Abstract

Optimizing photovoltaic (PV) installations requires precise understanding of the annual energy yield, which depends heavily on geographical location, panel technology, tilt, and azimuth. This study establishes the framework for a “European Photovoltaic Atlas”. In this pilot phase, the dynamic tool is applied to representative European climatic zones to compare diverse latitudes and technologies. Consequently, we aim to create a robust database and interactive visualization tool that allows users to analyze technology-specific yields based on variable orientation parameters. The study employs a large-scale simulation campaign using EnergyPlus coupled with a PVWatts model. Two photovoltaic technologies (PERC and TOPCon monocrystalline) have been simulated in seven European reference cities: Naples, Madrid, Berlin, Paris, London, Stockholm, and Warsaw. For each city and technology, simulations have been performed for a complete grid of orientations. The tilt was varied from 0° to 90° in 5° increments, and the azimuth was varied from 0° to 360° in 5° increments. All panels have been simulated at a height of 15 m to represent typical rooftop installations. The main result is a comprehensive database that links location, technology, tilt, azimuth, and normalized annual energy yield. This database feeds an interactive application developed in Python. This tool generates 2D heatmaps showing the surface orientation factor of any selected city–technology pair, 3D surface plots comparing performance across multiple technologies or locations simultaneously, and 2D charts estimating hourly annual productivity by varying technology efficiency values. The “Photovoltaic Atlas” serves as a practical decision support tool for architects and engineers by enabling the rapid optimization of photovoltaic systems and clearly illustrating performance in the European context.

1. Introduction

The transition toward sustainable and efficient built environments is becoming urgent due to growing global energy demands and the need to mitigate the impacts of climate change [1]. Across Europe, the building sector accounts for 40% of final energy consumption, yet it is estimated that less than 25% of Europe’s building stock possesses sufficient energy performance [2]. Furthermore, electricity accounted for approximately 35% of building energy use in 2022, an increase from 30% in 2010 [3]. To transform this energy-intensive sector into an autonomous and efficient one, the implementation of renewable energy solutions is essential, with the integration of photovoltaic (PV) systems playing a key role in increasing renewable energy capacity within the built environment [4]. Comprehensive life cycle impact assessments across the continent have confirmed that residential rooftop PV systems are a highly sustainable solution, with most installations breaking even in terms of cost and energy within 5 to 11 years [5]. Solar potential is typically assessed through a hierarchical approach, progressing from physical potential to geographic potential (available area) and culminating in technical potential (actual energy yield). Quantifying this potential through a solar map is the first step in accelerating the use of solar energy in urban environments [6], serving as a support platform for city administrations to base their energy decisions upon. The development of solar cadastres is particularly vital for the assessment and planning of near-zero energy districts (NZEB) [7]. Recognizing that estimating PV potential is a complex, multi-dimensional process, a need emerges for more accurate and scalable yield estimation tools to guide policies and maximize PV adoption [4]. Extensive research has been conducted to determine optimal tilt angles and solar ratios globally [8] and to review methods for maximizing incident solar radiation [9]. However, the effective deployment of PV in urban environments is often constrained by complex morphological factors. Unlike utility-scale solar farms where orientation can be perfectly optimized, rooftop installations must adapt to existing building geometries. Densely built urban areas introduce intricate inter-building shading interactions that significantly reduce incident irradiance; recent deep learning frameworks capable of predicting spatiotemporal shading have quantified that these effects can cause an average annual energy loss of 5.32% across rooftops [10]. Furthermore, high-fidelity mapping efforts now utilize ensemble deep learning and multi-criteria GIS to adjust for local atmospheric conditions, such as cloud cover and transmissivity [11]. Orientation analysis must also consider the unique topography of specific cities, where shadows from nearby terrain or distant mountains can notably decrease annual available insolation [12]. While the recent literature has made significant strides in predicting complex urban shading, this Atlas adopts a complementary approach, intentionally neglecting near-shading effects to isolate the impact of geometric and technological variables. This allows for the provision of an ideal performance baseline, which is essential for identifying the optimal positioning window before considering local morphological constraints.

Consequently, designers face a critical challenge: they need to determine not only the theoretical maximum yield but also the performance penalties associated with sub-optimal installations. Previous research has largely focused on the rigorous quantification of available geographic potential. For instance, Izquierdo et al. [13] developed a scalable methodology applied in Spain, utilizing geographic information systems (GIS) and stratified sampling to estimate available roof surface area based on representative building typologies. Similarly, Bergamasco and Asinari [14] proposed a hierarchical methodology for assessing rooftop PV potential in the Piedmont region (Italy), leveraging GIS data and solar radiation maps. Other studies have employed advanced modelling for technical potential and energy yield analysis. To achieve higher precision, Jakubiec and Reinhart [15] developed a method to predict city-wide PV electricity gains by combining LiDAR and GIS data with hourly simulations, physically modelling reflections from the urban context. The validation of such models is crucial. Walch et al. [16] quantified hourly PV generation in Switzerland using machine learning, noting a 16% average overestimation in modelled annual yield compared to measured data, highlighting the uncertainties in standard models. Furthermore, the challenges of high-density environments were addressed by Ni et al. [17], who proposed an enhanced framework using deep learning and GIS to evaluate rooftop PV potential in Shanghai. They explicitly included inter-building shading and rooftop obstacles, concluding that omitting these factors can lead to a capacity overestimation of up to 25.6%. Shirinyan and Petrova-Antonova [18] also explored the application of specialized 3D CAD tools for large-scale analysis, demonstrating the necessity of accurate geometric pre-processing to handle computational complexities. Despite these advancements, a limitation remains regarding intuitive visualization and comprehensive geometric optimization, particularly when considering the dynamic impact of different PV technologies, as noted by Freitas et al. [19] in their review of urban solar modelling. While authoritative tools like PVGIS [20] provide accurate point-based estimations, they typically require iterative manual inputs to assess different geometric configurations one by one.

