Abstract

As a widely used structural material in construction, the energy dissipation characteristics of concrete under dynamic impact are crucial for evaluating a structure’s impact resistance and safety performance. However, conventional methods for evaluating energy dissipation characteristics fail to adequately account for the multi-parameter coupling effects during dynamic impact processes. Herein, the dynamic behavior of C15, C20, C30, and C40 concrete specimens was investigated using a split Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) apparatus. The dynamic response and energy dissipation mechanisms under impact loading were analyzed. The correlation between energy dissipation density and multiple parameters—including initial loading conditions, peak strain, dynamic compressive strength, and strain rate—was examined. Based on this analysis, a performance index Pi, grounded in energy dissipation density, was proposed for evaluating dynamic energy dissipation. The results show that under dynamic impact loading, concrete specimens of different grades basically show brittle damage mode and obvious strain-rate strengthening effect. Specifically, the dynamic compressive strength of C15-3 is 22.10 MPa, representing an increase of approximately 47.3%, while that of C40-3 is 46 MPa, showing an increase of approximately 15%. The energy transfer in concrete specimens is influenced by initial loading conditions, concrete material properties, and damage modes, among other factors. All of these parameters exhibit a strong correlation with the energy dissipation density. The comprehensive multi-parameter performance index Pi for dynamic energy dissipation yields superior evaluation results compared to using energy dissipation density alone. The research results provide an innovative reference for structural safety protection.

1. Introduction

As a common material for structural safety protection, concrete is widely used in various types of buildings, such as high-rise buildings, transport routes, and other infrastructures [1,2,3]. The safety protection capabilities of concrete materials during dynamic impact processes are particularly crucial when building structures are subjected to impact or explosive loads, such as earthquakes, explosions, vehicle collisions, terrorist attacks, and the demolition of buildings or structures [4,5,6,7]. However, the energy dissipation characteristics exhibited by concrete materials under dynamic impact serve as a critical indicator for assessing their impact resistance [8,9]. Therefore, to optimize structural safety design and evaluate protective capacity, a comprehensive multi-parameter investigation into the energy dissipation characteristics of concrete under dynamic impact is essential.

The Separate Hopkinson Pressure Bar (SHPB) system can cover the main strain rate ranges of mechanical behaviors such as bursting and impact. Many scholars have applied SHPB technology to impact testing of concrete materials, conducting extensive experimental and simulation studies. Huang et al. [10] carried out dynamic compression tests of concrete using SHPB, corrected the HJC concrete model, and eliminated the unfavorable inertia effect. Liang et al. [11] used the SHPB testing technique to numerically investigate the dynamic increase factor of ultra-high performance concrete under compressive impact and established an analytical model for SHPB testing by calibrating the KC model. Ren et al. [12] explored the dynamic mechanical properties of cellulose fiber-reinforced concrete under moderate to high strain rates with different fiber contents. Using the Box–Behnken design method, they established the relationship between dynamic constitutive model parameters, fiber dosage, and strain rate. Jiang et al. [13] investigated the dynamic compressive properties of rubberized self-compacting concrete using split Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) tests. The tests were also used to validate a strain rate effect model specifically developed for this type of concrete. Cao et al. [14] conducted uniaxial dynamic compression tests on composite steel fiber-reinforced concrete with varying fiber contents using an SHPB setup. The relationship between the dynamic response of the composite concrete and fiber content was investigated, and an empirical formula for its strain-rate strengthening effect was established. Wang et al. [15] prepared specimens of graphene oxide-modified concrete and subjected them to impact testing using an SHPB apparatus. The influence of graphene oxide on the impact mechanical properties of concrete was thereby examined. Zhuang et al. [16] performed dynamic compression tests using an SHPB setup to investigate the influence of coarse aggregate size on ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC). An enhancement mechanism through which aggregate size affects the impact resistance of UHPC was proposed based on the findings. Chen et al. [17] developed an improved SHPB setup to investigate the coupled effects of temperature and strain rate on the dynamic mechanical behavior of foam concrete. A reliable constitutive model for its stress–strain response was subsequently established. Currently, most dynamic impact tests on concrete materials focus on the influence of different admixtures on the dynamic response. In contrast, relatively limited attention has been paid to the energy dissipation characteristics of concrete during dynamic impact processes. Clarifying the energy dissipation mechanism of concrete under dynamic impact is essential, as it provides a valuable reference for material design and establishes a theoretical basis for engineering safety protection.

Research on concrete materials indicates that energy dissipation during dynamic impact is influenced by multiple factors. Xie et al. [18] examined the energy dissipation rate of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete under impact loading at different strain rates, along with the effect of basalt fiber volume content on the dynamic response. Bakhshi M et al. [19] investigated the dynamic response and energy dissipation characteristics of lightweight perlite concrete under static uniaxial compression testing. The influence of different mixture components on the physical–mechanical properties of the material was explored, and a new model was subsequently proposed to describe the compressive behavior of perlite concrete and its energy dissipation capacity. Aown M et al. [20] investigated the energy absorption behavior of geopolymer rubberized concrete using hemispherical impactors under both quasi-static and drop-weight impact conditions. Separately, Mei X et al. [21] developed a novel seismic-resistant concrete material combining rubber and cement, and employed machine learning models to predict the energy absorption characteristics of the rubberized concrete. Zhou et al. [22] investigated the damage behavior and energy dissipation characteristics of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete with five different fiber contents at four strain rates using a split Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) test apparatus. Based on the test data, the damage evolution process of the concrete was further reproduced through LS-DYNA simulations. Geng et al. [23] analyzed the energy variation characteristics during the failure of specimens under impact loading, considering the dynamic evolution of concrete before and after peak stress. An evaluation method for the brittleness index of concrete was also established, which is based on the complete stress–strain curve. Li et al. [24] prepared four types of steel-like fiber-reinforced concrete specimens and performed uniaxial compression tests. The compression energy absorption, crack evolution, and fracture surface fractal characteristics of the fiber concrete were investigated. Feng et al. [25] employed SHPB experiments and numerical simulations to study the impact damage behavior of foam concrete with different densities. The fractal dimension and energy absorption characteristics of foam concrete were determined and correlated. Khan M M et al. [26] investigated the dynamic compressive behavior of both normal and high-strength concrete at various strain rates. The effects of specimen geometry and concrete strength on the peak energy dissipation density and total energy density were examined. In addition, numerous studies have investigated the energy dissipation of other specialized concrete materials under impact loading [27,28,29,30,31]. In current research on energy dissipation of concrete materials under impact loading, qualitative analysis of energy variation predominates. Quantitative evaluation using specific indicators to assess the energy dissipation of specimens under dynamic impact remains relatively limited. Consequently, the analysis and assessment of energy dissipation transformation are subject to certain limitations. Furthermore, existing studies have largely overlooked the mechanisms through which multiple parameters jointly influence the energy dissipation of concrete materials during dynamic impact.

