Abstract

The durability of concrete in immersed tunnels is critically influenced by the coupled effects of stress, seepage, and chemical erosion, particularly in inland water environments. However, the spatio-temporal evolution of mechanical property degradation under such multi-field coupling remains insufficiently quantified. Unlike previous studies focused on “load-ion” or “hydraulic pressure-ion” dual coupling, this work introduces a complete stress–seepage–chemical tri-coupling that incorporates the critical seepage effect, representing a fundamental expansion of the experimental scope to better simulate real-world conditions. This study investigates the degradation mechanisms of concrete in the Shunde Lungui Road inland immersed tunnel subjected to such coupled erosion. A novel aspect of our approach is the application of the micro-indentation technique to quantitatively characterize the spatio-temporal evolution of the local elastic modulus at an unprecedented spatial resolution (0.5 mm intervals), a dimension of analysis not achievable by conventional macro-scale testing. Key findings reveal that the mechanical properties of concrete exhibit an initial enhancement followed by deterioration. This behavior is attributed to the filling of pores by reaction products (gypsum, ettringite, and Friedel’s salt) in the short term, which subsequently induces microcracking as the volume of products exceeds the pore capacity. Furthermore, increasing hydro-mechanical loading significantly accelerates the erosion process. When the load increases from 1.596 kN to 3.718 kN, the influence range of elastic modulus variation expands by 9.2% (from 5.186 mm to 5.661 mm). To quantitatively describe this acceleration effect, a novel load-acceleration erosion coefficient is proposed. The erosion rate increases from 0.0688 mm/d to 0.0778 mm/d, yielding acceleration coefficients between 1.100 and 1.165, quantifying a 10–16.5% acceleration effect beyond what is typically captured in dual-coupling models. These quantitative results provide critical parameters for employing laboratory accelerated tests to evaluate the ionic erosion durability of concrete structures under various loading conditions, thereby contributing to more accurate service life predictions for engineering structures.

1. Introduction

In recent years, China’s pursuit of becoming a “transportation power” has been accompanied by rapid development in urban road traffic. This growth has led to the construction of an increasing number of major cross-river and cross-sea transportation projects. With the increasing maturity of immersed tunnel technology, numerous inland river tunnels have been constructed [1,2,3], such as the Nanchang Honggu Tunnel and the Tianjin Central Avenue Haihe Tunnel, among others. The successful application of these inland immersed tunnels is significant for urban traffic. It enhances connectivity between key regions on both sides of the river, alleviates existing cross-river traffic pressure, and improves traffic efficiency. Consequently, it facilitates rapid economic development, promotes deeper urban integration, and meets citizens’ travel demands.

Immersed tube tunnel structures remain under prolonged coupled exposure to stress, seepage, and chemical ion erosion during their service life [4,5]. Mechanical stress originates from overburden and hydrostatic pressure, seepage comprises both Darcy flow driven by head gradients and the advective action of moving water, while chemical attack denotes the ingress of aggressive river-water ions. Compared to the high-chloride marine environment in which subsea immersed tunnels are situated, inland waterway tunnels are subjected to fundamentally different service conditions due to distinct hydrochemical and hydraulic regimes. Inland systems, such as the Tanzhou Waterway examined in this study, exhibit several notable characteristics: (1) a complex multi-ion chemical environment with variable sulfate–chloride–bicarbonate ratios, which differs markedly from the stable ionic composition of seawater [6]; (2) a dynamic flow regime characterized by seasonal velocity variations, leading to unsteady mass transfer conditions [7]; and (3) considerable bicarbonate content, which buffers pH and alters reaction pathways compared to marine settings [8]. In practice, concrete is exposed to multiple, simultaneous degradation drivers whose effects are not additive but synergistic; single-factor studies therefore inadequately reflect the true extent of damage, underscoring the need for multi-factor coupling research. Existing work has addressed single-ion [9] and multi-ion attack [10], load–ion coupling [11], and hydrostatic-pressure–ion interactions, yet the full stress–seepage–ion triad representative of submerged service conditions remains poorly understood. Moreover, deterioration mechanisms have been explored predominantly for offshore immersed tunnels, leaving inland river tunnels largely unexplored [12].

In addition, stress is a critical factor influencing the deterioration of concrete. Under sustained stress, microcracks can initiate within concrete. These cracks facilitate the ingress and diffusion of corrosive chemicals, thereby accelerating the deterioration process. Therefore, investigating the deterioration laws of concrete under various stress states is essential for ensuring the structural integrity and extending the service life of immersed tunnels. Concurrently, the current approach to assessing the service performance degradation of eroded concrete is primarily based on an indirect metric: the loss of overall mechanical properties (especially stiffness and load-bearing capacity) in specimens subjected to single-ion or coupled erosion [13,14,15,16,17]. This approach provides an approximate indication of the overall performance loss. However, during the physicochemical reactions between concrete and an aggressive solution, the mechanical properties of its various components do not degrade uniformly. Traditional macroscopic tests, such as uniaxial and triaxial compression, are ineffective for pinpointing which specific components have deteriorated or for accurately quantifying the extent of degradation. Consequently, relying solely on macroscopic mechanical properties to evaluate performance degradation is an oversimplification that may lead to inaccurate assessments.

