Abstract

Accurate building instance segmentation from UAV imagery remains a challenging task due to significant scale variations, complex backgrounds, and frequent occlusions. To tackle these issues, this paper proposes an improved lightweight YOLOv13-G-based framework for building extraction in UAV imagery. The backbone network is enhanced by incorporating cross-stage lightweight connections and dilated convolutions, which improve multi-scale feature representation and expand the receptive field with minimal computational cost. Furthermore, a coordinate attention mechanism and an adaptive feature fusion module are introduced to enhance spatial awareness and dynamically balance multi-level features. Extensive experiments on a large-scale dataset, which includes both public benchmarks and real UAV images, demonstrate that the proposed method achieves superior segmentation accuracy with a mean intersection over union of 93.12% and real-time inference speed of 38.46 frames per second while maintaining a compact Model size of 5.66 MB. Ablation studies and cross-dataset experiments further validate the effectiveness and generalization capability of the framework, highlighting its strong potential for practical UAV-based urban applications.

1. Introduction

With the acceleration of urbanization and the advancement of smart city construction, high-precision building instance segmentation has become particularly important in various fields such as urban planning, post-disaster assessment, infrastructure management, and environmental monitoring. Buildings, as the fundamental units of a city, require accurate recognition for scientific planning, disaster relief, infrastructure maintenance, and environmental impact analysis. However, in complex urban environments, automatic building segmentation faces significant challenges due to factors such as scale variation, occlusion, and complex backgrounds. Therefore, achieving high-precision building segmentation under these complex conditions remains a critical issue to be addressed.

With the rapid development of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) remote sensing, photogrammetry, and deep learning technologies [1], the automatic extraction of urban objects from high-resolution aerial imagery has become an important research topic in the fields of remote sensing and computer vision. Among various urban objects, buildings are regarded as the most fundamental yet structurally complex man-made entities, playing a crucial role in urban planning, smart city construction, disaster assessment, and infrastructure management. Compared with traditional ground-based surveying methods, UAV platforms offer notable advantages, including flexible deployment, low data acquisition cost, high spatial resolution, and rapid large-area coverage. These advantages provide abundant and reliable data sources for fine-grained building information extraction.

Despite the advantages of UAV imagery in building extraction tasks, building instance segmentation based on UAV images still faces considerable challenges due to imaging characteristics and the complexity of urban environments [2]. First, buildings in UAV imagery exhibit significant variations in scale, morphology, and structural complexity, ranging from low-rise residential houses to high-rise commercial structures. Second, the oblique viewing angles commonly adopted in UAV aerial photography introduce pronounced perspective distortions. In addition, complex urban backgrounds—such as vegetation, vehicles, roads, and shadows—often lead to severe occlusion and adhesion between adjacent buildings. Furthermore, illumination variations caused by different acquisition times and weather conditions further degrade image quality, increasing the difficulty of precise building boundary delineation. These factors jointly result in large intra-class variability and high inter-class similarity of building objects, thereby imposing higher requirements on instance segmentation methods in terms of accuracy and robustness.

Traditional building extraction approaches mainly rely on handcrafted features and rule-based methods, including threshold segmentation, edge detection, and morphological operations. Although certain results can be achieved under relatively simple scenes or stable imaging conditions, such methods are highly sensitive to parameter settings and exhibit limited generalization capability in complex urban environments. Machine learning methods [3] are primarily used for data processing and prediction, whereas deep learning approaches demonstrate superior performance in image processing tasks. With the advancement of deep learning, convolutional neural network (CNN)-based segmentation methods have significantly improved building extraction performance. Representative semantic segmentation models, such as FCN [4], U-Net [5,6,7], and the DeepLab [8] series, have demonstrated strong capability in pixel-level classification. However, these methods primarily focus on semantic region partitioning and are insufficient for effectively distinguishing adjacent or occluded individual buildings, which limits their applicability in instance-level building analysis tasks.

Instance segmentation methods, which integrate object detection with pixel-level segmentation, have achieved higher accuracy in building extraction. Among them, Mask R-CNN [9] is a representative two-stage approach with high segmentation accuracy. Nevertheless, its complex multi-stage architecture introduces substantial computational overhead, making it difficult to satisfy the real-time or near-real-time requirements of UAV-based applications. In contrast, one-stage frameworks represented by the YOLO [10,11,12,13,14] series have attracted increasing attention due to their end-to-end design and favorable balance between speed and accuracy. In recent years, models such as FastSAM [15] and YOLOv8 [16] have achieved improved inference efficiency by incorporating lightweight segmentation heads. Xu et al. [17] proposed PST-YOLO, a YOLO-based detection network designed for traffic sign detection in complex backgrounds. Liu et al. [18] developed a lightweight YOLOv8s-G network for detecting corrosion damage in steel structures under varying illumination conditions. Sohaib et al. proposed SC-YOLO, which integrates the CSPDarknet backbone with the Sophia optimizer—leveraging efficient Hessian estimation for curvature-aware updates—to enhance PPE detection performance in complex scenes.

However, when confronted with UAV building imagery characterized by pronounced multi-scale features, complex backgrounds, and high demands for boundary detail preservation, existing YOLO-based instance segmentation models still exhibit limitations in feature representation capability, building contour preservation, and robustness under occlusion conditions.

To address these issues, an improved building instance segmentation method based on a lightweight YOLOv13-G architecture is proposed in this study. Specifically, cross-stage partial connections and dilated convolutions are introduced into the backbone network to enhance multi-scale feature extraction capability while expanding the receptive field without significantly increasing computational cost. In the feature fusion network, a coordinate attention mechanism is embedded to guide the model toward building-related regions and boundary details while suppressing background interference. In addition, an adaptive feature fusion module is designed to dynamically adjust the weight allocation of features from different hierarchical levels, thereby achieving a more effective balance between fine-grained details and high-level semantic information.

Systematic experiments are conducted on a large-scale building instance segmentation dataset composed of public datasets and real UAV aerial images. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method significantly outperforms several mainstream instance segmentation models in segmentation accuracy while maintaining high inference efficiency. Moreover, favorable cross-scene generalization performance is achieved, verifying the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed approach for practical UAV-based urban applications. The main contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

(1) A lightweight and efficient building instance segmentation framework tailored for UAV imagery is proposed based on an improved YOLOv13-G network architecture.

(2) By incorporating cross-stage partial connections, a coordinate attention mechanism, and an adaptive feature fusion module, the multi-scale representation capability and boundary awareness of the model are significantly enhanced.

(3) Extensive comparative and ablation experiments are conducted to validate the effectiveness, efficiency, and generalization capability of the proposed method in complex urban environments.

