Study on Multi-Solid Waste Alkali-Activated Material Concrete via RSM

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiment

2.1. Raw Materials

2.1.1. Alkali Activators

2.1.2. Fine Aggregate (Sand for Mortar and Concrete)

2.1.3. Coarse Aggregate (Crushed Stone for Concrete)

2.2. Experimental Methods

- (1)

- Mortar Test

- (2)

- Concrete Test

2.3. Analysis and Testing

3. Experimental Design

3.1. Response Factor Parameter Experimental Design

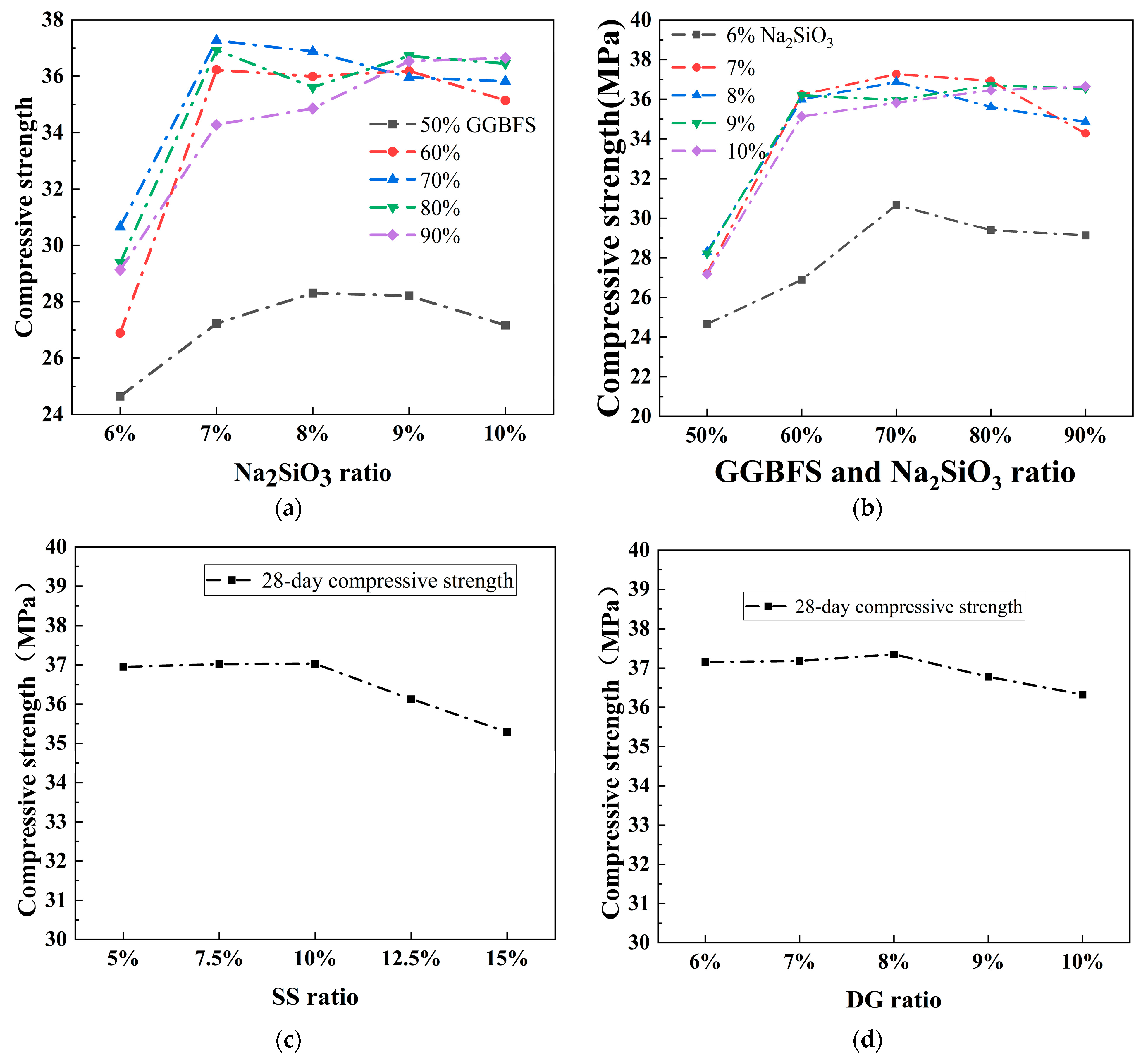

3.1.1. Test Analysis

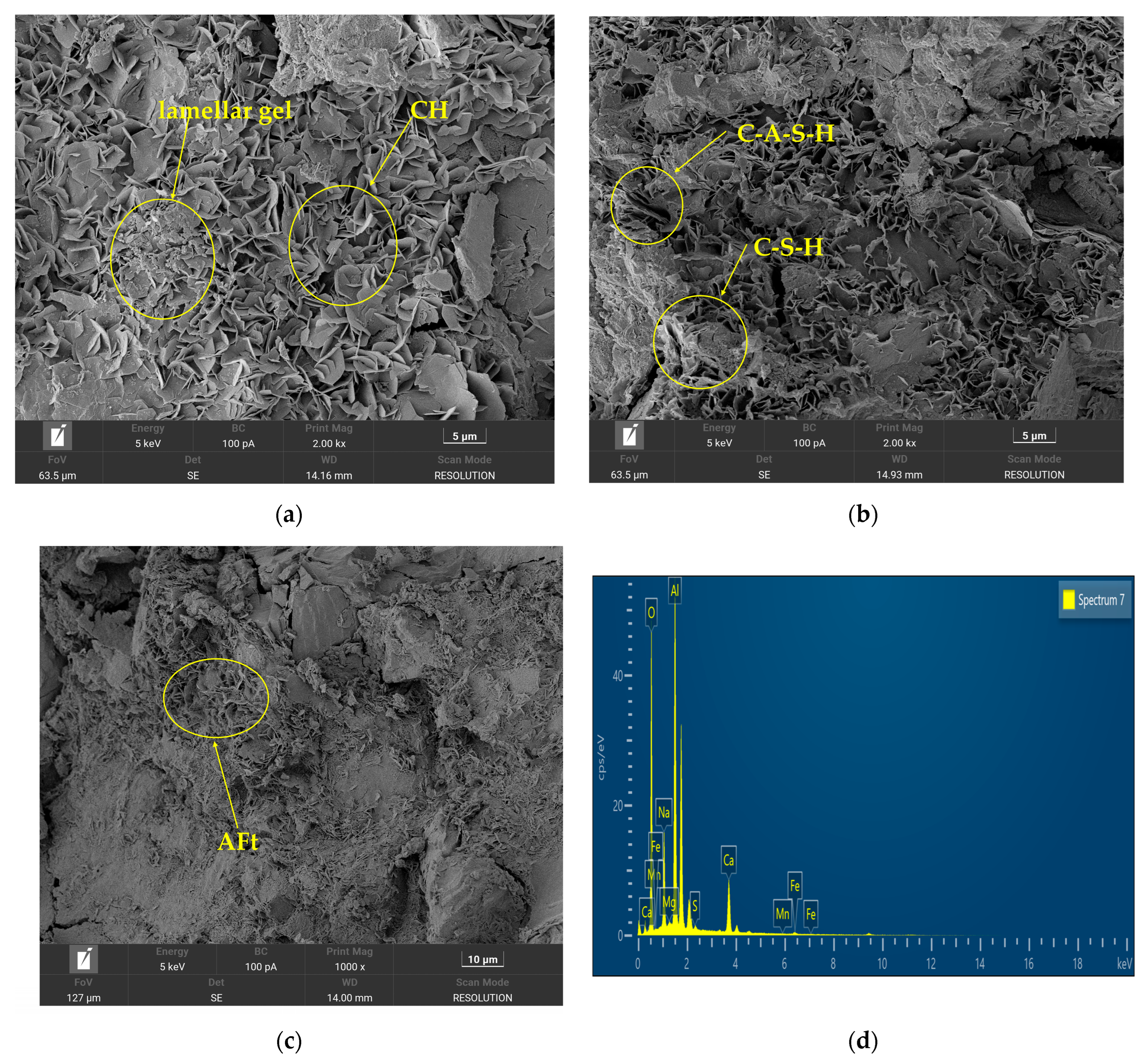

3.1.2. Microstructural Analysis of Cementitious Materials

- (1)

- Na2SiO3-activated GGBFS–fly ash system

- (2)

- Na2SiO3-activated slag–fly ash–steel slag system

- (3)

