Abstract

Between 1940 and 1980, large scale social housing construction in Milan reshaped the city’s modern urban identity, yet how these postwar estates are perceived today remains insufficiently documented. This study analyzes user-generated Google Maps reviews to examine how these neighborhoods are evaluated in terms of sentiment and recurring narratives. We develop a replicable Natural Language Processing (NLP) workflow that combines automated translation, sentiment scoring, thematic keyword extraction, and unsupervised clustering to compare perception patterns across construction decades and architectural typologies, and we synthesize multi dimensional signals into a Perceived Space Quality Index (PSQI). Results show clear differentiation by typology and period: earlier courtyard-based estates are more frequently associated with positive evaluations, while later open block modernist developments exhibit more polarized discourse. Across clusters, positive evaluations most often co-occur with references to well-maintained shared spaces and active everyday life, while negative discourse concentrates on neglect and insecurity. Review narratives also increasingly foreground social experience and reputation over formal description. Overall, the workflow supports comparative reading of public narratives across estates and highlights which themes most shape favorable or unfavorable perception.

1. Introduction

The historical evolution of social housing in Europe mirrors broader shifts in welfare policy, spatial equity, and architectural thought [1]. Originating in the early twentieth century as a material arm of the welfare state, public housing was conceived not only to provide affordable dwellings but also to advance an urban ideal of collective well-being and modernization [2]. After World War II, this agenda intensified: European cities became key testing grounds for large-scale estates as welfare infrastructure and as modernist instruments of social reconstruction [3]. Initially framed as progressive solutions, promoting social equality, hygiene, and collective life, many estates later followed uneven trajectories shaped by economic restructuring, demographic change, and welfare retrenchment [4]. As a result, developments once associated with architectural innovation increasingly acquired stigmatized reputations, becoming publicly framed as spaces of isolation, decline, or socio-spatial marginality [5].

In postwar Italy, the rapid expansion of edilizia residenziale pubblica (ERP) from the 1940s to the 1980s reflected both the urgency of reconstruction and a belief that modern architecture could help produce a new social order [6]. Milan, Italy’s leading industrial metropolis, became a primary arena for this ambition, as demographic pressure and housing scarcity after the war drove sustained state-led housing delivery and large-estate development [7,8,9]. Within the broader European trajectory of postwar estate-building, Milan also stands out as a significant laboratory in which public programmes moved from INA-Casa neighbourhoods in the 1950s to later modernist districts such as QT8, Gallaratese, and Gratosoglio, translating planning ideology into built form at scale [10]. These ERP estates embodied confidence in rationalist design, functional efficiency, and collective facilities as organizers of everyday life, while their later trajectories became intertwined with patterns of socio-spatial division, governance challenges, and reputational decline [11,12]. Yet despite their enduring centrality in Milan’s urban fabric and social history, how these estates are perceived, evaluated, and remembered in contemporary public discourse remains insufficiently understood.

Existing research has provided rich accounts of postwar social housing estates from architectural history, design theory, and policy perspectives, increasingly treating their transformation as a major field of debate across multiple disciplines [13,14]. Within this body of work, studies have examined typological innovation and planning ideology in the production of postwar estates, together with the welfare-state logics and housing policy arrangements that underpinned their delivery [15]. They have also traced subsequent trajectories of decline and urban decline-driven socio-spatial division, as well as processes of regeneration, poverty and ethnic segregation, and broader policy challenges affecting large estates across Europe. Finally, this literature highlights institutional restructuring and paradigm shifts in social housing governance under welfare-state transformation. Research in urban sociology has further highlighted how stigma, reputational dynamics, and “social mix” policies influence contemporary outcomes and public understandings of postwar estates across Europe [16,17]. At the national and local levels, research has detailed how housing policy arrangements [18], welfare restructuring [19], and service provision shape the governance context in which estates are maintained, interpreted, and targeted for intervention [20,21]. However, the prevailing emphasis on expert accounts and official metrics leaves comparatively less room for a key dimension: how public perception is produced in everyday experience and public narration, where evaluative judgements emerge through encounters and affect, and are amplified through circulating, place-anchored stories that sediment into reputation over time [22].

Digital platforms provide a new opportunity to observe such narratives at scale [23]. Google Maps reviews provide short, situated accounts linked to specific locations within and around housing estates; because they are not residents-only and often describe facilities, services, and public spaces, they can be treated as place-anchored public narratives [24]. In urban and heritage studies, NLP has been widely used to extract sentiment and thematic structures from large volumes of reviews, particularly for parks (Table 1) [25,26], streets and tourism or heritage settings [27]. By contrast, comparable review-based, NLP-enabled evidence remains limited in social housing research. As a result, the public image of postwar housing estates, including the recurrent themes and symbolic frames through which they are narrated, is still more often inferred from expert and policy accounts than traced empirically from everyday digital discourse.

Table 1.

Comparative Overview of Social Media-Based Sentiment and Behavior Analysis in Urban Studies.

Urban “memory” is understood here not as private nostalgia but as a collective, socially mediated process through which places acquire durable public meanings [30,31,32]. It is closely tied to morphology, since urban form provides the spatial cues and recurring settings through which memories are anchored and contested over time [33]. Memory thus links built form to interpretation, while meaning refers to the relatively stable narrative frames and labels through which places are publicly understood within specific historical contexts [34]. From this perspective, Milan’s postwar ERP estates can be approached as both modernist morphologies and mnemonic landscapes.

Accordingly, this study draws on platform-based narratives to examine how everyday evaluations consolidate into shared framings, providing an empirical lens on the evolving memory and meaning of modernist social housing. Google Maps reviews are treated as place-anchored public narratives generated through encounters by both residents and non-residents, rather than as residents-only testimony. In this paper, ERP estates denote postwar public social housing communities in Milan as the primary unit of analysis; district refers to the community-scale level for comparative interpretation; and places within ERP estates are the review-anchored locations, including formal public facilities and informally named service-oriented or residential places.

Building on these definitions, the study addresses three questions: (1) how are ERP estates and their internal places evaluated in sentiment and emotional tone; (2) what recurring themes and symbolic framings structure these narratives; and (3) how do these patterned evaluations accumulate into a collective, evolving memory of Milan’s postwar social housing. Methodologically, we combine NLP-based sentiment and thematic analysis with interpretive reading to offer a citizen-centered perspective that complements expert-led architectural and policy assessments.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Context and Case Selection

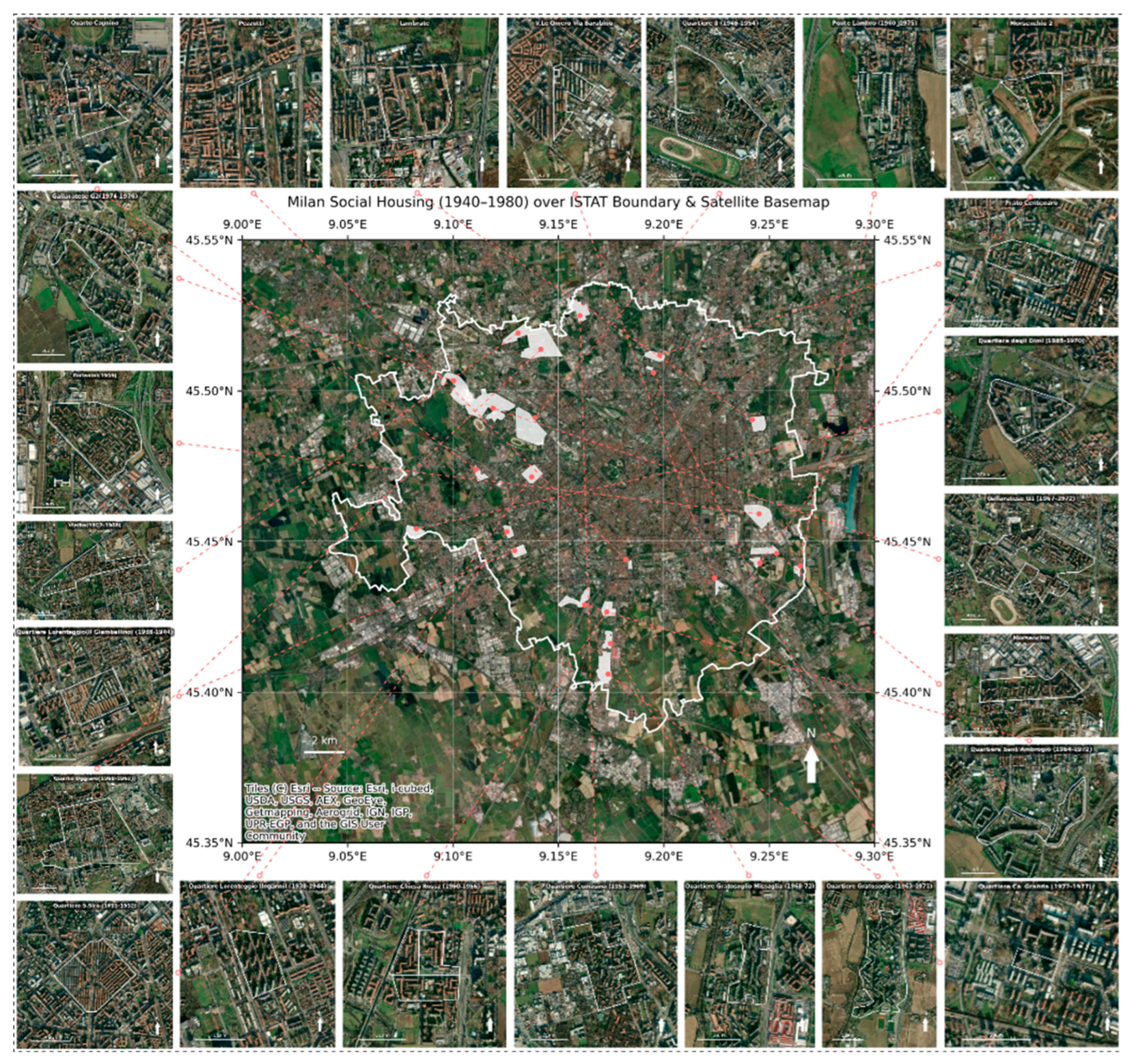

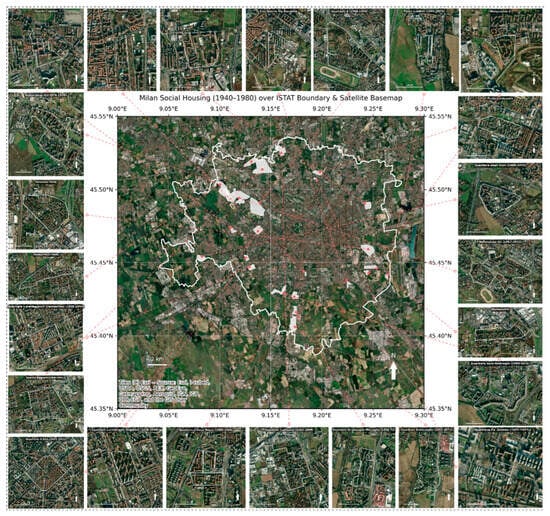

The study focuses on a curated selection of Milanese social housing projects built between 1940 and 1980, a period of intensive public housing development in Italy. Drawing from municipal planning archives, historical cartography, and scholarly documentation, 24 representative sites were identified. These include experimental urban districts such as QT8 (1946–1954), large-scale complexes like Gallaratese (1967–1972), peripheral estates such as Gratosoglio (1962–1968), and earlier ensembles like San Siro (1931–1952), among others (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution of the 24 selected ERP estates built between 1940 and 1980 in the Municipality of Milan. Municipal boundary layers are derived from the 2025 non-generalized administrative boundary dataset released by ISTAT (Istituto Nazionale di Statistica).