To bridge these gaps, this study sets out to systematically examine the deterioration of concrete in inland immersed tunnels subjected to coupled stress–seepage–chemical actions. The contribution is articulated through three key novelties: Firstly, we employ microindentation to quantitatively map the spatiotemporal evolution of concrete’s local elastic modulus, offering a breakthrough beyond conventional macro-mechanical methods. Secondly, our experiment uniquely replicates the complex, real-world tri-field coupling conditions (stress–seepage–chemical) characteristic of inland waterways, a domain previously underexplored. Thirdly, we derive from our results a novel load-accelerated erosion coefficient that quantifies the acceleration of chemical erosion by mechanical stress. Ultimately, this work delivers quantitative insights into concrete’s micromechanical degradation and provides critical parameters for designing laboratory accelerated tests to predict the long-term durability of concrete structures under combined mechanical and environmental loading.

2. Engineering Background

Set against the backdrop of the Lungui Road Project in Shunde District, Foshan City, this research investigates concrete degradation mechanisms. The 7 km project features a 1200 m tunnel beneath the Tanzhou Waterway, with a 316 m segment constructed as an immersed tube. This tunnel structure faces complex service conditions, including simultaneous actions from overburden pressure and river water erosion [18], which can deteriorate the concrete’s mechanical performance. It is precisely these challenges that motivate the present study to ensure the long-term durability and structural safety of the tunnel.

3. Sample Preparation and Test Equipment

3.1. Sample Preparation and Processing

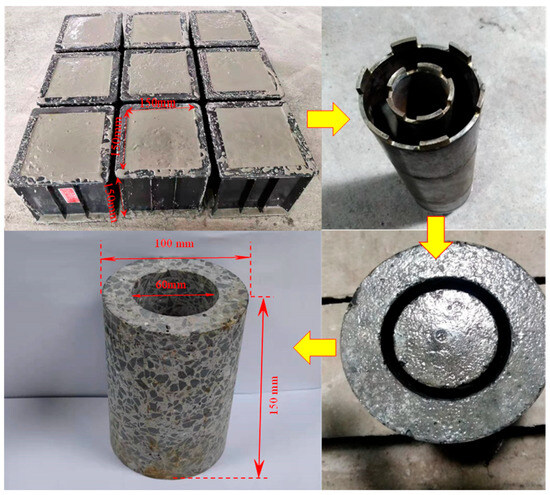

Concrete specimens of C45 strength grade were cast in the laboratory, employing the same mix proportion as that used in the Lungui Road Immersed Tunnel project (see Table 1). Ordinary Portland cement was utilized, which exhibited a specific surface area of 350.0 m2/kg. The fly ash and slag powder possessed specific surface areas of 425 m2/kg and 500 m2/kg, respectively. The sand had a continuous grading ranging from 0.15 to 4.75 mm, with a fineness modulus of 2.5. Its mud content, surface-saturated dry water absorption, and specific gravity were 2.8%, 3.0%, and 2.60 g/cm3, respectively. The crushed stone, with a continuous grading of 4.75 to 25 mm, was in an oven-dried condition. It demonstrated a water absorption of 0.5%, an apparent density of 2.7 g/cm3, and a bulk density of 1.8 g/cm3. A water-reducing admixture of type AS-2 was employed, which had a density of 1.12 kg/L. After curing, the standard cube specimens (150 mm × 150 mm × 150 mm) were machined into hollow cylinders. The resulting cylindrical specimens featured an inner diameter of 60.0 mm, an outer diameter of 100 mm, and a height of 150.0 mm. The machining procedure is illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Concrete Mix Proportions for the Immersed Tunnel on Lungui Road (kg/m3).

Figure 1.

Processing Flowchart of Hollow Cylindrical [19].

