From Tool-Based Training to Integrated Studios: A Review of BIM Education in Architecture

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How has BIM been integrated into architectural curricula across academic levels, instructional models, and software ecosystems?

- How do disciplinary, institutional, and regional contexts shape BIM education and its connection to professional practice?

- What challenges and opportunities emerge for developing architecture-oriented BIM education models distinct from engineering-centered approaches?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Scope

2.2. Research Process, Frame, and Analytical Framework

- (1)

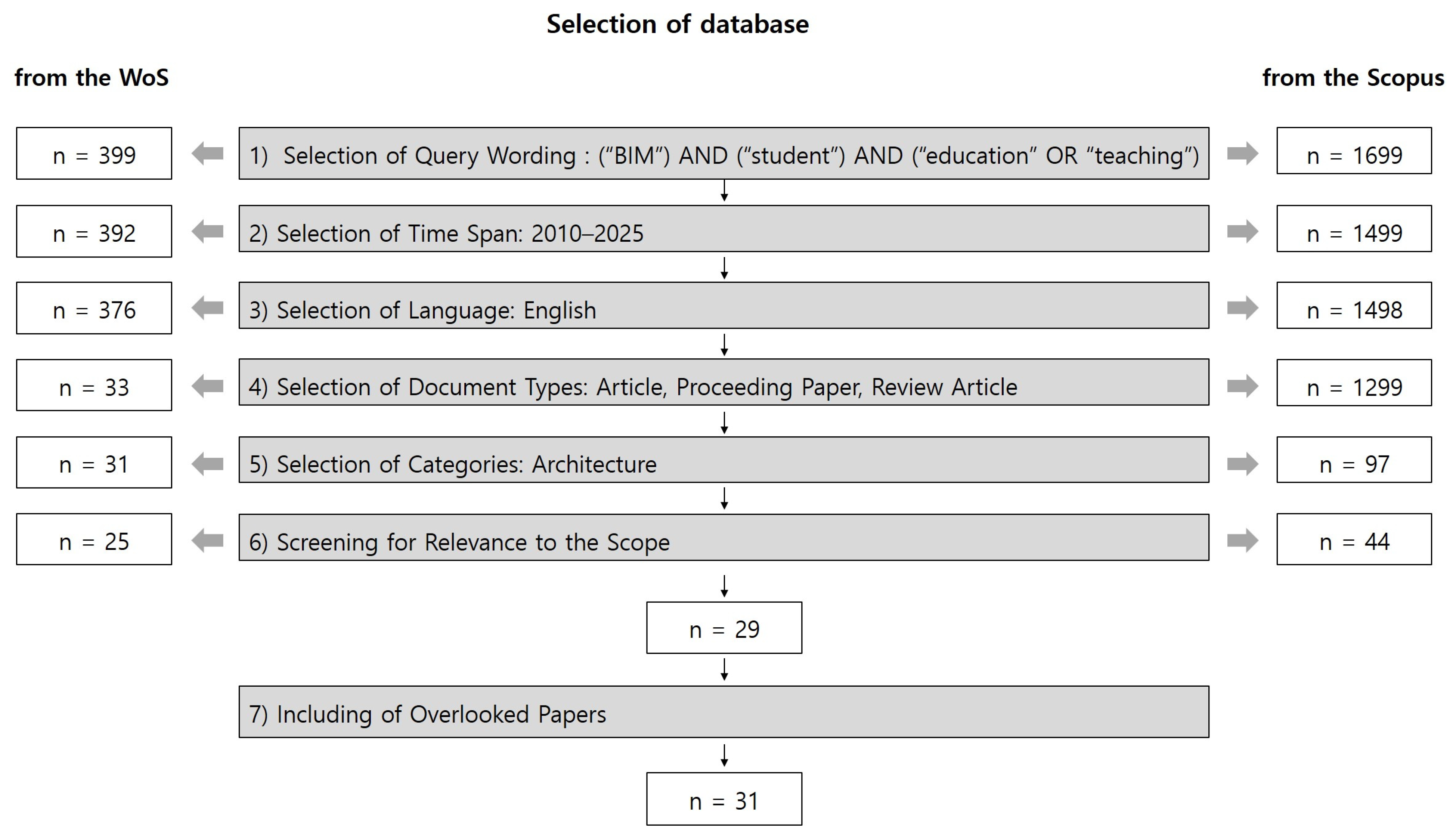

- Phase 1: Data Collection and Screening

- (2)

- Phase 2: Data Extraction and Coding

- (3)

- Phase 3: Analytical Framing and Interpretation

- Comparative dimension—identifying disciplinary, regional, and institutional variations in BIM education;

- Pedagogical dimension—classifying instructional approaches and synthesizing recurring educational challenges and strategies;

- Theoretical dimension—situating findings within broader educational paradigms, including experiential learning, reflective design thinking, and sociotechnical adoption.

