Abstract

As a natural building material, rammed earth has gained significant attention due to its environmental friendliness, low cost, and sustainability. This study conducted a dynamic simulation of heat and moisture transfer in rammed earth and brick buildings to compare their energy performance under identical conditions. The results indicated that the annual minimum indoor temperature in rammed earth buildings was 0.7 °C higher, while the maximum was 0.4 °C lower than that in brick buildings. The minimum and maximum indoor relative humidities were 11.4% higher and 9.6% lower, respectively, in rammed earth buildings, with an annual average of 69.2%, which is slightly lower than that of brick buildings. The annual heating and cooling energy consumption in brick buildings was 1.37 and 1.2 times greater, respectively, than in rammed earth buildings, and their monthly dehumidification demands were consistently higher. The effect of wall thickness on energy consumption revealed that increasing the thickness from 200 to 250 mm reduced energy use by 9.3%, whereas an increase from 450 to 500 mm yielded a 4.2% reduction. When the wall thickness exceeded 400 mm, the energy savings were marginal (<5%), whereas the construction costs and space occupancy increased. Therefore, a wall thickness of 350–400 mm is recommended to optimize the trade-off between energy efficiency, thermal-moisture performance, and cost-effectiveness.

1. Introduction

As a key sector in the global low-carbon transition, the construction industry has garnered significant attention owing to its substantial environmental impact, accounting for approximately 40% of the global carbon emissions [1]. Among the major challenges, energy consumption remains a critical concern and requires urgent and effective mitigation strategies [2]. The construction industry is a major contributor to both energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions worldwide [3]. In this context, China, one of the world’s leading economies, plays a pivotal role. Studies have suggested that carbon emissions from China’s construction industry can peak between 5.729 and 6.171 × 107 tce by 2030 [4]. In 2020, emissions from building construction and operations represented approximately 50% of China’s total carbon emissions, and energy demand is expected to continue to grow [5]. The rise in residential building construction, driven by rapid economic growth and urbanization, has amplified emissions. To meet its carbon neutrality target by 2060 [6], China has prioritized energy-efficient building practices, making building energy conservation a focal point for both academic research and industry innovation.

Current research on the performance of rammed earth is undergoing continuous advancements and refinement [7]. With the growing emphasis on sustainable architecture and increasing demand for environmentally friendly materials [8], studies on rammed earth have deepened significantly. Recognized for its favorable hygrothermal performance and energy-saving potential, rammed earth has attracted widespread attention in the construction sector [9,10,11]. In particular, research has focused on heat and moisture transfer processes and their implications for building energy consumption and indoor comfort. For example, Kang et al. [12] analyzed indoor hygrothermal conditions and energy consumption in passive and active buildings and validated their model through field experiments. The results indicate that replacing building exterior walls with CLT walls is a technology that can both improve indoor thermal comfort and reduce building energy consumption. Coelho et al. [13] employed WUFI Plus to simulate the effects of climate change on heat and moisture transfer in heritage structures, the results indicate that passive retrofitting methods can reduce building energy consumption, yielding significant energy savings and lowering the environmental costs incurred to maintain comfortable indoor living conditions, while Dang et al. [14] conducted the controlled hygrothermal experiments to monitor the temperature, relative humidity, heat flux, and moisture content while measuring the hygrothermal properties of the same batch of materials. Results indicate that under steady-state boundary conditions, comparing simulation results using monitored data with those employing measured material properties reveals that the WUFI Plus 2.5 software more accurately reflects the thermal and moisture transfer behavior within the wall structure. Laska et al. [15] employed WUFI Plus 2.5 to simulate the hygrothermal conditions of partition walls in single-story industrial buildings and examined the effects of different exterior wall insulation systems on the indoor hygrothermal environment. The study also detailed the modeling procedures, definition of boundary conditions, and configuration of heat sources for exterior walls. The results indicate that WUFI Plus software can be used to assess the condition of building envelopes and prevent the deterioration of building structures over time. Similarly, Radon et al. [16] used WUFI Plus to assess hygrothermal performance in Polish passive house envelopes, emphasizing the role of material properties and architectural detailing. The results indicate that the roof and wall systems used in the simulation meet thermal insulation requirements. No temporary or permanent water accumulation occurred in the simulated structure, preventing degradation of material insulation properties. This reduces the risk of indoor mold growth and lowers building energy consumption. Ge et al. [17] compared the annual air conditioning loads calculated using the equivalent U-value method and dynamic simulations performed with WUFI Plus to investigate the dynamic impact of balcony slabs as thermal bridges on the energy consumption of high-rise residential buildings. Simulation results indicate that using the equal U-value method for calculations underestimates annual heating loads by 2.8% to 4.4%. Implementing balcony thermal bridge break measures reduces annual heating loads by 8.8% to 25.7%. Although rammed earth can exhibit excellent hygrothermal behavior, its durability remains a challenge when natural binders are used exclusively [18]. Therefore, the incorporation of materials such as cement, lime, or natural fibers has emerged as a promising strategy to enhance the structural durability [19,20]. Michele et al. [21] studied the energy demand and indoor comfort of a simple building using WUFI Plus software, aided by 25 years of meteorological data from Udine, Italy. They found that changes in the environment influence the effects of coupled heat and humidity transfer in the outdoor climate. Dawei et al. [22] investigated that ignoring heat and moisture migration within the wall when setting up natural ventilation conditions leads to higher than actual indoor temperatures in summer and lower than actual indoor temperatures in winter. Yu Shui et al. [23] used WUFI Plus software to analyze the indoor heat and humidity environments and energy demand of public buildings in different climate zones and showed that heat and humidity migration is beneficial for reducing cooling energy consumption in buildings in northern China, while the opposite is true in the south. Seung et al. [24] used a heat and humidity simulation method, selected WUFI Plus software to simulate heat and humidity in the building, and used the results of the heat and humidity simulation to assess the risk of mold growth using WUFI Bio software. Mosha Zhao et al. [25] employed WUFI Plus to conduct thermal-humidity simulations on multi-zone airflow models, evaluating the energy-saving potential of deep retrofits to building envelopes. The study indicates that heating and cooling energy consumption for building envelopes can be reduced by approximately 56%. Xilei Dai et al. [26] developed the BuildingGym software, integrating EnergyPlus and RL modules. They tested BuildingGym’s operational performance for cooling loads under two objectives, demonstrating the ability to control cooling load outcomes within desired ranges. Wenzhe Shang et al. [27] employed a Modelica simulation environment to investigate the impact of different ventilation methods on energy consumption in cleanrooms. Results indicate that under identical operating conditions, the developed reinforcement learning approach achieves greater energy savings than traditional control methods, reducing operational energy consumption by 14.70% and yielding annual energy savings of approximately 11,212.8 kilowatt-hours. Shengkun Sun, Xuemin Sui, and colleagues [28,29] conducted simulation studies on insulated walls using COMSOL Multiphysics 5.5 software. They analyzed differences in thermal and moisture transfer between winter and summer seasons, revealing that condensation most readily occurs at the interface between concrete and the first layer of insulation material. Additionally, the average temperature of BIPV insulated walls increased by 3.19 °C in winter and decreased by 1.2 °C in summer. Elias Harb et al. [30] investigated the thermal-humidity performance of wall insulation structures in an office building. Results indicate that the starch/beet pulp-based insulation structure offers marginal improvements in potential energy savings but exhibits lower dynamic thermal performance. David Allinson et al. [31] employed WUFI Plus to conduct energy consumption simulations of building thermal–humidity performance, investigating the thermal–humidity characteristics of rammed earth walls in the UK. The results indicate that rammed earth walls reduce fluctuations in indoor relative humidity. Shuen Simon Sui Jiang et al. [32] researched different types of concrete, employing simulation software to analyze thermal–humidity changes in four concrete specimens. The results indicate that the thermal–humidity performance of concrete can be enhanced without compromising its mechanical properties. Hyeun Jun Moon et al. [33] compared results from wet-heat simulations with those from thermal simulations that considered only heat transfer. The findings indicate that in building energy simulations, failing to account for moisture transport mechanisms leads to an underestimation of heating and cooling energy consumption.

In this study, WUFI Plus was used to numerically simulate the hygrothermal performance and annual energy consumption of full-scale rammed earth buildings. Experimental data were adopted to validate the heat and moisture transfer processes in both the building envelope and indoor air. A comparative analysis was conducted to assess the annual energy consumption of rammed earth and brick buildings.

