Abstract

Digital leadership has emerged as a critical determinant of organizational success in an era characterized by rapid technological advancement, yet the field suffers from significant theoretical fragmentation and lacks a systematic integration of its evolving knowledge base, presenting substantial challenges for both practitioners and scholars seeking to advance theoretical understanding. This study aims to provide a more comprehensive perspective on the evolution and future research directions of digital leadership. A science mapping-based review is conducted to systematically examine and visualize 960 rigorously selected papers from the Web of Science (WOS), with no time constraints, covering all relevant publications from 1991 to 2024. The methods employed include regional co-occurrence, document co-citation, keywords clustering, and keywords burst to uncover the underlying structure and development of the field. The findings of this study reveal the development of foundational research in digital leadership, demonstrating the integration of methodologies and theories from other disciplines. Furthermore, the study identifies three research trends: green sustainable development, human-centered leadership and cross-cultural leadership. The contribution of this study is the construction of a knowledge map of digital leadership, providing a comprehensive understanding of digital leadership. To further illustrate the application of this map, the construction industry is used as a case study.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of digital technologies such as artificial intelligence, big data, cloud computing, and the Internet of Things, industries across the globe are undergoing profound digital transformations [1,2]. This trend presents unprecedented challenges and opportunities for leaders, driving fundamental changes in leadership practices and making digital leadership a critical research domain [3,4]. The rapidly evolving digital environment requires leaders to possess not only technological literacy but also strategic foresight, enabling them to effectively leverage technology to build a competitive advantage for their organizations [5,6,7]. At the same time, an increasing number of organizations have come to realize that relying solely on technology is not sufficient to ensure competitiveness in the digital age; rather, the core factor lies in effective digital leadership [8,9,10].

The theoretical significance of digital leadership has been extensively examined across multiple academic disciplines, revealing its multifaceted impact on contemporary organizations. From a strategic management perspective, digital leadership represents a core capability in building the dynamic capabilities required for digital transformation, serving as a key organizational asset that enables organizations to sense, seize, and reconfigure digital opportunities in turbulent environments [11]. Research in organizational behavior demonstrates that digital leadership fundamentally reshapes power structures, communication patterns, and decision-making processes within organizations [12,13]. Furthermore, the field of information systems has established digital leadership as a critical mediating mechanism between technological infrastructure and organizational value creation [14,15]. Additionally, the practical significance of digital leadership is evident on multiple levels: At the organizational level, digital leadership has been shown to be a key driver of innovation, digital transformation, and organizational agility [8,16,17]. At the team level, it profoundly changes communication patterns, performance management, and trust rebuilding within teams [18,19,20]. At the individual level, leaders’ thinking styles, digital literacy, and adaptive behaviors in a technology-driven environment are significantly influenced by digital leadership [21,22,23].

However, research in the field of digital leadership still faces several challenges because different disciplines have distinct definitions, and there is a lack of an interdisciplinary integrated perspective which hinders both the theoretical advancement and practical application of the field [4,23,24]. To address these research gaps, this study employs a science mapping-based review, analyzing all relevant publications without time constraints, including those published from 1991 to 2024, to offer a comprehensive and holistic understanding of the evolution and knowledge base and explore emerging themes and research frontiers of digital leadership. Science mapping offers significant methodological advantages over traditional narrative reviews. As a statistical and quantitative analysis tool, it can systematically and reproducibly visualize large volumes of the literature, providing quantitative bibliometric data that clearly reveal theoretical frameworks and developmental trajectories, thereby overcoming the limitations of subjectivity and researcher bias often present in traditional reviews [25,26]. Co-citation analysis, a powerful tool within this analytical method, reveals the potential theoretical connections between documents by analyzing the frequency with which foundational works are co-cited across different disciplines. Co-citation analysis identifies interconnections between the literature across various disciplines, methods, and theoretical approaches, offering valuable insights for further theoretical integration and helping alleviate the problem of theoretical fragmentation within academic fields, ultimately enhancing the understanding of specific research topics and emerging trends [26,27]. To achieve this aim, this study has two research objectives (ROs) as follows:

RO1: To visualize the intellectual structure of digital leadership field by synthesis of related research and identify its underlying theories, basic themes and knowledge evolution;

RO2: To construct the future research framework for digital leadership by exploring trends and future research areas that will shape the future of digital leadership.

To address these two objectives, this study contributes to complementing the existing literature reviews that may lack comprehensiveness or fail to emphasize an overarching meta-analysis [28,29]. Furthermore, based on the analysis, this paper constructs a knowledge map of digital leadership and directs attention to key research areas. In terms of practice, this study provides practical guidance for the implementation of digital leadership, using the construction industry as a case example.

2. Digital Leadership: Conceptualization and Theoretical Foundations

2.1. Evolution and Definition of Digital Leadership

Academic research on digital leadership can be traced back to the 1990s, when scholars such as Hambley, O’Neill and Kline [20], Avolio et al. [30], Karahanna and Watson [31] and colleagues introduced concepts such as “E-leadership”, “Virtual Leadership”, and “Informational Leadership.” These studies pioneered the exploration of how electronic communication technologies transformed traditional leadership styles.

As digital technologies have become more widespread and complex, various disciplines have engaged in research on digital leadership, and the concept has continuously evolved and matured. For example, in the field of strategic management, El Sawy et al. [32] defined digital leadership as “doing the right things for the strategic success of digitalization for the enterprise and its business ecosystem,” highlighting its core role in strategic decision-making and vision setting. Within the educational domain, digital leadership is conceptualized as “the strategic use of digital resources and technology to drive improvement, innovation, and transformation in education,” emphasizing the role of technology in fostering educational change [33]. In management studies, Kane, Phillips, Copulsky and Andrus [21] defined it as “the ability of leaders to drive organizational success through technology, data, and innovation during digital transformation,” emphasizing its integrated qualities of technological expertise, strategic insight, and change management.

Through a cross-disciplinary synthesis of digital leadership definitions, the core commonalities can be revealed. All existing definitions emphasize the element of technology leverage, which refers to the ability of leaders to enhance organizational efficiency and performance through the effective utilization of digital tools and platforms. Furthermore, digital leadership is generally seen as a key capability for driving organizational digital transformation. However, a certain degree of conceptual fragmentation still persists in current definitions: these definitions range from individual leader competencies [34] to organizational capabilities [16,32], and even extend to ecosystem-level coordination [18]. Definitions at the individual level tend to focus more on personal attributes such as digital literacy, organizational-level definitions emphasize systemic capabilities like cultivating digital culture and coordinating digital infrastructure, while the ecosystem-level perspectives further expand the concept of digital leadership to include inter-organizational boundary-spanning and coordination. The theoretical relationships and boundary conditions connecting these levels have not been adequately articulated, leading to uncertainty in the application of the concept.

Nevertheless, these different perspectives are not contradictory but complementary. However, the lack of a clear integration framework still limits the further development of the theory and its practical application. Therefore, to better define the current conceptualization of digital leadership, this study synthesizes these perspectives and defines digital leadership as a multi-level process through which leaders leverage digital technologies to influence individual competencies, build digital teams, and thereby drive organizational transformation and create value.

2.2. Theoretical Foundation and Limitations of Digital Leadership

Early studies primarily focused on the impact of technological change on digital leadership and the effects of digital leadership on organizational and industry transformations [34,35]. These studies were mostly based on classic theoretical foundations, such as transformational leadership [36], and did not form entirely new theoretical frameworks. As technology has evolved and its definition has expanded, scholars have increasingly recognized that digital leadership extends beyond merely utilizing technologies for management; it assumes a strategic function in enabling organizations to build competitiveness in the digital age [9,23,37]. Therefore, its scope has transcended a mere adaptation of traditional leadership theories and incorporated new frameworks such as the dynamic capabilities theory and resource-based theory, viewing digital leadership as an organizational resource for gaining competitive advantage in response to change [3,17]. Traditional leadership’s ability to sense opportunities relies on the leader’s personal cognition and experiential pattern recognition, which are often constrained by cognitive limitations and information processing speed [38]. In contrast, digital leadership leverages advanced digital technologies, such as big data analytics, to more efficiently identify potential opportunities and threats. Additionally, leaders use digital tools to accelerate decision-making and enhance organizational agility, thereby facilitating the seizing process [3]. Furthermore, leaders reshape organizational structures, business models, and asset coordination through the use of digital technologies, thereby effectively implementing organizational capabilities and strategies to adapt continuously and maintain competitiveness in turbulent environments [3,11,39].

