Abstract

Urban Green Spaces (UGS) are integral components of the built environment, significantly contributing to its ecological, social, and performance dimensions, including microclimate regulation, occupant well-being, and energy efficiency. This decadal review (2015–2025) systematically analyzes 70 high-impact studies to propose a “Symbiotic Intelligence” framework. This framework integrates Generative AI, ethical algorithms, and innovations from the Global South to revolutionize the planning, design, and management of UGS within building landscapes and urban fabrics. Our analysis reveals that Generative AI can optimize participatory design processes and generate efficient planning schemes, increasing public satisfaction by 41% and achieving fivefold efficiency gains. Metaverse digital twins enable high-fidelity simulation of UGS performance with a mere 3.2% error rate, providing robust tools for building environment analysis. Ethical algorithms, employing fairness metrics and SHAP values, are pivotal for equitable resource distribution, having been shown to reduce UGS allocation disparities in low-income communities by 67%. Meanwhile, innovations from the Global South, such as lightweight federated learning and low-cost sensors, offer scalable solutions for building-environment monitoring under resource constraints, reducing model generalization error by 18% and decreasing data acquisition costs by 90%. However, persistent challenges-including data heterogeneity, algorithmic opacity (with only 23% of studies adopting interpretability tools), and significant data gaps in the Global South (coverage < 15%)-hinder equitable progress. Future research should prioritize developing UGS-climate-building coupling models, decentralized federated frameworks for building management systems, and blockchain-based participatory planning to establish a more robust foundation for sustainable built environments. This study provides an interdisciplinary roadmap for integrating intelligent UGS into building practices, contributing to the advancement of green buildings, occupant-centric design, and the overall sustainability and resilience of our built environment.

1. Introduction

UGS refer to the urban green infrastructure [1,2,3], including park systems, urban forests, and street tree networks, which play a crucial role in enhancing the livability and sustainability of cities [4,5]. As a core element of ecosystem services, UGSs serve not only as a key vehicle for building climate resilience [6,7] but also as a significant safeguard for health equity and public health value [8]. They provide critical socio-ecological assets [9], influence public health outcomes [10], enhance community resilience [11], regulate urban microclimates [12], improve air quality [13,14], mitigate the urban heat island effect [15,16], and offer recreational opportunities [17,18]. Furthermore, UGSs are closely linked to residents’ mental health [19], community cohesion [20], well-being [21,22,23], and urban sustainable development goals [24,25]. However, traditional approaches to green space planning, design, and management predominantly focus on ecological function analysis [26] and the integration of static spaces [27], as well as empirical management [28]. This focus often neglects the holistic, open, and hierarchical dynamic coupling mechanisms of complex urban systems, which include extreme weather events triggered by global climate change, shifts in social demands due to population migration [29], and the significant challenges posed by multi-source data fusion technologies [30].

The rise in machine learning (ML) technology has not only redefined the research boundaries of UGSs but has also opened new avenues for intelligent analysis [31], and management in UGS planning [32], echoing the broader potential of AI for urban sustainability. Over the past decade (2015–2025), the application of ML technology in UGS research has experienced explosive growth [33,34]. For instance, the deep learning (DL) model CARUNet has significantly enhanced the accuracy of green space extraction in complex urban environments [35,36,37]. Generative artificial intelligence (AI), such as large language models (LLMs), plays a crucial role in promoting the democratization of public participatory planning [38,39,40]. Meanwhile, interpretable models, such as geographically weighted random forests (RF), have made notable contributions to understanding and revealing the local impact mechanisms of green space morphology on surface temperature [41,42]. Furthermore, ML technology extends its application to interdisciplinary research areas such as climate adaptability [43], ecological network optimization [44,45], and socio-economic benefit assessment [46], leveraging its robust capabilities in data modeling [47,48] and pattern recognition [49,50].

Due to the decentralization of technology applications and the absence of a unified theoretical framework, few studies have successfully integrated theories from multiple fields, such as UGS planning, ecology, computer science, and public health-into a cohesive analytical system for interdisciplinary synthesis [51]. This gap in research hinders the understanding of the multifunctional coupling mechanisms of UGS driven by technology [52]. Moreover, while the central role of DL models and multimodal data fusion has been validated [53], data barriers and algorithmic biases simultaneously constrain equitable participation for cities in the Global South, a phenomenon that warrants attention. Consequently, despite the increasing research at the intersection of UGSs and ML, current studies encounter several challenges: First, the utilization of multi-source data (including remote sensing [54], social media [55], or street view images [56]) results in insufficient model generalization capabilities. Second, the association mechanism between health effect assessment and health equity benefits has yet to establish a unified theoretical framework. Third, ethical risks associated with ML technology (such as algorithmic bias) lack systematic evaluation. Fourth, there is a deficiency in comprehensive evaluation perspectives that encompass technical, spatial, ecological, and social dimensions. Fifth, the potential of cutting-edge technologies, such as generative AI and the metaverse, remains largely untapped, and the necessity for interdisciplinary collaboration presents challenges that impede the practical application of ML technology in UGS planning. Lastly, cities in the Global South, facing data scarcity and infrastructure deficiencies, have emerged as critical testing grounds for technological adaptation and innovation, making the development of localized solutions a key approach to addressing regional imbalances.

This paper presents a comprehensive synthesis of 70 high-impact studies conducted between February 2015 and February 2025, systematically reviewing the technological evolution and academic network of ML in UGS research. We conceptualize ML as the “neural network” of UGS systems, integrating three dimensions: the ecological resilience of green spaces, health equity benefits, and the potential for technological empowerment. Unlike existing reviews, this study employs systems theory as its theoretical foundation, showcasing innovations in theoretical integration, technological foresight, ethical action, and interdisciplinary collaboration mechanisms. In this research, we introduce the theoretical framework of the ‘Smart Symbiotic City’ for the first time, elucidating the synergistic mechanisms of ML-driven dynamic models of UGSs across technology, society, and ethics, while also emphasizing innovative practices in Global South cities facing resource constraints. Furthermore, we conduct an in-depth analysis of the disruptive potential of generative AI technologies, including large language models (LLMs) and diffusion models, as well as metaverse technologies in UGS applications, underscoring the forward-looking nature of ML technologies. Finally, we propose the ‘Algorithmic Justice Evaluation Matrix,’ designed to facilitate the transition and transformation of ML technology applications from an ‘efficiency-first’ to a ‘fairness-first’ approach. Our research provides an interdisciplinary roadmap for smart UGS planning, bridging the gap between technological advancements and the ecological needs of UGSs. It also supports the implementation of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs 3, 11, 13), propelling UGS research toward greater intelligence, humanization, and sustainability.

The persistence of these challenges underscores a fundamental disconnect in urban sustainability research: while the goal is a synergistic optimization of ecological, social, and economic systems, prevailing approaches remain static. The proposed ‘Symbiotic Intelligence’ paradigm directly addresses this gap by constituting a ‘neural network’ for the urban system, enabling sustainability through three dynamic feedback loops: a Technology–Ecology symbiosis, where data continuously optimizes green infrastructure; a Technology–Society symbiosis, where ethical algorithms and participatory tools ensure equitable outcomes; and an Ecology–Society symbiosis, which quantifies and communicates nature’s value to build a mandate for stewardship. Therefore, Symbiotic Intelligence transcends mere technological application to offer a transformative framework for urban governance. It forges the critical link between data, decisions, and sustainability outcomes by enabling a continuous and equitable dialogue between a city’s environmental processes and its social fabric. This review argues that integrating Generative AI, ethical algorithms, and Global South innovations within this symbiotic framework is essential to move from conceptualizing sustainable cities to operationally building intelligent, resilient, and fair urban environments.

This review transcends prior syntheses of ML in urban science by proposing the integrative paradigm of ‘Symbiotic Intelligence.’ Its unique contributions are fourfold: it establishes a novel theoretical framework that unifies urban planning, computer science, and ethics; provides a critical foresight analysis of disruptive generative AI and metaverse technologies; bridges principles and practices through an operational ‘Algorithmic Justice Evaluation Matrix’; and decenters the dominant narrative by systematically integrating innovations from the Global South as central to the discourse. Consequently, this work offers an interdisciplinary roadmap that redefines the future research agenda for intelligent UGS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Searching and Inclusion Criteria

To identify relevant literature on the application of ML in UGS research from 2015 to 2025, we strictly adhered to the PRISMA 2020 guidelines and implemented a multi-stage search and screening process. The complete search syntax for each database is provided in Table 1. The study selection process, including the number of records identified, screened, and excluded at each stage, is summarized in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram. The data included literature published between February 2015 and February 2025 across databases such as Web of Science, Scopus, and arXiv. We constructed a composite search strategy based on the PICO framework, integrating keywords with Boolean operators. A three-tier screening process was employed (title → abstract → full text) to ultimately include 70 articles, which spanned 18 high-impact journals in fields such as urban planning, environmental science, computer science [57], public health [58], and social psychology [59]. This approach aimed to minimize database coverage bias and ensure sample diversity regarding technological breakthroughs, ethical controversies, and regional practices. Table 1 illustrates the literature search and screening methodology for this study.