- Na2SiO3-activated slag-fly ash-steel slag-desulfurized gypsum system

3.2. Experimental Design of Response Surface Methodology (RSM) for Concrete

4. Results and Analysis of RSM Tests

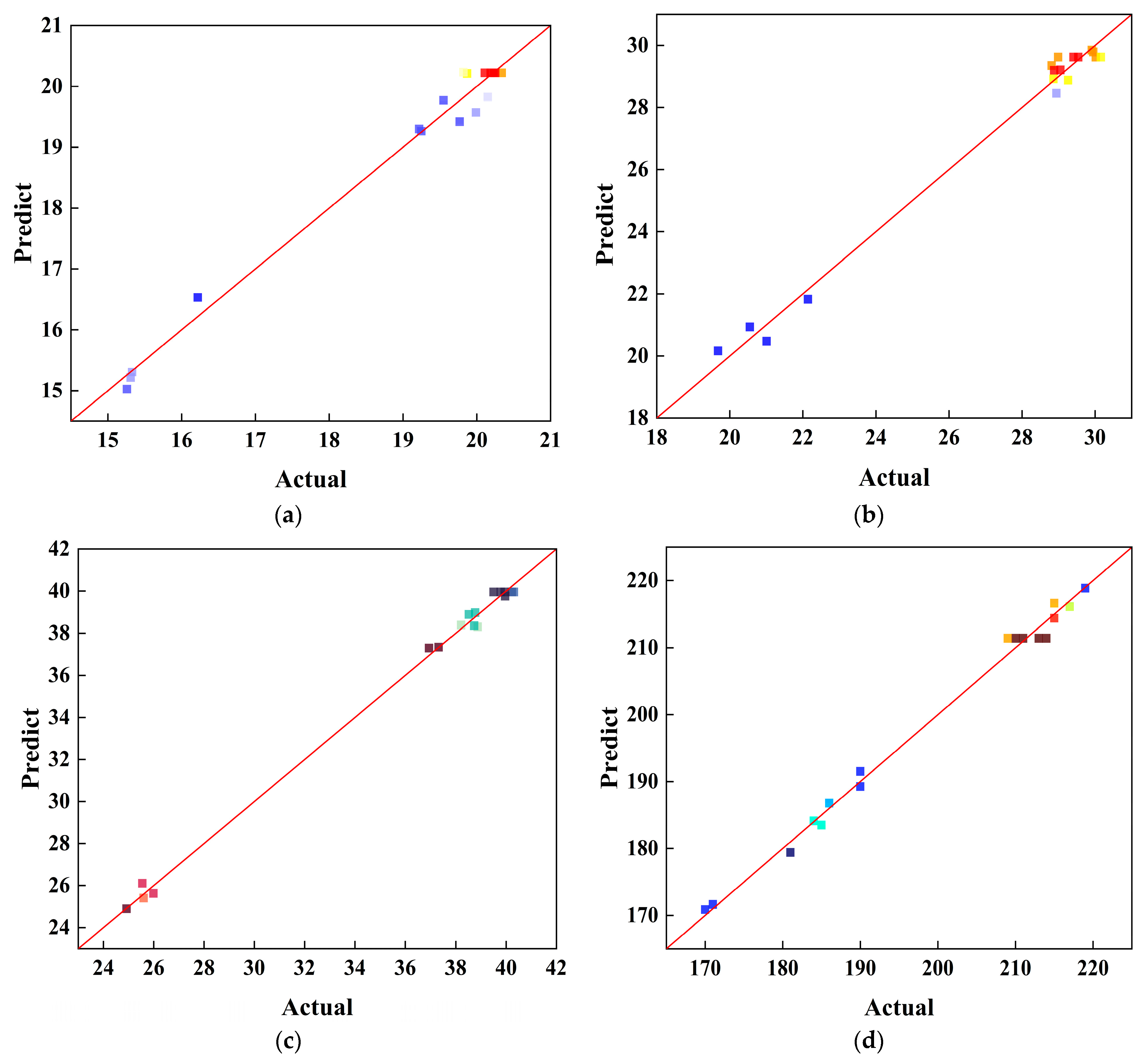

4.1. Development and Rationality Analysis of the Regression Model

0.0125X2X3 + 0.0780X12 − 2.51X22 − 0.4395X32

0.2975X2X3 + 0.2105X12 − 4.62X22 − 0.3920X32

0.2175X1X2 − 0.4695X12 − 7.80X22 − 0.4895X32

12.82X12 − 10.83X22 − 3.08X32

4.2. Analysis of Model Fit

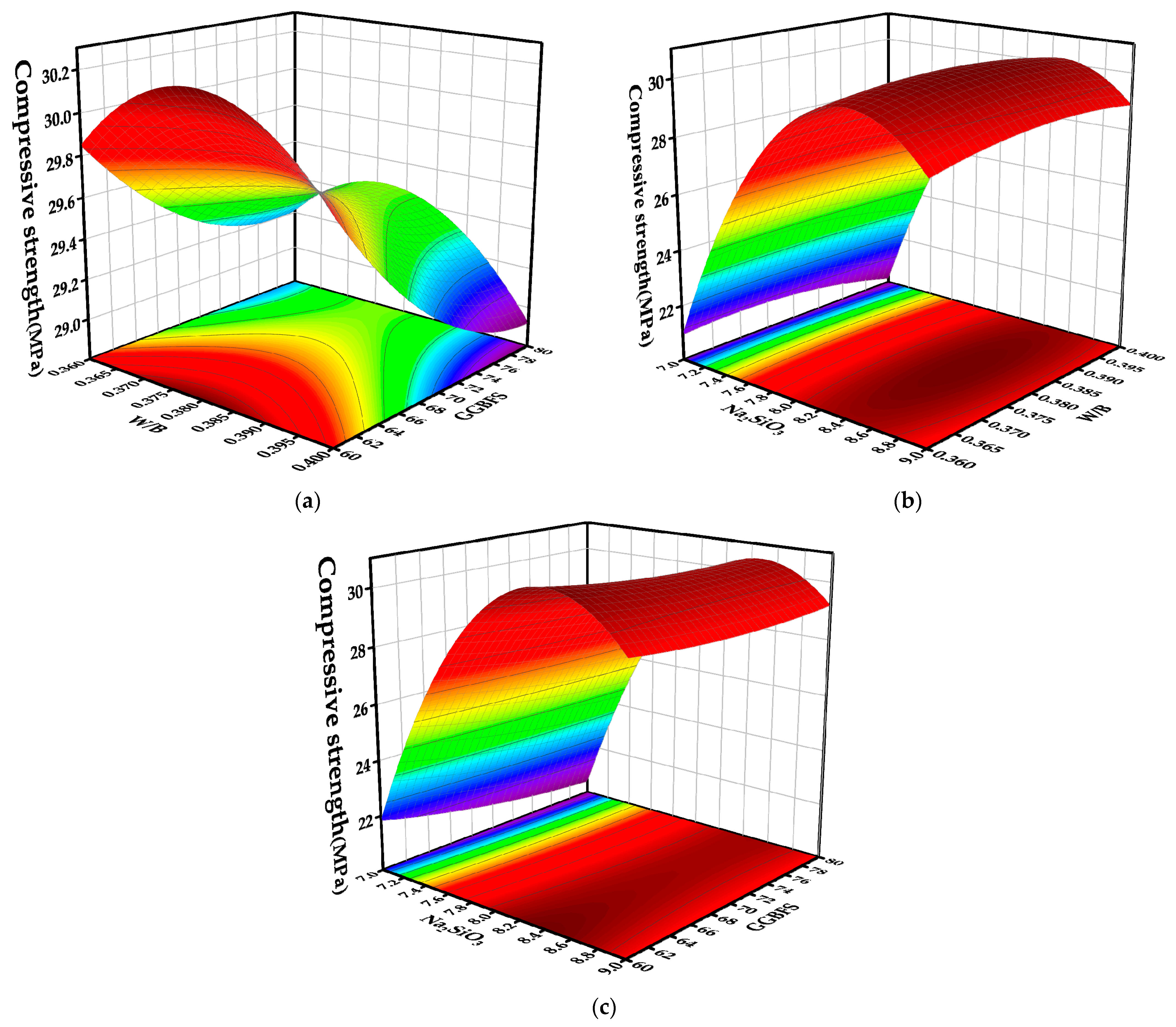

4.3. Effects of Various Factors and Their Interaction Terms on Response Values

4.3.1. Compressive Strength

4.3.2. Slump

4.4. Response Surface Optimization Validation

4.5. Microstructural Analysis of AAM Concrete

Limitations of Microstructural Characterization

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, K.; Gong, K.; Zhou, Q.; Zhao, S.; Guo, H.; Qian, X. Estimating the feasibility of using industrial solid waste as raw material for polyurethane composites with low fire hazards. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 257, 120606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.X.; Cen, K. Empirical assessing cement CO2 emissions based on China’s economic and social development during 2001−2030. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 653, 200−211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, A.İ.; Tunç, U.; Karalar, M.; Althaqafi, E.; Özkılıç, Y.O. Sustainable utilization of aluminum waste in geopolymer concrete: Influence of alkaline activation on microstructure and mechanical properties. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2025, 64, 20250152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, A.İ.; Karalar, M.; Tunç, U.; Şahan, M.F.; Althaqafi, E.; Umiye, O.A.; Özkılıç, Y.O. Mechanical and impact behavior of lightweight geopolymer concrete produced by pumice and waste rubber. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, A.İ.; Tunç, U.; Karalar, M.; Şahan, M.F.; Özkılıç, Y.O. Study on mechanical, dynamic impact, and microstructural properties of eco-friendly geopolymer paving stones cured in ambient conditions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 464, 140132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Dong, S.; Yang, J.; Gou, J.; Shao, L.; Ma, L.; Nie, R.; Shi, J.; Du, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Industrial solid waste as oxygen carrier in chemical looping gasification technology: A review. J. Energy Inst. 2024, 116, 101694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Lei, X.W.; Zhang, H.G.; Yu, P.; Zhou, Y.T.; Huang, X.J. Durability and heavy metals long-term stability of alkali-activated sintered municipal solid waste incineration fly ash concrete in acidic environments. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 462, 139990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, S.; Jang, J.G. Acid and sulfate resistance of seawater based alkali activated fly ash: A sustainable and durable approach. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 281, 122601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Cui, H.; Cui, L.; Yang, S.; Zhang, C.; Liu, W.; Zheng, D. Mutual Activation Mechanism of Cement–GGBS–Steel Slag Ternary System Excited by Sodium Sulfate. Buildings 2024, 14, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.X.; Yu, Q.B.; Zuo, Z.L.; Yang, F.; Duan, W.j.; Qin, Q. Blast furnace slag obtained from dry granulation method as a component in slag cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 131, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, S.A.; Provis, J.L.; Rose, V.; Mejía de Gutierrez, R. Evolution of binder structure in sodium silicate-activated slag-metakaolin blends. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2011, 33, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, Y.; Wang, J.; Ma, T.; Wang, S.; Li, C. Modification Mechanism of Desulfurized Gypsum on Alkali-Activated Slag-Fly Ash Mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 396, 132400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, M.; Megat Johari, M.A.; Maslehuddin, M.; Yusuf, M.O. Sulfuric acid resistance of alkali/slag activated silicomanganese fume-based mortars. Struct. Concr. 2021, 22, E400–E414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Liu, J.X.; Qi, L.Q. Effects of temperature and carbonation curing on the mechanical properties of steel slag-cement binding materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 124, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Zeng, Z.Y.; Jiang, Z.W.; Chen, Q. Incorporation of bamboo charcoal for cement-based humidity adsorption material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 215, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Qian, J.; Yang, Y.; Fan, C.; Yue, Y. Optimization of gypsum and slag contents in blended cement containing slag. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 112, 103674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Chen, Z. Effect of silicate modulus of water glass on the hydration of alkali-activated converter steel slag. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2019, 138, 2221−2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.X.; Yu, Q.J.; Wei, J.X.; Zhang, T.S. Structural characteristics and hydration kinetics of modified steel slag. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011, 41, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.S.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Sun, J. Advances in understanding the alkali-activated metallurgical slag. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 19, 8795588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondar, D.; Vinai, R. Chemical and Microstructural Properties of Fly Ash and Fly Ash/Slag Activated by Waste Glass-Derived Sodium Silicate. Crystals 2022, 12, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Seibou, A.-O.; Li, M.; Kaci, A.; Ye, J. Bamboo Sawdust as a Partial Replacement of Cement for the Production of Sustainable Cementitious Materials. Crystals 2021, 11, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, R.M.; Butt, F.; Zhu, X.; Jiang, T.; Tufail, R.F. A comprehensive study on the factors affecting the workability and mechanical properties of ambient cured fly ash and slag-based geopolymer concrete. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, T.; Matos, A.M.; Sousa-Coutinho, J. Mortar with wood waste ash: Mechanical strength, carbonation resistance and ASR expansion. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 49, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilar, F.A.; Alqahtani, D.A.; Shilar, M.; Khan, T.M.Y. Valorization of agricultural and industrial wastes in geopolymer foam concrete, a ternary binder approach using corncob ash, red mud, and fly ash. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2026, 24, e05716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nana, A.; Tome, S.; Yanze, G.A.N.; Singla, R.; Liebscher, M.; Kamseu, E.; Mechtcherine, V.; Kumar, S.; Leonelli, C. Durability of Geopolymer Mortars from Feldspar Waste: Seawater, Nitric and Sulfuric Acids Resistance, Phase Evolution and Microstructure. Iran J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. 2025, 49, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 17671-2021; Test Method of Cement Mortar Strength (ISO Method). Beijing Concrete Association: Beijing, China, 2022.

- GB/T 50081-2002; Standard for Test Methods of Mechanical Properties on Ordinary Concrete. China Academy of Building Research: Beijing, China, 2007.

