Abstract

Reality-capture has made point clouds a primary spatial data source, yet processing and integration limits hinder their potential. Prior reviews focus on isolated phases; by contrast, Smart Point Clouds (SPCs)—augmenting points with semantics, relations, and query interfaces to enable reasoning—received limited attention. This systematic review synthesizes the state-of-the-art SPC terminology and methods to propose a modular pipeline. Following PRISMA, we searched Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar up to June 2025. We included English-language studies in geomatics and engineering presenting novel SPC methods. Fifty-eight publications met eligibility criteria: Direct (n = 22), Indirect (n = 22), and New Use (n = 14). We formalize an operative SPC definition—queryable, ontology-linked, provenance-aware—and map contributions across traditional point cloud processing stages (from acquisition to modeling). Evidence shows practical value in cultural heritage, urban planning, and AEC/FM via semantic queries, rule checks, and auditable updates. Comparative qualitative analysis reveals cross-study trends: higher and more uniform density stabilizes features but increases computation, and hybrid neuro-symbolic classification improves long-tail consistency; however, methodological heterogeneity precluded quantitative synthesis. We distill a configurable eight-module pipeline and identify open challenges in data at scale, domain transfer, temporal (4D) updates, surface exports, query usability, and sensor fusion. Finally, we recommend lightweight reporting standards to improve discoverability and reuse.

1. Introduction

A point cloud is a set of three-dimensional (3D) samples that captures the geometry of objects or environments [1]. In remote sensing, point clouds are generated via surveying techniques to model natural landscapes and the built environment. Each point is specified by Cartesian coordinates (x, y, z) and may carry additional attributes depending on the sensing system—e.g., color, surface normal, intensity, number of returns, GPS time, and scan angle [2]. Although often treated as intermediate products, point clouds are central to documenting as-built conditions and to enabling downstream modeling and analysis because of their spatial precision and geometric richness [3].

The growing adoption of reality-capture technologies has made point clouds a primary source of spatial data. Common acquisition platforms include active sensors such as Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR)—used in airborne laser scanning (ALS), terrestrial laser scanning (TLS), and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs)—as well as other depth-sensing devices. These modalities support a broad range of applications spanning design and construction [4], topographic mapping [5], environmental monitoring [6], infrastructure development [7], and cultural heritage preservation [8]. More recently, passive imaging systems have also been utilized to generate point clouds through photogrammetry and structure-from-motion (SfM) techniques using Red-Green-Blue (RGB), infrared, or thermal imagery [9]. With increased accessibility and lower costs, these tools enable rapid, high-resolution data acquisition [10]. However, raw point clouds frequently contain noise and outliers, exhibit occlusions and irregular sampling density, and produce huge files—complicating storage, processing, and data exchange [11].

Point cloud processing transforms raw data into structured, information-rich representations through algorithmic workflows and data integration. Processed outputs typically incorporate attributes that facilitate analyses and data exchange. Beyond purely geometric operations, many tasks require integrating domain semantics so that objects and relations are machine-interpretable. Semantically enriched point clouds enable automated reasoning and task-specific applications, such as scene interpretation [12]. However, given the high dimensionality of point clouds, processing demands complex, automated methods capable of interpreting geometric structure and semantic context.

The Smart Point Cloud (SPC) concept has emerged to address these challenges by embedding intelligence into point cloud workflows: a semantically structured point cloud model that encodes domain knowledge and supports machine-interpretable reasoning, automation, and decision support [13]. Early SPC work largely extended conventional pipelines—using geometric and spectral features for classification, followed by semantic labeling to integrate knowledge. For example, a web-based prototype on heritage tesserae stones demonstrated interactive streaming with real-time semantic annotation, signaling the first shift toward SPC ontology-based interpretation while remaining close to traditional workflows [14]. Since then, efforts have broadened SPC beyond static classification toward lifecycle-aware systems that support incremental updates, context-aware interpretation, and links to external knowledge bases (e.g., information models or Digital Twins (DTs). In these settings, point clouds evolve into continuously updated digital assets that participate in analysis, simulation, and decision-making across capture, construction/operation, and maintenance phases.

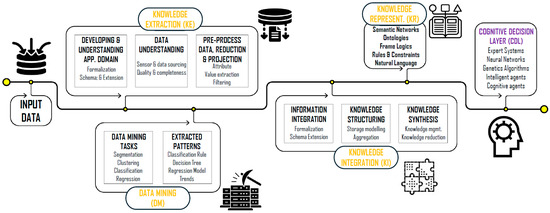

Figure 1 summarizes three pillars that enable this progression: Knowledge Extraction (KE), Knowledge Integration (KI), and Knowledge Representation (KR), which together address challenges in structuring, linking, and interpreting large, multi-source datasets [15]. KE involves data preparation, Data Mining (DM) tasks for information, and developing new knowledge from data [16]—feature extraction, segmentation, clustering, and classification [17]. KI synthesizes and aligns the multiple knowledge sources, understanding, representing, and layering them by domains. KR then formalizes this knowledge—e.g., ontologies and rules expressed in machine-readable languages—to enable constraint checking, logical inference, and workflow automation with reduced human input [2]. The decision-making and inference functions that consume these KR fall in the Cognitive Decision Layer (CDL).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for developing intelligent virtual environments, illustrating the transition from Knowledge Extraction to automated reasoning via the Cognitive Decision Layer (CDL)—Adapted from [15].

Despite progress, SPC remains a fragmented research area, with inconsistencies in terminology, data sources, and processing methods. To the best of our knowledge, no recent Systematic Literature Review (SLR) has comprehensively synthesized developments in this domain. This study addresses this gap through a rigorous SLR aimed at unifying knowledge and guiding future research. The objectives of this review are to (i) identify and categorize SPC-focused studies; (ii) evaluate consistency in terminology, definitions, and conceptual frameworks; (iii) extract and compare data types, processing methods, and workflows; and (iv) identify open challenges and propose future research directions. In response to these objectives, this study provides the following:

- An evidence-backed overview of SPC workflows situated within traditional point cloud processing, covering data types, pre-processing, and semantic integration;

- A comparative taxonomy of SPC definitions, methodologies, datasets, and tools across application domains;

- A prioritized agenda of SPCs’ unresolved challenges and opportunities to guide future innovation in remote sensing and spatial data science.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces traditional point cloud workflows and positions SPC in context. Section 3 details the SLR methodology. Section 4 presents the review’s synthesis and findings. Section 5 discusses the results in light of the research questions. Section 6 outlines open challenges and future research directions. Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Traditional Point Cloud Processing and SPC Shift

Point cloud processing is foundational in remote sensing as datasets grow denser and more complex [18]. Typically performed at the point level, it mitigates noise, non-uniform density, and missing semantic context to improve geometric fidelity and downstream interpretability [19]. Despite extensive research, point cloud processing remains an ill-posed problem—solutions can be non-unique, sensitive to perturbations, or fail to converge [20].

Processing is integral in almost all scenarios. For example, it supports the integration of heterogeneous datasets, environment updates via change detection, and accuracy refinement through robust registration and filtering. With auxiliary data, it also enables semantic enhancement, transforming raw points into analyzable representations suitable for modeling, decision-making, and automation [21].

From a remote sensing standpoint, Che et al. [22] categorize core data processing tasks into four stages—feature extraction, segmentation, object recognition, and classification—a sequence that underpins semantic interpretation. In point cloud contexts, Abreu et al. [23] propose a pipeline that begins with data collection (including planning and attribute selection), followed by the processing steps such as classification and modeling. Effective deployment of these workflows also requires scoping application goals, selecting datasets/algorithms, and applying appropriate pre-processing [2]. To harmonize different views, we propose a generalized six-stage workflow for traditional point cloud processing, shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Generalized six-stage workflow for traditional point cloud processing, from acquisition through data modeling and application-specific structuring.

The workflow proceeds with S1 Acquisition, where point clouds are captured using sensors such as LiDAR or photogrammetric cameras. Collection parameters are also configured at this stage according to environmental and project-specific requirements (platform, trajectory, overlap, exposure). This is followed by S2 Registration, where multiple scans are aligned into a common frame using feature-based or Iterative Closest Point (ICP)-style methods, optionally constrained by Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS)/Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU). S3 Pre-processing then improves data quality through operations such as outlier removal, denoising, subsampling, and error correction.

It should be noted that the relative ordering of S2 Registration and S3 Pre-processing depends on sensing modality and workflow design. For example, in ALS/Mobile Laser Scanner (MLS), an initial trajectory solution (e.g., GNSS/IMU, or Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM)) provides a first registration during acquisition; most pre-processing then occurs afterward in the unified frame; while in TLS, two patterns are common: (i) light per-scan pre-processing (e.g., outlier removal, subsampling) to ease overlap detection, followed by registration and then global pre-processing if needed; or (ii) register first, then apply global pre-processing. In this review, we discuss steps and algorithms by function, while acknowledging that, operationally, steps may interleave.

