Abstract

Here, we introduce novel pregelatinized starch-modified silica gels for Portland cement enhancement. The modified SiO2 gels demonstrate superior mechanical properties compared to pure silica, with optimal starch modification increasing the modulus by 244.8%. Structural characterization reveals that starch alters Si-O bond configurations without covalent bond formation. Applied to Portland cement, the modified gels significantly enhance compressive strength through method-dependent mechanisms. Casting applications show measurable strength improvements, while pressing methods achieve a 42.3% compressive strength increase with superior packing efficiency under confined conditions. The enhancement primarily stems from accelerated C3S hydration facilitated by the modified silica gels. These findings establish an innovative approach for high-performance cement materials via organic–inorganic composite modification, providing practical formulation guidance across diverse application scenarios.

1. Introduction

Theoretically, incorporating synthesized SiO2 into cement can improve both the early strength and the extent of cement hydration. Researchers have investigated the integration of nano-SiO2 into cementitious materials to enhance the strength of cement [1,2]. For application, dried powder nano-SiO2 is beneficial for reducing the complexity of construction in cement-based materials such as aerogel foamed cement and self-leveling materials [3,4]. However, current technological limitations necessitate either freeze-drying or the direct use of SiO2 suspensions to obtain nano-SiO2, which restricts its practical application as a cement admixture. Thus, the development of cost-effective dried SiO2-based cement admixtures represents an advancement in this field.

The nucleation effect of SiO2 is attributed to the presence of silicon–oxygen tetrahedra on its surface. During cement hydration, the primary hydration product formed is calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) [5,6]. The surface of C-S-H exhibits silicon–oxygen tetrahedral chains that are structurally analogous to those in SiO2, particularly the branched Q3 silicon–oxygen tetrahedral chain, which is present on both SiO2 and C-S-H surfaces. Theoretically, during cement hydration, the monomers Q0 from C3S and C2S dissolve in water and subsequently polymerize into Q1, Q2, and Q3 structures [7]. For nano-SiO2, due to surface defects and energy imbalance, the dissolved Q0 tends to preferentially polymerize on the SiO2 surface. Calcium ions and water molecules facilitate the formation of C-S-H on the SiO2 surface through electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding. This mechanism forms the theoretical foundation for nano-SiO2 as a cement admixture. In contrast, micro-SiO2 undergoes a secondary hydration reaction with CH in the alkaline environment of cement paste, contributing to the formation of a denser cement matrix and mitigating alkali–aggregate reactions during concrete preparation [8]. And some micro-SiO2 particles could be actively dispersed into nano-SiO2 during cement hydration; this would simultaneously regulate early hydration and consume CH [8,9,10]. However, the development of such particle preparation methods remains challenging.

The technology of organic–inorganic hybrid nanomaterials provides a potential pathway for achieving micro-SiO2 particles capable of dispersing into nanoparticles. The loss of water molecules during drying is a critical factor driving nanoparticle agglomeration and microparticle formation. To address this issue, modifying the surface structure of nanoparticles or utilizing the steric hindrance effect of organic molecules can effectively inhibit nanoparticle agglomeration. Based on this principle, Zhu et al. successfully synthesized an organic binder using pregelatinized starch, which was incorporated into the C-S-H aggregate structure [11]. Given the structural similarity between SiO2 and C-S-H in terms of silicate chains and spherical morphology, pregelatinized starch can serve as a binder to guide the organic binding of SiO2 structures. And due to the disruption of hydrogen bonds between pregelatinized starch and SiO2, as pregelatinized starch is water-soluble, the micro-sized pregelatinized starch-bound SiO2 structure dissociates into dispersed nano-SiO2 particles in aqueous solution. That is, while Zhu et al. [11] demonstrated that pregelatinized starch can form hydrogen bonds with silicate structures, current research predominantly focuses on conventional nano-SiO2 particles, leaving the modification of SiO2 gel systems unexplored. The unique three-dimensional network structure of SiO2 gels differs fundamentally from discrete nanoparticles, and their interaction mechanisms with starch-based biopolymers remain systematically uninvestigated. Interestingly, pregelatinized starch has historically been used in traditional Chinese lime mortar to construct pregelatinized starch-binding calcium carbonate structures; its effectiveness in nanoparticle agglomeration inhibition has been demonstrated over thousands of years [11,12,13]. This means that in modern cement systems, pregelatinized starch-binding nano-SiO2 particle structures may offer some benefits involving agglomeration, nucleation, and mechanical properties. Despite this, further experimental research is required to explore the construction of new SiO2-based additives.

