Abstract

The renovation of dilapidated housing has become a focal point of social concern. However, traditional approaches—such as repair and reinforcement or unified demolition and relocation—face bottlenecks that hinder sustainability. There is an urgent need to explore new models for addressing the risks posed by dilapidated residential buildings. In recent years, multiple regions have explored the “original demolition and original reconstruction” approach for dilapidated housing. For instance, Zhejiang Province introduced the “Resident-led Renewal” model, sparking widespread attention and discussion. This model is characterized by residents serving as the primary investors. However, the manner in which stakeholders—particularly residents—collaborate in governance and interact during the renovation process under this model remains unclear. Using the Zhegong New Village original demolition and reconstruction project as a case study, this paper employs social network analysis to construct relational networks encompassing information, trust, consultation, and support. It quantitatively reveals the characteristics of social networks among stakeholders and their interactive practices within the Resident-led Renewal model. Findings reveal that in this case, “Resident-led Renewal” primarily manifested through residents serving as principal investors and establishing a Self-Driven Renewal Committee to submit the original demolition and reconstruction application on behalf of residents to local authorities. In stakeholder interactions, the government and community neighborhood committees play a coordinating role in the renovation process. However, resident organizations and residents themselves ranked lower in metrics such as reciprocity and degree centrality, indicating their limited influence during the renovation process. To alleviate the pressure of the government’s excessive involvement and enhance resident participation in the “original demolition and original reconstruction” process, efforts should focus on: raising residents’ awareness and capacity for participation; ensuring accessible channels for resident involvement; clarifying the rights and responsibilities of all stakeholders; and establishing a standardized approval process for “original demolition and original reconstruction” projects. This approach would realize a “Resident-led Renewal” model characterized by government guidance and resident participation.

1. Introduction

China’s urbanization is transitioning from a period of rapid growth to one of stable development, with urban expansion shifting from large-scale incremental growth to a phase focused on enhancing the quality and efficiency of existing stock. Urban renewal has become a key driver for advancing high-quality urban development. The upgrading and renovation of aging residential communities constitute a vital component of urban renewal, serving a dual purpose of safeguarding people’s livelihoods and stimulating economic growth. Dilapidated and unsafe housing represents a specific category within aging residential communities. These structures are essentially existing housing stock characterized by their advanced age and significant safety hazards, such as structural damage and cracked walls. According to data from the National Bureau of Statistics (See Table 1). A total of 3,273,315 housing units constructed before 1990 have reached or are approaching 50 years of service life. Their structural safety performance now faces severe challenges, posing significant safety hazards [1]. During the decade from 1990 to 1999, 4,275,080 housing units were constructed, exceeding the total number built prior to 1990. As time progresses, more housing units will approach the end of their service life and transition into dilapidated structures. This indicates that the severity of safety hazards and the urgency of renovation for dilapidated housing far exceed those of aging residential communities. If dilapidated housing is renovated using the same approach as aging communities, it will fail to address the root causes of safety issues. The renovation of dilapidated housing urgently requires forging a new, sustainable path beyond the existing framework for aging community renovations.

Table 1.

Housing Conditions of Households by Housing Construction Year, by Region.

On 28 August 2025, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council issued the “Guiding Opinions on High-Quality Urban Development.” The document emphasizes the need to steadily advance the renovation of dilapidated and outdated housing, supporting the resident-led renewal and the practice of “original demolition and original reconstruction”. New materialism emphasizes that living spaces are not isolated objects of transformation; they coexist symbiotically with the residents themselves, serving as emotional carriers of community memory [2]. Unlike the previous top-down renewal model where the government took full responsibility, resident-led renewal demonstrates advantages in sustainable urban renewal. This approach leverages residents’ strong autonomy in both their willingness to participate in the renewal process and their capacity to contribute financially [3]. Compared to conventional relocation models, the ‘demolish and rebuild on the original site’ approach maintains the pre-renovation household count, ensuring residents can return to their original neighborhoods. This preserves the social networks established within their existing communities while effectively mitigating gentrification within inner-city areas [4]. Hangzhou has pioneered an autonomous renewal model in the Zhegong New Village project, where residents established an Organic Renewal Committee to participate throughout the renovation process, establishing the principle of “residents as the main body, government as the coordinator.” Regarding project funding, residents who actively initiated the renewal proposal served as the primary investors, thereby resolving the challenge of capital mobilization in urban renewal [5]. However, in the practice of the resident-led renewal model, how diverse stakeholders interact and to what extent resident autonomy is achieved in renewal efforts remain to be clarified. Taking the original demolition and original reconstruction project of Zhegong New Village as a case study, this paper constructs a social network of diverse stakeholders. It presents the practical implementation of the resident-led renewal model from a quantitative perspective. By analyzing the interactions of information, resources, and demands among these stakeholders during the renewal process, the abstract network relationship of “who advocates, who negotiates, who benefits” is transformed into a concrete, actionable implementation checklist. This guide enables practitioners to precisely identify pain points and bottlenecks, thereby promoting the sustainable development of the resident-led renewal model.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 reviews existing research on building retrofitting and the application of collaborative governance theory and social network analysis methods in this field. Section 3 introduces the research methods employed—social network analysis and case study methodology—and provides a detailed account of data collection and analysis approaches. Section 4 conducts a detailed analysis of the characteristics of social networks and interactive practices among various actors within four distinct social networks—information, trust, consultation, and support—in the Zhegong New Village case. Section 5 discusses and analyzes the social network characteristics of interactive practices among the actors identified in this case, proposing targeted recommendations. Section 6 summarizes the study’s design, findings, and corresponding recommendations, reflecting on limitations in the research design and suggesting directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Retrofitting Existing Buildings

Current scholarly research on the renovation of existing buildings primarily focuses on three key areas: First, health monitoring and renovation methods for existing structures. Traditional building safety assessments typically involve on-site inspections by professionals and evaluations based on codes and standards, which are cumbersome and inefficient [6]. Recent research integrates BIM technology, sensors [7], and drones [8] with modern data collection methods to establish safety evaluation and early warning systems for existing buildings. This approach enhances efficiency while enabling precise localization of building components and visual management [9]. Beyond monitoring the structural safety of existing buildings, extensive research has focused on retrofitting them through measures such as elevator installation, green renovations, and structural reinforcement to enhance safety and functionality. Second, policies and governance for existing building retrofits. Since the 1960s, the UK has advanced community renewal initiatives, gradually incorporating market mechanisms while emphasizing community empowerment and multi-stakeholder participation. This approach strengthens civic rights and promotes democratic renewal [10]. Wen and Jiang systematically traced the logical evolution of urban renewal policies since the founding of the People’s Republic of China. They advocate adopting a holistic governance perspective in this new phase of people-centered urban renewal, leveraging the decisive role of the market in resource allocation, and establishing a collaborative governance mechanism involving multiple stakeholders throughout the entire renewal cycle [11]. Third, the input-output ratio of existing building renovations. In pursuit of sustainable renewal models, scholars have examined aspects such as social capital participation [12], financial equilibrium in renewal projects [13], and external benefits of renewal [14]. Regarding the selection of renewal approaches, Liu and Zhao analyzed the intrinsic logic of interest distribution among the government, developers, and residents under two models—block-based renovation and original demolition and original reconstruction—using the transformation of Xiamen’s Hubin District as a case study [15]. Comparing the advantages and disadvantages of both models from an investment-return perspective, they concluded that original demolition and original reconstruction offer greater sustainability.