S4 Segmentation partitions the cloud into coherent regions, supported by Feature Extraction, which derives attributes such as curvature, eigen-features, local descriptors, or learned embeddings for pattern recognition. In S5 Classification, instances of segmented entities are localized (object detection/instance segmentation), and semantic labels are assigned using methods like rule-based systems, Machine Learning (ML) models, or manual annotation. Finally, S6 Data Modeling (and Structuring) maps labeled entities to application schemas (e.g., Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) for Building Information Modeling (BIM), City Geography Markup Language (CityGML) for urban models, domain taxonomies for heritage) and packages them for the Application Layer. In traditional workflows, these outputs feed application-specific analytics; in SPC settings, once formalized via KR, they enable CDL functions for automated reasoning.

While this traditional pipeline yields structured geometry, semantic depth and machine-interpretable knowledge are limited. The SPC paradigm augments the workflow via Semantic Enrichment, KI, and KR—typically injected during S4–S6—to enable rule- or learning-based reasoning, automation, and context-aware analysis (Table 1). We map the six stages to the SPC pillars as follows: S4–S5 correspond to KE, with S1–S3 for preparation; Semantic Enrichment and KI occur primarily during S6; and KR is formalized during/after S6 and connects to the CDL for automated reasoning.

Table 1.

Comparative summary of traditional processing vs. SPC-based approaches.

As summarized in Table 1, SPC extends the conventional pipeline by incorporating intelligence through KI and KR, facilitating deeper contextual understanding and enabling adaptive behavior across the asset lifecycle. This baseline positions the review to pursue the objectives by analyzing how SPC implementations realize enrichment, integrate knowledge, and formalize KR across domains in Section 4.

3. Systematic Literature Review (SLR) Methodology

SLRs follow transparent, protocolized procedures to ensure methodological reliability and comprehensive coverage [24]. Guided by the SLR model of Xiao et al. [25] and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [26], we tailored a six-phase workflow for our review (Table 2). The protocol was not registered/published.

Table 2.

Methodological framework for the Systematic Literature Review (SLR) on Smart Point Cloud (SPC), outlining six phases from review question framing to evidence synthesis.

3.1. Review Questions

We formulated six research questions (RQs), grounded in the study objectives and initial scoping of the literature. Table 3 lists the RQs guiding data collection and synthesis.

Table 3.

Research questions guiding the SLR on SPC studies.

3.2. Keyword Selection Strategy

Effective keywording determines the relevance, completeness, and manageability of the corpus. An exploratory search using “Smart Point Cloud” [27] yielded 20 candidate terms (Table A1). After screening for relevance to the research objectives, broader algorithmic terms (e.g., ‘Point Cloud Processing’) and narrow applications (e.g., ‘Object Labeling’) were excluded for lacking the data-model focus of SPC. We retained three core themes covering 11/20 candidates, providing a focused yet inclusive search scope:

(1) “smart point cloud”, (2) “intelligent point cloud”, and (3) “rich point cloud”.

3.3. Literature Search Strategy

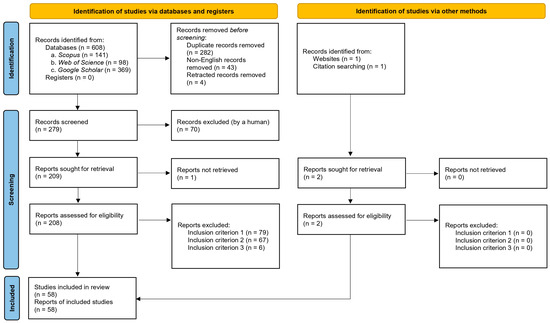

Following PRISMA 2020 [26], we used three identification techniques: (1) structured database searches, (2) backward snowballing (cited references), and (3) forward snowballing (citing references) [25]. Additionally, the authors’ domain expertise contributed to identifying key researchers and relevant terms, as recommended in [28]. Searches placed no date limits, and the last search was in June 2025. A PRISMA flow diagram is in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for the systematic review summarizing identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion.

Primary databases included Scopus [29] and Web of Science [30], for indexing reliability. Google Scholar [31] was also included to capture grey literature and broader conference coverage. Query strings (Table A2) were constructed using standard Boolean operators and exact-phrase matching. The search was then conducted in two phases: (1) title-based search across all three databases, and (2) full-text search on Google Scholar using the broader phrase “Smart Point Cloud” (Protocol and results summary in Table A3).

3.4. Screening and Eligibility

3.4.1. Criteria Development

Inclusion/exclusion criteria (Table 4) were designed to reflect the RQs and ensure topical relevance, rigor, and recency. We included peer-reviewed journals, books, book chapters, conferences, theses, preprints, and other grey literature where relevant.

Table 4.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for screening and eligibility.

3.4.2. Screening Procedure

Screening involved exhaustive manual verification of all retrieved records from the searches without arbitrary cut-offs. First, non-English and retracted items were removed. Duplicates across databases were also eliminated, retaining only the earliest indexed version. Screening then followed four sequential steps:

- Title screening for topical relevance (Criterion 1);

- Abstract screening for relevance and methodological alignment (Criteria 1–2);

- Full-text screening for alignment with objectives and inclusion criteria;

- Recency screening to keep the most recent version by the same authors (Criterion 3).

The core set was then seeded with the authors’ domain expertise for relevant but potentially overlooked seminal studies identified during the research framing, after which backward and forward snowballing were applied. All additional candidates underwent the identical screening and eligibility criteria above. Primary screening was performed by the lead author and a random 20% subset independently verified by the co-authors to ensure reliability, resolving discrepancies via consensus.

3.5. Information Extraction and Synthesis

As Chigbu et al. [32] emphasize, effective reviews are guided by a focused analytical lens aligned with their objectives. Guided by the RQs, we extracted specific data items from each included study, categorized into five domains:

- Metadata: (1) year; (2) publisher; (3) study region; (4) keywords.

- Research scope: (5) objectives; (6) SPC definition; (7) application domain.

- Data and Processing: (8) data types and acquisition; (9) point cloud pipeline phases addressed (S1–S6, see Section 2); (10) methods used at each phase.

- Implementation: (11) software/tools; (12) evaluation metrics.

- Outcomes: (13) findings; (14) linkage to RQs 1–6; (15) limitations.

The lead author extracted data using a standardized Microsoft Excel form, with 20% cross-verified by co-authors to minimize subjectivity (discrepancies resolved via consensus). Missing items were marked “Not Reported” rather than inferred.

Data were synthesized narratively, grouping studies by SPC contribution, pipeline stage, and RQs. Trends and characteristics were visualized via tabulation and distribution plots. Furthermore, we qualitatively explored methodological heterogeneity by analyzing performance variations across acquisition modalities, processing algorithms, and tools.

4. SLR Results: SPC Definition and Methods

Our systematic search—applying all inclusion and exclusion criteria—yielded a final set of 58 publications, detailed in Table A4. For analytical clarity, we introduce a three-way classification used throughout Section 4:

- Direct (n = 22): Studies that explicitly define, propose, or architect a framework (or a specific component thereof) clearly labeled as a “Smart Point Cloud”.

- Indirect (n = 22): Studies that reference the SPC concept and implement its core capabilities but do not explicitly apply the “Smart Point Cloud” label to their own work.

- New Use (n = 14): Studies that utilize the specific phrase “smart point cloud” but refer to unrelated concepts rather than the knowledge-integrated data model defined here.

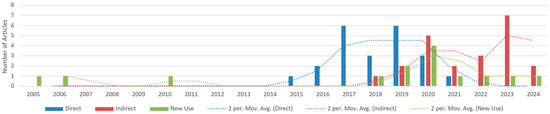

4.1. Overview and Classification of SPC Literature

The temporal distribution of the categorized references is shown in Figure 4, highlighting how SPC-related research evolved. Earlier related expressions predate SPC—“Smart Cloud-of-Points” in 2005 and 2006 within architectural modeling [33,34], and the exact term “Smart Point Cloud” in 2010 for city modeling [35]. The SPC concept examined here was explicitly introduced in 2015 by Poux and Billen [36] and developed through a series of Direct contributions up to 2021. Subsequent publications are predominantly Indirect. This suggests that while core SPC methodologies (e.g., semantic reasoning) are diffusing into practice, recent studies often implement them partially or under alternative labels rather than strict SPC nomenclature, resulting in their ‘Indirect’ classification.

Figure 4.

Temporal distribution of Direct, Indirect, and New Use studies (2005–2024).

