Abstract

This research paper explores the key role of energy analysis in the initial phases of architectural design. The main research question is as follows: How can energy analysis shape and optimize architectural design variables? To address this question, the research paper identifies key architectural design variables, including structural system, roof, window-to-wall ratio (WWR), and building envelope, all of which are influenced by energy efficiency strategies. Through case studies of residential buildings in Bahrain, the research investigates the optimization of these design variables. Energy models are employed to explore the impact of energy analysis on the design and performance of the selected residential buildings. The findings reveal a significant potential for energy reduction in annual consumption through the collective optimization of passive strategies. Furthermore, specific energy reduction for each sole variable is observed, as follows for structural system material (3.63% to 11.29%), roof thermal insulation (0.75% to 3.37%), WWR optimization (0.61% to 1.27%), and building envelope (7.39% to 13.5%). These findings establish energy analysis as a fundamental design approach for initial design phases or selection between design alternatives, and can be generalized to similar arid, humid climates and residential building designs.

1. Introduction

Traditionally, architectural design was dominated by manual drawing and evaluated by aesthetic-driven approaches characterized by elements such as rich ornamentations, prominent columns, and grand arches, which often utilized local materials. In the late nineteenth century, principles such as ‘form follows function’ were adopted to describe a design philosophy that sought to avoid these foregoing rules and elements, particularly strict symmetrical rules and excessive ornamentation. Design approaches such as bioclimatic design emerged after the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) defined sustainable development in 1987 [1]. By 1990, conceptual design and underlying ideas grew significantly and gained greater prominence, emphasizing the importance of conceptual ideas in the architectural design process [2,3].

In the late 90s and early 2000s, the integration of digital media into the design process evolved and led to a fundamental shift towards formalization through computational design, rule-based design, and parametric design [4,5]. The benefits of interaction between digital and manual methods during initial design phases have been identified and adopted into the design process. These media interactions allow for enhanced visualization and preliminary analysis, fostering a more iterative and informed conceptualization. Primarily, they enable the development of more complex architectural forms, including designs with non-orthogonal, curvaceous surfaces [6,7].

By the early 2000s, the comprehensive potentials of Building Information Modelling (BIM) had become increasingly evident, extending beyond mere 3D modelling. BIM encompasses data integration and advanced simulation functionalities, thereby enabling comprehensive building performance, to the extent of radically transforming conventional design methods and approaches, as well as architecture making. This paradigm shift is imperative in the industry and professional practice, as it has led to newly created job titles related to BIM applications in construction, and consequently to the evolution of construction project management operations towards more data-driven methodologies [8]. Concurrently, it is transforming fundamental pedagogies and design studio settings in architectural education to cope with these market demands [9].

Currently, it is essential to employ the multidisciplinary model of BIM to fully benefit from digital analytical tools, particularly for the environmental analysis and energy optimization of initial design masses. Creating energy models through 6D BIM capabilities allows for the investigation of the impact of orientation, wind behaviour, velocity, and other essential environmental factors. Furthermore, BIM facilitates the development of 4D and 5D models, enabling the calculation of material quantities and costs, and the evaluation of various construction scenarios [8,10]. These comprehensive economic and environmental benefits are fundamental to achieving sustainable design, which is further enhanced by integrating social factors into the design process.

The research paper supports the broader context of national and global efforts to combat climate change and promote sustainable development. It, moreover, directly supports Bahrain’s commitment to reducing energy consumption and its carbon footprint, which is a key component of the nation’s strategy to align with the global Sustainable Development Goals. This fundamental research paper contributes to the academic pursuit of achieving net-zero emissions and embedding sustainable practices.

The research paper utilizes three case studies of residential buildings from an existing project, the Danat Albarakah project, developed by Eskan Bank, a key developer of sustainable social housing programmes and solutions in Bahrain. The three cases are real-world two-story houses, whose energy models are analyzed and optimized.

This study aims to investigate the extent to which energy analysis can shape and optimize architectural design variables. In other words, how can energy analysis shape and optimize architectural design variables? Specifically, does a hierarchical relationship exist where architectural design decisions are systematically guided by the outcomes of energy analysis? Therefore, it can be maintained that architectural design follows energy analysis.

The study is considered a leading one in this geographical area, which shares similar climates, economic and social factors, as well as construction processes and building materials. Moreover, the uniqueness of this study lies in the fact that the proposed design factors are calculated cumulatively.

2. Scope and Objectives

The scope of this study is to investigate the relationship between key architectural design variables and primary energy efficiency. The study is confined to an analysis of how these variables influence energy savings, as measured using energy modelling software.

While architectural design is ideally guided by sustainable design factors as a comprehensive approach, this research paper specifically focuses on the energy analysis of environmental factors within residential buildings. Consequently, social factors and economic factors fall outside the scope of this study.

The objective is not to calculate or simulate the actual energy consumption, but rather to determine the relative difference resulting from the proposed design factors by keeping other factors constant, to prove the design approach proposed.

The study proposes four design variables that collectively shape the architectural design, namely structural system, roof thermal insulation, WWR, and building envelope thermal insulation. Previous research co-authored by the researcher focused solely on measuring the individual impact of the first three variables on energy efficiency [11,12,13]. This study, however, measures the collective impact of all four proposed design variables and then proceeds to develop a specialized design method for implementing passive design improvements in the initial design phases.

