Abstract

This study investigates the compressive behavior of glued-laminated timber (Glulam) columns reinforced with different configurations of fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) materials, including glass (GFRP) and carbon (CFRP) fibers in the form of rods, strip/panel, and fabrics. Axial compression tests were performed under controlled laboratory conditions to examine the influence of reinforcement type and configuration on mechanical performance. Descriptive statistics, one-way ANOVA, and Tukey’s post hoc tests were used to determine the significance of differences between the tested groups. Finite element analysis (FEA) using ANSYS software2023 R1 was also conducted to validate the experimental results and to provide insight into stress distribution within the strengthened columns. The results revealed that FRP reinforcement clearly enhanced both the ultimate load and compressive stress compared to unreinforced samples. The highest performance was achieved with double CFRP rods and 5 cm carbon strips, which reached stress levels of about 43 MPa, representing an improvement of nearly 60% over raw wood. Statistical analysis confirmed that these increases were significant (p < 0.05), while FEA predictions showed strong agreement with the experimental findings. Observed failure modes shifted from crushing and buckling in unreinforced specimens to shear-splitting and delamination in reinforced ones, indicating improved confinement and delayed failure.

1. Introduction

Wood, as a natural and sustainable building material, has long been employed in structural systems and architectural applications due to its favorable properties, including low density, excellent thermal and acoustic insulation, and inherent seismic resilience [1,2]. Moreover, its renewability and minimal environmental footprint make wood an attractive option for sustainable construction [3,4]. Nevertheless, as an organic material, wood is vulnerable to environmental degradation caused by factors such as moisture, insect infestation, and fungal attack, which can diminish its service life and structural integrity [5,6].

To overcome these limitations, various strengthening and protection techniques have been developed, including lamination, chemical modification, and the incorporation of composite materials [7]. Among these, Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (FRP) composites have received particular attention in recent decades due to their high mechanical performance, durability, and compatibility with timber. In particular, Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (CFRP) and Glass Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (GFRP) exhibit high tensile strength, low density, and excellent corrosion resistance, making them ideal candidates for strengthening and retrofitting wooden structural elements [8,9,10]. The increasing use of FRP materials in construction is largely attributed to their proven effectiveness in enhancing the load-bearing behavior of concrete, steel, masonry, and timber systems [11,12]. When applied to wood, FRP reinforcement has been shown to substantially improve load-bearing capacity, stiffness, and ductility, while enhancing long-term resistance to both mechanical and environmental degradation [13,14,15].

Previous research has shown that FRP reinforcement can significantly enhance the load-bearing capacity and deformation resistance of timber elements. Shi et al. [16] investigated the axial compression behavior of FRP-confined glued-laminated timber (GLT) and cross-laminated timber (CLT) columns, reporting that FRP wrapping increased the ultimate compressive load capacity by up to 29% for CLT and 24% for GLT specimens, while also improving energy dissipation. Similarly, Qi et al. [17] examined pultruded GFRP–wood composite (PFWC) columns and observed that specimens with low slenderness ratios mainly failed by compression at the FRP–wood interface, whereas slender columns were more prone to global buckling. In addition, O’Callaghan et al. [18] demonstrated that GFRP confinement enhanced the axial performance and ductility of timber columns under compression. Collectively, these findings highlight the strong potential of FRP composites to improve the structural performance of timber members under different loading conditions.

Previous studies have shown that Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (FRP) strengthening can significantly improve the axial compressive performance of timber columns, with different wrapping techniques and composite configurations influencing the load capacity, stiffness, and ductility of the strengthened members [19,20]. Several experimental investigations have confirmed the effectiveness of FRP in enhancing the structural performance of timber elements. For example, Alsheghri and Akgül [21] reported that FRP plates can successfully replace steel sheets in wooden joints, leading to improved connection strength and stiffness. Otoom et al. [22] demonstrated that circular timber columns strengthened with GFRP wrapping exhibit considerable improvements in flexural behavior and load-carrying capacity. Moreover, Zhang et al. [23] found that retrofitting longitudinally cracked timber columns using FRP sheets effectively restored their compressive strength and enhanced overall structural integrity. Collectively, these findings confirm the potential of FRP composites as a reliable and lightweight alternative for strengthening and rehabilitating timber structural elements.

The present study addresses this gap by experimentally evaluating the effectiveness of CFRP and GFRP in strengthening laminated timber (Glulam) timber columns under axial compression. A series of compression tests was conducted on CFRP- and GFRP-reinforced specimens, alongside unreinforced controls, to quantify improvements in load-bearing capacity and deformation resistance, as well as to examine associated failure modes. By providing a direct comparison of two widely used FRP systems, this study contributes to the development of optimized and sustainable reinforcement strategies for timber columns, with particular relevance to seismic-prone regions and the preservation of historical timber structures.

2. Materials and Methods

The sample preparation process involved cutting laminated timber (glulam) and solid (unlaminated) timber into standardized dimensions of 90 × 150 × 330 mm to ensure geometric uniformity across all specimens. Fiber reinforcement was applied using an epoxy resin, which served as both an adhesive and a matrix to securely bond the fibers to the timber surface. A total of 70 specimens were fabricated: 30 reinforced with carbon fiber (CFRP), 30 reinforced with glass fiber (GFRP), and 10 unreinforced control specimens. For each FRP type (CFRP and GFRP), six strengthening configurations were evaluated with five replicate specimens per configuration (n = 5), as summarized in Table 1. The control group was equally divided into two subgroups: five laminated (glulam) specimens (n = 5) and five solid (unlaminated) specimens (n = 5). All specimens were tested under axial compression in accordance with the Turkish Standard TS 2595 [24].

Table 1.

Number of Samples Prepared for the Test.

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Laminated Timber Columns

The experimental program utilized spruce glued-laminated timber (Glulam) columns composed of five laminae, each approximately 30 mm thick. The laminae were bonded using the same epoxy adhesive employed in the strengthening process, forming a homogeneous and stable composite section. The physical and mechanical properties of the Glulam material are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mechanical and Physical Properties of wood.

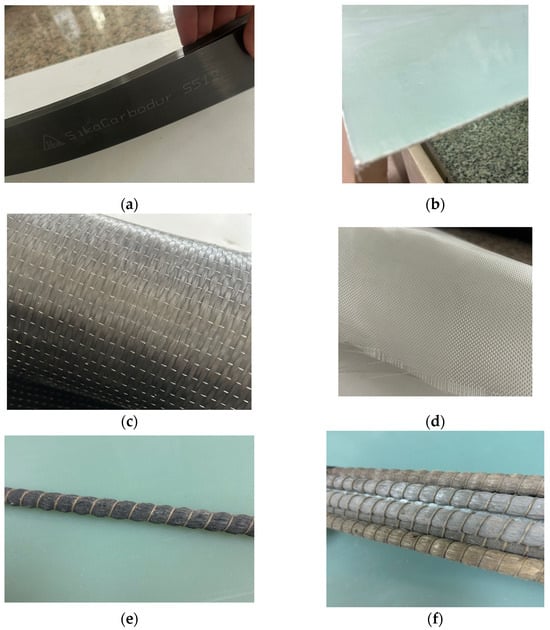

2.1.2. FRP Materials

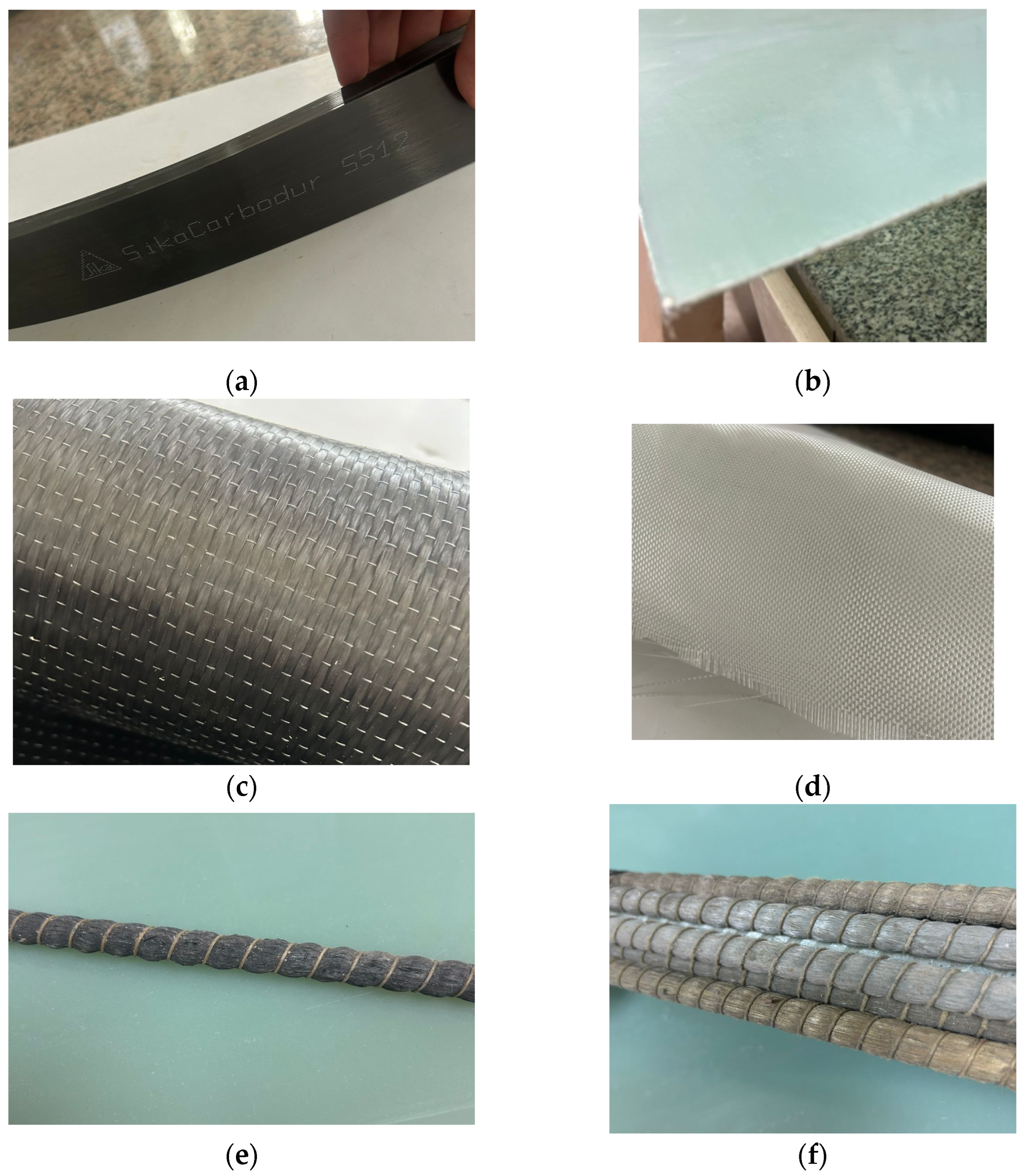

Two types of Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (FRP) materials, namely Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (CFRP) and Glass Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (GFRP), were employed as reinforcement materials. Both materials are known for their high tensile strength, low weight, and corrosion resistance, making them highly suitable for structural strengthening applications. In this study, carbon and glass fibers were used in three configurations: (i) strips/panels (factory-produced CFRP and GFRP laminates), (ii) rods (CFRP and GFRP bars), and (iii) woven fabrics. The mechanical and physical properties of all FRP materials such as elastic modulus, density, Poisson’s ratio, and nominal thickness were not experimentally measured; rather, they were obtained directly from the manufacturers’ official technical data sheets and verified against published literature values. The corresponding references have been added to Table 3. Figure 1 illustrates the shapes of the reinforcement materials used in the experimental program.

Table 3.

Mechanical and Physical Properties of FRP.

Figure 1.

Different types and configurations of FRP reinforcement materials used in the study: (a) CFRP Strip, (b) GFRP Panel, (c) CFRP fabric, (d) GFRP fabric, (e) CFRP rod, and (f) GFRP rod.

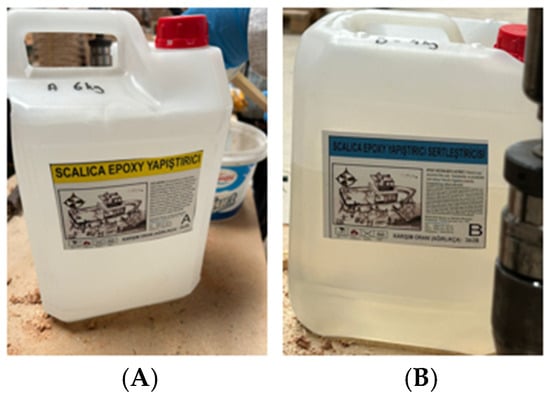

2.1.3. Adhesive

A two-component epoxy adhesive (Scalica Epoxy Adhesive, Sakarya, Turkey) was used to bond the FRP materials to the Glulam surface due to its high bonding strength, durability, and resistance to environmental factors. The adhesive consists of epoxy resin (Part A) and hardener (Part B), which were mixed according to the manufacturer’s recommended ratio and applied uniformly to the prepared timber and FRP surfaces after light sanding to enhance adhesion Figure 2. All specimens were cured at room temperature until full polymerization was achieved. The epoxy adhesive properties adopted for the analyses are summarized in Table 4 is a table prepared (reconstructed) by the author, and the epoxy properties are taken from the Scalica product brochure.