The novelty of the “European Photovoltaic Atlas” lies in its ability to visualize the entire solution space simultaneously. By generating a complete grid of 1368 orientations per city, the Atlas allows for the immediate identification of the optimal positioning window and the quantification of yield losses for sub-optimal positions without the need for multiple independent simulations. To address this gap, this study introduces the “European Photovoltaic Atlas,” a dynamic simulation framework and interactive tool designed to map technology-specific yields across Europe. The primary objective is to provide a decision-support system that visualizes the sensitivity of energy production to geometric orientation. Through the generation of detailed performance heatmaps, the Atlas allows technicians to instantly identify valid installation surfaces, shifting the focus from simple yield calculation to comprehensive geometric optimization. Underpinning this visual tool is a rigorous physics-based simulation engine based on EnergyPlus [21] coupled with the PVWatts model [22]. Unlike simplified static approaches, this methodology ensures that the resulting maps account for the dynamic interplay between solar irradiance, cell technology, and operating temperature. The study specifically analyzes the performance divergence between modern TOPCon monocrystalline and PERC monocrystalline technologies, quantifying how different cell types respond to the varying environmental conditions of seven European climatic zones. The reliability of this framework has been verified through a benchmark against authoritative datasets based on satellite data (PVGIS-SARAH3) and one real-data application in Poland. By bridging the gap between complex dynamic simulations and engineering practice, the European Photovoltaic Atlas provides a ready-to-use decision-support system. It streamlines the design workflow, ensuring that the expansion of urban PV capacity is driven by accurate, technology-specific data that is immediately accessible and actionable for designers.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 details the simulation workflow, the thermophysical modelling of the panels, and the validation strategy; Section 3 presents the validation results and illustrates the capabilities of the Atlas tool through specific case studies; finally, Section 4 discusses the implications for European energy planning and concludes the study.

2. Methods

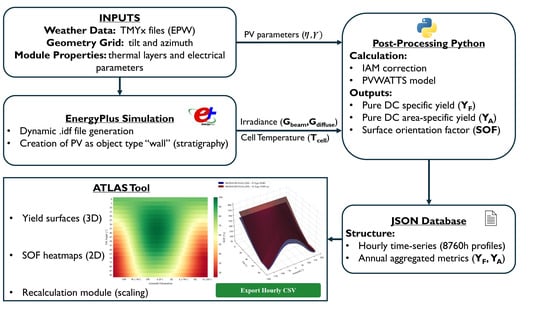

The methodological framework adopted in this study is structured around three sequential phases: (1) the execution of a large-scale parametric simulation campaign to generate a high-resolution database of hourly and annual performance; (2) the systematic collection, aggregation, and structuring of the simulation results; (3) the development of the “European Photovoltaic Atlas,” an interactive decision-support application designed for data visualization, comparative analysis, and yield recalculation. This comprehensive workflow is visually summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Methodological workflow of the European Photovoltaic Atlas.

2.1. Model Formulation

Our solar mapping approach differs from conventional static methods based on a GIS or aggregated statistics. By employing a dynamic simulation engine, this study enables technology-specific analysis, complementing established calculation models such as PVGIS [20] with a comprehensive geometric mapping of energy potential.

2.1.1. Thermal and Optical Modelling

The core of the simulation framework is the EnergyPlus (v. 9.4.0) engine [21], selected for its capability to solve the complex thermophysical behaviour of components using the conduction transfer function (CTF) algorithm. To obtain a realistic estimate of the hourly operating temperature of the module (), the photovoltaic panel was modelled in EnergyPlus as a free-standing opaque surface using the “BuildingSurface:Detailed” object (Type: Wall) [23]. Unlike simplified models that treat panels as dimensionless shading objects, this approach simulates the thermal inertia and heat transfer through the specific material stratigraphy. The module structure was defined as a composite construction consisting of five layers: front glass, front encapsulant (EVA), the active silicon layer, a second layer of EVA, and the backsheet [24,25,26]. The thermophysical properties adopted for the simulation are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Thermophysical properties of the photovoltaic module layers [25,26].

Accurate definition of boundary conditions is crucial for thermal and optical balance. The simulation employed the “FullInteriorAndExteriorWithReflections” algorithm to explicitly calculate beam and diffuse solar radiation reflected from the ground (albedo, which was set as a constant to 0.2 and 0.4 in case of snow). Furthermore, the “DetailedSkyDiffuseModeling” option was selected to account for the anisotropic radiance distribution of the sky dome, distinguishing between circumsolar brightening and horizon brightening rather than assuming a uniform isotropic sky [23]. The conversion to electrical energy depends on the effective irradiance reaching the cells after optical losses. A post-processing step was implemented in the Python control script to calculate the incidence angle modifier (IAM). The effective irradiance is derived as follows:

where is the beam component and is the total diffuse component (sky + ground). The beam modifier () was calculated using the ASHRAE transmission model for standard glass [27,28]:

where is the incidence angle and is the incidence angle modifier coefficient, set to 0.05, which is typical for flat glass. For diffuse radiation, a constant factor () of 0.95 was applied, consistent with ASHRAE standards for isotropic approximations. EnergyPlus provide and for each configuration. It must be noted that the ASHRAE model [27] is a simplification. Unlike more complex physical models (e.g Sandia), it assumes a generic behaviour for the glass–air interface and may overestimate transmission at high incidence angles (>70°) where reflectivity increases non-linearly. Additionally, applying a fixed scalar to diffuse radiation simplifies the complex angular distribution of diffuse light, potentially introducing minor inaccuracies under overcast conditions. Regarding thermal exchanges with the air, a hybrid convection strategy was implemented using the “SurfaceProperty:ConvectionCoefficients” object. The front (exterior) surface convection was calculated using the DOE-2 algorithm [23], which dynamically adjusts the heat transfer coefficient based on wind speed. A different approach was required for the rear (interior) surface because EnergyPlus models the PV panel as a Wall object; consequently, the rear face interacts with an internal thermal zone rather than the exterior environment, rendering standard outdoor algorithms like DOE-2 inapplicable. To accurately simulate an open-rack installation where the back is exposed to outdoor air, the adjacent thermal zone was modelled to maintain an air temperature approximately equal to the outdoor ambient temperature (setting a high infiltration rate). The rear convective heat transfer coefficient () was therefore imposed via a custom dynamic schedule derived from the hourly wind speed () extracted directly from the EPW weather file. This coefficient was calculated using linear Equation (3) and injected into the simulation as a schedule file.

This is a standard correlation originally derived by McAdams [29] and is widely adopted in the solar engineering literature [28]. While this empirical formulation is a linearization that simplifies complex boundary layer physics—potentially underestimating convective exchanges at near-zero wind speeds where natural convection dominates—it provides a robust and computationally efficient estimate for the rear face of free-standing modules where wind-driven forced convection is the governing heat-loss mechanism.

The simulation assumes an open-field or unshaded rooftop configuration, neglecting near-shading effects to isolate the geometric performance. EnergyPlus calculates the detailed energy balance at each hourly time step, providing the total effective solar irradiance () on the inclined surface and the module’s surface temperature approximated with the cell temperature (). The same stratigraphy was assumed for the two considered modules [30,31] with the same glass thickness as indicated on datasheet.