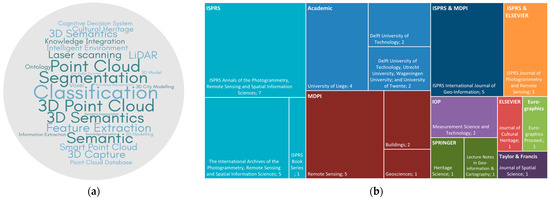

Relevant articles often lack standardized keyword entries despite discussing SPC-like ideas. To examine the semantic landscape, we performed a descriptive keyword analysis of Direct papers (Figure 5a). High-frequency terms include data/source markers (e.g., “3D Point Cloud”, “LiDAR”) and semantic/process terms (e.g., “Ontology”, “Semantics”, “Segmentation”, and “Classification”), underscoring SPC’s emphasis on semantic enrichment within point cloud pipelines. Application cues (e.g., “Cultural Heritage”, “Intelligent Environment”) indicate cross-disciplinary reach.

Figure 5.

(a) Word cloud of high-frequency author keywords in Direct studies; font size reflects frequency. (b) Treemap of publication venues for Direct and Indirect references.

Publication venues cluster within geomatics and remote sensing—most notably the ISPRS Annals, ISPRS Archives, ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, and Remote Sensing—with grey literature outputs from academic outlets (e.g., University of Liège; Delft University of Technology). A treemap of venues appears in Figure 5b.

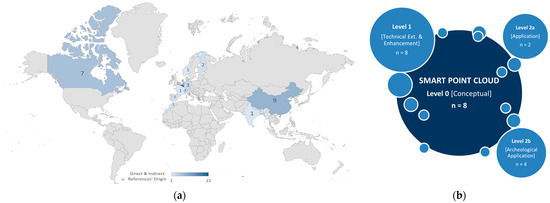

Figure 6a maps the geographic distribution of studies. Europe—especially Belgium (n = 22)—leads SPC publications, reflecting the sustained efforts at the University of Liège, which date back to the concept’s origin in 2015 [36]. China (n = 9) and Canada (n = 7) follow, often through cross-regional collaborations with European institutions. Counts reflect author-affiliation mentions; a paper may contribute to multiple countries. This geographic concentration likely drives another terminological drift: as the concept expands beyond its European origin, researchers often adopt the methodology but favor generic terms (e.g., ‘semantic point clouds’) over the specific ‘SPC’ label.

Figure 6.

(a) Global distribution of Direct and Indirect SPC studies by author-affiliation mentions (non-exclusive counts). (b) Distribution of Direct studies by conceptual focus level.

Our qualitative assessment of the study aims shows recurring goals—automating workflows, reducing processing time, and improving accuracy. To summarize conceptual maturity, Direct contributions were grouped by abstraction level (Figure 6b):

- Level 0: Conceptual/review outlining SPC principles (n = 8; 36.4%) [15,36,37,38,39,40,41,42];

- Level 1: Technical extensions of SPC a pipeline stage/s, (n = 8; 36.4%) [43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50];

- Level 2: Application implementations—general (n = 2; 9.1%) [51,52] and archeological (n = 4; 18.2%) [13,14,53,54].

4.2. SPC Conceptualization and Definitions

Raw point clouds—though rich in geometry—lack semantics, explicit structure, and connectivity, which limits automated interpretation. As outlined in Section 2, early utilization therefore emphasized spatial structuring (e.g., tiling/octrees), segmentation, and manual or rule-based classification. As pipelines matured, multi-source fusion improved completeness and robustness, and time-varying attributes enabled longitudinal analyses. These advances produced semantically labeled point clouds but did not yet establish the relational, queryable, governed data model needed for automated reasoning. This gap led to the Smart Point Cloud (SPC) concept.

An SPC is a queryable, multi-scale point cloud data model that augments geometry with semantics, topology/relations, provenance and uncertainty, temporal/versioning, and application-specific attributes. Where appropriate, it binds to domain ontologies and exposes interfaces for rules and ML to support automated reasoning, incremental updates, and task-specific analytics. An SPC is a representation, not merely a processing pipeline—although SPC pipelines maintain model consistency as data evolve.

Table 5 summarizes the conceptual evolution from raw point clouds to SPCs. To avoid conflating representations with processing, the comparison treats four representations: Raw, Structured (spatial organization without full semantics), Semantic (labeled/attributed but no explicit topology or reasoning interface), and SPC (bundles semantics + relations + indices/Levels of Detail (LoDs) + rich queries + governance/automation).

Table 5.

Conceptual evolution from raw point clouds to Smart Point Clouds (SPCs).

Across both Direct and Indirect strands, the literature converges on SPC as a knowledge-based data model that fuses spatial, semantic, and topological information to support context-aware analysis and decision support. In this vein, Poux and Billen [15] emphasize integrating geometry and semantics for high-level reasoning, while Poux [39] highlights interactive querying, multi-scale visualization, and system-level intelligence.

Infrastructure-oriented work formalizes SPC as a reasoning-ready platform, specifying how geometry and semantics are integrated and exposed through relations and constraints. These contributions establish the structural preconditions—relations, provenance, governance—on which automation can operate.

According to Poux et al. [40,42], SPC transforms raw data into user-specific information models by combining semantic enrichment with adapted processing techniques (e.g., mathematical morphology and image processing algorithms), improving efficiency (e.g., avoiding full conversions) while maintaining consistency as data evolve. Recent work—such as Poux and Ponciano [44]—shows self-learning automating instance segmentation, and Poux and Billen [45] frame SPC as a systematic framework unifying semantic segmentation, connectivity relationships, and domain rules to support automated reasoning and classification.

Beyond labeling, Poux et al. [37] see SPC operating as a data-mining/enabling platform: relations and provenance expose structure in otherwise underutilized point cloud data, turning them into actionable insights. Poux and Billen [36] further underscore SPC’s advantages for intelligent documentation and geospatial analysis, while noting the need for domain-specific refinement to operationalize the broad conceptual framing.

In sum, SPC is a relation-aware, queryable point cloud data model designed for automated reasoning and lifecycle updates.

Our review also identified 14 “New Use” studies, where “smart point cloud” denotes unrelated constructs (e.g., proprietary formats/labels, alternative metrics). These are outside the SPC definition used here but help explain emerging interpretations and terminological drift. Table 6 summarizes these patterns.

Table 6.

Summary of “New Use” meanings of “smart point cloud” beyond SPC.

4.3. SPC Workflow Architecture and Methodological Contributions

The transition from conventional point cloud workflows to SPC systems is both incremental and transformative. While foundational operations—acquisition, registration, pre-processing, segmentation, classification, and modeling—remain essential for geometric fidelity and analysis, they do not, by themselves, impart “smartness” through semantical depth, adaptive behavior, or reasoning capacity.

SPC frameworks build on these foundations by integrating automation, semantic enrichment, and knowledge-based inference—particularly during segmentation, classification, and data modeling. This integration adds contextual understanding that enables advanced analytics, adaptivity, and domain-specific decision support, turning point clouds into intelligent, queryable assets.

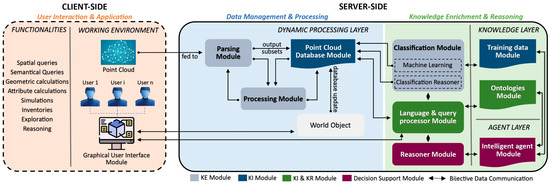

To conceptualize this transformation, Poux [39] proposed a modular SPC architecture with coordinated server-side and client-side components (Figure 7). On the server-side, the Data Management zone operates within a Dynamic Processing Layer, utilizing a parsing module and a processing module (both KE) to partition incoming data and generate functional subsets, which are validated and persisted in the point cloud database module (KI). Above this, the Knowledge Enrichment zone integrates the Knowledge Layer (KI/KR) to augment data using ML models, ontologies, and a language/query processor that exposes semantic interfaces. A reasoner module implements constraint checking and inference, bridging to the CDL. The Agent Layer coordinates autonomous, task-oriented agents for scheduled or event-triggered operations (e.g., re-classification, rule enforcement). Finally, on the client-side (User Interaction zone), a graphical interface supports tasks such as spatial queries, semantic computations, and scenario simulations—enabling collaborative, near-real-time work with semantically enriched 3D data.

Figure 7.

Modular SPC framework visualized in three functional zones: Data Management, handling parsing, processing, and storage; Knowledge Enrichment, where domain ontologies, classification, and agents drive the system’s intelligence (both on server-side); and User Interaction, covering client-side visualization and semantic and spatial interaction. Adapted from [39].

This subsection examines how SPC systems contribute at each stage of the broader workflow, emphasizing where and how intelligence is embedded, what data it uses, and which traditional processing is implemented across the capture-to-use lifecycle.

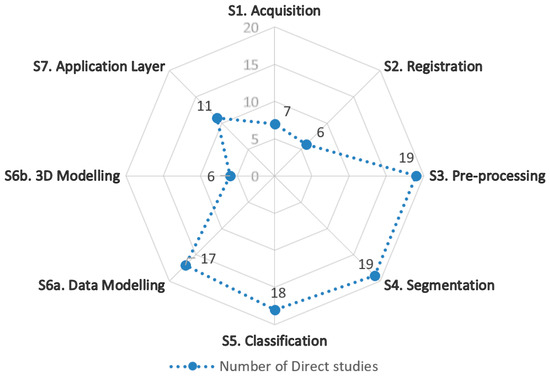

Figure 8 summarizes how Direct studies target each stage. Most implementations concentrate on pre-processing (n = 19), segmentation (n = 19), classification (n = 18), and data modeling (n = 17)—the primary loci for embedding semantics, automation, and reasoning. In contrast, acquisition, registration, and 3D modeling are less represented (each ≤n = 6), highlighting areas where SPC functionality is limited.