3. Methodology

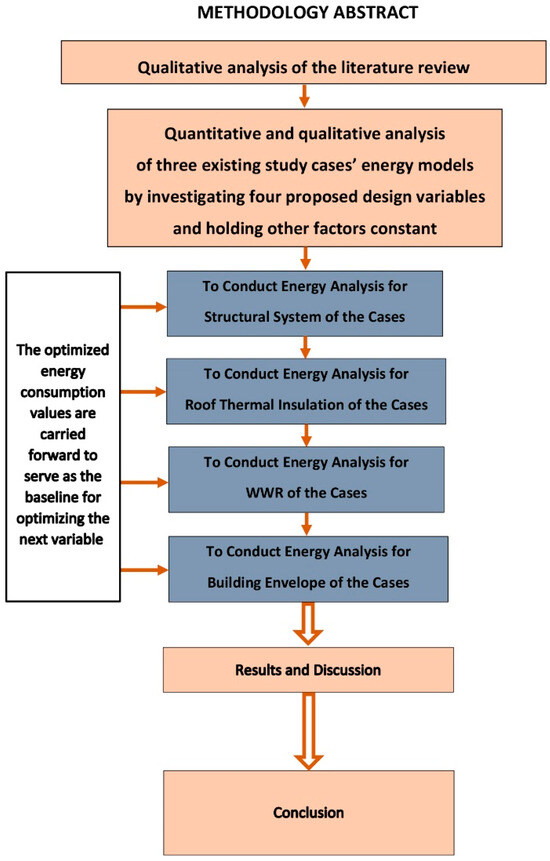

The study employs a two-fold methodology combining qualitative and quantitative analysis; see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Methodology abstract.

- -

- Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis: Qualitative analysis of secondary data—the literature review—is conducted alongside a quantitative analysis of primary data generated from the BIM energy models of existing study cases. The energy models will be qualitatively and quantitatively analyzed. This process will highlight the direct impact of proposed architectural design variables on energy savings and overall energy model performance.

- -

- Optimization and Contribution Analysis: Using the analysis performed through the Revit programme (version 2023) and the Insight plug-in, an optimization process will be applied to the energy models. This will allow for the improvement of the models’ energy efficiency and provide a clearer understanding of the individual contribution of each architectural design variable to the overall energy-saving outcome.

- -

- Based on the secondary data, the study proposed key architectural design variables for investigation. To isolate the impact of these factors (e.g., structural system, roof thermal insulation, window-to-wall ratio (WWR), and building envelope thermal insulation, other variables affecting energy consumption—such as architectural design parameters (including topology and spatial ratios), door and window materials, shading devices, and HVAC system efficiency—are kept constant or neutralized. Moreover, although the methodology of this research paper neutralizes the economic factor, it remains a key consideration in material selection and other aspects of design.

- -

- The methodology involves two distinct energy analyses. The first establishes the current energy consumption of the case studies, setting a baseline. The second, conducted after the implementation of optimization strategies, measures the improvements in energy performance.

- -

- The optimization values derived for each design variable are retained and utilized sequentially in the post-optimization process of the subsequent design variable. Finally, the collective energy savings achieved by all proposed design variables are quantified, Figure 1.

This approach provides a detailed understanding of how specific design choices impact building performance in the context of Bahrain’s hot climate. Furthermore, it directly addresses the main research question of this study.

4. Literature Review

According to the Ministry of Works in Bahrain, the Standard Specifications are intended to serve as a minimum acceptable standard for design on its projects. They are meant to be a guide for design professionals, not a limitation on their overall responsibility [14].

The literature review revealed that the residential sector has the largest energy consumption in Bahrain, with air conditioning alone responsible for more than 70% of total electricity usage [15]. In addition, the importance of energy efficiency in architectural design is highlighted. This study categorizes the literature review according to the proposed architectural design variables: structural system, roof thermal insulation, WWR, and building envelope thermal insulation. In addition, it reviews the benefits of integrating energy analysis with the design process.

4.1. Structural System

Heavyweight mass is more energy-efficient in hot, humid climates than lightweight mass [16]. High thermal mass contributes to regulating internal temperature; however, it can increase energy use during both summer and winter [17].

Research work investigated the impact of structural systems on energy consumption. A paper considering both thermal energy performance and environmental factors was conducted to compare the energy efficiency of two reinforced concrete systems: a pure shear wall system and a shear wall frame system. The paper concluded that the Solar Energy Gain Coefficient (SEGC) of the transparent components was 60%, and the thermal permeability of the inner walls was calculated at 1.923 W/m2·K. The shear wall frame system consumed 29.06% less energy than the pure shear wall system [18].

Achieving energy efficiency requires a balance between high-density structural material—for thermal mass—and highly insulative, low-density material—for thermal resistance [19,20].

4.2. Roof Thermal Insulation

Roof thermal insulation is essential to improve building performance, which leads to greater energy savings. Implementing a basic green roof contributes to a building’s energy savings, but it cannot replace the indispensable function of roof thermal insulation [21].

