Abstract

Counterintuitively, carbon risks—including investments in net-zero emissions-enabling technologies, legacy assets, insurance costs, and regulatory and compliance expenses—can be managed through rapid decarbonisation, as the built environment sector prepares for a transition to a low-carbon economy. This paper uses a bottom-up approach to net-zero emissions modelling to discuss an accelerated emissions reduction pathway while targeting both net-zero operational and embodied carbon emissions for commercial buildings. It also explores the link between built environment-related policy frameworks and technological advancements aimed at decarbonising commercial buildings, along with an initial effort to improve their energy resilience. For the commercial building archetype, achieving the net-zero operational emissions goal by 2035 appears practical, as energy intensity can be reduced sharply from around 120 kWh/m2 to nearly 75 kWh/m2 between 2025 and 2035. However, achieving net-zero embodied emissions appears practically challenging, as concurrent policies are at early stages, navigating the embodied carbon emissions data, reporting, and disclosure aspects. Regulatory mechanisms that require the disclosure of both embodied emissions data and actions and progress aligned with the dedicated targets and caps allocated to the real estate sector can assist commercial buildings in delivering on the whole-of-life net-zero emissions targets and commitments.

1. Introduction

1.1. Carbon Risks Associated with Commercial Buildings’ Operation

The built environment sector faces two major challenges amid urgent concerns about climate change. First, it must reduce resource consumption and greenhouse gas emissions to mitigate climate change. Second, it needs to identify and manage climate-related risks while enhancing resilience through adaptation strategies. These dual challenges cover the climate change impact spectrum. Climate-related risks generally fall into three main categories: physical, transition, and regulatory. However, transitions and regulatory risks are often bundled together. Physical risks relate to the potential impacts of climate-induced hazards, such as extreme temperatures, droughts, floods, storms, heatwaves, and wildfires. Transition risks arise from climate change mitigation policies, technological advancements, and shifts in market preferences [1].

In the real estate sector, transition risk is often referred to as carbon risk, specifically, the risk to building owners from the transition to a low-carbon economy. The transition risk–carbon emission nexus is intuitive due to the climate-related financial damages and liability risks in high-emission scenarios [2,3]. Risk arises for real estate and commercial building owners, who face financial uncertainty due to a stringent regulatory environment, shifting investor preferences, stranded assets, and evolving customer needs [3]. Climate transition risks are directly linked to real estate portfolios and buildings’ carbon intensity (e.g., carbon emissions per square metre). Therefore, as part of minimising the impact of climate transition risks, the built environment sector must significantly reduce its carbon intensity to achieve net-zero emissions.

1.2. Why Do We Need to Manage Carbon Risks in Commercial Buildings?

Operating buildings in a fluctuating climate will remain challenging if we fail to keep climate change within the acceptable limit of around 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels. This limit is considered manageable in terms of impacts across sectors, including the built environment. The IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) detailed various Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) based on greenhouse gas (GHG) levels and radiative forcings (e.g., RCP2.6, RCP4.5, RCP6, and RCP8.5). The subsequent AR6’s Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) scenarios prioritise low-emission SSP1–1.9 and high-emission SSP3–7.0 for future climate risk analysis. Amidst diverse climate scenarios, the commercial building sector must reduce GHG emissions through acceptable decarbonisation pathways, creating transition risks [4].

Globally accepted frameworks, such as the Science-Based Target Initiative (SBTi) and Carbon Risk Real Estate Monitor (CRREM), along with IPCC and IEA scenarios, guide efforts to decarbonise buildings by 2050. Thus, commercial building owners should ensure that their real estate portfolio aligns with one of the decarbonisation pathways. Consequently, commercial buildings are required to rapidly reduce their GHG emissions under a more stringent policy and regulatory framework, as well as evolving technological and market conditions. Further, policy mechanisms in Australia’s built environment sector are increasingly addressing embodied carbon emissions, indicating increased carbon risks to commercial buildings over time.

A previous study [5] suggests regulatory and mandatory reporting of embodied carbon emissions in buildings. The Australian National Construction Code (NCC) includes energy efficiency performance requirements that also target reductions in GHG emissions. Although the embodied carbon challenges related to construction materials are not explicitly addressed in the 2022 NCC amendments, the building industry, market, and the policy environment (e.g., Sustainable Buildings State Environment Planning Policy, 2022) are evolving to promote the use of environmentally responsive materials that mitigate embodied carbon emissions [6,7]. Thus, it is reasonable to say that employing carbon risk management at the earliest point will reduce regulatory and transition costs for commercial building owners. However, it may initially increase costs, specifically for adopting low-carbon materials and products.

While carbon risks are inevitable throughout the pathway to achieve net-zero emissions, the question of how commercial buildings will achieve rapid decarbonisation, minimise carbon risks from the outset of the transition, and sustain progress under a more stringent regulatory and policy environment remains unanswered. This study aims to answer this question by using a bottom-up approach to net-zero emissions modelling to accelerate an emissions reduction pathway while targeting both net-zero operational and embodied carbon emissions. Furthermore, it explores the interface between policy and technological change aimed at the decarbonisation of commercial buildings, together with an early effort to improve commercial buildings’ energy resilience.

2. Rapid Decarbonisations in Commercial Buildings in Australia: How Practical Is It?

The Global Buildings Climate Tracker indicates that the current building sector’s decarbonisation progress between 2015 and 2022 is significantly below the anticipated progress measured by decarbonization points [8]. Thus, there is a need for rapid decarbonisation to address the emissions gap by making up for the lost progress throughout the rest of the building sector’s decarbonisation journey. Energy efficiency investments, green building certifications, and ambitious climate pledges for the building sector in nationally determined contributions (NDCs), as well as zero-emissions-aligned building codes, are highlighted as critical policy interventions to achieve an intermediate milestone of 4.4 GtCO2e/year by 2030 and the ultimate net-zero emissions target by 2050. These milestones align with the IEA’s Net-Zero Emissions scenario pathway. A sectoral approach to building sector decarbonisation allocates a sector-specific carbon budget, which can be downscaled to the single-building level using normalised metrics, such as kg CO2e/m2/year [9].

For Australia, Verikios et al. [10] modelled sectoral decarbonisation pathways, including the building sector, for two scenarios: global warming of less than 2 degrees and limited to 1.5 degrees. The built environment sector’s emissions (including residential and commercial buildings) in 2025 are estimated at around 78 MtCO2e/year, primarily from purchased electricity, with the remainder from Scope 1 emissions. In the two scenarios under investigation—net-zero by 2050 in the 2-degree global warming scenario and net-zero by 2040 in the 1.5-degree global warming scenario—the purchased electricity-related Scope 2 emissions are expected to decline rapidly, while Scope 1 emissions will decline slowly [10]. DCCEEW [11] estimated an emissions reduction potential of around 69% relative to 2005 levels by 2030. Another study by DCCEEW [12] projects emission reductions of over 63% by 2030 and 80% by 2050, even under a business-as-usual scenario. The emission decline projection attributes the reductions in the emission intensity of electricity consumption. Decarbonisation of the electricity sector is often mentioned as a solution to reducing emissions within commercial buildings. However, energy demand management measures, energy efficiency programmes for equipment, and energy efficiency improvements through specific requirements under the national construction code and sustainability rating systems (e.g., NABERS and CBD) are emphasised as Australia’s response to reducing emissions in the global stocktake [13].