Figure 2.

Scalica epoxy adhesive system: resin (A) and hardener (B).

Table 4.

Material properties of the two-component epoxy adhesive used in this study (author-prepared table; values taken from the manufacturer’s product datasheet/brochure: Scalica Epoxy Adhesive, Turkey).

2.2. Methods

This study involved both experimental testing and numerical analysis to evaluate the structural performance of glued laminated timber (Glulam) columns under axial compression. The experimental program was designed to accurately assess the load-bearing capacity, deformation characteristics, and failure mechanisms of the specimens. All Glulam specimens were carefully fabricated, conditioned, and tested under controlled laboratory conditions to ensure consistency and reliability of the results, with the tests carried out at a room temperature of 20–23 °C and a relative humidity of approximately 50–60%.

During testing, load and displacement were continuously measured, and the corresponding failure modes were carefully documented. In parallel, finite element analyses were conducted using ANSYS software to simulate the structural behavior of the specimens under identical loading conditions. The numerical models were developed based on the material properties obtained from the laboratory tests and were validated by comparison with the experimental results.

This integrated experimental–numerical approach enabled a comprehensive evaluation of the reinforced Glulam columns, facilitating an in-depth comparison between observed and predicted behaviors and contributing to a better understanding of their structural response under axial compression.

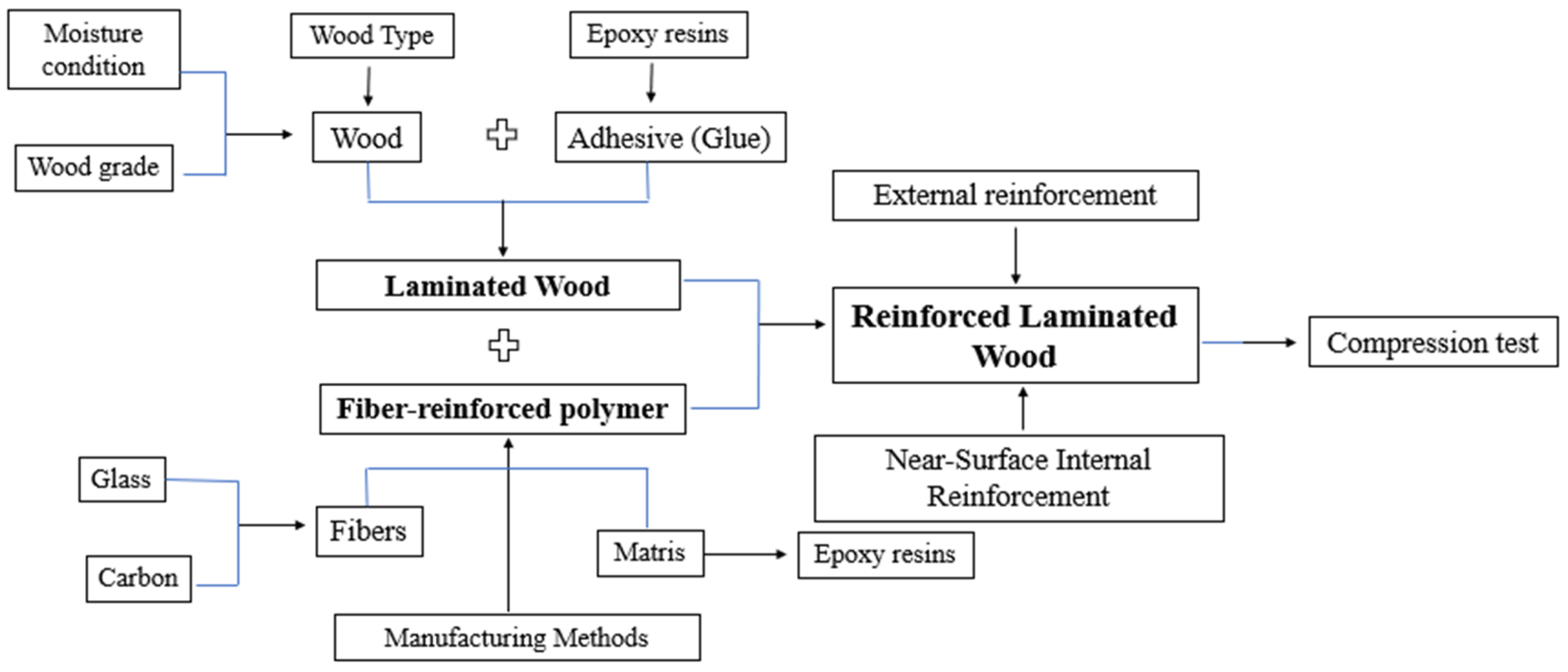

2.3. Specimen Preparation

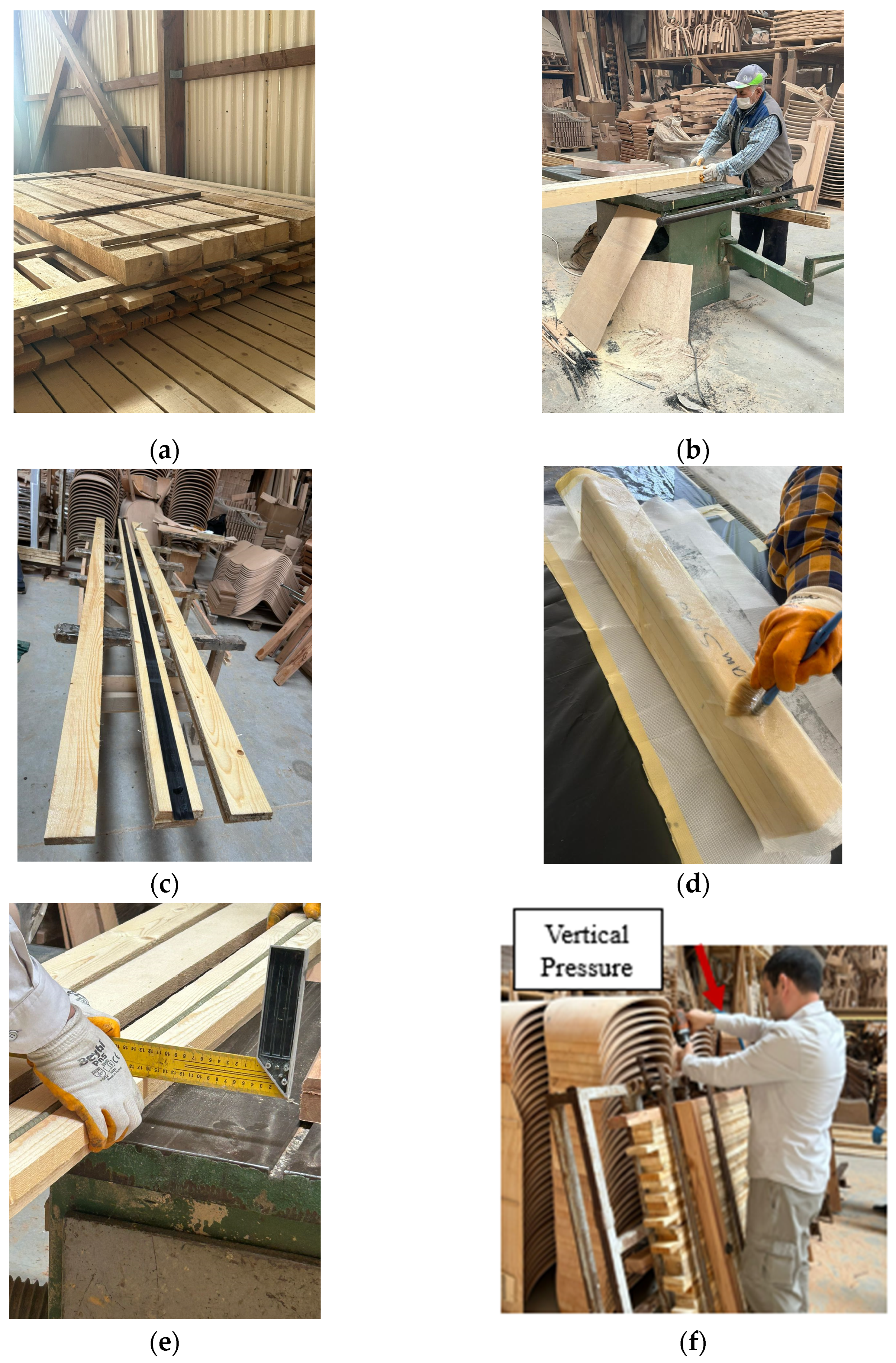

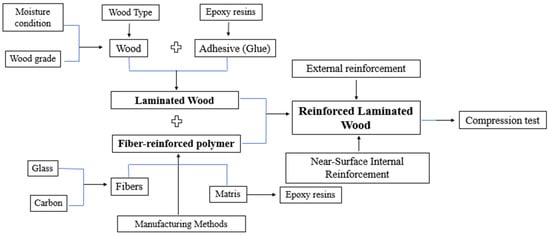

Specimen preparation was carried out under controlled conditions to ensure consistency and repeatability. The process included cutting and conditioning Glulam, applying FRP reinforcements, and curing the specimens. Figure 3 presents the overall preparation workflow.

Figure 3.

Thesis Study Flowchart.

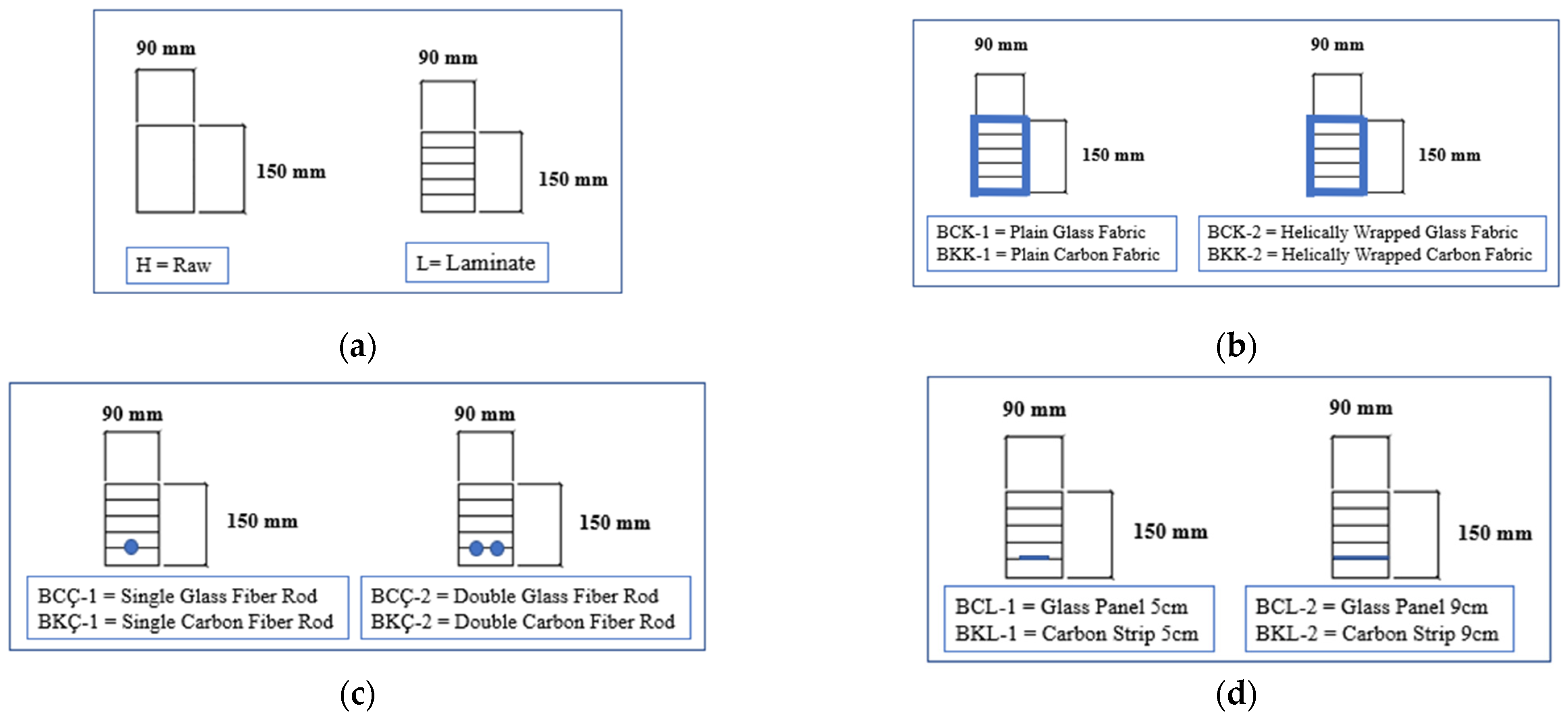

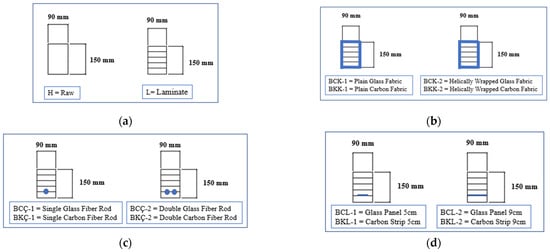

The experimental specimens were meticulously prepared under strictly controlled laboratory conditions to ensure high precision and reproducibility throughout the study. Initially, laminated timber (Glulam) were cut and conditioned, followed by the application of fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) strengthening materials, and finally subjected to a controlled curing process. The Glulam were fabricated from spruce wood (Picea spp.) sourced from a certified supplier and precisely machined to dimensions of 90 mm × 150 mm × 330 mm, in accordance with the TS 2595 standard for compressive testing of timber columns. Prior to reinforcement, the moisture content of each specimen was measured using a calibrated digital hygrometer and adjusted to approximately 12% to ensure uniform mechanical properties across all specimens. Figure 4a illustrates the unreinforced reference specimens, representing the baseline laminae.