3.2. Testing Equipment

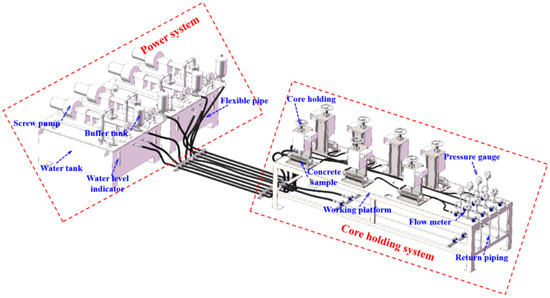

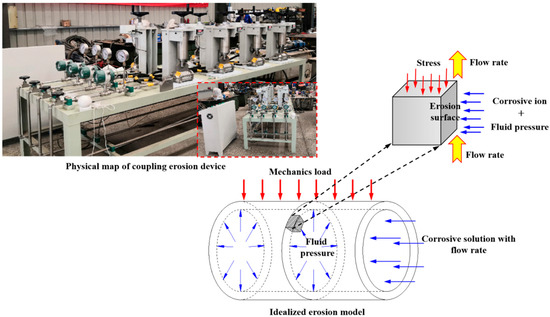

A custom-built stress–seepage–chemical (SSC) coupling apparatus was employed to erode hollow cylindrical concrete specimens under combined mechanical and chemical actions [19,20]. The schematic layout of the apparatus is given in Figure 2. Axial loading (0~20 kN) is applied to the specimen via a core gripper, while the circulation unit delivers aggressive solutions (sulfate, chloride or carbonate) at controlled flow rates (0~1.2 m3/h) and fluid pressures (0~1.2 MPa). The operating of the SSC erosion experiments is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the coupled erosion test setup [20].

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of coupled stress–seepage–chemical erosion [20].

3.3. Calibration and Measurement Uncertainty Analysis

3.3.1. Axial Loading System

The axial loading mechanism was calibrated using a reference load sensor (HBM S9, 50 kN range) traceable to national standards. Within the operating range (0–20 kN), linear regression between the applied and measured loads yielded an R2 value of 0.9998. Hysteresis tests indicated a maximum nonlinearity of 0.3%. Taking into account calibration uncertainty, temperature effects, and long-term stability, the combined standard uncertainty in load measurement was determined to be ±0.6%.

3.3.2. Pore Pressure Measurement

The pressure transducer (WIKA S-10, 0–2 MPa range) was calibrated against a dead-weight tester (Desgranges & Huot 5200S) with a certified accuracy of ±0.05% of reading. Over the calibration cycle, the maximum deviation observed was 0.12% FS. Temperature compensation was applied per the manufacturer’s specifications, contributing ±0.1% to the measurement uncertainty.

3.3.3. Flow Measurement System

The electromagnetic flowmeter (Krohne Waterflux 3070) was calibrated gravimetrically in accordance with ISO 4185. The calibration covered a flow rate range of 0.1–1.2 m3/h, corresponding to flow velocities of 0.08–1.0 m/s in our test setup. When accounting for calibration uncertainty, temperature variations, and installation effects, the expanded uncertainty (k = 2) in flow velocity was determined to be ±1.6%.

3.3.4. Evaluation of the Combined Uncertainty

Based on the JCGM 100:2008 guideline, the overall uncertainty in determining the erosion rate was evaluated using the root sum of squares method. The primary uncertainty components were as follows:

Flow velocity measurement: ±1.6%, axial load application: ±1.2%, dimensional measurement: ±0.8%, and time measurement: ±0.5%. The combined expanded uncertainty (with a coverage factor k = 2) in the reported erosion rate was determined to be ±2.1%, which confirms the reliability of our quantitative findings.

4. Test Scheme and Test Method

This study investigates the spatio-temporal degradation of immersed-tunnel concrete exposed to Tanzhou waterway water under varied stress levels. Hollow cylindrical specimens were first subjected to coupled stress–seepage–chemical attack in a custom-designed apparatus. Spatially resolved micro-indentation was then employed to map post-erosion mechanical properties and to quantify the degradation gradient. Subsequently, X-ray diffraction and scanning electron microscopy were used to characterize the altered mineralogy and microstructure, thereby elucidating the degradation mechanisms induced by the inland river environment.

4.1. Test Scheme

For the coupled stress–seepage–chemical attack on hollow cylindrical concrete, the key variables are the ionic composition and hydrostatic pressure of the aggressive solution, the axial load, and the flow rate. The solution was taken from the Tanzhou waterway at the Lungui Road immersed-tunnel alignment; its ionic composition is listed in Table 2. A hydrostatic pressure of 0.25 MPa was adopted, equivalent to the centennial-maximum flood pressure on the tunnel invert. The study focuses on load-dependent degradation of mechanical properties. Three axial-load levels 1.593 kN, 2.656 kN and 3.718 kN were selected, corresponding to 30% 50% and 70% of the ultimate compressive strength under 0.25 MPa internal pressure. The flow velocity was fixed at 0.5 m s−1, representing the median of the 0–1.0 m/s−1 range observed in the Tanzhou waterway. Details of the test matrix are given in Table 3.

Table 2.

Composition of Erosive Ions in Tanzhou Waterway River Water.

Table 3.

Working Conditions for Erosion Tests.

4.2. Test Method

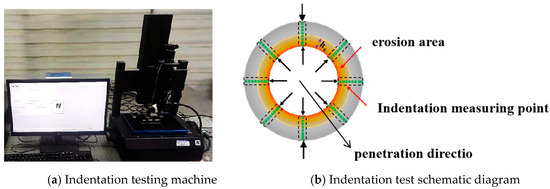

4.2.1. Millimeter Indentation Test Method

Sample Preparation

Following the coupled erosion tests, a sector-shaped specimen containing the eroded surface was radially sectioned from the hollow cylindrical concrete sample. The specimen was then mounted in cold-curing epoxy resin to ensure stability during testing. To obtain a flat, smooth surface suitable for microindentation testing, the mounted specimen was subjected to a multi-step mechanical polishing procedure: sequential polishing with diamond abrasives having grit sizes of 30 μm, 15 μm, 6.5 μm, and finally 1 μm. This process yielded an optically flat surface finish with a roughness (Ra) of less than 0.1 μm. The prepared sample was stored in a desiccator for at least 24 h prior to testing.