2. Network Architecture

2.1. Baseline Network

To provide a strong and efficient baseline for building instance segmentation, YOLOv13 [19] is adopted as the foundational architecture in this study. As a recent open-source model within the YOLO family, YOLOv13 is characterized by a lightweight design and enhanced feature representation capability, which make it well suited for real-time applications in complex visual scenes.

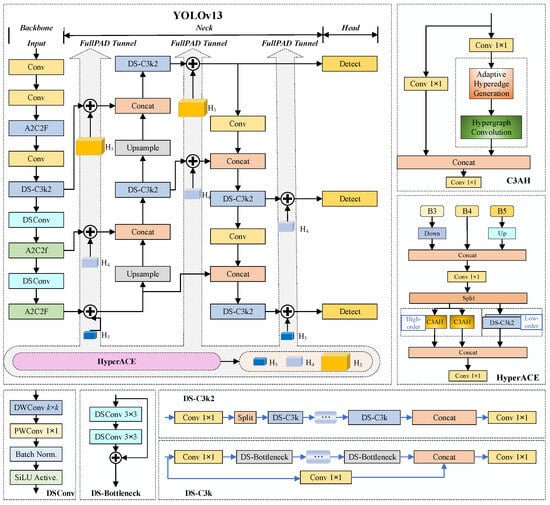

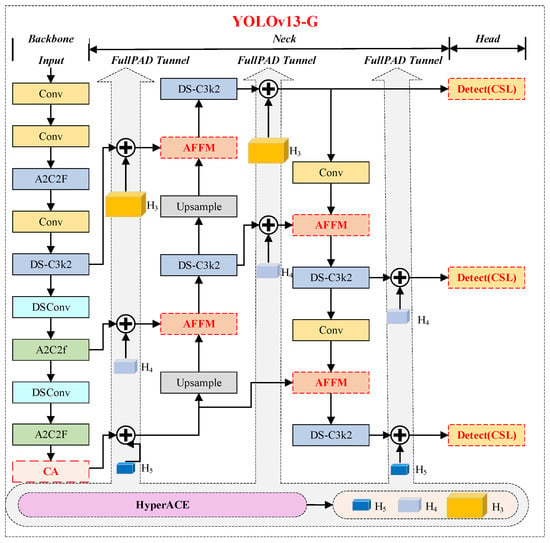

A key component of YOLOv13 is the hypergraph-based Adaptive Correlation Enhancement mechanism (HyperACE). Through hypergraph computation, HyperACE enables the modeling of high-order correlations among features, thereby extending conventional pairwise correlation modeling to more expressive cross-location and cross-scale interactions. Based on this mechanism, a Full-Path Aggregation and Distribution paradigm (FullPAD) is further employed to propagate the enhanced features throughout the network, facilitating fine-grained information flow and collaborative feature representation across different layers. In addition, depthwise separable convolutions are adopted to replace conventional large-kernel convolutions, and the module structure is optimized accordingly, resulting in a substantial reduction in model parameters and computational complexity while maintaining competitive performance. The overall network architecture of YOLOv13 is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Network architecture of YOLOv13.

Building upon this baseline, an improved building recognition and segmentation model, termed YOLOv13-G, is developed. The proposed network is trained in an end-to-end manner and consists of three main components: a backbone network, a feature fusion network (Neck), and a segmentation head (Head). The backbone network is responsible for extracting multi-scale features from the input UAV imagery, which are subsequently enhanced and fused through the Neck module. The segmentation head then simultaneously outputs building bounding boxes and pixel-level segmentation masks. The core modifications introduced in YOLOv13-G are mainly focused on the optimization of the backbone and the feature fusion network, which are described in detail in the following subsections.

2.2. Improvement of Backbone Network

To further enhance the capability of the model in capturing multi-scale building features and global contextual information, two major improvements are introduced to the backbone network.

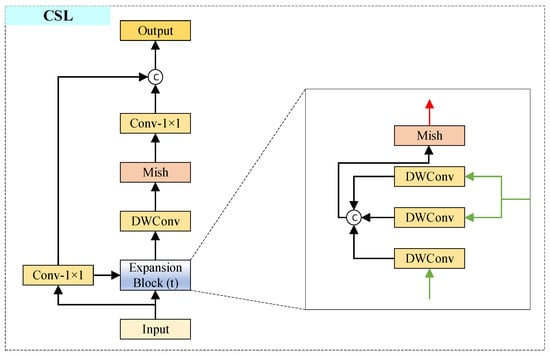

First, a Cross-Stage Lightweight (CSL) module [20] is incorporated by introducing shortcut connections between selected CSP stages. This design facilitates gradient propagation and alleviates the vanishing gradient problem commonly encountered during deep network training, thereby enabling the network to learn more expressive feature representations.

The CSL module is a lightweight convolutional design that aims to reduce computational cost by generating redundant feature maps through inexpensive operations. The core idea of this module lies in minimizing the computational burden associated with redundant feature generation while maintaining sufficient feature fitting capability.

Specifically, the input feature map is divided into two branches. In the first branch, half of the redundant feature maps are generated using low-cost operations, such as depthwise convolutions. In the second branch, the remaining essential feature maps are produced through lightweight primary operations. The outputs of the two branches are then concatenated. This design avoids the use of computationally expensive pointwise convolutions and instead relies on depthwise convolutions to generate candidate features, which significantly reduces the number of floating-point operations (FLOPs). The detailed architecture of the CSL module is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Network architecture of the CSL module.

Second, in the deeper layers of the backbone network, selected standard convolutions are replaced with dilated convolutions with a dilation rate of 2. This modification effectively enlarges the receptive field of the feature maps without increasing the number of parameters or introducing additional downsampling operations. As a result, the model is enabled to better capture the overall layout of buildings and their spatial relationships with surrounding environments.

2.3. Fusion of Attention Mechanisms

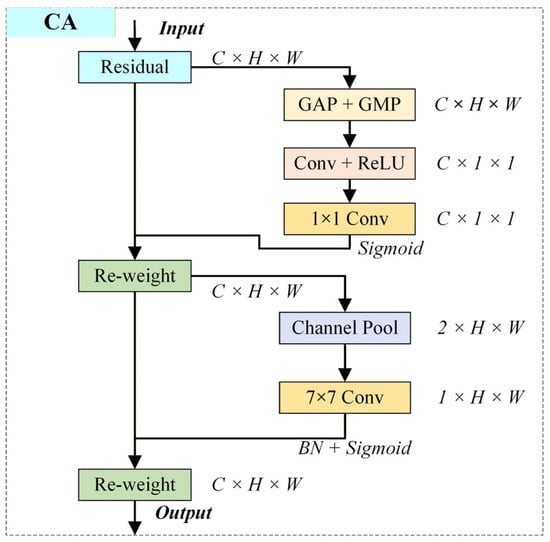

To guide the model toward focusing more effectively on building regions and boundary details while suppressing interference from complex backgrounds, a Coordinate Attention (CA) module is embedded after the key layers of the feature pyramid in the Neck component. By decomposing channel attention into directional spatial encodings along the horizontal and vertical axes, the CA module is able to preserve precise positional information while capturing inter-channel dependencies. After integration into the feature pyramid, feature responses corresponding to building-related regions are adaptively enhanced.