The existing literature is fragmented in terms of theoretical frameworks, with research scattered across multiple disciplines, including school education, government governance and business management [32,33,40]. As a result, the theoretical foundation of digital leadership remains unclear and inconsistent [22]. To address this gap, numerous review studies on digital leadership have emerged in recent years; however, these studies have certain limitations. For instance, Espina-Romero, Noroño Sánchez, Rojas-Cangahuala, Palacios Garay, Parra and Rio Corredoira [4] propose future directions but fail to construct a systematic research framework; Karakose, Kocabas, Yirci, Papadakis, Ozdemir and Demirkol [24] focus on concept and evolution analysis, while Tigre, Curado and Henriques [23] and Banks et al. [41] primarily discuss the similarities and differences between digital leadership and traditional leadership.

Overall, the existing research offers a limited perspective and has not comprehensively captured the knowledge base and development trends of digital leadership. The lack of effective integration in current research hinders a holistic understanding of the field and restricts its further advancement [27,33]. To fill this gap, this study provides a comprehensive knowledge foundation through a review of knowledge mapping and offers directions for future research.

3. Research Methods

3.1. Research Design

According to Dang et al. [42], the structure of the scientific field can be identified through its research activities serving two key functions in rapidly evolving domains: Firstly, the foundational knowledge structure and theoretical frameworks that support both current and future development can be captured, providing the necessary context for understanding emerging phenomena [43]. Secondly, it helps identify the core themes and emerging topics of the research field, thereby assisting in predicting the evolution patterns and trajectories of future development directions [44]. A science mapping-based review provides a systematic foundation and forward-looking predictions for exploring this rapidly changing field [27,45].

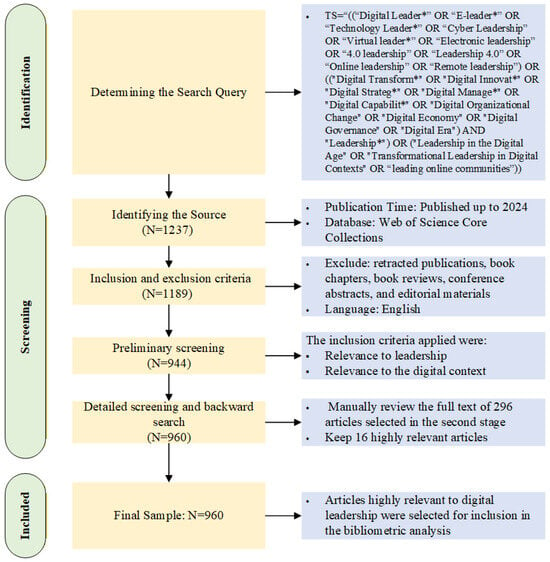

Therefore, this study adopts a systematic three-phase research design aimed at comprehensively examining the field of digital leadership research. First, the data collection and screening process was rigorously conducted following the PRISMA guidelines, which include four steps: identification, screening, assessment, and inclusion [46]. This framework provides a detailed procedure for the screening and integration of the literature, enhancing the credibility of the literature collection process [47]. Second, the data analysis phase employs methods such as regional co-occurrence analysis, document co-citation analysis, keyword clustering analysis, and keyword burst analysis to gain a deeper understanding of the core areas and development trends in digital leadership research. Finally, based on the results of these analyses, this study integrates findings across multiple dimensions to construct a comprehensive understanding of the knowledge structure of the field and proposes potential directions for future research.

3.2. Data Collection

3.2.1. Determining the Search Query

The selection of keywords is a crucial aspect of this study, and the process underwent a rigorous multi-stage screening procedure. Initially, we reviewed seminal works and recent review articles in the field of digital leadership to ensure that the core terms and developmental trajectory of the field were comprehensively covered. For example, early terms such as “E-leadership” [30], “Virtual Leadership” [19,48], “Technology Leadership” [49], and “Electronic Leadership” [50] were identified. As information technology advanced and digital transformation accelerated, “Digital Leadership” [21] and “Industry 4.0 Leadership” [51] have gradually gained widespread usage. In addition, recent studies have primarily focused on the influence of leadership on strategic management within organizations. Therefore, this study draws on the definition of digital leadership proposed by Bartsch, Weber, Büttgen and Huber [34] and incorporates keyword combinations such as “Digital Transformation*”, “Digital Innovation*”, “Digital Strategy*”, and “Leadership”. Furthermore, emerging contextual phrases and inter-disciplinary perspectives, such as “Leadership in the Digital Age” [52], “Transformational Leadership in Digital Contexts” [53], and “Leadership in Online Communities” [54] have also been included to expand the scope of the research.

Additionally, the search terms used in previous bibliometric review papers were considered and compared. The final search query was designed to comprehensively cover all relevant fields related to “digital leadership,” as follows: ((“Digital Leader*” OR “E-leader*” OR “Technology Leader*” OR “Cyber Leadership” OR “Virtual leader*” OR “Electronic leadership” OR “4.0 leadership” OR “Leadership 4.0” OR “Online leadership” OR “Remote leadership”) OR ((“Digital Transform*” OR “Digital Innovat*” OR “Digital Strateg*” OR “Digital Manage*” OR “Digital Capabilit*” OR “Digital Organizational Change” OR “Digital Economy” OR “Digital Governance” OR “Digital Era”) AND “Leadership*”) OR (“Leadership in the Digital Age” OR “Transformational Leadership in Digital Contexts” OR “leading online communities”)). This search query ensures that the literature related to digital leadership across various domains, applications, and contexts is thoroughly captured.

3.2.2. Identifying the Database

The bibliographic data were extracted from the core collection of the Web of Science (WoS) database (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA), covering all relevant publications from 1991 to 2024, with no time restrictions applied. WoS is widely recognized for its rich academic resources and high-quality, peer-reviewed journals. The decision to rely on WoS was made to obtain high-quality and diverse academic sources, providing a strong data foundation for this study and ensuring consistency and comparability in the research [55]. This approach avoids potential data duplication and discrepancies that may arise from using multiple databases, simplifying the analysis process, and reducing potential errors. Moreover, the use of a single database of WoS has been validated and proven reliable by many scholars, such as Jiang et al. [27] and Farooq [56]. A total of 1237 relevant articles were retrieved from the database through the search formula.

3.2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To ensure the credibility, quality, and analytical consistency of the retrieved data, the following exclusion criteria were applied, along with their specific justifications: (1) retraction of publications was excluded due to issues of scientific validity; (2) book chapters, conference abstracts, news item, letter and editorial materials were excluded as they lack complete citation data indexing in the WoS database, which would compromise the integrity of co-citation network analysis, a core method requirement for scientometric mapping [56]; (3) book reviews were excluded as they do not represent original research contributions; (4) only English-language publications were retained to ensure linguistic consistency and comparability in keyword extraction and semantic analysis [57]. Following these criteria, a total of 1189 papers were screened in the preliminary search process, as outlined below.

3.2.4. Preliminary Screening

A more rigorous review procedure was used after the initial filtering to make sure the chosen papers were extremely relevant to the “digital leadership” theme, with a focus on leadership that successfully supports digital transformation. All identified papers’ titles, abstracts, and keywords were carefully examined. The inclusion criteria applied were as follows: (1) relevance to leadership: papers that focused solely on digital technologies, rather than leadership, were excluded; (2) Relevance to the digital context: research addressing leadership in traditional management or non-digital industries was excluded. This thorough screening process resulted in the retention of 944 papers for further analysis.