To alleviate government fiscal pressures and enhance residents’ sense of fulfillment, multiple regions have explored the “original demolition and original reconstruction” approach. Building 2 at No. 68 Majiapu Courtyard pioneered this model for dilapidated buildings, summarizing lessons learned in terms of applicability, implementation strategies, and outcomes to provide reference for renovating similar aging structures in older residential communities [16]. Maly analyzed three post-disaster reconstruction cases in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Japan and concluded that original demolition and original reconstruction development that focuses solely on spatial alterations while neglecting resident participation fails to genuinely enhance residents’ sense of gain. It should instead adopt a resident-centered approach across three dimensions: housing form, decision-making processes, and policy frameworks [17]. In Sydney, such development represents not merely an improvement in living standards, but a choice made by property owners after careful consideration of their economic capacity, social capital, and locational advantages [18]. The Zhegong New Village Renovation Project addresses new requirements for urban renewal in old-area redevelopment under evolving circumstances. It demonstrates varying degrees of innovation across six dimensions: renewal entities, funding sources, financial equilibrium, policy provision, coordinated planning, and resident interests. By analyzing its implementation process, this study explores the value of the project’s resident-led renewal model, summarizes practical insights, and offers new strategies and optimization recommendations for the “original demolition and original reconstruction” approach [5,19].

In summary, current research on existing building retrofits has encompassed policy, technology, market, and governance dimensions, with the system becoming increasingly comprehensive. However, for the relatively unique practice of original demolition and original reconstruction of dilapidated buildings in renovation projects, research still tends to rely on qualitative case descriptions of related practices. Key interactive relationships remain unclear, such as how governments guide resident participation, the extent to which residents achieve autonomy, and how multiple stakeholders collaborate. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze the interactions among stakeholders in resident-led renewal models to open the black box of these interactions.

2.2. Collaborative Governance and the Introduction of Social Networking Tools in Urban Renewal

Current research on collaborative governance theory in urban renewal has been extensive, primarily focusing on three key areas. First, collaborative actors: the traditional governance model dominated by a single entity in urban renewal has proven inadequate, necessitating a shift toward collaborative governance. This requires clarifying the roles of collaborative actors—including governments, enterprises, social organizations, and citizens—while optimizing participation mechanisms, information sharing, and incentive structures to align with collaborative governance principles [20]. Second is the coordination mechanism. As urban renewal becomes increasingly multi-stakeholder and complex, the block-based redevelopment model will become the focus of future transformation to prevent fragmentation within renewal areas. To better adapt to this shift, a land consolidation model based on collaborative governance and its implementation pathways has been proposed. Building upon this foundation, an innovative “multi-dimensional coordination + spatial governance” model has been developed to achieve synergistic efforts among government, enterprises, and the public [21]. Shanghai encourages residents to participate in micro-updating initiatives for aging neighborhoods through the “One Map, Three Meetings” system and community engagement, achieving collaborative governance [22]. Xu et al. focus on Hong Kong’s historic buildings, employing collaborative governance theory to analyze policy evolution, shifts in power dynamics among stakeholders, and collaborative models within the city’s historic building preservation and revitalization processes. They explore potential solutions through specific case studies [23]. Third is the collaborative pathway. To assess the feasibility of collaborative governance, Ansell and Gash analyzed numerous cases and proposed a general model for collaborative governance, transforming the concept into an analyzable tool [24]. Subsequent scholars refined this model based on different case studies to adapt it to various research contexts. Bettis et al. applied this tool to identify key multi-stakeholders in a public land development decision-making process. They summarized and abstracted the project’s specific practices in institutional design, collaborative processes, and catalytic leadership to facilitate multi-stakeholder coordination. This further constructed a collaborative governance model for land development [25]. Zhu and Gao applied this general collaborative governance model to analyze the collaborative governance status of old city renovation. They proposed optimization suggestions from the perspectives of institutional design, collaborative processes, and catalytic leadership, aiming to construct a collaborative governance model for old city renovation [26].

Meanwhile, some scholars have incorporated social network tools into collaborative governance research. Compared to traditional analytical paradigms, social network analysis (SNA) demonstrates significant methodological innovation. This theoretical framework not only focuses examination on dimensions such as social relationship density and organizational structural forms but also incorporates quantitative analytical techniques. By constructing an indicator system to measure social relationship characteristics, it enables clear dissection of complex social networks. This analytical perspective breaks through the limitations of individual-centered approaches in traditional research, expanding the unit of analysis from single actors to actor networks. It particularly emphasizes the interactive mechanisms between the overall network structure and individual actors [27]. The uniqueness of its methodology is specifically manifested in three dimensions: analytical perspective, expression method, and data analysis. This three-dimensional analytical framework provides a more explanatory research framework for understanding the dynamic complexity of social systems [28].

The original demolition and original reconstruction of dilapidated housing involves multiple stakeholders with complex and diverse interactions, forming a typical social system. Social network analysis can effectively analyze and resolve the issues arising from these multi-stakeholder interactions. For instance, Wu et al. employed social network analysis to examine the collaborative governance roles and participation structures of diverse stakeholders in sustainable community transformation. By analyzing multiple dimensions—including collaboration frequency, collaboration quality, trust, dependency, value consensus, and participation in the updating process—they revealed the highly complex and uneven nature of participation structures, as well as the dynamic pathways through which collaborative governance emerges [29]. Sun et al. adopted a multi-stakeholder perspective, employing a dual-mode network to identify the interests of various stakeholders at different stages of the transformation process, and provided recommendations for coordinating relationships among these stakeholders [30]. Huang et al. adopting a social network perspective, examined two urban renewal projects in Guangzhou and Beijing as case studies. They compared the differences in interaction patterns among diverse stakeholders under varying urban renewal governance models, identified issues within these models, and proposed optimization pathways. Their findings offer recommendations for selecting appropriate governance models [31]. Through a review of the literature, it has been found that social network analysis serves as a powerful tool for examining the collaborative governance interactions among multiple stakeholders in the field of urban renewal. Current research primarily focuses on collaborative governance interactions among diverse stakeholders in the renovation of old residential communities and neighborhoods, with limited exploration of the characteristics of multi-stakeholder social network structures and interactive practices within the resident-led renewal model of original demolition and original reconstruction for dilapidated housing. This paper will conduct an in-depth study on this topic.

3. Research Methods and Case Selection

3.1. Research Methods

3.1.1. Social Network Analysis

Social network analysis (SNA) theory traces its origins to the 1930s, first proposed by sociologist Thomas. Its original purpose was to construct community network models to analyze patterns of interpersonal interaction [32]. The fundamental components of a social network comprise two core elements: network nodes and network ties. Nodes, as the basic units of the network, represent social entities at the level of individuals or groups, which function as actors within the network [33]. Network relationships are formed by connecting nodes to create specific patterns of linkage. These relationships can manifest as interactive behaviors with explicit communication content or as objectively existing substantive connections [34]. It is worth noting that actors can establish direct or indirect connections through various types of relationships. The complex network structures formed by the interweaving of multiple relationships are precisely the primary focus of social network analysis.

Network density is a key metric for evaluating the closeness of node connections within a network structure. It is quantified as the ratio of the actual number of connections formed in the network to its theoretical maximum connection capacity [35]. This metric reveals the structural characteristics of a network by precisely measuring its global connectivity features, making it one of the most widely used variables in network research for describing structural properties.

