Abstract

The UK’s net-zero by 2050 commitment necessitates urgent housing sector decarbonisation, as residential buildings contribute approximately 17% of national emissions. Post-1950 construction prioritised speed over efficiency, creating energy-deficient housing stock that challenges climate objectives. Current retrofit policies focus primarily on technological solutions—insulation and heating upgrades—while neglecting broader sustainability considerations. This research advocates systematically integrating Circular Economy (CE) principles into residential retrofit practices. CE approaches emphasise material circularity, waste minimisation, adaptive design, and a lifecycle assessment, delivering superior environmental and economic outcomes compared to conventional methods. The investigation employs mixed-methods research combining a systematic literature analysis, policy review, stakeholder engagement, and a retrofit implementation evaluation across diverse UK contexts. Key barriers identified include regulatory constraints, workforce capability gaps, and supply chain fragmentation, alongside critical transition enablers. An evidence-based decision-making framework emerges from this analysis, aligning retrofit interventions with CE principles. This framework guides policymakers, industry professionals, and researchers in the development of strategies that simultaneously improve energy-efficiency, maximise material reuse, reduce embodied emissions, and enhance environmental and economic sustainability. The findings advance a holistic, systems-oriented approach, positioning housing as a pivotal catalyst in the UK’s transition toward a circular, low-carbon built environment, moving beyond isolated technological fixes toward a comprehensive sustainability transformation.

1. Introduction

The United Kingdom’s residential sector contributes significantly to national carbon emissions, accounting for approximately 17% of the total, primarily due to poorly insulated and outdated housing stock constructed during the post-war period [1]. These buildings often lack modern energy-efficient characteristics, explaining their excessive energy consumption and associated greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [2]. Retrofitting these structures to energy-efficient standards is imperative to meeting the UK’s net-zero targets by 2050 [3].

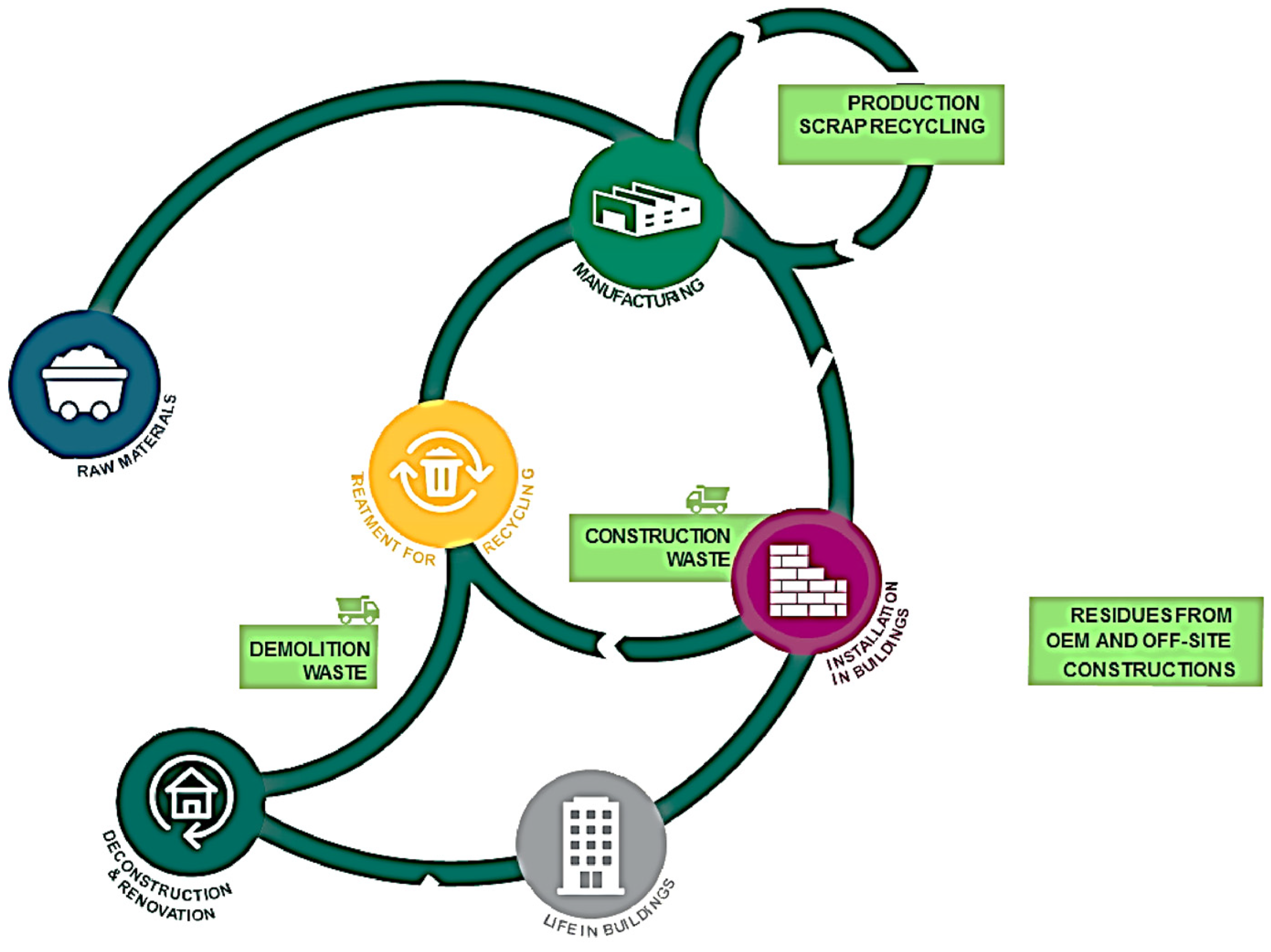

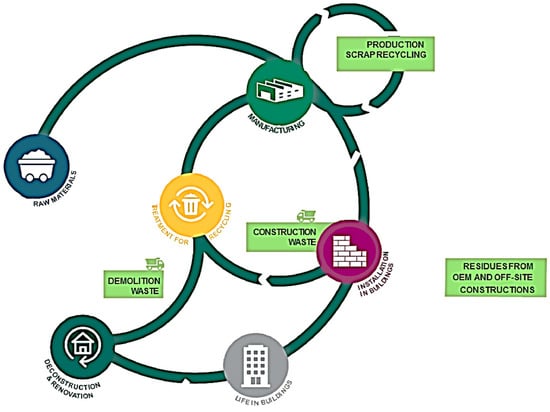

Traditional retrofitting strategies, of which one example is lifecycle thinking (LCT), have focused on enhancing thermal performance and reducing operational energy use [4]. While these measures are essential, they often overlook the full lifecycle impacts of materials and construction processes, including embodied carbon emissions and resource depletion [5]. According to the literature, adopting a lifecycle approach to retrofitting is becoming compelling, because circular economy (CE) attributes that promote material reuse (see Figure 1) extend building lifespans and minimise reliance on virgin resources [6]. Integrating CE principles into retrofitting practices not only decouples construction activities from raw material consumption intensity but also reduces the ecological footprint of the built environment, aligning environmental objectives with long-term economic benefits. When successfully implemented, this strategy has significant potential for enhancing the UK’s nationally determined contributions (NDCs) to global climate action [7].

Figure 1.

Circular economy recycling and reuse adapted from EURIMA 2025 [8].

