Abstract

Contemporary design of medical and therapeutic facilities increasingly recognizes that healing outcomes are influenced not only by functional performance but also by spatial experience, sensory perception, and atmospheric qualities of the built environment. Within this context, courtyards represent a recurrent architectural element in healthcare settings, historically associated with access to nature, daylight, ventilation, and social interaction. Beyond their utilitarian role, courtyards can operate as multisensory environments that support psychological regulation, emotional restoration, and physical well-being. This study investigates the therapeutic courtyard as a spatial component situated at the intersection of functional requirements and phenomenological experience in healing architecture. Rather than aiming to demonstrate universal applicability, the research seeks to identify and structure the key functional and phenomenological attributes that contribute to the restorative potential of courtyard spaces in healthcare environments. The study combines a structured literature review with an exploratory, perception-oriented survey based on conceptual courtyard scenarios. The research explicitly focuses on key spatial parameters of therapeutic courtyard design, including access to daylight, ventilation and microclimate, contact with nature, accessibility and orientation, social integration, opportunities for activity and recreation, possibilities for isolation and safety, adaptability and multifunctionality, as well as aesthetic and symbolic qualities. By translating theoretical insights into practical design considerations, the study contributes to the development of human-centered strategies for contemporary healing architecture.

1. Introduction

Healthcare environments are widely recognized as settings that generate heightened levels of psychological and emotional stress for patients, visitors, and healthcare professionals. In response, architectural research increasingly emphasizes the role of environmental qualities such as access to daylight, natural elements, and restorative outdoor spaces in mitigating stress and supporting recovery processes when these elements are meaningfully integrated into healthcare design [1]. Within this framework, the courtyard emerges as a significant spatial component of healing architecture, offering a transitional environment between interior clinical spaces and the natural world.

Previous studies have demonstrated that well-designed courtyards can support environmental legibility, sensory regulation, social interaction, and moments of refuge within otherwise demanding medical settings [1,2]. Through their spatial configuration, material expression, and relationship to nature, courtyards can influence users’ emotional states, perception of safety, and overall sense of comfort. Despite this recognized potential, the role of courtyards in contemporary healthcare architecture is often reduced to technical functions such as daylight provision or ventilation, while their experiential, atmospheric, and restorative qualities remain underdeveloped or insufficiently articulated in design practice [2].

This gap points to a broader limitation in current healthcare design discourse: although the therapeutic value of courtyards is frequently acknowledged, the specific architectural attributes that enable courtyards to function as genuinely restorative environments are rarely translated into explicit, practice-oriented design frameworks. In many contemporary hospital projects, courtyards remain residual spaces rather than intentionally designed healing environments capable of addressing the psychological and physiological needs of diverse users. In response to this limitation, the present study aims to systematically identify and structure the functional and phenomenological characteristics that contribute to the restorative potential of therapeutic courtyards in healthcare architecture. The research adopts a two-part methodological approach. First, a literature-based analytical framework is developed to distinguish key functional attributes (such as accessibility, microclimate regulation, and spatial organization) and phenomenological qualities (including sensory perception, atmosphere, and emotional response) associated with therapeutic courtyard spaces. Second, an exploratory survey is conducted among potential users of healthcare environments to examine how different conceptual courtyard scenarios are perceived and associated with the idea of a “therapeutic courtyard”.

In this context, the primary aim of the study is to identify, structure, and articulate the key spatial parameters that define therapeutic courtyard environments in healthcare architecture, translating functional and phenomenological attributes into a clear typological and design-oriented framework. On this basis, the study addresses the following research questions:

RQ1: Which functional architectural attributes are most frequently associated with the restorative potential of therapeutic courtyards in healthcare settings?

RQ2: Which phenomenological and atmospheric qualities characterize courtyards perceived as supportive of healing and well-being?

RQ3: How do users associate different spatial and environmental attributes with the concept of a therapeutic courtyard when evaluating conceptual design scenarios?

The originality of the study and its innovative contribution to the development of healing architecture lie in the formulation of a structured functional–phenomenological typology and in the comparative mapping of perceived regenerative qualities across different conceptual scenarios, rather than in clinical outcomes or effectiveness-based results.

By integrating theoretical analysis with perception-oriented exploration, the study seeks to translate abstract concepts of healing, atmosphere, and experience into concrete architectural design attributes. The resulting typological framework and design guidelines are intended to support architects and designers in the creation, evaluation, and refinement of therapeutic courtyards in both new and existing healthcare facilities.

2. Materials and Methods

The research methodology followed a structured, multi-stage process designed to identify, organize, and evaluate the restorative attributes of therapeutic courtyards in healthcare environments. A combination of qualitative and analytical methods was employed, including a structured narrative literature review, interpretative inquiry, comparative analysis, a scenario-based survey, and a research-through-design approach. These methods were applied sequentially, with each stage informing the next, in order to establish a coherent and reproducible research framework linking theory, design exploration, and user perception.

The literature review was conducted as a structured narrative review rather than a formal systematic review. Sources were identified primarily through targeted searches in Google Scholar. Key publications were selected through title and abstract screening followed by full-text reading of the most relevant sources. The review focused mainly on the literature published between the early 1990s and 2025 addressing therapeutic courtyards, healing gardens, therapeutic landscapes, biophilic design, and phenomenological approaches to space.

The literature review established the conceptual baseline of the study by identifying functional and phenomenological attributes associated with courtyard spaces across historical, environmental, and architectural contexts. These attributes were synthesized into an analytical framework that structured existing knowledge and guided subsequent stages of the research. This framework is developed in detail in the following section, which examines the therapeutic courtyard as a healing environment through functional and phenomenological dimensions.

Building on this theoretical foundation, a research-through-design phase was conducted to operationalize the identified attributes into a set of conceptual courtyard design scenarios. These scenarios were intentionally developed as conceptual and non-realistic visual representations, aimed at isolating and communicating specific spatial and atmospheric characteristics rather than depicting fully resolved architectural proposals. The visual material was therefore used as an analytical tool to support comparative perception, not as evidence of architectural performance.

The visual scenarios were generated using Midjourney, with prompts developed and refined by the author based on the literature review. For each scenario, a limited number of variations were produced, from which the final images were selected by the author. Minor perspective refinements and visual simplifications were subsequently made using Google Gemini. No extensive post-processing of color, lighting, or contrast was applied beyond the inherent characteristics of the AI-generated images.

