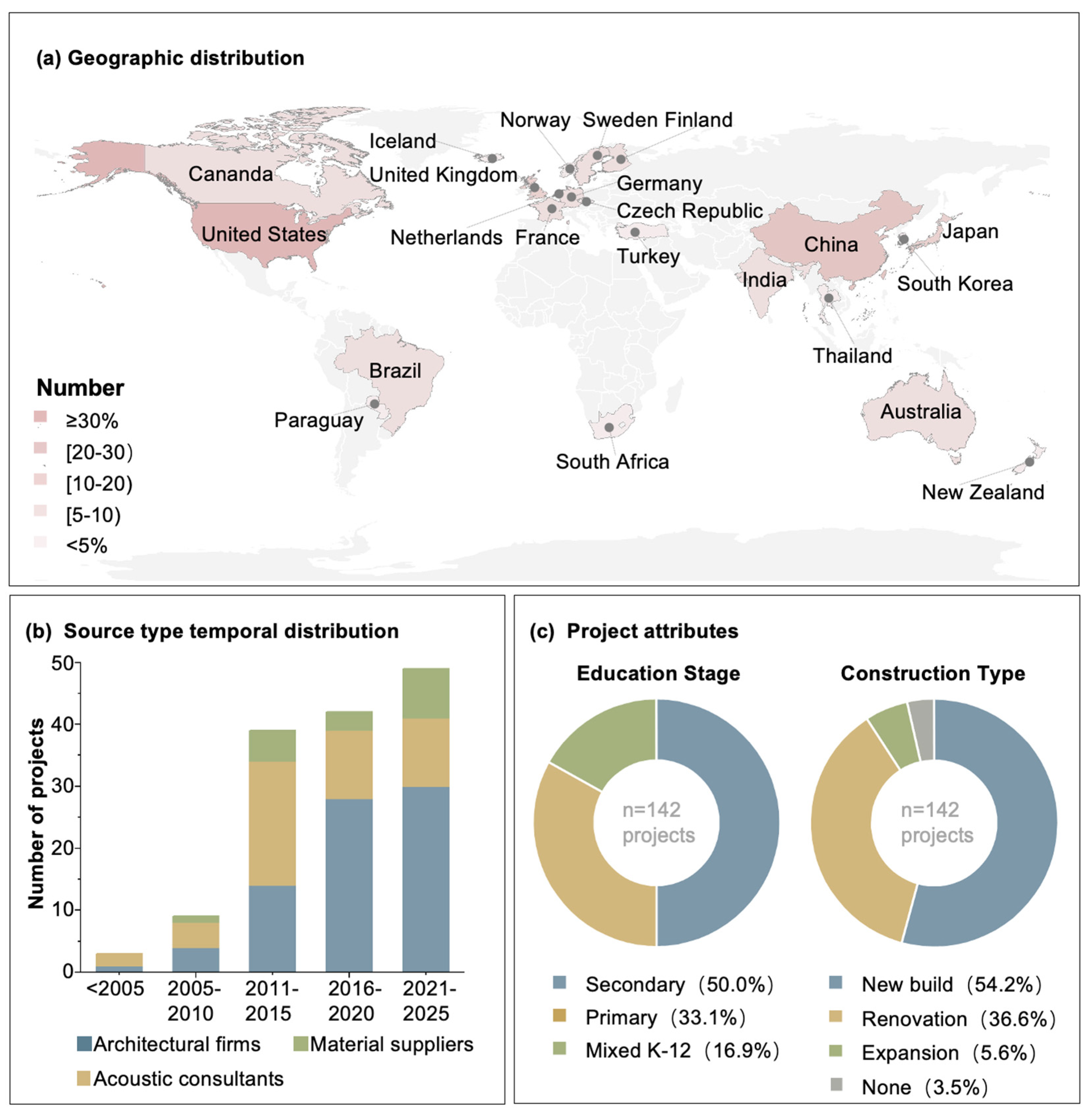

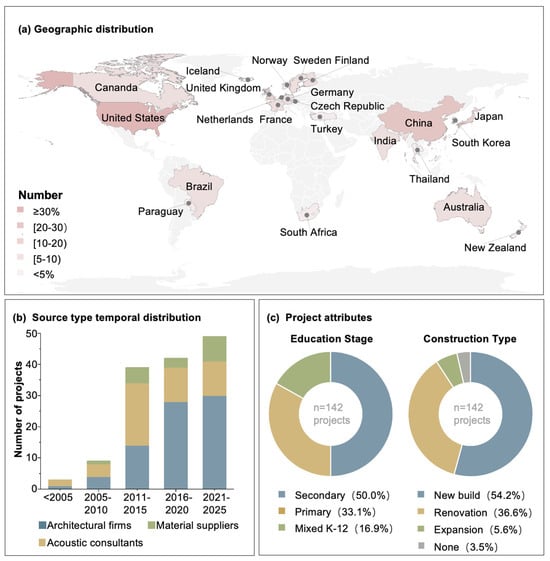

To address RQ1 (Evidence landscape), this section systematically describes source distribution, geographic and temporal characteristics, and project attributes. The systematic mapping included 142 K–12 school projects with documented acoustic design information, identified from 27 grey literature sources across 22 countries (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sample characteristics of 142 K–12 school acoustic design projects. (a) Geographic distribution across 22 countries; colour intensity indicates project percentage. (b) Temporal distribution by source type. (c) Distribution by educational stage and construction type.

Architectural firm documentation constituted the largest source category (n = 77, 54.2%), followed by acoustic consultant case studies (n = 48, 33.8%) and material supplier project applications (n = 17, 12.0%). This distribution reflects the division of labour in project documentation: architectural firms, as lead integrators of multi-disciplinary information, are primary producers of comprehensive project narratives, whereas acoustic consultants publish less frequently but typically provide richer technical detail and performance data.

Projects spanned 22 countries across six continents, with marked regional concentration (Figure 2a). North America contributed the largest share (n = 59, 41.5%), with the United States alone accounting for 56 projects (39.4%). The Asia–Pacific region ranked second (n = 38, 26.8%), led by China (n = 22, 15.5%). Europe ranked third (n = 31, 21.8%), with the United Kingdom, Germany, and Nordic countries as major contributors. Oceania (n = 7, 4.9%), South America (n = 5, 3.5%), and Africa (n = 2, 1.4%) were comparatively underrepresented. This geographic skew likely reflects multiple factors: restricting searches to English and Chinese may have reduced coverage in regions where Spanish and Portuguese dominate; additionally, in some regions, architectural acoustics practice may still be developing, and grey literature may have limited online accessibility.