2. Thermal Physical Property Parameter Experiment

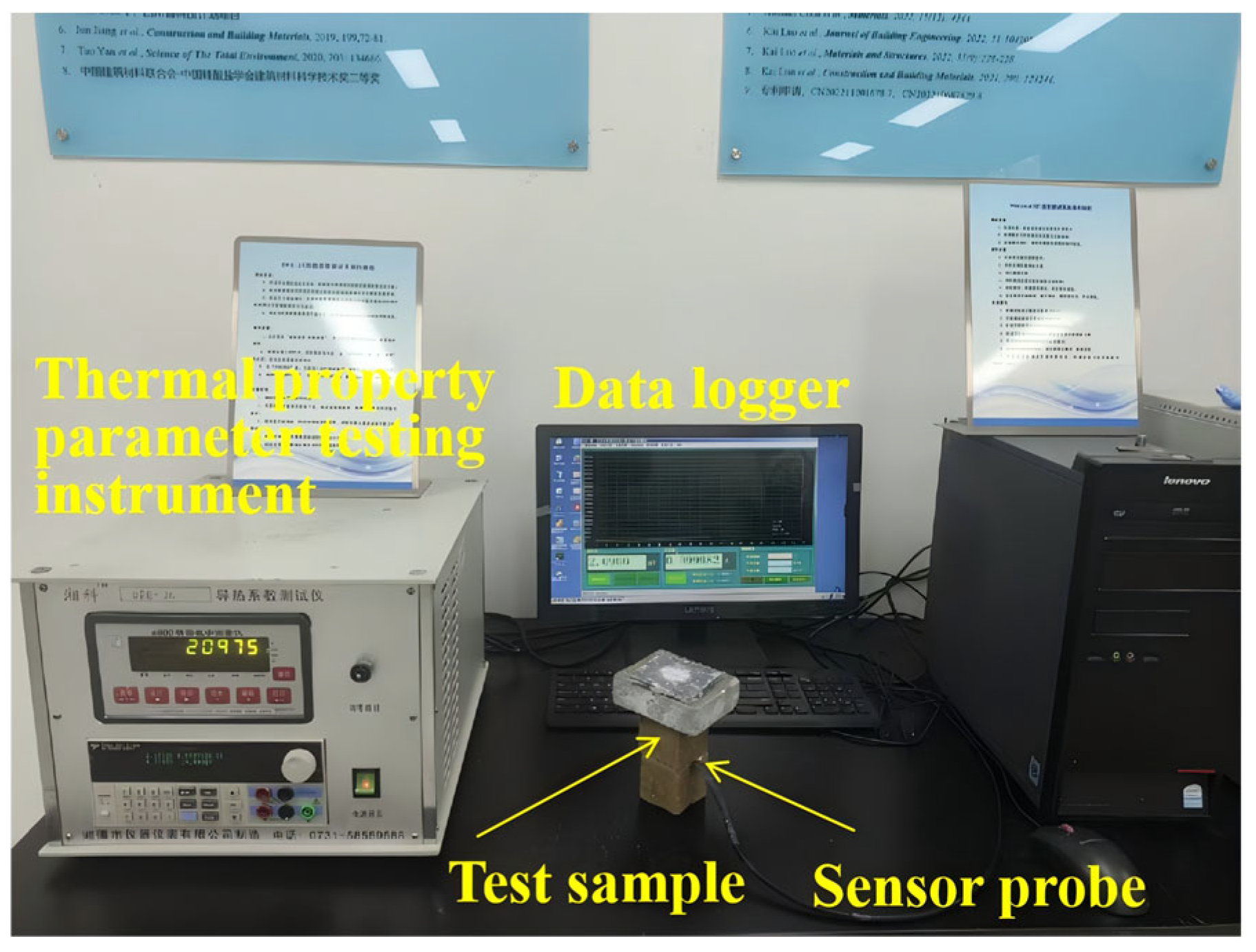

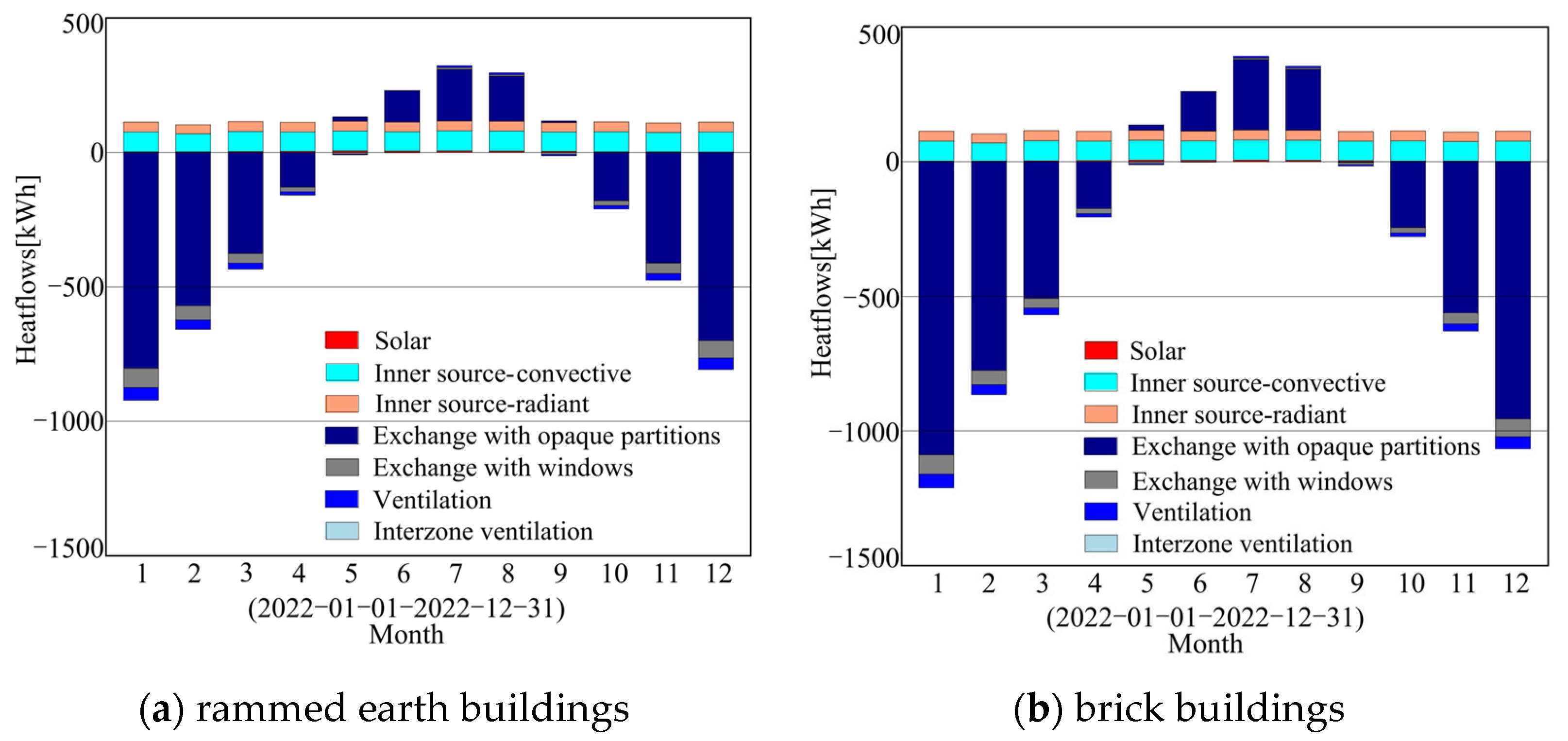

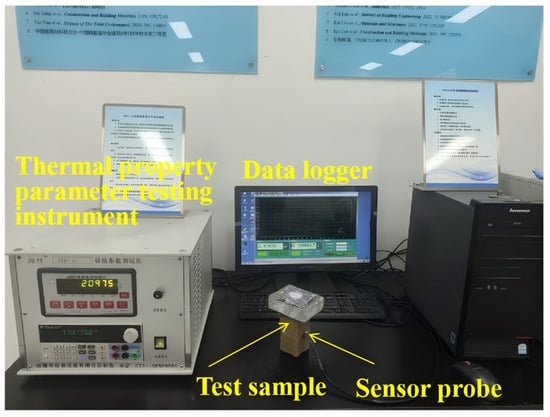

The roof of the rammed earth building was equipped with thermal insulation and waterproofing layers, while the walls were constructed using 0.37 m thick rammed earth. The thermal and moisture-related properties of the rammed earth material, including thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity, were determined through experimental measurements, with thermal conductivity, specific heat capacity, and thermal––moisture properties of the rammed earth material derived from experimental test data. First, a sample specimen was selected from the exterior wall of the rammed earth building, then cut into a 50 × 50 × 50 mm cubic specimen with a mass of 250.31 g. Its density is 2002.50 kg/m3. The testing procedures for thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity are illustrated in Figure 1. The DRE-2C Thermal Properties Tester (Xiangtan city Instruments and Meters Limited Company, Xiangtan, China) has a measurement range of 0.01–100 W/(m·K) with an accuracy of ≤±5%. The detailed parameter settings are listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Thermal physical property parameter test chart.

Table 1.

Parameter settings for rammed earth wall interface.