The Coordinate Attention (CA) module [21] is a lightweight attention mechanism specifically designed for mobile and efficient networks, aiming to improve feature representation without introducing significant computational overhead. Unlike traditional attention mechanisms, the CA module explicitly incorporates positional information into channel attention, thereby addressing the limitation of conventional methods that tend to neglect spatial structure.

The key innovation of the CA module lies in decomposing two-dimensional channel attention into two one-dimensional encoding processes along the vertical and horizontal directions. This enables the network to simultaneously capture long-range spatial dependencies and fine-grained positional information, which is particularly beneficial for tasks requiring precise localization, such as object detection and segmentation. Compared with traditional mechanisms such as SENet, the CA module avoids the loss of spatial information caused by two-dimensional global pooling and preserves directional awareness through one-dimensional pooling operations.

The CA module mainly consists of two components:

(1) Coordinate Information Embedding:

One-dimensional pooling operations, such as horizontal and vertical average pooling, are applied to the input feature map to generate direction-aware feature representations containing positional information. Specifically, pooling is performed independently along the horizontal and vertical directions, resulting in two feature maps that retain spatial coordinate information.

(2) Generation of Coordinate Attention:

The two direction-aware feature maps are concatenated and passed through convolutional layers to generate attention weights corresponding to the horizontal and vertical directions. These attention weights are subsequently applied to the input feature map, enabling direction-sensitive feature enhancement. The detailed architecture of the CA module is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Network architecture of the Coordinate Attention (CA) module.

2.4. Adaptive Feature Fusion Neck Optimization

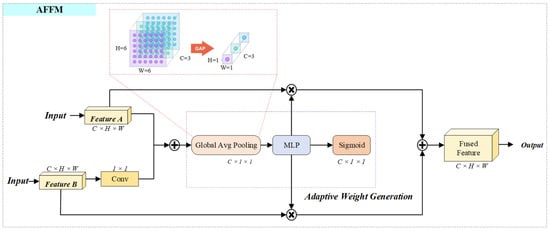

Feature pyramid networks typically fuse multi-scale features through simple addition or concatenation operations. However, such strategies fail to fully account for the varying contributions of features at different scales to the target task. To address this limitation, an Adaptive Feature Fusion Module (AFFM) [22] is introduced into the detection head architecture.

The AFFM is designed to dynamically integrate multi-source or cross-scale features, with the objective of improving the model’s representational capacity and generalization performance in complex scenarios. Its core principle is to learn adaptive weighting and fusion strategies through a data-driven mechanism, rather than relying on fixed fusion rules, thereby enabling better adaptation to diverse input conditions and task requirements.

The module receives feature maps from different hierarchical levels and employs a lightweight network—comprising global average pooling and fully connected layers—to generate adaptive channel-wise weights. These weights are then used to perform weighted fusion of the input features. Through this mechanism, the network is able to dynamically adjust the balance between shallow-layer detail features and deep-layer semantic features, leading to improved segmentation performance for small objects and fine local structures. The detailed architecture of the AFFM is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Network architecture of the Adaptive Feature Fusion Module (AFFM).

In this study, AFFM is integrated into the neck structure of the YOLO model. This integration enables more intelligent multi-scale feature fusion across the detection network, significantly enhancing the model’s robustness in detecting building damages with varied appearances and large scale differences, particularly improving the recall rate for small and indistinct damage instances.

Through the above architectural optimizations, a unified and efficient building instance segmentation framework is constructed based on the YOLOv13 baseline. By enhancing the backbone network with Cross-Stage Lightweight connections and dilated convolutions, the proposed model is enabled to capture richer multi-scale representations and broader contextual information while maintaining computational efficiency. In the feature fusion stage, the integration of the Coordinate Attention mechanism strengthens the model’s ability to emphasize building-related regions and boundary details, whereas the Adaptive Feature Fusion Module further improves the effectiveness of multi-scale feature aggregation by dynamically balancing shallow spatial details and deep semantic information. These improvements collectively enhance the robustness and accuracy of building recognition and segmentation in complex UAV imagery. The overall architecture of the improved YOLOv13-G network is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Architecture of the improved YOLOv13-G network.

3. Experimental Design and Analysis

3.1. Data Sets and Experimental Environment

To comprehensively evaluate model performance, a multi-source dataset was constructed. One subset was derived from the publicly available Buildings Instance Segmentation dataset, which contains 16,429 images and was released as part of the Buildings Instance Segmentation Computer Vision Project. This subset encompasses diverse building types captured from various altitudes and perspectives. The second subset comprised approximately 8600 images, captured by a DJI Matrice 300 RTK unmanned aerial vehicle (manufactured by SZ DJI Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) during aerial surveys across multiple urban areas in Shandong Province, China. Representative examples are shown in Figure 6. All images were manually annotated with polygonal labels using the LabelMe5.6.1 tool, and the resulting annotations were converted into YOLO format. The complete dataset was randomly divided into training, validation, and test sets, with respective ratios of 70%, 20%, and 10%. During training, several data augmentation strategies were applied—including random rotation, scaling, color jittering, and Mosaic augmentation—to enhance model generalization and robustness.

Figure 6.

Buildings dataset.

Regarding dataset acquisition, the average ground sampling distance (GSD) of the images is 0.03 m, with a flight altitude of 120 m, ensuring high-precision instance segmentation. Most of the images in the dataset are captured from a nadir view, with approximately 10% taken from an oblique view. The image overlap rate is 80%, ensuring continuity of information between images.

All experiments were performed on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU using the PyTorch 1.12.1 framework. The model was initialized with weights pre-trained on ImageNet and trained for 300 epochs using the Adam optimizer. The initial learning rate was set to 0.01, with a batch size of 20 and an input image size of 640 × 640 pixels.

3.2. Evaluation Indicators

Several widely used metrics were adopted to quantitatively evaluate model performance from the perspectives of accuracy, efficiency, and deployment cost. Mean Average Precision at an IoU threshold of 0.5 (mAP50) was selected as the primary accuracy metric to evaluate detection and instance segmentation performance [10].

