Abstract

Current studies on large-span structural components have largely emphasized flexural performance, whereas multi-ribbed profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slabs may be prone to inclined-section shear failure in the construction stage, particularly at small shear-span ratios. To ensure that the vertical shear capacity of such composite slabs satisfies construction-stage requirements, a numerical model validated against experimental evidence was employed. A systematic parametric study was conducted to clarify the influence of key structural parameters and the shear-span ratio on the vertical shear resistance. On this basis, a calculation method for the vertical shear capacity was proposed based on the strength-equivalence principle and verified against numerical results. The results indicate that the inclined-section shear failure of multi-ribbed profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slabs develops through four characteristic stages, the shear-span ratio governs the transition of failure mode, and slabs with a rib height of h = 150 mm exhibit a pronounced shear-dominated failure when the shear-span ratio is less than 2. Increasing the rib inclination angle degrades the composite interaction between the profiled steel sheeting and concrete, whereas increasing the sheeting thickness and slab depth enhances the load-bearing capacity and stiffness, and longitudinal reinforcement benefits the internal stress redistribution of concrete. A vertical shear capacity model was formulated for the novel multi-ribbed profiled steel-concrete composite slab and verified against numerical results. The research helps to bridge the gap in studies on the vertical shear performance of multi-ribbed profiled steel-concrete composite slabs and offers design guidance for vertical shear checks of composite slabs in the temporary construction stage.

1. Introduction

The acceleration of urbanization, together with the rapid growth of China’s manufacturing industry, has led to a growing demand for long-span structural solutions in public and industrial buildings. Such solutions place higher demands on the design and construction of horizontally loaded floor members [1,2]. Beyond satisfying safety, serviceability and durability requirements, modern floor systems are also expected to exhibit good constructability. In recent years, research on multi-ribbed floor systems has mainly focused on achieving lightweight structures, efficient construction, and reliable evaluation of mechanical performance. To this end, a variety of novel multi-ribbed floor systems have been developed by innovating structural configurations and connection details [3,4], introducing new formwork and digital construction techniques [5], and adopting high-performance materials [6,7]. Their flexural capacity, stiffness and ductility, failure mechanisms, and associated design methods have been systematically investigated through experimental testing in combination with finite element analysis.; Ghasemi et al. [8] combined ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) with high-strength steel (HSS) to develop a new type of ribbed slab and optimized its configuration with self-weight reduction as a key objective. Addressing the limitations of traditional thick concrete slabs in energy and seismic performance, Aladdiz et al. [9] employed expanded polystyrene as permanent formwork and proposed a reinforced-concrete ribbed slab featuring low weight, high strength and superior thermal and acoustic insulation. Zeng et al. [10] developed an assembled integral two-way multi-ribbed hollow composite floor system, in which overall composite action between the precast units and the cast-in situ topping was ensured by longitudinal rebar couplers, shear keys, and cast-in situ joints. To overcome the application constraints of two-way ribbed slabs under conventional formwork, Huber et al. [11] proposed an automated construction route combining 3D-printed stay-in-place formwork with conventional concrete and reinforcement; for an 8 m × 8 m point-supported office floor, a minimum-material size-optimization design (subject to long-term deflection and other serviceability limits) achieved an approximately 40% reduction in concrete volume compared with a statically equivalent solid slab. Alali et al. [12]. experimentally investigated the flexural response of PUSS through full-scale four-point bending tests, highlighting the roles of concrete type and degree of shear connection. When normal-weight and lightweight concretes exhibited similar compressive strengths, the ultimate flexural capacities were comparable, whereas the lower elastic modulus of lightweight concrete resulted in reduced initial stiffness and accelerated cracking. Moreover, decreasing the degree of shear connection reduced the flexural resistance and could induce connector failure at large deflections, together with steel-concrete interface separation. Paul et al. [13] tested four-edge simply supported two-way GFRG-RC ribbed slabs and quantified the dependence of two-way strength enhancement on slab aspect ratio, thereby providing recommended enhancement factors for design. Zheng et al. [14] conducted eight full-scale static tests on precast concrete multi-ribbed sandwich slabs and clarified how the longitudinal rib layout, number of supported edges, and end dry bolted connections govern crack development, initial stiffness, composite interaction, and deflection response, offering evidence for incorporating end-connection effects in the design of assembled multi-ribbed floor systems.

Steel-concrete composite structures are now extensively used in practice. By incorporating high-performance materials and innovative construction techniques, recent studies have sought to further enhance their mechanical performance to satisfy complex and diverse engineering requirements [15,16]. In particular, profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slabs, as a representative plate-type composite system, offer high structural efficiency, reduced self-weight, and a high level of prefabrication, which has prompted continued research interest in recent years. It is widely recognized that the dominant failure mode of floor slabs is flexural failure; consequently, research on the structural performance of composite slabs with profiled steel sheeting has primarily concentrated on their basic flexural resistance. Majdi et al. [17] proposed a cold-formed thin-walled steel-concrete composite floor system and developed a nonlinear FE model explicitly incorporating bond-slip at the steel-concrete interface, demonstrating that interfacial slip markedly degrades both the flexural stiffness and ultimate capacity of the floor system. Dinh et al. [18,19] investigated the influence of post-tensioning on the flexural behavior of profile d-steel-sheet composite slabs through experiments and numerical simulations. It was shown that the geometric anisotropy of the profiled steel sheeting could lead to a reduction in flexural stiffness of up to 50%. The application of post-tensioning within the beam-slab system effectively alleviated this adverse effect, while increasing tendon eccentricity further improved flexural stiffness by 15.2% and 17.3% at the service and ultimate stages, respectively. John et al. [20] examined a new two-way composite slab comprising a profiled steel sheeting base and orthogonally arranged hat-shaped steel stiffeners. The slab exhibited high global load resistance, while the stiffeners provided only limited gains in ultimate capacity; nevertheless, they significantly suppressed transverse interfacial slip. Yi et al. [21] employed crumb rubber concrete (CRC) as the topping material for profiled steel sheeting composite slabs and, based on four-point bending tests, investigated the influence of material modification on flexural capacity, crack development behavior, and ductility. For profiled steel sheeting-hollow concrete composite slabs, Zhang et al. [22] and Zhu et al. [23] performed parametric studies to clarify the roles of hollow-core parameters and reinforcement layout. Zhang et al. additionally developed a data-driven prediction scheme combining ANN and decision trees to accelerate parametric assessment, whereas Zhu et al. introduced the “anchorage degree” concept and proposed flexural-capacity formulations under different anchorage conditions.