Figure 8.

Count of SPC Direct studies per each traditional point cloud workflow stage.

4.3.1. Data Collection and Systems

Data acquisition in geomatics uses one or more complementary techniques to obtain fit-for-purpose results. This typically include establishing control networks for geo-referencing and executing site-specific planning and instrument configuration to manage constraints such as limited visibility, complex terrain, or poor satellite coverage [65].

With advancements, contemporary point cloud recording technologies include laser scanning [5], photogrammetry, and RGB-Depth (RGB-D) imaging [66]. These differ in resolution, accuracy, range, cost, and platform flexibility; sensor choice depends on task requirements, downstream algorithms, and resources. Multi-sensor deployments are also becoming common to compensate limitations—e.g., pairing LiDAR with RGB to add color, or combining airborne and terrestrial platforms for completeness. For SPC, acquisition also seeds provenance (sensor model, scan geometry, GNSS/IMU logs) and attribute channels needed later for semantics and uncertainty.

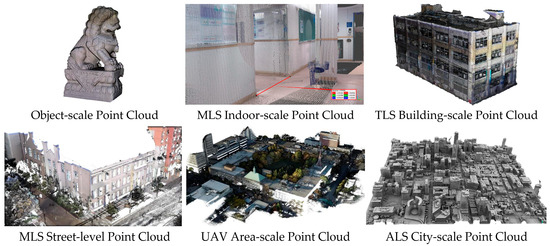

Figure 9 presents visual examples of point cloud datasets acquired using different sensing techniques across various scales, highlighting variation in resolution and detail.

Figure 9.

Examples of point cloud data acquired using different techniques across various scales.

To contextualize acquisition strategies within SPC development, Table 7 synthesizes typical collection methods, characteristics, and their frequency of use in the Direct studies.

Table 7.

Comparative analysis of point cloud acquisition methods and implementation in SPC.

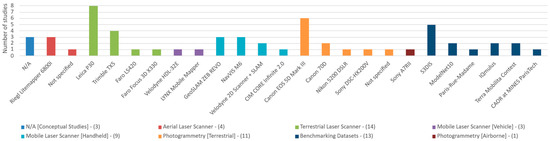

The Direct studies utilized 55 datasets across these modalities, often mixing sources within a single experiment. Figure 10 shows the distribution by sensor/platform, underscoring SPC’s adaptability to diverse inputs.

Figure 10.

Distribution of sensor/platform types across the datasets used in Direct SPC studies (n = 55). Multiple datasets may come from the same study.

While many studies evaluated frameworks on single-source datasets—or multiple datasets independently—(55.6%), multi-source fusion was also common (44.4%), improving resolution, visual richness, and coverage. Fusion of LiDAR and photogrammetry, in particular, can be seen in a few studies, including the following:

- Studies [14,41,53,54] combined Leica P30 TLS for dense geometric precision with Canon EOS 5D Mark III CRP for visual texture in archeology;

- Yang et al. [13] employed CIM CORE Infinite 2.0 handheld MLS, Faro LS420 TLS, and Sony A7RII UAV photogrammetry to document cultural relics across scales;

- Poux et al. [42] integrated Riegl Litemapper 6800i ALS, Trimble TX5 TLS, and image-based Sony DSC-HX200V data for indoor/outdoor heritage building;

- Van Bochove [47] merged ALS for rooftop and topographic mapping, complemented by MLS for façades and street-level detail.

In conclusion, SPC frameworks readily integrate heterogeneous acquisition sources. Strategic sensor selection—guided by precision, cost, and contextual relevance—directly influences data richness and downstream processing, while multi-source fusion aligns with SPC’s goal of building comprehensive, provenance-aware models and with the complexity of real-world environments.

4.3.2. Data Alignment and Integration (Registration, Geo-Referencing, and Fusion)

Registration estimates the transformations that align multiple geospatial datasets—acquired from different positions, platforms, or sensors—into a common spatial frame [67] (Figure 11). When alignment is tied to a geodetic reference (e.g., World Geodetic System 1984 (WGS 84)), it is Geo-referencing, which may occur during acquisition via GNSS, per-scan with targets, or post hoc using Ground Control Points (GCPs). As noted in Section 2, registration and pre-processing may interleave depending on sensor and workflow.

Figure 11.

Example of pairwise registration: two scans (green/blue) aligned into a common frame to produce the fused output.

Meanwhile, Fusion integrates multiple spatial datasets and/or attributes to increase completeness and semantic richness, and can take place in two forms:

- Geometric Fusion (register-then-merge): co-registered datasets of the same format (e.g., point clouds) from different modalities (e.g., ALS + TLS + CRP) are merged to improve coverage and consistency while preserving the native characteristics of each dataset; optional post-fusion duplicate removal or density weighting may be required to reconcile overlaps and sampling differences to produce a coherent output.

- Attribute Fusion (register-then-transfer): heterogeneous sources (maps/images/point clouds) are first co-registered so that units (e.g., pixels, points) correspond one-to-one, enabling per-unit attribute propagation (e.g., colorizing or texturing LiDAR from orthophotos or transferring normals/material cues) to enrich the target dataset.

This subsection focuses on alignment methods used in SPC workflows to prepare data for robust fusion and downstream semantics.

Registration in point clouds typically proceeds in two phases: a coarse step for approximate pose estimate, followed by a fine step that refines alignment to point-level accuracy. Robust registration underpins applications such as autonomous navigation [68], posture estimation [69], and 3D reconstruction [70].

For coarse registration, historical practice relied on manual point pairing or target-based methods. Recent work introduced learning-based approaches that (i) extract features and establish correspondences [71] or (ii) predict transformations end-to-end [72]. These methods are promising at scale and in dynamic environments but remain sensitive to sampling density, scale differences, and the breadth of training data [73].

For fine registration, classical ICP [74] remains dominant, iteratively minimizing distances between corresponding points to compute the optimal transformation per user-defined iterations and thresholds. Variants such as Generalized ICP (GICP) [75] and Normal Distributions Transform (NDT) [76] further improve robustness with noisy or variable density data. However, these methods often rely on a good initialization and may struggle with complex or repetitive structures [77].

Across the Direct SPC corpus, registration is essential for aligning datasets and enabling fusion—where most value accrues—and was found in a supporting infrastructure rather than the primary locus of innovation. Most studies follow typical pipelines: control- or feature-based coarse alignment followed by ICP-family refinement, sometimes with knowledge-guided priors. For example, Poux et al. [42,53] used GCPs and targets for initial geo-referencing, then ICP; Van Bochove [47] similarly adopted ALS as a global reference, co-registering MLS data via GCPs and ICP in succession. Feature-based registration explored by Poux [39], aligning geometric primitives (planes, corners) for coarse lock prior to ICP. Poux et al. [54] further integrated non-uniform rational B-splines (NURBS) surface fitting coupled with ICP to improve accuracy through knowledge-based geometry. Meanwhile, Joosten [48] applied template matching and pose graph optimization (PGO) using 2D map priors, GNSS, and IMU for large-scale alignment. A comparative summary of the Direct SPC study methods is provided in Table 8.

Table 8.

Registration methods reported in Direct SPC studies—suitability, initialization, limitations, and computational cost.

While not a core of innovation in SPC, it should be noted that accurate alignment ensures that relations (adjacency/part-of/connectivity) constructed later on are geometrically valid, and allows provenance and uncertainty to be propagated consistently into the SPC model, supporting KI/KR consistency and reliable reasoning.

4.3.3. Point Cloud Preparation (Pre-Processing)

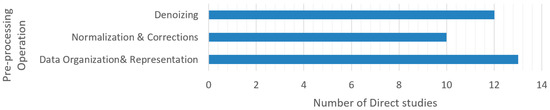

Pre-processing prepares raw point clouds for downstream analysis by stabilizing geometry, harmonizing attributes, and reducing volume without discarding information. These are particularly critical for multi-source fusion workflows: because platforms differ in sampling density and radiometric response—and real scenes contain noise, outliers, and gaps—rigorous normalization is required to make datasets comparable across sources and sessions [78]. For SPC, pre-processing also records provenance (parameters, software) and seeds uncertainty that can be propagated into semantics and reasoning. This subsection summarizes key pre-processing operations reported in the Direct SPC studies (Figure 12) and how they integrate into multi-step flows.

Figure 12.

Distribution of key pre-processing operations reported in the Direct SPC studies.