2.3. Study Selection

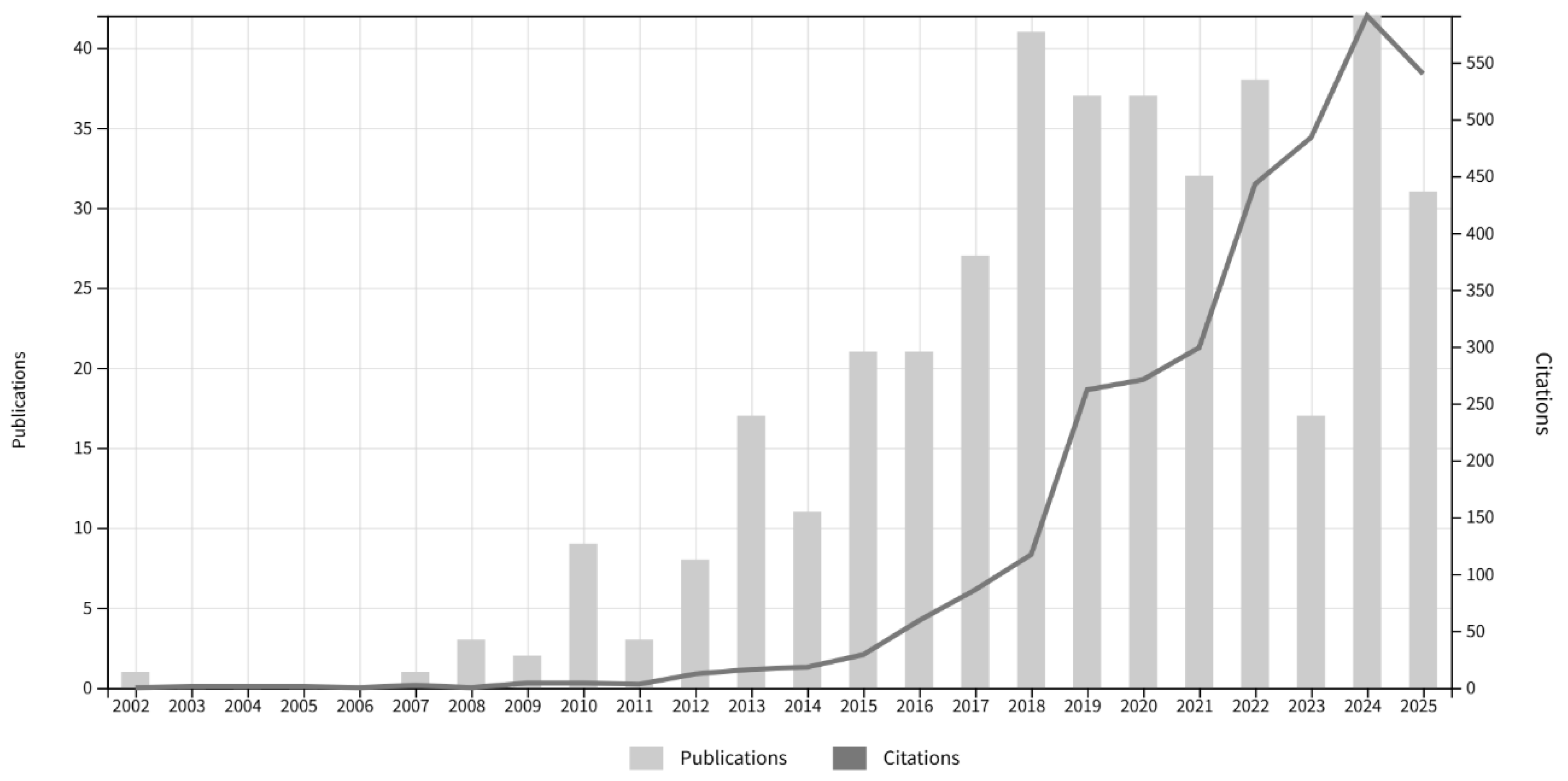

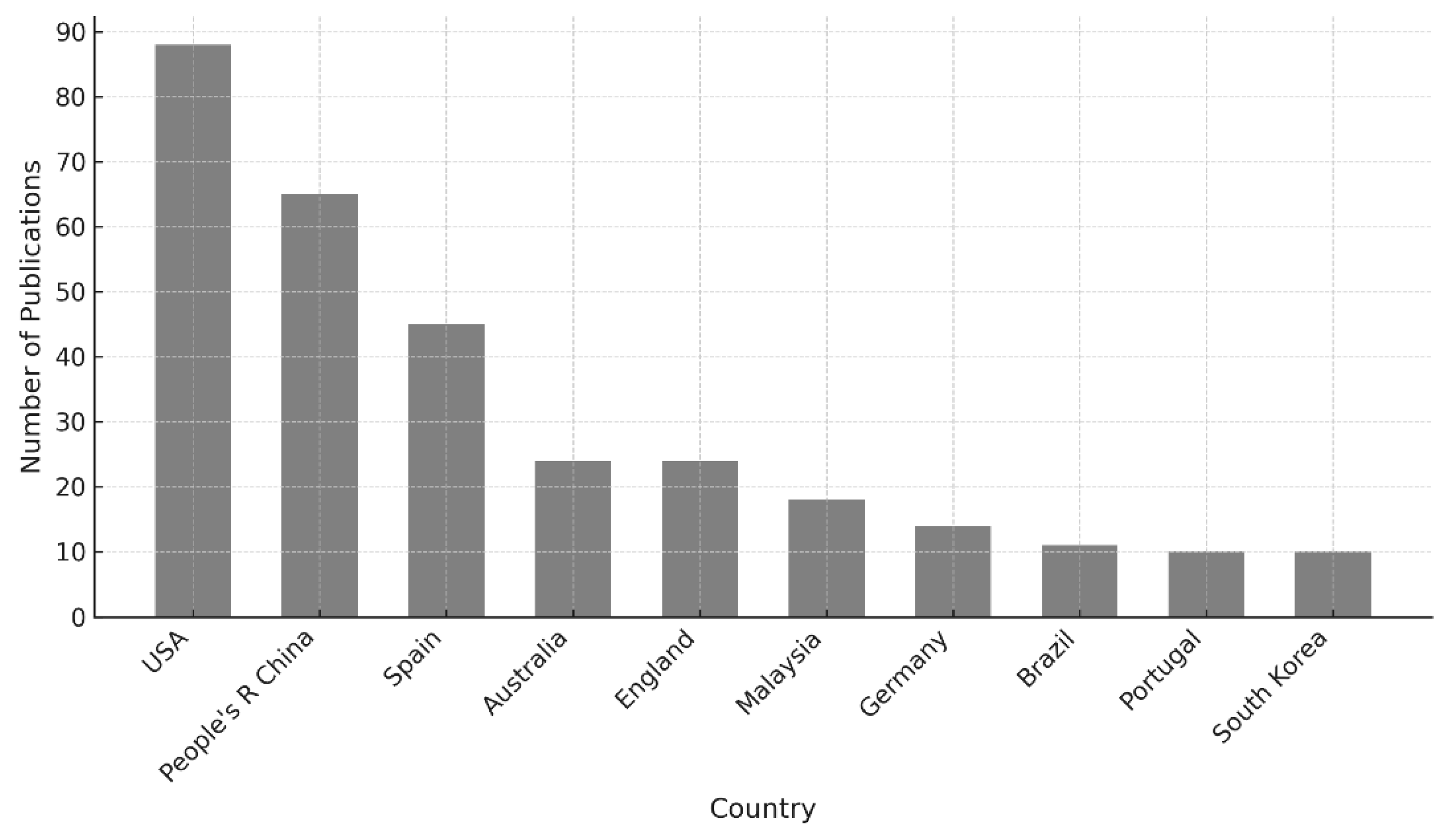