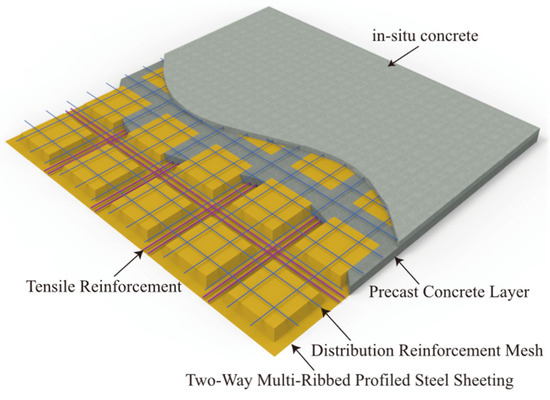

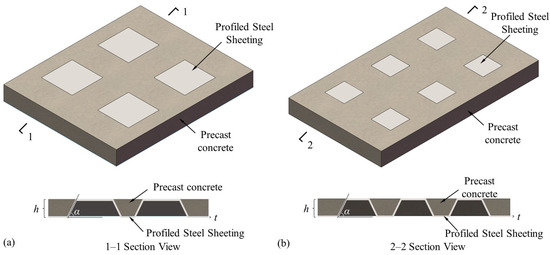

To combine the advantages of profiled steel sheeting composite slabs and multi-ribbed floor systems while satisfying the requirement for construction efficiency in industrialized building [24], a novel multi-ribbed profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite floor system (RPSCF) has been proposed for long-span heavy-load structures. The composite slab is formed by multi-ribbed profiled steel sheeting, concrete and reinforcing mesh (Figure 1). During the construction stage it behaves essentially as a one-way member, and for small shear-span ratios or relatively large concentrated loads its ultimate response is likely controlled by inclined-section shear. Despite the extensive work on flexural resistance, the vertical shear behavior of composite slabs remains insufficiently explored Girhammar et al. [25] combined experiments and analytical work to quantify the influence of the concrete topping in prestressed hollow-core slabs, showing that even with an untreated interface, the topping can increase the vertical shear capacity by 35%. Importantly, the composite system was governed by web shear-compression failure of the hollow-core unit rather than interface shear failure. Hegger et al. [26] investigated prestressed hollow-core slabs supported by flexible steel beams, conducted two-span full-scale floor tests, and evaluated the shear performance in comparison with rigid-support reference tests. The results showed that flexible supports reduced the shear capacity by about 60–70% compared with rigid supports. Rahman et al. [27] carried out a systematic assessment of the shear behavior of prestressed precast hollow-core slabs based on full-scale loading tests, indicating that ACI 318-05 [28] exhibits deviations in predicting the failure modes and shear capacity under different shear-span ratios, and proposed a modified model accounting for the effect of shear-span ratio. For profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slabs, Pereira et al. [29] used full-scale tests and numerical simulations and found the Eurocode 4 approach to be markedly conservative, primarily because it neglects the web contribution of profiled sheeting to vertical shear resistance. Xiang et al. [30] developed a capacity model for steel-ribbed steel-concrete composite bridge decks at small shear-span ratios by explicitly accounting for steel-concrete composite action, achieving improved representation of the influences of material properties, geometry, and interfacial interaction. In addition, based on transverse shear tests on cast-in-place circular-void hollow slabs, Shang et al. [31] identified the inter-void rib width and the top/bottom flange thicknesses as key parameters: rib-dominant horizontal shear failure occurs for small rib widths, whereas the governing mechanism shifts to flange-controlled shear as the rib width increases. For prestressed concrete composite hollow slabs, Wu et al. [32] reported a predominantly inclined-crack-induced shear-compression failure without interface-slip-controlled failure, and confirmed that longitudinal tube arrangement and precast ribbed bottom panels can effectively enhance the vertical shear capacity. Motivated by the lack of research on the vertical shear behavior and design methods for the shear capacity of multi-ribbed profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slabs, the present study conducts a systematic numerical parametric investigation into the effects of composite slab detailing parameters and shear-span ratio on the vertical shear capacity under one-way loading. A prediction method for the vertical shear capacity is developed and validated, providing a theoretical basis and reference for checking the vertical shear capacity of such slabs under short-term construction-stage conditions.

Figure 1.

RPSCF schematic diagram.

2. Finite Element Model

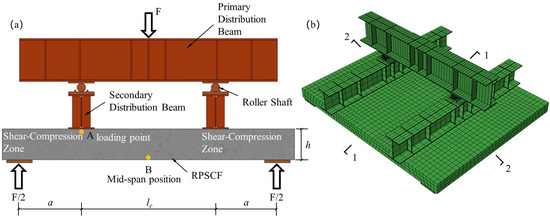

Four-point bending tests were simulated numerically to study the deformation and crack development in the bending-shear region of the novel profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slab during the construction stage. A finite element model of the novel multi-ribbed profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slab was developed in ABAQUS 2019. The multi-ribbed profiled steel sheeting was modeled using shell elements (S4R), whereas the concrete and the upper loading device were modeled using solid elements (C3D8R). The longitudinal reinforcement was represented by truss elements (T3D2), and the support bearing plate was idealized as a rigid body element (R3D4). The loading arrangement and mesh discretization of the finite element model are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Loading conditions and FE mesh of the multi-ribbed profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slab: (a) loading conditions; (b) finite element model with mesh discretization.

2.1. Material Properties

The profiled sheeting and reinforcing bars were assigned a bilinear kinematic hardening model, in which the hardening modulus was set to 1% of the elastic modulus [33]. with a Poisson’s ratio of 0.3 for the profiled sheeting and the reinforcement. The key material parameters for the concrete, profiled steel sheeting and reinforcement are summarized in Table 1. For concrete, the key material parameters considered in this study are the density, compressive elastic modulus Ec, axial compressive strength fc, axial tensile strength ft, and the peak strains εc0 and εt0 in compression and tension, respectively. A density of 2400 kg/m3 is used. The modulus Ec is evaluated using Equation (1) [34], while fc and ft are obtained from Equations (2) and (3) [35]:

where Ec is the compressive elastic modulus of concrete; fc is the axial compressive strength of concrete; fcu is the standard cube compressive strength of concrete, taken as 30 MPa; and ft is the axial tensile strength of concrete.

Table 1.

Mechanical properties of materials.

To accurately simulate the nonlinear response of concrete under complex loading, the constitutive model should be capable of representing both the evolution of concrete damage and the development of plastic deformation [36,37]. The concrete damaged plasticity (CDP) model can capture these two key mechanisms simultaneously, and its effectiveness has been validated in various engineering and mechanics problems [38,39]. Therefore, the CDP model is adopted in this study to simulate the nonlinear mechanical behavior of concrete.

The uniaxial compressive stress-strain relationship of concrete followed the constitutive relationship recommended in GB 50010-2010 [35], the compressive stress-strain curve consists of an ascending branch and a descending branch, as defined by Equations (4)–(6).

where αc is the shape parameter for the descending branch of the concrete uniaxial compressive stress-strain curve (taken as αc = 0.92); εc0 is the peak compressive strain of concrete, taken as 2000 με [34].

