Abstract

Knowledge management (KM) is crucial for organisational success in volatile, uncertain, and ambiguous environments. However persistent operationalization issues hinder its interaction with Project Management (PM) and Human Resource Management (HRM). In construction, skill shortages, demographic shifts, rapid technological breakthroughs, and project complexity disrupt organisational knowledge systems. This study examines the growth of KM in construction research and how its integration with PM and HRM might improve organisational resilience. This staged review included bibliometric analysis and narrative synthesis. A bibliometric mapping of Scopus and Web of Science peer reviewed literature (1998–2024) identified publishing trends and thematic clusters, followed by rigorous screening and narrative synthesis of the final corpus. Analysis showed a considerable growth in KM-related construction research since 2016. A repository-focused strategy is giving way to interconnected, human-centred frameworks that highlight social interaction, governance, and digital capability development. Five literature gaps remain: (1) limited operationalisation of core KM constructs like trust, socialisation, and knowledge transfer; (2) misalignment between KM, PM, and HRM domains; (3) inadequate integration of human-centred knowledge practices with emerging digital technologies; (4) a lack of cross-regional comparative research; and (5) a weak theory–practice bridge for KM implementation in construction organisations. Through gap synthesis, this work provides an organised approach for future research, along with practical advice on KM-PM and HRM integration for organisational resilience.

1. Introduction

Organisations increasingly compete based on their ability to create, leverage, and apply knowledge to overcome industry challenges [1]. In project-based construction firms, tacit knowledge loss stems from inadequate knowledge management (KM), an ageing workforce, and transient project teams, undermining organisational resilience, productivity, and project delivery [2,3]. Organisational resilience, the ability to anticipate risks and effectively respond to unforeseen disruptions, is fundamentally dependent on a strong knowledge base [4]. For instance, in the construction industry, engineers and their expertise are vital resources for designing, planning, and executing complex projects [5].

Polanyi [6] distinguished knowledge into two types: explicit, which is codifiable and stored in documents, manuals, and databases; and tacit, which is experiential, personal, and difficult to formalise. Tacit knowledge is particularly valuable in construction as it enables practitioners to apply contextual expertise to interpret explicit design criteria [7]. It is built through accumulated experience [8]. Construction is a knowledge-intensive industry; therefore, intellectual capital drives efficiency, advantage and resilience [9].

Nonetheless, organisational resilience is being threatened by the lack of skilled labour due to talent shortages. This increasingly leads to operational setbacks that undermine competitive advantage. This challenge is particularly acute in engineering and construction, where persistent shortages continue to affect firms globally [10]. Recent reports indicate that 86% of construction companies and 77% of organisations in related sectors struggle to find qualified candidates [11]. The problem is further intensified by an ageing workforce, with experienced engineers retiring faster than new professionals are joining the field [12,13].

The old-age dependency ratio (OADR) is the proportion of individuals aged 65 and over relative to the working-age population aged 20 to 64 years. Globally, the OADR is increasing, and the related retirement trends generate increased demand for skilled personnel, placing additional pressure on existing resources [14]. These pressures are intensified by the transient nature of project-based teams [15], leading organisations to depend increasingly on external talent agencies whose recruits often fail to close existing knowledge gaps [16,17]. Such deficits accelerate knowledge loss and ultimately weaken organisational resilience [3].

Consequently, knowledge management (KM) has become a crucial approach for improving resilience in the construction sector [18,19]. KM supports the identification, transfer, and retention of knowledge through practices such as knowledge mapping, work shadowing, and communities of practice, as well as through digital tools like building information modelling (BIM) and artificial intelligence (AI) [20]. Formal mentoring and apprenticeship programmes, along with lessons-learned archives, are further effective mechanisms for transferring critical tacit knowledge before retirement, thereby improving knowledge transfer and retention [3,21]. However, the adoption of KM is still limited, with only 9% of surveyed leaders expressing confidence in their organisation’s KM capabilities [22].

KM enhances resilience in global construction firms via knowledge transfer, retention, and deployment [23,24,25]. This research examines how KM strengthens resilience. Using bibliometric analysis and narrative synthesis (1998–2024), this study identifies leading authors, thematic clusters, and enablers such as absorptive capacity, governance, and human–technology integration,. In so doing, this article highlights the persistent operationalisation and integration gaps between KM, PM, and HRM.

The definition of gaps has three dimensions that will be addressed through this study’s central research question.

Firstly, the combination of blurry definitions and measurable indications for core KM concepts (trust, knowledge transfer, tacit knowledge) makes implementation equivocal, while the evaluation of results adds further challenge.

Another key issue is the lack of linkage between KM theory and its onsite implementation: insights make up part of the academic literature but are not integrated into project management processes.

Finally, KM, PM, and HRM systems operate as individual domains rather than integrated resilience mechanisms; this results in an incoherent organisational response to workforce volatility and knowledge loss [23,24,25] (see Section 3.3).

Central Research Question

How can organisations address gaps in the operationalisation of knowledge management (KM) to integrate KM, project management (PM), and human resource management (HRM), and to strengthen organisational resilience in the construction industry?

2. Materials and Methods

This study adopted a multi-phase approach that combines bibliometric analysis with a narrative synthesis technique to analyse the literature concerning KM’s role in creating resilient construction organisations. A constructivist lens [26] underpins the analysis, viewing knowledge as created through interaction with our environment. Caputo and Kargina [27] posited that individuals actively construct knowledge and interpret reality subjectively. Therefore, this review considered how collaboration, dialogue, and social interaction enable crucial knowledge transfer and support organisational resilience.

2.1. Data Collection and Search Strategy

This study collected data from Scopus and Web of Science, widely recognised repositories of peer-reviewed journals in engineering and management [26], with datasets combined using the approaches outlined by Caputo and Kargina [27].

2.1.1. Search Period Justification

The search period was established as 1998–2024, indicating the limited presence of focused research on construction knowledge management prior to this timeframe. Consistent with this rationale, the earliest publication identified in the retrieved dataset dates from 1998.

The year 2024 was established as a clear temporal limit for the core analysis, while recognising the potential of research emerging in 2025. Selected recent publications from 2025 were included where necessary to ensure currency and relevance to the discussion.

2.1.2. Complete Boolean Search Strings

Focus was directed at knowledge management articles pertaining to the construction sector using Boolean operators across Scopus and Web of Science.

2.1.3. Search String 1 (KM Focus)

(‘knowledge management’ OR ‘knowledge transfer’ OR ‘knowledge retention’ OR ‘knowledge sharing’)

AND (‘construction’ OR ‘construction industry’ OR ‘construction project’)

2.1.4. Search String 2 (Integration Focus)

(‘knowledge management’ OR ‘knowledge transfer’)

AND (‘project management’ OR ‘human resource management’ OR ‘HRM’)

AND (‘construction’ OR ‘construction industry’)

2.1.5. Search String 3 (Organisational Resilience Focus)

(‘organisational resilience’ OR ‘organisational resilience’)

AND (‘knowledge management’ OR ‘knowledge transfer’)

AND (‘construction’)

Filters Applied: Peer-reviewed articles; Publication date 1998–2024; English language only.