3. Mathematical Model

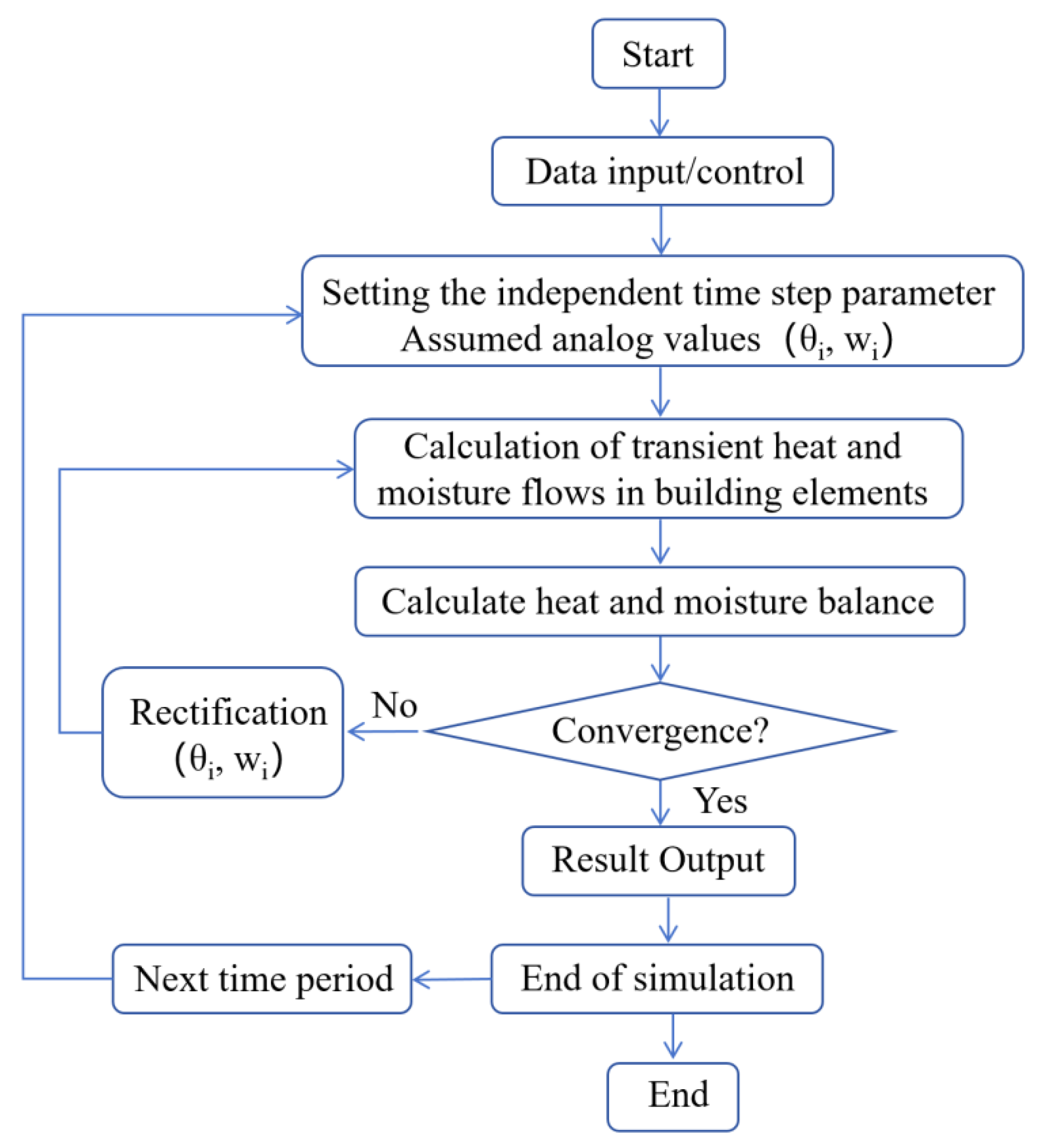

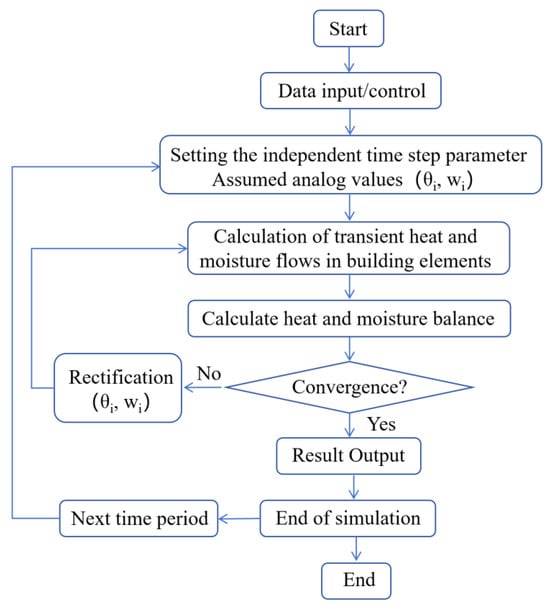

The indoor temperature and humidity can be calculated based on the heat and moisture balance, which accounts for exchanges through the building envelope, natural ventilation, and internal heat and moisture sources and sinks [34]. Accordingly, dynamic simulations of hygrothermal performance should incorporate the major building components (e.g., walls, floors, and ceilings) into a unified system. The primary transfer mechanisms include heat conduction, moisture diffusion, and capillary flow, with latent heat effects caused by phase changes driven by humidity conditions. The simulation workflow is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart for the simulation of internal climate within a freestanding building area.

Various internal sources, including those generated by occupants, lighting, HVAC systems, ventilation, and solar radiation, can significantly affect the overall heat and moisture balance within buildings when calculating heat and moisture transfer in building envelopes. The enthalpy balance equation governing the building envelope is expressed as follows:

where is the total air enthalpy in the ith zone, J; t is the time, s; is the heat flow in component j, W; is the heat flow in the indoor air or furnishings resulting from shortwave solar radiation, W; is the convective heat source within the room, W; is the ventilation heat flow, W; and is the convective heat flow from the building’s ventilation system, W.

The total air enthalpy is defined as the product of the specific enthalpy and the air mass in the ith zone.

where hi is the specific enthalpy of air in the ith zone, J/kg; and is the air mass in the ith zone, kg.

The specific enthalpy of humid air is the sum of the specific enthalpy of dry air and moisture:

where is the air temperature in the ith zone, °C; and x is the absolute humidity, kg/kg.

where x is the absolute humidity; is the atmospheric pressure, Pa; and is the partial pressure of the moisture, Pa.

The partial pressure of moisture can be derived from the saturated vapor pressure at a specific temperature and relative humidity:

where is the relative humidity; and is the temperature-dependent saturated moisture pressure, Pa.

The air mass is calculated based on the net volume and air density of the zone:

where is the indoor air density, kg/m3; and V is the net volume of the zone, m3.

The indoor air density is the sum of densities of dry air and moisture:

where is the density of dry air, kg/m3; and is the moisture density, kg/m3.

Both densities are dependent on temperature:

where is the gas constant of dry air (287.05 J/(kg∙K)); and is the absolute temperature, K.

where is the gas constant for water vapor (=461.495 J/(kgK)). The balance equation for the moisture content in the indoor air is defined as follows:

where is the total moisture content in the ith zone, kg; t is the time, s; is the moisture flow between the interior surface and indoor air, kg/s; is the moisture source within the room, kg/s; is the ventilation-induced moisture loss, kg/s; and is the ventilation-induced moisture flow, kg/s.

The total humidity balance is the product of dry air mass and absolute humidity x in the zone:

where is the mass of dry air in the zone, kg; x is the absolute humidity.

