Abstract

Bullfighting in the bullrings of the Iberian Peninsula, with its most direct antecedent in the Roman amphitheatre, represents an established tradition that has been exported to the Americas. Bullfighting in Portugal shares general aspects with the bullfighting culture in neighbouring Spain. However, in Portugal, particular aspects are present: there is a preference for horseback bullfighting (cavaleiros) and forcados (a special type of bullfighting), and the bull is not killed in the ring. In this work, the authors aim to contribute to the acoustic narrative of bullfighting by linking architecture with the sounds of voice, environment, music, and silence that manifest in the emblematic Campo Pequeno bullring in Lisbon, thereby providing valuable information regarding its unknown intangible acoustic heritage. The presence of a mobile roof increases the number of reflections in the bullring, leads to a more linear energy decay, and prevents the acoustic inconveniences of roofless performance venues. The 3D impulse response measurements enable an overall monaural parametric analysis, together with the analysis of the distribution of sound energy in the time–frequency domain of early reflections, to determine the acoustic signature of the venue complemented with the direction of arrival of these early reflections.

1. Introduction

The safeguarding of acoustic heritage was pioneered by Gerzon [1] through the systematic recording of three-dimensional (3D) impulse response measurements with compact microphones [2,3] and was continued with the acoustic study of historical places by Brezina [4], Farina et al. [5,6], Katz et al. [7], and, more recently, by Almagro-Pastor et al. [8], among others. Many of these historical venues are open-air places, such as Greek and Roman theatres of Antiquity, Roman amphitheatres, and palace courtyards, for which analysis methods of room acoustics and soundscape have been combined [9,10,11]. A considerable body of literature has investigated the acoustics of classical theatres for practical and scientific interest, including virtual acoustics, in which the scattering and diffraction from the sharp edges of the stone seats in an open-air theatre play a major role in the acoustics, as opposed to roofed theatres where such scattering and diffraction are masked by roof reflections [12]. Furthermore, the ERATO project focuses [13] on the dissemination of the acoustics of classical theatres.

Once part of the Roman Empire, the Iberian Peninsula owes its bullfighting origins to ancient Roman traditions performed in amphitheatres—enclosures where various activities coexisted—which included fights between men and animals. The number of investigations on the acoustics of amphitheatres is more limited than for theatres, even though Roman amphitheatres are currently used for a great variety of modern public performances [14,15], a number of which are organised with seasonal continuity, including bullfighting, as is the case of the Roman amphitheatres of Nimes and Arles in France. Several acoustic investigations of amphitheatres have been carried out by Italian researchers [16,17,18,19] using the original virtual reconstructions and with in situ measurements taken by the authors of this work in a theatre and an amphitheatre of Spain. These authors concluded that in the amphitheatre, the reverberation time is noticeably longer and the speech intelligibility worse than in its neighbouring theatre [20].

In the case of unroofed spaces, the spatial characteristics of all reflections during the decaying process differ greatly from those of an enclosed space. The reflection density is sparse, and the energy of late reflections can be very low in unroofed spaces. As a consequence, several scholars have been concerned regarding the applicability of ISO 3382 [21,22] and the use of reverberation times and acoustic parameters when analysing the acoustics of outdoor venues. In these spaces, the reverberation time fails to yield real information on the sound decay: the initial step caused by the lack of early reflections is not reflected in T30, and it underestimates the late part of the decay where isolated perceptible reflections exist [23,24]. Moreover, from the perceptual point of view, the suitability of conventional reverberation parameters remains questionable when judging the perceived reverberance in unroofed spaces [25]. Furthermore, the risk of a disturbing echo is much higher in outdoor venues than in an enclosed room, since a delayed strong reflection can appear unmasked by the reverberation of the room.

Certain authors have also discussed the robustness of the parameters of the aforementioned standard in open theatres and proposed additional parameters whose validity has yet to be verified [26,27]. However, the most relevant pieces of research on classical theatres, open-air spaces, and even on archaeological sites [28] characterise their sound fields by using impulse responses and their derived parameters in accordance with the protocol of the ISO 3382 standard. For the purpose of this study, the objective metrics established in the standard have been assumed: the bullring is a performance space with a roof in the two configurations studied, since with the partially open oculus, the proportion of sky in the roof is negligible (the open roof area is a mere 6.3% of the total area).

Beranek defined texture [29] as “the subjective impression that listeners perceive of the patterns in which the sequence of early reflections of sound reaches their ears,” referring to early reflections as the characteristic attributes of sound in a room. Various authors have transferred the concept of acoustic signature or sound attributes characteristic of ships and aircrafts to the context of an architectural space [30,31] by addressing the relationship between the reflection sequence and the acoustic signature of the room, and it can be stated that the initial reflections constitute a representation of the sound of its architecture.

There is very little background research on acoustic work in bullrings, with only a few conference papers relating to a covered Spanish bullring that presents severe flutter echo problems [32,33]. The authors of this article themselves have also published pieces of research on emblematic Spanish bullrings [34,35,36]. With this work, the authors aim to contribute to the acoustic narrative of bullfighting by linking architecture with the sounds of voice, ambient sound, music, and silence that manifest in charismatic bullrings [34,35,36], thereby providing valuable information regarding their recognised intangible acoustic heritage.

The objective of this work is to present the integral characterisation of the sound field of the Campo Pequeno bullring in Lisbon based on the parametric acoustic description and the spatial–temporal and spectral–temporal analyses of the 3D impulse responses measured in space in the absence of an audience. This study considers the positions of the sound sources involved in the bullfighting spectacle, and the analysis covers two configurations of the mobile roof: the bullring with the closed oculus of the roof and with a quarter of the oculus area of the roof open.

This paper is organised as follows: subsequent to this introduction, Section 2 corresponds to a brief analysis of the bullfighting in Portugal, Section 3 presents a condensed history and architectural description of the building, Section 4 and Section 5 include the materials and methods, respectively, while Section 6 states the results obtained in the empirical campaign and their discussion. Lastly, Section 7 summarises the main conclusions of this study.

2. Bullfighting in Portugal

The word “tauromaquia” comes from Greek, being a combination of the words “bull” and “fight” (touro and luta in Portuguese). In the Iberian Peninsula, it represents an established tradition that has been exported to the Americas. This practice of fighting with bulls (aurochs) has been carried out in the peninsula since prehistoric times and was widely accepted by various cultures of the Ancient Age. However, the most direct antecedent is that of the Roman circus. In this enclosure, various activities coexisted, among which were fights between men and animals, in which there were expert gladiators who specialised in fighting against bulls and began to use a red cloth to distract the animal, in addition to the usual equipment of a sword and shield. This tradition reached the Roman province of Hispania with the expansion of the empire and was common in amphitheatres throughout the peninsula during the 600 years of Roman rule [37].

Bulls, animals both majestic and ferocious, were brought from different regions of the vast empire to face the gladiators. The challenge of confronting a bull in the amphitheatre was no simple task; the gladiators had to display technical mastery in their fight, using different weapons and tactics to keep the bull under control while avoiding its charges. Agility and bravery were essential, since any mistake could result in fatal consequences. These confrontations were considered a demonstration of bravery and heroism for both the gladiator and the animal itself. While modern bullfighting has evolved and developed in a variety of cultural contexts, its ancestral legacy and its power to move and excite endure in the collective memory. Readers interested in the origin of fighting bulls in the Iberian Peninsula may consult [38].

The first reference to bullfighting in Portugal dates back to 1258 in the investigations of King Afonso III, where he reported that King Sancho, the second king of Portugal, speared bulls in the Alonhinga field in Lamago. These bullfighting practices existed before the founding of Portugal. Since the origin of the nationality, bullfights were held in town and city festivals, where square wooden bullrings were set up and subsequently dismantled after the festivities. The great popularity achieved by the bullfights opened the door to their commercial exploitation, with the appearance of the first circular bullring: the Bullring of Junqueira in Belém, inaugurated in 1738.

Until the 18th century, bullfighting was the same in both Portugal and Spain, with the fight and killing of bulls from horseback. However, bullfighting on horseback (cavaleiro) continued to predominate in Portugal, together with the figure of the forcado (a young man who leads the capture of the bull on foot or “pega,” who travels in a team of eight members, led by the “cabo”, to subdue the bull before returning it to the pens). In Spain, the matador on foot emerged, who today predominates in Spanish bullfighting (torero).

On royal initiative, the Campo de Santana bullring, built of wood, was inaugurated in Lisbon on 3 July 1831. It was here that the professionalism of the matadors and promoters of the spectacle was consolidated, with great Spanish matadors and Portuguese cavaleiros and several dynasties of banderilheiros and forcados passing through. For safety reasons, this bullring was closed in 1889, and the Campo Pequeno bullring was built, which opened on 28 August 1892 [39].

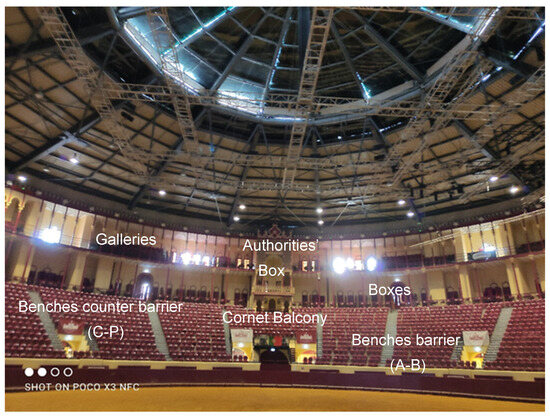

3. Description of the Bullring of Campo Pequeno

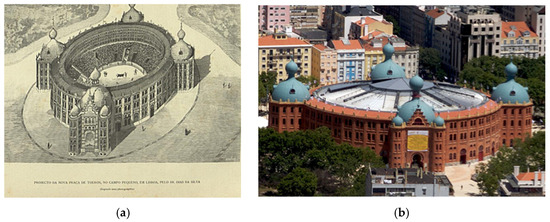

The Campo Pequeno bullring in Lisbon, Portugal, is located on Avenida da República. Built in 1892 by the Portuguese architect António José Dias da Silva, it has a seating capacity of 6698 spectators (Figure 1a). It was inspired by the old Madrid bullring built by Emilio Rodríguez Ayuso, which was later demolished. Built from solid red exposed brick in the Neo-Mudejar style in the lower part and in Byzantine style in the upper part, it has large octagonal towers in the four cardinal directions, horseshoe windows and oriental-shaped domes. It remains one of the most charismatic buildings in the city. In its day, its brick and iron construction was a noteworthy element of modernity [39]. The study by Neves [40] seeks to understand the historical, cultural, and symbolic origins and significance that determine the existence and distribution of bullrings in Portugal.

The Campo Pequeno bullring underwent extensive renovations at the beginning of the 21st century, whereby the brick at its base was replaced with reinforced concrete. A shopping arcade was created in the basement and other similar spaces at street level by architects José Bruchy, Pedro Fidalgo, Filomena Vicente, and Lourenço Vicente. The most significant change was the installation of a movable roof, carried out by João Goes Ferreira, which has enabled it to be used for various activities throughout the year. The roof consists of a fixed part over the benches and a retractable part over the arena. The inauguration after the renovations occurred on 16 May 2006 (see Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 1.

(a) Project of the new bullring in Campo Pequeno, Lisbon, by Dias da Silva. In O Ocidente, No. 452, 11 July 1891, p. 156. Image from Hemeroteca Digital (http://hemerotecadigital.cm-lisboa.pt/OBRAS/Ocidente/1891/N452/N452_item1/P4.html (accessed on 5 November 2025)), extracted from [39]. (b) Aerial photograph of the recently renovated bullfighting ring in Lisbon; image originally published in Girón et al. [36]. (Source: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plaza_de_toros_de_Campo_Pequeno (accessed on 5 November 2025)).

Figure 1.

(a) Project of the new bullring in Campo Pequeno, Lisbon, by Dias da Silva. In O Ocidente, No. 452, 11 July 1891, p. 156. Image from Hemeroteca Digital (http://hemerotecadigital.cm-lisboa.pt/OBRAS/Ocidente/1891/N452/N452_item1/P4.html (accessed on 5 November 2025)), extracted from [39]. (b) Aerial photograph of the recently renovated bullfighting ring in Lisbon; image originally published in Girón et al. [36]. (Source: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plaza_de_toros_de_Campo_Pequeno (accessed on 5 November 2025)).