This study aims to develop a comprehensive decision-making framework that integrates CE principles into energy-efficient retrofitting of post-1950 UK housing. Through synthesising the current literature, policy analyses, stakeholder insights, and technical assessments, the framework seeks to guide stakeholders in implementing sustainable and circular retrofitting.

2. Energy-Efficient Retrofitting in the UK

Advancements in energy retrofitting have been focused on improving thermal insulation, upgrading heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems, and installing renewable technologies such as solar panels [9].

However, the adaptation of energy retrofitting measures has not met expectations, perhaps due to high upfront costs, knowledge gaps among stakeholders, and fragmented supply chains [10]. It is believed that government initiatives such as the Green Homes Grant (GHG) and the Energy Company Obligation (ECO) have attempted to address these barriers but have faced implementation challenges, including administrative complexities and limited contractor engagement [11].

Moreover, energy retrofits often result in unintended consequences, such as reduced indoor air quality or the use of materials with a high level of embodied carbon [12]. A narrow focus on operational energy savings can miss opportunities for holistic sustainability improvements, highlighting the need for integrated approaches that consider the full lifecycle impacts of retrofitting interventions [13].

2.1. Circular Economy in the Built Environment

The concept of the circular economy has gained traction in the construction sector by promoting practices such as material reuse, design for disassembly (DfD), and waste minimisation [14]. In the context of housing retrofits, CE principles can complement energy-efficiency measures by ensuring that materials used have less embodied carbon and are part of a sustainable resource loop [2]. Strategies like adaptive reuse, closed-loop recycling, and the use of bio-based building materials can reduce the environmental footprint of retrofitting projects [6,7,9] (see Figure 1).

Despite the potential benefits, integrating CE principles into retrofitting remains underexplored, especially concerning existing UK housing [3]. Comprehensive frameworks that guide stakeholders in incorporating CE strategies into retrofit planning and execution are lacking, underscoring the need for research that bridges this gap [15].

2.2. Gaps in Existing Research

The integration of circular economy (CE) principles within the retrofitting sector represents a critical yet under-developed approach to addressing the environmental challenges posed by the built environment. While substantial research exists examining either retrofitting or circular economy in isolation, their intersection remains inadequately explored [16,17]. This study examines the significant knowledge gaps that impede the effective implementation of circular economy principles (CEPs) in retrofitting practices, with particular attention to post-1950 UK housing stock.

First, it explores the unclear and inconsistent definitions that surround the concept of the circular economy. The circular economy concept remains plagued by definitional inconsistencies when applied to retrofitting contexts. The construction sub-sector has adopted circular terminology without sufficient adaptation to the unique characteristics of building renovation and retrofitting [18]. Hence, there appears to be a need for some conceptual clarity to explain the concept of “circular economy washing,” where organisations adopt surface-level CE practices without making fundamental systemic changes [19]. This could particularly highlight the absence of standardised frameworks that differentiate between truly circular approaches and incremental improvements in waste management for retrofitting projects [20].

2.3. Technical Implementation Barriers

The technical feasibility of circular retrofitting faces substantial knowledge deficits [21]. However, there are emerging research outputs that argue that it can be incorporated into designs for disassembly from the start, as retrofit projects face the challenge of working with existing buildings that were not originally designed with circular principles in mind [22,23]. Significant gaps in understanding how to recover materials from existing buildings without reducing their technical properties and economic value exist [23]. Indeed, there is limited research on connection systems that would enable the non-destructive disassembly of retrofitted components for future reuse [24].

The interface between new and existing materials in circular retrofits presents another critical knowledge gap. Furthermore, research also argues that ‘the compatibility of recovered materials with modern building systems remains largely unexamined,’ particularly regarding long-term performance and stability [17]. This technical uncertainty contributes significantly to stakeholder reluctance to adopt circular approaches in retrofitting projects [25].

2.4. Economic and Market Constraints

The economic viability of circular retrofitting approaches remains insufficiently researched, and the absence of robust comprehensive cost–benefit analyses that consider the complete lifecycle impacts of circular retrofitting strategies is identified as a major knowledge gap [26]. Conventional economic assessments fail to capture the “externalised benefits” of circular approaches, including reduced resource depletion and waste management costs [27].

The market infrastructure to support circular retrofitting is similarly underdeveloped, and there are significant gaps in the understanding of how to establish reliable supply chains for secondary materials in retrofitting projects [28]. It is also argued that without established markets for recovered building components, circular retrofitting may still be economically unviable for most practitioners [29]. Despite these challenges, there has been limited research examining alternative business models specifically designed for circular retrofitting [29].

2.5. Policy and Regulatory Framework Deficiencies

Current building regulations and standards address operational energy-efficiency; there appears to be limited consideration of material circularity in retrofitting contexts [18]. Policies also cover operational carbon reductions, but without equivalent attention to embodied carbon and material flows, which hinder retrofitting [16]. This is further complicated by the persistent absence of circularity metrics within building assessment methods and certification systems relevant to retrofitting [27]. Scholars have also argued that policy approaches across different governance levels further complicate the implementation of circular retrofitting [30]. This problem is worsened by the lack of alignment between national sustainability goals, local planning policies, and building regulations, creating major barriers to comprehensive circular approaches in retrofitting [17]. To bridge these gaps, a prerequisite for developing effective policy instruments for sustainable retrofitting appears necessary.

2.6. Social and Behavioural Dimensions

Our review suggests that the social aspects of implementing CE in retrofitting appear to represent the most significant knowledge gap. Homeowner perceptions regarding reused materials in retrofit projects appear to be under-explored [28]. Although extensive research on consumer acceptance of energy-efficiency measures exists, similar research examining attitudes toward material circularity in home renovations is non-existent [31]. Additionally, the challenges posed by the gap in construction professionals’ skills regarding circular retrofitting techniques are real [22]. The required competencies for the successful implementation of circular approaches in retrofitting contrast with conventional renovation methods, yet training programmes and educational frameworks addressing these differences remain underdeveloped [18].

2.7. Integration with Energy-Efficiency Objectives

A critical knowledge gap exists in understanding the potential synergies and conflicts between material circularity and energy-efficiency in retrofitting projects. In practice, improving operational energy-efficiency often comes at the cost of material circularity [16]. Research assessing how to balance these potentially competing objectives is long overdue [16]. Though such trade-offs are often complex, the need for an effective framework to guide practitioners through these complexities cannot be overemphasised [20].

Furthermore, the significant knowledge gaps identified across conceptual, technical, economic, policy, and social dimensions impede the integration of circular economy principles into retrofitting practices. Addressing these gaps requires interdisciplinary research that bridges the theoretical and practical aspects of circular retrofitting, particularly in the challenging context of post-1950 UK housing stock [21]. As the construction sector faces increasing pressure to reduce both operational and embodied environmental impacts, developing robust frameworks for circular retrofitting represents an urgent research priority.

3. Methodology

This research employs an exploratory sequential mixed-methods design to develop a practical decision-making framework for integrating circular economy (CE) principles into the energy-efficient retrofitting of post-1950 UK housing. The methodology addresses the complex socio-technical challenges of sustainable retrofitting by systematically using qualitative insights to inform framework development [31,32]. This approach ensures the triangulation of data sources, producing robust and applicable findings [33,34,35]. Prioritising real-world relevance, the study’s structured, multi-phase approach moves beyond theoretical concepts to provide a tangible tool for tackling housing decarbonization, as highlighted below [36,37].

