Abstract

Unsafe behaviors at construction sites often originate from cognitive failures such as lapses in memory and attention. This study proposes a novel, hybrid framework to systematically identify and predict the key contributors of cognitive failures among construction workers. First, a detailed literature review was conducted to identify 30 candidate factors related to cognitive failures and unsafe behaviors at construction sites. Thereafter, 10 construction safety experts ranked these factors to prioritize the most influential variables. A questionnaire was then developed and field surveys were conducted across various construction sites. A total of 500 valid responses were collected from construction workers involved in residential, highway, and dam projects in Pakistan. The collected data was first analyzed using conventional statistical analysis techniques like correlation analysis followed by multiple linear and binary logistic regression to estimate factor effects on cognitive failure outcomes. Thereafter, machine-learning models (including support vector machine, random forest, and gradient boosting) were implemented to enable a more robust prediction of cognitive failures. The findings consistently identified fatigue and stress as the strongest predictors of cognitive failures. These results extend unsafe behavior frameworks by highlighting the significant factors influencing cognitive failures. Moreover, the findings also imply the importance of targeted interventions, including fatigue management, structured training, and evidence-based stress reduction, to improve safety conditions at construction sites.

1. Introduction

The construction industry is considered one of the most hazardous industries, having high rates of fatal and non-fatal injuries worldwide [1]. The scale and magnitude of risk is evident from empirical statistics. In 2019, construction-related incidents resulted in 904 fatalities in China and approximately 1300 annual deaths within the European Union [1,2]. In the United Kingdom, construction-related incidents made up 31 percent of total occupational deaths [3]. Studies have also revealed that unsafe behaviors among employees have contributed 80 to 94 percent of the workplace incidents [4,5].

Although these incidents are often holistically termed as unsafe actions or procedural violations, such behaviors are often caused by cognitive failure that may occur in the form of lapses in attention, memory, and decision-making [6]. Cognitive failures hinder the identification of hazards and undermine compliance with the safety requirements. The outcomes of these failures are intensified by factors like workplace fatigue, mental strain, time pressure, poor safety awareness, and challenging environmental conditions [7,8]. Recent studies also suggest that fatigue, lack of attention, and other related psychological and physiological factors significantly impact construction safety behavior [7,9,10].

This perspective is consistent with established safety theories that link accidents to human error and behavioral breakdowns. The Reason model explains incidents as the outcome of management weaknesses resulting in active failures at the operational level [11,12]. Similarly, the Human Factors Analysis and Classification System (HFACS) categorizes accident causes into unsafe acts and the factors that shape them, including fatigue, stress, inadequate training, and deficiencies in supervision and safety management [12]. Although these frameworks acknowledge cognition-related problems, cognitive processes are often embedded within broad categories such as “human error,”, “unsafe acts,” or “unsafe behavior,” rather than being measured and analyzed explicitly [6,12]. As a result, many safety interventions continue to prioritize physical safety measures, and rule enforcement, while cognitive risk mitigation remains comparatively underdeveloped in practical construction safety management [13,14]. In recent years, research has increasingly attempted to address this gap by explicitly modeling cognitive mechanisms behind unsafe behavior. For instance, Deng et al. proposed a cognitive failure model that explains unsafe behavior through cognitive safety pathways, highlighting the value of treating cognitive failure as a measurable mechanism rather than a general explanation [9]. This approach also improves practical applicability, because safety managers gain clearer evidence on which cognitive triggers matter most and how they operate under real site conditions.

Addressing cognitive failure is essential for effective health and safety management. In this context, it is important to fill the methodological gaps that exist in the cognitive safety-related domain. First, many studies report associations or descriptive patterns but do not test predictive performance using real-world construction datasets [15,16]. Second, variable identification and screening procedures are not well-structured and comprehensive, resulting in the overlooking of certain factors. Third, most studies frequently rely on either regression-based inference or machine-learning prediction, but fewer integrate both approaches in a single framework to validate robustness and compare performance [15,16]. Recent construction safety research increasingly supports the value of ensemble machine-learning models such as gradient boosting for predictive safety analytics, often outperforming traditional classifiers in accident-related tasks [17,18,19]. However, the use of such predictive tools is still limited in research specifically targeting cognitive failure outcomes among construction workers.

Moreover, comprehensive cognitive failure evaluation for construction workers is critical, particularly in rapidly urbanizing developing economies. Safety issues are further aggravated in the context of developing countries like Pakistan, where existing construction safety standards are subpar and localized investigations into cognitive safety determinants are notably limited [20,21]. Despite evidence emphasizing importance of time constraints and inadequate training to impaired hazard perception [22,23], current safety protocols predominantly rely on physical safeguards over cognitive risk mitigation [13,14].

To address these gaps, this research aims to (i) identify and rank key cognitive factors affecting construction workers, (ii) quantify their influence on cognitive failures, and (iii) establish a data-driven framework to support practical safety interventions. This study introduces a novel, hybrid framework to identify, analyze and predict the key factors influencing the cognitive failures among construction workers. First, 30 influencing variables identified via a literature review were scrutinized and ranked by construction industry experts to select the 10 most significant cognitive factors [6,24]. Based on the expert ranking results, a questionnaire was developed and administered across multiple construction sites in Pakistan, generating 500 valid responses from construction workers [20,21]. The collected data was first analyzed using conventional statistical analysis techniques like correlation analysis followed by multiple linear and binary logistic regression to estimate factor effects on cognitive failure outcomes. Thereafter, various machine-learning models (support vector machine, random forest, and gradient boosting) were implemented to enable a more robust prediction of cognitive failures [15,25].

