Abstract

This study investigates the challenge of affordable housing in Riyadh, a city undergoing rapid transformation aligned with Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030. It aims to bridge the structural gap in the housing market by developing a comprehensive analytical framework that measures housing suitability for emerging middle-income families, linking it to economic, spatial, and behavioral dimensions. The research employs a sequential mixed-methods design. The first phase involved a Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) of 106 residential neighborhoods, constructing a Housing Suitability Index (HSI) based on financing cost (≤SAR 880,000), quality of urban life, and geographical accessibility. The second phase utilized focus groups with 16 participants from real estate developers and new families to explore behavioral drivers and subjective trade-offs. Quantitative results identified “convenience clusters” primarily in the city’s southeastern and southwestern sectors, offering an optimal balance between price and accessibility. Qualitative analysis revealed a significant trust gap and a misalignment of priorities: new families are increasingly willing to sacrifice unit size for central location and construction quality, a preference that conflicts with developers’ strategies focused on luxury units or peripheral projects for higher margins. The study concludes that achieving the 70% homeownership target requires a hybrid policy model, combining supply-side stimuli (e.g., subsidized land) with demand-side management (e.g., progressive mortgages). It recommends integrating the HSI into urban planning to direct investment towards logistically connected areas, fostering sustainable communities.

1. Introduction

Housing constitutes a fundamental pillar of social stability and economic development in contemporary cities, particularly in dynamic urban environments like Riyadh. The Saudi capital is experiencing profound structural changes under the Kingdom’s Vision 2030, a national transformation framework that explicitly targets raising the rate of homeownership to 70 per cent [1]. This ambition, however, unfolds within a context of intense demographic and socio-economic shifts. Riyadh’s population has reached 8.59 million, with a notably young demographic where approximately 63 per cent of citizens are under 30, continuously generating new household formation pressures [2,3]. Consequently, the traditional definition of housing need, centered merely on shelter, is rapidly evolving. The contemporary Saudi family, especially new families forming in the mid-2020s, seeks a home that ensures functional efficiency and is seamlessly integrated into the city’s urban and logistical fabric [4].

This shift in demand coincides with a strategic move in national housing policy from a “quantity of production” focus to a “quality of fit” paradigm. Yet, Riyadh’s historical pattern of horizontal urban expansion has created significant spatial and economic disparities [5]. A stark dichotomy exists between the high cost of development driven significantly by land price inflation in prime northern areas and the constrained purchasing power of middle-income households [6,7]. This has resulted in a persistent “mismatch” or structural gap between market supply and household aspirations, often manifesting as a “Missing Middle” a dearth of well-located, quality, mid-priced housing [8].

Therefore, understanding Riyadh’s housing dynamics necessitates moving beyond abstract price analyses. There is a pressing need for interdisciplinary research that integrates urban economic indicators with the behavioral logic of market actors both the demand side (new families) and the supply side (developers). This research answers that call by adopting a sequential explanatory mixed-methods framework [9]. It first employs a quantitative approach, using Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) to construct a Housing Suitability Index (HSI). This index synthesizes cost, built environment quality, and logistical accessibility into a spatial map of 106 neighborhoods. This quantitative mapping is then enriched and explained through qualitative focus groups, delving into the decision-making “logics,” perceptions, and trade-offs that statistics alone cannot reveal.

The study’s primary value lies in its integrated diagnostic model, which rigorously links “spatial numbers” with “behavioral stories.” This provides policymakers, planners, and developers with a nuanced, evidence-based tool to identify specific market failures and guide interventions toward sustainable, resident-centric housing solutions, ultimately supporting the nuanced achievement of Vision 2030’s housing objectives.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature on housing affordability and suitability. Section 3 details the sequential mixed-methods methodology, comprising the quantitative MCDA and the qualitative focus group analysis. Section 4 presents the results of both phases. Section 5 discusses these findings in the context of existing research and policy. Finally, Section 6 concludes with policy implications and recommendations for future research.

2. Literature

The academic and policy discourse on affordable housing has undergone a profound evolution, shifting from a narrow, financial-cost perspective to a holistic concept of “housing adequacy” and “spatial justice.” This chapter establishes the theoretical and contextual foundation for this study by critically reviewing established scientific concepts, recent empirical analyses of the Saudi context, and international policy lessons. It synthesizes this body of work to argue that understanding Riyadh’s housing market for new families requires an integrated analysis of economic constraints, urban spatial dynamics, quality-of-life considerations, and behavioral decision-making.

2.1. The Evolving Concept of Housing Affordability and Suitability

Historically, housing affordability was primarily defined by a simple financial ratio of the relationship between housing costs and household income. The widely cited 30% threshold, beyond which households are considered “cost-burdened,” originates from this paradigm [10]. However, contemporary scholarship robustly critiques this one-dimensional view as inadequate for capturing the true experience of residents, particularly in rapidly urbanizing contexts.

The modern concept of housing adequacy or housing suitability integrates three sovereign dimensions: financial capacity, quality of the living environment, and geographical accessibility. This aligns with the global shift toward “people-centered” urban development championed by UN-Habitat. Its Quality of Life Initiative explicitly promotes a “comprehensive, human-centric concept of quality of life including objective and subjective factors” as a primary urban development goal [5]. This framework moves beyond shelter to assess the quality of infrastructure, availability of health and educational facilities, access to green spaces, and the overall “capability” a location provides for its residents.

Critical to this holistic view is the integration of the “cost of place.” Researchers like Geurs and van Wee [11] have long argued that the true cost of housing must include the “location tax” of land prices and the ongoing “transportation cost” of commuting. A home with a low purchase price but poor accessibility to jobs and services imposes significant hidden financial and time burdens, effectively eroding its affordability. This perspective frames housing as a structural phenomenon directly linked to social stability and economic productivity, where spatial mismatch between homes and opportunities constitutes a form of urban inequality [12].

2.2. The Saudi Context: Vision 2030, Demographics, and Market Dynamics

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia presents a critical case study of these global housing dynamics within a unique socio-political and economic context. The launch of Saudi Vision 2030 represents a fundamental renegotiation of the decades-old “social contract,” whereby the state distributed oil wealth through public sector employment, subsidies, and welfare services [1]. Vision 2030 explicitly aims to diversify the economy, increase private sector employment, and foster a more productive and financially independent citizenry.