Reciprocity serves as a metric for assessing the symmetry of interactions among multiple stakeholders. By analyzing the records of initiations and receptions between a specific entity and other participants, it evaluates the balance of relationships. This indicator employs a standardized measurement within the [0, 1] interval, where values closer to 1 indicate a more pronounced positive reciprocity in the entity’s relationship-building behavior. A high degree of alignment between initiated connections and received feedback indicates the actor’s tendency to establish long-term, stable cooperative networks, with both cooperation achievement rates and effectiveness operating at elevated levels. Concurrently, such actors exhibit significant structural advantages within social networks, manifested as higher social status, resource attraction capabilities, and network adaptability. When the indicator approaches 0, it indicates a significant imbalance between the connections initiated by the subject and the feedback received. This one-way relationship pattern often leads to reduced cooperation stability and weakened network influence.

Degree centrality metrics quantify direct relationships between actors to reveal the centralization characteristics of relational networks and their power distribution patterns. This analytical framework employs a dual-dimensional approach to examine network structural features, primarily encompassing two levels of analysis: the individual centrality dimension and the overall network dimension. Degree centrality, as a core metric at the individual level, reflects the scale of an actor’s direct connections within the network. Its value is quantified using a dual indicator system comprising absolute values and standardized values [0, 1]. A higher standardized value indicates that the subject possesses a broader network of direct connections and wields more significant influence within the network discourse. Centrality as a measure at the overall network level describes the concentration tendency of the relational network around specific nodes. Its value is also standardized within [0, 1]. Values approaching 0 indicate a more pronounced decentralization of power distribution, with relatively balanced influence among actors. Values closer to 1 indicate greater concentration of network power at core nodes, revealing significant power clustering within the network. Degree centrality can be quantified from both out-degree and in-degree perspectives.

Structural holes represent non-redundant connections. Burt posits that “non-redundant contacts are linked by structural holes, where a structural hole is a non-redundant connection between two actors” [36]. Structural hole analysis metrics include effective size, efficiency, constraint, and rank. Effective size quantifies an actor’s degree of non-redundant connections within the network, while efficiency reflects relational density through the ratio of effective size to individual network size. Higher values for these metrics indicate a greater likelihood that an actor occupies a structural hole position within the network, endowing their relational network with higher information intermediation value. Among the four assessment dimensions, constraint serves as the core metric, reflecting the closeness of connections among other participants within an actor’s individual network. When strong ties form among other participants, the actor’s constrainedness significantly increases. This paradoxically diminishes their strategic value as a structural hole node while weakening their ability to leverage structural hole advantages. The hierarchy metric reveals the individual dependency of resource constraints; higher values indicate weaker structural hole advantages within the network, reflecting that resource control is more constrained by other participants than by the actor’s own network position.

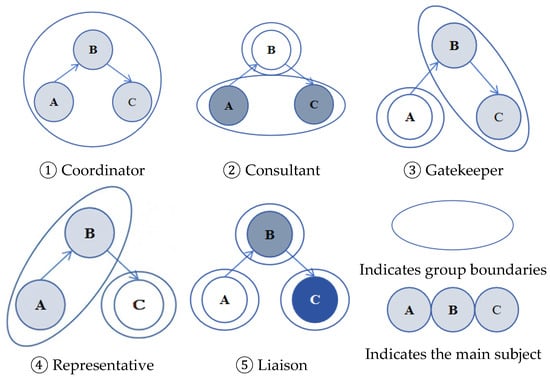

In a triadic relationship involving A, B, and C, if A is connected to B and B is connected to C, but A is not directly connected to C, then B acts as an intermediary. A requires B to connect with C. When A, B, and C belong to different groups, five types of intermediaries emerge, each defined by B’s social role:—When A, B, and C are in the same group, B acts as a coordinator.—When A and C are in the same group and B is in another group, B acts as a consultant. When B and C belong to the same group but A is in another group, B acts as a gatekeeper. When A and B belong to the same group but C is in another group, B acts as a representative. When A’s group is distinct from both B’s and C’s groups, B acts as a liaison. As shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Five Types of Middlemen.

Based on literature review, the interactive relationships in the renovation of old residential areas and dilapidated housing have been identified, as shown in Table 2. Subsequently, through semi-structured interviews, the relevance of the identified interactions to the case study was confirmed. It was ultimately decided to analyze these interactions across four dimensions: information, trust, consultation, and support. Drawing upon Wu et al.’s research into collaborative governance interactions within community renewal, the information dimension issue was broke down as communication frequency, duration of exchanges, and the closeness of relationships during the renovation process [29]. Trust refers to mutual confidence among stakeholders, drawing upon the optimized trust dimensions proposed by Luo, the trust-related issue was broken down as follows: honesty and openness, possession of renovation-related skills, reliability of renovation actions, and avoidance of taking advantage of others [37]. Drawing upon Luo and Zhu’s analysis of employee interaction behaviors in the workplace, the consultation dimension was broke down as whether stakeholders jointly discuss issues, seek advice from others when encountering difficulties or policy ambiguities [38]. We synthesized stakeholder perspectives on the support dimension gathered from the semi-structured interviews. Support dimension was broken down as seeking assistance from other stakeholders when problems arise during renovation, including policy support, financial support, and professional expertise.

Table 2.

Identification of Interactive Relationships in Old Residential Areas (Dilapidated Buildings).

By examining four relational dimensions—information, trust, consultation, and support—and analyzing network characteristics such as network density, reciprocity, degree centrality, structural holes, intermediaries, and core peripheries, this study aims to uncover the underlying communication structures within multi-stakeholder interactions. It seeks to identify communication bottlenecks, thereby facilitating the flow of information and resources.

3.1.2. Case Study

Case studies are commonly used to address research questions such as “what” and “why”; their subjects are events currently unfolding, over which researchers have little or no control [45]. Case studies are empirical research methods that focus on phenomena occurring in real-world settings. They employ a variety of qualitative and quantitative techniques to collect and analyze data, helping people gain a comprehensive understanding of complex social phenomena. This research approach possesses unique flexibility [45,46].

Case selection serves as the precursor to implementing case studies, with the selection process pursuing dual objectives: ensuring representativeness while maximizing theoretical value. Typically, seven case study types are selected: typical, diverse, extreme, anomalous, influential, most similar, and most dissimilar cases [47]. The Zhegong New Village Project represents the practice of transitioning from government-led to resident-driven multi-stakeholder collaborative governance, achieving significant breakthroughs in resident participation models and funding channels. Given its substantial influence, this project was selected as the case study for this research. This analysis examines the interactions among the diverse stakeholders involved, identifies challenges within the resident-led renewal model, explores potential solutions, and develops replicable best practices. The aim is to advance the resident-led renewal approach and provide valuable insights for future dilapidated housing renovation projects.

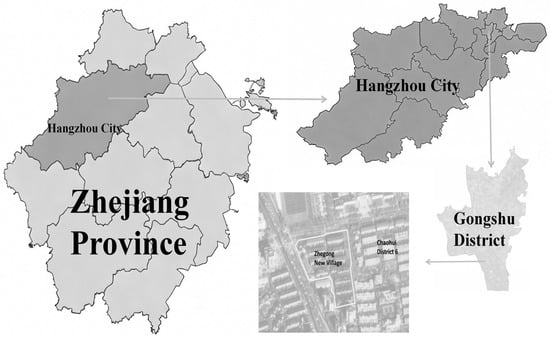

The Zhegong New Village project is located in Chaohui District 6, Gongshu District, Hangzhou. See Figure 2. The site was originally staff housing for Zhejiang University of Technology. Among the 13 existing residential buildings, 12 were constructed in the 1980s and 1990s, while one is an expert apartment building completed in 2001. Zhegong New Village faces four primary issues: First, the buildings’ functional integrity has deteriorated. The outdated floor plans of the early-built residences lack kitchens and bathrooms, failing to meet modern living standards. Second, the neighborhood suffers from poor environmental quality, manifested in narrow roads causing chaotic traffic flow, disorderly utility lines, inadequate landscaping design, and insufficient maintenance. Third, supporting facilities are deficient: motor vehicle parking ratios are severely inadequate, while community-wide aging-in-place adaptations and child-friendly facilities are lacking. Public activity spaces and fitness facilities for all residents are also insufficient. Fourth, property management fails to meet residents’ needs, with the existing maintenance system unable to support high-quality community service demands.