4. Simulation Parameters

4.1. Meteorological Parameters

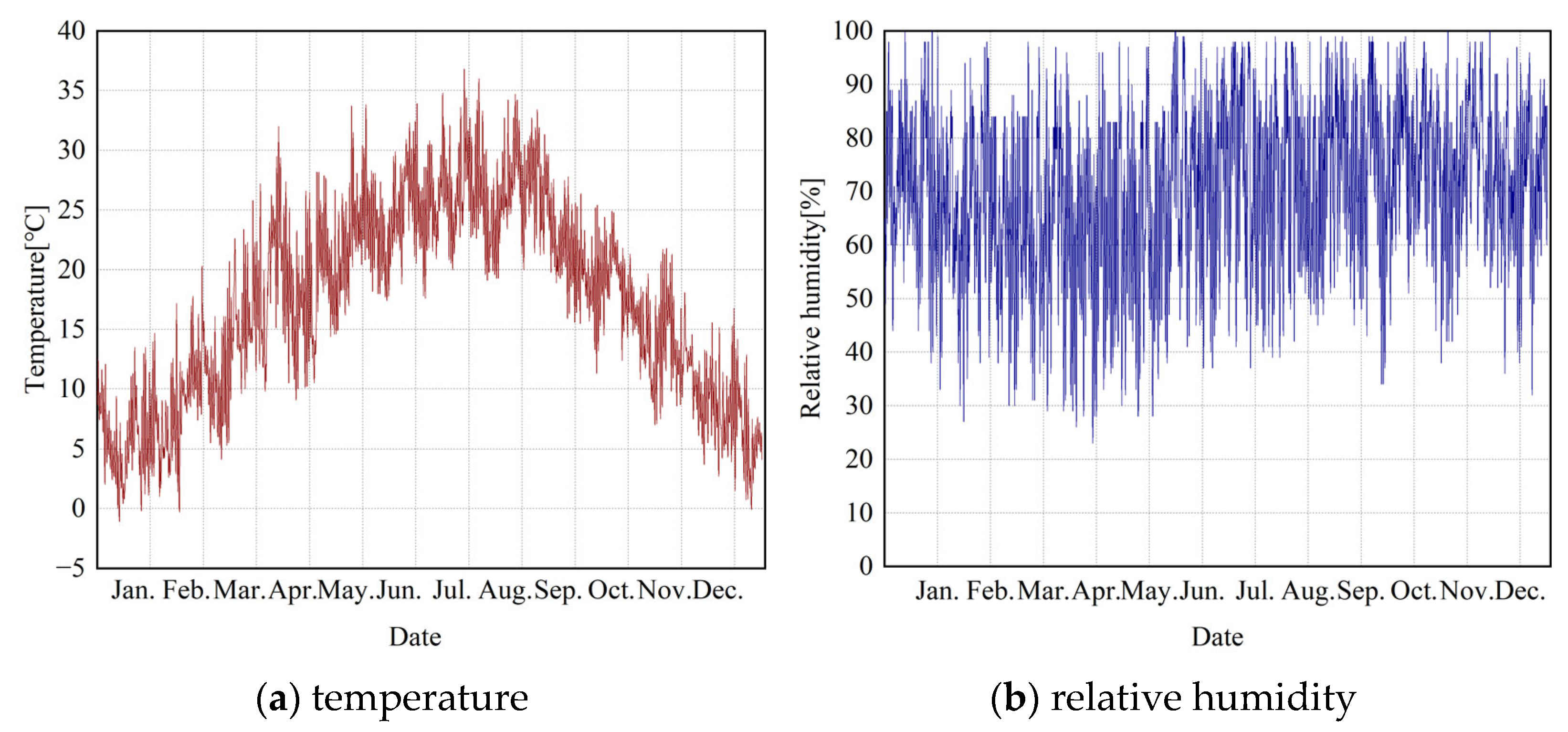

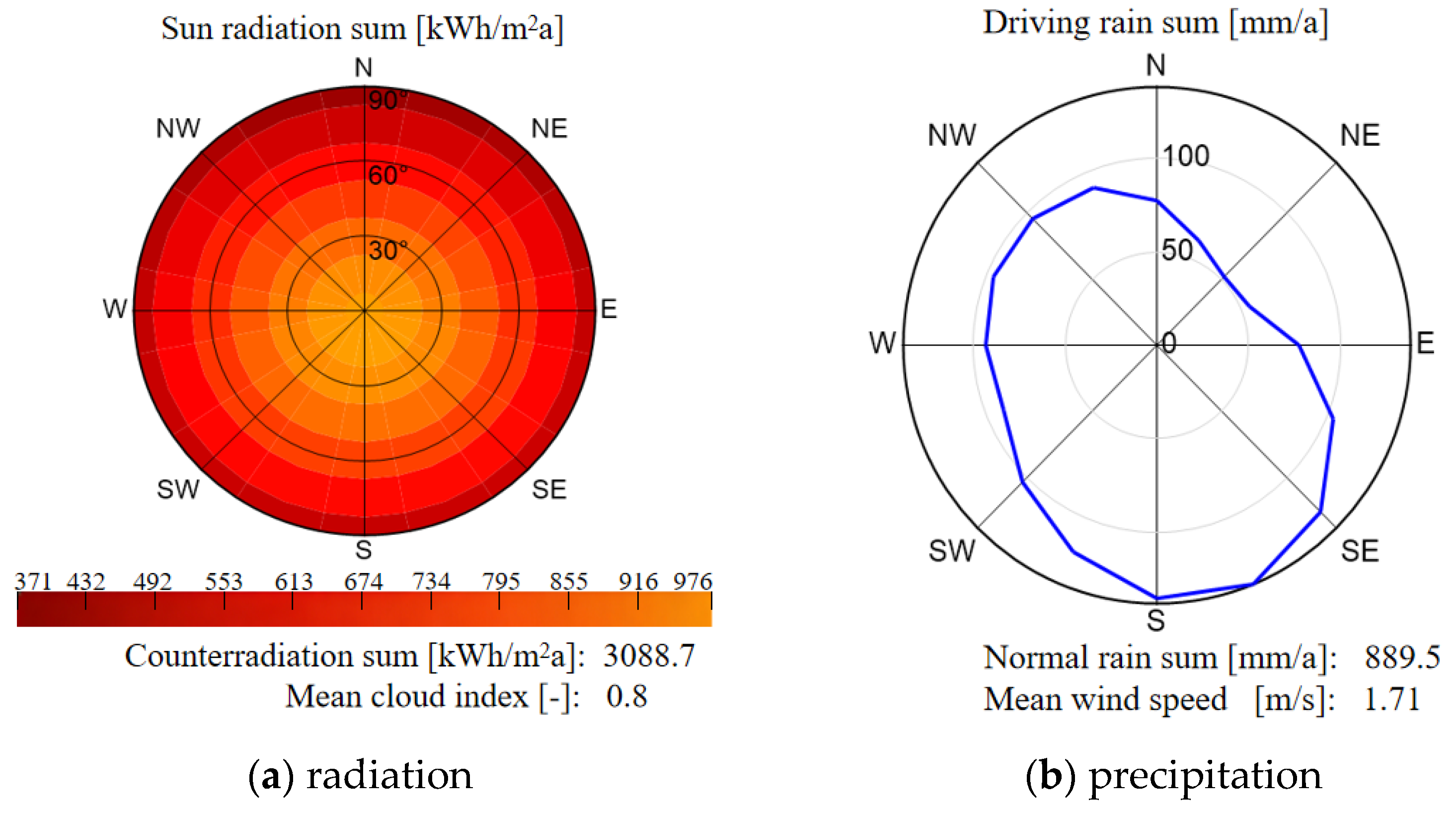

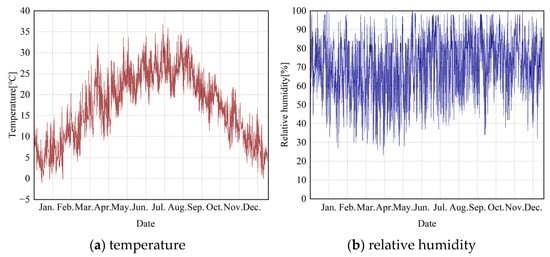

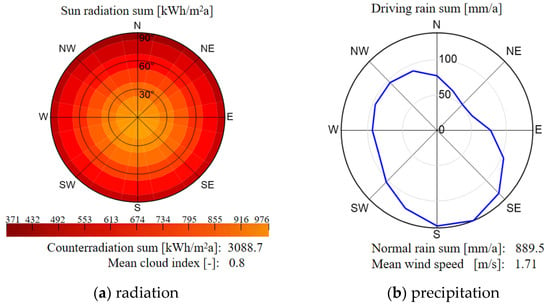

The meteorological parameters used in this study are derived from the typical meteorological year data for Mianyang City in 2022, sourced from Meteonorm. The dataset comprised nine variables, including temperature, relative humidity, solar radiation, and precipitation. The annual variations in temperature and humidity, as well as total solar radiation and precipitation, are presented in Figure 3 and Figure 4, respectively.

Figure 3.

Temperature and humidity during different months in Mianyang.

Figure 4.

Annual radiation and precipitation in Mianyang.

4.2. Geometric Dimensions and Material Parameters of Rammed Earth Buildings

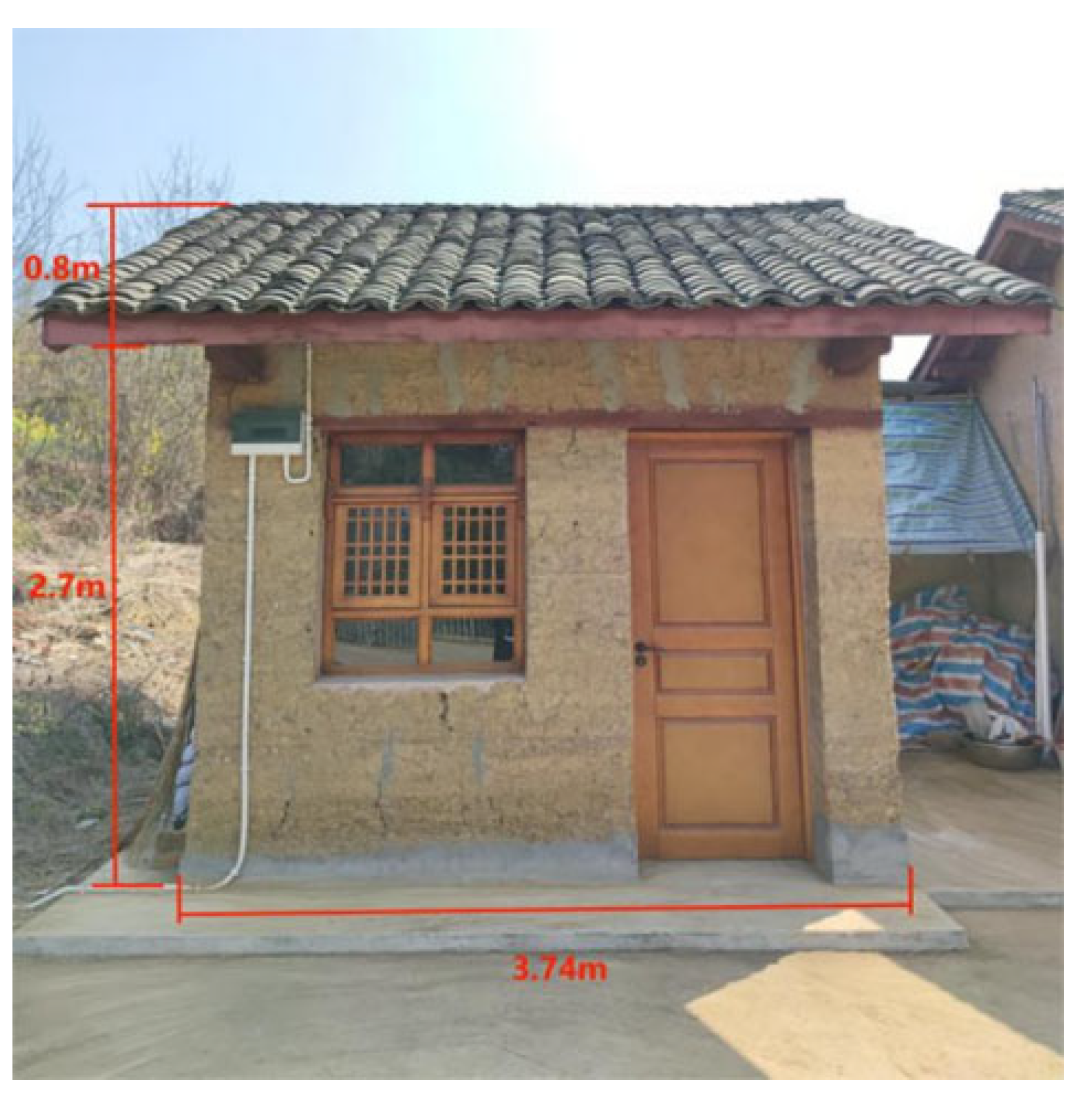

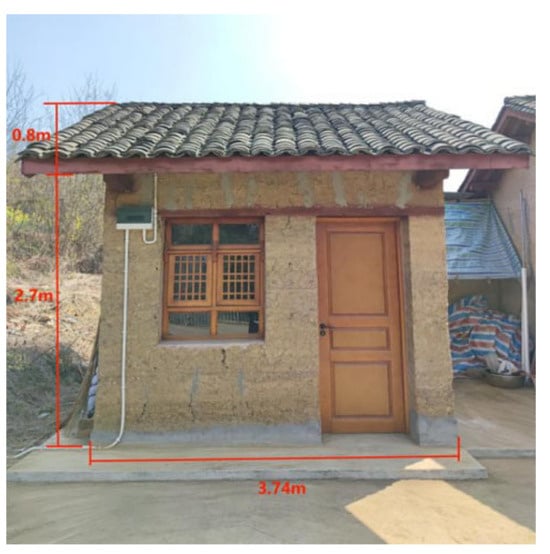

The full-scale rammed earth building was 4 m long, 3 m wide, and 3.5 m high and featured a sloped roof (Figure 5). The building was oriented to the northwest at an azimuth angle of 325°. It includes a 1.2 m2 transparent glass window and a wooden door measuring 0.9 m in width and 2.1 m in height. Specific parameters of the building envelope are detailed in Table 2 and Table 3. Temperature and humidity sensors were employed to monitor and record real-time changes in rammed earth walls. Type K thermocouples were used to measure wall temperatures and indoor/outdoor temperatures. with a measurement range of 0–1300 °C and an accuracy of ±0.5 °C. The humidity sensor utilizes Honeywell’s HIH-4000-003 model (Honeywell Inc., Charlotte, NC, USA) to detect changes in wall and indoor/outdoor humidity, featuring an accuracy of ±3.5%.

Figure 5.

Exterior dimensions of the rammed earth building.

Table 2.

Envelope parameters.

Table 3.

Wooden-framed single-pane window parameters.

4.3. Indoor Load and HVAC

- (1)

- Indoor load

According to China’s Design Code for Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning of Civil Buildings (GB50736-2012) [35], indoor occupancy was set to two adults engaged in light physical activity during working hours (08:00–18:00). The corresponding heat and moisture generation, along with the resulting indoor loads, are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Settings of indoor personnel loads.

- (2)

- Indoor HVAC

In accordance with the design code (GB50736-2012), the indoor heating, cooling, and ventilation parameters were configured. For long-term occupied zones, the thermal comfort range was set to 18–24 °C during the heating season and 24–28 °C during the cooling season, with the relative humidity maintained between 30% and 70%. When the per capita living area was below 10 m2, the minimum air change rate could not fall below 0.7 air changes per hour (ACH). The mechanical ventilation was implemented year-round to ensure the adequate indoor air quality, operating in two phases: during occupied hours (08:00–18:00), the ventilation rate was set to 0.8 ACH/h, while it was reduced to 0.4 ACH during unoccupied hours. Table 5 summarizes the HVAC settings.