The Housing Program, a key pillar of Vision 2030, is not merely a quantitative target of 70% homeownership but a strategic lever for this broader transformation [13]. It seeks to shift the housing sector from a rentier model to a productive, market-driven industry that contributes to economic resilience and provides “integrated communities” [14]. This ambition is operationalized through giga-projects and national developers like ROSHN Group, described as a “key enabler” tasked with developing “integrated, human-centric communities” that elevate quality of life.

This reform unfolds under intense demographic pressure. With approximately 60% of Saudis under the age of 30, the demand for new household formation is immense. As noted in qualitative research, for young Saudi men, securing a stable, well-paid job traditionally in the public sector is intrinsically linked to marriage prospects and independent living [3]. Consequently, the dual challenges of youth unemployment and housing affordability are deeply intertwined, placing the social contract under significant strain. The government’s response through Vision 2030, therefore, addresses a pressing socio-economic imperative; providing housing and economic opportunity to a vast youth cohort is essential for long-term stability. Furthermore, Riyadh’s real estate market is experiencing nuanced, product-specific trends. While the overall market grows robustly, projected at an 8% CAGR, 2025 data shows a divergence: villa prices continued to rise by 3.2%, catering to demand for space and privacy, while apartment prices saw a slight decline of 0.7% [6].

2.3. International Policy Models and Behavioral Insights

Global experiences offer valuable, if context-dependent, lessons for Riyadh’s housing policy. A comparative analysis reveals distinct models with relevant insights. The Chinese “land-finance” model [15] demonstrates how rapid urbanization can be financed through land sales, but over-reliance on developer debt and speculation risks market instability. Austria’s Vienna Model [16] shows that large-scale, non-profit provision of housing can ensure affordability and quality. The UK’s “Right to Buy” policy [17] boosted ownership rates short-term but depleted affordable rental stock long-term. Singapore’s supply-side incentives highlight the necessity of the state as a master planner to correct acute market failures [18].

Beyond economics and policy, housing choice is a profoundly behavioral and psychological process. Recent studies in Riyadh and the broader GCC indicate a shift in the “psychology of the buyer,” particularly among new generations. The purchase decision involves complex, multi-attribute trade-offs where the size of the dwelling is weighed against geographical accessibility, quality of construction, and the social prestige of the neighborhood [19].

2.4. Research Gap and Study Hypotheses

This review establishes that affordable housing in Riyadh is a multifaceted problem situated at the intersection of macro-economic transformation, urban spatial economics, and evolving socio-cultural behaviors. While Vision 2030 sets a clear quantitative target, the academic and empirical literature highlights a structural misalignment: a supply side incentivized by land economics to produce luxury goods or peripheral bulk housing, and a demand side composed of new families seeking affordable, well-connected, and quality-assured homes.

Existing studies, including economic analyses of price trends, policy evaluations of Vision 2030 programs, and spatial studies of urban form, often analyze these dimensions in isolation. There is a distinct gap in research that integrates the quantitative spatial analysis of affordability with a qualitative, behavioral investigation of the decision-making logics of both developers and new families. This study aims to fill this gap. By employing a mixed-methods approach, it seeks to construct a comprehensive Housing Suitability Index (HSI) that operationalizes the holistic affordability framework and then deconstructs the behavioral trade-offs and market perceptions that explain the index’s outcomes. In doing so, it provides a diagnostic tool and evidence base for crafting the “hybrid” policies necessary to bridge Riyadh’s housing suitability gap.

3. Materials and Methods

This study employs a sequential explanatory mixed-methods design [9]. The initial quantitative phase identifies and measures spatial patterns of housing suitability. The subsequent qualitative phase then explores the behavioral and perceptual reasons behind these patterns, providing the results with depth and explanation.

3.1. Quantitative Phase: Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA)

The quantitative analysis assesses 106 neighborhoods across Riyadh. Spatial data analysis was performed using QGIS software (version 3.28; QGIS.org, 2023). Data was gathered through a hybrid digital survey for 2025, integrating official records and real-time data from real estate platforms. Prices for target products (3-bedroom apartments, 250 m2 villas) were adjusted for variables like street width and construction quality to ensure comparability. Three sovereign variables were defined:

- Financing Cost: A ceiling of SAR 880,000 was set for a 3-bedroom apartment, based on the purchasing power of a household with a monthly income of ~SAR 10,500, allowing for a sustainable mortgage payment not exceeding 35–45% of income [20,21].

- Quality of Urban Life: Measured on a 1–5 scale using criteria derived from UN-Habitat indicators [5], including infrastructure, health/education facilities, and green space.

- Geographical Accessibility: Measured on a 1–5 scale based on connectivity to major roads, the city center, and public transit nodes like the Riyadh Metro [22].

A strict exclusion rule was applied: any neighborhood where the apartment price exceeded SAR 880,000, or where either quality or accessibility scored below 3, was assigned a preliminary HSI of zero.

Index Construction and Weighting Rationale: For neighborhoods passing the thresholds, data was normalized. The price variable was reverse-coded so that a lower price yielded a higher score. The HSI was calculated as a weighted sum: HSI = (0.50 × Normalized Price Score) + (0.25 × Quality Score) + (0.25 × Accessibility Score). This weighting structure reflects the foundational principle that for middle-income, first-time buyers, financial feasibility is the primary gatekeeper to homeownership. The 50% weight for financing cost aligns with the residual income approach to affordability, which prioritizes the household’s ability to cover non-housing necessities after mortgage payments [10]. The equal 25% allocation to quality and accessibility operationalizes the holistic “suitability” framework, acknowledging that true affordability is eroded by poor living conditions or excessive commuting costs [11]. While alternative weightings are possible, this structure is logically derived from the literature and is explicitly tested through sensitivity analysis in the results via alternative models (e.g., price-sensitive vs. quality-of-life models). The MCDA approach follows established methodologies in housing suitability assessment [23,24].

