1. Introduction

The process of urbanization poses significant challenges to the environment, biodiversity, and human health. One of the prominent challenges is the urban heat island (UHI) effect, a phenomenon where cities experience higher temperatures than their surrounding rural areas [

1]. This effect is driven by multiple factors, including the continued expansion of impervious surfaces, the loss of green and blue spaces, high population density, and heat generated from industrial and transportation activities [

2]. Urban parks, as vital components of urban green space (UGS) systems, play a crucial role in mitigating heat stress and promoting public perceived health. Consequently, UGS in public areas has become a key research focus for addressing urban challenges and achieving sustainable urban development [

3]. It is therefore essential to investigate how to design these spaces to meet public needs for health and thermal comfort, thereby providing more agreeable landscape environments [

4,

5].

Existing literature has extensively examined the role of landscapes in climate regulation and thermal comfort [

6,

7]. For instance, Skelhorn et al. [

8] used the urban climate model ENVI-met (version 3.1 Beta V, revision date: 4th October 2010) to investigate the cooling effects of various landscapes in urban centers, finding that grasslands and mature trees were most effective at reducing surface temperatures. Similarly, Majid et al. [

9] demonstrated that landscapes significantly mitigate the urban heat island effect, with tree clusters having the most pronounced impact. A synthesis of previous research confirms that the spatial configuration of landscapes—such as green coverage, shade structures, and water distribution—significantly influences pedestrian thermal comfort and physiological and psychological health [

10]. Over the past decade, the importance of spatial configuration, encompassing both landscape composition (the type and amount of land cover) and spatial arrangement, has gained increasing recognition for mitigating urban heat, particularly in urban parks [

11,

12,

13]. The influence of spatial configuration on ecosystem services depends on its propagation and the extent of its impact on the surrounding environment [

2], making these services highly sensitive to external characteristics. In terms of actual cooling effects, factors such as building height, form, and nearby blue-green spaces all influence one another, and the mechanisms governing their interactions are complex [

2]. Concurrently, a growing body of research demonstrates that specific spatial features in urban parks contribute to resident well-being and that well-designed urban green spaces can improve mental health through various pathways [

14].

A user’s thermal state is a critical factor in assessing how well an environment meets human needs [

15]. Depending on their thermal state, individuals may adopt different thermal adaptive behaviors (TAB) [

16]. Consequently, pedestrians in urban parks exhibit varying behavioral intentions and destination choices. Destination loyalty, which reflects a resident’s willingness to revisit a place and the frequency of their visits, encompasses both attitudinal and behavioral dimensions [

17]. Although numerous studies demonstrate the independent impact of green spaces on public perceived health, the potential interactions among mediating variables have been less explored. Notably, the roles of destination loyalty and thermal comfort in influencing public perceived health have been largely overlooked [

5,

16]. Reviews indicate a growing body of experimental studies reporting that short-term exposure to green environments, such as parks, urban woodlands, and forests, can significantly improve mood and attention and facilitate recovery from psychological stress [

14]. This evidence confirms the important role of short-term exposure to green spaces in public perceived health [

14]. As visiting a green space is a form of pro-environmental behavior, different landscape configurations are likely to elicit varying levels of destination loyalty [

18].

The Perception–Intention–Action (PIA) framework is a comprehensive model that empirically examines public transit use in daily travel by integrating objective features with individuals’ subjective evaluations of the built environment, lifestyle, and travel [

19]. The PIA model accounts for contributions from both the built environment and socio-psychological factors, incorporating an extended version of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) to model the relationship between attitudes and behavior [

20]. This model is built on earlier travel behavior adaptation models, such as the open-system model developed by Fried, Havens, and Thall (FHT), which is based on an individual’s adaptive responses to imbalances in person-environment fit [

21,

22]. Like the FHT model, the PIA framework emphasizes the role of social and psychological factors in the relationship between the built environment and travel behavior. It is an empirically tested framework for understanding the linkages between perception, intention, and action [

19,

21]. Informed by the PIA framework, this study develops a Space–Perception–Behavior (SPB) theoretical framework. The SPB framework is designed to guide the creation of comfortable landscapes in urban parks that meet pedestrians’ health needs. It investigates the connection to public perceived health through the lenses of landscape spatial configuration, thermal comfort, and destination loyalty.