Figure 2.

Geographic location of Zhegong New Village.

The renovation process faced numerous setbacks. In 1993, one building in the complex was identified as structurally unsound. Although later reinforced, it was reclassified as unsafe in 2014. Subsequently, three additional buildings were designated as Grade C hazardous structures. Zhejiang University of Technology and the district government proposed multiple renovation plans, but all were shelved due to strong opposition from property owners against reinforcement and renovation. In April 2023, the Gongshu District Government formally launched the “Zhegong New Village Urban Renewal Pilot Project for Hazardous and Dilapidated Housing.” In May, property owners established a Voluntary Organic Renewal Committee and submitted a written application. The district government designated Chaohui Subdistrict Office and the District Urban Development Group as the organizing unit and implementing entity, respectively. In October of the same year, following a joint review of the preliminary design plan organized by the District Housing and Urban-Rural Development Bureau (District Old-Area Renovation Office) commissioned by the district government, the EPC bidding process was completed and the construction permit was obtained. Construction officially commenced on November 28. The renovation project covers a total floor area of approximately 81,000 square meters, involving 548 households. It entails demolishing the original 13 buildings, constructing 7 new mid-rise residential buildings, and renovating 1 existing building. The total renovation cost amounted to approximately 530 million yuan. Residents contributed about 470 million yuan, averaging roughly 1 million yuan per household. Additional funding came from government subsidies and proceeds from selling new supporting facilities and underground parking spaces, achieving near-funding balance. The project was delivered in February 2025, standing as a pioneering and relatively successful case study in China’s exploration of the “original demolish and original reconstruction” approach for dilapidated housing.

3.2. Data Collection

3.2.1. Second-Hand Data Collection

By collecting and analyzing relevant reports and literature on Zhegong New Village, we identified 15 stakeholders across four categories involved in the original demolition and reconstruction project. Following field research and semi-structured interviews, these stakeholders were verified and adjusted. The final results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Main Structures Involved in the Original Demolition and Original Reconstruction Project at Zhegong New Village.

3.2.2. Questionnaire Survey

A questionnaire on social networks during the transformation process was distributed to identified stakeholders, aiming to explore collaborative relationships among diverse entities—particularly interactions involving information sharing, trust, consultation, and support. Relationship strength was measured using a 5-point Likert scale: 1 = Strongly Disagree; 2 = Somewhat Disagree; 3 = Somewhat Agree; 4 = Strongly Agree; 5 = Strongly Agree. A total of 43 valid questionnaires were collected, covering all stakeholder categories. Where multiple individuals form a single category completed the questionnaire, to mitigate individual response variations or incomplete answers, the data for that category were weighted and averaged to generate a preliminary relationship matrix. This ensures the reliability and validity of the data [29]. Within information relationships, communication frequency was deemed the most critical factor, thus weighted at 40% in calculations, while the other two questions each received a 30% weighting. In trust relationships, all five questions are equally important indicators of trust, so each question was weighted at 20%. In consultation relationships, the ability of entities to discuss issues together better reflects multi-stakeholder interaction, so this question was weighted at 40%, with the remaining two questions each weighted at 30%. In support relationships, policy support and financial support are the most critical issues. Therefore, these two questions are weighted at 30% each, while the remaining two questions are weighted at 20% each. Through the above weighted aggregation method, the final relationship matrix is generated.

3.2.3. Semi-Structured Interview

To conduct a more in-depth examination of the social network analysis findings, including validating the results and exploring reasons for discrepancies with prior research, we conducted semi-structured interviews. Interviewees included directors of relevant provincial department divisions, heads of municipal bureaus, heads of district bureaus, heads of subdistrict and community offices, representatives of residents’ self-governance committees, and construction companies—all stakeholders influencing the renovation process. This multi-level coverage ensured the validity of interview outcomes. Through these interviews, we obtained critical information regarding collaboration among diverse stakeholders across project phases, thereby enhancing the interpretation of social network analysis findings.

4. Research Findings

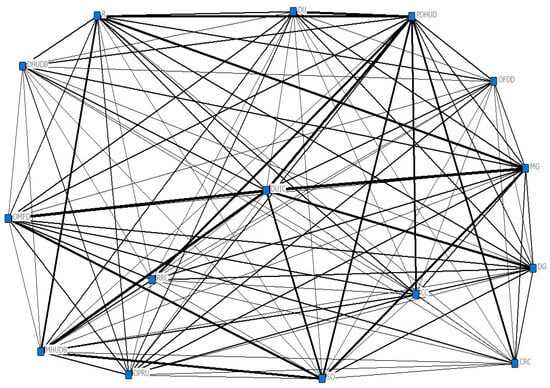

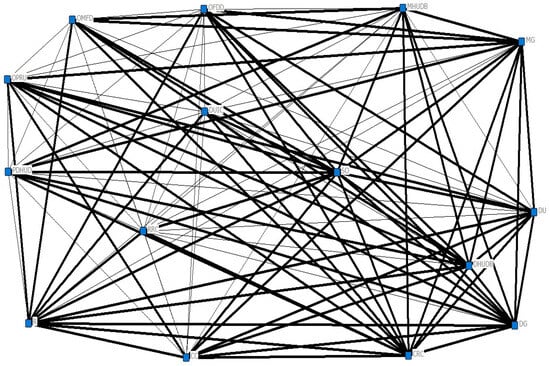

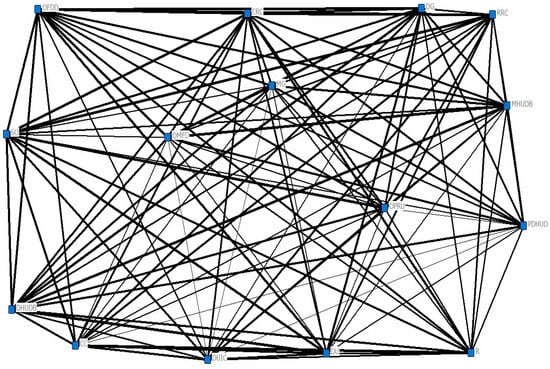

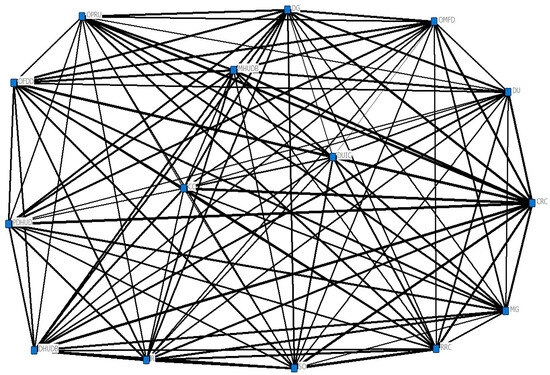

According to the analysis, the relationship network diagram for the four relational dimensions—information, trust, consultation, and support—during the original demolition and original reconstruction process of Zhegong New Village is shown in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6. In this network diagram, square nodes represent stakeholder entities participating in collaboration, while the connection status between nodes reflects the existence of collaborative relationships—a direct link between two nodes indicates that the corresponding entities engage in collaborative interactions within a specific dimension. The following sections provide a detailed analysis of network metrics including network density, reciprocity, and centrality.

Figure 4.