Increasing insulation thickness reduces heat transfer, but it can also limit the effectiveness of passive cooling techniques like natural ventilation and night flushing, which rely on heat exchange with the external environment [22].

In hot climates, low-rise residential buildings can achieve substantial energy savings by using cool envelope technologies. Implementing these strategies can result in annual cooling load reductions of up to 26% in arid cities and 18% in semi-arid cities [23]. Achieving the time lag and the damping—reduction in magnitude—of the temperature wave is essential as heat transfer occurs from the exterior surface to the interior surface of a wall or roof assembly [19].

By using an algorithmic hybrid matrix roof design that systematically varied roof shape, material, and construction, a paper found that a vault roof with a high-albedo coating can reduce discomfort hours by 53% and save 826 kWh during the summer compared to a conventional, non-insulated flat roof in Cairo’s hot, dry climate [24].

4.3. WRR

While a higher WWR enhances natural ventilation and lighting, this increase may result in greater energy consumption. In addition, the climate conditions can slightly change the optimal WWR [25].

Using Design Builder V5 software (with Energy Plus simulation engine) to simulate 300 two-story houses, the results showed that a 20% WWR provided the highest thermal comfort. Furthermore, WWR was found to influence thermal comfort by 20–55% and lighting efficiency by 1.5–9.5% [26].

A paper utilizing the simulation software EnergyPlus and the optimization program GenOpt examined WWR in office buildings. The findings revealed that adjusting the WWR and glazing on a floor-by-floor basis is an effective strategy for improving overall building performance [27].

4.4. Building Envelope Thermal Insulation

To understand the impact of insulation, a study examines how external wall insulation thickness influences energy consumption for both cooling and heating. The study provides a nuanced perspective, concluding that simply adding a thicker layer of insulation does not consistently result in energy savings, particularly in climates where cooling is the primary demand [28]. Another study focusing on the Italian climate and façade retrofitting concludes that the building envelope accounts for 50% of the overall energy balance [29].

To reduce heat transfer in hot, dry climates, a paper emphasizes the critical role of materials with high thermal inertia. The paper specifically examines the impact of various opaque building components, such as walls, roofs, and insulation, on thermal comfort and energy consumption, using a case study of Biskra, Algeria [30].

A condensed structural material—i.e., high-density material like concrete, masonry, or stone—resists changes in temperature by absorbing and storing large amounts of heat. A porous structural material—i.e., low-density material like lightweight concrete, fibreglass, or foam insulation—has many trapped air pockets. It acts as an insulator with low thermal conductivity, suggesting a high R-value [19].

A study was conducted to determine how different building envelope materials perform in hot and humid climates. The results reveal that brick and glass are superior choices, as they are especially effective at reducing heat gain and minimizing indoor heat transfer, thereby improving thermal comfort [31].

4.5. Energy Analysis in Design Phases

Implementing different energy factors, such as roof insulation, reducing air infiltration, installing energy-efficient appliances, lighting fixtures, heating and cooling equipment, and WWR, results in a 50% reduction in energy consumption in current design practices of homes in Tunisia [32].

Under Oman’s climatic conditions, a base case model was simulated to evaluate various envelope design strategies such as wall and roof insulation, thermal mass, and window characteristics. The most energy-efficient designs achieved significant energy savings: 16.56% in warm humid climates, 25.93% in hot, humid climates, and 28.46% in hot, dry climates [33].

In a paper that covers the hot climates of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), a comprehensive overview of the role of thermal insulation in improving building performance is conducted. A key finding is that while relevant regulations are in place, insufficient enforcement frequently results in energy consumption that is far higher than optimal [34].

4.6. Literature Review Summary

The literature review highlights that integrating energy analysis during the design phases leads to significant energy reduction. It is indispensable to explore a design’s energy consumption during its initial design phases. Although this early energy analysis may not be fully accurate due to incomplete design details and material selection, it provides indicative values for the potential energy reduction resulting from the passive strategies. The passive design strategies are most efficient and effective when they are integrated and implemented early in the design process. After establishing this principle using the secondary data, this study now proceeds to obtain the primary data to validate this design approach proposed by this study.

5. Results and Analyses

In order to validate the proposed design approach, the research paper conducts an energy analysis to identify and optimize energy consumption in residential units within a project in Bahrain based on the proposed design variables. Three residential units with similar gross floor areas were selected to serve as study cases. The analysis quantifies the energy reduction ratios of the three cases according to their energy performance.

The energy analyses are performed for the proposed design variables that collectively shape in shaping the architectural design, namely structural system, roof, WWR, and building envelope, as follows.

5.1. Structural System Energy Analysis

The structural system used in the initial energy analysis was with in situ concrete columns and precast concrete slabs; thermal conductivity 1.046 W/(m·k); specific heat 0.6570 J/(g·°C); density 2300 KG/m3; permeability 182.4 ng/(Pa·s·m2); porosity 0.01; and emissivity 0.95. Other factors were neutralized during this analysis.