3.2. Qualitative Phase: Focus Group Analysis

This phase served as a “behavioral laboratory” to interpret quantitative findings. Two focus groups were conducted with 16 total participants:

- Group A (Supply-side): This cohort consisted of eight participants from real estate development firms. The sample was split equally between four decision-makers from major national developers (portfolios exceeding 1000 units) and four from mid-sized local firms (portfolios exceeding 100 units), capturing a range of supply-side perspectives. Demographically, the group was predominantly male (7, 87.5%), with one female participant (1, 12.5%). Regarding educational attainment, 37.5% (3) held Bachelor’s degrees, while 62.5% (5) possessed postgraduate qualifications (Master’s/PhD). All eight participants (100%) were actively employed.

- Group B (Demand-side): This group comprised eight participants representing the demand-side of the market, specifically heads of new families (household formation within the last 5 years). All participants belonged to the target middle-income bracket, with confirmed household incomes between SAR 10,000 and SAR 16,000 per month. The gender composition included six males (75%) and two females (25%). Educationally, 62.5% (5) held a Bachelor’s degree, while 37.5% (3) held a Master’s or PhD. All participants (100%) were employed heads of households. This cohort was recruited through two primary channels: (1) collaboration with real estate agencies to access active clients, and (2) university alumni networks to reach graduates who started families within the last three years.

Participant selection aimed for information richness regarding the core research problem. Sessions were semi-structured, prompting discussion on trade-offs between location, space, and cost, as well as perceptions of market trust and quality. Discussions were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using thematic analysis [25]. The sample size was determined by the principle of thematic saturation, where subsequent interviews yield minimal new insights on the core themes [25]. Data collection ceased after the two focus groups, as analysis indicated recurring patterns and sufficient depth on the key topics of trade-offs, trust, and misaligned priorities, thereby ensuring analytical validity within the scope of this explanatory phase.

4. Results

This section presents the findings of the mixed-methods analysis, beginning with a detailed exposition of the quantitative spatial and economic patterns derived from the Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA). It then delves into the rich qualitative themes extracted from the focus group discussions, which provide the behavioral and perceptual context essential for interpreting the numerical data.

4.1. Qualitative Spatial Analysis: Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA)

The MCDA of 106 neighborhoods in Riyadh for 2025 reveals a city segmented by profound economic and spatial inequalities. The following analyses detail the constituent variables of the Housing Suitability Index (HSI) and their integrated outcomes. The MCDA of 106 neighborhoods in Riyadh for 2025 reveals a city segmented by profound economic and spatial inequalities. The following analyses detail the constituent variables of the Housing Suitability Index (HSI) and their integrated outcomes.

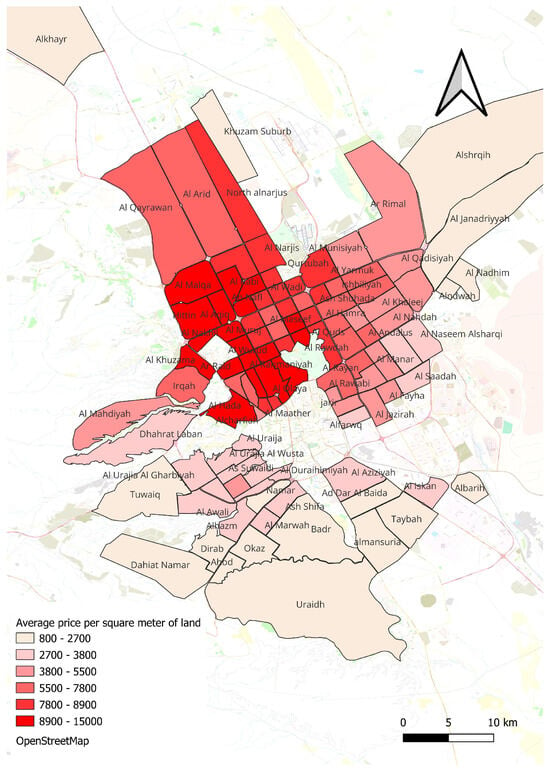

The analysis of average land prices per square meter establishes the primary economic geography of Riyadh, serving as the fundamental driver of all subsequent housing product costs and development feasibility. The data reveals a stark bipolar urban structure (Figure 1). The northern axis of the city, encompassing prestigious neighborhoods such as Al-Malqa, Hittin, and Al-Nakheel, demonstrates extreme price resilience, with values stabilizing at historically high levels between SAR 7500 and SAR 9500 per square meter. This premium reflects the value of “spatial capital” proximity to flagship Vision 2030 giga-projects like King Abdullah Financial District, coupled with mature, high-quality infrastructure and exclusive services. This dynamic has effectively transformed northern land from a factor for housing production into a high-value speculative investment asset, creating a price chasm of up to 500% when compared to the urban periphery.

Figure 1.

Average price per square meter of land.

In direct contrast, neighborhoods at the far southern and northern edges of the capital, such as Aradeed, Al Khair, and Mansouriya, present a radically different reality, with land prices ranging from SAR 1800 to SAR 2800 per square meter. These areas represent the primary locations for cost-constrained development. This pattern indicates a process of “spatial filtration,” where prohibitively expensive land in the core and north displaces development pressure toward the south and west. This expansion is not driven by strategic urban design or resident preference but is a direct consequence of escaping central price pressures. Consequently, the cost of land remains the paramount determinant of the eventual housing product’s quality, typology, and target demographic.

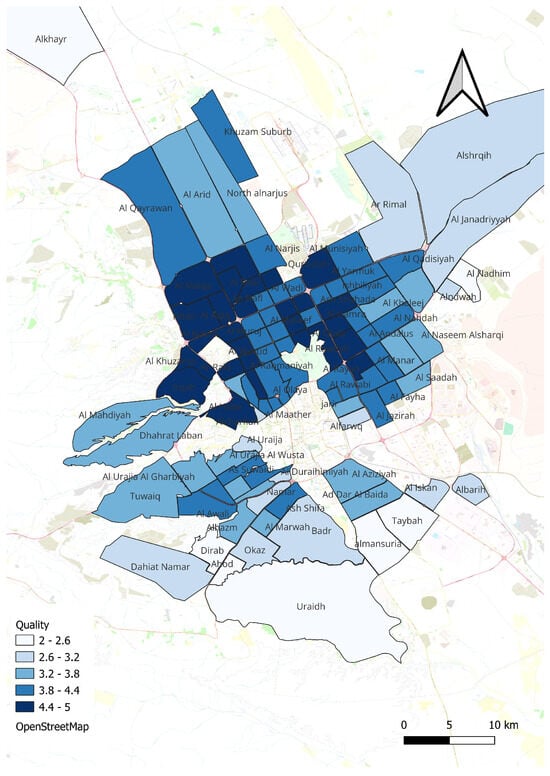

Evaluated using criteria adapted from UN-Habitat indicators, including infrastructure robustness, availability of health and educational facilities, and per capita green space, the Quality of Life Index exposes the human cost of spatial inequality (Figure 2). Central and long-established northern neighborhoods like Al-Sulaymaniyah, Al-Maathar, Al-Nuzha, and Al-Waha achieve perfect scores of 5 out of 5. This reflects decades of cumulative public investment in social and physical infrastructure, offering residents integrated, walkable environments with immediate access to amenities.