Among them, the SiO2 gel is a hydrated phase primarily composed of a three-dimensional network structure with nanoscale pores [14,15,16]. In contrast to traditional nano-SiO2, it forms an interconnected framework, whereas nano-SiO2 particles exist as discrete entities. In terms of surface chemical properties, SiO2 gel is abundant in silanol groups (–SiOH) and possesses a greater number of active sites, while the surface hydroxylation causes nano-SiO2 to be more susceptible to agglomeration. Theoretically, the effects of SiO2 gel should manifest as a novel phenomenon in cement performance. However, current research on the structural regulation of SiO2 gel and its effect on cement properties remains limited.

This research focuses on the development of pregelatinized starch-modified SiO2 gels through the combination of organic and inorganic components. A comprehensive investigation was carried out to characterize the structural features of the starch-integrated silica gels, along with their influence on the hydration process and mechanical properties of Portland cement produced via both casting and compression techniques. Initially, the structural properties of the pregelatinized starch-bound SiO2 gels were examined. X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and thermogravimetric analysis (TG-DTG) were applied to investigate phase transitions. The chemical composition of the composites was further analyzed using FTIR and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR). Additionally, dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) was conducted to assess the mechanical behavior of the gels. Subsequently, the impact of the modified silica gels on the strength development of cement fabricated by casting and compression methods was evaluated. Finally, the underlying mechanism responsible for the enhanced strength was explored. These results offer valuable guidance for the formulation and utilization of high-performance cement-based materials.

2. Experimental

2.1. Material and Sample Preparation

The SiO2 gel was prepared through a sol–gel process by combining tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS), DL-tartaric acid, anhydrous ethanol, and distilled water. The mixture was stirred at 800 r/min for 20 min at 50 °C until a transparent solution was obtained. The molar ratio of the components was maintained as TEOS:H2O:DL—tartaric acid/anhydrous ethanol = 1:2:0.02:1. Following this, pregelatinized starch was introduced into the mixture and continuously stirred at the same temperature. A calcium nitrate solution was then slowly added drop by drop to produce solution A. This solution was gradually poured into 250 mL of NaOH solution (pH adjusted to 8) over a 2 min period under continuous stirring, resulting in the formation of a white precipitate. The precipitate was then subjected to curing at 60 °C for 24 h with constant stirring. For sample characterization, the pregelatinized starch-modified silica gels were rinsed twice with 1000 mL of deionized water, placed in a drying oven, and maintained at 40 °C for 72 h. Four different samples were prepared with varying starch contents by weight: 0%, 0.1%, 0.3%, and 0.5%, labeled as PS00, STS01, STS03, and STS05, respectively. To evaluate mechanical performance, the starch-bound SiO2 microparticles were incorporated into cement at dosages of 0.2%, 0.4%, 0.6%, 0.8%, and 1.0% for the casting method, and 2%, 4%, 6%, 8%, and 10% for the pressure method. After uniform mixing, cubic specimens measuring 40 mm × 40 mm × 40 mm and 40 mm × 40 mm × 120 mm were fabricated.

2.2. Structural Characterization

2.2.1. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis (XRD)

The dried precipitates were analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD) with a Rigaku-D/max 2550VB3 diffractometer (Japan). The instrument was equipped with a graphite-monochromatized Cu Kα radiation source (λ = 1.541 Å) and operated at 40 kV and 100 mA. The XRD patterns were recorded over a 2θ range of 5° to 70° at a scanning rate of 5° per minute.

2.2.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

To investigate the chemical bonds and nanostructure of pregelatinized starch-modified SiO2 gel, spectroscopic techniques including FTIR and Raman spectroscopy were utilized. FTIR absorption spectra were recorded using a Bruker Tensor 27 instrument (Germany) via the KBr pellet method.

2.2.3. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (NMR)

The MAS NMR experiments were conducted using an Agilent 600 DD2 spectrometer (magnetic field strength of 14.1 T, USA). A resonance frequency of 119.23 MHz was used for 29Si. The dipole decoupling magic-angle spinning (DD/MAS) technique was employed with high-power 1H decoupling. The 29Si NMR cross-polarization spectra were recorded at room temperature using a 4 mm probe spinning at a rate of 15 kHz (4 μs 90° pulses). Si CPMAS (Cross Polarization Magic Angle Spinning) experiments were carried out with a delay time of 3 s and a contact time of 1 ms, and a total of 5000 scans were performed. The Si signal of tetramethylsilane (TMS) at 0 ppm served as a reference for determination of 29Si chemical shifting. The deconvolution process involved the assignment of resonances to individual species using the Gaussian function.

2.2.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TG–DTG)

TG–DTG was performed using a NETZSCH STA 449F3 system (Germany) under a nitrogen atmosphere, for which the samples were heated from 30 to 900 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min.