3.2.5. Detailed Screening and Backward Search

A manual review was conducted on the 248 full-text papers excluded during the subsequent screening stage, using the same filtering criteria as in the initial phase. Of these, 16 papers were determined to be relevant and were re-added to the sample list. Consequently, a total of 960 papers were ultimately retained for analysis.

The bibliographic records of the selected papers were exported from WoS into VOSviewer (version 1.6.20, Centre for Science and Technology Studies, Leiden, The Netherlands) and CiteSpace (version 6.1.6 Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, USA) for analysis. Each record included information on authors, affiliations, countries or regions, titles, abstract keywords, publication year, source journal, and references. Figure 1 depicts the specific workflow for quantifying data sources using the PRISMA. Additionally, Table S1: The PRISMA checklist facilitated the scientific preparation and reporting of this study.

Figure 1.

The PRISMA workflow showing the data acquisition process.

3.3. Analytical Method

The science mapping-based review was performed using methods such as regional co-occurrence analysis [58], keyword clustering [59,60], keyword bursts [61], and document co-citation analysis [62,63]. The threshold settings for these methods were derived from the existing literature, with continuous experimentation and adjustment to generate visually intuitive maps [64]. The specific settings are as follows:

To analyze the regions of the collaboration network, a threshold of k ≥ 25 papers published was set, helping to identify countries/regions with substantial research contributions within the field. Additionally, it filters out small-scale papers that could introduce noise into the network, thereby improving the representativeness and accuracy of the collaboration network [65].

Following the established standards in bibliometric research, such as Jiang, Zhao, Wang and Herbert [27], and Vogel [66], this study set a minimum citation threshold of 15 for co-citation network, ultimately including 100 papers for analysis. This threshold strikes a balance between the comprehensiveness of the literature and the precision of the analysis.

The keywords clustering analysis employed the Latent Semantic Indexing [67] algorithm, with a threshold set at k = 25. The LSI algorithm in CiteSpace was chosen because of its outstanding ability to handle polysemy commonly encountered in interdisciplinary fields, improving the accuracy of keyword clustering [68].

The keyword burst analysis was performed using Kleinberg’s Burst Detection Algorithm in CiteSpace. This algorithm identifies sudden changes in citation frequency over time, marking keywords that experience a burst in activity. The parameters have been validated in multiple bibliometric studies and are specifically designed to identify sustained shifts in attention [69].

A dual-software method was adopted to explore the field with both depth and comprehensiveness [70,71]. VOSviewer has been selected as it could generate more distinct and interpretable documents co-citation analysis, addressing limitations of clustering algorithms in CiteSpace. Concurrently, CiteSpace has been used for its robust capabilities in keyword dynamics. VOSviewer and CiteSpace were complementary to each other and helped explore the field with more precision and comprehensiveness.

4. Results

4.1. Quantity of Publications

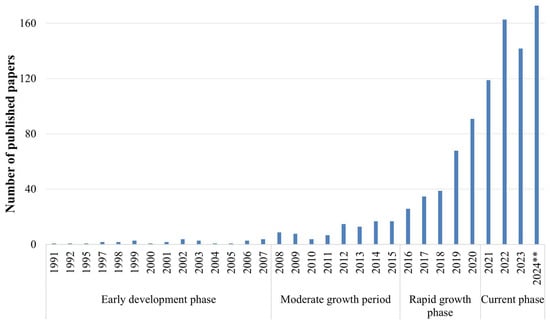

Figure 2 depicts the evolving trend of publications on digital leadership, revealing distinct phases in the development of research within this domain. During the early development phase (1991–2007), the volume of publications remained relatively low, indicating limited academic attention. The moderate growth period (2008–2015) was marked by a steady rise in research output, with the average annual publication volume increasing significantly, reaching 15 papers in 2012 and 17 in 2015, representing an average annual growth rate of approximately 15%. The rapid growth phase (2016–2020) had a sharp increase in publications, with output rising from 26 papers in 2016 to a peak of 91 papers in 2020, representing a 250% increase over this five-year period. In the current phase (2021–2024), publication volumes have stabilized, consistently exceeding 100 papers annually. Specifically, 119 papers were published in 2021.

Figure 2.

Research publications published between 2012 and 2024. (Note: ** represents partial-year data, as data collection was completed in 2024; the count for this year is subject to increase as additional publications are indexed.)

4.2. Regional Co-Occurrence Analysis

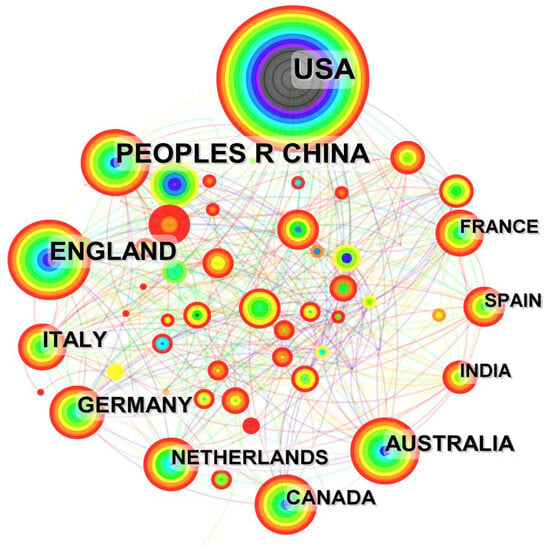

The visualization generated using CiteSpace illustrates the co-occurrence network of regions contributing to digital leadership research. Node size represents the volume of publications, with larger nodes signifying regions with higher research output. The temporal evolution is visualized through a color gradient ranging from black (1991) to red (2024). Centrality, ranging from 0 to 1, reflects its effectiveness in connecting disparate parts of the collaboration network, with values exceeding 0.1 considered high [72]. High centrality identifies a node as a critical bridge and key hub for research collaboration.

The nodes in Figure 3 represent countries/regions with at least 25 publications in digital leadership. Table 1 lists the top 20 countries/regions with the highest publication volumes.

Figure 3.

Collaborative co-occurrence map of digital leadership. (Note: The color gradient of the nodes indicates the temporal evolution of research activity, transitioning from cool colors (black) representing earlier periods (1991) to warm colors (red) representing more recent periods (2024).)

Table 1.

The top 20 regions in terms of publication volume.

The United States leads the field with 237 publications and a centrality score of 0.42, underscoring its dominant position, and acts as a primary bridge for international research partnerships. China ranks second, contributing 169 publications with a centrality score of 0.27, highlighting its significant influence in the global research network. Other countries, including Italy, Australia, and Germany, demonstrate publication volumes but lower centrality scores. This suggests that these countries contribute significantly to research output, but their roles in supporting global research connectivity are limited.

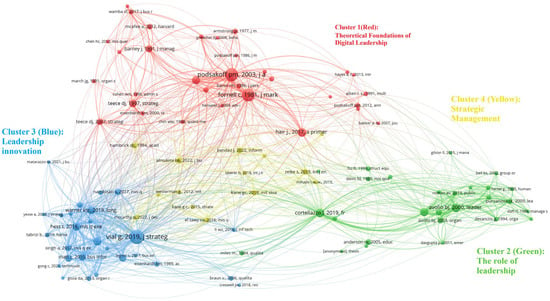

4.3. Document Co-Citation Analysis: Knowledge Base

The co-citation network was visualized using VOSviewer’s clustering algorithm to identify groups of related documents (Figure 4). In the visualization, the size of each node reflects the total number of citations received by the document. In contrast, the distance between nodes indicates the strength of their co-citation relationship. Documents within the same cluster have a high degree of co-citation, suggesting that they address related topics or employ similar methodologies.