Previous research has established that the physical environment—such as the coverage of blue-green spaces and vegetation configuration—significantly influences microclimate regulation and public perceived health [

23,

24]. For example, vegetation cover is negatively correlated with land surface temperature; specifically, in large cities with a subtropical monsoon climate, a 10% increase in vegetation can reduce daytime surface temperatures by 1.2–2.5 °C [

23,

25]. Furthermore, urban spatial form, including building layout and street canyon design, affects human thermal comfort by altering wind flow and intensifying or mitigating the urban heat island effect [

26]. Concurrently, a robust body of literature attests to the positive impacts of urban green space exposure on self-reported mental well-being and perceived restoration [

14,

27]. However, most existing studies focus on objective physical metrics, such as temperature and humidity, or on general assessments of environmental preference and health outcomes [

28]. A significant gap remains in understanding the sequential psychological and behavioral process: how subjective perceptions—such as thermal comfort and the attractiveness of a landscape’s spatial configuration—influence behavioral decisions, including destination loyalty, and thereby ultimately impact public perceived health. Specifically, an integrated framework that links spatial perception, thermal-affective response (comfort), behavioral intention (loyalty), and perceived health outcomes under heat stress is lacking. To address this gap, this study examines the interrelationships between landscape spatial configuration, thermal comfort, destination loyalty, and public perceived health. We developed a dedicated scale to investigate the mediating and moderating interactions among these four constructs [