Efforts were made to maintain a comparable visual language across scenarios in terms of scale, daylight presence, and degree of connection to outdoor environments. Nevertheless, AI-generated imagery may inherently introduce stylistic biases (e.g., cinematic lighting or lush vegetation), which could influence participants’ preferences and are therefore acknowledged as a limitation of the study.

The inclusion of non-courtyard spaces was intended to broaden the comparative reference frame rather than to minimize aesthetic bias.

The primary purpose of the survey was to explore perceived associations between courtyard design strategies and restorative qualities, rather than to measure clinical outcomes or establish causal relationships. The survey was conducted among potential users of healthcare environments, including individuals with everyday experience of such spaces as patients or accompanying visitors. Respondents evaluated exemplary design concepts of selected healing spaces through a scenario-based and perception-oriented questionnaire, focusing on impressions of calmness, comfort, and perceived restorative potential.

The survey deliberately employed scenarios representing various zones within healing environments, rather than courtyards alone, so that the visual research material functioned as an analytically stimulating prompt rather than merely a set of representative courtyard designs. The inclusion of different spatial types was intended to broaden the comparative reference frame; however, potential visual style and aesthetic biases cannot be fully excluded and are therefore acknowledged as a limitation of the study. Consequently, the study explored tendencies in how participants associate both functional and phenomenological spatial attributes with restorative qualities.

The survey therefore serves as a supportive tool for exploring perceptual tendencies rather than for establishing evaluative or causal findings. The identification of key spatial parameters based on the survey results enables the development of typological frameworks for therapeutic spaces, which constitutes the primary scientific contribution of the study. In this way, the survey functioned as an exploratory component supporting the broader design-oriented aims of the research, complementing the literature-based analysis and contributing to the synthesis of design guidelines presented in Chapter 5.

3. The Idea of Therapeutic Courtyard

Courtyards are among the most enduring spatial archetypes in architectural history, defined as open-to-sky spaces enclosed wholly or partially by surrounding built forms [2]. Originating in hot-arid regions as passive cooling devices, they have been adapted across diverse climates and cultural contexts for their environmental, social, and experiential benefits [2,3]. Over time, the courtyard evolved from simple inward-facing layouts to more varied configurations responding to local climatic needs and spatial functions. Despite these variations, it remains a widely recurring and multifunctional architectural element capable of enhancing comfort, supporting social life, and enriching sensory experience.

Courtyards have also long been associated with passive environmental regulation, including daylight access, ventilation, and microclimatic moderation, which contribute to user comfort and perceived well-being [2,3,4].

Building on these inherent advantages, the concept of a therapeutic courtyard emerges when a traditional courtyard is deliberately shaped as a healing environment within a healthcare context. In hospitals, hospices, and other medical facilities, such spaces are not merely decorative additions but are conceived as healing gardens or therapeutic landscapes that support patient outcomes and overall well-being [4,5]. The underlying premise is that contact with nature and access to calm outdoor environments are widely associated with reduced stress and supportive recovery conditions, complementing medical treatment rather than replacing it [6].

A therapeutic courtyard therefore intentionally adapts these qualities to the needs of patients, families, and staff experiencing elevated levels of physical and emotional strain. From the perspective of cultural geography and environmental psychology, such spaces may be understood as therapeutic landscapes, in which healing processes are influenced not only by physical conditions but also by symbolic meaning, social interaction, and psychological experience [4]. Contemporary healthcare architecture increasingly acknowledges that stress regulation, perceived autonomy, and positive distraction are shaped by environmental qualities, leading to a growing integration of nature-rich courtyards into healthcare design practice [7,8].

Therapeutic courtyards must nevertheless respond to the specific needs of their users and institutional contexts. A small, quiet garden designed for post-operative patients differs in character and program from an activity-oriented courtyard within a rehabilitation unit or a secure outdoor space in a psychiatric facility. What unites these variations is not a single formal solution but a shared intention: to support health and well-being through spatial conditions that foster comfort, orientation, and psychological relief. Access to a courtyard can offer hospital users an opportunity to step outside the clinical interior, regain a sense of control and normality, and engage with restorative environmental qualities [8].

3.1. The Courtyard as an Element of Healthcare Architecture

Courtyards and gardens have long been embedded in healthcare architecture. Medieval monastic hospices and early hospitals frequently incorporated cloister gardens or planted courtyards, reflecting an early recognition that contact with nature may support the well-being of the sick [5]. In the second half of the twentieth century, however, many hospitals shifted toward technologically driven and clinically focused designs. Green spaces were often reduced, neglected, or converted into parking and service areas, producing sterile institutional environments that prioritized hygiene and efficiency over human comfort [1]. In recent decades, this tendency has been reassessed. Evidence-based design research, including Ulrich’s influential studies on the relationship between views of nature and patient recovery, has demonstrated that environmental features such as gardens are associated with measurable improvements in health-related outcomes, including stress reduction and patient satisfaction [6,9]. As a result, courtyards and healing gardens are increasingly being reintegrated into new and renovated hospitals as fundamental components of the therapeutic environment rather than incidental amenities [8,10].

Within contemporary healthcare campuses, courtyards are now recognized as multi-purpose therapeutic assets. For patients, they provide opportunities to step away from the ward, where access to daylight, fresh air, and natural scenery can alleviate the monotony and psychological strain of clinical interiors [6]. Families and visitors may use these spaces for privacy, reflection, or conversation away from the bedside, while staff rely on them for restorative breaks that are widely associated with reduced burnout and improved work satisfaction [11]. Studies comparing healthcare facilities with abundant greenery to those with limited access to natural elements report higher satisfaction levels among both patients and staff in the former [11]. Thus, courtyards are increasingly understood as integral components of the therapeutic milieu, supporting clinical objectives by enhancing perceived comfort, trust, and overall experience of care [10].

