Abstract

Construction safety remains a critical concern, with frequent accidents leading to fatalities, severe injuries, and significant economic losses. To address these challenges and enhance accident prevention, this study adopts a systems thinking approach to investigate the causal factors of construction safety accidents. First, drawing on Rasmussen’s risk management framework, this study developed a Construction Accident Causation System (CACS) model that comprises six hierarchical levels and 23 influencing factors. Through the analysis of 331 investigation reports of construction accidents in China, causal factor correlations were refined, and the topological structure and network parameters of the model were determined. This study integrates diagnostic reasoning, sensitivity analysis, and fuzzy mathematics within a Bayesian Network (BN) framework. Through this approach, it identifies the most probable accident pathways and highlights seven critical and three sensitive factors that jointly exacerbate construction safety risks. A real-world case of a formwork collapse in Baotou City is further analyzed to verify the model’s reliability and practical relevance. The results confirm that the integrated CACS and BN framework effectively captures the multi-level interactions among managerial, behavioral, and technical factors, providing a scientific basis for proactive safety management and accident prevention in the construction industry.

1. Introduction

The construction industry employs about 7% of the global workforce, yet fatalities in this sector account for 30–40% of the total, making it one of the most hazardous industries worldwide [1,2,3]. According to the Ministry of Emergency Management of China (MEM), in the first three quarters of 2024, a total of 14,402 safety accidents occurred nationwide, resulting in 13,412 deaths, representing a year-on-year decrease of 24.5% and 18.4%, respectively [4]. Among these, both the number of accidents and fatalities in the construction sector declined compared to the previous year. Data from the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of China (MHURDC) indicated that in 2021, 730 production safety accidents occurred in housing and municipal engineering projects nationwide, causing 815 casualties [5]. Taking Hubei Province as an example, in 2024, the construction industry (including housing, municipal engineering, and railway construction) experienced 84 accidents, resulting in 89 deaths, representing year-on-year decreases of 19.2% and 22.6%, respectively [6]. Overall, although the safety situation in the construction industry has improved, the total number of accidents remains high, and the safety management situation remains severe. The frequent occurrence of construction accidents not only leads to substantial economic losses but also poses significant threats to workers’ lives and social stability, as shown in Figure 1. Therefore, exploring the underlying factors leading to accidents is crucial for effective risk management and prevention.

Figure 1.

Real-life scenes of multiple construction safety incidents.

Major incidents reveal that construction accidents seldom result from a single cause. Instead, they usually emerge from complex interactions among human, organizational, and technical factors [7,8]. For example, the 2023 Qiqihar gymnasium roof collapse and the 2022 Anyang factory fire both stemmed from chains of interrelated failures in design, supervision, and emergency response. These cases illustrate that accident causation is nonlinear and systemic, involving multiple interdependent dimensions such as organizational behavior, technology management, resource assurance, contract management, safety training, and environmental control. However, existing research and management practices often fail to capture this complexity. Many safety management methods, including qualitative risk assessments [9], checklist-based evaluations [10], and expert judgments [11], focus on isolated factors and depend heavily on subjective assessments. As a result, they cannot adequately reveal how different risk elements interact within the construction system [12].

Although systems-based approaches such as Fuzzy Cognitive Maps (FCM) [13] and the Decision-Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory (DEMATEL) [14] have been introduced to capture causal interactions, their ability to model the full complexity of construction systems remains limited. They cannot integrate multi-layered causal relationships that span human, organizational, and technical domains, and their dependence on expert-assigned weights introduces subjectivity. Furthermore, they lack probabilistic inference mechanisms capable of representing uncertainty or predicting accident pathways.

Consequently, a critical research gap remains. As highlighted in a recent 2025 review by Zang et al. [15], purely qualitative models struggle to handle the complexity of modern construction data, while Medaa et al. [16] further emphasize that the future of safety analysis lies in the integration of deterministic and probabilistic methods. Against this backdrop, existing studies have yet to establish a unified, data-driven framework that systematically identifies, structures, and quantifies the multi-level causal mechanisms of construction accidents within a systems-thinking perspective. This gap defines the central research problem of this study: how to integrate qualitative system modeling with quantitative probabilistic reasoning to uncover interdependencies among multi-level risk factors and improve the reliability of accident diagnosis and prediction.

To address this problem, this study combines the AcciMap model and Bayesian Network (BN) analysis into a coherent framework for accident causation modeling. The AcciMap model, grounded in Rasmussen’s risk management theory, allows for the structured representation of socio-technical interactions across multiple levels [8,17]. The BN complements this by introducing probabilistic reasoning, enabling quantitative inference under uncertainty [18]. The integration of these two approaches not only bridges the gap between qualitative and quantitative paradigms but also establishes a methodological foundation for data-driven, systems-based safety analysis in the construction industry.

Previous BN-AcciMap or BN-STAMP studies predominantly rely on small, expert-dependent datasets and offer little guidance on mapping system-theoretic models to BN structures. In contrast, this study adopts a more scalable and reproducible approach. It leverages 331 official accident reports, establishes an operational AcciMap-to-BN mapping workflow, and incorporates EM learning with fuzzy-based diagnostic reasoning to improve both interpretability and key pathway identification. The main innovations and contributions of this research are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- Focusing on fall from height, structural collapse, lifting injuries, and other construction safety accidents, the study constructs a Construction Accident Causation System (CACS) model across six dimensions. 11The model establishes six hierarchical levels and twenty-three interrelated factors to represent the multi-level nature of accident causation.

- (2)

- It develops a BN-based quantitative framework that transforms the qualitative CACS structure into a probabilistic reasoning model. This enables diagnostic inference, sensitivity analysis, and the quantitative identification of key accident pathways based on 331 official construction accident reports.

- (3)

- It validates the proposed approach through real-world collapse case studies, demonstrating both its theoretical contribution to understanding causal mechanisms and its practical value for data-informed decision-making in construction safety management.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Foundations of Construction Accident Causation

The theory of accident causation forms the foundation of safety research and guides the development of prevention strategies in construction management [7]. Early studies adopted linear models such as the Domino Model. This framework conceptualizes accidents as sequential events triggered by unsafe acts or conditions. While these models clarified direct causes and promoted behavioral safety practices, they overlook the dynamic nature of construction projects, where multiple human, organizational, and environmental factors interact continuously. As Salmon and Lenné [19] noted, accident causation in real projects is rarely linear but shaped by complex feedback and interdependencies. The introduction of system analysis represented a major theoretical shift. Models such as Rasmussen’s Risk Management Framework and the AcciMap Model [17,20], the Swiss Cheese Model [21], and the System-Theoretic Accident Model and Processes (STAMP) by Leveson [22] began to view safety as an emergent property of socio-technical systems. In recent years, additional system-based methods such as the Functional Resonance Analysis Method (FRAM) have been applied to construction activities to capture performance variability and functional interactions, particularly in complex operations such as concrete structure construction [23]. These approaches further demonstrate the value of modeling coupled interactions rather than linear chains of events.

By contrast, the AcciMap Model provides a multi-level representation of causal interactions, spanning government regulation to site-level behavior, which aligns better with the decentralized structure of construction projects [8]. Empirical applications have confirmed its explanatory potential: Ros et al. [24] demonstrated its ability to reveal cross-level dependencies, while Junjia et al. [25] used it to trace risk propagation in hoisting operations. However, most studies remain descriptive, relying on expert judgment rather than empirical validation. The approach captures structural complexity but fails to quantify the strength of relationships or model their probabilistic dependencies, limiting predictive and diagnostic capacity. These limitations reveal a persistent methodological gap. Existing systems-based models provide conceptual insight but lack the quantitative rigor required for dynamic and data-rich construction settings. Combining systems thinking with probabilistic modeling, such as BN, can help bridge this gap by linking structural understanding with data-based reasoning in construction safety research. This conceptual foundation directly informs the analytical framework developed in the following sections.

2.2. Critical Influencing Factors of Construction Safety

A large body of research has explored the causes of construction accidents, but these studies remain fragmented and lack an integrated system perspective. Construction projects are dynamic, and risk factors rarely act alone. Hinze et al. [26] emphasized that identifying the sources of accidents is the foundation of prevention, yet most subsequent research has treated human, organizational, and technical variables as separate rather than interrelated elements of a complex system. Human-centered studies have long dominated the field. Choudhry and Fang [27] identified poor hazard awareness, inadequate training, and failure to follow procedures as key causes of unsafe behavior, while Hoła and Szóstak [28] linked worker characteristics and task preparedness to accident frequency. More recent research has further highlighted psychological and motivational aspects, showing that construction safety culture and safety climate significantly influence workers’ safety behavior and safety motivation on site [29]. Although these studies provide valuable insights into behavioral risks, they often assume that accidents result mainly from individual negligence.