3.1. Research Design Approach: Three Interconnected Phases

This research employs a structured, three-phase approach to develop a practical decision-making framework for integrating circular economy (CE) principles into the energy-efficient retrofitting of post-1950 UK housing. This methodology is designed to systematically build knowledge, ensuring the final framework is both empirically rigorous and applicable to real-world challenges.

3.1.1. Phase 1: Foundation Building Through Document Analysis

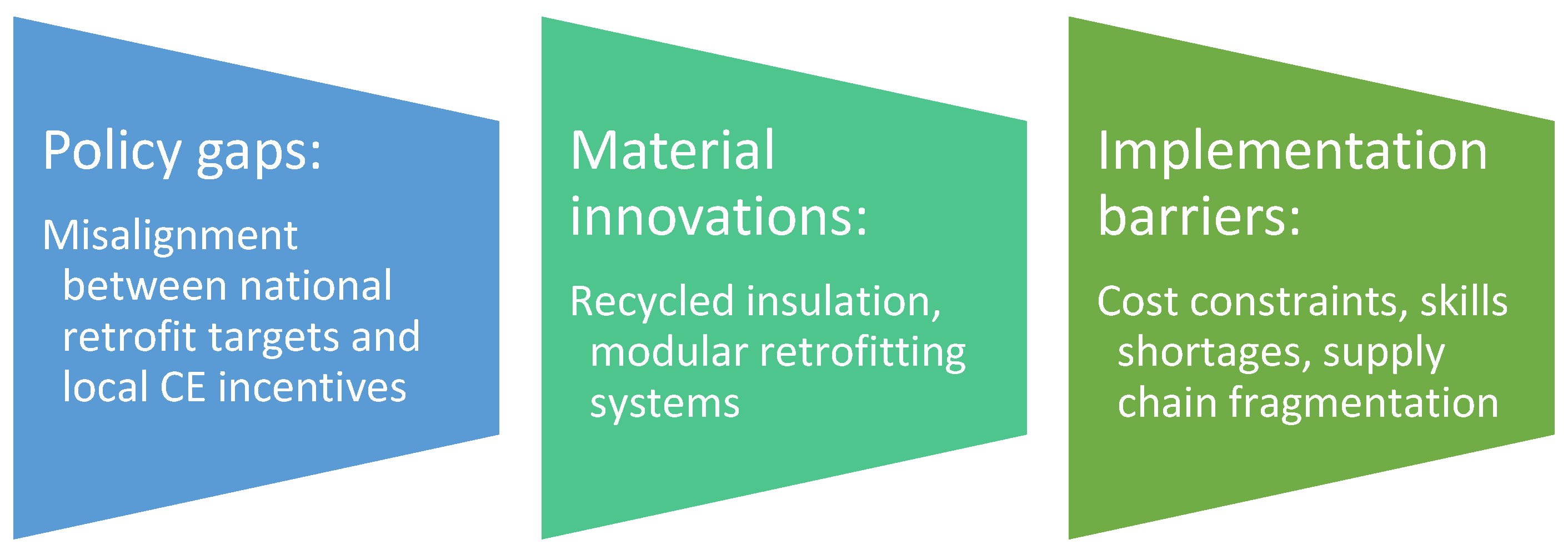

The first phase, Foundation Building Through Document Analysis, had the objective of establishing the current landscape of circular retrofit practices and identifying key knowledge gaps (see Figure 2). A systematic review of 102 documents published between 2014 and 2024 was conducted to achieve this goal. The reviewed materials included government and industry reports from organisations like the UK Green Building Council and BRE, as well as peer-reviewed academic publications on topics such as CE, construction, and energy-efficiency. Additionally, case study repositories, like “Retrofit for the Future” and “Energies UK”, were analysed. The selection of these documents was based on specific criteria: they had to focus on post-1950 UK housing retrofits, including CE principles such as material reuse and design for disassembly, and cover policy, technical, and socio-economic dimensions.

Figure 2.

Analysis Process: thematic coding using NVivo 14 identified three critical areas.

3.1.2. Phase 2: Stakeholder Insights Through Semi-Structured Interviews

The second phase of the research aimed to capture real-world experiences and practical challenges across the entire retrofit value chain. We conducted interviews with 27 participants, whose profiles were carefully selected to represent a diverse range of stakeholders. This included six policymakers, such as local authority sustainability officers; twelve industry practitioners, including architects, contractors, and material suppliers; and nine end-users, consisting of social housing tenants and private homeowners. Our sampling strategy was a combination of purposive selection to ensure a broad representation of all stakeholders and snowball sampling to identify niche experts, particularly within circular material startups. Each interview, lasting between 45 and 90 min, utilised a structured protocol that included a critical incident technique to extract specific retrofit experiences, scenario-based questions to explore successful and failed circular economy cases, and perception mapping to identify barriers across regulatory, economic, and cultural dimensions. All audio recordings were transcribed, anonymized, and then analysed using an inductive thematic analysis to identify recurring patterns. The findings were then cross-validated with the document analysis from Phase 1.

3.1.3. Phase 3: Framework Validation Through Expert Consensus

The objective of using expert consensus was to refine and validate the proposed framework through structured, skilful feedback. The thematic synthesis integrated the findings from Phases 1 and 2, which produced five core framework dimensions (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Core framework dimensions.

3.1.4. The Processes Applied

The final phase of the research employed a two-round Delphi process with 12 experts to validate and refine the proposed framework. The first round gathered open-ended feedback on the framework’s clarity and completeness. In the second round, quantitative validation was conducted using 5-point Likert scales to measure the framework’s feasibility, scalability, and policy alignment.

Established on the expert feedback, which yielded a mean validation score of 4.2 out of 5.0, several key refinements were made. The framework was enhanced to prioritise retrofit “quick wins” for immediate material reuse opportunities and a dedicated financing dimension was added, covering green mortgages and “pay-as-you-save” schemes. Additionally, the cost-sharing model specifications were enhanced to provide more clarity [38].

Quality Assurance and Limitations

The methodological strengths of this research include its use of a multi-stakeholder perspective, ensuring a balanced representation of all viewpoints. The systematic triangulation across document analysis, interviews, and expert validation significantly strengthened the findings. Furthermore, the iterative refinement process enhanced the robustness of the final framework.