Precision and recall were defined based on the numbers of true positives (), false positives (), and false negatives (), as shown in Equations (1) and (2):

At an Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.5, the Average Precision (AP50) was computed as the area under the corresponding precision-recall curve, as shown in Equation (3):

The mean Average Precision at IoU = 0.5 (mAP50) was then obtained by averaging AP50 values across all object classes, as shown in Equation (4):

where denotes the set of object classes.

Additionally, we also calculated the mean Average Precision at multiple IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95 (mAP50-95) to evaluate the model’s performance under stricter segmentation criteria. This metric is computed by averaging the AP values at different IoU thresholds (e.g., 0.5, 0.55,…, 0.95), as shown in Equation (5):

where represents the number of IoU thresholds (typically 10 in this case).

Inference efficiency was evaluated using Frames Per Second (FPS), which describes the number of images processed per second during inference. FPS was calculated as shown in Equation (6):

where denotes the total number of processed images, and represents the total inference time in seconds.

In addition, Model size was reported to assess computational complexity and deployment feasibility. Model size was defined as the total storage requirement of all trainable parameters and was computed as shown in Equation (7):

where denotes the number of network layers, represents the number of parameters in the -th layer, and indicates the storage size per parameter.

Mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) is calculated as the average IoU across all object classes. The calculation formula is shown in Equation (8).

where denotes the set of object classes, represents the predicted region for class , and represents the ground truth region for class .

4. Analysis and Discussion of the Results

4.1. Training Results

The backbone network of the proposed model is initialized with ImageNet-pretrained weights to accelerate convergence and enhance feature representation capability on the target defect dataset. During training, model checkpoints are saved every 50 epochs to track long-term training progress, and detailed logs are recorded to continuously monitor the training status. The Adam optimizer (β1 = 0.937, β2 = 0.999) is employed to minimize the overall loss function, in conjunction with dynamic loss scaling to stabilize gradient updates. The initial learning rate is set to 0.01, and a weight decay factor of 0.0005 is applied to mitigate overfitting. In addition, a dynamic learning rate scheduling strategy is adopted, whereby the learning rate is adaptively adjusted according to the training epochs and fixed after 300 epochs to facilitate fine-grained optimization in the later training stage.

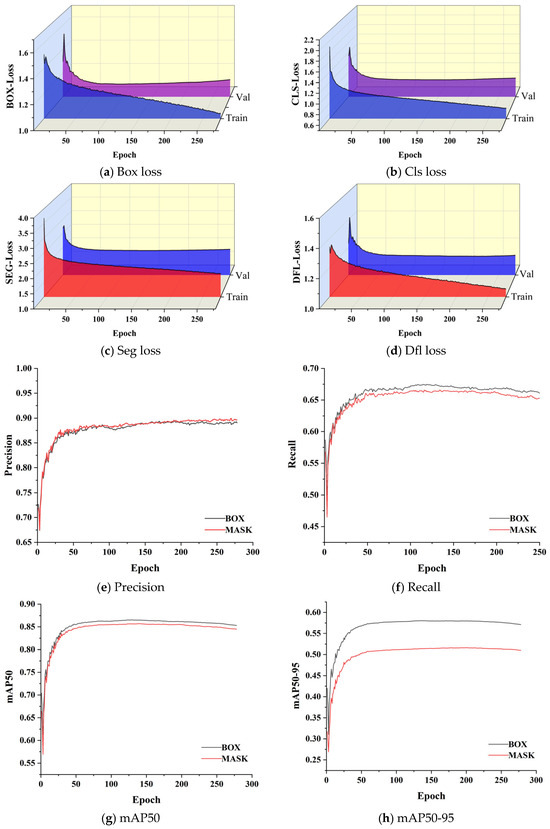

Figure 7a–h illustrate the evolution of key metrics during the training and validation processes, including various loss components (bounding Box loss, Cls loss, Seg loss, and Dfl loss), precision, recall, and mean Average Precision (mAP). In the figures, “BOX” and “MASK” denote bounding boxes and segmentation masks, respectively. As the number of epochs increases, all loss curves consistently decrease and gradually converge, while performance metrics exhibit stable upward trends, indicating effective learning and progressive error minimization. Notably, the model demonstrates rapid convergence in the early training phase, achieving approximately 90% of its peak performance within the first 20 epochs, which confirms the effectiveness of the pretrained initialization. Subsequently, the loss curves reach a plateau around 100 epochs.

Figure 7.

Training results.

Throughout the training process, the gap between training and validation losses remains small, with a final difference of approximately 0.1, suggesting strong generalization capability and the absence of overfitting. Quantitative evaluation further reveals that the model achieves high accuracy in both detection and segmentation tasks. Specifically, the peak mAP@0.5 reaches 0.865, approaching 0.9, while the more stringent mAP@0.5:0.95 metric exceeds 0.58, demonstrating robust performance under stricter evaluation criteria. Moreover, the model exhibits a high-precision characteristic, with a precision of 0.89 and a recall of 0.67, indicating reliable defect identification with a low false-positive rate.

Overall, the training process is stable and efficient. The proposed model achieves a favorable balance between precision and recall across different IoU thresholds and delivers superior segmentation performance for defect targets, validating its effectiveness and robustness.

4.2. Comparative Experiment

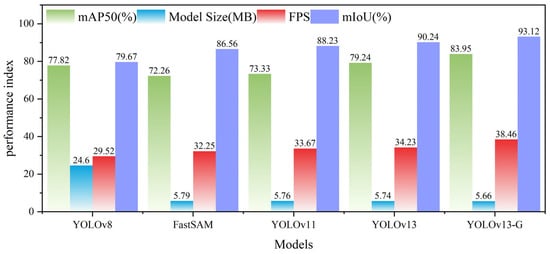

To further evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed model, a comparison was conducted with FastSAM [16], YOLOv8 [12], YOLOv11 [23], and the original YOLOv13 using the same building test dataset. All models were trained under identical strategies and experimental settings to ensure a fair comparison. The quantitative results are summarized in Table A1, while a visual comparison of mAP50, Model size, FPS, and mIoU across different networks is illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Performance comparison of different networks.

The results consistently show that the proposed YOLOv13-G model outperforms the comparison methods across all major evaluation metrics, including mAP50, mIoU, and FPS. Specifically, YOLOv13-G achieves an mAP50 of 83.95% and an mIoU of 93.12%, representing an improvement of 4.71 percentage points in mAP50 and 2.88 percentage points in mIoU over the original YOLOv13. Compared with the baseline model, the mIoU improvement reaches 4.3 percentage points, clearly demonstrating the effectiveness of the architectural enhancements introduced in YOLOv13-G.