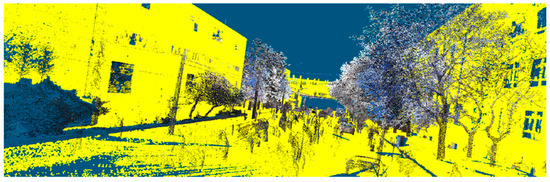

Noise and Artifact Removal—Filtering in SPC is typically the first step, removing spurious points while preserving scene structure (Figure 13). Parameterized filters are common; for example, Kotoula [49] applies Local Outlier Factor (LOF) to improve subsequent Principal Component Analysis (PCA)-based normal estimation and surface-orientation reliability. In SPC pipelines, denoising often precedes alignment/fusion to improve cross-sensor consistency—Poux [39] highlights statistical outlier removal before integrating TLS, MLS, and photogrammetry; Van Bochove [47] removes transient artifacts (vehicles, pedestrians) to reduce overlap conflicts and redundancies.

Figure 13.

Example of denoising through non-ground/building removal in an urban scene.

Normalization and Corrections—Normalization imposes uniform characteristics to improve feature comparability and fusion. Common steps in SPC include density equalization, range-based bias corrections, intensity/radiometric calibration, and normal-orientation disambiguation. Balado et al. [43] emphasize aligning object shape, size, orientation, and density with benchmarks. SPC multi-sensor workflows commonly follow denoising → normalization/correction → alignment → fusion. For example, Poux et al. [14] filter intensity overloads and mixed pixels, apply intensity corrections and geometric alignment, then fuse TLS + photogrammetry; Poux et al. [53] combine denoising, density adjustment, geometric alignment, and full-waveform analysis prior to fusion.

Density control and Organization—Subsampling reduces computational load while preserving morphology and supports hierarchical storage (Figure 14). Approaches in SPC include Middle of Octree (MidOc) subsampling used by Zheng [46] for progressive geometric approximation, followed by denoising, normalization, and redundancy pruning to enable efficient ordering and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) ingestion. At a larger scale, Joosten [48] tiled clouds into 50 × 50 m grids to simplify management before filtering and to derive 2D density histograms for template matching and map alignment. Furthermore, octrees/voxels in SPC serve double duty: (i) as LoD indices for multi-scale visualization, queries, and storage, and (ii) as substrates for superpoint/region graphs that support KI/KR aggregation and constraint reasoning (see Section 4.3.4).

Figure 14.

Octree-based subsampling for density regularization and hierarchical storage.

Takeaways for SPC pre-processing can be summarized as below:

- Denoising is the most frequent and typically first step; along with normalization, both facilitate fusion to ensure cross-sensor geometric/attribute comparability.

- Data organization materially improves storage/runtime and ML ingestion and provides the indices that underpin SPC LoDs and region graphs.

- SPC pre-processing pipelines are composite and sensor-aware; filters and normalizations are tuned to modality and the downstream task.

- Provenance capture (filter types/parameters, residuals) should be written into the SPC’s metadata to support reproducibility and uncertainty-aware reasoning.

4.3.4. Feature Extraction and Hierarchical (Region) Segmentation

Feature extraction computes descriptors that make classes separable and robust to sensor noise, density variation, and viewpoint changes by quantifying local shape, appearance, and context for each point or supervoxel [53]. These descriptors fall into three categories: geometric (normals, curvature, planar/cylindrical fits) capturing shape and orientation [79]; radiometric (RGB/Hue-Saturation-Intensity (HSI) statistics, LiDAR intensity), useful where material/reflectance contrasts exist [80]; and contextual (relative height, neighborhood statistics, adjacency/graph cues, spatial topology) that disambiguate semantically similar shapes by setting [81].

A typical four-step pipeline is used: (1) neighborhood definition per point/supervoxel via fixed-radius (scale-aware) or k-nearest neighbors (k-NN; sampling-aware) search; (2) primitive estimation, fitting local planes and/or running PCA on the neighborhood covariance to obtain normals, curvature, and eigenvalue-based shape indices; (3) descriptor computation aggregating geometric, radiometric, and contextual cues; and, optionally, (4) multi-scale aggregation by repeating across multiple supports and/or octree levels, or by propagating descriptors to supervoxels/segments to balance fine detail with structural context. The neighborhood model thus strongly determines normal/curvature stability and—ultimately—segmentation quality [53].

Segmentation partitions points/supervoxels into meaningful components that support downstream labeling, interpretation, and analysis; it uses the descriptors above to decide which points belong together [23]. Common families include the following: model/primitive fitting (e.g., Hough Transform (HT) [82], random sample consensus (RANSAC) [83]) to fit planes/cylinders and assign inliers—effective for dominant parametric structures but computationally heavier and less robust in heavy clutter or deformation; region growing/connectivity clustering, expanding from seeds whose neighbors exhibit similar features—sensitive to thresholds and neighborhood design [84]; graph-based partitioning, constructing a k-NN or voxel-adjacency graph, weighting edges by feature similarity and spatial smoothness, then optimizing a cut/merge objective (e.g., spectral or normalized-cut variants); and density-based clustering (e.g., density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (DBSCAN), mean shift), which handles noise and non-parametric shapes but is sensitive to scale under variable density.

SPC frameworks emphasize segmentation that captures semantic geometries, relations, and feature similarity while leveraging device-specific, domain-specific, and expert knowledge [37]. In our Direct corpus, 54.5% (12/22) studies [14,15,38,39,40,41,44,45,51,52,53,54] adopt a three-stage hierarchical segmentation design:

- Voxel/Octree Partitioning—All 12 studies above use hierarchical voxel subdivision (octrees) to structure the scene into grid-based indices for efficient storage, retrieval, and feature computation; recursion is controlled by minimum voxel size, maximum depth, points-per-voxel, or application rules (e.g., color thresholds).

Poux et al. [40] introduced a conceptual multi-scale voxel structure supporting diverse data resolutions coupled with preliminary filtering and, later, semantic attributes. Poux et al. [54] extend this to fused LiDAR + photogrammetry with nested octrees to optimize rendering and organization. This stage structures and over-segments the data but does not yet decide semantic groupings.

- 2.

- Feature Extraction—Within the voxel framework, studies employed multiple techniques to compute task-specific cues, for example:

ML-driven graph clustering over voxel neighborhoods, linking adjacent voxels whose descriptor similarity exceeds learned thresholds, consolidating neighborhoods prior to region grouping [39]; PCA-based analysis to derive principal directions and plane normals, often followed by voxel-to-voxel contact (“touch”) topology to assess planarity relations (horizontal, vertical, mixed, neighboring) [39,44,51]; shape descriptors and plane fitting (notably RANSAC) for geometric extraction [14,39,41,52,53,54]; elevation-based separation with Cloth Simulation Filter (CSF) to isolate ground/non-ground [52]; and radiometric cues (RGB/HIS, intensity) to enhance material differentiation—particularly in archeological settings where shape alone is impractical [14,39,41,53,54].

- 3.

- Grouping via Connected Component Labeling (CCL) on a region-adjacency graph (RAG)—The voxel/supervoxel lattice yields a RAG with standard three-dimensional connectivities (6/18/26). Edges are weighted by descriptor similarity (e.g., normals/curvature, radiometry), spatial smoothness, and primitive/topology constraints (collinearity, orthogonality, planar contact). 3D CCL—originally a 2D image-analysis method—then groups nodes into connected elements (“semantic patches”), region units that are spatially and semantically indexed.

Putting these stages together, Poux and Billen [15] describe the SPC mechanism that first organizes points into a voxel space at an octree level set by device-specific parameters. Each voxel is analyzed for features and local similarity to define “Connected Elements”—derived from initial voxelization and feature extraction of primary components (e.g., ground, perpendicular/parallel elements) that act as potential parents. Hybrid voxels (containing multiple potential objects) are further subdivided using surrounding topology/characteristics. The process yields “Semantic Patches”, categorized as pure voxels or leaf nodes. Table 9 summarizes the three stages, inputs, operations, and outputs.

Table 9.

Three-stage hierarchical region segmentation used in the Direct SPC studies.

Beyond this pattern, some studies utilize alternative pipelines: Kotoula [49] combines image-based boundary detection (Canny, Hough) on panoramic imagery with photogrammetric point clouds derived from the same panoramas; 2D segments are re-projected onto the point cloud and refined with 3D HT to enhance edge delineation. Zheng et al. [50] use fixed-radius vertical cylinders as per-point neighborhoods to compute vertical profiles (density/height statistics), facilitating feature extraction. For simpler requirements, Joosten [48] groups points using map-extracted building footprints and buffers, while Yang et al. [13] rely on manual annotation for cultural relics.

Eventually, the resulting semantic patches/regions become the units consumed by knowledge-based classification and reasoning in Section 4.3.5, where domain rules and KI/KR formalize labels and support automation.

4.3.5. Knowledge-Based Classification

We distinguish semantic segmentation (one semantic label per point/voxel) from classification (one label per entity—segment/object or scene). Instance segmentation augments semantic segmentation with instance IDs. Here, we focus on segment/object classification of the regions produced by Section 4.3.4.