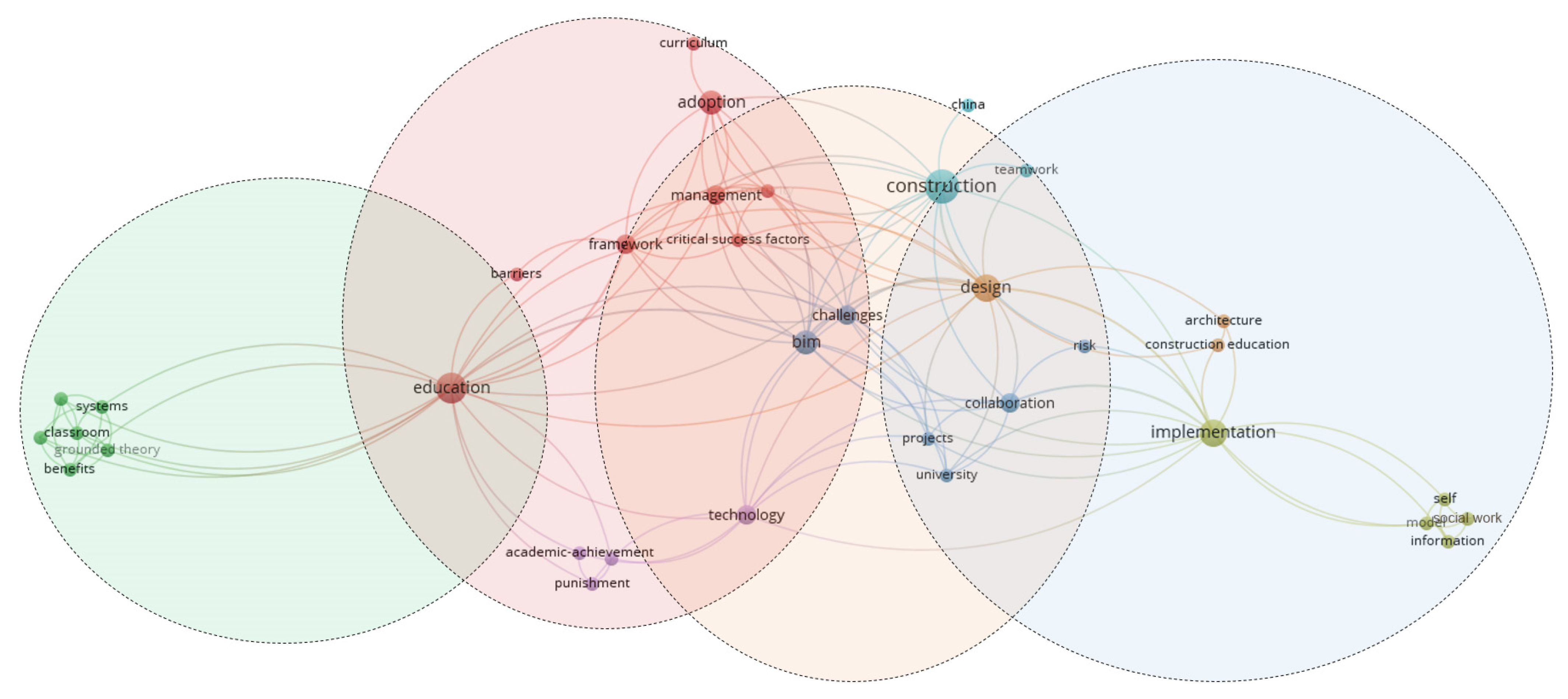

2.4. Preliminary Bibliometric Overview of BIM Education Research

- (1)