2.1.2. Electrical Modelling and Performance Metrics

Technological differentiation (e.g., PERC vs. TOPCon) is handled exclusively through specific electrical parameters applied in a post-processing algorithm based on the PVWatts model logic [22]. The DC power output () is calculated differently depending on irradiance levels to accurately account for performance losses under low-light conditions. For standard irradiance regimes where , the power output is determined linearly:

Conversely, for low irradiance levels where , a quadratic approximation is employed to model the efficiency drop:

Within these formulations, represents the nominal power of the module under STC expressed in Watt, denotes the temperature coefficient of power (%/°C), is the operating temperature of the cell (°C), is the reference temperature under STC set to 25 °C, and is the reference irradiance under STC set to 1000 W/m2. In this study, is approximated by the “Surface Outside Face Temperature” output extracted directly from EnergyPlus. While the PVWatts model is widely validated [32], it treats the module efficiency primarily as a function of temperature and linear irradiance. It does not explicitly solve the single-diode equation, meaning it simplifies the fill factor variations that occur at extreme temperatures or irradiances. Furthermore, it does not account for spectral mismatch effects, which can be significant for different cell technologies (e.g., N-Type vs. P-Type) under varying atmospheric conditions. However, by coupling this electrical model with the thermal simulation of EnergyPlus, the result is an improvement over standard PVWatts implementations that rely on simplified nominal operating cell temperature (NOCT) models. PVWatts is designed for x-Si modules and is not recommended for thin-film technologies [22]. To focus the analysis exclusively on the photovoltaic technology’s potential, system-level losses—such as inverter conversion efficiency and electrical wiring drops—are intentionally excluded from this calculation step. Once the hourly power output is calculated for each time step of the Typical Meteorological Year (TMY), the annual energy production is calculated by integrating the power profile over the 8760 h of the year. To facilitate comparative analyses independent of system size, two normalized metrics were defined. The first is the pure DC-specific yield (), expressed in kWh/kWp, which quantifies the productivity per unit of installed peak power as defined in Equation (6).

where is the simulation step.

The second metric is the pure DC area-specific yield (), expressed in kWh/m2, which relates the energy output to the gross surface area of the module (). This indicator, defined in Equation (7), is particularly relevant for building-integrated applications where the available surface area is the primary constraint.

To construct the database, a parametric simulation matrix was defined to systematically cover the three key dimensions influencing the energy conversion: location, technology, and orientation. Seven European reference cities, each represented by its standard meteorological file, were selected to encompass diverse continental climatic conditions: Naples (ITA), Madrid (ESP), Berlin (DEU), Paris (FRA), London (GBR), Stockholm (SWE), and Warsaw (POL). These locations were strategically selected to serve as climatic proxies for the main European latitudes, ranging from the Mediterranean basin (Naples and Madrid) to the Oceanic climate (London and Paris), and the Continental (Berlin and Warsaw) and Nordic regions (Stockholm). As previously mentioned, two distinct technologies were modelled using specific electrical and thermal parameters required for the PVWatts, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Module parameters [30,31].

The maximum power point () represents the nominal power output under standard test conditions, while the module efficiency () quantifies the technological performance gap: the TOPCon monocrystalline panel achieves an efficiency of 23.42%, significantly outperforming the PERC variant, which stands at 20.12%. The electrical behaviour is simulated using the simplified PVWatts approach, which calculates DC power output primarily as a function of in-plane irradiance, nameplate DC capacity, and the module’s temperature coefficient of power. Finally, the temperature coefficient of power () serves as a critical thermal input, demonstrating the superior thermal stability of the advanced TOPCon module (−0.29%/°C) compared to the older PERC generation (−0.36%/°C).

To facilitate the identification of the optimal orientation window and quantify the energy penalties associated with sub-optimal installations (e.g., for architectural integration constraints), the surface orientation factor () was introduced [33]. For a specific location and technology, is calculated as the ratio between the specific annual yield at a given orientation and the maximum annual yield achievable in that location under optimal conditions () as shown in Equation (8).

where

- is the tilt angle and is the azimuth angle;

- represents the maximum specific yield found within the simulation grid for the selected city and technology.

This dimensionless metric isolates the geometric performance factor from the absolute climatic magnitude, allowing designers to immediately assess the percentage loss incurred by deviating from the optimal inclination. Finally, a comprehensive orientation grid was simulated for each technology–location pair. All modules were positioned at a fixed height of 15 m above ground level to represent a standard rooftop installation. Consequently, considering that the module orientation is optimized independently of the building envelope, the systems were modelled as building-applied photovoltaics. The orientation parameters were varied, with the tilt ranging from 0° (horizontal) to 90° (vertical) in 5° increments, and the azimuth ranging from 0° (South) to 360° (North) in 5° increments. The simulation framework—comprising seven locations, two technologies, and 1368 orientation scenarios—resulted in a total of 19,152 combinations for analysis.

2.2. Simulation and Data Management

Due to the computationally intensive nature of the campaign, which involved thousands of annual hourly simulations, the calculation process was parallelized using the Python multi-processing library [34]. The computational workload was distributed across 12 logical cores on a 64-bit workstation equipped with an Intel® Core™ Ultra 7 155H processor and 16 GB of RAM. For each iteration, the control algorithm dynamically generated a specific EnergyPlus input file (.idf) by injecting the rotated geometry and material stratigraphy into a base template. Simultaneously, a custom schedule file (.csv) containing the hourly rear convection coefficients (), calculated from the local wind speed, was created and linked to the thermal model. Upon completion of each simulation, the raw EnergyPlus outputs were parsed to extract hourly time-series of effective irradiance and cell temperature. These results were finally consolidated into two structured, updatable JSON databases: a lightweight aggregated database containing annual summary metrics for every data point, and a detailed hourly database storing the full 8760 h profiles of production (W) and meteorological variables for each simulation configuration.

Scaling and New Yield Calculation

A key feature of the Atlas is the estimation of performance for modules with efficiencies differing from the simulated baselines. To mitigate the computational cost of running new EnergyPlus simulations, a linear hourly scaling method was implemented. This approach assumes that while the magnitude of production scales with nominal efficiency, the normalized shape of the hourly profile—driven by climate and module thermophysics—remains constant. The recalculation process begins with the user inputting a new nominal efficiency () and selecting a baseline configuration (technology, location, tilt, and azimuth). Selecting an appropriate baseline technology is crucial to ensure scaling occurs between panels with analogous thermophysical properties. Considering the baseline nominal efficiency , module area (), and the hourly production profile of the baseline module from the database, a dimensionless scaling factor () is calculated:

The new production profile in W/m2 for each hour h is generated by normalizing the base production for the area and multiplying by the scaling factor:

If specific yield output (W/Wp) is required, the profile is further normalized. Finally, the resulting hourly or monthly profile is aggregated and visualized within the application interface. Although the tool primarily visualizes normalized metrics for comparison, the backend explicitly calculates and exports the absolute hourly DC power output (W). This raw power data is essential for engineering applications, particularly for optimal inverter sizing based on the system’s peak production profile.