For uniaxial tension, a linear ascending branch is assumed. The tensile softening behavior is modeled following the recommendation of GB 50010-2010, and the corresponding ascending and descending branches are specified by Equations (7)–(9).

where αt is the shape parameter for the descending branch of the concrete uniaxial tensile stress-strain curve (taken as αt = 1.59); Et is the tensile elastic modulus of concrete (taken to be equal to the compressive elastic modulus); and εt0 is the peak tensile strain of concrete.

Within the CDP framework, the damage variable employed to quantify material degradation is evaluated using the Najar damage theory formulated via Gaussian-integration-based decomposition. The four plasticity parameters adopted to represent concrete behavior under biaxial and triaxial stress states are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Plasticity parameters of the CDP model.

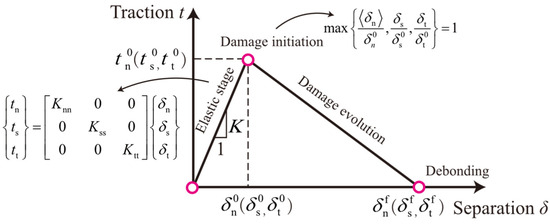

2.2. Interfacial Interaction and Constraints

To capture the interaction between profiled steel sheeting and concrete, a cohesive-Coulomb friction mixed interface model was adopted to represent both bond and friction at the steel-concrete interface. The normal and tangential cohesive responses were characterized by a bilinear traction-separation law, as shown in Figure 3. The peak normal and tangential tractions at the interface between the profiled steel sheeting and concrete are both taken as 0.3 MPa according to Eurocode 4, with the corresponding separation displacement of 0.056 mm [40]. The fracture energy Gc was calculated following the recommendation of CEB-FIP MC90 [41] (Equation (10)), and the friction coefficient between the profiled steel sheeting and concrete was taken as 0.3 based on literature [42]. The interface parameters adopted in the cohesive-Coulomb friction mixed model are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 3.

Bilinear traction-separation law for interface modeling.

Table 3.

Mechanical parameters of contact interface.

Full bond between the reinforcement and the surrounding concrete is assumed throughout loading. The reinforcement-concrete interaction is modeled using the embedded constraint, ensuring composite action in terms of both force transfer and deformation compatibility.

2.3. Boundary Conditions and Loading Scheme

To reproduce the test support conditions, bearing pads were introduced in the support zones and tied to the corresponding areas of the end profiled steel sheeting. A simply supported boundary was implemented by defining a reference point at the geometric center of each bearing pad, where the vertical translational degree of freedom was constrained and the relevant horizontal and rotational degrees of freedom were released to allow the required in-plane motions and rotations. Loading was applied under displacement control: a coupled reference point was created at the midspan region of the primary loading beam, where a prescribed vertical displacement was imposed to represent the jack action. In addition, the secondary distribution beam was tied to the composite slab surface.

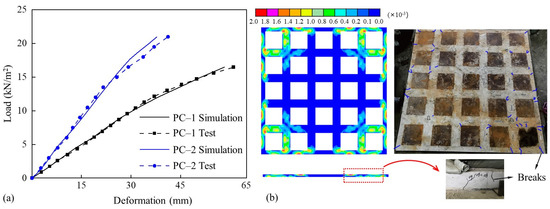

2.4. Validation of the Finite Element Model

Numerical simulations were conducted on specimens labeled PC–1 and PC–2 from the authors’ previous experiment [43], and the comparison are shown in Figure 4. Figure 4a presents the load-deformation curves of the specimens, demonstrating that the stiffness and load-bearing capacity of the RPSCF obtained from the numerical simulation are in agreement with the experimental results. Figure 4b presents the distribution of the maximum principal plastic strain in the concrete of specimen PC–1 at the ultimate load. It can be observed that the concentrated regions of principal plastic strain at the slab top and slab side in the finite element model are highly consistent with the crack distribution observed in the experiment. The above comparison validates the accuracy of the numerical model.

Figure 4.

Comparison between simulation result and test: (a) load-deformation curves; (b) failure mode.

3. Response Characteristics of a Typical Specimen in Vertical Shear

3.1. Load-Displacement Curves and Internal Force Analysis

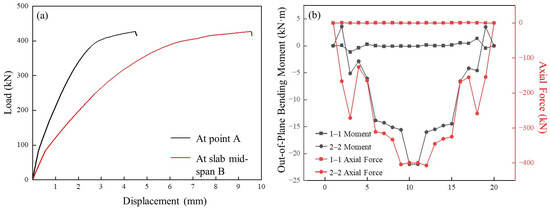

A representative slab with a thickness of 150 mm and a bending-shear region length of = 225 mm was selected for detailed discussion. The load-displacement curves at the loading points and at mid-span are plotted in Figure 5. Under the four-point loading configuration, the response of the slab can be divided into four stages (Figure 5a): initial elastic, elastic-plastic, plastic and failure. The linear-elastic Stage I is short because the bond along the interface between the profiled steel sheeting and the concrete is mainly provided by chemical adhesion, and the associated bond strength is limited. As the load increases, micro-cracks form at the steel-concrete interface, and the slab enters elastic-plastic Stage II, which is the primary load-bearing stage. In this stage the slab exhibits relatively high flexural stiffness, which guarantees adequate load-carrying capacity and stability during the construction stag. Once the profiled steel sheeting reaches yield, the response enters Stage III, in which stiffness degrades markedly while plastic deformation continues to accumulate, but large plastic deformations continue to develop. Approximately 50% of the total plastic deformation prior to failure occurs in this stage, indicating that the slab has favorable plastic behavior and ductility for resisting accidental loads. In failure Stage IV, the load-carrying capacity drops and concrete compression crushing occurs, while the profiled steel sheeting and concrete both reach full utilization of their material capacities. To examine the internal-force distribution at the ultimate limit state, twenty points were uniformly selected along the 1–1 and 2–2 axes shown in Figure 2b. The distributions of axial force and bending moment obtained from the finite element analysis are plotted in Figure 5b. The bending moments and axial forces along axis 1–1 are much larger than those along axis 2–2, confirming that the slab behaves mainly as a one-way member. This agreement with the expected mechanical behavior indicates that the finite element model can accurately reproduce the structural response of the novel profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slab under four-point bending.

Figure 5.

Response of the novel multi-ribbed profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slab under loading: (a) load–displacement curves measured at the loading point and at mid-span; (b) evolution of sectional forces along lines 1–1 and 2–2.