2.2.5. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

Samples of pregelatinized maize starch/amorphous silica were measured thrice at room temperature via DMA under 3-point bending. The instrument was calibrated according to the NETZSCH procedure.

2.2.6. Heat of Hydration

The hydration heat of the modified silica gels was measured in accordance with the ASTM C170 standard specifications. Raw materials were removed, mixed with liquid, and stirred to form a slurry. The resulting samples were then placed in an isothermal calorimeter and tested over 60 h, with the hydration heat flow test used to obtain the accumulative hydration heat. The degree of hydration is determined using the following equation:

where α is the reaction degree, Q(t) is the heat released by time t, and Qmax represents the maximum total heat release. The Arrhenius equation uses the concept of activation energy (Ea) to define the sensitivity of a particular reaction to the inorganic phase components.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Pregelatinized Starch-Binding SiO2 Gels

3.1.1. Phase Analysis

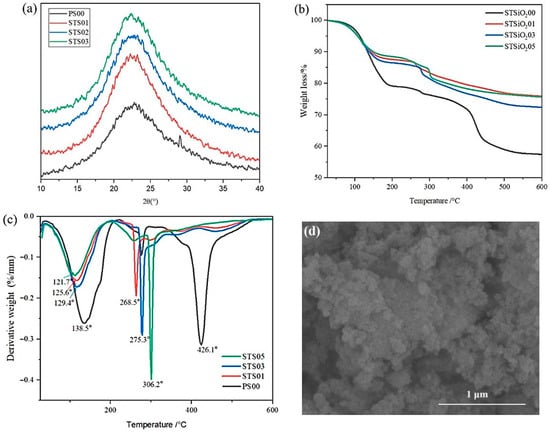

Figure 1a presents the XRD patterns of pregelatinized starch-modified silica gels with varying starch concentrations. As observed, all samples displayed characteristic amorphous SiO2 diffraction peaks between 15° and 30°. However, the intensity and width of these peaks changed to varying extents upon starch incorporation. Previous studies have indicated that pregelatinized starch undergoes a retrogradation process over time, during which starch chains reorganize and form crystalline structures [17,18,19]. In Figure 1b,c, the thermogravimetric analysis results show weight losses of 21.1%, 16.3%, 17.4%, and 14.8% for PS00, STS01, STS03, and STS05 samples, respectively, within the temperature range of 100–220 °C. This suggests that significant water loss reflects the presence of a silica gel framework. When 0.1% pregelatinized starch was introduced, the main DTG peak shifted from 138.5 °C to 129.4 °C, mainly due to the accelerated evaporation of bound water in SiO2. A distinct weight loss peak around 300 °C for the STS01, STS03, and STS05 samples corresponds to the complete thermal decomposition of starch, which aligns with the typical degradation temperature of starch components. The weight loss rate begins to decline at approximately 500 °C, attributed to the condensation of silanol (Si–OH) groups, leading to a flattened curve. As shown in Figure 1d, the typical morphology of dried modified SiO2 gels consists of nanoparticle aggregates, with pregelatinized starch integrated into the structure. The starch is distributed between the modified SiO2 particles, participating in the formation of agglomerates or filling the pores within the gel matrix. Collectively, these analytical findings confirm the successful synthesis of hydrated SiO2 gels.

Figure 1.

Phase analysis of pregelatinized starch-modified SiO2 gels: (a) XRD, (b) TG, (c) DTG, (d) SEM.