Figure 4.

Co-citation network of secondary documents in four clusters.

The co-citation network constructed from these references revealed four distinct clusters, each representing a unique thematic or methodological focus within the field:

Co-Citation Cluster 1 (Red): Theoretical Foundations of Digital Leadership

The integration of strategic management theories with advanced quantitative research techniques is the main focus of this field of study. Teece et al. [73] and Teece [38] proposed a dynamic capabilities framework. Furthermore, there is also the resource conservation theory proposed by Barney [74].

In addition, sophisticated quantitative research methods such as Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) and Structural Equation Modeling [75] provide exacting tools for developing and testing complex digital leadership models. Hair et al. [76], Hair Jr et al. [77], Henseler et al. [78], and Henseler et al. [79] show how SEM and PLS-SEM are effective in managing multivariate relationships and latent variables. Furthermore, methodological contributions by Aiken et al. [80] and Hayes [81] in multivariate regression and mediation/moderation analysis enhance precision in exploring the complex interdependencies inherent in digital leadership research. Finally, the methodological efforts made in reducing method biases by Podsakoff and Organ [82], Podsakoff et al. [83], and Podsakoff et al. [84] provide more reliable and credible results.

Co-Citation Cluster 2: The Role of Leadership

This research area focuses on how leadership drives organizational change. Key documents include Cascio and Shurygailo [48] and Bell and Kozlowski [19] on leadership philosophies and organizational structure. The cluster features foundational e-leadership works by Avolio, Kahai and Dodge [30], Avolio and Kahai [85], and Avolio, Sosik, Kahai and Baker [86]. Additional documents in this cluster include Judge et al. [87] on personality and leadership; DeSanctis and Poole [88], Flanagan and Jacobsen [49], and Roman et al. [89] on leadership behaviors and decision-making; Gilson et al. [90], Purvanova and Bono [53], Davis [91], and Venkatesh et al. [92] on virtual teams and digital communication tools; and Kayworth and Leidner [93] on leadership in technology integration.

Co-Citation Cluster 3 (Blue): Leadership Innovation

The changing role of leadership and how it affects organizational adaptability are examined in this body of the literature. According to Nambisan et al. [94] and Nambisan [95], it is argued that leadership should be viewed as an innovative force that drives the necessary organizational change. Additionally, Tabrizi, Lam, Girard and Irvin [1] focus on how leaders face uncertainty and emphasize the importance of visionary leadership.

Co-Citation Cluster 4 (Yellow): Strategic Management

The primary focus of the literature in this cluster is the connection between strategic management and leadership. While Borah et al. [96] examine how leadership contributes to managing technological change and encouraging innovation in an increasingly dynamic digital environment, AlNuaimi, Singh, Ren, Budhwar and Vorobyev [16] investigate the pivotal role that leadership plays in driving digital transformation.

Additionally, this cluster also includes El Sawy, Kræmmergaard, Amsinck and Vinther [32], Kane, Palmer, Phillips, Kiron and Buckley [6], and Kane, Phillips, Copulsky and Andrus [21] on digital leadership and organizational strategy; Kane [97] on technology and digital transformation; Schiuma et al. [98] on transformative leadership competencies; and McCarthy et al. [99] on digital transformation leadership characteristics.

4.4. Keyword Analysis

4.4.1. Keyword Clustering

Based on the keyword co-occurrence matrix, CiteSpace applied various clustering algorithms to group closely related keywords into distinct clusters. The clustering results were visualized in the co-occurrence map (Figure 5), with similar keywords aggregating into each colored cluster, representing specific research themes. Table 2 shows the details in each cluster.

Figure 5.

Cluster co-occurrence map of keywords.

Table 2.

Details of Keyword Clustering.

The keyword clustering analysis identified several primary research themes within the field of digital leadership:

Cluster 0: Digital Transformation

This cluster is the largest, comprising 83 nodes with an average publication year 2017. Key terms such as “digital transformation,” “leadership support,” “information technology,” and “big data management” highlight the centrality of digital transformation in digital leadership research. This cluster focuses on leaders’ strategies and practices to drive digital change within organizations.

Cluster 1: Digital Leadership

This cluster, which has 59 nodes and an average publication year of 2019, includes keywords like “proactive personality,” “digital leadership,” and “boundary-spanning leadership.” This cluster demonstrates that academia is currently paying attention to the position and characteristics of leaders in the digital era.

Cluster 2: Social Media

This cluster consists of 57 nodes with an average publication year of 2014. The presence of terms such as “big data,” “disorder,” “primary care,” and “psychological treatment” highlights the significant role of social media.

Cluster 3: Virtual Teams

Comprising 56 nodes and an average publication year of 2008, the appearance of “virtual teams”, “virtual team leadership”, etc., represents a highly integrated direction in the research of digital leadership in the challenging digital virtual environment.

Cluster 4: Sustainable Development

Also comprising 56 nodes with an average publication year of 2018, this cluster features keywords such as “sustainable development,” “open innovation,” and “technological innovation. Although “sustainable development” as the label is not a primary keyword, its co-occurrence with related terms highlights its significance in digital leadership research.

4.4.2. Keyword Burst

Keyword burst analysis in CiteSpace identifies keywords that significantly increase citation frequency over specific periods, signaling emerging trends and research hotspots. The burst analysis map visualizes burst strength and the start and end years of bursts for each keyword. Greater burst strength indicates a more substantial increase in citation frequency during the burst period.

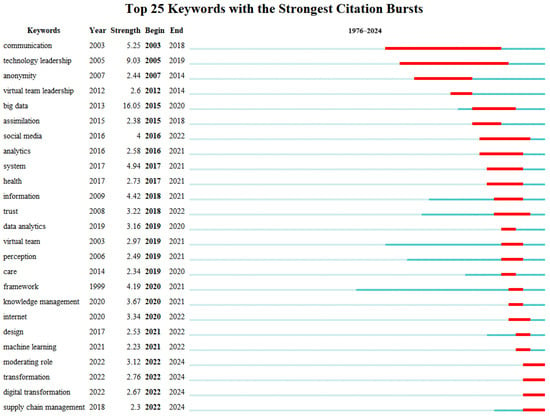

Figure 6 provides information on each keyword’s burst strength, start and end years, and overall citation timeframe, with red bars representing the burst period and blue–green bars indicating the total citation period. A detailed description of the highlighted keywords is provided below.

Figure 6.

Top 25 keywords with the strongest citation bursts.

Early Burst Keywords (2003–2012)

During the early period, keywords such as “communication” (2003–2018, burst strength 5.25), “technology leadership” (2005–2019, burst strength 9.03), and “virtual team leadership” (2012–2014, burst strength 2.6) highlight the early significance of communication and technology leadership in digital leadership research.

Mid-Term Burst Keywords (2013–2020)

In the mid-term period, “big data” (2013–2020, burst strength 16.05) emerged as the dominant burst keyword, reflecting the rapid growth in big data applications and highlighting the significant impact of data analysis on modern management practices. Additional keywords such as “social media” (2016–2022, burst strength 4), “analytics” (2016–2021, burst strength 2.58), and “virtual team” (2019–2021, burst strength 2.97) emphasize the growing roles of social media and data analytics in digital leadership.

Recent Burst Keywords (2021–2024)

In the recent period, keywords such as “machine learning” (2021–2022, burst strength 2.23), “digital transformation” (2022–2024, burst strength 2.67), and “supply chain management” (2022–2024, burst strength 2.3) indicate emerging research hotspots.

5. Discussion

To explore the intellectual structure of the digital leadership domain, this study employs a comprehensive science mapping-based review methodology, including regional co-occurrence analysis, document co-citation analysis, keyword clustering, and keyword burst detection.