Figure 4.

Design sample shapes for wood laminates: (a) Raw material sample and wood laminate (b) Surface Reinforcement, (c) Internal Reinforcement Near the Surface by Rod, (d) Near-surface mounted (NSM) internal reinforcement using Strips/Panels.

Two principal strengthening approaches were employed: external surface strengthening and near-surface mounted (NSM) internal strengthening.

- External Surface Strengthening

For external strengthening, specimen surfaces were finely sanded and thoroughly cleaned to remove dust, grease, and any contaminants that could compromise adhesive bonding. A two-component epoxy adhesive was prepared according to the manufacturer’s specifications and applied uniformly. Fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) fabrics, either carbon (CFRP) or glass (GFRP), were then bonded to the prepared surfaces. Two distinct fabric configurations were implemented:

Type 1: The fabric was helically wrapped around the column at a 45° angle relative to the longitudinal axis, orienting the fibers diagonally to enhance lateral buckling resistance.

Type 2: The fabric was wrapped with fibers aligned perpendicular to the column axis (0°/90°) to improve axial compression capacity.

The original 1 m wide fabric rolls were cut to a width that allowed the material to be fully wrapped around the timber column. For both configurations, the fabrics were applied in two layers with a 120 mm lap length to ensure optimal adhesion and prevent premature delamination. Following application, the specimens were allowed to cure at room temperature for two weeks. A cross-sectional representation of the externally reinforced specimens is shown in Figure 4b.

In the external strengthening process, the bonding of the FRP fabrics was carried out using a two-component epoxy adhesive. After applying the adhesive and placing the CFRP or GFRP fabric layers, the specimens were left to cure for one week to ensure proper adhesion of the wrapped fabric. Prior to this step, the bonding of the wooden lamination plates was also performed using the same epoxy adhesive, and these plates were likewise allowed to cure for one week. In total, the complete curing process for the fully strengthened specimens lasted two weeks before testing.

- 2.

- Near-Surface Mounted (NSM) Internal Strengthening

Internal reinforcement of the Glulam columns was achieved by introducing FRP materials between the fourth and fifth laminae. Two reinforcement strategies were adopted:

FRP Rods: Precision-machined grooves measuring 12 mm × 12 mm were cut along the column. In the first design, a single FRP rod (glass or carbon) was inserted, while in the second, two parallel rods were used to enhance axial stiffness and overall structural performance. Epoxy adhesive was employed to secure the rods, and specimens were cured under the same conditions as externally strengthened specimens (Figure 4c).

FRP Strips/Panels: Continuous FRP sheets (carbon or glass) were embedded between the fourth and fifth laminae. In the first design, the strip/panel width was 5 cm, while in the second, it was 9 cm. The Strips/Panels were bonded to the Glulam using epoxy adhesive to ensure continuous internal reinforcement along the column length. A cross-sectional view of both designs is presented in Figure 4d.

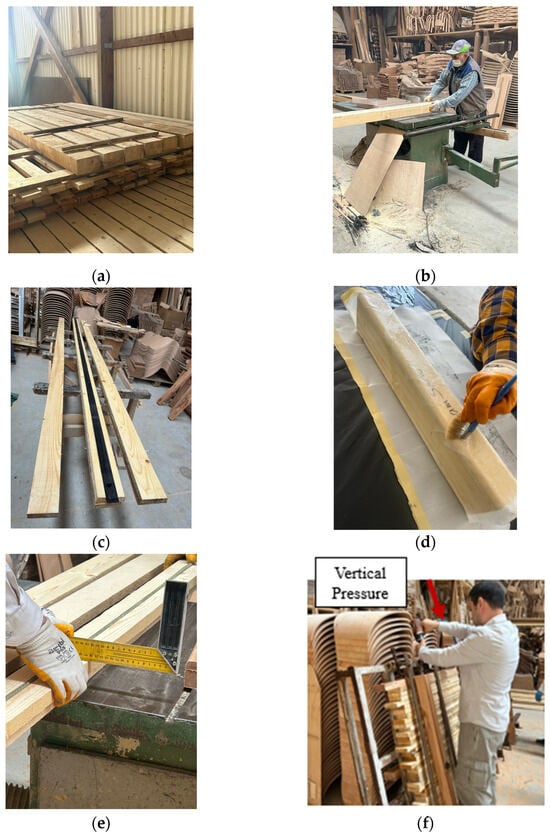

The preparation and fabrication steps of all strengthened and reference specimens were executed in a systematic sequence to ensure consistency and eliminate variability in the manufacturing process. Figure 5 summarizes the main stages of the specimen preparation workflow, beginning from the raw Glulam elements and proceeding through surface conditioning, adhesive application, and installation of the FRP reinforcement materials in their different configurations. The process concludes with the preparation of the final column specimens for axial compression testing.

Figure 5.

Preparation and manufacturing process of columns: (a) Wood samples used, (b) Softening and polishing wood, (c) Bonding process of wood and fiber boards, (d) Bonding process of wood and fiber fabrics, (e) The process of bonding wood and fiber rods, (f) Beams for Compression.

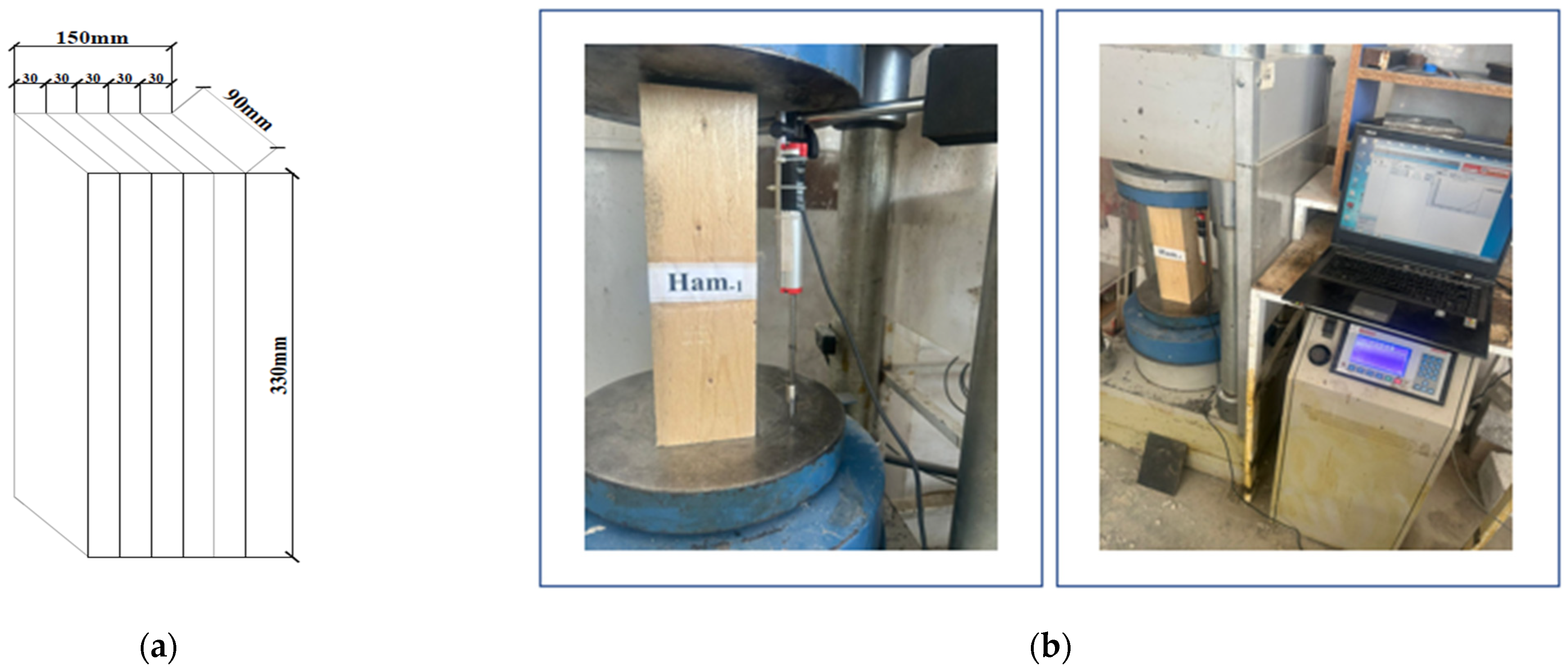

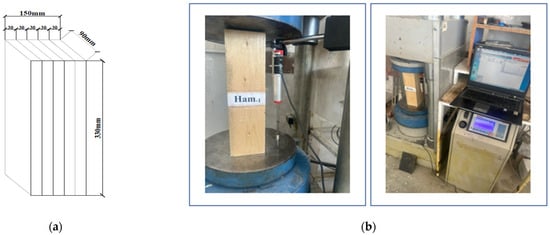

2.4. Laboratory Experiments

Compression tests were carried out to evaluate the strength and deformation characteristics of glued laminated timber (Glulam) specimens under axial loading. All tests were performed in accordance with the Turkish Standard TS 2595 (Turkish Standards Institution, 1977), which specifies the procedures for determining the compressive strength of wood parallel to the grain. The experiments were conducted using the compression testing machine shown in Figure 6, which operates with a screw-driven mechanism and has a capacity of 2000 kN. To ensure uniform load distribution, the specimen ends were capped with a suitable leveling compound.

Figure 6.

Dimensions of the Compression Test Specimen: (a) Test sample dimensions, (b) axial compression test setup.

Axial loads were applied at a constant rate of 10 kN/min until buckling or failure occurred. The axial shortening (vertical displacement) was continuously recorded using a linear potentiometer (Model: LPS 150 D 5K, OPKON, Turkey) mounted parallel to the specimen axis and spanning between the loading platens, thereby measuring the deformation over the full specimen height (Figure 6b).

2.5. Assumptions of the Numerical Analysis

In the numerical analyses, an appropriate material model was carefully selected to accurately represent the mechanical behavior of the materials involved. Since wood is an orthotropic material that exhibits direction-dependent mechanical properties, an orthotropic elastic model was adopted instead of an isotropic one. It was assumed that the elastic moduli vary along the three principal axes of the wood (Ex ≠ Ey ≠ Ez). For more advanced simulations, the elasto-plastic behavior of wood can also be considered to capture non-linear responses. The fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) materials used for strengthening are anisotropic composites characterized by high stiffness and strength along the fiber direction and significantly lower mechanical properties in the transverse direction. Therefore, orthotropic or anisotropic material models were employed to ensure an accurate representation of their behavior. Quadratic elements with mid-side nodes and second-order shape functions were used to enhance the precision of stress and strain distributions within the finite element model. Full Gauss integration with three integration points in each direction was applied to achieve stable and accurate numerical solutions. To assess the effect of mesh density on the modeling results, three different mesh configurations were defined: 5 × 5 (M5), 10 × 10 (M10), and 15 × 15 (M15). All numerical analyses were performed using the ANSYS finite element software.