When compared to YOLOv11, the proposed model shows substantial gains in both detection and segmentation accuracy while maintaining a similar model size and significantly higher inference speed. These improvements reflect the integration of key modules such as the CSL module, the CA mechanism, and the AFFM, which contribute to enhanced feature extraction, boundary localization, and multi-scale information fusion. The relatively lower performance of YOLOv11 can be attributed to its lack of advanced modules like CSL, CA, and AFFM, which limits its ability to perform efficient multi-scale feature extraction and boundary localization, crucial for accurate segmentation in complex scenes.

In comparison to FastSAM, while FastSAM achieves a relatively high mIoU of 86.56%, it falls short in inference speed (32.25 FPS) and model size (5.79 MB) compared to YOLOv13-G. The added complexity in FastSAM’s architecture, though beneficial for accuracy, leads to higher computational costs, making it less efficient for real-time applications. YOLOv13-G, with its improvements, strikes a better balance between accuracy, inference speed (38.46 FPS), and a compact model size (5.66 MB). The relatively lower performance of FastSAM is primarily due to its complex multi-scale feature fusion and segmentation strategies, which, although improving accuracy, increase computational demands, limiting its applicability in real-time scenarios.

YOLOv8, although demonstrating strong performance with an mAP50 of 77.82% and a reasonable inference speed (29.52 FPS), still lags behind YOLOv13-G in both segmentation accuracy (mIoU of 79.67%) and overall computational efficiency. YOLOv13-G outperforms YOLOv8 by a significant margin in both accuracy and FPS, with its enhanced modules providing better feature extraction and boundary localization, which are crucial for urban building segmentation. The relatively lower performance of YOLOv8 can be attributed to its focus primarily on detection tasks, with less emphasis on fine-grained segmentation, limiting its ability to accurately delineate complex structures like buildings in urban environments.

Notably, despite the introduction of additional modules, YOLOv13-G maintains a compact model size of only 5.66 MB, which is even slightly smaller than that of the original YOLOv13 (5.74 MB). This compactness ensures that YOLOv13-G remains efficient and suitable for deployment in environments with limited computational resources. Moreover, YOLOv13-G achieves an impressive inference speed of 38.46 FPS, outperforming other models such as YOLOv11 (33.67 FPS) and YOLOv13 (34.23 FPS). This indicates that the proposed improvements not only enhance accuracy but also significantly improve computational efficiency, fulfilling the real-time processing requirements essential for UAV platforms.

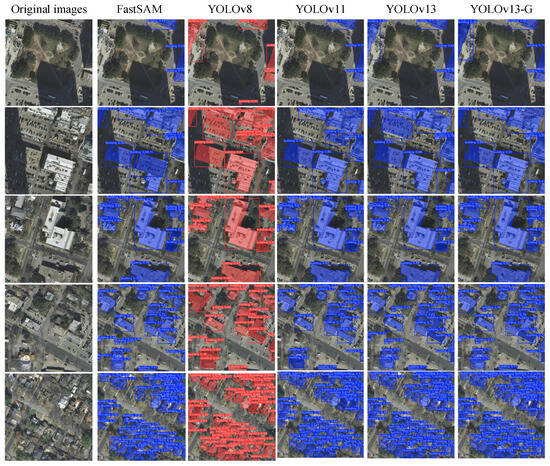

Qualitative comparisons of the prediction results produced by different networks are presented in Figure 9. As shown, YOLOv13-G generates more complete building contours, exhibits clearer boundary delineation, and effectively suppresses false positives and missed detections. This demonstrates its superior segmentation capability in complex urban scenes, where accurate boundary definition and minimal detection errors are crucial.

Figure 9.

Visualization of prediction results produced by different networks.

In summary, YOLOv13-G not only demonstrates significant improvements in segmentation accuracy (mIoU) and detection precision (mAP50) but also outperforms other models in terms of inference speed and model size. Its efficient design, enhanced feature extraction, and boundary localization capabilities make it highly suitable for real-time UAV-based building segmentation, even in resource-constrained environments.

To validate the model’s robustness under different lighting conditions, additional experiments were conducted to analyze performance under strong shadow and weak illumination conditions. In the presence of strong shadows, the model effectively segmented building targets, achieving a mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) of 90%. Under weak illumination conditions, the model still performed well in complex backgrounds, with an mIoU of 85%. These experiments further validate the robustness of the model in different environmental settings, providing additional evidence of its adaptability in complex conditions.

4.3. Ablation Experiment

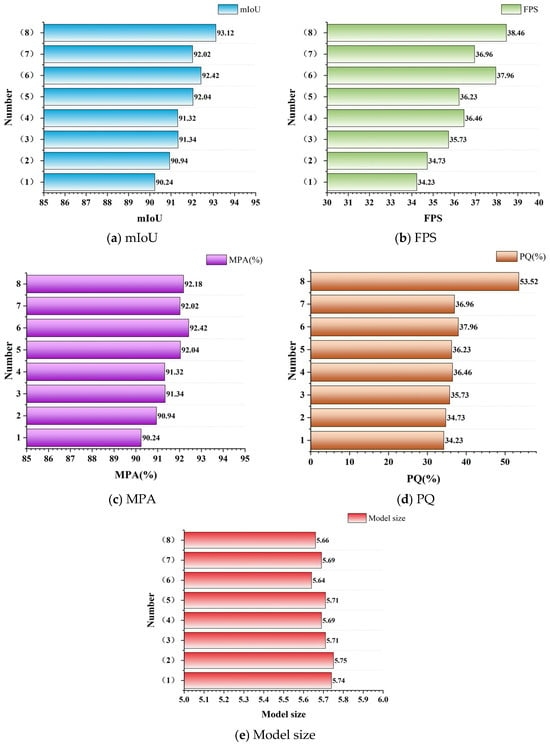

To evaluate the individual contributions of each proposed module in the YOLOv13-G network, a systematic ablation study was conducted. The modules investigated include the Cross-Stage Lightweight (CSL) module, the Coordinate Attention (CA) mechanism, and the Adaptive Feature Fusion Module (AFFM). Eight configurations were designed by selectively enabling or disabling these components, as summarized in Table A2 and illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Ablation study results.

The performance of each configuration was quantitatively assessed in terms of mIoU, FPS, Mean Pixel Accuracy (MPA), Panoptic Quality (PQ), and Model size. Number 1, serving as the baseline without any additional modules, provides a reference point for comparison. Numbers 2–4 each incorporate a single module to examine its isolated effect on segmentation accuracy and efficiency. Numbers 5–7 combine two modules to investigate potential synergistic effects, while Number 8 integrates all three modules, representing the complete YOLOv13-G architecture.