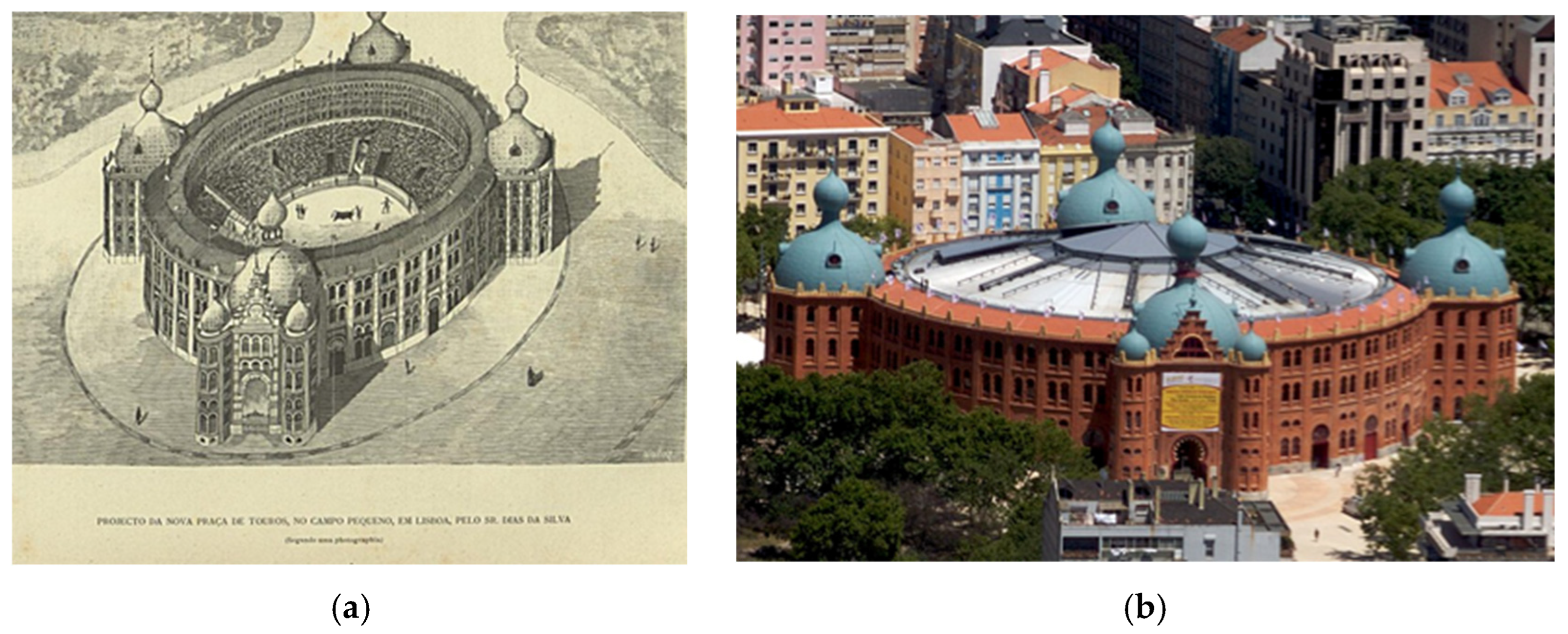

Figure 2.

View of the interior of the bullring with the oculus closed and its different parts visible; image originally published in Girón et al. [36]. (Source: Authors’ own).

Figure 2.

View of the interior of the bullring with the oculus closed and its different parts visible; image originally published in Girón et al. [36]. (Source: Authors’ own).

Figure 3.

(a) View of the roof of the bullring with the oculus over the ring closed. (b) View of the roof of the bullring with the oculus partially open; images originally published in Girón et al. [36]. (Source: Authors’ own).

Figure 3.

(a) View of the roof of the bullring with the oculus over the ring closed. (b) View of the roof of the bullring with the oculus partially open; images originally published in Girón et al. [36]. (Source: Authors’ own).

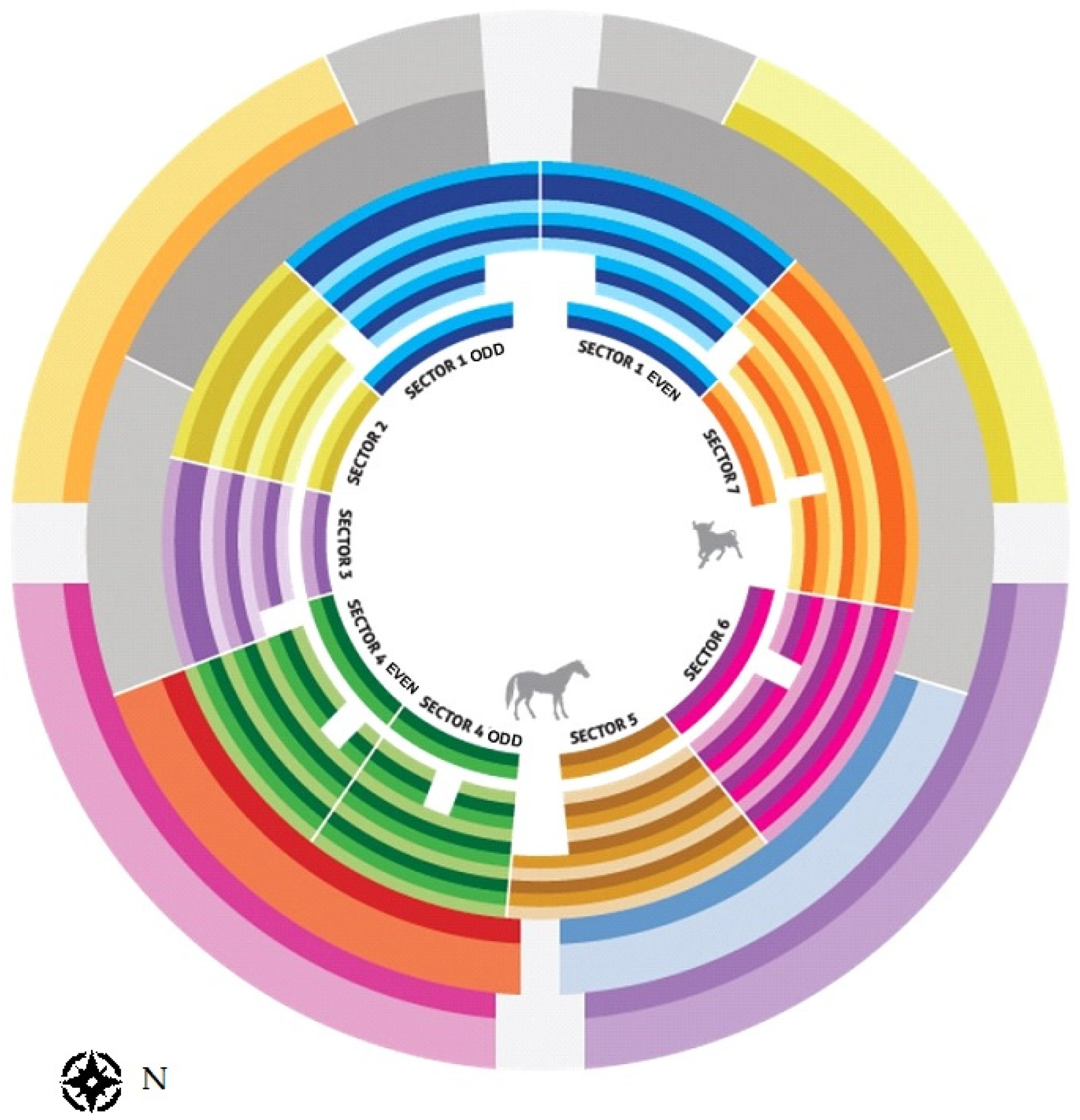

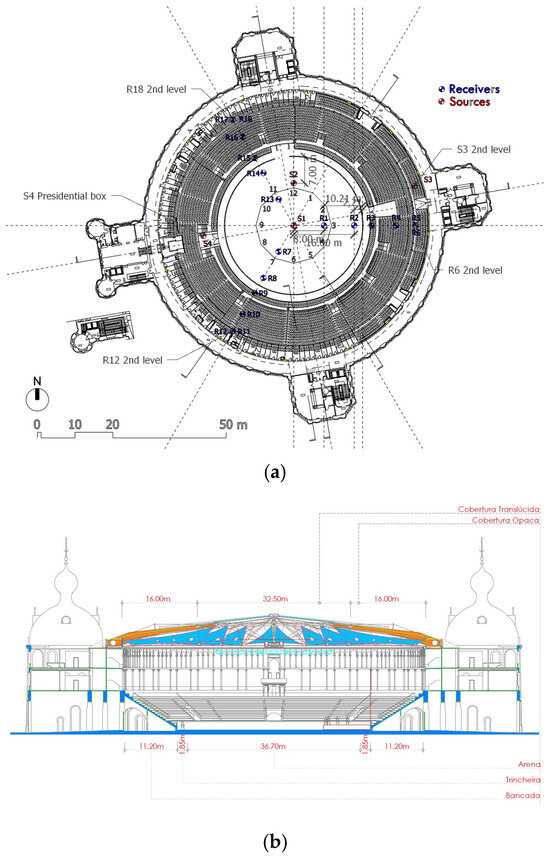

Its arena has a diameter of 36.7 m, a total diameter of the building of 64.5 m, and an estimated volume of 61,693 m3. The bullring is organised into seven sectors (tendidos): the North half (sectors: 1 even, 7, 6, and 5) and the South half (sectors: 1 odd, 2, 3, 4 odd, and 4 even) (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Diagram of the various sectors of the Campo Pequeno bullring and stable gates.

In Campo Pequeno, bullfights on horseback are very common, although bullfights on foot also do exist and differ from those in Spain. Also common are “pegas” (involving the unarmed provocation of the bull) with “forcados,” eight-member teams led by the “cabo” (a bullfighter), who subdue the bull before returning it to the corrals. In Portugal, there is no suerte de varas (a bullfighting ritual with picadors) nor is there death of the bull in the ring but is simulated with a banderihla. While bullfights on horseback occupy the entire area of the ring, bullfights on foot generally take place, if the bullfighter wishes and the bull allows it, near the burladero (short fences placed parallel to the barrier so that the bullfighter can take refuge behind them by entering from the side) in Sector 1 odd as well as Sector 2, opposite the bullpens (Figure 4).

The Campo Pequeno bullring is distributed, from the lowest to the highest tiers, into the following:

- Benches: barrier, two rows of benches (letters A and B); counter barrier, 14 rows of benches (letters C to P, inclusive);

- Boxes: first level, in Sectors 3 and 7, and second level, on both sides of the authorities’ box;

- Galleries: first level, in Sectors 4 and 6, and second level, around the upper gallery, except the second-level boxes (see Figure 2).

The music band, composed of approximately 35 musicians mainly of wind and percussion instruments, is located in the second-level gallery, opposite the authorities’ balcony/box. The cornet calls, which announce changes in the phases of the bullfights, are made to the left of the president of the bullfight.

4. Sound Sources, Receivers, and Audience Areas: Location and Combinations

Based on the identified sound sources, in the Campo Pequeno bullring in Lisbon, 4 source positions and 18 microphone positions are proposed, distributed within three reference radii (Figure 5):

- -

- S1: In the centre of the bullring;

- -

- S2: Where a possible stage would be located (ring side), on the 12 o’clock radius, at the intersection of the 7 m line;

- -

- S3: Where the music band is located, in the second-level gallery, to the right of the access door to the east tower (in seat number 145);

- -

- S4: Where the cornet player is located, on the left-hand side of the bullfighting president, in the balcony above the vomitorium leading to the seats of the west tower.

A total of 18 reception positions is proposed, 12 in the audience positions and 6 in the arena/ring, to analyse the influence and focal points of the roof that may be felt in this area of the venue. To facilitate the implementation of the measures, six positions have been grouped at three reference radii (3, 7, and 11 o’clock), with 12 o’clock pointing north.

Figure 5.

The bullring of Campo Pequeno: (a) ground plan with the location of sound sources (S) and receivers (R) in the ring, benches, boxes, and galleries at three reference radii; (b) section plan, with figures originally published in Girón et al. [36]. (Source: Plateia Colossal with permission).

Figure 5.

The bullring of Campo Pequeno: (a) ground plan with the location of sound sources (S) and receivers (R) in the ring, benches, boxes, and galleries at three reference radii; (b) section plan, with figures originally published in Girón et al. [36]. (Source: Plateia Colossal with permission).

- -

- At 8 m from the centre of the arena (10.21 m from the barrier): in the 3 h reference radius R1, in the 7 h reference radius R7, and in the 11 h reference radius R13;

- -

- At 16 m from the centre of the arena (2.21 m from the barrier): in the 3 h reference radius R2, in the 7 h reference radius R8, and the 11 o’clock reference radius R14;

- -

- At the intersection of the barrier bench: with the 3 h reference radius R3, with the 7 h reference radius R9, and with the 11 o’clock reference radius R15;

- -

- At the intersection of the Bench J: with the 3 h reference radius R4, with the 7 h reference radius R10, and with the 11 o’clock reference radius R16;

- -

- At the intersection of the first bench of the first-level gallery: with the 3 h radius R5, with the 7 h radius R11, with the 11 o’clock radius R17;

- -

- At the intersection of the first bench of the second-level gallery: with the 3 h radius R6, with the 7 h radius R12, with the 11 o’clock radius R18.