The four co-citation clusters reveal influential works and their interconnections, thus providing insights into the foundational knowledge of a particular field [100]. As emphasized by Kim et al. [101], co-citation analysis can create a broad yet clustered overview of the field’s knowledge base, which is rooted in the structures captured within references, thereby enhancing our understanding within a specific domain.

Specifically, Cluster 1 as the core theoretical pillar integrates the dynamic capabilities theory, the resource-based view, and complex quantitative methodologies. However, the dominance of strategic management theory also highlights an imbalance in the theoretical landscape. While psychological and sociological perspectives are closely related to leadership phenomena, their representation remains insufficient. The imbalance in the application of this theory and research methods has led to the fragmentation of the theoretical framework.

Research in Cluster 2 focuses on how digital leadership drives organizational change through technology-driven interactions [16,32]. This cluster emphasizes the impact of leadership behaviors on organizations, starting from the individual level. It is noteworthy that the boundary between Cluster 2 and Cluster 4 is somewhat blurred. Both clusters explore the role of digital leadership, suggesting potential theoretical overlap, with both emphasizing the significance of digital leadership at the organizational level.

Cluster 3 positions digital leadership as an innovative force, rather than merely a technology enabler. The emergence of this cluster marks a paradigm shift, from viewing digital leadership as a tool for managing technology to considering it as a critical enabler of organizational transformation [9]. The distinction between Cluster 2 and Cluster 3 lies in the differentiation between change management (Cluster 2) and innovation capabilities (Cluster 3).

Cluster 4 highlights the shift in the field from operational issues to strategic needs [7,21,102]. The close connection between strategic management and Cluster 1 emphasizes the consistency of theoretical frameworks. However, the focus of Cluster 4 on digital transformation distinguishes it from the theoretical approaches of Cluster 1.

The analysis of these four clusters reveals two key observations: The limited cross-cluster citation patterns indicate a lack of sufficient theoretical dialog between strategic, behavioral, and innovation perspectives [5,24], which validates the theoretical fragmentation mentioned in the introduction. And the methodological centralization in Cluster 1 exposes the limitations of the research methods, which may constrain the development of theory.

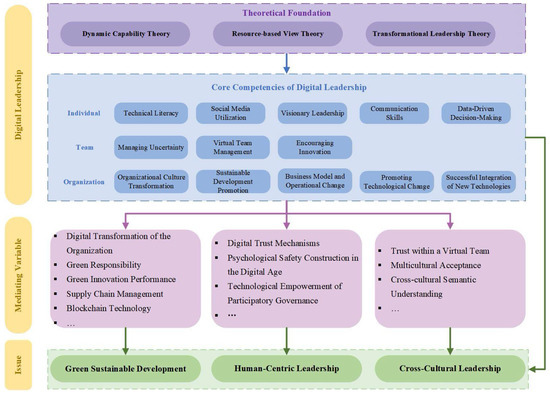

To comprehensively understand the evolution and future development directions of digital leadership, this study constructs a systematic knowledge map that progressively builds a multi-level system structure encompassing core competencies, mediating mechanisms, and strategic outcomes, grounded in meta-theoretical foundations, as illustrated in Figure 7. The subsequent sections will explain how this map is constructed based on the results of the literature data analysis.

Figure 7.

Knowledge map and future agenda of digital leadership research.

5.1. Knowledge Structure and Evolution of Digital Leadership

The findings reveal that digital leadership is not an unfounded emerging field, but rather a domain that integrates knowledge from multiple disciplines. However, early research was often confined to isolated disciplinary perspectives [5,24]. The analysis result demonstrates systematic integration of theories and methodologies from psychology, sociology, strategic management, and information systems [88,102,103], providing a foundation for further interdisciplinary theoretical and methodological research.

The publication trend analysis reveals that related research emerged as early as 1991, indicating that information technology-mediated leadership approaches, along with studies on virtual teams and remote management, had already appeared in the 1990s [30,48]. Research volume remained relatively modest until 2016, when the field formally entered a period of rapid growth. This temporal evolution highlights how digital leadership has transformed from a niche topic concerning technology adoption into a core strategic imperative for organizational survival and competitiveness in the digital age [7,21,102]. As technology has advanced, digital leadership research has evolved from its initial focus on technology application to organizational strategic management [16,32]. This development reflects a paradigm shift indicating that digital leadership is no longer merely about using technology, but rather about leveraging technology to fundamentally reshape organizational goals, processes, and value creation [9]. This evolution reflects broader societal transformation and, more importantly, suggests that future leadership theory may abandon the distinction between “digital” and “traditional” leadership.

From the regional co-occurrence analysis, it is evident that digital leadership research has expanded beyond traditionally technology-driven nations to encompass various regions. With the increasing participation of emerging economies, the global cooperation network for digital leadership research is expected to become more interconnected and inclusive, with research on digital leadership extending beyond technologically advanced nations [35]. This shift in research focus also underscores the integration of digital leadership across different cultures, emphasizing the growing importance of digital leadership for cross-cultural management.

5.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

The framework is anchored in three complementary meta-theories that collectively explain the digital leadership phenomenon: DCT, RBV, and Transformational Leadership Theory. DCT provides a lens for understanding how digital leaders sense opportunities, seize opportunities, and reconfigure organizational resources in rapidly changing digital environments [38]. RBV complements this by elucidating how digital leadership constructs organizational resources to generate sustainable competitive advantages [73]. Transformational Leadership Theory focuses on the human dimension, explaining how digital leaders inspire, motivate, and empower followers to embrace technological change and achieve exceptional outcomes in digitalized environments [3]. The integration of these three meta-theories addresses calls for theoretical depth in cross-boundary research and reflects the field’s evolution from isolated disciplinary perspectives toward integrated theoretical frameworks. This meta-theoretical foundation provides the necessary conceptual framework for understanding digital leadership across different organizational levels and contexts.

Based on the bibliometric analysis results and three complementary theoretical foundations, this study identifies five core competencies of digital leadership, through a combination of quantitative analysis and logical reasoning.

From Cluster 1, with keywords such as “digital literacy”, “proactive personality”, and “boundary-spanning leadership”, digital literacy emerges as a core competency. Digital literacy suggests that digital leaders must possess the ability to acquire, understand, and apply information in rapidly changing digital environments, which aligns with DCT [8,23,104]. Social media application capabilities emerge from Cluster 2, emphasizing the critical role of social media in virtual team management and cross-regional collaboration [53,90]. While digital leadership has evolved beyond simply using technology, social media remains an essential tool. In Cluster 3, innovation and change management capabilities are closely linked to visionary leadership, emphasizing a leader’s ability to guide an organization’s future in the context of technological change [6]. Communication skills are also essential in ensuring strategic goals are conveyed and cross-department collaboration is smooth during digital transformation [23]. The keyword burst analysis validates data-driven decision-making abilities through keyword burst analysis, particularly in the frequent appearance of data analytics skills related to big data and analytics. As information technology progresses, digital leaders need to leverage data to make precise decisions, enhancing organizational efficiency and market competitiveness [21].

Thus, this study delineates the five core competencies of digital leadership: digital literacy, social media application capabilities, visionary leadership, communication skills, and data-driven decision-making abilities. These core competencies exert influence across different levels. At the individual level, competencies constitute the foundational capabilities that digital leaders must cultivate. In digital environments, leaders leverage technology to mediate interpersonal interactions and utilize data to inform decision-making processes [21]. At the team level, digital leadership manifests in practices that facilitate effective collaboration in increasingly virtualized and distributed work environments [19,53,90]. At the organizational level, digital leadership capabilities promote collaborative digital practices that drive systemic change and strategic outcomes [16,32]. Digital leadership transcends individual or team efficiency, fundamentally reshaping organizational strategy, structure, and competitive positioning.

5.3. Future Directions and Research Limitations

The research results also reveal three key future research directions, which are not prescriptive suggestions but rather reflect the empirical trajectories of contemporary global challenges and academic concerns.