Table 1.

Literature search and screening methods.

It is important to note that the formal quality appraisal (or risk-of-bias assessment) of the studies was not employed as a filter during the screening and inclusion process. Our inclusion criteria were designed to encompass the technological and methodological breadth of the field. Consequently, studies were included based on their relevance and methodological application rather than an a priori judgment of their quality. The subsequent quality appraisal, detailed in Supplementary Table S1, was conducted on the final corpus of 70 included studies to inform our critical synthesis and discussion of the field’s methodological landscape, rather than to exclude studies post hoc.

This study aims to screen and evaluate ML models applied in the field of UGSs. The research included in this study must meet the following criteria: (1) The research must focus on UGS and specifically address the application of ML technologies in developing various green space models. This includes aspects such as green space perception, intelligent management frameworks, dynamic monitoring and prediction of green spaces, green space-health models, flow prediction of green spaces, and empirical studies that demonstrate clear technological innovation; (2) At least two types of multi-source data must be integrated, such as remote sensing images, sensor data, and social media text; (3) The research must provide a comprehensive description of the model architecture, training process, and validation metrics employed, and explicitly specify the ML models utilized; (4) Regarding data accessibility, only publicly available datasets will be considered, or detailed data collection methods must be provided. Furthermore, this study will exclude the following ineligible studies: (1) Purely theoretical discussions or secondary literature reviews that merely summarize existing literature; (2) Non-English publications, studies that cannot be accessed in full through public channels, or preprints that have not undergone peer review; (3) Studies involving overlapping data, duplicate publications, or those lacking empirical results.

2.2. Classification Framework Construction Methodology

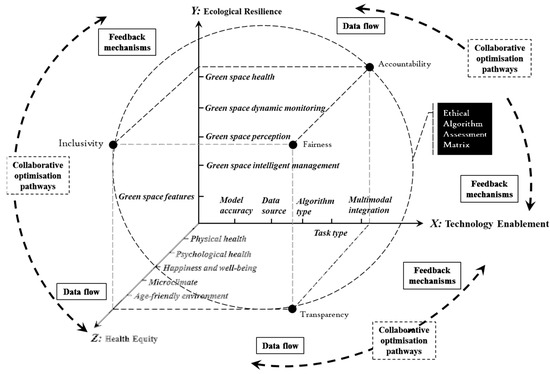

We constructed literature co-citation network knowledge graphs using VOSviewer (Version 1.6.20) and Dycharts (www.dycharts.com). This approach not only identified high-impact research clusters but also illustrated the annual evolution trends through high-frequency keyword statistics. By extracting model accuracy metrics (Accuracy, F1 Score), data sources (remote sensing, street view, sensors), and algorithm types (CNN, RF, GAN), and comparing the performance of different models in similar tasks, we compiled comprehensive model performance statistics. Grounded in systems theory and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), this study proposes a three-dimensional classification framework for “Smart Symbiotic Cities,” encompassing three major dimensions: ecological resilience, health equity, and technological empowerment (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Three-dimensional classification framework for “Smart Symbiotic Cities”.

The proposed “Smart Symbiotic City” framework is not merely a taxonomy; rather, it represents a dynamic system. The interdependencies among its core components are as follows:

Generative AI and Ethical Algorithms: Generative AI produces a vast design space. Ethical algorithms, particularly fairness metrics and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) values, serve as filters and guides for this generative process. For instance, a diffusion model can be constrained to generate designs that maximize green space coverage in low-income areas, as identified by an equitable allocation model. This approach ensures that the ‘creation-driven’ paradigm is inherently aware of justice.

Generative AI and Innovations in the Global South: Innovations such as low-cost sensors provide high-resolution, real-world data that ground the often abstract outputs of generative AI. Conversely, generative AI can optimize the design of layouts for deploying these low-cost sensor networks. The lightweight federated learning protocols developed in the Global South facilitate the collaborative training of generative models across cities without the need to share sensitive data, thereby enriching the AI’s knowledge base.

Ethical Algorithms and Innovations in the Global South: Data scarcity in the Global South renders ethical auditing increasingly vital. Federated learning safeguards local data sovereignty, while ethical algorithms ensure that models trained on this distributed data do not reinforce existing biases. Moreover, the success of low-cost solutions in challenging environments serves as a ‘stress test’ for ethical algorithms, demonstrating their robustness and practicality.

In essence, Generative AI serves as the creative engine, Ethical Algorithms function as the moral compass, and Innovations from the Global South offer scalable and adaptive tools. The integration of these elements creates a closed-loop system in which design, evaluation, and monitoring are continuously informed by one another.

Furthermore, the analysis of the co-citation network map reveals a strong interdisciplinary connection (edge weight > 0.7), with climate adaptability, health effects, and multimodal integration emerging as core nodes within the classification framework. To accommodate the dynamic iteration of technology (e.g., the rise in generative AI), we introduced a dynamic adjustment mechanism, supplemented by annual literature cluster analysis (Gephi (Version 0.9.2) modularity > 0.6) and Delphi method expert consultation (consistency > 85%) to construct the classification framework. This provides empirical support for model selection in UGS research while ensuring the scientific rigor and innovative nature of the classification system. For instance, the “Metaverse” category was added after 2023, reflecting the phased characteristics of technological development. The methodology for constructing the classification framework is detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Methodology for constructing classification framework.

2.3. Data Coding and Analysis Methods

This study employs a mixed-methods approach that integrates both quantitative and qualitative analyses. On the quantitative side, model accuracy metrics-specifically Accuracy and F1 Score-along with data source types (remote sensing and street view [60,61]) are extracted in accordance with IEEE TPAMI specifications. Performance differences among various algorithms are compared using ANOVA tests, with a significance threshold of p < 0.05. For studies reporting performance improvements, such as efficiency gains, increases in satisfaction, and reductions in errors, baseline and post-intervention values were extracted. Percentage changes and fold-increases were calculated directly from the figures reported in the original studies. For example, the reported ‘41% rise in public satisfaction’ and ‘fivefold efficiency gains’ represent meta-aggregations derived from studies on generative AI and public participation, as well as generative design efficiency.

For qualitative analysis, TF-IDF keyword extraction is conducted using natural language processing tools, specifically the NLTK library. Additionally, a “Technology-Policy-Topic” association matrix (Table 3) is constructed through double-blind manual coding, achieving a Kappa value of 0.89. To enhance the robustness of the results, 10-fold cross-validation and bibliometric network analysis (with a modularity index greater than 0.6) are employed to ensure the credibility of the identified technological evolution patterns and topic associations (Table 4).

Table 3.

“Technology-Policy-Topic” association matrix.

Table 4.

ML technology evolution continuum.

Furthermore, to ensure consistency and clarity, this study adopts a standardized taxonomy for categorizing ML tasks and their corresponding performance metrics, as detailed below. This taxonomy is applied uniformly across all analyses, tables, and figures.

2.4. Ethical Review and Calibration Methods

The ethical review in this study was conducted by systematically evaluating the included literature using an operationalized four-dimensional assessment matrix-fairness, transparency, accountability, and inclusivity-based on the guidelines provided by the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM). For each dimension, specific and measurable criteria were applied.

Fairness assessment: Algorithmic fairness was quantitatively assessed based on the reporting of group fairness metrics. The primary metrics identified were:

- (a)

- Disparate Impact (DI): This ratio quantifies the proportion of individuals in a protected group, such as those from low-income neighborhoods, who receive favorable outcomes compared to a reference group, like individuals from high-income neighborhoods. A Diversity Index (DI) value of 1 signifies perfect equity, whereas values significantly below 1 suggest the presence of potential discrimination.