2.1.6. Search Screening Process:

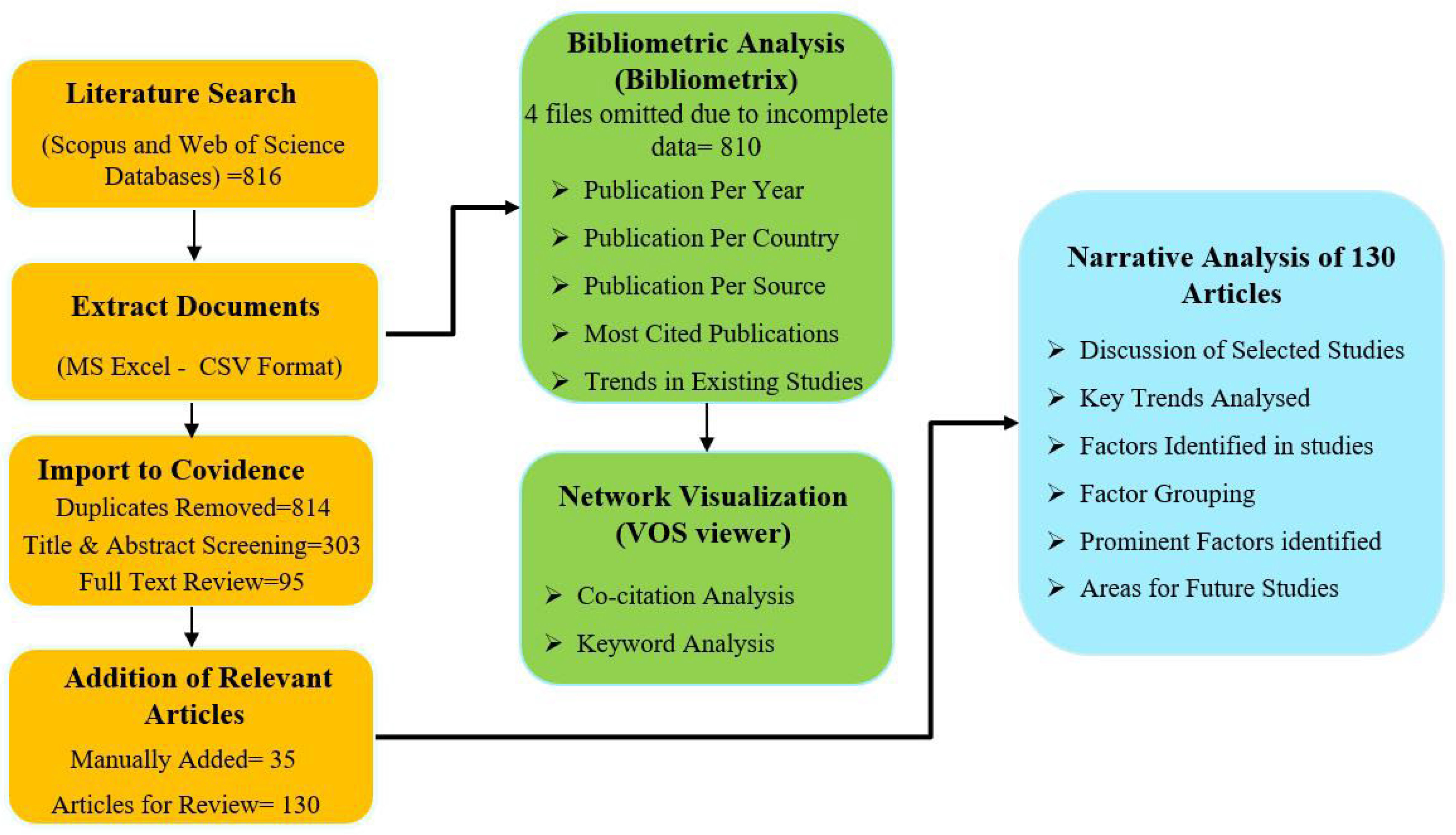

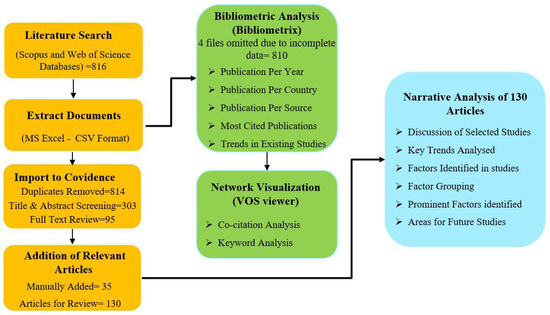

Initial search yield: 816 articles; Stage 1 (Title/Abstract Screening): 303 articles retained; Stage 2 (Full-Text Review): 95 articles retained; Stage 3 (Citation Tracking—Forward and Backward): 35 additional articles; final corpus: 143 articles. An overview of the literature screening process is shown in Figure 1, while the corresponding data generated in Covidence are documented in Appendix A.

Figure 1.

Research framework and process; authors’ own creation.

2.2. Bibliometric Analysis Methods

Bibliometric analysis is effective for analysing large datasets and mapping accumulated knowledge [28]. This analysis used Bibliometrix (RStudio: v4.4.1; Biblioshiny: v4.1) [29] and VOSviewer (v1.6.20) [30] to identify thematic clusters, co-authorship networks, and keyword co-occurrence patterns. Bibliometrix was applied to analyse active authors, countries, publication sources, and research themes, while VOSviewer produced visual network maps that illustrate intellectual relationships. EndNote (v20) was also used to manage bibliographic references and to organise relevant lists.

2.3. Narrative Synthesis

Narrative synthesis integrates results from multiple studies through textual analysis [31]. Paired with bibliometric analysis, it adds qualitative interpretation to quantitative mapping [28,32]. Bibliometrics identifies trends and influential works, while narrative synthesis contextualises these trends. Combining methods strengthens reviews by merging statistical rigour with interpretive insight [33]. This mixed-method strategy provides a structural overview of KM research and an in-depth understanding of how KM enhances resilience in construction organisations.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Bibliometric Analysis Findings

3.1.1. Publication Trends and Research Growth (1998–2024)

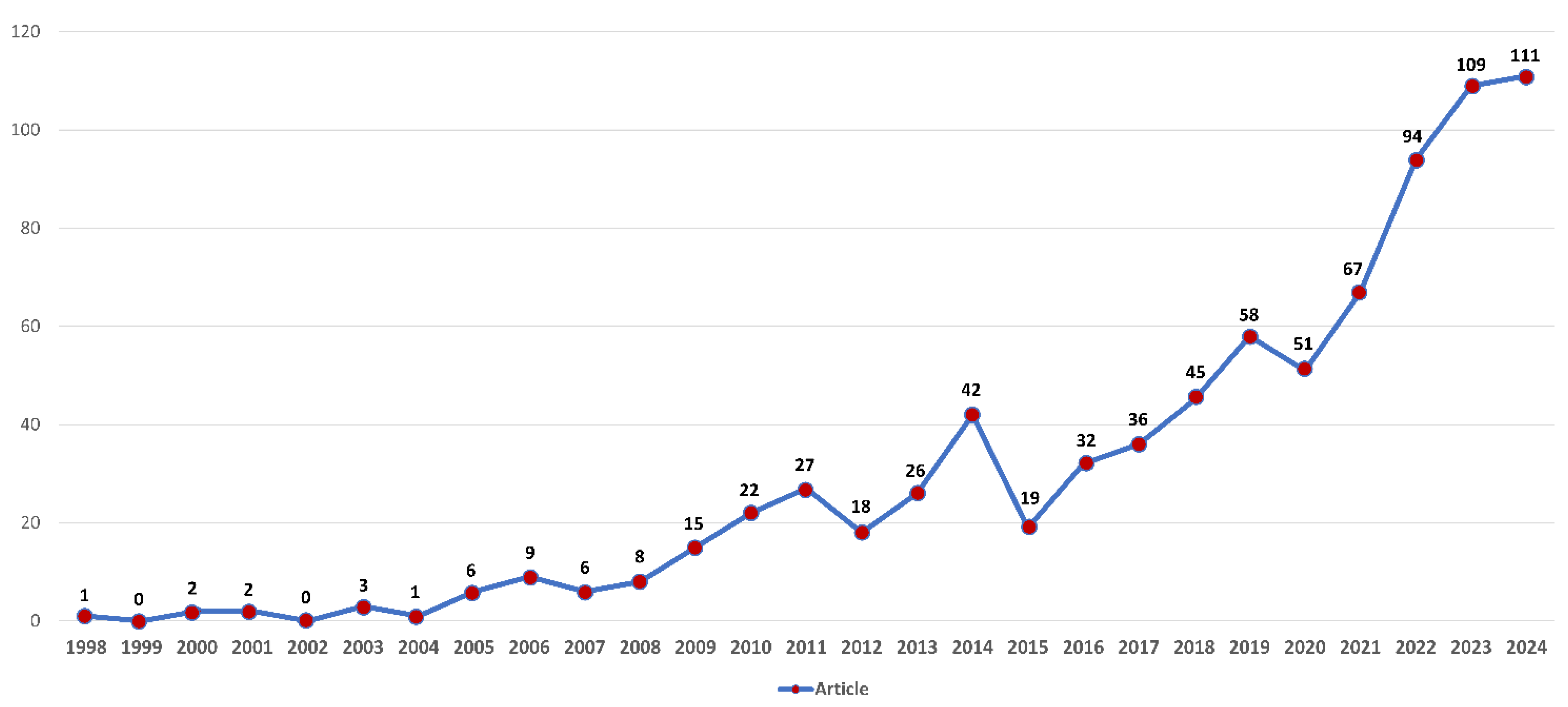

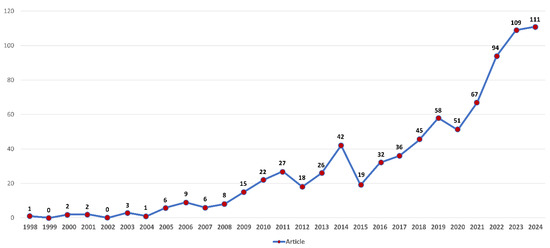

Figure 2 depicts the annual frequency (f) of publication for KM articles relating to the construction industry from 1998 to 2024. From 1998 (f = 1) to 2011 (f = 27), there was gradual growth, followed by some fluctuations between 2011 and 2015. However, the number of publications rose dramatically from 2016 (f = 32) to 2023 (f = 109), reflecting an accelerated pace of research underlining the rising significance of KM as a means of achieving construction project success [34]. Three distinct periods are evident: gradual growth (1998–2011, f = 1 to 27), fluctuations (2011–2015), and accelerated growth (2016 onwards, 2023 f = 109), reflecting increased scholarly attention to KM as a strategic priority for building construction organisational resilience [34,35,36].

Figure 2.

Annual publication frequency in construction knowledge management research (1998–2024). Note: ‘f’ denotes publication frequency (number of articles published annually). Data were extracted using Bibliometrix (RStudio v4.4.1; Biblioshiny v4.1). Three distinct periods are evident: gradual growth 1998–2011 (f = 1 to 27); fluctuations 2011–2015; and accelerated growth 2016 onwards (2023: f = 109), reflecting increased scholarly attention to KM as a strategic priority for building construction organisational resilience.