The results indicate that each module contributes positively to the overall performance. Incorporation of the CSL module improves multi-scale feature extraction, enhancing mIoU without significant impact on FPS or Model size. Additionally, the CSL module results in a modest improvement in Pixel Accuracy (MPA), increasing from 34.23% to 34.73%, thus highlighting its positive effect on pixel-level accuracy. Similarly, Panoptic Quality (PQ) shows a slight improvement, rising from 34.23% to 34.73%, confirming CSL’s role in enhancing segmentation quality. The CA mechanism strengthens boundary localization and emphasizes building-related regions, resulting in further gains in segmentation accuracy, MPA, and PQ. The AFFM facilitates adaptive integration of multi-scale features, improving both accuracy and generalization capability. When all three modules are combined, the model achieves the highest mIoU, demonstrating that the improvements are complementary and collectively enhance the effectiveness of the network. Furthermore, the integration of all three modules leads to the highest PQ of 53.52%, signifying substantial gains in overall segmentation quality.

In addition to mIoU and FPS, MPA and PQ metrics were employed to provide a deeper understanding of segmentation precision and overall quality. These metrics consistently improved across configurations, reinforcing the positive contributions of each module to both fine-grained pixel classification and instance segmentation quality.

Based on the ablation study results, the following conclusions can be drawn:

The experimental results confirm that all the proposed modules make positive contributions to the overall network performance. As the modules are progressively integrated, the model exhibits stable improvements in both segmentation accuracy (mIoU), pixel accuracy (MPA), and instance segmentation quality (PQ), while FPS increases and Model size either remains stable or decreases. The complete YOLOv13-G architecture (Number 8) achieves the best performance, reaching the highest mIoU of 93.12%, FPS of 38.46, and a Model size of 5.66 MB, slightly smaller than the baseline. This highlights the comprehensive advantages of the proposed modules in terms of accuracy, efficiency, and lightweight design. Furthermore, the complete architecture achieves the highest MPA (38.46%) and PQ (53.52%), demonstrating well-rounded improvements in both pixel-level accuracy and overall segmentation quality.

CSL module: When introduced alone (Number 2), the CSL module improves the mIoU by 0.70% (from 90.24% to 90.94%), with a slight increase in FPS and an almost unchanged Model size. This indicates that CSL effectively enhances multi-scale feature extraction without imposing a noticeable computational burden. Moreover, it contributes to a modest increase in both MPA (from 34.23% to 34.73%) and PQ (from 34.23% to 34.73%), underscoring its role in improving pixel-level accuracy and segmentation quality.

CA module: The standalone integration of the CA module (Number 3) results in a substantial mIoU improvement of 1.10%, accompanied by a notable FPS gain of approximately 1.5 and a slight reduction in Model size. These results suggest that the CA mechanism plays a critical role in strengthening boundary localization and focusing on building regions while also offering computational optimization benefits. The CA module also substantially improves both MPA (from 34.23% to 35.73%) and PQ (from 34.23% to 35.73%), confirming its importance in precise localization and region attention.

AFFM: When added independently (Number 4), AFFM yields a comparable mIoU improvement (+1.08%) and delivers the largest FPS increase (+2.23), along with a further reduction in Model size. This demonstrates that adaptive multi-scale feature fusion not only enhances segmentation accuracy but also significantly improves inference efficiency. The impact of AFFM on MPA and PQ is also notable, as it contributes to both improved pixel-level accuracy and instance segmentation quality, with MPA improving to 36.46% and PQ to 36.46%.

CSL + CA (Number 5): The combination achieves an mIoU of 92.04%, outperforming either module used alone, which confirms the complementary nature of CSL-based multi-scale feature extraction and CA-guided attention. The performance boost in both MPA (36.23%) and PQ (36.23%) further solidifies the synergy between CSL and CA.

CA + AFFM (Number 6): This configuration shows particularly strong performance in both accuracy (92.42% mIoU) and speed (37.96 FPS) while achieving the smallest Model size (5.64 MB). The results indicate that combining CA’s precise localization capability with AFFM’s adaptive fusion effectively balances performance and lightweight design. The highest PQ value of 37.96% and significant improvement in MPA (35.73%) demonstrate the power of combining these two modules.

CSL + AFFM (Number 7): This configuration also delivers notable improvements in both segmentation accuracy (92.02% mIoU) and inference speed, further validating the effectiveness of their interaction. It also shows steady improvements in both MPA (36.96%) and PQ (36.96%), highlighting the utility of combining CSL’s feature extraction with AFFM’s adaptive fusion.

All three modules combined (Number 8): The integration of CSL, CA, and AFFM yields the best overall performance, achieving 93.12% mIoU and 38.46 FPS, with a Model size of 5.66 MB, slightly smaller than the baseline. Additionally, this configuration achieves the highest PQ (53.52%) and MPA (38.46%), confirming that the three modules are highly complementary and jointly construct a more robust and efficient feature representation and fusion framework.

Overall, the ablation study verifies the effectiveness of each individual module as well as the necessity of their synergistic integration. Specifically, CSL strengthens fundamental feature extraction, CA enhances spatial awareness and localization capability, and AFFM optimizes the adaptive fusion of multi-scale information. Through their combined effect, YOLOv13-G achieves significant improvements in both accuracy and speed while maintaining low model complexity, providing an efficient and reliable solution for building segmentation tasks.