Completion years showed a strong recent concentration (Figure 2b). Projects completed in 2021–2025 accounted for 34.5% (n = 49), and those completed in 2016–2020 accounted for 29.6% (n = 42), meaning that 64.1% of projects were completed within the past decade. This pattern likely reflects the time sensitivity of web-based grey literature, where older project pages may become inactive or be overwritten, as well as a continuing rise in professional attention to educational acoustics.

By education stage, secondary schools were most common (n = 71, 50.0%), followed by primary schools (n = 47, 33.1%) and mixed K–12 schools (n = 24, 16.9%) (Figure 2c). The higher proportion of secondary projects may be attributable to their more diverse space typologies (e.g., specialist music rooms, auditoria, and gymnasiums), which demand more intensive acoustic design and are therefore more frequently documented. By project type, new construction dominated (n = 77, 54.2%), followed by renovation (n = 52, 36.6%), with extensions least represented (n = 8, 5.6%). The prominence of new builds may indicate greater feasibility for comprehensive integration of acoustic design. Full sample attributes are reported in Table A6.

3.2. Space-Strategy Patterns (RQ2)

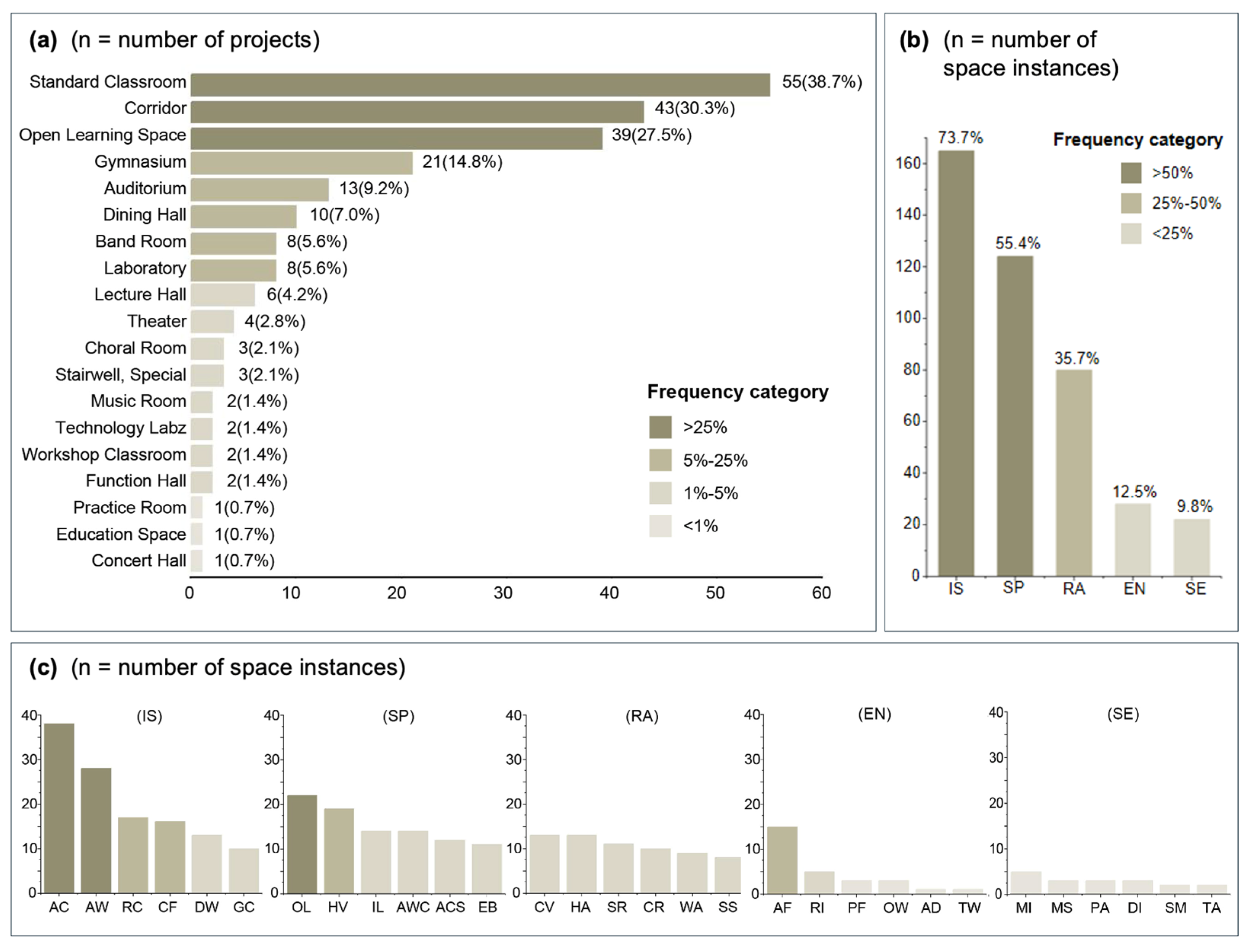

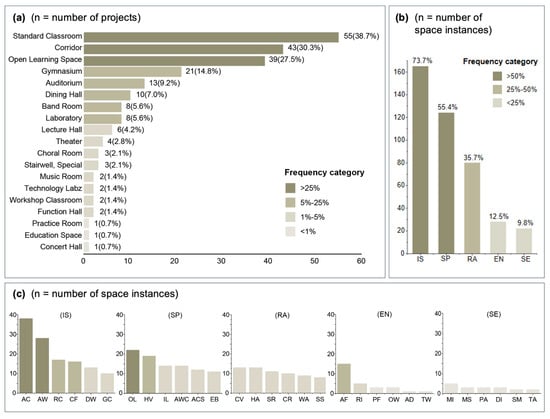

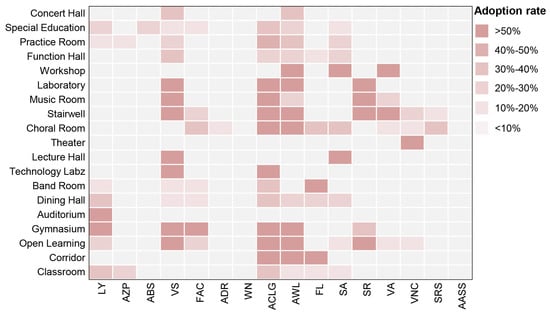

To address RQ2 (practice patterns), this section analyses space-type coverage, strategy adoption patterns, and space–strategy associations. Across the 142 projects, the dataset contained 224 independent space instances, covering 19 space types (Figure 3). In the analyses below, “project share” uses 142 projects as the denominator, whereas “space instances” uses 224 instances.

Figure 3.