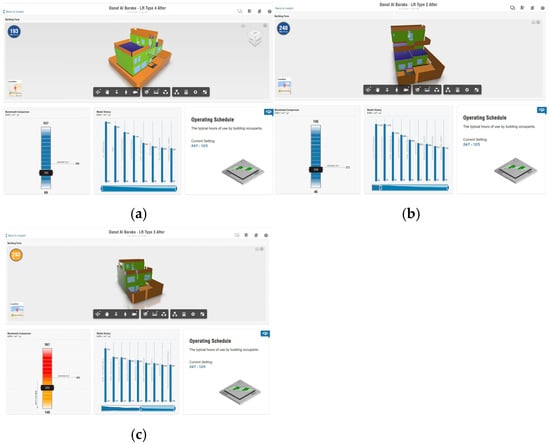

The initial energy consumption for the three case study houses was as follows, ranked from lowest to highest: case study 3 achieved 193 kWh/m2·yr; case study 1 achieved 248 kWh/m2·yr; and case study 2 achieved 293 kWh/m2·yr. See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Energy analysis of study cases before structural system optimization. (a) Case study 3 achieved 193 KWh/m2·yr. (b) Case study 1 achieved 248 KWh/m2·yr. (c) Case study 2 achieved 293 kWh/m2·yr.

5.1.1. Structural System Optimization Strategies

Lightweight slabs and columns are defined in the BIM model to investigate the impact of this optimization process. The thermal properties of the structural system used in the optimization process are as follows: thermal conductivity 0.2090 W/(m·k); specific heat 0.6570 J/(g·°C); density 950 KG/m3; permeability 182.4 ng/(Pa·s·m2); porosity 0.01; and emissivity 0.95. See Supplementary S1.

5.1.2. Energy Analysis After Structural System Optimization Strategies

Following the optimization process, the energy consumption for the three case study houses was quantified as follows: case study 3 consumed 186 kWh/m2·yr, case study 1 consumed 220 kWh/m2·yr, and case study 2 consumed 264 kWh/m2·yr, Figure 3.

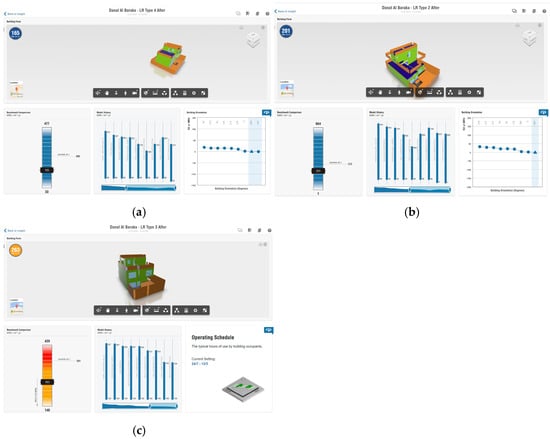

Figure 3.

Energy analysis of study cases after structural system optimization. (a) Case study 3 achieved 186 KWh/m2·yr. (b) Case study 3 achieved 186 KWh/m2·yr. (c) Case study 2 achieved 264 KWh/m2·yr.

The optimization of structural systems can significantly impact energy consumption in residential buildings. The case study of houses in Bahrain revealed energy savings ranging from 3.63% to 11.29% through optimized structural design.

5.2. Roof Thermal Insulation Energy Analysis

The optimized energy consumption values from one design variable are carried forward to serve as the baseline for optimizing the next variable in the sequence. Throughout the energy analysis of the structural system, roof, and WWR sections, the wall’s thermal properties were assumed to be constant, with thermal conductivity 0.81 W/(m·k), specific heat 0.84 J/(g·°C), density 1650 kg/m3, and emissivity 0.95. The wall properties were investigated only in the Building Envelope Section; see Supplementary S1.

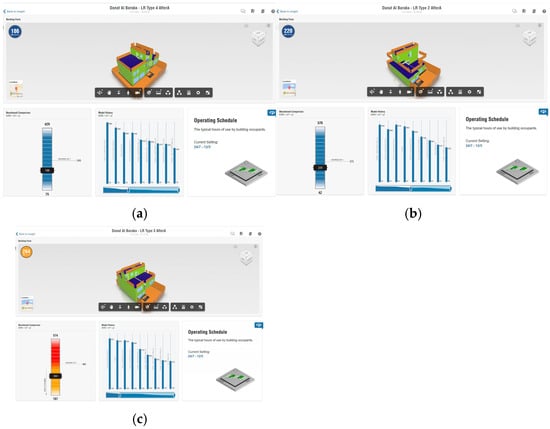

Initially, energy models were developed for the three study cases using a roof construction with an approximately R-value of 2.22 (m2·K)/W, including an Extruded Polystyrene (XPS) layer of 50 mm width, with an R value of 1.76 (m2·K)/W; see Supplementary S2. Based on the results of these initial simulations, the cases were ranked in terms of energy performance, with case study 3 demonstrating the highest energy savings, followed by case study 2 and case study 3; see Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Energy analysis of study cases before roof thermal insulation optimization. (a) Case study 3 achieved 168 KWh/m2·yr. (b) Case study 1 achieved 208 KWh/m2·yr. (c) Case study 2 achieved 265 kWh/m2·yr.