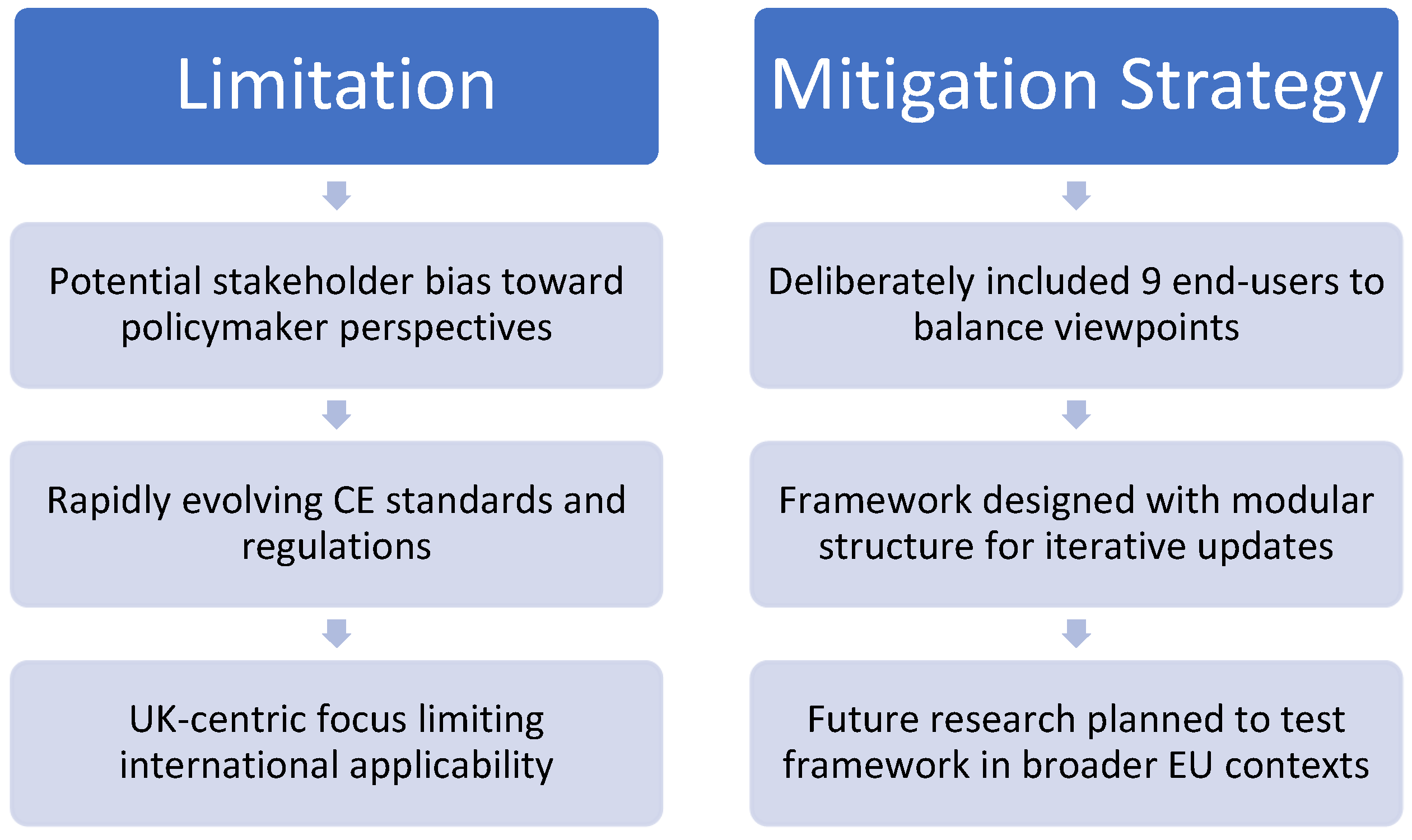

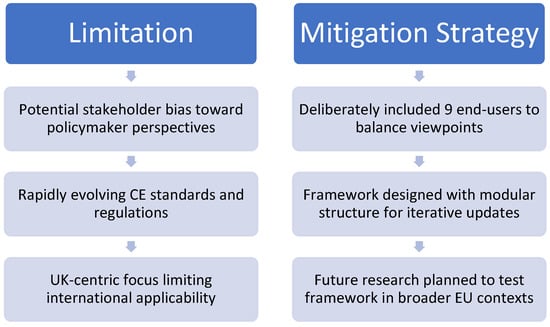

While rigorous, the study acknowledges certain limitations. A potential stakeholder bias toward policymaker perspectives was mitigated by deliberately including nine end-users to balance viewpoints. The challenge of rapidly evolving circular economy (CE) standards and regulations was addressed by designing the framework with a modular structure to allow for iterative updates. Lastly, while the research has a UK-centric focus, limiting its immediate international applicability, future research is planned to test the framework in broader EU contexts (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Acknowledged limitations and mitigation strategies.

Research Contribution and Next Steps

This methodology ensures both empirical rigour and practical relevance by grounding the circular retrofit framework in real-world constraints and opportunities. The combination of a systematic evidence review, stakeholder engagement, and expert validation positions the framework for immediate application across policy development, industry implementation, and community-led retrofit initiatives.

Future research priorities include pilot testing the framework in diverse retrofit contexts and developing quantitative impact assessment tools to measure circular economy outcomes in practice. However, there were significant findings, which will be discussed in the next session.

4. Findings and Discussion

The current state of UK retrofitting practice is still the development stage, and this could undermine the sector’s sustainability claims. While the industry congratulates itself on operational energy improvements, it systematically ignores the substantial environmental costs embedded within its material choices and construction processes [39]. This selective focus exposes a critical flaw in contemporary sustainability discourse: the privileging of measurable operational metrics over complex lifecycle impacts that resist easy quantification.

The division that is evident across the construction industry is not merely an organisational inconvenience but a structural impediment that perpetuates unsustainable practices [40]. The siloed nature of construction delivery creates institutional barriers that prevent the systemic thinking necessary for genuine sustainability transitions. More concerning is the regulatory vacuum surrounding circular economy principles [23], which suggests either policy failure or deliberate avoidance of the challenging trade-offs that comprehensive sustainability demands.

4.1. Stakeholder Perceptions: Promise Versus Practice

The apparent enthusiasm for material reuse and salvage operations among survey respondents warrants critical examination [41]. While respondents express belief in the potential for significant embodied energy reductions through material reuse, this optimism may reflect aspirational thinking rather than practical experience. The gap between stated support and actual implementation suggests that stakeholder attitudes, while positive, are insufficient to drive systemic change without addressing underlying structural constraints.

The emphasis on design for disassembly represents a more fundamental challenge to established construction practice [42,43]. The claim that modular approaches can achieve 40% waste reductions [44,45], while impressive, requires scrutiny regarding the methodological assumptions underlying such calculations. Furthermore, the retrofitting context presents unique constraints that may limit the applicability of design-for-disassembly principles developed for new construction. The existing building stock was not conceived with circularity in mind, and the technical feasibility of retrofitting for future disassembly remains theoretical.

4.2. Bio-Based Materials: Environmental Panacea or Performance Compromise?

The promotion of bio-based materials such as hempcrete and cross-laminated timber reflects a concerning tendency to seek technological solutions to systemic problems [45]. While these materials may offer carbon sequestration benefits, their thermal and structural performance characteristics relative to conventional alternatives require rigorous evaluation beyond environmental metrics. The assertion that bio-based materials can achieve “comparable thermal performance” [45] glosses over potential trade-offs in durability, maintenance requirements, and long-term performance stability.

More fundamentally, the focus on material substitution avoids the more challenging question of whether the scale and pace of retrofitting activity itself is sustainable. The lifecycle assessment methodologies promoted as decision-making tools [46] may provide analytical sophistication while obscuring the fundamental question of consumption levels and resource throughput.

4.3. Knowledge Deficits: Symptom or Cause?

The identification of widespread knowledge gaps among construction professionals regarding circular economy principles [47] raises questions about the readiness of the sector for the proposed transformation. However, characterising this as merely an educational deficit may misdiagnose the underlying problem. The limited adoption of circular practices may reflect rational responses to economic and regulatory incentives rather than simple ignorance.

The economic barriers identified—particularly the 15–30% cost premium for circular approaches [48]—represent fundamental market failures that educational interventions cannot address. The preference for predictable returns over uncertain environmental benefits reflects established financial logics that prioritise short-term performance over long-term sustainability. The assumption that better information will overcome these structural constraints appears naive.

4.4. Regulatory Framework: Policy Failure or Political Choice?

The critique of existing regulatory frameworks for failing to incentivise circular economy principles [49] assumes that such incentives are technically feasible and politically palatable. However, the complexity of measuring and validating circular performance metrics may make regulatory intervention more challenging than acknowledged. The absence of standards for reclaimed materials may reflect legitimate concerns about performance reliability and liability rather than regulatory oversight.