Research focusing on organizational and technical aspects offers a complementary but equally partial perspective. Kazan and Usmen [30] found that inadequate maintenance and lack of protective systems significantly affect injury severity, and Sanni-Anibire et al. [31] demonstrated that poor coordination, material delays, and financial difficulties undermine safety performance. Studies on safety leadership and participation have expanded this view by demonstrating how managerial practices and participatory structures shape frontline safety outcomes. Qualitative evidence shows that direct and indirect safety leadership practices of construction site managers can either promote or impede safe performance on site [32]. Longitudinal research further indicates that safety role-modeling by leaders has sustained effects on workers’ risk-taking, communication, and safety-related behaviors [33]. In parallel, research on construction safety culture and climate has identified the relative importance of contributing factors and clarified how supportive participation and safety climate structures are essential for resilient and safe construction projects [33,34]. Even integrative works, such as Muñoz-La Rivera et al. [35] and Lu et al. [36], which categorize extensive risk factors, stop short of modeling interactions among variables. Overall, existing research provides extensive knowledge of what factors matter but a limited understanding of how these factors interact across system levels to produce accidents. To fill this gap, this study develops a Construction Accident Causation System (CACS) model and applies BN analysis to quantify interdependencies among multi-level factors in construction safety.

2.3. Safety Management and Monitoring Tools in Construction

Effective safety management requires not only identifying accident causes but also monitoring dynamic risks during project execution. Traditional tools, such as manual inspections, checklists, and compliance audits, serve as the foundation of construction safety management but remain largely reactive. They detect hazards only after they have emerged and struggle to reflect the complex interactions among workers, technology, and organizational processes. Quantitative methods, including descriptive statistics and regression analysis, provide useful trend analyses but rely on static assumptions and are insufficient for capturing nonlinear, system-level relationships. To overcome these limitations, systems-based analytical methods have been introduced to model interdependencies more explicitly. Fuzzy Cognitive Maps (FCM), as applied by Skład [37], use expert-derived weights to visualize causal relationships among factors, while Hatefi et al. [38] employed the DEMATEL technique to reveal factor interrelations and feedback loops. Although these methods represent an important shift toward structural modeling, they remain highly dependent on subjective judgment and lack probabilistic rigor, limiting their predictive and diagnostic capabilities.

Table 1 compares representative studies employing BN, AcciMap, and other systems-thinking approaches. As summarized, while systems-based models offer structural depth, they often lack the quantitative rigor to model probabilistic dependencies. Conversely, pure BN applications frequently rely on researcher-defined structures rather than systematic causal frameworks. This study addresses this gap by integrating the systemic structural insights of the AcciMap model with the probabilistic reasoning capabilities of BN. By leveraging the Expectation–Maximization (EM) algorithm to learn parameters from 331 official accident reports, the proposed framework establishes a data-driven approach that objectively quantifies multi-level causal mechanisms and identifies critical risk pathways.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of existing BN, AcciMap, and systems-thinking research.

3. Research Methodology

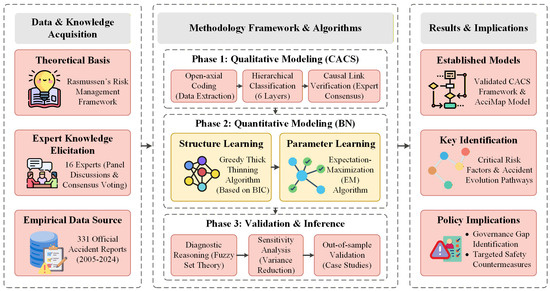

To address the complexity and uncertainty of construction safety accidents, this study adopts an integrated approach combining AcciMap and BN methods. The AcciMap, grounded in systems thinking, reveals complex interactions across multiple levels, while the BN quantifies causal relationships and extracts accident pathways from empirical data. By integrating AcciMap’s structural insights with BN’s probabilistic inference, this framework transforms qualitative causal maps into a quantitative diagnostic model, reducing the reliance on subjective bias.

This study primarily utilized construction accident investigation reports as its core data source, supported by limited expert validation to refine causal relationships. The approach does not rely solely on expert scoring, but transforms factual accident data into a structured knowledge base. By combining systems thinking, BN, and case study methodologies, we systematically identified causal factors and their interdependencies, quantified probabilistic relationships, and explored critical accident pathways and key influencing factors through diagnostic reasoning and sensitivity analysis. Moreover, the applicability of this model was further validated using real-world case studies. Figure 2 illustrates this integrated process, which spans from system decomposition to quantitative modeling and empirical validation, offering a robust, data-driven framework for construction safety management. Thus, the framework is empirically informed rather than purely expert-driven, allowing objective inference from real accident evidence.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the proposed methodology.

- Establishment of the CACS and AcciMap model. The Construction Accident Causation System (CACS) model was developed using a systems-thinking approach, which regards construction safety accidents and their causal factors as an integrated system that can be decomposed into multiple hierarchical levels and interacting factors [41]. To construct this model, a comprehensive literature review was first conducted, identifying 23 key causal factors, which were categorized into six levels: Organizational and Behavioral (OB), Technical Management (TM), Resource Guarantee (RG), Contract Management (CM), Safety Training (ST), and Environmental Management (EM). These levels were adapted from Rasmussen’s risk management framework, tailored to the characteristics of the construction industry to comprehensively capture accident causation. To clearly depict the causal relationships among these factors, the study further developed an AcciMap model, graphically representing dynamic interactions within and across levels. Additionally, a team of 16 experts was assembled, and through multiple rounds of collaborative discussions, the causal relationships were validated and refined. The resulting AcciMap provides a qualitative systemic framework for understanding accident causation, laying a solid foundation for subsequent quantitative analysis using BN.

- Establishment of the BN model and BN analysis. The BN model builds upon the qualitative analysis of AcciMap, quantifying the relationships between causal factors within a probabilistic framework by converting the factors and their interactions described in AcciMap into nodes and arcs [40]. Following frequency statistics of construction accident investigation reports and expert discussions, two low-frequency factors were excluded, resulting in the construction of a network comprising 22 nodes (21 CACS factors plus one accident node). The expert-validated causal relationships from AcciMap were integrated, and the network structure was further refined using the Greedy Thick Thinning algorithm and empirical data-driven adjustments in GeNIe 2.3 (BayesFusion, LLC, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) software, ensuring alignment with both expert knowledge and real-world data characteristics. Next, the Expectation–Maximization (EM) algorithm was employed to generate Conditional Probability Tables (CPTs) from the accident report data, precisely capturing probabilistic dependencies between nodes. BN analysis was conducted in two parts: diagnostic reasoning to trace critical pathways leading to accidents, and sensitivity analysis to identify key influencing factors. This approach not only enhances the model’s inferential capabilities but also reduces reliance on subjective judgment by grounding the analysis in empirical data, thereby improving objectivity and credibility.

- Case study of a collapse accident. Case studies are an effective method for validating research findings [42]. To assess the practical utility of the CACS model and the key factors identified by the BN approach, this study selected the Hengshui City construction hoist cage collapse accident as a case study. By analyzing the accident process and official investigation findings, the causes were extracted and compared with the research results, validating the BN model’s applicability and demonstrating its ability to derive critical insights for improving construction safety management.

4. Establishment of the CACS and AcciMap Model

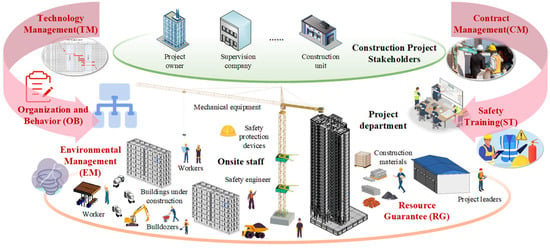

4.1. Structure of the CACS Model

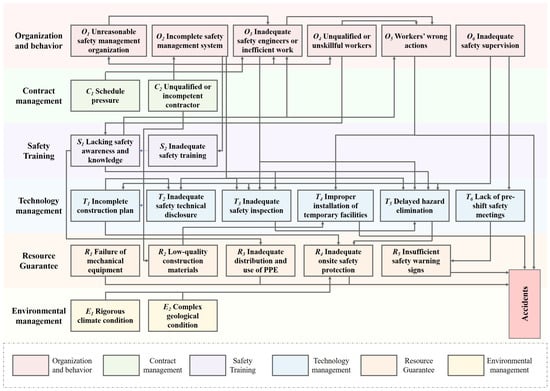

From a systems thinking perspective, safety is an essential objective throughout the construction project lifecycle, which involves different project stages, participants, environmental factors, and management factors. Drawing on the risk management framework proposed by Rasmussen and previous literature research [8,30,31,36,39,41,43,44,45,46,47,48], the CACS model is divided into six layers: Organization and Behavior (OB), Technology Management (TM), Resource Guarantee (RG), Contract Management (CM), Safety Training (ST), and Environmental Management (EM), as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The six layers of the CACS Model.

To ensure the model possesses both theoretical robustness and empirical representativeness, the causal factors within these layers were developed through a rigorous three-stage procedure. Initially, 331 official construction accident investigation reports were analyzed using an open-axial coding approach. In this process, causal statements were extracted, categorized, and synthesized into higher-level concepts to capture recurring accident mechanisms. Subsequently, to balance empirical frequency with conceptual relevance, a factor was retained only if it appeared in at least five accident reports or possessed strong theoretical grounding in system-based safety literature. Crucially, it should be noted that the causal factors extracted from accident reports are observed categorical variables, not latent constructs. Therefore, Exploratory or Confirmatory Factor Analysis (EFA/CFA) is not conceptually applicable for assessing discriminant validity. Instead, the preliminary factor set was subjected to qualitative expert validation by a panel of 16 experienced safety engineers and project managers, who refined the definitions and verified the logical assignment of each factor to its respective layer. Through this transparent and replicable process, the CACS model was finalized with twenty-three causal factors. These factors reflect patterns consistently observed in accident data and validated by practitioners, ensuring they are both empirically grounded and practically actionable for construction safety management. The detailed factor list is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Causal factors of construction safety accidents within the CACS framework.