The recent update to the trajectory for low-energy buildings in Australia [14] discusses challenges to emissions reduction in the Australian building sector, while also noting the possibility that the built environment sector could be decarbonised by 2040 [15]. The ‘Race to Net Zero Carbon’ report by Prasad et al. [15] offers a positive outlook for achieving net-zero operational carbon by 2030 and net-zero embodied carbon by 2040. The projection is made in light of recent emphasis on whole-of-life carbon standards, regulations, and reporting for the built environment sector. Technological changes, such as a suite of energy efficiency measures across the building system and on-site renewable energy generation, are presented as key strategies for achieving net-zero operational carbon. Likewise, low embodied carbon design principles, the use of recycled content materials, and a low-carbon supply chain are presented as key strategies for achieving net-zero embodied carbon. An inherent interplay between policy changes (e.g., standards and regulations) and the accompanying technological changes is being reconciled through the planned NCC update (2025), which adjusts design guidelines to reduce emissions. For example, NCC specifications for solar PV installations on all the available roof space and system size determination considering the amount of conditioned space, determination of the quantity of electric vehicle (EV) chargers, building envelope requirements (U-value, R-value, and solar admittance), electrification (reserved electrical capacity and space hot water circulation system changes), and fans efficiency [16]. Likewise, the upcoming NCC (2025) update will establish a voluntary pathway for commercial buildings to report embodied carbon emissions.

Collectively, regarding the recent building sector decarbonisation pledges via NDCs [13], the anticipated emissions reduction pathway, as indicated by the recent update to the trajectory for low-energy buildings in Australia [14], and the planned reforms to the NCC substantiate the policy shift for an accelerated emission reduction in commercial buildings. The policy shift, however, focuses more on net-zero operational emissions. This is also evident in Australia’s long-term emissions reduction plan [17], which identifies net-zero operational emissions in the building sector as a key priority. Net-zero embodied emissions in the building sector receive little attention. However, on the production side, efforts are made through research, development, and promoting low-carbon concrete. Nonetheless, the long-term emissions reduction plan earmarks the building sector as the one with 100% deep emissions reduction potential, given the deployment of policies and emerging technologies.

Recent studies in an Australian context, such as that by Allen et al. [18], indicate that achieving net-zero operational and embodied emissions by 2050 is feasible with ambitious actions, while embodied emissions and carbon sequestration remain potential leverage points for accelerated emission reductions. Likewise, Craft et al. [19] highlight the critical role of embodied carbon emissions. These studies concur with Prasad et al.’s [15] finding about the challenge posed by embodied emissions to achieving a net-zero future in the Australian built environment. Thus, there appears to be a disconnect between the existing policy focus, which sees embodied emissions as voluntary for now, and the growing call for greater focus on net-zero operational emissions in the Australian built environment. Nonetheless, accelerated decarbonisation appears possible, though there is a need to align the existing policy focus with increased efforts in the embodied emissions space, as identified by the local Australian built environment literature.

3. Methodology

3.1. Commercial Office Building Archetype and the Quantifiable Characteristics

The functionality and general characteristics of buildings are key qualifiers for their categorisation as one of commercial office, residential, or warehouse buildings. Building characteristics and functionality provide input parameters for building energy modelling, which can be achieved by constructing a building archetype to represent a specific building stock [20]. Archetypal Building Energy Modelling (ABEM) is prevalent in building energy research, as it generalises building representations in an abstract way; it performs well when the typology is standardised, reflecting the diversity of buildings [21]. In Australia, building types are standardised through the NCC classification system (ABCB, 2025). A study by Bell et al. [22] uses the National Australian Built Environment Rating System (NABERS) to identify the reference building energy performance of the commercial office building stock and to build the standard building template. Baniya and Giurco [23] refer to the NCC and the condition of the existing commercial office building stock to define the building characteristics of the commercial office building archetype. This ABEM method aligns with the bottom-up approach discussed by Prasad et al. [15], which focuses on various building parameters and components to provide an overall understanding of energy consumption and the potential for net-zero operational emissions at the specific building stock level.

This study uses the building archetype representing NCC class 5 buildings [24], which are commercial office buildings in an urban area (Sydney, Australia). This method of selecting archetypes corresponds to the ‘estimated building archetype’ category in building energy modelling and is common for residential and office buildings because of their suitability for micro-scale research [21]. The ‘estimated building archetype’ is usually a virtual model built to represent quantifiable characteristics. Table 1 shows the key characteristics of the building archetype located in Sydney. The climate zone is ‘Zone 5’, which is warm and temperate. Other Australian metro cities with a similar climate zone are Perth and Adelaide. Thus, the selection of ‘Zone 5’ is reasonable, as it covers fractional parts of four Australian states: Western Australia (WA), South Australia (SA), New South Wales (NSW), and Queensland (QLD) towards the south-east. Further, NSW has a higher share of the national commercial building stock.

Table 1.

Key technical specifications of the building archetype.

Quantifiable building characteristics, such as floor area, Window-to-Wall Ratio (WWR), lighting density, and plug load density, are crucial input parameters for building archetype energy modelling. Therefore, data for these parameters are empirically derived. A study by Foo and Shen [25] found that the average WWR for low-rise commercial office buildings in Australia was 46%, ranging from 31% to 61% across the sampled buildings. A baseline survey of commercial buildings indicated that lighting density was around 10 W/m2 in 2022, decreasing by about 3.3% annually in Australia [12], and is projected to be approximately 9 W/m2 in 2025. Plug load density in commercial office buildings is around 17 W/m2, especially in conditioned office spaces [26]. However, it is significantly lower across corridors and shared spaces. Consequently, a plug load density of 15 W/m2 was adopted.

3.2. Net-Zero Transition and Accelerated Pathway Identification—Current Policy and Technology Drivers and Future Decarbonisation Scenarios

The built environment sector plan (2025), tied to Australia’s Net Zero Plan and the updated NDC (2025), provides a net-zero roadmap for the Australian building sector, including commercial buildings [27]. Likewise, the recent update to the trajectory for low-energy buildings and the upcoming changes in the NCC requirements focus on net-zero emissions, primarily covering operational emissions. Although the policy changes are not paradigmatic compared to their previous versions, the shift in their focus and drive to deploy technology at scale indicates teleological change with net-zero emissions as a clear goal. The inclusion of emerging technologies, such as digitalisation, that demand flexibility and low-emission products, together with an aim to reduce embodied carbon emissions, demonstrates a layered approach to policy changes. In this approach, new policy targets are built on previous ones, all part of the same overall goals. Figure 1 shows the most recent and key policy and technology focus pertaining to Australia’s built environment sector.

Figure 1.

Australia’s built environment-related policy and technological focus to enable net-zero emissions.

Furthermore, Australia’s long-term emissions reduction plan complements the policy and technology focus, as shown in Figure 1, by providing insights into technology pathways, trends, and deployment barriers. Building on the evidence that electricity consumption accounts for most commercial energy use, it predominantly emphasises high-efficiency appliances, lighting, equipment, and the building envelope, together with on-site renewable energy provisions (e.g., solar PV and battery storage). On the energy supply and building materials supply sides, it focuses on low-emissions electricity and low-emissions cement, respectively [17].

With the recent changes in the policy landscape, reflecting a clear policy focus and a technology deployment pathway to achieve net-zero emissions, it is reasonable to infer that the quantifiable building characteristics will change over time (lighting and plug load densities, and U and R values). Likewise, the building energy asset type and its ecosystem (e.g., heat pumps, solar PV, and battery storage, along with their connections and digitalisation) are likely to change as both market-matured and emerging technologies are rapidly deployed. While the changes can be evolutionary, accelerated emissions reductions require rapid, radical changes in quantifiable building characteristics and the energy assets ecosystem. Thus, this study proposes a two-stage net-zero transition objectives and an accelerated pathway to achieve the net-zero emissions goal: the Transitional Decarbonisation Goal (By 2035) and the Whole-of-life Net-Zero Emissions Goal (By 2040).