The call for “policy integration across building, energy, and waste sectors” [39,49] underestimates the political and administrative challenges of coordinating across established institutional boundaries. The fragmentation of governance responsibilities may represent deliberate specialisation rather than policy failure, and integration efforts may create new inefficiencies and accountability gaps.

4.5. Supply Chain Limitations: Market Reality or Transitional Challenge?

The identification of supply chain constraints as barriers to circular retrofitting requires careful interpretation [50]. The characterisation of supply networks as “fragmented and unreliable” [51] may reflect the early stage of market development rather than inherent limitations. However, the regional variations in material availability suggest that circular retrofitting may be economically viable only in specific geographic contexts, raising questions about the scalability and equity of such approaches.

The emphasis on “hyper-local material sourcing networks” [16,52] may romanticise local production while ignoring the economies of scale and quality assurance mechanisms that centralised supply chains provide. The trade-off between local sourcing and material quality, cost, and availability requires more sophisticated analysis than the framework acknowledges.

4.6. The Proposed Framework: Ambition Versus Feasibility

The comprehensive framework proposed for integrating circular economy principles into retrofitting practice demonstrates admirable ambition but questionable feasibility. The multi-stakeholder collaboration model, while theoretically sound, assumes a level of coordination and shared commitment that may not exist in practice. The claim that such approaches facilitated “40% higher adoption rates” [51] requires scrutiny regarding the sustainability and scalability of these interventions.

The emphasis on continuous monitoring and evaluation [28,53,54], while methodologically rigorous, may impose administrative burdens [42,43] that small-scale practitioners cannot accommodate. The framework’s complexity may inadvertently favour large organisations with greater administrative capacity [39,40], potentially excluding the diverse range of actors necessary for widespread adoption [23,42]. Furthermore, the quality of standard assessment that “directly affects retrofitting effectiveness” [23,41,55] raises questions about the capacity [44,45] and competence [46,47] of existing assessment protocols to manage the complexity of circular interventions.

4.7. Economic Viability: Optimism or Evidence?

The assertion of economic viability based on “7-to-10-year positive rates of return” [48,49,52] requires critical examination of the assumptions underlying such calculations. The reliance on full lifecycle costing methodologies [49,50] may incorporate speculative benefits [16,51,55] that cannot be realised in practice. Furthermore, the timeframe for return on investment may exceed the planning horizons of many stakeholders, particularly in the residential sector where ownership patterns and financing mechanisms may not align with long-term payback periods.

The emphasis on performance-based retrofitting standards [56] assumes that measurement protocols can adequately capture the complex interactions between energy-efficiency, material circularity, and long-term building performance [52]. The absence of established benchmarks for circular performance metrics may render such measurements meaningless for decision-making purposes [16,53]. A comprehensive framework tailored to identify barriers in this study has been developed to enhance energy-efficient retrofitting and maximise sustainability outcomes.

5. Circular Economy Integration Framework for UK Retrofitting Practices

A comprehensive five-pillar approach to integrate circular economy principles into energy-efficient retrofitting of post-1950 UK housing stock was derived from the empirical analysis from this study. The framework responds to the identified barriers, and it is expected to enhance the sustainability attributes of Nigeria’s built environment industry.

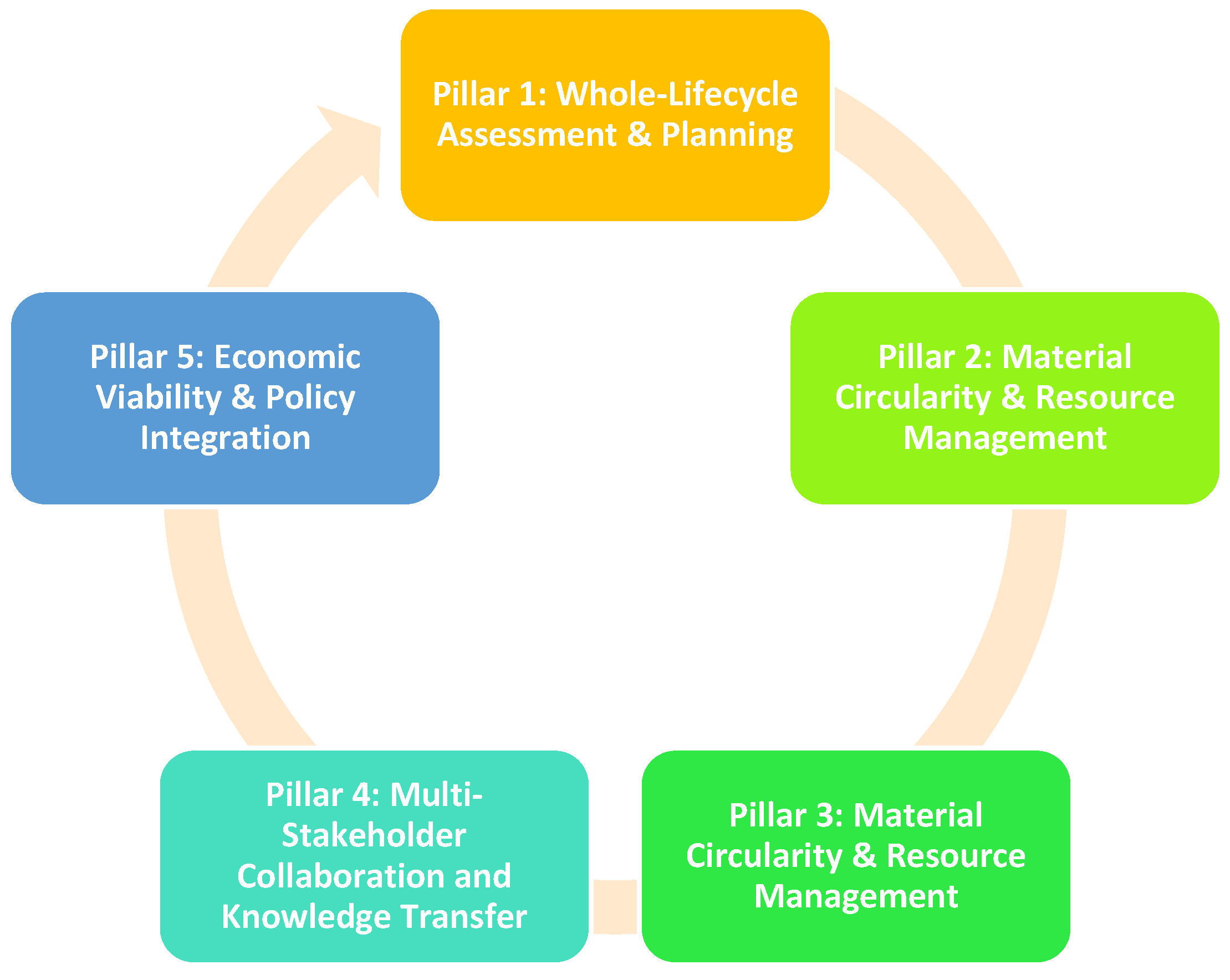

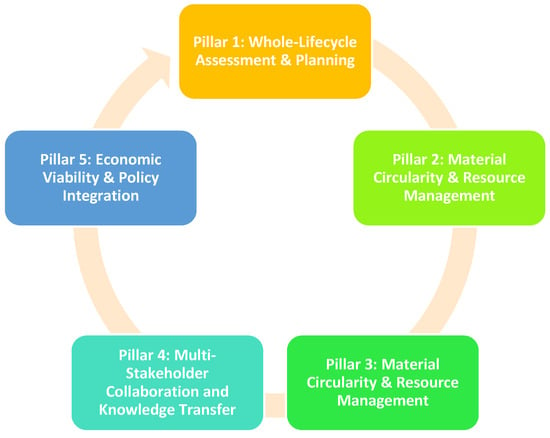

5.1. Pillars of Circular Economy Integration Framework for UK Retrofitting Practices

5.1.1. Pillar 1: Whole-Lifecycle Assessment and Planning

This pillar shifts the focus of retrofitting from a narrow view of operational energy to a comprehensive, whole-lifecycle approach. The core principle is to move beyond simply reducing energy bills and instead consider the full environmental impact of a building, from the materials used to its potential for future reuse (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Pillars of circular economy integration framework for UK retrofitting practices.