- Publication and Citation Year

- (2)

- Geographic Distribution and Research Productivity

- (3)

- Distribution by Research Area

- (4)

- Keyword Co-occurrence Network

3. Results from the In-Depth Review

3.1. Curriculum Structure and Pedagogical Trends

- (1)

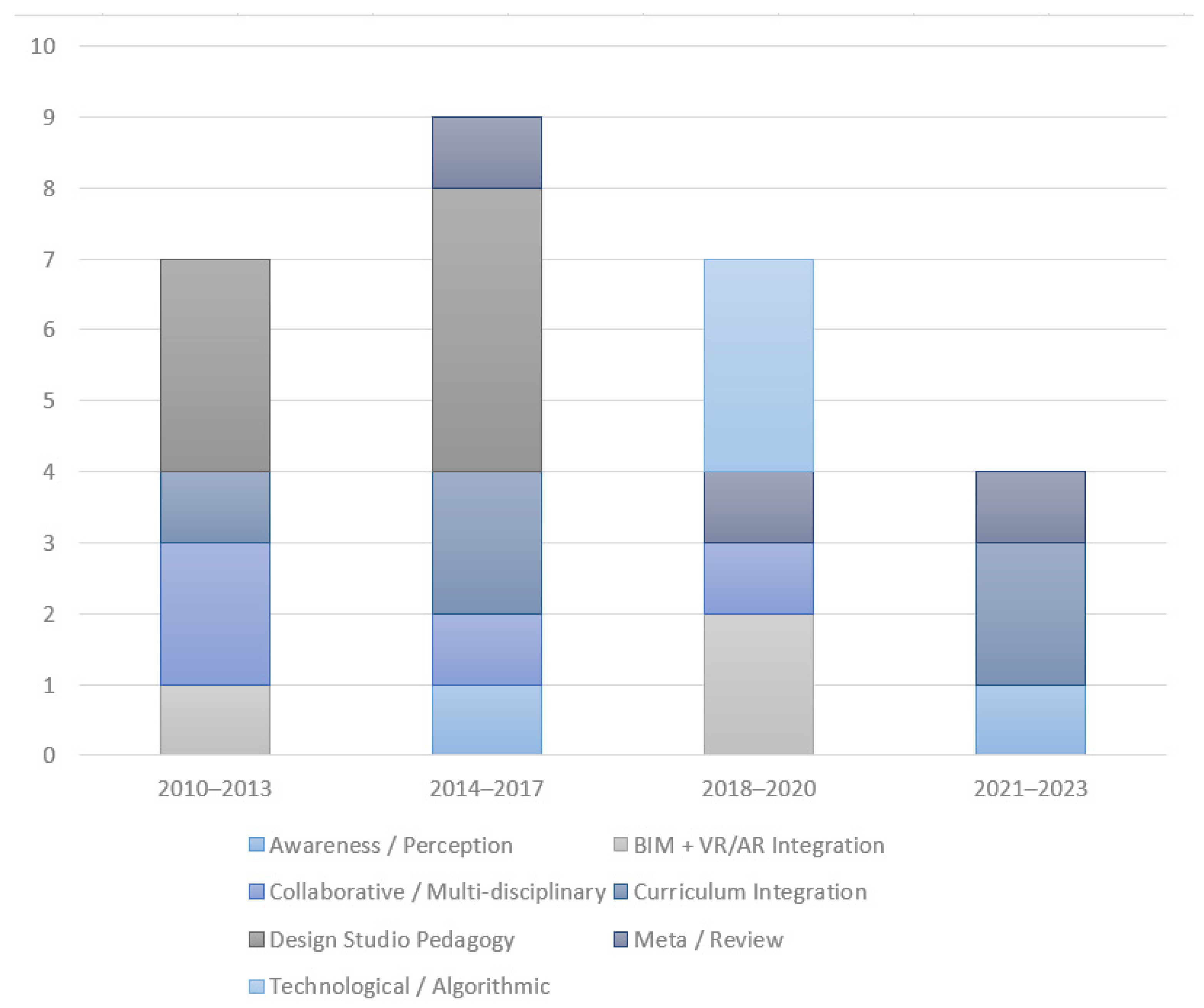

- Temporal Trends of BIM Education Research Education

- (2)