3.1.2. FTIR and NMR Analysis

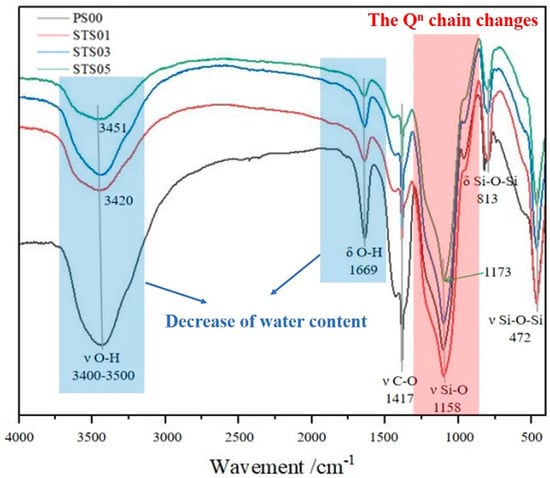

Figure 2 displays the FTIR spectra of silica gels modified with pregelatinized starch. Distinct absorption bands near 813 cm−1 and 1158 cm−1 are associated with Si–O–Si bending vibrations and Si–O stretching vibrations, respectively. The peak observed at approximately 472 cm−1 is linked to the internal deformation of [SiO4]2− tetrahedra [20,21]. Analysis of the spectra also identified a characteristic bending vibration of adsorbed water molecules at 1669 cm−1 [22,23]. Moreover, the hydroxyl group absorption bands shifted from 3420 cm−1 to 3436 cm−1 and 3451 cm−1 after the addition of pregelatinized starch [23]. These shifts toward lower wavenumbers, compared to the unmodified samples, suggest the formation of hydrogen bonds between the starch and the silica gel surface. Additionally, the Si–O absorption band moved from 965 cm−1 to 1158 cm−1, indicating structural changes within the SiO2 network. These observations indicate that the starch molecules did not form covalent linkages with the silica surface.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of pregelatinized starch-modified SiO2 gels.

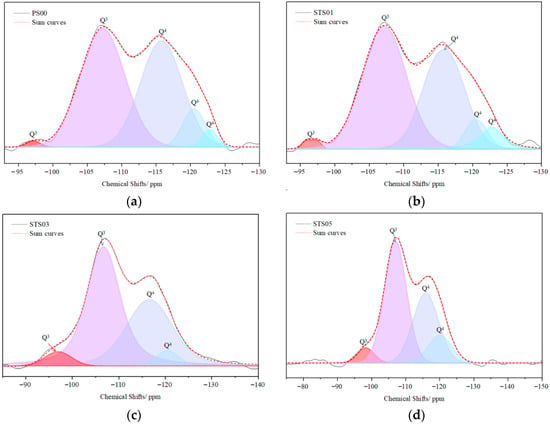

NMR spectroscopy was employed to assess quantitative changes in the amorphous SiO2 network. Figure 3 displays the 29Si NMR spectra and corresponding deconvolution data for silica gels modified with pregelatinized starch, illustrating how the 29Si NMR profiles evolve with increasing starch content. These findings suggest that pregelatinized starch influences the distribution of Qn species within the modified SiO2 matrix. The chemical shifts observed in the spectra correspond to various silicon–oxygen tetrahedral configurations, which are determined by the local Si atom environment. The Qn notation is used to classify these tetrahedral units, where n (ranging from 1 to 4) indicates the number of bridging oxygen atoms shared with neighboring tetrahedra. According to prior research, Q3 and Q4 signals typically appear in the ranges of −90 to −106 ppm and −98 to −129 ppm, respectively [24,25,26,27]. However, in this study, the Q3 peaks were observed at slightly lower values (−105 to −110 ppm) [28], which may be attributed to variations in the synthesis conditions affecting Q3 formation. Table 1 provides a summary of the inverse convolution results, which were analyzed to further explore this behavior. Following starch modification, alterations in the Q3/Q4 ratio were detected, indicating that pregelatinized starch impacts the silicate chain structure. As the organic phase content increased in the modified gels, the Q4 peak at −123.6 ppm vanished, highlighting the ability of pregelatinized starch to alter the gel’s chemical framework. The overall analysis confirms that the modified SiO2 particles maintain an amorphous nature and retain a considerable amount of water. Structural investigations further reveal that the silicate chains are affected by the concentration of pregelatinized starch. As a result, three distinct modified SiO2 samples with unique structural features were produced: STS01, STS03, and STS05. In the NMR test, a new finding was that the content of silicate chain Q4 in modified SiO2 decreased. The oxygen of the siloxane tetrahedron Q4 is all bridging oxygen atoms. When Q4 transforms into other types of siloxane tetrahedrons, the bridging oxygen atoms transform into non-bridging oxygen atoms. Non-bridging oxygen has a static effect on cations due to its negative charge. In general, during the cement hydration process, Ca2+ ions will first dissolve and gradually reach a balanced concentration. This indicates that if Ca2+ ions are consumed in the early stage of hydration, it will accelerate the cement hydration.

Figure 3.

29Si NMR and deconvolution analysis of pregelatinized starch-modified SiO2 gels: (a) PS00, (b) STS01, (c) STS03, and (d) STS05.

Table 1.

Chemical shifts and contents of the Qn species.