The incorporation of courtyards is often addressed during the earliest planning stages of healthcare facilities. In large hospital complexes, multiple courtyards may be employed to limit building depth, improve access to daylight and natural ventilation, and establish legible circulation structures [3]. In some healthcare systems, such as in Malaysia, courtyards are explicitly referenced in design guidelines as passive strategies for climate regulation and wayfinding [3]. Contemporary hospitals also experiment with hybrid outdoor spaces such as hospital parks, rooftop gardens, and atrium gardens that extend the traditional notion of the courtyard and contribute to more humane and socially engaging environments [12]. Pediatric hospitals frequently integrate play elements and interactive art into courtyard spaces [13], while psychiatric facilities emphasize secure yet normalized outdoor environments that are associated with reduced agitation and improved mood [13]. In many mental health design guidelines, access to outdoor space is now regarded as a basic requirement for inpatient care [14]. Hospital administrators increasingly regard healing gardens and courtyards as components of patient-centered care rather than optional amenities. Post-occupancy evaluations consistently identify access to green spaces as a major contributor to satisfaction and perceived quality of care [6]. Investments in courtyards, rooftop gardens, and indoor planting are therefore framed as part of broader service-quality and well-being strategies [8,10,15]. This approach aligns with biophilic design principles, which associate reconnection with nature through courtyards, daylight, views, and natural materials with positive effects on health, well-being, and user experience [16,17]. In this light, the courtyard has re-emerged as a critical element of healthcare architecture, valued for both its architectural role and its therapeutic potential.

3.2. Functional Features of the Therapeutic Courtyard

The functional features of a therapeutic courtyard refer to concrete design elements and operational qualities that directly support health, healing, and everyday use. A key functional role relates to stress reduction and recovery support. Ulrich’s research demonstrated that even passive visual contact with nature, such as views of trees from patient rooms, has been associated with shorter postoperative stays and reduced demand for pain medication when compared to views of blank walls [9]. Therapeutic courtyards extend this principle by enabling both visual and physical access to greenery, providing forms of “positive distraction” that are widely associated with lower anxiety levels and supportive physiological regulation [6,7]. Reduced stress has been linked to changes in blood pressure, cortisol levels, and immune response, which may contribute to recovery processes [6,7]. Accordingly, a well-designed therapeutic courtyard prioritizes safe, convenient, and regular access to natural elements for patients during their stay. A second functional role concerns the facilitation of physical activity and rehabilitation. Courtyards can function as active therapeutic settings where patients engage in light exercise, physiotherapy, or simple walking. Design features such as level paths, handrails, resting points, and clear visual boundaries support safe movement for users with varying physical abilities [5,18]. Studies indicate that landscape features encouraging physical activity increase the use of outdoor hospital spaces among patients, staff, and visitors, while participation in “green exercise” has been associated with improved mental well-being compared to comparable indoor activities [18,19]. In rehabilitation contexts, courtyard gardens may be integrated into occupational therapy programs, using varied path textures, gentle slopes, or horticultural tasks to support the recovery of strength, balance, and coordination [5]. Therapeutic courtyards must also meet fundamental functional requirements related to safety, accessibility, and comfort. Proximity to patient areas, barrier-free access for wheelchairs and hospital beds, and the minimization of physical or symbolic thresholds that discourage use are essential considerations [5]. In mental health facilities, secure boundaries, anti-ligature fixtures, and tamper-resistant landscaping enable outdoor access while maintaining safety [14]. Comfort-related attributes such as adequate shade, varied seating options, protection from noise and undesirable views, and appropriate lighting strongly influence whether the space is actually used [3,18]. Research emphasizes that when basic needs related to comfort, safety, and accessibility are not satisfied, therapeutic intentions often remain unrealized because users avoid the courtyard altogether [1,18]. Functional benefits also extend into psychological and social domains. The opportunity to choose whether and how to use an outdoor space can restore a sense of autonomy for patients who may experience reduced control during hospitalization [8]. Providing spatial options such as shaded and sunny areas or individual and group seating supports this perception of choice. Courtyards further facilitate social support by offering informal meeting places for families and friends, as well as settings for small-group therapy or communal activities [10,20]. In mental health contexts, access to normalized outdoor spaces has been associated with reduced agitation and shorter inpatient stays [14]. Healthcare staff similarly benefit from access to greenery for breaks, which has been linked to reduced stress, lower mental fatigue, and decreased burnout risk [21,22,23]. As these factors influence patient satisfaction and perceived quality of care, therapeutic courtyards may also contribute to institutional performance indicators [6,11,24]. While further research is required to quantify economic impacts, existing studies suggest that courtyard interventions can be cost-effective by supporting recovery processes and improving overall user experience [5,6,11,17].

3.3. Phenomenological Features of the Therapeutic Courtyard

Phenomenological features refer to the ways in which users subjectively experience courtyard spaces through sensory perception, emotional response, and personal meaning. From this perspective, a therapeutic courtyard is not only a functional outdoor room but also an atmospheric environment capable of shaping mood, perception, and self-awareness [25,26]. Phenomenological qualities thus contribute to transforming a merely usable garden into one that is perceived as genuinely restorative.

Multi-sensory engagement constitutes a central dimension of this experience. As emphasized by Pallasmaa, healing environments should address the full sensorium rather than privileging vision alone [25]. In therapeutic courtyards, carefully orchestrated sensory cues such as the sound of water, the rustling of leaves, plant fragrances, tactile material qualities, and the dynamic interplay of light and shadow can create calming and immersive atmospheres. These stimuli are associated with micro-restorative experiences, in which attention is gently drawn toward natural elements and momentarily diverted from pain, anxiety, or cognitive fatigue [6,20]. Case studies on sensory therapeutic gardens highlight the importance of elements that can be seen, smelled, touched, and interacted with, particularly for users with cognitive, emotional, or psychological vulnerabilities [20].

Atmosphere and the notion of “spirit of place” play an equally significant role. As Zumthor observes, architecture can evoke immediate emotional responses through the interaction of scale, materiality, light, and sound [26]. In therapeutic courtyards, these qualities often contribute to perceptions of safety, calmness, and dignity. The sense of refuge created by enclosure being spatially defined by surrounding walls while remaining open to the sky can foster feelings of protection without confinement. This condition corresponds with environmental psychology theories of prospect and refuge, as articulated by Appleton, which suggest that environments balancing openness (prospect) and enclosure (refuge) are associated with enhanced perceptions of safety, orientation, and psychological comfort [27].