Distribution of space types and acoustic strategies in 142 K–12 school acoustic design projects. (a) Frequency of space types documented across projects. Bars indicate the number of projects containing each space type; percentages show proportion of total projects (n = 142). Space type codes defined in Table 1. (b) Adoption rates of five acoustic strategy categories. Bar height represents the number of space instances employing each strategy category; percentages indicate proportion of total space instances (n = 224). IS = Interior Surface; SP = Spatial Planning; RA = Room Acoustic Elements; EN = Envelope/Partition; SE = Systems and Equipment. (c) Distribution of specific strategies within each category. Sub-panels correspond to the five strategy categories: (IS) Interior Surface, (SP) Spatial Planning, (RA) Room Acoustic Elements, (EN) Envelope/Partition, and (SE) Systems and Equipment. Bar height indicates the number of projects adopting each strategy subcategory. Strategy codes defined in Table 1 and Table A1. A single project may include multiple space types and strategies, resulting in 224 total space instances across 142 projects. Complete definitions provided in Table A3 and Table A4.

Documentation coverage varied substantially by space type (Figure 3a). Standard classrooms were the most comprehensively documented (n = 55, 38.7%), followed by corridors (n = 43, 30.3%), open-plan teaching space (n = 39, 27.5%), and gymnasiums (n = 21, 14.8%). Spaces with high acoustic demands, including auditoria, lecture halls, and music-related spaces, collectively accounted for approximately 30% of the sample, reflecting their strong dependence on acoustic design. Notably, stairwells, restrooms, special education spaces, and technical classrooms were severely underrepresented or entirely absent, indicating systematic documentation gaps for these space categories.

Across the five strategy categories, adoption showed a clear hierarchy (Figure 3b,c; strategy code definitions are provided in Table 2). Interior surface treatment was the dominant strategy category in practice. Absorptive ceiling treatment was documented in 38 projects (26.8%), absorptive wall treatment in 28 projects (19.7%), and floor treatment in 16 projects (11.3%). Spatial planning strategies were also common: layout optimisation appeared in 22 projects (15.5%), and massing/form strategies in 19 projects (13.4%). Room acoustic elements were less frequently documented: discrete absorptive elements appeared in 13 projects (9.2%), reflective elements in 11 projects (7.8%), and variable acoustics systems in only 4 projects (2.8%). Reporting rates for envelope and partition and systems and equipment were the lowest.

This hierarchy suggests two tendencies in practice: (1) a strong preference for passive surface-based strategies, which are typically lower cost, produce visible and straightforward effects, and are easier to integrate within architect-led workflows; and (2) a cautious stance toward active systems and specialised equipment, which require acoustic expertise and dedicated budgets.

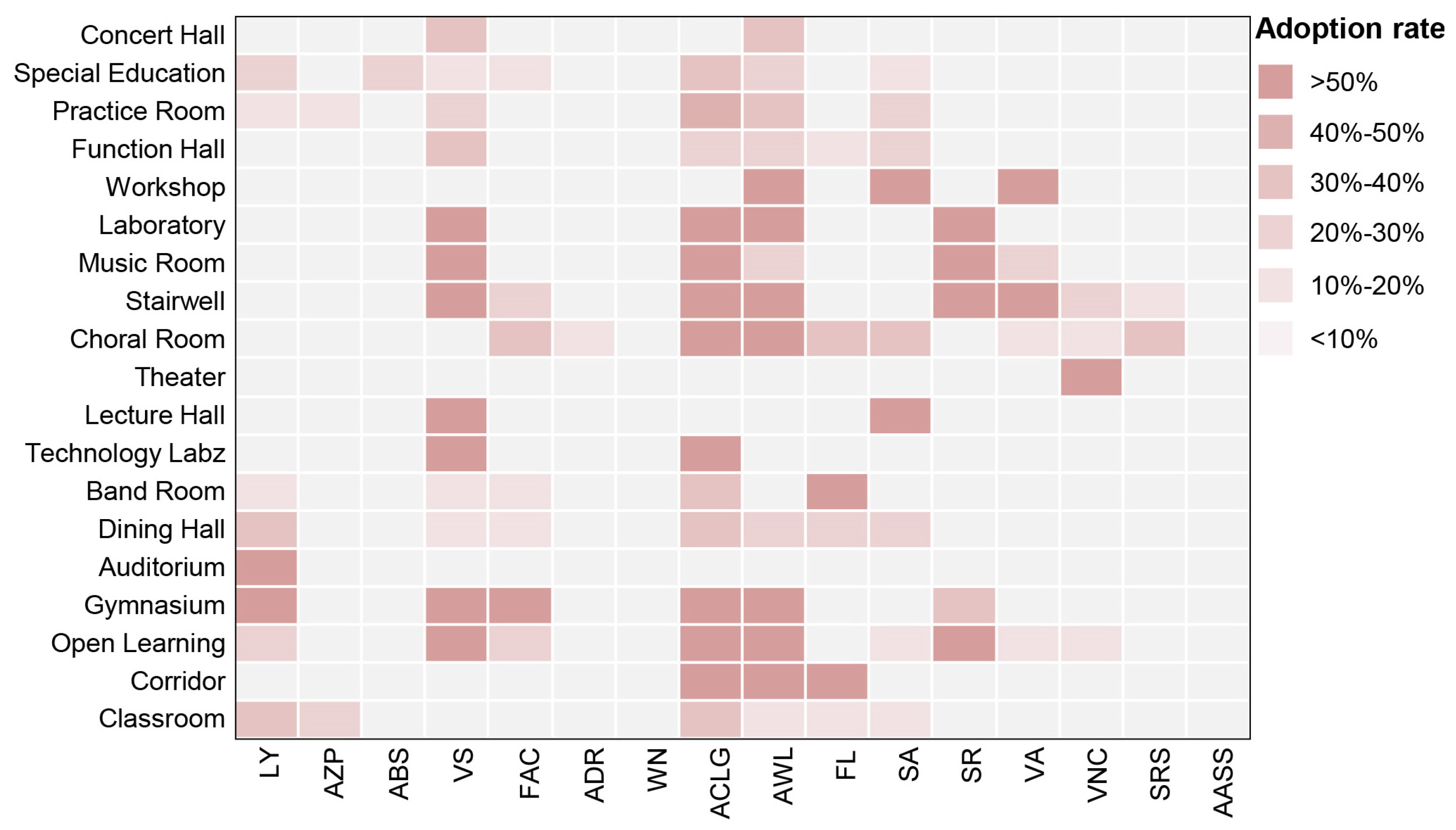

The space–strategy co-occurrence heatmap (Figure 4) revealed several dominant patterns: (1) standard classrooms and corridors most often relied on absorptive ceilings combined with absorptive wall treatment; (2) gymnasiums relied on suspended absorbers and impact-resistant wall panels, balancing absorption efficiency with durability; (3) performance spaces employed multi-strategy packages, including reflective panels, variable acoustics systems, and enhanced sound insulation; and (4) strategy use in open-plan teaching space was highly diverse and lacked a prevailing solution, suggesting that design norms for this emerging typology remain in development.