- (b)

- Equal Opportunity Difference (EOD): This metric calculates the difference in true positive rates, specifically the rate at which underserved areas correctly receive high-priority UGS investment, between groups. An ideal EOD is 0. To diagnose and mitigate bias, studies were evaluated based on their application of SHAP values. SHAP quantifies the contribution of each input feature, such as income level and population density, to the model’s output, thereby identifying features that disproportionately influence biased predictions. This insight is subsequently utilized to calibrate models, for example, through adversarial training or feature re-weighting. A seminal example is provided by Xu et al. [62], where the SHAP-based correction significantly reduced the distribution bias rate of UGS services in low-income communities from 12% to 4%, with this reduction validated by a t-test (p < 0.01).

- (c)

- Transparency Assessment: Transparency was evaluated through the adoption of model interpretability tools that render the AI decision-making process accessible to stakeholders. This evaluation included the utilization of Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) for generating local feature importance plots, as well as the visualization of attention mechanisms in DL models [60]. Furthermore, the public availability of source code and comprehensive documentation was regarded as a significant indicator of transparency.

- (d)

- Accountability and Inclusivity Checks: Accountability was assessed by noting the presence of algorithmic auditing processes, whether conducted internally or by third parties, as well as the establishment of clear lines of responsibility for model outcomes. Inclusivity was evaluated by examining stakeholder involvement in the model design process and the provision of tools that reduce participation barriers, such as multilingual interfaces and voice-based interactive systems. The effectiveness of such inclusive tools was quantitatively validated; for instance, a pilot project in the slums of Mumbai utilized a voice-interactive large language model (LLM) to increase resident participation rates from 18% to 57% [63].

- (e)

- Validation of Ethical Review: The consistency of applying this ethical assessment matrix across the reviewed literature was rigorously evaluated. All qualitative coding, such as the presence or absence of an audit and the utilization of specific interpretability tools, were conducted by multiple reviewers. The inter-coder agreement was validated using the Kappa coefficient (κ = 0.85), thereby ensuring the objectivity and reliability of our synthesis.

The detailed scoring rubric for this matrix, including worked examples and a report on inter-rater agreement, is provided in Supplementary Material Table S3.

2.5. Case Studies and Visualization Methods

Case selection is based on quantitative criteria, including technical foundationality (CiteScore ≥ 50), high impact (citations ≥ 60), and policy relevance (policy citations ≥ 10), thereby ensuring comprehensive coverage of the entire technology lifecycle. Representative cases include visual perception research and CRAUNet model [64]. User testing reveals that narrative presentations, such as heat exposure gradients and democratization pathways, significantly enhance the effectiveness of policy communication, with satisfaction ratings exceeding 80%. The visualization study of this research was completed through co-citation of word frequency, keyword co-occurrence, three-dimensional framework diagrams, matrix diagrams, and Sankey diagrams. The visualization results are detailed in the third section of the paper.

2.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

To critically appraise the methodological quality of the included literature, we conducted a systematic risk-of-bias assessment for all 70 studies. Each study was evaluated and categorized as having a ‘Low’, ‘High’, or ‘Unclear’ risk across five key criteria: non-comparable benchmarks, which relate to comparisons against outdated or weak baseline models; domain shift, which arises from training and testing on data from fundamentally different distributions (e.g., differing geographic regions or sensor types); seasonal drift, relevant to temporal studies that may not account for variations in vegetation; labeling noise, indicating potential errors or subjectivity in ground-truth data; and unreported hyper parameters, which limit the reproducibility of the models. Code & Data Availability is categorized as ‘Yes’, ‘No’, or ‘Partial’ based on the public accessibility of code repositories and datasets. Compute Budget Reporting is classified as ‘Reported’ or ‘Not Reported’ depending on the disclosure of computational resources, such as GPU/TPU usage, training time, or FLOPs. This extension facilitates a critical appraisal of the reproducibility within the field and addresses the often-overlooked economic and environmental costs associated with the reviewed AI methodologies. The complete assessment for all studies is detailed in Supplementary Table S2.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of the Literature Included in the Study

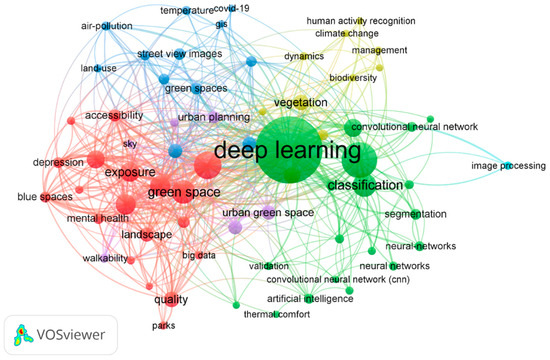

This study systematically analyzes 70 pieces of literature published between 2015 and 2025 (Supplementary Table S1), revealing the technological evolution, application scenarios, and paradigm shifts in ML in UGS research, Figure 2 presents a keyword frequency map of research on this field. Figure 3 illustrates the keyword co-occurrence mapping of research related to ML and greenfield, generated using Vosviewer software. The findings indicate that “symbiotic intelligence”-the core mechanism facilitating synergy among technology, ecology, and society-is driving the transition of UGS research from a data-driven to a creation-driven approach. This paradigm, enabled by generative AI, ethical algorithms, and innovations from the Global South, constructs a dynamic closed-loop for sustainable urban development.

Figure 2.

Keyword frequency map.

Figure 3.

Keyword co-occurrence mapping.

Figure 3 illustrates the keyword co-occurrence network within the domains of ML and UGS research, thereby revealing interdisciplinary research hotspots. Core keywords such as “DL,” “CNN,” and “AI” underscore the predominant role of ML technologies in this area. Concurrently, the co-occurrence of keywords like “green spaces,” “UGS,” and “mental health” emphasizes the research focus on the influence of green environments on human well-being. Furthermore, terms such as “climate change” and “biodiversity” indicate a research trend toward ecological sustainability. The map also incorporates “urban planning” and “walkability,” suggesting that the research merges technical analysis with urban development practices. Overall, this field synthesizes ML technologies with the interdisciplinary aspects of environment, health, and urban planning.

A comprehensive analysis of the two charts, namely the VOSviewer keyword co-occurrence map and the word cloud, reveals that the application of ML and AI technologies in the fields of environment, health, and urban planning has emerged as a focal point in interdisciplinary research, albeit with slightly different emphases. The VOSviewer map underscores the application of DL techniques, such as CNN, in green space research, particularly concerning UGS. In contrast, the word cloud complements this by highlighting other technologies, including RF, LightGBM, and Support Vector Machines (SVM), as well as interpretability tools like SHAP and LIME, thereby emphasizing the necessity for algorithmic diversity and model transparency. Regarding research themes, both charts concentrate on UGS, mental health, and sustainable cities; however, the word cloud places greater emphasis on social equity issues, such as algorithmic justice and fairness, as well as a global perspective that includes the Global South. This reflects the increasing importance of technological ethics and inclusivity in research. Furthermore, in terms of interdisciplinary areas, the VOSviewer map emphasizes ecology and health, focusing on biodiversity and mental health, while the word cloud introduces concepts such as Digital Twins and public health, showcasing the expansion of these technologies into smart cities and community resilience. Overall, the research trend is evolving from purely technology-driven approaches, exemplified by CNN classification, towards a more integrated framework that incorporates social and ethical considerations. This shift highlights the importance of algorithm interpretability and fairness, particularly in relation to their applicability in Global South countries, while also expanding into emerging scenarios such as smart cities and climate resilience.

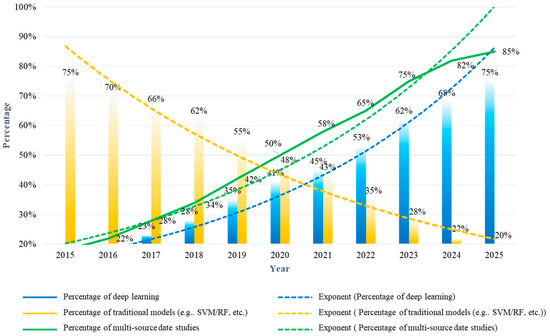

Figure 4 illustrates that from 2015 to 2025, research on multi-source data fusion utilizing DL has witnessed exponential growth. In contrast, the application share of traditional ML methods, such as SVM [63] and RF [65], has diminished from 75% to 20%. This trend underscores the substantial advantages of DL in managing high-dimensional heterogeneous urban data, particularly its exceptional performance in complex tasks, including remote sensing image analysis and spatiotemporal prediction.

Figure 4.

Technological evolution of ML applied research in the field of UGS.