3.2.1. Transitional Decarbonisation Goal (By 2035) Scenario

The initial goal is to achieve significant decarbonisation, including interim net-zero operational emissions and progress towards net-zero embodied emissions, within the next 10 years by 2035. This does not represent a full lifecycle net-zero emissions state; hence, it is termed a transitional decarbonisation goal. As illustrated in Figure 1, recent policy shifts, technological progress, and upcoming deployment are expected to support the ‘Transitional Decarbonisation Goal (By 2035)’. Large-scale deployment of technologies, such as on-site solar PV and battery storage, along with grid decarbonisation, will reduce emissions from purchased electricity, a primary source in commercial buildings. Solar PVs and battery storage systems are auto-sized by the building simulation software using the least-cost method. Moreover, energy efficiency retrofits, certification initiatives, improved energy ratings for buildings and appliances, and the NCC’s efficiency standards will lower lighting, plug loads, and HVAC energy use, further reducing emissions. In this scenario, the lighting and plug load densities are adjusted based on their annual improvement rates and slightly elevated performance. Electrifying buildings with heat pumps (auto-sized) and increasing the use of electric vehicles (EVs) will also help cut fossil fuel consumption and related emissions. The number of modelled EV chargers is four (150 kW each), as this number is reasonable for the ‘On-Demand’ EV charger type to service an EV fleet (around 12 EVs). Together, these measures support achieving net-zero operational emissions. By 2035, greater emphasis will be placed on embodied carbon, with commercial buildings required to report and disclose embodied carbon emissions. Furthermore, small-scale projects using low-emission materials will be encouraged to reduce upfront embodied emissions, depending on market readiness. These efforts lay the groundwork for the Whole-of-life Net-Zero Emission Goal By 2040.

3.2.2. Whole-of-Life Net-Zero Emissions Goal (By 2040) Scenario

Upon achieving the Transitional Decarbonisation Goal By 2035 across building operations, this stage aims to achieve whole-of-life net-zero emissions by 2040 while ensuring energy resilience and demand flexibility in buildings through connected energy assets, digitalisation, and adaptive reuse and renovation. The early stage interventions, primarily based on low-emission materials, are to be followed by full-scale building refurbishment and fit-out projects that rely solely on low-emission materials to reduce upfront embodied carbon emissions. The embodied emissions accounting and disclosure set a normative process for identifying upfront embodied carbon emissions reduction areas within buildings, for example, across substructures and superstructures, roofing, and internal finishes. Further, the embodied emissions accounting method is structured to capture at least the following information for the process-based bottom-up approach: material categories and their masses, and their share of embodied emissions.

3.3. Building Energy Simulation and Modelling for Operational Energy Analysis

The main goal of the building energy simulation is to use the quantifiable building characteristics of the building archetype to define the structure of energy consumption and operational emissions. OpenStudio is a tool for building simulation as it uses EnergyPlus as the energy modelling engine, has a simple interface to accept the quantifiable building characteristics, and the simulated results have been tested with metered data, confirming the validity with an acceptable level of gap [28,29,30]. Building characteristics data, as presented in Table 1, were input data in addition to the Typical Meteorological Year (TMY) weather file in the EnergyPlus file format. The TMY weather file was sourced from CSIRO’s AgData Shop [31]. Previous studies by Bamdad et al. [32] and Baniya and Giurco [33] used the same data source to build energy simulations of Australian buildings across different climate zones. The TMY data are based on historical weather data collected from 1990 to 2015. The underlying building energy simulation provided total energy consumption and its decomposition by end use, including gas consumption for space heating and cooling, electricity for space heating and cooling, lighting, and other electrical loads associated with energy-consuming equipment and appliances. This underlying energy model is marked as ‘Base Case (2025)’ and serves as a benchmark for operational energy and emissions in 2025.

Another building energy simulation model, marked as ‘Transitional Decarbonisation Goal (By 2035)’, was created to factor in potential policy and technological shifts and their implications for quantifiable building characteristics and the building energy asset ecosystem. This reflects the scenario explained in Section 3.2 and, specifically, in Section 3.2.1. The lighting and plug load densities were adjusted, given the recent annual decrease in Australia for commercial buildings. Likewise, gas-fired space heating and cooling systems were replaced with equivalent electric systems. Other adjustments included optimising the infiltration flow rate and the thermal conductivity values of the building materials. These changes were reflected in the OpenStudio software, which yielded different simulated energy consumption and a different structure of the energy-consuming entities.

For changes in the energy supply system, such as the provision of solar PV and battery storage systems, and the electrification of the fleet, this study uses HOMER Grid software. It is appropriate to optimise the sizes of the solar PV and battery energy storage systems (BESS), and, hence, the cost, depending on the quantity and structure of energy consumption. Another upside to using HOMER Grid is that it can model the consumption of electric vehicle (EV) chargers. Thus, HOMER Grid was chosen over similar tools such as REopt, DER-CAM, and TRNSYS. The validity of HOMER Grid results has been discussed in previous studies, such as those by Vargas-Salgado et al. [34] and Baniya and Giurco [33]. HOMER Grid requires electricity tariff data that must be constructed based on the local tariff structure. For this study, the electricity tariff structure for commercial building customers in Sydney is used.

OpenStudio is used to estimate the ‘Base Case (2025)’ energy consumption and the ‘Transitional Decarbonisation Goal (By 2035)’ energy consumption. The latter accounts for energy efficiency improvements across space heating and cooling systems, lighting, and other electric loads. The resulting reduction in grid electricity purchases is also simulated in OpenStudio. Thus, one of the main outputs from OpenStudio is the ‘Transitional Decarbonisation Goal (By 2035)’ energy consumption, which HOMER Grid uses to estimate energy supply, optimise supply system capacities (e.g., Solar PV and BESS), and EV charger consumption for the ‘Transitional Decarbonisation Goal (By 2035)’ scenario. The grid electricity purchase reduction is critical, as HOMER Grid uses the least-cost method to optimise the capacity of the on-site generation system, and because of space constraints. Most commercial buildings may not have sufficient space to fit an oversized solar PV system. The shortfall between electricity supplied by the optimised on-site generation system and the building’s electricity consumption is met by grid electricity, which is GreenPower due to its near-zero emissions factor.

For energy resilience analysis, this study uses the built-in function, ‘Outages’, module in HOMER Grid. This module can model both stand-alone and multiple grid outages and test the building’s energy resilience to sustain critical load (CL) during power outages, which is 10% of the peak electricity load. The CL is allocated reasonably, in line with standard practice for sustaining emergency lighting and IT systems, and the life safety and security systems during power outages. Although the CL can be kept as high as 25%, the installation cost, ongoing maintenance expenditure of the power backup system, and the minimal use in a typical year (e.g., less than 1 per month) in commercial building settings are reasons for inputting the CL as 10% in the ‘Outages’ module in HOMER Grid. The share of the critical load ranges from 10% to 25% of the peak load, depending on the building typology and operating scale. For example, Marqusee et al. [35] use the terminology ‘top priority critical load’, which is around 10% of the peak load. Likewise, Baniya and Giurco et al. [33] analyse cost-effective building microgrid components, with the CL as 10%. For demand flexibility analysis, this study uses the ‘Demand Response Program’ module in HOMER Grid. A fraction of demand reduction (5% of the non-critical load) is the input data, together with the anticipated number of demand response events and event duration (2 h). These input parameters generate results for the demand response simulation. The diesel generator-based power backup system in ‘Base Case (2025)’ is replaced with a battery storage system in the ‘Transitional Decarbonisation Goal (By 2035)’ scenario. Therefore, demand response simulation is performed separately for 2025 and 2035 for comparison.

3.4. Operational and Embodied Emissions Accounting and the Decarbonisation Pathway

Operational emissions primarily cover Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, such as those associated with energy consumption (e.g., purchased electricity and natural gas). In comparison, embodied emissions pertain to Scope 3 emissions and are primarily linked to the use of construction materials in buildings (e.g., A1–A5), at least the major fraction of the Scope 3 emissions. For this study, the system boundary for operational emissions accounting is limited to the building energy system, and the system boundary for embodied emissions accounting is confined to the construction materials’ remit.