Test Procedure and Parameters

Indentation tests were conducted at ambient temperature. Indentation points were arranged along the radial direction of the specimen in a single-row grid starting from the erosion surface outward, with a spacing of 500 μm between points—sufficient to prevent interference from adjacent stress fields. At each radial depth, at least five valid indentations were performed, and their average value was taken as the representative elastic modulus at that depth to ensure statistical reliability.

A load-controlled protocol was applied as follows: loading at a rate of 0.04 mm/min to a maximum load of 200 N, holding at the peak load for 30 s to minimize creep effects on the unloading curve, and then unloading at the same rate. The mechanical properties (elastic modulus) were determined by analyzing the load–displacement data during unloading using the Oliver–Pharr method [21].

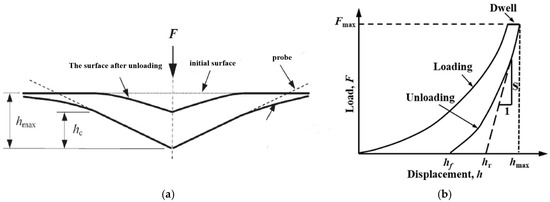

The degree of degradation in the eroded concrete was quantified by micro-indentation. Mechanical properties were extracted from the load displacement curves (Figure 4) using the Oliver–Pharr method [21]. The unloading segment was fitted with a power-law function, as defined in Equation (1):

where F is the applied load; h is the indentation depth hf is the final indentation depth; m is the fitting parameter.

Figure 4.

Schematic Diagram of Micro-Indentation Testing Principle [20]. (a) Indentation test loading and unloading deformation process diagram; (b) Load–displacement curve of indentation test.

Here, the contact depth, hc, can be expressed as

which

In Equation (1), hmax denotes the maximum indentation depth, hr is the intercept of the unloading tangent at peak load with the depth axis, and ε(m) accounts for indenter geometry and material plasticity.

The projected contact area, Ac, is subsequently computed from the contact depth hc.

The contact stiffness, S, is taken as the slope of the initial portion of the unloading curve at hmax.

Further, the reduced modulus, Er, can be calculated using Formula (6) to obtain

During indentation, both the indenter and the concrete specimen undergo elastic deformation; the elastic modulus of the specimen is then evaluated using Equation (7).

In Equation (7), E and denote the elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio of the concrete, respectively. For the diamond indenter, Er = 1.141 GPa and r = 0.07. The literature data indicate that variations in Poisson’s ratio exert negligible influence on the computed elastic modulus [20]. Consequently, a fixed value of = 0.21 is adopted for both eroded and uneroded specimens.

Prior to indentation, the maximum load and loading rate were calibrated to ensure agreement with macroscopic mechanical tests. Following a preliminary series, a peak load of 200 N and a loading rate of 0.04 mm/min−1 were adopted.

Indentations were performed along a diameter from the inner to the outer surface of the hollow cylinder (Figure 5). At each radial depth, three indents were averaged to yield the local mechanical parameter, giving the radial profile. Erosion depth (h) was identified as the radial location where the modulus recovered to the initial value. Coordinates and elastic modulus of every indent were recorded to construct modulus-position curves. These curves reveal the spatio-temporal evolution of local mechanical degradation. The deterioration rate v is defined as v = h/t.

Figure 5.

Schematic Diagram of Concrete Performance Deterioration in Indentation Tests.

4.2.2. Mineral Analysis and Electron Microscope Scanning Analysis Methods

Post-indentation concrete cubes (10 mm × 10 mm × 10 mm) were sectioned by wire-cut electrical-discharge machining for SEM imaging. Imaging was performed with a ZEISS GeminiSEM 300 (Germany). Cement mortar was isolated by removing coarse aggregate, ground to pass a 200-mesh sieve, and analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD). Diffraction patterns were collected on a Rigaku ULTIMA IV powder diffractometer.