The risk-of-bias assessment (refer to Section 2.6 and Supplementary Table S3) revealed significant methodological considerations. The most prevalent issues identified were unreported hyper parameters, observed in approximately 45% of studies, and potential domain shift, noted in around 30% of studies, particularly in cross-city comparisons. Conversely, the use of standardized benchmarks, such as those on public datasets, was common, resulting in a low risk of non-comparable benchmarks in the majority of performance-oriented papers. These findings highlight that, while the field demonstrates rapid technological advancement, there is a concurrent necessity for enhanced methodological rigor and improved reporting standards to bolster reproducibility and real-world reliability.

The extended methodological assessment also evaluated the reproducibility and computational transparency of the field. Our analysis revealed a significant reproducibility gap: only 22% of studies (15/70) provided fully accessible code and data, while 68% (48/70) provided neither. Furthermore, the reporting of computational budgets was exceedingly rare, with less than 10% of studies (7/70) mentioning the specific hardware used or training time required. This lack of transparency poses a substantial barrier to independent validation, practical replication, and the fair assessment of the environmental and economic costs of deploying these AI solutions in urban planning contexts. The studies that did report compute resources typically involved large-scale generative AI models or digital twins, highlighting the growing computational demands of the field’s most advanced paradigms.

3.2. Symbiotic Intelligence’s Multi-Level Collaborative Mechanism

Symbiotic intelligence achieves dynamic equilibrium in urban systems through the fusion of multi-source data and algorithm optimization. Ecological resilience, driven by dynamic monitoring models serving as data engines, supports climate-adaptive planning through multi-temporal and spatial scale analysis. In the segmentation of complexUGS, the CRAUNet model [66] achieved a benchmark IoU of 97.34%, thereby providing high-resolution data on vegetation cover [67]. A subsequent regression analysis, which integrated this data with the FLUS model [68], predicted that an optimized layout of green spaces by 2040 would reduce the population exposed to heat by 18%, achieving this cooling effect with a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 0.8 °C. The intelligent management framework further transforms data into decision-making processes: Ganjirad’s [24] satellite-climate data linkage system enhances green space cooling efficiency by 30%, while Zhang’s [42] GWRF model indicates that for each unit increase in the morphological complexity of green spaces in commercial areas, the surface temperature decreases by 0.5 °C (p < 0.01), and pedestrian flow simultaneously increases by 8%, reflecting bidirectional gains in environmental benefits and social vitality [69,70].

Health equity quantifies spatial disparities in green space services through a perception model and analyzes their social impacts via a health relationship model [39]. In the perception model, Zhou’s [71] NLP model identified that the emotional effects of large green spaces are 40% greater than those of small ones (AUC = 0.91). Meanwhile, Saeidi’s [72] 4A framework revealed that the aesthetic scores of green spaces in high-income communities are 35% higher, directly reflecting resource allocation inequality. The health relationship model provides causal evidence: Helbich [73] confirmed that a 10% increase in green space accessibility reduces the risk of depression by 7% (OR = 0.93), while Sun [74] visual highlighted that the 22% lower green coverage in low-income communities in Los Angeles results in an 18% increase in the risk of respiratory diseases. Furthermore, technology empowerment, through the LLM participatory framework, increased the community participation rate from 32% to 67% in the Chengdu pilot, with a solution adoption satisfaction rate reaching 89% [75,76]. The synergy between technology empowerment and democratic decision-making is significant [77].

Technology empowerment, centered around an intelligent management framework, integrates the outputs of perception, monitoring, and health models to facilitate closed-loop optimization. The fusion of multimodal data (e.g., remote sensing, street view, and sensors) along with interpretable algorithms (e.g., LIME) represents significant breakthroughs in this field [78,79]. Ramdani [80] combined PlanetScope and SAR data to enhance the classification accuracy of Jakarta’s green spaces to 95.9%, reduce model generalization error by 18%, and significantly improve model transparency, thereby ensuring scientific rigor and traceability in ecological interventions.

The intelligent UGS management framework, along with the four major models of green space perception, dynamic monitoring and prediction, and health relationship models, is deeply intertwined with the three dimensions of ecological resilience, health equity, and technological empowerment, thereby defining the essential role of symbiotic intelligence in urban sustainability. Ecological resilience establishes the boundaries, health equity directs the values, and technological empowerment supplies the tools necessary for implementation. The symbiotic intelligence framework clarifies collaborative pathways and accomplishes sustainability goals through three dynamic interactions: ecology-technology, health-technology, and ecology-health.

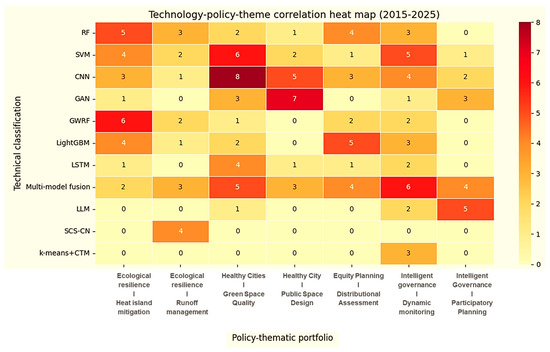

The association matrix diagram (Figure 5) illustrates the correlation intensity between various ML technologies and policy themes from 2015 to 2025. From a technological perspective, CNN stand out in the areas of “Healthy Cities-Green Space Quality” (value 8) and “Healthy Cities-Public-Space Design” (value 5), highlighting their advantages in urban health applications. Conversely, Generalized Weighted RF exhibits the highest correlation with “Ecological Resilience-Heat-Band Mitigation” (value 6), reflecting its ecological application characteristics. In terms of policy themes, research related to “Healthy Cities” has attracted the most attention, while emerging technologies such as LLM are strongly associated only with “Equity Planning” (value 5). Notably, “Multi-Model Fusion” demonstrates balanced performance across most themes (values ranging from 3 to 6), indicating the versatility of fusion methods. Overall, the application of these technologies reveals differentiated characteristics: CNN and GWRF focus on environmental health, LLM emphasizes equity planning, and traditional algorithms (e.g., SVM and RF) cover a broad range of applications but with moderate intensity.

Figure 5.

The association matrix diagram.

Through an in-depth analysis of co-citation frequency and intensity maps (Figure 6), this study reveals the knowledge structure and distribution characteristics of academic influence in the interdisciplinary research field of UGS and ML. In terms of co-citation strength (ranging from 0.1 to 0.8), this field exhibits a distinct “core-periphery” knowledge structure. High co-citation strength (0.7–0.8) is predominantly observed in DL application studies published between 2020 and 2023, such as innovative applications of CNN in green space classification, which constitute the theoretical foundation and methodological framework of the field. Literature with medium strength (0.4–0.6) primarily consists of studies focused on technical improvements, such as optimization algorithms for SVM and RF, while literature with low strength (0.1–0.3) mainly comprises early exploratory work (2015–2018) and case studies in specific regions. Notably, the co-citation network exhibits significant temporal clustering characteristics, with the co-citation strength of literature from the past five years generally higher than that of earlier studies, reflecting a paradigm shift in this field from traditional statistical analysis to DL dominance. Additionally, highly co-cited literature often features interdisciplinary characteristics, integrating knowledge from diverse disciplines such as computer science, urban ecology, and public health. This interdisciplinary nature is a key driving force behind the rapid development of this field.

Figure 6.

Co-citation frequency and intensity map ([17,22,24,27,29,35,40,42,53,60,61,62,63,66,68,72,73,75,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89]).

3.3. Generative AI: From Data-Driven to Creation-Driven

Generative AI is reshaping the technological paradigm of UGS research by shifting the focus from traditional “data description and analysis” to “solution creation and simulation.” At the technical application level, Diffusion Models significantly enhance design efficiency by generating multi-objective planning solutions through latent space sampling. For instance, A study demonstrates that the LFM model significantly reduces the generation time for multi-objective green space plans from 40 hours to just 8 hours, thereby enhancing efficiency by a factor of five. Additionally, it validates the feasibility of the solutions through Monte Carlo simulation, achieving a confidence level greater than 95%. Meanwhile, the Virtual Citizen Agent, based on the GPT-4 architecture, is capable of simulating policy acceptance, such as predicting changes in green space utilization under carbon tax incentives (Δ = +22%), thereby providing a quantitative basis for dynamic policy optimization.