Figure 2.

Quality of Life Index.

Conversely, the neighborhoods identified as financially affordable, such as Aradeed, Mansouriya, and Al Khair, score markedly low, between 1 and 2.5. Residents here face significant deficits: a severe lack of parks and recreational spaces, limited access to major retail or specialized healthcare, and underdeveloped utilities like street lighting in newer subdivisions. This inverse correlation between affordability and quality of life poses a critical challenge. It demonstrates that in Riyadh’s current market, a high-quality living environment commands a direct and substantial price premium, effectively placing it beyond the reach of middle-income new families. This threatens to create a two-tier city, where affordable housing is synonymous with compromised well-being, demanding urgent policy intervention to elevate service levels in these peripheral zones.

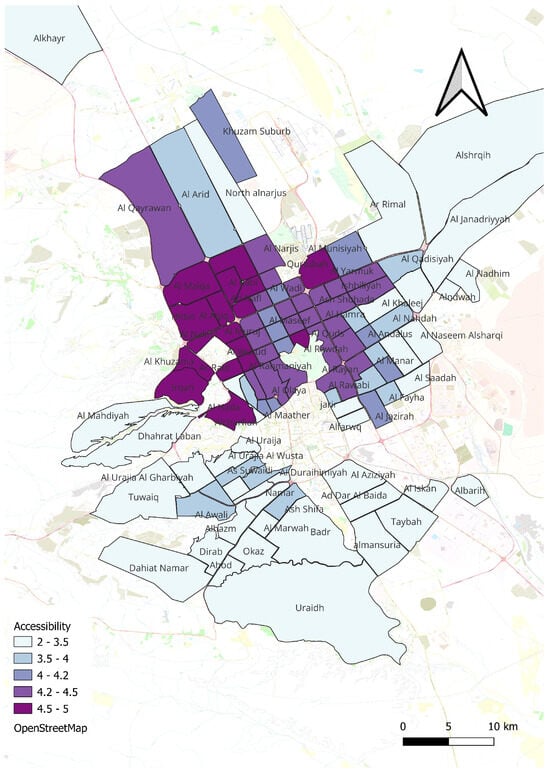

The Accessibility Index, measuring the efficiency of connection to the city’s administrative-financial core and major transport arteries, has emerged as a non-negotiable criterion for modern living, defining the “hidden cost” of housing (Figure 3). Core districts like Al-Olaya, King Fahd, and Al-Maathar score a maximum 5/5, benefiting from their position at key motorway junctions and proximity to primary Riyadh Metro stations, drastically reducing the daily opportunity cost of commuting time.

Figure 3.

Accessibility Index.

In stark contrast, peripheral neighborhoods like Aradeed (south) and Al Khair (north) score a minimal 1/5, implying resident commutes of two hours or more per day, a significant financial and physiological burden absent from the initial purchase price. Notably, some geographically proximal neighborhoods like Laban, Mahdia, and Dhahrat Laban score only a medium 3/5 due to constrained road access and chronic congestion at key intersections. This confirms that in 2025, “location” is measured not in kilometers but in minutes and reliability. It rationalizes a buyer’s preference for a SAR 850,000 apartment in the well-connected King Faisal neighborhood (accessibility: 4.5) over a SAR 500,000 unit in a poorly connected area, as the price difference is inevitably consumed by higher transportation expenses and lost time.

The application of the SAR 880,000 affordability ceiling produces divergent realities for different housing typologies, highlighting a major shift in the city’s residential fabric.