Each selected building was geolocated using KML-formatted spatial data, with key metadata recorded: year of completion, architectural authorship, formal typology, and current usage condition. The resulting dataset represents a cross-section of Milan’s social housing legacy in terms of spatial scale, urban positioning, and historical significance.

2.2. Data Collection

User-generated reviews were collected from Google Maps, which provides georeferenced comments with standardised spatial and temporal metadata. A list of social housing buildings, including official names, coordinates, and administrative identifiers, was first compiled into a GIS-ready point dataset. These coordinates were then used as query inputs to the Google Places API to retrieve all associated user reviews. In total, 1425 reviews were collected across 24 ERP estates. For each review, the API returned the text content, rating score, Unix timestamp, relative time label, reviewer name, and optional profile metadata. All records were compiled into a unified table and spatially linked to their corresponding building points, forming an integrated GIS dataset for subsequent text preprocessing.

Importantly, since Google reviews may include non-resident visitors and may sometimes describe experiences with local facilities/services, we interpret these measures as place-based perceived districts experience signals, rather than strictly residents only assessments.

2.3. Text Mining Framework

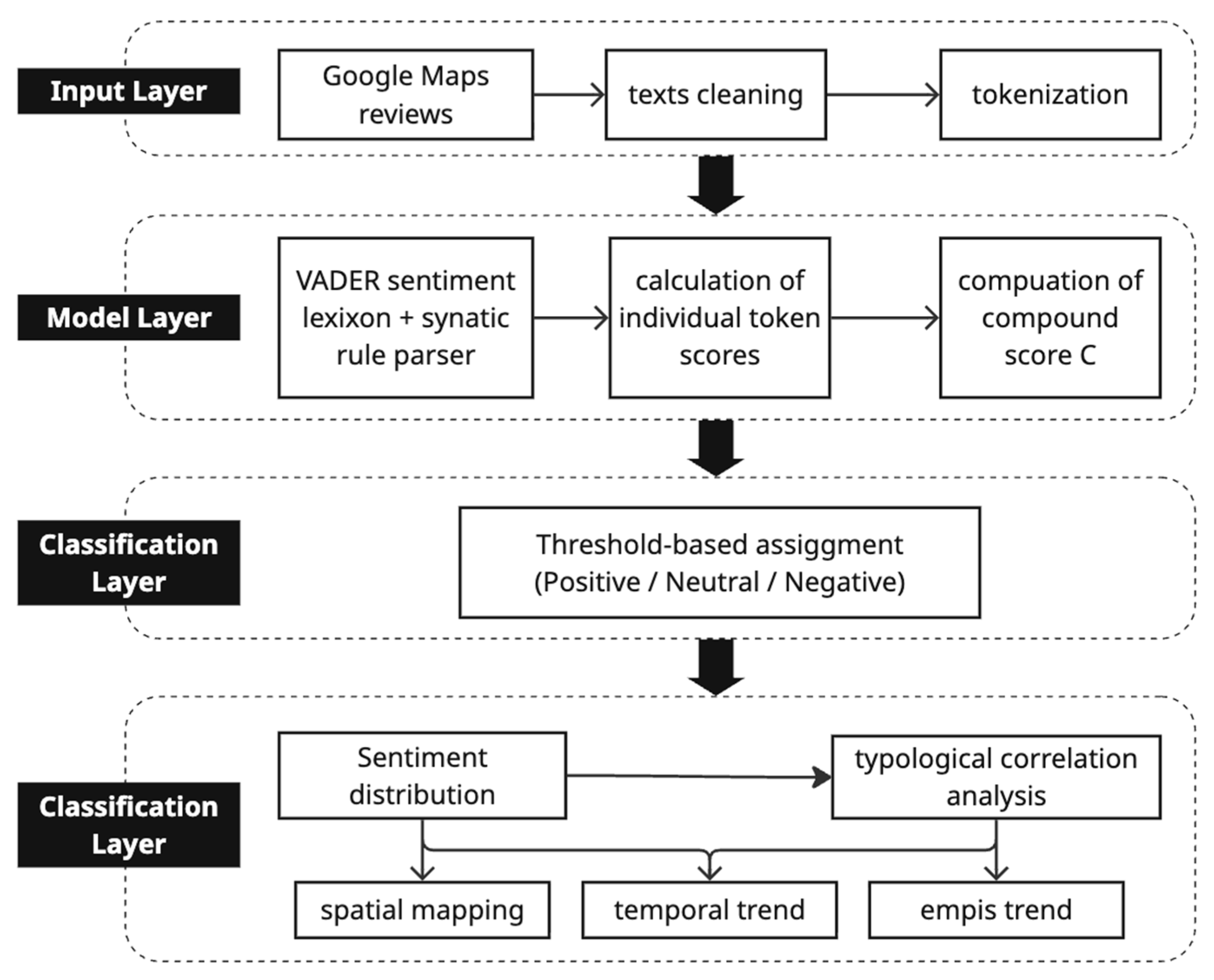

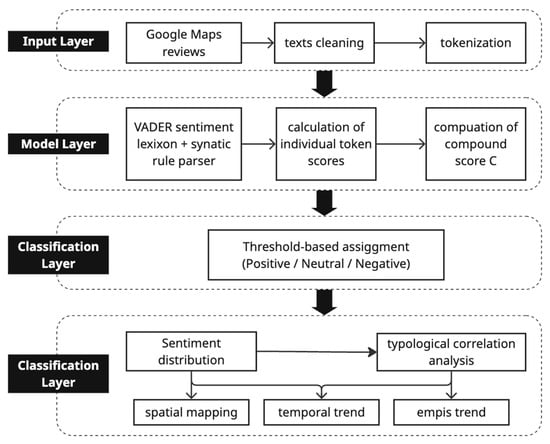

2.3.1. Sentiment Extraction

To assess emotional perceptions, this study used the VADER model [35], which combines a validated sentiment lexicon with syntactic and contextual rules. We selected this lexicon and rule-based approach because dictionary methods provide an interpretable and reproducible baseline that avoids dependence on task-specific labeled training data and modelling choices, which is valuable for cross community and multi year comparison [36]. Compared with supervised transformer-based classifiers that often require large labeled corpora and domain adaptation, VADER supports transparent, scalable analysis when applied consistently across ERP estates and time periods.

For each review, VADER produces four outputs (positive, negative, neutral, and a compound score (). The compound score is a normalized weighted summary of overall valence, computed from token level sentiment contributions and bounded to the range (−1, +1) by a hyperbolic tangent transformation [35] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sample User Reviews and Sentiment Classification in Milanese Social Housing Districts.

We use as the Sentiment Score in subsequent analyses. Reviews were classified into three sentiment categories using standard thresholds: ( ≥ 0.05), negative ( ≤ −0.05), and neutral otherwise [37].

Analyses were conducted in Python 3.11 with vaderSentiment (v3.3.2). Italian reviews were translated into English using MarianMT (Helsinki NLP) to ensure lexicon compatibility (In Figure 2). A validation against manual annotations showed good overall agreement (accuracy = 0.855; Macro F1 = 0.567; see Table A1). Errors were concentrated in linguistically complex cases (e.g., negation and irony), consistent with known limitations of translation plus lexicon-based sentiment analysis [38,39]. As sentiment is aggregated at the ERP estate level, these limitations are unlikely to affect overall perception patterns, but they do constrain review-level interpretation. Sentiment is therefore treated as an approximate affective indicator aggregated at the estate level for relative comparison and clustering, rather than a precise label for individual reviews.

Figure 2.

Workflow of sentiment extraction and classification for Google Maps reviews in Milanese social housing districts.

2.3.2. Thematic Dimensions of Public Commentary

Transforming unstructured social media commentary into analytically meaningful insights requires the establishment of a clear thematic interpretation framework, capable of capturing the diverse ways in which built environments are perceived, evaluated, and discussed. In this study, we developed a keyword-based thematic mining framework to organize user-generated reviews into conceptually coherent dimensions, enabling a structured interpretation of public discourse surrounding ERP estates.

Building upon prior research on behavioral mapping [40], environmental perception [41,42], and health-oriented urban analysis [43,44], and inspired by social media-based behavioral sentiment mining [25], we identify six thematic dimensions that recurrently emerge in public commentary on social housing environments. These dimensions reflect both the physical attributes of the built environment, but also its social functions, symbolic meanings, and emotional resonances, thereby offering a multidimensional lens for interpreting lived experience. (Table 3). The six dimensions capture a broad spectrum of evaluative perspectives through which housing estates are publicly discussed—ranging from material and spatial qualities, to collective memory, social life, and affective attachment.

Table 3.

Thematic Dimensions of Review Classification.

Together, these six thematic dimensions form the interpretive basis of our text mining strategy, enabling housing narratives to be examined beyond simple sentiment polarity. Because not all dimensions can be robustly quantified from short and heterogeneous reviews, we operationalize four observable behavioral and emotional indicators for community level aggregation and clustering: Physical Activity, Child Activity, Social Interaction, and Positive Emotion, while retaining the six-dimensional framework for thematic interpretation.

2.3.3. Keyword Expansion Process

We first built a seed dictionary (12–15 keywords per dimension) through manual coding of 1425 reviews, covering both explicit descriptors (e.g., “dirty”, “unsafe”) and context dependent expressions (e.g., “felt at home”, “abandoned”). We then expanded the dictionary using FastText bilingual embeddings [59,60] and cross lingual lexical probing methods [61], followed by manual context checks to remove ambiguous terms [62,63]. The final bilingual keyword pool contained over 300 terms.

2.3.4. Quantifying Public Space Perception: Toward a Composite Quality Index

Integrating sentiment polarity and thematic content, each review was transformed into a structured feature vector consisting of: (1) a normalised sentiment score (−1 to +1), (2) a categorical sentiment label (positive, neutral, negative), and (3) a six-dimensional binary vector indicating the presence of thematic attributes. At the building and ERP-estate scales, these features were aggregated to compute the share of positive sentiment, the intensity of functionally relevant themes, and the diversity of emotional and behavioural expressions.

Together, these components form the Perceived Space Quality Index (PSQI), defined as:

where denotes community level sentiment intensity, computed as the mean Sentiment Score across all reviews within each ERP estate [64]. captures beneficial thematic content, measured as the proportion of reviews containing at least one predefined positive theme keyword (e.g., usability, maintenance, comfort, safety, or affective expression) [65]. Represents narrative diversity and is quantified using Shannon entropy based on the distribution of sentiment labels within each community [66]; higher values indicate more diverse and balanced expressions. Following prior PSQI implementations [67,68], the three components are equally weighted (α = β = γ = 1/3).

This choice reflects the assumption that affective intensity, thematic meaning, and experiential diversity constitute complementary and equally important dimensions of perceived public space quality. Equal weighting avoids introducing a priori preferences among dimensions and provides a transparent baseline for composite indicator construction. By combining perception-based sentiment signals with interpretable thematic indicators extracted from user-generated comments, PSQI provides a concise measure of perceived public space quality across ERP estates.

3. Results

This section presents the empirical outputs of the NLP workflow. We summarize baseline descriptive statistics, present perception clusters based on four behavioral and emotional indicators, and examine temporal robustness and sensitivity to review composition.