The 108 combinations analysed meet the requirements of the guide to acoustic measurements in bullrings published by the authors [34]. Of these, 72 combinations correspond to the closed oculus and 36 to the partially open oculus. Only in the S3-R5 combination is there no direct sound (see Table 1). All 108 combinations were employed to determine the reverberation times only; for the remaining acoustic parameters, including the EK parameter of Dietsch and Kraak, the 107 combinations with direct sound were considered.

Table 1.

Schema of the sources and receivers in the two configurations of the roof in Campo Pequeno bullring.

5. Experimental Method

The experimental measurements were conducted without the public, in accordance with ISO 3382 parts 1 and 2 [21,22]. The environmental conditions were registered by measuring the temperature with an accuracy of ±1 °C. The temperature variation ranged from 22.8 °C to 25.6 °C during the measurement days. The relative humidity was measured with an accuracy of ±5%, and the variation ranged from 61.7% to 69.8%. There was no wind detected during the measurements. The thermo-hygrometric conditions were entered into the measurement software in each session.

The impulse responses (IRs) at the receiving points (see Section 4) were obtained by emitting from the sound source 30 s-long sinusoidal sweep signals, where the frequency grows exponentially with time from 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz. These signals were provided and processed by a commercial software platform (IRIS version 1.2) [41], which was connected to the rest of the measurement chain through the MOTU 4PRE HYBRID sound card (48 kHz sample rate). The excitation signal was emitted using an ultralight Garcia Calderon DD5 dodecahedral sound source located 1.50 m above the ground level and amplified with a B&K 2734-type power amplifier.

The 3D impulse responses were captured with the Core Sound TetraMic microphone array (Core Sound, LLC, Teaneck, NJ, USA) pointing in the same direction as the seat, which allowed for the incorporation of temporal and spatial (3D) information. In all positions, the microphone was placed 1.20 m above the ground. To obtain acoustic parameters related to calibrated sound levels, the sound level at 10 m in a free field was attained through measurements in a semi-anechoic chamber at the Department of Applied Physics II of the University of Seville, in accordance with ISO 3382-1 [21]. These measurements allow for the level to be acquired from the source–receiver distance and a time window of direct sound. The measurements were taken every 12.5° around the sound source to smooth the directional response of the source and at a source–receiver distance of more than 3 m. The EK echo parameters were obtained through the WAV signals of the bullrings loaded into EASERA software v 1.1 [42], since the IRIS platform fails to provide these parameters.

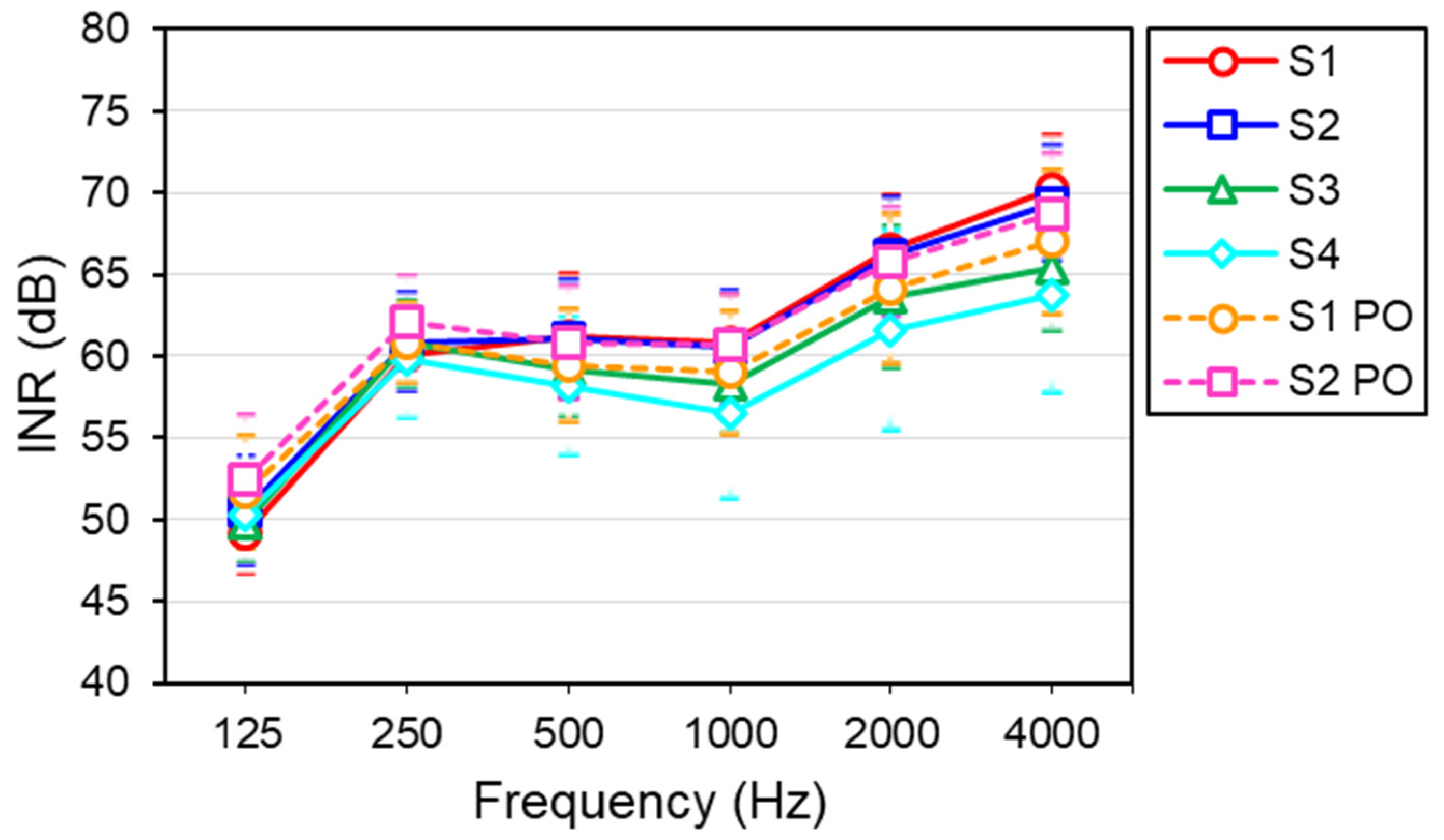

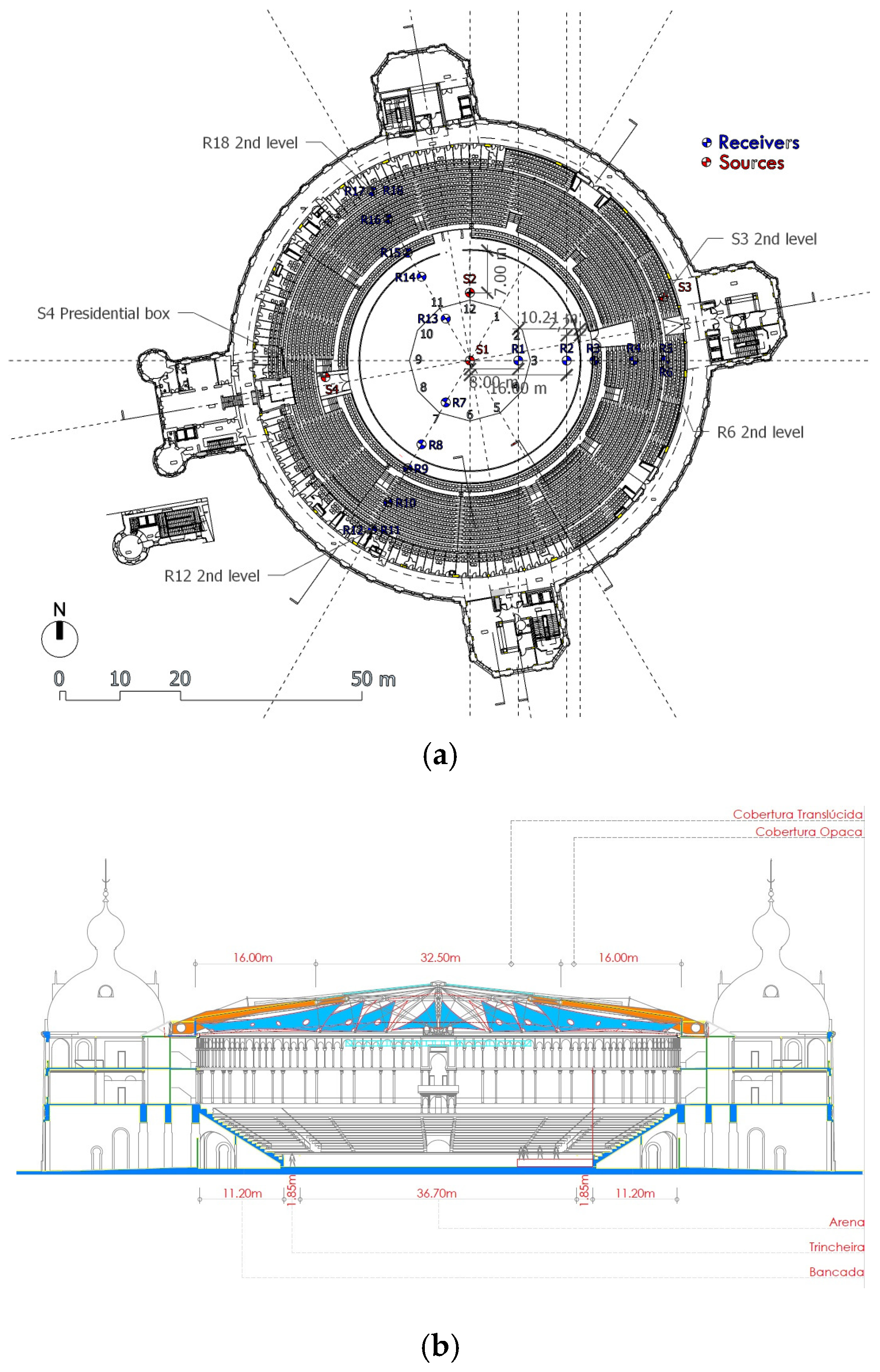

The background noise level was recorded with a Class I PCE-430 sound-level meter. It was measured at six receivers to cover the ring, the benches, and the gallery areas, averaging 5 min in each receiver. The differences between areas on the day of measurement were not significant, with the average value at 46.6 dBA. The sound-source power level was 45 dB above the background noise level in all frequency bands. As can be observed in Figure 6, the INR (Impulse Noise Ratio) remains above 45 dB at all measurement points and in both configurations of the roof of the bullring (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Spatially averaged impulse-to-noise response (INR) ratio as a function of frequency for the four source positions with the closed oculus (S1–S4) and the two with the partially open oculus (S1 PO and S2 PO) in the Campo Pequeno bullring.

6. Results and Analysis of the In Situ Measurements

6.1. Main Acoustic Descriptors

The acoustic study of performance spaces is often conducted on the basis of a set of parameters obtained from impulse response measurements, which, in turn, are related to the subjective aspects of their aural architecture. These acoustic descriptors, defined in the ISO 3382-1 standard [21], are based on the decay time criteria, energy parameters, and directional parameters. The Speech Transmission Index (STI) is also used as a speech intelligibility parameter, in accordance with the IEC 60268-16:2020 standard [43].

The following subsections present the results in graphs of the spatial averages and standard deviations in the six octave bands of interest in architecture. The acoustic descriptors shown are T30, EDT, C80, D50, TS, G, JLF, LJ, and the STI intelligibility parameter. Likewise, the Dietsch and Kraak echo parameters EKspeech and EKmusic [44] have also been studied in this bullring.

Regarding the linearity of the decay curves, it is found that of the 648 recordings (18 reception points, per 6 octave bands, per 6 source positions, in the two configurations of the roof of the bullring), 90.8% meet the linearity criterion C of 0–5% and ξT30 between 0 and 5‰; 6.5% fall within the range of doubtful values, C of 5–10% and ξT30 of 5–10‰; and 2.7% fail to meet the linearity criterion C > 10% and ξT30 > 10‰. The lack of linearity at all frequencies occurs in the S1-R1, S1-R7, and S1-R13 combinations in both roof configurations with the source in the centre of the ring and the receivers also in the ring, since, as shown in Section 6.1.4, there is a double echo at these points.

The objective acoustic quantities derived from the impulse response analysed herein and related to the subjective aspects include (T30), defined as the reverberation time calculated from a best-fit straight line from −5 dB to −35 dB of the backward-integrated decay; Early Decay Time (EDT), defined as the reverberation time calculated from a best fit straight line to the first 10 dB of the backward-integrated decay, for the subjective reverberance; Clarity (C80), defined as the relationship between the logarithmic ratio of the energy that a listener receives in the first 80 ms from the arrival of the direct sound (direct sound + first reflections) and the energy that arrives later, for the clarity of music; Centre Time (TS), defined as the temporal coordinate of the centre of gravity of the area under the energy curve, for the clarity of music; Definition of speech (D50), defined as the ratio between the acoustic energy received in the 50 ms after direct sound arrival and the total energy it receives, for the clarity of speech; and Sound Strength (G), defined as the difference between the sound pressure level produced by an omnidirectional and calibrated source at a reception point and the sound pressure level produced by the same source located in free field at a distance of 10 m, for the subjective level of sound.