For the 2025 Base Case operational emissions, the ‘national greenhouse gas accounts factors: 2025’ provide energy-related emission factors [36]. This source is reliable and is used for reporting under the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting (NGER) Act 2007. In the ‘Transitional Decarbonisation Goal (By 2035)’ scenario, grid emission factors are obtained from the Carbon Risk Real Estate Monitor (CRREM) platform, which provides Australia’s future grid emission factor, including specific data for New South Wales (NSW), where Sydney is located. Using CRREM’s grid emission factor is appropriate, as this study employs the CRREM risk assessment tool and decarbonisation pathway. Natural gas and related operational emissions are not modelled in the ‘Transitional Decarbonisation Goal (By 2035)’ scenario, due to the expected gas-to-electric assets transition. Operational emission reduction potential is estimated by considering on-site generation solutions (such as solar PV and batteries) and offsets from GreenPower purchases.

CRREM’s decarbonisation pathway methodology uses a top-down approach, starting from the global carbon budget aligned with the 1.5-degree scenario [37]. This budget is then downscaled to a specific building type: a commercial office building in this study. The carbon budget is converted into a carbon intensity metric, kgCO2e/m2/year, which standardises data across commercial office buildings of varying sizes. While an energy intensity pathway offers an alternative, a carbon intensity pathway was chosen due to the expected structural changes in energy consumption, supply systems, and grid decarbonisation between the Base Case (2025) and the ‘Transitional Decarbonisation Goal (By 2035)’. CRREM’s pathway considers only operational emissions, excluding embodied emissions. Additionally, the goal of net-zero whole-of-life emissions is set for a later year, so it is reasonable to address embodied emissions separately in this study.

Among the three methods for calculating embodied emissions in buildings—process-based, input–output (IO)-based, and hybrid-based—as outlined by Cang et al. [38] and Elkhayat et al. [39], the process-based approach was selected for this study. This method employs a bottom-up approach and is most widely used due to its micro-level focus on buildings and high-impact material categories [40]. It aligns well with the Embodied Carbon in Construction Calculator (EC3) tool used for this study, enabling users to input specific material properties, including emission factors and verified environmental product declarations (EPDs). Although the local embodied emissions database (e.g., EPiC [41]) provides localised coefficients for Australia, the EC3 is suitable for its use of third-party-verified EPDs, signifying its commercial relevance. Further, for generic commercial building archetype modelling, the EC3 may not always require a detailed bill of quantities. EPiC data appeared to be more suitable for identifying and comparing with low-carbon material alternatives. A key limitation of the EC3 is its emphasis on superstructure—covering walls, roof structures, surfaces, and internal finishes. Despite this focus, the EC3 is effective for establishing baseline embodied carbon emissions due to the significant share of embodied emissions attributable to these components. Like other embodied carbon calculation tools, it can estimate the upfront emissions for new construction and major renovations. Generally, for the process-based method, the upfront embodied emissions across N material categories are calculated using Equation (1). The system boundary for the embodied emissions assessment covered the upfront embodied carbon (e.g., A1–A5 modules, including product and construction phases), which contributes to a significant fraction of the building’s whole-of-life embodied emissions.

4. Results

4.1. Operational Energy End-Use Decomposition and Greenhouse Gas Emissions

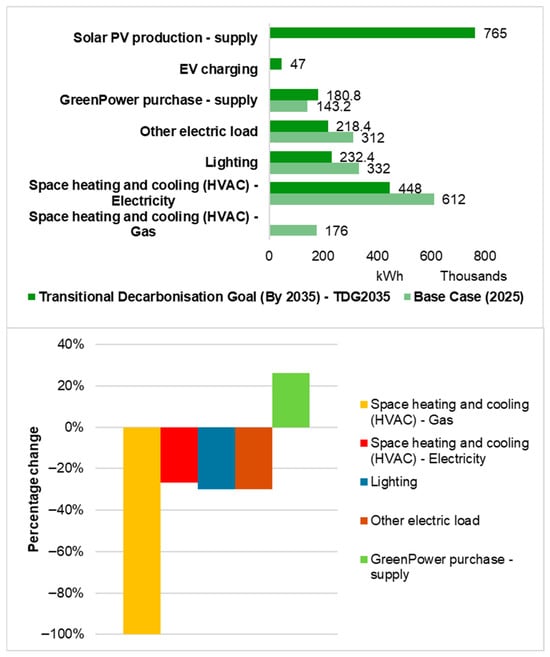

Figure 2 shows changes in the operational energy end-use structure between 2025 and 2035, the year when the transitional decarbonisation goal is achieved. The gas consumption for space heating and cooling becomes absolute zero due to the gas-to-electric asset transition, and, hence, the percentage change is −100%. This puts pressure on grid electricity consumption, especially for space heating and cooling. However, counterintuitively, grid electricity consumption for space heating and cooling decreases between 2025 and 2035. Collectively, the efficient heat pump with a COP of three that replaces the gas-fired heater, scheduled adjustments in HVAC setpoint temperatures, improvements in the thermal conductivity of insulation and building envelope materials (almost 7% reduction in thermal conductivity), and increased fan efficiency by calibrating the flow rate (16 m3/s to 12 m3/s) and pressure rises (up to 200 Pa) reduce the HVAC electricity consumption. These are key areas of energy efficiency in buildings that current policies (see Figure 1) aim to deliver. For the building archetype chosen for this study, grid electricity use-efficiency improvements yield almost 25% savings in electricity consumption in 2035 compared to 2025. This saving (25%) is reasonable, as the commercial building archetype (Table 1) has only one gas heater to replace with an electric heat pump, which complements two other packaged electric heat pumps. Baniya and Giurco [30] suggest that energy efficiency improvements in buildings are the priority for technology deployment, especially if the goal is to reduce capital investments in on-site energy assets and to enable buildings’ energy resilience.

Figure 2.

Changes in the operational energy end-use structure between 2025 and 2035.

As the policies recommend (Figure 1), lower lighting and plug densities, achieved through the deployment of efficient lighting and the implementation of minimum efficiency standards for appliances, result in almost 30% energy efficiency improvements between 2025 and 2035 (Figure 2). In the ‘Transitional Decarbonisation Goal (By 2035)’ scenario, the on-site solar PV and battery storage system provides a significant fraction of electricity to complement grid electricity, given that the roof space can accommodate a solar PV system with a capacity of around 450–500 kW. However, the on-site renewable energy system is insufficient to meet all electricity demand, necessitating a higher share of GreenPower purchases, which increase by almost 24% to achieve the Transitional Decarbonisation Goal (By 2035).

Overall, electricity consumption decreases by nearly 35%, aligning with the ‘trajectory for low-energy buildings’ update (2025). The technologies supporting the low-energy buildings concept are among the key future innovations in the building sector to accelerate the energy transition [42], for example, efficient appliances and equipment, building microgrids, and advancements in artificial intelligence and digitalisation. While the operational decarbonisation pathway seems straightforward, Kuru et al. [43] observed that Australian commercial office buildings have certain decarbonisation gaps to address for steady progress. This highlights the need to bridge the perceived policy-based decarbonisation pathways and the real decarbonisation pathway that commercial office buildings will follow, adopting concurrent technologies. Improvements are also measured by reducing energy intensity from roughly 120 kWh/m2 to nearly 75 kWh/m2 between 2025 and 2035. This pertains to the higher building energy rating (e.g., NABERS and CBD) that policies (Figure 1) aim to achieve.