3.1. Sentiment and Engagement

3.1.1. Descriptive Statistics

Reviews from 24 ERP estates constructed between the 1940s and the 1980s were analyzed to assess public perception in relation to spatial scale, review density, and sentiment polarity. As summarized in Table 4, the selected districts cover an average area of 330,251 sqm, with substantial between-district variation (Std. Error = 63,556 sqm). Each estate received an average of 50.38 reviews, with a mean review density of 5.24 per 10,000 sqm, indicating uneven levels of online engagement. The average sentiment score is moderately positive (0.43), while the observed range (−0.06 to 0.71) indicates marked heterogeneity in emotional tone.

Table 4.

Descriptive Statistics of Social Housing Districts.

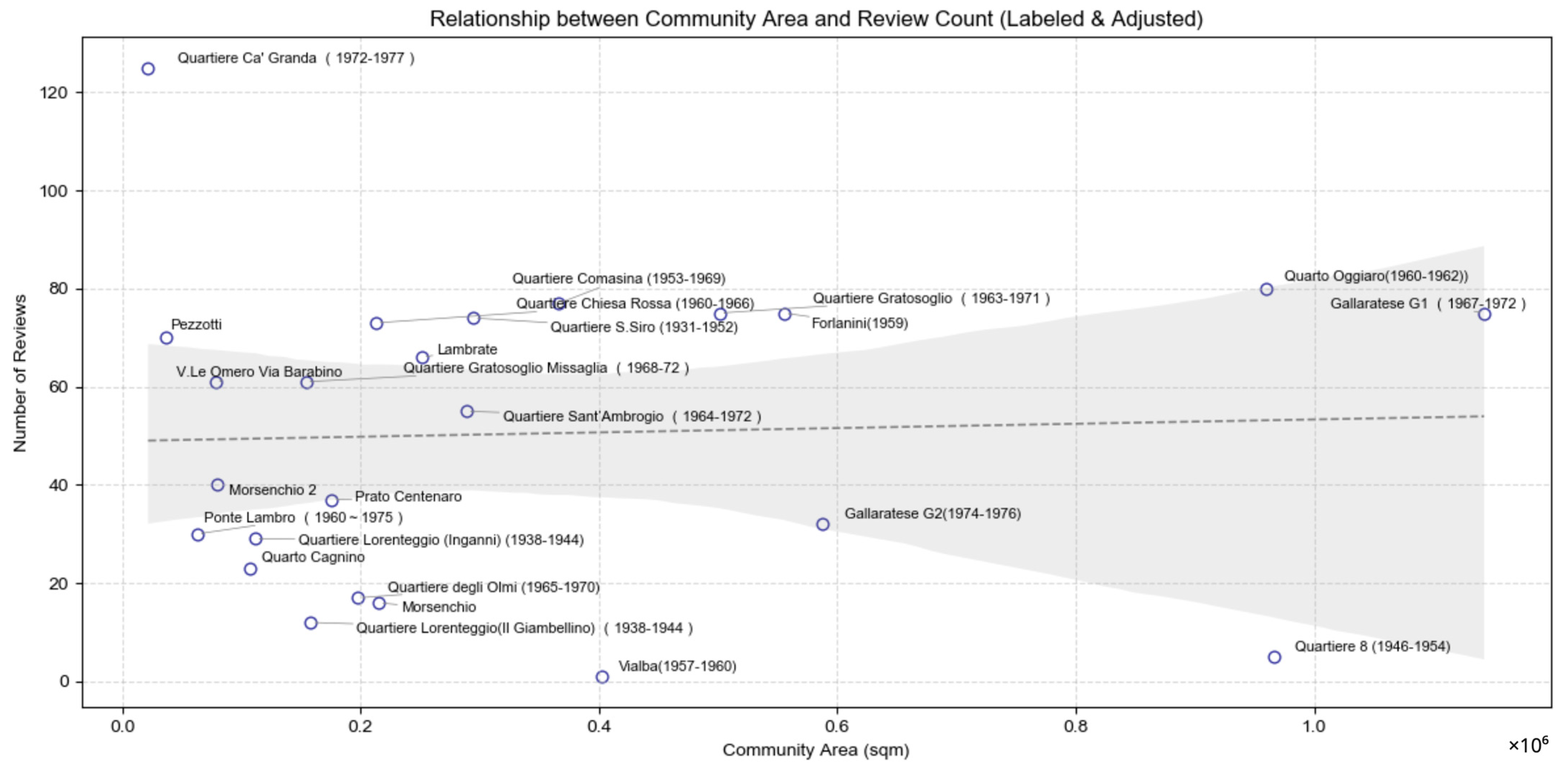

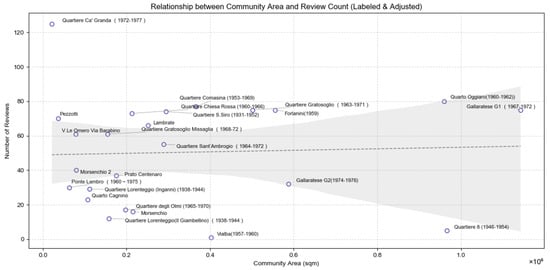

To examine whether spatial scale affects online engagement, a regression analysis was conducted between community area and the number of user reviews. As shown in Figure 3, the fitted trend line indicates a weak negative association. Several mid-sized estates (e.g., Quartiere Lorenteggio and Ca’ Granda) exhibit relatively high review volumes, whereas some larger estates (e.g., Quartiere 8 and Gallaratese G1) receive fewer comments.

Figure 3.

Scatterplot of community size versus review volume. Outliers highlight estates where engagement markedly diverges from size-based expectations.

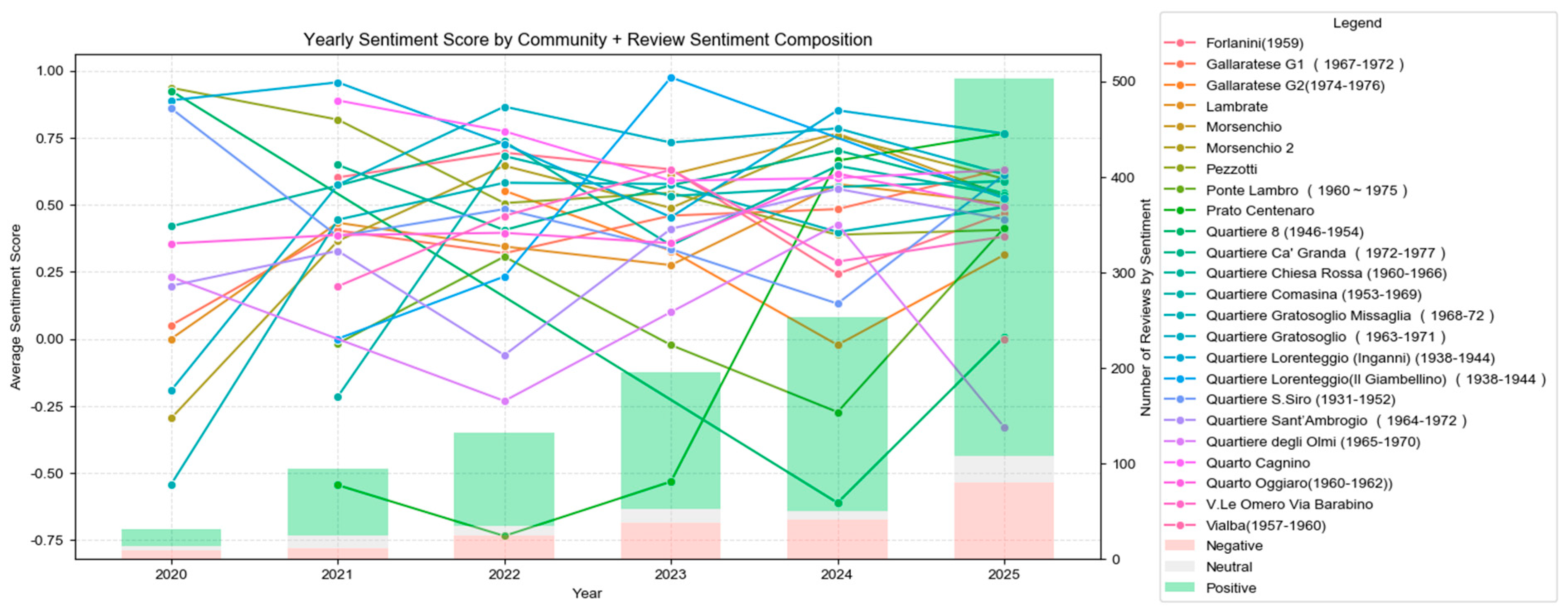

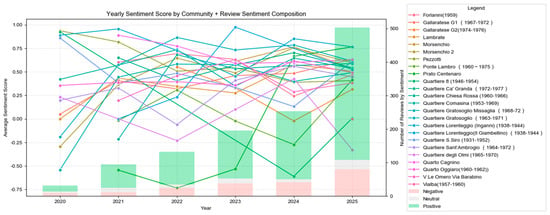

3.1.2. Yearly Sentiment Trajectories

To examine temporal changes in public sentiment, the annual average VADER sentiment scores [35] were calculated for each community from 2020 to 2025 (Figure 4). The trajectories reveal clear differences between communities: estates such as Gallaratese G1 and Ca’ Granda maintain consistently positive sentiment, whereas others, including Gratosoglio and S. Siro, show noticeable fluctuations or a gradual decline.

Figure 4.

Yearly Sentiment Score by Estates with Review Sentiment Composition. Note. Solid lines show the yearly mean VADER compound sentiment score for each ERP estate (left y-axis; −1 to +1). Green bars indicate the number of reviews per year (right y-axis). Years with low review counts may show greater fluctuation; the figure is intended to illustrate overall temporal tendencies.

Figure 4 also visualizes review volume and sentiment composition by year. After 2023, both the number of reviews and the share of positive reviews increase across multiple estates, pointing to rising online engagement and more active public narration of these neighborhoods. Across the 24 communities, three temporal patterns emerge: (1) consistently positive, (2) emotionally volatile, and (3) low engagement with near neutral sentiment. Temporal patterns may be associated with changes in urban policy, improvements in maintenance, demographic change, or emerging neighborhood issues.