The two aspects of spatial impression are also measured: For the apparent source width, there is the Early Lateral Energy Fraction (JLF), defined as the quotient between the energy that reaches a listener laterally within the first 80 ms from the arrival of the direct sound (excluding said direct sound) and the energy received from all directions in said time interval. For listener envelopment, there is the Late Lateral Sound Level (LJ), defined as the logarithmic quotient of the energy that reaches a listener laterally after 80 ms of the arrival of the direct sound to the end of the impulse response and the energy received in free field at 10 m.

The Dietsch and Kraak [44] echo detection criterion EK is based on the time of the centre of gravity of the impulse response. The criteria have been investigated for both speech and music, where it is assumed that the two opposing physical magnitudes of the delayed strong reflection, (i. e., the sound pressure amplitude p and the delay time t), are linked by being a constant product with the acoustic pressure with an exponent n or weighting factor to be determined [44].

As a reference, the threshold of perception of each parameter (just-noticeable difference, (JND)) is displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Just-noticeable differences (JNDs) of the objective room acoustic parameters.

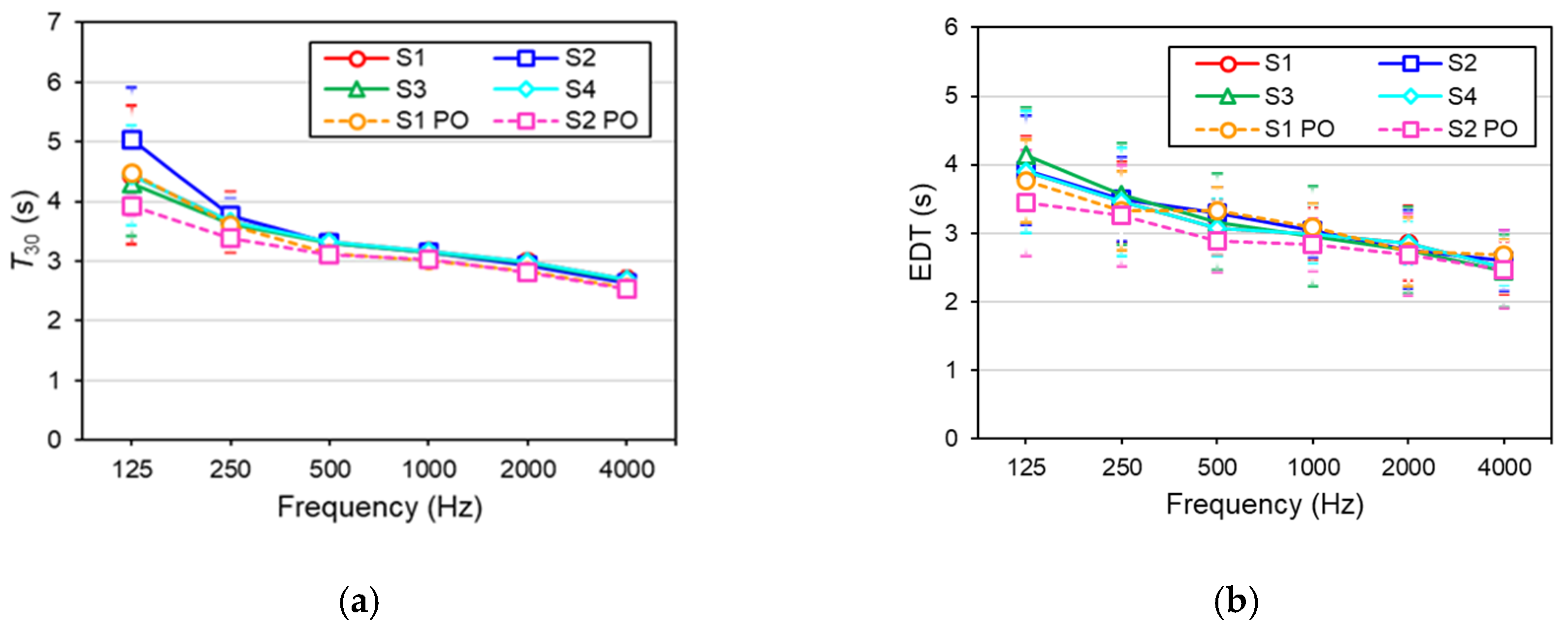

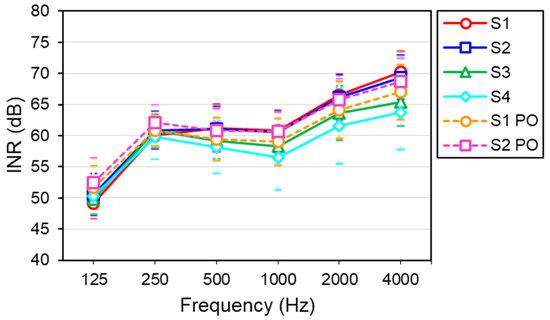

6.1.1. Parameters of Decay Time

The figures below show the results of the objective acoustic parameters (spatially averaged, 18 values per source) as a function of frequency and for the four sound sources in the closed oculus configuration and the source source positions with the oculus partially open. Figure 7a shows the results for the reverberation time, T30, and highlights the similarity of the values for all sound sources except at low frequencies, with a slight increase in values at low frequencies and a decrease in values at high frequencies due to air absorption. The spatial dispersion, assessed through the standard deviation, is very small except when 125 Hz, where it can reach up to 0.86 s for source S3 (4 JNDs). It is worth noting that at all frequencies, the values for source S1 coincide with those of source S1 PO, both for the closed and partially open oculus of the roof. This is not the case for source S2, where the coincidence with S2 PO occurs only at high frequencies. Watson [47] proposed an optimal reverberation time at mid-frequencies for speech for the volume of Campo Pequeno of 2.96 s at 500 Hz and 2.67 s at 1000 Hz, in accordance with the direct dependence of the optimal value on V1/3. Their results are somewhat lower than those obtained here: 3.24 s for the average of the four sources with the oculus closed and 3.06 s with the oculus partially open (see Table 3). Where a diminution of T30m can be observed for the sources with the oculus partially open, of approximately 0.20 s, the spatial dispersion is very low for all sources and does not reach 1 JND.

Figure 7.

Campo Pequeno bullring: (a) spatial average of reverberation time as a function of frequency for each source position (S1–S4 with the oculus closed and S1 PO and S2 PO with the oculus partially open), (b) spatial average of the Early Decay Time as a function of frequency for each source position (S1–S4 with the oculus closed and S1 PO and S2 PO with the oculus partially open). The horizontal bars correspond to the standard deviation.

Table 3.

Campo Pequeno bullring: spatial and spectral * average values of the acoustic parameters for each of the 4 sound sources with the closed oculus (S1–S4) and the 2 source positions (S1 PO and S2 PO) with the partially open oculus. The second row for each source corresponds to the number of JNDs of the standard deviation.

As for the Early Decay Time, EDT (see Figure 7b), there is also a great deal of agreement for all sound sources with slight divergence at low frequencies. The agreement of the results for S1 and S1 PO is noteworthy, while more differences in the spectral results of S2 and S2 PO are shown, with the greatest differences at 125 Hz. The spatial dispersion can reach up to 0.89 s (4.6 JNDs) at 125 Hz for source S4. The sensation of reverberation at low frequencies of EDT is less than that which could be inferred from T30 but, in general, still maintains very high values. Regarding the results of the single value (spectral averages according to ISO 3382-1 [21]; see footnote of Table 3), greater differences in the value for each source is appreciated in the EDTm parameter than in T30m. Furthermore, the spatial dispersion is much greater and can reach values of up to 4.7 JNDs for source S3. EDTm falls outside the typical range given by the ISO standard (1 s–3 s), although this range is for rooms up to 25,000 m3. EDTm also falls outside the merit range 1 proposed by Arau-Puchades [48] for theatres: 1.9 s–2.5 s. In the single values of Table 3, there is a decrease in EDTm when the oculus is partially opened and is more significant in the S2 position. The values of these parameters of decay time are long compared to other bullrings of a similar volume and are discussed below, in Section 6.1.3.