- Zhao, G.; Pan, X.; Yan, H.; Tian, J.; Han, Y.; Guan, H.; Ruan, Y.; Liu, B.; Chen, F. Optimization and characterization of GGBFS-FA based alkali-activated CLSM containing Shield-discharged soil using Box-Behnken response surface design method. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, I.; Bernal, S.A.; Provis, J.L.; San Nicolas, R.; Hamdan, S.; van Deventer, J.S.J. Modification of phase evolution in alkali-activated blast furnace slag by the incorporation of fly ash. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2014, 45, 125−135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyebisi, S.; Alomayri, T. Artificial intelligence-based prediction of strengths of slag-ash-based geopolymer concrete using deep neural networks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 400, 132606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, D.; Peethamparan, S.; Neithalath, N. Structure and strength of Na2SiO3 activated concretes containing fly ash or GGBFS as the sole binder. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2010, 32, 432−441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.H.; Kayali, O. Chloride binding ability and the onset corrosion threat on alkali-activated GGBFS and binary blend pastes. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2018, 22, 1017−1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, T.H.; Xiao, J.Z.; Duan, Z.H.; Li, S. Geopolymers made of recycled brick and concrete powder-A critical review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 330, 127232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyebisi, S.; Ede, A.; Olutoge, F.; Olukanni, D. Assessment of activity moduli and acidic resistance of slag-based geopolymer concrete incorporating pozzolan. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2020, 13, e00394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shen, J.L.; Lin, H.; Li, Y.Q. Optimization design for alkali-activated slag-fly ash geopolymer concrete based on artificial intelligence considering compressive strength, cost, and carbon emission. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 75, 106929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.L.; Cheng, H.R.; Zhang, M.; Qin, Y.J.; Cao, J.Q.; Cao, X.Y. Alkali-Activated Slag–Fly Ash–Desert Sand Mortar for Building Applications: Flowability, Mechanical Properties, Sulfate Resistance, and Microstructural Analysis. Buildings 2025, 15, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanferla, P.; Finocchiaro, C.; Gharzouni, A.; Barone, G.; Mazzoleni, P.; Rossignol, S. High temperature behavior of sodium and potassium volcanic ashes-based alkali-activated materials (Mt. Etna, Italy). Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 408, 133702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casar, Z.; Mohamed, A.K.; Bowen, P.; Scrivener, K. Atomic-Level and Surface Structure of Calcium Silicate Hydrate Nanofoils. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2023, 127, 18652–18661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Materials | CaO (%) | SiO2 (%) | Al2O3 (%) | Fe2O3 (%) | MgO (%) | SO3 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GGBFS | 34.00 | 34.20 | 17.60 | 1.01 | 6.21 | 1.62 |

| FA | 5.60 | 43.00 | 23.00 | 2.50 | 0.95 | 0.80 |

| SS | 31.00 | 12.10 | 0.00 | 26.50 | 4.10 | 0.00 |

| DG | 30.70 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 43.82 |

| Experimental Group | GGBFS/FA/SS/DG | Na2SiO3 (%) | W/B | Standard Curing | Compressive Strength Test (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 50/50/0/0 | Concentration 6%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A2 | 60/40/0/0 | Concentration 6%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A3 | 70/30/0/0 | Concentration 6%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A4 | 80/20/0/0 | Concentration 6%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A5 | 90/10/0/0 | Concentration 6%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A6 | 50/50/0/0 | Concentration 7%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A7 | 60/40/0/0 | Concentration 7%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A8 | 70/30/0/0 | Concentration 7%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A9 | 80/20/0/0 | Concentration 7%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A10 | 90/10/0/0 | Concentration 7%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A11 | 50/50/0/0 | Concentration 8%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A12 | 60/40/0/0 | Concentration 8%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A13 | 70/30/0/0 | Concentration 8%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A14 | 80/20/0/0 | Concentration 8%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A15 | 90/10/0/0 | Concentration 8%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A16 | 50/50/0/0 | Concentration 9%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A17 | 60/40/0/0 | Concentration 9%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A18 | 70/30/0/0 | Concentration 9%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A19 | 80/20/0/0 | Concentration 9%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A20 | 90/10/0/0 | Concentration 9%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A21 | 50/50/0/0 | Concentration 10%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A22 | 60/40/0/0 | Concentration 10%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A23 | 70/30/0/0 | Concentration 10%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A24 | 80/20/0/0 | Concentration 10%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| A25 | 90/10/0/0 | Concentration 10%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| B1 | 60/27/5/8 | Concentration 8%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| B2 | 60/24.5/7.5/8 | Concentration 8%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| B3 | 60/22/10/8 | Concentration 8%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| B4 | 60/19.5/12.5/8 | Concentration 8%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| B5 | 60/17/15/8 | Concentration 8%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| C1 | 60/24/10/6 | Concentration 8%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| C2 | 60/23/10/7 | Concentration 8%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| C3 | 60/22/10/8 | Concentration 8%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| C4 | 60/21/10/9 | Concentration 8%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| C5 | 60/20/10/10 | Concentration 8%, modulus 1.2 | 0.5 | (20 ± 2) °C, RH ≥ 95% | 40 × 40 × 160 |