5. Experimental Result

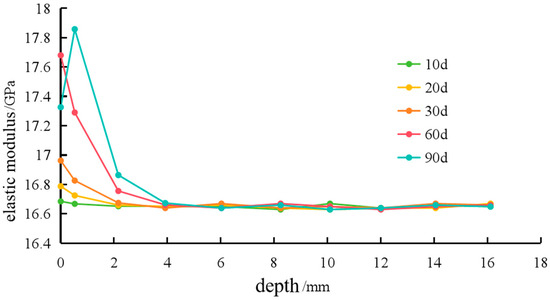

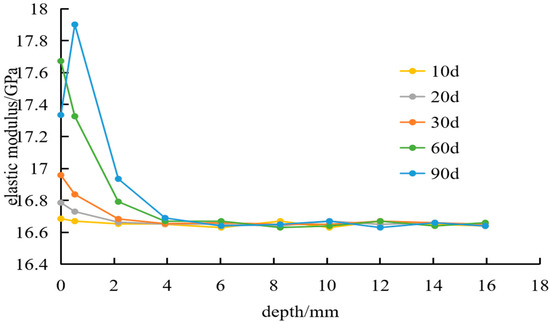

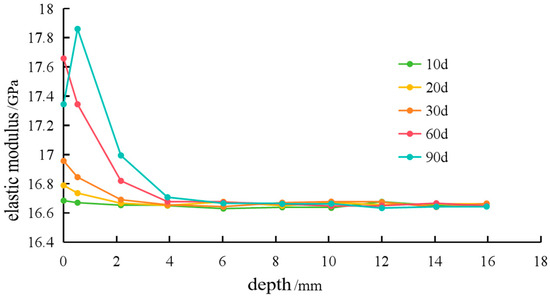

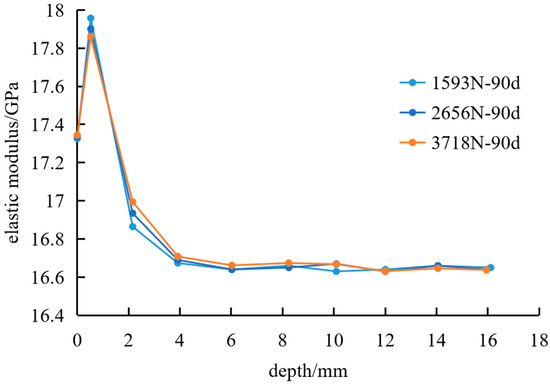

Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 present the distribution of elastic modulus in the cement mortar of concrete along the erosion direction after exposure to naturally concentrated water from the Tanzhou Waterway under different applied load levels. During the initial 0–60-day period, the elastic modulus at the erosion surface increased from the initial value of 16.65 GPa to peak values of 17.68 GPa (under 1.593 kN), 17.67 GPa (under 2.656 kN), and 17.66 GPa (under 3.718 kN), corresponding to increases of 6.2%, 6.1%, and 6.1%, respectively. By 90 days, the values for all specimens had decreased to 17.33 GPa, 17.34 GPa, and 17.35 GPa, respectively, resulting in net increases of 4.1%, 4.1%, and 4.2% relative to the initial state.

Figure 6.

Distribution of Elastic Modulus in Cement Mortar Along Erosion Direction Under 1.593 kN Load.

Figure 7.

Distribution of Elastic Modulus in Cement Mortar Along Erosion Direction Under 2.656 kN Load.

Figure 8.

Distribution of Elastic Modulus in Cement Mortar Along Erosion Direction Under 3.718 kN Load.

Figure 9 further compares the elastic modulus distributions after 90 days of erosion under different loading conditions. The results show a maximum inter-condition variation in merely 0.019 GPa. In summary, the experimental findings in this section reveal two core phenomena: (1) the elastic modulus of concrete exhibits a non-monotonic evolution during the erosion process, characterized by an initial increase followed by a decrease; and (2) although the applied load has a negligible effect on the peak modulus at the erosion surface, it significantly enlarges the affected zone where the elastic modulus changes and accelerates the erosion rate. The following discussion will focus on the underlying mechanisms responsible for these two phenomena.

Figure 9.

Elastic Modulus Distribution in Cement Mortar Along Erosion Direction Under Different Loads.

6. Results Analysis and Discussion

6.1. Deterioration Mechanism of Mechanical Properties of Concrete Under Stress-Seepage-Chemical Multi-Field Coupling Effect

Based on the experimental results presented in Section 5, this section aims to provide an in-depth analysis of the degradation mechanisms of concrete under the coupled effects of stress, seepage, and chemistry. The study revealed varying degrees of enhancement and weakening in the mechanical properties of the concrete matrix. This phenomenon is mainly attributed to chemical reactions between the aggressive ions in the solution and the concrete hydrates.