3.1.2. Geographic Patterns and International Collaboration

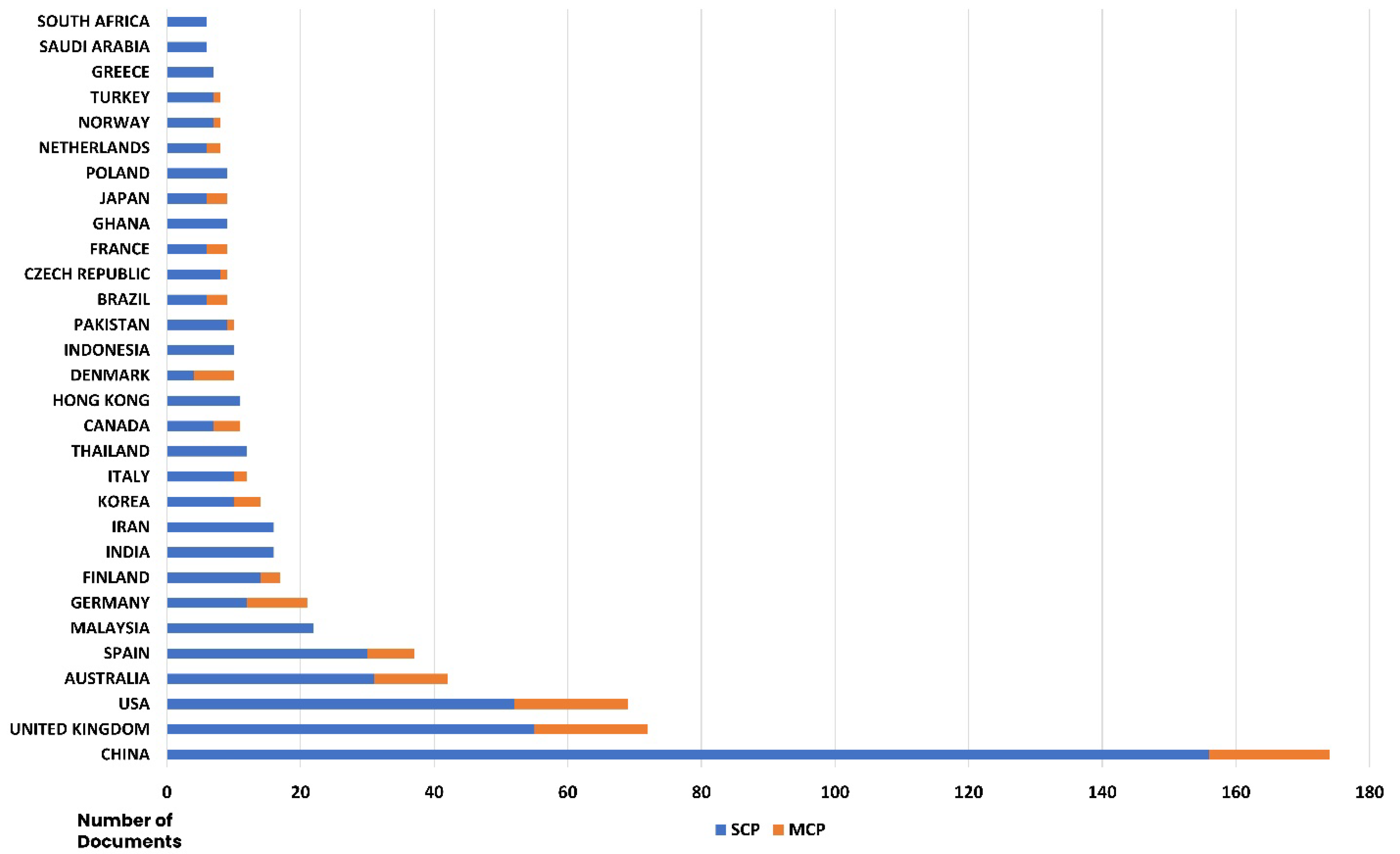

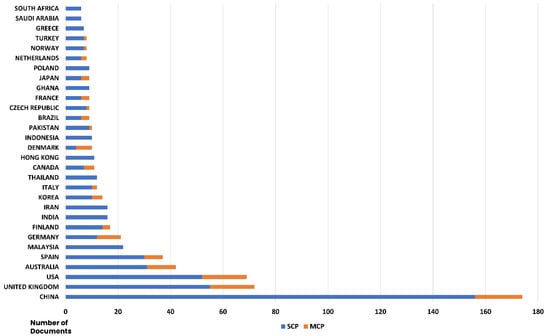

Based on corresponding author data, the extracted journals in this study originated from 66 countries. The number of publications attributed to authors from the leading countries is shown in Figure 3. Articles were categorised by colour, with blue representing single-country publications (SCPs) where research is conducted solely within one country, and orange indicating collaborative research involving multiple countries (MCPs).

Figure 3.

Publications by Country. Data were extracted using Bibliometrix (RStudio v4.4.1). Blue = Single-Country Publications (SCPs); Orange = Multi-Country Publications (MCPs).

The chart highlights the countries at the forefront of scientific research and the collaboration between them. China has the highest number of publications, 174, with the majority being in the SCP category. This indicates strong output in terms of domestic research [35].

Analysis of the United Kingdom (72), the United States (69), and Australia (42) provides more balanced contributions of both SCPs and MCPs, which shows a strong regional and cooperative effort [37]. Spain (37), Malaysia (22), and Germany (21) exhibit significant contributions through collaborative and national output, whereas India (16), Iran (16), and Ghana (9) primarily produce domestic SCPs.

China’s strong output in the SCP category (174 documents) warrants deeper contextual analysis. Several interdependent factors contribute to this pattern.

Contextual Analysis of China’s SCP Dominance

Language and Indexing Barriers: Research conducted in Mandarin or published in Chinese academic journals might not be included in English-language international databases like Scopus and Web of Science. This can lead to a systematic bias, favouring English-language publications and under-representing collaborative work with Chinese researchers.

Regulatory and Economic Context: China’s extensive domestic construction sector, coupled with state-directed research priorities, may incentivise publication in local journals and prioritise domestic case studies over international partnerships, specifically, where the research focuses on National regulations and building codes.

Institutional Research Maturity: Construction KM is a relatively new field of study in China when compared to North America and Europe. This could explain the emphasis on foundational domestic case studies and research aimed at practitioners, rather than on cross-national comparisons.

Conversely, the relatively even distribution of SCP–MCPs in the United Kingdom (72 publications; approximately 54% MCPs), the United States (69 publications; roughly 48% MCPs), and Australia (42 publications; about 57% MCPs) suggests the presence of more mature international research networks. These networks have a longer history of collaboration across institutions and nations. This difference highlights the critical need for more publications involving multiple countries and comparative studies across different regions.

3.1.3. Intellectual Structure: Authors, Themes, and Citation Networks

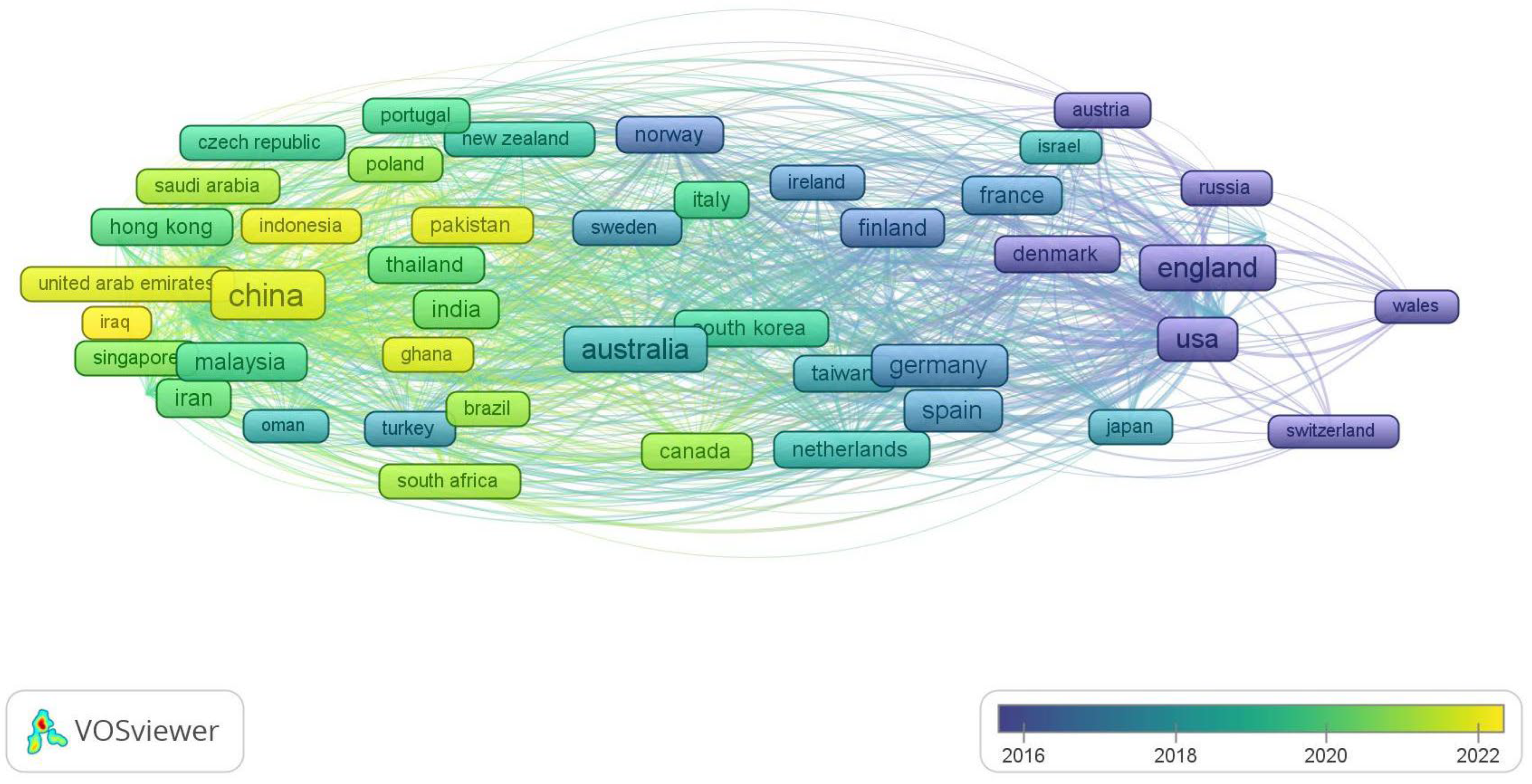

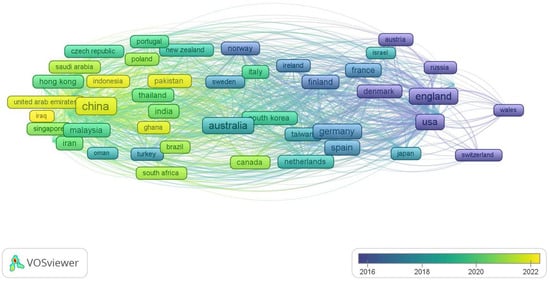

The bibliographic coupling in Figure 4 represents the networks of collaborative countries with at least five articles and a minimum of 20 citations. The strength of bibliographic links was calculated using VOSviewer, and 50 countries met these criteria. For example, in the overlay visualisation mode, the colour-coded timeline highlights trending nations, with China being the most prevalent in recent years, while the United States and England were dominant in 2016.

Figure 4.