2.3. Model Validation Methodology

To ensure the reliability of the European Photovoltaic Atlas, a comprehensive two-step validation strategy was implemented. This process addresses the two distinct layers of the tool: the physical simulation engine (EnergyPlus integration) and the mathematical post-processing algorithms (linear scaling).

2.3.1. Physical Engine Validation

The core simulation workflow, which couples the EnergyPlus thermal solver with the PVWatts model, was benchmarked against the authoritative solar radiation databases provided by the European Commission’s PVGIS tool [20]: the satellite-based PVGIS-SARAH3, widely considered the industry standard for solar irradiance in Europe. Recent validation studies against high-quality BSRN ground stations have confirmed the robustness of the SARAH-3 dataset, demonstrating a coefficient of determination () exceeding 88% and ensuring that deviations remain within the target accuracy limits of ground measurements [35]. The validation was performed for three reference cities representing distinct European climatic zones: Naples, Madrid, and Stockholm. To evaluate the model’s geometric robustness, the comparison extended beyond the standard South-facing optimal configuration, incorporating a comprehensive sensitivity analysis. This included varying the azimuth across three directions (0° South, 90° East, and 180° North) at a fixed tilt and varying the tilt angle (0°, 30°, and 90°) at a fixed South orientation. To isolate the accuracy of the radiative transposition and cell thermal balance models from external balance-of-system (BOS) factors, the comparison was conducted on a pure DC-specific yield basis (kWh/kWp). Accordingly, system losses such as cabling, inverter efficiency, and MPPT mismatch were set to 0% in the PVGIS calculation engine, and the EnergyPlus output was normalized to the nominal peak power. A key factor in ensuring a robust benchmark is the temporal alignment of meteorological inputs. To minimize discrepancies arising from long-term climate variability, the EnergyPlus simulations were driven by updated TMY (Typical Meteorological Year) weather files covering the period 2009–2023 [36], rather than the older IWEC datasets [37]. These files, derived from integrated surface database stations, provide a temporal horizon comparable to the satellite-based datasets used by PVGIS-SARAH3. This methodological choice addresses the limitations often found in raw ground station data, such as significant time-series gaps and inhomogeneities [38]. By mitigating these uncertainties related to data quality and long-term irradiance trends, validation can focus primarily on the physical accuracy of the simulation models rather than climatic mismatch. It is relevant to note that the new PVGIS 5.3 engine (released 2025) introduces a specific “crystalline silicon (2025)” model [39], which has been shown to reduce the mean absolute bias error (mabe) to less than 1% for modern modules [39]. The tool retains the option to use the legacy “crystalline silicon” model, characterized by a temperature coefficient of approximately −0.40%/°C [40], which is significantly higher than the −0.30%/°C typical of the updated parameterization [39]. This distinction allows for a dual-technology benchmarking strategy: the Atlas monocrystalline TOPCon module was validated against the new PVGIS “c-Si 2025” standard, while the PERC module was compared against the legacy “c-Si” standard.

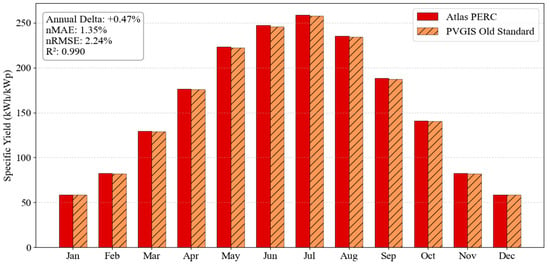

The results, summarized in Table 3, demonstrate the model’s reliability across both technological generations. In Madrid, the PERC module achieves exceptional accuracy with a deviation of only +0.47% from the legacy standard. Similarly, the TOPCon simulation tracks the new standard closely, with a deviation of −1.60%.

Table 3.

Statistics of annual pure DC-specific yield: TOPCon vs. PVGIS 5.3 new crystalline–Si modules and PERC vs. PVGIS 5.3 old crystalline–Si modules.

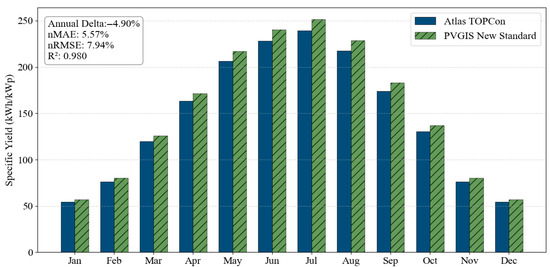

The comparison becomes more nuanced when analyzing the geometric sensitivity, particularly for the TOPCon technology. As detailed in Table 4, the model demonstrates robust behaviour but reveals specific sensitivities to orientation. In Madrid, the deviation at optimal tilt (30°) is −1.60%, maintaining high accuracy. However, in Naples, the deviation is −4.90% at optimal tilt and widens significantly to −13.55% for East orientations.

Table 4.

Detailed comparison by geometric orientation for Madrid, Stockholm, and Naples for TOPCon module.

Three distinct physical behaviours emerge from this analysis. First, a significant azimuthal sensitivity is observed in Naples, where the deviation widens to −13.55% for East orientations. Unlike the South-facing configuration, where optical losses are minimized, the East orientation is heavily influenced by the model’s handling of incidence angles (IAM) and diffuse radiation fractions during morning hours. The Atlas model appears to be more conservative in estimating the effective irradiance reaching the cell under these off-axis conditions compared to the satellite-based PVGIS algorithms. Furthermore, a latitude-dependent discrepancy emerges regarding vertical performance (90° tilt). In Stockholm, the deviation is minimal at +0.76%, whereas in Madrid it becomes more pronounced, reaching −4.88%. This variation is explained by the solar altitude: in Northern Europe, the low winter sun strikes vertical surfaces at near-normal incidence, minimizing optical losses. Conversely, in Madrid, the high solar elevation implies that vertical panels receive predominantly grazing radiation with incidence angles exceeding 70°, a regime where the simplified ASHRAE IAM model tends to diverge from physical reality. Finally, the impact of meteorological forcing is evident when comparing locations. The Atlas model aligns closely with PVGIS in Madrid (Delta −1.60%) despite the high summer temperatures but shows a larger deviation in Naples (Delta −4.90%). This contradiction of the purely thermal hypothesis indicates that the primary source of divergence lies in the underlying irradiance datasets. As described in the user manual for TMY datasets [41], the statistical selection process—prioritizing the most typical months from the historical record—inevitably results in a file structure where extreme solar irradiance events or recent anomalies (such as those captured by real-time satellite monitoring) may be underrepresented. The TMYx files used for Naples likely contain lower cumulative global horizontal and direct normal irradiance compared to the SARAH-3 satellite data, particularly during peak summer months. Therefore, the observed negative delta should be interpreted as a conservative estimation inherent to the standard TMY methodology, rather than a model deficiency. The resulting monthly specific yield profiles for the TOPCon and PERC technologies in Naples are illustrated in Figure 2 and Figure 3, respectively.