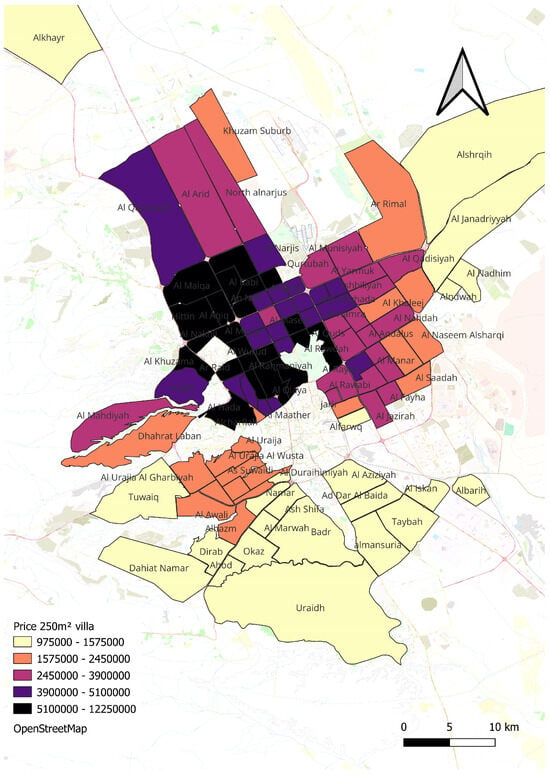

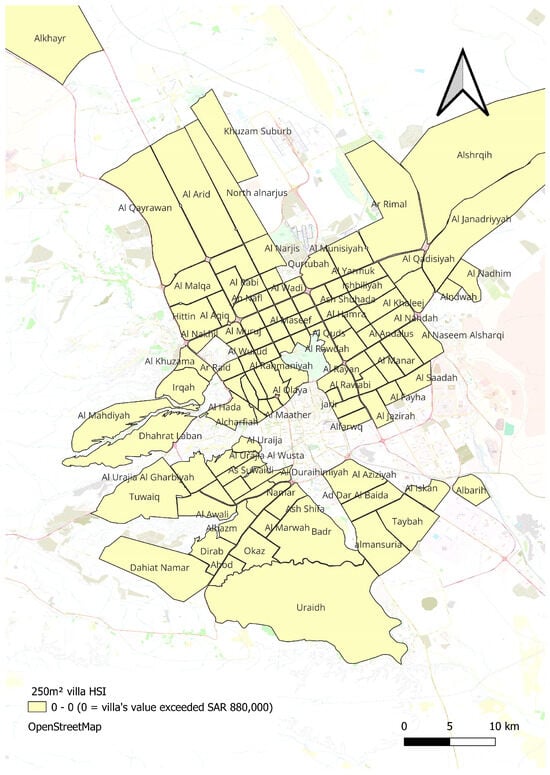

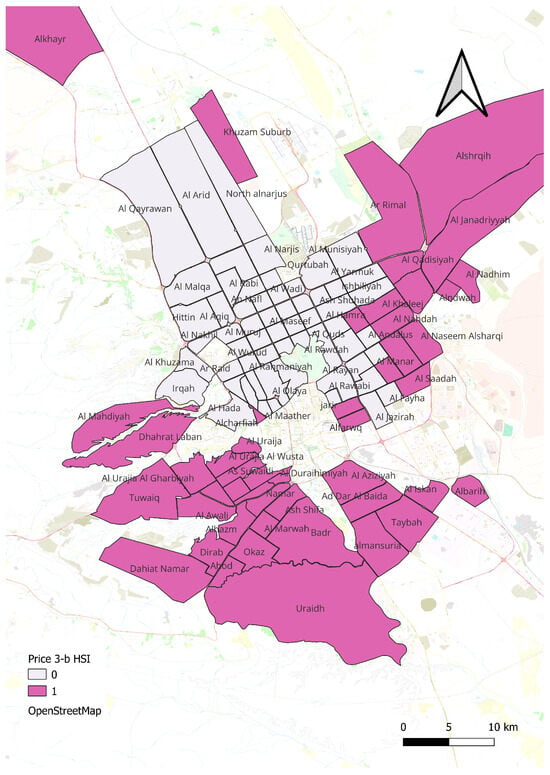

The Villa Market: The analysis of 250 m2 villas reveals a market segment that has become largely detached from the financial reality of new families (Figure 4). In coveted northern areas like Al-Yasmeen, Nargis, and Hittin, villa prices comfortably exceed SAR 3.5 million, cementing their status as elite products. While “affordable” villas in the SAR 1.1 to 1.35 million range exist in far-flung areas like Taybeh, Dirab, and Namar, they come with the heavy, hidden costs of distance and poor accessibility. The binary HSI for Villas (Figure 5) renders this exclusion starkly: almost every neighborhood in the developed urban area scores 0, failing the price ceiling. A score of 1 appears only in exceptional peripheral cases, and even then, often presupposes sacrifices in build quality or plot size. This is a definitive quantitative finding: the traditional standalone villa is no longer a viable product for the target demographic under prevailing market conditions.

Figure 4.

Price of 250 m2 villa.

Figure 5.

Residential Suitability Index for Villas (HSI Villa).

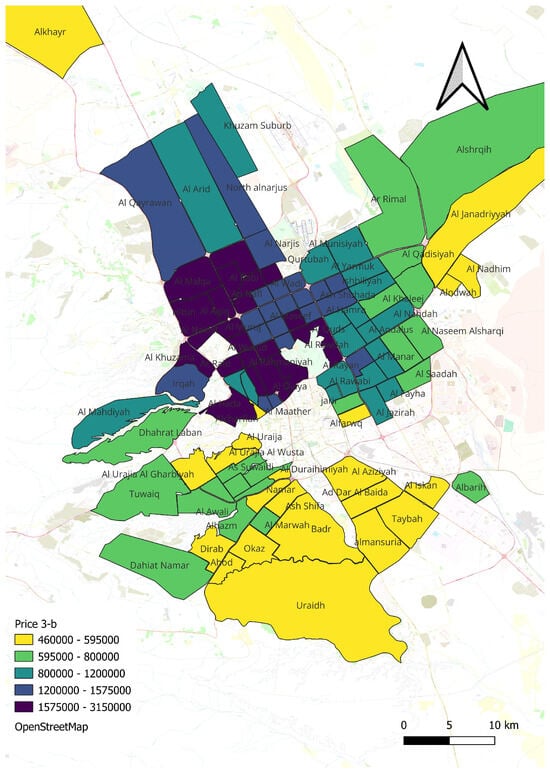

The Apartment Market: In contrast, the three-bedroom apartment segment remains the crucial battleground for housing suitability (Figure 6). Neighborhoods in the east, such as Al-Nahda, Al-Khaleej, and King Faisal, form a “critical price range” (SAR 750,000–860,000), balancing near-ceiling costs with good services and accessibility. At the other extreme, neighborhoods like Aradeed, Uhud, and Badr offer “price abundance” (SAR 480,000–600,000), attracting budget-conscious buyers. The binary Apartment HSI (Figure 7) maps the geography of purchasing power: a value of 1 creates a contiguous “housing tank” across the south, east, and west (e.g., Al-Naseem, Al-Shifa, Badr), while the north scores a universal 0 due to prices exceeding SAR 1 million.

Figure 6.

Price of 3-bedroom apartments.

Figure 7.

Housing Suitability Index for 3-bedroom apartments.