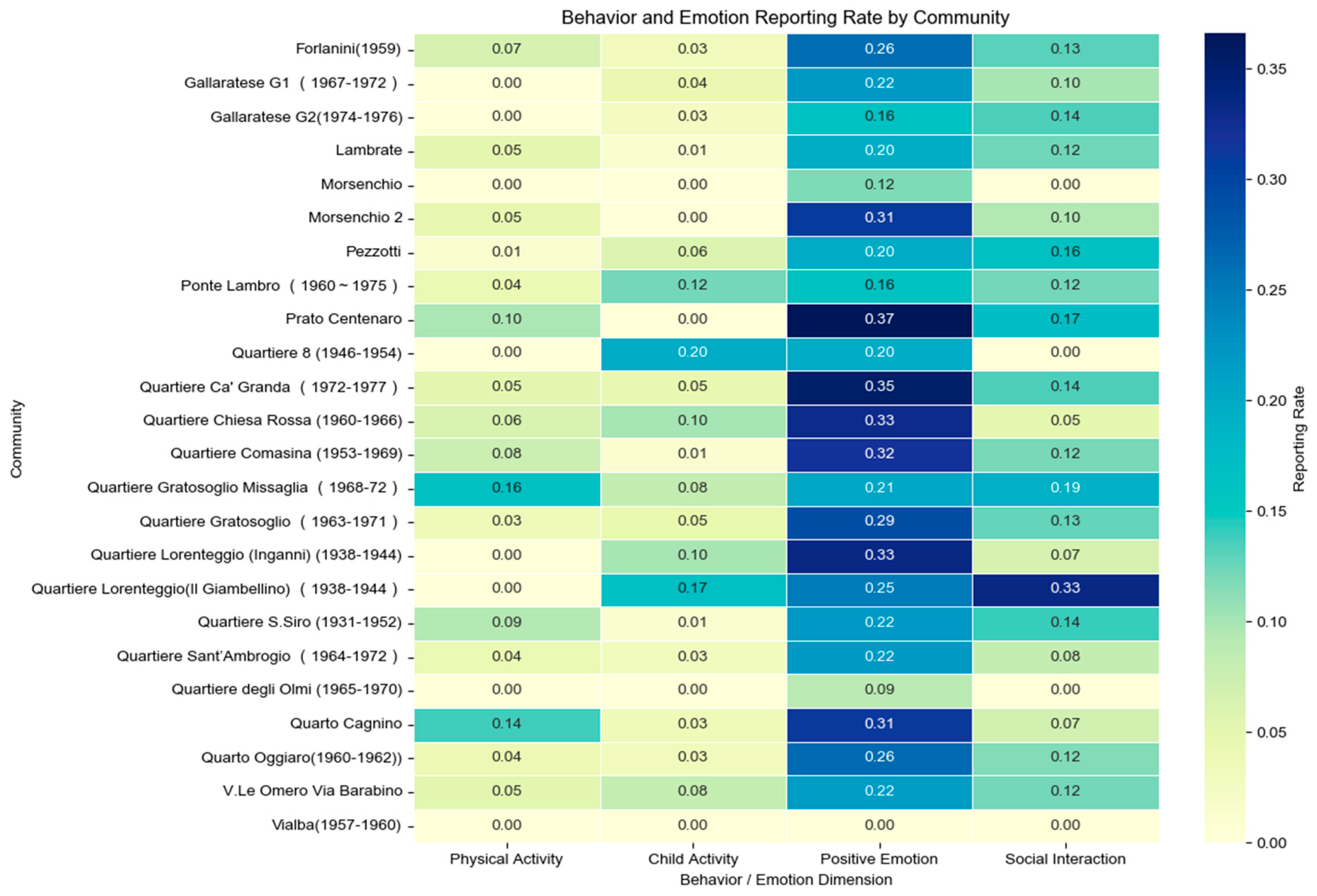

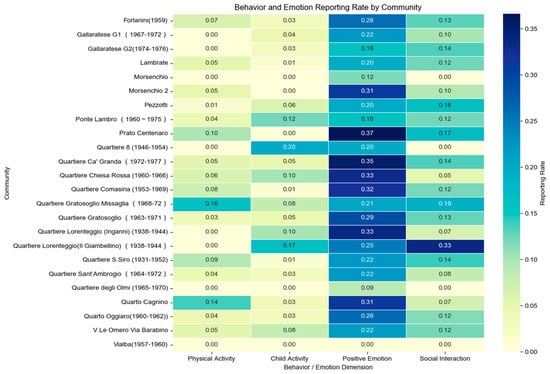

3.2. Thematic Pattern of Reviews

Beyond sentiment polarity, we applied keyword-based thematic tagging to the review corpus to derive four normalized reporting dimensions for each ERP estate—Positive Emotion, Social Interaction, Child Activity, and Physical Activity (see Table A2 and Table A3 for the tagging scheme). Figure 5 reports the resulting reporting rates. Overall, Positive Emotion is the most prevalent dimension (mean = 0.23), followed by Social Interaction (mean = 0.11), while Child Activity (mean = 0.05) and Physical Activity (mean = 0.04) are comparatively less frequent. This distribution suggests that reviews are oriented more toward affective evaluation and social perception than toward detailed accounts of routine on-site activities. (See Table A2 and Table A3).

Figure 5.

Behavior and Emotion Reporting Rate by Community.

Despite the modest averages for activity-related content, several estates display distinctive peaks that form recognizable thematic “signatures”. For instance, Comasina and Ca’ Granda show particularly high Positive Emotion (above 0.32), indicating recurring expressions of appreciation and attachment; Lorenteggio (Giambellino) and S. Siro peak in Social Interaction (above 0.30), implying that these neighborhoods are repeatedly narrated through encounter and sociability; and Gratosoglio Missaglia and Quarto Cagnino exhibit elevated Physical Activity (above 0.14), reflecting stronger references to walking and outdoor routines. Together, these patterns indicate that ERP estates are not only evaluated as housing districts but are repeatedly framed through a limited set of recurring narrative lenses emotion, sociability, family life, and everyday activity thereby stabilizing what each estate “stands for” in public discourse. These thematic structures provide the basis for subsequent cluster analysis, in which communities are grouped according to their dominant emotional and behavioral reporting patterns.

3.3. Collective Memory Formation

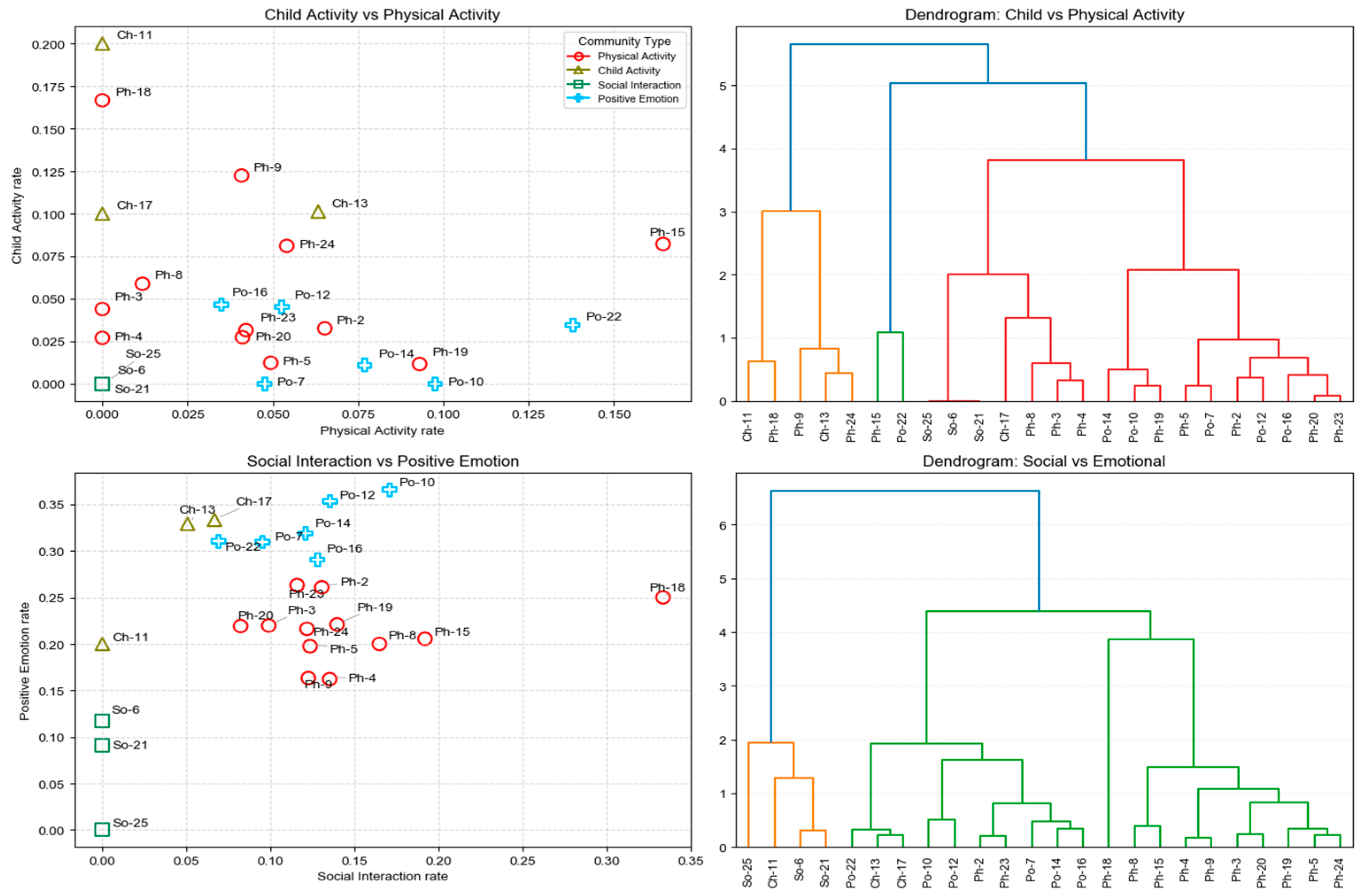

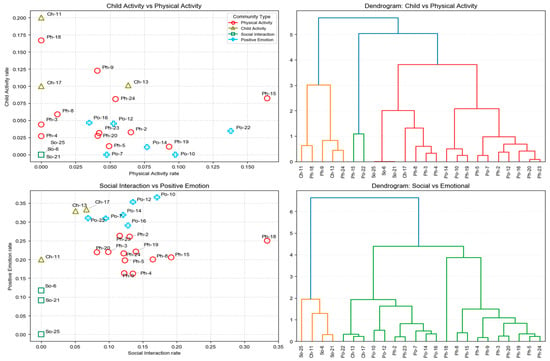

3.3.1. Cluster Typology and Relational Patterns

To translate thematic regularities into interpretable estate-level types, Table 5 summarizes the resulting typology, distinguishing four recurring “memory–behavior” configurations: Health-oriented (Group 1), Child/Family-oriented (Group 2), Social-oriented (Group 3), and Low-activity (Group 4). For consistency across figures and analyses, each estate is also assigned a compact symbolic code—Ph, Ch, So, and Po—and a short identifier (e.g., Ph-15, Po-10, Ch-13). The mapping between community names, short codes, and cluster labels is reported in Table A4.

Table 5.

Community Classification Summary table.

The clustering patterns in Figure 6 further show both convergence and divergence in these framings (Table A4). Some estates (e.g., Ph-15, Po-10, Ch-13) exhibit coherent profiles across dimensions, whereas others (e.g., So-25, Ch-11) emerge as outliers. Importantly, estates with comparable activity levels can differ substantially in emotional tone, suggesting multiple narrative pathways through which public impressions and shared memory of postwar ERP estates are formed.

Figure 6.

Behavioral Correlations among Milanese Social Housing Communities: Physical Activity, Child Activity, and Social Interaction. Note. The upper panel compares child activity rates to physical activity rates, while the lower panel compares social interaction rates to physical activity rates, across selected Milanese social housing communities (1940–1980). Data points are color-coded by dominant behavioral dimension as classified in cluster analysis.