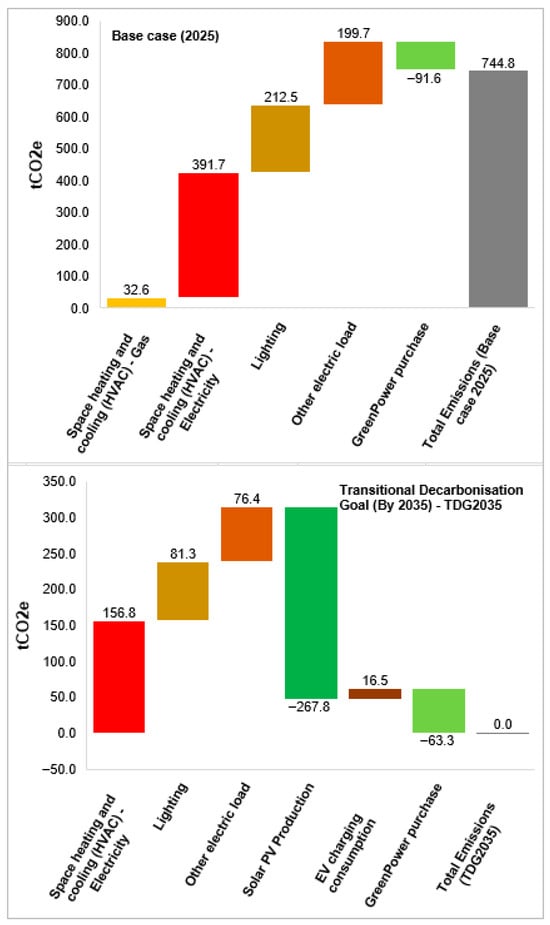

Figure 3 illustrates how sources of operational emissions shift across building operations to achieve the ‘Transitional Decarbonisation Goal (By 2035)’. Energy efficiency improvements are often limited to reaching a certain efficiency level, beyond which gains become incremental. Therefore, the technological advances in the energy system support the transition towards net-zero operational emissions, with solar PV and battery storage systems covering a significant portion of the energy supply. Future net-zero buildings typically include a combination of solar PV, battery storage, and EV chargers [44]. Although some studies [45,46] highlight the potential of hydrogen technologies (e.g., fuel cells and generators) to complement battery storage systems, they face practical challenges related to maintenance, operations, and higher operational costs.

Figure 3.

Operational emission changes between 2025 and 2035.

Greening the fleet with EVs appears sustainable from an energy supply perspective, but they consume additional electricity, either from the grid or on-site generation, potentially requiring additional GreenPower. GreenPower is preferred, considering that grid decarbonisation progresses rapidly between 2025 and 2035, which is an essential condition to leverage the benefits of electrification for emissions across building operations [47]. The integration of EVs and EV chargers within a building’s connected energy asset system is also seen as an opportunity to leverage advancements in vehicle-to-building (V2B) and vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technologies—both of which support building energy resilience. V2G, coupled with on-site battery storage systems in commercial buildings, is found to support demand-side flexibility, energy resilience, and operational decarbonisation objectives [33,48].

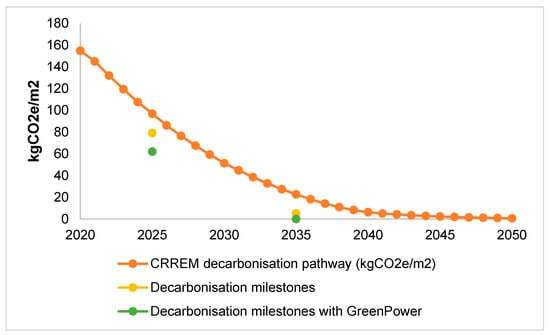

Figure 4 shows the operational decarbonisation milestones the building archetype will achieve from 2025 to 2035 and compares them with the emission-intensity milestones in the CRREM decarbonisation pathway. The milestones for both 2025 and 2035 go beyond the prescribed emissions intensity for commercial buildings. While Australian commercial office buildings are far from achieving the ideal energy and emissions performance, recent government policies and market-driven mandates—such as stricter energy performance standards—have supported improvements. As a result, these decarbonisation targets are marginally better than the global average. The role of GreenPower is noticeable, given its low capital investment requirement and a shorter procurement and delivery timeline compared to other energy efficiency and renewable energy technologies.

Figure 4.

Net-zero operational emissions pathway using CRREM.

GreenPower, a market-based mechanism, is a bridging strategy compared to on-site initiatives, such as solar PV, BESS, and energy efficiency measures, and serves to address residual Scope 2 emissions. Residual Scope 2 emissions are a challenge for net-zero operational emissions, primarily because of three main reasons: first, the electrification of gas-using assets will offset a part of the energy efficiency gain across the HVAC system, lighting, and other electric loads; second, the use of EVs; and, finally, the space constraint to fit in sufficient solar PV panels to fully replace grid electricity. Thus, GreenPower appears to be a trade-off tool that could specifically neutralise the residual Scope 2 emissions from purchased electricity. As shown in Figure 3, the contribution of GreenPower towards achieving net-zero operational emissions would be significantly lower than that of other site-based direct interventions, such as on-site renewable energy generation and energy efficiency across key consumption areas. Nonetheless, despite its relatively lower contribution, GreenPower addresses a major caveat regarding space for solar PV installations and the related capital expenditure. Thus, it is not only one of the decarbonisation options but also an offset option that commercial building owners and operators may further explore as policies become more stringent on embodied emissions disclosure and reporting.

In essence, while GreenPower appears to be one of the central climate mitigation strategies for commercial building owners and operators, the overall sensitivity of the net-zero operational emissions to GreenPower would be on the lower side. First, as indicated by Figure 3, GreenPower’s emission reduction potential would be lower, conditional on the availability of sufficient on-site renewable energy generation and energy storage options, together with energy efficiency improvements. Second, there are alternatives to GreenPower, such as direct power purchase agreements with off-site renewable energy generators.

4.2. Energy Resilience and Demand Flexibility—Implications on the Operational Decarbonisation

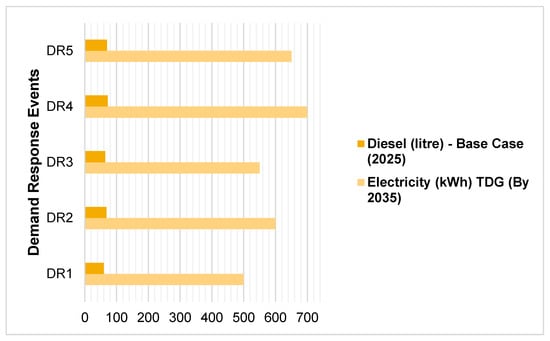

Figure 5 shows the comparison of reductions in grid electricity purchases and diesel generator consumption across five demand response events per year, assuming a critical load of 10% of the peak load and that each demand response event lasts about 2 h. Demand flexibility in commercial buildings is an emerging technological and policy focus [49], mainly because it improves buildings’ energy resilience and the greater utility of on-site renewable energy systems, which replace diesel generators as backup power during power outages. Power backup systems in many commercial buildings rely on diesel generators, which must be phased out to achieve the ‘Transitional Decarbonisation Goal (By 2035)’. The demand response simulation shows that the operational emissions can be reduced by up to 2800 kgCO2e per year and by around 0.24 kgCO2e/m2 in terms of emissions intensity in 2035 compared to 2025. In the Base Case (2025), although the diesel generator can contribute to the demand response programme and ease pressure on the electricity grid, it will not avoid demand response event-related emissions. In comparison, the battery storage system of 600 kWh capacity (auto-sized in HOMER Grid) participates in demand response events under the ‘Transitional Decarbonisation Goal (2025)’ to achieve dual objectives: demand flexibility and operational emissions reduction. Figure 5 shows the quantity of diesel consumption in demand response events in the ‘Base Case (2025)’ and the battery throughput in ‘Transitional Decarbonisation Goal (2025)’.

Figure 5.

Operational energy implications of demand response events.