The classification stage assigns semantic labels to segments/objects, enabling targeted analyses (e.g., vegetation, buildings, roadways), change detection, and direct use in Geographical Information Systems (GIS)/BIM workflows where typed entities are required [78]. In SPC pipelines, classification benefits from both data-driven learning and knowledge-based constraints derived from device, domain, and expert priors. Manual classification, however, appears in some SPC studies (e.g., [13,47,52]) and can achieve high precision, but it is labor-intensive and scales poorly; these works often advocate automating labeling for complex objects and larger datasets [47].

Beyond manual labeling, learning-based classification includes classical ML models such as Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Random Forests (RF), trained on handcrafted geometric/radiometric/contextual attributes; they scale to large datasets but require careful class-imbalance handling and intensity calibration [85].

Deep learning (DL), on the other hand—point-based (e.g., PointNet/PointNet++), voxel-based (e.g., sparse 3D CNNs), and projection-based (e.g., range/multi-view) architectures—learn features end-to-end but require balanced training data and explicit handling of density variation and domain shift [86]. For example, PointNet/PointNet++ operate on unordered sets with permutation invariance and alignment modules, supporting global (segment/scene) classification [87], while Dynamic Graph CNN (DGCNN) replaces PointNet’s multi-layer perceptron (MLP) aggregation with EdgeConv layers over dynamic k-NN graphs in feature space, treating point clouds as structured graph data composed of nodes and edges to capture local geometric context at multiple layers, although at the cost of model complexity and training parameters [88]. Voxel/projection CNNs leverage spatial hierarchies, learn intricate patterns, and achieve strong accuracy—widely documented in automated classification—but incur quantization/projection trade-offs and potential information loss [89]. In Smart Point Cloud studies, deep backbones are typically configured with global heads to produce segment-level predictions by pooling features across semantic patches (or by applying graph neural networks over the RAG), while noting that the same architectures can be configured with per-point heads for semantic segmentation.

Knowledge-based Classification (rules and morphology)—Rule-based systems use expert rules, geometric/topological constraints, and graph reasoning to assign object types efficiently where domain knowledge can systematically guide decisions. Attributes such as size, shape, orientation, connectivity, and adjacency are encoded as thresholds/rules at the segment/object level to classify entities such as walls, ceilings, and furniture [14,41,45]. SPC studies emphasize semantic enrichment via spatial feature attributes as a core mechanism for structuring point clouds [42]. For instance, studies [43,48,49] explored morphological and rule-based detectors for specific classes, deploying morphological opening/closing and geometric heuristics to isolate patterns such as steps (stairs), slender verticals (poles), or tubular forms (pipelines)—achieving high precision in constrained scenes but limited generality. In parallel, Zheng et al. [50] and Poux et al. [37] highlighted the effectiveness of classical ML (SVM/RF), or CNNs, as in [46], training on attributes such as reflectance, elevation variance, and point density; improving scalability while remaining compatible with domain knowledge.

Ontology-driven Classification—Ontology-driven approaches formalize domain knowledge in structured machine-interpretable ontologies (classes, relationships, and constraints)—using standards such as Web Ontology Language (OWL)—to support logical reasoning and consistency checking; these are widely used in SPC [15,39,40,44,51,53,54], often with SPARQL Protocol and Resource Description Framework (RDF) Query Language (SPARQL) for querying. This extends knowledge-based methods by enabling schema-aware inference and traceable decisions, with reported gains in tasks such as material property analysis and geometric feature extraction. Coupled with a self-learning mechanism, SPC classification proceeds in two steps:

- Rule Definition: Expert-prescribed semantic rules define each class and are tailored to data and sensor characteristics; variations in expected and actual representations (e.g., geometric discrepancies due to occlusion) may reduce accuracy;

- Rule Refinement: To address such inaccuracy, rules are dynamically adjusted from the data itself in this step—adjusting the initial rules by analyzing characteristics shared among similar classified segments—to make criteria more robust. For example, computing confidence intervals over numeric region properties (sizes, heights) for segments of the same class [37].

Hybrid (neuro-symbolic) Classification—Combining ML/DL predictions with ontology/rule constraints can further improve consistency, especially on long-tail classes. A proposed pattern is as follows: (i) ML to propose labels (with confidence) for semantic patches; (ii) ontology/rules to validate/correct labels using RAG relations (e.g., doors on walls, floors under walls) and cardinality/compatibility constraints; (iii) conflicts are to be resolved via policy (e.g., rule-overrides, confidence thresholds); and (iv) provenance and confidence are written to metadata for auditability and downstream reasoning.

Table 10 compares the main classification families in the Direct SPC studies by suitability, accuracy, inputs, and computational cost.

Table 10.

Comparative characteristics of classification approaches in Direct SPC studies.

In conclusion, SPC classification typically operates on semantic patches/regions from Section 4.3.4, with graph-based reasoning over a RAG to enforce relational constraints. Neuro-symbolic hybrids can use ontological constraints to validate/correct ML predictions, improving robustness on rare classes. Classification outputs should persist labels, confidences, rule traces, and conflicts in SPC metadata to support auditability and further reasoning. Performance metrics are discussed in Section 4.6.

4.3.6. Three-Dimensional Models vs. SPC Data Models

The modeling stage turns processed point clouds into an application-ready representation via: (1) a geometry-centric path that reconstructs explicit or implicit surfaces for editing, simulation, and exchange; or (2) a data-centric path that retains points as the primary geometry and adds semantics, relations, and indices for reasoning and analytics. Modeling thus determines what is represented (surfaces vs. enriched points), how it is organized (hierarchies/LoDs), and how it interoperates with external systems. This subsection corresponds to S6: Data Modeling in Section 2 and consumes the segmented regions from Section 4.3.4 and the labels from Section 4.3.5.

In the geometry-centric path, explicit 3D models store surfaces directly as polygonal meshes or parametric primitives (e.g., Bézier, NURBS), while implicit models define surfaces as level sets of a volumetric function (e.g., Poisson, signed-distance fields (SDFs)), from which meshes are extracted as needed. Although explicit reconstructions are compact and highly editable for Computer-Aided Design (CAD)/BIM, inferring stable control points/primitives from noisy or incomplete scans is challenging, whereas implicit reconstructions yield watertight, smooth surfaces but may over-regularize fine details [51,90]. SPC data models may combine both ideas while retaining points as the source of truth. Table 11 contrasts the two paths.

Table 11.

Geometry-centric 3D modeling vs. data-centric SPC data models.

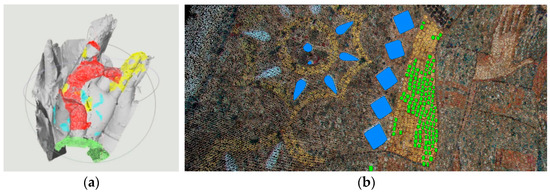

- Three-dimensional Models (geometry-centric)—Surface-based models remain essential in some SPCs where downstream tools or standards require surfaces/solids. For example, Yang et al. [13] apply 3D modeling to support mesh-based analysis and virtual restoration within an SPC framework (Figure 15a); Van Bochove [47] generates high-resolution façade and roadway polygon meshes from multi-source point clouds; and Poux et al. [51] use context-aware procedural modeling (informed by ontologies and shape matching) to integrate voxel-organized point clouds with parametric assemblies across multiple LoDs, improving recognition and reconstruction.

Figure 15. (a) A geometry-centric 3D mesh with downstream damage analysis. Adapted from [13]. (b) Query with results executed directly on enriched points in SPC framework. Adapted from [53].

Figure 15. (a) A geometry-centric 3D mesh with downstream damage analysis. Adapted from [13]. (b) Query with results executed directly on enriched points in SPC framework. Adapted from [53]. - SPC Data Model (data-centric)—Most SPC studies avoid full mesh generation, focusing instead on semantic enrichment and structured point clouds. With semantic patching—organizing segmented points into attribute-bearing units—introduced by Poux et al. [42], and the extension via hierarchical aggregation to form objects and relations as suggested by Poux and Billen [15,45], studies like Kharroubi et al. [52] and Zheng [46] validated direct, out-of-core rendering and interaction over these enriched point clouds; further work (e.g., Poux et al. [37,40,54]) demonstrated reasoning/querying over SPC data in practical applications (Figure 15b).

Hierarchical Tiers: SPC data models commonly adopt multi-tier layers that align with Section 4.3.4 and Section 4.3.5 [46,48]: classifying data into essential strata and advancing to contextual interrelations and domain-specific ontology integrations at elevated tiers. Poux and Billen [15,45] delineate point cloud representation with Level 0 (L0) = semantic patches (Primary elements: over-segmented, attribute-bearing regions), Level 1 (L1) = connected elements (Secondary elements: aggregates constrained by topology/relations), and Level 2 (L2) = domain objects (Transitional elements: ontology instances with roles/relations). These tiers encode explicit relations (e.g., part-of, adjacentTo, constraints) and support element-level queries and visualization (e.g., roof vs. façade layers) [37,40,53].