Users frequently describe hospital gardens as spaces in which they feel temporarily “away” from the clinical environment while remaining physically within the healthcare setting [5,8,14]. This perceived sense of escape and autonomy has been identified as a recurring theme in qualitative studies of hospital green spaces [8] and is associated with emotional relief and psychological restoration. Visual and aesthetic qualities further shape phenomenological impact. Natural material palettes, layered vegetation, and carefully composed focal elements such as a tree, sculpture, or water feature can support contemplation, reinforce continuity, and evoke feelings of hope [22,28]. Research on hospital gardens has identified attributes such as tranquility, mystery, and tactile richness as relevant to perceived restorativeness [1]. Features that invite gentle exploration, including curved paths or partially concealed views, may stimulate curiosity in a non-threatening manner and support mindful engagement with the environment.

Therapeutic courtyards may also carry symbolic and existential meanings. They are often interpreted as spaces representing life, growth, or renewal in contrast to the vulnerability and uncertainty associated with illness [4,5,25]. Open views toward the sky can reconnect users with natural rhythms of time and weather, counteracting the sense of temporal disorientation that hospitalization may produce [25]. For some users, the courtyard becomes a place of reflection or spiritual solace a “healing landscape” in Gesler’s sense where cultural, symbolic, and personal meanings converge [4,5,14]. Although these symbolic and emotional dimensions are difficult to quantify, they are frequently documented in qualitative accounts from patients, families, and healthcare staff.

3.4. Comparative Summary of Functional and Phenomenological Features of Therapeutic Courtyards

Therapeutic courtyards operate through two complementary dimensions: functional performance and phenomenological (experiential) quality. The functional dimension concerns practical and operational attributes that support everyday use and care-related activities, including accessibility, safety, climatic comfort, and opportunities for physical and social engagement [6,9,14,18]. Empirical studies indicate that such functional characteristics are associated with reduced stress indicators, improved staff recovery during breaks, and more supportive patient experiences, with effects often assessed through usage patterns, satisfaction surveys, or selected physiological measures [9,14].

In contrast, phenomenological features relate to subjective experiences shaped by atmosphere, sensory richness, emotional resonance, and symbolic meaning [8,25]. Users frequently describe therapeutic courtyards as places in which they feel calmer, more autonomous, or temporarily “outside” the hospital environment despite remaining within the healthcare setting [8,14]. These experiential qualities such as tranquility, beauty, intimacy, or a sense of refuge are typically captured through qualitative feedback and are essential in defining the courtyard as a genuinely restorative environment.

A comparative perspective illustrates how functional and phenomenological dimensions must operate in parallel rather than in isolation. Accessibility versus a sense of escape represents a fundamental tension: functionally, the courtyard should be easily reachable from patient areas and circulation routes [5], while phenomenologically it should convey a perception of retreat or psychological distance from clinical interiors through enclosure, planting, or visual screening [8]. Similarly, climatic comfort versus atmosphere highlights the dual role of environmental control. Functional requirements such as shade, ventilation, and protection from adverse weather conditions support year-round usability [3]. At the same time, these elements filtered daylight, moving air, and natural sounds contribute to the formation of a coherent and calming atmosphere that supports restorative experience [1].

Another intersection emerges between activity support and meaningful engagement. Functional infrastructure, including walkways, seating, and rehabilitation zones, enables physical activity, therapy, and social interaction [18,20]. Phenomenologically, carefully articulated micro-spaces, sensory cues, and natural detail encourage contemplation, reflection, and mindful engagement with the environment [1,5]. A particularly sensitive balance exists between safety and security versus freedom and comfort, especially in psychiatric or high-security settings. While functional safety measures such as secure boundaries and anti-ligature fixtures are essential [14], their phenomenological impact must be carefully mitigated through planting, material choices, and spatial composition in order to avoid an institutional or restrictive atmosphere and to foster trust and psychological comfort [14].

The relationship between these two domains is mutually reinforcing. Functional features establish the conditions that enable therapeutic use, whereas phenomenological features provide the emotional and sensory qualities that make the courtyard experientially restorative. Courtyards that are functionally adequate but experientially weak may remain underused, while visually appealing spaces that lack access, shade, or safety fail to deliver therapeutic value. For this reason, the integration of functional and phenomenological considerations from the earliest design stages is essential. Previous studies emphasize that effective therapeutic courtyards emerge through interdisciplinary design approaches that align environmental performance with experiential and restorative qualities [3,17].

Biophilic design frameworks further reinforce this duality by integrating visual connections to nature (phenomenological), thermal and acoustic comfort (functional), natural materials (phenomenological), and opportunities for movement and social interaction (functional) as key parameters of healing environments [16,29]. When these elements are coherently combined, the courtyard functions not only as an outdoor extension of healthcare infrastructure but also as a restorative setting that supports calmness, orientation, and emotional well-being.

In summary, functional features ensure usability, safety, and comfort, while phenomenological features shape perception, meaning, and emotional response. Both dimensions are indispensable for the design of therapeutic courtyards that contribute holistically to health and well-being (Table 1).

Table 1.

A comparative analysis of the functional and phenomenological attributes of the courtyard in the context of healing architecture.

4. Survey, Results, and Discussion

4.1. Overview of the Survey

To explore the factors shaping perceptions of therapeutic courtyards including spatial structure, visual characteristics, and restorative qualities a questionnaire-based survey was conducted. The purpose of the survey was not to evaluate clinical effectiveness, but to examine how potential users of healthcare environments associate specific spatial atmospheres with the idea of a “therapeutic courtyard.” Participants included individuals with everyday experience of healthcare settings, such as patients and accompanying visitors, and the survey adopted a scenario-based, perception-oriented approach.

Participants were recruited through the author’s academic and personal networks in Poland and Turkey. The survey was distributed online via Google Forms and participation was voluntary and uncompensated. No formal screening criteria were applied beyond the assumption that all respondents could be considered potential users of healthcare environments. This sampling approach allows for broad perspectives but also implies a self-selection bias, which is acknowledged as a limitation.

Based on the literature review and the analytical framework developed in the preceding sections, ten conceptual design scenarios were prepared. These scenarios represent a range of spatial conditions, from interior and semi-open transitional environments to fully open courtyards incorporating vegetation and water elements. Each scenario was intended to emphasize particular functional and phenomenological attributes identified in the literature.

The online survey was completed by 113 participants representing diverse age groups and genders, with varied everyday experiences of healthcare environments. Each respondent evaluated all ten visual scenarios and was asked to indicate which environments they perceived as most comfortable, visually engaging, or emotionally supportive. The assessment was guided by two general questions:

- (1)

- “Which visual atmosphere would you prefer to experience during or after a visit to a healing or healthcare center?”