3.1.3. Mechanical Properties of Pregelatinized Starch-Binding SiO2 Gel Structure

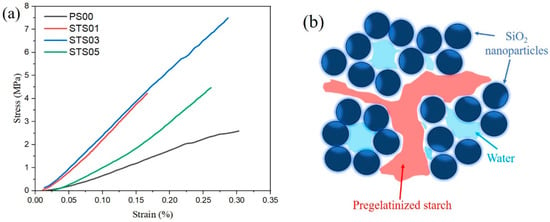

Figure 4 displays the variation in stress as strain increases for samples with different starch contents. The modulus of elasticity was used to evaluate the rigidity of the silica gel samples, both before and after modification with various concentrations of pregelatinized starch. According to Figure 4a, incorporating 0.1% pregelatinized starch resulted in a 243.9% enhancement in the modulus of elasticity when compared to the unmodified sample, while the relative strain dropped to 51.6% of that measured in the original sample. With 0.3% pregelatinized starch, the modulus increased even further by 244.8%, although accompanied by a 3.2% decrease in elongation. However, at a starch concentration of 0.5%, the modulus was lower than the values obtained at 0.1% and 0.3%, yet still higher than that of the unmodified silica gel. This decline could be due to an overabundance of starch molecules in the modified SiO2 gels, leading to clustering and compromising the material’s homogeneity. In Figure 4b, based on the test results mentioned above, the pregelatinized starch-binding SiO2 gel structure was proposed. Pregelatinized starch, along with water molecules, occupies the pore spaces within the gels, with the starch additionally acting as a binding agent that connects the gel particles. This hybrid organic–inorganic network is primarily responsible for the observed enhancement in modulus

Figure 4.

Mechanical properties of pregelatinized starch-modified SiO2 gel structure: (a) stress–strain curves of silica gels, (b) pregelatinized starch-binding SiO2 gel structure.

3.2. Effect of Modified SiO2 Gels on the Mechanical Properties of Portland Cement

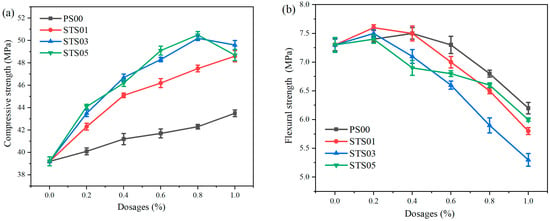

As shown above, the modified SiO2 gels exhibit superior mechanical properties at the micron scale compared to pure SiO2 particles, which indicates that it plays distinct roles in different manufacturing processes such as pouring and pressing. For the pouring process, Figure 5 demonstrates the effect of modified SiO2 gels on the mechanical strength of common Portland cement samples. In Figure 5, all the modified SiO2 gels enhance the compressive strengths while decreasing flexural strength. Compared to the sample without additives, when the dosages of STS05 are 0.8%, the compressive strengths increase by 28.8%, while the flexural strengths decrease by 10.6%. It is important to highlight that the SiO2 utilized for theoretical evaluation in this study is in the form of micro-sized powders, which is larger than conventional nano-sized nucleating admixtures. This means the raw materials for preparing SiO2 gels can be substituted with solid wastes rich in C-S-H phases. For example, during carbonization, steel slag and similar solid wastes often generate silica gel and calcium carbonate. That is, leveraging the fundamental theoretical data obtained herein, the economic feasibility of developing an affordable method for acidification-based preparation of recycled cement micro-powder is underscored. Compared with pure SiO2 gels, the modified SiO2 gels exhibit a superior ability to enhance compressive strength while incurring a relatively smaller reduction in flexural strength. When the dosages of STS05 are 0.8%, the compressive strength and flexural strength are 50.5 MPa and 6.6 MPa, respectively. And at such dosages, the compressive strength and flexural strength of PS00 are 42.3 MPa and 6.8 MPa, respectively.

Figure 5.

Effect of pregelatinized starch-modified SiO2 gels on the mechanical properties common to Portland cement samples for pouring: (a) compressive strength, (b) flexural strength.