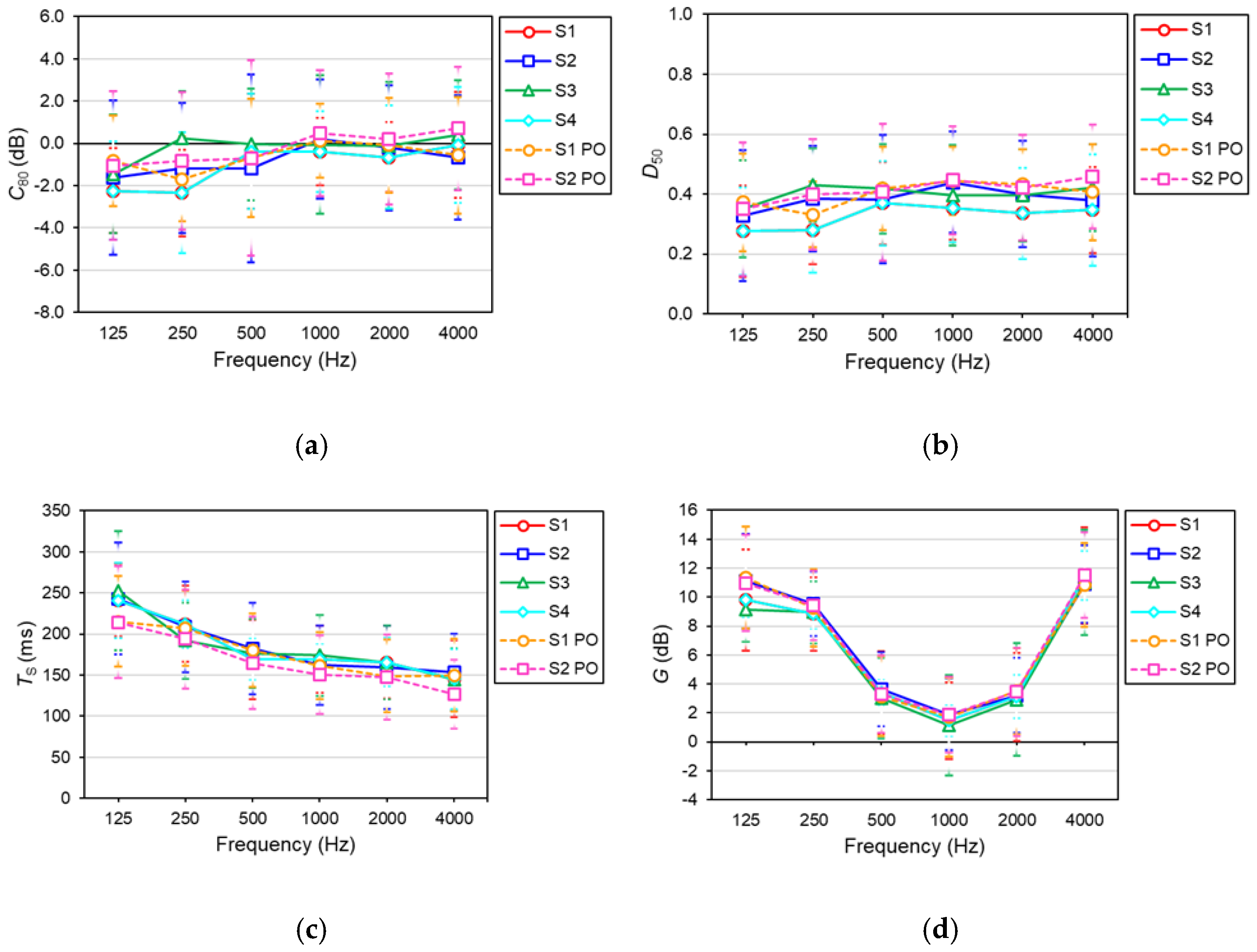

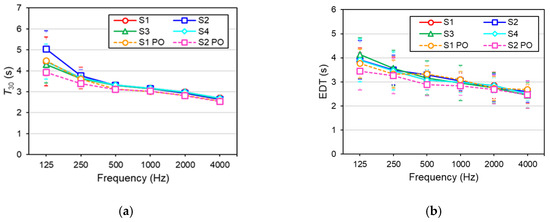

6.1.2. Energy Parameters

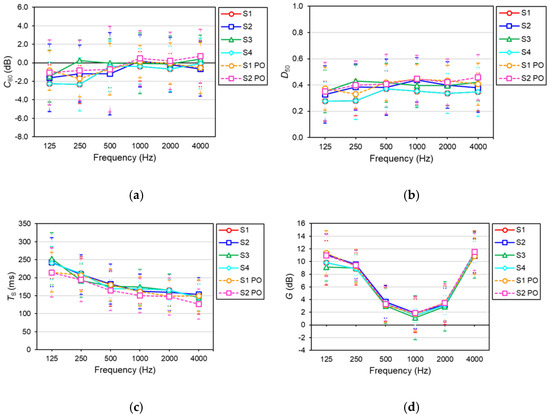

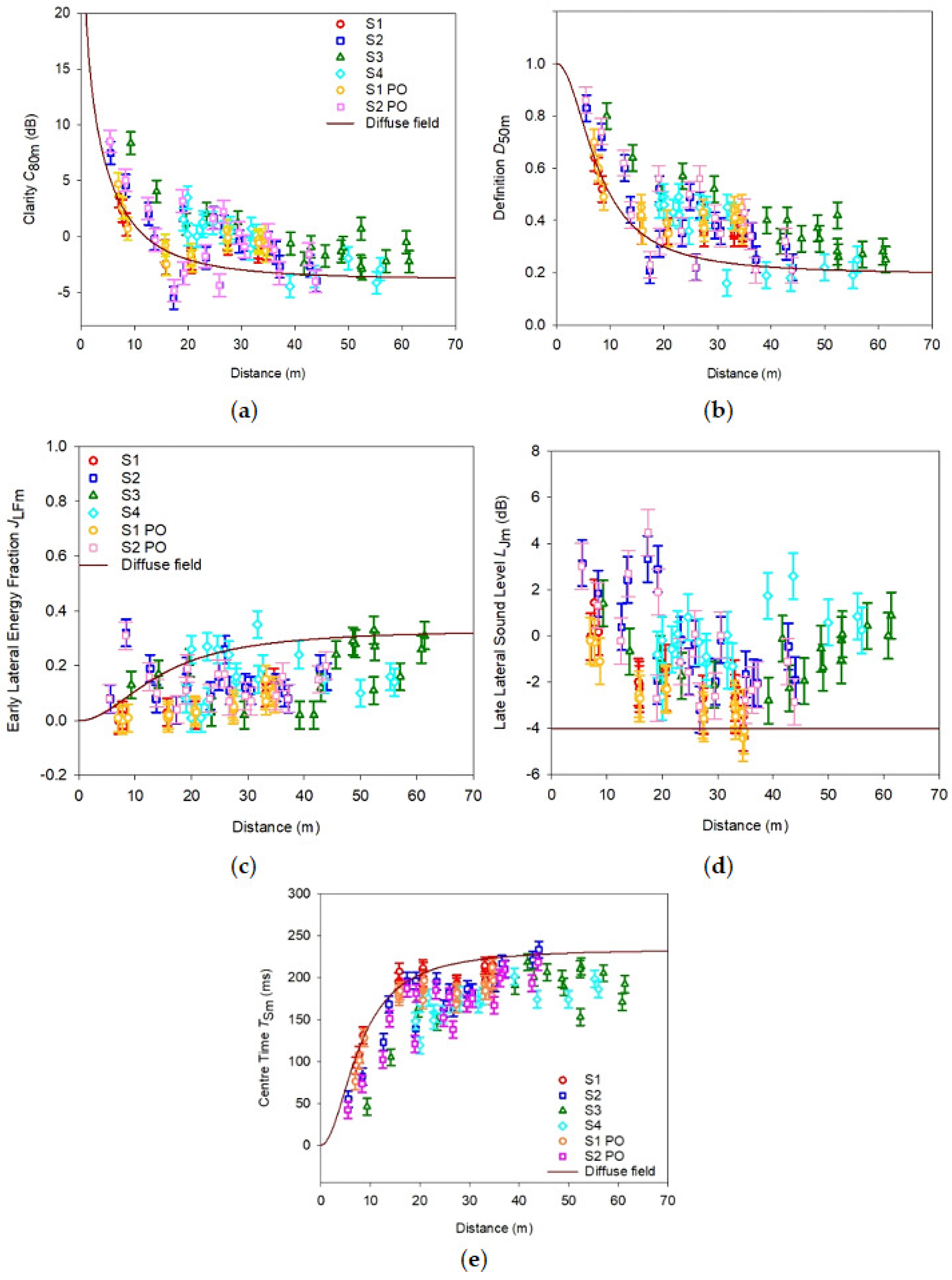

The Clarity parameter, C80, (Figure 8a), which assesses the clarity of musical sounds, indicates that there is a fluctuating behaviour of the parameter with the frequency and position of the source, with the greatest dispersion in the values at 125 and 250 Hz, although the values move within the range from −2 dB to +1 dB, thereby remaining within the typical range indicated by the ISO standard (−5 dB–+5 dB). The spatial dispersion is large and can reach 4.5 JNDs at 500 Hz, which indicates that the parameter is sensitive to seat-to-seat variations. Regarding source S1, note the slight increase in the parameter when the oculus is partially open, especially at low frequencies; for source S2, there is also a relative improvement in the parameter at all frequencies, with the greatest difference at 4000 Hz. Regarding C80m, the average spectral values also reveal that the parameter value for the six sound-source configurations nearly coincide with variations that do not reach 1 JND and that the spatial dispersion of the parameter values coincide for the various sound sources. According to Barron [49], the optimum range for symphonic concert for C80m appears to be between −2 and +2 dB, although the upper limit can be extended slightly higher. Arau-Puchades [48] recommends C80 > 6 dB in a theatre: in this bullring, the results remain far from this last recommendation, although the results do lie in the middle of the range proposed by Barron. The highest value of the parameter is for the source S3, which is precisely for the music band. This seems to indicate, at least, an acceptable level of musical Clarity during the celebration. The slight improvements in the parameter when comparing sources S1 and S2 with the oculus closed and partially open are also extendable to the single values in Table 3, with increments of approximately 0.5 dB (value below the perceptible threshold).

Figure 8.

Spatial average versus frequency for each source position (S1–S4 with the closed oculus and S1 PO and S2 PO with the oculus partially open) in the Campo Pequeno bullring: (a) Clarity, C80; (b) Definition, D50; (c) Centre Time, TS; (d) Sound Strength G. The horizontal bars represent the standard deviation.

Regarding speech intelligibility, the objective parameter Definition, D50, in Figure 8b, shows that the results for the sound sources are flat around the value 0.4, except for the results for sources S1 and S4, which present greater variation with frequency and whose values also coincide. The best values of the parameter at mid and high frequencies correspond to source S2 PO. The spatial variations are large for all sound sources and frequencies, especially for sources S2 and S2 PO, which exceed 3 JNDs at all frequencies and reach 4.6 JNDs at 500 Hz, which indicates that the parameter is sensitive to seat-to-seat variations. The D50m values in Table 3 also show a constancy of approximately 0.4 for all sources and a similar spatial dispersion: these results are in the low part of the typical range indicated in the ISO standard [21] of 0.3–0.7 and in the range fair according to the study by Fürges and Nagy [50] (0.30–0.55). When the oculus is partially open, the D50m results show slightly higher values (0.02), which are less than 1 JND. This data therefore indicates that the interactions between the bullfighter’s assistants, the audience, and the bullfighter are acceptably interpreted.

The Centre Time, TS, shown in Figure 8c, shows a rise at low frequencies, with decreasing values at 4000 Hz for all sound sources. The spatial dispersion is large for all sources and frequencies, in the order of 4.5 JNDs, and can reach up to 7.2 JNDs (72 ms) for S3 at 125 Hz. Comparing the sources measured in the two roof configurations, S1 PO shows a decrease in values compared to the set only at 125 Hz, while S2 PO shows an appreciable decrease at all frequencies, especially at 125 and 4000 Hz. The average spectral values TSm in Table 3 show that for the four sources with the closed oculus, the average is 176 ms with a dispersion of 4.2 JNDs, while for the configuration with the oculus partially open, the average of the two sources is 164 ms with a dispersion of 4.7 JNDs. In all cases, the parameter values are in the centre of the typical ISO range (60–260 ms) and are within the fair range of values in the study by Fürges and Nagy [50] (95–230 ms), thereby confirming the results of musical Clarity and word Definition during the performance.

Lastly, in Figure 8d, the Sound Strength, G, shows a notable decrease in values at the frequencies of 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz, with similar results for nearly all sources. Sources S3 and S4 differ slightly from this behaviour, since their values drop slightly at all frequencies, especially at low frequencies. All data obtained is above 0 dB and, hence, lies in the typical range −2 dB–+10 dB, as specified by the ISO standard [21]. The spatial dispersion depends on the source and frequency, whereby the lowest is for source S4 and reaching values of up to 3.5 JNDs for S3 at 1000 Hz, among others. Furthermore, for the average spectral values Gm shown in the corresponding column of Table 3, the above comments are extended with changes in the value of the parameter of approximately 0.5 dB between the two configurations of the roof (less than 1 JND).

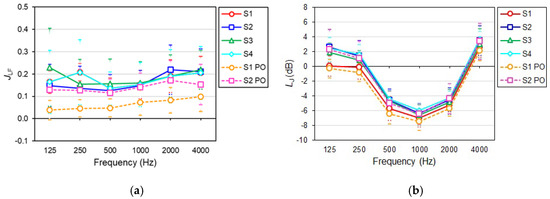

6.1.3. Directional Parameters

The Early Lateral Energy Fraction, JLF (Figure 9a), which assesses the perception of apparent sound source width, indicates that the most unfavourable values are presented for the position of the source S1 PO at all frequencies due to the lower lateral effect of the sound than in other configurations. Moreover, the roof is partially open, giving the subjective impression that the sound source is less wide or smaller in size in the centre of the ring. The rest of the sound sources present behaviour that is more similar as a function of frequency, and the results lie within the range of values 0.1–0.25, which are within the typical range of the ISO standard, 0.05–0.35. Except for the source S1 PO, the spatial dispersion is large, reaching values of up to 3.5 JNDs in S3 at 125 Hz. For the spectral averages, JLFm, the lowest values of the parameter are for the S1 position, but with the lowest spatial dispersions of 1 JND. Better values are obtained for the remaining sources although with bigger spatial dispersions, and there are no changes in the parameter when comparing the results for source S2 in the two configurations of the roof (Table 3).

Figure 9.

Spatial average as a function of frequency for each source position (S1–S4 with the closed oculus and S1 PO and S2 PO with the oculus partially open) in the Campo Pequeno bullring for the (a) Early Lateral Energy Fraction, JLF, and (b) Late Lateral Sound Level, LJ. The horizontal bars correspond to the standard deviation.

The objective parameter that assesses the sound envelopment, the Final Lateral Sound Level, LJ (Figure 9b), presents negative values for all sources, except at 125, 250, and 4000 Hz, and for source S1 PO, which is only positive at 4000 Hz. The behaviour in terms of frequency is similar for all sources with a minimum at 1000 Hz and a maximum value at 4000 Hz. The spatial dispersion is 1–2 JNDs in most sources and frequencies, and only for source S2 PO does it reach 2.7 JNDs at 125 Hz. The average spectral values LJm also indicate the same aforementioned results: all averages are negative values with the most favourable values for source S2 in both configurations of the roof. In all cases, the results lie within the typical range provided by the ISO standard: −14 dB to +1 dB. If the results are transferred to the bullfighting world, the presence of the roof improves the relationship between the bull and the bullfighter and forcados and between the audience and the bullfighter and forcados, as well as with the sound messages where the clarity of speech is important (relationship between the bullfighter ‘s assistants and the bullfighter and forcados).

It is also feasible to indicate that the effect of opening two oculi of the roof exerts a certain influence on the acoustic parameters in terms of both their spectral behaviour and the individual values of Table 3. By opening the roof, it is possible to reduce the reverberation of the time parameters, with very little effect on C80 and G, while improving speech intelligibility D50 and TS without excessively compromising the early and late lateral energies, especially regarding source S2 PO and something for source S1. The positions of musical sources S3 and S4 present satisfactory values for music.

For a comparison of the values of the acoustic parameters in this bullring with other Spanish bullrings without a roof, Table 4 displays the average frequency values averaged for all receptors and sources. Given Table 4, it is worth highlighting that in the Las Ventas bullring [34], T30m and EDTm present larger values than in the rest of the bullrings studied without a roof (RMC Ronda [35] and RMC Seville), although Las Ventas constitutes the largest bullring in Spain. The decay time parameters in Las Ventas are of the order of magnitude of those in Campo Pequeno in both roof configurations due to the existence of a non-absorbent roof. Much better values of C80m are presented in RMC Ronda, RMC Seville, and even in Las Ventas, than in Campo Pequeno. Furthermore, better values of D50m, TSm, JLFm, and STI are found in unroofed bullrings but not for the G and LJ parameters, with especially low values in the Seville and Las Ventas bullrings. These latter parameters are of great importance in a sound field, since if the sound level is inadequate, then there is no point in assessing the Clarity and Definition of the sound. Nevertheless, the D50m, TSm, and STI parameters in all the bullrings lie within the fair range, according to the study of Fürjes and Nagy [50]. Lastly, in the Spanish bullring of Villena in Alicante, a value of 12 s for the reverberation time at 1000 Hz is given by Vera-Guarinos et al. [32]. This bullring has a fixed glass roof that produces excessive reverberation and a perceptible flutter echo in the arena.