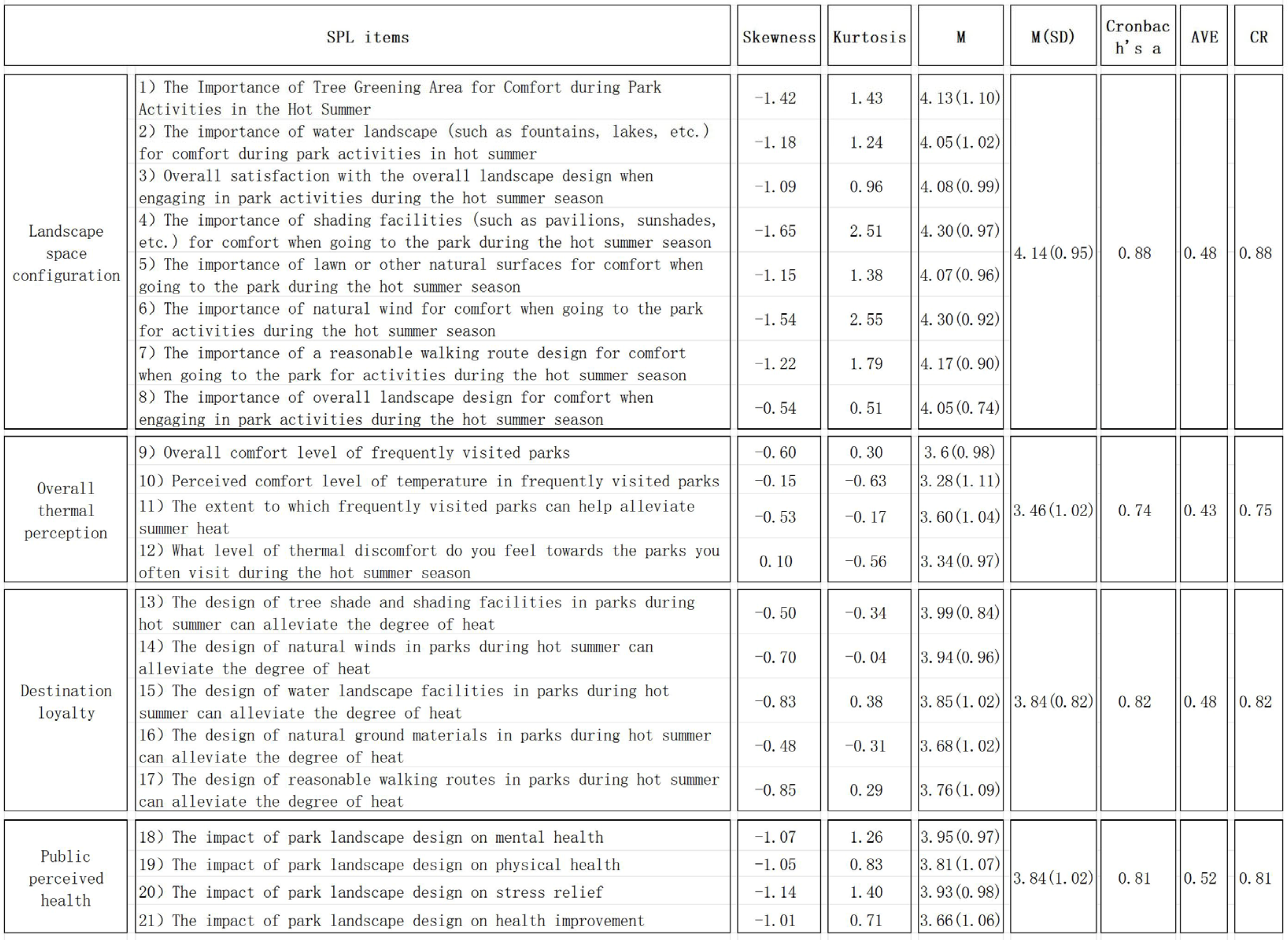

14]. Methodologically, we first employed Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to determine the number of underlying factors. After establishing the factor structure, we formalized the SPB theoretical framework. Subsequently, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was used to validate the item structure and test the framework’s construct validity [

19,

29]. Nevertheless, the complex relationships among landscape features, thermal comfort, destination loyalty, and public perceived health—particularly from a spatial perception perspective—are not yet fully understood. This study investigates these mechanisms by combining questionnaire surveys with Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to analyze how different landscape configurations and destination loyalty impact pedestrian thermal comfort and public perceived health in urban parks. Although the cooling effects of landscape design are well documented, the pathway from individual perception to behavioral outcomes (e.g., destination loyalty) and, ultimately, to health remains unclear.

Building upon the Perception–Intention–Action (PIA) framework, which links perception, psychological intention, and action, this study develops a Space–Perception–Behavior (SPB) theoretical framework. The SPB framework contextualizes PIA within the realm of thermal environment and park use: ‘Spatial Perception’ corresponds to the perceptual input; ‘Thermal Comfort’ and ‘Destination Loyalty’ together represent the critical psychological and behavioral intentions; and ‘Perceived Health’ is the targeted behavioral and welfare outcome. This integration offers a novel, interdisciplinary perspective focused on subjective experience. The SPB framework is specifically applied to explore the mediating and moderating relationships between landscape spatial configuration, thermal comfort, destination loyalty, and public perceived health. This research provides a scientific basis for climate-resilient urban park design and opens a new avenue for promoting public perceived health through targeted landscape interventions. Future studies could integrate multi-scale environmental data with behavioral analysis to more comprehensively reveal the dynamic relationships between landscape spatial configuration and public perceived health.

2. Theoretical Framework

Cooling landscape structures, commonly categorized as blue and green spaces, are relevant to all urban environments [

1]. The ecosystem services provided by these blue-green patches are influenced by two key dimensions: their composition and their spatial configuration [

19]. Composition refers to the types, quantities, and proportions of vegetation and water bodies. It is a critical factor driving the heterogeneous cooling effects of blue-green spaces, as it governs processes such as transpiration, shading, and surface radiation modification [

24,

30,

31]. Furthermore, the spatial patterns and configuration of a park’s landscape are significantly correlated with its cooling island effect [

32]. Optimizing this internal landscape arrangement is therefore a crucial strategy for enhancing cooling intensity [

33,

34,

35]. In practice, the diversity of land cover creates considerable complexity [

36]. Most urban parks are composed of core elements, including water features, walkways, recreational areas, vegetation, and various ground surfaces [

3,

37]. For this study, we define the variable “landscape spatial configuration” as the specific combination and arrangement of these constituent elements.

Thermal comfort is a critical factor influencing public perceived health during hot summer conditions. It is defined as “a psychological state that expresses satisfaction with the thermal environment” [

38] and serves as a key measure for assessing how well an environment meets human needs [

15]. When pedestrians experience stimuli from both the landscape and thermal conditions, it significantly shapes their perception of the surroundings [

28]. Research indicates that thermal comfort involves a complex interaction with other sensory and psychological adaptation mechanisms [

39].