| Coding | GGBFS (%) | Na2SiO3 (%) | W/B |

|---|---|---|---|

| −1 | 60 | 7 | 0.36 |

| 0 | 70 | 8 | 0.38 |

| 1 | 80 | 9 | 0.40 |

| Serial Number | GGBFS (%) | Na2SiO3 (%) | W/B | Y1 (3-Day) | Y2 (7-Day) | Y3 (28-Day) | Y4 (Slump) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 70 | 7 | 0.36 | 15.33 | 20.55 | 25.55 | 170 |

| 2 | 70 | 9 | 0.36 | 19.22 | 28.94 | 37.33 | 184 |

| 3 | 70 | 7 | 0.40 | 15.31 | 19.68 | 24.92 | 219 |

| 4 | 70 | 9 | 0.40 | 19.25 | 29.26 | 38.87 | 217 |

| 5 | 60 | 7 | 0.38 | 16.22 | 22.14 | 25.60 | 185 |

| 6 | 60 | 9 | 0.38 | 19.55 | 28.81 | 36.95 | 190 |

| 7 | 80 | 7 | 0.38 | 15.26 | 21.01 | 25.99 | 186 |

| 8 | 80 | 9 | 0.38 | 20.15 | 28.88 | 38.21 | 190 |

| 9 | 60 | 8 | 0.36 | 19.87 | 29.91 | 38.73 | 171 |

| 10 | 60 | 8 | 0.40 | 19.82 | 29.95 | 38.77 | 215 |

| 11 | 80 | 8 | 0.36 | 19.99 | 29.05 | 39.96 | 181 |

| 12 | 80 | 8 | 0.40 | 19.77 | 28.86 | 38.52 | 215 |

| 13 | 70 | 8 | 0.38 | 20.11 | 30.02 | 39.94 | 210 |

| 14 | 70 | 8 | 0.38 | 20.23 | 29.41 | 40.23 | 214 |

| 15 | 70 | 8 | 0.38 | 20.34 | 29.54 | 40.31 | 211 |

| 16 | 70 | 8 | 0.38 | 20.25 | 30.16 | 39.79 | 209 |

| 17 | 70 | 8 | 0.38 | 20.19 | 28.99 | 39.50 | 213 |

| Response | Source | Sum of Squares | Degree of Freedom | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y1 | Model | 60.71 | 9 | 6.75 | 588.42 | <0.0001 | Significant |

| Residual | 0.0802 | 7 | 0.0115 | ||||

| Lack of Fit | 0.0519 | 3 | 0.0173 | 2.44 | 0.2039 | Not Significant | |

| Pure Error | 0.0283 | 4 | 0.0071 | ||||

| Cor Total | 60.79 | 16 | |||||

| Y2 | Model | 225.80 | 9 | 25.09 | 70.57 | <0.0001 | Significant |

| Residual | 2.49 | 7 | 0.3555 | ||||

| Lack of Fit | 1.59 | 3 | 0.5299 | 2.36 | 0.2128 | Not Significant | |

| Pure Error | 0.8989 | 4 | 0.2247 | ||||

| Cor Total | 228.29 | 16 | |||||

| Y3 | Model | 569.67 | 9 | 63.30 | 254.29 | <0.0001 | Significant |

| Residual | 1.74 | 7 | 0.2489 | ||||

| Lack of Fit | 1.31 | 3 | 0.4354 | 3.99 | 0.1071 | Not Significant | |

| Pure Error | 0.4361 | 4 | 0.1090 | ||||

| Cor Total | 571.41 | 16 | Significant | ||||

| Y4 | Model | 4692.02 | 9 | 521.34 | 119.85 | <0.0001 | Significant |

| Residual | 30.45 | 7 | 4.35 | ||||

| Lack of Fit | 13.25 | 3 | 4.42 | 1.03 | 0.4698 | Not Significant | |

| Pure Error | 17.20 | 4 | 4.30 | ||||

| Cor Total | 4722.47 | 16 | Significant |

| Response | Numeric value | X1 | X2 | X3 | X1X2 | X1X3 | X2X3 | X12 | X22 | X32 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y1 | F-value | 0.9170 | 2803.93 | 0.7371 | 53.07 | 0.6303 | 0.0545 | 2.23 | 2308.47 | 70.95 |