4.2. Correlations Among Causal Factors and AcciMap Model

To investigate the correlations among causal factors and develop an AcciMap model supporting construction safety management and accident prevention, this study engaged 16 experts with over five years of practical or theoretical research experience in group discussions. The expert panel comprises three professors, five senior managers from construction firms, two government safety management officials, and six project managers or chief engineers, with detailed information presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Expert basic information statistics.

To ensure the transparency and validity of the causal relationship verification, a structured three-phase consultation protocol was adopted: (1) Individual Independent Screening. Before the group discussion, the preliminary AcciMap framework derived from literature and reports was distributed to each expert. They independently reviewed the causal links based on their specific domain experience to minimize groupthink and reduce individual bias. (2) Cross-Level Collaborative Debate. The experts were organized into sub-groups to debate controversial links. During this phase, experts with extensive on-site management experience provided insights into behavioral triggers (such as task pressure and peer influence), acting as proxies for the operational perspective to bridge the gap in frontline representation. (3) Consensus Confirmation. A final plenary session was held to consolidate the findings. A causal link was retained only if it received approval from over 80% of the panel members.

As expert assessment inevitably contains subjective elements due to differences in professional backgrounds and practical experience, this structured group-discussion process was specifically designed to reconcile divergent viewpoints and reduce individual bias. Through this iterative discussion and consensus building, the correlations between causal factors within and across layers were refined and collectively confirmed, forming the AcciMap model for construction safety accidents, illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

AcciMap Model of Construction Safety Accidents.

The correlations indicate that one causal factor may influence or lead to another factor. In most cases, causal factors in the upper layers impact those in the lower layers. Factors of a given layer also have internal correlations. For example, unqualified or unskilled workers may be more likely to take wrong actions, which can be harmful and lead to unstable formwork/scaffolding. Furthermore, if construction plans are inaccurate or unreliable, risk factors cannot be pre-identified and controlled. Moreover, construction plans serve as the basis for safety disclosure, and inadequate safety disclosure may affect workers’ operations.

In the AcciMap model, the following factors will directly lead to construction safety accidents, which are consistent with the main accident types. (1) O5 (Workers’ wrong actions). Workers’ improper actions can lead to various types of accidents, such as falls from height, collapses, object strikes, and electric shocks. (2) T4 (Improper installation of temporary facilities). Formworks, scaffolds, and platforms are normal temporary support facilities for on-site construction work. In the process of installation and disassembly, they are easy to lose stability and cause collapse. (3) R1 (Failure of mechanical equipment). Improper operation and maintenance of machines can easily cause mechanical failure, which can lead to mechanical injury and lifting injury accidents. (4) R3 (Inadequate distribution and use of PPE). Safety helmets, seat belts, and other personal protective equipment can reduce the risks of falling from height and object strike. (5) R4 (Inadequate on-site safety protection). Falls from height and collapses are usually caused by inadequate site safety/protection.

5. Network Model of Construction Safety Accidents

5.1. Data Collection

This study takes construction safety accident causation as its research focus and collected a total of 331 officially released accident investigation reports from 2005 to 2024. The reports were obtained from the Ministry of Emergency Management of China and the provincial and municipal emergency management departments, which provide authoritative governmental disclosures. Each investigation report contains detailed and verified information on accident type, accident process, direct and indirect causes, casualties, and economic losses, forming a reliable empirical basis for subsequent modeling and analysis. It should be noted that the collected reports represent only publicly disclosed cases during this period and do not cover all construction accidents that occurred nationwide.

To ensure data quality and consistency, all reports underwent a screening and refinement process. First, only production safety accidents occurring during construction activities were retained in accordance with the definitions in the Chinese Production Safety Law. Reports with incomplete causal descriptions, missing key information, or highly ambiguous narratives were removed. Duplicate documents, such as revised versions and reposted notices, were cross-checked and consolidated to avoid double-counting. Although the dataset spans nearly two decades, the causal information extracted in this study is based on factual descriptions of organizational failures, supervision deficiencies, technical mismanagement, and hazardous conditions. These elements are consistently recorded in accident investigations across different years, and therefore, changes in regulatory terminology have limited influence on the extraction and interpretation of the core causal factors. Through this process, the initial dataset of over 400 reports was refined to 331 valid and analyzable cases. Although the official nature of these reports ensures a certain level of accuracy, variations in reporting practices across regions and the underreporting of minor incidents introduce a degree of sample bias that should be acknowledged when interpreting the results.

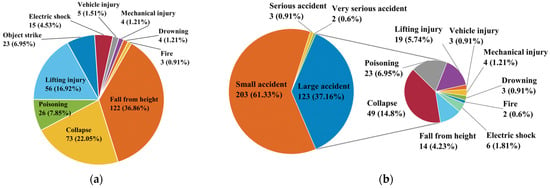

Descriptive statistics of the final dataset are shown in Figure 5. According to legal classifications, the accidents fall into ten categories. Among them, falls from height account for the largest proportion (36.86%), followed by collapse (22.05%), lifting injury (16.92%), and poisoning (7.85%). Less frequent categories include object strike, electric shock, vehicle injury, mechanical injury, drowning, and fire. In terms of severity, the dataset contains 203 small accidents (61.33%), 123 large accidents (37.16%), 3 serious accidents, and 2 very serious accidents. Notably, collapse accidents account for 49 of the 123 large accidents, indicating that collapse events tend to lead to more severe outcomes and warrant focused attention in accident prevention.

Figure 5.

Distribution Statistics of the Dataset: (a) Accident type distribution; (b) Distribution of severity levels.

5.2. Establishment of Bayesian Network Model

The BN model for construction safety accidents was established through the following three steps:

Step 1: Determination of nodes and states in the BN model. Section 4 established the CACS and AcciMap models, which include 23 accident-causing factors. To optimize the BN structure and ensure the robustness of probabilistic reasoning, the initial 23 factors were refined. Although T6 (Lack of pre-shift safety meetings) and R5 (Insufficient safety warning signs) are recognized as relevant safety risks, including nodes with extremely sparse data in a BN can lead to overfitting and unstable parameter learning. Therefore, following expert consultation, these factors were not simply discarded but were subsumed into broader categories to preserve their causal implications. Specifically, the risk of T6 was integrated into S2 (Inadequate safety training) as it represents a daily procedural failure of safety education, and R5 was incorporated into R4 (Inadequate on-site safety protection) as a subset of site safety facilities. Consequently, 21 causal factors were ultimately retained as BN nodes.

Additionally, an “Accident” node was introduced to represent the combined effects of multiple causal factors leading to construction safety accidents. The states of this node encompass the main accident categories extracted from the investigation reports, including fall from height, collapse, lifting injury, and other types of accidents. In total, 22 nodes were identified as the basis for constructing the BN model. To enhance the model’s expressive capacity, possible states were defined for each node to reflect various real-world scenarios, as shown in Table 4. Accident investigation reports typically record causal factors in binary (0–1) form, indicating the presence or absence of a factor. However, safety risks in reality are non-binary and graded. To capture this, the nodes in the BN were modeled as latent variables with three states. The “Low” state corresponds to the empirical observation of “absence” (0), representing a negligible risk level. The “Medium” and “High” states differentiate the intensity of the risk when the factor is “present” (1). Since raw accident reports do not explicitly distinguish between medium and high severity, this distinction is treated as a hidden variable to be learned probabilistically, allowing the model to reflect the varying degrees of influence that different factors have on accidents. This process is implemented using the Expectation–Maximization (EM) algorithm, which iteratively alternates between the E-step (calculating the expected values of unobserved variables) and the M-step (updating model parameters to maximize the likelihood function). This approach estimates the optimal parameters of the BN under conditions of incomplete data, with further details provided in Step 3.

Table 4.

Network node and states.

Step 2: Definition of network structure that describes node correlations. To ensure the objectivity of causal links and mitigate the limitations of subjective judgment, this study adopted a hybrid structure-learning strategy. Initially, the AcciMap model served as the foundation for establishing the causal framework and defining Tier Ordering. This logical hierarchy ensures that management factors in the upper tiers constrain operational factors in the lower tiers, thereby preventing logical fallacies such as reverse causality. Subsequently, strictly within these expert-defined constraints, the Greedy Thick Thinning algorithm embedded in GeNIe 2.3 was employed to refine the network structure using the dataset of 331 accident reports. By computing the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), this algorithm tested the validity of each arc. Links initially hypothesized by experts but lacking statistical support were pruned, while significant probabilistic dependencies overlooked by qualitative analysis were identified and verified. The final network structure thus represents an integration of theoretical knowledge and empirical evidence.