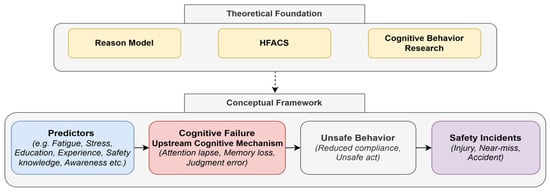

The employed hybrid approach integrates cognitive science with construction safety management to address the pressing need for context-specific risk identification of cognitive failures in the construction industry [6]. This study contributes to the domain of construction safety research in four distinct ways. At a theoretical level, it advances the existing unsafe behavior frameworks by conceptualizing cognitive failure as a measurable upstream mechanism [9,26]. Figure 1 below illustrates the theoretical positioning and the conceptual framework of the current study. The theoretical foundation of the study is based on the existing safety theories that acknowledge the role of human errors, unsafe acts, and cognitive processes in accidents. The conceptual framework models various predictors influencing the occurrence of safety incidents through cognitive failure. In this model, cognitive failure is treated as the main outcome and an upstream cognitive mechanism indicative of unsafe behavior and safety incidents at construction sites. Second, from a methodological perspective, the study presents a comprehensive workflow for factor identification, expert prioritization, and field validation that can be replicated in similar contexts [6,24]. Third, the hybrid analytical approach based on regression-based explanatory inference and machine-learning-based predictive modeling, helps identify critical factors that consistently influence cognitive failure outcomes [6,7,8,25]. Regression models explain the role of individual cognitive factors by quantifying their direction, magnitude, and statistical significance, while machine-learning models capture complex, potentially non-linear relationships to support early risk prediction. Finally, at a practical level, the findings provide empirical evidence to support targeted cognitive risk-mitigation strategies, particularly fatigue and stress management, thereby enabling proactive and data-driven safety interventions in construction environments [10,25].

Figure 1.

Theoretical positioning and conceptual framework diagram.

2. Literature Review

Unsafe behaviors among construction workers can often be attributed to cognitive lapses in attention, judgment, and decision-making. Despite the implementation of standard safety protocols, such cognitive failures remain among the most significant contributors to workplace accidents [4,5,9]. Recent studies have emphasized the importance of understanding the mental processes underlying worker behavior to improve safety outcomes [7,9]. Empirical research consistently demonstrates a strong positive correlation between unsafe behavior and cognitive failures, highlighting the critical need to further investigate cognitive mechanisms that result in safety violations, particularly in dynamic construction environments [10,26].

Theoretical safety frameworks and unsafe behavior theories have traditionally linked construction incidents with human errors and negligence. These frameworks explain accidents in terms of unsafe acts and their preconditions (e.g., fatigue, stress, and supervision deficiencies) [11,12]. However, cognitive failure is still commonly embedded within broad labels such as “human error” or “unsafe behavior,” rather than being modeled as a measurable construct. This limits practical safety management because it becomes difficult to identify which cognitive triggers matter most and how they interact under real site conditions. Molen et al. noted that the level of injury is very high among construction activities compared most other industries [27]. Although cognitive variables have attained significant research findings in other areas, very few empirical studies have been focused on the role that they play in safety behaviors at the construction site. To address this gap, Deng et al. [9] proposed a cognitive failure model that identified safety vigilance, hazard identification, and safety knowledge as key predictors of unsafe behavior among construction workers. The researchers demonstrated that unsafe behavior can be explained through cognitive pathways, however broader empirical validation across contexts and methods still remains limited.

Effective understanding of both safety cognition and risk perception is an important condition to reduce the risks of hazardous behaviors within the construction environment. Liu et al. [6] provided a comprehensive summary of factors influencing the safety cognition and developed a multi-level model to examine the effects of experience, fatigue, and time pressure on safety-related decision-making. The results imply that cognitive lapses are related to individual and work-related factors. This also highlights the need to incorporate such cognitive determinants in safety-management processes, which enhance the effectiveness of intervention programs.

Similarly, the study of safety awareness and cognitive load in construction workers is necessary. Silva et al. [14] and Kim et al. [7] have revealed that high workload can undermine the ability of the worker to identify hazardous conditions and to respond adequately to it. Moreover, stress is a vital contributor towards cognitive failure and influences unsafe behavior. Liang et al. [8] investigated the links between stress and cognitive operations, which disclosed that stress is directly associated with cognitive failure, subsequently aggravating the risk-taking behaviors. In the findings, stress mitigation is a central measure in enhancing safety at construction sites.

In parallel, construction safety research has recently focused on predictive analytics. Machine-learning approaches, in particular, have demonstrated their applications in detecting and predicting unsafe behavior [15,17,18,25]. However, predictive studies have generally targeted unsafe behavior or accident outcomes, while cognitive failure itself is rarely treated as the primary predictive target. Moreover, many studies emphasize either interpretability through statistical modeling or prediction through advanced algorithms, but fewer integrate both approaches within one framework.

Overall, existing research confirms that cognitive failure contributes to unsafe behavior and safety outcomes in construction. However, significant gaps exist in the literature where cognitive failure is not modeled as a distinct measurable outcome, and the employed approaches are not comprehensive in nature. Current research contributes to the literature on cognitive failures in the construction industry by employing an integrated approach that combines expert evaluation, field data, and predictive modeling. The traditional statistical methods along with applications of machine-learning algorithms to identify the most relative variables, offer high levels of factor prioritization and predictive accuracy, which may be of practical use to policymakers or safety professionals.