Figure 4.

Space–strategy co-occurrence heat map for K–12 school acoustic design. Cell values represent the percentage of projects implementing each strategy within each space type (row percentages). Colour intensity indicates adoption rate: white = 0%, darkest shade = maximum observed percentage. Rows (19 space types) and columns (16 strategy subcategories) sorted by total frequency in descending order. Full strategy definitions provided in Table A4.

The analysis identified three major evidence gaps: (1) variable acoustics systems were documented almost exclusively in performance spaces; (2) sound insulation strategies were rarely reported for open-plan teaching space; and (3) special education spaces, technical classrooms, vertical circulation spaces, and restrooms showed little to no systematic documentation of acoustic design. Full space–strategy frequency distributions are provided in Table A7.

3.3. Evidence Quality and Data Gaps (RQ3)

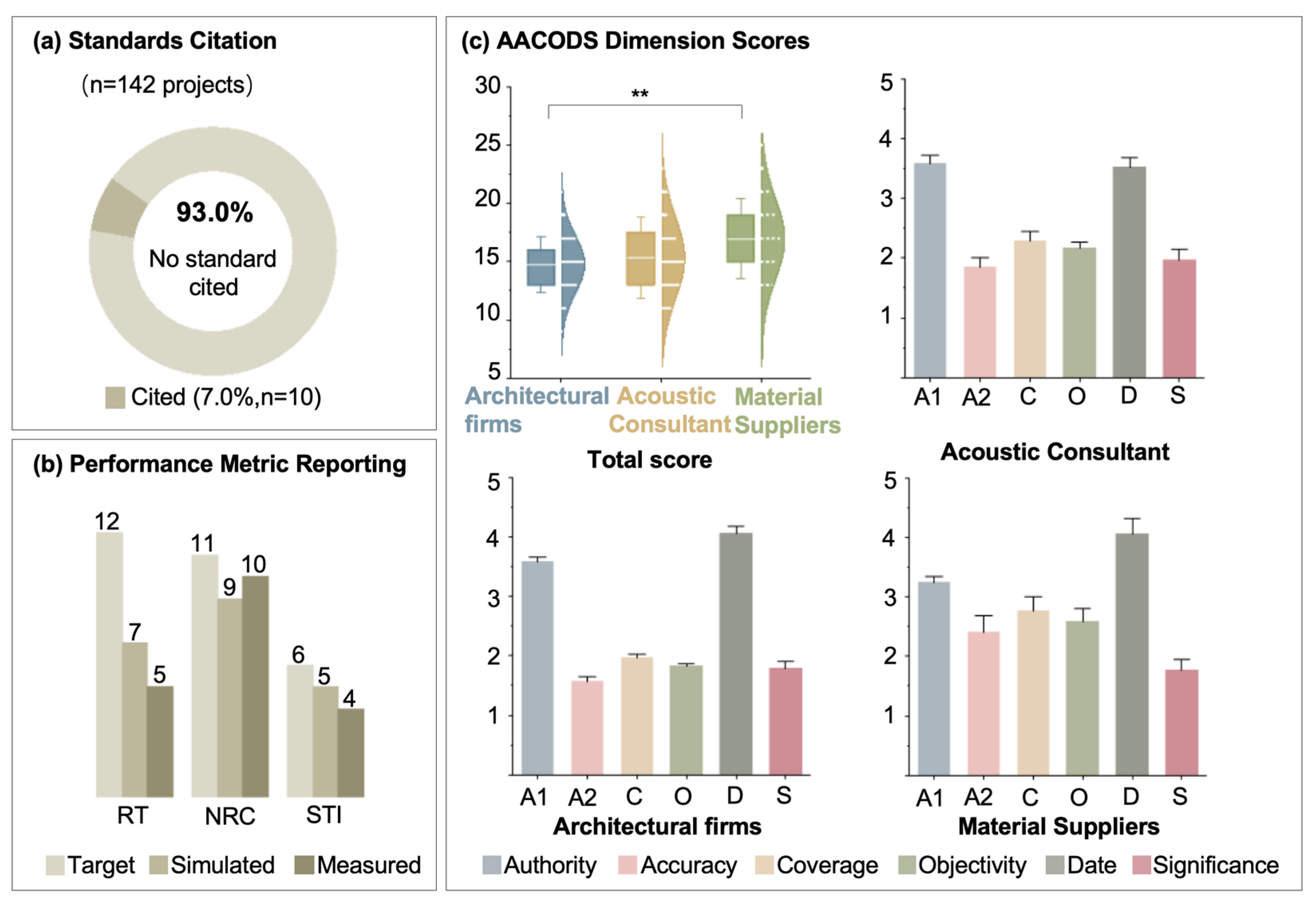

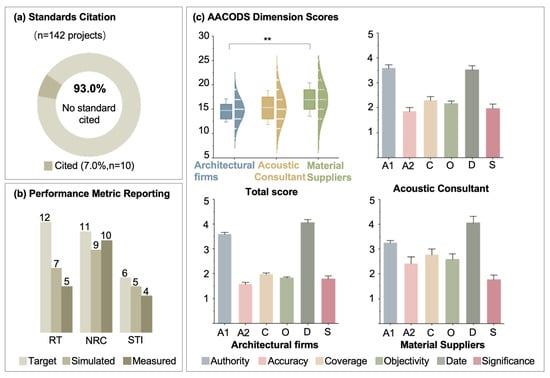

To address RQ3 (evidence quality), this section evaluates the reliability of practice-based evidence from three perspectives: AACODS quality scores, reporting of performance indicators, and references to standards (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Evidence quality assessment of 142 K–12 school acoustic design projects. (a) Frequency of acoustic standards cited in project documentation (7.0% cited, 93.0% not cited). (b) Reporting rates of quantitative acoustic performance metrics by metric type and reporting status (design target, simulation, post-occupancy measurement). (c) Distribution of AACODS total scores by source type; horizontal lines indicate quality grade thresholds (12, 18, 24). AACODS dimensions: Authority (A1), Accuracy (A2), Coverage (C), Objectivity (O), Date (D), Significance (S). Maximum possible score = 30. ** p < 0.01.