Trust Relationship Network.

Figure 5.

Consulting Relationship Network.

Figure 6.

Support Relationship Network.

4.1. Network Density Analysis

Comprehensive network research must first analyze the coordination level among actors involved in the original demolition and original reconstruction of dilapidated housing. Within network structures, increased connections between actors significantly enhance the cohesion of the social network. Typically, density metrics range from 0 to 1. When network density reaches high levels, it indicates greater interaction among diverse stakeholders and deeper interconnections, thereby promoting the efficient flow of knowledge, information, and resources.

Before conducting network density analysis, the four relationship matrices to be analyzed must first undergo binarization. The binarization method selected in this paper involves calculating the mean value for each row of data and assigning values of 0 or 1 based on whether the row’s values are greater than or less than the mean. The analysis results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Network Density results.

During network density analysis, the relationship matrix undergoes binarization, simplifying the strength of connections between nodes into binary states of 1 or 0. When network density reaches 0.5, the network is considered idealized. Analysis reveals that the densities of all four relationship networks cluster around 0.5, indicating they are all idealized relationship networks. The densities of the four networks, ranked from highest to lowest, are: Information (0.5238), Trust (0.4619), Consultation (0.4286), and Support (0.400). The information network’s structural density metric exceeds 0.5, surpassing 50% of the theoretical maximum value of 1. This indicates that within the information network system, dense interactive connections have formed among multiple entities. Conversely, the densities of the trust, consultation, and support relationship networks are below 0.500, suggesting that the level of interaction within these three networks is lower than that in the information network.

4.2. Reciprocity Analysis

The results of the reciprocity analysis among various entities during the original demolition and original reconstruction process in Zhegong New Village are presented in Table 5. Overall, the reciprocity levels across the four networks, ranked from highest to lowest, are as follows: trust (0.571), information (0.495), consultation (0.229), and support (0.152). The trust relationship network exhibits the highest reciprocity level, while the support relationship network demonstrates the lowest. Referencing Hu’s classification of reciprocity indicators, the reciprocity levels of the information, consultation, and support networks were found to be below 0.5. This indicates relatively low reciprocity in interactions among multiple stakeholders within these three networks during the original demolition and original reconstruction of dilapidated housing [48]. The reciprocity level in the support network exceeded 0.5, suggesting a relatively high degree of reciprocity among multiple stakeholders within this network during the renovation process. If the difference between an actor’s highest and lowest ranking is greater than or equal to 10, it indicates significant variation in reciprocity across different networks for that actor. Analysis reveals substantial reciprocity differences among the community neighborhood committee, district urban investment company, and residents. For example, the community neighborhood committee ranks eleventh in the trust and support networks but first in the information network.

Table 5.

Reciprocity Analysis Results.

As shown in the table above, in the specific practice of original demolition and original reconstruction in Zhegong New Village, the reciprocity of trust, consultation, and support networks is relatively low, while that of information networks is comparatively high. As a grassroots administrative unit, the subdistrict office holds a significant advantage in reciprocity indicators across all four relational networks, ranking first among all actors in terms of reciprocity. The district government exhibits the lowest level of reciprocity, indicating a need for further improvement. The reciprocity levels of the community neighborhood committee, district urban investment company, and residents vary considerably across different relational networks, indicating a need to strengthen reciprocity among these actors within diverse relational frameworks.

4.3. Degree Centrality Analysis

4.3.1. Excessive Centrality

Out-degree centrality, as a key metric in network centrality analysis, comprises two core indicators: point-degree centrality and graph-out-degree centrality. The out-degree metric specifically quantifies the number of relationships actively established by actors, reflecting their capacity to initiate connections within the network. Table 5 presents the relative point-degree centrality and graph-out-degree centrality for four relationship networks: information, trust, consultation, and support.

First, a quantitative assessment of the graph outdegree centrality metrics at the network level was conducted. Analysis revealed that the four networks exhibited a gradient distribution of outdegree centrality metrics, with values decreasing in the following order: Support Network (0.169), Advisory Network (0.165), Information Network (0.161), and Trust Network (0.083). Notably, the graph outdegree centrality metrics for all networks were below 0.5, indicating a low overall level of centralization. No significant node clustering was observed across any network, with relationship distributions exhibiting high equilibrium characteristics.

Second, a quantitative analysis was conducted on the in-degree centrality and rankings of each actor within the individual actor dimension. Based on the quantitative data in Table 6, the actors with higher in-degree centrality were the District Government and the District Housing and Construction Bureau. The District Government ranked first in the trust and support relationship networks and second in the consultation network; the District Housing and Construction Bureau ranked first in both the trust and consultation networks and second in the information network. Next is the Subdistrict Office, ranking first in the consultation network, second in both the information and trust networks, and fifth in the support network. Actors with low in-degree centrality are residents, who rank in the bottom five across all four relationship networks, particularly occupying the last position in the trust relationship network. The Resident Self-Renovation Committee exhibits higher out-degree centrality only within the information network. Comparing the four relationship networks reveals significant disparities in out-degree centrality rankings among certain entities, with differences exceeding 10 between highest and lowest rankings. These entities include the Provincial Housing and Urban-Rural Development Department, the Municipal Government, and the District Urban Investment Company. The networks exhibiting these substantial variations all included the information network. The Provincial Housing and Urban-Rural Development Department and the Municipal Government ranked last in the information network, yet they ranked third and second, respectively, in the out-degree centrality of the support relationship network. The District Urban Investment Company ranked third in the information network but last in the consultation network.

Table 6.

Results of the Deviation Center Analysis.

In summary, the analysis of out-degree centrality yields the following findings: First, the degree of centralization in all four relationship networks is relatively low. Second, the district government, district housing and urban-rural development bureau, and subdistrict offices initiate a higher number of relationships within the multi-stakeholder collaborative network, while residents initiate fewer relationships within this network. Third, the Provincial Housing and Urban-Rural Development Department and the Municipal Government, as primary supporters of the renovation, exhibit insufficient participation in information exchange and interaction. Although the District Urban Investment Company holds a relatively important position in information exchange, it demonstrates low levels of consultation, trust, and support toward other entities.

4.3.2. Centricity of Entry Degree

In-degree centrality, as a key metric in network centrality analysis, comprises two core indicators: in-degree centrality and graph in-degree centrality. The in-degree metric specifically quantifies the number of relationships received by an actor, reflecting their capacity to attract relationships within the network. Table 7 presents the relative point in-degree centrality and graph in-degree centrality for the four relationship networks.

Table 7.

Centrality Analysis Results.

First, a quantitative assessment of the out-degree centrality metrics at the network level was conducted. Analysis revealed that the out-degree centrality metrics across the four networks exhibited a gradient distribution, with values decreasing in the following order: Support (0.461), Consultation (0.258), Trust (0.147), and Information (0.126). Notably, the graph in-degree centrality metrics for all networks fall below 0.5, indicating a relatively low overall centralization level. Comparing the centralization characteristics across different networks reveals that the Support network exhibits the highest graph in-degree centrality metric. This suggests a pronounced tendency for the receiving end of this network to cluster around specific nodes, with a centralization degree significantly higher than the other three network types. In contrast, the relationship flows within the remaining networks do not exhibit a pronounced tendency to concentrate around specific nodes.