Table 4.

Comparison of the average frequency values * averaged for all receptors and sources in the four bullrings studied by the authors: in Campo Pequeno, in the two roof configurations, closed oculus (CO) and partially open oculus (PO).

6.1.4. Echo Parameters

The risk of an echo according to Dietsch and Kraak exists for the source–receiver combinations where EKspeech ≥ 1 and EKmusic ≥ 1.8 [44]. Regarding the 108 impulse responses measured and processed in Campo Pequeno to obtain these echo parameters, and according to these risk criteria, in none of the 107 recordings is there a risk of a disturbing echo for music. Subsequent to the analysis of the values of EKspeech with the closed oculus (CO) and after a detailed analysis of the time–energy curves and the strong reflection times of the impulse response signals, of the 71 combinations, there is a risk of echo for speech in the following 6 combinations: S4-R1, S1-R1*, S1-R2, S1-R7*, S1-R8, and S1-R13*, with a double echo in the three combinations with asterisks. In the partially open oculus configuration (PO), of the 36 combinations, the echo risk for speech is present in the following four combinations: S1PO-R1, S1PO-R7*, S1PO-R8, and S1PO-R13*, again with a double echo in two receivers. In the case of the combination for the sound source in the cornet position, S4-R1, it is not of much interest, given that a musical source and not a spoken source is located in S4. Of the five combinations with CO and four with PO corresponding to source S1 mentioned above, it is worth noting that these are combinations with both the source and the receiving microphone in the arena of the bullring, which indicates that attention should be paid to these echo problems in theatrical performances where the source and the audience are all located within the arena [36] but not for bullfights.

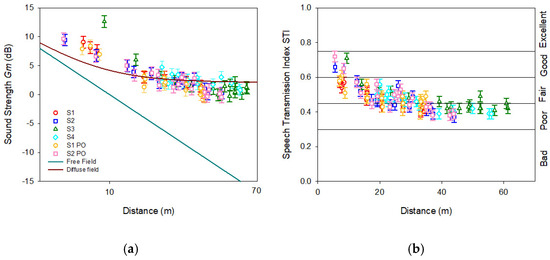

6.1.5. Acoustic Parameters Versus Source–Receiver Distance

The parametric analysis is completed with the results of the acoustic energy parameters, directional parameters, and the STI as a function of source–receiver distance for all the sound sources and the two configurations of the roof studied.

Figure 10a for Gm shows that for all sound sources and receivers at varying distances r, the results oscillate within a narrow range of values, which indicates that sound amplification is fairly uniform in this bullring, regardless of the location of the sound source and the listening point. The results for all source–receiver combinations are in the order of 5 dB above the free-field values (Equation (1)):

Gm(r) = 20 − 20 log r (dB)

For a diffuse field, the dependence of Gm with distance r is shown in Equation (2):

Gm(r) = 10 log (100/r2 + 31,200 T/V) (dB)

For distances beyond the reverberant radius (7.86 m in this bullring according to Equation (3), with the reverberation time 3.24 s and the volume of the bullring at 61,693 m2), this tends towards the value of 10 log (31,200 T/V), which is estimated as 2.1 dB [51]. The experimental results closely match the diffuse field model Equation (2). The importance of suitable values of sound distribution is obvious; for enclosures, Bradley [52] proposes a minimum criterion for G that varies with distance and would indicate a value of at least +2 dB roughly near the middle of a large room. In this case, the results of S2 PO are those that best meet this criterion at 30 m.

The Speech Transmission Index, STI, is a single-value parameter that integrates the significant spectral data of the spoken message. The results in Figure 10b indicate that there are five receivers close to the sound sources that are located within the good intelligibility zone. Excluding these five receivers, two-thirds of the remaining receivers lie within the fair intelligibility range, and one-third of these receivers are in the poor intelligibility range. It should be borne in mind that many of the lowest-rated receivers at greater distances from the source correspond to combinations of musical rather than spoken source–receiver pairs (sources S3 and S4).

Figure 10.

Campo Pequeno bullring: (a) Sound Strength average, Gm, and (b) Speech Transmission Index STI, as a function of source–receiver distance for the four positions of the sound source with the oculus closed (S1−S4) and the two positions with the oculus partially open (S1 PO and S2 PO).

Figure 10.

Campo Pequeno bullring: (a) Sound Strength average, Gm, and (b) Speech Transmission Index STI, as a function of source–receiver distance for the four positions of the sound source with the oculus closed (S1−S4) and the two positions with the oculus partially open (S1 PO and S2 PO).

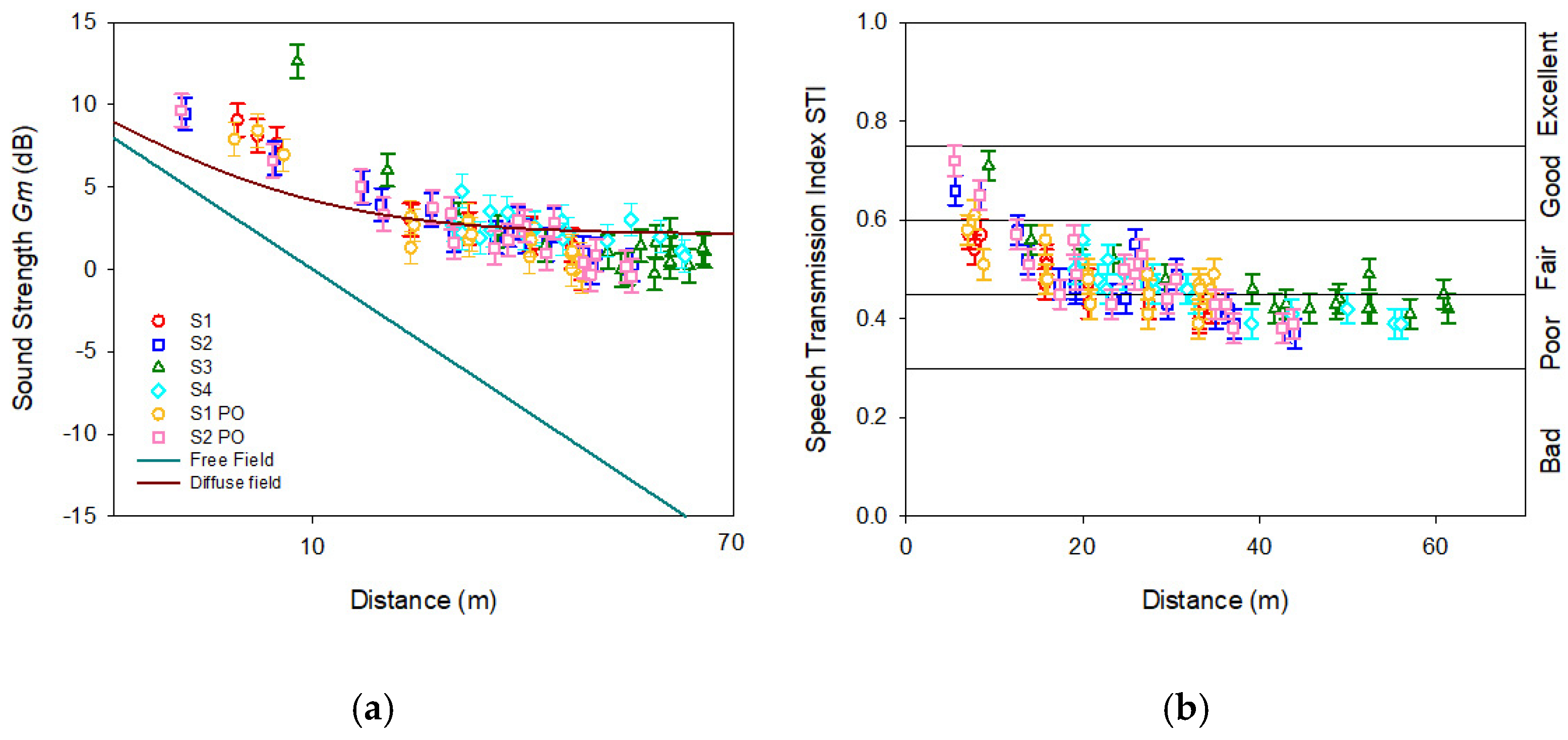

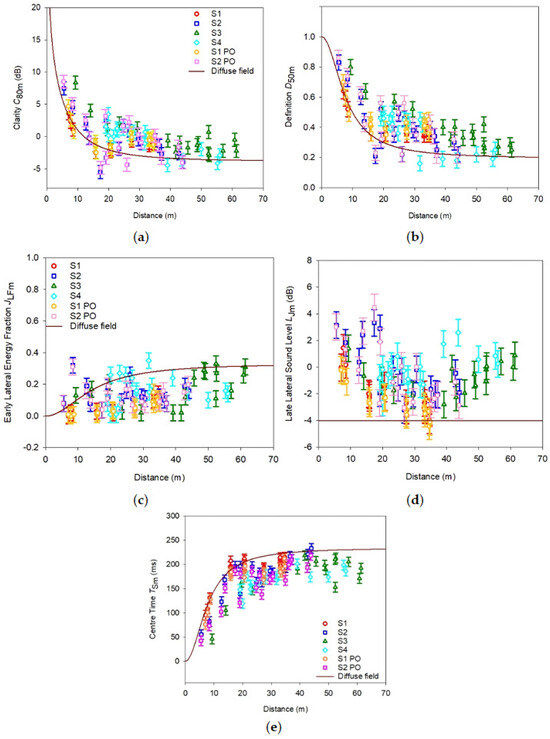

Completing the analysis, Figure 11a represents the behaviour of each receiver for the four sources in the configuration with the oculus closed and the two positions of the sound source with the oculus partially open regarding the spectral Average Clarity. The behaviour is highly variable, but the parameter values largely remain high and correspond to the low sound absorption of the roof fabric. These results are significantly greater than those calculated for an enclosed space in a diffuse model [51], calculated from Equation (4). The best results are for sources S3 and S4, which is very convenient since these are of a musical nature. In the diffuse field model for distances greater than 10 m, C80m values would tend towards −3.6 dB with the roof partially open and towards −3.9 dB with the roof closed, with values calculated from Equation (4).

The dependence of C80m as a function of distance in a diffuse field is given by Equation (4):

Regarding the Average Definition shown in Figure 11b, there are also clearly two groups of values, whereby the best values are for the musical sources S3 and S4. Most receivers are located in the 0.3–0.5 range and exceed that which would correspond to a diffuse sound field calculated from Equation (5). For distances greater than the reverberant radius, D50m in this model tends towards [51], which would be 0.19 and 0.20, respectively, as deduced from Equation (5), again considering a reverberation time T30m of 3.24 s with the oculus closed and 3.06 s with the oculus partially open.

Figure 11.

Acoustic parameters as a function of source–receiver distance for the 4 sound source positions with the oculus closed (S1–S4) and the 2 positions with the oculus partially open (S1 PO and S2 PO): (a) Average Clarity, C80m; (b) Average Definition, D50m; (c) Average Early Lateral Energy Fraction, JLFm; (d) Average Late Lateral Sound Level, LJm; and (e) Average Centre Time, TSm. Spectral averages are calculated in accordance with the ISO 3382-1. The error bars correspond to their JND (Table 2).

Figure 11.

Acoustic parameters as a function of source–receiver distance for the 4 sound source positions with the oculus closed (S1–S4) and the 2 positions with the oculus partially open (S1 PO and S2 PO): (a) Average Clarity, C80m; (b) Average Definition, D50m; (c) Average Early Lateral Energy Fraction, JLFm; (d) Average Late Lateral Sound Level, LJm; and (e) Average Centre Time, TSm. Spectral averages are calculated in accordance with the ISO 3382-1. The error bars correspond to their JND (Table 2).

For the directional parameters, Figure 11c shows the results of the Average Early Lateral Energy Fraction, with very constant and coincident low values for sources S1 and S1 PO. Most receivers show a slight increase for the other sources and variable results with distance. These low values correspond to a quasi-free sound field, in which the parameter would be equal to 0. In the case of a diffuse field in a closed space, the behaviour of the parameter versus distance is shown in the solid line of Figure 11c, calculated from Equation (6), which, for great distances, would tend towards 0.33 [53].

Figure 11d shows the results of the average Final Lateral Sound Level, whose behaviour varies across the receivers and sound sources, with highly negative values due to a quasi-free sound field. The values corresponding to the parameter in a diffuse field in a closed space depend on the reverberation time T and the volume V of the space [53]. As shown in Equation (7), in this hypothesis, LJ is not dependent on distance r and is approximately −4 dB in this bullring. The majority of receivers for all sources present greater values, as shown in Figure 11d.