Figure 2.

Monthly pure DC-specific yield comparison: TOPCon module, Naples, tilt 30° and azimuth 0°.

Figure 3.

Monthly pure DC-specific yield comparison: PERC module, Naples, tilt 30°, and azimuth 0°.

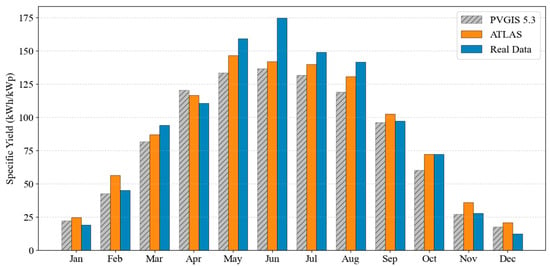

To provide further validation against real operational data, the model was compared with field data recorded in Lublin [42]. The simulation replicated the exact installation parameters of the reference site: a fixed tilt of 25° with South exposure, utilizing Jinko Solar (Shanghai, China) MM445-60HLD-MBV modules [43], so PERC module was simulated and the old crystalline module was set in PVGIS 5.3. Since the Atlas model simulates pure DC energy while the real-world dataset represents AC current output, a comparative analysis was facilitated by assuming a constant system loss factor of 14%. The simulation utilized climatic data for Lublin sourced from the TMYx database [36]. As shown in Figure 4, the model tracks the real production profile closely.

Figure 4.

Monthly AC-specific yield comparison: PVGIS 5.3 vs. ATLAS vs. real data.

The statistical metrics for this real-world validation, summarized in Table 5, compare the Atlas model against both the measured real data and the PVGIS 5.3 simulation. The results demonstrate that the Atlas model significantly outperforms the standard PVGIS 5.3 estimation for this specific case study. The Atlas model predicted a total annual energy yield of 1075.44 kWh/kWp against the measured 1103.71 kWh/kWp, resulting in a marginal deviation of −2.56%. In contrast, PVGIS 5.3 underestimated the yield by −10.28%. Furthermore, the Atlas model achieved a lower normalized root mean square error (nRMSE) of 13.48% compared to 18.17% for PVGIS.

Table 5.

Performance comparison table.

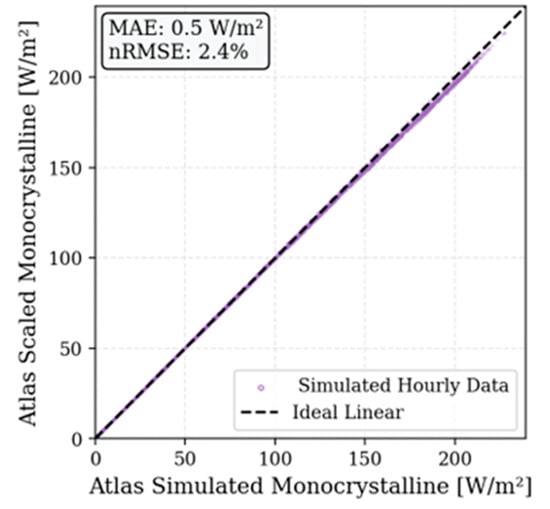

2.3.2. Mathematical Scaling Algorithm Validation

The Atlas incorporates a linear scaling algorithm (Equation (10)) designed to estimate the yield of modules with efficiencies differing from the simulated baselines. To rigorously assess the accuracy limits of this approximation, a validation analysis was conducted comparing the algorithm’s predictions against a benchmark physics-based simulation. The experimental setup for this validation was designed as a “stress test” cross-comparison involving three distinct procedural steps.

First, a full annual hourly simulation was performed for a standard PERC monocrystalline module ) to serve as the source data. Second, a separate ground truth simulation was conducted for a high-efficiency TOPCon monocrystalline module (), providing the reference target for accuracy. Subsequently, the hourly output of the PERC module was linearly scaled using the ratio of their efficiencies ) to predict the TOPCon yield. This approach constitutes a worst-case scenario because the linear model inherently neglects the divergence in temperature coefficients () and thermal emittance properties characterizing the two cell technologies. Despite these simplifications, the analysis (Figure 5) confirms the high precision of the method, returning a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 0.5 W/m2 and a normalized RMSE (nRMSE) of 2.4%. The scatter plot exhibits a near-perfect 1:1 correlation, demonstrating that for engineering purposes, linear scaling introduces negligible error compared to the computational cost of running a new dynamic simulation.

Figure 5.

Scaling algorithm validation.

3. Results

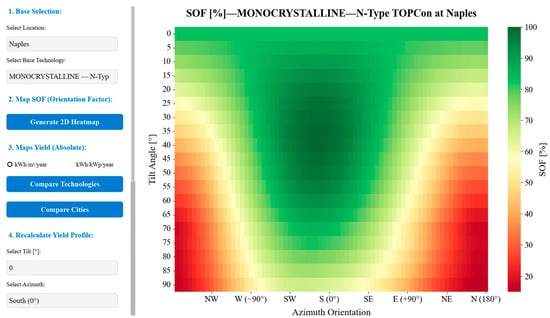

The primary output of the research is the European Photovoltaic Atlas, an interactive software application developed in Python (PyQt6 [44]) that processes the simulated database to support decision-making. Unlike static solar maps, which typically provide a single yield value based on optimal or horizontal inclination, this tool allows users to dynamically explore the multi-dimensional dataset. The analysis of the simulation results, exemplified by the SOF heatmap in Figure 6, enables the immediate identification of the optimal orientation window for each location. While theoretical models often generalize the optimal azimuth as pure South (0°), the integration of TMYx climatic data reveals micro-climatic deviations.

Figure 6.

Photovoltaic European Atlas (PEA)—SOF heatmap for Naples, TOPCon Monocrystalline module.