- (2)

- “Which image evokes the most comforting, calming, or inspiring feeling for you?”

Participants were asked to select one single image only; multiple selections or ranking were not permitted. No open-ended responses were collected in order to maintain a visually focused and simple evaluation task. All participants viewed the images in the same fixed order. The survey was administered using Google Forms.

Rather than measuring objective performance, these questions were designed to capture associations between spatial atmosphere and perceived restorativeness, allowing insight into how users intuitively relate different spatial configurations and their functional and phenomenological features to the concept of a therapeutic environment.

All ten design concepts employed in the survey are presented in Table 2. The characteristics of visual scenarios that received the highest level of preference (three spatial scenarios selected by the respondents), together with their functional and phenomenological attributes in relation to distinctive spatial features, are presented in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 2.

Different spatial scenarios shown to respondents during the study.

Table 3.

Characteristics of design concept 4: Vintage Apartment Courtyard.

Table 4.

Characteristics of design concept 5: Green Courtyard.

Table 5.

Characteristics of Design Concept 6: Zen Garden.

4.2. Results

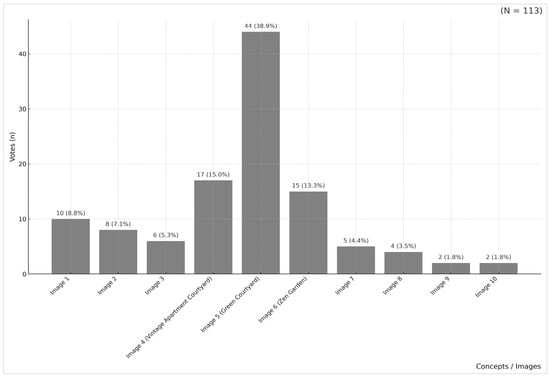

The survey results indicate discernible patterns in how participants associate different spatial environments with restorative qualities. While vote distribution provides an initial quantitative overview, the interpretation of the results focuses primarily on the spatial and experiential attributes characterizing the most frequently selected concepts.

Among the ten visual scenarios evaluated (N = 113), outdoor and nature-dominant courtyard environments were selected more frequently than interior or semi-enclosed spaces. The Green Courtyard (Design Concept No. 5/Image 5) received the highest number of selections with 44 votes (38.9%), followed by the Vintage Apartment Courtyard (Design Concept No. 4/Image 4) with 17 votes (15.0%) and the Zen Garden (Design Concept No. 6/Image 6) with 15 votes (13.3%) (Figure 1). Together, these three scenarios account for approximately 68% of all responses, suggesting a strong association between restorative perception and open-air, biophilic environments.

Figure 1.

Survey results for 10 visual concepts.

Rather than interpreting these results as a simple preference for “outdoor space,” a closer examination of the design characteristics summarized in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 reveals recurring patterns across the highest-ranked concepts. The most frequently selected courtyard environments share several common functional and phenomenological attributes: (i) high biophilic intensity expressed through dense vegetation, water elements, and natural textures; (ii) a clearly defined spatial center that supports orientation, grounding, and perceptual stability; and (iii) a balanced relationship between refuge and openness, allowing users to experience a sense of protection while maintaining visual and sensory connection with the surrounding environment.

In contrast, interior environments such as therapy rooms, lounges, and reading corners received substantially fewer selections, with individual results ranging between 1.8% and 8.8% (Figure 1). This distribution suggests that participants tend to associate restorative qualities more strongly with environments that provide direct or semi-direct contact with natural elements and outdoor atmospheric conditions.

Importantly, the survey results should not be interpreted as reflecting aesthetic preference alone. Instead, they point toward a perceived interaction between spatial structure, environmental comfort, sensory richness, and symbolic meaning. The alignment between quantitative selection patterns (Figure 1) and the qualitative attributes identified in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 supports the interpretation that perceived restorative potential emerges from the integration of functional and phenomenological features rather than from isolated spatial qualities.

4.3. Discussion

The survey results indicate that participants clearly value the combination of functional and phenomenological qualities in therapeutic courtyards. The most frequently selected concepts the Green Courtyard, the Zen Garden, and the Vintage Apartment Courtyard were associated with calmness, clarity, emotional grounding, and sensory comfort. These responses support existing findings in environmental psychology, which emphasize the restorative role of natural light, vegetation, water elements, and spatial enclosure in stress reduction and emotional regulation.

Across the preferred concepts, participants tended to favor environments that balance openness with a sense of refuge. Features such as open sky exposure, filtered daylight, natural movement, and clear spatial organization were perceived as calming and supportive. At the same time, respondents valued practical aspects such as ease of navigation, comfortable seating, and a recognizable spatial center. Spaces described as visually cluttered, overly enclosed, or artificial were consistently less preferred, suggesting that therapeutic courtyards are expected to support both visual comfort and intuitive use.

Participants’ descriptions further highlight this integration. Functional qualities such as “fresh air,” “freedom,” and “quiet” were frequently mentioned alongside phenomenological attributes such as “soft light,” “calming colors,” and “intimate atmosphere.” This indicates that restorative value is not linked to function or atmosphere alone, but to their combination.

Insights from a professional consultation with a clinical psychologist support this interpretation. Although not constituting clinical evidence, this perspective suggests that environments offering autonomy, perceptual clarity, and moderated sensory stimulation may be perceived as supportive in stressful healthcare contexts. This consultation was informal and served only as contextual background. It did not form part of the formal research methodology and did not contribute to data analysis or clinical claims.

Overall, the findings show that therapeutic courtyards are perceived as most effective when functional performance and experiential quality operate together. Rather than serving only as aesthetic additions, courtyards function as spatial mediators that support both practical use and emotional well-being. Given the conceptual nature of the visual scenarios, the results should be interpreted as indicative of preferred spatial tendencies rather than as evidence of causal effects.

5. Guidelines for the Design and Redesign of Therapeutic Courtyards

Based on the survey findings, comparative spatial analyses, and phenomenological interpretation, a set of guidelines is proposed for the design and redesign of therapeutic courtyards in healthcare environments.