3. Methodology

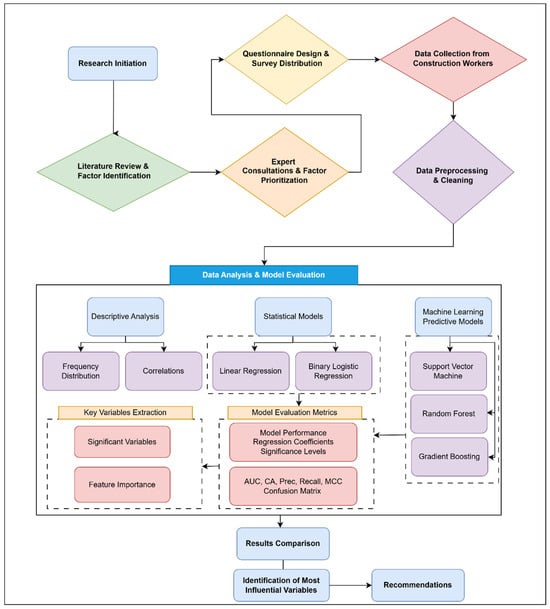

The research used a systematic approach to determine the main contributors of cognitive failures in construction workers and to develop prediction models. The methodological approach is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Methodology of the study.

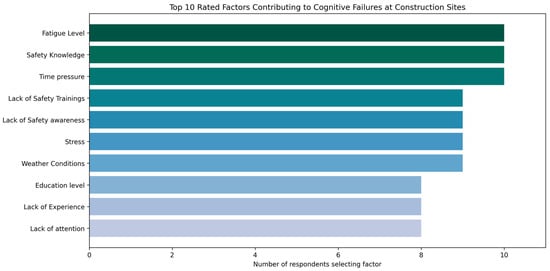

The process began by carrying out a detailed literature review to compile a list of variables that initiate cognitive failures at construction sites. Eventually, 30 relevant determinants were identified via literature review. Thereafter, the pool of determinants was prioritized by a group of experienced construction and safety managers (each with at least 5–10 years of construction experience). Ten experts were engaged because structured expert-judgment studies commonly recommend panels of 10–15 participants for relatively homogeneous expert groups to obtain reliable and stable outcomes [28]. The expert panel comprised construction safety specialists with experience across residential, highway, and dam/hydropower projects. Data collection was carried out using Google Forms. Detailed pool of factors and the resulting rankings are provided in Appendix A, whereas the top-ten ranked factors are presented below in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Selection of 10 factors impacting cognitive failures.

After the selection of the ten highest-ranked cognitive factors by an expert panel, a comprehensive questionnaire was designed and distributed among field workers. The questionnaire consisted of three sections to systematically collect data related to cognitive failures at construction sites. The first section comprised questions related to respondents’ demographic characteristics. The second section included Likert-scale statements designed to collect information on various individual and work-related factors linked with cognitive failures. Lastly, the third section attempted to collect direct information regarding specific activities and behaviors indicative of cognitive failures at construction sites. The detailed questionnaire is provided in Appendix B. It can be noted that the questionnaire also included a few reverse-coded questions to enhance the engagement of respondents. The minimum sample size was estimated using Cochran’s formula [29] for proportions because the construction workforce is large and the true population proportion was not known. The Labor Force Survey (2021) [30] indicates that about 9.5% of the employed workforce in Pakistan is engaged in construction, supporting the use of the large-population assumption. A 95% confidence level (Z = 1.96), a 5% margin of error (e = 0.05), and a conservative proportion of p = 0.50 were used to ensure maximum variability. Using these values, the minimum required sample size was approximately 385. To strengthen representation across project types and job categories and to ensure enough data for regression and machine-learning model evaluation, a larger sample was targeted. After data cleaning, 500 complete responses were retained for analysis. Data collection covered residential, highway, and dam projects, and included workers in different roles such as laborers, foremen, site supervisors, and site engineers. Several site visits were conducted during the survey period, and the research team interacted with site staff and local officials to support the credibility of participation and information collection.

The collected data was initially pre-processed for treating invalid or missing values. Such values were handled using list-wise deletion approach in which the complete row is removed from the database. Thereafter, data analysis proceeded in a sequential manner. First, descriptive statistics and correlation analysis was conducted to gain an in-depth understanding of the collected data. During this phase, various data assumptions for the implementation of regression modeling and machine learning algorithms were also verified. Following this, detailed regression and machine learning models were developed. Linear regression modelled the relationship between predictors and the continuous cognitive failure score. Moreover, binary logistic regression was performed by converting the cognitive failure score into two categories. Respondents with a mean cognitive failure score of 3 or below were classified as 0 (lower likelihood of cognitive failure). Respondents with a score greater than 3 and up to 5 were classified as 1 (higher likelihood of cognitive failure). Odds ratios were then derived to interpret the likelihood of cognitive failure based on various factors.

In order to consider possible non-linear relationships and to further improve prediction performance, three sophisticated machine learning models, i.e., Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Gradient Boosting (GB), were applied. Each of the applied machine learning algorithms offered a unique perspective for prediction modeling. Data standardization was applied where required, particularly for SVM algorithms. The dataset was split into training and testing sets using a 70:30 ratio. Model parameters were adjusted through manual hyperparameter tuning based on iterative performance checks. Models were evaluated using AUC, F1-score and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) parameters. Feature importance obtained from GB was used to identify the most influential predictors. An elaborate graphical data analysis framework is presented in Figure 2. It is important to mention that various tools like IBM SPSS Statistics (version 21.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), R Statistical Software (version 4.4.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria)and Python (Version 3.11; Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA) were used for data analysis and modeling.

4. Analysis and Results

This section summarizes the descriptive statistics to present details and demographics of the respondents, followed by a correlation analysis to examine bivariate relationships. Thereafter, results of regression-based analysis (including multiple linear regression and binary logistic regression) are presented to determine the significant contributors of cognitive failure. Finally, results of machine-learning models in terms of predictive performance along with feature importance analysis are presented.

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

A survey of 500 professionals working in the construction industry was conducted to gather data related to construction safety and cognitive factors. The detailed questionnaire is provided in Appendix B. As shown in Table 1, among the respondents, 42.8 percent were in the 26–34 age category, with an additional 38.8 percent in the 35–44 group. This tendency reflects the primary reliance of the construction workforce on middle-aged professionals. Furthermore, a smaller percentage of respondents were in the 18 to 25 age group (8.8%), while those aged 45 years and older constituted 9.6%.