5.2.1. Roof Thermal Insulation Optimization Strategies

To optimize energy performance, energy models for the three study cases were developed with a roof construction incorporating a total R-value of 3.68 (m2·K)/W. This total comprises a thermal insulation layer that is an approximately 70 mm SIP (structural insulated panel) with an R-value of 3.22 (m2·K)/W; see Supplementary S2.

5.2.2. Energy Thermal Analysis After Roof Insulation Optimization Strategies

Although case study 3 demonstrated the best baseline energy performance, case study 1 exhibited the most significant energy reduction potential after optimization, achieving a 3.37% decrease. This was followed by a 1.79% reduction for case study 3 and a 0.75% reduction for case study 2, Figure 5. The differences in energy reduction values for the study cases resulted from variations in each case’s design, specifically its thermal mass and spatial configuration.

Figure 5.

Energy analysis of study cases after roof thermal insulation optimization. (a) Case study 3 achieved a 1.79% reduction. (b) Case study 1 achieved a 3.37% reduction. (c) Case study 2 achieved a 0.75% reduction.

5.3. WWR Energy Analysis

This part of the energy analysis focuses on the Southern and Western façades because they receive the most sun exposure throughout the day. All other variables were held constant for this analysis. The optimized results for prior design variables are iteratively applied to the analysis of this variable, WWR.

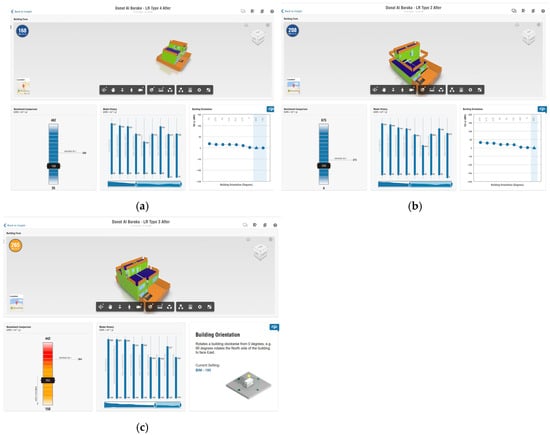

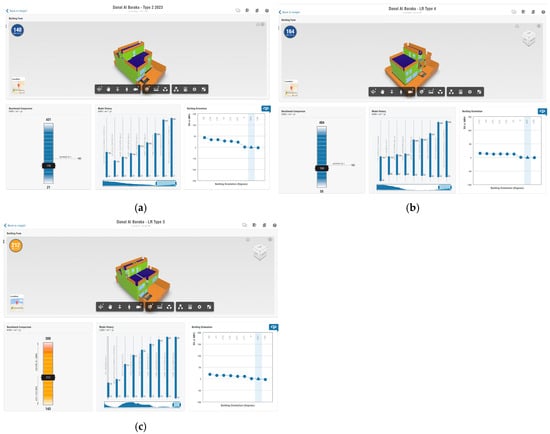

The initial energy consumption for the three case study houses was as follows, ranked from lowest to highest: case study 1 (141 kWh/m2·yr); case study 3 (164 kWh/m2·yr); and case study 2 (212 kWh/m2·yr). See Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Energy analysis of study cases before WWR optimization. (a) Case study 1 achieved 141 KWh/m2·yr. (b) Case study 3 achieved 164 KWh/m2·yr. (c) Case study 2 achieved 212 kWh/m2·yr.

5.3.1. Energy Analysis After WWR Optimization Strategies

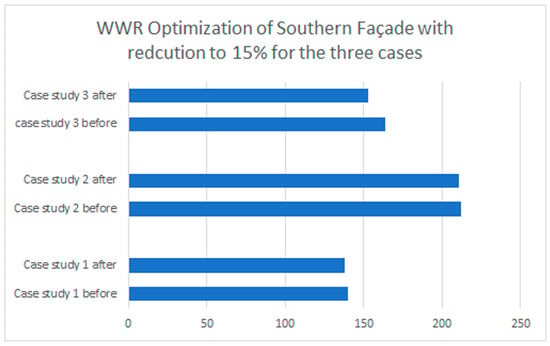

For case study 1, the Southern façade’s WWR achieved energy saving improvement of 1.27% when it was reduced from 22% to 15% (i.e., 31.82% reduction); see Figure 7. The northern façade’s WWR achieved an improvement of 1.34% when it was reduced to 11.76%. Both Eastern and Western façades have no windows.

Figure 7.

Energy analysis measured in KWh/m2·yr for the Southern façade where the WWR was optimized to 15% for all the three cases.

For case study 2, the Southern façade’s WWR achieved a 0.61% improvement in energy saving when it was reduced from 23% to 15% (i.e., 34.78% reduction); see Figure 6. The Northern façade’s WWR achieved an improvement of 0.63% when it was reduced to 21.05%. The Eastern façade achieved 0.7% when reduced from 6% to 3%, and Western façades have no windows.

For case study 3, the Southern façade’s WWR achieved energy-saving improvement of 0.62% when it was reduced from 27% to 15% (i.e., reduced 44.4%), Figure 6. The Northern façade’s WWR has no change when it is reduced by 31.82%. The Eastern façade’s WWR had no windows, and the Western façade’s WWR achieved an energy-saving improvement of 1.5% when it was reduced from 3% to 1.5%.