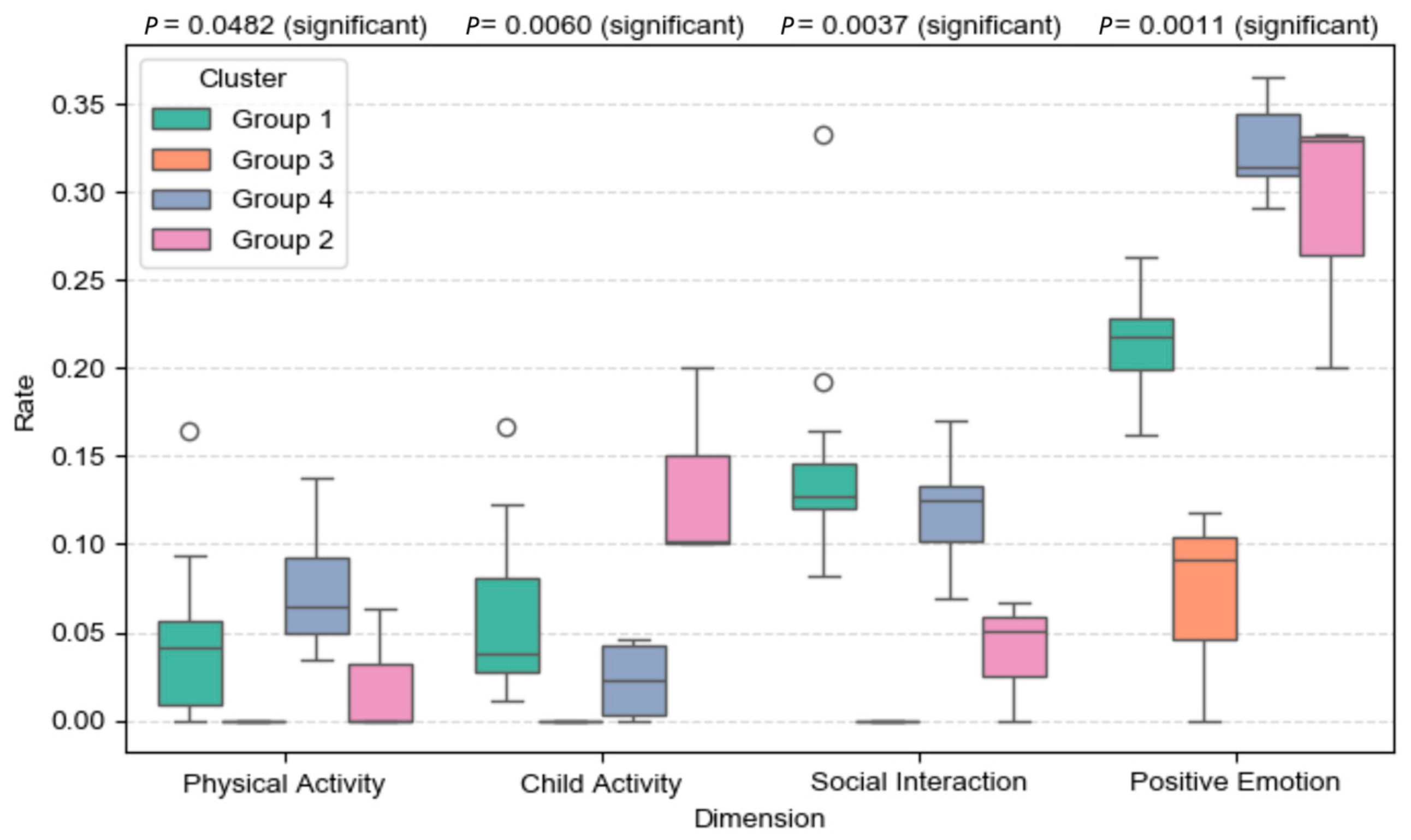

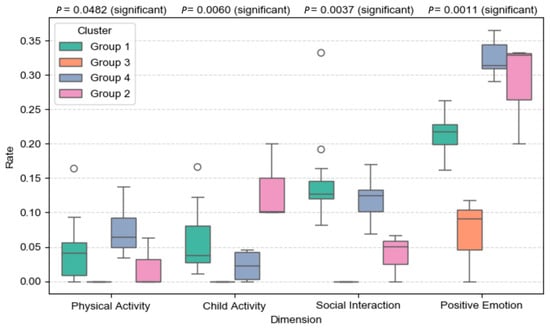

3.3.2. Group Contrasts

To assess whether the identified cluster types differ systematically in their narrative emphasis, further validate between group differences, we conducted a comparative analysis of the four reporting dimensions across the four memory–behavior groups. Figure 7 compares the median reporting rates of all four behavioral dimensions across the four cluster types. ANOVA tests indicate that Child Activity (p = 0.006), Social Interaction (p = 0.0037), and Positive Emotion (p = 0.0011) all differ significantly among clusters, confirming the meaningfulness of the typological distinctions. By contrast, Physical Activity (p = 0.0482) shows only weak variation, suggesting that basic mobility or walking functions are more evenly distributed across the social housing ERP estates.

Figure 7.

Statistical Comparison of Behavior Dimensions across Estate Clusters. Note. Boxplots compare reporting rates of behavioural and emotional dimensions across the four perception groups, as defined in Table A1.

3.4. Validity Checks

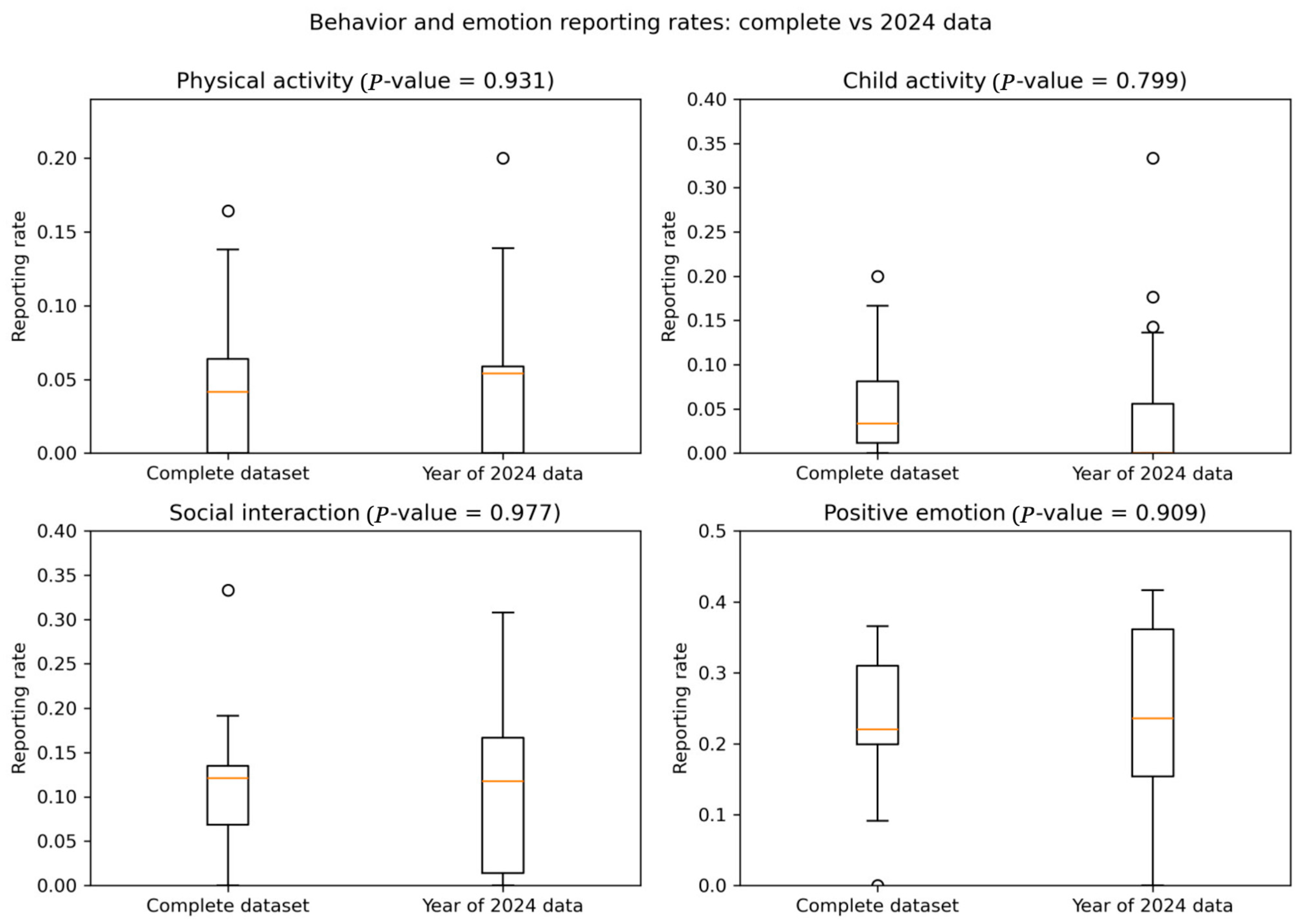

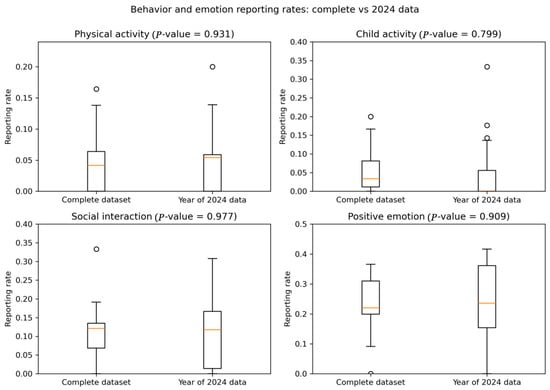

3.4.1. Temporal Stability

Robustness tests comparing the complete dataset with reviews from 2024 (Figure 8) indicate that reporting rates across all four dimensions remain consistent over time. The similarity in distribution and the absence of statistically significant differences (all p-values > 0.79) show that the behavioural and emotional patterns identified earlier are not driven by specific-year variations.

Figure 8.

Temporal robustness test showing the consistency of behavioral and emotional reporting rates between the full multi-year dataset and the 2024 subset.

This temporal stability suggests that the review-based indicators primarily reflect longer term characteristics of ERP estates, such as routine use, interaction patterns, and affective tone, rather than short-lived events or annual fluctuations in review activity. It also indicates that single year data offer a reasonable approximation of multi-year patterns, supporting the reliability of user-generated reviews for characterising everyday perceptions of these estates. Overall, the robustness results confirm that the observed memory–behavior configurations are relatively stable and not sensitive to the choice of temporal window.