The key actions to achieve this include conducting a pre-retrofit assessment to evaluate the quality and circular potential of the existing housing stock. This is followed by a mandatory embodied carbon analysis of all materials, as well as the integration of lifecycle assessment (LCA) tools to guide material selection. Finally, every project should include future adaptability planning to ensure the building can meet changing needs without requiring extensive future renovations.

Success in this pillar is measured by clear performance indicators. These include achieving a minimum 30–45% reduction in embodied carbon, creating a material passport for all building components, and establishing an adaptability score to quantify a project’s long-term flexibility.

5.1.2. Pillar 2: Material Circularity and Resource Management

This pillar is all about prioritising material reuse, recovery, and local sourcing. The core principle is to shift away from a linear, “take–make–dispose” model by giving materials a new life within the building sector (see Figure 4).

To achieve this, several key actions must be taken. The first is systematic material salvage and reuse, which involves the careful recovery of valuable components like bricks, timber, and metals from demolition or renovation sites. Furthermore, establishing hyper-local material networks is crucial for reducing the environmental impact of transportation. Projects should also strategically integrate bio-based materials such as hempcrete and cross-laminated timber, which can actively sequester carbon. Finally, these actions collectively contribute to a broader goal of waste minimization by diverting materials from landfills.

The success of these efforts can be measured by specific performance indicators. These include a target for the percentage of reclaimed materials used in a project (with a minimum of 30% recommended), setting local sourcing radius targets (ideally under 50 km), and monitoring waste diversion rates from landfills.

5.1.3. Pillar 3: Material Circularity and Resource Management

This pillar focuses on the core principle of enabling component-level circularity through reversible construction. Moving away from permanent, destructive building methods, it ensures that materials and components can be easily recovered and reused at the end of a building’s life or during renovations (see Figure 4).

The key actions to achieve this include the widespread implementation of modular design, which uses standardised connections to allow for the easy removal of components. This is supported by non-destructive dismantling systems that enable materials to be recovered without damage. Furthermore, the adoption of component standardisation across the industry would make elements interchangeable, creating a robust market for recovered materials. Finally, buildings must be designed for maintenance optimisation, with accessible repairs and upgrades in mind.

The performance indicators for this pillar include targets for renovation waste reduction, with a goal of at least 40% [44,45]. Other key metrics are the component recovery rates at end-of-life and a maintenance accessibility score, which quantifies how easily a building’s parts can be repaired or replaced.

5.1.4. Pillar 4: Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration and Knowledge Transfer

This pillar’s core principle is to address knowledge gaps and foster innovation through coordinated, cross-industry engagement. The success of circular economic principles in retrofitting relies on breaking down traditional silos and ensuring that information flows freely among all parties (see Figure 4).

To achieve this, several key actions are necessary. First, collaborative partnerships must be established to integrate all stakeholders—from homeowners and local authorities to architects, contractors, and environmental organisations. Concurrently, professional development is critical, requiring targeted training programmes to equip construction professionals with the skills needed for circular retrofitting. These efforts should be supported by the creation of knowledge-sharing platforms for industry-wide information exchange. Finally, active supply chain integration is essential to coordinate across the traditionally fragmented sectors of the industry.

The effectiveness of this collaboration can be measured by several performance indicators, including professional competency certification rates, stakeholder engagement participation levels, and metrics that gauge the effectiveness of knowledge transfer.

5.1.5. Pillar 5: Economic Viability and Policy Integration

This pillar’s core principle is to create the enabling conditions necessary for the widespread adoption of circular retrofitting. While the environmental benefits are clear, success hinges on making these practices economically viable and integrating them into a supportive regulatory framework (see Figure 4).

To achieve this, a number of key actions are essential. First, new financial mechanisms must be developed to address the initial 15–30% cost premium associated with circular materials and methods. This includes creating funding models that make these projects accessible. At the same time, regulatory reform is crucial to embed circular economic principles directly into building standards and regulations. To ensure accountability, clear performance standards must be established to measure a project’s circular performance, which also facilitates market recognition. Finally, policy coordination across the building, energy, and waste sectors is needed to remove systemic barriers and promote a unified approach.

The performance indicators for this pillar are focused on tangible results. These include achieving an economic payback period of 7–10 years, monitoring regulatory compliance rates, and tracking the overall market uptake of these new practices.

The framework required an effective pathway because of the systemic change needed, which requires coordinated development across technical, economic, regulatory, and social dimensions. Attempting immediate full-scale implementation may fail due to insufficient supporting infrastructure, unresolved technical challenges, and inadequate stakeholder preparedness. For this reason, a phased approach is recommended to ensure that each phase builds the necessary foundations for the next, creating momentum while managing risks and maximising the chances of successful transformation to circular retrofitting practices.

Three implementation pathways have been suggested to manage the complexity of integrating circular economic principles into UK retrofitting practices. The research reveals significant knowledge gaps [47], fragmented industry structures [40], and substantial economic barriers [48] that cannot be overcome simultaneously. In this regard, a structured, phased approach rather than immediate wholesale transformation is recommended.

5.2. Implementation Pathways

5.2.1. Phase 1: Foundation Building (Years 1–2)

The foundation years are critical for establishing the regulatory frameworks and professional competencies necessary to address the identified knowledge deficits among building professionals regarding circular economic principles (CEPS) [47]. Without this foundational infrastructure, the fragmented implementation and institutional barriers that currently characterise the construction industry will persist, preventing the systemic change required for effective circular retrofitting [40]. At this phase, regulatory frameworks and standards to guide the framework are developed and operationalised. Accompanying this is the need for professional training programmes, material passport systems to facilitate an effective supply chain, and pilot demonstration projects.

5.2.2. Phase 2: Market Development (Years 3–5)

Market development is critical as it transforms fragmented and unreliable supply networks into coordinated systems capable of supporting widespread circular retrofitting [51]. This phase establishes the economic viability necessary to overcome cost barriers by enabling economies of scale and supply chain efficiencies [48]. This concisely explains why Phase 2 is essential—it addresses both the supply chain fragmentation issue identified in the research and the economic barriers that prevent adoption. This is the phase in which it is possible to scale material supply networks, implement financial incentive schemes, expand multi-stakeholder collaborations, and monitor and evaluate trials.