Bibliographic coupling of countries. Visualisation generated using VOSviewer (v1.6.20; Van Eck and Waltman, 2010, [30]). Network analysis includes 50 countries meeting the minimum criteria (≥5 articles AND ≥20 citations). Colour-coded timeline overlay highlights trending nations over time. Network links represent bibliographic coupling strength.

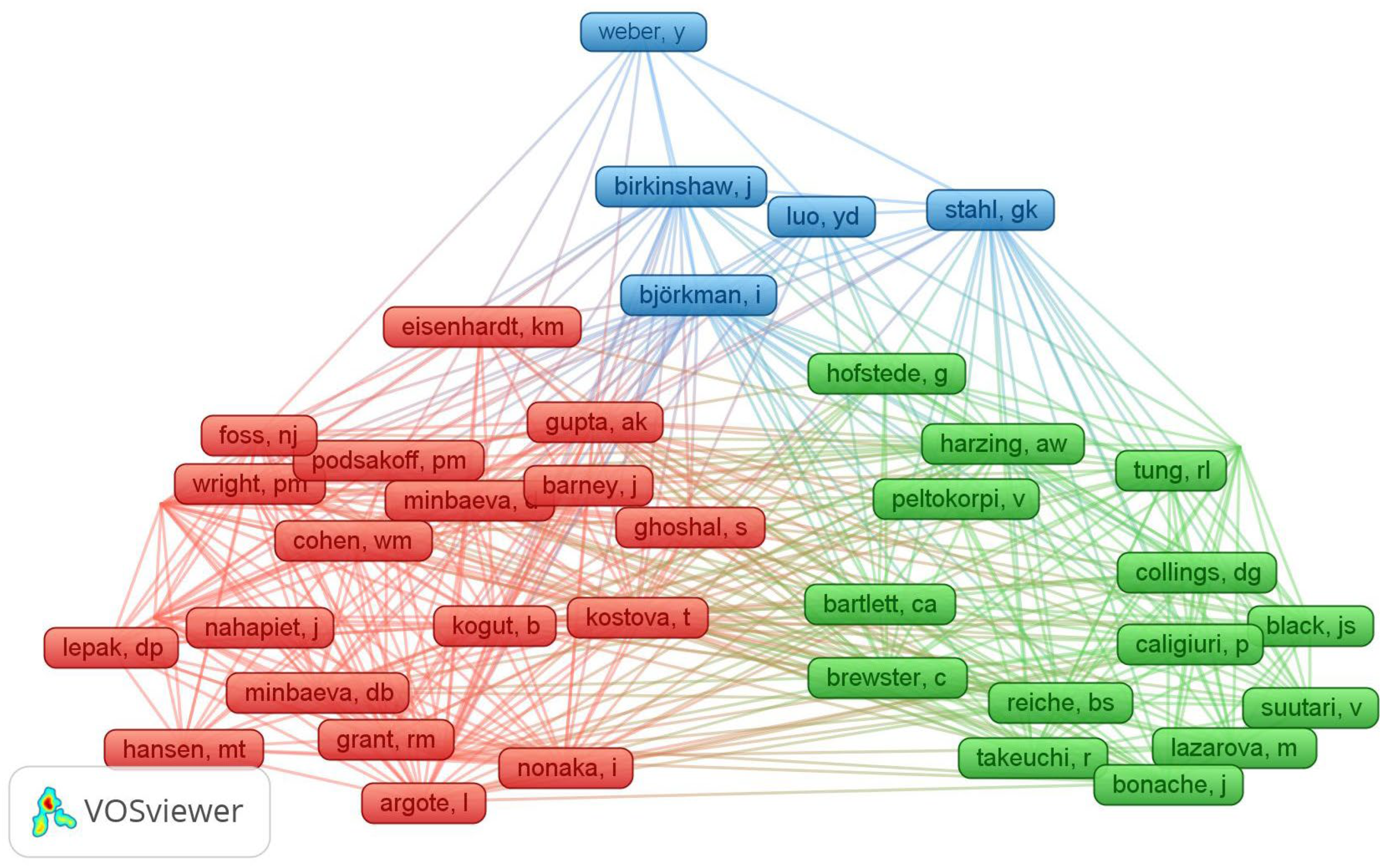

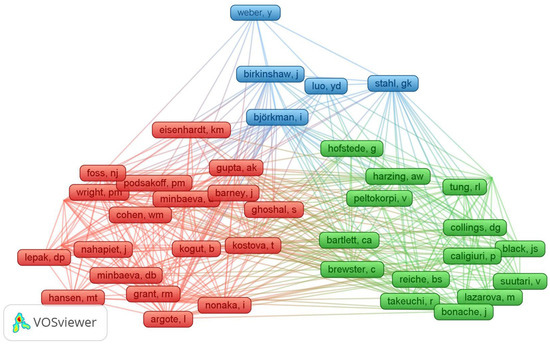

Figure 5 shows the authors with the strongest overall relationships in a co-citation network map generated using VOSviewer. This image illustrates networks of highly cited authors with at least 50 citations. Of the 12,118 cited authors, 41 met the criterion and were clustered based on the strength of their co-citation links with other authors. Each node represents an author, and its size indicates the number of citations. Connecting lines depict co-citation links; thicker lines represent stronger connections and a higher frequency of co-citation between the authors. Colour-coded clusters indicate groups of cited authors.

Figure 5.

Co-citation analysis of highly cited authors. Visualisation generated using VOSviewer (v1.6.20; Van Eck and Waltman, 2010, [30]). Analysis includes 41 authors with ≥50 citations from 12,118 total cited authors. Node size = citation frequency; line thickness = co-citation strength. Colour-coded clusters represent intellectual domains: Red = knowledge transfer and organisational learning; green = human resource management and organisational behaviour; blue = corporate strategy and leadership.

The red cluster shows studies by Nonaka [38], Barney [39], Minbaeva [40], and Cohen and Levinthal [41], and it is concerned with knowledge transfer and organisational learning. Hofstede [42] and Bartlett [43], represented by green, focused on human resource management and organisational behaviour, while the blue cluster includes the work of Birkinshaw [44], Stahl [45], and Weber [46], who researched corporate strategy and leadership.

These foundational cited authors (publications 1990–1997) represent seminal work identified through co-citation analysis. Although these works predate the 1998 search start date, they appear with high frequency in citations within the 816 retrieved articles (1998–2024), indicating their enduring theoretical influence on contemporary construction KM research. Co-citation analysis, as a methodology, identifies intellectually influential historical work regardless of publication year. Strong links between clusters imply substantial integration and cross-citation, highlighting the impact of key authors across several research areas. The extracted dataset contained 2489 keywords collated using VOSviewer.

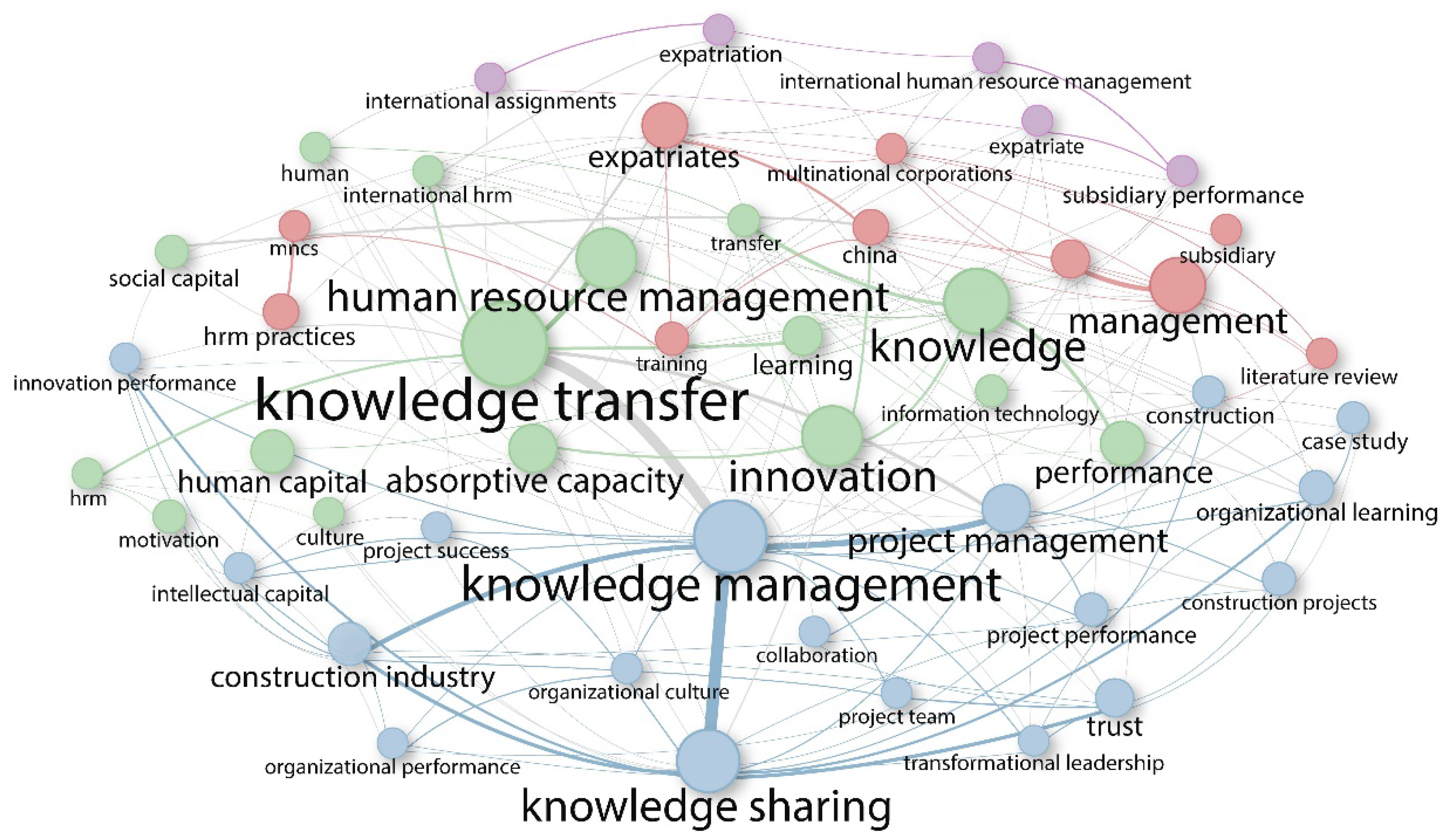

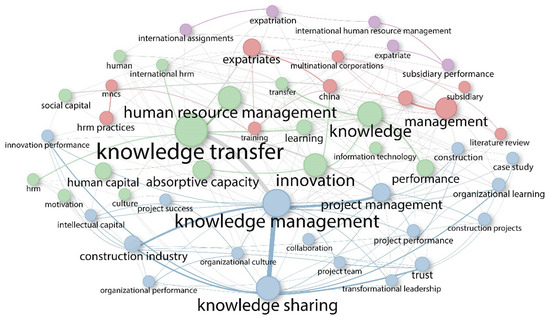

The 50 dominant keywords were cross-referenced with research themes using Bibliometrix, with the results mapped in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Thematic map. Generated using Bibliometrix. Visual representation of major themes in construction KM research. Bubble size indicates research volume; positioning reflects thematic relationships. The colours in the map represent thematic clusters. Each cluster groups keywords that frequently appear in the same publications, thus indicating related research areas within the wider domain of knowledge management.