Energy dissipation characteristics of concrete specimens across different strength grades are evaluated, with due consideration of the coupled influence of key parameters during dynamic impact. This study proceeds in three steps. First, split Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) testing is employed on concrete specimens of common strength grades (C15, C20, C30, and C40) to characterize their dynamic response and energy dissipation under varying strain rates, from which key parameters governing energy dissipation are identified. Specifically, the study examined the correlation between multiple parameters—including initial loading conditions, peak strain, dynamic compressive strength, and strain rate—and energy dissipation density during dynamic impact processes. Second, energy dissipation density is used to provide a preliminary assessment of the correlation between these parameters and energy dissipation. Finally, a performance index (Pi) is proposed to evaluate the dynamic energy dissipation capacity of concrete by integrating the key parameters identified earlier. Its feasibility and practical utility are demonstrated through comparison with energy dissipation density across all tested specimens. These findings can inform predictions of concrete response under dynamic impact and contribute to the development of performance-based protective strategies for concrete structures.

2. SHPB Experiment

2.1. SHPB Testing Equipment and Principles

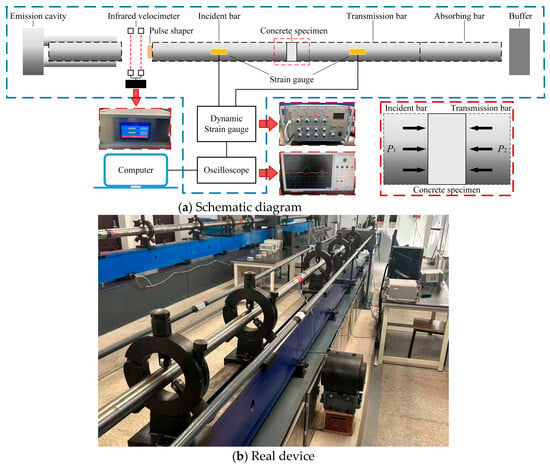

The experiment was conducted basing on the Φ50 mm SHPB (Split Hopkinson Pressure Bar) test system at the State Key Laboratory of Precision Blasting, Jianghan University. The SHPB system consists of the bullets, incident rod, transmission rod, and absorption rod which are all high-strength cylindrical steel rods. The diameter of the device used in this test is 50 mm, the length of the bullet is 0.8 m, the length of the incidence rod is 5 m, and the transmission rod is 4.5 m. The elastic modulus of the rod is 210 GPa, and the density is 7850 kg/m3. During the experiment, the strain rate of the specimen was controlled by adjusting the gas pressure in the launch chamber to vary the bullet’s exist velocity. The brass sheet was employed as a pulse shaper to prolong the rising edge of the incident wave and eliminate the high-frequency oscillation caused by high-speed impact. Simultaneously, strain gauges were attached to the surfaces of both the incident and transmitted rods, with an equal distance maintained between each gauge and the specimen. The strain gauges had a resistance of 120 Ω. The pulse signals from the incident rod, specimen, and transmitted bar were recorded by these strain gauges, converted into electrical signals via a dynamic strain indicator and an oscilloscope, and subsequently output. The residual energy after impact was absorbed by the absorber rod and damper within the buffering device. Finally, the experimental data were processed using the classical three-wave method to calculate the stress (σ), strain (ε), and strain rate () at both ends of the specimen.

In the SHPB experiment, the bullet impacts the incident bar rod as a preset velocity to generate a compressive stress wave. When the incident rod strain gauge receives this stress wave signal for the first time, the oscilloscope displays it as the incident wave signal. The stress wave then propagates forward to the specimen assembly. A portion of the wave is reflected back to the incident rod and is received a second time by the strain gauge on the incident rod. At this time, the oscilloscope displays the received reflected stress wave signal. The remaining portion of the stress wave transmits through the specimen and is transmitted to the strain gauge on the transmission rod, receiving the transmitted stress wave signal. The experimental setup is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of split Hopkinson pressure bar test setup.

2.2. Concrete Test Block Design

The specimens were prepared using standard concrete with four strength grades: C15, C20, C30, and C40. The concrete mixtures consisted of cement paste, standard sand, and aggregates. The cement employed is bagged ordinary Portland cement. Sand 1 is medium-grade river sand with a fineness modulus of 2.7, while Sand 2 is medium-grade sand with a fineness modulus of 2.9. The crushed stone used is flint-like in shape, with a particle size distribution conforming to a continuous grading range of 5 mm–20 mm. Potable tap water was employed as mixing water, and a Polycarboxylate high-performance water reducer was also added to enhance the workability of the concrete. Five specimens shall be prepared for each strength, totaling fifteen specimens. The mix proportions for C15 concrete are: cement:sand 1:sand 2:crushed stone:water:superplasticiser = 1:5.97:5.50:1.22:0.035. The mix proportions for C20 concrete are: cement:sand 1:sand 2:crushed stone:water:superplasticiser = 1:3.53:4.45:0.98:0.034. The mix ratio for C30 concrete is: cement:sand 1:crushed stone:water:admixture = 1:3.06:3.41:0.69:0.03.