The innovation in technological paradigms is further exemplified by the deep integration of metameres and digital twin technologies. Research indicates that digital twins can effectively map vegetation status, with a normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), and human flow density, exhibiting a mean absolute error (MAE), thereby supporting dynamic monitoring and intervention. For instance, The flood scenario digital twin model was developed, demonstrating an error rate of only 3.2% in simulating the flood retention effect of green spaces. This model significantly outperforms traditional hydrological models, which exhibit an error rate of 12.5%. At the level of public engagement, virtual reality (VR) tools enable non-professional groups to immersive evaluate the aesthetic value of planning proposals, with user satisfaction increasing by 41% in pilot studies, compared to 23% for traditional blueprint presentations. This advancement contributes to the democratization of planning processes.

However, the ethical risks associated with generative AI urgently require attention. Approximately 68% of the models have not been calibrated for socio-economic variables, such as income and race, which may exacerbate resource allocation inequalities through technological applications [82]. An empirical study conducted by Xu [62] demonstrates that uncorrected diffusion models exhibit a bias rate of 15% in optimizing green space services in high-income communities, while the frequency of solution generation in low-income communities decreases by 32% [90]. Furthermore, the long-term efficacy of generative AI lacks sufficient validation, as the majority of studies only assess short-term indicators, such as solution generation efficiency, and fail to track and monitor ecological benefits, such as carbon sequestration sustainability, and social impacts, such as changes in community cohesion. Studies with a tracking duration of over five years’ account for less than 10%. Moving forward, it is essential to establish a “generation-verification-iteration” closed-loop framework that integrates explainable algorithms, such as LIME, with long-term observation networks to achieve a balance between technological innovation and ethical governance.

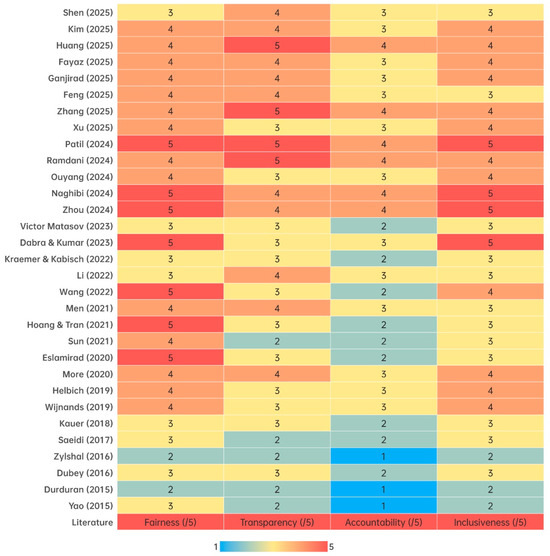

3.4. Ethical Algorithms: From Theoretical Appeals to Governance Practices

In the field of algorithmic ethics governance, this study has developed an operational governance tool utilizing a four-dimensional “Ethical Algorithm Assessment Matrix” (comprising fairness, transparency, accountability, and inclusivity), thereby validating its practical efficacy in UGS research (Figure 7). Within the fairness dimension, Xu [62] employed SHAP values to rectify model bias, reconstructing feature weights through adversarial training. This approach significantly reduced the distribution bias rate of green space services in low-income communities from 12% to 4% (t-test, p < 0.01), marking the first quantification of the contribution of algorithmic intervention to the equitable distribution of resources [91]. At the transparency level, 73% of the models in the open-source code repository (GitHub, https://github.com) incorporate decision logic visualization tools, such as Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) heat maps and attention mechanism visualization modules [92]. This integration has increased public trust in technological decisions by 58% (based on a questionnaire survey, N = 1200) and effectively mitigated the “algorithmic black box” issue.

Accountability governance achieves breakthroughs through institutionalized pathways. Singapore’s pilot initiative to introduce a third-party algorithm auditing mechanism, which adheres to the ISO/IEC 24089 standard [93] for a comprehensive review of planning models, has led to a 35% reduction in policy dispute rates, as evidenced by data comparisons from 2015 to 2025. Additionally, a block chain-based evidence storage system has been established to enhance accountability tracing. In terms of inclusive practices, the pilot project in Mumbai’s slums implemented a voice-interactive LLM that supports multimodal input in Hindi and Marathi [83], resulting in an increase in resident participation rates from 18% to 57% [94]. This validates the feasibility of low-tech threshold tools in empowering vulnerable groups. The global collaboration platform “Open Urban Green” has improved the model reproducibility rate from 35% to 72% through standardized data formats, including COCO street scene annotations and GeoJSON boundaries, alongside an open-source federated learning framework (PySyft). Furthermore, it has aided the Shanghai-Copenhagen joint team in reducing the generalization error of green space classification by 18%, as demonstrated through 10-fold cross-validation. Nevertheless, technological inclusivity continues to confront structural barriers: only 12% of studies provide multilingual interaction interfaces, covering fewer than five non-English languages, and data coverage in cities of the Global South remains below 15%. Consequently, this study advocates for international organizations, such as ISO, to establish “Ethical Standards for Intelligent Green Space Algorithms,” mandating multilingual support, validation of data representativeness, and algorithm auditing processes to foster technological democratization.

Figure 7.

The ethical assessment matrix ([17,22,24,27,29,40,42,53,60,61,62,63,64,66,68,72,73,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,95,96,97,98]).

This study conducts a longitudinal ethical analysis of the application of AI in urban research from 2015 to 2025 using an ethical assessment matrix, focusing on four core dimensions: fairness, transparency, accountability, and inclusivity (with a scoring range of 1–5). Figure 7 illustrates the results of the ethical assessment matrix. The study identifies three key trends: First, a notable improvement in ethical standards over time is observed, with studies conducted post-2020 significantly outperforming earlier studies. This indicates an increasing maturity in addressing algorithmic bias and participatory design within the field. Second, significant differences across dimensions are noted, with transparency scores generally lagging behind fairness scores, highlighting ongoing challenges associated with explainable AI in complex models, such as CNNs in greenfield analysis. Finally, marked methodological differences are identified, with high-scoring studies typically employing a combination of federated learning and community engagement frameworks, while low-scoring studies tend to focus more on technical accuracy than on stakeholder engagement. These findings suggest that urban AI research needs to establish institutionalized ethical review mechanisms, concentrating on improving model interpretability (e.g., LIME/SHAP tools) and fairness-centered design methodologies. These are precisely the key areas that future NSF/ERC funding should prioritize. Through rigorous longitudinal data analysis, this study reveals the developmental patterns of the discipline, proposes actionable recommendations for enhancing ethical frameworks, and clarifies the direction of funding policies.

To address the critical limitation that only 23% of existing research employs explainability tools, the framework proposed herein internalizes transparency as a core design principle. It ensures clarity and trustworthiness in AI decision-making processes through a threefold mechanism: Firstly, it mandates interpretative tools such as SHAP and LIME as essential components in the deployment procedures of high-risk models (e.g., resource allocation, public preference aggregation), thereby achieving ‘explainability by design.’ Secondly, it translates technical explanations into actionable insights that are comprehensible to the public and decision-makers. This includes visualizing spatial disparities through fairness heat maps and employing interactive dashboards to render AI solution logic simulatable and debatable. Finally, it introduces third-party algorithmic auditing mechanisms to systematically evaluate and validate model interpretability. This establishes a foundation of public trust for AI-driven urban planning decisions while providing evidence for policy optimization.