Step 3: Determination of network parameters. For a given BN, the initial probabilities of root nodes can be obtained from collected data. In this study, the conditional probability tables (CPTs) were learned directly from the empirical data using the Expectation–Maximization (EM) algorithm to ensure objectivity and reproducibility. The EM algorithm [49] uses iterative ideas to process incomplete datasets and is a general approach for finding maximum-likelihood estimates of a set of parameters θ. In this study, the “incomplete data” refers to the unobserved severity levels of the risk factors. While the accident reports indicate whether a factor occurred (Binary 1), they do not explicitly distinguish between “Medium” and “High” severity. The EM algorithm addresses this by treating the risk intensity as a hidden variable. Through iteration, it statistically distributes the probability of “occurrence” (1) across the “Medium” and “High” states based on the network structure and correlations, while “non-occurrence” (0) is mapped to the “Low” state. The EM algorithm begins by randomly assigning a configuration θ0 to θ when the algorithm is used in parameter learning. Suppose that θt is the outcome after t iterations. The calculation process then follows two steps:

- (1)

- Suppose that Xmis is a variable with a missing value in an incomplete dataset D. Let Xmis = xmis, such that we can obtain a complete dataset by adding xmis to D. During the process, Xmis may have more assignments; that is, the EM algorithm assigns a weight Wxmis for each possible result. The weighted sample is then given by the following:where . The weight ranges from 0 to 1. During the process of data supplement, each incomplete sample is replaced by a complete weighted sample.

- (2)

- For the complete sample obtained in step (1), the maximum likelihood is calculated by estimating θt + 1 using Equation (2).

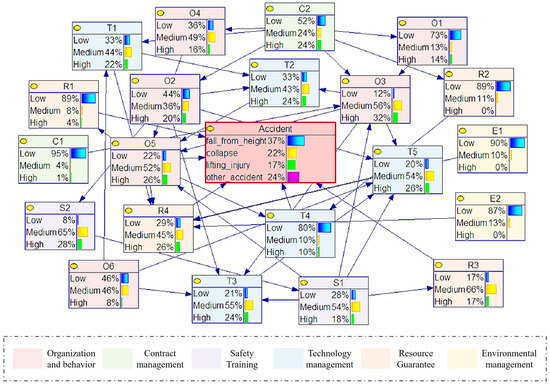

If the result meets the accuracy requirements, the algorithm ends; if not, return to step (1) and repeat the algorithm. Finally, the prior probability of each node is obtained by using the EM algorithm, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The parameter learning results of the BN model.

5.3. Diagnostic Reasoning

Diagnostic reasoning infers the posterior probability of causal factors given the occurrence of an accident event. It is calculated using Bayes’ theorem as follows:

When the accident has occurred, the posterior probability of each factor is calculated by using the above formula.

Crucially, it is important to emphasize that the fuzzy logic methods introduced below were not used for the parameter learning of the BN (which relied solely on the EM algorithm as described in Section 5.2). Instead, fuzzy membership functions were applied only in this post-inference phase. The justification for this additional step lies in the practical requirements of safety management. The direct output of the BN diagnostic is a probability distribution vector across three states rather than a single comparable metric. This presents a challenge for decision-makers: comparing and ranking risk factors based on multi-dimensional probability vectors is neither computationally nor cognitively intuitive. A factor with a moderate probability of a “High” severity state might be more critical than one with a high probability of a “Medium” severity state, but raw probabilities do not explicitly weight this severity difference.

To address this, the introduction of Fuzzy Set Theory serves a specific purpose: dimensionality reduction and severity weighting. By mapping the probabilistic states to fuzzy linguistic terms, we transform the state distribution vector into a single scalar value-the Fuzzy Possibility Score (FPS). This transformation does not alter the underlying probabilistic data but aggregates it into a unified, severity-weighted index that facilitates the direct ranking of causal factors and the identification of the critical failure path.

To facilitate intuitive interpretation of the posterior probabilities, the probability space [0, 1] is discretized into three linguistic categories: Low (L), Medium (M), and High (H). With reference to the classical fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method [50,51,52], representative central values of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 are assigned to these categories, following a symmetrical partitioning principle to ensure each category corresponds to a well-defined risk level. This discretization converts continuous posterior probabilities into easily interpretable linguistic risk states. The resulting fuzzy values are then aggregated into a single crisp value, the Fuzzy Possibility Score, enabling a clear and direct comparison of causal factors.

The diagnostic reasoning is implemented using the GeNIe 2.3 software through the following steps.

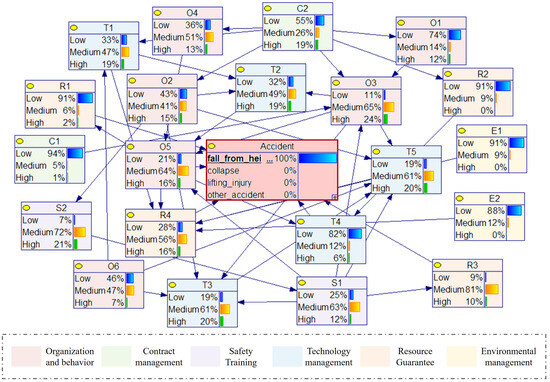

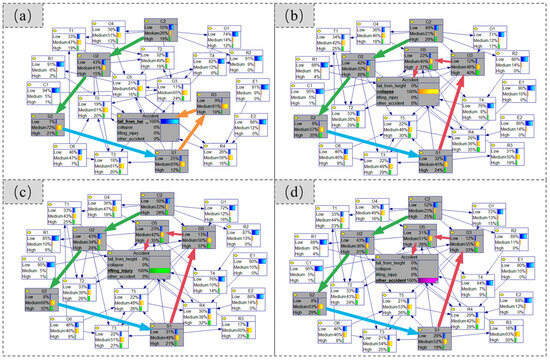

Step 1: (1) Set up the evidence node. The prior probability of “fall from height” is set to 100%, that is, P (A = 1) =1. The posterior probabilities of its parent nodes can be obtained using Formula (3), as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The reasoning result of “Fall from height = 1” of the accident node.

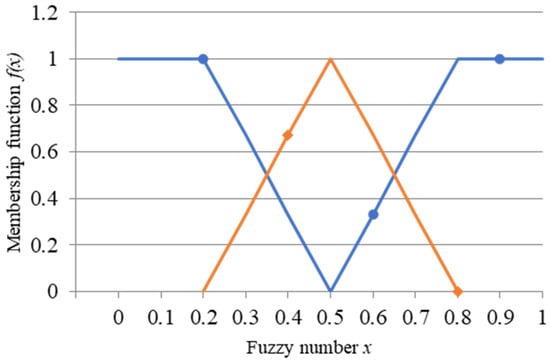

(2) Transforming reasoning results into fuzzy sets. The posterior probabilities of its parent nodes can be transformed into a fuzzy value, which reflects the comprehensive risk of factors. Based on the predefined linguistic variables (L, M, and H) and their membership functions, the posterior probabilities of the parent nodes are converted into fuzzy values to represent their comprehensive risk levels, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Fuzzy numbers for linguistic values. (Note: Different colored lines and dots represent distinct fuzzy sets used for the comprehensive risk level transformation.)

The membership functions of these fuzzy numbers in triangular or trapezoidal fuzzy members are as follows:

(3) Determining the average fuzzy number. Taking the “O5” node as an example, its posterior probability distribution is: 21% “L”, 64% “M”, 16% “H”. Using the α-cut method to deal with the reasoning result, the average fuzzy numbers are calculated.

Let

Then, and .

Thus, the membership function of an average fuzzy number is as follows:

(4) Converting the average fuzzy number into FPS (Fuzzy Possibility Score). FPS represents the most possible value that an event may occur. The conversion is based on the left and right fuzzy ranking method proposed by Chen and Hwang [53]. Among them, the fuzzy maximization set and the minimizing set are defined as follows:

Then, the right and the left FPS of W were obtained as follows:

After obtaining the left and right scores of W, the FPS of W was defined as follows:

(5) Using the same method, the FPS of the other four parent nodes of the accident node can be obtained as R3 (0.5022), R4 (0.4737), T4 (0.3304), and R1 (0.2988). Among them, R3 (Inadequate distribution and use of PPE) has the largest fuzzy probability value, which is the factor causing the occurrence of falls from height. Therefore, we infer the causal link R3→fall from height.

Step 2: R3 is selected as an evidence node, and the FPS of R3’s parent nodes is calculated. However, R3 only has one parent node, which is determined as S1 (0.4680). Therefore, it is further inferred as “S1→R3→fall from height”.

Step 3: Similarly, S1 is selected as a new evidence node, and the FPS of its parent node is then obtained as S2 (0.5306). Finally, O2 (0.4376) is the highest probability node of causing S2, and C2 (0.4202) is also the highest probability node of causing O2.

Step 4: Based on the above processes of diagnostic reasoning, the most probable path can be obtained as C2→O2→S2→S1→R3→fall from height, as shown in Figure 9a. According to the same method, the path leading to collapse, lifting injury, and other accidents is C2→O2→S2→S1→O3→O5→collapse/ lifting injury/ other accidents, as shown in Figure 9b–d. The results indicate that the causal structures of different accident types are largely consistent. This pathway reflects a top–down failure of the safety management system: C2 (Unqualified or incompetent contractor) and O2 (Incomplete safety management system) weaken S2 (Inadequate safety training), which in turn reduces S1 (Safety awareness and knowledge) and leads to R3 (Improper use or lack of personal protective equipment). Such cascading degradation from organizational to behavioral levels illustrates how latent managerial deficiencies gradually evolve into direct unsafe acts at the worksite.

Figure 9.