Across the 142 projects, total AACODS scores ranged from 8 to 24 (out of 30), with a mean of 15.2 (SD = 3.0) (Figure 5a). By quality category, 24 projects (16.9%) were rated as low quality (6–12), 95 (66.9%) as moderate quality (13–18), 23 (16.2%) as moderate-high quality (19–24), and 0 (0%) as high quality (25–30). Overall, the sample was predominantly of moderate quality, and no project met the high-quality threshold, indicating systematic limitations in the methodological rigour of grey literature.

Quality also differed by source type. Material supplier case studies received the highest scores (M = 17.0, SD = 3.5), followed by acoustic consultant sources (M = 15.3, SD = 3.4), while architectural firm documentation scored lowest (M = 14.8, SD = 2.4). One-way ANOVA indicated a statistically significant difference across source types (F(2, 139) = 3.868, p = 0.023 < 0.05). Post hoc comparisons (Tukey HSD) showed that material supplier scores were significantly higher than those of architectural firm sources (Δ = 2.2, 95% CI [0.78, 3.57], p = 0.003 < 0.05), whereas differences involving acoustic consultant sources did not reach statistical significance.

Substantial variation was observed across the six AACODS dimensions (Figure 5b). Authority (M = 3.5) and Date (M = 3.9) scored relatively high, suggesting that the sample was largely produced by reputable professional organisations and that recently completed projects constituted a large share of the dataset. Accuracy (M = 1.8) and Significance (M = 1.9) scored lowest, indicating systematic deficiencies in technical rigour and in the reported practical value of the evidence.

Reporting rates for quantitative acoustic indicators were generally low (Figure 5c). Reverberation time (RT) was reported in only 10 projects (7.0%); Noise Reduction Coefficient (NRC) in 9 projects (6.3%); and Speech Transmission Index (STI) in 5 projects (3.4%). Overall, only 24 projects (16.9%) reported any quantitative acoustic indicator.

By reporting status, 29 projects (20.4%) reported only design target values, 21 projects (14.8%) reported simulation predictions, and only 19 projects (13.4%) reported post-completion measurements. The scarcity of measured data fundamentally limits the verifiability of practice-based evidence.

Only 10 projects (7.0%) referenced specific acoustic standards, including BB93 (United Kingdom, n = 3), ANSI S12.60 (United States, n = 1), GB 50118 (China, n = 2), ISO 3382-1 (Switzerland, n = 2) [58], and other standards. In contrast, 93.0% of projects relied on qualitative descriptions rather than standardised performance metrics. Projects providing standard references were almost exclusively drawn from acoustic consultant sources, further indicating systematic quality differences across source types. Full quality appraisal and indicator-reporting data are provided in Table A8.

Taken together, these results indicate that the current grey literature rarely provides a complete “strategy-to-performance” evidence chain: strategies are commonly described, but their outcomes are seldom reported with quantitative indicators or post-completion measurements. Consequently, the space–strategy patterns in Section 3.2 should be interpreted as prevalence maps of documented interventions rather than validated estimates of strategy effectiveness.

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Positioning of the Main Findings

This systematic mapping provides the first structured analysis of grey literature on K–12 school acoustic design, covering 142 projects across 22 countries. The findings establish an empirical basis for addressing the research–practice gap in school acoustic design and characterise key features and constraints of the current ecosystem of practice-based evidence.

Imbalance in the evidence landscape (RQ1): The source distribution (architectural firm sources 54.2%, acoustic consultant sources 33.8%, material supplier sources 12.0%) reflects the professional configuration of knowledge production in school acoustic design. Architects are the primary drivers of project documentation, whereas material suppliers publish less frequently but tend to provide cases with greater technical depth. This study’s results show that different sources have structural differences in AACODS dimensions (see Section 3.3). The geographic concentration of projects (North America and Asia–Pacific accounting for 68.3%) is partly attributable to the accessibility of English- and Chinese-language grey literature, but it may also indicate regional differences in attention to educational acoustics. Notably, the proportion of European projects (21.8%) was lower than expected given Europe’s leading role in developing school acoustic standards. One possible explanation is that, where acoustic performance is treated primarily as a compliance requirement rather than a design feature, the motivation to publicly showcase acoustic aspects of projects may be reduced. Beyond language and online accessibility, regional regulatory and procurement contexts may also influence what is publicly documented: where school acoustic performance is formalised in standards or compliance processes, practitioners may be more likely to specify targets and consultant involvement, whereas in voluntary contexts acoustic work may be less visible in public-facing narratives.

Hierarchical structure of strategy adoption (RQ2): The dominance of interior surface treatment strategies (absorptive ceilings 48.6%, absorptive wall panels 33.8%) is consistent with core principles of architectural acoustics: passive absorption-based approaches are often the most cost-effective means of controlling reverberation time. This echoes the systematic review by Minelli et al. [2], which identified sound absorption as the primary intervention for classroom acoustics. At the same time, the low adoption of active systems (sound reinforcement system 4.2%; sound masking 3.5%) suggests that acoustic design in most K–12 schools remains focused on meeting basic reverberation thresholds rather than moving toward more fine-grained optimisation of speech intelligibility. This contrasts with Mealings et al.’s [25] L3 framework, which advocates comprehensive acoustic strategies beyond simple reverberation time control for diverse learning environments. Yang et al. [59] demonstrated that meeting reverberation time standards alone cannot ensure speech intelligibility or privacy in open-plan spaces, highlighting the need for multi-parameter acoustic evaluation frameworks. Li et al. [60] showed that different activity types have distinct acoustic requirements, suggesting K–12 school design should differentiate spaces by function.

The documented distribution of space types also reveals clear “evidence blind spots.” Although open-plan teaching space appeared in 27.5% of projects, it showed highly heterogeneous combinations of strategies and lacked a prevailing consensus comparable to the “absorptive ceiling” norm commonly seen in traditional classrooms. Special education spaces, technical classrooms, and stairwells were almost entirely absent from practice documentation. This pattern may reflect either a genuine lack of established best-practice guidance for these spaces or limited incentives and channels for practitioners to record and share successful solutions. In either case, the presence of evidence blind spots implies that designers have limited precedent-based resources when addressing these spaces.