The mix ratio for C40 concrete is: cement:sand 1:crushed stone:water:water-reducing agent = 1:2.16:2.82:0.51:0.032. All specimens were cylindrical, with a diameter of 50 mm and a length of 25 mm. After casting and vibratory compaction, the specimens were demolded one day later, the cured specimens are placed in a standard curing room with a temperature of (20 ± 2) ℃ and a humidity of not less than 95% for 28 days to ensure. After curing, concrete specimens were wrapped in cling film and the SHPB test completed within 24 h. All concrete grades underwent static compression testing on standard cubes cast simultaneously following curing completion. The average measured strengths for the respective grades were as follows: C15 at 20.4 MPa, C20 at 27.2 MPa, C30 at 37.6 MPa, and C40 at 48 MPa. To guarantee that the ends of the cylindrical specimen are smooth and flat, after curing, the specimens were sent to the factory for cutting and grinding, with the end-face parallelism controlled within 0.02 mm.

3. Analysis of Experimental Results

3.1. Stress Equilibrium Verification

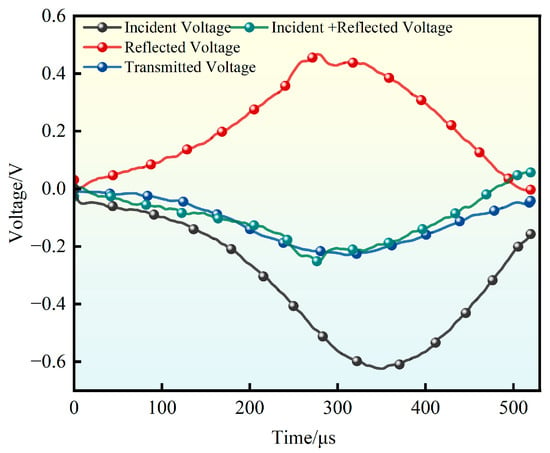

During SHPB testing, stress uniformity across both ends of the concrete specimen must be ensured. Figure 2 shows the stress equilibrium verification curve for the concrete specimen, where the three-wave method was applied to examine the voltage amplitude signals for stress balance. As shown in Figure 2, the sum of the incident and reflected signal voltages aligns closely with the transmitted signal voltage in the test, indicating that the stress state in the specimen essentially satisfies the assumption of stress equilibrium. This alignment confirms that specimen preparation and testing meet the requirements for the one-dimensional stress wave assumption, as well as for minimizing end friction and inertial effects in SHPB experiments. Consequently, the concrete specimen demonstrates satisfactory stress uniformity during SHPB testing.

Figure 2.

Verification of specimen stress balance.

3.2. Dynamics Response Analysis of Specimen Under Impact Loading

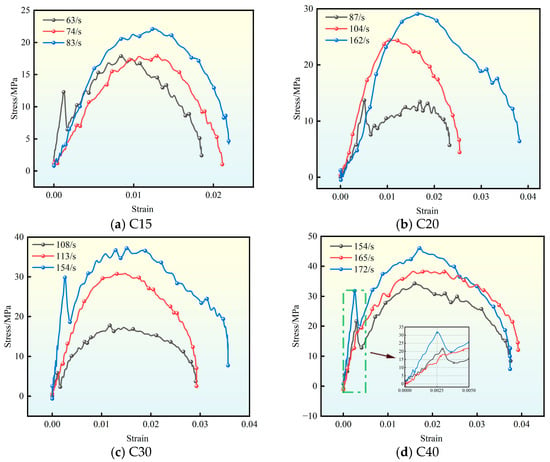

Table 1 shows the dynamic mechanical parameters of concrete specimen under different strain rates, Figure 3 shows the fracture conditions of different grade concrete under different strain rates, and Figure 4 shows the stress–strain curves of different grade concrete under different loading rates.

Table 1.

Concrete test data under different strain rates.

Figure 3.

Concrete damage situations at different strain rates.

Figure 4.

Dynamic compressive stress–strain curves.

It can be seen from Figure 3 that under the same grade concrete, with the increase in loading strain rate, the degree of concrete fragmentation increases, the overall failure mode develops from “local cracking” to “structural yielding” and finally to “complete fragmentation”, and the fragmentation disperses from the center of the test block to the periphery. Under dynamic impact, the impact load action time of the concrete specimen is short, and the test block quickly reaches the strength limit after the elastoplastic stage. The failure process of different grades of concrete exhibits obvious brittleness.

Figure 4 shows that for the same grade of concrete, the peak strain and dynamic compressive strength increase with the increase in strain rate, and the dynamic compressive strength at a given strain rate is significantly higher than the quasi-static compressive strength of the concrete grade, which proves that the concrete specimen has a strain rate enhancement effect under dynamic impact. The dynamic curve of high-grade concrete under dynamic impact load can clearly reflect the stage from elasticity to fracture, while the low-grade concrete has low strength, high porosity, initial defects in the interior, weak interface between aggregate and paste, and is easy to produce local deformation or micro-cracks under low stress, which leads to the elastic stage is not obvious, indicating that the microscopic damage evolution mechanism of different grade concrete under dynamic impact load is different.

As shown in Figure 4d, taking C40 concrete specimen with clear curve as an example for concrete analysis, the elastic stage is about strain 0–0.003, the stress increases linearly with strain, and the incident energy is converted into elastic energy and stored in the specimen; At strain 0.003–0.02, the elastic–plastic stage, the slope of the curve decreases continuously until it reaches the peak stress. At this stage, the crack begins to develop at the weakest point of the material, and the damage accumulates continuously with the increase in strain. After strain 0.02, the stress decreases with strain increasing, and scattered cracks begin to propagate, connect, and penetrate, forming macroscopic fracture surface, and dynamic compressive strength loses in this stage, structural integrity loses, and gradually cracks begin to fracture.