The results of the parameter Average Centre Time TSm, as a function of source–receiver distance, are shown graphically in Figure 11e. These present a similar behaviour to the previous monaural parameters, with an average value of 176 ms for the four sound sources placed with the oculus closed. This differs from the 234 ms, corresponding to values above the reverberant radius in a diffuse field [51], as given by Equation (8), which tends towards Tsm = T/13.82. It also differs from the 164 ms for the average of the two sound sources placed with the oculus open and does not correspond to values above the reverberant radius in a diffuse field [51] calculated as 221 ms. For the calculations in each case, a reverberation time T30m of 3.24 s with the oculus closed and 3.06 s with the oculus partially open has been considered in Equation (8).

A common feature of all these parameters is that there is a notable coincidence of the values of S1 and S1 PO and also in many receptors for the S2 and S2 PO sources.

6.2. Analysis in the Time–Frequency and Space–Time Domains: Acoustic Signature

The acoustic signature of this space was obtained by analysing the early reflections based on the 3D impulse response and by evaluating the distribution of sound energy in the time–frequency and space–time domains [30,31]. The acoustic signature is particularly determined by the levels and delays of reflections after the direct sound by means of the frequency response (RFR) derived from the room impulse response (RIR).

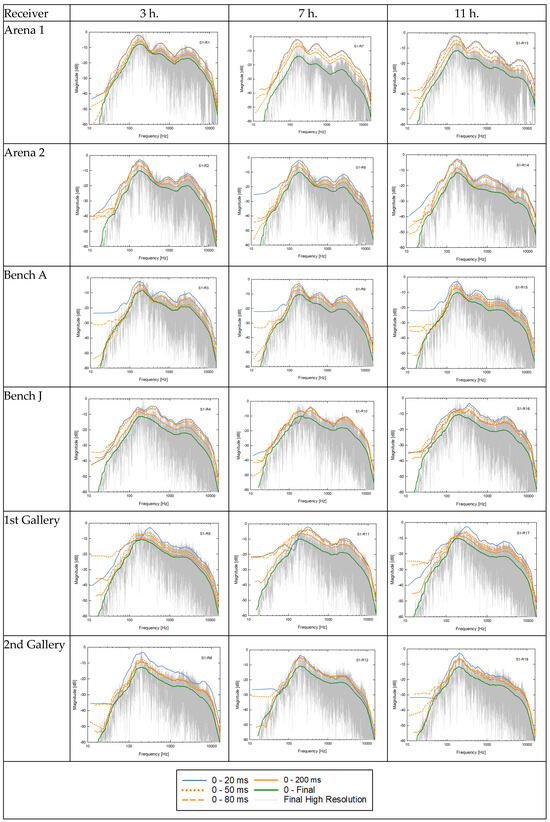

Figure 12 shows the RFR magnitude curves for the 18 combinations between source S1 (centre of the arena) and the six various receiver positions from the arena to the upper galleries and on the three reference axes (3 h, 7 h, and 11 h). Each curve corresponds to time intervals from the direct sound to 20, 50, 80, and 200 ms, as well as the final. The 20 ms limit is associated with the auditory precedence effect; the 50 and 80 ms limits are associated with speech and music Clarity; 200 ms marks the threshold of the initial −5 dB decay used in estimating reverberation time. The cumulative response after 200 ms reflects the energy of the diffuse reverberant field.

Figure 12.

Frequency response corresponding to receivers 1 to 6 (left column), 7 to 12 (central column), and 13 to 18 (right-hand column) for source S1 located in the centre of the arena with the oculus closed, smoothed in 1/1 octave bands.

The RFR curves are presented cumulatively for various time intervals from the arrival of the direct sound up to 200 ms and the final reverberant field. This segmentation enables the interpretation of the progressive contribution of early and late reflections:

- 0–20 ms: In this first interval, direct sound predominates, with a spectral response showing certain irregularities, especially in the receivers located in the arena and the Barrier Bench A. In general, in this and the following two intervals, the early energy is very similar in its spectral envelope. The energy is concentrated in the mid-range (250–1000 Hz) and reflects the direct influence of the source and the low interference from the environment. A maximum is observed at approximately 200 Hz in all areas, while for the Counter Barrier Bench J position, the maximum is at approximately 300 Hz.

- 0–50 ms: This corresponds to the critical range for speech Clarity, where the first reflections from the walls and grandstands begin to be incorporated. In this interval, small spectral undulations arise, with losses located at approximately 500–800 Hz and 1–2 kHz, which are associated with diffraction effects and interference caused by reflections from the barrier and benches. Furthermore, two relative maxima are identified for the arena and the Barrier Bench A, one at approximately 200–300 Hz and the other between 1 and 2 kHz, separated by a dip, while in the remaining positions, only the relative maximum in the 1–2 kHz range appears.

- 0–80 ms: The curves show a progressive reinforcement in the mid–high range (1–2 kHz), especially noticeable in the Barrier Bench A zone. This phenomenon indicates the incorporation of reflections that contribute to musical perception. The pattern of relative maxima identified above is maintained, thereby highlighting the coincidence of the peaks in the different receivers and reinforcing the uniformity of the early energy.

- 0–200 ms: From this point onwards, energy decay becomes evident, with a slight general attenuation of the spectrum that is more noticeable in receivers distant from the source: this confirms the absorption of materials and dispersion in the air. However, the relative maxima previously observed remain perceptible, albeit with less contrast compared to the intermediate dips.

- 0–final (diffuse field): The final curves tend to smooth out, which indicates a more homogeneous distribution of sound energy. The spectrum stabilises with a predominance of low and mid-frequency components, which reflects the reverberant characteristic of the diffuse sound field in this covered enclosure.

Overall, the RFR curves show how the space combines a dominant direct field in the lower areas (which acoustically supports the bullfighter’s calls to the bull) with a more balanced and diffuse impulse response in the benches and galleries, (assisting the different interactions between the audience, music band, cornet, matador, forcados, cabaleiros, and assistants), thereby creating a characteristic acoustic signature as a distinctive acoustic feature that is perceived as part of the sound identity of the bullring. The persistence of low-frequency minima and the progressive recovery of energy around 1 kHz towards the upper areas of the space confirm the distinctive character of the venue, where the shape and arrangement of the benches decisively condition the spectral response perceived by listeners.

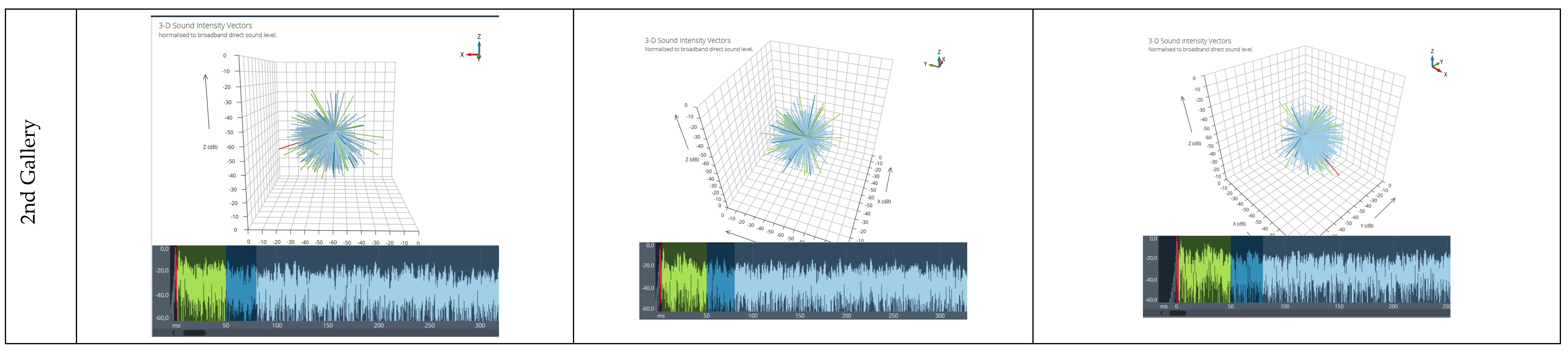

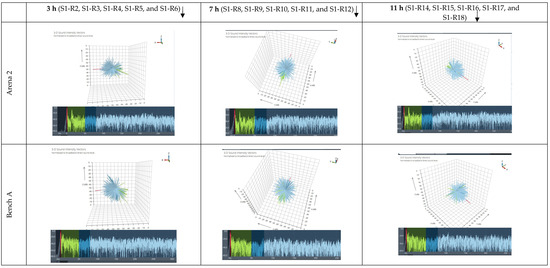

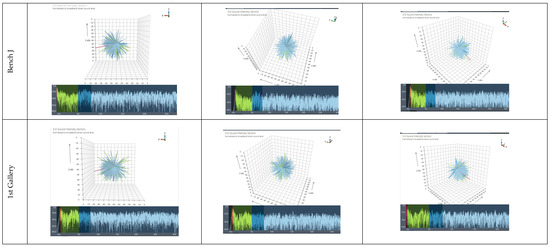

As for the direction of early reflections, the plots in Figure 13 illustrate sound energy arriving at the receiver positions, the same as in Figure 12 (except those closest to the source located in the arena, Arena 1), as a series of vectors or spikes, known as “intensity urchins” on a 3D Cartesian diagram, where the length of each vector indicates level, the angle represents the incoming direction, and the colour corresponds to time of arrival. The four tetrahedral cardioid signals from the TetraMic microphone array are converted into a first-order B-format, which encodes the pressure (omnidirectional) and the three particle velocity signals (figure-of-8) in the X, Y, and Z directions. The filtered B-format impulse response is divided into a series of non-overlapping rectangular windows. The average direction of sound energy flow in each window is determined using a sound intensity technique, which corresponds to the product of pressure and particle velocity. In the measurements studied, a 2 ms time window was used, which restricts the analysis to frequencies of 500 Hz and above, and the vectors were coloured according to the time intervals for speech: 0–2 ms, red; 2–50 ms, green; 50–80 ms, dark blue; and >80 ms, light blue, which coincide with the respective colours of the pressure waveform.

Figure 13.

The 3D Sound intensity vectors from IRIS and log(p2) waveform (dB) at 1 kHz, for S1 in the centre of the arena with the oculus closed and receivers 2 to 6 (left column), 8 to 12 (central column), and 14 to 18 (right-hand column).

Aside from the similarity in the initial reflection pattern according to the log p2 graphs in the 15–50 ms time interval for the positions of the relative radii to the centre of the bullring, the 3D urchin diagrams also show that for the receivers R2, R8, and R14 in the arena and for the receivers R3, R9, and R15 in the Barrier Bench A, there are significant early reflections coming from the back, that is, from the benches. As we move away from the centre of the bullring, the significant early reflections come mainly from the roof, although they exist in all directions (see the 3D diagrams of R5 and R6, R11 and R12, and R17 and R18 receivers in the galleries). In the receivers located on the Counter Barrier Bench J, R4, R10, and R16, the diagram represents a transition between the pattern of the receivers at the ground level in the arena and the Barrier Bench A, as well as those in the upper benches and galleries.

7. Summary and Conclusions

Understanding the acoustics of this iconic 19th-century building in Portugal’s capital adds a substantial intangible feature to its already considerable architectural and cultural heritage value. The parametric analysis of the Campo Pequeno bullring, both in terms of its dependence on frequency and its average single-value values, shows that the reverberation time parameters are longer than the optimum values estimated for a dependence proportional to V1/3, as suggested by several authors for reverberation time, and also for Early Decay Time at medium frequencies. However, the total omnidirectional and Final Lateral Sound Levels present very favourable values in accordance with typical and optimal ranges. Despite the high reverberation due to the presence of a poorly absorbent roof, the rest of the acoustic quality parameters for music Clarity, Centre Time, and Early Lateral Energy, as well as word Definition, are not particularly compromised, which underlines the improvement in the parameters for the position of the source on one side of the arena and with the partially open roof oculus S2 PO. This suggests the possibility of the venue implementing variable acoustics depending on the roof configuration. According to the directional indicators in the bullfighting world, the presence of the roof improves the relationship between the bull and either the bullfighter or forcados and between the audience and either the bullfighter or forcados, as well as with those speech sound messages where intelligibility of speech is essential (communication between the assistants and the bullfighter or the forcados).

Furthermore, considering all receivers globally, the results of the acoustic parameters as a function of the source–receiver distance indicate that the experimental results are consistent with the diffuse sound field hypothesis in Gm and even with results more appropriate than the values calculated in the diffuse sound field hypothesis in C80m, Tsm, and LJm. This is especially true for sources S3 and S4, which are precisely of a musical nature. The D50m descriptor is also increased for almost all receivers and sources with respect to the diffuse field model. It is only the JLFm parameter, especially for receivers of sources S1 and S2 in the two roof configurations, that deviates negatively from this model. For musical sources S3 and S4, there are numerous receivers that conform to the values of this model. Lastly, for the STI parameter, two-thirds of the receivers are within the fair range of values, and it should be noted that many of the receivers in the poor range correspond to combinations of musical and non-spoken source–receiver pairs (sources S3 and S4).