3. Results and Discussion

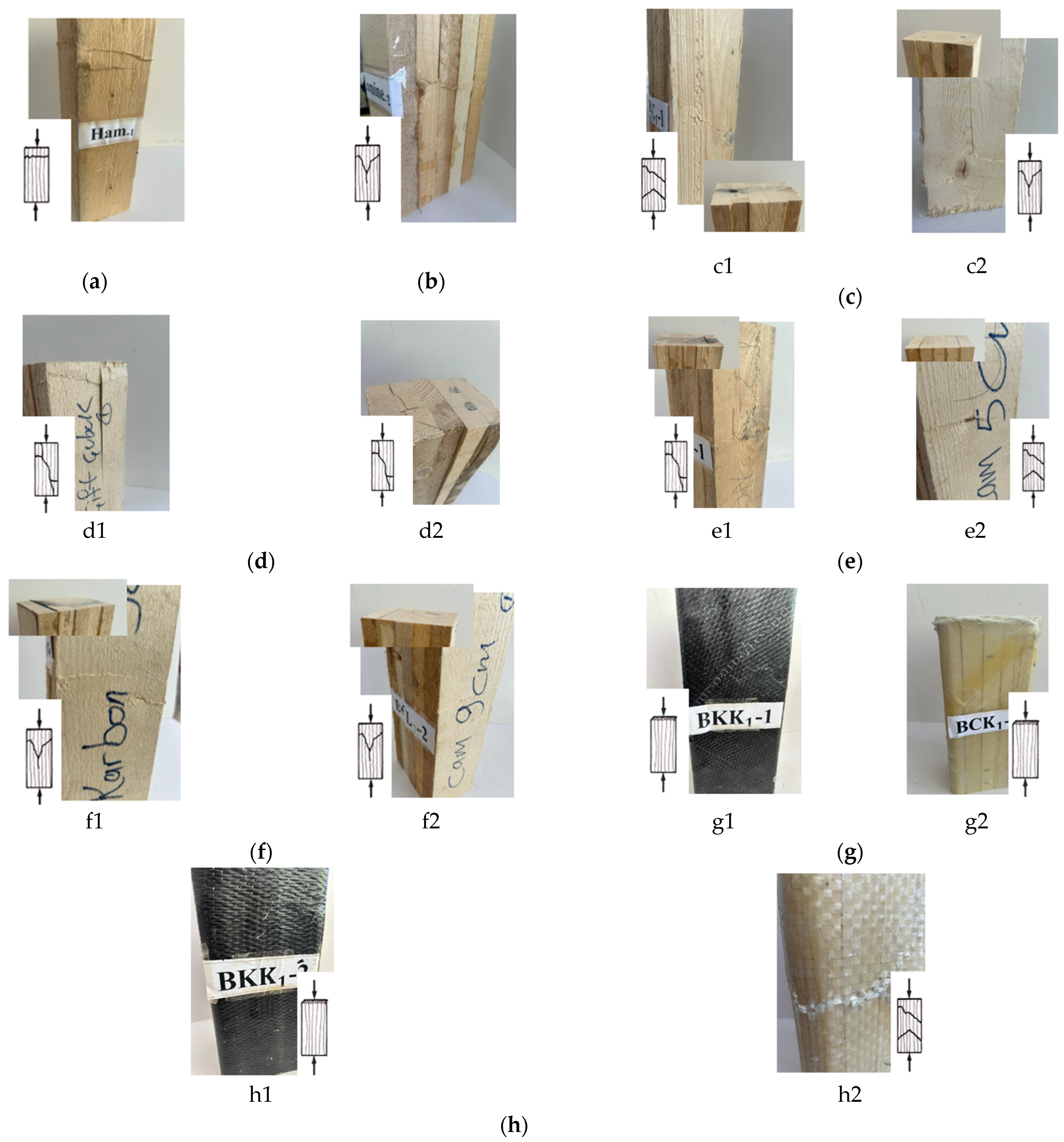

3.1. Experimental Results and Failure Modes

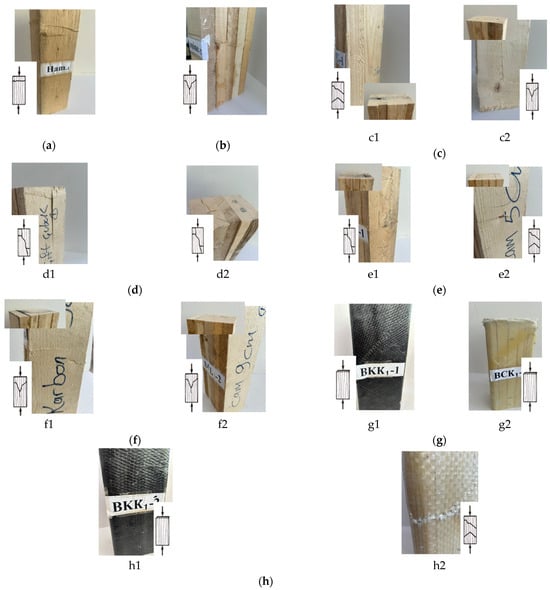

Observation of the failure modes provided insight into the deformation mechanisms governing each reinforcement configuration. Unreinforced raw wood specimens predominantly failed by crushing, exhibiting one-dimensional shrinkage along the horizontal axis (Figure 7a). Laminated but unreinforced specimens displayed combined buckling and fragmentation, with shrinkage in both horizontal and vertical directions (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

The failure of specimens under compressive loads: (a) Raw Wood, (b) Laminate Wood, (c) Single Fiber Rod, (d) Double Fiber Rod, (e) Strip/Panel 5 cm, (f) Strip/Panel 9 cm, (g) Plain Fabric, (h) Helically Wrapped Fabric.

CFRP and GFRP single-fiber rod reinforcements predominantly exhibited shear or shear-splitting failures, particularly in areas containing natural defects such as knots (Figure 7(c1,c2)). Similarly, double-fiber rod configurations in both CFRP and GFRP failed through shearing along multiple planes (Figure 7(d1,d2)). For FRP strip/panel reinforcement, different failure mechanisms were observed depending on strip/panel width and material type. The 5 cm wide CFRP strips mainly failed by local buckling followed by fragmentation (Figure 7(e1)), whereas the 5 cm wide GFRP panels exhibited shear failure accompanied by occasional shear-splitting (Figure 7(e2)). The 9 cm wide CFRP strips experienced crushing and fragmentation, sometimes coupled with shear-splitting (Figure 7(f1)), while the 9 cm wide GFRP panels primarily demonstrated wedge-splitting with localized shear-splitting (Figure 7(f2)). For fabric reinforcements, both helical (spiral) and straight-wrap configurations in CFRP- and GFRP-strengthened specimens exhibited similar brooming and end-rolling failure patterns (Figure 7(g1,g2,h1,h2)). These observations indicate that fabric wraps, while enhancing confinement, tend to promote failure modes associated with fiber rupture and end-delamination rather than global buckling.

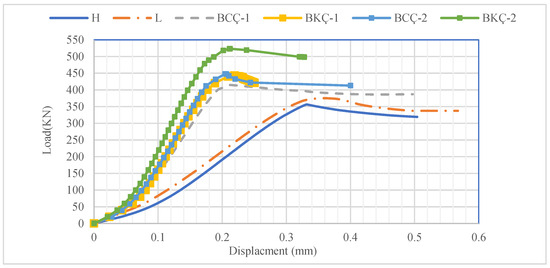

3.2. Axial Compression Behavior and Load-Bearing Capacity

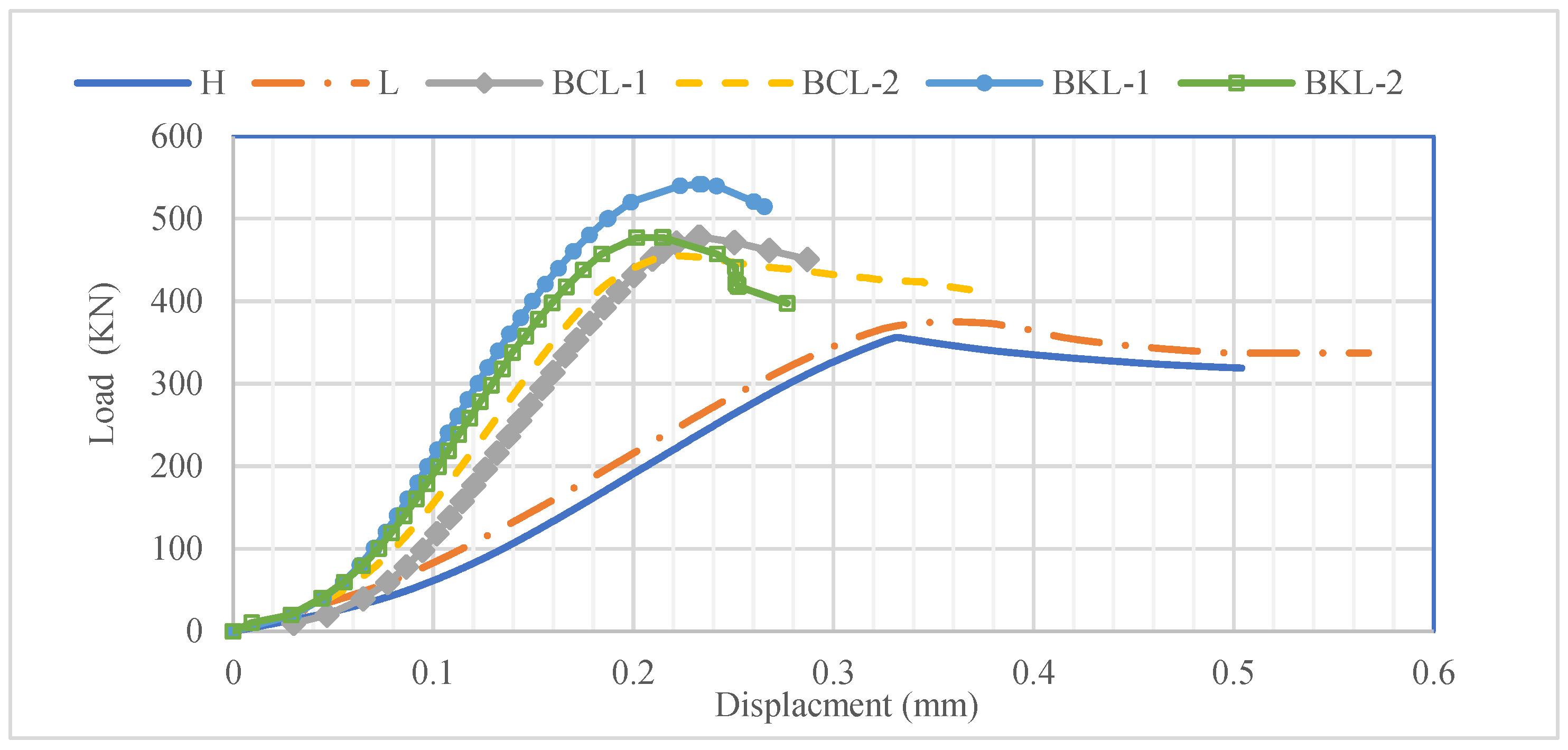

As shown in Figure 8, the load–displacement response clearly highlights the differences in axial compression performance among the tested specimen groups. For each specimen type, five replicate specimens were tested (n = 5), and the curves presented in Figure 8 represent the mean load–displacement response of these replicates. The unreinforced specimens exhibited the lowest initial stiffness and ultimate load capacity, whereas all FRP-reinforced specimens demonstrated noticeable improvements in both load-bearing capacity and deformation performance. In particular, the carbon rod-reinforced specimens achieved higher peak loads and greater stiffness than the glass rod-reinforced specimens. Moreover, the double-rod configurations provided superior axial load-carrying capacity and maintained higher resistance at larger displacements compared with the corresponding single-rod systems. Overall, these results confirm the effectiveness of FRP rod reinforcement—especially carbon reinforcement and multi-rod arrangements—in enhancing the axial compression performance of laminated timber members.

Figure 8.

Average load–displacement curves for the tested specimens (carbon and glass rod reinforcement). Each curve represents the mean response of five replicate specimens for the corresponding group (n = 5).