Table 1 below presents the frequency of thematic occurrence across the bibliometric dataset to illustrate dominant research themes. Please note that inclusion in the table does not imply that all cited studies were analysed in the final narrative synthesis.

Table 1.

Key themes.

3.2. Narrative Review and Thematic Analysis

3.2.1. Challenges to Knowledge Retention in Project-Based Organisations

Projects are temporary endeavours where knowledge is created but seldom transferred to the broader organisation [47]. This paradox of project knowledge, as noted by Bakker et al. [48], undermines the continuity of knowledge and restricts organisational learning [49]. The research highlights the key factors that affect how knowledge is effectively transferred and retained within project-based organisations.

- 1.

- Adherence to Global Standards

Mandatory adherence to multiple regulatory frameworks and cross-regional legal requirements distinguishes international construction projects from domestic endeavours [50,51]. Consequently, construction firms engaged in international ventures must understand these requirements to ensure adherence to safety protocols, environmental regulations, and local government legislation [52]. Compliance with international industry benchmarks mitigates institutional risks and strengthens organisational resilience. The implementation of robust knowledge management (KM) strategies can assist organisations in effectively disseminating relevant knowledge across both global and local domains, thereby facilitating compliance and bolstering resilience [36,53].

- 2.

- Cultural Diversity and Knowledge Silos

International construction projects are characterised by culturally diverse teams of individuals, each bringing distinct expertise [25,54]. Although cultural differences can hinder the processes of knowledge creation and dissemination [55], the presence of expatriates provides diverse viewpoints and innovative ideas, potentially facilitating the generation of new knowledge [52]. Nonaka et al.’s [56] seminal SECI model exemplifies such interactions, highlighting socialisation as the primary mechanism for the sharing of tacit knowledge. This model posits that knowledge conversion occurs through interpersonal engagement, thereby establishing face to face communication as the fundamental element for the transfer of tacit knowledge within organisational contexts.

A prevalent issue within culturally diverse project teams is the existence of knowledge silos, stemming from misunderstood cultural nuances and communication challenges. These silos can impede knowledge retention by restricting the flow of knowledge between disciplines and across teams [57]. Studies indicate that cultural diversity frequently presents a considerable obstacle to knowledge transfer on international construction projects, potentially diminishing trust, hindering communication and adversely impacting project outcomes [7]. Facilitating effective knowledge management in such settings requires the cultivation of social capital through cultural awareness, mutual trust, and transparent communication channels [58].

- 3.

- Employee Turnover and Retirement

Employee turnover and retirement substantially diminish human capital, thereby affecting organisational potential for innovation and competitiveness [57]. Tacit knowledge is particularly at risk in ageing workforces, where experienced personnel retire at a rate that exceeds the organisation’s ability to recruit or cultivate new talent [59]. This issue is exacerbated by the global increase in the Old-Age Dependency Ratio (OADR), which measures the proportion of people aged 65 and above relative to the working-age population (usually defined as those aged 20–64 or 15–64) [3].

Based on Duchek’s [4] resilience model, poor knowledge retention systems reduce an organisation’s ability to anticipate and manage challenges. Employing HRM practices such as succession planning and onboarding, in conjunction with KM mechanisms like mentoring and communities of practice, ensures that tacit knowledge is systematically captured, transferred, and retained [60].

The integration of human resource management (HRM) and knowledge management (KM) practices with project management (PM) functions provides a robust framework that enables the leveraging of knowledge to enhance organisational resilience [61,62,63]. This holistic framing aligns with the concept of “absorptive capacity,” defined as an organisation’s capacity to identify, assimilate, and apply knowledge, subject to its ability, motivation, and opportunity [64].

Within this framework, the strengthening of stakeholder relationships is essential for preserving social capital and enhancing absorptive capacity, thus contributing to greater organisational resilience [24,58,65]. Consequently, organisations that view all employees as stakeholders experience improved collaboration and knowledge integration [53,66].

3.2.2. Evolution of Knowledge Management Research in the Construction Industry

KM in construction has taken a unique route, governed by the project-based nature of an industry prone to skill shortages [1]. Codification, explicit knowledge repositories, lessons learned, best practices, and technical information have traditionally been used in the construction industry [36]. However, temporary teams and high staff turnover characterise construction projects, making repositories insufficient means of retaining project knowledge [67].

Reviews and critiques emphasise that early reliance on repositories overlooks the importance of tacit knowledge and social knowledge sharing, which Nonaka and Takeuchi [68] strongly advocated [69,70].

Early 2000s studies marked a shift towards project-based knowledge management (KM), integrating knowledge practices into project management (PM) and recognising the social nature of learning within projects [71]. Key KM tools such as project completion reviews, communities of practice, knowledge audits, and mentoring programmes gained prominence as both KM mechanisms and human resource management (HRM) practices that strengthen organisational capabilities [28]. Incorporating these tools into PM processes like stage gates and project closeouts bridges HRM’s focus on workforce strengths with KM’s ability to capture and retain tacit knowledge across project lifecycles [72].

This evolution was institutionalised through formal standards. The integration of KM into quality management standards (ISO 9001, 2015 [73]) and project management frameworks (PMI’s ‘Manage Project Knowledge’, 2017) elevated KM as an essential component of established practice [74].

Most significantly, the 2018 release of ISO 30401 [75], the first international standard for KM systems, facilitated the strategic ratification of KM globally. This is affirmed by bibliometric evidence showing rising prominence of concepts such as ‘knowledge transfer’ and ‘collaboration’ [26,52]. Post 2016, KM research advanced exponentially, in line with Industry 4.0 and increasing global skills shortages [67]. Recently, KM-based digital technologies and BIM have facilitated real-time knowledge exchange among stakeholders [76,77].

3.2.3. Operationalisation of Core KM Constructs

An operationalisation gap exists in how ‘trust’ is defined and measured in construction KM contexts [62]. Rather than conceptualising trust as a diffuse psychological state, construction KM requires operational definition through concrete, measurable dimensions:

- (1)

- Reliability Indicators: Adherence to knowledge-sharing agreements, measured by the percentage of agreed exchanges fulfilled on time, is a key metric. Also important are consistent communication patterns, including the frequency and punctuality of updates. Finally, the ability to follow through on commitments, regardless of cultural background or project team, is essential.

- (2)

- Transparency Measures: Visible decision logs that formally document choices, along with clear rationale for project changes, should be stored in project repositories. These, coupled with accessible records of communication, help to reduce knowledge gaps between project teams.

- (3)

- Reciprocity Assessment: Evidence of mutual support across project disciplines, as shown by knowledge-sharing equity audits, along with a fair distribution of knowledge resources and training opportunities [8,78]. Another important factor is the absence of knowledge hoarding or hiding by dominant groups and team members [79].

Similarly, socialisation—the primary phase of the SECI model, in which tacit knowledge is transferred through direct interpersonal interaction—is frequently reduced in practice to informal conversation; however, it can be a vital source of knowledge [38,56]. In contrast, construction-focused knowledge management should operationalise socialisation through formally structured joint problem-solving sessions in which culturally diverse teams collaborate on shared project challenges with deliberate reflection on individual and collective knowledge contributions [80]. Operationalising through cross-functional communities of practice characterised can be defined by inclusive membership, scheduled engagement, and documented knowledge artefacts. This is measurable through participation indicators such as attendance and active contribution. Socialisation through formal mentoring arrangements conducted on a one-to-one or small-group basis with explicit knowledge transfer objectives can be gauged by periodic assessment of knowledge acquisition, along with documented outcomes including individual assessments and improvements in project performance.

This operationalisation gap between recognising trust and socialisation as critical enablers and systematically measuring their improvement is significant. Without measurable indicators, organisations cannot determine whether KM interventions are effective, nor can they identify areas for improvement.

3.2.4. Digital Technologies and AI-Driven Knowledge Systems

Recently, KM-based digital technologies and BIM have facilitated real-time knowledge exchange among stakeholders. Two concrete examples illustrate the mechanisms as follows:

Example 1—Integrated BIM Platforms with AI-Driven Change Management

A multinational infrastructure megaproject (construction value > USD 1 billion) utilised integrated BIM platforms embedded with AI-driven change request tracking systems. The system automatically tagged change requests with relevant project information and flagged potential impacts on other project areas, reducing knowledge retrieval time from field teams by approximately 40%. Critically, the system captured tacit knowledge from site engineers through automated decision-logging: when engineers made field decisions, the system prompted them to document their reasoning and alternative approaches considered, transforming tacit site knowledge into accessible organisational learning [81,82].