5.3.2. WWR Optimization Strategies

Achieving the objective of determining the optimal WWR for various building orientations requires a balanced design approach. This approach must integrate the benefits of natural lighting and ventilation with the need for energy efficiency, as an increased WWR can enhance daylighting and airflow but may simultaneously lead to significant energy consumption.

The analysis of the three case studies revealed that reducing the WWR of the southern facades by 31.82%, 34.78%, and 44.4%, respectively, resulted in energy savings of 1.27%, 0.61%, and 0.62%. In contrast, reducing the WWR of the Northern façades by 11.67%, 21.05%, and 31.82% led to energy savings of 1.34%, 0.63%, and 0.0%, respectively. A key factor in this outcome is the lack of sun exposure on the northern façades.

5.4. Building Envelope Energy Analysis

The optimization values for all preceding energy analyses used the following input thermal properties for the building envelope elements:

- -

- The lightweight concrete superstructure assemblies (slabs and columns) were analyzed by employing the composite thermal resistance of individual layers, as follows:

- The slab of 200 mm thickness with an R value of 0.40 (m2·K)/W.

- The column 400 × 600 mm section dimensions. Its R value ranges from 0.80 to 1.20 (depending on column orientation), resulting in an average R value of 1.0 (m2·K)/W, Supplementary S3.

- -

- The vertical envelope components (i.e., exterior walls) were modelled with an R value of approximately 1.08 (m2·K)/W, including an insulation layer (EPS foam) of 25 mm thickness with an R value of 0.704 (m2·K)/W, Supplementary S3.

The output values from the previous energy optimization processes were recorded for all three study cases as follows: case study 1 (138 KWh/m2·yr), case study 3 (163 KWh/m2·yr), and case study 2 (211 KWh/m2·yr). These data serve as the baseline for comparison against the post-optimization results.

Energy Analysis After Building Envelope Optimization Strategies

Improving the building envelope performance in hot regions requires managing two essential thermal characteristics. First, low thermal conductivity is fundamental for insulation against heat gain. Second, high thermal mass is key in heat transfer. Materials like porous brick and lighter-weight concrete are used to introduce a time delay, or thermal lag, reducing solar heat transfer into the building interior.

Therefore, as an optimization strategy, an external insulating layer—specifically an Extruded Polystyrene board (XPS) of 30 mm thickness, with an R-value of 1.761 (m2·K)/W—was added to the exterior walls. This addition resulted in the composite R-value of the building envelope being approximately 2.14 (m2·K)/W, Supplementary S3.

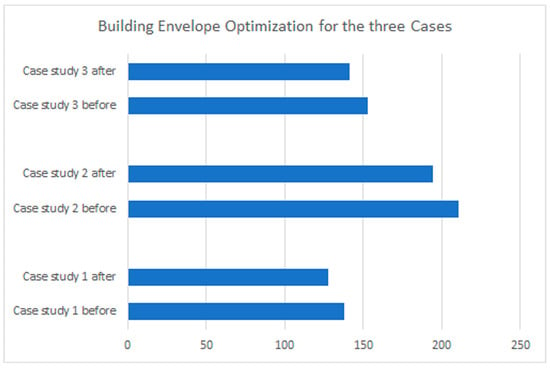

The energy analysis results after optimization were recorded as follows: 128 kWh/m2·y for case study 1, representing 7.39% energy reduction; 141 kWh/m2·yr for case study 3, representing 13.5% energy reduction; and 194 kWh/m2·yr for case study 2, representing 7.93% energy reduction. See Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Energy analysis after building envelope optimization for the three cases, measured in KWh/m2·yr.

6. Further Discussion

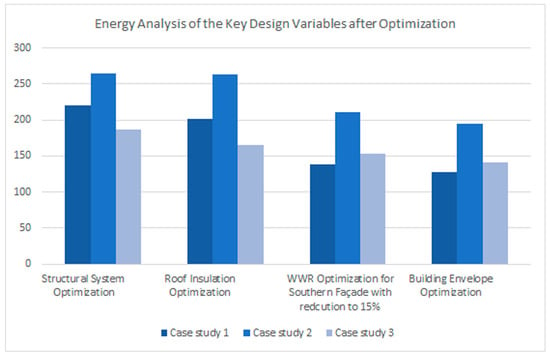

The optimized energy consumption value from each variable forms the new baseline for the following optimization step. The optimized energy performance achieved by the key architectural design variables in the three study cases is summarized in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Energy analysis of the key design variables after optimization for the three cases, measured in KWh/m2·yr.

A clear trend emerges from these results: the optimization process for each design variable consistently contributes to energy reduction by a certain percentage. This reduction percentage remains similar across all three cases throughout the optimization process. When comparing the difference in overall energy reduction among the three cases, case 1 achieved the highest savings, followed by case 3, with case 2 showing the lowest reduction.