5.2.3. Phase 3: Mainstream Integration (Years 6–10)

Mainstream integration represents the critical transition from experimental adoption to industry-wide transformation, where circular retrofitting becomes standard practice rather than an exceptional intervention. This phase enables the realisation of full economic benefits through established 7–10-year return cycles and systematic policy coordination across building, energy, and waste sectors [39,52]. This highlights how the final phase transforms circular economy principles from pilot projects to embedded industry norms, while achieving the economic viability and policy integration necessary for sustained implementation. This is the phase in which widespread industry adoption occurs, continuous performance monitoring takes place [28], system optimisation and refinement are implemented, and policies are reviewed and enhanced.

This framework provides a structured approach to overcoming identified barriers while capitalising on opportunities for circular economic integration in UK retrofitting practices, ensuring both environmental effectiveness and economic viability.

5.3. Contributions to Circular Economy and Retrofitting Knowledge

This research addresses a critical knowledge gap at the intersection of circular economy theory and retrofitting practice, providing the first comprehensive framework specifically designed for integrating circular economy principles into the energy-efficient retrofitting of post-1950 UK housing stock. Moving beyond theoretical discourse, this study delivers practical solutions to overcome the systemic barriers that have prevented meaningful circular economy adoption in the UK retrofitting sector. This study also makes an original theoretical contribution by developing the first integrated conceptual model that bridges circular economy principles with building retrofitting practice. Unlike the existing literature, which treats these domains separately, this study demonstrates how circular thinking can be systematically embedded within energy-efficiency objectives without compromising performance outcomes.

Also, this research fundamentally reconceptualises retrofitting from a linear, consumption-based activity to a regenerative, resource-positive process. This represents a significant departure from conventional retrofitting discourse, which has remained anchored in operational energy-efficiency metrics while ignoring embodied carbon and material flows. The introduction of a methodological approach that places diverse stakeholder perspectives at the centre of framework development is a novelty, as it moves beyond expert-driven models to incorporate the ground-level implementation realities of homeowners, contractors, and policymakers. This provides the first comprehensive analysis of barriers to circular retrofitting across technical, economic, regulatory, and social dimensions simultaneously. Previous research has examined these barriers in isolation; this research reveals their interconnected nature and develops integrated solutions.

Empirically, this study has also contributed to UK retrofitting knowledge in quantifying performance gains. This research provides the first empirical evidence that modular retrofitting approaches can achieve up to a 40% waste reduction compared to conventional methods in UK housing contexts. It demonstrates that systematic material reuse can deliver 30–45% embodied carbon reductions—quantified impacts previously unavailable in the literature. The study also provides the first context-specific implementation pathways tailored to post-1950 UK housing stock, addressing the unique technical and regulatory challenges of this building typology that represents the majority of UK housing requiring retrofitting interventions. Unlike existing theoretical frameworks, this study provides the first operationalised guidance for implementing a design for disassembly principles in retrofitting contexts, including specific technical solutions for component recovery and reuse. This is reflected in the supply chain integration model—the first attempt at a systematic analysis of how to develop local material sourcing networks for circular retrofitting, providing practical guidance for overcoming the fragmented supply chains that currently limit material recovery and reuse.

This study also directly contributes to UK net-zero objectives by demonstrating how circular retrofitting can address both operational and embodied carbon emissions—a dual contribution that conventional retrofitting approaches cannot achieve. The framework provides specific pathways for achieving the UK’s building decarbonisation targets while simultaneously advancing circular economy objectives. This is also unique in its specific focus on post-1950 housing, which represents approximately 80% of the current UK housing stock requiring a retrofitting intervention. This focus addresses a critical knowledge gap, as most existing research has concentrated on older heritage buildings or new construction.

This research advances circular economy theory by demonstrating how circular principles can be integrated into existing systems without requiring wholesale replacement of infrastructure or practices. This contributes to emerging scholarship on transition pathways and system-level change management. The framework developed provides a foundation for investigating how circular retrofitting approaches can be scaled beyond the UK context and adapted to different building typologies, climate conditions, and regulatory environments.

Thus, this research contributes to both circular economy theory and retrofitting practice by providing the first comprehensive, evidence-based framework for integrating circular principles into UK housing retrofitting. The study advances knowledge by moving beyond theoretical aspirations to practical implementation, demonstrating that circular retrofitting is not only environmentally necessary but also economically viable and socially beneficial when approached systematically. Most significantly, this research demonstrates that the UK’s existing building stock can be transformed from a sustainability liability into a resource asset, creating a built environment that is regenerative by design and resilient in performance. This transformation requires coordinated action across the technical, economic, regulatory, and social dimensions—precisely what the proposed framework enables.

6. Conclusions

This research establishes that integrating circular economy principles into UK retrofitting practices represents a transformative pathway for achieving sustainable decarbonisation of the built environment. The comprehensive framework developed addresses critical knowledge gaps by bridging circular economy theory with practical retrofitting implementation, specifically targeting post-1950 housing stock, which comprises the majority of UK buildings requiring intervention.

The study’s five-pillar approach demonstrates that circular retrofitting can deliver substantial environmental benefits, including a 40% waste reduction and 30–45% embodied carbon savings, while maintaining economic viability through 7–10-year return cycles. The phased implementation pathway recognises the complexity of systemic change, providing structured progression from foundation-building through market development to mainstream integration.

Key contributions include the first comprehensive barrier analysis across the technical, economic, regulatory, and social dimensions, alongside quantified performance metrics that validate circular retrofitting effectiveness. The multi-stakeholder collaboration model addresses fragmented industry structures while the regulatory integration framework harmonises policy across the building, energy, and waste sectors.

This research fundamentally reconceptualises retrofitting from a linear, consumption-based activity to a regenerative, resource-positive process. By transforming existing building stock from a sustainability liability to a resource asset, the framework enables the UK to advance both net-zero objectives and circular economy transition simultaneously, creating built environments that are regenerative by design and resilient in performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.G.; Methodology, L.G. and D.D.O.; Software, L.G.; Formal analysis, D.D.O.; Investigation, L.G.; Data curation, D.D.O.; Writing—original draft, L.G.; Writing—review & editing, L.G., O.J.E., J.Z. and D.D.O.; Visualization, D.D.O.; Supervision, L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Wolverhampton, United Kingdom.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the fact that the data is part of an ongoing research study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CE | Circular Economy |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| LCT | Life Cycle Thinking |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning |

| NDCs | Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) |

| ECO | Energy Company Obligation |

| DfD | Design for Disassembly Deconstruction |

| ER | Energy Retrofit/Energy Efficiency Retrofit |

| ECO | Green Homes Grant |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| GHG | Green Homes Grant |

| UK | United Kingdom (used in context of case studies, policies, retrofitting) |

| CEPs | Circular Economy Principles (sometimes used in discussion of policies) |

References

- Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS). Net Zero Strategy: Build Back Greener; UK Government, Department for Energy Security and Net Zero: London, UK, 2022; pp. 79, 136.

- Ionescu, C.; Baracu, T.; Serban, A.; Vlad, G.E.; Necula, H. The historical evolution of the energy efficient buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 49, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabid, J.; Bennadji, A.; Seddiki, M. A review on the energy retrofit policies and improvements of the UK existing buildings, challenges and benefits. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 159, 112161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Xing, K.; Pullen, S.; Zuo, J. A life cycle thinking framework to mitigate the environmental impact of building materials. One Earth 2020, 3, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, C.C.; Vaz, I.C.M.; Ghisi, E. Retrofit strategies to improve energy efficiency in buildings: An integrative review. Energy Build. 2024, 321, 114624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA). Resources and Waste Strategy Annual Progress Report; DEFRA: London, UK, 2023.