Example 2—Predictive Analytics for Workforce Planning

A large construction firm implemented predictive analytics applied to workforce scheduling algorithms that enabled the anticipation of skill gaps 6–9 months in advance by analysing project pipelines, current workforce demographics, and historical turnover patterns. This advance notice allowed targeted mentoring of mid-career professionals, structured succession planning, and specialist recruitment with appropriate lead time, rather than responding reactively to sudden departures [83,84].

The examples in this section are illustrative cases synthesised from the existing literature rather than original empirical analyses.

Critical Insight: Organisational Gap, Not Technological Gap

Technology alone does not ensure knowledge retention. Studies show that changes need to be accompanied by changes in HR practices, trust-building interventions, and structural changes in communication norms [9,85,86]. In contrast, teams that integrated technology with a structured mechanism for human expertise reported adoption rates of over 70% as well as measurable improvements in project learning outcomes and knowledge retention.

This evidence suggests that the operationalisation gap in digital KM is organisational rather than technological: tools amplify and accelerate human knowledge-sharing practicesbut cannot substitute for the social mechanisms (trust-building, communities of practice, mentoring relationships) that sustain knowledge retention in project-based environments [24,87].

3.2.5. Current Status and Future Developments in Knowledge Management Research

Recent knowledge management (KM) research within construction has witnessed a shift from a narrow focus on repository-driven solutions toward a deep contextual understanding of project knowledge flows. From 2016, bibliometric evidence has demonstrated accelerated publication activity. Themes increasingly centre on digitalisation, project governance, and cross-regional collaboration. Notably, research traditions diverge: Chinese and Singaporean studies highlight policy-led digital roadmaps and mandatory documentation, while North American and European work foregrounds strategic office models and contractual mechanisms. This regional diversity underscores the need for comparative frameworks to capture how local norms, regulatory regimes, and organisational structures either enable or inhibit KM integration and the development of construction resilience.

- 1.

- Knowledge Transfer

Keyword co-occurrence analysis highlighted ‘knowledge transfer’, ‘knowledge sharing’, and ‘knowledge exchange’ as central terminology [88]. Early research was more focused on repositories and best-practice manuals [2,89], whereas recent studies emphasise the importance of relational mechanisms such as trust, social networks, and open communication for managing tacit knowledge in multi-stakeholder projects [62,90,91]. Although the universal aim is mobilising knowledge across organisational and national boundaries, regional differences still exist [57]. Western research emphasises technology-enabled platforms such as BIM and digital twins [77], while African and Asian studies focus on governance, capacity-building, and institutional frameworks [92].

- 2.

- Digitalisation, AI, and Data-Driven KM

Since 2016, data-driven keywords such as ‘artificial intelligence’, ‘big data’, ‘BIM’, and ‘machine learning’ coincide with an increased global focus on Industry 4.0 [93,94]. AI-enabled KM systems improve predictive capacity, decision-making, and codification [95,96] but raise challenges relating to governance, system interoperability, and the risk of undervaluing tacit knowledge [87]. Taking a socio-technical perspective, digital KM should complement relational and experiential practices rather than replace them [80,97].

- 3.

- Knowledge Governance and Policy-Driven KM

In response to systemic skills shortages, from 2018, the concept of knowledge governance has gained prominence and the terms ‘governance’, ‘capacity building’, and ‘institutional frameworks’ have proliferated [59,63,95]. Evidence from China and Singapore shows policy-led initiatives supported by national digitalisation roadmaps and mandatory project knowledge documentation [98]. European and North American research emphasised project management offices (PMO), corporate strategies and contractual governance mechanisms [85], while African studies highlighted the role of government-led initiatives to strengthen KM adoption [99].

- 4.

- Knowledge Management and Organisational Resilience

Effective KM has been increasingly linked to organisational resilience, sustainability, and innovation; it also reduces turnover losses, aids crisis recovery, and sustains innovation [17]. The COVID-19 pandemic underscored digital KM’s role in maintaining operational continuity [100]. Furthermore, KM was inherent in sustainability-oriented studies specifically concerning knowledge retention, organisational longevity, and the sustainable workforce [53]. This relationship between KM and resilience was also supported by research showing that knowledge continuity enhances organisational adaptability during disruptive events [100,101].

- 5.

- Emergent Trends and Thematic Shifts

The traditional view of ‘knowledge storage’ within repositories is being replaced by more dynamic concepts like “ecosystems” and “digital communities of practice” [59]. Research indicates that the focus on tacit versus explicit knowledge has developed to include frameworks that consider the complex interactions between people, technology, and institutions [90]. Conversely, the convergence of project management, organisational learning, and digital transformation supports hybrid knowledge management approaches. Such approaches enhance risk management, supply chain coordination, and innovation systems [54].

Emerging challenges include inter-organisational justice, which examines how approaches to the fairness and reciprocity impact knowledge dissemination among collaborating project partners [8]. Institutional distance relates to cultural and regulatory misalignment within international project-based organisations, representing a significant, yet under-researched, obstacle that knowledge management can potentially mitigate [17,18]. Furthermore, knowledge hiding, whereby employees deliberately withhold their expertise due to concerns regarding competition or job security, is increasingly recognised as a substantial issue [53,102].

3.3. Persistent Gaps in Knowledge Management–Project Management–Human Resource Management Integration

3.3.1. Gap 1: Operationalisation of Core KM Constructs

Construction KM research demonstrates a persistent operationalisation gap: core constructs—trust, socialisation, knowledge transfer—lack precise, measurable definitions [61,103,104]. Trust is often confused with cooperation. Trust should instead be operationalised via reliability of commitments, mutual support, and transparent communication [78]. Socialisation is frequently reduced to informal interaction; instead, it should encompass joint problem-solving and cross-functional community engagement [104]. Knowledge transfer remains conceptually diffused, failing to differentiate between codified and tacit knowledge transfer efficacy [63,86,105].

Operationalising these concepts with measurable indicators will strengthen empirical research, ease practical implementation, and contribute to building organisational resilience [61,80].

3.3.2. Gap 2: Misalignment Between Knowledge Management, Project Management, and Human Resource Management Domains

A critical gap exists: KM, PM, and HRM operate as isolated domains rather than integrated systems supporting resilience [63,106]. Project management emphasises structured knowledge capture; HRM focuses on workforce adaptability; yet KM remains underutilised as a resilience mechanism. This fragmentation causes KM to be perceived as a technical repository rather than a dynamic capability for adaptation and continuous learning. The three domains operate with distinct metrics, communication protocols, and governance structures, preventing coherent organisational response to knowledge challenges.

3.3.3. Gap 3: Integration of Emerging Technologies with Human-Centred Knowledge Management

Artificial intelligence, machine learning, and building information modelling present significant technological possibilities [20,94]. Despite this, research indicates a consistent misalignment between the implementation of these technologies and the practices of human interpersonal knowledge transfer [36,61]. Empirical insights into the design of genuinely integrated human–technology knowledge management systems are still scarce. The examples in Section 3.2.4 show that successfully adopting technology requires more than just the technology itself. It also requires intentional changes to human-centred practices, such as mentoring, building communities of practice, and fostering trust.

3.3.4. Gap 4: Cross-Regional and Cross-Cultural Comparative Knowledge Management Research

KM research exhibits considerable regional variation, encompassing Chinese domestic perspectives, North American project management office (PMO) models, European governance methodologies, and African capacity-building initiatives. The absence of comparative frameworks presents a challenge, as findings derived from one context may not be applicable to others [57]. Bibliometric analysis indicates that 174 of China’s publications are single-country studies, thereby hindering cross-regional knowledge integration and restricting the applicability of their conclusions.

3.3.5. Gap 5: Theory–Practice Bridge in Knowledge Management Integration

A significant gap exists between recognising that KM–PM–HRM integration is necessary and providing practical, actionable guidance on how to implement such integration in construction organisations [61]. This gap particularly affects practitioners and smaller organisations with limited KM expertise. Academic literature identifies issues but offers limited guidance on implementation pathways, sequencing, resource requirements, or success metrics.

4. Future Research Directions

- 1.

- Longitudinal Empirical Research

Longitudinal studies testing KM integration effects on organisational resilience, specifically measuring changes in workforce adaptability, project learning, and recovery capacity following systemic KM–PM–HRM integration. Such research should track measurable indicators of trust (knowledge-sharing equity), socialisation (community participation rates), and knowledge transfer (tacit knowledge capture before retirement).

- 2.

- Methodological Research on Measurement Instruments

Development of valid, reliable measurement instruments for core KM constructs (trust, socialisation, knowledge transfer) tailored to construction-specific contexts. These instruments should enable practitioners to assess progress and identify adjustment points in real-time, bridging the current theory–practice gap.

- 3.

- Design Science Research on Human–Technology Integration

Systematic development and rigorous testing of hybrid human–technology KM systems that integrate digital tools (AI, BIM, predictive analytics) with deliberate organisational mechanisms (mentoring, communities of practice, lessons-learned protocols). Design science approaches should explicitly address change management requirements and success criteria for adoption.

- 4.

- Comparative Case Study Research Across Contexts

Multi-country, multi-firm comparative case studies capturing how KM–PM–HRM integration unfolds differently across geographic regions, regulatory contexts, firm sizes, and project types. Such research should identify context-specific enablers and barriers to integration, moving beyond single-country or single-firm case studies.

- 5.

- Action Research Embedded in Construction Organisations

Participatory action research embedded within construction organisations implementing KM–PM–HRM integration. Such research should document implementation pathways, resource requirements, sequencing decisions, and organisational learning as integration unfolds, providing practitioner-accessible guidance for other organisations.

5. Limitations

This study presents several limitations that should be acknowledged.

First, the reliance on bibliometric and narrative synthesis methods, while offering a broad overview, may overlook nuanced qualitative insights that could be gained from empirical fieldwork or case studies.

Second, the research is limited by the availability and selection of literature predominantly published in English and sourced from major academic databases, which may exclude relevant studies from underrepresented regions. This limitation restricts the global cultural diversity represented in the findings, particularly from African, Latin American, and Middle Eastern contexts.