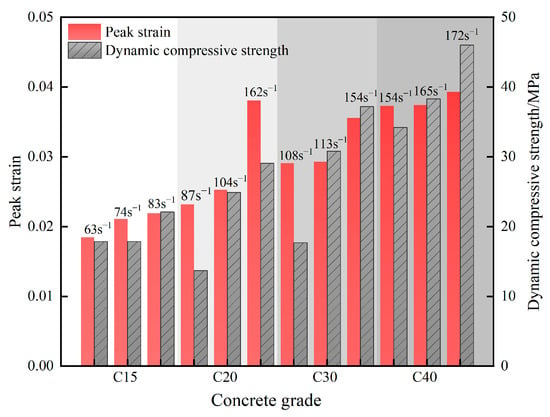

Figure 5 illustrates the variation trends of peak strain and dynamic compressive strength across concrete strength grades. During dynamic impact, both parameters generally increase with concrete grade. As shown in Figure 3, for specimens of the same grade, peak strain rises with the severity of fragmentation. Specifically, the peak strain of C40-3 should not exceed 0.0393, indicating the most severe degree of fracture. Overall, peak strain exhibits a progressive increase with both concrete strength grade and applied strain rate, whereas dynamic compressive strength is more strongly governed by loading conditions. Among all grades, C30 specimens display the most pronounced response, accompanied by a progressively intensifying damage pattern. Notably, for a given grade, higher dynamic compressive strength—induced by elevated strain rates—correlates with more severe fragmentation. Moreover, the sensitivity of dynamic compressive strength to strain rate diminishes as the concrete strength grade increases. Specifically, the dynamic compressive strength of C15-3 is 22.10 MPa, representing an increase of approximately 47.3%, while that of C40-3 is 46 MPa, showing an increase of approximately 15%.

Figure 5.

Peak strain vs. dynamic compressive strength.

3.3. Concrete Energy Dissipation

According to the one-dimensional stress wave and stress uniformity theory in elastic bar impact processes, the incident energy generated by the projectile impacting the incident bar is ultimately divided into three parts. One portion is transmitted to the specimen and then reflected back into the incident bar (reflected energy). Another portion passes through the specimen into the transmission bar (transmitted energy). The final portion is absorbed by the specimen for deformation, fracture, and related processes (absorbed energy). Table 2 presents the energy changes calculated for different specimens at various strain rates, further analyzing the energy dissipation law in concrete under impact loads.

Table 2.

Summary of energy parameters of different strengths concrete with strain rates.

The absorbed energy, which is the portion absorbed and dissipated by the specimen during dynamic loading, primarily manifests as damage, cracking, crack propagation, and plastic deformation in the concrete material. This energy is calculated based on the one-dimensional stress wave theory, with the specific formula given as

where WS is absorbed energy, WI is incident energy, WR is reflected energy, and WT is transmitted energy.

Energy dissipation density refers to the energy absorbed or dissipated by a concrete specimen per unit volume, which eliminates the influence of specimen size effect on the basis of dissipated energy. The formula is

where Ud is the energy dissipation density and V is the specimen volume.

As shown in Table 2, the energy of each component in concrete of the same grade generally increases with increasing strain rate, and the energy dissipation density also increases with higher strain rates. The dynamic compressive strength of the specimens increases with increasing strain rate. Under similar strain rates, the energy dissipation behavior of concrete under impact loading is influenced by the concrete grade. Among these, C40-3 exhibits the highest energy consumption density at 0.57 J/cm3, followed by C30-2 at 0.54 J/cm3. While considering the increase in strain rate, calculating the proportion of energy dissipated by different components in concrete of varying grades can partially characterize the energy conversion patterns of the specimens. Calculations show that the average proportions of reflected energy for C15, C20, C30, and C40 concrete specimens are 51%, 62%, 62%, and 68%, respectively. The proportions of transmitted energy are evaluated as 12%, 8%, 8%, and 4%. As concrete strength increases, the reflected energy of specimens under impact loading rises while transmitted energy decreases. Combining this with the failure modes observed in specimens of different strengths, lower-strength specimens exhibit lower initial wave impedance during loading initiation, with lower elastic modulus, and a slower damage process demonstrating some ductility. Consequently, they exhibit lower reflected energy and relatively higher transmitted energy. Concrete specimens of higher grades exhibit higher wave impedance, greater elastic modulus, and higher compressive strength. Their failure mode manifests as highly brittle crushing failure, with rapid and diffuse damage progression. During impact, energy dissipation occurs through extensive cracking and fracture, resulting in higher reflected energy and lower transmitted energy.

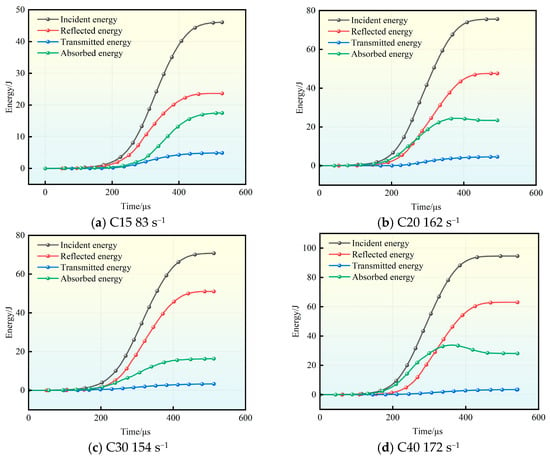

Figure 6 shows the energy time course curves for concrete loaded maximum strain rate specimens. The maximum strain rate experimental data were used to analyze the typical energy changes of concrete specimens. From the figure, it can be seen that the energy of each component grows with the increase in impact time, the initial loading stage, i.e., 0–200 µs, and the energy of each component grows approximately the same. Basically, it starts to grow with the growth of incident energy at about 200 µs, in which the reflective energy grows the most rapidly, and the energy growth of each component tends to be levelled off gradually at about 400–550 µs, and at this time, the value of the reflective energy which is affected by the incident energy is the largest.

Figure 6.

Graph of changes in incident energy, reflected energy, transmitted energy, and absorbed energy.

Take the C40 concrete specimen with a strain rate of 172 s−1 as an example; the overall dynamic compression process is shown in Figure 6c.

0–150 μs: The specimen is in the elastic deformation stage, and the impact energy is stored as elastic strain energy. At this stage, the internal pores in the concrete are compressed to their limiting state.

200–250 μs: The energy of each component begins to increase slowly with the incident energy. Owing to stress wave accumulation, the specimen starts to deform, and numerous internal microcracks are generated.

250–450 μs: The component energies rise rapidly with increasing incident energy. Accumulated internal damage leads to rapid crack propagation and the onset of macroscopic failure. The absorbed energy continues to increase, but stress waves cannot propagate effectively through the fractured medium, resulting in negligible growth of transmitted energy. This stage represents the critical period of energy dissipation, during which the specimen exhibits predominantly brittle failure.