Green sustainable development shows multiple converging signals in the research analysis. The explosive growth of the recent keyword “supply chain management” (2022–2024, burst strength 2.3), and in Cluster 3 and Cluster 4 (“sustainable development,” “supply chain management,” and “blockchain technology”; and recent burst keywords: “supply chain management”), reflects the increasing academic focus on the environmental dimension of digital leadership, particularly in promoting green innovation and optimizing supply chain transparency. The emergence of blockchain technology further underscores the necessity of digital technologies in facilitating sustainable business models, providing the technical infrastructure required for supply chain transparency and traceability. The theoretical connection between DCT and green sustainable development has become increasingly evident.

The emphasis on “psychological well-being” and “job demands” in Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 (Cluster 1: “psychological well-being,” “job demands,” and “proactive personality”; Cluster 2: “patient-centered care” and “psychological treatment”; and mid-term burst keywords: trust and care), along with the mid-term burst keywords of “trust” and “care,” highlights the growing importance of human well-being in digital leadership. Transformational Leadership Theory reveals the critical role of trust, transparency, and participation in people-centered leadership. Therefore, digital leaders must adopt a human-centered leadership approach, fostering trust through continuous communication, demonstrating reliability, and increasing participation.

Cross-cultural leadership emerges strongly in the regional co-occurrence analysis. With the increasing research output and centrality scores from emerging economies, such as India, Malaysia, and Pakistan, digital leadership theory is gradually moving beyond the assumptions rooted in Western organizations. The co-occurrence of “boundary-spanning leadership” in Cluster 1 and “open innovation” in Cluster 4 underscores the role of digital platforms in facilitating global collaboration while also exposing cultural differences, particularly in communication styles, authority relations, and collaboration norms.

These three future research directions are not independent but interconnected, collectively advancing digital leadership research from a focus on technological applications to a more responsible management approach, ensuring environmental sustainability, human well-being, and cultural inclusivity. This shift reflects growing societal concerns about the consequences of technology and positions digital leadership research at the intersection of technological potential and social responsibility.

The knowledge map presented in Figure 7 demonstrates considerable universality and applicability across diverse organizational contexts. To further illustrate the practical application of this framework and validate its transferability, we examine the construction industry as an exemplary case. The construction industry possesses unique characteristics and faces specific challenges that make digital leadership especially important [105,106]. Unlike industries with centralized operations, construction projects involve decentralized ecosystems that include multiple stakeholders [107], temporary project teams [108], and varying levels of technological maturity. This decentralization presents unique demands on leaders in the construction field, who must coordinate across organizational boundaries and manage virtual teams spread across construction sites. Digital leadership effectively addresses these issues by providing the tools and strategies necessary to navigate these complexities [105,106]. Furthermore, despite the sector’s gradual yet accelerating digital transformation—seen in the application of Building Information Modeling (BIM), Internet of Things (IoT), and digital twins—the construction industry significantly lags behind other sectors in digital transformation, making effective digital leadership not merely beneficial but critically urgent [2,109,110,111]. These industry-specific characteristics position construction as an ideal domain to demonstrate how the proposed knowledge map can be contextualized and operationalized to address sector-specific challenges.

5.3.1. Green Sustainable Development

Based on the RBV and DCT, digital leadership leverages digital tools to drive environmental protection and enhance resource efficiency [9,112]. Digital leaders are key drivers in leading construction companies towards green transformation and sustainable goals. This is mainly reflected in the following aspects:

Firstly, digital leaders use digital platforms to achieve real-time monitoring and precise management of resource information. For instance, technologies such as BIM, IoT, and digital twins enable construction leaders to conduct evaluations before construction, optimize decision-making during operations [113,114], and even perform life-cycle analysis and optimization, thus supporting predictive information management, extending building lifespans, and reducing resource consumption [111]. Furthermore, digitalization fosters green innovation, driving the adoption of new products, processes, and business models. Digital leadership also enhances construction supply chain management by utilizing technologies like the blockchain to trace the “greenness” of resources within the supply chain, improving environmental accountability and transparency [110].

5.3.2. Human-Centered Leadership

In the construction industry, which is heavily safety-oriented, leaders must consistently focus on human dignity and well-being as technology advances, ensuring that technological development serves the long-term interests of humanity [52]. Digital leadership requires leaders to possess technical sensitivity, emotional intelligence, and humanistic care [115].

While digital technologies enhance work efficiency, they also introduce challenges such as human–machine trust issues and information distortion, which can undermine trust between individuals and machines [116,117]. As a result, digital leadership necessitates timely adjustments to trust strategies, avoiding both excessive and insufficient trust [117]. For interpersonal trust, digital leaders must establish standardized, open, and transparent communication channels [118]. Building trust relies not only on technological support but also on leaders demonstrating respect and care for employees throughout the management process [75].

5.3.3. Cross-Cultural Leadership

When team members are distributed across different time zones and cultural environments, effectively managing cross-cultural teams becomes a core issue that leaders must address [35]. As international construction projects evolve, cross-cultural project teams have become mainstream, and leaders must understand and adapt to cultural differences among team members based on digital technology, which is crucial for successful cross-cultural communication [119]. In international construction projects, designers, contractors, suppliers, and regulatory bodies from various countries and cultural backgrounds are involved [120]. Digital leadership plays a crucial role in bridging the demands of cross-cultural leadership:

Digital leadership provides flexible communication systems for cross-cultural teams through the proficient use of social media and digital collaboration platforms, improving communication efficiency and breaking down geographical and cultural barriers [121]. The “big data” characteristics of social media offer leaders more precise decision-making support. By analyzing social media data, leaders can gain deeper insights into the needs and feedback of team members from diverse cultural backgrounds, allowing them to adjust leadership strategies and communication approaches accordingly [122]. Digital collaboration platforms enable personnel from different cultural and professional backgrounds to jointly design, evaluate, and innovate within the same digital space, facilitating the development of innovative solutions and high-quality work [121].

5.4. Research Limitations

Despite the insights provided, this review and its methods have several limitations. A primary limitation arises from the reliance on data sourced from the WoS core database. While efforts were made to include a broad set of search terms, some of the relevant literature may have been unintentionally excluded from the parameters. Given the dynamic nature of databases, the time-sensitive nature of the science mapping-based review highlights the need for ongoing research to address these limitations. Additionally, despite the inclusion of 960 relevant papers and their citations from the WoS database, some papers may have been omitted, particularly those not authored in English, not fully indexed, or not yet digitized within the WoS database. In addition, this excludes potentially influential book chapters, conference proceedings, and qualitative dissertations that may offer rich theoretical insights not captured in journal articles. While this decision ensures methodological consistency and citation network analysis feasibility, it may underrepresent theoretical development work and practice-oriented scholarship.

6. Conclusions

This study analyzes 960 articles from the Web of Science database by employing scientific mapping methods, providing a structured, evidence-based understanding of digital leadership, thereby transcending the limitations of traditional narrative reviews. This study contributes to constructing the knowledge map (Figure 7), which thoroughly illustrates the knowledge structure of digital leadership and the future research agenda, providing scholars and practitioners with a theoretical framework for understanding the evolution of the field and addressing future challenges.

Through bibliometric co-citation analysis, this study identifies and critically examines four foundational knowledge clusters within digital leadership research: (1) theoretical foundations, integrating DCT, the RBV, and advanced quantitative methods; (2) the role of leadership, exploring technology-mediated organizational change; (3) leadership innovation, positioning digital leadership as a catalyst for organizational transformation; and (4) strategic management, linking digital leadership to competitive advantage. While elucidating the knowledge base of the field, the analysis also critically reveals the fragmentation issues, including a lack of interdisciplinary research, methodological centralization, and a gap in human-centered research. The knowledge map integrates empirical evidence from keyword clustering, co-citation patterns, and burst detection, identifying five core digital leadership competencies: digital literacy, social media application capabilities, visionary leadership, communication skills, and data-driven decision-making abilities. Additionally, the map highlights key mediating mechanisms. This multi-level framework overcomes the limitations of the previously dominant single-level analysis in the field and provides a structured foundation for examining the multidimensional impacts of digital leadership. Furthermore, through a systematic use of bibliometric evidence, this study distills three prominent future research directions: green sustainable development, human-centered leadership, and cross-cultural leadership. These directions not only have significant academic implications but also profound practical impacts.