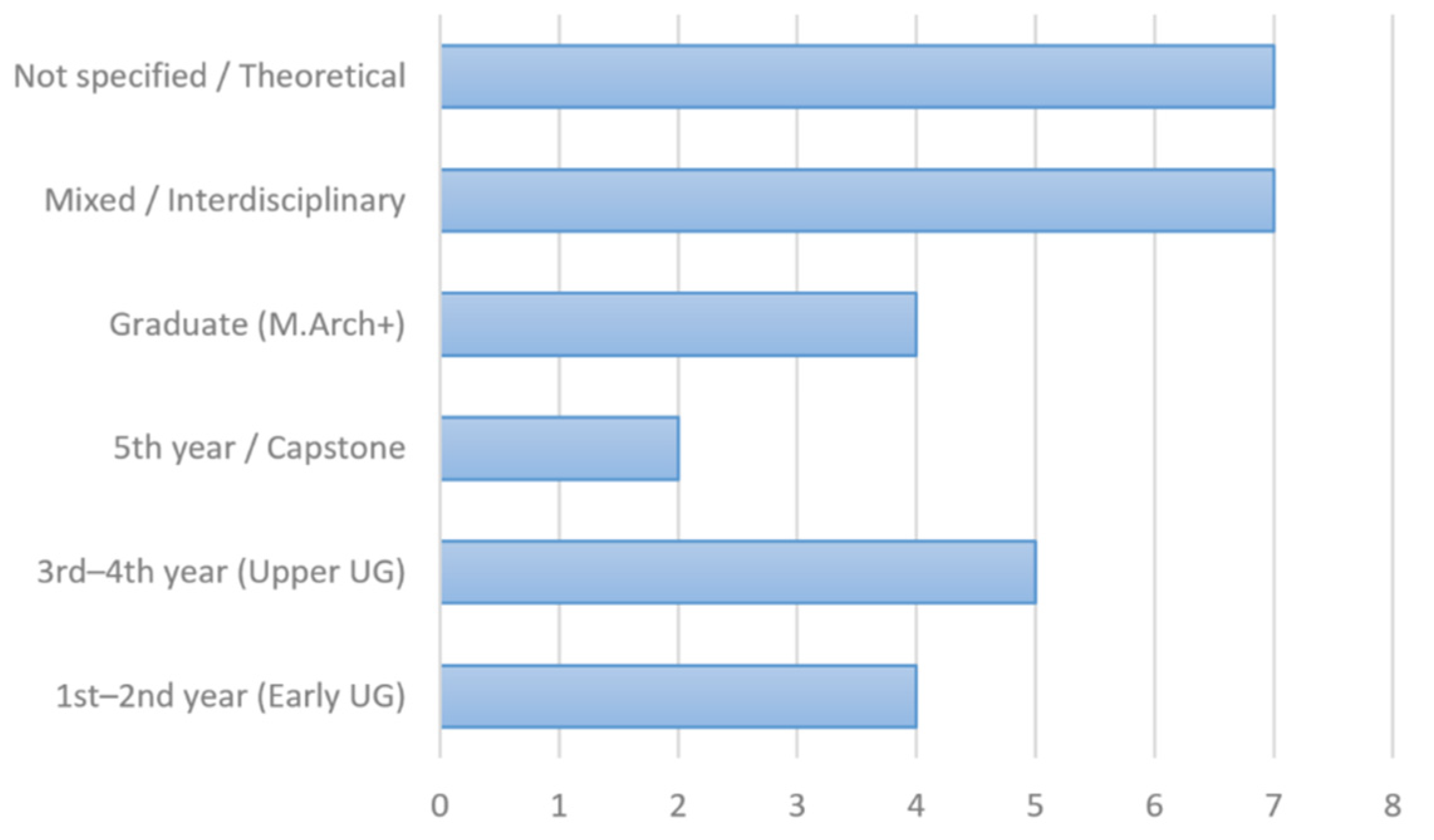

- Curriculum-Level Distribution

- (3)