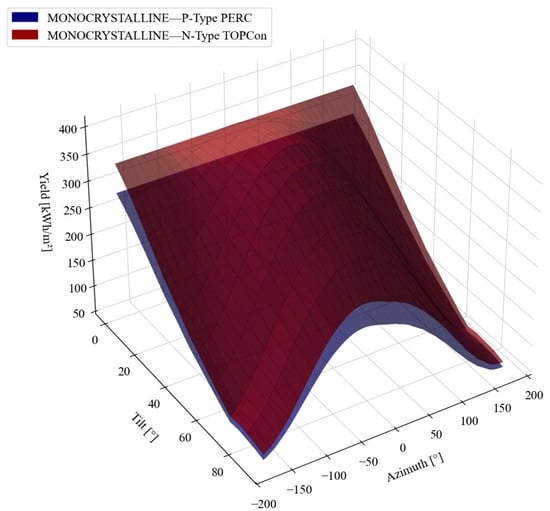

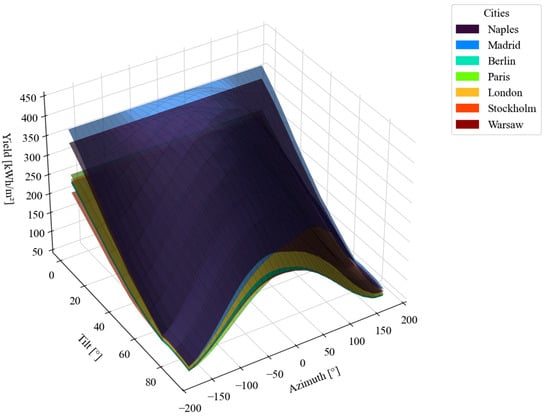

Furthermore, the tool facilitates comparative assessments. As shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8, the “Compare Technologies” and “Compare Locations” modules generate 3D surface plots that visualize the absolute yield surfaces. These visualizations enable the rapid identification of performance gaps between technologies (e.g., monocrystalline PERC vs. monocrystalline TOPCon) across the entire orientation spectrum.

Figure 7.

PEA—Comparing technologies—PERC technology vs. TOPCon technology.

Figure 8.

PEA—Comparing location.

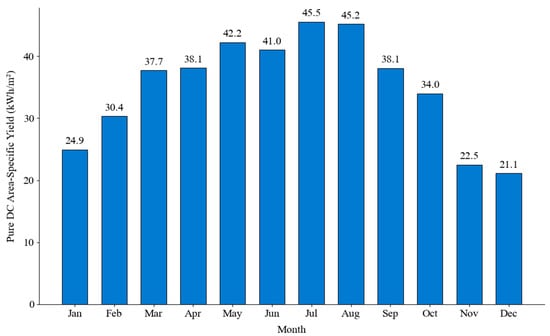

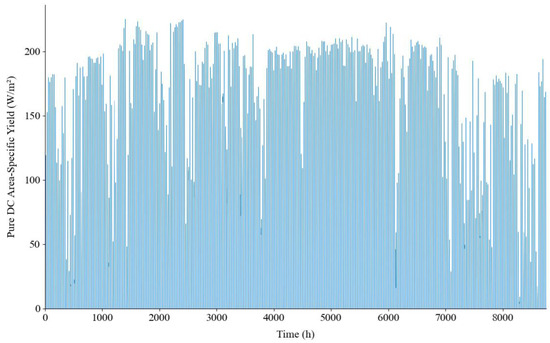

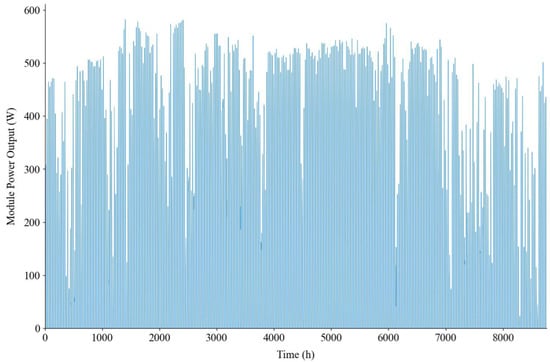

Finally, the recalculation module (Figure 9 and Figure 10) implements the validated scaling algorithm. It allows designers to input a custom module efficiency (e.g., 22.0%) and instantaneously generate the updated hourly or monthly production profile for any selected location and geometry, bridging the gap between pre-calculated databases and specific project requirements. While Figure 10 presents the normalized area-specific yield to facilitate comparison, it is important to note that the tool provides the corresponding absolute hourly power series (W), shown in Figure 11 and exportable in .csv format. By providing either the new module’s peak power or its physical dimensions, the software scales the normalized profile to an absolute value. This granularity allows designers to accurately dimension inverters by identifying the actual maximum power peaks occurring throughout the year.

Figure 9.

PEA—monthly pure DC area-specific yield—with new module efficiency 22.0%, Madrid, tilt 35°, and azimuth 0°.

Figure 10.

PEA—hourly pure DC area-specific yield—with new module efficiency 22.0%, Madrid, tilt 35°, and azimuth 0°.

Figure 11.

PEA—hourly module power DC output—with new module efficiency 22.0%, Madrid, tilt 35°, and azimuth 0°; L = 2278 mm and W = 1134 mm.

Comparative Analysis of European Yields

The simulation results for the seven reference cities were aggregated to analyze the impact of latitude and climate on technology-specific performance. It is important to clarify that the results presented in this section refer to unshaded operating conditions. To isolate the impact of the other parameters (e.g., tilt, azimuth, and technologies), the simulation model excludes the effects of near-shading caused by surrounding buildings or urban morphology. Table 6 summarizes the key performance indicators for the monocrystalline TOPCon technology across the studied European latitudes. It presents the annual global irradiation, the pure DC-specific yield, and the specific yield accounting for 14% system losses [45] under optimal geometric conditions.

Table 6.

Simulation result summary (TOPCon technology).