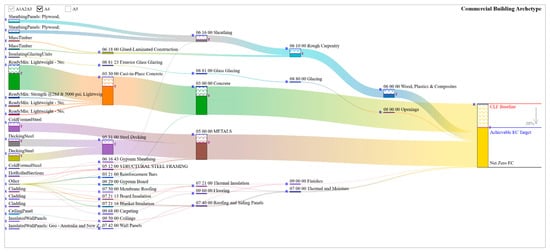

4.3. Upfront Embodied Carbon Reduction Potential and Contributions to the Whole-of-Life Net-Zero Emissions

The upfront embodied carbon emissions for construction materials in the commercial building archetype are shown in Figure 6, highlighting the importance of embodied carbon considerations in the design and construction phases. For an existing building, such as the commercial building archetype, the embodied carbon emissions are already locked in—a significant fraction of which can be hard to reduce during a refurbishment project. Collectively, the upfront embodied carbon emissions reduction potential by less than 40%, indicating that carbon offsets may be required to achieve net-zero embodied emissions for existing buildings. The embodied carbon intensity for the commercial building archetype is approximately 480 kgCO2e/m2, with construction materials accounting for the majority of this embodied carbon across the A1 to A5 modules. A study by Craft et al. [19] found the upfront embodied emissions of an Australian office building to be approximately 832 kgCO2e/m2 under a typical scenario when using the EPiC database, and approximately 520 kgCO2e/m2 when using the EPDs. For a LEED-certified public library building in the US, Cai et al. [50] found an embodied carbon emissions intensity of around 540 kgCO2e/m2, generated from sources such as construction materials and mechanical, plumbing, and electrical components. For existing office buildings, Elkhayat et al. [39] found an average embodied carbon intensity of 697 kgCO2e/m2.

Figure 6.

Upfront embodied carbon emissions (commercial building archetype).

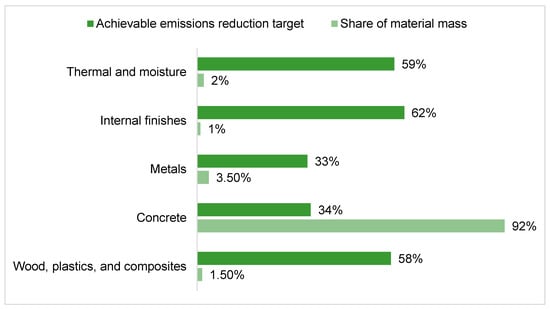

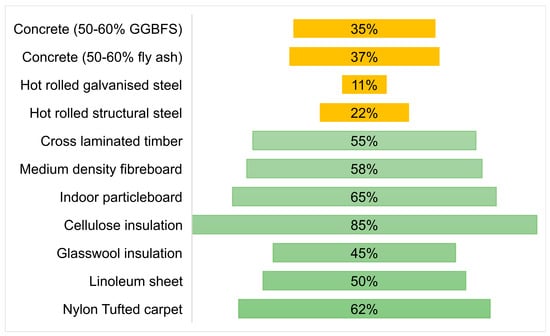

The achievable embodied emissions reduction depends on the material type and its mass (Figure 7). For example, concrete, with a much higher share of the total material mass, has a lower potential for embodied carbon emissions than internal finishes, insulation, and surface materials. A combination of concrete and metals contributes to almost 95% of the total material mass. However, the embodied carbon emissions reduction potential is less than 35% for each, meaning that almost 65% of upfront embodied carbon emissions are locked in throughout the lifecycle. By contrast, materials with relatively short service lives, such as insulation, internal finishes, and surface materials, can reduce embodied carbon emissions by more than 55% for each material type when considering the whole building lifecycle. Material substitution during fit-outs and refurbishment projects is an enabler of embodied carbon emission reductions (Figure 8), calculated as the difference between the embodied emissions of conventional materials and their low-carbon alternatives. Locally, the EPiC database [41] provides embodied emissions of some substitute materials. The lower embodied carbon emissions reduction potential of concrete and metals can be attributed to the substitute material’s embodied carbon emissions. For example, compared to ordinary concrete, the suitable alternative—concrete with ground-granulated blast furnace slag and fly ash—can reduce embodied carbon emissions by only around 35–37%. Market-ready alternatives to conventional insulation and surface materials also reduce embodied carbon emissions, with potential reductions of more than 50% for most materials.

Figure 7.

Share of material mass and achievable emissions reduction.

Figure 8.

Embodied emission reductions through material substitutions.

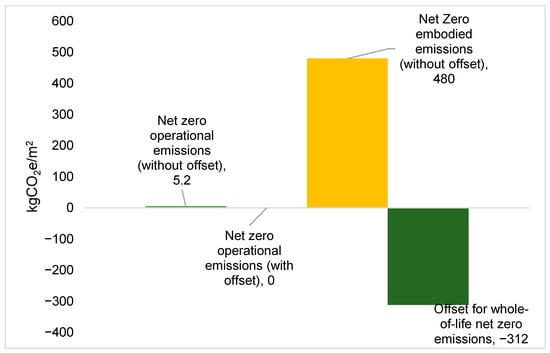

Although the embodied emissions can be reduced to some extent by using material substitution, depending on the material type and the frequency and scale of refurbishments, it does not appear to achieve net-zero embodied emissions by 2040 and beyond. Figure 9 shows that a massive amount of carbon offsetting (around 312 kgCO2e/m2) is required to achieve whole-of-life net-zero emissions. This residual embodied emission underscores the growing concern about the significant share of embodied emissions in the later phase of the building lifecycle. This, together with the complexity around embodied carbon emissions in existing buildings, raises questions about net-zero whole-of-life emissions. Thus, suffice it to say that future climate mitigation frameworks for the built environment sector will have to emphasise reductions in embodied carbon emissions. A larger part of the uncertainty associated with embodied carbon emissions can be reconciled during the operation and maintenance phase of existing buildings. Thus, specific climate mitigation strategies focused on refurbishment and renovation projects can partly offset the upfront embodied emissions. Further, as the policies (Figure 1) indicate, the accounting of embodied carbon emissions should prompt actions and offset strategies beyond GreenPower. As net-zero operational emissions are highly likely by 2035, offset strategies for embodied emission residuals can leverage market-based tools, such as Australian Carbon Credit Units, which expand beyond the real estate portfolio.

Figure 9.

Net-zero operation, net-zero embodied, and whole-of-life net-zero emissions.

5. Discussions

Globally, building regulations have generally focused more on improving energy efficiency during building operation. Recently, European and North American countries have begun implementing mandatory targets for embodied carbon emissions, along with measurement and disclosure requirements [51]. In Australia, recent policies—including NDCs, the built environment sector plan, and the trajectory for low-energy buildings—highlight embodied carbon emissions as critical climate mitigation strategies. This is in line with the findings of Skillington et al. [5], which pointed to embodied carbon emissions-related gaps in Australian policies, especially the regulatory mechanism targeting the built environment sector. Nonetheless, rating systems for embodied carbon, along with measurement, disclosure, and reporting, are being considered as interim measures. However, commitments to reach net-zero embodied emissions remain ongoing, despite notable progress in reducing operational emissions and a promising pathway toward operational decarbonisation by 2035. The analysis of built environment sector policies and emerging and evolved technologies sheds light on three key aspects of whole-of-life net-zero emissions that future policies can further address.