Diagnostic reasoning paths for different types of construction accidents: (a) Most probable causal path for fall from height; (b) Causal path for collapse; (c) Causal path for lifting injury; (d) Causal path for other accidents. (Notes: Colored arrows and grey-shaded nodes highlight the most probable causal paths.)

5.4. Sensitivity Analysis

In this study, the BN is developed primarily as a diagnostic and explanatory tool rather than a predictive classifier. For this reason, common predictive validation procedures such as train–test splitting or cross-validation are not directly applicable. The dataset consists of 331 unique accident investigation reports, each representing a non-repetitive event with sparse distributions across multiple causal factors and node states. Splitting such data would increase sparsity and degrade the stability of parameter learning, particularly for low-frequency causal nodes. Therefore, the model is trained on the full dataset, and its reliability is evaluated through sensitivity analysis, which assesses whether the inferred causal relationships behave consistently with established accident causation logic.

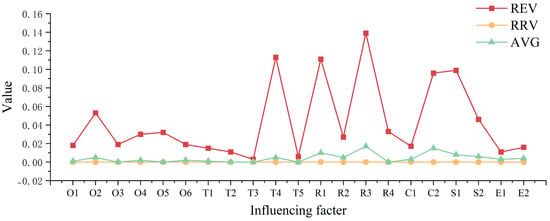

In this research, three key performance indicators, REV, RRV, and AVG, are used to measure the contribution of each causal factor Xi toward the target node A. REV (Risk Expansion Value) is used to assess the performance of risk expansion for each causal factor Xi, represented by IREV (Xi). RRV (Risk Reduction Value) reflects the performance of risk reduction for each causal factor Xi, represented by IRRV (Xi). AVG (Average Sensitivity Measure) is used to measure the average sensitivity of causal factor Xi, represented by IAVG (Xi). IREV (Xi), IRRV (Xi), and IAVG (Xi) can be calculated by Formulas (14)–(16).

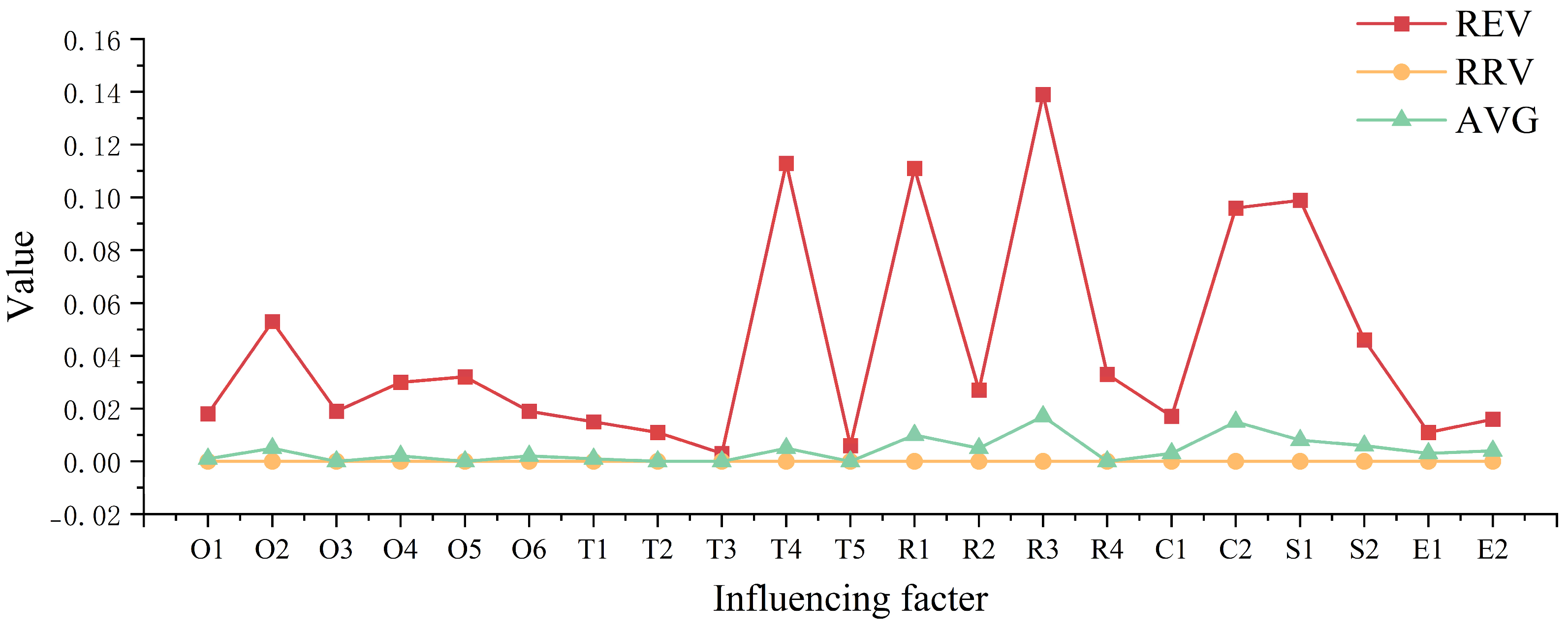

Taking the “accident” node as the target node, the REV, RRV, and AVG three key performance indicators of each node are calculated using the above formula, and the results are shown in Figure 10. Among them, the higher the value of IAVG (Xi), the more responsibility Xi has in risk sensitivity of A, such as R3 (Inadequate distribution and use of PPE), C2 (Unqualified or incompetent contractor) and R1 (Failure of mechanical equipment) have relatively high sensitivity, which are called sensitive factors. In other words, small changes in these factors will have a significant impact on construction safety management. For example, some workers fail to wear personal protective equipment, such as a safety helmet and a safety belt, thus causing fall from height accidents. Therefore, managers should focus on monitoring the changes in these factors to improve the overall reliability of construction safety management. The sensitivity results show that even small improvements in R1 (Failure of mechanical equipment) or R3 (Inadequate distribution and use of PPE) can lead to significant reductions in accident probability. In practice, this means that safety managers should continuously monitor these high-sensitivity nodes. Targeted interventions at R1 and R3 can achieve the greatest overall effect with limited resources. This finding provides a quantitative basis for prioritizing preventive measures in construction safety management.

Figure 10.

Result of sensitivity analysis.

5.5. Major Results

Based on the results of diagnostic reasoning and sensitivity analysis, considering the occurrence frequency of each factor in 331 accidents, the degree of influence on the accident, and whether it is located in the most probable path, 23 causal factors are divided into critical factors, sensitive factors, and general factors, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Network analysis results of construction safety accidents: critical, sensitive, and general factors.

- (1)

- Factor analysis

- Critical factors. According to the diagnostic reasoning, the factors on the most probable path include C2, O2, S2, S1, O3, R3, and O5. Therefore, the seven critical factors of construction safety accidents are identified as: O2 (Incomplete safety management system), O3 (Inadequate safety engineers or inefficient work), O5 (Workers’ wrong actions), R3 (Inadequate distribution and use of PPE), C2 (Unqualified or incompetent contractor), S1 (Lacking safety awareness and knowledge), and S2 (Inadequate safety training). These factors should be given priority in safety management practice.

- Sensitivity factors. Through sensitivity analysis, three sensitive factors are determined as R1 (Failure of mechanical equipment), R3 (Inadequate distribution and use of PPE), and C2 (Unqualified or incompetent contractor). Among them, C2 and R3 are not only critical factors but also sensitive factors. These factors should also be highly valued and strictly controlled.

- General factors. In addition to the critical factors and sensitive factors, the other 13 factors are called general factors. The control effect of these factors is better and should be maintained.

- (2)

- Path analysis.

According to diagnostic reasoning, the most probable path leading to accident are identified as C2 (Unqualified or incompetent contractor)→O2 (Incomplete safety management system)→S2 (Inadequate safety training), S2 (Inadequate safety training)→S1 (Lacking safety awareness and knowledge), S1 (Lacking safety awareness and knowledge)→R3 (Inadequate distribution and use of PPE)→Accident and S1 (Lacking safety awareness and knowledge)→O3 (Inadequate safety engineers or inefficient work)→O5 (Workers’ wrong actions)→Accident, which represents the formation mechanism of typical construction safety accidents. In other words, the occurrence of accidents does not strictly follow the most probable path, and it can start from the root node or from the child node.