Third, while the study identifies significant themes in knowledge management (KM) and organisational resilience in construction, there remains a notable gap in the operationalisation of theoretical frameworks into practical applications, especially regarding the integration of emerging AI technologies with KM systems. Further empirical research is necessary to explore how these technologies can be effectively deployed to address skill shortages and workforce development.

Fourth, the cross-sectional nature of the reviewed literature limits insights into longitudinal impacts of KM practices on organisational resilience, underscoring the need for future studies employing longitudinal and cross-regional comparative designs to enhance empirical and cultural soundness.

The authors clarify that the purpose of this study is not to suggest new frameworks, models, or theories. The scope is limited to reviewing the current state of KM in construction, identifying best practices and gaps along with topics for future research.

Together, these research directions highlight the importance of overcoming operationalisation failures and enabling KM–PM–HRM integration.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Implications of Research Gaps

The five persistent gaps identified in this review—namely operationalisation of KM constructs, domain misalignment, technology–human integration, insufficient cross-regional research, and the theory–practice bridge—point to critical areas requiring empirical investigation and methodological development.

The analysis reveals that construction KM has evolved from repository-focused approaches toward integrated human-centred frameworks grounded in social mechanisms (trust-building, communities of practice, mentoring relationships). Yet significant operationalisation challenges remain. Core KM concepts such as trust, socialisation, and knowledge transfer lack precise, measurable definitions that practitioners can use to assess progress and adjust interventions.

The exponential growth in KM research post-2016—particularly studies linking KM to organisational resilience, digital transformation, and workforce sustainability—indicates increasing recognition of KM’s strategic importance. However, this growth has not been accompanied by equivalent advancement in integrating KM with PM and HRM systems at the operational level. The fragmentation of these domains remains a fundamental barrier to construction organisation’s capacity to anticipate, adapt to, and recover from disruptions.

Digital technologies, including artificial intelligence, BIM, and predictive analytics, have shown tangible advantages, such as a 40% reduction in knowledge retrieval time and advancements in workforce planning of 6 to 9 months; however, these benefits are contingent upon their integration with human-centred organisational processes. A key point is that the operationalisation gap in digital knowledge management is more about how organisations work than about technology itself. While technology helps people share knowledge, it cannot replace the social systems that keep knowledge within project environments.

Regional differences in KM research traditions, particularly China’s dominance in single-country publications compared to the UK, USA, and Australia, which have more balanced international collaboration, highlight the need for comparative frameworks. These frameworks could provide clarity on the benefits and disadvantages of regulatory systems, as well as organisational structures across different geographical and cultural settings.

6.2. Strategic Implications

For practitioners and policymakers, this review highlights the importance of addressing the five identified gaps. To ensure enduring performance in increasingly volatile and uncertain environments, it is essential for construction organisations to implement these actions. Systematic methods for retaining and transferring knowledge are crucial for improving workforce resilience. These efforts help to reduce the adverse effects of skill shortages and support effective operational continuity. Therefore, the integration of KM, PM, and HRM should not be viewed as a technical or administrative task, but as a strategic necessity.

At the project level, such an integrated approach facilitates the curation and distribution of specialised knowledge, thereby optimising resources and improving performance across projects. However, from an organisational perspective, a focus on knowledge governance, coupled with increased management awareness, strengthens resilience by facilitating prompt and effective responses to disruption. Furthermore, the review indicates that investment in digital technologies yields enduring value when complemented by organisational initiatives that promote knowledge transfer and retention.

Construction organisations seeking to build resilience must move beyond viewing KM as a repository function and instead embed it as a dynamic capability integrated across all major organisational systems. The evidence from this review indicates that such integration, while challenging, is achievable and yields concrete benefits for workforce sustainability, project performance, and organisational resilience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.J.C., F.O. and É.V.K.; Methodology, J.J.C., F.O. and É.V.K.; Formal analysis: J.J.C.; Investigation: J.J.C.; Data curation: J.J.C.; Writing—original draft preparation: J.J.C.; Writing—review and editing: J.J.C., F.O. and É.V.K.; Supervision: F.O. and É.V.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| BIM | Building Information Modelling |

| HRM | Human Resource Management |

| ISO | International Organisation for Standardisation |

| KM | Knowledge Management |

| MCPs | Multi-Country Publications |

| OADR | Old-Age Dependency Ratio |

| PM | Project Management |

| PMO | Project Management Office |

| SCPs | Single-Country Publications |

| SECI | Socialisation, Externalisation, Combination, Internalisation (knowledge creation model) |

Appendix A. Covidence Data

References

- Liu, Y.; Houwing, E.-J.; Hertogh, M.; Bakker, H. Project-based learning principles: Insights from the development of large infrastructure. Front. Eng. Manag. 2024, 11, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, A. Facilitating multidirectional knowledge flows in project-based organizations: The intermediary roles of project management office. Int. J. Syst. Innov. 2022, 7, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daghfous, A.; Amer, N.T.; Belkhodja, O.; Angell, L.C.; Zoubi, T. Managing knowledge loss: A systematic literature review and future research directions. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2023, 36, 1008–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchek, S. Organizational resilience: A capability-based conceptualization. Bus. Res. 2020, 13, 215–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Cruz, O. An essential definition of engineering to support engineering research in the twenty-first century. J. Philos. 2022, 10, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanyi, M. The Tacit Dimension, 2nd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Mirarchi, C. A spatio-temporal perspective to knowledge management in the construction sector. In Proceedings of the New Frontiers of Construction Management Workshop, Ravenna, Italy, 8–9 November 2018; Volume 9, pp. 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, C.; Ning, Y. Integrating interorganizational justice to facilitate tacit knowledge sharing in architectural and engineering design projects: A configurational approach. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2022, 29, 3480–3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Song, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, C. Intellectual Capital, Knowledge Sharing, and Innovation Performance: Evidence from the Chinese Construction Industry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. World Employment and Social Outlook; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://researchrepository.ilo.org/esploro/outputs/report/995343385502676 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Houten, G.; Russo, G. European Company Survey 2019: Workplace Practices Unlocking Employee Potential; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; Available online: https://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv:88233 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Hatoum, M.B.; Nassereddine, H. Becoming an Employer of Choice for Generation Z in the Construction Industry. Buildings 2025, 15, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceric, A.; Ivic, I. Construction labor and skill shortages in Croatia: Causes and response strategies. Organ. Technol. Manag. Constr. Int. J. 2020, 12, 2232–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juricic, B.B.; Galic, M.; Marenjak, S. Review of the Construction Labour Demand and Shortages in the EU. Buildings 2021, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adah, C.A.; Aghimien, D.O.; Oshodi, O. Work–life balance in the construction industry: A bibliometric and narrative review. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2023, 32, 38–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Meng, X. BIM-supported knowledge management: Potentials and expectations. J. Manag. Eng. 2021, 37, 04021032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Qi, K.; Chan, A.P.; Chiang, Y.H.; Siu, M.F.F. Manpower forecasting models in the construction industry: A systematic review. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2022, 29, 3137–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerezo-Narváez, A.; Pastor-Fernández, A.; Otero-Mateo, M.; Ballesteros-Pérez, P. The Influence of Knowledge on Managing Risk for the Success in Complex Construction Projects: The IPMA Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho, A.J.C.; Couto, J. Contribution to improvement of knowledge management in the construction industry - Stakeholders’ perspective on implementation in the largest construction companies. Cogent Eng. 2022, 9, 2132652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Huang, L.; Jiang, L.; Chen, J.; Chen, W.; He, Y. Fostering Knowledge Collaboration in Construction Projects: The Role of BIM Application. Buildings 2023, 13, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, S.M.F.; Naiding, Y.; Shah, S.K. Restraining knowledge leakage in collaborative projects through HRM. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2024, 54, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behme, F.; Becker, S. The New Knowledge Management: Mining the Collective Intelligence. Deloitte Insights. 2021. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/focus/technology-and-the-future-of-work/organizational-knowledge-management.html (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Arif, M.; Al Zubi, M.; Gupta, A.D.; Egbu, C.; Walton, R.O.; Islam, R. Knowledge sharing maturity model for Jordanian construction sector. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2017, 24, 170–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M.T.; Carvalho, M.M. Absorptive capacity activation triggers: Insights from learning in project epochs of a project-based organization. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2024, 42, 102637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.L.; Yepes, V.; Pellicer, E.; Cuéllar, A.J. Knowledge management in the construction industry: State of the art and trends in research. Rev. Constr. 2012, 11, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranckutė, R. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The titans of bibliographic information in today’s academic world. Publications 2021, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, A.; Kargina, M. A user-friendly method to merge Scopus and Web of Science data during bibliometric analysis. J. Mark. Anal. 2022, 10, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninkov, A.; Frank, J.R.; Maggio, L.A. Bibliometrics: Methods for studying academic publishing. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2022, 11, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passas, I. Bibliometric analysis: The main steps. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 1014–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dacre, N.; Eggleton, D.; Gkogkidis, V.; Cantone, B.; Gkogkidis, V. Dynamic Conditions for Project Success; Association for Project Management (APM): Buckinghamshire, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaechi, C.V.; Reda, A.; Beddu, S.B.; Bin Mohamed, D.; Syamsir, A.; Ja’E, I.A.; Ullah, S.; Deng, X.; Huang, B.; Wang, C.; et al. A systematic literature review on knowledge management for project risk management in construction. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 114, 114261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yepes, V.; López, S. Knowledge management in the construction industry: Current state of knowledge and future research. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2021, 27, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zungu, Z.; Laryea, S.; Nkado, R. A critical literature review on organizational resilience: Why current frameworks are insufficient for contracting firms in the construction industry. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2025, 25, 1847–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I. A Dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organ. Sci. 1994, 5, 14–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minbaeva, D.B. HRM practices affecting extrinsic and intrinsic motivation of knowledge receivers and their effect on intra-MNC knowledge transfer. Int. Bus. Rev. 2008, 17, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, R.S.; Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, C.A. Building and managing the transnational: The new organizational challenge. In Managing the Global Firm; Bartlett, C.A., Doz, Y., Hedlund, G., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1990; pp. 367–403. [Google Scholar]