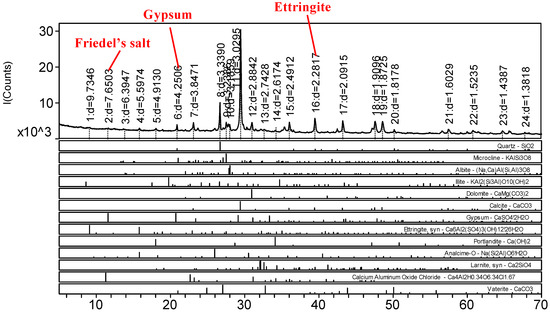

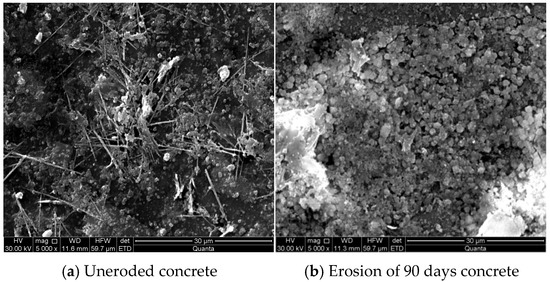

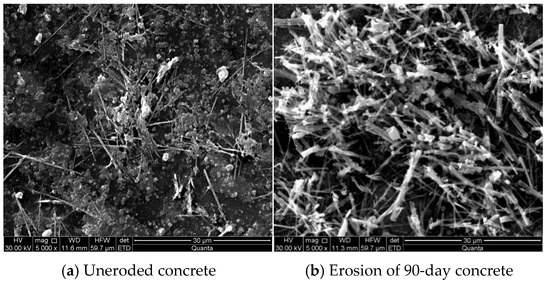

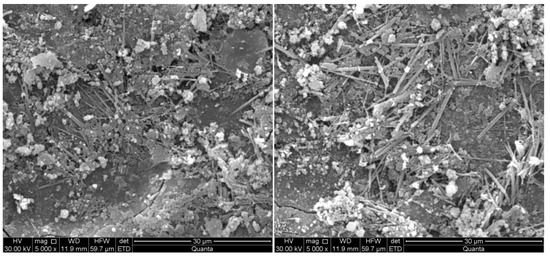

XRD patterns (Figure 10) reveal secondary phases-gypsum, ettringite and Friedel’s salt-formed after exposure to Tanzhou-waterway water. Sulfate (250 mg/L−1) reacts with portlandite to precipitate gypsum, accompanied by a 1.24-fold volume increase [19,20,22]. Columnar gypsum is observed by SEM (Figure 11). This phase was also identified via scanning electron microscopy, as clearly shown in Figure 11b and Figure 12b, where typical clusters of stubby gypsum crystals and needle-like ettringite crystals are distinctly visible, respectively. These morphological observations are consistent with the phase composition results obtained from XRD analysis (Figure 10), collectively confirming the occurrence of the aforementioned chemical reactions and the specific morphology of their resulting products. After 90 d, the gypsum content is significantly higher than in the reference (uneroded) specimen. Subsequently, gypsum reacts with calcium aluminate phases (C3A, C4A, and C4AsH12) to yield insoluble ettringite. Needle-like ettringite is detected by SEM (Figure 12). Ettringite formation is accompanied by water uptake and a 2.5-fold volume expansion [19,20,22]. SEM confirms that ettringite abundance exceeds that in the reference specimen. Initially, ettringite densifies the matrix and transiently increases the modulus. Once pore volume is exceeded, expansion-induced microcracking ensues. As can be observed in Figure 13, the cracks formed in concrete after 90 days of erosion are filled with substantial amounts of ettringite and minor quantities of gypsum crystals. This image provides direct microstructural evidence supporting the proposed mechanism: the formation and accumulation of these reaction products within pores generate crystallization pressure due to their volumetric expansion. This pressure, in turn, initiates and propagates microcracks, ultimately leading to the degradation of mechanical properties. This assemblage damages the matrix and reduces mechanical performance. Minor Friedel’s salt is also detected, originating from the reaction of pore Ca2+ and chloride with calcium aluminate phases to yield plate-like crystals. This phase is sparingly soluble. Its progressive accumulation in pores promotes crack propagation.

Figure 10.

Mineral Composition Analysis of Eroded Concrete.

Figure 11.

Formation of Gypsum Crystals in Eroded Concrete.

Figure 12.

Formation of Ettringite Crystals in Eroded Concrete.

Figure 13.

Distribution of Ettringite and Gypsum infilling within Cracks in Concrete.

In summary, the short-term formation of gypsum, ettringite, and Friedel’s salt effectively densifies the concrete matrix by filling pores, thereby enhancing its mechanical properties. Accordingly, the observed 6.2% increase in surface modulus during the initial 60 days corresponds to the pore-filling stage, whereas the subsequent decrease of 1.9–2.0% between 60 and 90 days indicates the initiation of microcracking induced by crystallization pressure (Figure 13). This microstructural damage ultimately leads to the degradation of the concrete matrix and its mechanical performance. As a result, under various loading conditions, the elastic modulus of concrete shows a declining trend after 90 days of erosion. With prolonged exposure, the elastic modulus will continue to decrease and may eventually fall below that of non-eroded concrete. Beyond this point, erosion by the Tanzhou Waterway begins to exert a detrimental effect on the mechanical performance of the immersed tunnel.

6.2. The Influence Law and Mechanism of Load on the Mechanical Properties of Concrete

Based on the foregoing analysis, it can be concluded that the increase in load exerts a negligible influence on the elastic modulus of concrete in the vicinity of the water-soil erosion zone. Consequently, a quantitative investigation was conducted to elucidate the scope of impact and the evolution of the erosion rate on the concrete’s elastic modulus, induced by river water from the Tanzhou Waterway, under varying loading conditions.