6. Case Study

6.1. Accident Occurrence and Investigation Process

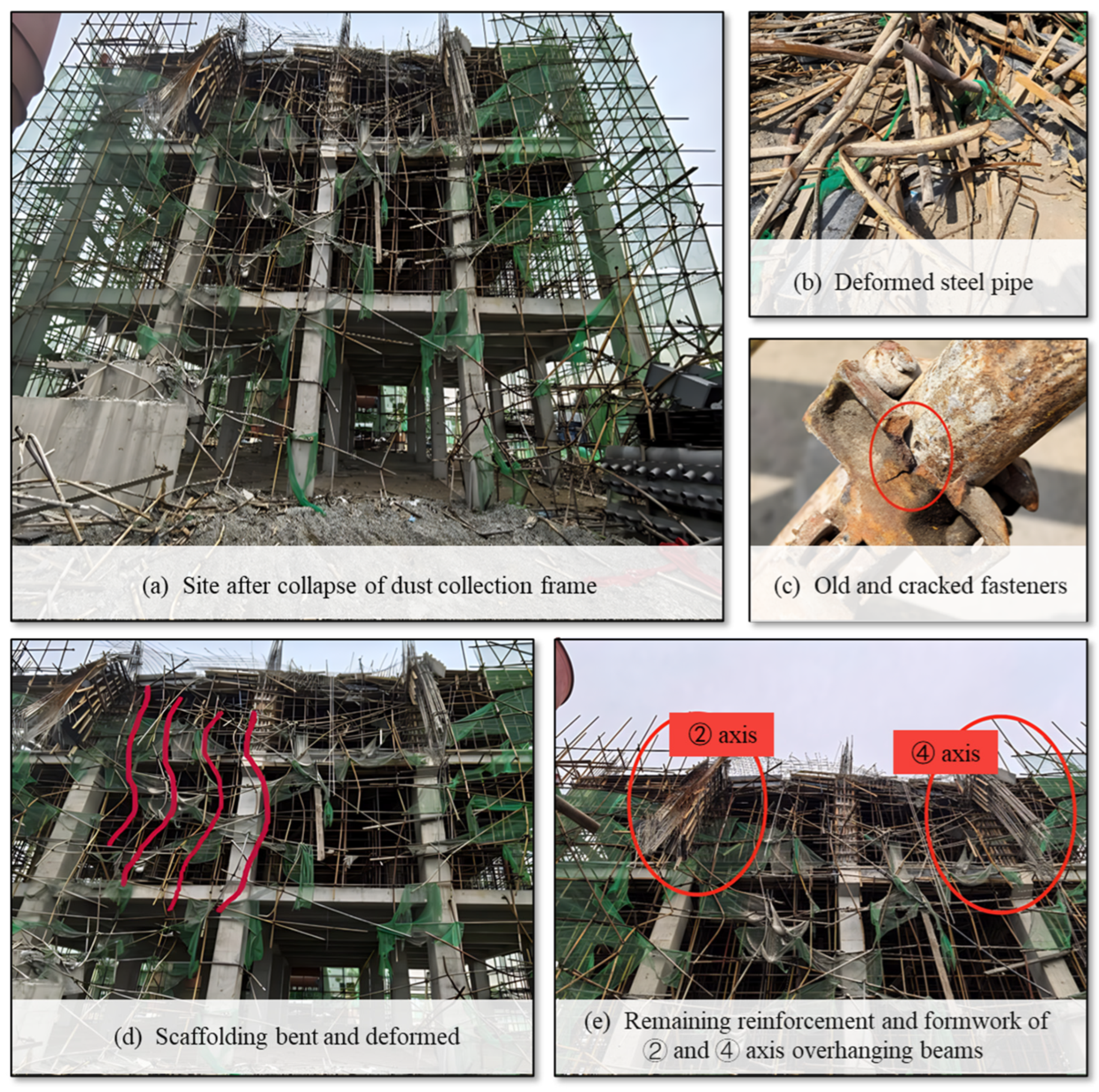

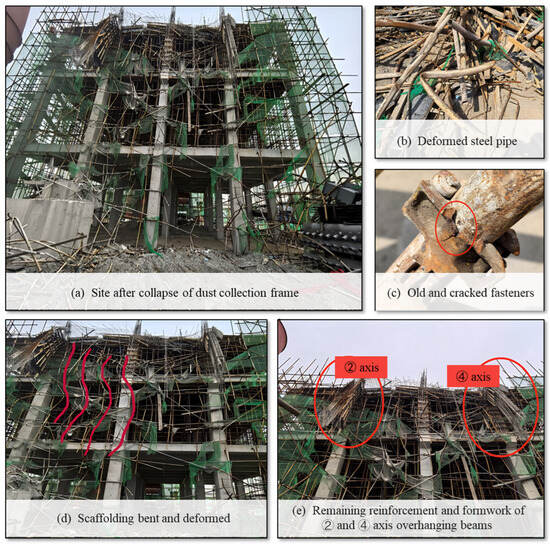

On 19 June 2024, a catastrophic collapse of a large formwork support occurred at the construction site of the assembly building for Inner Mongolia Junping Environmental Protection Technology Co. At the time, four operators were engaged in concrete pouring operations on the restraining platform. Due to the use of substandard materials, non-compliance with industry standards, and improper construction practices, the entire restraining platform formwork suddenly collapsed. The operators were buried under the fallen template, supporting steel pipes, loose concrete, and other debris. Tragically, the accident resulted in four fatalities and property damage exceeding 5 million yuan. The scene after the accident is shown in Figure 11a.

Figure 11.

Site scenes after the accident.

Following the incident, the People’s Government of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region mobilized an investigation team, which included officials and experts from various relevant departments, including the Emergency Management Department, the Public Security Department, the Housing and Urban-Rural Development Department, the General Trade Union, and the Baotou Municipal Government. After nearly four months of investigation, the final report was published in October 2024. The report thoroughly analyzed both the direct and indirect causes of the formwork support collapse.

According to the investigation report, the direct causes of the accident were: The construction unit employed steel pipes, couplers, and U-shaped supports with performance indicators that failed to meet regulatory standards. This significantly weakened the load-bearing capacity and compromised the rigidity of the formwork support. The construction unit failed to install horizontal braces on the scaffolding as required by safety standards, resulting in eccentric loading on the U-shaped supports. This failure, combined with improper concrete pouring procedures, caused uneven load distribution, which led to the deformation and collapse of the formwork support during the pouring process.

- Poor quality of steel pipes and couplers: Third-party on-site sampling and testing confirmed that the steel pipes and couplers used in the high formwork system did not meet national standards. This serious non-compliance severely weakened the formwork support’s load-bearing capacity and reduced its overall rigidity, jeopardizing its stability.

- Corrosion and structural damage to steel pipes and couplers: The site inspection revealed significant corrosion, cracks, and visible dents in the steel pipes, as well as old cracks in the couplers, as shown in Figure 11b,c.

- Improper scaffolding installation. The high formwork system on the constraint platform had completely collapsed, and the scaffolding on the first, second, and third levels had deformed and was missing, as shown in Figure 11d. The horizontal braces were not installed as per regulations, and the wall ties were missing.

- Non-compliant concrete pouring sequence and method: The construction unit used an incorrect, layer-by-layer pouring method from west to east for the concrete on axes ② and ④. This practice deviated from the prescribed method of symmetrical pouring from the center of the span to the ends, resulting in uneven load distribution on the large formwork system. The inspection revealed that while the cantilever beam at axis ④ had been poured to the top elevation, there were pouring marks at the east end of the cantilever beam at axis ②, with minimal concrete poured at the beam root over the 5–6 m section, as shown in Figure 11e.

Additionally, the indirect causes were related to management deficiencies by the involved construction parties, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Identification of accident causes with CACS.

6.2. Identification of Accident Causes

The causes of the construction collapse accident can be identified using the CACS model proposed in this study, and the levels and details of the accident’s causes are summarized in Table 6. It was observed that a total of 14 of the 23 causes in the CACS model appeared in this case, including six of the seven critical factors, one of the three sensitive factors, and seven of the 13 general factors. Most of the critical and sensitive factors with high importance occurred, while only a few of the general factors occurred. This shows that the established CACS model and classification results can effectively reflect the actual situation of construction safety management, which is reasonable and practical. The causal chain identified in the Baotou formwork collapse, which includes C2 (Unqualified or incompetent contractor), O2 (Incomplete safety management system), S2 (Inadequate safety training), and O5 (Workers’ wrong actions), mirrors the top–down propagation mechanism revealed by the BN model. Both the case evidence and the model results show that managerial deficiencies at higher levels gradually translate into procedural violations and unsafe acts at the operational level. This consistency confirms that the proposed framework not only predicts accident patterns statistically but also captures the real-world mechanisms through which such events occur.

Moreover, to verify the validity of the proposed CACS and BN framework, the Baotou formwork collapse case was further analyzed through quantitative inference. When the case-specific evidence nodes were entered (C2 = High, O2 = High, S2 = High, O5 = High), the posterior probability of “Accident = Collapse” increased from the prior baseline of 0.22 to approximately 0.68. This result shows that the model effectively captured the cumulative effect of multiple managerial and behavioral deficiencies observed in the real event. The sensitivity analysis under the same conditions identified O2 (Incomplete safety management system) and C2 (Unqualified or incompetent contractor) as the most influential nodes, consistent with the key deficiencies documented in the official investigation report.

This quantitative validation shows that the proposed framework can reproduce real accident outcomes instead of merely describing them. It also provides a potential early-warning mechanism: if similar high-risk combinations (C2 = High, O2 = High, S2 = High) are detected in ongoing projects through digital supervision or inspection data, the model would generate a warning with a probability above 0.6, allowing timely managerial intervention. These findings confirm the potential of the CACS and BN models as diagnostic and predictive tools for proactive safety management in construction projects.

Nevertheless, comparing the model results with the investigation report highlights certain limitations. The BN relies on standardized nodes, which makes it difficult to capture qualitative nuances found in the real-world event. For instance, specific factors like the depth of safety culture deficiencies, implicit pressure from the schedule, or technical details like the asymmetric pouring sequence lack direct quantitative indicators. Consequently, the CACS-BN framework functions primarily as a tool for systemic risk diagnosis and works best when paired with qualitative forensic analysis. To further demonstrate the applicability and diagnostic consistency of the CACS-based BN model across different accident categories, two representative cases were selected for detailed analysis and are presented in Appendix A. Specifically, Appendix A.1 analyzes a recent tower crane dismantling accident (May 2025), serving as an out-of-sample validation to test the model’s predictive capability on new data. Appendix A.2 presents a typical “Fall from Height” accident in a self-built housing project. These supplementary verifications confirm that the proposed framework remains robust across diverse accident scenarios beyond the single collapse case discussed above.