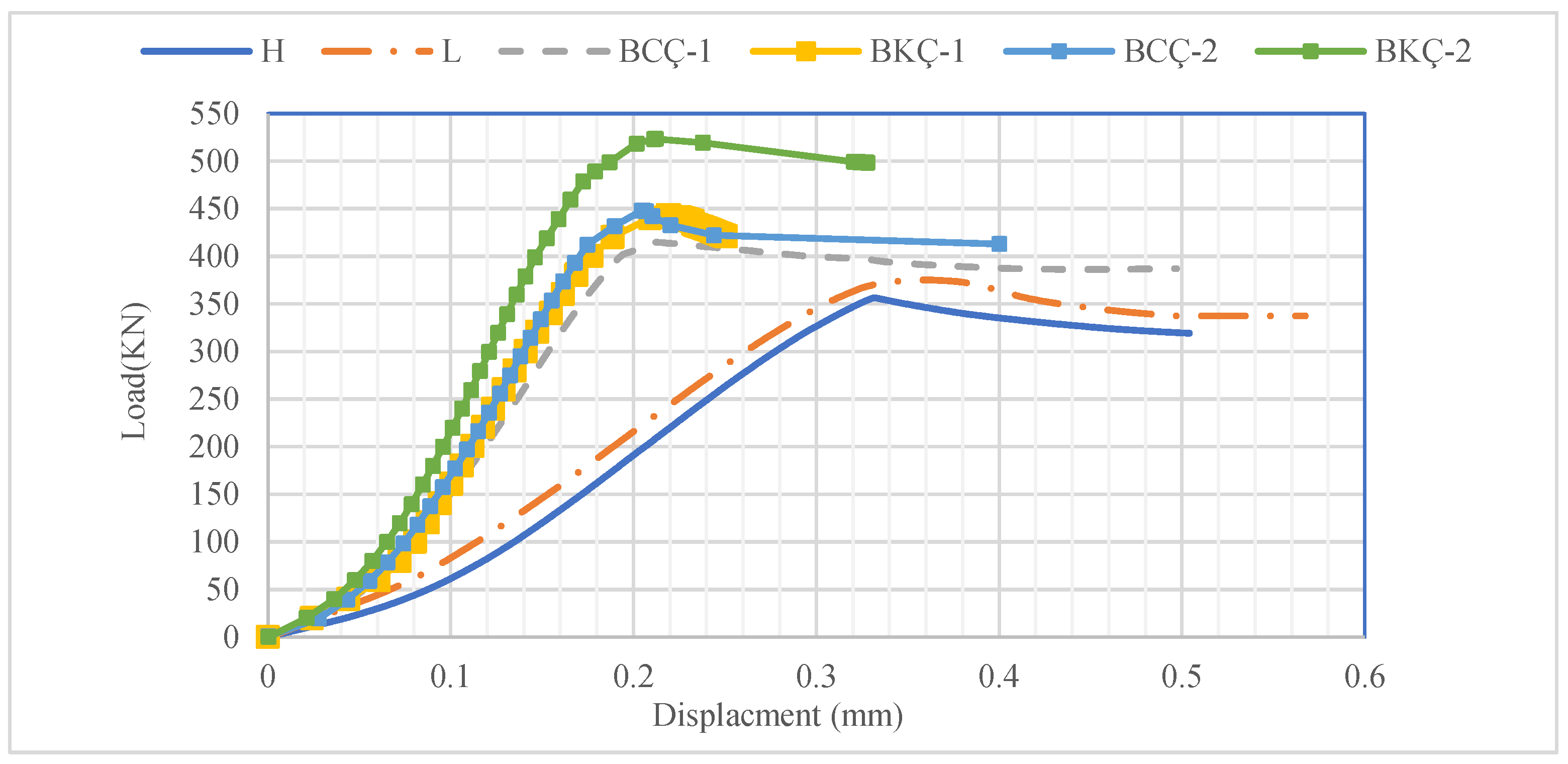

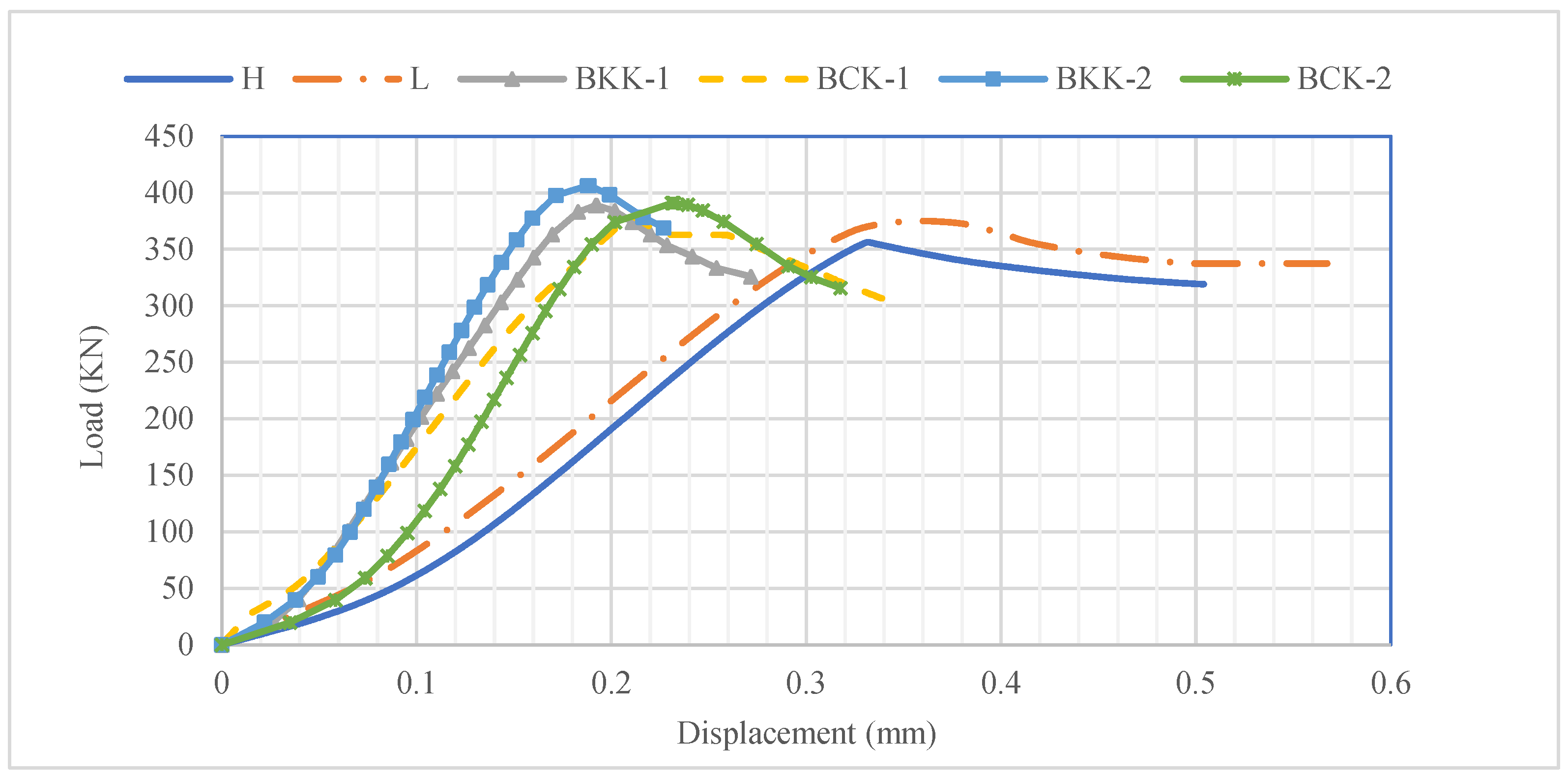

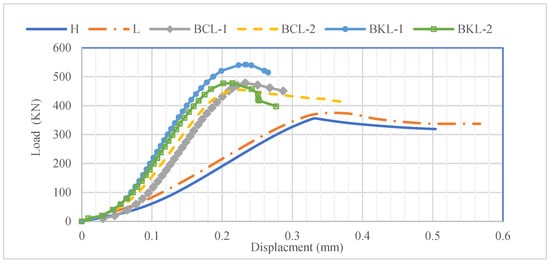

As shown in Figure 9, the load–displacement curves clearly demonstrate the distinct axial compression responses of the control and FRP-strengthened specimens. For each specimen type, five replicate specimens were tested (n = 5), and the curves shown in Figure 9 represent the mean load–displacement response of these replicates. The unreinforced specimens exhibited lower initial stiffness and reduced ultimate load capacity. In contrast, the FRP-strengthened specimens showed a clear improvement in both stiffness and load-bearing capacity. The carbon strip/panel-reinforced groups developed the highest peak loads and the steepest initial slopes, indicating superior stiffness and compression resistance, followed by the glass strip/panel-reinforced groups. Overall, these results confirm the effectiveness of externally bonded FRP strip/panel reinforcement in enhancing the axial load-carrying capacity and deformation performance of laminated timber members under compression.

Figure 9.

Average (mean) load–displacement curves under axial compression for the tested specimens (carbon and glass strip/panel reinforcement). Each curve represents the mean response of five replicate specimens for the corresponding group (n = 5).

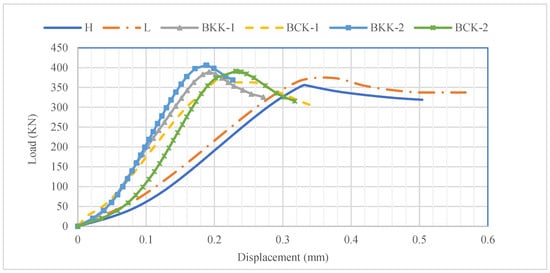

As shown in Figure 10, the specimens reinforced with double-layer spiral fiber fabric exhibited a clear enhancement in axial load-bearing capacity compared with those strengthened with straight (longitudinal) fabric reinforcement. For each specimen type, five replicate specimens were tested (n = 5), and the curves shown in Figure 10 represent the mean load–displacement response of these replicates. In addition, specimens reinforced with carbon fiber fabric consistently achieved higher ultimate loads than those reinforced with glass fiber fabric. Overall, these findings indicate that both the reinforcement configuration (spiral versus straight) and the fiber material type (carbon versus glass) have a significant and complementary effect on improving the axial compression performance of the strengthened laminated timber elements.

Figure 10.

Average (mean) load–displacement curves under axial compression for the tested specimens (carbon and glass fabric reinforcement). Each curve represents the mean response of five replicate specimens for the corresponding group (n = 5).

Overall, the results clearly confirm that carbon-based composite reinforcements provide significantly superior structural performance compared to glass-based alternatives. Strengthening configurations employing double CFRP rods and double-layer spiral CFRP fabrics exhibited the highest mechanical efficiency among all systems investigated. The reinforcement form (rod, strip/sheet, or fabric) plays a decisive role in governing the global load–displacement response. The combined trends in average load, equivalent stress, and mid-span deflection consistently demonstrate that CFRP systems offer higher stiffness, greater ultimate load-carrying capacity, and enhanced load–deformation behavior. Furthermore, the load–displacement curves, together with the corresponding ΔL values, indicate that CFRP reinforcement effectively extends the elastic range and significantly limits plastic deformation under increasing load levels.

3.3. Loading Results of Compression Test

Table 5 presents the descriptive statistics and summarized results of the axial compression tests conducted on all specimen groups. The table includes the mean, standard deviation, median, and 95% confidence intervals, along with the ultimate load, stress, and deflection values for both unreinforced and FRP-reinforced Glulam specimens. The results clearly demonstrate the significant influence of the FRP reinforcement type and configuration on the mechanical performance of the tested timber elements.

Table 5.

Test results of Loading.

- Reference Specimens (Raw and Laminated Wood): The unreinforced raw wood specimens exhibited the lowest mechanical capacity, with an average ultimate load of 356.53 kN and an equivalent stress of 26.41 MPa. In contrast, the laminated wood specimens showed a moderate improvement, achieving an average load of 375.11 kN and a stress of 29.77 kN/mm2. This enhancement, approximately 5–13% higher than that of the raw wood, reflects the beneficial effect of lamination on stiffness and load distribution. However, the relatively higher standard deviations indicate slight variability inherent in natural wood materials.

- Reinforcement with FRP Rods: The specimens reinforced with a single glass fiber rod (Single GFRP Rod) exhibited an increase in ultimate load to 414.8 kN and stress to 35.66 N/mm2, representing approximately a 40% improvement in stress resistance compared to the unreinforced timber. In contrast, the specimen reinforced with a single carbon fiber rod (Single CFRP Rod) demonstrated superior performance, achieving 442.98 kN and 36.46 MPa, highlighting the higher load transfer efficiency of carbon fibers compared to glass fibers.

When double rods were used, the performance enhancement became more pronounced:

- Double GFRP Rods: ultimate load of 448.16 kN and stress of 36.62 MPa.

- Double CFRP Rods: ultimate load of 523.40 kN and stress of 43.26 MPa.

These results indicate that increasing the number of carbon fiber reinforcement rods nearly doubled the load-bearing capacity compared to the unreinforced timber, while maintaining a low standard deviation, reflecting stable and consistent performance across specimens.

- 3.