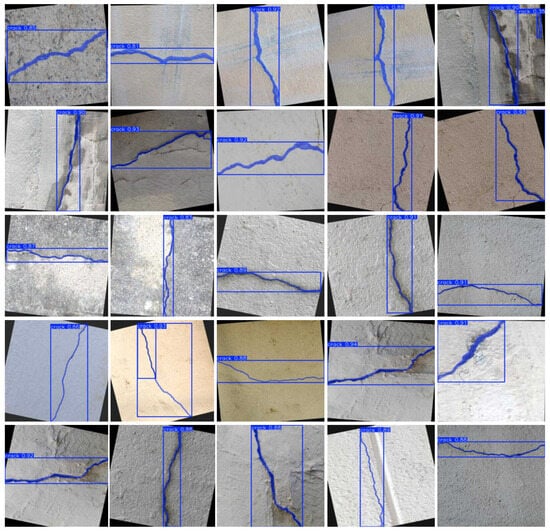

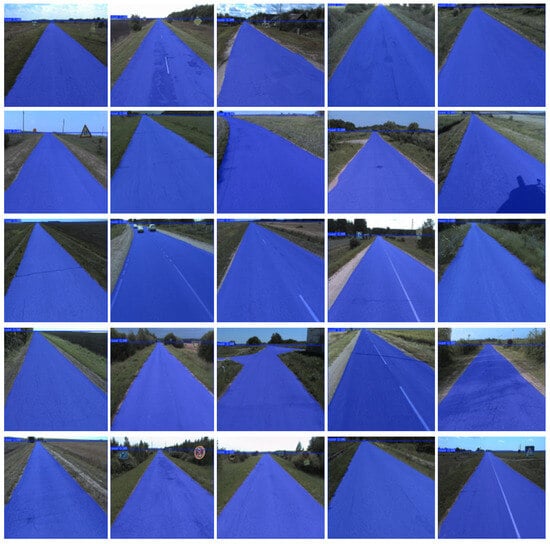

4.4. Dataset Experiment

To further evaluate the generalization capability and cross-scene adaptability of the proposed improved model, zero-shot inference experiments were conducted on two publicly available datasets to assess its performance in previously unseen scenarios. The selected datasets are Crack and Road, both obtained from the open-source dataset platform Roboflow Universe (source: https://universe.roboflow.com/). The concrete crack dataset contains over 4000 images of concrete cracks with varying sizes and shapes. It has been expanded through data augmentation techniques and includes different crack patterns such as lateral and vertical cracks, as well as cracks captured under diverse backgrounds. The road dataset consists of over 2700 images featuring various types of roads, including those under different lighting conditions and with assorted shapes.

These experiments did not involve fine-tuning the model for the Crack and Road datasets; instead, the model trained on building instance segmentation was used for inference. Despite being trained for buildings, the model effectively segmented structurally similar targets in crack and road detection tasks. This demonstrates the model’s ability to learn structural features rather than semantic generalization to specific categories.

Buildings, cracks, and roads share structural similarities, facilitating cross-task transfer learning. All exhibit elongated or linear structures: buildings have defined boundaries, cracks extend in specific directions, and roads feature linear characteristics. In large-scale scenarios, the linear features of cracks and roads resemble building contours, allowing the model to learn universal linear features for effective segmentation. Despite differences in backgrounds—buildings in complex urban settings versus simpler road and crack environments—the model successfully transfers learned structural information, achieving strong performance on crack and road datasets.

In the experimental setup, the improved YOLOv13-G network was first trained on the source task and then directly applied to the two public datasets for inference, without any additional fine-tuning or parameter updates on the target datasets. This design ensures that the results accurately reflect the model’s cross-dataset generalization capability. The qualitative segmentation results on the Crack and Road datasets are shown in Figure 11 and Figure 12, respectively. The specific performance metrics of the model are shown in Table 1.

Figure 11.

Segmentation results on the Crack dataset.

Figure 12.

Segmentation results on the Road dataset.

Table 1.

Performance metrics on public datasets.

As observed, YOLOv13-G achieves satisfactory segmentation performance on both datasets. On the Crack dataset, the model accurately identifies and clearly delineates the boundaries of cracks of various types, demonstrating strong sensitivity to thin structures and complex texture patterns. On the Road dataset, the model consistently extracts complete road contours under diverse and cluttered background conditions, exhibiting both robustness and boundary consistency.

These results indicate that the feature representations learned by the proposed model are not limited to a specific building segmentation task but possess a notable degree of generality and structural awareness. This can be attributed to the collaborative design of multi-scale feature extraction, enhanced spatial perception, and adaptive feature fusion in the improved network, which enables effective capture of structurally similar target regions. Consequently, YOLOv13-G shows strong potential for transfer to related segmentation tasks, such as crack detection and road extraction, further demonstrating its scalability and generalization advantages for practical engineering applications.

5. Conclusions

This paper introduces YOLOv13-G, an enhanced building instance segmentation model designed for UAV imagery. The model incorporates key innovations, including cross-stage lightweight connections, dilated convolutions, coordinate attention, and an adaptive feature fusion module, to effectively tackle challenges like multi-scale feature extraction, complex urban backgrounds, and occlusions. Extensive experiments on a large-scale dataset, which includes both public benchmarks and real UAV images, show that YOLOv13-G achieves an mIoU of 93.12%, an inference speed of 38.46 FPS, and a compact Model size of 5.66 MB, surpassing other mainstream segmentation models in terms of both accuracy and efficiency. Ablation studies validate that each proposed module significantly contributes to the model’s performance, with the full YOLOv13-G framework providing the best overall results. Additionally, cross-dataset experiments demonstrate the model’s strong generalization capability, making it suitable for various urban applications.

Despite the high accuracy achieved on the UAV-based building dataset, the model’s performance may decrease under extreme imaging conditions, such as motion blur, significant changes in illumination, or highly oblique angles, since it was primarily trained on building-centric images. The model processes images independently and does not utilize temporal information from UAV video sequences, which could lead to inconsistencies between frames in dynamic environments. Although the model is lightweight, deploying it on ultra-low-power embedded UAV platforms may still present challenges related to memory bandwidth and energy consumption. Additionally, the current work focuses on geometric segmentation and does not include higher-level semantic or structural attributes of buildings, which limits its applicability to more advanced urban analysis tasks.

Future work will explore further compression and acceleration techniques to enable deployment on resource-constrained UAV devices, such as through neural architecture search, quantization, or hardware-aware optimization. The model will also be extended to handle video-based segmentation by leveraging temporal consistency between frames, which could improve segmentation stability and performance in dynamic UAV applications. Additionally, incorporating multi-modal data, such as LiDAR or thermal imagery, into the segmentation process will be explored to enhance robustness in complex urban environments. Finally, the model could be adapted for downstream tasks, such as automatic damage detection (e.g., cracks, leaks, settlement) and structural health monitoring, offering a comprehensive solution for smart cities and infrastructure management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Q. and L.T.; methodology, C.L.; software, Y.L.; validation, J.M.; funding acquisition, S.L. and J.M.; investigation, P.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Sergei Leonovich of China-Belarus Joint Laboratory of Coastal Low-Carbon Concrete Technology, grant number 2025KF-1, and “The National Key Research and Development Program of China-International Cooperation in Science and Technology Innovation between Governments (Grant No. 2025YFE0113600)” and “State Key Laboratory of Disaster Reduction in Civil Engineering (Grant No. SLDRCE24-01)” was funded by Jijun Miao.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be provided as needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support from China–Belarus Joint Laboratory of Coastal Low-Carbon Concrete Technology, the National Key Research and Development Program of China-International Cooperation in Science and Technology Innovation between Governments, and the State Key Laboratory of Disaster Reduction in Civil Engineering.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yao Qu was employed by the company China Urban Construction Design & Research Institute Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CSL | Cross-Stage Lightweight |

| CA | Coordinate Attention |

| AFFM | Adaptive Feature Fusion Module |

| mIoU | mean Intersection over Union |

| FPS | Frames Per Second |

| mAP50 | The mean Average Precision at IoU = 0.5 |

| mAP50-95 | The mean Average Precision at multiple IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95 |

| MPA | Mean Pixel Accuracy |

| PQ | Panoptic Quality |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

| FastSAM | Fast Segment Anything Model |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Performance comparison of different models on building test sets.