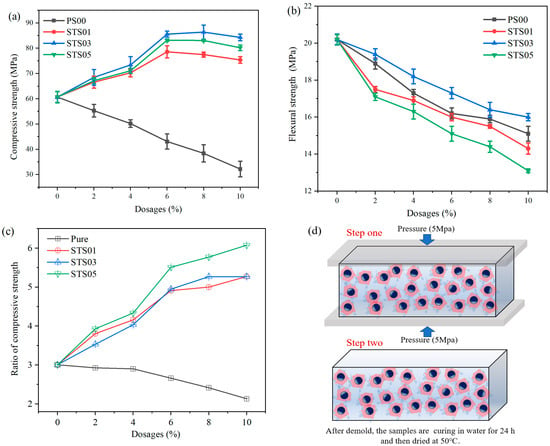

Figure 6a,b demonstrate the influence of modified SiO2 gels with varying dosages of pregelatinized starch on the mechanical strength of macro-defect-free (MDF) Portland cement. In Figure 6a,b, the modified SiO2 gels enhance the compressive but decrease the flexural strength of MDF samples. Compared to the sample without additives, when the adding dosage is 8%, the STS03 sample shows an increase in compressive strength of 42.3%, and a decrease in flexural strength of 6%. In Figure 6c, compared to the sample without additives, the STS01 achieves the highest ratio of compressive strength of 2.3, which is caused by a rapid decrease in flexural strength. It is noteworthy that, for STS03, although the ratio of compressive strength is 1.37, the flexural strength exhibits a slight decrease. In addition, compared to the sample without additives, the optimal pressure-to-bending ratio of pure SiO2, STS01, STS03, and STS05 increased by −29.0%, 75.4%, 75.3%, and 102.2%, respectively. That is, although the modified SiO2 gels possess inherent toughness, their incorporation into MDF results in a deterioration in toughness. This behavior is markedly different from the effect of adding flexible fibers to cement. The mechanism of action and heat of hydration of tricalcium silicate (C3S) modification will be discussed in the following text.

Figure 6.

Effect of pregelatinized starch-modified SiO2 gels on the mechanical properties of MDF cement: (a) compressive strength, (b) flexural strength, (c) ratio of compressive strength, and (d) MDF preparation process.

4. Discussion

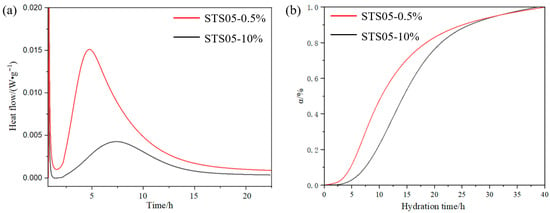

The aforementioned findings indicate that all modified SiO2 gels exhibit a compressive strength-enhancing effect. However, the magnitude of this reinforcement varies depending on the amount of pregelatinized starch added, which may be attributed to differences in the content of starch involved in inter-particle bonding. Unlike the hydration conditions in MDF cement, where water is limited, the pouring process involves an abundant supply of water. Under such conditions, the pregelatinized starch within the modified SiO2 gels will absorb water and swell, leading to the disruption of hydrogen bonds between the starch and the SiO2 gels by water molecules. As a result, the SiO2 gel powder, which was previously bound together by pregelatinized starch, undergoes depolymerization and disperses into the aqueous solution. This process may reduce the effective size of the modified SiO2 gels that interact with the cement hydration products, and then change the hydration process. During the early stage of cement hydration, the reaction between C3S and water constitutes the primary source of strength development [29,30,31]. To better evaluate the impact of modified SiO2 gels on early hydration under conditions of abundant water, two dosage levels—high and low—were selected for hydration heat testing. In Figure 7, the induction period of the high-dosage-modified SiO2 gels is shorter, indicating that these gels exert an early nucleation effect. Compared with the low-dosage samples, the high-dosage samples exhibit higher early heat release and hydration degree within the first 10 h. This suggests that the enhanced mechanical reinforcement provided by modified SiO2 gels may be attributed to their promoting effect on cement hydration.

Figure 7.

Effect pregelatinized starch-modified SiO2 gels (STS05) on the hydration process of C3S: (a) heat flow, (b) hydration degree.