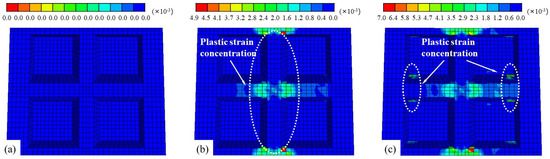

Figure 6 shows the evolution of plastic strain in the profiled steel sheeting during the elastic, elastic-plastic, and plastic stages. In the elastic stage, the sheeting remains fully elastic and acts compositely with the concrete, defined as Stage I. After the slab enters Stage II, the profiled sheeting still does not yield; the observed nonlinear response is primarily attributed to bond-slip at the steel-concrete interface. As the load increases, yielding initiates in the sheeting, with plastic strain first accumulating near mid-span. At the transition between Stages II and III, plastic strain is mainly concentrated at the bottom of the mid-span sheeting, as indicated in Figure 6b. Continued loading causes the plastic region to extend toward the bending-shear zone, where the inclined ribs begin to yield, as shown in Figure 6c. These results indicate that the bottom sheeting at mid-span carries the bending-induced tensile stresses, whereas the inclined ribs within the bending-shear zone provide significant shear resistance. The shear failure mode of the novel composite slab in the bending-shear region is closely related to these structural characteristics, and will be discussed in detail in Section 4.

Figure 6.

Development of plasticity in the profiled steel sheeting: (a) plastic strain distribution in the elastic stage; (b) plastic strain distribution in the elastic-plastic stage; (c) plastic strain distribution in the plastic stage.

3.2. Crack Development and Interface Damage Analysis

Figure 7 shows the evolution of equivalent plastic tensile strain in concrete during different loading stages. In the early stage, plastic tensile strain develops in the concrete adjacent to the steel-concrete interface (Figure 7a) because this region experiences tension under bending. The bond between the concrete and the profiled steel sheeting transfers the tensile force from the mid-depth concrete to the profiled steel sheeting, but this bond is mainly provided by the adhesion of the cementitious paste, which has relatively low strength and stiffness. Therefore, the plastic tensile strain in concrete at this stage is limited to approximately 0.5 times the cracking strain, and no cracks develop. Due to the relatively low bond strength between the concrete and the profiled steel sheeting, microcracks initiate along the interface as the load increases, signaling the transition from the elastic stage to elastic-plastic Stage II. As the load continues to increase, the plastic tensile strain continues to accumulate and eventually leads to crack initiation near the fillet region (Figure 7b). The underlying reason is that with increasing slab deformation, the relative slip of the bond interface results in local stress concentration near the fillet, where cracks first occur. The progressive weakening of the bond strength between the concrete and the profiled steel sheeting further aggravates crack propagation, reducing the stiffness of the novel composite slab. With continued loading, the bond deterioration between the concrete and the profiled steel sheeting becomes more severe on both sides of the composite slab, and debonding occurs at the interface. The composite action gradually diminishes, leading to reduced shear resistance in the bending-shear region. As a result, oblique cracks form in the concrete (Figure 7c), and the novel composite slab eventually exhibits inclined-section shear failure.

Figure 7.

Development of concrete cracking: (a) concrete plastic-strain distribution at the beginning of the elastic-plastic stage; (b) concrete crack pattern during the plastic stage; (c) concrete crack pattern at failure.

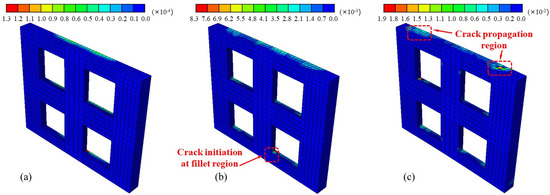

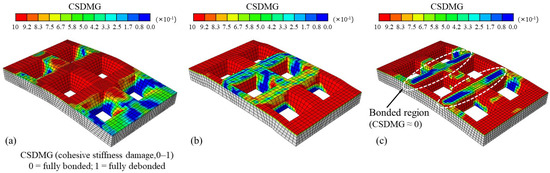

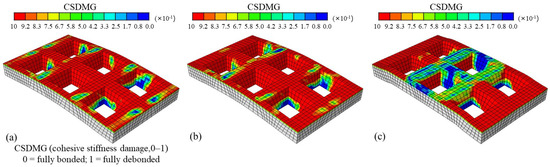

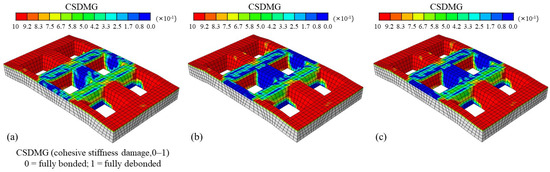

To clarify the evolution of composite action between the concrete and the profiled steel sheeting at different loading stages, the interface behavior was characterized using a cohesive model, and contour plots of the cohesive stiffness damage variable (CSDMG) were extracted. CSDMG = 0 denotes an intact bond and full composite action between the two materials (Figure 8, blue regions), while CSDMG = 1 corresponds to complete debonding (Figure 8, red regions). In the initial elastic stage, the concrete is firmly attached to the profiled steel sheeting, and the composite slab responds in a linear-elastic manner. When the applied load reaches about 80 kN, bond deterioration initiates at the concrete-steel interface, and local debonding appears around the inclined ribs in the central region of the slab (Figure 8b, dashed ellipse). Beyond this point, the global deformation response gradually deviates from linearity, although most of the interface remain in contact and the slab retains sufficient stiffness in the ensuing elastic-plastic stage. As the load further increases from 80 kN to 380 kN, the slab predominantly operates in this elastic-plastic regime. The debonded areas between the concrete and the profiled steel sheeting progressively expand with increasing load, and upon entering the plastic stage, almost the entire interface is debonded except for the compressed zone near mid-span (Figure 8c, red regions). The resulting significant interfacial slip causes a redistribution of internal forces and improves the deformability of the slab, giving rise to a pronounced yield plateau in the global response and a clear ductile failure behavior.

Figure 8.

Damage contours of the cohesive stiffness at the concrete-profiled steel sheeting interface (CSDMG): (a) elastic stage; (b) elastic-plastic stage; (c) plastic stage.

4. Effect Analysis of Geometric Parameters on Vertical Shear Performance

To quantify the effects of key detailing parameters and shear-span ratio on the mechanical response of the novel profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slab, two slabs specimens with n = 4 and n = 6 embossments were designed, as shown in Figure 9. The parametric study in this section focuses on the profiled sheeting thickness t, embossment height h, inclination angle of the inclined rib plate α, and reinforcement ratio ρ.

Figure 9.

Multi-ribbed profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slab and its main structural configuration parameters: (a) slab specimen with n = 4 embossments; (b) slab specimen with n = 6 embossments.