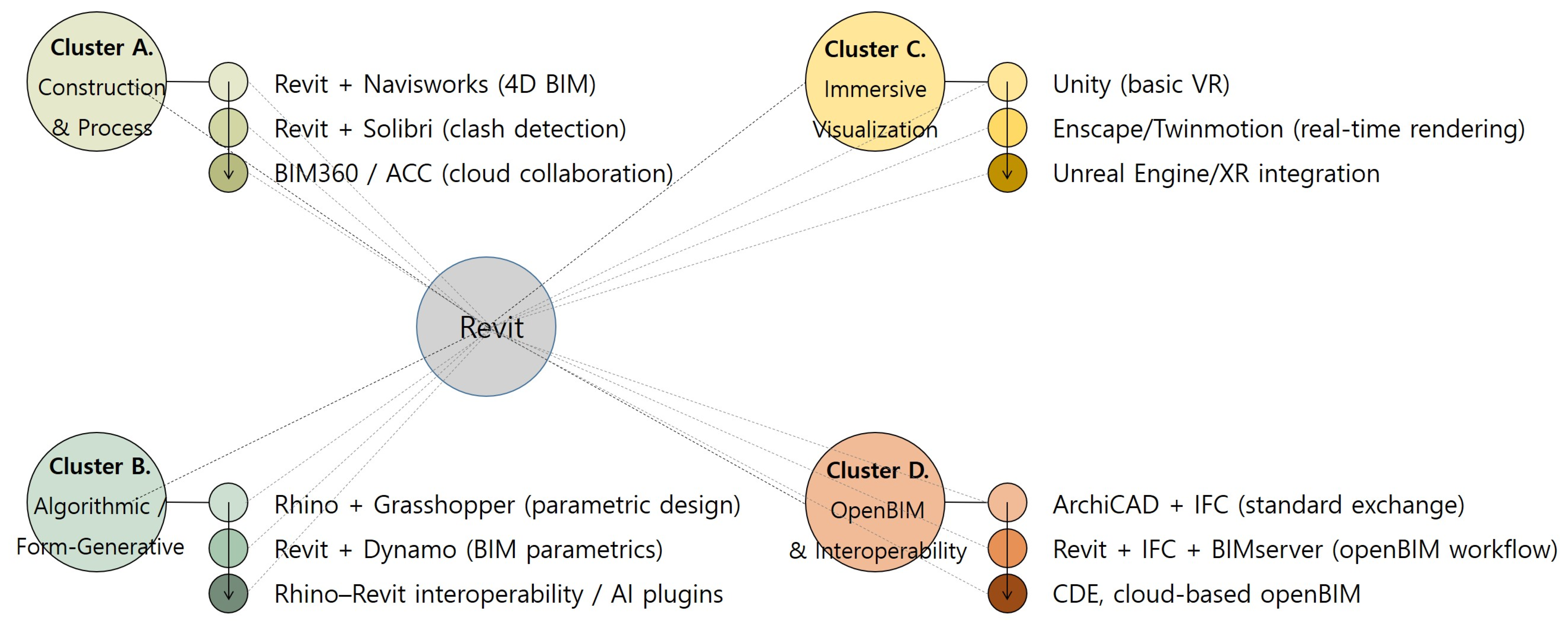

- Software and Technological Trends

3.2. Integration Pathways of BIM Education

- (1)

- Levels of BIM Integration

- (2)

- Interdisciplinary and Professional Linkages

3.3. Challenges, Strategies, and Debates in BIM

- (1)

- Emerging Educational Challenges and Corresponding Strategies

- (2)