Structural differences in evidence quality (RQ3): AACODS appraisal revealed systematic limitations in current practice-based evidence. Most projects (66.9%) fell into the moderate-quality range (13–18), and none reached the high-quality threshold (25–30). Material supplier sources achieved the highest mean score (M = 17.0), followed by acoustic consultant sources (M = 15.3) and architectural firm sources (M = 14.8). These differences were mainly associated with Accuracy (depth of technical detail) and Objectivity (balance between information and promotion). Higher scores among material supplier cases may be related to their frequent inclusion of product performance data verified through third-party testing, whereas architectural firm documentation tends to prioritise design narratives over technical parameters. The most critical weaknesses were the low reporting rates of quantitative performance indicators (RT: 7.0%; STI: 3.4%) and the scarcity of standard references (6.3%). This indicates that most practice documents describe strategies without providing the performance evidence required to support cumulative “strategy–performance” knowledge development.

To clarify what the mean AACODS score (15.2/30) implies for end users, we interpret the four quality bands as differing “actionability” levels. Low (6–12) documents are primarily inspirational (visual narratives) and may support early ideation but not specification; moderate (13–18) documents can inform concept selection and highlight common strategy categories yet usually lack sufficient data for verification; moderate-high (19–24) documents are potentially actionable for preliminary design because they more often report multi-space strategies, reference standards or explicit targets, and occasionally include simulations or measurements; and high (25–30) would represent replicable, performance-verified cases, which were absent in our sample. Importantly, AACODS assesses the quality of reported evidence rather than the actual acoustic performance of built projects; a well-performing project may be poorly documented and vice versa.

4.2. Underlying Causes of the Practice–Evidence Gap

The disconnection between practice and evidence identified in this study is not incidental; it is rooted in structural problems within the knowledge-production system for school acoustic design. Understanding these causes is essential for developing effective improvement strategies.

First, practitioners often lack institutional incentives to publish detailed technical data. Commercial sensitivity can constrain public release of performance information; academic publishing systems rarely recognise the knowledge contribution of practice case documentation; and clients commonly do not require systematic acoustic acceptance testing [61]. This incentive misalignment results in substantial practice knowledge remaining as tacit knowledge embedded in professional experience rather than being transformed into explicit, searchable evidence resources. In turn, the sector faces an ongoing challenge of organisational “forgetting”, where lessons learned are not reliably retained or transmitted beyond project teams [62].

Second, the scarcity of Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE) data (with only 13.4% of projects reporting post-completion measurements) reflects a systemic breakdown in the “design–construction–use” feedback loop. The concept of a performance gap [63], where measured building performance deviates from design intent, appears particularly salient in school acoustics. Without POE data, even when strategies perform poorly in real settings, negative outcomes are unlikely to be systematically recorded and disseminated, increasing the risk that similar problems will recur. In educational building POE practice, acoustics is frequently treated as a secondary consideration compared with thermal comfort and lighting quality, which further reduces opportunities for evidence accumulation [31].

Third, although standards such as ANSI S12.60, BB93, and DIN 18041 provide clear performance criteria and design guidance, only 7.0% of projects referenced any acoustic standard in their documentation. This “existence without application” pattern may have several explanations: many standards are not mandatory (with notable exceptions in certain jurisdictions), reducing incentives for explicit compliance; technical language in standards may be difficult to integrate into design workflows; and standard references may be considered non-essential in publicly oriented project narratives and therefore omitted. Moreover, the fragmented global landscape of school acoustic standards, differing in parameters, scope, and enforceability, may further weaken the penetration of any single standard into routine practice documentation.

4.3. Open-Plan Learning Environments: Emerging Challenges and Evidence Needs

Open-plan teaching space displayed a distinctive evidence profile in this study: relatively frequent documentation (27.5% of projects) coexisted with highly heterogeneous strategy patterns. This finding warrants closer examination. Because open-plan layouts are increasingly adopted to support flexible, collaborative pedagogy, their acoustic uncertainty has become a focal point in both design guidance and policy debates.

Unlike traditional enclosed classrooms, open-plan teaching space must address multiple competing acoustic requirements: speech privacy (reducing interference from adjacent learning activities), activity-noise control (managing noise generated by multiple student groups operating simultaneously), and flexible space use (supporting acoustic transitions across different teaching modes) [10,18]. These requirements are difficult to resolve through a single dominant intervention, which likely explains the observed strategy heterogeneity. From an auditory–cognitive perspective, this heterogeneity is expected: competing speech streams can trigger the “irrelevant speech” interference mechanisms discussed in cognitive psychology [19,20], meaning that intelligible background speech may disrupt attention and short-term memory even when overall sound levels appear acceptable. Therefore, open-plan acoustic design cannot rely on reverberation-time control alone; it typically requires a coordinated package combining absorption with spatial planning (e.g., zoning/buffer strategies) to reduce speech-to-speech masking between simultaneous activities. In open environments, interference from irrelevant speech can be more disruptive than steady background noise because speech information is processed involuntarily, consuming cognitive resources required for learning tasks. Research indicates that the interference effect of irrelevant speech in open-plan environments is far more disruptive than background noise and is significantly associated with decreased work efficiency and mental health risks [64].

Recent research has raised substantial concerns regarding acoustic outcomes in open-plan classrooms. Mealings and Buchholz’s [6] scoping review found that students in open-plan classrooms developed reading fluency at significantly slower rates than students in enclosed classrooms. Rance et al.’s [21] longitudinal study further demonstrated that students in open-plan classrooms showed reading development that was 18–22 months slower than students in traditional classrooms. However, in the present sample, open-plan teaching space projects rarely reported quantitative performance data, making it difficult to verify associations between specific design strategies and learning outcomes.

The growing popularity of open-plan learning environments in contemporary school design contrasts sharply with the weakness of their acoustic evidence base. This implies that many schools are adopting a spatial model with substantial unresolved uncertainty regarding acoustic effectiveness. Future practice documentation and research should prioritise the following: (1) systematically recording successful, acoustically verified open-plan teaching space projects and their specific strategy packages; (2) developing acoustic performance evaluation approaches suitable for open environments; and (3) establishing an evidence chain linking strategy selection to learning outcomes. At present, practice-oriented guidance dedicated to open-plan teaching space remains limited, and recommended strategies have not been validated at scale.

4.4. Methodological Contribution and Transferability

The findings indicate that extending systematic mapping methods from conventional academic literature to grey literature is both feasible and valuable. By combining targeted website searching, iterative parallel screening, and structured quality appraisal, practice-based knowledge previously dispersed across professional networks can be captured in a systematic manner. This methodological framework is transferable to other building-performance domains with abundant grey literature, such as daylighting design, thermal comfort optimisation, and indoor air quality management.

Converting the AACODS checklist into a 5-point scoring scale broadens its applicability in evidence synthesis. The high agreement achieved by three independent raters (total-score ICC = 0.989) indicates that, with appropriate calibration, trained researchers can apply the criteria consistently, supporting cumulative quality appraisal in this domain. At the same time, AACODS was originally intended to assess whether an item is suitable for inclusion in a review rather than to function as a continuous quality metric; operationalising it as a quantitative score may introduce additional measurement error. The validity of this methodological choice should be further examined in future work.