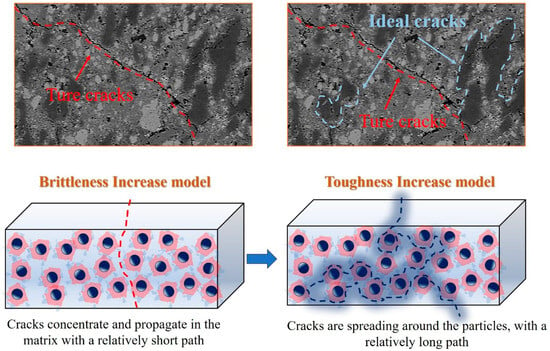

The preparation method of MDF cement involves the pressing technique, which effectively reduces internal porosity, resulting in a denser microstructure and consequently enhanced compressive strength. However, the reduced porosity inherently renders the material highly brittle. The experiment data have demonstrated that when SiO2 gels are employed as fillers in MDF cement, compressive strength is improved, but flexural strength is concurrently diminished. This suggests that SiO2 gels are unable to address the challenge of simultaneously enhancing both compressive and flexural strength. Although the modification of SiO2 gels with pregelatinized starch increases their intrinsic toughness, the contribution of modified SiO2 gels to overall toughness is significantly lower than that of their unmodified counterparts. It is hypothesized that the pores within the modified SiO2 gels are largely occupied by pregelatinized starch. Under confined spatial conditions, water molecules are unable to interfere with the spatial interaction between pregelatinized starch and SiO2 gels. The toughness enhancement provided by this compact organic–inorganic particle structure is outweighed by its limited capacity to absorb crack propagation energy. Consequently, the brittleness of MDF cement containing SiO2 gels increases, which involving a mechanism fundamentally distinct from the crack energy absorption behavior of fibers. Nevertheless, the STS03 sample achieves a 42.3% increase in compressive strength with only a 6% reduction in flexural strength. And under restricted space conditions, the hydration process of cement undergoes substantial changes, with high-density (HD) C-S-H [31] serving as the primary binding phase, forming a high mechanical structure. The observed increase in compressive strength upon the incorporation of modified SiO2 gels indicates a strong interfacial interaction between the gels and HD C-S-H. This compatibility may be attributed to the fact that both materials predominantly feature a Q3 silicate chain structure. Compared to the classic casting method, the MDF method results in fewer pores and a more brittle structure. In Figure 8, for the increased brittleness model, cracks do not propagate through the modified SiO2 gels; instead, their presence leads to crack concentration and expansion primarily within the cement matrix. For the increased toughness model, if crack propagation can be directed along the surface of the modified particles, thereby increasing the crack path length, the material’s toughness can be improved. Therefore, exploring novel organic compounds represents a promising and feasible strategy for achieving further objectives. In addition, the limitation of these works on MDF lies in the fact that when the method is applied, the suppression will lead to an increase in density, thereby restricting the scope of application.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of the brittleness increase model and the toughness increase model.

5. Conclusions

A new type of pregelatinized starch-modified silica gel was synthesized and incorporated into Portland cement. The nanostructure and mechanical properties of the modified silica gels, as well as their influence on cement strength, were thoroughly evaluated.

The introduction of pregelatinized starch altered the chemical composition of the silica gels. This modification was primarily attributed to hydrogen bonding formed between the pregelatinized starch and the silica gel surface. The presence of pregelatinized starch led to changes in the microchemical structure of the silica gels, as indicated by the variation in the Q3 to Q4 ratio. The modulus of the modified silica gel increased by 243.9% compared to the unmodified sample, although the relative strain was reduced to 51.6% of the original. When 0.3% pregelatinized starch was applied, the modulus increased by 244.8%, while the strain decreased by 3.2%. In the context of Portland cement application, the modified SiO2 gels improved compressive strength. For the pouring method, adding 0.8% of 0.5% pregelatinized starch-modified SiO2 gels resulted in a 28-day compressive strength of 50.5 MPa and a flexural strength of 6.6 MPa. For the pressing method, incorporating 8% of 0.3% pregelatinized starch-modified SiO2 gels increased compressive strength by 42.3%, while flexural strength decreased by 6%. This improvement is due to the modified SiO2 gels accelerating the early hydration of C3S. The main reason for the inability to simultaneously enhance flexural strength and compressive strength is that the cracks do not pass through the SiO2 gels. And the originality of the topic can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- All modified SiO2 gels exhibit compressive strength enhancement, with the magnitude positively correlated with the pregelatinized starch content.

- (2)

- High-dose-modified SiO2 gels significantly shorten the induction period of cement hydration, demonstrating an early nucleation effect, and show higher heat release and hydration degree within the first 10 h compared to low-dose samples, confirming their role in accelerating early hydration kinetics for performance optimization.

- (3)