To enhance the understanding of the knowledge map, we use the construction industry as an example. The sector’s unique characteristics make digital leadership particularly important. In green sustainable development, digital leadership is the key to driving innovation and optimizing supply chain transparency. For human-centered leadership, it helps manage diverse, geographically dispersed teams, fostering engagement and trust. In cross-cultural leadership, digital leadership enables leaders to navigate cultural differences and facilitate global collaboration. Overall, digital leadership in the construction industry addresses specific challenges and offers valuable guidance for future digital transformations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/buildings16010095/s1, PRISMA 2020 checklist [123].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Z.; methodology, Z.Z., S.L. and P.C.; software, Z.Z.; validation, P.C., Z.Z. and M.S.; formal analysis, Z.Z. and M.S.; investigation, Z.Z.; resources, B.Z.; data curation, Z.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Z.; writing—review and editing, B.Z.; S.L., M.S. and P.C.; visualization, Z.Z.; supervision, X.D.; project administration, X.D.; funding acquisition, X.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Anhui Research Center of Construction Economy and Real Estate Management (funding number: 2024JZJJ01).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the School of Economics and Management at Anhui Jianzhu University for providing technical support to conduct this research. The authors also acknowledge the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments. All authors have consented to the acknowledgement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tabrizi, B.; Lam, E.; Girard, K.; Irvin, V. Digital transformation is not about technology. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2019, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Musarat, M.A.; Hameed, N.; Altaf, M.; Alaloul, W.S.; Al Salaheen, M.; Alawag, A.M. Digital transformation of the construction industry: A review. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Application (DASA), Virtual Conference, 7–8 December 2021; pp. 897–902. [Google Scholar]

- Senadjki, A.; Au Yong, H.N.; Ganapathy, T.; Ogbeibu, S. Unlocking the potential: The impact of digital leadership on firms’ performance through digital transformation. J. Bus. Socio-Econ. Dev. 2023, 4, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espina-Romero, L.; Noroño Sánchez, J.G.; Rojas-Cangahuala, G.; Palacios Garay, J.; Parra, D.R.; Rio Corredoira, J. Digital leadership in an ever-changing world: A bibliometric analysis of trends and challenges. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yücebalkan, B.; Eryılmaz, B.; Özlü, K.; Keskin, Y.; Yücetürk, C. Digital leadership in the context of digitalization and digital transformations. Curr. Acad. Stud. Soc. Sci. 2018, 1, 489–505. [Google Scholar]

- Kane, G.C.; Palmer, D.; Phillips, A.N.; Kiron, D.; Buckley, N. Strategy, not technology, drives digital transformation. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2015, 14, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Westerman, G.; Bonnet, D.; McAfee, A. Leading Digital: Turning Technology into Business Transformation; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fatima, T.; Masood, A. Impact of digital leadership on open innovation: A moderating serial mediation model. J. Knowl. Manag. 2024, 28, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, H.; Albadry, O.M.; Mathew, V.; Al-Romeedy, B.S.; Alsetoohy, O.; Abou Kamar, M.; Khairy, H.A. Digital leadership and sustainable competitive advantage: Leveraging green absorptive capability and eco-innovation in tourism and hospitality businesses. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaw, T.Y.; Teoh, A.P.; Khalid, S.N.A.; Letchmunan, S. The impact of digital leadership on sustainable performance: A systematic literature review. J. Manag. Dev. 2022, 41, 514–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, K.S.R.; Wäger, M. Building dynamic capabilities for digital transformation: An ongoing process of strategic renewal. Long Range Plan. 2019, 52, 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, J.; Holmström, J.; Lyytinen, K. Digitization and Phase Transitions in Platform Organizing Logics: Evidence from the Process Automation Industry. Manag. Inf. Syst. Q. 2020, 44, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzmüller, T.; Brosi, P.; Duman, D.; Welpe, I.M. How Does the Digital Transformation Affect Organizations? Key Themes of Change in Work Design and Leadership. Manag. Rev. 2018, 29, 114–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, A.; El Sawy, O.A.; Pavlou, P.A.; Venkatraman, N. Digital Business Strategy: Toward a Next Generation of Insights. MIS Q. 2013, 37, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, G. Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. In Managing Digital Transformation; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 13–66. [Google Scholar]

- AlNuaimi, B.K.; Singh, S.K.; Ren, S.; Budhwar, P.; Vorobyev, D. Mastering digital transformation: The nexus between leadership, agility, and digital strategy. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 145, 636–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Lin, X.; Sheng, F. Digital leadership and exploratory innovation: From the dual perspectives of strategic orientation and organizational culture. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 902693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, S.; Tutar, H. Digital Leadership As A Requirement For The New Business Ecosystem: A Conceptual Review. Çankırı Karatekin Üniversitesi İktisadi İdari Bilim. Fakültesi Derg. 2022, 12, 323–349. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, B.S.; Kozlowski, S.W. A typology of virtual teams: Implications for effective leadership. Group Organ. Manag. 2002, 27, 14–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambley, L.A.; O’Neill, T.A.; Kline, T.J. Virtual team leadership: The effects of leadership style and communication medium on team interaction styles and outcomes. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2007, 103, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, G.C.; Phillips, A.N.; Copulsky, J.; Andrus, G. How digital leadership is (n’t) different. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2019, 60, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sağbaş, M.; Erdoğan, F.A. Digital leadership: A systematic conceptual literature review. İstanbul Kent Üniversitesi İnsan Toplum Bilim. Derg. 2022, 3, 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Tigre, F.B.; Curado, C.; Henriques, P.L. Digital leadership: A bibliometric analysis. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2023, 30, 40–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakose, T.; Kocabas, I.; Yirci, R.; Papadakis, S.; Ozdemir, T.Y.; Demirkol, M. The development and evolution of digital leadership: A bibliometric mapping approach-based study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaid, A.; Abd Rozan, M.Z.; Hikmi, S.N.; Memon, J. Knowledge maps: A systematic literature review and directions for future research. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 451–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, M.; Sang, P. A bibliometric review of studies on construction and demolition waste management by using CiteSpace. Energy Build. 2022, 258, 111822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Z.; Herbert, K. Safety leadership: A bibliometric literature review and future research directions. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 172, 114437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertz, M.; Leblanc-Proulx, S. Sustainability in the collaborative economy: A bibliometric analysis reveals emerging interest. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 1073–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupic, I.; Čater, T. Bibliometric Methods in Management and Organization. Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 18, 429–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Kahai, S.; Dodge, G.E. E-leadership: Implications for theory, research, and practice. Leadersh. Q. 2000, 11, 615–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahanna, E.; Watson, R.T. Information systems leadership. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2006, 53, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sawy, O.A.; Kræmmergaard, P.; Amsinck, H.; Vinther, A.L. How LEGO built the foundations and enterprise capabilities for digital leadership. In Strategic Information Management; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 174–201. [Google Scholar]