Table 1.

Age distribution of respondents.

In terms of work experience, the largest group (27.4%) had between 6 and 10 years of experience, followed by 25.6% with 11 to 15 years of experience. Workers with 0–5 years of experience made up 23.2%, while those with more than 20 years of experience represented only 4.6%. This experience distribution is detailed in Table 2, with the largest proportion of respondents falling into the 6–10 years of experience category.

Table 2.

Distribution of respondents on basis of work experience.

Regarding education level, the majority of the workforce (38.6%) had education up to primary school level or below. Smaller percentages had an education level up to junior middle school (13.4%), high school (11.4%), or junior college (16%). A total of 20.6% of respondents held qualification of bachelor’s degree or above. The distribution based on education level is presented in Table 3, which indicates a broad range of educational backgrounds that may influence safety behaviors and cognitive performance on construction sites.

Table 3.

Distribution of respondents on basis of Education Level.

The demographic factors, i.e., age, experience, and education, indicate the diversity of workforce in the construction industry. It is critical to understand these characteristics for addressing cognitive safety risks and tailoring safety interventions to the needs of workers across different age groups, experience levels, and educational backgrounds.

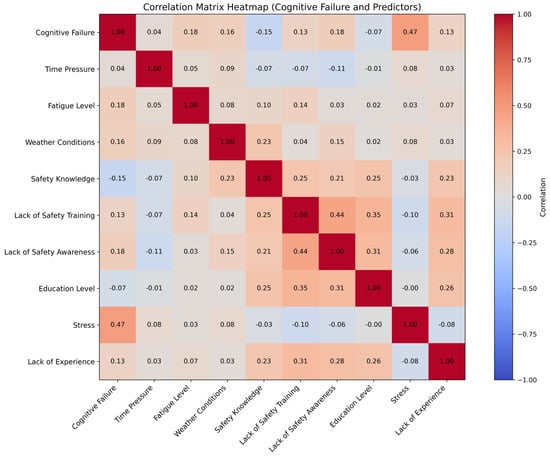

4.2. Correlation Analysis

Correlation analysis, visualized in Figure 4, examined the relationships between cognitive failure and various predictors. The strongest positive correlation was between stress (S) and cognitive failure (r = 0.474, p < 0.05), confirming that higher stress levels increase the likelihood of cognitive lapses. Moderate positive correlations were observed with fatigue level (FL), lack of safety awareness (SA), weather conditions (WC), and lack of safety training (ST), while safety knowledge (SK) showed a negative correlation with cognitive failure (r = −0.149, p < 0.05), indicating that better safety knowledge reduces the likelihood of cognitive lapses [9,10]. The heatmap further highlighted strong positive relationships between safety training and safety awareness (r = 0.445), and between education level and experience (r = 0.261), emphasizing the importance of knowledge and experience in mitigating cognitive failures.

Figure 4.

Correlation heat map.

4.3. Statistical Models

4.3.1. Linear Regression

Multiple linear regression revealed significant predictors of cognitive failure in construction workers. The ANOVA result confirmed that the overall model was statistically significant. Fatigue (FL) (β = 0.392, p < 0.001) and stress (S) (β = 0.367, p < 0.001) were the strongest predictors of cognitive failure. These results reinforce that the psychological and physical factors, such as stress and fatigue, significantly impact cognitive performance. Weather conditions (WC) also had a small but significant positive coefficient (β = 0.026, p = 0.011). Importantly, the variables representing lack of safety training (ST), lack of safety awareness (SA), and lack of experience (E) were positively associated with cognitive failure (β = 0.058, β = 0.032, and β = 0.060; p < 0.05), suggesting that lower training exposure, poorer safety awareness, and limited experience increase the likelihood of cognitive errors. Notably, safety knowledge (SK) and education level (EL) had a negative impact, suggesting that workers with better safety knowledge and education level were less prone to cognitive lapses. Table 4 presents the detailed results of the linear regression analysis.

Table 4.

Linear regression analysis.

4.3.2. Binary Logistic Regression

Binary logistic regression was used to classify workers into high and low cognitive failure risk categories. The model results indicated that fatigue level (FL) and stress (S) were the strongest predictors of cognitive failure (p < 0.001). Specifically, higher fatigue was associated with substantially higher odds of cognitive failure (Exp(B) = 63.786), while higher stress increased the odds by more than 24 times (Exp(B) = 24.285). The variable representing lack of safety awareness (SA) also showed a statistically significant positive association (B = 0.567, p = 0.003; Exp(B) = 1.763), indicating that lower awareness increases the probability of cognitive failure. Similarly, lack of experience (E) was significant (B = 0.618, p = 0.003; Exp(B) = 1.856), suggesting that less experienced workers are more likely to experience cognitive lapses. In contrast, time pressure (TP), weather conditions (WC), safety knowledge (SK), safety training (ST), and education level (EL) were not statistically significant predictors in the model (p > 0.05), implying that their effects may be weaker or mediated through dominant factors such as stress and fatigue. Overall, the results emphasize that psychological strain, physical exhaustion, limited experience, and low safety awareness are key contributors to cognitive failure risk in construction settings. Table 5 provides the regression coefficients and significance values for each variable.

Table 5.

Binary logistic regression analysis.