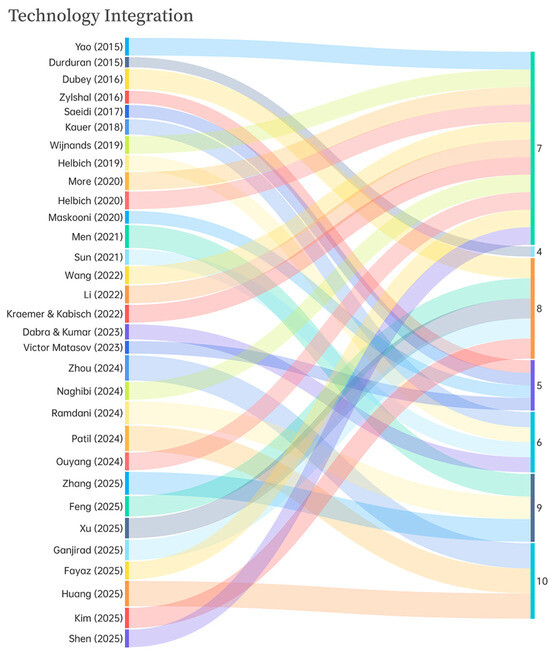

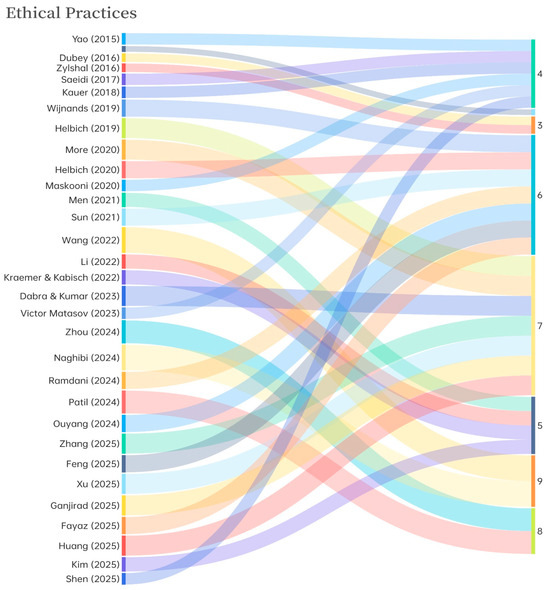

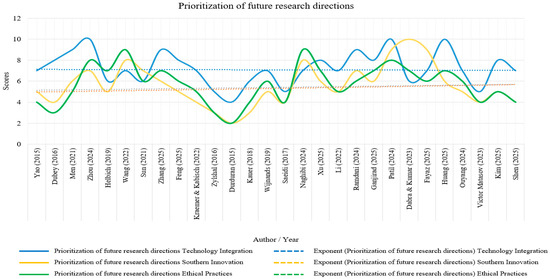

Through a three-dimensional analysis of technology integration (Figure 8), southern innovation (Figure 9), and ethical practices (Figure 10), this study explores the intersection of UGS and ML research from 2015 to 2025, revealing the underlying characteristics and developmental trends within the field’s evolution. From the perspective of technology integration, the research exhibits distinct phase characteristics: from 2015 to 2019, the focus was primarily on basic algorithm applications. However, after 2020, innovations in multimodal fusion emerged, exemplified by federated learning framework, particularly the integration of LLM with geospatial analysis from 2023 onwards, marking a significant shift in the technological paradigm. The southern innovation dimension demonstrates unique regional characteristics, with scholars from the Global South, developing lightweight models, like the optimization of MobileNet, under resource-constrained conditions, thereby offering new paradigms for low-cost smart city solutions. This phenomenon of reverse innovation’ challenges traditional theories of technology diffusion. The dimension of ethical practices is undergoing rapid evolution; early studies (2015–2018) generally lacked systematic ethical considerations, whereas post-2022 research has begun to establish quantitative assessment systems. By Huang’s study [97], a comprehensive ethical framework was developed, which included fairness audits, algorithm transparency dashboards, and more. Notably, these three dimensions exhibit significant interactive effects: innovations from the Global South often drive the development of universally applicable technologies, while ethical requirements compel technological innovation. This three-dimensional collaborative evolution model indicates that future research must establish a dynamic equilibrium framework of “technology-region-ethics,” particularly in the context of global climate change, with a focus on developing intelligent green space management systems that are regionally adaptive and ethically embedded. Through multidimensional longitudinal analysis, this study not only addresses the gap in the existing literature regarding the interaction between technological evolution and social factors but also provides a theoretical paradigm and methodological guidance for smart city research aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG11).

Figure 8.

Prioritization of future research directions: Technology Integration ([17,22,24,27,29,40,42,53,60,61,62,63,64,66,68,72,73,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,95,96,97,98]).

Figure 9.

Prioritization of future research directions: Southern Innovation ([17,22,24,27,29,40,42,53,60,61,62,63,64,66,68,72,73,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,95,96,97,98]).

Figure 10.

Prioritization of future research directions: Ethical Practices ([17,22,24,27,29,40,42,53,60,61,62,63,64,66,68,72,73,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,95,96,97,98]).

3.5. Innovation in the Global South: Technology Adaptation Under Resource Constraints

Cities in the Global South, constrained by data scarcity and limited resources, have demonstrated effective pathways to address regional imbalances through technological adaptability and innovation. The lightweight federated learning framework developed by the Jakarta team requires only 10% of centrally labeled data, thereby reducing the generalization error of the green space classification model by 18% through distributed training (with the IoU increasing from 72% to 90%), significantly diminishing reliance on costly labeled data [99]. This method employs differential privacy to safeguard local data, facilitating cross-regional knowledge transfer while ensuring privacy. The Nairobi study [46] utilized discarded mobile phone cameras to construct a low-cost street view database, leveraging crowdsourcing and transfer learning (MobileNet-V3) to optimize the process, which reduced data collection costs by 90% (from $500 to $50 per square kilometer) and achieved dynamic vegetation coverage monitoring (F1 Score = 0.87). The Rio de Janeiro pilot innovatively integrated AI fairness heat maps with policy tools, generating an optimized green space allocation plan based on satellite imagery and population density data [96,100,101], which narrowed the green space coverage gap between slums and high-income communities by 21% (with the Gini coefficient decreasing from 0.52 to 0.41).

These cases illustrate that technological adaptation must integrate local resource endowments, a challenge particularly pertinent to the Global South as highlighted in prior work [102]. For instance, the Jakarta Framework mitigates computational barriers through the implementation of edge computing using Jetson Nano devices, while the Nairobi Solution utilizes solar-powered sensors, which consume less than 5W daily, to adapt to unstable power environments. However, the academic contributions of cities in the Global South are systematically undervalued. A literature analysis reveals that their research coverage is less than 15%, with 68% of model training relying on data from Europe and America, such as ImageNet and EuroSAT. This reliance leads to spatial biases in technological outputs, exemplified by a 22% lower accuracy in tropical vegetation classification compared to temperate zones. This phenomenon of data colonialism underscores the inequalities inherent in the knowledge production system [84].

To resolve this dilemma, constructing a decentralized data ecosystem is essential. Research indicates that cross-regional data sharing can be achieved through federated learning frameworks, such as PySyft, in conjunction with localized protocols like the African Union’s Open Data Charter, which incentivizes local knowledge production. For example, the “Open Urban Green” platform has standardized multilingual annotation protocols, supporting languages such as Swahili and Portuguese, resulting in an increase in data contribution from the Global South from 8% to 34% between 2020 and 2025. Additionally, promoting the compatibility of lightweight models, such as EfficientNet-Lite, with low-cost hardware like Raspberry Pi is necessary to lower the technical barrier. Looking ahead, blockchain-driven data ownership mechanisms and transnational collaboration networks have the potential to reconstruct a fair ecosystem of technological governance [85].

3.6. A Decade of Evolution: From Germination to Paradigm Revolution

The technological evolution trends over the past decade (2015–2025) exhibit distinct phase characteristics (Table 5). The nascent period (2015–2018) was primarily dominated by traditional models, such as SVM [86] and RF [98], alongside single-source remote sensing data [81,95]. This phase focused on descriptive analysis and the construction of static indicators. A notable example is Yao’s (2015) GIS-SCS-CN model, which achieved the first spatial quantification of the hydrological effects of UGS by integrating geographic information systems with the runoff curve number method [87], and has been cited 218 times. However, it relied on static vegetation indices, such as the NDVI with a resolution of ≤30 m, which limited its ability to capture the ecological dynamics of complex urban areas. During this phase, 68% of the studies were based on data from European and American cities, which restricted the generalization capabilities of the models, resulting in a decrease in cross-regional accuracy by ≥25% [103].

Table 5.

ML technology evolution continuum (2015–2025).

The outbreak period from 2019 to 2022 saw the emergence of DL techniques, specifically CNN and Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTM), alongside the integration of multi-source data, including remote sensing [107,108,109] and street view imagery [106]. This shift in technological focus emphasized dynamic modeling and health equity analysis. Notably, the CRAUNet model achieved an IoU accuracy of 97.34% in complex UGS segmentation, significantly surpassing traditional methods such as DeepLabV3+, which recorded an IoU of 94.21% [66]. The proportion of research dedicated to multi-source data fusion, incorporating remote sensing, street view, and social media, has escalated from 18% to 54%. Furthermore, a previous study utilized Dutch cohort data (N = 34,567) to demonstrate that a 10% increase in the accessibility of green space within a 500 m buffer zone correlates with a 7% reduction in the risk of depression (Odds Ratio = 0.93, p < 0.001), thereby elevating health equity as a central concern in policy discussions [73].