- Jameson, J.; Rumyantseva, N.; Cai, M.; Markowski, M.; Essex, R.; McNay, I. A systematic review and framework for digital leadership research maturity in higher education. Comput. Educ. Open 2022, 3, 100115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartsch, S.; Weber, E.; Büttgen, M.; Huber, A. Leadership matters in crisis-induced digital transformation: How to lead service employees effectively during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Serv. Manag. 2020, 32, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapucu, H. Business leaders’ perception of digital transformation in emerging economies: On leader and technology interplay. Int. J. Adv. Corp. Learn. 2021, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdali, M.A.; Yaqub, M.Z.; Agarwal, R.; Alofaysan, H.; Mohapatra, A.K. Unveiling green digital transformational leadership: Nexus between green digital culture, green digital mindset, and green digital transformation. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 450, 141670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortellazzo, L.; Bruni, E.; Zampieri, R. The role of leadership in a digitalized world: A review. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civelek, M.; Krajčík, V.; Ključnikov, A. The impacts of dynamic capabilities on SMEs’ digital transformation process: The resource-based view perspective. Oeconomia Copernic. 2023, 14, 1367–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q. Digital leadership: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2024, 28, 2469–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, G.C.; Dionne, S.D.; Mast, M.S.; Sayama, H. Leadership in the digital era: A review of who, what, when, where, and why. Leadersh. Q. 2022, 33, 101634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, P.J.-H.; Brown, S.A.; Chen, H. Knowledge mapping for rapidly evolving domains: A design science approach. Decis. Support Syst. 2011, 50, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppler, M.J. Making knowledge visible through intranet knowledge maps: Concepts, elements, cases. In Proceedings of the 34th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 6 January 2001; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Börner, K.; Chen, C.; Boyack, K.W. Visualizing knowledge domains. Annu. Rev. Inf. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2003, 37, 179–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallaster, C.; Kraus, S.; Merigó Lindahl, J.M.; Nielsen, A. Ethics and entrepreneurship: A bibliometric study and literature review. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 99, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2009, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, C.; Teh, S.Y.; Alnoor, A.; Shao, M. Trends of the digital transformation and green innovation using PRISMA and bibliometric analysis review. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascio, W.F.; Shurygailo, S. E-leadership and virtual teams. Organ. Dyn. 2003, 31, 362–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, L.; Jacobsen, M. Technology leadership for the twenty-first century principal. J. Educ. Adm. 2003, 41, 124–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yan, S.; Jiang, H.-Y. The Effect of E-leadership on Employee Engagement—Based on the Mediating Effect of Perceived Organizational Support. Soft Sci. 2018, 32, 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Oberer, B.; Erkollar, A. Leadership 4.0: Digital leaders in the age of industry 4.0. Int. J. Organ. Leadersh. 2018, 7, 404–412. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, V.; Mittal, A. Leadership in a Digital-First Era. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2024, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvanova, R.K.; Bono, J.E. Transformational leadership in context: Face-to-face and virtual teams. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitan, T.; Gazit, T. Explaining transformational leadership in the digital age: The example of Facebook group leaders. Technol. Soc. 2024, 78, 102637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Pitsouni, E.I.; Malietzis, G.A.; Pappas, G. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: Strengths and weaknesses. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, R. Knowledge management and performance: A bibliometric analysis based on Scopus and WOS data (1988–2021). J. Knowl. Manag. 2022, 27, 1948–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, G.; Pérez-Llantada, C.; Plo, R. English as an international language of scientific publication: A study of attitudes. World Englishes 2011, 30, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, T.; Yang, L.; Xianguo, W. Research on International Engineering Safety Management Research Based on Knowledge Map. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 233, 022017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.-N.; Lee, P.-C. Mapping knowledge structure by keyword co-occurrence: A first look at journal papers in Technology Foresight. Scientometrics 2010, 85, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Morris, S. Visualizing evolving networks: Minimum spanning trees versus pathfinder networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Information Visualization 2003 (IEEE Cat. No. 03TH8714), Seattle, WA, USA, 19–21 October 2003; pp. 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Lin, X.; Yin, S.; Zhu, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, B.; Jiao, Y.; Yu, W.; Gao, P.; et al. Emerging Trends and Hot Spots in Hepatic Glycolipid Metabolism Research From 2002 to 2021: A Bibliometric Analysis. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 933211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C. CiteSpace II: Detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2006, 57, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, H.D.; McCain, K.W. Visualizing a discipline: An author co-citation analysis of information science, 1972–1995. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1998, 49, 327–355. [Google Scholar]

- Cobo, M.J.; López-Herrera, A.G.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F. Science mapping software tools: Review, analysis, and cooperative study among tools. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 62, 1382–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Du, Y.; Jin, Y.; Liu, F.; He, S.; Guo, Y. Articles on hemorrhagic shock published between 2000 and 2021: A CiteSpace-Based bibliometric analysis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, R. The visible colleges of management and organization studies: A bibliometric analysis of academic journals. Organ. Stud. 2012, 33, 1015–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, T.; Qian, Q.K.; Visscher, H.J.; Elsinga, M.G. Stakeholders’ Expectations in Urban Renewal Projects in China: A Key Step towards Sustainability. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.-P.; Yang, C.C.; Lin, C.-M. A Latent Semantic Indexing-based approach to multilingual document clustering. Decis. Support Syst. 2008, 45, 606–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Xiong, B.; Li, W.; Lan, F.; Evans, R.; Zhang, W. Visualizing collaboration characteristics and topic burst on international mobile health research: Bibliometric analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e9581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Z.; Ji, W.; Yu, S.; Cheng, G.; Yuan, Q.; Han, Z.; Liu, H.; Yang, T. Mapping the knowledge of traffic collision Reconstruction: A scientometric analysis in CiteSpace, VOSviewer, and SciMAT. Sci. Justice 2023, 63, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Hu, Z.; Liu, S.; Tseng, H. Emerging trends in regenerative medicine: A scientometric analysis in CiteSpace. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2012, 12, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. CiteSpace: A Practical Guide for Mapping Scientific Literature; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansil, M.S.C.; Sujuti, A.F. Understanding the concept of servant leadership in the digital age through keywords mapping. J. Strateg. Glob. Stud. 2024, 7, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer Nature: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avolio, B.J.; Kahai, S.S. Adding the “E” to E-leadership: How it may impact your leadership. Organ. Dyn. 2003, 31, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Sosik, J.J.; Kahai, S.S.; Baker, B. E-leadership: Re-examining transformations in leadership source and transmission. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Bono, J.E.; Ilies, R.; Gerhardt, M.W. Personality and leadership: A qualitative and quantitative review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSanctis, G.; Poole, M.S. Capturing the complexity in advanced technology use: Adaptive structuration theory. Organ. Sci. 1994, 5, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, A.V.; Van Wart, M.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Kim, S.; McCarthy, A. Defining e-leadership as competence in ICT-mediated communications: An exploratory assessment. Public Adm. Rev. 2019, 79, 853–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, L.L.; Maynard, M.T.; Jones Young, N.C.; Vartiainen, M.; Hakonen, M. Virtual teams research: 10 years, 10 themes, and 10 opportunities. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 1313–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayworth, T.R.; Leidner, D.E. Leadership effectiveness in global virtual teams. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2002, 18, 7–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S.; Lyytinen, K.; Majchrzak, A.; Song, M. Digital innovation management. MIS Q. 2017, 41, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S. Digital entrepreneurship: Toward a digital technology perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 1029–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, P.S.; Iqbal, S.; Akhtar, S. Linking social media usage and SME’s sustainable performance: The role of digital leadership and innovation capabilities. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, G. The technology fallacy: People are the real key to digital transformation. Res.-Technol. Manag. 2019, 62, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiuma, G.; Schettini, E.; Santarsiero, F.; Carlucci, D. The transformative leadership compass: Six competencies for digital transformation entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. Policy 2022, 28, 1273–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, P.; Sammon, D.; Alhassan, I. Digital transformation leadership characteristics: A literature analysis. J. Decis. Syst. 2022, 32, 79–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurzki, H.; Woisetschläger, D.M. Mapping the luxury research landscape: A bibliometric citation analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 77, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kang, S.; Lee, K.H. Evolution of digital marketing communication: Bibliometric analysis and network visualization from key articles. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 130, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]