While the goal of net-zero operational emissions may seem straightforward, with the potential to achieve it by 2035, practical challenges remain. Brown et al. [52] highlight climate and cost issues as two major barriers to reaching net-zero emissions in Australian buildings, alongside government policy factors. Cost concerns involve technology deployment, sustainability certification and rating systems, disclosure and reporting, and compliance with building codes and performance standards relevant to the Australian built environment sector. Commercial building owners face the challenge of offsetting these costs through improved energy performance, increased revenue from tenancy agreements, higher asset value, and lower regulatory and compliance expenses—collectively managing carbon risks. Climate issues mainly relate to building operations and operational costs, with studies [30] indicating that operational energy use may increase under climate-extreme scenarios. Although this study relied on operational energy consumption estimated from the TMY weather files, space heating and cooling demand could vary across climate scenarios (e.g., RCPs and SSPs). Any additional climate-related energy demand can undo some of the progress made toward net-zero operational emissions, thereby hindering progress toward operational decarbonisation by 2035. Thus, net-zero transition planning must account for climate variability and extremes to future-proof building operations from carbon risks. While current policies prioritise operational decarbonisation relative to embodied carbon emissions reduction, state governments across Australia agree that climate resilience should be incorporated into the Australian Building Codes Board (ABCB) guidelines for future NCC updates. Nonetheless, gaps remain, as the NCC does not address energy resilience aspects to the extent that structural resilience of buildings is addressed. The 2025 built environment sector plan and the trajectory for the low-energy buildings policy update (2025) outline efforts to incorporate energy resilience concepts such as demand response and demand flexibility. However, these policies lack explicit strategies for implementing energy resilience, specifically in commercial buildings. For example, the provision of building microgrids and policy actions favouring vehicle-to-building and vehicle-to-grid concepts are still nascent to commercial building owners and operators.

Second, the shift from gas to electric and GreenPower purchase are both promising mitigation strategies, and they seem to be straightforward steps toward rapidly decarbonising building operations. However, they push for more grid electricity consumption, which remains a paradoxical mitigation strategy for commercial buildings. While Australia, especially the NSW jurisdiction, is making rapid progress in grid decarbonisation, relying solely on grid power without sufficient on-site generation and storage can undermine efforts to improve energy resilience and meet demand flexibility goals outlined in policies, such as the built environment sector plan. Operational energy analysis of the building archetype (Table 1) shows that sufficient on-site energy generation and storage systems can support both decarbonisation and energy resilience goals linked to grid electricity. Thus, while the policies (Figure 1) address technology deployment, electrification of gas using assets, and energy performance standards, demand flexibility and energy resilience—although mildly addressed—can be mainstream policy agenda items in future policy updates.

Finally, strategies for carbon offsetting and future climate mitigation frameworks should prioritise embodied carbon emissions. Analysis of the commercial building archetype (Table 1) shows that operational decarbonisation is achievable through existing policy measures addressed by climate mitigation plans (Figure 1). Nonetheless, for most existing commercial buildings, reaching net-zero embodied carbon emissions remains both technically challenging and hindered by policy barriers. Although initial efforts to measure and disclose embodied carbon emissions are promising, the policy emphasis on disclosure and reporting needs to advance quickly, especially as methods for accounting embodied carbon become more refined and industries develop ways to produce building materials with lower embodied carbon. Skillington et al. [5] suggested regulatory whole-building targets and caps that incorporate embodied carbon emissions as a longer-term solution, which aligns with the early efforts of target setting and disclosure. This is reasonable given the inconsistencies around embodied carbon emissions data in the building sector. Another long-term strategy is to examine the product and project levels for material-specific strategies. For example, the use of recycled material (e.g., steel) was found to have the potential to reduce the upfront embodied carbon emissions of steel by up to 80% [49]. There is a range of databases available (e.g., EPiC database [41]) to navigate substitute materials with lower embodied emissions. Thus, it is suggested that major refurbishment projects in existing commercial buildings consider low-carbon materials and their environmental and structural value propositions from the design phase onward.

While the use of low-carbon construction materials in existing buildings is inevitable, market barriers across the supply chain, including production and consumption, remain. First, manufacturers are supplying low-carbon materials relative to conventional materials, which may further reduce embodied emissions. As such, the long-term emissions reduction strategy emphasises support in the production of low-carbon concrete, which shall expand across other material types. Second, while the local Australian database for embodied emissions (e.g., EPiC) is a useful resource, there remains a fair degree of concern about the quality of embodied emissions data, especially in the absence of EPDs. Most building refurbishment contracts rely on manufacturers to provide data backed by robust lifecycle analysis. The importance of EPD certificates and LCA-generated embodied emissions data will only grow as policies (Figure 1) indicate structured reporting of embodied carbon emissions. Third, the performance criteria for low-carbon materials, such as the structural integrity of low-carbon concrete and the thermal performance of recycled insulation materials, is another barrier. Future policy reform should collectively address these market barriers to realising net-zero embodied emissions.

6. Conclusions and Limitations

This study examined the prospects of achieving whole-of-life net-zero emissions in commercial buildings through two stages. First, the transition to operational decarbonisation by 2035, and then to whole-of-life net-zero emissions by 2040. While the initial stage of the decarbonisation goal seemed feasible, assuming that existing policies meet their technological and policy objectives, the second stage—achieving whole-of-life net-zero emissions—appears more difficult, mainly due to residual embodied carbon emissions.

The first stage of the operational decarbonisation goal by 2035 is supported by improvements in on-site renewable energy, electrification of gas-powered assets, and increased lighting and plug load efficiency. Together, these help reduce operational emissions and are already the main focus of existing climate mitigation policies targeting commercial buildings. For existing buildings, accounting for and reducing embodied carbon emissions mainly relies on material substitution strategies, especially during refurbishment projects. This is crucial because there is limited potential to lower embodied carbon in existing structures. Therefore, future and existing policies aimed at the built environment can mandate reporting on embodied carbon emissions and the disclosure of reduction measures and actions, moving beyond mere data collection and reporting. Achieving whole-of-life net-zero emissions by 2040 seems less feasible under the current policy priorities and market capacity to supply low-emissions materials and products for commercial buildings. Nevertheless, the timeframe between now and 2040, and potentially up to 2050, is reasonable to realise whole-of-life net-zero emissions.

While the study provided insights into the rapid decarbonisation of commercial buildings and carbon risk management, it also highlighted some limitations. Firstly, the study focused on a building archetype located in a single climate zone. Therefore, it did not account for annual energy variability across different climate zones, which is a drawback because buildings in other zones may have different energy-use and consumption patterns, thereby affecting the structure of operational emissions. Likewise, this study used a TMY weather file for building energy simulation, which is a limitation, as weather files generated for future climate scenarios (e.g., RCPs and SSPs) and used in building simulation tools (e.g., OpenStudio) could result in different space heating and cooling energy demand in the future. Secondly, the study assumes that construction-related embodied carbon emissions constitute a significant portion of a building’s total embodied carbon. While this may be somewhat true, building services systems and smaller assets, such as appliances and equipment, may also account for a notable share of the total embodied carbon. Future research could adopt a more holistic approach to analysing embodied carbon emissions and include the impact of different climate zones on operational decarbonisation.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the storage limitations of the raw simulation outputs. However, for reproducibility, the input and model parameters’ data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Semieniuk, G.; Campiglio, E.; Mercure, J.F.; Volz, U.; Edwards, N.R. Low-carbon transition risks for finance. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2021, 12, e678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambhir, A.; George, M.; McJeon, H.; Arnell, N.W.; Bernie, D.; Mittal, S.; Monteith, S. Near-term transition and longer-term physical climate risks of greenhouse gas emissions pathways. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X. Climate transition risk and commercial real estate. SSRN Electron. J. 2025, 4741949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Febo, E. Transition Risk in Climate Change: A Literature Review. Risks 2025, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skillington, K.; Crawford, R.H.; Warren-Myers, G.; Davidson, K. A review of existing policy for reducing embodied energy and greenhouse gas emissions of buildings. Energy Policy 2022, 168, 112920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curmi, L.; Weththasinghe, K.K.; Tariq, M.A. Global Policy Review on Embodied Flows: Recommendations for Australian Construction Sector. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasinghe, I.; Liu, T.; Stewart, R.A.; Mostafa, S. Paving the way for lowering embodied carbon emissions in the building and construction sector. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2025, 27, 1825–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction 2024/2025; United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): Nairobi, Kenya, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Habert, G.; Röck, M.; Steininger, K.; Lupísek, A.; Birgisdottir, H.; Desing, H.; Lützkendorf, T. Carbon budgets for buildings: Harmonising temporal, spatial and sectoral dimensions. Build. Cities 2020, 1, 429–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verikios, G.; Reedman, L.; Green, D.; Nolan, M.; Lu, Y.; Rodriguez, S.; Murugesan, M.; Havas, L. Modelling Sectoral Pathways to Net Zero Emissions; EP2024-4366; CSIRO: Canberra, Australia, 2024; 66p. [Google Scholar]