As detailed in Table 6, the global optimum does not always coincide with the geometrical South. For instance, in Madrid, the analysis identifies an optimal azimuth of 15° (West) combined with a 35° tilt. It is pertinent to note that these specific angular values refer to the discrete nodes of the simulation grid, characterized by a resolution step of 5° for both tilt and azimuth. Consequently, while the exact continuous optimum might lie within the interval surrounding these nodes, the identification of a 15° discrete shift provides robust evidence that the local TMYx weather file captures specific meteorological patterns—such as haze—that shift, combined with thermal estimation, the most productive window towards the afternoon, effectively overriding the theoretical symmetry of solar geometry [8]. Conversely, locations like London and Berlin show a slight preference for East-facing orientations (−10° and −5°, respectively), indicating clearer skies during the morning hours in these climates. Regarding the tilt angle, the results reported in Table 6 confirm the strong correlation with latitude, subject to the same discretization constraints. This trend aligns with the empirical optimization models [9], which establish that maximum annual collection is driven by distinct physical phenomena depending on the climatic zone. Accordingly, southern European cities like Naples and Madrid maximize yield at a discrete tilt step of 35°, which effectively approximates their latitude minus a seasonal correction factor; this “summer maximization” strategy leverages the lower inclination to capture the high solar altitude during the months of peak irradiance. Conversely, in northern European latitudes (typically >45°), the optimization logic shifts. As highlighted in the literature [9], these regions require steeper inclination angles not only to intercept the low solar altitude during winter months but also to effectively capture the diffuse radiation component, which often dominates the global horizontal irradiance due to frequent cloud cover. Consequently, Warsaw benefits from a 40° inclination, while Stockholm requires up to 50° to optimize the annual collection of direct and diffuse radiation against the atmospheric background. Despite these specific optima, the sensitivity analysis presented in Table 7 reveals a high degree of architectural tolerance. For most locations, deviating the azimuth by ±15° from the identified optimum results in a marginal yield loss of less than 1% (e.g., 0.71% for Madrid and 0.77% for London). Even a significant deviation of ±30° in azimuth maintains the losses below 4%, with values ranging from 3.03% in Madrid to 3.57% in Berlin. Sensitivity to the tilt angle appears slightly more pronounced but remains manageable; a deviation of ±15° from the optimal tilt typically incurs a loss between 2.5% and 3.0%.

Table 7.

Sensitivity analysis of pure DC-specific yield to geometric deviations from optimal orientation.

Furthermore, the simulation results highlight the varying magnitude of the performance gap between PV technologies across different climates. The advantage of advanced monocrystalline TOPCon modules over standard technologies is most pronounced in warmer climates. In locations like Naples and Madrid, the TOPCon module, characterized by a superior temperature coefficient (), effectively minimizes thermal losses during hot summer middays when irradiance is highest. Conversely, in colder environments like Stockholm, where operating cell temperatures rarely exceed the standard test condition (STC) reference of 25 °C, this thermal advantage is less critical. In these high-latitude regions, performance is primarily driven by the module’s nominal efficiency and its response to low-light conditions rather than thermal degradation mitigation. This suggests that while high-efficiency technologies are universally beneficial, their economic premium is most justified in regions with high solar radiation and elevated ambient temperatures.

4. Conclusions

This study successfully developed “A European Photovoltaic Atlas”, a comprehensive dynamic simulation framework designed to support the geometric optimization of PV installations. By coupling the EnergyPlus thermal engine with the PVWatts model, the research mapped technology-specific yields across 19,152 configurations, covering distinct silicon technologies and seven European climatic zones. The scientific reliability of this framework was confirmed through a triangulation benchmark against established satellite (PVGIS-SARAH3) and empirical data from an operational site in Lublin. The use of TMYx weather data demonstrated that the simulation engine captures seasonal trends, limiting annual yield deviations to within a 1–13% range against the reference datasets. Furthermore, the analysis confirmed the model’s ability to correctly reproduce the thermophysical performance gap between modern TOPCon monocrystalline and PERC monocrystalline technologies. The internal linear scaling algorithm also proved highly robust even under stress-test conditions, achieving a normalized RMSE of 2.4% and confirming its suitability for rapid engineering prototyping without the need for computationally expensive re-simulations.

Crucially, the sensitivity analysis highlights significant geometrical flexibility. While deviating the azimuth by up to ±15° from the optimal orientation resulted in annual yield losses of less than 1%, a similar deviation in tilt angle incurred a slightly higher—yet manageable—loss of 2.5% to 3.0%. These findings quantitatively demonstrate that PV systems can be adapted to existing building geometries without compromising economic viability, provided installations remain within these tolerance windows. To bridge the gap between these complex dynamic simulations and daily engineering practice, the findings have been translated into an interactive Python application. By offering features such as relative efficiency heatmaps, absolute yield 3D surfaces, and dynamic yield recalculation, this decision-support system ensures that the expansion of urban PV capacity is supported by accurate, technology-specific data, allowing architects and engineers to instantly identify optimal installation windows.

The current analysis focused on seven representative climatic zones to validate the methodology. However, the framework is designed for scalability and the current version presents specific limitations that must be considered. Firstly, the analysis assumes unshaded operating conditions, intentionally neglecting the near-shading effects of urban morphology which must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. Secondly, while the coupled EnergyPlus–PVWatts engine effectively captures thermal inertia, the reliance on the simplified ASHRAE optical model and the semi-empirical electrical formulation may introduce minor deviations at extreme incidence angles or low-irradiance conditions compared to more complex physical models. Finally, the reliance on static TMYx files, while statistically representative, implies that the model output represents a “typical” year rather than historical reality. As noted in the validation against real data, discrepancies are expected and natural, since TMY datasets inherently filter out extreme weather events and recent climatic anomalies observed in operational environments.

To address these gaps, future developments will aim to integrate the PVGIS API directly into the engine. This upgrade will allow users to fetch and simulate specific recent years’ radiation data, minimizing climatic discrepancies. Concurrently, the database will be expanded to include a wider range of European locations and emerging technologies, effectively enhancing the spatial resolution and utility of the Atlas across the continent.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.A., F.d.R., G.M.M. and F.I.; methodology, F.A., F.d.R., F.I. and G.M.M.; software, F.I. and G.M.M.; validation, F.I. and G.M.M.; formal analysis, F.I. and G.M.M.; investigation, F.I. and G.M.M.; resources, F.A. and F.d.R.; data curation, F.I. and G.M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, F.I. and G.M.M.; writing—review and editing, F.A. and F.d.R.; visualization, F.I. and G.M.M.; supervision, F.A. and F.d.R.; project administration, F.A. and F.d.R.; funding acquisition, F.A. and F.d.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Italian Government through the “Accordo di Programma MASE-ENEA sulla Ricerca di Sistema Elettrico Piano Triennale di Realizzazione 2025-2027; Progetto 1.1: Progetto Integrato Fotovoltaico innovativo, efficiente e Sostenibile”.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study, including the complete simulation database and the compiled software tool, are openly available in the Zenodo repository at [https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17714581].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open-Source Link to the Tool

The European Photovoltaic Atlas is available as a standalone executable application for Windows operating systems. The compiled software tool, along with the complete simulation database, is freely available for download at the following permanent repository: [https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17714581].