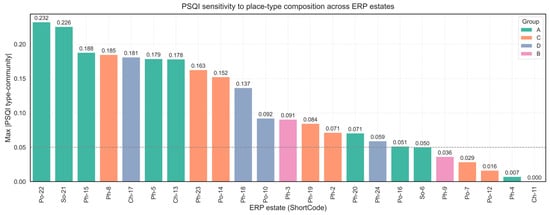

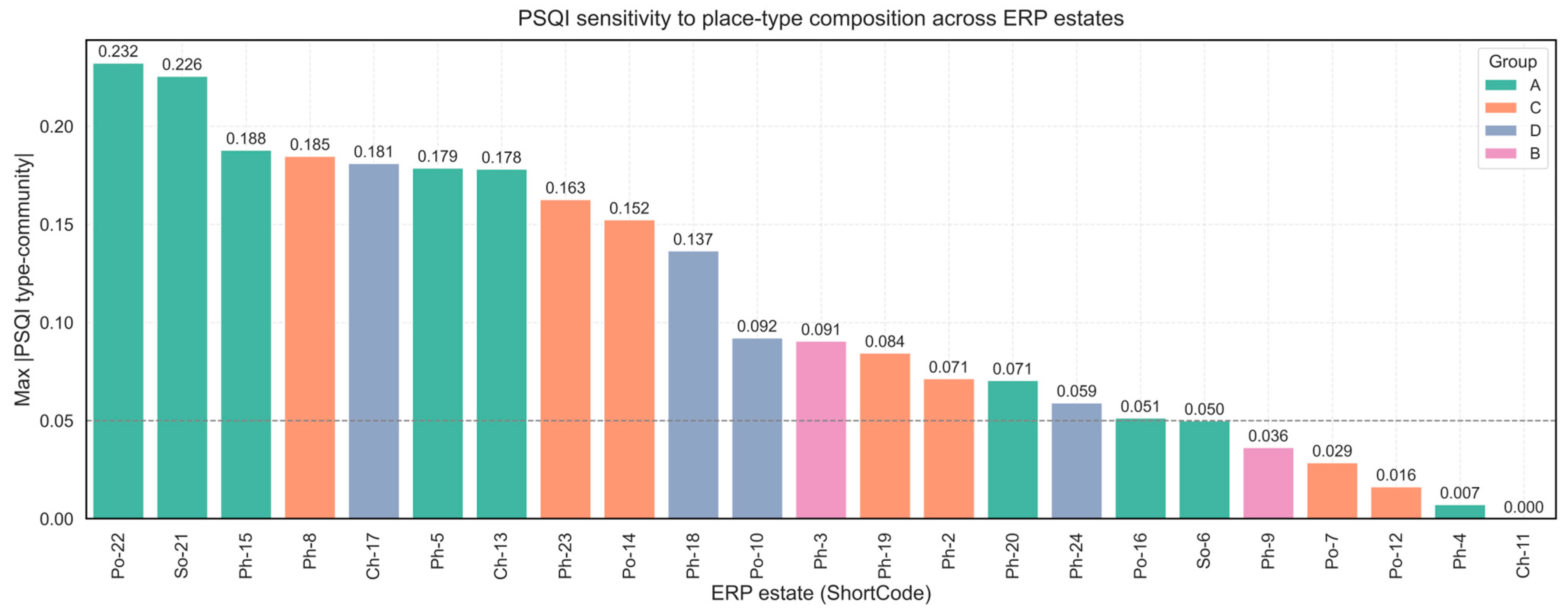

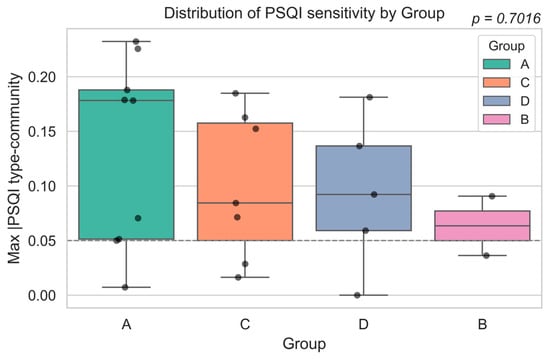

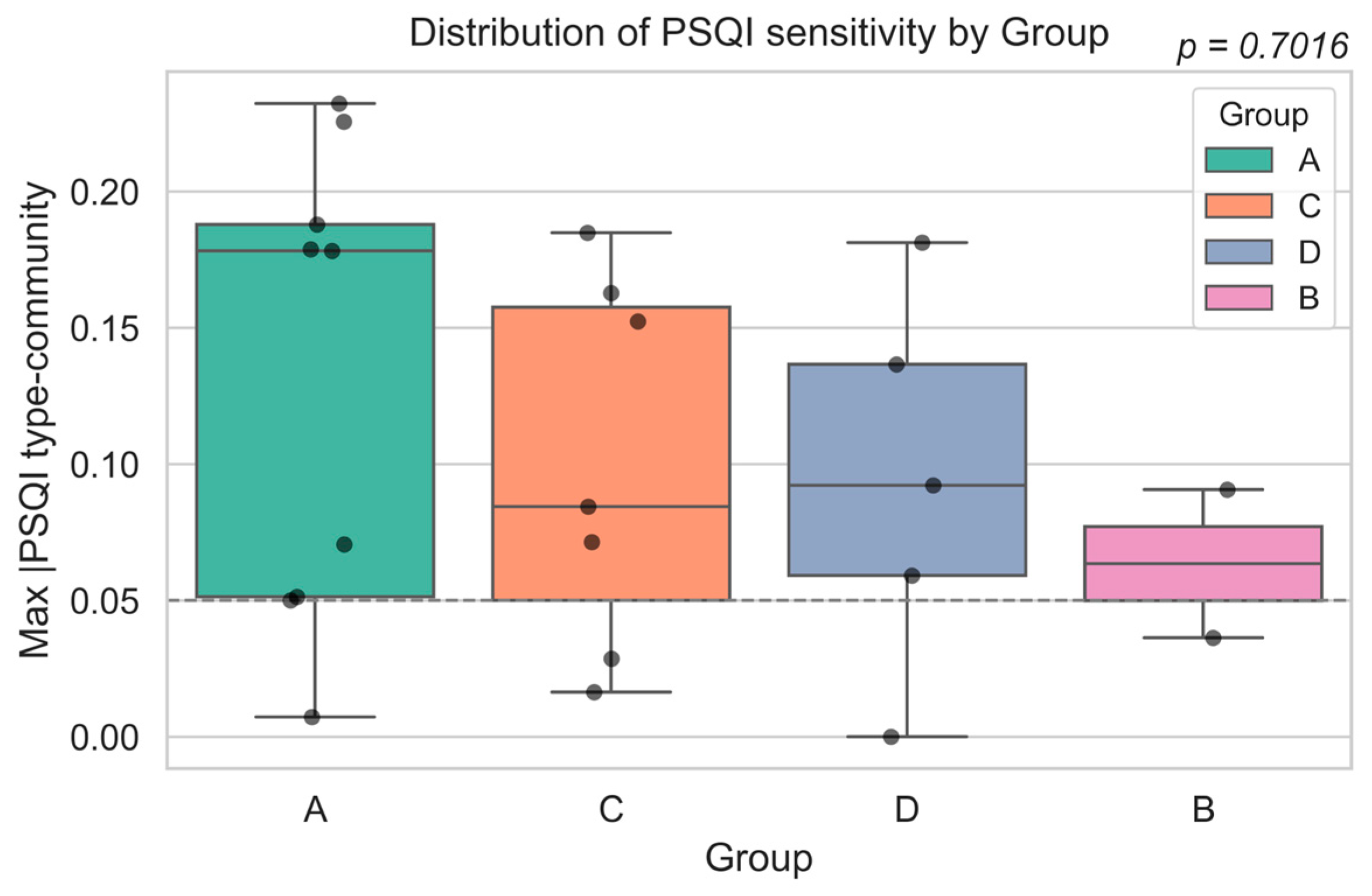

3.4.2. Target Heterogeneity

Because Google Maps reviews reference heterogeneous place targets within ERP estates, we examined whether review target composition biases perceptual outcomes. As shown in (Table A5), explicitly public facilities account for only about 12–13% of reviews, with most comments referring to unspecified or service-oriented micro-places. Comparisons between place-type-specific PSQI values and community-level PSQI scores show generally small within-estate deviations (Figure A1). Moreover, PSQI sensitivity does not differ significantly across memory–behavior groups (Kruskal–Wallis H = 1.417, p = 0.702; Figure A2). These results suggest that PSQI is robust to review target heterogeneity and captures neighborhood-scale perception rather than place-type-specific bias.

4. Discussion

Public perceptions of Milan’s postwar ERP estates reveal a persistent gap between everyday activity and emotional evaluation. Across many communities, strong affective tones coexist with limited reported use, while in others routine activity unfolds without corresponding symbolic attachment. This divergence raises a broader question: how do collective memory and lived experience interact in shaping the perceived quality of social housing environments beyond their physical form.

4.1. Commentary as Memory: What the Public Remembers

The cluster analysis indicates that Milan’s ERP estates are embedded in distinct and heterogeneous structures of public memory that cannot be reduced to physical form or spatial typology alone. Rather than reflecting morphology or scale, these memory regimes emerge from the long term interplay of everyday routines, family networks, demographic trajectories, and symbolic narratives that accumulate over time. As a result, collective memory within ERP housing is neither uniform nor spatially deterministic, but socially constructed and unevenly distributed across estates.

Patterns of engagement in user commentary further suggest that public perception is shaped less by physical size than by broader socio-spatial conditions, such as historical identity, functional mix, and urban integration. Consistent with prior studies of online review data, evaluative intensity aligns more closely with symbolic meaning and lived experience than with absolute spatial extent, indicating that review activity reflects perceived relevance rather than spatial magnitude.

Across the ERP system, distinct memory–behavior configurations become apparent. Some estates sustain routine use with limited emotional or symbolic attachment, functioning primarily as spaces of passage and accessibility. Others are strongly anchored in family and household-based memory, where intergenerational routines dominate public narratives. In historically prominent estates, symbolic reputation persists despite limited contemporary engagement, suggesting an increasingly archival form of social memory sustained through discourse rather than practice. Finally, certain communities display a nostalgic yet low activity profile, in which positive emotional tone endures even as everyday engagement declines.

These differentiated memory–behavior configurations challenge the long-standing planning assumption that ERP estates constitute a homogeneous housing category. Even estates with comparable typologies or adjacent locations may diverge substantially in their positions within the collective memory landscape, illustrating that public meaning is shaped less by physical layout than by socially constructed narratives and lived experience. The significance of ERP environments thus resides not only in architectural form, but in the ways residents and users remember, interpret, and reframe everyday life over time.

4.2. Statistical Validation of Memory Behavior Pattern

Using the four thematic dimensions, the cluster analysis identifies four perception-based ERP estate types that represent different alignments between everyday practice and collective memory (Table 5 and Table A4). Rather than simply separating communities by activity intensity, the typology distinguishes how emotional tone, social framing, and family-related routines combine into recognizable narrative regimes.

Between-group tests (Figure 7) confirm that these regimes are meaningfully differentiated. Emotional and social indicators show the clearest contrasts across clusters, while Child Activity specifically characterizes the family-oriented type, consistent with place-attachment research linking intergenerational routines to durable emotional associations [56,58]. By contrast, Physical Activity varies only weakly, suggesting that basic mobility is a shared baseline rather than a key discriminator of perceived place meaning. The results also highlight a recurrent mismatch between symbolic reputation and reported everyday engagement in some historically prominent estates, echoing broader discussions of stigma, demographic change, and governance pressures in public housing contexts [69,70]. Finally, the presence of high positive emotion alongside limited behavioral reporting in low-activity estates is consistent with selective or retrospective place memory, where attachment persists through nostalgia and remembered life-course experience [71,72].

The statistical validation strengthens the interpretation that ERP estate perception is shaped less by generic physical behavior than by affective resonance and social narratives, reinforcing the need for evaluation and renewal approaches that integrate emotional and relational dimensions alongside morphological conditions.

4.3. Interpreting Review Heterogeneity and Temporal Robustness

An important interpretative issue in this study concerns the heterogeneity of review targets within Milan’s ERP estates. Google Maps reviews refer not only to formally designated public spaces, but also to a wide range of informal micro-places and everyday service interfaces embedded in the residential fabric (see Table A5). This reflects how ERP environments are experienced as integrated everyday settings rather than as collections of discrete facilities.

Empirical tests suggest that this heterogeneity does not substantially bias perceptual evaluation at the community scale. Across most estates, differences between place-type-specific PSQI values and community-level scores remain limited, indicating that perceived public space quality is relatively stable despite variation in review targets. Although a small number of districts show higher sensitivity to specific place types, these cases remain context-specific and do not form a systematic pattern across memory–behavior groups. This finding supports the interpretation of PSQI as a neighborhood-scale perceptual indicator, grounded in distributed everyday experience rather than in evaluations of single facility categories.

Temporal robustness tests further support this interpretation. Comparisons between the full multi year dataset and a single year subset reveal highly consistent behavioral and emotional reporting patterns, indicating that the identified configurations reflect longer-term characteristics of ERP estates rather than short-lived events or episodic fluctuations in online activity.

Taken as a whole, the robustness and sensitivity analyses highlight both the limitations and the strengths of review-based data. While individual comments are heterogeneous in target and timing, their aggregation reveals enduring patterns of perception that are meaningful at the neighborhood scale. This reinforces the value of digital commentary as a complementary source for understanding how public space quality and collective memory are experienced in postwar social housing environments.