Several factors influence the architectural design variables discussed in the preceding sections. For instance, WWR is governed by two opposing considerations: ventilation and daylighting on one hand, and heat transfer and energy gain on the other hand. Additionally, the study methodology held other variables constant, including architectural design parameters (i.e., topology and spatial ratios), door and window materials, shading devices, and HVAC system efficiency. Despite the influence of all these variables on the energy analysis results, the recorded energy reduction percentages (before and after optimization) are valid for similar arid, humid climates and residential building designs of the GCC area. This validity is ensured because both analyses (pre- and post-optimization) were conducted against the same set of factors and variables. However, it is recommended to conduct sensitivity or cross-climate validation before extrapolating to other climates, such as more humid/drier climates. Furthermore, future research should investigate various residential typologies, building heights, and HVAC configurations, alongside additional energy efficiency factors that remained outside the scope of this study and were held constant throughout the analysis.

The study kept the economic factor constant, focusing on materials commonly used in the local market; however, future research will be directed to explore the influence of economic factors on building material choices and their relationship to energy efficiency.

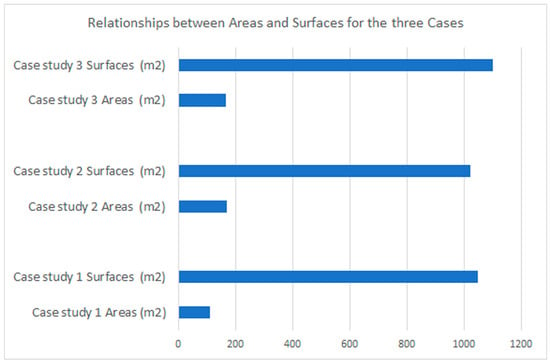

For the three study cases, Figure 10 shows the relationship between their spaces and surfaces, Supplementary S4. In cases 2 and 3, which have areas that are similar, case 3’s 7.62% larger surfaces led to less energy reduction. Case study 3 achieved 26.94%, while case study 2 achieved 34.81%. Case study 1 achieved the largest percentage of energy reduction, 48.39%, while having the smallest area.

Figure 10.

Relationship between spaces and surfaces of the three cases.

7. Conclusions

The study proposed design variables that collectively shape the architectural design, with the aim of developing a design method for the initial phases to improve the energy efficiency of residential buildings. Passive strategies, such as upgrading wall and roof thermal insulation and optimizing WWR, provide significant savings in cooling energy consumption.

The results prove that integrating energy analysis into the initial design phases is essential for improving a building’s passive design and reducing its overall energy consumption. Conducting this analysis as early as possible, or using it to select design alternatives, has a prominently positive impact on energy consumption. Therefore, it can be concluded that architectural design mainly follows energy analysis among other sustainable factors.

Through comprehensive optimization processes involving passive strategies, significant energy reductions were achieved:

- Case study 1: Reduced to 128 kWh/m2·yr, achieving 48.39% energy reduction.

- Case study 2: Reduced to 194 kWh/m2·yr, achieving 34.81% energy reduction.

- Case study 3: Reduced to 141 kWh/m2·yr, achieving 26.94% energy reduction.

The differences in energy reduction values for the study cases resulted from variations in each case’s design, specifically its thermal mass and spatial configuration.

More research is required to investigate the impact of design factors beyond those proposed in this study, aiming to quantify and explore their qualitative contribution to energy efficiency. Moreover, improving passive design during the initial design phases should be the major motivation that shapes the architectural design process. In other words, architectural design should follow energy analysis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/buildings16020333/s1, Screenshots of the energy analysis reports for the three cases before and after optimization. Supplementary S1: Supplementary data on precast concrete and lightweight concrete properties for the three study cases. Supplementary S2: Supplementary data on the proposed design variable (roof layers) before and after optimization processes for the three study cases. Supplementary S3: Supplementary data on the proposed design variable (building envelope) before and after optimization processes for the three study cases. Supplementary S4: Supplementary data on analytical spaces and analytical surfaces for the three study cases.