Second, a quantitative analysis was conducted on the in-degree centrality and rankings of each actor within the individual actor dimension. According to the quantitative data in Table 7, the actors ranking relatively high in the in-degree centrality metric were the community neighborhood committees and subdistrict offices. Community neighborhood committees ranked among the top two in-degree centrality across all four relationship networks, while subdistrict offices ranked among the top two in both trust and consultation networks but placed eleventh in the support network. The provincial housing and urban-rural development department exhibited low in-degree centrality, ranking last in all four networks. The Resident-Led Renovation Committee and residents ranked among the top five in in-degree centrality within the consultation and support networks, but placed in the bottom five in the information and trust networks. Comparing the four relationship networks reveals significant disparities in out-degree centrality rankings among certain actors, with differences exceeding 10 between highest and lowest positions. These actors include the municipal government, subdistrict offices, and residents. Among the networks exhibiting substantial variation, both subdistrict offices and residents are involved in the support network: subdistrict offices rank eleventh in the support network, while residents rank second. Conversely, residents rank twelfth in the information and trust networks, whereas subdistrict offices rank first in the trust network.

In summary, analyzing the degree centrality yields the following findings: First, the centralization levels of the four relationship networks are relatively low, yet significant differences exist in their degree centrality metrics. Second, community neighborhood committees and subdistrict offices receive more relationships within the multi-stakeholder collaborative network, confirming the pivotal role of grassroots administrative units and community self-governance bodies in dilapidated housing renovation. Third, while subdistrict offices occupy a central position in the trust network, they still require further strengthening within the support network. Residents need to enhance their standing within the information and trust networks. The municipal government must also elevate its position within the information, consultation, and support networks.

4.4. Structural Holes and Intermediary Analysis

4.4.1. Structural Hole Analysis

The results of the structural hole analysis are presented in Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11. Observing the analysis results for the four relationship networks reveals that the community neighborhood committee ranks first in effective size within the relationship network, second in the information, trust, and consultation networks, and last in the support network. It ranks fourteenth in the information, trust, and consultation networks. The subdistrict office ranked first in effective size within the trust and consultation networks, while its constraint system ranking placed last in the trust network and twelfth in the consultation network. The district housing and urban-rural development bureau ranked first in effective size within the information network but last in the constraint system ranking within that network. The Resident-Led Renewal Committee and residents ranked among the bottom five in both information and trust networks, while ranking among the top five in the restriction system indicator. They occupied mid-range positions in the consultation and support networks. The District Urban Investment Company ranked among the bottom four in all four relationship networks, with the restriction system ranking first in the support network and second in the information, trust, and consultation networks. Therefore, it can be concluded that the community neighborhood committee has a high likelihood of occupying structural holes. This indicates that the committee occupies a pivotal position connecting different groups or individuals, capable of bridging gaps between two or more groups that are not directly connected. It can leverage informational advantages and create opportunities. The resident-led renewal committee and residents have a lower likelihood of occupying structural holes, while the district urban investment company has the lowest likelihood of occupying structural holes.

Table 8.

Structural Hole Analysis of the Information Relationship Network.

Table 9.

Structural Hole Analysis of Trust Networks.

Table 10.

Structural Hole Analysis of the Consulting Relationship Network.

Table 11.

Structural Hole Analysis of Support Networks.

4.4.2. Middleman Analysis

Middleman analysis requires inputting the relationship matrix and partition vector matrix to be computed. The partition vector matrix is determined through the block model within the cohesive subgroup, with the grouping results of the block model shown in Table 12, Table 13, Table 14 and Table 15.

Table 12.

Information Network Block Model Grouping.

Table 13.

Trust Network Block Model Grouping.

Table 14.

Consulting Network Block Model Grouping.

Table 15.

Supports Network Block Model Grouping.

Using the results of the block model as the basis for grouping, an intermediary analysis was conducted on the four relationships. Since this analysis method is not applicable to multi-valued directed networks, the four relationship matrices require prior binary conversion processing. The specific procedure is as follows: First, calculate the average value for each row. Subsequently, based on the comparison of each element with the mean, assign a value of 1 to elements above the mean and a value of 0 to elements at or below the mean. This completes the binary conversion of the relationship matrix.

Based on the results of the intermediary analysis (see Table 16, Table 17, Table 18 and Table 19 for details), this study conducted a systematic examination of the four relationship networks. The findings reveal that community neighborhood committees, subdistrict offices, and district housing and urban-rural development bureaus consistently served as intermediaries with high frequency across all four relationship networks. Conversely, the provincial housing and urban-rural development department exhibited the lowest frequency of intermediary involvement in each network. This analysis indicates that community neighborhood committees, subdistrict offices, and district housing and urban-rural development bureaus function as core intermediaries within the dilapidated housing renovation network, demonstrating significant control over the network structure. Municipal governments, municipal housing authorities, other municipal functional departments (e.g., planning and natural resources, housing administration), district governments, district functional departments (e.g., planning and natural resources, housing administration), design units, construction units, original property rights units, and district urban investment companies played intermediary roles to a lesser extent within the relationship networks, with relatively limited intermediary functions. The proportion of residents’ autonomous renewal committees and residents acting as intermediaries varies across different relationship networks. They hold a larger share in support networks but a smaller share in information, trust, and consultation networks.

Table 16.

Middleman Analysis of the Information Relationship Network.

Table 17.

Intermediary Analysis of Trust Relationship Networks.

Table 18.

Mediator Analysis of the Advisory Relationship Network.

Table 19.

Middleman Analysis of Support Relationship Networks.

4.5. Core-Edge Analysis

By constructing a core-periphery analysis model and incorporating empirical data, researchers can precisely locate actors within networks or quantitatively measure their “Coreness” metric. This enables an objective, quantitative understanding [33] of the positional characteristics—whether central, semi-peripheral, or peripheral [49]—that actors occupy. The core-periphery model has found extensive application and is currently employed in analyzing various social phenomena, including collective action and elite networks. Therefore, based on Borgatti and Everett’s classification and the centrality calculations from core-periphery analysis [49], and drawing upon the methodology of Huang and Liu [50], the subjects are further categorized. First, identify the entity with the highest core degree as the core entity. Entities with a core degree below 0.200 are classified as peripheral entities, while those with a core degree above 0.200 but below the maximum value are designated as semi-peripheral entities. Based on Table 20, Table 21, Table 22 and Table 23, the core entities, semi-peripheral entities, and peripheral entities within each relationship network can be analyzed and determined.

Table 20.

Classification of Information Network Entities.

Table 21.

Classification of Entities in the Trust Network.

Table 22.

Classification of Entities in the Advisory Network.

Table 23.

Classification of Key Entities in the Support Network.

Based on the aforementioned classification principles, the diverse actors within the four networks are categorized as follows: Core actors occupy central positions within the social network, exhibiting higher density and tighter relationships, thereby playing a pivotal role in the collaborative governance process among diverse actors. Peripheral actors occupy marginal positions within the network, characterized by looser relationships and lower density. In the information network, the core actor is the subdistrict office, while the peripheral actor is the Provincial Department of Housing and Urban-Rural Development. This indicates that the subdistrict office occupies a central position in both the frequency and timing of information exchange, playing a crucial role in communication. Conversely, as a higher-level authority, the Provincial Department of Housing and Urban-Rural Development has fewer opportunities for direct communication with entities like enterprises and residents. In the trust network, the district government serves as the core actor, with no peripheral actors identified since all core actors exhibit a centrality index exceeding 0.200. In the consultation network, the district housing and urban-rural development bureau is the core entity, with the original property owner, residents, and the district urban investment company as peripheral entities. In the support network, the district government is the core entity, with residents, the original property owner, and the construction company as peripheral entities. The Resident-Led Renewal Committee functions as a semi-peripheral entity across all relationship networks. Residents themselves are peripheral entities in both the consultation and support networks, indicating their limited role in the renovation process.