4.4. Implications for Community Renewal and Management

The differentiated perception patterns identified in this study suggest that ERP estate renewal should move beyond uniform, typology-based approaches. Communities with strong emotional resonance but limited activity may warrant light, conservation-oriented interventions that protect symbolic value, while behaviourally active yet emotionally neutral estates may require programmes that strengthen social interaction rather than physical redesign. Likewise, family-oriented clusters indicate the need for child-friendly infrastructure, whereas socially detached estates highlight deficits in community facilities or neighbourhood services. These targeted responses align intervention priorities with the lived experience reflected in public commentary.

At the planning level, the stability of perceptual signals across years demonstrates that user-generated reviews can function as a complementary diagnostic tool, useful for detecting slow-moving changes in attachment, satisfaction, or perceived social vitality. While such data must be interpreted cautiously due to sampling bias, its integration with field surveys and demographic information can help planning agencies identify emerging problems earlier and allocate resources more precisely. Rather than replacing conventional methods, online commentary expands the evidence base for understanding how ERP environments are experienced and valued by residents.

5. Conclusions

This study develops a computational framework to analyse publicly expressed perception and memory of Milan’s postwar Edilizia Residenziale Pubblica (ERP) estates using geo-referenced Google Maps reviews. By extracting behavioural and emotional indicators from user-generated text, the analysis identified four distinct perception patterns, demonstrating that ERP estates are experienced and remembered in heterogeneous ways that extend beyond their physical form. Methodologically, the study shows that unstructured online commentary can be converted into interpretable indicators through thematic tagging, sentiment analysis, and clustering. Temporal robustness tests further indicate that these perceptual patterns are consistent across years.

Milan’s ERP estates are perceived, narrated, and remembered in public discourse through patterns that make “sentiment” interpretable against identifiable architectural and urban characteristics rather than as a standalone emotional score. Emotional tone and social framing differentiate estates more clearly than routine physical activity, and the empirical results point to three linked conclusions.

Perception differs by construction period and morphological logic. Earlier estates, more often linked to courtyard-based or spatially legible neighborhood structures, show more consistently positive evaluations. Later open-block modernist developments show more polarized narratives, with positive remarks co-occurring with recurrent references to neglect, insecurity, and social detachment. The contrast points to the role of spatial legibility, enclosure, and the perceived manageability of shared spaces in shaping affective judgement.

Estate scale does not provide a sufficient explanation for evaluation or engagement. Review volume shows only a weak relationship with community area. Sentiment does not follow a simple small-versus-large gradient. Several mid-sized estates attract disproportionately high attention and clearer reputational framing, while some larger estates receive fewer comments or display volatile trajectories. Public judgement appears more sensitive to everyday conditions that are repeatedly encountered and narrated, especially visible maintenance, safety cues, and the quality of service-oriented micro-places embedded in the residential fabric.

Collective memory forms through recurring narrative signatures that exceed routine activity accounts. The cluster typology indicates that Positive Emotion and Social Interaction separate estates more strongly than Physical Activity. Attachment, sociability, and reputation dominate public narration more than reported use intensity alone. Repeated evaluations sediment into recognizable memory patterns: functional but weakly attached places; family-anchored memories; reputation-driven identities with limited everyday practice; nostalgic positivity alongside low reported activity. Sentiment reads as a socially mediated interpretation of spatial form, management conditions, and reputational trajectories.

Several limitations should be noted. First, Google Maps reviews are self-selected and not resident only, which may introduce participation bias [73]; therefore, the results reflect publicly expressed perception and are interpreted at the ERP estate scale rather than as individual attitudes [74]. Second, sentiment analysis relies on automated Italian–English translation, which can dilute affective nuance and add uncertainty for a subset of reviews [75,76]. Future work should validate these findings using Italian-language sentiment models and a targeted human annotated sample [77,78]. Despite these constraints, the approach demonstrates the value of perception-based evidence for understanding and guiding ERP estate renewal and management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S.; Methodology, Y.N.; Formal analysis, Y.S.; Investigation, Y.N.; Resources, Y.N.; Data curation, Y.S.; Writing—original draft, X.Z.; Writing—review & editing, X.Z.; Visualization, Y.N.; Supervision, Y.N.; Project administration, Y.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC), grant number 52578037.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Validation of sentiment classification (manual annotation vs. VADER on translated reviews, N = 408).

Table A1.

Validation of sentiment classification (manual annotation vs. VADER on translated reviews, N = 408).

| Class | Support (n) | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | 327 | 0.94 | 0.911 | 0.925 |

| Neutral | 6 | 0.038 | 0.167 | 0.062 |

| Negative | 75 | 0.769 | 0.667 | 0.714 |

| Overall accuracy | 408 | 0.855 | ||

| Macro average | 0.583 | 0.582 | 0.567 | |

| Weighted average | 0.895 | 0.855 | 0.874 |

Note: Manual labels use three classes (positive/neutral/negative). Class imbalance is expected in Google Maps reviews, where neutral statements are relatively rare.

Table A2.

Community behavior emotion reporting table.

Table A2.

Community behavior emotion reporting table.

| Community | Physical Activity | Child Activity | Positive Emotion | Social Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.11 |

| Forlanini (1959) | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.26 | 0.13 |

| Gallaratese G1 (1967–1972) | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.10 |

| Gallaratese G2(1974–1976) | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.14 |

| Lambrate | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.12 |

| Morsenchio | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.00 |

| Morsenchio 2 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.31 | 0.10 |

| Pezzotti | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.16 |

| Ponte Lambro (1960~1975) | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.12 |

| Prato Centenaro | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.37 | 0.17 |

| Quartiere 8 (1946–1954) | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.00 |

| Quartiere Ca’ Granda (1972–1977) | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.35 | 0.14 |

| Quartiere Chiesa Rossa (1960–1966) | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.33 | 0.05 |

| Quartiere Comasina (1953–1969) | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.32 | 0.12 |

| Quartiere Gratosoglio Missaglia (1968–1972) | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.21 | 0.19 |

| Quartiere Gratosoglio (1963–1971) | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 0.13 |

| Quartiere Lorenteggio (Inganni) (1938–1944) | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.33 | 0.07 |

| Quartiere Lorenteggio(Il Giambellino) (1938–1944) | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.33 |

| Quartiere S.Siro (1931–1952) | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.22 | 0.14 |

| Quartiere Sant’Ambrogio (1964–1972) | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.22 | 0.08 |

| Quartiere degli Olmi (1965–1970) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.00 |

| Quarto Cagnino | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.31 | 0.07 |

| Quarto Oggiaro (1960–1962)) | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.26 | 0.12 |

| V.Le Omero Via Barabino | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.22 | 0.12 |

| Vialba (1957–1960) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

Table A3.

Community review area analysis.

Table A3.

Community review area analysis.

| Community | Avg Sentiment | Avg Year | Area (sqm) | Reviews/10k Sqm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forlanini (1959) | 0.47 | 2023.84 | 555,437.92 | 1.35 |

| Gallaratese G1 (1967–1972) | 0.47 | 2023.26 | 1,142,790.31 | 0.66 |

| Gallaratese G2 (1974–1976) | 0.28 | 2024.00 | 587,115.75 | 0.55 |

| Lambrate | 0.43 | 2023.20 | 251,492.71 | 2.62 |

| Morsenchio | 0.59 | 2024.47 | 215,226.83 | 0.74 |

| Morsenchio 2 | 0.58 | 2024.05 | 78,979.25 | 5.06 |

| Pezzotti | 0.52 | 2023.19 | 36,728.00 | 19.06 |

| Ponte Lambro (1960~1975) | 0.19 | 2023.24 | 62,733.38 | 4.78 |

| Prato Centenaro | 0.61 | 2024.24 | 175,734.65 | 2.11 |

| Quartiere 8 (1946–1954) | −0.06 | 2023.60 | 966,848.71 | 0.05 |

| Quartiere Ca’ Granda (1972–1977) | 0.57 | 2023.91 | 21,477.43 | 58.20 |

| Quartiere Chiesa Rossa (1960–1966) | 0.58 | 2023.19 | 212,965.78 | 3.43 |

| Quartiere Comasina (1953–1969) | 0.54 | 2023.93 | 366,327.09 | 2.10 |

| Quartiere Gratosoglio Missaglia (1968–1972) | 0.47 | 2023.47 | 153,822.03 | 3.97 |

| Quartiere Gratosoglio (1963–1971) | 0.65 | 2023.49 | 501,140.08 | 1.50 |

| Quartiere Lorenteggio (Inganni) (1938–1944) | 0.71 | 2023.47 | 111,283.02 | 2.61 |

| Quartiere Lorenteggio (Il Giambellino) (1938–1944) | 0.51 | 2023.83 | 158,057.22 | 0.76 |

| Quartiere S.Siro (1931–1952) | 0.44 | 2023.58 | 294,544.82 | 2.51 |

| Quartiere Sant’Ambrogio (1964–1972) | 0.37 | 2023.52 | 288,764.24 | 1.90 |

| Quartiere degli Olmi (1965–1970) | −0.02 | 2022.95 | 197,751.49 | 0.86 |

| Quarto Cagnino | 0.65 | 2024.17 | 107,077.96 | 2.15 |

| Quarto Oggiaro (1960–1962) | 0.48 | 2023.61 | 959,362.78 | 0.83 |

| V.Le Omero Via Barabino | 0.39 | 2023.84 | 77,885.95 | 7.83 |

| Vialba (1957–1960) | 0.34 | 2023.00 | 402,486.76 | 0.02 |

Table A4.

Community Short Code and Cluster Label Mapping Table.

Table A4.

Community Short Code and Cluster Label Mapping Table.

| Community | ShortCode | Cluster Label |

|---|---|---|

| Forlanini (1959) | Ph-2 | Ph |

| Gallaratese G1 (1967–1972) | Ph-3 | Ph |

| Gallaratese G2 (1974–1976) | Ph-4 | Ph |

| Lambrate | Ph-5 | Ph |

| Morsenchio | So-6 | So |

| Morsenchio 2 | Po-7 | Po |

| Pezzotti | Ph-8 | Ph |

| Ponte Lambro (1960~1975) | Ph-9 | Ph |

| Prato Centenaro | Po-10 | Po |

| Quartiere 8 (1946–1954) | Ch-11 | Ch |

| Quartiere Ca’ Granda (1972–1977) | Po-12 | Po |

| Quartiere Chiesa Rossa (1960–1966) | Ch-13 | Ch |

| Quartiere Comasina (1953–1969) | Po-14 | Po |

| Quartiere Gratosoglio Missaglia (1968–1972) | Ph-15 | Ph |

| Quartiere Gratosoglio (1963–1971) | Po-16 | Po |

| Quartiere Lorenteggio (Inganni) (1938–1944) | Ch-17 | Ch |

| Quartiere Lorenteggio (Il Giambellino) (1938–1944) | Ph-18 | Ph |

| Quartiere S.Siro (1931–1952) | Ph-19 | Ph |

| Quartiere Sant’Ambrogio (1964–1972) | Ph-20 | Ph |

| Quartiere degli Olmi (1965–1970) | So-21 | So |

| Quarto Cagnino | Po-22 | Po |

| Quarto Oggiaro (1960–1962) | Ph-23 | Ph |

| V.Le Omero Via Barabino | Ph-24 | Ph |

| Vialba (1957–1960) | So-25 | So |

Table A5.

Overall distribution of refined review target place types in Milan’s ERP estates.

Table A5.