The development of the space-type classification (19 categories) and the strategy taxonomy (five categories, 16 subcategories) illustrates how general acoustic-intervention frameworks can be adapted to the challenges of a specific building type. The coding framework integrates functional space classification for educational buildings [53] with a mechanism-based classification of architectural acoustic interventions [54], providing a foundational reference for subsequent research on educational building acoustics.

4.5. Study Limitations

Reliance on publicly accessible grey literature necessarily excluded internal project documentation (e.g., detailed specifications, acoustic consultant reports, and acceptance testing records) that may contain more comprehensive acoustic information. More importantly, grey literature is subject to a systematic “success bias”: organisations tend to showcase their most successful or innovative projects rather than typical projects or failures [37]. In addition, firm- and supplier-authored narratives may include promotional framing. Although this study partially mitigated these biases through multi-source linking and AACODS Objectivity scoring (Section 2.3 and Section 2.5), residual bias is likely and should be considered when generalising prevalence patterns. As a result, this study may overestimate the level of attention to acoustics in routine practice and may overstate the apparent quality of practice documentation.

The search strategy’s reliance on English- and Chinese-language sources limited coverage in other language regions (particularly Spanish, French, German, and Japanese). The relatively low representation of European projects (21.8%) may therefore reflect language constraints rather than limited activity in European practice. Future studies could improve geographic balance by extending language coverage and incorporating regional professional networks.

The space–strategy co-occurrence analysis captures “which strategies were recorded for which spaces,” but it cannot fully represent decision rationales, performance trade-offs, or contextual drivers shaping design choices. In practice, acoustic design is typically determined through multi-criteria balancing—budget constraints, aesthetic requirements, constructability, and integration with other building-performance objectives (thermal comfort, daylighting, and ventilation)—which were inevitably simplified through coding. AACODS scores reflect documentation quality rather than the actual acoustic performance of built projects. A poorly documented project may perform well acoustically, and a well-documented project may not. Accordingly, AACODS should be interpreted as an indicator of the quality of reported evidence rather than the quality of implemented design, which defines an important epistemic boundary for applying the findings.

4.6. Implications for Practice, Policy, and Research

The findings offer several actionable points for design practitioners. First, interior surface treatment strategies—particularly absorptive ceilings and absorptive wall panels—are widely used as baseline interventions and should be treated as a starting point rather than an endpoint for school acoustic design. Second, practitioners are encouraged to include more quantitative information in project documentation: design targets, simulation predictions, and, where feasible, post-completion measurements. Such documentation supports project-level knowledge management and contributes to sector-wide evidence accumulation. Third, for emerging space types such as open-plan teaching space, practitioners should treat acoustic uncertainty with caution and actively test, refine, and document context-appropriate strategy combinations.

To translate the mapping into more concrete, practice-facing outputs, we distilled the most frequently documented strategy clusters into a preliminary “strategy portfolio” template for two high-demand space types that showed relatively consistent patterns in our dataset: gymnasiums (n = 21 projects) and auditoria/performance halls (n = 13 projects) (Table 4). These templates are explicitly descriptive: they summarise what is commonly reported in grey literature and are intended as starting points for early design and documentation, not as prescriptive best-practice standards.

Table 4.

Preliminary strategy-portfolio templates distilled from the systematic mapping (case-style examples).

Given the low prevalence of quantitative reporting (Section 3.3), we propose a minimum reporting checklist for future grey literature case documentation to make practice-based evidence more actionable: (i) at least one room-acoustic metric relevant to the space function (e.g., RT for all major spaces; STI or other intelligibility-related reporting for speech-dominant spaces); (ii) background noise criteria (e.g., LAeq or NC) and whether values are targets, simulations, or post-completion measurements; (iii) key envelope/partition information where relevant (e.g., STC/Rw for partitions/doors adjacent to sensitive spaces); and (iv) the referenced standard or guideline, if any.

The findings also provide empirical input for policy development in educational building acoustics. The fact that only 7.0% of projects referenced acoustic standards suggests that voluntary uptake alone may be insufficient to ensure consistent acoustic quality in schools. Policy options include the following: (1) embedding acoustic performance requirements within school building codes or green-building certification systems; (2) incorporating acoustic testing into completion and acceptance procedures for public school projects; and (3) promoting open access to design and performance data for publicly funded educational buildings to support evidence accumulation. Jurisdictions with mandatory acoustic acceptance requirements provide potentially instructive models.

For research, this study identifies several priorities: (1) developing evidence-based acoustic design guidance tailored to open-plan learning environments as the most urgent knowledge gap; (2) expanding research on acoustic strategies for under-documented space types (e.g., gymnasiums, cafeterias, and special education facilities); (3) conducting longitudinal studies that test associations between documented strategies and measured acoustic performance; and (4) comparing acoustic practice across regulatory contexts to identify effective policy mechanisms. Methodologically, future work could explore standardised POE protocols to improve comparability of performance data, further validation of grey literature quality appraisal tools, and new models of practitioner–researcher collaboration. Future research could also explore applying soundscape assessment methods to educational spaces, establishing a soundscape perception evaluation system suitable for K–12 schools [65,66].

5. Conclusions

This systematic mapping provides the first structured analysis of grey literature on K–12 school acoustic design, synthesising 142 built projects across 22 countries from architectural firms, acoustic consultants, and material suppliers. This study contributes to the field in three respects.

First, regarding the evidence landscape (RQ1), practice documentation was concentrated in architectural firm sources (54.2%). Geographically, projects were predominantly located in North America and the Asia–Pacific region (68.3%). Temporally, most projects were completed after 2016 (64.1%). This distribution suggests growing professional attention to school acoustics while also revealing persistent imbalance in geographic coverage of practice documentation.

Second, regarding space–strategy patterns (RQ2), the analysis identified clear priorities in documentation: standard classrooms received the greatest attention, and interior surface treatment, particularly absorptive ceilings, represented the dominant intervention pathway. This study also identified open-plan teaching space as an emerging focal area in which design consensus has not yet formed, while special education facilities, stairwells, and technical classrooms appeared as systematic evidence blind spots.

Third, regarding evidence quality (RQ3), AACODS appraisal showed that documentation quality was predominantly moderate (66.9% scoring 13–18 out of 30). Material supplier sources provided comparatively more rigorous evidence (M = 17.0), followed by acoustic consultant sources (M = 15.3) and architectural firm sources (M = 14.8). Low reporting rates for quantitative performance indicators (RT: 7.0%; STI: 3.4%) and the low rate of standard referencing (7.0%) represent central constraints on the utility of current practice documentation for evidence synthesis.