- Reinforcement with FRP Strips/Panels: FRP strip/panel reinforcements also yielded substantial gains, depending on both the material type and strip/panel width. The glass fiber panels (5 cm and 9 cm) improved the average load to approximately 455–478 kN and the stress to 36–39 MPa, representing a clear enhancement compared to unreinforced wood. The carbon fiber strips, however, produced the most notable effect. The 5 cm carbon strip achieved an average load of 541.97 kN and a stress of 42.99 MPa, surpassing even some of the rod-reinforced specimens. Interestingly, increasing the strip width from 5 cm to 9 cm did not yield further improvement; instead, a slight decline in both load and stress was observed.

- 4.

- Reinforcement with FRP Fabrics: The fabric-reinforced specimens displayed intermediate mechanical performance between sheet and rod reinforcement systems. The helically wrapped glass fabric exhibited an average load of 390.85 kN and stress of 32.33 MPa, while the plain glass fabric achieved 380.46 kN and 31.56 MPa.

Carbon-based fabrics outperformed the glass ones, with plain carbon fabric reaching 32.94 MPa and helically wrapped carbon fabric achieving 33.45 MPa. Additionally, these specimens exhibited the lowest standard deviations (±0.19–0.42), indicating highly uniform and predictable behavior. Although the increase in strength was moderate compared to rods or sheets, the consistency and lightweight nature of fabric reinforcement make it a practical choice in applications where ease of handling and cost efficiency are important.

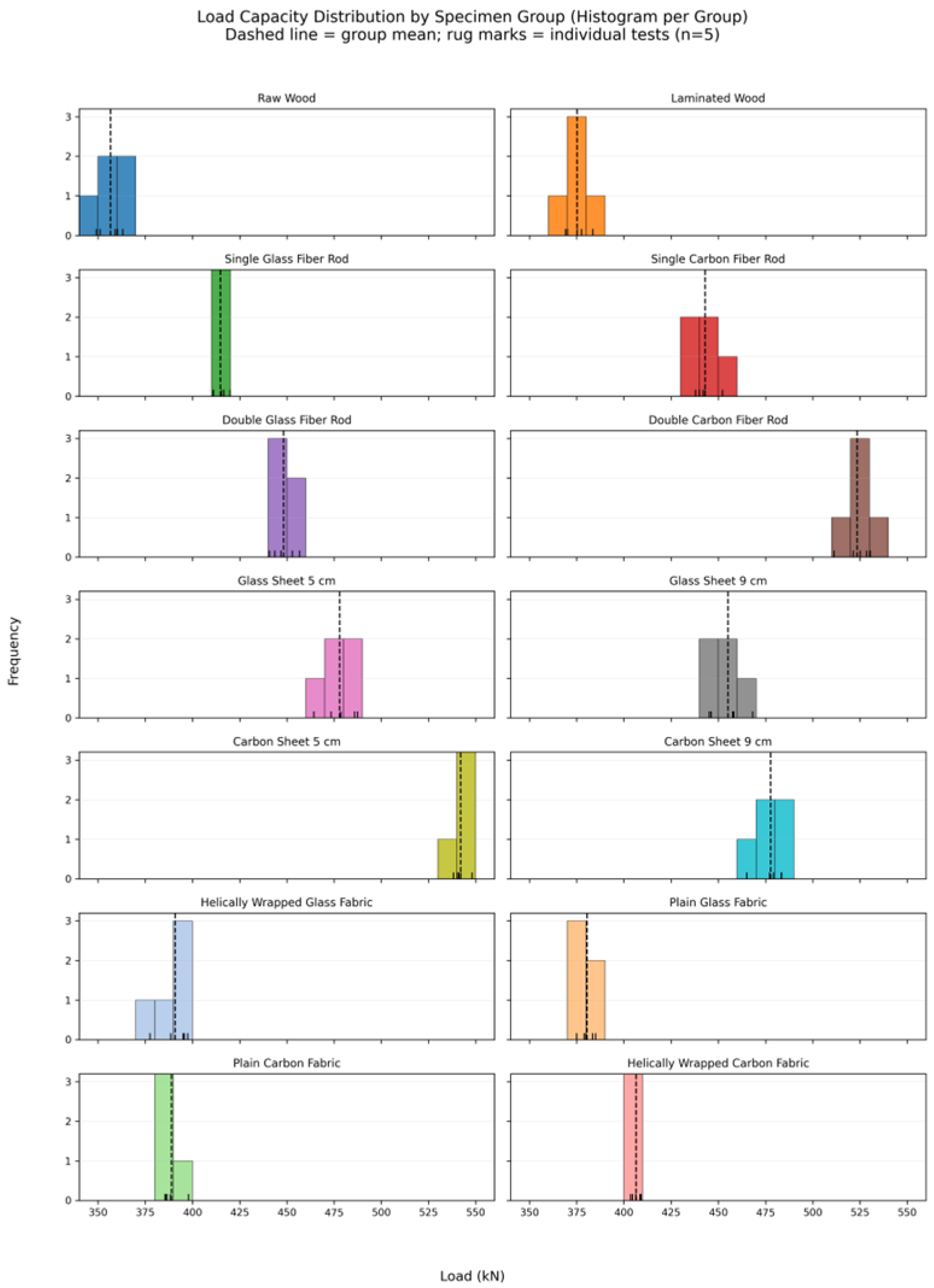

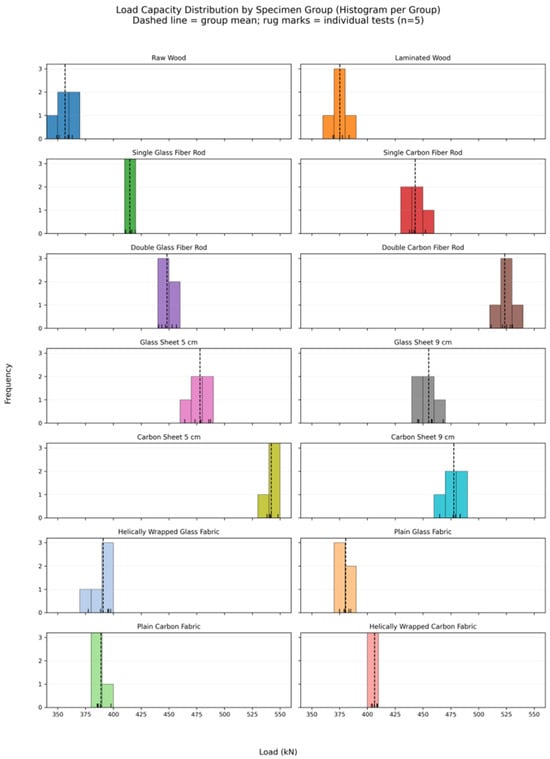

The histogram in Figure 11 shows a clear upward shift in ultimate load capacity with the application of different FRP reinforcement systems.

Figure 11.

Histogram of ultimate load values for the tested specimen groups (frequency distribution).

Unreinforced and laminated specimens exhibit the lowest load ranges (349–383 kN), reflecting the baseline mechanical response of timber. Rod reinforcements produce a marked improvement, particularly double CFRP rods, which reach the highest capacities (511–530 kN). Strip reinforcements also demonstrate strong performance, with 5 cm CFRP strips achieving 538–548 kN, outperforming both glass panels and the wider 9 cm carbon strips. Fabric reinforcements contribute moderate enhancements relative to unreinforced timber. Glass fabrics range between 375 and 397 kN, while carbon fabrics achieve higher values (385–409 kN), especially in the helically wrapped configuration. Overall, the distribution confirms that carbon-based materials consistently deliver superior strengthening effects, and that rod and sheet configurations provide the most significant improvement in compressive resistance.

3.4. Inferential Statistical Analysis: Sample Strength Comparison

Statistical analysis was performed to examine whether the observed differences in mechanical performance between the tested specimens were statistically significant. One-way ANOVA was applied to both Average Load (kN) and Equivalent stress (MPa) to determine the presence of significant differences among the groups, followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc test for pairwise comparisons. Descriptive statistics including the mean, standard deviation (SD), median, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were also calculated.

The one-way ANOVA results indicated that the differences among the tested groups were statistically significant for both Average Load and Equivalent stress (p < 0.05).

Post hoc analysis using Tukey’s HSD test revealed that the carbon fiber-reinforced specimens exhibited significantly higher load and stress values compared to the raw and glass fiber-reinforced groups.

In particular, the Carbon strip (5 cm) and Double Carbon Fiber Rod samples showed the highest mean load capacities (541.97 kN and 523.39 kN, respectively) and stress levels (43.26 MPa and 42.99 MPa), with statistically significant differences from the unreinforced control specimens (p < 0.001).

These findings confirm the superior mechanical performance of carbon-reinforced configurations, while glass fiber reinforcements provided moderate improvements relative to the control samples.

The statistical evidence clearly supports that the type and configuration of FRP reinforcement have a significant influence on the structural behavior of timber specimens. The carbon fiber reinforcements notably enhanced both the load-bearing and stress capacities, likely due to their higher stiffness and tensile strength compared to glass fibers. Moreover, the low standard deviations and narrow confidence intervals indicate consistent experimental performance and reliable bonding between the FRP and wood substrate.

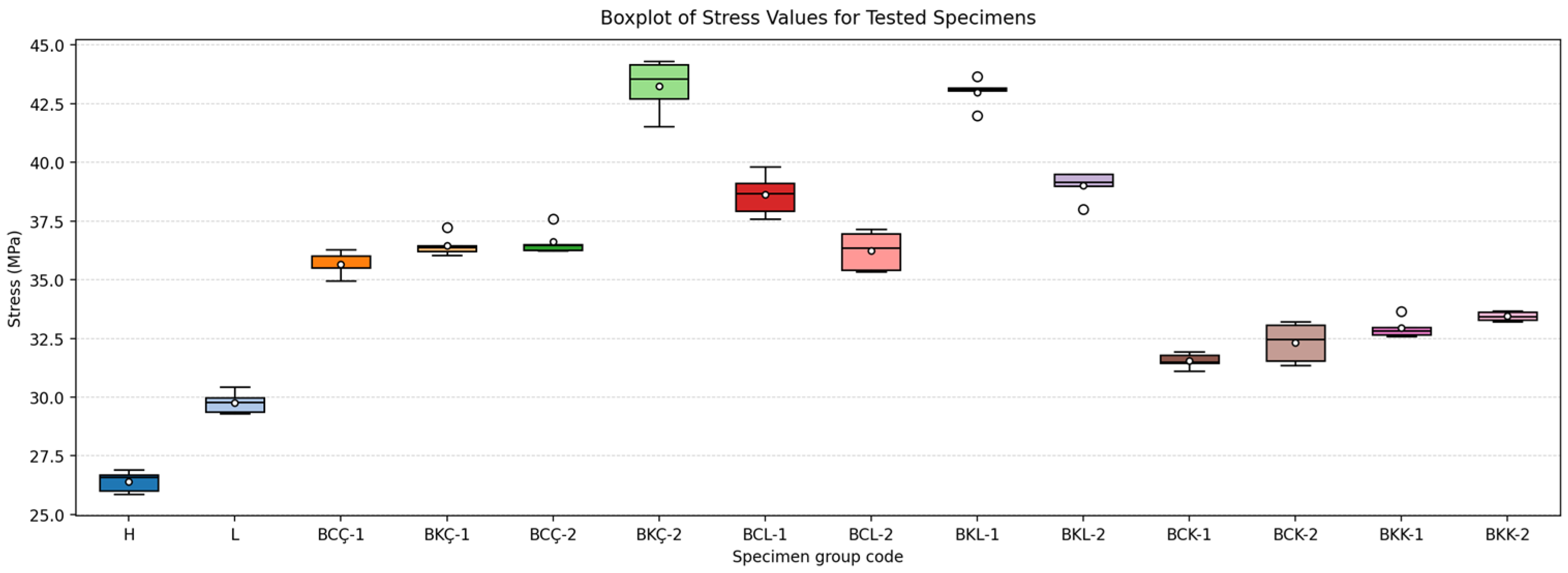

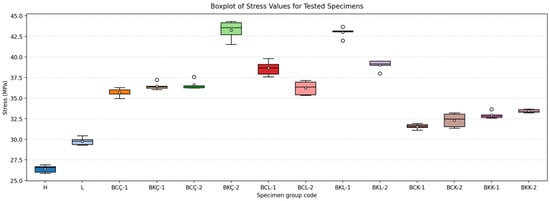

Figure 12 presents the box-plot of compressive stress for all tested specimen groups. Raw wood specimens exhibited the lowest mean compressive stress (~26.6 MPa) with relatively low variation among replicates. Laminated wood showed slightly higher mean stress (~29.6 MPa), indicating the effect of lamination on improving load capacity. Specimens reinforced with single glass or carbon fiber rods demonstrated a substantial increase in compressive stress, with single carbon fiber rods achieving a mean of ~36.5 MPa. Double fiber rod reinforcements further enhanced the performance, particularly double carbon fiber rods, which reached the highest mean stress (~43.7 MPa). Similarly, specimens strengthened with FRP strips/panels and fabrics (glass or carbon, 5 cm or 9 cm thickness, and helically wrapped) showed improved compressive strength compared to unreinforced specimens, with carbon-based reinforcements consistently outperforming glass-based ones. Overall, the box-plot illustrates not only the increase in compressive stress due to FRP reinforcement but also the reduced variability, highlighting the effectiveness of these strengthening techniques.