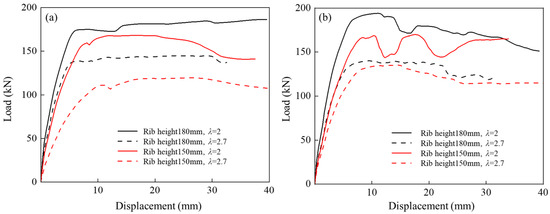

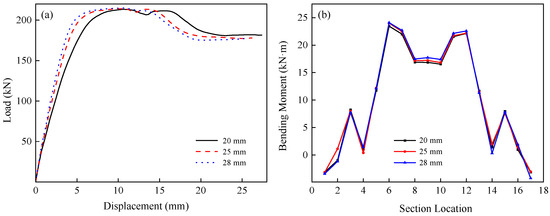

4.1. Shear-Span Ratio Effects

Composite slab specimens were designed with numbers of embossments n = 4 and n = 6 and embossment heights h = 150 mm and h = 180 mm. Numerical simulations were carried out for two shear-span ratios, λ = 2 and λ = 2.7, and the corresponding load-displacement responses are plotted in Figure 10 for different combinations of structural parameters. The slabs display a consistent response to changes in shear-span ratio: at λ = 2.7, the ultimate load and initial stiffness (Figure 10, dashed curves) are clearly lower than those at λ = 2 (Figure 10, solid curves), with reductions of approximately 20% and 40%, respectively. This behavior arises because an increased shear-span ratio elongates the shear-transfer path and weakens the compression arching action, so that the load-transfer mechanism evolves from a combined compression-arch-truss mechanism to one governed by flexure. The accompanying increase in the length of the equivalent diagonal compression strut and the reduction in the compressed concrete area further diminish the shear capacity and overall stiffness. At a fixed shear-span ratio, the slab with a larger embossment height of h = 180 mm (Figure 10, black solid curve) develops greater initial stiffness and ultimate load than the slab with h = 150 mm, indicating that increasing the embossment height is effective in improving the vertical shear resistance of the composite slab.

Figure 10.

Load-displacement curves of the profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slab for different shear-span ratios: (a) embossment number n = 4; (b) embossment number n = 6.

To gain further insight into the influence of shear-span ratio on the response mechanism of the composite slab, a multi-ribbed profiled steel sheeting-concrete slab with n = 4 embossments and an embossment height of h = 150 mm is selected, and its failure modes at different shear-span ratios are compared. The crack patterns in the concrete are characterized by contours of equivalent plastic tensile strain (Figure 11). When λ = 2.7, the peak plastic tensile strain occurs in the mid-span region and the slab fails predominantly in flexure (Figure 11a, dashed rectangle). When λ = 2, pronounced diagonal cracking develops in the bending-shear region of the composite slab, indicating a shear-type failure mode (Figure 11b, dashed ellipse). Hence, the shear-span ratio influences not only the shear resistance and stiffness of the composite slab, but also the shift of its governing failure mode from flexure to shear.

Figure 11.

Failure modes of the profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slab under different shear-span ratios: (a) λ = 2.7; (b) λ = 2.

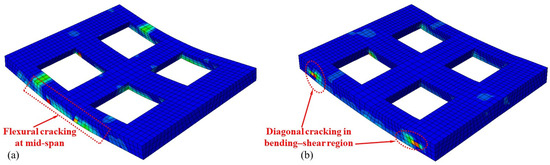

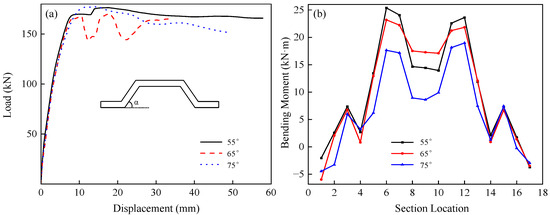

4.2. Profiled Steel Sheeting Rib Inclination Angle Effects

The effect of the inclined rib plate angle on the shear capacity of the composite slab was studied using the multi-ribbed profiled steel sheeting-concrete slab with embossment number n = 6 as the baseline configuration. A parametric series of three specimens was produced by varying only α (55°, 65°, and 75°), and the corresponding load-displacement and internal force curves are plotted in Figure 12. Figure 12a shows that changing α within 55–75°has little influence on the ultimate shear resistance or global stiffness of the slabs, indicating that the overall shear performance is insensitive to the rib angle in this range. However, α markedly affects the internal force distribution at ultimate. The maximum bending moments occur at approximately one-third and two-thirds of the span and decrease sharply as α increases; at α = 75°, the peak moment is about 40% lower than at α = 55° (Figure 12b). This trend is attributed to the deterioration of composite action between the profiled sheeting and the concrete with increasing α, which reduces the sectional load-carrying capacity. Because debonding at the steel-concrete interface primarily develops during the plastic stage, the initial stiffness is only marginally affected by the rib angle. For all rib inclinations, the slabs exhibit a similar shear-compression failure mode, characterized by yielding of the profiled sheeting and reinforcement and by the concrete reaching its ultimate strength under combined shear and compression. Hence, the rib inclination angle has no appreciable effect on the ultimate load-carrying capacity of the composite slab.

Figure 12.

Mechanical behavior of the profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slab with different inclined-rib angles α: (a) load-displacement curves; (b) sectional bending-moment curves.

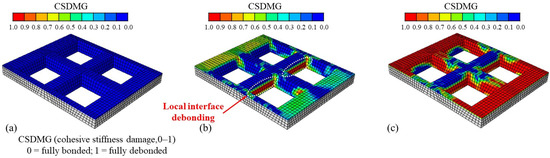

To further interpret the effect of α on the concrete-steel composite action, interface cohesive stiffness-damage contours are plotted in Figure 13. Increasing α progressively enlarges the damaged zones, indicating that a larger rib angle significantly weakens the steel-concrete interaction. At α = 75°, the profiled sheeting is essentially fully debonded from the concrete except in the stiff regions around L/3 and 2L/3 of the span (Figure 13c, dashed ellipse). Accordingly, to ensure reliable composite action, α of the profiled steel sheeting should be kept below 65°.

Figure 13.

Damage contours of the cohesive stiffness at the concrete-profiled steel sheeting interface (CSDMG) for different rib inclination angles α: (a) α = 55°; (b) α = 65°; (c) α = 75°.

4.3. Profiled Steel Sheeting Thickness Effects

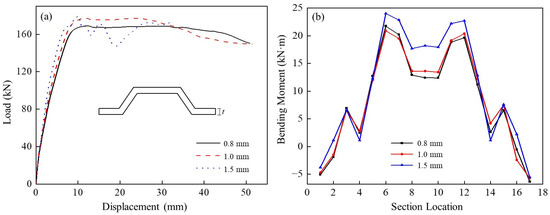

Figure 14 shows the effect of profiled steel sheeting thickness t on the behavior of the composite slab. Increasing t leads to a higher initial stiffness and a modest increase in ultimate load capacity (Figure 14a). The sectional internal forces are positively related to the sheeting thickness: as indicated in Figure 14b, the maximum bending moment grows with increasing thickness, and the growth in internal forces is approximately proportional to the increase in thickness. These results indicate that the profiled sheeting can fully participate in resisting the sectional forces of the composite slab, and that an increased sheeting thickness enhances the flexural resistance and stiffness of the section.

Figure 14.

Structural behavior of profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slabs with different profiled sheeting thicknesses t: (a) load-displacement curves; (b) curves of sectional bending-moment variation.