Funding

This research was funded by the research project 1/2022, Deanship of Scientific Research, Applied Science University, Bahrain.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The author expresses deep gratitude to Applied Science University, Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies, Kingdom of Bahrain, for their support and sponsorship.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Borowy, I. Defining Sustainable Development for Our Common Future: A History of the World Commission on Environment and Development (Brundtland Commission); Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, P.G. Design Thinking; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kimbell, L. Rethinking Design Thinking: Part I. Des. Cult. 2011, 3, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano, I.; Santos, L.; Leitão, A. Computational design in architecture: Defining parametric, generative, and algorithmic design. Front. Archit. Res. 2020, 9, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youns, A.M.; Grchev, K. A historical and critical assessment of parametricism as an architectural style in the 21st century. Buildings 2024, 14, 2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aref, M.; Basel, A.B.H.; Ali, H.A.; Samir, D.; Emad, M. Computational design for futuristic environmentally adaptive building forms and structures. Archit. Eng. 2023, 8, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.K.; Yoo, Y.; Cha, S.H. Generative early architectural visualizations: Incorporating architect’s style-trained models. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2024, 11, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaa Eldin, A.M.; Abdelalim, A.; Tantawy, M. Enhancing Cost Management in Construction: The Role of 5D Building Information Modeling (BIM). Eng. Res. J. 2024, 183, 226–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkoç, O.; Özkoç, H.B.; Tüntaş, D. BIM Integration in Architectural Education: Where Do We Stand? In Eurasian BIM Forum; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Çelik, U. 4D and 5D BIM: A System for Automation of Planning and Integrated Cost Management. In Advances in Building Information Modeling. EBF 2019. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 1188; Ofluoglu, S., Ozener, O., Isikdag, U., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awawdeh, S.; AlKhaja, M.; Abdelhameed, W. Window-to-Wall Ratio Optimization to Save Energy in Housing Projects in Bahrain. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Applications (DASA), Manama, Bahrain, 11–12 December 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlKhaja, M.; Awawdeh, S.; Abdelhameed, W. Structural System Impact on Energy Saving in Housing Projects in Bahrain. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Applications (DASA), Manama, Bahrain, 11–12 December 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhameed, W.; Awawdeh, S.; Alkhaja, M. Impact of Roof Thermal Insulation on Energy Performance in Buildings. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Applications (DASA), Manama, Bahrain, 11–12 December 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standard Specifications for Construction Works, Ministry of Works, Bahrain. Available online: https://www.works.gov.bh/English/Tenders/Pages/StandardConstruction.aspx (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Almasri, R.A.; Alshitawi, M.S. Electricity Consumption Indicators and Energy Efficiency in Residential Buildings in GCC Countries: Extensive Review. Energy Build. 2022, 255, 111664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shareef, S.; Mushtaha, E.S.; Abu Dabous, S.; Alsyouf, I. Holistic Analysis for the Efficiency of the Thermal Mass Performance of Precast Concrete Panels in Hot Climate Zones. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024, 31, 4184–4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alayed, E.; Bensaid, D.; O’Hegarty, R.; Kinnane, O. Thermal Mass Impact on Energy Consumption for Buildings in Hot Climates: A Novel Finite Element Modelling Study Comparing Building Constructions for Arid Climates in Saudi Arabia. Energy Build. 2022, 271, 112324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutumlu, H.; Aydoğdu, B.; İnallı, M. Energy Performance Analysis of Buildings in Terms of Alternative Reinforced Concrete Structural Systems. Eur. J. Res. Dev. 2022, 2, 241–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Hou, L.; Li, S.; Yang, J.; Wang, Q. A Porous Building Approach for Modelling Flow and Heat Transfer Around and Inside an Isolated Building on Night Ventilation and Thermal Mass. Energy 2017, 141, 1914–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, R.; Wang, X.; Di, H.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, Y. New Concepts and Approach for Developing Energy Efficient Buildings: Ideal Specific Heat for Building Internal Thermal Mass. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, C.Y. Air-Conditioning Energy Consumption Due to Green Roofs with Different Building Thermal Insulation. Appl. Energy 2014, 128, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Orazio, M.; Di Perna, C.; Di Giuseppe, E. The Effects of Roof Covering on the Thermal Performance of Highly Insulated Roofs in Mediterranean Climates. Energy Build. 2010, 42, 1619–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakilinezhad, R.; Khabir, S. Evaluation of Thermal and Energy Performance of Cool Envelopes on Low-Rise Residential Buildings in Hot Climates. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 72, 106643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabaieh, M.; Wanas, O.; Hegazy, M.A.; Johansson, E. Reducing Cooling Demands in a Hot Dry Climate: A Simulation Study for Non-Insulated Passive Cool Roof Thermal Performance in Residential Buildings. Energy Build. 2015, 89, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goia, F. Search for the Optimal Window-to-Wall Ratio in Office Buildings in Different European Climates and the Implications on Total Energy Saving Potential. Sol. Energy 2016, 132, 467–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathirana, S.; Rodrigo, A.; Halwatura, R. Effect of Building Shape, Orientation, Window to Wall Ratios and Zones on Energy Efficiency and Thermal Comfort of Naturally Ventilated Houses in Tropical Climate. Int. J. Energy Environ. Eng. 2019, 10, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didwania, S.; Garg, V.; Mathur, J. Optimization of window-wall ratio for different building types. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 42, 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, D.; Chan, M.; Deng, S.; Lin, Z. The Effects of External Wall Insulation Thickness on Annual Cooling and Heating Energy Uses under Different Climates. Appl. Energy 2012, 97, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunoro, S. Passive Envelope Measures for Improving Energy Efficiency in the Energy Retrofit of Buildings in Italy. Buildings 2024, 14, 2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, K.; Sriti, L. The Effects of Envelope Building Materials on Thermal Comfort and Energy Consumption. Case of Hot and Dry Climate. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Contemporary Affairs in Architecture and Urbanism-ICCAUA, Istanbul, Turkey, 9–10 May 2019; Volume 2, pp. 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, R.A.M.; Rehumaan, S.F.K. Preliminary Study to Show the Effect of Building Envelope Materials on Thermal Comfort of Buildings Located in Hot Humid Climate. World J. Eng. Technol. 2022, 10, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihm, P.; Krarti, M. Design Optimization of Energy Efficient Residential Buildings in Tunisia. Build. Environ. 2012, 58, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saadi, S.N.; Al-Jabri, K.S. Optimization of Envelope Design for Housing in Hot Climates Using a Genetic Algorithm (GA) Computational Approach. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Homoud, M.S. The Effectiveness of Thermal Insulation in Different Types of Buildings in Hot Climates. J. Therm. Envel. Build. Sci. 2004, 27, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.