Figure 12.

Boxplot Comparison of Compressive Stress (MPa) among Specimen Groups (n = 5).

3.5. Numerical Tests—Discussion and Results

Timber was modeled as a three-dimensional orthotropic elastic material to represent its different mechanical behavior in the longitudinal, radial, and tangential directions. The model included the orthotropic elastic moduli (El, Er, Et), shear moduli (Glr, Grt, Gtl), and Poisson’s ratios (νlr, νrt, νtl). These material parameters were estimated based on relevant literature data for softwood species with similar physical and mechanical characteristics. The CFRP and GFRP strengthening layers were defined as linear orthotropic composite materials, characterized by high stiffness along the primary fiber direction. Perfect bonding was assumed between the FRP layers and the timber substrate, and interfacial slip or debonding effects were not considered in the models. Table 6 presents the orthotropic timber properties used in the numerical analysis. Quadratic finite elements were employed to improve the accuracy of stress and strain predictions. These elements include mid-side nodes along each edge and use second-order shape functions, allowing better representation of curved geometries and localized deformations. Fully integrated quadratic solid elements were adopted in three-dimensional analyses, with three Gauss integration points along each direction, resulting in a total of twenty-seven integration points per element. Nonlinear behavior was considered by including both material and geometric nonlinearity, and an iterative incremental procedure was applied throughout the loading stages to ensure convergence and reliable response predictions. The finite element model of the FRP layers was defined using the material properties listed in Table 7, which include the elastic moduli, shear moduli, and Poisson’s ratios.

Table 6.

Wood material properties used in numerical analysis.

Table 7.

Material properties used in the FRP finite element model.

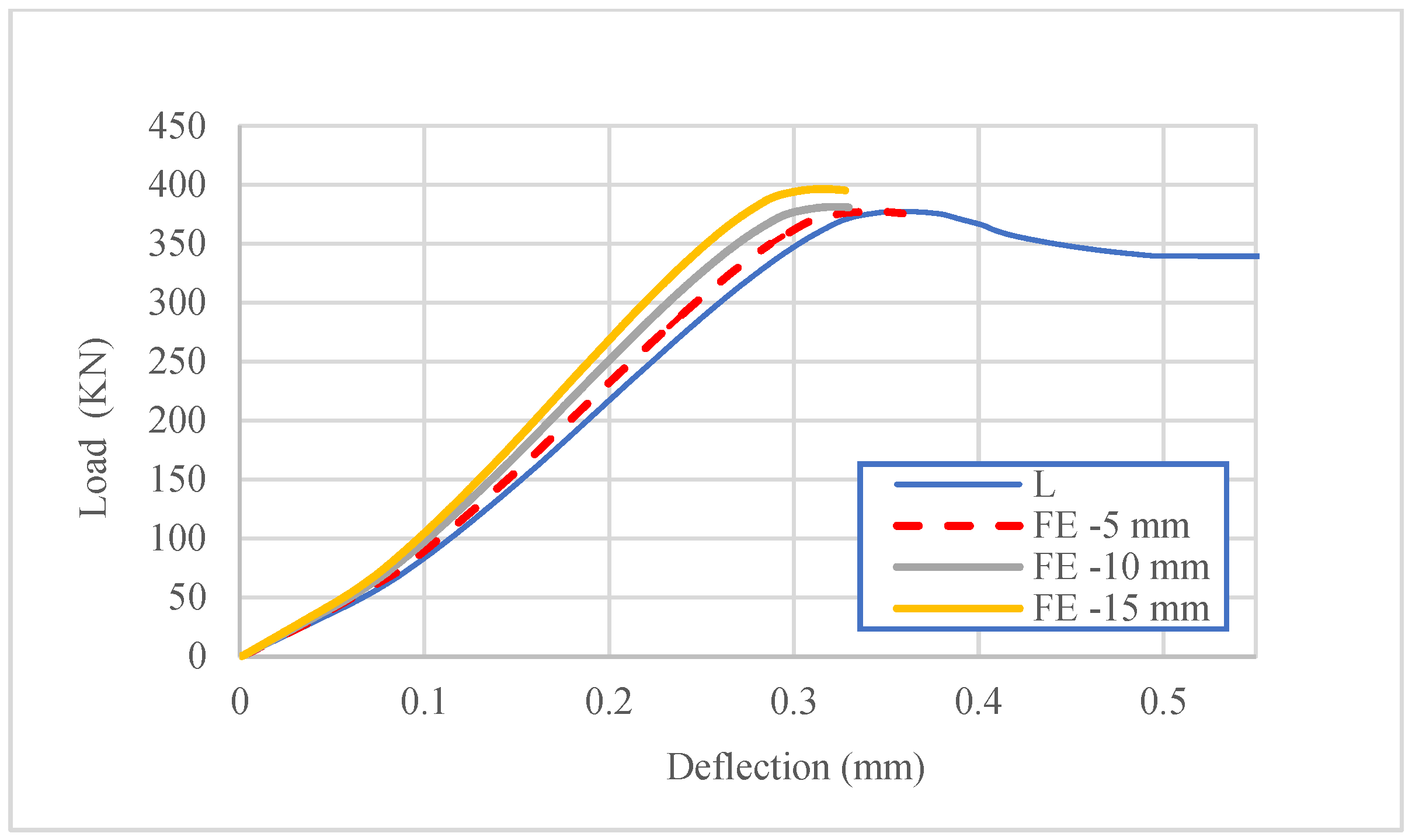

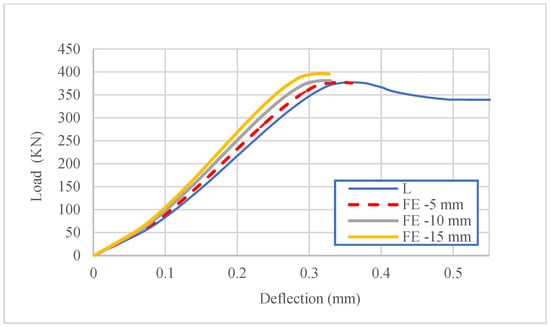

A mesh sensitivity analysis was performed using element sizes of 5 mm, 10 mm, and 15 mm. Figure 10 presents a comparison between the numerical results for the three mesh sizes and the corresponding experimental load–displacement curve. The 5 mm mesh demonstrated the closest agreement with the experimental response and was therefore adopted for all subsequent simulations. The finite element model was constructed by accurately defining the specimen geometry, assigning orthotropic material properties to timber and anisotropic properties to FRP, and aligning the local coordinate system with the fiber directions. Fixed supports were applied at the specimen base, and displacement-controlled loading was applied at the top. Load–displacement curves were obtained from the reaction forces measured at the loading platen during incremental displacement steps. This approach ensured reliable and reproducible numerical predictions that closely matched the experimental observations.

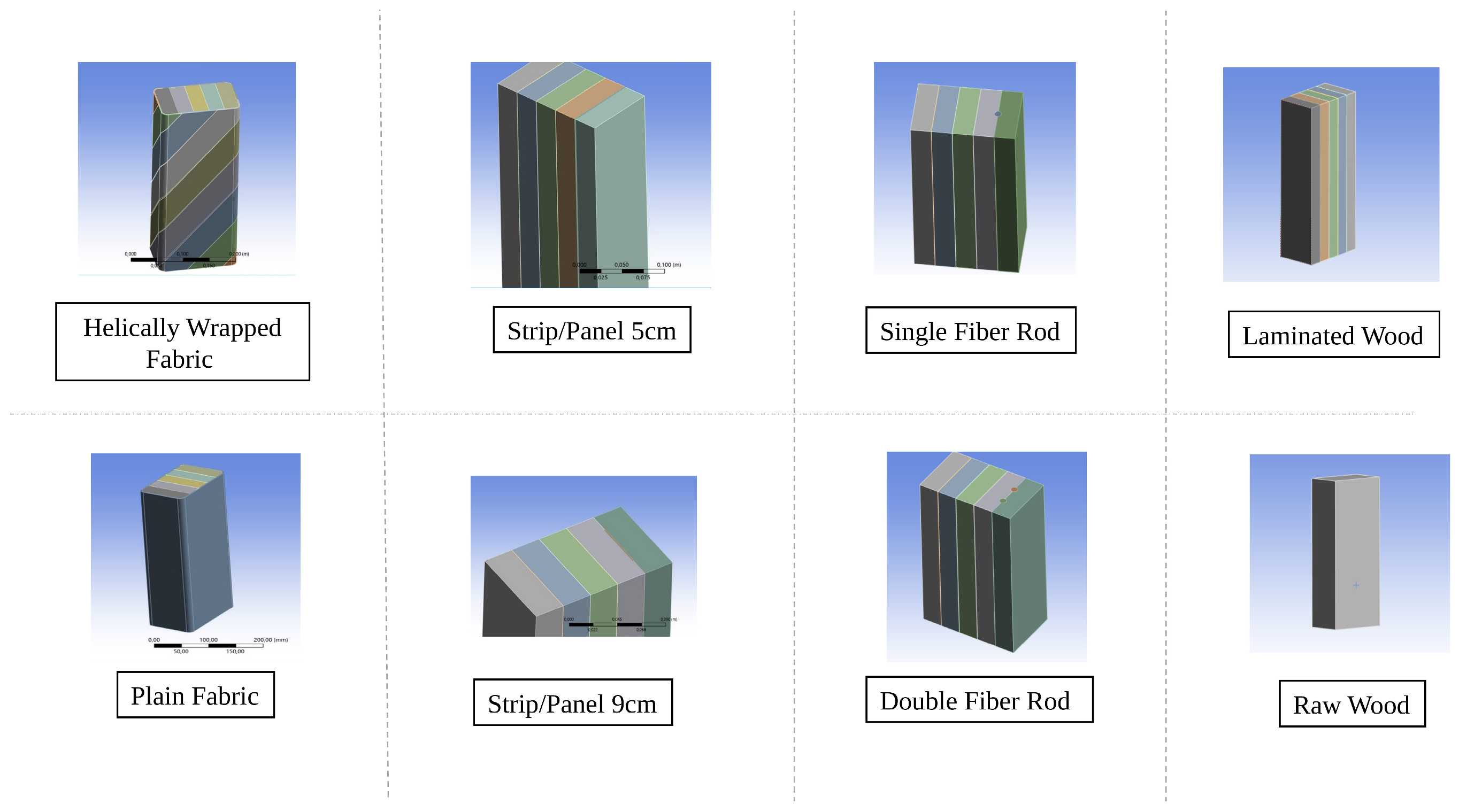

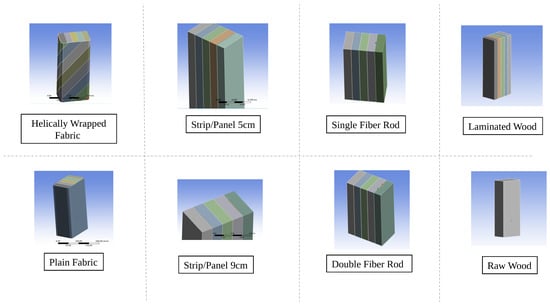

To simulate the laboratory experiments, finite element models of the wooden columns were developed using ANSYS software. The models incorporated the orthotropic material properties of wood and the anisotropic properties of GFRP and CFRP. The interaction between the FRP and wood was simulated using a perfect bond assumption, which assumes no slip between the materials. Figure 13 presents the ANSYS finite-element models developed for the tested timber specimens and reinforcement configurations.

Figure 13.

Analysis models in ANSYS.

The experimental measurements and finite element analysis (FEA) predictions exhibit good agreement for all specimen groups, as summarized by the equivalent-stress results in Table 8. Across the dataset, the reported error rates remain within 0–12%, indicating that the numerical model captures the mechanical response with acceptable accuracy. The comparison of the experimental and FEA load–deflection responses for the laminated specimen (L), performed using mesh sizes of 5, 10, and 15 mm, is presented in Figure 14 and demonstrates a consistent trend with limited sensitivity to mesh refinement. While the raw wood specimen shows nearly identical experimental and numerical values, several fiber and sheet-reinforced configurations exhibit a slight overestimation of stress in the FEA results relative to the laboratory measurements. Comparable levels of agreement between experimental testing and numerical simulation have been reported in previous studies Tankut et al. [40]; Nukala et al. [41]; Akgül et al. [42]. The remaining discrepancies can be primarily attributed to the inherent heterogeneity of wood, as well as local defects and specimen-to-specimen variability, which cannot be fully represented in idealized numerical models Kim et al. [38]. Overall, these findings support the use of FEA as a reliable tool for the structural assessment of reinforced timber elements.