Figure 15 presents cohesive stiffness-damage contours at the steel-concrete interface for various profiled sheeting thicknesses. As the thickness t increases, the composite action between the profiled sheeting and the concrete becomes progressively stronger. This is because a thicker sheeting leads to a stiffer composite slab, which provides better deformation compatibility between the two materials and effectively reduces the tendency for interface debonding.

Figure 15.

Damage contours of the cohesive stiffness at the concrete-profiled steel sheeting interface (CSDMG) different profiled sheeting thicknesses t: (a) t = 0.8 mm; (b) t = 1.0 mm; (c) t = 1.5 mm.

4.4. Longitudinal Reinforcement Ratio Effects

The influence of longitudinal reinforcement ratio on the shear behavior of the composite slab was studied by changing the bar diameter d and comparing the responses of multi-ribbed profiled steel sheeting-concrete slabs with different reinforcement ratios (Figure 16). As the longitudinal reinforcement ratio increases, the overall stiffness of the composite slab increases, whereas the ultimate load-carrying capacity remains almost unchanged (Figure 16a). This reflects the role of the longitudinal bars in improving the concrete stress state and delaying cracking in the tensile zone, thereby enhancing the initial stiffness. However, the multi-ribbed profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slab mainly resists load through the profiled sheeting and the concrete, and failure is characterized by yielding of the profiled sheeting, followed by the concrete in the shear-compression zone reaching its ultimate strength. As a result, within the range of reinforcement considered, the longitudinal reinforcement does not govern the ultimate capacity of the slab. The internal-force diagrams of the composite section corroborate this conclusion (Figure 16b): the ultimate bending moment of the section is virtually insensitive to changes in longitudinal reinforcement ratio, indicating that the longitudinal reinforcement has only a minor effect on the ultimate load-carrying capacity of the composite slab.

Figure 16.

Effect of longitudinal reinforcement ratio on the structural behavior of multi-ribbed the profiled sheeting-concrete composite slab: (a) load-displacement curves; (b) bending-moment variation along the section.

Figure 17 shows cohesive stiffness-damage contours along the concrete-steel interface for composite slabs with different longitudinal reinforcement ratios. At ultimate state, the slabs display essentially the same damage pattern: interface debonding develops at the two ends, whereas the concrete and profiled sheeting remain well bonded at mid-span. Hence, within the range of longitudinal reinforcement ratios considered, the longitudinal reinforcement has only a minor influence on enhancing the interface composite action between the profiled sheeting and the concrete.

Figure 17.

Damage contours of the cohesive stiffness at the concrete-profiled steel sheeting interface (CSDMG) for different longitudinal reinforcement ratios: (a) d = 20 mm; (b) d = 25 mm; (c) d = 28 mm.

Overall, the construction-stage vertical shear resistance of the novel multi-ribbed profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slab is governed by two coupled aspects: (i) a shear-span-ratio-driven shift in the load-transfer mechanism and (ii) progressive degradation of steel-concrete composite action. At relatively small shear-span ratios, the slab can still develop a stable arch-truss mechanism within the flexure-shear zone, allowing the inclined ribs to effectively transmit shear; consequently, concrete shear-compression tends to dominate the failure. Due to the distinctive geometry of multi-ribbed sheeting, the rib contribution to vertical shear capacity deviates from that of conventional profiled steel sheeting-concrete slabs. Parametric finite-element results further show that increasing the slab depth and sheeting thickness improves the capacity by enlarging the equivalent shear-resisting area, whereas an overly large rib inclination angle promotes interface debonding and diminishes composite action. Accordingly, key geometric variables (rib height, rib spacing, and rib inclination angle) should be incorporated as key variables to more accurately reflect the vertical shear performance of the composite slab.

5. Theoretical Model for Calculating the Vertical Shear Capacity

Current design approaches for composite slabs are predominantly flexure-oriented, while methods for evaluating their vertical shear resistance have received comparatively little attention. However, any variation in bending moment within a slab is inevitably accompanied by shear. In the construction stage, a multi-ribbed profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slab supported on beams behaves as a one-way member; because the slab remains relatively thin before the topping concrete is placed, it is susceptible to inclined-section shear failure in the support regions, making verification of its vertical shear resistance in these regions essential. Accordingly, this section develops a shear-transfer-based mechanical model for the composite slab and formulates a calculation method for its vertical shear capacity applicable to the construction stage under one-way loading conditions.

5.1. Theoretical Model for Analysis

A shear-resistance model for the multi-ribbed profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slab is formulated on the basis of a strength-equivalence approach (Figure 18). The top and bottom flanges of the profiled sheeting are modeled as longitudinal tension reinforcement and the inclined ribs as shear stirrups. For conservatism, the equivalent areas of the longitudinal reinforcement and stirrups in the composite slab are evaluated by the following formulas:

Figure 18.

Configuration of the multi-ribbed profiled sheeting-concrete composite slab and its equivalent model.

In the above formulas, represents the cross-sectional area of the rib in the profiled steel sheeting. For conservatism, can be approximated by the product of the sheeting thickness t and half the slab width b, namely . is the area of the longitudinal reinforcement, whereas and denote the areas of the equivalent longitudinal bars and equivalent stirrups, respectively. denotes the inclination angle of the inclined ribs of the profiled sheeting. The spacings of the equivalent stirrups is related to the size of the embossments in the profiled sheeting as follows:

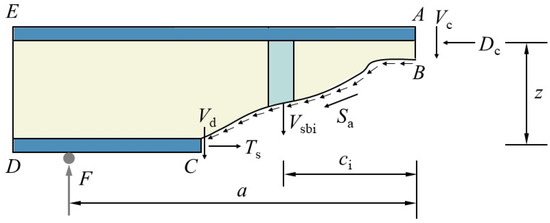

Because of the embossments formed in the profiled steel sheeting, the effective concrete width is taken, in approximation, as half of the actual slab width. Concrete is strong in compression but weak in tension; once the maximum principal tensile stress in the shear-span region of the slab exceeds its tensile strength, inclined cracking occurs. The formation of such inclined cracks causes a redistribution of stresses over the section. To examine the force transfer, a pentagonal free body ABCDE (Figure 19) is isolated. The resistance along the inclined section is provided by: the compressive force Dc and shear force Vc acting on the concrete compression-shear face AB; the tensile force Ts in the longitudinal bars; the friction and aggregate interlock force Sa mobilized along the two crack faces due to their relative shear displacement; the shear component Vd taken by the equivalent longitudinal reinforcement as a result of the vertical offset of the concrete across the crack; and the shear force Vsb carried by the equivalent stirrups.

Figure 19.

Free-body diagram of the separated block after the formation of the inclined crack.