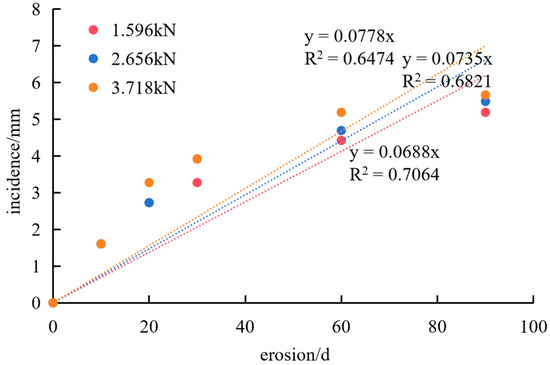

Figure 14 shows that the erosion depth increases linearly with time (10–90 d) under 1.596 kN, 2.656 kN and 3.718 kN, rising from an initial 1.605 mm to 5.186 mm, 5.483 mm and 5.661 mm, respectively. The corresponding erosion rates are 0.0688, 0.0735 and 0.0778 mm d−1. Regression analysis indicates a significant positive correlation between load and erosion metrics: a load increase from 1.596 kN to 3.718 kN enlarges the final erosion depth by 9.2% and raises the rate by 13.1%. Thus, higher water-soil loads accelerate the erosion process.

Figure 14.

Evolution of Influence Range of Elastic Modulus Changes with Erosion Duration Under Different Loads.

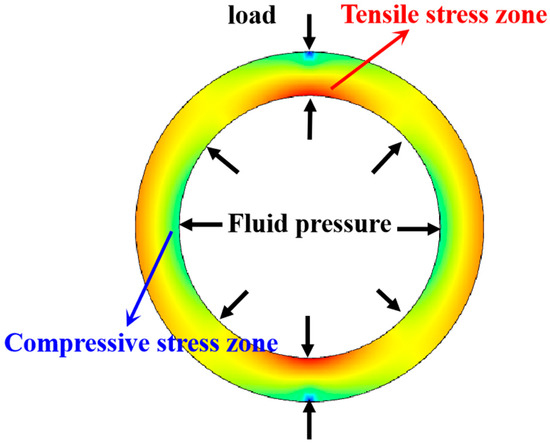

This behavior is attributed to the heterogeneous stress field within the concrete. Under combined vertical load and internal water pressure, the inner ring of the hollow cylinder experiences tension at its vertical poles and compression at its horizontal poles (Figure 15). The outer ring exhibits the reverse pattern: compression vertically and tension horizontally. Literature data indicate that tensile stress enhances sulfate ingress and accelerates matrix degradation, thereby increasing damage. Consequently, higher water-soil loads enlarge both the tensile zone and its magnitude, extending sulfate penetration and expanding the affected depth.

Figure 15.

Schematic Diagram of Stress Distribution in Concrete under Combined Loading and Hydrostatic Pressure.

To quantify the load-induced acceleration of erosion, a load-acceleration erosion coefficient, defined as the normalized rate increment, is given in Equation (8).

In Equation (8), ξ denotes the load-acceleration coefficient; V3.718, V2.656 and V1.596 are the erosion rates at 3.718, 2.656 and 1.596 kN, respectively. In this paper, V1.596 = 0.0668 mm/d, V2.656 = 0.0735 mm/d, V3.718 = 0.0778 mm/d.

Rate ratios quantify the acceleration: 1.058 (3.718 vs. 2.656 kN), 1.100 (2.656 vs. 1.596 kN) and 1.165 (3.718 vs. 1.596 kN). These values define a monotonic load–acceleration relationship:ξrises from 1.100 to 1.165 as the load increases from 1.596 kN to 3.718 kN.The derived coefficients furnish key input for service-life models of hydraulic concrete subjected to coupled sulfate attack and mechanical load, enabling long-term degradation forecasts from short-term laboratory data.

7. Conclusions

This study investigated the degradation mechanisms of concrete in immersed inland tunnels under multi-field coupling of stress, seepage, and chemistry—a scenario often oversimplified in previous research. The novelty of this work lies in its application of microindentation to quantitatively characterize the spatio-temporal evolution of local mechanical properties, providing new insights into the coupled effects of mechanical loading and chemical erosion:

- (1)

- Under inland water erosion, the mechanical properties of concrete exhibit a distinct “first strengthen, then weaken” trend. This is attributed to the dual role of reaction products (gypsum, ettringite, and Friedel’s salt): initially filling pores and enhancing performance, but eventually inducing microcracking and damage when their formation exceeds the pore capacity.

- (2)

- Increasing the hydrostatic load had a negligible influence on the peak elastic modulus at the erosion surface (maximum variation in only 0.019 GPa), yet it significantly accelerated the erosion process and expanded the affected zone. Specifically, as the load increased from 1.596 kN to 3.718 kN, the depth over which the elastic modulus changed expanded by 9.2%, from 5.186 mm to 5.661 mm.