Table 5.

Settings of indoor HVAC.

5. Model Validation

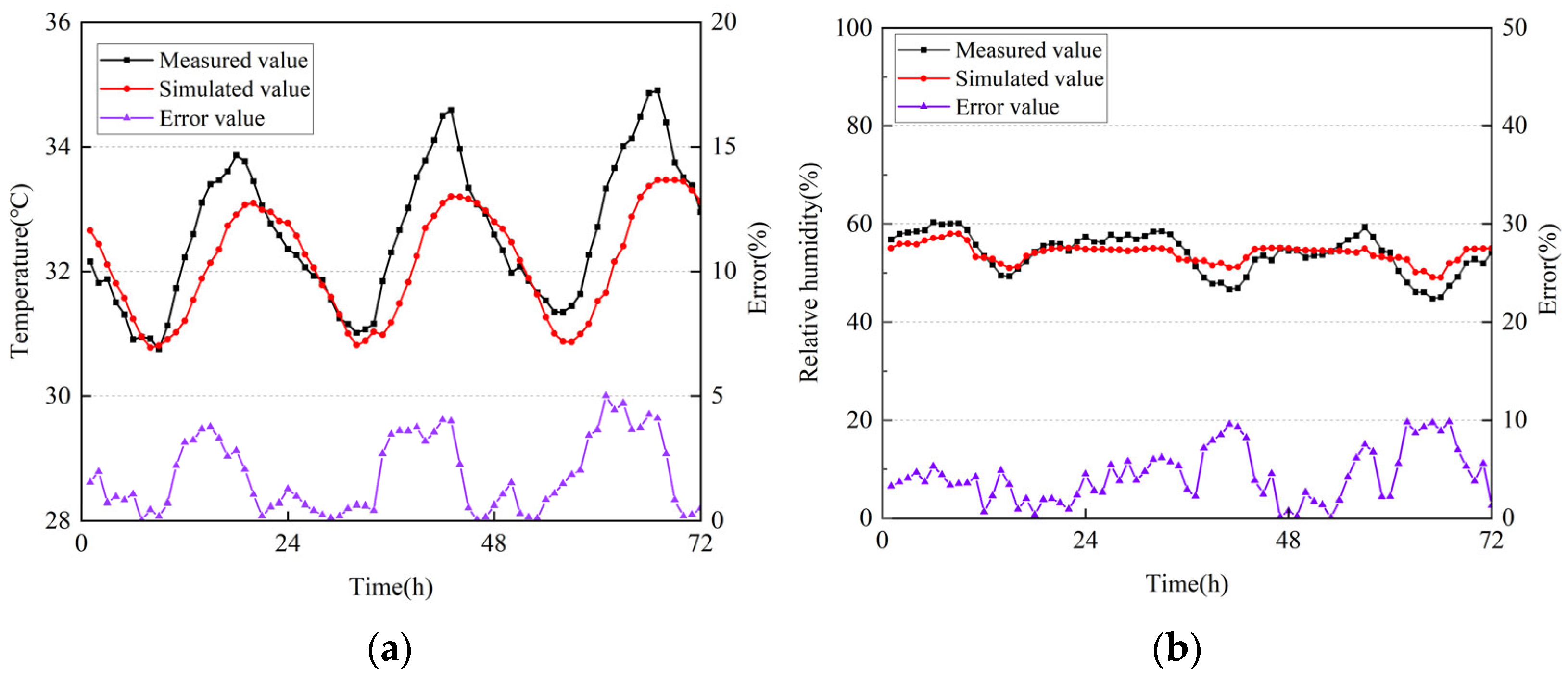

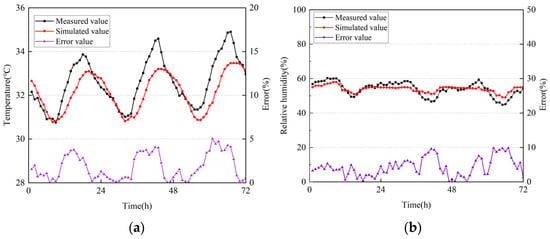

The measured data collected from 13 to 15 August 2022 were used to validate the simulation, with the outdoor climatic parameters (e.g., temperature, humidity, radiation, and precipitation) serving as the external boundary conditions. The simulated indoor temperature and relative humidity were compared with the measured values [36,37], and the deviations were calculated using Equation (12). As shown in Figure 6, the simulation results closely aligned with the experimental data. The maximum and mean deviations in indoor temperature were 1.67 °C and 0.61 °C, respectively, with all the errors remaining below 5% and an average error of 1.8%. For the relative humidity, the maximum and mean deviations were 4.7% and 2.29%, respectively, with an average error of 4.3%, and all deviations remained within 10%.

where e was the error, %; was the measured value; and was the simulated value.

Figure 6.

Validation of simulation and measurement results: (a) temperature and (b) relative humidity.

6. Results and Discussion

As a traditional building material, rammed earth offers notable advantages such as cost-effectiveness, availability, and environmental sustainability. Under identical outdoor climatic conditions, the energy consumption of a building reflects the thermal and hygric performance of its envelope structure for maintaining indoor comfort. In this study, the annual heat and moisture transfer performance and HVAC energy consumption of brick and rammed earth buildings were compared using WUFI Plus simulation.

6.1. Heat and Moisture Transfer by Walls

In the simulation, only the indoor occupancy parameters and associated heat and moisture loads were configured. The meteorological conditions were based on the typical meteorological year data for Mianyang. For consistency, the wall thickness for both rammed earth and brick structures was set to 370 mm (Table 6). The parameters of rammed earth were obtained through experimental measurements [38], whereas those of bricks were sourced from the WUFI Plus built-in material database.

Table 6.

Thermophysical parameters of different building walls.

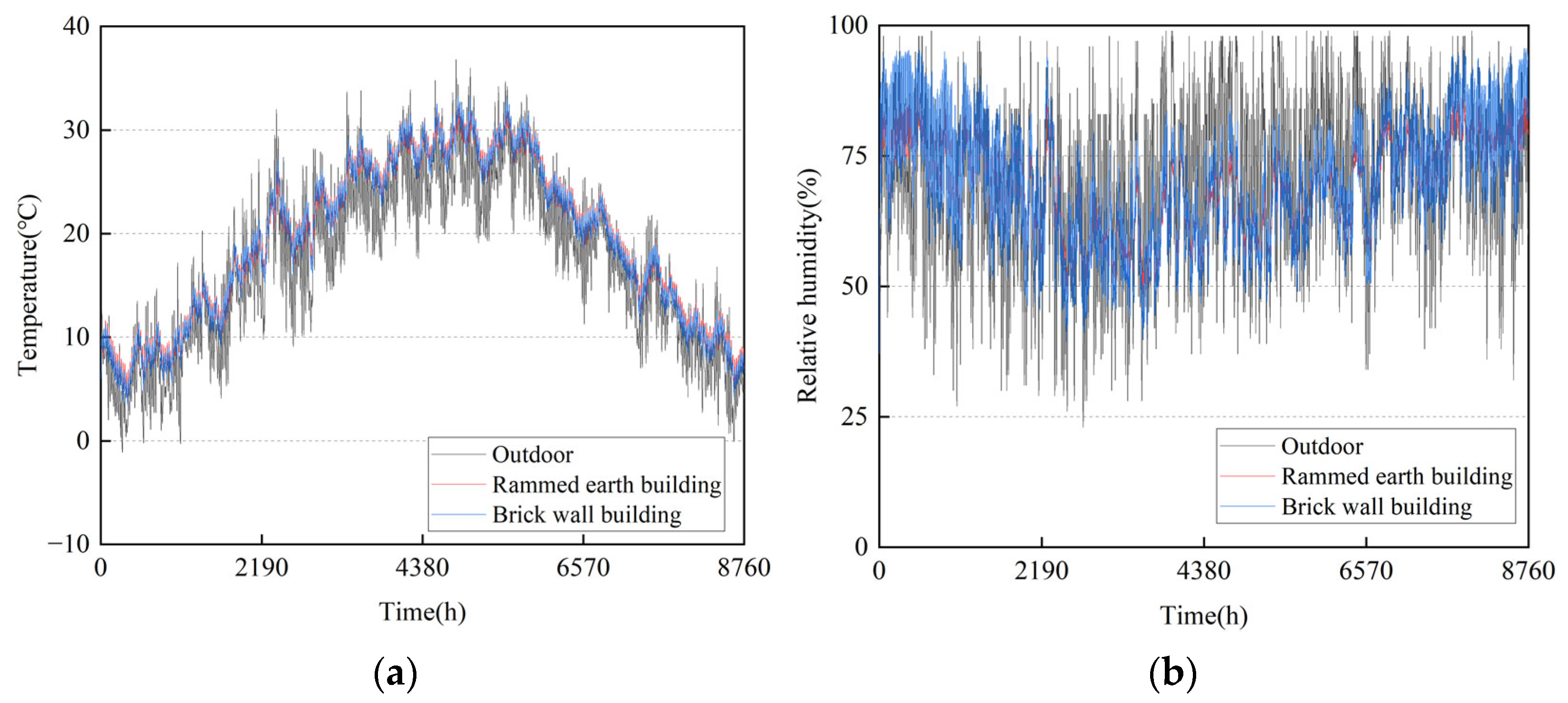

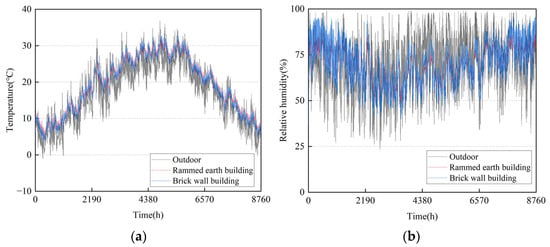

Figure 7 presents the variations in inner surface temperature and relative humidity for both wall types. Under identical outdoor climatic conditions, the rammed earth walls exhibited smaller fluctuations in surface temperature and humidity than brick walls, indicating superior hygrothermal stability. Notably, during summer, the inner surface temperature of rammed earth walls was lower than that of brick walls, whereas in winter, it was slightly higher. These results suggest that rammed earth walls could offer enhanced thermal inertia, improving indoor comfort throughout the year.