- Divergent Views and Ongoing Debates in BIM Education Research

3.4. Global Trends in BIM Education Research

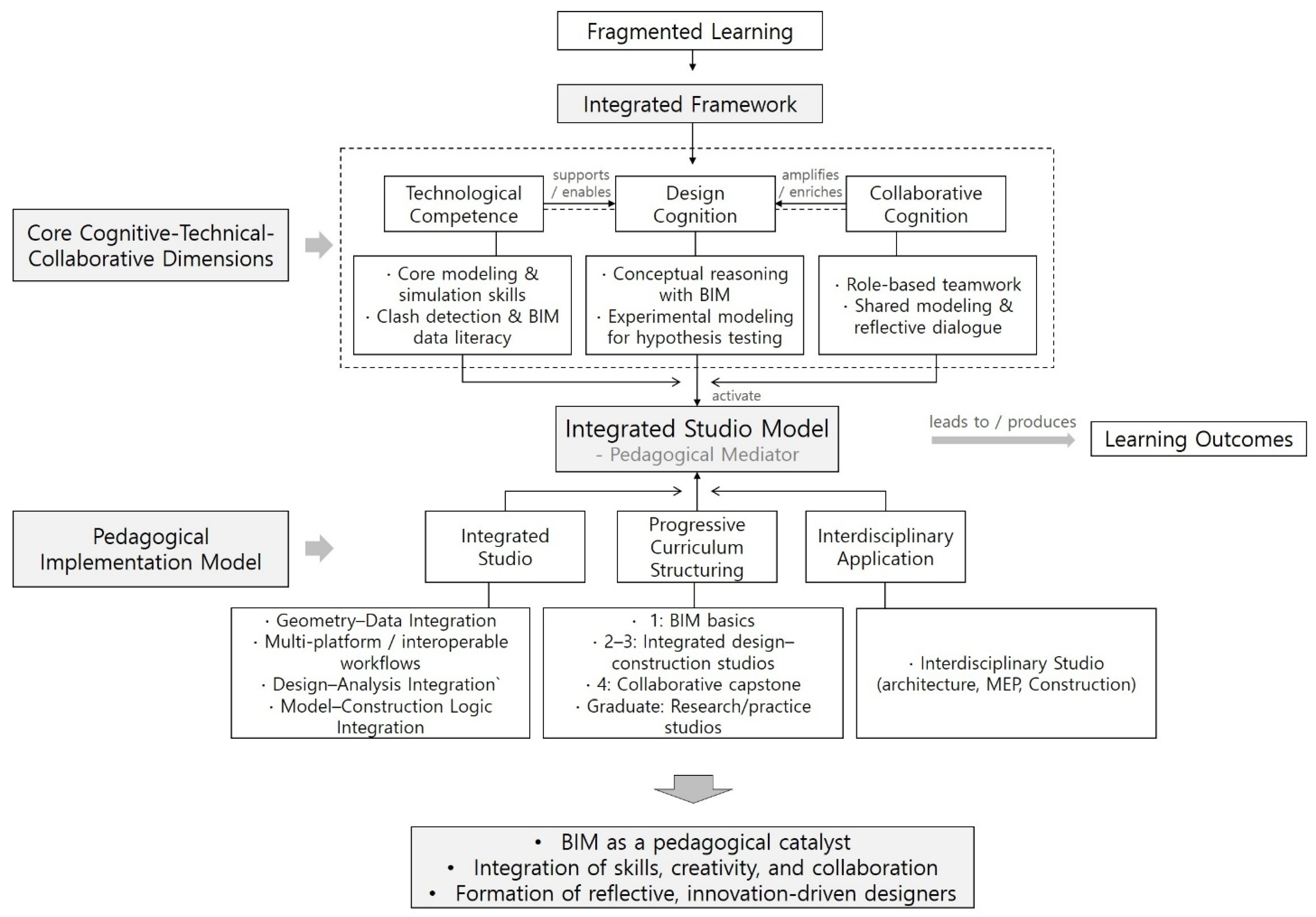

4. Discussion- Analytical Interpretation and Synthesis

4.1. Pedagogical Implications and Curriculum Integration of BIM Education

4.2. Regional and Institutional Reflections

4.3. Toward an Integrated Educational Framework

- Diagnose students’ initial levels of technological and cognitive competence to differentiate roles and learning pathways within the studio;

- Structure studios to ensure cyclical integration of design, analysis, and collaboration;

- Employ team-based projects and shared modeling processes to enable the simultaneous development of technological, cognitive, and collaborative capacities; and

- Evaluate integrated learning outcomes through portfolios, reflective documentation, and collective deliverables.

- These guidelines provide a practical foundation through which the conceptual structure of the framework can be enacted within real educational settings.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Azhar, S. Building information modeling (BIM): Trends, benefits, risks, and challenges for the AEC industry. Leadersh. Manag. Eng. 2011, 11, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, C.M.; Teicholz, P.; Sacks, R.; Liston, K. BIM Handbook: A Guide to Building Information Modeling for Owners, Managers, Designers, Engineers, and Contractors; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, N.; London, K. Understanding and facilitating BIM adoption in the AEC industry. Autom. Constr. 2010, 19, 988–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosrowshahi, F.; Arayici, Y. Roadmap for implementation of BIM in the UK construction industry. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2012, 19, 610–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.K.D.; Wong, F.K.W.; Nadeem, A. Building information modelling for tertiary construction education in Hong Kong. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2015, 20, 104–122. [Google Scholar]

- Succar, B.; Sher, W. A competency knowledge-base for BIM learning. Australas. J. Constr. Econ. Build.-Conf. Ser. 2014, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerik-Gerber, B.; Gerber, D.J.; Ku, K. The pace of technological innovation in architecture, engineering, and construction education: Integrating recent trends into the curricula. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2011, 16, 411–432. [Google Scholar]

- Barison, M.B.; Santos, E.T. BIM teaching strategies: An overview of the current approaches. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computing in Civil and Building Engineering (ICCCBE), Nottingham, UK, 30 June–2 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Clevenger, C.M.; Ozbek, M.E.; Glick, S.; Porter, D. Integrating BIM into construction management education. In Proceedings of the Associated Schools of Construction (ASC) 48th Annual International Conference, Birmingham, UK, 11–14 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chegu Badrinath, A.; Chang, Y.T.; Hsieh, S.H. A review of tertiary BIM education for advanced engineering communication with visualization. Vis. Eng. 2016, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, R.; Pikas, E. Building information modeling education for construction engineering and management. II: Procedures and implementation case study. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2013, 139, 04013016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, R.; Björk, B.C. Building information modelling—Experts’ views on standardisation and industry deployment. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2008, 22, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Succar, B.; Kassem, M. Macro-BIM adoption: Conceptual structures. Autom. Constr. 2015, 57, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Issa, R.R.A.; Olbina, S. Factors influencing the adoption of building information modeling in the AEC industry. Int. J. Constr. Educ. Res. 2017, 13, 283–301. [Google Scholar]

- Obi, L.I.; Omotayo, T.; Ekundayo, D.; Oyetunji, A.K. Enhancing BIM competencies of built environment undergraduates students using a problem-based learning and network analysis approach. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2024, 13, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerik-Gerber, A.A.; Burcin; Ku, K.; Jazizadeh, F. BIM-enabled virtual and collaborative construction engineering and management. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2012, 138, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdirad, H.; Dossick, C.S. BIM Curriculum Design in Architecture, Engineering, and Construction Education: A Systematic Review. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2016, 21, 250–271. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, N.; Dossick, C.S. Leveraging building information modeling technology in construction engineering and management education. In Proceedings of the 2012 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, San Antonio, TX, USA, 10–13 June 2012; pp. 25.898.1–25.898.15. [Google Scholar]