The acoustic signature of the Lisbon bullring, obtained from the analysis of early reflections using the 3D impulse responses, shows a clear temporal evolution in the distribution of sound energy. In the first intervals (0–20 ms), the response is dominated by direct sound, with a concentration of energy in the mid-frequency range and little influence from the environment. Between 20 and 80 ms, initial reflections from the walls and benches are progressively incorporated, especially in the receivers in the arena and barrier benches, as can also be observed in the 3D vector diagrams, whereby spectral undulations and localised reinforcements are produced in the mid- and mid–high bands, which are associated with interference effects and the contribution of nearby surfaces. From 200 ms onwards, the general attenuation of the spectrum and the loss of high components reflect the onset of energy decay and the transition to a diffuse reverberant field.

Overall, the cumulative frequency response (CFR) curves show a gradual transformation from a predominantly direct field in the areas close to the source to a more homogeneous and diffuse response in the benches and galleries. This temporal and spatial progression constitutes the defining feature of the acoustic signature of the venue, in which the coexistence of a clear direct component and a well-developed reverberant field is recognised, thus determining the particular sound identity of the Lisbon bullring.

Although the acoustic characterisation of this bullring has been focused on bull-fighting rituals, future acoustic simulations based on models calibrated with in situ measurements will enable auralisations and the description not only of events other than bullfighting (e.g., concerts and recitals) but also of the influence of environmental conditions and/or the presence of an audience, as well as including “real” sound sources (e.g., the cornet, other band instruments, and voices).

Furthermore, these acoustic simulations will enable a comparison of the acoustic signature of the bullring in an imaginary absence of a roof, thereby allowing for research into the correct description of acoustics in open spaces.

A future comprehensive analysis of the acoustic conditions of bullrings, with a larger sample, would enable acoustic–architectural recommendations to be made.

The main historical change in the acoustics of this bullring involves the installation of a roof during the 2000–2006 renovation. No acoustic records exist related to the bullring before said roof was installed. The methods introduced in this work to study the acoustics of this historical site establish a valuable archive of its physical state after the roofing. This archive will prove crucial for the preservation of this intangible heritage when the space is eventually refurbished or renovated due to the deterioration of its materials over time, to natural disasters, and/or to accidents. The results herein also serve as a basis for the conservation of sound heritage in other bullrings, theatres, and classical amphitheatres where temporary performances may be held.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.M.-C., S.G. and M.G.; methodology, S.G., M.M.-C. and M.G.; validation, M.M.-C., S.G. and M.G.; investigation, M.M.-C., S.G. and M.G.; resources, M.M.-C., S.G. and M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.G., M.G. and M.M.-C.; writing—review and editing, S.G. and M.G.; supervision, S.G. and M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is available on request from the corresponding authors. The data is not publicly available due to privacy regulations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gerzon, M.A. Recording concert hall acoustics for posterity. J. Audio Eng. Soc. 1975, 23, 569–571. [Google Scholar]

- Abdou, A.; Guy, R.W. Spatial information of sound fields for room-acoustics evaluation and diagnosis. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1996, 100, 3215–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, A.; Tronchin, L. 3D Impulse response measurements on S. Maria del Fiore Church, Florence, Italy. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1998, 103, 3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezina, P. Acoustics of historic spaces as a form of intangible cultural heritage. Antiquity 2013, 87, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, A.; Ayalon, R. Recording concert hall acoustics for posterity. In Proceedings of the AES 24th International Conference Multichannel Audio, Banff, AB, Canada, 26–28 June 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Farina, A.; Tronchin, L. Measurements and Reproduction of Spatial Sound Characteristics of Auditoria. Acoust. Sci. Technol. 2005, 26, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, B.F.G.; Murphy, D.; Farina, A. The past has ears (PHE): XR Explorations of acoustic spaces as cultural heritage. In Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, and Computer Graphics, Proceedings of the 7th International Conference, AVR 2020, Lecce, Italy, 7–10 September 2020; De Paolis, L.T., Bourdot, P., Eds.; Part II. Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Almagro-Pastor, J.A.; García-Quesada, R.; Vida-Manzano, J.; Martínez-Irureta, F.J.; Ramos-Ridao, A.F. The acoustics of the Palace of Charles V as a cultural heritage concert hall. Acoustics 2022, 4, 800–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannace, G. The use of historical courtyards for musical performances. Build. Acoust. 2016, 23, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, M.; Kang, J. Sound field of a traditional Chinese Palace courtyard theatre. Build. Environ. 2023, 230, 109741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almagro-Pastor, J.A.; Vida-Manzano, J.; Ramos-Ridao, A.F. Soundscape approach applied to a heritage open-air concert hall: The case of the Corral del Carbón in Granada. Build. Acoust. 2025, 32, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girón, S.; Álvarez-Corbacho, A.; Zamarreño, T. Exploring the acoustics of ancient open-air theatres. Arch. Acoust. 2020, 45, 181–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindel, J.H. Roman theatres and revival of their acoustics in the ERATO Project. Acta Acust. United Acust. 2013, 99, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianniello, C. Modern shows in Roman amphitheatres. Acoust. Pract. 2017, 6, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Navvab, M.; Bisegna, F.; Gugleirmetti, F. Capturing ancient theaters sound signature using beamforming. In Proceedings of the 23th International Congress on Sound and Vibration, Athens, Greece, 10–14 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua, A.; Ciaburro, G.; Iannace, G.; Lombardi, I.; Trematerra, A. Acoustic design of a new shell to be placed in the Roman amphitheater located in Santa Maria Capua Vetere. Appl. Acoust. 2022, 187, 108524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardi, U.; Bevilacqua, A.; Iannace, G.; Trematerra, A. Virtual acoustic reconstruction of the Roman amphitheater of Avella, Italy. Proc. Meet. Acoust. 2022, 50, 015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, A.; Sukaj, S.; Iannace, G.; Trematerra, A. Insight discovery of the Roman amphitheater of Durres: Reconstruction of the acoustic features of its original shape. Buildings 2023, 13, 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, A.; Sukaj, S.; Iannace, G. How acoustically important is the velarium in Roman amphitheaters? Investigation into the effects of different coverage percentages in Durres and Capua. Build. Acoust. 2024, 31, 377–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, M.; Girón, S.; Cebrián, R. Acoustics of performance buildings in Hispania: The Roman theatre and amphitheatre of Segobriga, Spain. Appl. Acoust. 2020, 166, 107373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 3382-1:2009; Acoustics—Measurement of Room Acoustic Parameters—Part 1: Performance Spaces. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- ISO 3382-2:2008; Acoustics—Measurement of Room Acoustic Parameters—Part 2: Reverberation Time in Ordinary Rooms. Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- Farnetani, A.; Prodi, N.; Pompoli, R. On the acoustics of ancient Greek and Roman theaters. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2008, 124, 1557–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paini, D.; Gade, A.C.; Rindel, J.H. Is Reverberation Time Adequate for Testing the Acoustical Quality of Unroofed Auditoriums? In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Auditorium Acoustics, Dublin, Ireland, 20–22 May 2011; Institute of Acoustics: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011; Volume 28, pp. 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, F.; Wang, J. Why the conventional RT is not applicable for testing the acoustical quality of unroofed theatres. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2012, 131, 3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, E.; Shtrepi, L.; Aletta, F.; Puglisi, G.E.; Astolfi, A. Geometrical Acoustic Simulation of Open-air Ancient Theatres: Investigation on the Appropriate Objective Parameters for Improved Accuracy. In Proceedings of the 16th International Building Performance Simulation Association, Rome, Italy, 2–4 September 2019; pp. 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rindel, J.H. A note on meaningful acoustical parameters for open-air theatres. Acta Acust. United Acust. 2023, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Andreu, M.; Jiménez Pasalodos, R.; Rozwadowski, A.; Alvarez Morales, L.; Miklashevich, E.; Santos da Rosa, N. The soundscapes of the Lower Chuya River area, Russian Altai. Ethnographic sources, indigenous ontologies and the archaeoacoustics of rock art sites. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 2023, 30, 335–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beranek, L.L. Concert and Opera Halls: How They Sound; American Institute of Physics: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 1–643. [Google Scholar]

- Pätynen, J.; Tervo, S.; Lokki, T. Analysis of concert hall acoustics via visualizations of time-frequency and spatiotemporal responses. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2013, 133, 842–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gómez, J.O.; Wright, O.; Van Den Braak, E.; Sanz, J.; Kemp, L.; Hulland, T. On the sequence of unmasked reflections in shoebox concert halls. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Guarinos, J.; Yebra-Calleja, M.; Calzado-Estepa, E.; Brocal-Fernández, F.; Miralles-García, A. Reflexiones sobre reflexiones, eco y reverberación. In Proceedings of the 45° Congreso Español Acústica, 8° Congreso Ibérico Acústica, Murcia, Spain, 29–31 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Briones-Ramos, J.J.; Bernabé-Sanchís, M. Simulación acústica en el diseño arquitectónico. In Proceedings of the 45° Congreso Español Acústica, 8° Congreso Ibérico Acústica, Murcia, Spain, 29–31 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Castizo, M.; Girón, S.; Galindo, M. A proposal for the acoustic characterization of circular bullrings. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2022, 152, 380–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Castizo, M.; Girón, S.; Galindo, M. Acoustic ambience and simulation of the bullring of Ronda (Spain). Buildings 2024, 14, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girón, S.; Martín-Castizo, M.; Galindo, M. Echo analysis in Iberian bullfighting arenas through objective parameters and acoustic simulation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touradas, S.D. História da Tauromaquia. Available online: http://www.touradas.pt/tauromaquia/historia (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Cláudio, S.D. Touradas Portuguesas, uma Tradição Portuguesa, História da Tauromaquia. Available online: https://touradasportuguesas.blogspot.com/p/historia-da-tauromaquia.html (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Henriques da Silva, R.; Elias, M. The Campo Pequeno Bullring in Lisbon’s Avenidas Novas. Conserv. Património 2012, 37, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves-Rodrigues, M.A. Abrir Praça: A Arquitectura das Praças de Touros em Portugal. Master’s Thesis, Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall Day IRIS Software. User’s Manual v1.2 Marshall Day Acoustics. 2018. Available online: https://www.iris.co.nz/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- EASERA. Electronic and Acoustic System Evaluation and Response Analysis (EASERA) v1.1 AFMG Technologies GmbH, Germany. Available online: https://www.afmg.eu/en/afmg-easera (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- IEC 60268-16:2020; Sound System Equipment—Part 16: Objective Rating of Speech Intelligibility by Speech Transmission Index. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Dietsch, L.; Kraak, W. Ein objektives Kriterium zur Erfassung von Echostörungen bei Musik- und Sprachdarbietungen (An objective criterion for detecting echo interference in music and speech performances). Acustica 1986, 60, 205–216. [Google Scholar]

- Vorländer, M. Auralization, Fundamentals of Acoustics, Modelling, Simulation, Algorithms and Acoustic Virtual Reality; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, J.S.; Reich, R.; Norcross, S.G. A just noticeable difference in C50 for speech. Appl. Acoust. 1999, 58, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, F.R. Acoustics of Buildings; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1923. [Google Scholar]

- Arau-Puchades, H. ABC de la Acústica Arquitectónica; CEAC: Barcelona, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Barron, M. Auditorium Acoustics and Architectural Design, 2nd ed.; Spon Press: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fürjes, A.T.; Nagy, A.B. Tales of More Than One Thousand and One Measurements (STI vs. Room Acoustic Parameters—A Study on Extensive Measurement Data). 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Andor-Fuerjes/publication/341616458_Tales_of_more_than_One_Thousand_and_One_Measurements_STI_vs_room_acoustic_parameters_-a_study_on_extensive_measurement_data/links/5ecb7e40a6fdcc90d696fb52/Tales-of-more-than-One-Thousand-and-One-Measurements-STI-vs-room-acoustic-parameters-a-study-on-extensive-measurement-data.pdf?__cf_chl_tk=mvpNGJzqLGqBuQ1GlDkmVeUBztf_zSTXllcjFXM7uMQ-1767576879-1.0.1.1-wt3lemfOS6Ndpg0cLhi497x_szeWa2dfLb._SvuVwiQ (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Zamarreño, T.; Girón, S.; Galindo, M. Acoustic energy relations in Mudejar-Gothic churches. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2007, 121, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, J.S. Review of objective room acoustics measures and future needs. Appl. Acoust. 2011, 72, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girón, S.; Galindo, M.; Zamarreño, T. Distribution of lateral acoustic energy in Mudejar-Gothic churches. J. Sound Vib. 2008, 315, 1125–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.