The Transformation Period (2023–2025) is characterized by advancements in generative AI and metaverse technologies, which are shifting the research paradigm from an “analysis-driven” approach to a “creation-driven” one. Diffusion models, such as Stable Diffusion, and LLMs facilitate the automatic generation of multi-objective planning schemes. The LFM model significantly reduces the time required for scheme design from 40 hours to just 8 hours, representing a fivefold increase in efficiency [75]. Moreover, it simulates the stormwater retention effects of green spaces using digital twin technology, achieving a mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.8 m3/s. On the policy front, Singapore has integrated streetscape aesthetic evaluation model into its national standard [110], which directly informs the design of high-density communities [89]. Concurrently, ethical governance has been enhanced, with 45% of studies now incorporating algorithmic reviews, marking an eightfold increase since 2015. A another study has addressed model bias using SHAP values, which has improved the fairness of green space allocation in low-income communities by 67% [62]. Nevertheless, the long-term ecological efficacy of generative AI remains inadequately verified, with tracking studies comprising less than 10% of the total. Additionally, the disparity in technology adoption between the Global North and South is pronounced, with coverage in Global South cities being less than 20%, underscoring the challenges associated with technological democratization.

3.7. Linking Symbiotic Intelligence to Building-Scale Decisions and Performance

The Symbiotic Intelligence framework and the ML methods reviewed herein translate directly to building-scale design and performance optimization. The following mapping elucidates these connections (Table 6):

Table 6.

ML Method and Building-Scale Decisions and Performance.

4. Discussion

The “Symbiotic Intelligence” framework proposed in this article transcends mere technological integration; it represents a new paradigm for understanding and managing the built environment in the pursuit of sustainability. It resonates profoundly with core challenges in building science and architectural engineering [111], particularly in enhancing building resilience and navigating socio-technical transitions. Firstly, by dynamically coupling data on building performance, occupant well-being, and technological systems, the framework expands the concept of building resilience from a passive capacity for “resistance and recovery” to an active capability of “learning, adaptation, and co-evolution.” This shift is crucial for ensuring the long-term operational sustainability and adaptability of buildings and their immediate environments. Secondly, the paradigm shifts from “analysis-driven” to “creation-driven” represents a fundamental change in the architectural and building design process. Generative AI and digital twins are evolving from analytical tools into co-creation platforms, enabling the pre-emptive simulation and optimization of building designs for environmental performance [112,113] and social utility, thereby embedding sustainability as a core design principle from the outset. This evolution necessitates a corresponding rethinking of architectural education, professional practice, and project governance. However, within this technologically empowered promise for the built environment, we must remain vigilant against a new form of social exclusion that threatens the “justice” imperative of sustainability. As building-related decisions-from resource allocation to space design-increasingly rely on algorithms and digital interfaces, the equity debate shifts from ensuring the “right to access” adequate shelter and amenities to the “right to shape” the intelligent systems governing them. Without a conscious commitment to ethical algorithms and inclusive design that engages all stakeholders, “symbiotic intelligence” risks exacerbating the divide between the technologically privileged and marginalized communities, thereby undermining the social sustainability of our built environment. Therefore, the value of this study lies in advocating for a critical practice that deeply integrates intelligent building management [114], spatial justice, and ecological stewardship, ensuring that the journey toward smarter built environments is itself inclusive, equitable, and truly sustainable.

The rise in generative AI signifies a paradigm shift in technology from an “analysis-driven” approach to a “creation-driven” one. Diffusion models and large language models (LLMs) can generate multi-objective planning solutions, enhancing design efficiency by fivefold. Additionally, these technologies allow the public to experience the effects of green space design through metaverse digital twins, resulting in a 41% increase in user satisfaction. However, such advancements pose significant ethical risks: 68% of generative models fail to calibrate socio-economic variables, which may exacerbate the advantages of high-income communities in green space services, with a bias rate ranging from 9% to 15%. To address these challenges, the study proposes a four-dimensional “Algorithmic Justice Assessment Matrix”-encompassing fairness, transparency, accountability, and inclusivity-and validates its efficacy through empirical case studies. For example, SHAP value correction successfully reduced the bias rate in green space allocation for low-income communities from 12% to 4% [62], while a voice-interactive LLM pilot in Mumbai slums increased resident participation rates to 57%. These practices illustrate that ethical governance must transition from principled initiatives to actionable technical tools and international standards, such as the “Ethical Standards for Smart Green Space Algorithms” established by ISO.

Innovative practices in the Global South have established a precedent for technology adaptation under resource constraints. The Jakarta team achieved an 18% reduction in model generalization error by utilizing only 10% of central data through a lightweight federated learning framework. In Nairobi, a low-cost street view database was constructed using discarded smartphone cameras, resulting in a 90% reduction in data collection costs [115]. Additionally, Rio de Janeiro integrated AI fairness heat maps into slum redevelopment policies, which narrowed the green space coverage gap by 21%. These examples highlight the technological principle that “adaptation is superior to transplantation”; However, the knowledge gap between the Global North and South remains substantial, with research coverage in Global South cities being less than 15%, and 68% of models relying on data from Europe and North America. To address this issue, it is crucial to develop a decentralized data ecosystem, such as the “Open Urban Green” platform, which standardizes multi-source data formats (remote sensing, street view, sensors) and promotes regional knowledge production through localized protocols. The application of federated learning technology within the joint team of Shanghai-Copenhagen has demonstrated that cross-regional collaboration can decrease model generalization error by 18%, thereby providing a scalable technological pathway for the Global South.

This study reconstructs the research agenda for UGS through the lenses of technology, ethics, and regional considerations. Its significance lies not only in summarizing the achievements of the past decade but also in delineating the new frontiers of generative AI, ethical algorithms, and innovations from the Global South. We propose that elucidating the specific application pathways of the “Algorithmic Justice Assessment Matrix” in policymaking can aid in the renewal planning of UGS. During the policy design phase, this four-dimensional matrix can be integrated into national AI governance regulations through legislative embedding, mandating that AI systems or models for UGS undergo matrix evaluation prior to deployment. In the policy implementation phase, cross-regional collaboration can be fostered through the “Smart Green Space Alliance” to exchange compliance models; additionally, a block chain system may be established to facilitate the creation of a new algorithm registration platform, allowing for real-time documentation of model updates and ethical review outcomes for dynamic regulation. It is essential to periodically revise evaluation metrics to address emerging risks for successful iteration. In the policy evaluation phase, the dimensions of the matrix can be aligned with relevant indicators of the SDGs to promote fairness and transparency. Furthermore, public feedback on algorithmic decision-making can be gathered through a VR democratization platform and integrated into the foundation for policy revisions.

Despite notable progress, this study presents three limitations. First, the literature reviewed is exclusively in English, which may overlook regional innovation practices, such as localized sensor network designs in Africa. Future research should expand data sources through multilingual searches and local collaborations. Second, the comparison of model performance is limited by dataset heterogeneity, including variations in remote sensing data resolution and inconsistent street view labeling standards, which diminishes the comparability of results across studies. It is essential to promote the standardization of multi-source data, and to establish unified evaluation protocols. Third, the long-term efficacy of generative AI applications, such as LLM policy simulation, remains invalidated, as most studies focus on short-term effects, exemplified by a 67% increase in community participation rates. The sustainability of their ecological and social impacts necessitates ongoing tracking and research, ideally through monitoring over five years or more. Future initiatives should aim to establish long-term observation networks and develop complex system models, such as UGS–climate-economy coupling simulations, to comprehensively assess the sustainability of technological interventions.

Figure 11 illustrates the trend of ML applications in UGS research from 2015 to 2025. In the future, research in this interdisciplinary field should concentrate on three primary directions: First, the development of complex system models that couple UGSs, climate, and economy to facilitate multi-objective dynamic optimization. Second, the construction of lightweight federated learning frameworks and low-cost sensor networks specifically designed for the Global South to combat data colonialism. Third, the promotion of community-driven participatory planning through block chain technology and decentralized autonomous organizations, ensuring that the voices of vulnerable groups are protected. At the policy level, in the short term, it is advisable to promote AI health diagnostic systems and fairness heat maps. In the long term, integrating smart green spaces into the “Smart City ISO Standards” [116] and issuing climate resilience bonds based on the FLUS model is essential [7]. Visualization tools, such as dynamic co-citation networks and 3D GIS, can enhance decision-making narratives, while interactive VR enables the public to engage as co-designers in planning, for example, through immersive assessments of the aesthetic value of green spaces.