Figure 7.

Inner surface parameters of brick buildings and rammed earth buildings: (a) temperature and (b) relative humidity.

Table 7 summarizes the simulated indoor temperature and humidity results for rammed earth and brick buildings. The minimum and maximum annual indoor temperatures in rammed earth buildings were 0.7 °C higher and 0.4 °C lower, respectively, than those in brick buildings. The annual average indoor relative humidity in rammed earth buildings was 69.2%, which was slightly lower than that in brick buildings. Furthermore, the minimum and maximum relative humidity values in rammed earth buildings were 11.4% higher and 9.6% lower, respectively, than those in brick buildings. These findings suggest that in the humid climate of northwestern Sichuan, rammed earth buildings offer superior passive regulation of indoor temperature and humidity, enhancing overall thermal comfort.

Table 7.

Indoor temperature and humidity of rammed earth buildings and brick buildings.

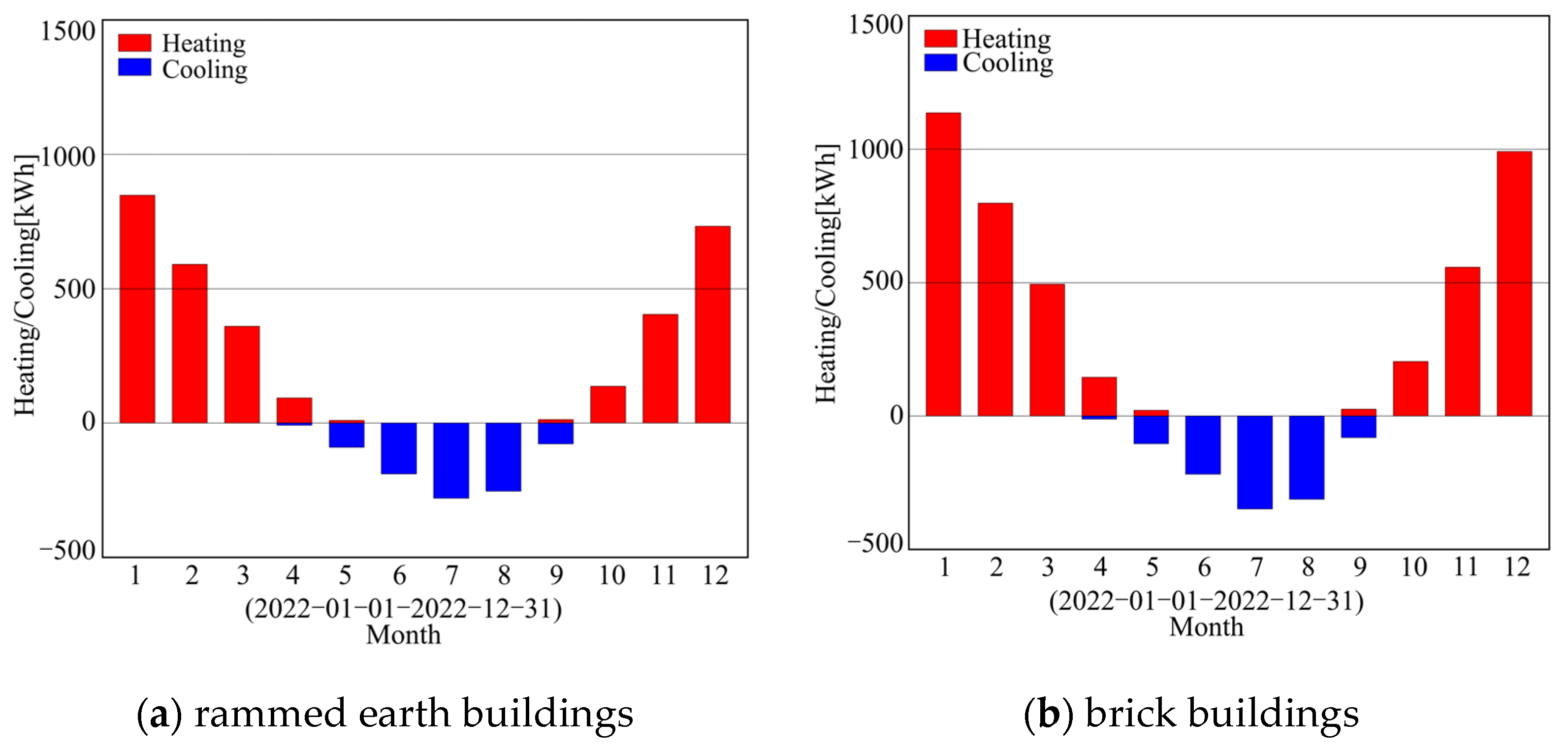

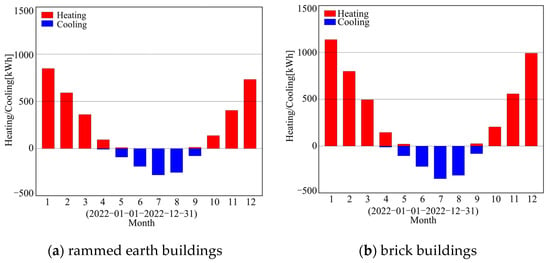

6.2. Annual Energy Consumption for Heating and Cooling

In the simulations, both rammed earth buildings and brick buildings were equipped with air conditioning systems that incorporated year-round mechanical ventilation, humidification, and dehumidification. Based on the annual energy consumption for heating and cooling, as well as the wall-related heat gains and losses, the energy-saving performance of the two building types was assessed. As shown in Figure 8 and Table 8, the annual heating and cooling energy consumption of brick buildings were 1.37 and 1.20 times higher, respectively, than that of rammed earth buildings. These results indicate that rammed earth buildings require significantly less energy to maintain the same indoor thermal and humidity conditions, thereby demonstrating superior energy efficiency.

Figure 8.

Monthly energy consumption by buildings for heating and cooling.

Table 8.

Annual energy consumption of rammed earth buildings and brick buildings for heating and cooling.

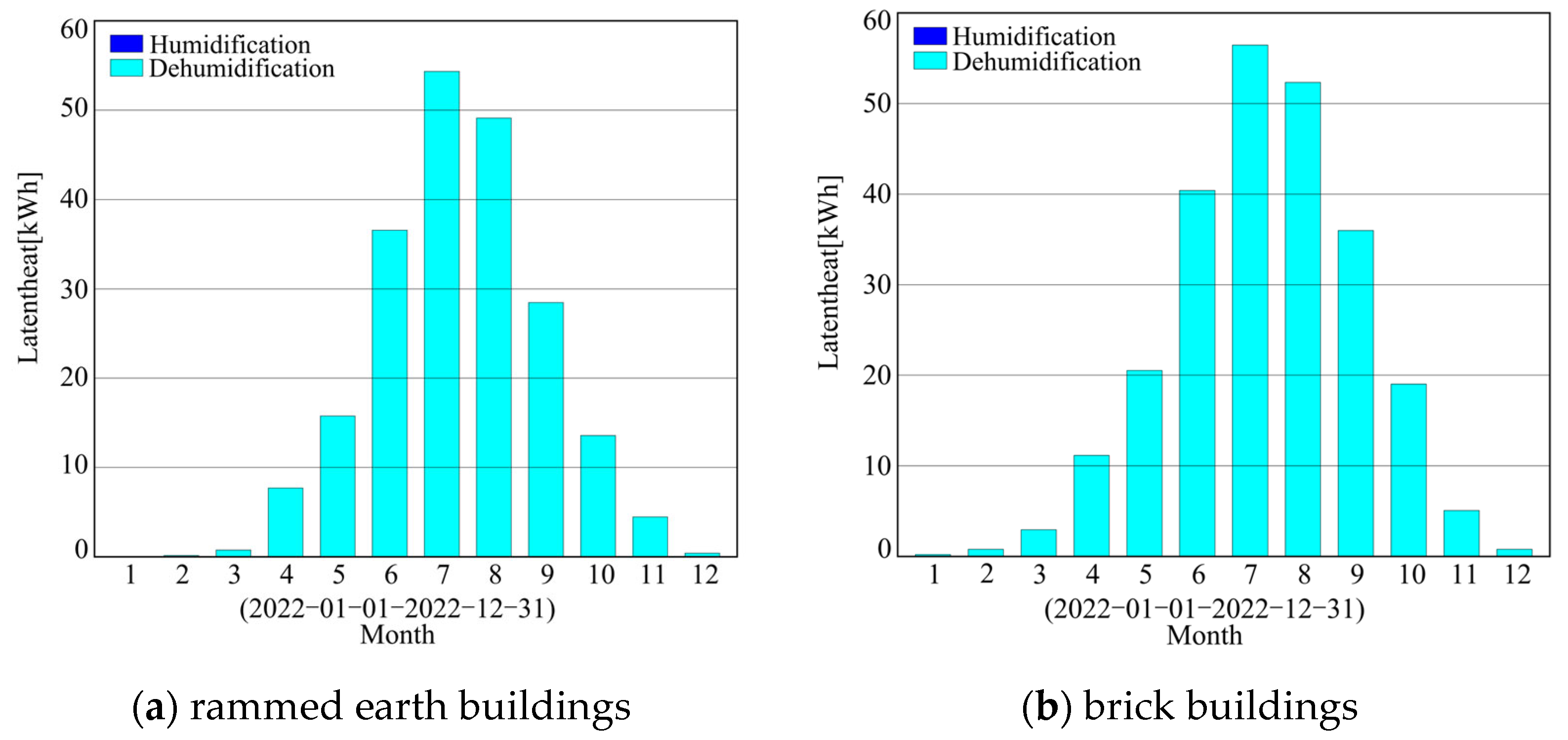

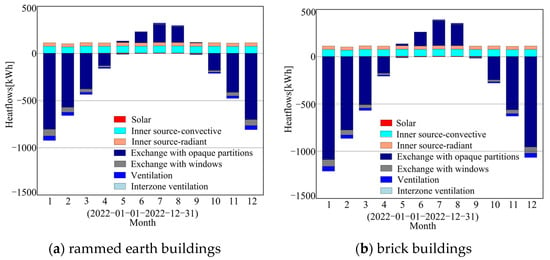

6.3. Monthly Heat Flow

Figure 9 presents the monthly heat flow profiles for both rammed earth and brick buildings, where positive values represent heat release and negative values denote heat absorption. The results demonstrated that the annual total heat flow of rammed earth buildings was significantly lower than that of brick buildings. Among all building components, the heat exchange between indoor air and opaque partitions constituted the largest proportion of heat flow. Notably, the rammed earth walls exhibited the lowest heat transfer, indicating superior thermal insulation performance compared with brick walls.