7. Discussion

The proposed CACS and BN framework offers a quantitative validation of construction accident causation, demonstrating that safety performance is driven by a combination of seven critical and three sensitive factors. Our results align with the findings of Zhang et al. [54], confirming that organizational deficiencies, particularly O2 (Incomplete safety management system)and C2 (Unqualified or incompetent contractor), act as primary root causes. These latent failures propagate through the system, eventually triggering operational errors such as O5 (Workers’ wrong actions) and R3 (Inadequate distribution and use of PPE). In contrast to previous qualitative studies [55,56], the BN model in this study quantifies this propagation, illustrating how managerial shortcomings significantly amplify the probability of frontline errors.

A major contribution of this work is the identification of a persistent governance gap between regulatory intent and actual on-site implementation. Despite the comprehensive nature of China’s safety regulations, the recurrence of O2 and C2 as critical risk factors reveals a disconnect in enforcement, especially within subcontracted projects [57]. The model quantitatively indicates that due to O3 (Inadequate safety engineers or inefficient work), high-level safety policies often fail to translate into compliance at the operational level. This underscores the need to shift from static compliance checks to dynamic, data-driven supervision. This perspective is consistent with recent advancements in Digital Twin technology described by Han et al. [58] and Wang et al. [59], who advocate for integrating dynamic risk prediction models with real-time site monitoring to achieve closed-loop safety management.

Nevertheless, comparing the model’s standardized predictions with specific accident narratives reveals certain limitations. While the BN effectively identifies systemic risk trends, it is less capable of capturing high-context, low-frequency triggers. Specific situational factors often noted in forensic reports, such as sudden schedule acceleration, temporary verbal commands, or implicit peer pressure, are not explicitly represented in the standardized node structure. Consequently, the model serves as a diagnostic aggregate of risk but cannot fully reconstruct the nuanced, nonlinear decision-making sequences characteristic of individual accidents.

Several specific constraints also warrant reflection. Regarding the composition of the expert panel, this study relied on experienced safety officers and site managers to act as proxies for the operational perspective. Although this approach captured key behavioral triggers, the absence of direct representation from frontline construction workers means that specific task-level insights, such as physical fatigue patterns or subtle peer dynamics, may be underrepresented. Additionally, the data-driven learning process using the EM algorithm relies on statistical regularity, which implies that rare but potentially catastrophic risk factors might be underweighted due to data sparsity. Therefore, the CACS-BN framework should be considered a systemic decision-support tool intended to complement, rather than replace, detailed qualitative forensic investigations.

8. Conclusions

In this study, we combined systems thinking, statistical analysis, and BN modeling to explore and prevent construction safety accidents, leading to the following conclusions:

- (1)

- A Construction Accident Causation System (CACS) model was established based on systems thinking. Construction safety accident causes were considered as a social and technological system comprising six layers: organization and behavior, technology management, resource guarantee, contract management, safety training, and environmental management. These layers were further decomposed into 23 factors related to safety management.

- (2)

- A sample of 331 construction safety accidents was collected, and their investigation reports were analyzed. The basic mechanism of construction safety accidents was identified, including the accident types and severity levels. More importantly, the correlations among the 23 factors were identified, and an AcciMap for construction safety accidents was established, which provided a basis for the BN analyses.

- (3)

- A BN diagram was obtained from the AcciMap. The most probable path and the critical factors were determined based on diagnostic reasoning, including O2 (Incomplete safety management system), O3 (Inadequate safety engineers or inefficient work), O5 (Workers’ wrong actions), R3 (Inadequate distribution and use of PPE), C2 (Unqualified or incompetent contractor), S1 (Lacking safety awareness and knowledge), and S2 (Inadequate safety training). These results can provide a robust basis for safety management and accident prevention.

- (4)

- A typical construction accident was selected to conduct a case study. Based on the analysis of the accident occurrence process and official investigation results, the accident causes and corresponding distribution were identified using the CACS model. The results showed strong consistency with the BN analysis of 331 accidents, showing that the CACS model and factor classification are reasonable and practical.

- (5)

- Finally, it is recommended that all relevant participants and practitioners enhance their safety awareness and knowledge levels, regulate their behavior at work, and attempt to discover and eliminate on-site hazards to create a stable working environment, reduce safety risk, and finally prevent the occurrence of construction safety accidents.

Despite these contributions, this study still has certain shortcomings that require further improvement. The analysis heavily relies on Chinese accident reports, which may not fully capture the conditions of regions with different regulatory systems, cultural practices, or operational approaches. Furthermore, while the BN model effectively quantifies causal relationships, its dependence on historical data might overlook new risks associated with emerging technologies or construction methods. Although subjective input from expert discussions was minimized, it still introduces a degree of bias into the model’s structure. Future research could address these gaps by incorporating international datasets, integrating real-time data collection methods (such as IoT sensors), and expanding expert panels to include certified frontline workers to strictly incorporate task-level experiential knowledge.

Author Contributions

W.Z. and N.X. conceived the study and were responsible for data collection, analysis, and original draft writing; Y.C. conducted the case study and revised the manuscript; T.Z. contributed to data interpretation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Technologies R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2021YFB3301100).

Data Availability Statement

The empirical data underpinning this investigation’s outcomes can be acquired upon formal request directed to the corresponding author. Certain datasets are subject to restrictions owing to privacy and ethical imperatives.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments that improved the quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Appendix A. Supplementary Case Verification

Appendix A.1. “5·6” Major Hoisting Injury Accident at Plot N1–01, Yangpu Riverside, Shanghai

This accident occurred on 6 May 2023 during the dismantling of a tower crane at the N1–01 plot project in Yangpu Riverside, Shanghai. Improper operation during the dismantling process led to the fall of the tower crane’s balance arm, resulting in three deaths and direct economic losses of approximately 4.5 million yuan. The detailed identification of causal factors mapped to the CACS model is provided in Table A1.

Table A1.

Causal factor identification for the “5·6” Major Hoisting Injury Accident.

Table A1.

Causal factor identification for the “5·6” Major Hoisting Injury Accident.

| Level | Accident Cause | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Critical | Incomplete safety management system (O2) | The tower crane installation/dismantling unit lacked safety systems, failed to clarify on-site supervision responsibilities of deputy team leaders and assistants, and had no regulations for safety belt supervision in high-altitude operations or bolt removal sequence control. |

| Workers’ wrong actions (O5) | Workers operated in violation of rules: removed balance arm bolts before finishing counterweight removal; three high-altitude workers failed to fasten safety belts, causing falling casualties. | |

| Unqualified or incompetent contractor (C2) | The unit conducted unlicensed hoisting commands with chaotic work assignments; the project manager failed to identify hazards, such as illegal dismantling and unfastened safety belts. | |

| Lacking safety awareness and knowledge (S1) | Workers had weak safety awareness, lacked knowledge of balance arm structural risks, and ignored safety belt fastening requirements for high-altitude operations. | |

| Inadequate safety training (S2) | The unit did not conduct special safety training or pre-job briefing, leading to workers’ lack of standardized operation awareness. | |

| Sensitive | Inadequate distribution and use of PPE (R3) | Though safety belts were available on-site, their proper use was unsupervised; PPE failed to function, resulting in fatal falls. |

| General | Inadequate safety supervision (O6) | The general contractor’s safety officer did not supervise the entire tower crane dismantling process or stop violations, leaving on-site supervision absent. |

| Unqualified or unskillful workers (O4) | Unlicensed personnel commanded hoisting; some installers/dismantlers were unskilled, causing structural instability via violations. |

Appendix A.2. “11·11” General High-Altitude Fall Accident at a Self-Built Housing Site, Wenchang, Hainan

This accident occurred on 11 November 2023 during the construction of a six-story self-built residential building in Wenchang, Hainan. A worker fell from the 5th floor due to not wearing a safety belt, resulting in one death. The detailed causal analysis is presented in Table A2.

Table A2.

Causal Factor Identification for the Self-Built Housing Construction Accident.

Table A2.