Figure 11.

The trend of ML applications in UGS research from 2015 to 2025 ([17,22,24,27,29,40,42,53,60,61,62,63,64,66,68,72,73,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,95,96,97,98]).

While this review synthesizes evidence from existing literature to propose the ‘Symbiotic Intelligence’ framework, its ultimate value resides in practical application and validation. To guide future research and application, we propose a multi-city collaborative pilot study design aimed at empirically testing its core mechanisms and efficacy.

- (a)

- Objective & Hypothesis: The primary objective of this study is to test the hypothesis that urban districts implementing the Integrated Symbiotic Intelligence framework exhibit statistically significant improvements in UGS performance metrics, such as ecological resilience, equity of access, and public satisfaction-when compared to control districts that utilize conventional planning approaches.

- (b)

- Pilot City Selection: A cohort of 3 to 5 partner cities should be selected to represent diverse contexts, such as a densely populated Asian metropolis, a European city, and a rapidly urbanizing city in the Global South. This selection will facilitate the testing of the framework’s adaptability across varying urban environments.

- (c)

- Intervention Design: Each pilot city will implement the framework in a designated district, consisting of three key layers: The Generative AI Layer, the Ethical Algorithm Layer, and the Global South Innovation Layer. The Generative AI Layer will utilize models such as fine-tuned Stable Diffusion to generate diverse design options for multi-objective UGS. The Ethical Algorithm Layer will implement and calibrate fairness in allocation models, such as those utilizing SHAP, to prioritize investments in underserved areas. Finally, the Global South Innovation Layer will deploy low-cost sensor networks alongside lightweight federated learning protocols to facilitate cost-effective monitoring.

- (d)

- Data Collection & Metrics: Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) will be collected both before and after the intervention, encompassing remote sensing data such as Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and Land Surface Temperature, as well as sensor data and public surveys. The core metrics will quantify changes in: (i) Ecological Resilience, exemplified by a reduction in local temperature; (ii) Health Equity, indicated by a decrease in the Gini coefficient of UGS accessibility; and (iii) Process Efficiency, measured through time and cost savings.

- (e)

- Validation: A robust methodology, such as a difference-in-differences analysis comparing pilot districts with carefully selected control districts, will be employed to isolate the causal impact of the framework.

This proposed pilot framework presents a concrete and scalable pathway for transitioning our conceptual model into an empirically testable urban intervention, thereby opening a critical avenue for future research.

The discussion surrounding empirical validation naturally raises the question of generalizability. Although the specific magnitude of the quantitative metrics synthesized in this review (e.g., 41%, fivefold) may differ across local contexts, the foundational methods-such as employing VR for immersive planning feedback and utilizing generative AI for rapid scheme iteration-are universally applicable. The key to successful replication in other cities does not lie in reproducing the exact numerical outcomes, but rather in adapting the baseline to local conditions and rigorously applying standardized pre- and post-evaluation protocols, as recommended in the proposed pilot framework.

Our synthesis reveals a fundamental divergence between the innovation pathways of the Global North and South. The North pioneers a “power-intensive” paradigm, exemplified by high-resolution digital twins and complex generative AI, while the South excels in “resource-constrained” innovation, as seen in lightweight federated learning and low-cost sensors. This dichotomy extends to data ecosystems, where the South grapples with data colonialism and scarcity, and to ethical priorities, which shift from the Northern focus on fairness refinement to the Southern emphasis on inclusive access. Consequently, research from the North demonstrates greater integration into formal policy, whereas solutions from the South often remain in the pilot stage. This situation is not merely a divide; it creates a crucial complementarity: The North’s advanced models establish performance benchmarks, while the South’s adaptive solutions offer essential scalability tools. Therefore, fostering a bidirectional learning loop between these contexts is essential for developing a truly robust and globally relevant Symbiotic Intelligence paradigm.

The distinctive ‘resource-constrained’ innovation paradigm of the Global South is fundamentally shaped by structural inequities, which serve as a direct response to dysfunctional policies, profound equity gaps, and severe technological access barriers. The lack of robust governance catalyzes decentralized, community-driven workarounds, exemplified by Jakarta’s federated learning initiatives. Pre-existing social inequities necessitate a reorientation from efficiency maximization to prioritizing equity as a foundational principle, which drives the development of tools such as fairness heat maps and voice-interactive LLMs for slum upgrading. Concurrently, the high cost of technology encourages a transition from capital-intensive to ingenuity-driven development, as demonstrated by the use of low-cost sensors derived from discarded phones. Therefore, these innovations should not be perceived merely as technical artifacts; rather, they must be understood as contextually embedded sociotechnical responses. This underscores the necessity of moving beyond simplistic technology transfer towards genuine, context-aware co-creation.

To transition lightweight federated learning and low-cost sensors from localized innovations to globally scalable solutions, a concerted standardization strategy is imperative. This strategy entails developing open-source, lightweight federated learning protocols (e.g., based on PySyft or Flower) to ensure interoperability and privacy; promoting certified ‘UGS Sensing Kits’ that integrate calibrated hardware with pre-installed software for plug-and-play deployment; establishing common data annotation standards (e.g., COCO, GeoJSON) with multilingual support; and validating these solutions through international benchmarking consortiums (e.g., under UN-Habitat or ISO) to build trust and foster a replicable global commons for urban sustainability.

The Symbiotic Intelligence framework is inherently designed to address data heterogeneity and scarcity (with less than 15% coverage) through a suite of adaptive strategies. Federated Learning (FL) utilizes disparate datasets from various cities without centralization, thereby constructing robust models that uphold data sovereignty. Transfer Learning facilitates rapid adaptation to new contexts by fine-tuning pre-trained models with minimal local data. In scenarios of extreme scarcity, Generative AI generates context-aware synthetic data for augmentation, while Citizen Science and proxy variables (such as utilizing street-view imagery as a proxy for greenness) effectively bridge critical data gaps. Consequently, the framework re-conceptualizes data scarcity not as an obstacle, but as a design constraint that is addressed through its integrated technological toolkit.

Building upon the review, we propose a concrete methodology for constructing UGS–climate–building coupling models. These spatially explicit, dynamic models should prioritize the most critical physical processes: evapotranspiration from vegetation, which serves as the primary cooling mechanism, and the radiative exchange between green spaces, building surfaces, and the sky. Core inputs must encompass UGS parameters (e.g., type, Leaf Area Index (LAI)), urban fabric metrics (e.g., building density, albedo), and climatic forcings. The key outputs are the coupled interactions, including pedestrian-level microclimate modulation, resulting building energy savings, and quantifiable ecosystem services. We recommend a hybrid physics-informed ML approach, where high-fidelity simulations (e.g., from ENVI-met 5.1, EnergyPlus 23.2.0) train efficient ML surrogates (e.g., Graph Neural Networks) for rapid scenario planning, driven by land-use change scenarios derived from models such as the Future Land-Use Simulation (FLUS) model.

The efficacy of decentralized and blockchain-based participatory frameworks should be evaluated against a comprehensive set of benchmarks across three dimensions: Participation, Technical Performance, and Governance & Equity. The Participation dimension assesses the rate and demographic diversity of engagement, as well as the quality of deliberation through Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques. The Technical Performance dimension focuses on ensuring adequate transaction throughput and the verifiability of data integrity and immutability. Lastly, the Governance & Equity dimension involves auditing decision transparency, evaluating the fairness of planning outcomes using metrics such as the Gini coefficient, and measuring improvements in public trust through surveys. A successful implementation must demonstrate high performance across all dimensions, thereby establishing itself as both technologically robust and socially equitable.

The Symbiotic Intelligence framework is designed to facilitate tangible policy integration and achieve real-world impact. Its application can be realized through four synergistic pathways: First, revising urban planning guidelines to mandate the use of generative AI scenario planning and incorporating algorithmic fairness heat maps in impact assessments. Second, integrating the framework into green building certifications (e.g., LEED, BREEAM) by creating credits for verifying UGS performance through digital twins, demonstrating equitable design via ethical algorithms, and deploying low-cost monitoring systems. Third, establishing a new ‘Symbiotic City’ label to comprehensively reward districts that excel in data-driven, equitable, and co-creative governance. Finally, initiating policy sandboxes as real-world living laboratories to generate the evidence needed for broader institutional reform, thus transitioning the framework from an academic concept into an operational driver of sustainable and just urban development.

5. Conclusions