- Birkinshaw, J. Entrepreneurship in multinational corporations: The characteristics of subsidiary initiatives. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 207–229. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3088128 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Stahl, G.K. Handbook of Research on International Human Resource Management, 2nd ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M. Economy and Society: Outline of Interpretive Sociology; Mohr Siebeck: Tübingen, Germany, 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Mainga, W. Examining project learning, project management competencies, and project efficiency in project-based firms (PBFs). Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2017, 10, 454–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, R.M.; Cambré, B.; Korlaar, L.; Raab, J. Managing the project learning paradox: A set-theoretic approach toward project knowledge transfer. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2011, 29, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowson, J.; Unterhitzenberger, C.; Bryde, D.J. Facilitating and improving learning in projects: Evidence from a lean approach. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2024, 42, 102559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Hong, Y. Navigating compliance complexity: Insights from the MOA framework in international construction. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2024, 32, 6068–6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, S.; Zhu, Q.; Hu, X.; Zhu, Z.; Skitmore, M. Migrant workers in the construction industry: A bibliometric and qualitative content analysis. Buildings 2025, 15, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Vidal, M.E.; Sanz-Valle, R.; Barba-Aragon, M.I. Repatriates and reverse knowledge transfer in MNCs. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 29, 1767–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirdöğen, G. Development of knowledge management risk framework for the construction industry. Buildings 2023, 13, 2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yu, H.; Deng, X. A systematic review of the evolution of the concept of resilience in the construction industry. Buildings 2024, 14, 2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, T.; Yang, J.; Zhang, F.; Lyu, C.; Deng, C. The role of task conflict in cooperative innovation projects: An organizational learning theory perspective. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2021, 39, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Toyama, R.; Konno, N. SECI, Ba and leadership: A unified model of dynamic knowledge creation. In Managing Industrial Knowledge: Creation, Transfer and Utilization; Nonaka, I., Teece, D.J., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 13–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.; Chen, S.; Deng, X.; Mahmoudi, A. Knowledge transfer among members within cross-cultural teams of international construction projects. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2023, 30, 1787–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumanarathna, N.; Duodu, B.; Rowlinson, S. Social capital, exploratory learning and exploitative learning in project-based firms: The mediating effect of collaborative environment. Learn. Organ. 2020, 27, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igoa-Iraola, E.; Díez, F. Procedures for transferring organizational knowledge during generational change: A systematic review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, S.M.F.; Yang, N.; Rehman, A.U.; Kanwal, F.; WangDu, F. Protecting organizational competitiveness from the hazards of knowledge leakage through HRM. Manag. Decis. 2021, 59, 2405–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, N.A.; Islam, Z.; Sumardi, W.A. Human resource management practices in creating a committed workforce for fostering knowledge transfer: A theoretical framework. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2023, 53, 663–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavez, I.; Gómez, H.; Laulié, L.; González, V.A. Project team resilience: The effect of group potency and interpersonal trust. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2021, 39, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; He, J. Critical factors affecting tacit-knowledge sharing within the integrated project team. J. Manag. Eng. 2015, 32, 04015045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minbaeva, D.B.; Pedersen, T.; Björkman, I.; Fey, C.F. A retrospective on: MNC knowledge transfer, subsidiary absorptive capacity, and HRM. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2014, 45, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakhan, A.A.; Nnaji, C.A.; Gambatese, J.A.; Simmons, D.R. Best practice strategies for workforce development and sustainability in construction. Pr. Period. Struct. Des. Constr. 2023, 28, 04022058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iao-Jörgensen, J. Antecedents to bounce forward: A case study tracing the resilience of inter-organisational projects in the face of disruptions. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2023, 41, 102440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferres, G.M.; Moehler, R.C. Running the codification gauntlet: Why intent alone cannot afford the codification of project learnings. Proj. Manag. J. 2024, 55, 406–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Brătianu, C. A critical analysis of Nonaka’s model of knowledge dynamics. Electron. J. Knowl. Manag. 2010, 8, 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Gourlay, S. Conceptualizing knowledge creation: A critique of Nonaka’s theory. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 1415–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaviria-Marin, M.; Merigó, J.M.; Baier-Fuentes, H. Knowledge management: A global examination based on bibliometric analysis. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 140, 194–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stampfl, R.; Prodinger, M.; Palkovits-Rauter, S. Reshaping Knowledge Flow: The Impact of Ecollaboration Platforms in It-Project Knowledge Transfer. Electron. J. Knowl. Manag. 2024, 22, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 9001; Quality Management Systems—Requirements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Demir, A.; Budur, T.; Omer, H.M.; Heshmati, A. Links between knowledge management and organisational sustainability: Does the ISO 9001 certification have an effect? Knowl. Manag. Res. Pr. 2023, 21, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 30401; Knowledge Management Systems—Requirements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Tabejamaat, S.; Ahmadi, H.; Barmayehvar, B. Boosting large-scale construction project risk management: Application of the impact of building information modeling, knowledge management, and sustainable practices for optimal productivity. Energy Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2284–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Succar, B.; Poirier, E. Lifecycle information transformation and exchange for delivering and managing digital and physical assets. Autom. Constr. 2020, 112, 103090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, K.; Cao, Y.; Wu, J. An exploratory study on the impact of cross-organizational control and knowledge sharing on project performance. Buildings 2023, 13, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbar, D.R.; Chang, T.; Deng, X.; Mahmoud, M.R.I. Implementing Effective Knowledge Management in International Construction Projects by Eliminating Knowledge Hiding. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2024, 150, 04024082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, K.; Durst, S. Knowledge management in the age of generative artificial intelligence–From SECI to GRAI. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Q.; Sumbal, M.S.; Lee, C.K.M. AI-driven knowledge management in megaprojects: The leadership factor. Eur. Conf. Knowl. Manag. 2025, 26, 1163–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, A.R. The impact of integrating artificial intelligence and Building information modeling (BIM) systems on the development of construction methodologies. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Eng. Arch. 2025, 16, 1537–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathoori, M.R. The Evolution of Workforce Analytics: From Historical Reporting to Predictive Decision-Making. Eur. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol. 2025, 13, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyisoglu, B.; Shahpari, A.; Talebi, M. Predictive Project Management in Construction: A Data-Driven Ap-proach to Project Scheduling and Resource Estimation Using Machine Learning; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshood, T.D.; Rotimi, F.E.; Rotimi, J.O. An integrated paradigm for managing efficient knowledge transfer: Towards a more comprehensive philosophy of transferring knowledge in the construction industry. Constr. Econ. Build. 2022, 22, 65–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokes, T.J. Mechanisms of knowledge transfer. Think. Reason. 2009, 15, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favoretto, C.; de Carvalho, M.M. An analysis of the relationship between knowledge management and project performance: Literature review and conceptual framework. Gestão Produção 2021, 28, e4888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Ding, X.-H. The Effect of Coordination Capability on Knowledge Transfer: The Moderating Role of Learning Orientation. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 5953–5964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, P.; Robinson, H.; Al-Ghassani, A.; Anumba, C. Knowledge Management in UK Construction: Strategies, Resources and Barriers. Proj. Manag. J. 2004, 35, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boamah, F.A.; Zhang, J.; Shehzad, M.U.; Ahmad, M. The mediating role of social dynamics in the influence of absorptive capacity and tacit knowledge sharing on project performance. Bus. Process. Manag. J. 2023, 29, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senaratne, S.; Rodrigo, M.N.N.; Jin, X.; Perera, S. Current trends and future directions in knowledge management in construction research using social network analysis. Buildings 2021, 11, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiege, J.R.A.; Backhouse, J. Knowledge management in local governments in developing countries: A systematic literature review. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2023, 53, 450–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brozovsky, J.; Labonnote, N.; Vigren, O. Digital technologies in architecture, engineering, and construction. Autom. Constr. 2024, 158, 105212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassandro, J.; Mirarchi, C.; Gholamzadehmir, M.; Pavan, A. Advancements and prospects in building information modeling (BIM) for construction: A review. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2024, 32, 6006–6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz-Serra, P.; Edwards, P. Addressing the knowledge management “nightmare” for construction companies. Constr. Innov. 2020, 21, 300–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlato, M.; Binni, L.; Durmus, D.; Gatto, C.; Giusti, L.; Massari, A.; Toldo, B.M.; Cascone, S.; Mirarchi, C. Digital Platforms for the Built Environment: A Systematic Review Across Sectors and Scales. Buildings 2025, 15, 2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, V.A.; Hamzeh, F.; Alarcón, L.F. Lean Construction 4.0: Driving a Digital Revolution of Production Management in the AEC Industry; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, L.M. Knowledge management readiness of government institutions of developing countries in Asia: A systematic literature review. SSRN 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepple, D.G.; Dore-Okuiomse, M.M. An enabler framework for developing knowledge management practices: Perspectives from Nigeria. S. Afr. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 25, 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durst, S.; Foli, S.; Edvardsson, I.R. A systematic literature review on knowledge management in SMEs: Current trends and future directions. Manag. Rev. Q. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillmann, J.; Guenther, E. Organizational Resilience: A Valuable Construct for Management Research? Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 7–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Ma, R. Antecedents of knowledge hiding and their impact on organizational performance. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 796976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekera, V.S.; Chong, S.C. Knowledge management critical success factors and project management performance outcomes in major construction organisations in Sri Lanka. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2018, 48, 537–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokede, O.; Ahiaga-Dagbui, D.; Morrison, J. Praxis of knowledge-management and trust-based collaborative relationships in project delivery: Mediating role of a project facilitator. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2022, 15, 595–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Ren, X.; Anumba, C.J. Analysis of Knowledge-Transfer Mechanisms in Construction Project Cooperation Networks. J. Manag. Eng. 2019, 35, 04018061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minbaeva, D.B.; Mäkelä, K.; Rabbiosi, L. Linking HRM and knowledge transfer via individual-level mechanisms. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 51, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.