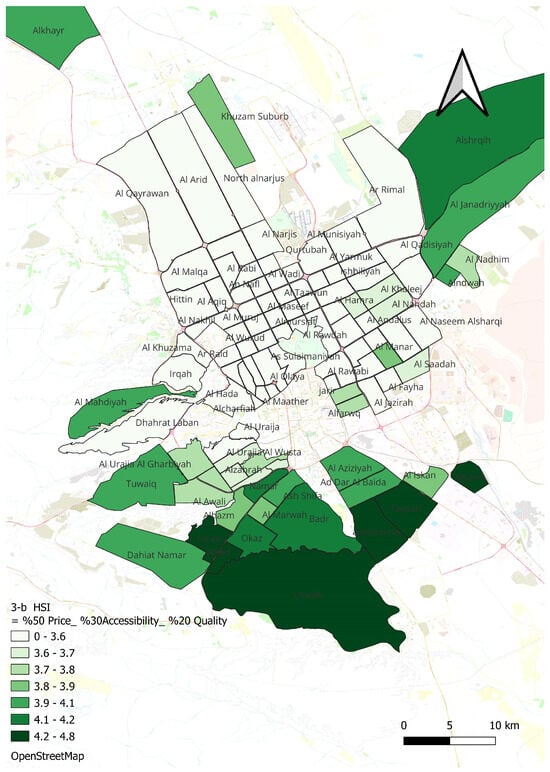

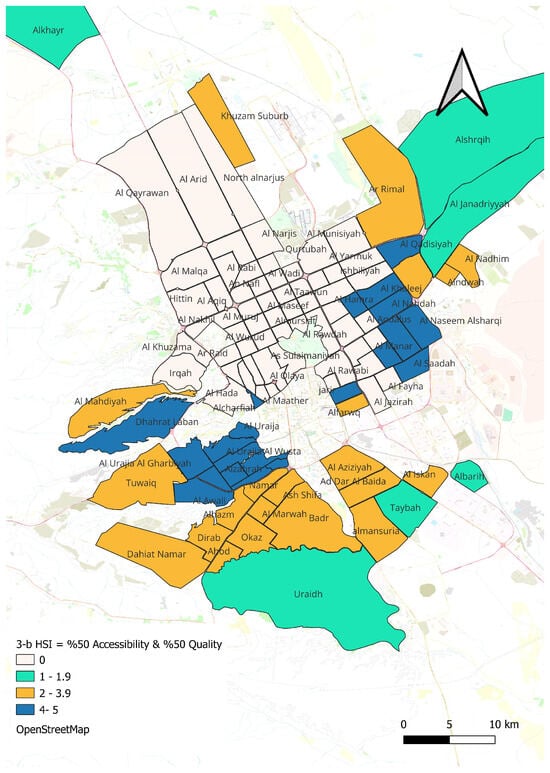

The composite HSI models, applying different weightings to the core variables, crystallize the essential trade-offs facing new families.

The Price-Sensitive Model (50% Price, 30% Accessibility, 20% Quality): This model prioritizes financial security above all (Figure 8). It catapults ultra-low-price neighborhoods, including Aradeed (4.8/5), Dirab (4.5/5), and Uhud (4.4/5), to the top. Conversely, well-located but higher-priced neighborhoods like King Faisal and Al-Nahda are downgraded to 1.2–1.8. This model serves buyers for whom minimizing debt is the absolute priority, accepting periphery and lower service levels as the cost of ownership.

Figure 8.

Three-bedroom HSI = 50% Price, 30% Accessibility, 20% Quality.

The Quality-of-Life Model (0% Price, 50% Accessibility, 50% Quality): This model assumes the price ceiling is met and asks, “Among affordable neighborhoods, which offers the best living experience?” (Figure 9). The ranking dramatically reverses, highlighting established eastern neighborhoods: King Faisal (5.0/5), Al-Salam (4.9/5), Al-Nahda (4.8/5). Meanwhile, Aradeed scores a minimum 1.0/5. This model acts as a “quality compass,” demonstrating that the low price on the periphery is a tax paid in commuting time and quality of life. It identifies the neighborhoods that deliver the greatest value for money within the affordable bracket.

Figure 9.

Service and Logistics Suitability (50-50) without price (HSI 50_50 no price).

4.2. Qualitative Behavioral Analysis: Findings from Focus Groups

The focus group discussions with developers (Group A, n = 8) and new families (Group B, n = 8) revealed deep-seated structural misalignments that explain and give meaning to the quantitative patterns, centered on three core gaps.

A fundamental “mathematical dilemma” was articulated by both groups. Developers described land cost as a primary constraint, consuming 35–45% of total project budgets before construction begins, making units under SAR 880,000 financially unviable without sacrificing margins or quality. From the family perspective, this developer calculus translates directly into significant financial pressure; monthly installments exceeding SAR 4000 can consume over 30% of their income, forcing a trade-off between long-term debt and relocation to underserved peripheral neighborhoods. This gap creates the economic underpinning for the spatial mismatch observed quantitatively.

The most acute conflict lies in the perception of value. Developers frequently employ a strategy of offering larger units on less expensive peripheral land, assuming that increased space compensates for a less central location. This strategy is fundamentally challenged by new families. Qualitative data strongly indicates a willingness to sacrifice up to 30% of unit space in exchange for proximity to work, services, and Metro stations. Participants articulated this priority with phrases such as, “We are looking for a life, not just walls,” underscoring that time and connectivity are highly valued. Families expressed a desire for integrated, functional communities over larger but isolated residential developments.

Furthermore, a profound “trust gap” distorts the market. Families expressed deep anxiety over “poor construction” and delayed delivery, leading them to restrict their search to a narrow circle of trusted, often government-affiliated, developers. This perceived reliability advantage for certain developers not only stifles competition from smaller innovators but also allows certain developers to command premium prices for perceived reliability, exacerbating affordability issues.

Despite divergent positions, both groups converged on the necessity of state-led intervention to correct the market failure. Innovative Financing: Both sides advocated for zero-interest construction loans for developers of certified affordable projects, paired with progressive, career-linked mortgages for buyers to reduce financial stress in early family formation years. State as Master Planner and Partner: Developers called for access to subsidized government land and density bonuses to improve project feasibility. Families emphasized the state’s role as the “central planner,” directly developing affordable projects in strategic, well-connected locations to ensure quality and accessibility are not sacrificed.

5. Discussion

This study’s mixed-methods analysis provides a nuanced diagnosis of Riyadh’s affordable housing conundrum, revealing it to be not merely a deficit of units but a fundamental misalignment between market supply, spatial economics, and the evolved preferences of new families. The quantitative HSI maps the symptom, a city spatially and financially segmented, which is a common sight in many major world capitals, while the qualitative focus groups diagnose the cause: a profound mismatch in perceptions of value, exacerbated by a critical trust deficit. This discussion synthesizes these findings, grounding them in established literature to argue that achieving Vision 2030’s target requires moving beyond a singular focus on supply-side production to embrace a holistic, consumer-centric approach that bridges the “three-dimensional gap” of price, location, and quality.