4.4. Machine Learning Predictive Models

The comparative performance of the three classification machine learning models is summarized in Table 6. All models achieved strong discrimination between cognitively impaired and non-impaired workers, with test-set AUC values of 0.896 for SVM, 0.909 for Gradient Boosting, and 0.881 for Random Forest. The Random Forest model attained the highest training accuracy (95.1% with AUC 0.989), but its performance dropped to 78.0% accuracy on the test set (AUC 0.881), indicating potential overfitting. In contrast, the SVM maintained an accuracy of 80.6% during training and 81.3% on test data, showing consistent generalization. Gradient Boosting also demonstrated robust generalization, with accuracy decreasing moderately from 86.6% (train) to 80.7% (test) and a higher test AUC of 0.909. In terms of precision and recall, SVM and Gradient Boosting were well-balanced on the test set, yielding F1-scores around 0.81. Random Forest, while very accurate on the training data, had a test precision of 0.783 and recall of 0.780 (F1 = 0.780). Correspondingly, the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) on the test set was higher for SVM (0.631) and Gradient Boosting (0.622) than for Random Forest (0.563), underscoring that SVM and Gradient Boosting provided more reliable and balanced predictions on unseen data [19,31]. Overall, SVM and Gradient Boosting delivered comparable and robust performance, whereas Random Forest, despite excelling on the training set, did not generalize to the evaluation set.

Table 6.

Performance metrics of each model on the training and test datasets.

Table 7 provides the confusion matrix of predictions (in percentages) for each model on the test set. SVM and Gradient Boosting both achieved balanced results for the two classes: for SVM, 77.2% of the non-failure cases (Class 0) and 79.5% of the failure cases (Class 1) were correctly classified, while Gradient Boosting correctly classified 75.1% of Class 0 and 75.8% of Class 1. The Random Forest had a slightly higher accuracy in Class 0 (80.2% correct) but lower on Class 1 (73.9% correct), indicating it missed more failure cases (26.1% false negatives) compared to SVM (20.5%) and Gradient Boosting (24.2%). Overall, all three models maintained a reasonably good balance between specificity and sensitivity, without a significant bias toward either class.

Table 7.

Confusion matrix results (percent of instances) for each model on the test dataset.

4.4.1. Best Performing ML Model

In order to determine the best performing ML model, a detailed comparison based on evaluation metrics was conducted. As described above, the models were assessed across training and testing datasets using various performance metrics. Given the comparative results, Gradient Boosting was selected as the best-performing model for this study due to its robust performance. Therefore, this model was used for further analysis to identify key behavioral and psychological predictors contributing to cognitive failure in construction environments.

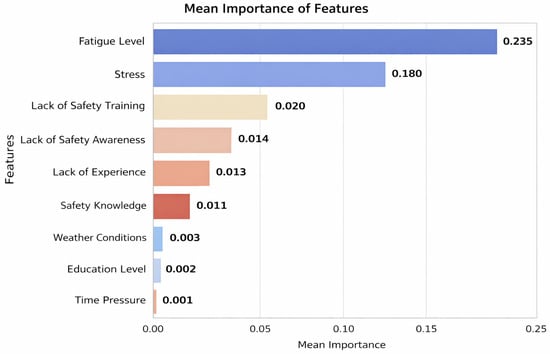

4.4.2. Feature Importance

In order to determine the role of various factors on the cognitive failure, the feature importance analysis was performed based on the Gradient Boosting ML model. Figure 5 illustrates the importance of ranking for features, emphasizing the need for strategies. As evident from the figure, fatigue level (FL) and stress (S) were determined as the most influential variables that could predict cognitive failure with mean importance scores of 0.235 and 0.180, respectively. These findings emphasize the influence of both psychological and physiological factors on cognitive lapses within construction environments [8,9]. Apart from fatigues and stress, the results also indicate weaker and secondary impact of other factors including lack of safety training, safety awareness, experience, and safety knowledge.

Figure 5.

Feature importance ranking based on AUC decrease.

5. Discussion

This study provides empirical evidence on the factors contributing to cognitive failures at construction sites, highlighting the complex interaction between psychological, behavioral, and experiential elements. The findings of both statistical and machine learning models indicate that stress and fatigue are the predominant predictors of cognitive failure across various analytical models [5,8,9]. Specifically, the linear regression model identified stress (β = 0.367, p < 0.001) and fatigue (β = 0.392, p < 0.001) as the most significant factors. These findings were further strengthened by binary logistic regression, which revealed that high stress levels increased the risk of cognitive failure by 24 times (Exp(B) = 24.285, p < 0.001), while fatigue elevated this risk by nearly 64 times (Exp(B) = 63.786, p < 0.001). These results provide insights into the safety implications of stress and fatigue with respect to cognitive failures in the construction sector. Moreover, machine learning models, particularly Gradient Boosting, consistently identified stress and fatigue as the top predictors of cognitive failure through feature importance analysis.

In addition to these dominant factors, the lack of safety awareness and lack of experience also emerged as significant predictors of cognitive failure risk. In the linear regression model, lack of safety awareness showed a positive association with cognitive failure (β = 0.032, p = 0.016), indicating that lower awareness is linked with more cognitive lapses. Similarly, lack of experience was significant in both linear (β = 0.060, p < 0.001) and logistic regression (Exp(B) = 1.856, p = 0.003), suggesting that less experienced workers are more likely to experience cognitive failure. These findings imply that cognitive performance on construction sites is not determined solely by psychosocial strain, but is also influenced by workers’ safety cognition and experience level, which may influence safety behavior under dynamic site conditions.

Safety knowledge showed a negative association in the linear regression model (β = −0.032, p = 0.004), indicating that stronger knowledge may reduce cognitive lapses. However, it was not statistically significant in the logistic regression model, which suggests that safety knowledge may influence cognitive failure indirectly rather than acting as a direct determinant of high-risk classification. This highlights that safety interventions should focus not only on knowledge delivery but also on strengthening practical awareness and experience-based decision-making under real site conditions. Moreover, time pressure and weather conditions showed comparatively weaker predictive influence across the models. These results suggest that such contextual factors may contribute indirectly by intensifying fatigue or stress rather than acting as independent drivers of cognitive failure [26]. Furthermore, lack of safety training showed a significant association with cognitive failure in linear regression analysis, but a weaker and secondary role in machine-learning models. This suggests that training influences cognitive failure indirectly by interacting with other factors, rather than acting as a dominant predictor. Consequently, training interventions should be integrated with fatigue and stress management to effectively reduce cognitive failure risk.