Behavioral intention is a key psychological driver that leads pedestrians to interact with their environment in various ways to achieve a desired state of comfort [

40], a process that subsequently influences their destination loyalty. Therefore, this study collects data on pedestrian destination loyalty across different landscape configurations to systematically examine its relationship with thermal comfort and public perceived health.

The relationship between public perceived health and the environment is central to global sustainable development. As vital public spaces for daily activity, urban parks directly impact public perceived health through the quality of their landscapes and thermal environments, which shape pedestrians’ thermal comfort. Studies indicate that the thermal comfort provided by urban parks influences health by modulating outdoor activity patterns and physiological stress responses [

41]. Psychologically, thermal stress can exacerbate anxiety and depression. Conversely, well-designed landscape elements—such as vegetation, water bodies, and strategic building layouts—can create a more suitable microclimate. For instance, a park with ample shade can improve public perceived health by reducing sympathetic nervous system arousal [

42]. Therefore, this study constructs a framework model that traces the pathway from landscape design to health outcomes. This SPB theoretical framework, illustrated in

Figure 1, aims to provide a theoretical foundation and practical insights for healthy urban planning and improved public perceived health.

5. Conclusions

A key finding is the non-significant direct path from thermal comfort to perceived health (H5 rejected). This suggests that merely feeling thermally comfortable in a park does not, by itself, translate directly into stronger health perceptions. Instead, comfort operates primarily by enhancing destination loyalty—the willingness to revisit and recommend the park. This enhanced loyalty, fostered by a comfortable environment, then becomes the active mechanism through which health benefits (e.g., physical activity, stress reduction accrued through repeated visits) are realized. This underscores the importance of designing parks that are not only comfortable but also memorable and engaging enough to promote sustained visitation.

This study investigated the relationships among landscape spatial configuration, thermal comfort, destination loyalty, and public perceived health among pedestrians in urban parks during summer heat. The findings provide valuable insights for incorporating health-oriented landscape design considerations into urban park planning.

The findings demonstrate the validity of the SPB theoretical framework, which links landscape spatial configuration, thermal comfort, destination loyalty, and public perceived health. Analysis of the seven hypotheses revealed significant direct effects of landscape configuration on thermal comfort, public perceived health, and destination loyalty, with destination loyalty partially mediating the relationship between landscape configuration and public perceived health. Consequently, designers should prioritize integrating tree canopies with water features to enhance thermal comfort and destination loyalty, thereby maximizing health benefits. Additionally, creating diverse recreational nodes can extend park usage duration during high-temperature periods.

The analysis confirmed a significant direct effect of thermal comfort on destination loyalty. However, its direct effect on public perceived health was not significant (β = 0.067, p > 0.05). This lack of a direct link may stem from questionnaire-based perceptions, detached from on-site experience, and may fail to capture the full potential benefits of environmental comfort. Crucially, destination loyalty fully mediated the effect of thermal comfort on public perceived health (indirect effect β = 0.201, p < 0.05). This indicates that the primary value of improving thermal comfort lies in enhancing a location’s appeal, which, in turn, yields health benefits through repeated visits and activities such as walking and socializing. This finding underscores the need for designers to integrate “behavioral incentives” into heat-resilient landscape strategies, for instance, by creating connected shaded pathways to encourage prolonged stays.

Research on environmental thermal comfort spans multiple disciplines. However, most existing studies rely on collecting physical data and conducting environmental simulations to examine impacts on public perceived health [

72,

73], often overlooking pedestrians’ psychological perceptions as a precursor to such data collection. This study addresses this gap by analyzing factors from the pedestrian’s perspective. Through an examination of the psychological perception of landscape spaces, it identifies thermal comfort and destination loyalty as key factors and explores their relationship with public perceived health. This research is the first to connect these four factors, confirming both the direct and indirect influences of landscape spatial configuration, thermal comfort, and destination loyalty on public perceived health. It provides a theoretical framework grounded in pedestrian psychological perception that precedes physical data collection and simulation, offering valuable insights for subsequent research on physical factors and the design of urban parks.