Before engaging with the substantive findings, it is pertinent to address two key methodological aspects of the HSI framework. First, the strict binary exclusion rule (HSI = 0 for neighborhoods exceeding the price ceiling or scoring below 3 on quality/accessibility) is intentionally designed as a policy-oriented diagnostic tool. Its purpose is not to simulate the complex, graded trade-offs of an individual buyer but to clearly and operationally identify areas of complete market failure for the target demographic. It answers a critical policy question: “Where in the city is a suitable home for a middle-income family impossible to find under current conditions?” While alternative, continuous penalty-based scoring methods could soften these thresholds, the binary approach was adopted for its clarity in mapping absolute exclusion, thus providing a stark, actionable visualization of the “Missing Middle” gap [8]. Second, the weighting structure of the HSI (50% price, 25% quality, 25% accessibility) is normative but is logically and empirically grounded. The primacy given to financing cost is supported by the qualitative findings, where the “mathematical dilemma” of mortgage burdens was the foremost concern for new families. This aligns with the residual income approach, which prioritizes securing a household’s ability to cover non-housing necessities after shelter costs [10]. The equal weighting of quality and accessibility operationalizes the holistic cost-of-place concept, acknowledging both as non-negotiable components of long-term suitability [11]. The sensitivity of this structure was tested through alternative models presented in the results (e.g., price-sensitive vs. quality-of-life models), demonstrating how rankings shift with different priorities and confirming that the core spatial trade-off remains robust across plausible weighting scenarios.

The HSI’s most striking finding is the concentration of “suitable” neighborhoods in Riyadh’s southeastern and southwestern peripheries. This aligns perfectly with the economic logic of land markets, where high prices in the northern corridor (Al-Malqa, Hittin) driven by speculation and premium infrastructure push cost-sensitive development to the urban fringe (Aradeed, Al-Khair) [6,7]. However, treating this statistical affordability as a market solution is dangerously simplistic. As Geurs and van Wee [11] and the World Bank [12] argue, true housing cost encompasses the “location tax” of land and the “transportation cost” of commuting. Our HSI models that isolate price (favoring Aradeed at 4.8/5) versus those that emphasize accessibility and quality (favoring King Faisal at 5.0/5) starkly illustrate this trade-off. A low-priced home on the periphery imposes severe hidden costs in time, fuel, and quality of life, a burden disproportionately borne by young families.

The focus groups confirm that this trade-off is central to their calculus. The participant sentiment, “We are looking for a life, not just walls”, underscores a behavioral shift from valuing square footage to valuing time and connectivity. This directly challenges the dominant developer strategy, identified in this study and corroborated by earlier research, of compensating for a less desirable location with greater unit size [4]. Our findings show families are willing to sacrifice up to 30% of unit space for proximity to work, the Riyadh Metro, and urban amenities. This evolution in preference, hinted at by Alasmari [19] as a consequence of social change, is now a defining feature of the new Saudi family’s housing psychology. This divergence explains the lower demand for peripheral, high-HSI neighborhoods and why demand remains concentrated in more central, albeit statistically “less suitable,” areas.

This misalignment is not new but is systemic. Studies comparing consumers and property practitioners across Saudi Arabia have found “significant discrepancies” where consumers rated many housing attributes as more important than professionals did [26]. Our research validates and deepens this finding, specifying that the core disconnect lies in the relative valuation of location/accessibility versus physical space. Developers, constrained by land-cost economics (35–45% of project budgets), prioritize deliverable square meters. New families, constrained by time and the total cost of living, prioritize functional urban integration. This is the essence of the “Missing Middle” crisis in Riyadh: the market fails to supply the product that reconciles these priorities a well-constructed, moderately sized home in a connected neighborhood at a fair price [8].

Beyond preferences, a critical and less quantifiable barrier emerged: a profound trust gap. Families expressed acute anxiety over “poor construction” and delivery delays, leading them to narrow their search to a handful of trusted, often government-affiliated developers. This behavioral shift results in a hegemonic ethical positioning for certain market participants, allowing them to command premiums for perceived reliability and stifling competition from smaller, potentially innovative suppliers. This finding aligns with behavioral research on Saudi housing purchases, which identifies subjective norms and recommendations from reference groups as powerful influences on decision-making [27]. In a market plagued by uncertainty, the opinion of one’s social network and the track record of a developer become paramount, overshadowing pure price considerations.

This trust gap represents a significant market failure rooted in information asymmetry. Families, as one-time buyers making the largest investment of their lives, lack the expertise to assess construction quality ex-ante. The consequences of failure are catastrophic for household finances. Therefore, the state’s enabling role, as outlined in Vision 2030 and discussed in housing policy literature [28], should extend beyond finance and land to include robust consumer protection. The lack of transparent, enforceable quality standards and warranty systems exacerbates this asymmetry, discouraging demand for new market entrants and perpetuating the dominance of a few players. The Saudi government’s strategic shift from direct provider to an enabler of markets, as articulated in Vision 2030, is the essential macro-context for this study [1]. The progress is substantial: the homeownership rate for Saudi families has reached 65.4% as of 2024, edging closer to the 70% target [29]. This achievement, largely driven by demand-side support like the Sakani program’s financing [20], validates the initial thrust of the enabling strategy.

However, our findings expose a critical paradox within this transition. The enabling approach aims to “empower the private sector to expand the housing market” for all income levels [28]. Yet, the private sector’s response, as evidenced by our focus groups with developers and the persistent “Missing Middle,” has been rational within its own constraints but misaligned with social need. Developers cite land costs and the pursuit of secure margins as reasons for favoring luxury villas or peripheral projects. This creates a situation where supply is enabled but remains fundamentally unresponsive to the core demand for integrated, affordable quality. International experiences with the enabling approach, such as in China and Egypt, warn of similar outcomes, including housing price escalation and limited access for middle-income groups [15]. Therefore, the enabling framework may require refinement to specifically facilitate the development of targeted product types in strategic location.

6. Conclusions

This study has demonstrated that Riyadh’s housing affordability challenge extends beyond simple unit shortages to encompass complex spatial, economic, and behavioral dimensions. Through the innovative application of a mixed-methods framework combining Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis across 106 neighborhoods with in-depth focus groups with developers and new families, we have developed a comprehensive Housing Suitability Index that reveals the city’s profound spatial segmentation.