References

- Kitsopoulou, A.; Bellos, E.; Tzivanidis, C. An up-to-date review of passive building envelope technologies for sustainable design. Energies 2024, 17, 4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2024/1275 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 April 2024 on the Energy Performance of Buildings; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. Buildings—Energy System. Available online: https://www.iea.org/energy-system/buildings (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Mitsopoulos, G.; Kapsalis, V.; Tolis, A. Assessment of city-scale rooftop photovoltaic integration and urban energy autonomy across Europe. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinopoulos, G. Are rooftop photovoltaic systems a sustainable solution for Europe? A life cycle impact assessment and cost analysis. Appl. Energy 2020, 257, 114035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanters, J.; Wall, M.; Kjellsson, E. The solar map as a knowledge base for solar energy use. Energy Procedia 2014, 48, 1597–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzigeorgiou, E.; Martinopoulos, E.G. Solar cadastre for assessment of near-zero energy districts. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1196, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, M.Z.; Jadhav, V. World estimates of PV optimal tilt angles and ratios of sunlight incident upon tilted and tracked PV panels relative to horizontal panels. Sol. Energy 2018, 169, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.K.; Chandel, S.S. Tilt angle optimization to maximize incident solar radiation: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 23, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodhi, M.K.; Tan, Y.; Li, Y.; Naeem, S. Deep learning ensemble and multi-criteria GIS for high-fidelity rooftop solar potential mapping. J. Geovis. Spat. Anal. 2025, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Guo, Z.; Yu, Q.; Dong, K.; Tan, H.; Zhang, H.; Yan, J. Spatiotemporal feature encoded deep learning method for rooftop PV potential assessment. Appl. Energy 2025, 394, 126171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memme, S.; Lepore, D.; Priarone, A.; Fossa, M. Estimating the solar potential of the rooftops of the city of Genova through 3D modelling and anisotropic tiled sky analysis. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2893, 012121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, S.; Rodrigues, M.; Fueyo, N. A method for estimating the geographical distribution of the available roof surface area for large-scale photovoltaic energy-potential evaluations. Sol. Energy 2008, 82, 929–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamasco, L.; Asinari, P. Scalable methodology for the photovoltaic solar energy potential assessment based on available roof surface area: Application to Piedmont Region (Italy). Sol. Energy 2011, 85, 1041–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubiec, J.A.; Reinhart, C.F. A method for predicting city-wide electricity gains from photovoltaic panels based on LiDAR and GIS data combined with hourly Daysim simulations. Sol. Energy 2013, 93, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walch, A.; Rüdisüli, M.; Castello, R.; Scartezzini, J.L. Quantification of existing rooftop PV hourly generation capacity and validation against measurement data. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2042, 012011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, H.; Wang, D.; Zhao, W.; Jiang, W.; Mingze, E.; Huang, C.; Yao, J. Enhancing rooftop solar energy potential evaluation in high-density cities: A Deep Learning and GIS based approach. Energy Build. 2024, 309, 113743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirinyan, E.; Petrova-Antonova, D. Large-scale solar potential analysis in a 3D CAD framework as a use case of urban digital twins. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, S.; Catita, C.; Redweik, P.; Brito, M.C. Modelling solar potential in the urban environment: State-of-the-art review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 915–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Photovoltaic Geographical Information System (PVGIS). Available online: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/photovoltaic-geographical-information-system-pvgis_en (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- U.S. Department of Energy. EnergyPlus Simulation Software, EnergyPlus 9.4.0; U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- PV Performance Modeling Collaborative. PVWatts; Sandia National Laboratories: Livermore, CA, USA, 2019. Available online: https://pvpmc.sandia.gov/modeling-guide/2-dc-module-iv/point-value-models/pvwatts/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- U.S. Department of Energy. EnergyPlus Engineering Reference; U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Dias, P.R.; Benevit, M.G.; Veit, H.M. Photovoltaic solar panels of crystalline silicon: Characterization and separation. Waste Manag. Res. 2016, 34, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, K.; Shukla, A.; Sharma, A.; Biwole, P.H. Thermal response of poly-crystalline silicon photovoltaic panels: Numerical simulation and experimental study. Sol. Energy 2016, 134, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, S.; Hurley, W.G. A thermal model for photovoltaic panels under varying atmospheric conditions. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2010, 30, 1488–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souka, A.F.; Safwat, H.H. Determination of the optimum orientations for the double exposure flat-plate collector and its reflections. Sol. Energy 1966, 10, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffie, J.A.; Beckman, W.A. Solar Engineering of Thermal Processes, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams, W.H. Heat Transmission, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill Kogakusha: Tokyo, Japan, 1954; p. 249. [Google Scholar]

- Luxor Solar GmbH. Eco Line Half Cell M120/345-365 W [Datasheet]. 2020. Available online: https://www.luxor-solar.com (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Jinko Solar. Tiger Neo N-type 580-605 Watt: JKM580-605N-72HL4-(V) [Datasheet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.jinkosolar.com (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Marion, W.F. Overview of the PV Module Model in PVWatts; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C.B.; Barker, G.M. Effects of tilt and azimuth on annual incident solar radiation for United States locations. In International Solar Energy Conference; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2001; Volume 16702, pp. 225–232. [Google Scholar]

- The Python Package Index (PyPI); Multiprocess 0.70.14; UQ Foundation: Brisbane, Australia; Available online: https://pypi.org/project/multiprocess/ (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Gounari, O.; Martinez, A.; Taylor, N.; Alexandris, N. PVGIS 5.3 Dataset Update (JRC139355); European Commission, Joint Research Centre: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Climate.OneBuilding.Org. Repository of Free Climate Data for Building Performance Simulation. Available online: https://climate.onebuilding.org (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- ASHRAE. International Weather for Energy Calculations (IWEC); American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kulesza, K.; Martinez, A.; Taylor, N. Assessment of typical meteorological year data in Photovoltaic Geographical Information System 5.2, based on reanalysis and ground station data from 147 European weather stations. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzipanagi, A.; Taylor, N.; Medina Suarez, I.; Martinez, A.M.; Lyubenova, T.S.; Dunlop, E.D. An updated simplified energy yield model for recent photovoltaic module technologies. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2025, 33, 905–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huld, T.; Friesen, G.; Skoczek, A.; Kenny, R.P.; Sample, T.; Field, M.; Dunlop, E.D. A power-rating model for crystalline silicon PV modules. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2011, 95, 3359–3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, S.; Marion, W. User’s Manual for TMY3 Data Sets. (NREL/TP-581-43156); National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2008.

- Hołota, E.; Życzyńska, A.; Dyś, G. Analysis of Real and Simulated Energy Produced by a Photovoltaic Installations Located in Poland. Energies 2025, 18, 5279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinko Solar MM445-60HLD-MBV. Available online: https://www.pvxchange.com/mediafiles/pvxchange/attachments/EU-MM440-460-60HLD-MB(V)-F1-GE.pdz (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Riverbank Computing. PyQt6 6.4.0. 2022. Available online: https://pypi.org/project/PyQt6/ (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Dobos, A.P. PVWatts Version 5 Manual. No. NREL/TP-6A20-62641; National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2014.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.