Figure 9.

Monthly heat flows of rammed earth buildings and brick buildings.

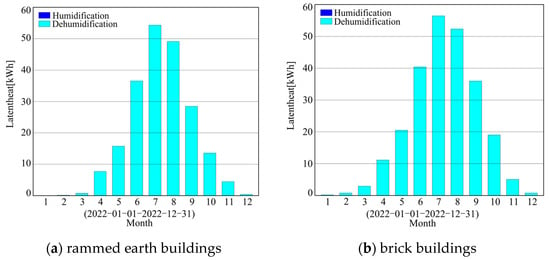

Figure 10 illustrates the monthly latent heat exchanges for rammed earth and brick buildings, where positive and negative values represent dehumidification and humidification, respectively. Located in northwestern Sichuan, the study area experiences hot summers, cold winters, and consistently high humidity levels throughout the year. Accounting for indoor moisture loads, the air conditioning system operates year-round to maintain indoor humidity through dehumidification. Although rammed earth and brick buildings can exhibit similar monthly dehumidification trends, rammed earth buildings require significantly less dehumidification, indicating superior humidity regulation performance. This may reduce the latent heat load of buildings.

Figure 10.

Monthly humidification and dehumidification capacities of rammed earth buildings and brick buildings.

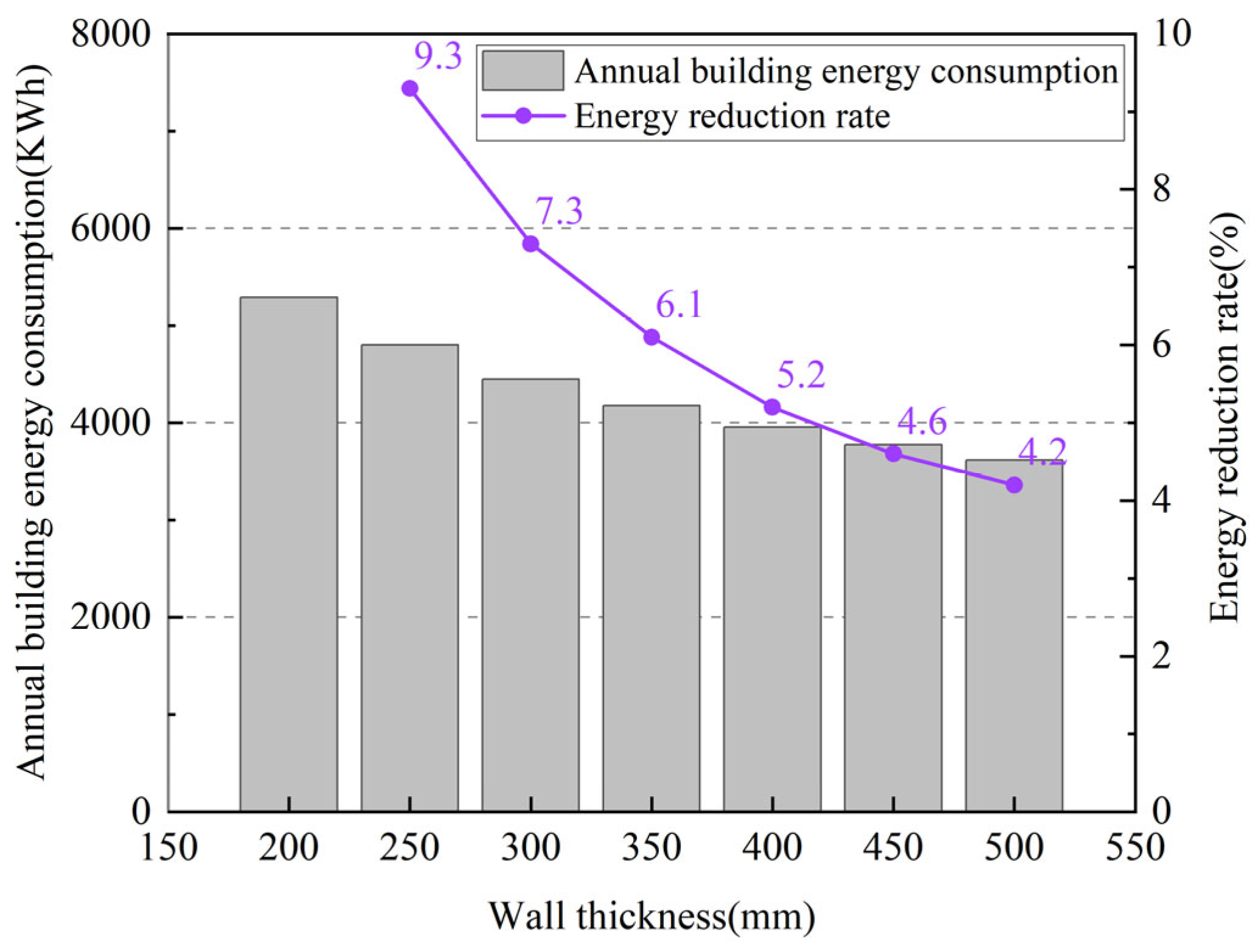

6.4. Effects of Wall Thickness on Energy Consumption by Buildings

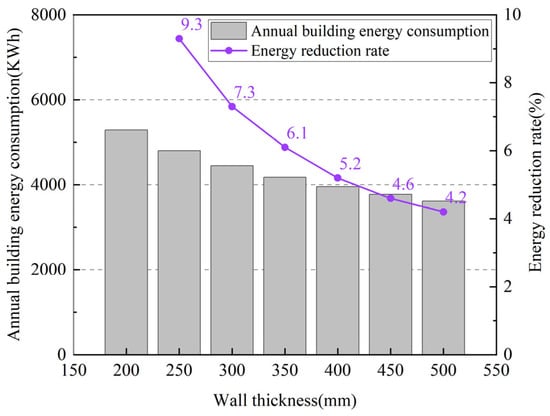

Wall thickness plays a critical role in determining the structural and functional performance of buildings, including their thermal and acoustic insulation properties [39]. While thicker walls generally offer improved structural integrity [40], they also increase building mass and construction costs. Because brick buildings are widely used, the impact of wall thickness on their energy consumption has been extensively studied. Therefore, this study focused only on evaluating the influence of wall thickness on the energy performance of rammed earth buildings through numerical simulations. Seven wall thickness values ranging from 200 to 500 mm in 50 mm increments were analyzed. The simulation results are presented in Figure 11 and Table 9. The energy savings associated with each incremental increase in the wall thickness were calculated using Equation (13). When the wall thickness increased from 200 to 250 mm, the energy consumption decreased by 9.3%. However, the reduction was only 4.2% when the thickness was increased from 450 to 500 mm. Overall, the energy savings diminished when the wall thickness exceeded 400 mm, with further increases yielding minimal benefits while contributing to higher construction costs and reduced interior space efficiency. Conversely, insufficient wall thickness may compromise the structural stability and increase energy consumption. Based on these findings, a wall thickness of 350–400 mm is recommended to balance energy efficiency, structural safety, and cost-effectiveness in rammed earth construction.

where R is the energy consumption reduction rate (%); E1 is the annual energy consumption of the previous thickness gradient (kWh); and E2 is the annual energy consumption of the subsequent thickness gradient (kWh).

Figure 11.

Energy consumption and energy consumption reduction rates of buildings with different wall thicknesses.

Table 9.

Annual energy consumption and energy consumption reduction rates of buildings with different wall thicknesses.

7. Conclusions

In this study, WUFI Plus was employed to conduct numerical simulations of heat and moisture transfer performance as well as the annual energy consumption in full-scale rammed earth and brick buildings. The simulation results for the building envelope and indoor air conditions were validated using experimental data. Based on these findings, the following conclusions were drawn.

- (1)

- Under indoor personnel load conditions without air conditioning, rammed earth buildings exhibited superior hygrothermal performance compared with brick buildings. Specifically, the minimum and maximum indoor temperatures were 0.7 °C higher and 0.4 °C lower, respectively, in rammed earth buildings. The annual average indoor temperature reached 19.3 °C, slightly exceeding that of brick buildings. In terms of humidity, the rammed earth buildings demonstrated an 11.4% higher minimum and 9.6% lower maximum indoor relative humidity, with an annual average of 69.2%, which is marginally lower than that in brick buildings. The dynamic simulation results confirmed that rammed earth buildings maintained a more stable indoor hygrothermal environment. Overall, the warmer and drier indoor conditions provided by rammed earth contributed to improved thermal comfort throughout the year.

- (2)

- With HVAC systems implemented, the annual energy consumption for heating and cooling in brick buildings was 1.37 and 1.20 times higher, respectively, than that of rammed earth buildings under identical indoor temperature and humidity settings. Moreover, the monthly dehumidification demand in brick buildings exceeded that in rammed earth buildings throughout the year. These results highlight the ability of rammed earth buildings to maintain comfortable indoor hygrothermal conditions with lower energy input, demonstrating their superior energy-saving performance.

- (3)

- As the wall thickness increased, the energy consumption reduction rate of rammed earth buildings gradually declined, falling below 5% when the thickness exceeded 400 mm. Therefore, considering energy efficiency, structural safety, and cost-effectiveness, a rammed earth wall thickness of 350–400 mm is recommended.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.J.; Data curation, M.J.; Funding acquisition, B.J.; Formal analysis, K.H. and M.J.; Investigation, K.H. and L.W.; Methodology, B.J. and L.W.; Supervision, B.J.; Visualization, L.W.; Writing—original draft, K.H.; Writing—review & editing, M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52078439). Southwest University of Science and Technology Graduate Innovation Fund (No. 25YCX1090).