The quantitative analysis identified a clear geographic pattern: while statistically “affordable” neighborhoods exist primarily in the southeastern and southwestern peripheries, these areas impose severe hidden costs through poor accessibility and compromised quality of life. The qualitative findings revealed a fundamental misalignment between supply and demand: developers prioritize delivering square meters on cheap land, while new families increasingly value time, connectivity, and construction quality over mere space. This “Missing Middle” gap is exacerbated by a critical trust deficit that distorts market competition.

To achieve Vision 2030’s 70% homeownership target, our findings recommend a hybrid policy model that transcends simple market enablement. This includes:

- Strategic State Intervention in Land Markets: Provide subsidized land parcels or land-banking mechanisms in well-connected locations to de-risk affordable development. Primary Actor: Ministry of Municipalities and Housing/Arriyadh Development Authority. Scale: Initial pilot in 2–3 strategic corridors. Horizon: Medium-term (3–5 years).

- Consumer Protection Mechanisms: Address the trust gap through transparent, enforceable quality standards and mandatory warranty systems for new affordable housing. Primary Actor: Ministry of Commerce in partnership with the Saudi Standards, Metrology and Quality Organization. Scale: National regulation. Horizon: Short- to medium-term (1–3 years).

- Innovative Financial Products: Develop progressive, career-linked mortgages that align repayment schedules with expected income growth for young professionals, alongside targeted construction financing for certified projects. Primary Actor: Saudi Central Bank (SAMA) & Real Estate Development Fund (REDF) in partnership with banks. Scale: National program with pilot testing. Horizon: Short-term pilot (1–2 years), followed by scaling.

- Integration of Suitability Indices into Planning: Institutionalize the use of suitability indices like the HSI in urban planning and zoning decisions to direct public investment and incentivize private development toward logistically connected, sustainable communities. Primary Actor: Royal Commission for Riyadh City (RCRC) and municipal planners. Scale: City-wide integration into master plans. Horizon: Medium-term (2–4 years).

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of this research. First, the weighting of the HSI, while justified by literature and qualitative insights, remains normative; alternative weightings would yield different suitability rankings, though the core spatial trade-off is robust. Second, the qualitative findings, though rich in explanatory power and reaching thematic saturation, are derived from a modest sample size (n = 16) and are not statistically representative of all developers and families in Riyadh. Third, the study employs a cross-sectional design; the HSI provides a snapshot for 2025, and a longitudinal application would be needed to track the dynamics of suitability over time. Fourth, the geographic focus on Riyadh, while critical, means the findings and the specific HSI model may not be directly transferable to other Saudi cities without contextual adaptation. Future research should address these limitations through longitudinal studies tracking preference evolution, broader surveys to test the behavioral findings, deeper institutional analysis of the trust gap, and comparative applications of the HSI framework in other urban contexts within the GCC.

By bridging the divide between spatial economics and behavioral realities, this study provides policymakers, planners, and developers with an evidence-based framework for creating housing solutions that truly meet the needs of Riyadh’s new families.

Funding

The authors would like to thank Ongoing Research Funding Program, (ORFFT-2026-063-2), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for financial support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research investigations were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Belmont Report. Given the non-clinical, anonymous nature of this social science focus group, which involved minimal risk to participants, a formal ethical review was waived.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vision 2030. Saudi Vision 2030. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/ (accessed on 20 January 2026).

- General Authority for Statistics. Population Estimates Statistics 2024; General Authority for Statistics: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2024.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Arab Human Development Report 2022: Expanding Opportunities for an Inclusive and Resilient Recovery in the Post-Pandemic Era; UNDP Regional Bureau for Arab States: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Housing. The Housing Program Delivery Plan (2021–2025); Saudi Vision 2030: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2021. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/media/u2cd14pq/2021-2025-housing-program-delivery-plan-en.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2026).

- UN-Habitat. New Urban Agenda; United Nations: Quito, Ecuador, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Future Saudi Cities Programme. Saudi Cities Report; Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2019.

- Alshuwaikhat, H.M.; Mohammed, I. Sustainability matters in national development visions—Evidence from Saudi Arabia’s vision for 2030. Sustainability 2017, 9, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallach, A. The Missing Middle: How an Overemphasis on Homeownership and Neglect of the Rental Housing Stock Contribute to the Affordable Housing Crisis; Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, M.E. What is housing affordability? The case for the residual income approach. Hous. Policy Debate 2006, 17, 151–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurs, K.T.; van Wee, B. Accessibility evaluation of land-use and transport strategies: Review and research directions. J. Transp. Geogr. 2004, 12, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Stocktaking of the Housing Sector in the Arab Republic of Egypt; Report No. 96323-EG; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- The Housing Program—Vision 2030. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/en/explore/programs/housing-program (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- ROSHN Group. Integrated Communities; ROSHN Group: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F. Planning for Growth: Urban and Regional Planning in China; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Czischke, D. Collaborative housing and housing providers: Towards an analytical framework of multi-stakeholder collaboration in housing co-production. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2018, 18, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Murie, A. The Right to Buy: Analysis and Evaluation of a Housing Policy; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Phang, S.Y. Policy innovations for affordable housing in Singapore: From colony to global city. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2018, 33, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasmari, F. Affordability, Preferences, and Barriers to Multifamily Housing for Young Families in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Buildings 2026, 16, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakani Program. Available online: https://sakani.sa (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Alhajri, M.F. Transformation of the Saudi Housing Sector through an Enabling Approach to Affordable Housing. Land 2024, 13, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriyadh Development Authority. Riyadh Public Transport Project (Riyadh Metro); Arriyadh Development Authority: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2023.

- Chakraborty, S.; Maity, I. Multi-Criteria Decision Making for Urban Development: A Systematic Review; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi, A.; Murayama, A. A critical review of seven selected neighborhood sustainability assessment tools. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2013, 38, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, F.A.; Talpur, M.A.H.; Chandio, I.A.; Kalwar, S. Factors Influencing Residential Location Choice towards Mixed Land-Use Development: An Empirical Evidence from Pakistan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghamdi, S.A. The role of subjective norms in theory of planned behavior in the context of organic food consumption. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtany, A. Affordable housing in Saudi Arabia’s vision 2030: New developments and new challenges. Int. J. Hous. Mark. Anal. 2021, 14, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs and Housing. Annual Housing Report 2024; Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs and Housing: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2024.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.