Moreover, the results of machine-learning models indicate that these ensemble algorithms can effectively model the complex relationships (linear or non-linear) between the predictors and cognitive failure outcome. These models further strengthen the outcomes of conventional regression models. Among the machine learning models, Gradient Boosting achieved the highest test AUC, while SVM demonstrated strong generalization with the highest test accuracy.

The proposed framework employs the regression analysis and machine-learning models as a deliberate methodological choice. Regression models were used to assess individual cognitive factors by quantifying their direction, magnitude, and statistical significance, while machine-learning models captured complex, potentially non-linear relationships to support early risk prediction. Therefore, explanatory insights derived from regression models directly strengthened the predictive modeling stage, ensuring that machine-learning outputs remain theoretically grounded rather than purely data-driven. Together, these approaches converge to identify fatigue and stress as dominant drivers of cognitive failure and translate this understanding into actionable, data-driven decision support for proactive construction safety management.

These findings fit well with traditional accident causation frameworks such as the Reason model and HFACS, which link incidents to unsafe acts and upstream conditions like fatigue, stress, and weak safety cognition. However, these frameworks usually treat cognition broadly as “human error” rather than measuring cognitive failure directly. In line with Deng et al. [9], our results show that cognitive failure can be captured as a measurable outcome and is strongly shaped by psychosocial strain—especially fatigue and stress—across both regression and machine-learning models. This is also consistent with Liang et al. [8], who reported that stress affects safety outcomes through cognitive pathways. The effects of lack of safety awareness and lack of experience further support the view that safety cognition and construction experience shape hazard recognition and decision-making on site [6,9].

Overall, this research emphasizes that cognitive failures in construction safety are not merely individual errors but reflect underlying vulnerabilities related to psychological and physiological safety cognitions. From a practical perspective, the dominance of fatigue and stress suggests that safety programs should treat psychosocial and physiological strain as operational safety priorities rather than secondary welfare issues. Interventions may include fatigue risk management (e.g., work–rest scheduling, shift rotation, and break enforcement), workload planning to reduce chronic stress exposure, and routine safety briefings that reinforce attention control and decision-making under pressure. Improving site-level safety awareness and mentoring less experienced workers may further reduce cognitive lapses, particularly in complex or time-sensitive construction tasks.

Although the analysis was conducted based on data collected in Pakistan, the identified cognitive factors, particularly fatigue, stress, and safety awareness, are theoretically justified and consistent with the existing construction safety literature, suggesting their relevance beyond a single regional context. However, further validation of the proposed cognitive failure framework across different regions and environments should be conducted. This study relies on self-reported cognitive failure measures collected through questionnaire data, which may be affected by reporting bias and common method variance. Future research should combine subjective data with objective indicators such as near-miss logs, incident records, observational audits, or wearable fatigue and stress monitoring to support objective–subjective data fusion. Longitudinal designs would also help clarify causal pathways and evaluate whether targeted interventions reduce cognitive failure over time.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study proposed an integrated framework to identify and predict cognitive failure among construction workers in high-risk project environments. The study integrated cognitive science and construction safety management to develop and validate a hybrid framework combining expert-based factor prioritization, regression analysis, and machine-learning modeling. Moreover, another contribution of this study was the explicit conceptualization of cognitive failure as an upstream mechanism influencing unsafe behavior and safety outcomes.

The study initiated with the prioritization of a literature-driven factor pool through expert judgment, and the resulting top factors were evaluated using survey data from 500 workers across highway, dam, bridge, and residential construction projects. Regression analysis and machine-learning models consistently showed that fatigue and stress are the strongest predictors of cognitive failure, while limited safety awareness and lack of experience also emerged as important contributing factors. Among the predictive models, Gradient Boosting achieved the highest discrimination performance (AUC ≈ 0.91), supporting the value of ensemble learning for cognitive-risk screening in construction settings.

From a practical standpoint, the findings suggest that construction safety programs should treat fatigue and stress as operational safety risks rather than secondary welfare issues. Organizations can strengthen prevention by implementing fatigue-management strategies such as structured rest breaks, shift rotation, and limits on extended working hours, particularly on demanding projects. Stress reduction measures may include workload planning, realistic scheduling, and access to on-site psychological support where feasible. In parallel, targeted safety training should be designed around worker needs and literacy levels. Mentoring and close supervision of less experienced workers may also reduce cognitive lapses during high-demand tasks.

The predictors derived from feature importance analysis of Gradient Boosting model provide a practical basis for prioritizing interventions. Simple management strategies such as workload adjustment, additional supervision, or safety briefings can be employed to reduce the likelihood of cognitive failures. These steps support a shift from reactive compliance-based safety management to proactive cognitive risk mitigation.

This study is limited by its cross-sectional design and reliance on self-reported measures, which may be affected by reporting bias. Future research should combine subjective assessments with objective indicators such as near-miss records, incident logs, wearable fatigue monitoring, or observational site audits to strengthen causal inference and improve predictive reliability. Although the proposed framework has been validated in the context of Pakistan, the significant contributing factors, i.e., fatigue, stress, safety awareness, etc., are not inherently specific to a particular region. These factors are consistently emphasized in the existing literature as well. Therefore, the proposed cognitive failure framework can be replicated in other regions to evaluate the relative impact and strength of various contributing factors under different cultural and project conditions. Additional validation across other regions and project contexts would help assess the broader applicability and robustness of the proposed framework.