5. Discussion

5.1. Network Architecture

In this new phase of urban development focused on enhancing the quality and efficiency of existing stock, government-led urban renewal decisions—which often lack understanding and recognition of diverse stakeholders—tend to trigger social issues and no longer meet the requirements of this new stage [51]. Research has demonstrated that through collaborative efforts among stakeholders such as governments, markets, and residents, public interests can be effectively realized [29]. The social network analysis results of the original demolition and original reconstruction project in Zhegong New Village indicate that all relationship networks have achieved an ideal network density. Interactions among diverse stakeholders are relatively frequent, facilitating the transmission of renovation information and resources. However, differences exist in network density across various relationship networks. The information network exhibits higher density, suggesting tighter relationships among stakeholders in conveying renovation information. Compared to the collaborative governance involving multiple stakeholders in sustainable community redevelopment [29], the network density within the Zhegong New Village renewal project is relatively low. This may be attributed to the fact that residents were required to relocate during the original demolition and original reconstruction phase, resulting in weaker connections between residents and other stakeholders and consequently lowering the overall network density. The reciprocity indicators reveal that during the transformation process, all stakeholders demonstrated strong reciprocity only within the information relationship network. In terms of information exchange during the transformation, diverse stakeholders achieved equal interaction. However, in other relationship networks, communication equality was relatively poor due to differing professional expertise among stakeholders, particularly evident in the consultation and support networks. Simultaneously, degree centrality metrics reveal that the centralization levels across all networks remained within a low range, with relationship distributions exhibiting strong equilibrium—indicating an open and inclusive renovation process. In summary, this project effectively achieved multi-stakeholder collaborative governance, with no single entity exercising complete dominance over the demolition and reconstruction process.

5.2. The Roles of Various Entities Within the Network

Under the “resident-led” autonomous renewal model, the practice of the Zhejiang Workers’ New Village project reveals that residents and the renewal committee primarily have relationships within the consultation and support network. This indicates that residents’ demands were effectively voiced during the renewal process, yet they initiated fewer relationships, suggesting an imbalance. In practice, the resident-led renewal committee did not play a prominent role in information exchange. Consequently, residents remained peripheral actors within the consultation and support network. Within the information and trust networks, both residents and the self-renewal committee initiated and received relatively few relationships. This suggests potential issues such as information opacity during the renewal process. This differs from the description by Zhou et al. where residents’ associations represented residents throughout the renovation process [19]. By establishing residents’ associations, residents expressed their renewal demands and intentions from the bottom up and, as the primary funders, bore the costs of original demolition and reconstruction, demonstrating strong autonomy. However, residents’ role in the renovation process remained limited, with the government still playing a dominant role.

Government officials and their functional departments play central roles across various relationship networks. Grassroots governments such as subdistrict offices serve as the primary driving force for implementing renovation projects, exhibiting higher degrees of betweenness centrality, in-degree centrality, and frequency of intermediary roles compared to other government functional departments. The Provincial Department of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, municipal government, Municipal Housing and Urban-Rural Development Bureau, and other functional departments did not exert direct influence within the renovation relationship network due to their administrative level. District governments and district housing and urban-rural development bureaus, positioned intermediately, served as core entities within trust, consultation, and support networks, reflecting the coordinating role of government departments in the renovation process. Within the support network, the government ranked prominently, indicating that when encountering policy or professional knowledge issues, various entities were more inclined to seek government support, with the government playing a coordinating role throughout the renovation process. This finding aligns with the results reported by Zhou et al. where policy implementation involves coordinated efforts between municipal and district governments, with district, subdistrict, and neighborhood committees overseeing on-site operations—demonstrating government-led demolition and reconstruction processes. This approach differs somewhat from the “government-guided” model currently advocated in China [19].

The community neighborhood committee occupies a central position within the relational network, evidenced by its receipt of numerous relationships that bridge gaps between groups. Design firms, district urban investment companies, and original property rights units typically handle only specific implementation and advancement phases during demolition and reconstruction. Their influence in overall decision-making remains limited, with less-than-close ties to other entities, occupying a central role only in select relationships. For instance, the original property owner ranks high in both in-degree and betweenness centrality within the information network, yet lags in out-degree centrality, indicating an imbalance between the information it receives and transmits. Construction firms exhibit high reciprocity across all relational networks, maintaining balanced sending and receiving of relationships. They are less likely to occupy structural holes or function as intermediaries, possibly because they serve as core participants only during specific phases of the redevelopment process, contributing less to the overall effort.

5.3. Recommendations for Promoting Resident-Led Renovations in the Future

Implementing renewal and renovation projects requires substantial investments of time, funds, and other resources, making government-led renewal models unsustainable. To ensure the sustainability of renewal projects, it is crucial for residents to take the initiative in launching renewal and renovation efforts and play a leading role throughout the process [52]. The Zhegong New Village project demonstrated strong resident autonomy in expressing renewal demands and contributing funds, while achieving collaborative governance during the renovation process. However, social network analysis revealed that residents played a limited role in governance throughout the renovation. To further enhance resident autonomy in the renovation process and promote the development of resident-led renewal models, this paper proposes the following recommendations.

5.3.1. Enhance Residents’ Awareness and Capacity for Governance Participation, and Ensure Channels for Resident Involvement

Under the influence of traditional urban renewal development models, residents exhibit a psychological inertia toward government-led initiatives [53] and possess limited understanding of public participation methods [54], resulting in low enthusiasm for engaging in renovations. As beneficiaries of the transformation, residents must also shoulder primary responsibility for the process. The government, as the city’s governing body, should guide residents to actively participate in renovation governance and provide policy support to facilitate their involvement.

The level of information disclosure during the renovation process has a positive impact on residents’ participation enthusiasm [55]. During the renovation process, it is necessary to establish integrated online and offline channels for resident participation. Regular meetings should be convened to ensure government transparency and facilitate the exchange of opinions, guaranteeing that all stakeholders have ample opportunities for face-to-face communication. Additionally, WeChat groups, mini-programs, and mobile apps can be utilized for online information disclosure and communication. Exploring supplementary measures such as smart guidance systems and intelligent customer service platforms can further enhance policy explanation services for residents.

5.3.2. Define the Rights and Obligations of Residents and Resident Organizations

The practice of demolishing and rebuilding dilapidated housing requires clarifying the relationship between residents, resident organizations, and the government. Legislation should stipulate the obligations of residents and resident organizations to participate in the renovation of dilapidated housing. As property owners, residents bear the responsibility to conduct regular inspections and undertake timely renovations and upgrades to their homes. In China, the renewal of dilapidated housing has long been viewed as the government’s responsibility, resulting in a misalignment of roles.

Secondly, residents still lack a legal remedy mechanism when making decisions on building renovation or reconstruction. During the Zhegong New Village renovation, the establishment of a Resident-Led Renewal Committee—a resident-organized body representing residents throughout the process—served as a positive measure demonstrating residents’ fulfillment of their renewal obligations as property owners. However, according to Articles 277 and 288 of the Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China, owners must establish an owners’ assembly and elect an owners’ committee to represent the legitimate rights and interests of all owners in making joint decisions regarding the reconstruction or rebuilding of buildings and their ancillary facilities. Currently, there is no legal basis for the form of the Resident-Led Renewal Committee. However, in residential communities, some complexes struggle to establish homeowners’ associations, or find themselves paralyzed after formation [56]. In this context, whether resident self-governance organizations, such as resident-led renewal committees, can serve as a remedial mechanism and participate in decision-making warrants further exploration and confirmation.