Because the aggregate interlock force Sa and the dowel shear force Vd provided by the longitudinal bars are hard to evaluate accurately and change with crack development, they are regarded as a reserve of safety in the shear resistance of the composite slab and are therefore neglected in the calculation. Under this assumption, the following equilibrium equation is obtained:

In Equation (14), F denotes the shear capacity of the inclined section of the composite slab. This capacity is the sum of the shear force Vc carried by the concrete along the compression-shear face AB and the contribution Vsb from the profiled steel sheeting,

The concrete contribution Vc depends on the shear-span ratio λ the concrete strength, and the cross-sectional dimensions of the slab, and is evaluated as

where is the shear-span ratio. When λ < 1.5, λ is taken as 1.5, and when λ > 3, λ is taken as 3. is the tensile strength of concrete, and is the effective flange width. Because embossments are provided on the multi-rib profiled sheeting of the composite slab, can be approximated as one half of the actual slab width (), with b and h denoting the slab width and thickness, respectively.

The shear resistance Vsb provided by the profiled sheeting is governed by the steel area and the inclination angle of the embossed web. After converting this contribution into an equivalent stirrup, the vertical shear capacity is obtained from

where is the yield strength of the profiled sheeting, is the area of the equivalent stirrup calculated from Equation (12), and s is the spacing of the equivalent stirrup given by Equation (13).

The vertical shear capacity of the composite slab can also be obtained from the resultant moment of the equivalent longitudinal tensile reinforcement and the equivalent tensile stirrups, namely,

in which is the distance from the support to the resultant compressive force in the concrete shear-compression zone. For a mildly conservative estimate, is conservatively taken as the distance between the support and the load application point (). Under this assumption, and , where is the depth of the concrete compression zone and is the diameter of the equivalent longitudinal reinforcement.

Accordingly, the shear capacity of the composite slab is taken as

5.2. Validation Against Finite Element Results and Applicability

To assess the accuracy of the vertical shear-capacity equation proposed for the novel composite slab, the finite-element results for the specimens failing in inclined-section shear were used to compute the theoretical shear capacities, which were then compared with the FE predictions. Details of the specimen configurations are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Configuration parameters of multi-rib profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slabs.

Table 5 compares the theoretical vertical shear capacities of the multi-ribbed profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slabs with the finite-element results for various structural parameters. The relative error between the two is within 15%, and most theoretical values fall below the numerical predictions, implying a generally conservative estimate. Hence, the proposed approach can be recommended adopted for design checks of the vertical shear capacity of multi-ribbed profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slabs under uniaxial loading in the construction stage.

Table 5.

Comparison of numerical and theoretical results.

6. Conclusions

At the construction stage, the novel multi-ribbed profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slab may experience large concentrated loads and may operate with a small shear-span-to-depth ratio, making it susceptible to inclined web-shear failure. Consequently, a reliable evaluation of its vertical shear capacity is essential for construction-stage safety. Yet, existing work on the shear behavior of multi-ribbed profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slabs is still limited, and no generally accepted formula is available for their vertical shear capacity. This study systematically examined how the geometric parameters of the ribbed profiled sheeting and the shear-span-to-depth ratio affect the vertical shear capacity and proposed a calculation procedure for the construction-stage vertical shear capacity of the new slab, which was subsequently validated. The results provide a useful basis for design checks of the vertical shear capacity of this composite system. The main conclusions are:

- (1)

- The load-carrying process of the novel multi-ribbed profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slab can be divided into four stages. The purely elastic stage is short, followed by a long elastic-plastic stage with high stiffness, which guarantees adequate load-carrying capacity and stability. Approximately 50% of the total plastic deformation is accumulated in Stage III ensuring ductility and robustness under accidental actions. In the final failure stage, the strengths of both the profiled sheeting and the concrete are effectively mobilized.

- (2)

- The effects of the stress state on the failure mode and load-carrying capacity of the multi-ribbed profiled steel sheeting-concrete composite slab were examined. As the shear-span ratio increases, the concrete compression zone becomes smaller. For slabs with identical configurations, increasing the shear-span ratio from 2 to 2.7 leads to reductions of about 40% in initial stiffness and about 20% in vertical shear capacity.

- (3)

- Parametric analyses were carried out on the rib inclination angle and thickness of the multi-ribbed profiled sheeting and on the longitudinal reinforcement ratio. Increasing the rib inclination angle α weakens the composite interaction between the profiled sheeting and the concrete, and the maximum bending moment of the slab at α = 75° is approximately 40% lower than that at α = 55. Increasing the thickness of the profiled sheeting and the slab depth enhances the load-carrying capacity and stiffness of the composite slab. Introducing a moderate longitudinal reinforcement ratio improves the internal stress state of the concrete and increases the initial stiffness.

- (4)