The phrase “from grey to gold” captures both the current condition and the potential trajectory of practice-based evidence in school acoustic design. Grey literature—currently characterised by uneven quality, limited performance data, and weak linkage to standardised metrics—could become a valuable resource for cumulative knowledge building through coordinated efforts by practitioners, policymakers, and researchers. Such efforts would require improved documentation conventions and a more systematic feedback loop linking design intent to measured outcomes.

As K–12 school design continues to evolve—through increasing adoption of open-plan teaching space, heightened recognition of acoustic effects on student learning and teacher health, and expanding attention to indoor environmental quality—the need for robust practice-based evidence has become increasingly urgent. This systematic mapping provides both a baseline assessment of current documentation and a methodological framework for future evidence synthesis in this domain. By complementing the evidence map with a preliminary strategy-portfolio and minimum-reporting template (Table 4), this study also offers an initial mechanism for converting dispersed grey literature into more actionable practice guidance.

Future work could strengthen the strategy-to-performance evidence chain identified in this study by developing longitudinal Post-Occupancy Evaluation protocols that link design intent, measured acoustic outcomes, and student/teacher outcomes, testing multi-parameter evaluation approaches tailored to open-plan learning environments where speech-in-speech interference and privacy are central concerns, examining policy mechanisms that increase uptake and verification such as integrating acoustic testing into completion procedures or embedding requirements into school-oriented green certification systems, and expanding multilingual searching and space taxonomies to under-documented areas including special education facilities, vertical circulation, and outdoor or semi-outdoor learning spaces.

Author Contributions

X.H.: Methodology (Equal), Investigation (Equal), Formal Analysis (Lead), Writing—Original Draft (Lead). Y.Z. (Yunpeng Zhao): Investigation (Equal), Formal Analysis (Supporting), Writing—Original Draft (Supporting). X.M.: Investigation (Equal), Formal Analysis (Supporting). X.L.: Methodology (Equal), Writing—Review and Editing (Supporting). Y.Z. (Yuan Zhang): Conceptualization, Methodology (Equal), Writing—Review and Editing (Lead), Supervision, Funding Acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Y.Z. acknowledges Department of Science & Technology of Liaoning Province Project (No. 2023030045-JH2/1013).

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in Mendeley Data at https://doi.org/10.17632/pphnnjstvy.1.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work the authors used Claude-Opus-4.5 in order to proofread for minor grammar and expression imperfections. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AACODS | Authority, Accuracy, Coverage, Objectivity, Date, Significance |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| ANSI | American National Standards Institute |

| BB93 | Building Bulletin 93 |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| dBA | A-weighted Decibels |

| DIN | Deutsches Institut für Normung (German Institute for Standardization) |

| EN | Envelope/Partition |

| GB | Guobiao (Chinese National Standard) |

| HSD | Honestly Significant Difference |

| ICC | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| IS | Interior Surface |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| K–12 | Kindergarten through 12th Grade |

| M | Mean |

| n | Number |

| NC | Noise Criteria |

| NRC | Noise Reduction Coefficient |

| POE | Post-Occupancy Evaluation |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews |

| RA | Room Acoustic Elements |

| RT | Reverberation Time |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Systems and Equipment |

| SP | Spatial Planning |

| STI | Speech Transmission Index |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Search sources.

Table A1.

Search sources.

| Source Category | Organisation/Platform | URL | Country/Region |

|---|---|---|---|

| Architect | ArchDaily (International Version) | archdaily.com | USA |

| ArchDaily (Chinese version) | archdaily.cn | CN | |

| Gooood.cn | gooood.cn | CN | |

| Perkins Will Architects | perkinswill.com | USA | |

| BDP Architects | bdp.com | UK | |

| SMW LLC | smwllc.com | USA | |

| B&A Austin Architects | baiaustin.com | USA | |

| Skanska USA | usa.skanska.com | USA | |

| Policy Commons | policycommons.net | Int’l Ver. | |

| AIA Secure Platform | aia.secure-platform.com | USA | |

| Zhihu Column | zhuanlan.zhihu.com | CN | |

| CRTIA | crtia.com | CN | |

| ABD Engineering & Design | abdengineering.com | USA | |

| Commercial Acoustics | commercial-acoustics.com | USA | |

| Acoustic Consultant | Acentech | acentech.com | USA |

| Marshall Day Acoustics | marshallday.com | AU | |

| Avant Acoustics | avantacoustics.com | USA | |

| Hush Acoustics | hushacoustics.co.uk | UK | |

| Nova Acoustics | novaacoustics.co.uk | UK | |

| Guangdong Liyin Acoustics | gdliyin.com | CN | |

| Yuefa Acoustics | yuefashengxue.com | CN | |

| Acoustic CN | acousticcn.com | CN | |

| Material Supplier | Rockfon | rockfon.cn | DK |

| Ecophon | ecophon.com | SE | |

| Armstrong Ceiling Solutions | armstrongceilings.com | USA | |

| Arktura | arktura.com | USA | |

| Kirei | kireiusa.com | USA |

Table A2.

Search strategy.

Table A2.

Search strategy.

| Category | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| Building type | school, classroom, primary school, secondary school, high school, educational facility, learning environment, gymnasium, auditorium, K–12 |

| Acoustic focus | acoustics, acoustic design, sound absorption, noise control, reverberation, speech intelligibility, acoustic ceiling, acoustic panel |

Table A3.

Space type classification framework for K–12 school buildings (n = 19 types).

Table A3.

Space type classification framework for K–12 school buildings (n = 19 types).

| Category | Space Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| ST_CLRM | Standard Classroom | Standard enclosed teaching spaces |

| ST_MUSCL | Music Classroom | Dedicated music instruction spaces |

| ST_MUSBAND | Band Room | For band rehearsals |

| ST_MUSCHOIR | Choral Room | Vocal training space with good acoustics |

| ST_MUSPRAC | Practice Room | Individual/group skill practice |

| ST_OPEN | Open Learning Space | Open-plan or flexible learning environments |

| ST_LIB | Library | Libraries, media centres |

| ST_LAB | Laboratory | Science labs, maker spaces |

| ST _TECH | Technology Lab | Tech skills training |

| ST_SEN | Special Education Spaces | Special educational needs spaces |

| ST_LECTHALL | Lecture Hall | Large stadium-seated space for lectures/academic events |

| ST_AUD | Auditorium | Spacious venue with stage for assemblies/performances/awards |

| ST_THTR | Theatre | Professional space for dramas |