Table 8.

Comparison of Laboratory Results and Software Predictions.

Figure 14.

Experimental versus FEA load–deflection curves for the laminated (L) specimen with mesh sizes of 5, 10, and 15 mm.

4. Conclusions

This study systematically examined the compressive performance of Glulam specimens strengthened with various configurations of fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) materials, including rods, sheets, and fabrics made of both glass and carbon fibers. The experimental results, supported by statistical and numerical analyses, clearly demonstrated that the type and configuration of FRP reinforcement exert a decisive influence on the mechanical behavior of timber elements.

The results revealed that all FRP reinforcements significantly enhanced the load-bearing and stress capacities of the timber specimens compared to the unreinforced controls. Among the tested configurations, double carbon fiber rods and 5 cm wide carbon fiber sheets exhibited the highest compressive performance, reaching stress levels of approximately 43 MPa, corresponding to an improvement of nearly 60% relative to raw wood. Conversely, GFRP-based reinforcements achieved moderate yet consistent enhancements, confirming their efficiency in applications where cost and weight are critical considerations.

Statistical analysis (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test) verified that the observed differences among the tested groups were statistically significant (p < 0.05). Carbon-based reinforcements exhibited markedly superior performance to glass-based systems, reflecting the inherently higher stiffness and tensile strength of carbon fibers. Additionally, the low standard deviations and narrow confidence intervals indicated stable and reproducible mechanical behavior across all carbon-reinforced specimens.

The finite element simulations performed using ANSYS showed excellent correlation with experimental outcomes, with error rates generally below 12%, thereby validating the reliability of the proposed numerical model for predicting the compressive response of FRP-reinforced Glulam. This agreement underscores the model’s capacity to capture both material anisotropy and the contribution of reinforcement to load transfer and confinement.

Failure observations revealed distinct behavioral transitions depending on the reinforcement configuration. Unreinforced specimens primarily failed through crushing and buckling, while FRP-reinforced ones demonstrated shear-splitting and delamination failures, indicating improved confinement and delayed failure propagation. Carbon-based systems, in particular, enhanced ductility and prevented premature crushing.

In summary, FRP reinforcement, especially carbon fiber rods and sheets, proved to be a highly effective and reliable method for improving the compressive strength, stiffness, and overall stability of Glulam elements. The strong alignment between experimental and numerical findings highlights the robustness of the adopted approach. Future research should focus on investigating long-term durability, cyclic loading response, and hybrid reinforcement systems to further optimize performance and sustainability in structural timber applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.A. and T.A.; methodology, H.A.; software, H.A.; validation, H.A. and T.A.; formal analysis, H.A.; investigation, H.A.; resources, T.A.; data curation, H.A.; writing—original draft preparation, H.A.; writing—review and editing, H.A. and T.A.; visualization, H.A.; supervision, T.A.; project administration, T.A.; funding acquisition, T.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by Sakarya University of Applied Sciences, Scientific Research Projects (BAP) Commission, under Projects No. 183-2023 and 229-2024.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

I extend my sincere gratitude to my advisor for their invaluable guidance and support throughout this research. Special thanks are also due to the laboratory staff for their assistance. I acknowledge the financial support from Sakarya University of Applied Sciences (Projects 183-2023 and 229-2024) and express my deepest appreciation to my family for their unwavering encouragement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CFRP | Carbon fiber-reinforced polymer |

| GFRP | Glass Fiber Reinforced Polymer. |

| FRP | Fiber Reinforced Polymer |

| LVL | Laminated Veneer Lumber |

| MOE | Modulus of Elasticity |

| Fc | Compressive Strength |

| ΔL | Average Deflection |

| H | Raw Wood |

| L | Laminated Wood |

| BCÇ-1 | Single Glass Fiber Rod |

| BKÇ-1 | Single Carbon Fiber Rod |

| BCÇ-2 | Double Glass Fiber Rod |

| BKÇ-2 | Double Carbon Fiber Rod |

| BCL-1 | Glass Sheet 5 cm |

| BCL-2 | Glass Sheet 9 cm |

| BKL-1 | Carbon Sheet 5 cm |

| BKL-2 | Carbon Sheet 9 cm |

| BCK-2 | Helically Wrapped Glass Fabric |

| BCK-1 | Plain Glass Fabric |

| BKK-1 | Plain Carbon Fabric |

| BKK-2 | Helically Wrapped Carbon Fabric |

References

- Koca, G. Seismic Resistance of Traditional Wooden Buildings in Turkey. In Proceedings of the VI Convegno Internazionale ReUSO, Messina, Italy, 11–13 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service. Wood Handbook: Wood as an Engineering Material; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory: Madison, WI, USA, 2010.

- As, N.; Dündar, T.; Büyüksarı, Ü. Classification of Wood Species Grown in Turkey According to Some Physico-Mechanic Properties. J. Fac. For. Istanb. Univ. 2016, 66, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoozi, A.A.; Firoozi, A.A.; Oyejobi, D.O.; Avudaiappan, S.; Saavedra Flores, E. Emerging trends in sustainable building materials. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, M.A.; Sağiroğlu Demirci, Ö. An overview of historical traditional wooden structure conservation techniques. GU J. Sci. Part B 2023, 11, 707–727. [Google Scholar]

- Akgül, T.; Sinha, A.; Morrell, I. Thermal degradation modeling for single-shear nailed connections. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 13, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Raftery, G.M.; Harte, A.M. Nonlinear numerical modelling of FRP reinforced glued laminated timber. Compos. Part B Eng. 2013, 52, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borri, A.; Grazini, A.; Corradi, M. A method for flexural reinforcement of old wood beams with FRP materials. Compos. Part B Eng. 2005, 36, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, K.; Lengyel, A. Strengthening Timber Structural Members with CFRP and GFRP Composites: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Değirmenci, İ.; Sarıbıyık, M. Innovative approaches in strengthening historical structures and the use of FRP materials. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium on Innovative Technologies in Engineering and Science (ISITES 2015), Valencia, Spain, 10–12 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schober, K.-U.; Harte, A.M.; Kliger, R.; Jockwer, R.; Xu, Q.; Chen, J.-F. FRP reinforcement of timber structures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 97, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, A.; Kliger, R. Strengthening of Timber Beams using FRP, with Emphasis on Compression Strength: A State-of-the-Art Review. In Proceedings of the APFIS 2009, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 9–11 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mansour, W.; Li, W.; Wang, P.; Fame, C.M.; Tam, L.; Lu, Y.; Sobuz, M.H.R.; Elwakkad, N.Y. Improving the Flexural Response of Timber Beams Using Externally Bonded Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (CFRP) Sheets. Materials 2025, 17, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çankal, D.; Sakar, G.; Çelik, H.K. A criticism on strengthening glued laminated timber beams with fibre reinforcement polymers, numerical comparisons between different modelling techniques and strengthening configurations. Rev. Constr. 2023, 22, 661–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, B.; Cheng, K.; Li, H.; Ashraf, M.; Zheng, X.; Dauletbek, A.; Hosseini, M.; Lorenzo, R.; Corbi, I.; Corbi, O.; et al. A Review on Strengthening of Timber Beams Using Fiber Reinforced Polymers. J. Renew. Mater. 2022, 10, 2073–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Wang, L.; Du, H.; Zhao, M.; Li, H.; Wang, F.; Wang, S. Axial Compression Behavior of FRP Confined Laminated Timber Columns under Cyclic Loadings. Buildings 2022, 12, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Xie, L.; Bai, Y.; Liu, W.; Fang, H. Axial compression behaviours of pultruded GFRP–wood composite columns. Sensors 2019, 19, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Callaghan, R.B.; Lacroix, D.; Kim, K.E. Experimental investigation of the compressive behaviour of GFRP wrapped spruce-pine-fir square timber columns. Eng. Struct. 2022, 269, 113618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yuan, S.L.; Dong, J.F.; Wang, Q. An Experimental Study on the Axial Compressive Behavior of Timber Columns Strengthened by FRP Sheets with Different Wrapping Methods. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 351–352, 1419–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Luo, H.; Xiao, J.; Singh, A.; Xu, J.; Fang, H. Axial Compressive Behavior of GFRP-Timber-Reinforced Concrete Composite Columns. Low-Carbon Mater. Green Constr. 2023, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsheghri, A.; Akgül, T. Use of the FRP Plates Instead of Steel Sheets in the Joints of Wooden Structures. Emerg. Mater. Res. 2022, 11, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otoom, O.; Lokuge, W.P.; Karunasena, W.M.; Manalo, A.C.; Ozbakkaloglu, T.; Ehsani, M.R. Flexural Behaviour of Circular Timber Columns Strengthened by Glass Fibre Reinforced Polymer Wrapping System. Structures 2022, 38, 1349–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Song, X.; Gu, X.; Tang, H. Compressive Behavior of Longitudinally Cracked Timber Columns Retrofitted Using FRP Sheets. J. Struct. Eng. 2012, 138, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TS 2595; Standard for Determining the Compressive Strength of Wood Parallel to the Grain. Turkish Standards Institution: Ankara, Turkey, 1977.

- TS EN 13183-1:2012; Moisture Content of a Piece of Sawn Timber—Part 1: Determination by Oven Dry Method. Turkish Standards Institution (TSE): Ankara, Turkey, 2012.

- TS ISO 13061-2:2014; Physical and Mechanical Properties of Wood—Test Methods for Small Clear Wood Specimens—Part 2: Determination of Density for Physical and Mechanical Tests. Turkish Standards Institution (TSE): Ankara, Turkey, 2014.

- TS ISO 13061-3:2017; Determination of Specific Gravity. Turkish Standards Institution (TSE): Ankara, Turkey, 2017.

- TS ISO 13061-4:2022; Determination of Modulus of Elasticity in Static Bending. Turkish Standards Institution (TSE): Ankara, Turkey, 2022.

- TS ISO 13061-17:2017; Determination of Ultimate Stress in Compression Parallel to Grain. Turkish Standards Institution (TSE): Ankara, Turkey, 2017.

- EN 338:2016; Structural Timber—Strength Classes. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- TS ISO 13061-5:2014; Determination of Compressive Strength Perpendicular to Grain. Turkish Standards Institution (TSE): Ankara, Turkey, 2014.

- TS ISO 13061-6:2014; Determination of Tensile Strength Parallel to Grain. Turkish Standards Institution (TSE): Ankara, Turkey, 2014.

- ASTM D143-14; Standard Test Methods for Small Clear Specimens of Timber. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Bank, L.C. Composites for Construction: Structural Design with FRP Materials; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sika Services AG. Sika® CarboDur® S—Product Data Sheet, Version 05.03; Sika Services AG: Zurich, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://gbr.sika.com/dam/dms/gb01/8/sika_carbodur_s.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Raicic, V. Deep Embedment Shear Reinforcement in Concrete Beams Using FRP Bars. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bath, Bath, UK, 2018. Available online: https://researchportal.bath.ac.uk/files/192682391/Vesna_Raicic_PhD_Thesis.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Toray Carbon Fibers Europe. Carbon Fibre Pultruded Profiles—Technical Datasheet CC-TE-009-12/2019; Toray Carbon Fibers Europe: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://toray-cfe.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/toray-profiles-pultrudes-joncs-et-plats.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Mallick, P.K. Fiber-Reinforced Composites: Materials, Manufacturing, and Design, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Toray Carbon Fibers America, Inc. T700S Data Sheet; Technical Data Sheet No. CFA-005; Toray Carbon Fibers America, Inc.: Flower Mound, TX, USA, 2024–2025; Available online: https://www.toraycma.com/wp-content/uploads/T700S-Data-Sheet-4.22.2025.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Tankut, N.; Tankut, A.N.; Zor, M. Finite Element Analysis of Wood Materials. Drv. Ind. 2014, 65, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nukala, S.G.; Kong, I.; Kakarla, A.B.; Patel, V.I.; Abuel-Naga, H. Simulation of Wood Polymer Composites with Finite Element Analysis. Polymers 2023, 15, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgül, T.; Sinha, A. Degradatıon of Yıeld Strength of Laterally Loaded Wood to Orıented Strandboard Connectıons After Exposure to Elevated Temperatures. Wood Fiber Sci. 2016, 48, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.