- A strength-equivalent analytical model for the vertical shear capacity of the new composite slab was developed and calibrated against finite-element simulations over a wide range of structural parameters. Theoretical predictions agree with the numerical results within 15% and are generally lower than the numerical capacities, indicating that the proposed vertical shear-capacity equation is both accurate and mildly conservative for design applications. It should be noted that the proposed calculation method for the vertical shear capacity has been primarily validated against numerical results, and its accuracy still requires further examination through subsequent experimental studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.H.; Methodology, K.H.; Software, K.H.; Formal analysis, K.H.; Investigation, K.H. and Y.W.; Data curation, K.H.; Writing—original draft, K.H.; Supervision, G.S.; Funding acquisition, G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tan, M.; Wu, Y.; Pan, W.; Liu, G.; Chen, W. Optimal Design of a Novel Large-Span Cable-Supported Steel-Concrete Composite Floor System. Buildings 2024, 14, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Zhang, X.; Xia, Z.; Shi, H.; Deng, X.; Chen, X.; Mao, X.; Wang, J. Construction process monitoring of a large-span steel truss roof based on response-increment comparison strategy. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 025001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favarato, L.F.; Gomes, A.V.S.; de Moura Candido, D.C.; Ferrareto, J.A.; Vianna, J.d.C.; Calenzani, A.F.G. On the composite behavior of a rebar truss ribbed slab with incorporated shuttering made of lipped channel section. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 55, 104663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candido, D.C.d.M.; Gomes, A.V.S.; Favarato, L.F.; Ferrareto, J.A.; Vianna, J.d.C.; Calenzani, A.F.G. Flexural behavior of composite ribbed slabs employing cold-formed steel lipped channels. Eng. Struct. 2024, 298, 117070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.; Sakha, M.; Hassan, Z.; Manshadi, B.; Wang, X.; Fan, H.; Dillenburger, B.; Shahverdi, M. Flexural behavior of stay-in-place load-bearing 3D-printed concrete formwork for ribbed slabs. Eng. Struct. 2025, 338, 120531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Guo, X.; Kang, J.; Duan, M.; Wang, Y. Numerical and theoretical research on flexural behavior of steel-UHPC composite beam with waffle-slab system. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2020, 171, 106141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsanadedy, H.; Al Kallas, A.; Abbas, H.; Almusallam, T.; Al-Salloum, Y. Capacity reinstatement of reinforced concrete one-way ribbed slabs with rib-cutting shear zone openings: Hybrid fiber reinforced polymer/steel technique. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2024, 27, 2521–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, S.; Zohrevand, P.; Mirmiran, A.; Xiao, Y.; Mackie, K. A super lightweight UHPC-HSS deck panel for movable bridges. Eng. Struct. 2016, 113, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladzic, V.; Kekanovic, M.; Milicic, I. Traditional Thick Concrete Floor Slabs—An Obstacle to the Flexibility, Energy Efficiency and Seismic Safety. Teh. Vjesn.-Tech. Gaz. 2019, 26, 1794–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Feng, Y.; Ruan, S.; Xu, M.; Gong, L. Experimental and Numerical Study on Flexural Behavior of a Full-Scale Assembled Integral Two-Way Multi-Ribbed Composite Floor System. Buildings 2023, 13, 2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, T.; Burger, J.; Mata-Falcon, J.; Kaufmann, W. Structural design and testing of material optimized ribbed RC slabs with 3D printed formwork. Struct. Concr. 2023, 24, 1932–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alali, A.A.; Tsavdaridis, K.D. Experimental investigation on flexural behaviour of prefabricated ultra-shallow steel concrete composite slabs. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2024, 217, 108632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Shaji, A.; Menon, D.; Prasad, A.M. Experimental study on two-way prototype GFRG-RC floor slab systems. Structures 2025, 71, 108061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.Y.; Xiong, F.; Liu, Y.; Yu, M.J. Study on the flexural behavior of precast concrete multi-ribbed sandwich slabs under different boundary conditions. Eng. Struct. 2023, 291, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.G.; Wang, J.J.; Gou, S.K.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Fan, J.S. Technological development and engineering applications of novel steel-concrete composite structures. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2019, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, B.L.; Li, Y.R.; Becque, J.; Zheng, Y.Y.; Fan, S.G. Axial compressive behavior of circular stainless steel tube confined UHPC stub columns under monotonic and cyclic loading. Thin-Walled Struct. 2025, 208, 112830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdi, Y.; Hsu, C.T.T.; Zarei, M. Finite element analysis of new composite floors having cold-formed steel and concrete slab. Eng. Struct. 2014, 77, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, P.T.; Jeung-Hwan, D.; Sam, F.; Ho, N.M.; Tim, P. Numerical modeling techniques and investigation into the flexural behavior of two-way posttensioned concrete slabs with profiled steel sheeting. Struct. Concr. 2023, 24, 2674–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, P.T.; Doh, J.H. Experimental study and numerical modelling of post-tensioning systems on the transverse direction of composite steel deck-concrete structures. Structures 2024, 70, 107881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, K.; Ashraf, M.; Weiss, M.; Al-Ameri, R. Experimental study and numerical modelling of a novel two-way steel-concrete composite slab. Structures 2023, 57, 105096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, O.; Mills, J.E.; Zhuge, Y.; Ma, X.; Gravina, R.J.; Youssf, O. Performance of crumb rubber concrete composite-deck slabs in 4-point-bending. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 40, 102695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Jiao, J.; He, M.; Tao, Z.; He, P. Design, implementation and performance prediction of profiled steel sheet-mixed aggregate recycled concrete hollow composite slab. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 79, 107839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y. Research on the Flexural Behavior of Profiled Steel Sheet-Hollow Concrete Composite Floor Slab. Buildings 2025, 15, 2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, B.L.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, M.Y.; Zheng, X.F.; Fan, S.G. Experimental study on the eccentric compressive behavior of steel reinforced concrete composite columns with stay-in-place ECC jacket. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 102, 112007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girhammar, U.A.; Pajari, M. Tests and analysis on shear strength of composite slabs of hollow core units and concrete topping. Constr. Build. Mater. 2008, 22, 1708–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegger, J.; Roggendorf, T.; Kerkeni, N. Shear capacity of prestressed hollow core slabs in slim floor constructions. Eng. Struct. 2009, 31, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.K.; Baluch, M.H.; Said, M.K.; Shazali, M.A. Flexural and Shear Strength of Prestressed Precast Hollow-Core Slabs. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2012, 37, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACI 318-05; Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete and Commentary. American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2005.

- Pereira, M.; Simoes, R. Contribution of steel sheeting to the vertical shear capacity of composite slabs. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2019, 161, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, D.; Liu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Xu, X. Vertical shear capacity of steel-concrete composite deck slabs with steel ribs. Eng. Struct. 2022, 262, 114396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, R.; Jiang, F. Experimental study on shear capacity of cast-in-situ concrete hollow floor in transverse direction. J. Build. Struct. 2015, 36, 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.; Liu, B.; Luo, J. Experimental Study on Shear Resisting Properties of Prestressed Concrete Composite Hollow Core Slabs. Eng. Mech. 2016, 33, 196–203. [Google Scholar]

- Han, L.H. Concrete-Filled Steel Tube Structures; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mander, J.B.; Priestley, M.J.N.; Park, R. Theoretical Stress-Strain Model for Confined Concrete. J. Struct. Eng. 1988, 114, 1804–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50010-2010; Code for Design of Concrete Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2010.

- Yu, S.; Sun, Z.; Yu, J.; Yang, J.; Zhu, C. An improved meshless method for modeling the mesoscale cracking processes of concrete containing random aggregates and initial defects. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 363, 129770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Ren, X.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Z. Simulating the chemical-mechanical-damage coupling problems of cement-based materials using an improved smoothed particle hydrodynamics method. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e02018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.H.; Tan, K.H.; Kanda, T. Investigations on web-shear behavior of deep precast, prestressed concrete hollow core slabs. Eng. Struct. 2019, 183, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuberger, Y.M.; Andrade, M.V.; de Sousa, A.M.D.; Bandieira, M.; da Silva Junior, E.P.; dos Santos, H.F.; Catoia, B.; Bolandim, E.A.; Aquino, V.B.d.M.; Christoforo, A.L.; et al. Numerical Analysis of Reinforced Concrete Corbels Using Concrete Damage Plasticity: Sensitivity to Material Parameters and Comparison with Analytical Models. Buildings 2023, 13, 2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1994-2; Eurocode 4: Design of Composite Steel and Concrete Structures—Part 2: General Rules and Rules for Bridges. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- Euro-International Committee for Concrete. CEB-FIP Model Code 1990: Design Code; Thomas Telford Services Ltd.: London, UK, 1993; ISBN 0-7277-1696-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, B.L.; Zheng, X.F.; Fan, S.G.; Chang, Z.Q. Behavior and design of concrete filled stainless steel tubular columns under concentric and eccentric compressive loading. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2024, 213, 108319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.Y. Theoretical and Experimental Research on Bending Performance of Composite Slab with New Type Two-Way Multi-ribbed Steel Sheet. Master’s Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.