- Zhang, L.; Zhou, K.; Yang, S.; Shao, Z. Decarbonising residential building energy towards achieving the intended nationally determined contribution at subnational level under uncertainties. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 272, 122760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EURIMA. Circular Economy. 2025. Available online: https://www.eurima.org/circular-economy (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Aljashaami, B.A.; Mohammed, H.J.; Hasan, A.N.; Al-Juboori, R.A.; Hasan, H.A.; Al-Farhany, K. Recent improvements to heating, ventilation, and cooling technologies for buildings based on renewable energy to achieve zero-energy buildings: A systematic review. Results Eng. 2024, 23, 102769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Circular Economy in Cities; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS). Heat and Buildings Strategy; HM Government: London, UK, 2023.

- Collins, M.; Dempsey, S. Residential energy efficiency retrofits: Potential unintended consequences. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2018, 62, 2010–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PAS 2035:2019; Specification for Retrofitting Dwellings. Updated 2023; British Standards Institution (BSI): London, UK, 2023.

- Charef, R.; Lu, W.; Hall, D. The transition to the circular economy of the construction industry: Insights into sustainable approaches to improve the understanding. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 364, 132421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewunruen, S.; Chen, C.; Li, D.; Wang, Y. Comparisons of stakeholders’ influences, inter-relationships, and obstacles for circular economy implementation on existing building sectors. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 61863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomponi, F.; Moncaster, A. Circular economy for the built environment: A research framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.; Adams, K.; Giesekam, J.; Tingley, D.D.; Pomponi, F. Barriers and drivers in a circular economy: The case of the built environment. Procedia CIRP 2019, 80, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benachio, G.L.F.; Freitas, M.C.D.; Tavares, S.F. Circular economy in the construction industry: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 121046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, N.; Corvellec, H. Waste policies gone soft: An analysis of European and Swedish waste prevention plans. Waste Manag. 2018, 77, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, G. Circular economy strategies for adaptive reuse of cultural heritage buildings to reduce environmental impacts. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 152, 104507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fořt, J.; Černý, R. Limited interdisciplinary knowledge transfer as a missing link for sustainable building retrofits in the residential sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 343, 131079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Densley Tingley, D.; Davison, B. Design for deconstruction and material reuse. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Energy 2011, 164, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanbi, L.A.; Oyedele, L.O.; Akinade, O.O.; Ajayi, A.O.; Davila Delgado, M.; Bilal, M.; Bello, S.A. Salvaging building materials in a circular economy: A BIM-based whole-life performance estimator. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 129, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansom, M.; Avery, N. Briefing: Reuse and recycling rates of UK steel demolition arisings. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Eng. Sustain. 2014, 167, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlJaber, A.; Martinez-Vazquez, P.; Baniotopoulos, C. Barriers and Enablers to the adoption of Circular Economy concept in the building sector: A Systematic literature review. Buildings 2023, 13, 2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, K.T.; Osmani, M.; Thorpe, T.; Thornback, J. Circular economy in construction: Current awareness, challenges and enablers. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Waste Resour. Manag. 2017, 170, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahpour, A. Prioritising barriers to adopt circular economy in construction and demolition waste management. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 134, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munaro, M.R.; Tavares, S.F.; Bragança, L. Towards circular and more sustainable buildings: A systematic literature review on the circular economy in the built environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 121134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ness, D.A.; Xing, K. Toward a resource-efficient built environment: A literature review and conceptual model. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 572–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trencher, G.; Healy, N.; Hasegawa, K.; Coffman, D.M. Innovative policy practices to advance building energy efficiency and retrofitting: Approaches, impacts and challenges in ten C40 cities. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 66, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.; Crane, L.; Chryssochoidis, G. The conditions of normal domestic life help explain homeowners’ decisions to renovate. Tyndall Cent. Clim. Change Res. 2018, 8, 371–413. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, G.A. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, A. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approach, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan, J.C. The critical incident technique. Psychol. Bull. 1954, 51, 327–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, L.D.; Borgen, W.A.; Amundson, N.E.; Maglio, A.S.T. Fifty years of the critical incident technique: 1954–2004 and beyond. Qual. Res. 2005, 5, 475–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Densley Tingley, D.; Cooper, S.; Cullen, J. Understanding and overcoming the barriers to structural steel reuse, a UK perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 148, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyedele, L.O.; Ajayi, S.O.; Kadiri, K.O. Use of recycled products in UK construction industry: An empirical investigation into critical impediments and strategies for improvement. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 93, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, S.O.; Oyedele, L.O.; Akinade, O.O.; Bilal, M.; Alaka, H.A.; Owolabi, H.A.; Kadiri, K.O. Reducing waste to landfill: A need for cultural change in the UK construction industry. J. Build. Eng. 2016, 5, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, S.O.; Oyedele, L.O.; Akinade, O.O.; Bilal, M.; Owolabi, H.A.; Alaka, H.A.; Kadiri, K.O. Optimising material procurement for construction waste minimization: An exploration of success factors. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2017, 11, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgolewski, M. Designing with reused building components: Some challenges. Build. Res. Inf. 2008, 36, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, S.O.; Oyedele, L.O.; Bilal, M.; Akinade, O.O.; Alaka, H.A.; Owolabi, H.A. Critical management practices influencing on-site waste minimization in construction projects. Waste Manag. 2017, 59, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yussif, M.; Taiwo, R.; Shakor, P.; Han, T.; Mohandes, S.R.; Antwi-Afari, M.F.; Qazi, K.; Singh, A.K.; Christo, M.S.; Shah, M.A. A comprehensive literature review on risk identification and assessment in green building construction projects. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2025, 29, 101089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askar, R.; Bragança, L.; Gervásio, H. Adaptability of Buildings: A Critical Review on the Concept Evolution. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conejos, S.; Langston, C.; Smith, J. Designing for better building adaptability: A comparison of adaptSTAR and ARP models. Habitat Int. 2014, 41, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anarene, C.B.; Saha, S.; Davies, P.; Kamrul, M.D. Decision Support System for Sustainable Retrofitting of Existing Commercial Office Buildings. Int. J. Sci. Res. Manag. 2024, 12, 7191–7212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, D.A.; Sherif, A.; El-Haggar, S.M. Environmental management systems’ awareness: An investigation of top 50 contractors in Egypt. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 18, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlmann, F.; Roehrich, J.K.; Grosvold, J. Sustainable supply chain management and partner engagement to manage climate change information. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 1632–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leising, E.; Quist, J.; Bocken, N. Circular economy in the building sector: Three cases and a collaboration tool. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 976–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, M.; Tucker, M.; Riley, M.; Longden, J. Towards sustainable construction: Promotion and best practices. Constr. Innov. 2009, 9, 201–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtain, R. An energy balance and greenhouse gas profile for county Wexford, Ireland in 2006. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 3773–3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, T.U.; Inalli, M. Impacts of some building passive design parameters on heating demand for a cold region. Build. Environ. 2006, 41, 1779–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, R.; Howden-Chapman, P.; Viggers, H.; O’Dea, D.; Kennedy, M. Retrofitting houses with insulation: A cost–benefit analysis of a randomised community trial. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2009, 63, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. Circular cities. Urban Stud. 2019, 56, 2746–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, X.; Lenihan, H.; O’Regan, B. A model for assessing the economic viability of construction and demolition waste recycling—The case of Ireland. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2006, 46, 302–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.