Historical precedents and contemporary user responses indicate that restorative courtyards benefit from a balanced relationship between openness and refuge. Preferred environments combine access to open sky and natural elements with spatial enclosure that provides psychological comfort. Courtyards offering a clear spatial center, layered boundaries, and gradual transitions support orientation and a sense of safety without creating feelings of isolation. Respondents consistently favored spaces that appeared usable, climatically comfortable, and easy to navigate. These results highlight the importance of treating greenery as an active spatial element, improving microclimatic comfort, ensuring universal accessibility, and providing a variety of quiet resting areas. Therapeutic courtyards should therefore function as genuinely usable outdoor rooms rather than purely decorative spaces.

The study also demonstrates the value of user-oriented visualization and scenario-based design methods in early planning stages. The visual concepts helped participants articulate preferences related not only to aesthetics but also to emotional safety, sensory comfort, and perceived restorative quality. Atmospheric representations such as light studies, material palettes, and spatial sequencing can support design decisions by translating experiential qualities into tangible spatial intentions and enabling early feedback from users and healthcare staff.

Two distinct yet complementary modes of thinking about the architecture of the therapeutic courtyard functional (usability and ergonomics) and phenomenological (spatial experience and sensory perception) can be translated into measurable design attributes in relation to the characteristic features previously identified and discussed.

- Access to daylight

Functional attributes

Courtyard size and shape ensure optimal daylighting, improving visibility and reducing energy consumption. Shading strategies such as light shelves or blinds minimize glare and distribute light evenly, supporting thermal comfort and circadian rhythms. Reflective materials and light-colored surfaces enhance lighting uniformity, facilitating navigation and therapeutic activities [41,42,43].

Phenomenological attributes

Light filtration through glazing or vegetation creates a soft, warm sensation, symbolizing safety and welcome. Access to views and prospect–refuge configurations strengthen the sense of relaxation, stimulating atmospheric perception and emotional grounding. Biophilic elements, such as green walls, integrate light with nature, contributing to a holistic spatial experience as a “protective inner shell” [20].

- 2.

- Ventilation and microclimate

Functional attributes

Courtyard shape and proportions can promote natural ventilation, reducing summer cooling loads and improving air exchange. Open windows facing the courtyard remove warm air and pollutants, lowering temperature and humidity for thermal comfort. Vegetated buffer zones stabilize the microclimate by controlling air movement and temperature [44,45,46].

Phenomenological attributes

Warm, still air creates a sense of enclosure and calm, acting as a protective “inner shell.” Vegetation regulates the microclimate through evaporation, enhancing biophilic connection to nature and relaxation. Gentle airflow stimulates atmospheric perception, supporting emotional grounding and a sense of refuge [45,46,47].

- 3.

- Contact with nature

Functional attributes

Indoor plants, vegetated buffer zones and water elements improve air quality, reduce stress, and support activities without external exposure. Natural materials such as wood and stone enhance usability by adding warmth and tactility for user comfort. Sensory paths and healing gardens enable safe interaction, promoting movement and social inclusion [48,49,50,51].

Phenomenological attributes

Greenery adds emotional softness, creating a symbolic bridge to nature and enhancing calmness. Views of vegetation and biophilic elements stimulate relaxation and improve mood. Holistic therapeutic gardens foster a sense of refuge, integrating nature into the spatial experience as a healing presence [48,50,52,53,54].

- 4.

- Accessibility and orientation

Functional attributes

Clear circulation paths and visual signage facilitate movement, reduce cognitive load, and support user independence. Flat, barrier-free surfaces, wide passages, and tactile elements (e.g., textured flooring) ensure accessibility for people with disabilities, enabling safe therapeutic activities. Strategic landmarks, such as a central courtyard, clarify spatial layout and minimize disorientation.

Phenomenological attributes

The courtyard’s central position as a reference point builds a sense of control and safety, symbolizing an archetypal refuge. Subtle visual and spatial cues (e.g., curved walls guiding the gaze) stimulate intuitive perception, enhancing emotional grounding. The holistic composition of forms and materials creates a welcoming atmosphere in which orientation becomes part of the therapeutic spatial experience.

- 5.

- Social integration

Functional attributes

Shared seating arrangements in semi-private zones enable brief, non-intrusive interactions without crowding, supporting waiting and group activities. Flexible, reconfigurable furniture and wide circulation paths accommodate diverse user groups, promoting accessibility and equitable participation. Central communal nodes with clear visibility lines clarify social dynamics and reduce barriers to engagement.

Phenomenological attributes

Holistic spatial composition creates hospitable atmospheres that symbolize harmony and invite emotional connection among users. Subtle biophilic elements and warm materials foster a sense of shared refuge, enhancing collective calmness and mutual empathy. Intuitive layout cues stimulate perceptual awareness of others, building archetypal feelings of community as therapeutic enclosure.

- 6.

- Activity and recreation

Functional attributes

Multi-functional zones with reconfigurable furniture enable diverse activities (e.g., exercise, relaxation) tailored to various user groups. Wide, flat paths and buffer zones ensure safe movement and accessibility, minimizing injury risks during recreation. Central nodes with flexible surfaces (e.g., lawns or mats) support group sessions and occupational therapy without spatial constraints [55].

Phenomenological attributes

Varied surface forms and textures stimulate sensory perception, creating spatial experiences that invite movement and exploration. Natural gradients from open centers to intimate niches form archetypal activity rituals, enhancing agency and emotional grounding. Biophilic element compositions integrate recreation with holistic nature perception as a therapeutic refuge.

- 7.

- Isolation and safety

Functional attributes

Enclosed boundaries with controlled entries (e.g., gates or fencing) prevent escapes and unauthorized access, ensuring safety for vulnerable groups. Soft surfaces and rounded edges minimize injury risks, enabling safe activities without physical barriers. Visual surveillance systems and buffer zones clarify sightlines, reducing anxiety and supporting independence.

Phenomenological attributes

Curved walls and intimate niches create an archetypal “inner refuge,” symbolizing protection and fostering a sense of security. Warm materials and external stimulus filtration shape atmospheric perception as a stable protective shell, enhancing emotional soothing. Holistic spatial composition isolates users from external chaos, integrating the experience as a therapeutic sanctuary.

- 8.