Author Contributions

M.A., M.A.B.T. and M.A.K. conceived the study and were responsible for the design and development of data analysis. M.A., M.N.A., M.A.B.T. and M.A.K. were responsible for data collection and analysis. S.A., R.M.C. and M.A.K. were responsible for data interpretation. M.A.K., M.A. and M.N.A. wrote the first draft of the article. S.A. and R.M.C. reviewed and edited the manuscript. M.A.K. acquired the funds for the study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2601).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The ethical declaration for this study was approved by the Department of Civil Engineering, International Islamic University, Islamabad, Pakistan. It is confirmed that the subject study, comprising the research objectives, methodology, impact, and scheduled tasks, does not involve any ethical issues. All data collected during the study adheres to ethical guidelines to ensure the protection of privacy and confidentiality. Data handling procedures strictly comply with ethical protocols, and access to the data is limited to authorized personnel only. (protocol code: IIUI/FET/DCE/24-P/03, approval date: 6 March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data set that supported the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU). The authors extend their appreciation for the financial support that has made this study possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

| Factor | Expert Rating | Rank |

|---|---|---|

| Fatigue Level | 10 | 1 |

| Safety Knowledge | 10 | 2 |

| Time pressure | 10 | 3 |

| Lack of Safety Trainings | 9 | 4 |

| Lack of Safety awareness | 9 | 5 |

| Stress | 9 | 6 |

| Weather Conditions | 9 | 7 |

| Education level | 8 | 8 |

| Lack of Experience | 8 | 9 |

| Lack of Attention | 8 | 10 |

| High Load Physical Exertion | 7 | 11 |

| Sleep | 7 | 12 |

| Hazard Type | 6 | 13 |

| Professional Expertise | 6 | 14 |

| Safety Behavior Attitude | 6 | 15 |

| Work Schedule | 6 | 16 |

| Age | 5 | 17 |

| Reward/Penalty for Safe/Unsafe Behaviors and Performances | 5 | 18 |

| Safety Vigilance | 5 | 19 |

| Smoking | 5 | 20 |

| Motivation Level | 4 | 21 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | 4 | 22 |

| Personality Type | 4 | 23 |

| Site Noise Conditions | 3 | 24 |

| Marital Status | 3 | 25 |

| Safety Beliefs | 3 | 26 |

| Habits | 2 | 27 |

| Interpersonal/Social Relationships | 1 | 28 |

| Job Position | 1 | 29 |

| Work Skills | 0 | 30 |

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Participant Demographics

- Age: ________

- Designation (tick one): ☐ Laborer/Worker ☐ Foreman ☐ Site Supervisor ☐ Site Engineer

- Years of Experience in Construction: ________

- Education Level (tick one): ☐ Primary School and below ☐ Junior Middle School ☐ High School ☐ Junior College ☐ Bachelor’s Degree or above

Appendix B.2. Main Questionnaire Items (5-Point Likert Scale)

Instruction: Please read each statement carefully and select the response that best reflects your opinion or behavior.

Response options: 1 = Strongly Disagree; 2 = Disagree; 3 = Not Sure; 4 = Agree; 5 = Strongly Agree.

Appendix B.2.1. Time Pressure

- I often feel rushed to complete tasks due to time constraints.

- Time pressure leads to increased stress and potential safety lapses.

- I always prioritize completing tasks quickly over following safety procedures.

Appendix B.2.2. Fatigue

- 4.

- I believe that working with fatigue is just as safe as working when fully rested.

- 5.

- I often get tired during my work on the construction site.

- 6.

- I prioritize taking breaks to manage fatigue and maintain alertness.

Appendix B.2.3. Weather Conditions

- 7.

- Adverse weather conditions make it challenging to work safely on the construction site.

- 8.

- I feel confident in my knowledge of safety procedures in various weather conditions.

- 9.

- I ignore weather forecasts when planning safety measures.

Appendix B.2.4. Safety Knowledge and Training

- 10.

- I feel confident in my understanding of safety protocols on the construction site.

- 11.

- Safety knowledge is a top priority for me in my work.

- 12.

- I believe continuous learning about safety is essential for preventing accidents.

Appendix B.2.5. Lack of Safety Training and Awareness

- 13.

- I actively participate in safety training programs provided by my employer.

- 14.

- I believe regular safety drills are essential for preparedness.

- 15.

- I believe experience gained on the job is sufficient without additional safety training.

- 16.

- I am constantly aware and actively report unsafe conditions to my supervisor.

- 17.

- I believe maintaining high safety awareness is crucial for accident prevention.

- 18.

- I believe accidents can happen even with high safety awareness.

Appendix B.2.6. Education Level

- 19.

- I believe the level of education influences understanding of safety procedures.

- 20.

- I believe individuals with higher education levels are more safety-conscious.

- 21.

- I actively seek additional safety information to compensate for any educational gaps.

Appendix B.2.7. Stress

- 22.

- High levels of stress impact my ability to focus on safety measures.

- 23.

- Stressful situations lead to lapses in safety protocols on the construction site.

- 24.

- I find stress management techniques useless for accident prevention and maintaining safety.

Appendix B.2.8. Lack of Experience

- 25.

- Experience has made me more vigilant about potential safety hazards.

- 26.

- I think experience has little or no impact on safety understanding.

- 27.

- I actively share my experience with coworkers to enhance safety awareness.

- 28.

- I consider experience as important as formal training in safety practices.

Appendix B.2.9. Attention to Safety

- 29.

- I occasionally find myself not paying full attention to safety procedures.

- 30.

- I find it unnecessary to consciously focus on safety during routine tasks.

Appendix B.3. Single-Choice Questions

Instruction: Please choose one answer for each question.

- 1.

- I forget important safety steps even when I know them.☐ Never ☐ Rarely ☐ Sometimes ☐ Often ☐ Very Often

- 2.

- I get distracted and miss safety signs or warnings on site.☐ Never ☐ Rarely ☐ Sometimes ☐ Often ☐ Very Often

- 3.

- I start a task and realize later I skipped a safety check.☐ Never ☐ Rarely ☐ Sometimes ☐ Often ☐ Very Often

- 4.