Table A1.

Performance comparison of different models on building test sets.

| Models | mAP50 (%) | Model Size (MB) | FPS | mIoU (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv8 | 77.82 | 24.6 | 29.52 | 79.67 |

| FastSAM | 72.26 | 5.79 | 32.25 | 86.56 |

| YOLOv11 | 73.33 | 5.76 | 33.67 | 88.23 |

| YOLOv13 | 79.24 | 5.74 | 34.23 | 90.24 |

| YOLOv13-G | 83.95 | 5.66 | 38.46 | 93.12 |

Table A2.

Ablation study results.

Table A2.

Ablation study results.

| Number | CSL | CA | AFFM | MPA (%) | PQ (%) | mIoU (%) | FPS | Model Size (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 90.24 | 34.23 | 90.24 | 34.23 | 5.74 | |||

| 2 | √ | 90.94 | 34.73 | 90.94 | 34.73 | 5.75 | ||

| 3 | √ | 91.34 | 35.73 | 91.34 | 35.73 | 5.71 | ||

| 4 | √ | 91.32 | 36.46 | 91.32 | 36.46 | 5.69 | ||

| 5 | √ | √ | 92.04 | 36.23 | 92.04 | 36.23 | 5.71 | |

| 6 | √ | √ | 92.42 | 37.96 | 92.42 | 37.96 | 5.64 | |

| 7 | √ | √ | 92.02 | 36.96 | 92.02 | 36.96 | 5.69 | |

| 8 | √ | √ | √ | 92.18 | 53.52 | 93.12 | 38.46 | 5.66 |

Note: A “√” indicates that the module is selected.

References

- Luo, W.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Fu, D.; Mi, Z.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.; Shi, Y.; Su, B. Real-Time Identification and Spatial Distribution Mapping of Weeds through Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Remote Sensing. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 169, 127699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhao, X. AeroReformer: Aerial Referring Transformer for UAV-Based Referring Image Segmentation. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 143, 104817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.B.; Gao, X.Y.; Ba, P.F.; Zheng, C.Y.; Liu, C.W. Damage Identification of Corroded Reinforced Concrete Beams Based on SSA-ELM. Buildings 2025, 15, 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Deng, Z.; Ye, J.; He, J.; Yang, D. FCN+: Global Receptive Convolution Makes FCN Great Again. Neurocomputing 2025, 631, 129655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Qi, Z.; Yi, C. H2MaT-Unet:Hierarchical Hybrid Multi-Axis Transformer Based Unet for Medical Image Segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 174, 108387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.L.; Dasmahapatra, S.; Mahmoodi, S. ADS_UNet: A Nested UNet for Histopathology Image Segmentation. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 226, 120128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jing, S.H.; Dai, H.F.; Shi, A.Y. High-Resolution Remote Sensing Images Semantic Segmentation Using Improved UNet and SegNet. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2023, 108, 108734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, X.P. Medical Image Recognition and Segmentation of Pathological Slices of Gastric Cancer Based on Deeplab V3+neural Network. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 207, 106210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.X.; Fu, B.Y.; Fan, J.B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.K.; Xia, C.L. Sweet Potato Leaf Detection in a Natural Scene Based on Faster R-CNN with a Visual Attention Mechanism and DIoU-NMS. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 73, 101931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhammash, E.H. A Comparative Analysis of YOLOv9, YOLOv10, YOLOv11 for Smoke and Fire Detection. Fire 2025, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y. Fruit Detection and Positioning Technology for a Camellia oleifera C. Abel Orchard Based on Improved YOLOv4-Tiny Model and Binocular Stereo Vision. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 211, 118573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Liu, J.; Ren, Y.; Lin, C.; Liu, J.; Abbas, Z.; Islam, M.S.; Xiao, G. YOLOv8-QR: An Improved YOLOv8 Model via Attention Mechanism for Object Detection of QR Code Defects. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 118, 109376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Liu, P.; He, B.; Li, W.; Song, T. Automated Detection and Segmentation of Tunnel Defects and Objects Using YOLOv8-CM. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 150, 105857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, E.; Ramos, L.; Romero, C.; Rivas-Echeverría, F. A Comparative Study of YOLOv5 and YOLOv8 for Corrosion Segmentation Tasks in Metal Surfaces. Array 2024, 22, 100351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Tian, L.; Wang, P.; Yu, Q.-Q.; Zhong, X.; Miao, J. Knowledge-Driven 3D Damage Mapping and Decision Support for Fire-Damaged Reinforced Concrete Structures Using Enhanced Deep Learning and Multi-Modal Sensing. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 68, 103715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemamalini, P.; Chandraprakash, M.K.; Hunashikatti, L.; Rathinakumari, C.; Senthil Kumaran, G.; Suneetha, K. Thermal Canopy Segmentation in Tomato Plants: A Novel Approach with Integration of YOLOv8-C and FastSAM. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 10, 100806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xiao, X. PST-YOLO: A Lightweight, Robust Approach for Traffic Sign Detection via Polynomial-Based and Progressive Scale Fusions. Digit. Signal Process 2026, 169, 105745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Tian, L.; Wang, P.; Yu, Q.-Q.; Song, L.; Miao, J. Non-Destructive Detection and Quantification of Corrosion Damage in Coated Steel Components with Different Illumination Conditions. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 282, 127854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Li, S.; Wu, Y.; Hu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, X.; Ding, G.; Du, S.; Wu, Z.; Gao, Y. YOLOv13: Real-Time Object Detection with Hypergraph-Enhanced Adaptive Visual Perception. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.17733. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.-M.; Lee, C.-C.; Hsieh, J.-W.; Fan, K.-C. CSL-YOLO: A Cross-Stage Lightweight Object Detector with Low FLOPs. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Austin, TX, USA, 27 May–1 June 2022; pp. 2730–2734. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Q.; Zhou, D.; Feng, J. Coordinate Attention for Efficient Mobile Network Design. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20 June–25 June 2021; pp. 13713–13722. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Li, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, K. Adaptive Feature Fusion Network for Infrared Small Target Detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), Niagara Falls, ON, Canada, 15–19 July 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, H.Q.; Xiao, C.L.; Zhao, K. Detection Method of Key Ship Parts Based on YOLOv11. Processes 2025, 13, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.