Causal Factor Identification for the Self-Built Housing Construction Accident.

| Level | Accident Cause | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Critical | Incomplete safety management system (O2) | The self-built housing construction company did not establish a complete high-altitude operation safety management system, with no clear regulations on the configuration of on-site fall protection facilities and the supervision of PPE use. |

| Workers’ wrong actions (O5) | The worker Liu did not fasten his safety belt when working on the fifth floor. He acted carelessly during the operation and accidentally fell from a high place, which was the direct cause of the accident. | |

| Lacking safety awareness and knowledge (S1) | The on-site construction workers had weak safety awareness, did not recognize the serious consequences of high-altitude operations without wearing safety belts, and lacked basic risk prevention awareness in construction operations. | |

| Inadequate safety training (S2) | The construction company did not organize targeted safety training for high-altitude operation personnel. It failed to conduct pre-job safety disclosure on fall protection knowledge and standard operating procedures, resulting in the workers’ lack of necessary safety operation knowledge. | |

| Inadequate safety engineers or inefficient work (O3) | The construction company did not arrange full-time and qualified safety engineers to be on-site. No one supervised the workers’ operation process, and violations such as not wearing safety belts were not stopped in time. | |

| Sensitive | Inadequate distribution and use of PPE (R3) | The construction company did not urge workers to standardize the use of safety belts. The workers did not use the necessary personal protective equipment during high-altitude operations, which directly led to the death of the worker after falling. |

| General | Inadequate on-site safety protection (R4) | The construction site did not install anti-fall nets as required for high-altitude operations. The temporary safety protection facilities were missing, which failed to form a secondary protection for workers in high-altitude operations. |

| Inadequate safety supervision (O6) | The relevant regulatory departments did not conduct strict supervision and inspection on the safety of self-built housing construction. They failed to find and urge the rectification of problems such as the lack of protective facilities and inadequate training at the construction site in a timely manner. |

References

- Perttula, P.; Korhonen, P.; Lehtelä, J.; Rasa, P.-L.; Kitinoja, J.-P.; Mäkimattila, S.; Leskinen, T. Improving the Safety and Efficiency of Materials Transfer at a Construction Site by Using an Elevator. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2006, 132, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.; Nunes, I.L.; Ribeiro, R.A. Occupational Risk Assessment in Construction Industry—Overview and Reflection. Saf. Sci. 2011, 49, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunindijo, R.Y.; Zou, P.X.W. Political Skill for Developing Construction Safety Climate. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2012, 138, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Emergency Management of the People’s Republic of China. The Situation of National Production Safety and Natural Disasters in the First Three Quarters of 2024. Available online: https://www.mem.gov.cn/xw/xwfbh/2024n10y22xwfbh/?menuid=104 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of China. Bulletin on the Safety Accidents of Housing Municipal Engineering. Available online: https://www.mohurd.gov.cn/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Hubei Provincial Emergency Management Department. Accident and Disaster Statistics for January-December 2024. Available online: https://yjt.hubei.gov.cn/fbjd/xxgkml/sjfb/aqscsgkb/202502/t20250207_5532438.shtml (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Mitropoulos, P.; Abdelhamid, T.S.; Howell, G.A. Systems Model of Construction Accident Causation. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2005, 131, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Zhao, T.; Liu, W.; Tang, J. Tower Crane Safety on Construction Sites: A Complex Sociotechnical System Perspective. Saf. Sci. 2018, 109, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkov, V.; Burkova, I.; Barkhi, R.; Berlinov, M. Qualitative Risk Assessments in Project Management in Construction Industry. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 251, 06027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.-C.; Wei, J.; Ting, H.-I.; Lo, T.-P.; Long, D.; Chang, L.-M. Dynamic Analysis of Construction Safety Risk and Visual Tracking of Key Factors Based on Behavior-Based Safety and Building Information Modeling. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2019, 23, 4155–4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomari, K.A.; Gambatese, J.A.; Tymvios, N. Risk Perception Comparison among Construction Safety Professionals: Delphi Perspective. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 04018107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinlolu, M.; Haupt, T.C.; Edwards, D.J.; Simpeh, F. A Bibliometric Review of the Status and Emerging Research Trends in Construction Safety Management Technologies. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2022, 22, 2699–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, T.; Bapat, H.; Patel, D.; van der Walt, J.D. Identification of Critical Success Factors (CSFs) of BIM Software Selection: A Combined Approach of FCM and Fuzzy DEMATEL. Buildings 2021, 11, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdi, M.; Khan, F.; Abbassi, R.; Rusli, R. Improved DEMATEL Methodology for Effective Safety Management Decision-Making. Saf. Sci. 2020, 127, 104705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, H.; Li, M.; Jin, Z.; Huang, J. Unveiling Construction Accident Causation: A Scientometric Analysis and Qualitative Review of Research Trends. Front. Built Environ. 2025, 11, 1602297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medaa, E.; Shirzadi Javid, A.A.; Malekitabar, H. Evolution of Risk Analysis Approaches in Construction Disasters: A Systematic Review of Construction Accidents from 2010 to 2025. Buildings 2025, 15, 3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svedung, I.; Rasmussen, J. Graphic Representation of Accidentscenarios: Mapping System Structure and the Causation of Accidents. Saf. Sci. 2002, 40, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, C.K.H.; Sun, C.; Xia, B.; Jimmieson, N.L.; Way, K.A.; Wu, P.P.-Y. Applications of Bayesian Approaches in Construction Management Research: A Systematic Review. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 29, 2153–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, P.M.; Lenné, M.G. Miles Away or Just around the Corner? Systems Thinking in Road Safety Research and Practice. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2015, 74, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, J. Risk Management in a Dynamic Society: A Modelling Problem. Saf. Sci. 1997, 27, 183–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, R.; Ward, N.J. A Systems Analysis of the Ladbroke Grove Rail Crash. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2005, 37, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveson, N. A New Accident Model for Engineering Safer Systems. Saf. Sci. 2004, 42, 237–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Carmen Pardo-Ferreira, M.; Rubio-Romero, J.C.; Gibb, A.; Calero-Castro, S. Using Functional Resonance Analysis Method to Understand Construction Activities for Concrete Structures. Saf. Sci. 2020, 128, 104771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, R.L.; Mugi, S.R.; Saleh, J.H. Accident Investigation and Lessons Not Learned: AcciMap Analysis of Successive Tailings Dam Collapses in Brazil. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 236, 109308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junjia, Y.; Alias, A.H.; Haron, N.A.; Abu Bakar, N. Identification and Analysis of Hoisting Safety Risk Factors for IBS Construction Based on the AcciMap and Cases study. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinze, J.; Pedersen, C.; Fredley, J. Identifying Root Causes of Construction Injuries. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 1998, 124, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhry, R.M.; Fang, D. Why Operatives Engage in Unsafe Work Behavior: Investigating Factors on Construction Sites. Saf. Sci. 2008, 46, 566–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoła, B.; Szóstak, M. An Occupational Profile of People Injured in Accidents at Work in the Polish Construction Industry. Procedia Eng. 2017, 208, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayati, A.J. Impact of Construction Safety Culture and Construction Safety Climate on Safety Behavior and Safety Motivation. Safety 2021, 7, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazan, E.; Usmen, M.A. Worker Safety and Injury Severity Analysis of Earthmoving Equipment Accidents. J. Saf. Res. 2018, 65, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanni-Anibire, M.O.; Mahmoud, A.S.; Hassanain, M.A.; Salami, B.A. A Risk Assessment Approach for Enhancing Construction Safety Performance. Saf. Sci. 2020, 121, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grill, M.; Nielsen, K. Promoting and Impeding Safety—A Qualitative Study into Direct and Indirect Safety Leadership Practices of Constructions Site Managers. Saf. Sci. 2019, 114, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayati, A. Construction Safety Culture & Climate: The Relative Importance of Contributing Factors. Prof. Saf. 2022, 67, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Larsman, P.; Ulfdotter Samuelsson, A.; Räisänen, C.; Rapp Ricciardi, M.; Grill, M. Role Modeling of Safety-Leadership Behaviors in the Construction Industry: A Two-Wave Longitudinal Study. Work 2024, 77, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-La Rivera, F.; Mora-Serrano, J.; Oñate, E. Factors Influencing Safety on Construction Projects (fSCPs): Types and Categories. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yin, L.; Deng, Y.; Wu, G.; Li, C. Using Cased Based Reasoning for Automated Safety Risk Management in Construction Industry. Saf. Sci. 2023, 163, 106113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skład, A. Assessing the Impact of Processes on the Occupational Safety and Health Management System’s Effectiveness Using the Fuzzy Cognitive Maps Approach. Saf. Sci. 2019, 117, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatefi, S.M.; Tamošaitienė, J. An Integrated Fuzzy DEMATEL-Fuzzy ANP Model for Evaluating Construction Projects by Considering Interrelationships among Risk Factors. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2019, 25, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, J.E.; Rivas, T.; Matías, J.M.; Taboada, J.; Argüelles, A. A Bayesian Network Analysis of Workplace Accidents Caused by Falls from a Height. Saf. Sci. 2009, 47, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Z.; Chen, C. Fuzzy Comprehensive Bayesian Network-Based Safety Risk Assessment for Metro Construction Projects. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2017, 70, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Luo, X.; Zhao, T. Reliability Model and Critical Factors Identification of Construction Safety Management Based on System Thinking. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2019, 25, 362–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, S.; Han, S. Analyses of Systems Theory for Construction Accident Prevention with Specific Reference to OSHA Accident Reports. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2013, 31, 1027–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, N.-W.; Lin, K.-Y.; Hsieh, S.-H. Using Ontology-Based Text Classification to Assist Job Hazard Analysis. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2014, 28, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaosheng, Y.; Xiuyun, L. Importance Evaluation of Construction Collapse Influencing Factors Based on Grey Correlation Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Information Management, Innovation Management and Industrial Engineering, Sanya, China, 20–21 October 2012; Volume 3, pp. 436–441. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, B.H.W.; Yiu, T.W.; González, V.A. Predicting Safety Behavior in the Construction Industry: Development and Test of an Integrative Model. Saf. Sci. 2016, 84, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]