Meanwhile, the rate of resident approval for the demolition and reconstruction of dilapidated buildings remains inconsistent across different regions. Currently, Article 278 of the Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China stipulates that renovations or reconstructions of buildings and ancillary facilities require approval from owners holding more than three-quarters of the exclusive property area and constituting more than three-quarters of the owners participating in the vote. Since few residential complexes currently adopt the original demolition and reconstruction approach, Zhejiang Engineering New Village demands 100% consent to minimize disputes. However, excessively high consent thresholds hinder the progress of such projects. Even in communities like Zhegong New Village—where residents exhibit strong community identity, high renewal willingness, and relatively high economic status—achieving 100% consent (with only one household not signing) required government coordination. For other communities, reaching 100% consent would be even more challenging. Therefore, local practices must carefully consider resident consent standards, balancing feasibility and implementation efficiency.

5.3.3. Establish the Approval Process for Projects Involving Demolition and Reconstruction on the Original Site

Currently, approvals for urban renewal projects predominantly follow the procedures for new construction projects. There is a lack of specialized approval processes tailored to urban renewal, and no adaptive approval procedures have been established for the steps required in original-site reconstruction projects, such as property rights confirmation, land adjustments, or planning modifications.

Currently, regarding planning adjustments, local practices often advance through case-by-case deliberation, which presents certain shortcomings [3]. The renovation project for Zhegong New Village in this article also adopted a case-by-case joint approval approach, with the district government undertaking extensive coordination efforts regarding the review of planning indicators such as floor area ratio and fire safety. While this approach resolved the approval challenges faced by the project, it suffers from poor sustainability and low efficiency, requiring substantial government resources and imposing a significant burden on the administration.

There is an urgent need to establish a property rights confirmation process, as this confirmation serves as a prerequisite for project initiation, resident relocation into the renovation area, and capital investment. Due to their age, dilapidated and outdated housing units often involve complex property rights relationships, necessitating thorough investigation and verification of ownership. However, no clear property rights confirmation process currently exists. In certain areas, such as the renovation of Old Town Kashi, property rights have been established through mutual recognition among neighbors [57]. However, this approach lacks broad applicability. The absence of standardized procedures necessitates heavy reliance on relevant government departments for coordination and communication, making it difficult for residents or resident self-governance organizations to accomplish such coordination independently. Therefore, it is necessary to establish standardized review and approval procedures for the original demolition and original reconstruction of dilapidated buildings, providing a foundation for residents or resident-led organizations to participate in the application process either independently or by engaging professional agencies or enterprises as agents.

6. Conclusions

Dilapidated housing represents a pressing challenge in China’s urban development, posing significant safety hazards and requiring urgent renovation. Currently, various regions across China are actively exploring sustainable models for the original demolition and original reconstruction of such structures. The “resident-led renewal” model adopted in Zhegong New Village has gained considerable influence. However, the dynamics of interaction among diverse stakeholders within this model remain unclear, hindering the formation of replicable best practices. This paper uses Zhegong New Village as a case study, employing social network analysis to examine the interaction dynamics among diverse stakeholders within the self-driven renewal model. Findings reveal that in Zhegong New Village’s “demolish and rebuild” approach, residents emerged as the primary investors, bearing over 80% of the renovation costs—a highly significant development. A Resident-Led Renewal Committee was established during the renovation process, acting as the representative body for all property owners to submit the renovation application to the local housing and urban-rural development authorities. However, in the social network analysis, the Resident-Led Renewal Committee ranked lower in the indicator hierarchy, indicating that many stakeholders in the actual renovation process did not perceive its role as significant. Government and community entities assumed excessive roles, handling extensive coordination and communication tasks that consumed significant human and material resources. Based on these findings, this paper proposes a series of recommendations to address practical challenges and achieve government-guided, resident-participatory outcomes. These include enhancing residents’ awareness and capacity for participation, clarifying the legitimacy and responsibilities of resident organizations, and establishing approval mechanisms for urban renewal projects.

The study has yielded certain findings and conclusions, but some limitations remain, primarily including the following: First, since most existing cases of original demolition and original reconstruction projects are currently in the construction phase or have just been delivered, research on the subsequent management stage of such renovations is lacking. Future studies could further explore the post-construction management of “original demolition and original reconstruction” projects. Second, the paper employs social network analysis to examine interactions among stakeholders, primarily relying on questionnaire surveys as the main data collection method. This approach inevitably introduces subjectivity influenced by respondents during data formation. Third, the study is limited to a single case of Zhegong New Village. The applicability of its conclusions to other contexts requires further validation. Future research could expand the sample size, conducting comparative analyses of multiple similar cases where residents autonomously participate in the original demolition and original reconstruction model for dilapidated housing, thereby identifying common patterns.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.-B.Q.; Methodology, B.-B.Q.; Software, G.-T.R.; Validation, Y.-H.M. and S.-J.H.; Formal analysis, Y.-H.M. and S.-J.H.; Investigation, B.-B.Q. and S.-J.H.; Resources, B.-B.Q., Y.-N.L. and G.-T.R.; Data curation, Y.-N.L.; Writing—original draft, B.-B.Q., Y.-H.M. and S.-J.H.; Writing—review and editing, S.-J.H.; Supervision, B.-B.Q.; Project administration, B.-B.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Municipal University Basic Research Business Expenses Project—QN Youth Research Innovation Special Project—Youth Teachers’ Research Capacity Enhancement Plan (X21004).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of School of Urban Economics and Management, Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture.(BUCEA-SUEM-20250612, 12 June 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dong, G.Q.; Jiang, Y.; Zhu, N.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, C.Y.; Li, Q. Research on Policy Approach and Case Study of Old Residential Area Reconstruction in Urban Renewal. Urban Dev. Stud. 2023, 30, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, A. Conceptualizing new materialism in geographical studies of the rural realm. Land 2023, 12, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.Y.; Hu, M.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, X.Y.; Chen, T.Y.; Yu, F.Y. Resident-led Renewal Models in Historic Cities: Historical Review, Institutional Barriers, and Policy Framework. Urban Plan. Forum 2025, 1, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Chen, C.; Lu, H.; Sun, L.; Ren, X. Towards Resident-led Renewal: Practical Exploration, Common Bottlenecks and Institutional Innovation of “In-Situ Demolish-Rebuild” of Old Residential Buildings in Contemporary China. Urban Plan. Forum 2025, 70–79. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/31.1938.TU.20251120.1045.002 (accessed on 23 January 2026).

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, X.F.; Yin, Z.H. Multiple Challenges and Breakthrough Pathways for Urban Renewal Through Old-Area Redevelopment in the New Context: Practices and Insights from Hangzhou’s Pilot Projects. Eng. Econ. 2024, 34, 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.W.; Wang, W.; Gao, W.; Yang, C. Several Issues Concerning Safety and Seismic Performance Inspection and Appraisal of Existing Buildings. Build. Struct. 2007, 37, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.S.; Yuan, C.; Wang, Y.B.; Zhang, A.S.; Shi, G.L. BIM-Based Intelligent Monitoring Method for Super Tall Building with Multi-Source Information. J. Beijing Univ. Technol. 2021, 47, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, H.; Alzarrad, A.; Shakshuki, E. Payload assisted unmanned aerial vehicle structural health monitoring (UAVSHM) for active damage detection. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 210, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.Z.; Lin, W.J.; Qian, Y.X.; Han, X.J.; Hu, H.Y.; Lai, W.T. Multi-source data-driven safety evaluation and early warning management system for existing buildings. J. Saf. Environ. 2025, 25, 1247–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallon, A. Urban Regeneration in the UK; TongJi University Press: Shanghai, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, F.H.; Jiang, L. Holistic Governance and Urban Regeneration: A Policy Framework. Urban Dev. Stud. 2022, 29, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]