- Adaptability, flexibility, and multifunctionality

Functional attributes

Modular furniture and movable partitions enable reconfiguration of zones for group, individual, or therapeutic activities, adapting to changing user requirements. Multi-functional surfaces (e.g., lawns with mats or raised beds) accommodate both recreation and sensory therapy without fixed spatial limitations. Flexible lighting and shading systems regulate environmental conditions, optimizing comfort for different times of day and age groups.

Phenomenological attributes

Variable compositions of forms, materials, and colors stimulate perception of space as living and responsive, fostering engagement and personal action. Spatial gradients from open centers to intimate niches create archetypal adaptation rituals, enhancing emotional grounding through discovery. Holistic, multi-layered biophilic elements integrate diverse sensory experiences into a therapeutic spatial narrative.

- 9.

- Beauty, aesthetics, and symbolism

Functional attributes

Harmonious compositions of forms and colors enhance visual orientation, reduce cognitive load, and facilitate navigation. Natural materials (e.g., wood and stone) add warmth and tactility, increasing comfort during therapeutic activities. Aesthetic uniformity minimizes disorientation, supporting inclusion and the effectiveness of group sessions [56,57,58].

Phenomenological attributes

Integrated aesthetics create symbolic harmony, expressing hospitality and therapeutic beauty while reducing tension. Subtle form gradients and biophilic elements stimulate perception of healing spatial narratives. Holistic symbolism such as the central courtyard as refuge builds archetypal experiences of sanctuary and emotional resonance [56,57,58].

6. Conclusions

This study positions the therapeutic courtyard as a spatial system defined by a set of key architectural parameters rather than as a purely aesthetic or symbolic element of healthcare design. Through a combined functional and phenomenological analysis grounded in the literature and supported by a perception-oriented survey, the research identifies recurring measurable spatial parameters that shape restorative courtyard environments, including access to daylight, ventilation and microclimate, contact with nature, accessibility and orientation, social integration, opportunities for activity and recreation, possibilities for isolation and safety, adaptability and multifunctionality, as well as aesthetic and symbolic qualities. These parameters form the core of the proposed typological framework and provide a structured basis for design decision-making in contemporary healing architecture.

Overall, the findings support the understanding of therapeutic courtyards as meaningful and adaptable spatial components within healing architecture. By systematically relating user preferences to clearly defined functional and phenomenological parameters, the study contributes to ongoing discussions on how architectural space can support health, well-being, and recovery. Future research may further strengthen this approach through empirical post-occupancy evaluations, controlled environmental measurements, and expanded interdisciplinary collaboration.

In conclusion, the study contributes to the field of healing architecture not through clinical or effectiveness-based evidence, but by articulating a coherent functional–phenomenological typology and by offering a comparative synthesis of perceived regenerative qualities across distinct conceptual design scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.T. and A.J.; methodology, B.T. and A.J.; validation, B.T. and A.J.; formal analysis, B.T. and A.J.; investigation, B.T. and A.J.; resources, B.T. and A.J.; data curation, B.T. and A.J.; writing—original draft preparation, B.T. and A.J.; writing—review and editing, B.T. and A.J.; visualization, B.T.; supervision, A.J.; project administration, B.T. and A.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All collected data are fully presented within the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of visualizations, the authors used Google Gemini (image generation, version 3) to refine and structure the prompts written for Midjourney. The images for the survey were generated using the subscription version of Midjourney. After generation, the authors used Google Gemini again to make perspective and visual adjustments to the resulting images. All AI-generated outputs were manually reviewed and edited by the authors, who take full responsibility for the final content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cervinka, R.; Röderer, K.; Hämmerle, I. Evaluation of hospital gardens and implications for design: Benefits from environmental psychology for architecture and landscape planning. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2014, 31, 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Almhafdy, A.; Ibrahim, N.; Ahmad, S.S.; Yahya, J. Analysis of the courtyard functions and its design variants in Malaysian hospitals. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 105, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat Idris, M.; Sibley, M.; Hadjri, K. The architects’ and landscape architects’ views on the design and planning of hospital courtyard gardens (HCG) in Malaysia. Plan. Malays. 2022, 20, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesler, W.M. Therapeutic landscapes: Medical issues in light of new cultural geography. Soc. Sci. Med. 1992, 34, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, C.C.; Barnes, M. Gardens in Healthcare Facilities: Uses, Therapeutic Benefits, and Design Recommendations; The Center for Health Design: Concord, CA, USA, 1995; Available online: https://www.healthdesign.org/sites/default/files/Gardens%20in%20HC%20Facility%20Visits.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Ulrich, R.S. Health Benefits of Gardens in Hospitals. In Plants for People, International Exhibition Floriade. 2002. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/252307449_Health_Benefits_of_Gardens_in_Hospitals (accessed on 20 January 2026).

- Sternberg, E. Healing Spaces; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Weerasuriya, R.; Henderson-Wilson, C.; Townsend, M. A systematic review of access to green spaces in healthcare facilities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 40, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. View through a window. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, C.C. Healing gardens in hospitals. Interdiscip. Des. Res. E-J. 2007, 1, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sadatsafavi, H.; Walewski, J.; Taborn, M. Patient experience with hospital care—Comparison of a sample of green hospitals and non-green hospitals. J. Green Build. 2015, 10, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulakh, I. Perspective architectural techniques for the formation and development of public spaces in hospitals. Archit. Civ. Eng. Environ. 2021, 14, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Hu, D.; Shah, S.J.; Hu, X. A design-driven approach exploring therapeutic building–nature integration strategies in healthcare. Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2025, 18, 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, J.; Marques, B.; Jenkin, G. The role of courtyards within acute mental health wards: Designing with recovery in mind. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenberg, H. Interior Gardens: Designing and Constructing Green Spaces in Private and Public Buildings; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tekin, H.; Urbano Gutiérrez, A. Human-centred health-care environments: A new framework for biophilic design. Front. Med. Technol. 2023, 5, 1219897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieberler-Walker, K.; Desha, C.; Bosman, C.; Roiko, A.; Caldera, S. Therapeutic hospital gardens: A literature review and working definition. Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2023, 16, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, K.G.; Chien, H. The influences of landscape features on visitation of hospital green spaces—A choice experiment approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Sheffield, D. Green exercise and mental health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1176. [Google Scholar]