450–550 μs: The stored strain energy is further released as the specimen undergoes extensive fragmentation, and the energy of each component eventually stabilizes.

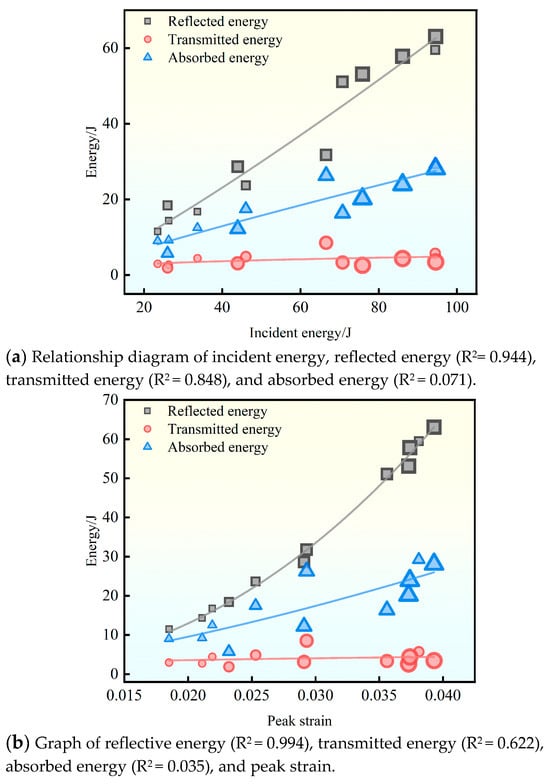

Figure 7a shows the relationships among reflected energy, transmitted energy, absorbed energy, incident energy, and concrete grade. The corresponding curves were fitted to provide a clear representation of these correlations. In the figure, the size of each data point represents the concrete strength grade: the smallest points correspond to C15 specimens, and the largest to C40 specimens.

Figure 7.

Relationship diagram of reflective energy, transmissive energy, absorptive energy, and dynamic loading parameters (the size of the scatter plot markers represents the concrete strength).

As shown in the figure, reflected energy increases with incident energy, but the concrete grade does not exhibit a strictly linear trend. The specimen with the maximum reflected energy is not necessarily the C40 grade. Combined with Table 2, it can be seen that reflected energy is strongly influenced by the strain rate applied to the specimen. At higher incident energies, specimens subjected to higher strain rates exhibit greater reflected energy. The concrete specimens with the highest reflected energy and corresponding strain rates are C20-3 (162 s−1), C30-3 (154 s−1), C40-1 (154 s−1), C40-2 (165 s−1), and C40-3 (172 s−1).

Transmission energy with the increase in incident energy has a certain small increase, and its change is less affected by the incident energy, and the scatter distribution of the data is closer to the distribution of reflection energy, so it is also affected by the loading strain rate, mainly due to the fact that the specimen in the dynamic impact process of the fragmentation will affect the transmission of the stress wave. Absorption energy with the increase in incident energy increased significantly, and the concrete grade and absorption energy has a certain linear relationship, the increase in concrete specimen grade and incident energy—the absorption-energy fitting curve growth trend is consistent, while the absorption energy by the dynamic impact process is of multi-factorial impact, so for the absorption energy curve, despite the performance of the correlation with the concrete grade and incident energy, still has a certain degree of dispersion. Combined with the analysis of Table 2, it shows that the absorption energy with the incident energy growth is not rapid. Combined with the analysis in Table 2, it can be seen that the absorption energy with the incident energy does not grow rapidly, and the proportion of absorption energy does not reach 50% of the incident energy, with an average of 31%, so most of the energy of the incident energy is dissipated in the form of elastic waves of the rod when the concrete specimen is loaded by the impact.

In the impact process, the energy transfer is related to the deformation of the concrete specimen, and in order to reveal the energy dissipation law of the dynamic impact process more comprehensively, the relationship between the peak strain of the specimen and the reflected, transmitted, and absorbed energy is analyzed based on Figure 7b. The relationship between the peak strain and energy of the specimen is shown in Figure 7b, in which the size of the scattering point also indicates the concrete specimen mark. It can be analyzed that with the increase in peak strain, the energy of each component shows different degrees of growth, among which the growth trend of reflected energy and absorbed energy is larger, and the transmittance energy shows a small growth. For the concrete specimen in the dynamic impact process, it indicates that the larger the peak strain, the more serious the damage accumulation, and the reduction in its effective wave impedance will lead to more incident wave energy being reflected, due to the fact that the initial wave impedance of different grades of concrete is not the same, so the reflected energy is linearly correlated with the concrete specimen grades while the peak strain increases. The damage accumulation of the specimen before damage is mainly manifested as crack development, crushing, and deformation, which constitute its main energy consumption mechanism, resulting in the specimen’s increase in consuming energy with the increase in its peak strain. Transmission energy is affected by the damage mode of the concrete specimen, which can be seen in Figure 3; most of the specimen damage modes in this test show crushing damage, and the reduction in stress wave propagation path cannot be effectively converted into transmission energy.