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| Hi | the total air enthalpy in the ith zone (J) | R | the energy consumption reduction rate (%) |

| t | the time (s) | E1 | the annual energy consumption of the previous thickness gradient (kWh) |

| QComp,j | the heat flow in component j (W) | E2 | the annual energy consumption of the subsequent thickness gradient (kWh) |

| QSol | the heat flow in the indoor air or furnishings resulting from shortwave solar radiation (W) | Greek symbols | |

| QIn | the convective heat source within the room (W) | θi | the air temperature in the ith zone (°C) |

| QVent | the ventilation heat flow (W) | φ | the relative humidity |

| QHVAC | the convective heat flow from the building’s ventilation system (W) | ρ | the indoor air density (kg/m3) |

| hi | the specific enthalpy of air in the ith zone (J/kg) | ρa | the density of dry air (kg/m3) |

| mi | the air mass in the ith zone (°C) | ρw | the moisture density (kg/m3) |

| x | the absolute humidity (kg/kg) | θ | the absolute temperature (K) |

| Pb | the atmospheric pressure (Pa) | Subscripts | |

| Pp | the partial pressure of the moisture (Pa) | i | ith |

| Pa(φ) | the temperature-dependent saturated moisture pressure (Pa) | Comp,j | component j |

| V | the net volume of the zone (m3) | Sol | shortwave solar radiation |

| Ra | the gas constant of dry air (287.05 J/(kg∙K)) | In | within the room |

| Rw | the gas constant for water vapor (=461.495 J/(kgK)) | b | the atmospheric pressure |

| Ci | the total moisture content in the ith zone (kg) | p | partial pressure |

| WComp,j | the moisture flow between the interior surface and indoor air (kg/s) | a | the gas constant of dry air |

| Win | the moisture source within the room (kg/s) | w | water vapor |

| WVent | the ventilation-induced moisture loss (kg/s) | Vent | the ventilation-induced moisture loss |

| WHVAC | the ventilation-induced moisture flow (kg/s) | HVAC | the ventilation-induced moisture flow |

| Mi | the mass of dry air in the zone (kg) | m | the measured value |

| e | the error (%) | s | the simulated value |

| ym | the measured value | 1 | the annual energy consumption of the previous |

| ys | the simulated value | 2 | the annual energy consumption of the subsequent |

References

- Ma, Y.; Deng, W.; Xie, J.; Heath, T.; Izu Ezeh, C.; Hong, Y.; Zhang, H. A macro-scale optimisation of zero-energy design schemes for residential buildings based on building archetypes. Sol. Energy 2023, 257, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayeh, B.; Hadzima-Nyarko, M.; Riad, M.Y.; Hafez, R.D. Behavior of Ultra-High-Performance Concrete with Hybrid Synthetic Fiber Waste Exposed to Elevated Temperatures. Buildings 2023, 13, 129. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdeau, M.; Zhai, X.Q.; Nefzaoui, E.; Guo, X.; Chatellier, P. Modeling and forecasting building energy consumption: A review of data-driven techniques. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 48, 101533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, J. Building carbon peak scenario prediction in China using system dynamics model. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 96019–96039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Tam, V.W.Y.; Almeida, L.; Le, K.N. Dynamically assessing life cycle energy consumption of buildings at a national scale by 2020: An empirical study in China. Energy Build. 2023, 296, 113354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Gao, Q.; Shao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Bao, Y.; Zhao, L. Carbon emission scenarios of China’s construction industry using a system dynamics methodology—Based on life cycle thinking. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 435, 140457. [Google Scholar]

- Khrissi, Y.; Tilioua, A.; Laaroussi, N.; Bybi, A. Recycling date palm waste in a gypsum-based composite: Experimental study of thermal, acoustic, mechanical and hydric performance. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2025, 10, 312. [Google Scholar]

- Barbhuiya, S.; Adak, D.; Marthong, C.; Forth, J. Sustainable solutions for low-cost building: Material innovations for Assam-type house in North-East India. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04461. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz, L.P.; Gosslar, J.; Dorresteijn, E.; Lowke, D.; Kloft, H. Experimental investigations on the compaction energy for a robotic rammed earth process. Front. Built Environ. 2024, 10, 1363804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrissi Kaitouni, S.; Charai, M.; Es-sakali, N.; Mghazli, M.O.; El Mankibi, M.; Uk-Joo, S.; Ahachad, M.; Brigui, J. Energy and hygrothermal performance investigation and enhancement of rammed earth buildings in hot climates: From material to field measurements. Energy Build. 2024, 315, 114325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losini, A.E.; Grillet, A.-C.; Vo, L.; Dotelli, G.; Woloszyn, M. Biopolymers impact on hygrothermal properties of rammed earth: From material to building scale. Build. Environ. 2023, 233, 110087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Jo, H.H.; Kim, S. Enhancing indoor comfort and building energy efficiency with cross-laminated timber (CLT) in hygrothermal environments. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 84, 108582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, G.B.A.; Entradas Silva, H.; Henriques, F.M.A. Impact of climate change in cultural heritage: From energy consumption to artefacts’ conservation and building rehabilitation. Energy Build. 2020, 224, 110250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, X.; Janssen, H.; Roels, S. Hygrothermal Modelling of one-dimensional Wall Assemblies: Inter-model Validation between WUFI and DELPHIN. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2654, 012040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laska, M.; Małyszko, M. Modeling of Hydro-Thermal Conditions in the External Walls of a Single-Family Building with Utilization of WUFI Plus Software; Ciepłownictwo, Ogrzewnictwo, Wentylacja: Warszawa, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Radon, J.; Was, K.; Flaga-Maryanczyk, A.; Schnotale, J. Experimental and theoretical study on hygrothermal long-term performance of outer assemblies in lightweight passive house. J. Build. Phys. 2018, 41, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, F.; Ge, H. Dynamic effect of balcony thermal bridges on the energy performance of a high-rise residential building in Canada. Energy Build. 2016, 116, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umubyeyi, C.; Wenger, K.; Dahmen, J.; Ochsendorf, J. Durability of unstabilized rammed earth in temperate climates: A long term study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 409, 133953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadianfard, S.; Toufigh, V. Stabilization effect on the hygrothermal performance of rammed earth materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 409, 134025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezannia, A.; Gocer, O.; Bashirzadeh Tabrizi, T. The life cycle assessment of stabilized rammed earth reinforced with natural fibers in the context of Australia. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 416, 135034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libralato, M.; De Angelis, A.; Tornello, G.; Saro, O.; D’Agaro, P.; Cortella, G. Evaluation of Multiyear Weather Data Effects on Hygrothermal Building Energy Simulations Using WUFI Plus. Energies 2021, 14, 7157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, D.; Zhong, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zou, Y.; Lou, S.; Zhan, Q.; Guo, J.; Yang, J.; Guo, T. Impact of coupled heat and moisture transfer on indoor comfort and energy demand for residential buildings in hot-humid regions. Energy Build. 2023, 288, 113029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Cui, Y.; Shao, Y.; Han, F. Simulation Research on the Effect of Coupled Heat and Moisture Transfer on the Energy Consumption and Indoor Environment of Public Buildings. Energies 2019, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.H.; Moon, H.J.; Kim, J.T. Evaluation of the influence of hygric properties of wallpapers on mould growth rates using hygrothermal simulation. Energy Build. 2015, 98, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Mehra, S.-R.; Künzel, H.M. Energy-saving potential of deeply retrofitting building enclosures of traditional courtyard houses—A case study in the Chinese Hot-Summer-Cold-Winter zone. Build. Environ. 2022, 217, 109106. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, X.L.; Chen, R.T.; Guan, S.Z.; Li, W.T.; Yuen, C. BuildingGym: An open-source toolbox for AI-based building energy management using reinforcement learning. Build. Simul. 2025, 18, 1909–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, W.Z.; Liu, J.J.; Meng, H.; Jia, L.Z.; Dai, X.L. A RL-based human behavior oriented optimal ventilation strategy for better energy efficiency and indoor air quality. Energy Build. 2025, 345, 116072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.K.; Liu, Y.; Yu, S.; Han, F.H.; Kong, Z.L. Experimental and simulation study of air-cooled BIPV wall thermal performance in cold regions under coupled heat-moisture-stress effects. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 112, 113785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, X.; An, M.Y.; Cui, H.R. Investigation of condensation behavior in self-insulating recycled concrete composite block walls. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 107, 112653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harb, E.; Maalouf, C.; Bliard, C.; Kinab, E.; Lachi, M.; Polidori, G. Hygrothermal performance of multilayer wall assemblies incorporating starch/beet pulp in France. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 445, 137773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allinson, D.; Hall, M. Hygrothermal analysis of a stabilised rammed earth test building in the UK. Energy Build. 2010, 42, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui Jiang, S.S.; Hao, J.L.; De Carli, J.N. Hygrothermal and mechanical performance of sustainable concrete: A simulated comparison of mix designs. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 34, 101859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.J.; Ryu, S.H.; Kim, J.T. The effect of moisture transportation on energy efficiency and IAQ in residential buildings. Energy Build. 2014, 75, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palani, H.; Khaleghi, H.; Salehi, P.; Karatas, A. Assessing Hygrothermal Performance in Building Walls Engineered for Extreme Cold Climate Environments. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB50736-2012; Code for Design of Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning in Civil Buildings (Explanatory Notes): [S]. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Conroy, A.; Mukhopadhyaya, P.; Wimmers, G. In-Situ and Predicted Performance of a Certified Industrial Passive House Building under Future Climate Scenarios. Buildings 2021, 11, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staszczuk, A.; Kuczyński, T.; Wojciech, M.; Ziembicki, P. Comparative Calculation of Heat Exchange with the Ground in Residential Building Including Periodes of Heat Waves. Civ. Environ. Eng. Rep. 2016, 21, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jiang, M.Q.; Jiang, B.; Lu, R.; Chun, L.; Xu, H. Thermal and Humidity Performance Test of Rammed-Earth Dwellings in Northwest Sichuan during Summer and Winter. Materials 2023, 16, 6283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köse Özturan, M.; Kurnuç Seyhan, A. Determination of optimum insulation thickness of building walls according to four main directions by accounting for solar radiation: A case study of Erzincan, Türkiye. Energy Build. 2024, 304, 113871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linzi, F.; Jialong, W.; Yao, C.; Jian, F.; Pooya, S. Shear Performance of Large-Thickness Precast Shear Walls with Cast-in-Place Belts and Grouting Sleeves. ASCE-ASME J. Risk Uncertain. Eng. Syst. Part A Civ. Eng. 2023, 9, 04023005. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.