Data Management and Querying: Operational SPCs require a three-layer design: (i) physical organization, (ii) logical schema, and (iii) access/query. The physical layer uses octree/tiling as an LoD/storage index for out-of-core access (e.g., Potree-style layouts used in [13,52]). The logical schema stores attributes and provenance per L0/L1/L2 entity and formalizes relations (e.g., part-of, adjacentTo, constraints) in an ontology/typed graph; examples include Unified Modeling Language (UML)-based schemas as used by Kotoula [49], and voxel/patch-centric Point Cloud Database Management System (PC-DBMS) designs in Poux et al. [51,54]. The access/query layer pairs Structured Query Language (SQL) (tabular attributes/joins) with SPARQL (schema-aware queries and reasoning); hybrid models such as Multiple Interpretation Data Model (MIDM) proposed by Billen et al. [41] co-locate both, enabling multi-view access and inference. These designs scale storage and query while preserving the semantics, relations, provenance, and uncertainty that SPC requires.

To summarize, a 3D model path is needed when downstream delivery mandates surfaces/solids (CAD/BIM/CityGML, simulation, fabrication), while an SPC data model is preferable for rapid updates, large-scale analytics, uncertainty retention, or schema-aware search/reasoning. We suggest that systems can combine both: maintain an SPC for enrichment and analytics, then export targeted surfaces or parametric assemblies only where the delivery requires them.

4.4. SPC Applications and Use Cases

Point cloud data powers many domains (mapping, Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC)/Facilities Management (FM), heritage, environment). Here, we focus on what SPC adds in practice—semantics, queryability, reasoning, lifecycle updates, and uncertainty retention—drawing on evidence from the review corpus. Table 12 summarizes SPC’s value by domain; corpus-grounded vignettes follow.

Table 12.

SPC applications summarized by domain (evidence from Direct/Indirect studies).

Urban planning and Development—SPCs in urban planning move beyond geometry-only layers by encoding classes (building, roof, road) and relations (adjacentTo, within) together with height rules, enabling planners to run volumetric analysis such as zoning, height, and adjacency checks as well as line-of-sight (LoS) and solar exposures scoped to semantic classes rather than raw points. Practical implementations, as in Poux and Billen [15] and Van Bochove [47], combine multi-source data for comprehensive coverage, preserve provenance of sources and parameters, and can pass rule-checked results into GIS for scenario testing and impact assessment—yielding compliance flags and annotated alternatives for planning decisions. Visualization products can further communicate these semantically filtered scenarios to non-expert audiences, making complex spatial relationships accessible for public and stakeholders’ engagement.

Cultural Heritage—SPC pipelines in heritage transform point clouds into multi-scale semantic patches aggregated into domain objects with condition and temporal attributes as well as uncertainty, producing queryable, provenance-aware archives for targeted restoration, and longitudinal monitoring, as in [13,15]. Interactive systems such as Poux [39] further demonstrate real-time navigation and semantic queries (e.g., by material or condition) with multi-LoD inspection, allowing curators to track changes across campaigns and to document decisions with explainable, rules-checked outputs.

AEC and FM—Within AEC and Facilities Management, SPC models type assets such as walls, slabs, and mechanical, electrical, and plumbing (MEP) components, and then drives deviation analysis and scan-to-BIM consistency checks directly over semantically filtered regions. Image/photogrammetry-enriched point clouds combined with SPC rules (e.g., cylinder fitting with domain thresholds as implemented by Kotoula [49]) support reliable pipe and utility localization and attribute queries for maintenance and safety workflows in manufacturing settings. Geometry-centric deliverables (with SPC retained as the source of truth for enrichment, analytics, and updates) are also demonstrated by Poux et al. [51], applying reverse engineering for furniture modeling to support analysis and prototyping. Van Bochove [47] further integrated SPCs with BIM systems in indoor environments, supporting issue lists and work orders grounded in explainable criteria to improve maintenance scheduling, resource management, and lifecycle monitoring of building components. These efforts can be further explored in construction monitoring through automated as-built versus design diffs to identify discrepancies in project elements and timelines, facilitating early corrections and improving project accuracy.

Transport and Roads—Corridor-scale SPCs produce street-asset inventories in which signs, poles, guardrails, and related fixtures are typed and logically anchored to carriageways with placement and clearance rules, enabling automated quality assurance (QA) for completeness and violations [46]. The same semantics can also support road-surface classification and visibility/proximity checks for sightlines and obstacles inside GIS, yielding prioritized maintenance maps and safety interventions traceable to the SPC labels and constraints used to generate them [48].

Environment and Natural Resources—In environment and natural resources, knowledge-based SPC rules improve ground/non-ground separation and canopy stratification to derive digital terrain models (DTMs)/canopy height model (CHM), while temporal stacking with uncertainty supports change and volume analysis for erosion, stockpiles, and vegetation. Additionally, as highlighted in [39], full-waveform attributes further enrich SPC features with material cues that sharpen classification and monitoring fidelity, resulting in risk layers and analytical products that carry explicit confidence metadata for conservation and resource management decisions.

4.5. Implementation Tools Analysis

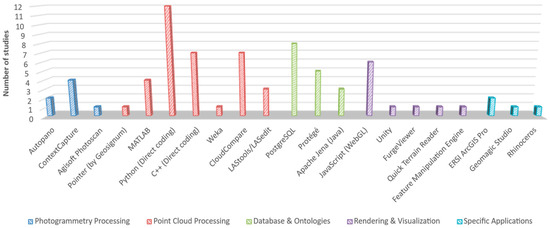

SPC studies rely on a mix of photogrammetry suites, point cloud processing libraries, databases/ontology stacks, and rendering frameworks. This diversity improves fit-for-purpose deployments but can hinder portability. Here, we synthesize the tools reported across the studies and how they are used within SPC workflows, offering a sensible default stack for future implementations. Figure 16 summarizes adoption by category; Table 13 consolidates representative libraries and stacks.

Figure 16.

Software used in the Direct SPC studies, grouped by area of use. Bars show the number of studies reporting each tool.

Table 13.

Use and associated libraries/languages of software identified in the Direct SPC Studies.

4.5.1. Photogrammetry Processing

Studies producing image-based point clouds most frequently used Agisoft Metashape (formerly PhotoScan) and ContextCapture for dense reconstruction and orthophoto generation [14,42,53]; with Autopano for panoramic stitching where relevant [49]. Choices were typically justified by reconstruction robustness, control over camera models, and batch automation.

4.5.2. Point Cloud Processing

GeoSignum Pointer (reported only in [47]) is a government cloud platform that covers ingestion, pre-processing, inspection, registration testing, and targeted feature detection for ALS/MLS datasets. Its end-to-end hosting simplifies workflows, though reliance on the provider’s cloud can constrain access and portability.

For general coding stacks, Python was the orchestration language in ~55% of papers (e.g., Refs. [45,51,54]) given its rich ecosystem (e.g., NumPy, and Open3D) for voxelization, segmentation, classification, and data modeling. However, its limited execution speed in real-time implementations prompted some studies such as [39,40] to hand off hot spots to C++ for compute-intensive kernels (~32%), using PDAL, GDAL, and PCL, keeping Python for pipeline control. MATLAB (language and software) also appears in ~18% (e.g., Refs. [43,46]), mainly for prototyping and classical classifiers (e.g., k-NN), sometimes alongside Python for numerical/image operations [15,49].

Among desktop tools, CloudCompare is the most common workbench (31.8%; e.g., Refs. [39,47,52]) for interactive registration, segmentation trials, inspection, and visualization—its open access and broad feature set make it a versatile academic option. For pre-processing, LAStools/LASedit found useful for thinning/manipulation (13.6%; e.g., Refs. [46,47]), and Feature Manipulation Engine (FME) used for format/attribute extract, transform, and load (ETL) into downstream systems.

4.5.3. Database and Ontologies

Ontology tooling centers on Protégé software for ontology authoring and descriptions (22.7%, e.g., Ref. [15]) using OWL/OWL2 over the RDF graph model, with built-in SPARQL querying language support and pluggable description-logic reasoner engines (commonly Pellet). Similarly, Apache Jena—a Java framework—also appears in some studies (13.6%, e.g., Ref. [51]) to author OWL vocabularies, interconnect ontologies, and employ the RDF model and SPARQL queries and rule-based inference.

For geospatial storage and querying, PostgreSQL is the sole DBMS reported (36.4%; [37,40,41,47,49,54]), typically extended with PostGIS (for geospatial data) and PgPointCloud (for point storage and management). Spatial indexing relies on Generalized Search Tree (GIST) to accelerate window/nearest operations in retrieval [53]; PgPointCloud’s tiling/blocking aligns with the octree/LoD organization described earlier.