4. Multi-Parameter Assessment of Dynamic Energy Dissipation

4.1. Correlation Analysis of Multiple Parameters Based on Energy Dissipation Density

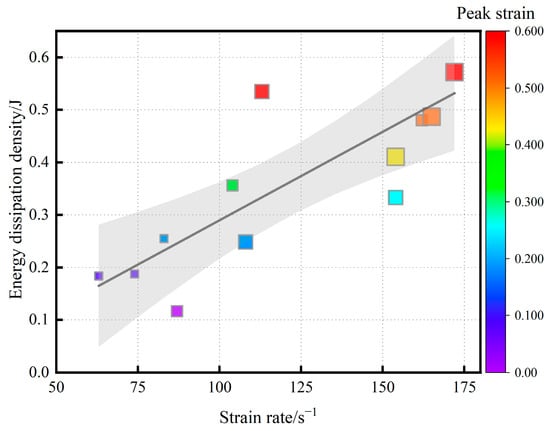

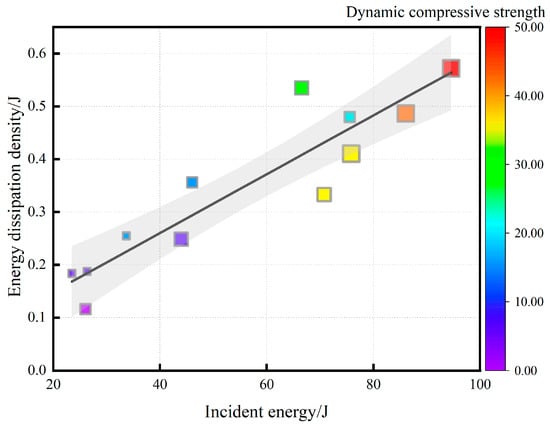

When employing energy dissipation density to evaluate the energy dissipation of test specimens, the specimen demonstrating the most favorable performance was C40-3 at 0.57 J/cm3, followed by C30-2 at 0.54 J/cm3.The peak strain of C30-2 at a strain rate of 113 s−1 was merely 0.0293, indicating a relatively low degree of fragmentation. Energy dissipation density serves as a core indicator for evaluating the impact resistance of materials and is influenced by multiple parameters during dynamic impact. Figure 8 illustrates its relationship with strain rate and peak strain. Figure 9 shows the relationships of energy dissipation density with incident energy and dynamic compressive strength. The size of the scatter symbols in the figure represents the concrete strength grade, with the smallest symbol corresponding to C15 concrete and the largest to C40.

Figure 8.

Relationship between strain rate, peak strain, and energy dissipation density (R2 = 0.626).

Figure 9.

Relationship between incident energy, dynamic compressive strength, and energy dissipation density (R2 = 0.847).

As shown in Figure 8, the color scale on the right side indicates the peak strain of concrete specimens of different grades, and the energy dissipation density increases with strain rate for all concrete specimens of different grades. Strain rate as a measure of the strength of the dynamic impact process of the specimen, with the increase in the impact load, the specimen will show an increase in the energy dissipation mechanism, specifically, concrete specimens in the increasing strain rate loading, and the damage process that is manifested in the development of the development of micro-cracks to the local crushing. The dynamic damage process described above is characterized by the fact that concrete specimens with higher energy dissipation densities have correspondingly higher peak strains, and their damage accumulation process is more extensive and fuller. At similar loading strain rates, the energy dissipation density of higher grades is basically greater than that of lower grades, especially at higher strain rates.

This is due to the elastic modulus, wave impedance, and other physical and mechanical properties of high-grade concrete specimens that are significantly higher than those of low-grade concrete. When subjected to impact loading, C40 concrete specimens will show higher strength, denser matrix, and higher elastic energy can be stored in the initial stage, resulting in more intense damage, including rapid expansion of cracks, intense internal friction, aggregate crushing, and other diffuse energy dissipation. However, the actual energy dissipation of concrete specimens is related to a number of factors, such as the final damage mode of the specimen, incident energy, etc. Therefore, the concrete specimen code does not show a good linear relationship with the energy dissipation density.

Figure 9 shows the relationship between incident energy and energy dissipation density, and the color scale on the right side indicates the dynamic compressive strength of concrete specimens of different grades. For different grades of concrete specimens, the energy dissipation density increases with the increase in incident energy, and at the same time, the energy dissipation density increases with the increase in dynamic compressive strength. Incident energy is the initial energy input for SHPB test loading, and the dissipation of energy by concrete specimens during dynamic impact can be judged by the increase of energy dissipation density. While a larger dynamic compressive strength provides the basis for the reserve of elastic energy in the specimen before damage destruction, it is still constrained by the strain rate. In the same grade of concrete specimens, such as C20 and C40 specimens, the energy dissipation density can show a good linear relationship with the incident energy and dynamic compressive strength.

In summary, the energy dissipation of concrete specimens of different grades subjected to impact loading is related to a number of parameters, such as strain rate, incident energy, peak strain, dynamic compressive strength, etc., and the degree of closeness to each parameter is not the same. The energy dissipation per unit volume can be evaluated using the energy dissipation density which only takes into account the absorbed energy and the size effect, but it is not sufficient to evaluate the whole dynamic impact process of concrete specimens, and it can also be affected by other factors.

4.2. Evaluation of Energy Dissipation Characteristics Based on Dynamic Impact Processes

Building on the above, this study first introduces an energy dissipation coordination factor for dynamic impact processes to account for the influence of the impact process on energy dissipation in concrete specimens. The calculation formula is as follows:

Energy dissipation coordination factor:

where is the peak strain, is the corresponding strain rate, and tm is the time to reach dynamic compressive strength.

This coordination factor (λ), defined as the ratio of peak strain to expected strain, i.e., the ratio of strain rate to the time to reach dynamic compressive strength, quantifies the difference between the actual deformation energy dissipation of the concrete and its expected deformation. It indicates whether energy dissipation is coordinated during dynamic impact, reflecting whether specimen deformation matches the energy input. (A value > 1 suggests that the concrete exhibits good ductility under the impact load, with residual energy dissipation behavior still occurring internally after impact. A value < 1 indicates a more brittle material that undergoes rapid deformation and energy dissipation under high-intensity impact).

Based on the energy dissipation coordination factor that accounts for the dynamic impact process as described above, a multi-parameter evaluation method for the energy dissipation of specimens under identical size conditions is proposed. The calculation formula is as follows:

where Pi is the dynamic energy dissipation performance index for different specimens, Ud is the energy dissipation density, fc,d is the dynamic compressive strength of each specimen, fc is the design strength of each concrete grade, is the energy dissipation coordination factor mentioned above, and α is a fitting coefficient.