| p-value | 0.3702 | <0.0001 | 0.4190 | 0.0002 | 0.4533 | 0.8221 | 0.1786 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Y2 | F-value | 3.19 | 371.62 | 0.1723 | 1.01 | 0.0372 | 0.9958 | 0.5248 | 253.29 | 1.82 |

| p-value | 0.1175 | <0.0001 | 0.6905 | 0.3478 | 0.8525 | 0.3516 | 0.4923 | <0.0001 | 0.2193 | |

| Y3 | F-value | 3.47 | 1220.51 | 0.1206 | 0.7602 | 2.20 | 4.73 | 3.73 | 1028.33 | 4.05 |

| p-value | 0.1046 | <0.0001 | 0.7386 | 0.4122 | 0.1816 | 0.0662 | 0.0948 | <0.0001 | 0.0840 | |

| Y4 | F-value | 3.48 | 12.67 | 735.63 | 0.0575 | 5.75 | 14.73 | 159.21 | 113.42 | 9.15 |

| p-value | 0.1045 | 0.0092 | <0.0001 | 0.8174 | 0.0477 | 0.0065 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0192 |

| Response | 3 d Compressive Strength | 3 d Compressive Strength | 28 d Compressive Strength | Slump |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Std. Dev. | 0.1071 | 0.5962 | 0.4989 | 2.09 |

| Mean | 18.87 | 27.36 | 35.83 | 198.82 |

| C.V. % | 0.5673 | 2.18 | 1.39 | 1.05 |

| R2 | 0.9987 | 0.9891 | 0.9970 | 0.9936 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.9970 | 0.9751 | 0.9930 | 0.9853 |

| Predicted R2 | 0.9856 | 0.8824 | 0.9622 | 0.9494 |

| Adeq precision | 60.8610 | 21.1897 | 39.3378 | 30.0069 |

| Experimental Plan | GGBFS (%) | Na2SiO3 (%) | W/B |

|---|---|---|---|

| R (28-day) | 73.887 | 8.384 | 0.380 |

| Number | 3-Day | 7-Day | 28-Day | Slump |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted Strength | 20.697 MPa | 30.851 MPa | 41.260 MPa | 227.757 mm |

| Experimental Strength | 21.62 MPa | 29.91 MPa | 42.76 MPa | 220.5 mm |

| Absolute Error | +0.923 | −0.941 | 1.500 | 7.257 |

| Error Percentage | +4.27% | −3.15 | +3.64% | −3.37% |

| Confidence interval (95%) | [20.02, 21.37] | [29.66, 32.04] | [40.27, 42.25] | [223.61, 231.90] |

| OPC (P.O42.5) | 19.55 MPa | 28.87 MPa | 38.55 MPa | 235 mm |

| Evaluation Indicators | AAC | OPC (P.O42.5) | Difference Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial setting time (min) | 120 | 210 | AAC rapid initial setting |

| Final setting time (min) | 210 | 300 | AAC Rapid Final Setting |

| Testing Period | AAC (Slump) | Loss Ratio (%) | OPC (P.O42.5) | Loss Ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (min) | 220.5 | 0 | 235 | 0 |

| 30 (min) | 185.0 | 16.1 | 215.2 | 8.4 |

| 60 (min) | 150.5 | 31.7 | 200.4 | 14.7 |

| Evaluation Indicators | AAC | OPC (P.O42.5) | Difference Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water seepage | NO | Minor water seepage | AAC rapid initial setting |

| 1 h Penetration Resistance Increase (MPa) | 9.1 | 4.5 | No rapid hardening occurs |

| 3 h Status | Reshapeable, can be formed into a ball by hand | easily loosened | AAC exhibits superior cohesive retention. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Mou, L.; Jia, J.; Wan, Z.; Meng, Z.; Zhou, X. Study on Multi-Solid Waste Alkali-Activated Material Concrete via RSM. Buildings 2026, 16, 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010198

Wang L, Mou L, Jia J, Wan Z, Meng Z, Zhou X. Study on Multi-Solid Waste Alkali-Activated Material Concrete via RSM. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):198. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010198

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Lijun, Lin Mou, Jilong Jia, Zhichao Wan, Zhipeng Meng, and Xiaolong Zhou. 2026. "Study on Multi-Solid Waste Alkali-Activated Material Concrete via RSM" Buildings 16, no. 1: 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010198

APA StyleWang, L., Mou, L., Jia, J., Wan, Z., Meng, Z., & Zhou, X. (2026). Study on Multi-Solid Waste Alkali-Activated Material Concrete via RSM. Buildings, 16(1), 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010198