Overall distribution of refined review target place types in Milan’s ERP estates.

| Place Type Refined | Count | Share |

|---|---|---|

| others unspecified | 911 | 0.639 |

| private commercial services | 166 | 0.116 |

| retail daily services | 125 | 0.088 |

| community civic centers | 63 | 0.044 |

| housing authority office | 56 | 0.039 |

| residential named places | 31 | 0.022 |

| schools childcare | 30 | 0.021 |

| parks green spaces | 29 | 0.020 |

| local institutions | 10 | 0.007 |

| transit mobility | 4 | 0.003 |

Figure A1.

Community level PSQI sensitivity to review target composition across Milan’s ERP estates.

Figure A1.

Community level PSQI sensitivity to review target composition across Milan’s ERP estates.

Figure A2.

Distribution of PSQI sensitivity across memory–behavior groups.

Figure A2.

Distribution of PSQI sensitivity across memory–behavior groups.

References

- Baldwin Hess, D.; Tammaru, T.; Van Ham, M. Housing Estates in Europe: Poverty, Ethnic Segregation and Policy Challenges; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schönig, B. Paradigm shifts in social housing after welfare-state transformation: Learning from the German experience. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2020, 44, 1023–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, R. La Casa Popolare in Lombardia 1903–2003; Unicopli: Trezzano sul Naviglio, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wassenberg, F. Large Housing Estates: Ideas, Rise, Fall and Recovery: The Bijlmermeer and Beyond; Ios Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 48. [Google Scholar]

- Aernouts, N.; Maranghi, E.; Ryckewaert, M. The Regeneration of Large-Scale Social Housing Estates: Spatial, Territorial, Institutional and Planning Dimensions. 2020. Available online: https://re.public.polimi.it/handle/11311/1147130 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Di Biagi, P. La Grande Ricostruzione: Il Piano Ina-Casa e l’Italia Degli Anni Cinquanta; Donzelli Editore: Roma, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Petsimeris, P. Urban decline and the new social and ethnic divisions in the core cities of the Italian industrial triangle. Urban Stud. 1998, 35, 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lettini, L.; Gambirasio, R. Gratosoglio: Il Tassello Verde. Un Esempio di Progettazione Integrata per la Periferia Pubblica Milanese; Politecnico di Milano: Milan, Italy, 2011; Available online: https://www.politesi.polimi.it/handle/10589/19181 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Lucchini, M. The Quarto Cagnino District in Milan (1964–1973): Rationalist Figuration for a New Dimension of the Urban Space. ZARCH 2015, 5, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittorini, R. Reconstructing housing and communities: The INA-Casa Plan. Docomomo J. 2021, 65, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petsimeris, P.; Niarimoldi, S.F. Socio-economic divisions of space in Milan in the post-Fordist era. In Socio-Economic Segregation in European Capital Cities; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2015; pp. 186–213. [Google Scholar]

- Wassenberg, F. Large social housing estates: From stigma to demolition? J. Hous. Built Environ. 2004, 19, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tattara, M.; Migotto, A. Contested Legacies: Critical Perspectives on Postwar Modern Housing; Project MUSE: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolt, G. Who is to blame for the decline of large housing estates? An exploration of socio-demographic and ethnic change. In Housing Estates in Europe: Poverty, Ethnic Segregation and Policy Challenges; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. The Regeneration of Social Housing Estates in Italy. The Case of the Mazzini Neighborhood in Milano. Master’s Thesis, Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Musterd, S. Residents’ views on social mix: Social mix, social networks and stigmatisation in post-war housing estates in Europe. Urban Stud. 2008, 45, 897–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacquant, L. Urban Outcasts: A Comparative Sociology of Advanced Marginality; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tosi, A.; Cremaschi, M. Housing Policies in Italy; Interdisciplinary Centre for Comparative Research in Social Sciences: Vienna, Austria, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bricocoli, M.; Sabatinelli, S. Città, welfare e servizi: Temi e questioni per il progetto urbanistico e le politiche sociali. Territorio 2018, 83, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bricocoli, M.; Savoldi, P. Milano Downtown. Azione Pubblica e Luoghi Dell’abitare; et al./EDIZION: Milan, Italy, 2010; pp. 1–277. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282643269_Milano_downtown_Azione_pubblica_e_luoghi_dell’abitare (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Stefanizzi, S.; Verdolini, V. A “space” of one’s own: Identity and conflict in two Milan districts. Qual. Quant. 2022, 56, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degen, M.M.; Rose, G. The sensory experiencing of urban design: The role of walking and perceptual memory. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 3271–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Liu, Y.; Kang, Y.; Zhang, F. User-generated content: A promising data source for urban informatics. In Urban Informatics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 503–522. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Y.; Liang, J.; Guan, C. Decoding public sentiment topics in google map reviews on urban infrastructure development of belt and road initiative. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.; Sun, M. Understanding park-based health-promoting behavior and emotion with large-scale social media data: The case of Tianjin, China. Cities 2025, 162, 105987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, L. Insights into People’s Perceptions Towards Urban Public Spaces Through Analysis of Social Media Reviews: A Case Study of Shanghai. Buildings 2025, 15, 3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, C.; Rong, L.; Zhou, S.; Wu, Z. Understanding How People Perceive and Interact with Public Space through Social Media Big Data: A Case Study of Xiamen, China. Land 2024, 13, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nae, M.; Dumitrache, L. Bucharest Old Town: Exploring city tourism experiences via TripAdvisor. In Landscape–Tourism–Food: Contributions to European Touristscapes and Foodscapes; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 83–103. [Google Scholar]

- López-Chao, V.; Lopez-Pena, V. Aesthetical appeal and dissemination of architectural heritage photographs in instagram. Buildings 2020, 10, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbwachs, M. On Collective Memory; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Connerton, P. How Societies Remember; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, J. Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Filomena, G.; Verstegen, J.A.; Manley, E. A computational approach to ‘The Image of the City’. Cities 2019, 89, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nora, P. Memory and history: Les lieux de mémoire. In Theories of Memory: A Reader; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2019; p. 144. [Google Scholar]

- Hutto, C.; Gilbert, E. VADER: A parsimonious rule-based model for sentiment analysis of social media text. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media; AAAI: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2014; Volume 8, pp. 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Veen, A.M.; Bleich, E. The advantages of lexicon-based sentiment analysis in an age of machine learning. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0313092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Pérez, R.; Lara-Martínez, P.; Obregón-Quintana, B.; Liebovitch, L.S.; Guzmán-Vargas, L. Correlations and fractality in sentence-level sentiment analysis based on Vader for literary texts. Information 2024, 15, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.; Pereira, A.; Benevenuto, F. A comparative study of machine translation for multilingual sentence-level sentiment analysis. Inf. Sci. 2020, 512, 1078–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Ma, S.; Meng, J.; Zhuang, J.; Peng, T.-Q. Detecting sentiment toward emerging infectious diseases on social media: A validity evaluation of dictionary-based sentiment analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A.; Levy-Storms, L.; Chen, L.; Brozen, M. Parks for an aging population: Needs and preferences of low-income seniors in Los Angeles. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2016, 82, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobster, P.H. Perception and use of a metropolitan greenway system for recreation. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 33, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedimo-Rung, A.L.; Mowen, A.J.; Cohen, D.A. The significance of parks to physical activity and public health: A conceptual model. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A.; Sommerhalder, K.; Abel, T. Landscape and well-being: A scoping study on the health-promoting impact of outdoor environments. Int. J. Public Health 2010, 55, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Bosch, M.; Sang, Å.O. Urban natural environments as nature-based solutions for improved public health: A systematic review of reviews. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Shmelova-Nesterenko, O. Exploring urban streetscape design: Comprehensive review of scientific research. Art Des. 2023, 4, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. Public Places Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Imrie, R. From universal to inclusive design in the built environment. In Disabling Barriers–Enabling Environments; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 279–284. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper Marcus, C.; Sarkissian, W. Housing as If People Mattered: Site Design Guidelines for Medium-Density Family Housing; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Preiser, W.F.E.; Rabinowitz, H.Z.; White, E.T. Post-Occupancy Evaluation; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, R.; Kintrea, K. Owner-occupation, social mix and neighbourhood impacts. Policy Politics 2000, 28, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, D. The power of place: Claiming urban landscapes as people’s history. J. Urban Hist. 1994, 20, 466–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinenberg, E. Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life; Crown: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. In Culture and Politics: A Reader; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 223–234. [Google Scholar]

- Manzo, L.C. Beyond house and haven: Toward a revisioning of emotional relationships with places. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M.C.; Hernandez, B. Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojanowski, P.; Grave, E.; Joulin, A.; Mikolov, T. Enriching word vectors with subword information. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2017, 5, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grave, E.; Bojanowski, P.; Gupta, P.; Joulin, A.; Mikolov, T. Learning word vectors for 157 languages. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2018); European Language Resources Association: Miyazaki, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vuli’c, I.; Glavaš, G.; Liu, F.; Collier, N.; Ponti, E.M.; Korhonen, A. Probing cross-lingual lexical knowledge from multilingual sentence encoders. In Proceedings of the 17th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics; ACL: Dubrovnik, Croatia, 2023; pp. 2089–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozarth, L.; Budak, C. Keyword expansion techniques for mining social movement data on social media. EPJ Data Sci. 2022, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, J.; Lee, S. Enhancement of text analysis using context-aware normalization of social media informal text. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsevier. (n.d.). Sentiment Score. In *ScienceDirect Topics*. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/computer-science/sentiment-score (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Bondarchuk, N.; Bekhta, I.; Melnychuk, O.; Matviienkiv, O. Keyword-based Study of Thematic Vocabulary in British Weather News. COLINS 2022, 451–460. [Google Scholar]

- Mohseni, M.; Redies, C.; Gast, V. Comparative Analysis of Preference in Contemporary and Earlier Texts Using Entropy Measures. Entropy 2023, 25, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Herthogs, P.; Cinelli, M.; Tomarchio, L.; Tunçer, B. A multi-criteria decision analysis based framework to evaluate public space quality. In Smart and Sustainable Cities and Buildings; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 271–283. [Google Scholar]

- Praliya, S.; Garg, P. Public space quality evaluation: Prerequisite for public space management. J. Public Space 2019, 4, 93–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trolese, M.; De Fabiis, F.; Coppola, P. A walkability index including pedestrians’ perception of built environment: The case study of Milano Rogoredo Station. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfgring, C. Public housing and the PINQuA in Italy. Urban Res. Pract. 2023, 16, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment, place identity, and place memory: Restoring the forgotten city past. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pink, S. Situating Everyday Life: Practices and Places; Sage: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargittai, E. Potential biases in big data: Omitted voices on social media. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2020, 38, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohme, J.; Araujo, T.; Boeschoten, L.; Freelon, D.; Ram, N.; Reeves, B.B.; Robinson, T.N. Digital trace data collection for social media effects research: APIs, data donation, and (screen) tracking. Commun. Methods Meas. 2024, 18, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, S.M. Sentiment analysis: Automatically detecting valence, emotions, and other affectual states from text. In Emotion Measurement; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 323–379. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C.; Wu, M.; Yang, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, S.; Wang, S.; Li, D. A systematic review of cross-lingual sentiment analysis: Tasks, strategies, and prospects. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccabruna, G.; Azzolin, S.; Riccardi, G. Multi-source multi-domain sentiment analysis with BERT-based models. In European Language Resources Association; European Language Resources Association: Miyazaki, Japan, 2022; pp. 581–589. [Google Scholar]

- Catelli, R.; Bevilacqua, L.; Mariniello, N.; di Carlo, V.S.; Magaldi, M.; Fujita, H.; De Pietro, G.; Esposito, M. Cross lingual transfer learning for sentiment analysis of Italian TripAdvisor reviews. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 209, 118246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.