- (3)

- To quantify this acceleration effect, a load acceleration factor for erosion was proposed, which ranged from 1.100 to 1.165 under the studied load levels. This factor provides a key parameter for utilizing laboratory accelerated tests to predict the long-term durability of concrete structures under similar service conditions.

The study has certain limitations. The tests were conducted in an accelerated laboratory environment with specific solution composition and loading configuration, which may not fully capture the long-term temporal complexity and heterogeneity of real field conditions. Future work should focus on validating the proposed acceleration model against long-term field exposure data and exploring concrete degradation under more complex multi-ionic interactions and dynamic loading conditions.

Author Contributions

Data curation, Y.L.; Writing—original draft, Q.W. and Z.Z.; Writing—review and editing, G.Z.; Supervision, F.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Qixian Wu was employed by the Shunde District construction project center. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, W.; He, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, G.; Hu, H.; Deng, H. Exploration and Innovation of Inland Immersed Tunnel Engineering Supervision—Taking Nanchang Honggu Tunnel Project as an Example. Constr. Superv. 2025, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Mao, H.; Tuo, Y.; Gao, W. Overall design of Foshan super-large section river immersed tunnel project. Mod. Tunn. Technol. 2024, 61, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, G.; Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Sun, X.; Feng, X.; Ren, Y.; Xu, Y. Key new technology for the construction of large immersed tunnel in the middle reaches of the Inland River-Taking Xiangyang Yuliangzhou Tunnel as an example. Tunn. Constr. 2024, 44, 810–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R. Study on the Space-Time Deterioration Law of Concrete Under Stress-Chemical-Hydraulic Coupling Erosion. Master’s Thesis, Hubei University of Technology, Wuhan, China, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zou, Y.; Hu, D.; Zhou, H.; Wang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z. Spatiotemporal deterioration of concrete under high osmotic pressure and sulfate attack. J. Zhejiang Univ. 2021, 55, 539–547. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; Dong, H.; Wang, R.; Su, Y. Multi-ionic transport in concrete under chemical equilibrium. Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 132, 106053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhang, C.; Liu, D.; Tu, J.; Yan, Q.; Fang, Y.; He, C. The effect of cross-sectional shape on the dynamic response of tunnels under train induced vibration loads. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 89, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, W.; Mu, S.; Branko, S.; Liu, Q. Effect of bicarbonate ions on corrosion of reinforcing steel and durability of concrete in sulfate-carbonate environments. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 347, 128566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H. Study on the resistance to chloride ion erosion of bulk hydrophobic concrete. ConcreteWorld 2025, 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Bai, P.; Zhao, H.; Yang, Q.; Bao, C. Effect of water-cement ratio and chloride concentration on compressive strength of concrete under coupled chloride-sulfate attack. Sichuan Cem. 2025, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, K.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, Y.; Hu, J.; Shi, C. Flexural behavior of slag-based geopolymer concrete beams under load-chloride erosion coupling. Mater. Rep. 2025, 39, 117–123. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z. Effect of physical and chemical sulfate attack on performance degradation of concrete under different conditions. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2020, 745, 137254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Z.; Lu, Z. Effect of sulfate solution concentration on the deterioration mechanism and physical properties of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 227, 116641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Li, J.; Zhao, G.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, P. Experimental investigations on the durability and degradation mechanism of cast-in-situ recycled aggregate concrete under chemical sulfate attack. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 297, 123771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Yao, J.; Luo, Y.; Gui, F. A chemical-mechanics model for the mechanics deterioration of pervious concrete subjected to sulfate attack. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 312, 125383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Li, J.; Shi, M.; Fan, H.; Cui, J.; Xie, F. Degradation mechanisms of cast-in-situ concrete subjected to internal-external combined sulfate attack. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 248, 118683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Li, W. Study on foundation settlement control technology of super-wide inland river immersed tunnel. Highway 2024, 69, 458–465. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.1668.U.20241210.0847.136 (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Guangdong Provincial Department of Water Resources. Guangdong Provincial Water Resources Bulletin 2024. Available online: https://www.yuntaigo.com/book.action?recordid=bmJvb29sYmM5Nzg3NTIyNjM0MjU4 (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Yang, F.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Song, J.; Hu, D.; Zhou, H. Effect of flow rate on spatio-temporal deterioration of concrete under flowing sulfate attack. Cem. Concr. Res. 2025, 188, 107734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Li, R.; Hu, D.; Iqbal, S.M.; Zhou, H.; Guo, F. A novel test method for characterizing tempo-spatial variations in elastic modulus of underwater concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76, 107096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, W.C.; Pharr, G.M. An improved technique for determining hardness and elastic madulus using load and displacement. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 1992, 7, 1564–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Song, J.; Hu, D.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, Y. A new approach for characterizing concrete deterioration under sulfate attack and its application: Insights from elastic modulus variation using indentation technology. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 107096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.