- DCCEEW. Achieving Low Energy Existing Commercial Buildings in Australia; Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water: Canberra, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- DCCEEW. Commercial Building Baseline Study 2022—Final Report; Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water: Canberra, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- DCCEEW. Australia’s 2035 Nationally Determined Contribution; Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water: Canberra, Australia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- DCCEEW. The Trajectory for Low Energy Buildings Update; Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water: Canberra, Australia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, D.; Dave, M.; Kuru, A.; Oldfield, P.; Ding, L.; Noller, C.; He, B. Race to Net Zero Carbon: A Climate Emergency Guide for New and Existing Buildings in Australia v1b; Updated 2022; Low Carbon Living Institute: Sydney, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- DCCEEW. NCC 2025 Worked Examples; Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water: Canberra, Australia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- DCCEEW. Australia’s Long-Term Emissions Reduction Plan; Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water: Canberra, Australia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, C.; Oldfield, P.; Teh, S.H.; Wiedmann, T.; Langdon, S.; Yu, M.; Yang, J. Modelling ambitious climate mitigation pathways for Australia’s built environment. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 77, 103554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, W.; Oldfield, P.; Reinmuth, G.; Hadley, D.; Balmforth, S.; Nguyen, A. Towards net-zero embodied carbon: Investigating the potential for ambitious embodied carbon reductions in Australian office buildings. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 113, 105702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.U.; Cicco, I.; Bilec, M.M. Advancing Urban Building Energy Modeling: Building Energy Simulations for Three Commercial Building Stocks through Archetype Development. Buildings 2024, 14, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Deng, W.; Hong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ye, Y.; Chen, S.; Xu, D. The advantages and challenges of integrating archetypal building modelling for urban building energy models: A systematic review. Energy Build. 2025, 345, 116066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, N.; Bilbao, J.; Kay, M.; Sproul, A. Future climate scenarios and their impact on heating, ventilation and air-conditioning system design and performance for commercial buildings for 2050. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 162, 112363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniya, B. Multi-hazard climate risks and resilience planning for urban commercial buildings: Spotlight on building services systems. Build. Simul. 2025, 18, 3201–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Building Codes Board (ABCB). National Construction Code (NCC), Building Classifications; ABCB: Canberra, Australia, 2025.

- Foo, G.S.; Shen, D. Australian Commercial Buildings Window to Wall Ratios. In Proceedings of the 52nd International Conference of the Architectural Science Association (ASA) 2018, Melbourne, Australia, 28 November–1 December 2018; pp. 231–240. [Google Scholar]

- Afroz, Z.; Goldsworthy, M.; White, S.D. Energy flexibility of commercial buildings for demand response applications in Australia. Energy Build. 2023, 300, 113533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DCCEEW. Built Environment Sector Plan; Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water: Canberra, Australia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Frank, S.; Im, P.; Braun, J.E.; Goldwasser, D.; Leach, M. Representing small commercial building faults in EnergyPlus, part II: Model validation. Buildings 2019, 9, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flechas, G.M. OpenStudio validation of a CLT building in Colorado. ASHRAE Trans. 2021, 127, 37–39. [Google Scholar]

- Baniya, B.; Giurco, D. Net zero energy buildings and climate resilience narratives—Navigating the interplay in the building asset maintenance and management. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 1632–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Tang, Z.; James, M. Predictive Weather Files for Building Energy Modelling; CSIRO: Canberra, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bamdad, K.; Matour, S.; Izadyar, N.; Law, T. Introducing extended natural ventilation index for buildings under the present and future changing climates. Build. Environ. 2022, 226, 109688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniya, B.; Giurco, D. Cost-effective and optimal pathways to selecting building microgrid components—The resilient, reliable, and flexible energy system under changing climate conditions. Energy Build. 2024, 324, 114896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Salgado, C.; Díaz-Bello, D.; Alfonso-Solar, D.; Lara-Vargas, F. Validations of HOMER and SAM tools in predicting energy flows and economic analysis for renewable systems: Comparison to a real-world system result. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 69, 103896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marqusee, J.; Ericson, S.; Jenket, D. Impact of emergency diesel generator reliability on microgrids and building-tied systems. Appl. Energy 2021, 285, 116437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DCCEEW. National Greenhouse Accounts Factors: 2025; Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water: Canberra, Australia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Carbon Risk Real Estate Monitor (CRREM). CRREM Pathway Methodology; CRREM: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cang, Y.; Luo, Z.; Yang, L.; Han, B. A new method for calculating the embodied carbon emissions from buildings in schematic design: Taking “building element” as basic unit. Build. Environ. 2020, 185, 107306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhayat, Y.; Moran, P.; Barrett, S.; Barry, P.; Goggins, J. Developing a methodology with a tool for calculating and reducing the upfront carbon emissions of buildings: Ireland as a case study. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, F.; Nižetić, S.; Wang, F. Future technologies for building sector to accelerate energy transition. Energy Build. 2024, 326, 115044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, R.H. EPiC Database; The University of Melbourne: Melbourne, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, M.; Huang, Z.; Zheng, Y. A review on life-cycle carbon emissions of reinforced concrete buildings: Calculation and reduction. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 526, 146501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuru, A.; Lyu, K.; Gocer, O.; Brambilla, A.; Prasad, D. Climate risk assessment of buildings: An analysis of operating emissions of commercial offices in Australia. Energy Build. 2024, 315, 114336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, H.; Huang, H.; Yang, H. Renewable energy design and optimization for a net-zero energy building integrating electric vehicles and battery storage considering grid flexibility. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 298, 117768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wu, J.; Liu, K.; Guan, X. Coordinated integration of hydrogen-enabled multi-energy systems to achieve zero-carbon buildings. Build. Environ. 2025, 284, 113433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawati, H.; Broersma, S.; Itard, L.; Mohammadi, S. Integrated Hydrogen in Buildings: Energy Performance Comparisons of Green Hydrogen Solutions in the Built Environment. Buildings 2024, 15, 3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Ma, M.; Zhou, N.; Ma, Z. Toward net zero: Assessing the decarbonization impact of global commercial building electrification. Appl. Energy 2025, 383, 125287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Khazaei, J.; Freihaut, J.D. Optimal integration of Vehicle to Building (V2B) and Building to Vehicle (B2V) technologies for commercial buildings. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2022, 32, 100921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Liu, J.; Piette, M.A.; Xie, J.; Pritoni, M.; Casillas, A.; Yu, L.; Schwartz, P. Comparing simulated demand flexibility against actual performance in commercial office buildings. Build. Environ. 2023, 243, 110663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Wang, X.; Kim, J.; Gowda, A.; Wang, M.; Mlade, J.; Farbman, S.; Leung, L. Whole-building life-cycle analysis with a new GREET® tool: Embodied greenhouse gas emissions and payback period of a LEED-Certified library. Build. Environ. 2022, 209, 108664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röck, M.; Balouktsi, M.; Saade, M.R.M. Embodied carbon emissions of buildings and how to tame them. One Earth 2023, 6, 1458–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.; Tokede, O.; Li, H.X.; Edwards, D. A systematic review of barriers to implementing net zero energy buildings in Australia. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 467, 142910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.