- I sometimes use the wrong tool or equipment by mistake.☐ Never ☐ Rarely ☐ Sometimes ☐ Often ☐ Very Often

- 5.

- I lose track of what I was doing during a task.☐ Never ☐ Rarely ☐ Sometimes ☐ Often ☐ Very Often

- 6.

- I misunderstand instructions and perform a task incorrectly.☐ Never ☐ Rarely ☐ Sometimes ☐ Often ☐ Very Often

References

- Choi, S.; Guo, L.; Kim, J.; Xiong, S. Comparison of Fatal Occupational Injuries in Construction Industry in the United States, South Korea, and China. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2019, 71, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Fatal Occupational Injuries in Construction; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics: Suitland, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Health and Safety Executive (HSE) UK. Workplace Fatal Injuries in Great Britain 2023/24; Health and Safety Executive (HSE) UK: Bootle, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhry, R.; Fang, D. Why Operatives Engage in Unsafe Work Behavior: Investigating Factors on Construction Sites. Saf. Sci. 2008, 46, 566–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, M. A Cognitive Model of Construction Workers’ Unsafe Behaviors. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2016, 142, 4016039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ye, G.; Xiang, Q.; Yang, J.; Miang Goh, Y.; Gan, L. Antecedents of Construction Workers’ Safety Cognition: A Systematic Review. Saf. Sci. 2023, 157, 105923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Heerim, L.; Sungjoo, H.; June-Seong, Y.; Son, J. Construction Workers’ Awareness of Safety Information Depending on Physical and Mental Load. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2022, 21, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Ye, G.; Shen, L. Unveiling the Mechanism of Construction Workers’ Unsafe Behaviors from an Occupational Stress Perspective: A Qualitative and Quantitative Examination of a Stress–Cognition–Safety Model. Saf. Sci. 2022, 145, 105486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Peng, R.; Pan, Y. A Cognitive Failure Model of Construction Workers’ Unsafe Behavior. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 2022, 2576600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Zhu, H.; Peng, R.; Pan, Y. Development and Validation of a Cognitive Model-Based Novel Questionnaire for Measuring Potential Unsafe Behaviors of Construction Workers. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2021, 28, 2566–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reason, J. Human Error: Models and Management. BMJ 2000, 320, 768–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shappell, S.A.; Wiegmann, D.A. The Human Factors Analysis and Classification System—HFACS; U.S. Department of Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kines, P.; Andersen, L.P.S.; Spangenberg, S.; Mikkelsen, K.L.; Dyreborg, J.; Zohar, D. Improving Construction Site Safety through Leader-Based Verbal Safety Communication. J. Saf. Res. 2010, 41, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.; Lima, M.L.; Baptista, C. OSCI: An Organisational and Safety Climate Inventory. Saf. Sci. 2004, 42, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Fang, W.; Luo, H.; Zhong, B.; Quyang, X. A Deep Hybrid Learning Model to Detect Unsafe Behavior: Integrating Convolution Neural Networks and Long Short-Term Memory. Autom. Constr. 2018, 86, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Ding, L.; Luo, H.; Love, P.E.D. Falls from Heights: A Computer Vision-Based Approach for Safety Harness Detection. Autom. Constr. 2018, 91, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostofi, F.; Toğan, V.; Ayözen, Y.E.; Tokdemir, O.B. Construction Safety Risk Model with Construction Accident Network: A Graph Convolutional Network Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondia, A.; Moussa, A.; Ezzeldin, M.; El-Dakhakhni, W. Machine Learning-Based Construction Site Dynamic Risk Models. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 189, 122347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshram, K. Machine Learning Applications in Civil Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, B.; Xu, S.; Chen, L.; Niu, M. How Do Psychological Cognition and Institutional Environment Affect the Unsafe Behavior of Construction Workers?—Research on FsQCA Method. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 875348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Cai, Y.; Xie, L.; Pan, Y. Group Management Model for Construction Workers’ Unsafe Behavior Based on Cognitive Process Model. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 30, 2928–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajeri, M.; Ardeshir, A.; Banki, M.T.; Malekitabar, H. Discovering Causality Patterns of Unsafe Behavior Leading to Fall Hazards on Construction Sites. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2022, 22, 3034–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, N.; Jiang, Z.; Fang, D.; Anumba, C.J. An Agent-Based Modeling Approach for Understanding the Effect of Worker-Management Interactions on Construction Workers’ Safety-Related Behaviors. Autom. Constr. 2019, 97, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.; Kessler, M.L.; Riccobono, J.E.; Bailey, J.S. Using Feedback and Reinforcement to Improve the Performance and Safety of a Roofing Crew. J. Organ. Behav. Manag. 1996, 16, 49–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, R.; Wang, L.; Cao, L.; Zhang, B.; Yang, X. Psychosocial Factors for Safety Performance of Construction Workers: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 30, 944–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S. A Review of Social, Physiological, and Cognitive Factors Affecting Construction Safety. In Proceedings of the 36th International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction (ISARC), Banff, AB, Canada, 21–24 May 2019; pp. 317–323. [Google Scholar]

- van der Molen, H.; Koningsveld, E.; Haslam, R.; Gibb, A. Ergonomics in Building and Construction: Time for Implementation. Appl. Ergon. 2005, 36, 387–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbecq, A.L.; Van de Ven, A.H.; Gustafson, D.H. Group Techniques for Program Planning: A Guide to Nominal Group and Delphi Processes; Scott Foresman and Company: Glenview, IL, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques, 2nd ed.; John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Labour Force Survey 2020–21 (Annual Report); Pakistan Bureau of Statistics: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Naser, M.Z. Machine Learning for All! Benchmarking Automated, Explainable, and Coding-Free Platforms on Civil and Environmental Engineering Problems. J. Infrastruct. Intell. Resil. 2023, 2, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.