In the proposed expression, the first term represents the energy dissipation density (Ud). By eliminating size effects, it provides a macroscopic characterization of the fundamental energy dissipation behavior of concrete under impact loading. The second term is the ratio of dynamic compressive strength (fc,d) to static design strength (fc), which accounts for the strain-rate strengthening effect—the phenomenon whereby concrete exhibits enhanced strength under dynamic impact. Since the intrinsic strength of concrete varies with strength grade and directly influences energy dissipation, this normalization removes disparities arising from differences in inherent material strength, thereby enabling a fair basis for comparison across grades. A system-calibrated value of is obtained by fitting fc,d against fc. The third term introduces the function , derived from Equation (3), to describe the dynamic energy dissipation of concrete specimens during impact. The logarithmic form is employed to moderate the overall contribution of this component. This function exhibits robustness under mathematical conditions while appropriately reflecting the influence of deformation coordination on energy dissipation.

4.3. Comparison of Results

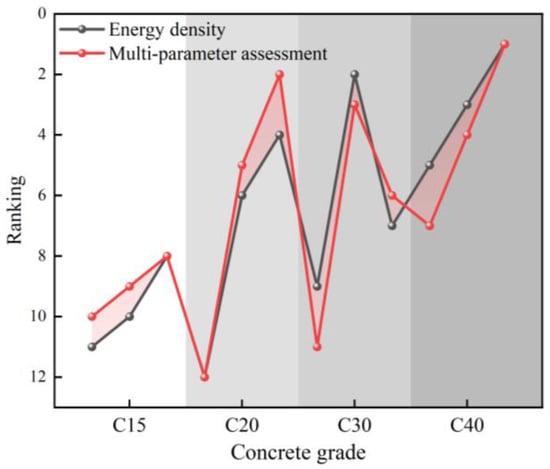

The energy dissipation of concrete specimens using dynamic energy dissipation performance index (Pi) and energy dissipation density (Ud) of multi-parameter evaluation is calculated and compared, as shown in Table 3. Trends in the rankings of the two assessment mechanisms are shown in Figure 10. It can be seen from the analysis that the overall effect of energy dissipation evaluation of concrete specimens of different grades using dynamic energy dissipation performance index and the difference between the evaluation using energy dissipation density is very small, and the curves of the two methods of evaluation have a high degree of coincidence and the change trend is basically the same; both clearly show that the larger the strain rate and the higher the concrete grade, the better the energy dissipation performance. The change trend is basically the same, which clearly shows that the higher the strain rate and the higher the concrete grade, the better the energy dissipation performance, which effectively proves that the calibration of the dynamic energy dissipation performance index is accurate.

Table 3.

Comparison of energy density assessment and multi-parameter assessment results.

Figure 10.

Ranking variation.

The main reasons for the change in rankings after using the multi-parameter energy dissipation assessment are as follows: (1) During dynamic impact, the specimens achieved dynamic compressive strengths lower than the design strengths due to the low strain rate loading of this grade of concrete and the specimen damage was not fully accumulated, i.e., it had excellent static strength rather than excellent energy dissipation performance in dynamic impact. However, the dynamic strengthening capacity of concrete specimens during impact is an important component of impact resistance. After correction for the multi-parameter coefficients, the intrinsic strength advantage is weakened, resulting in a lower ranking (e.g., C30-1, C40-1, C40-2, etc.), while concrete specimens exhibiting strain rate enhancement effects are ranked higher. (2) Better coordination between energy input and material deformation in the impact process, and efficient energy dissipation of the specimens in the form of damage deformation and multi-crack development, which led to improved rankings after correction of multi-parameter coefficients, e.g., C20-2, C20-3, etc. (3) Larger incident energies lead to high energy dissipation density of the specimens in the dynamic impact process, and the dynamic energy dissipation performance index is not singularly affected by the initial loading, and the energy dissipation performance assessment of the specimens limited by the loading conditions is somewhat compensated, e.g., C30-3, C40-1, etc. (4) The ranking fluctuates up and down due to the cross-comparison effect after the re-correction is performed.

The multi-parameter dynamic energy dissipation performance index (Pi) offers a robust characterization of the energy dissipation process in concrete specimens. Built upon energy dissipation density (Ud), Pi retains accuracy and representativeness while exhibiting reduced sensitivity to extraneous influencing factors.

5. Conclusions

This study investigates the dynamic response and energy dissipation characteristics of concrete with different strength grades under impact loading through split Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) experiments. The effects of multiple parameters—including initial loading conditions, peak strain, dynamic compressive strength, and strain rate—on the energy dissipation of concrete were analyzed. A performance index (Pi) for energy dissipation was proposed, which integrates energy dissipation density with the dynamic impact process. The accuracy of this index was subsequently verified. The main conclusions can be summarized as follows:

- In the SHPB test, during the dynamic impact of concrete specimens of different grades, the damage mode is affected by the loading strain rate, and the overall performance is basically from ‘local cracking’ to ‘local damage’ and finally to ‘complete crushing’, and the crushing is diffused from the center of the specimen to the surrounding area, which is basically a brittle damage characteristic. Also, ‘completely crushed’, the crushing from the center of the specimen to the surrounding dispersion, basically shows brittle damage characteristics, and the dynamic impact performance obvious strain-rate strengthening effect. Specifically, the dynamic compressive strength of C15-3 is 22.10 MPa, representing an increase of approximately 47.3%, while that of C40-3 is 46 MPa, showing an increase of approximately 15%.

- Based on the SHPB test results, the differences in energy conversion behavior among concrete specimens of varying grades under dynamic impact loading were analyzed. When employing energy dissipation density to evaluate the energy dissipation of test specimens, the specimen demonstrating the most favorable performance was C40-3 at 0.57 J/cm3, followed by C30-2 at 0.54 J/cm3.The peak strain of C30-2 at a strain rate of 113 s−1 was merely 0.0293, indicating a relatively low degree of fragmentation. Therefore, it is considered that the energy transfer within the concrete specimen during impact is influenced by multiple factors, including initial loading conditions, concrete material properties, and failure mode.