- Modified SiO2 gels enhance mechanical properties by promoting cement hydration, offering a new approach for cement-based material modification, but MDF technology faces practical limitations due to density increase, requiring formulation optimization for broader application; future research should focus on balancing enhancement effects with density control.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S. and J.L.; methodology, Y.S.; formal analysis, Y.S. and J.L.; investigation, Y.S.; resources, J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.S.; writing—review and editing Y.S. and J.L.; funding acquisition Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work received financial support from the Science and Technology Research Project of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of Henan Province (NO. HNJS-2024-K13).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Maoquan Li for his guidance in microscopic testing and image drawing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hamed, Y.R.; Elshikh, M.M.Y.; Elshami, A.A.; Matthana, M.H.S.; Youssf, O. Mechanical properties of fly ash and silica fume based geopolymer concrete made with magnetized water activator. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkitasamy, V.; Santhanam, M.; Rao, B.P.C.; Balakrishnan, S.; Kumar, A. Mechanical and durability properties of structural grade heavy weight concrete with fly ash and slag. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 145, 105362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.; Liu, K.; Wang, L.; Zeng, H.; Hu, Q. Influence and analysis of different admixtures on the performance of nano-SiO2 aerogel foamed cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 459, 139701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbulut, Z.F.; Guler, S. Enhancing the resilience of cement mortar: Investigating Nano-SiO2 size and hybrid fiber effects on sulfuric acid resistance. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wu, K.; Wang, Z.; Xu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Geert, D. New insights of ordered packing bricks-like structure in 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane modified calcium silicate hydrate systems. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 106, 112684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.F.W. Proposed structure for calcium silicate hydrate gel. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1986, 69, 464–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, L.; Xu, L.; Wu, K. Time-varying structure evolution and mechanism analysis of alite particles hydrated in restricted space. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 341, 127829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Shen, Y.; Liu, J.; Fan, Y. Analysis of flexural fatigue damage and micro-mechanisms of nano-SiO2 modified recycled aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 487, 142004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Guan, S. Influence of nano-SiO2 and nano-TiO2 on early hydration process of cement: Hydration rate, hydration products microstructure, calcium ion solubility, and diffusion ability. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 491, 142629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, P.; Shan, Q.; Wu, K. Synthesis and characterization of pregelatinized starch–modified C-S-H: Inspired by the historic binders. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 354, 129114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moropoulou, A.; Bakolas, A.; Anagnostopoulou, S. Composite materials in ancient structures. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2005, 27, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, B.; Ma, Q. Study of sticky rice-lime mortar technology for the restoration of historical masonry construction. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baronio, G.; Binda, L.; Lombardini, N. The role of brick pebbles and dust in conglomerates based on hydrated lime and crushed bricks. Constr. Build. Mater. 1997, 11, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, W.; Zhu, Z.; Pu, S.; Li, R.Y.M. Interfacial properties and interaction of calcium-based geopolymer gels-SiO2 aggregate based on molecular dynamics simulations. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2025, 665, 123607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Li, H.; Yang, J.; Li, D. Fabrication of PI/SiO2 composite aerogels via an in-situ co-gel strategy for integrated thermal and acoustic insulation. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2026, 245, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matignon, A.; Tecante, A. Starch retrogradation: From starch components to cereal products. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 68, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zeng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, X.; Tian, Y.; Zheng, B. The effects of ultra-high pressure on the structural, rheological and retrogradation properties of lotus seed starch. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 44, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Feng, P.; Cai, Y.; Yu, X.; Yu, C.; Ran, Q. Carbonation behavior of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H): Its potential for CO2 capture. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 134243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Shi, H.; Qian, B.; Xu, Z.; Li, W.; Shen, X. Effects of synthetic C-S-H/PCE nanocomposites on early cement hydration. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 140, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafari, E.; Costa, H.; Júlio, E.; Portugal, A.; Durães, L. The effect of nanosilica addition on flowability, strength and transport properties of ultra high performance concrete. Mater. Des. 2014, 59, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, A.; Riahi, S. Microstructural, thermal, physical and mechanical behavior of the self compacting concrete containing SiO2 nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 527, 7663–7672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapeluszna, E.; Kotwica, Ł.; Różycka, A.; Gołek, Ł. Incorporation of Al in C-A-S-H gels with various Ca/Si and Al/Si ratio: Microstructural and structural characteristics with DTA/TG, XRD, FTIR and TEM analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 155, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Pan, F.; Wu, K. Synthesis and structure of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) modified by hydroxyl-terminated polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS). Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 267, 120731. [Google Scholar]

- Jamsheer, A.F.; Kupwade-Patil, K.; Büyüköztürk, O.; Bumajdad, A. Analysis of engineered cement paste using silica nanoparticles and metakaolin using 29Si NMR, water adsorption and synchrotron X-ray Diffraction. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 180, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Pan, F.; Wu, K. Insight into the local C-S-H structure and its evolution mechanism controlled by curing regime and Ca/Si ratio. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 333, 127388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbig, H.; Köhler, F.H.; Schieϐl, P. Quantitative 29Si MAS NMR spectroscopy of cement and silica fume containing paramagnetic impurities. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 326–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, S.L.; Kocaba, V.; Le Saoût, G.; Jakobsen, H.J.; Scrivener, K.L.; Skibsted, J. Improved quantification of alite and belite in anhydrous Portland cements by 29Si MAS NMR: Effects of paramagnetic ions. Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 2009, 36, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.I.; Borno, I.B.; Khan, R.I.; Ashraf, W. Reducing carbonation degradation and enhancing elastic properties of calcium silicate hydrates using biomimetic molecules. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 136, 104888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, F.; Wagner, D.; Bellmann, F.; Neubauer, J. Influence of gypsum and KOH on the hydration of pure triclinic C3S. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 491, 142679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, S.; Wang, F.; Wu, M.; Li, S.; Liu, Z.; Gao, S.; Jiang, J. Influence of sodium chloride on the hydration of C3S blended paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 369, 130543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Brochard, L.; Vandamme, M.; Ren, Q.; Li, C.; Jiang, Z. A hierarchical C-S-H/organic superstructure with high stiffness, super-low porosity, and low mass density. Cem. Concr. Res. 2024, 176, 107407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.