With the help of Python libraries, typical integration glue consists of psycopg/psycopg2 for DB access and RDFLib or SPARQLWrapper for ontology operations; unique values link table rows (e.g., semantic patches, connected elements) to ontology instances, allowing metadata captured in SQL to be surfaced to the knowledge layer. While effective, reported PostgreSQL limitations include index build/maintenance times and input/output (I/O) for very large clouds, plus the need for substantial database/spatial expertise [49]. At scale, we suggest that teams keep numerically heavy operations in SQL while materializing schema-specific subsets to RDF for SPARQL/OWL checks—preserving performance without sacrificing explainability.

4.5.4. Rendering and Visualization

In addition to the widely used CloudCompare for local visualization and analysis, software like FurgeViewer [46] offered straightforward access to attributes, and Quick Terrain Reader (QTR) provided robust functionality for comprehensive examinations. Additionally, FME [47] facilitated inspection overlay—joining point attributes with external inspection results/test data and exporting harmonized products to analysis or web stacks. For immersive use, Unity has been used to stage SPCs in VR [52], for selection/measurement on streamed LoD tiles and semantic filtering in-scene; useful for stakeholders’ engagement.

Web-based implementations commonly rely on JavaScript (27.3%) through Web Graphic Library (WebGL) stacks [39]—Potree and Three.js [53]. Libraries such as jQuery, tween.js, and Plas.io were also used to enhance results. While Potree provides hierarchical LoD streaming (octree tiles), eye-dome lighting (EDL), point budgets, and attribute-based styling/filters that map well to SPC affordances (e.g., filter by class/confidence/uncertainty; select at L0/L1/L2), Three.js was used—e.g., Refs. [47,51,54]—for its powerful custom viewers/overlays (semantic highlighting, interaction tools), improving the interpretability and communication of complex spatial information, although it can face performance challenges with dense point clouds. Optimization through server-side tiling/decimation, multi-LoD streaming, point-budget limits, and client-side shader splats/deferred shading are often necessary to maintain interactivity.

In SPC contexts, renderers typically expose SQL/SPARQL-backed queries—e.g., “doors on walls”, “low-confidence” regions, provenance/temporal layers—so visualization acts as an interface to KI/KR rather than a passive viewer.

4.6. Key Performance Metrics and Parameters

This subsection synthesizes how point density, accuracy/precision, and processing time were reported across the corpus, emphasizing trade-offs that matter for SPC pipeline design. Because values across studies are not strictly comparable without aligned datasets, splits, and hardware, we foreground trends and orders of magnitude. Where relevant, we tie observed effects to SPC levers described earlier.

4.6.1. Point Density Considerations

Data density—points per unit area, or its reciprocal, point spacing—shapes what can be reliably detected and how stable features are. Image-based pipelines and laser scanning produce different sampling densities and radiometry, and hence accuracy and robustness. Image-based methods can be rapid and cost-effective for small, detailed targets and yield textured clouds suited to visual analysis, but are less efficient over large extents; laser scanning scales better and delivers higher, more uniform densities, with heavier storage/I/O costs. Hybrid capture that fuses modalities is often recommended to balance strengths. Kotoula [49], however, showed that increasing image overlap, resolution, and count improves point spacing (e.g., ~3 cm spacing ≈ ~1100 points/m2 on planar floors) while achieving ~1 cm registration root mean square error (RMSE) in an indoor SPC application—underscoring the leverage in acquisition parameters.

Furthermore, heterogeneous density and sparse regions degrade classification and inflate the variance of local descriptors; Poux et al. [51] observed that inconsistent densities across combined datasets materially impacted feature extraction and downstream labeling, with dense urban scenes outperforming sparse rural ones, often requiring higher point density. In cultural heritage contexts, Poux et al. [53] reported >95% classification accuracy in areas of high texture quality and low blur, while Billen et al. [41] emphasized the trade-off: higher densities aid recognition but raise processing and storage costs, so density should be matched to the target LoD and task.

SPC-specific mitigations: Pipelines in Section 4.3.3 and Section 4.3.4 address density effects via density-aware neighborhoods (radius scaling), uniformization (e.g., MidOc subsampling) to produce stable multi-LoDs, and normalization/corrections prior to fusion—steps that stabilize features and improve comparability across sensors.

4.6.2. Accuracy and Precision

We group metrics by task, semantic/instance labeling commonly reports intersection-over-union (IoU), F1, and overall accuracy (OA), while geometric tasks (registration/reconstruction) report RMSE against references.

For learning-augmented SPC, Poux and Ponciano [44] report an unsupervised segmentation plus ontology-based categorization with self-learning that forms semantic clusters in a voxel framework; they report very high OA on planar-dominant classes of the S3-DIS dataset (99.99%), but lower effectiveness for structural elements, with non-weighted IoU of 49.9 across 13 classes (vs. 42.2 in [45])—reported among the top tiers of benchmarked DL methods. In indoor “as-built” contexts, Poux et al. [51] noted RMSE of 2–5 cm on non-planar elements relative to reference surfaces, with parametric primitive fits under-fitting small deviations; thus, they suggested adding local triangulation/Poisson meshing to improve geometric fidelity. Complementing deep models, Poux [39] showed that supervised pipelines (e.g., PointNet variants with added training data) and domain-specific decision trees can achieve competitive F1 (>85%) on planar-dominant classes. In an SPC heritage application for tesserae recognition, per-class accuracies reached 95% (gold), 97% (faience), 94% (silver), and 91% (colored glass).

SPC-specific levers: Beyond feature design (Section 4.3.4), knowledge-based and ontology-driven constraints (Section 4.3.5)—e.g., rules such as “door adjacentTo wall” or “floor under wall”—help correct or validate ML predictions, improving consistency on long-tail classes without requiring ever-larger training sets. On the geometric side, multi-LoD modeling and queryable provenance/uncertainty (Section 4.3.6) reduce over-regularization and make residuals auditable.

4.6.3. Processing Time Analysis

Runtime reflects scene complexity, cloud size, data layout (tiling/LoD), and implementation/hardware (language, threading, central and graphical processing units CPU/GPU). Poux et al. [51] highlight that processing duration scales with shape complexity, reporting single-threaded classification timings of ~85 s (ModelNet10 dataset), ~32 s (TLS dataset), and ~16 s (S3-DIS) on indoor environments and furniture. Optimized algorithms and efficient data structures can overcome such delays; Poux and Billen [45] reported an automated segmentation throughput of ~1.5 million points/minute, and noted that voxelization is memory-intensive but parallel-friendly. Furthermore, in SPCs step-wise costs vary: in [51], “data mining” to rank and retrieve candidate shapes took up to ~30 s (accelerable via pre-indexing), Constructive Solid Geometry (CSG) operations < 5 s, and the end-to-end pipeline (SPC extraction, multi-LoD modeling, form matching) ~5 min/scene.

SPC-specific levers: The physical organization of data (octree/tiling LoDs, out-of-core access) and selective queries (Section 4.3.6) bound working-set size; Python-for-orchestration plus C++ kernels (PDAL/PCL) and GPU-backed learning stacks (Section 4.5) reduce wall time for heavy stages; and hybrid neuro-symbolic flows (Section 4.3.5) offload parts of the decision process to fast, explainable rule engines, trading expensive retraining for constraint checks.

In conclusion, the synthesis of reported metrics indicates distinct cross-study trends:

- Density Trade-offs: Higher and more uniform density improves feature stability and classification accuracy, particularly in complex heritage or urban scenes, though this incurs proportional increases in storage and I/O overhead [41,49,51,53].

- Hybrid Consistency: Accuracy benefits significantly from pairing learned descriptors with SPC’s relational/ontological checks, which improve consistency on long-tail classes compared to pure learning approaches [39,44,45].

- Scalability: Runtime scales efficiently when SPC data models exploit LoD indexing and out-of-core access, with hot paths offloaded to compiled kernels or GPUs [46,52].

4.7. Outcomes

Across the Direct papers, several report measurable gains over baseline pipelines when SPC enrichment (semantics, relations, ontology checks) is applied—e.g., higher F1/OA/IoU in labeling tasks or lower RMSE in geometric evaluations (see Section 4.6 for task-specific metrics and examples) [39,43]. In parallel, deployable web viewers were demonstrated in application settings—archeology [53] and indoor mapping [51]—exposing semantic queries and multi-LoD navigation directly on SPCs, which signals movement from prototype workflows toward operational portals.

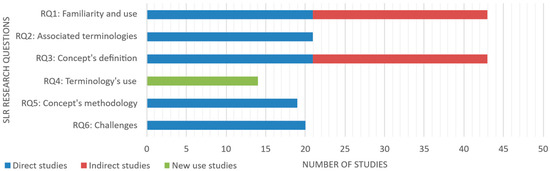

Given the heterogeneity of the 58-paper corpus and our six research questions (RQs), contributions are uneven (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Studies contributing to each RQ. Bars show the number of papers per category.