- On the basis of the analysis of energy transfer, the relationship between energy dissipation density and multi-parameters in the dynamic impact process is explored to further reveal the energy dissipation mechanism of concrete specimens with different grades, and the coordination factor λ is introduced to propose a performance index Pi for the integrated multi-parameters to evaluate the dynamic energy dissipation of concrete specimens under the action of impact loading on the basis of energy dissipation density, and to verify its validity, providing reference for the evaluation of structural safety protection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y. and X.J.; methodology, Y.Y. and X.J.; software, X.J.; validation, J.Z. and X.J.; formal analysis, X.J.; investigation, X.J.; resources, K.L.; data curation, M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, X.J. and J.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.J. and M.C.; visualization, K.L. and X.J.; supervision, Y.Y.; project administration, Y.Y.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52478525), the Central Guidance on Local Science and Technology Development Fund of Hubei Province (2025CSA014).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support received from the National Natural Science Foundation of China. My deepest gratitude is directed to the experts for their support and guidance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cao, J.; Lai, T.; Xu, L.; Xu, J. A Novel Optimization Design Framework for Mix Proportion of Mass Concrete: A Case Study of Foundation in Super High-Rise Buildings. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e04819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutu, K.A.; Odei, D.A.; Baniba, P.; Owusu, M. Concrete quality issues in multistory building construction in Ghana: Cases from Kumasi metropolis. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzahosseini, H.; Mirhosseini, S.M.; Zeighami, E. Progressive collapse assessment of reinforced concrete (RC) buildings with high-performance fiber-reinforced cementitious composites (HPFRCC). Structures 2023, 49, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Zhong, Z.; Huang, X.; Sun, W.; Mao, W. Multi-platform simulation of reinforced concrete structures under impact loading. Eng. Struct. 2022, 266, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Yan, Q.; Li, L.; Li, S. Field test and probabilistic vulnerability assessment of a reinforced concrete bridge pier subjected to blast loads. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 143, 106802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, C.; Hao, H. Investigation of ultra-high performance concrete slab and normal strength concrete slab under contact explosion. Eng. Struct. 2015, 102, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhu, W.; Li, M.; Jia, J.; Li, Z. Concrete spalling behavior and damage evaluation of concrete members with different cross-sectional properties under contact explosion. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2023, 181, 104753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.Y.; Deng, Y.J.; Liu, L.B.; Zhang, L.H.; Yao, Y. Dynamic mechanical properties and energy dissipation analysis of rubber-modified aggregate concrete based on SHPB tests. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 445, 137920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Huang, L.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, L. Seismic resilience assessment of self-centering prestressed concrete frame with different energy dissipation ratio and second stiffness. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 63, 105516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Guan, Z.; Qin, J.; Wen, Y.; Lai, Z. Strain rate effect of concrete based on split Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) test. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86, 108856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Yu, X.; Guo, Z.; Xiao, L. Numerical investigation of the dynamic increase factor of ultra-high performance concrete based on SHPB technology. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 325, 126756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Guo, Y.; Shen, A.; Deng, S.; Wu, H.; Pan, H. Dynamic mechanical performance of cellulose fiber concrete under compressive impact loading. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 493, 143192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xue, G.; Wang, W. Compressive behavior of rubberized concrete under high strain rates. Structures 2023, 56, 104983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelei, C.; Sherong, Z.; Jianwei, Z.; Hu, H. Dynamic compressive behavior of steel fiber synergistically reinforced cellular concrete under high strain-rate loading. Structures 2024, 63, 106437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Bai, E.; Ren, B.; Xia, W.; Xu, J. Strengthening effect of monolayer graphene oxide on the impact mechanical properties of concrete and the mechanism analysis based on fractal theory. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 428, 136305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, W.; Li, S.; Deng, Q.; Chen, M.; Yu, Q. Effects of coarse aggregates size on dynamic characteristics of ultra-high performance concrete: Towards enhanced impact resistance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, P.; Shi, K.; Bai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Guo, W.; Feng, Z.; Song, Z. Investigation on the temperature-strain rate coupled mechanical behavior and constitutive modeling of foamed concrete using a high-temperature viscoelastic SHPB technique. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e05476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Yang, L.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Deng, X.; Wei, P.; Lü, J. Energy dissipation and fractal characteristics of basalt fiber reinforced concrete under impact loading. Structures 2022, 46, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshi, M.; Dalalbashi, A.; Soheili, H. Energy dissipation capacity of an optimized structural lightweight perlite concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 389, 131765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aown, M.; Al-Deen, S.; Mohotti, D. Impact of crumb rubber and pre-treatment on the energy absorption of geopolymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 492, 142983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Cui, Z.; Zhou, J.; Li, C. Predicting energy absorption characteristic of rubber concrete materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 465, 140248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zou, S.; Wen, J.; Zhang, Y. Study on the damage behavior and energy dissipation characteristics of basalt fiber concrete using SHPB device. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 368, 130413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, K.; Chai, J.; Qin, Y.; Li, X.; Duan, M.; Liang, D. Exploring the brittleness and fractal characteristics of basalt fiber reinforced concrete under impact load based on the principle of energy dissipation. Mater. Struct. 2022, 55, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, X.; Fu, J.; Zhu, N.; Chen, D.; Wang, Y.; Ding, S. Experimental study on compressive behavior and failure characteristics of imitation steel fiber concrete under uniaxial load. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 399, 132599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Q.M. Damage behavior and energy absorption characteristics of foamed concrete under dynamic load. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 357, 129340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.M.; Iqbal, M.A. Strain rate and size effects on dynamic tensile behaviour of standard and high-strength concrete: An experimental study. Structures 2024, 63, 106325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.; Zhang, L.; Peng, C.; Zhou, Z.; Shen, H. Experimental study on hybrid fiber reinforced high performance concrete properties: Investigatingcomprehensive energy consumption capacity. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 443, 137682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Ren, H.-Q.; Long, Z.-L.; Guo, R.-Q.; Du, K.-M.; Chen, S.-S.; Zheng, Z.-H. Comparison study on the impact compression mechanical properties of coral aggregate concrete and ordinary Portland concrete. Structures 2022, 44, 1403–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Han, W.; Zheng, J.; Lin, S.; Yuan, S. Effects of basalt fibre and rubber particles on the mechanical properties and impact resistance of concrete. Structures 2024, 65, 106677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, C. Experimental study on impact resistance of steel-fiber-reinforced two-grade aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 373, 130901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fu, R.; Dong, H. Carbon nanofibers and PVA fiber hybrid concrete: Abrasion and impact resistance. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80, 107894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.