- Szabo, M.D.R.; Dumitras, A.; Mircea, D.-M.; Doroftei, D.; Sestras, P.; Boscaiu, M.; Brzuszek, R.F.; Sestras, A.F. Touch, feel, heal: The use of hospital green spaces and landscape as sensory-therapeutic gardens—A case study in a university clinic. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1201030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.; Yuan, J.; Arfaei, N.; Catalano, P.J.; Allen, J.G.; Spengler, J.D. Effects of biophilic indoor environment on stress and anxiety recovery: A between-subjects experiment in virtual reality. Environ. Int. 2020, 136, 105427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Liu, H.; Lu, H. Can even a small amount of greenery be helpful in reducing stress? A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichrowski, M.J.; Corcoran, J.R.; Haas, F.; Sweeney, G.; McGee, A. Effects of biophilic nature imagery on indices of satisfaction in medically complex physical rehabilitation patients: An exploratory study. Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2021, 14, 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallasmaa, J. The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zumthor, P. Atmospheres: Architectural Environments—Surrounding Objects; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Appleton, J. The Experience of Landscape; Wiley: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Pernão, J. Phenomenological colour surveys. J. Int. Colour Assoc. 2017, 19, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tekin, B.H.; Corcoran, R.; Gutiérrez, A.U. A systematic review and conceptual framework of biophilic design parameters in clinical environments. Health Environ. Res. Des. 2023, 16, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frandsen, A.K.; Mullins, M.; Ryhl, C.; Folmer, M.B.; Fich, L.B.; Øien, T.B.; Sørensen, N.L. Helende Arkitektur [Healing Architecture]; Institut for Arkitektur og Design Skriftserie Nr. 29; Institut for Arkitektur og Medieteknologi: Aalborg, Denmark, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Meir, I.A.; Pearlmutter, D.; Etzion, Y. On the microclimatic behavior of two semi-enclosed attached courtyards in a hot-dry region. Build. Environ. 1995, 30, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture; Rizzoli: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, P.; Sibley, M.; Hakmi, M.; Land, P. Courtyard Housing: Past, Present and Future, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verderber, S.; Fine, D.J. Healthcare Architecture in an Era of Radical Transformation; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bachelard, G. The Poetics of Space; New edition; Jolas, M., Translator; Penguin Classic: London, UK, 2014. First published 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Gesler, W. Healing Places; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Zolfagharkhani, M.; Ostwald, M.J. The Spatial Structure of Yazd Courtyard Houses: A Space Syntax Analysis of the Topological Characteristics of the Courtyard. Buildings 2021, 11, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elantary, A.R.; Alansari, A.; Alawirdhi, A. User’s perspective of landscape existence in healthcare buildings. HBRC J. 2021, 17, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engineer, A.; Ida, A.; Sternberg, E.M. Healing Spaces: Designing Physical Environments to Optimize Health, Wellbeing, and Performance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairuddin, N.L.; Denan, Z. Influence of central courtyard’s daylighting on visual comfort at Tamarind Square Selangor, Malaysia: A case study. Plan. Malays. 2025, 23, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirch, J. Spatial typologies in psychiatric facilities. Eur. Psychiatry 2023, 66, S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontadakis, A.; Tsangrassoulis, A.; Doulos, L.; Zerefos, S. A Review of Light Shelf Designs for Daylit Environments. Sustainability 2018, 10, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Luo, F.; Wang, W.; Hong, T.; Fu, X. Performance-Based Evaluation of Courtyard Design in China’s Cold-Winter Hot-Summer Climate Regions. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadatjoo, P.; Badamchizadeh, P.; Mahdavinejad, M. Towards the new generation of courtyard buildings as a healthy living concept for post-pandemic era. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 97, 104726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Jimenez-Bescos, C.; Mohammadi, M.; Zhong, F.; Calautit, J.K. Numerical Investigation of the Influence of Vegetation on the Aero-Thermal Performance of Buildings with Courtyards in Hot Climates. Energies 2021, 14, 5388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apolonio Callejas, I.J.; Cleonice Durante, L.; Diz-Mellado, E.; Galán-Marín, C. Thermal Sensation in Courtyards: Potentialities as a Passive Strategy in Tropical Climates. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewska-Guizzo, A.; Fogel, A.; Escoffier, N.; Sia, A.; Nakazawa, K.; Kumagai, A.; Dan, I.; Ho, R. Therapeutic Garden With Contemplative Features Induces Desirable Changes in Mood and Brain Activity in Depressed Adults. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 757056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Iperen, I.D.; Maas, J.; Spronk, P.E. Greenery and outdoor facilities to improve the wellbeing of critically ill patients, their families and caregivers: Things to consider. Intensive Care Med. 2023, 49, 1229–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, R.; Chen, C.; Matsubara, T.; Hagiwara, K.; Inamura, M.; Aga, K.; Hirotsu, M.; Seki, T.; Takao, A.; Nakagawa, E.; et al. The Mood-Improving Effect of Viewing Images of Nature and Its Neural Substrate. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajchman-Świtalska, S.; Zajadacz, A.; Lubarska, A. Therapeutic Functions of Forests and Green Areas with Regard to the Universal Potential of Sensory Gardens. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2021, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillmann, T.A.; Marques, P.O.; Mattiuz, C.F.M. Therapeutic gardens: Historical context, foundations, and landscaping. Ornam. Hortic. 2024, 30, 242740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConatha, J.T.; Ford, K.; Cusmano, C.; Lyman, N.; McConatha, M. The Healing Power of Green Spaces: Combating Loneliness, Loss, and Isolation. Int. J. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2023, 7, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, D.; Forde, D.; Sharma, C.; Deutsch, J.M.; Bruneau, M., Jr.; Nasser, J.A.; Vitolins, M.Z.; Milliron, B.-J. Interactions with Nature, Good for the Mind and Body: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrot, G. Symultaniczność i kompilacja a obraz miejsca. Bud. Archit. 2018, 18, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawlak, A.; Stankiewicz, M. Specific Needs of Patients and Staff Reflected in the Design of an Orthopaedic and Rehabilitation Hospital Design Recommendations Based on a Case Study (Poland). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fronczak, M. Architektura inspirująca. Budynki w przestrzeni publicznej w narracji z współczesnym odbiorcą. Przestrz. Urban. Archit. 2022, 2, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaglarz, A. Color as a Key Factor in Creating Sustainable Living Spaces for Seniors. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.