- Ku, K.; Taiebat, M. BIM experiences and expectations: The constructors’ perspective. Int. J. Constr. Educ. Res. 2011, 7, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getuli, V.; Capone, P.; Bruttini, A.; Isaac, S. BIM-based immersive Virtual Reality for construction workspace planning: A safety-oriented approach. Autom. Constr. 2020, 114, 103160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham Van, B.; Wong, P.; Abbasnejad, B. A Systematic Review of Criteria Influencing the Integration of Bim and Immersive Technology in Building Projects. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2025, 30, 243–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlbacher, F. The use of qualitative content analysis in case study research. Forum Qual. Sozialforschung/Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2006, 7, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Shin, W.; Park, E.J. Implications of neuroarchitecture for the experience of the built environment: A scoping review. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2022, 16, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sharif, R.; Pokharel, S. Smart city dimensions and associated risks: Review of literature. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 77, 103542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, N.; Nitanai, R.; Manabe, R.; Murayama, A. A global-scale review of smart city practice and research focusing on residential neighbourhoods. Habitat Int. 2023, 142, 102963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering; Keele University: Newcastle-under-Lyme, UK; Durham University: Durham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kocaturk, T.; Kiviniemi, A. Challenges of Integrating BIM in Architectural Education. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Education and Research in Computer Aided Architectural Design in Europe, Delft, The Netherlands, 18–20 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Laovisutthichai, V.; Srihiran, K.; Lu, W. Towards Greater Integration of Building Information Modeling in the Architectural Design Curriculum: A Longitudinal Case Study. Ind. High. Educ. 2023, 37, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puolitaival, T.; Forsythe, P. Practical Challenges of BIM Education. Struct. Surv. 2016, 34, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, J.A. A Framework for Collaborative BIM Education Across the AEC Disciplines. In Proceedings of the 37th Annual Conference of the Australasian Universities Building Educators Association (AUBEA), Sydney, Australia, 4–6 July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Veloso de Souza, L.P.; Ponzio, A.P.; Bruscato, U.M.; Cattani, A. A-BIM: A New Challenge for Old Paradigms. In Proceedings of the eCAADe 37/SIGraDi 23 Joint Conference Proceedings, Porto, Portugal, 11–13 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nakapan, W. Challenge of Teaching BIM in the First Year of University: Problems Encountered and Typical Misconceptions to Avoid when Integrating BIM into an Architectural Design Curriculum. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference of the Association for Computer-Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia (CAADRIA 2015), Daegu, Republic of Korea, 20–22 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Matejovská, D.; Vinšová, I.; Jirat, M.; Achten, H. The Uptake of BIM: From BIM Teaching to BIM Usage in the Design Studio in the Bachelor Studies. In Proceedings of the eCAADe 35—Building Information Modelling, Rome, Italy, 20–22 September 2017; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, M.M. Thinking the BIM Way: Early Integration of Building Information Modelling in Education. In Proceedings of the eCAADe 32—Building Information Modelling, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 10–12 September 2014; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, M.J.; Ozener, O.; Haliburton, J.; Farias, F. Towards studio 21: Experiments in design education using BIM. In Proceedings of the 14th Congress of the Iberoamerican Society of Digital Graphics, Bogotá, Colombia, 17–19 November 2010; pp. 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Agirbas, A. Teaching Construction Sciences with the Integration of BIM to Undergraduate Architecture Students. Front. Archit. Res. 2020, 9, 940–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özener, O.O.z. Studio Education for Integrated Practice Using Building Information Modeling. Doctoral Dissertation, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrose, M.A.; Fry, K.M. Re:Thinking BIM in the Design Studio—Beyond Tools, Approaching Ways of Thinking. In Proceedings of the ASCAAD 2010 Conference Proceedings, Manama, Kingdom of Bahrain, 21–23 February 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hajirasouli, A.; Banihashemi, S.; Sanders, P.; Rahimian, F. BIM-enabled Virtual Reality (VR)-based Pedagogical Framework in Architectural Design Studios. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2024, 13, 1490–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, A.J.; de la Fuente, C.B.; Cuenca-Moyano, G.; Gutiérrez-Carrillo, L.; de la Hoz-Torres, M.L.; Martín-Morales, M.; Martínez-Aires, M.D.; Carrillo, M.M.; Nieto-Alvarez, R. Teaching Team for Digital Teaching and Transversal Coordination of the subjects of the Process Management Module of the Degree in Building. University of Granada. In Proceedings of the 1st Congress of Building and Technical Architecture Schools of Spain, Valencia, Spain, 17–18 November 2021; pp. 523–537. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.W.; Lee, Y.G. The Effects of Human Behavior Simulation on Architecture Major Students’ Fire Egress Planning. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2017, 17, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özener, O.Ö.; Farias, F.; Haliburton, J.; Clayton, M.J. Illuminating the Design: Incorporation of natural lighting analyses in the design studio using BIM. In Proceedings of the FUTURE CITIES—28th eCAADe Conference Proceedings, Zurich, Switzerland, 15–18 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Boeykens, S.; De Somer, P.; Klein, R.; Saey, R. Experiencing BIM Collaboration in Education. In Proceedings of the Computation and Performance—Proceedings of the 31st eCAADe Conference, Delft, The Netherlands, 18–20 September 2013; pp. 505–514. [Google Scholar]

- Hemmerling, M.; Maris, S. INTERCOM: A Platform for Collaborative Design Processes. In Proceedings of the eCAADe 38—Education and Digital Theory, Virtual, 16–17 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.; Gu, N.; Wang, X. A Theoretical Framework of a BIM-based Multi-disciplinary Collaboration Platform. Autom. Constr. 2011, 20, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundfør, I.; Selvær, H. BIM as a Transformer of Processes. In Proceedings of the CAADence in Architecture Conference, Budapest, Hungary, 16–17 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Özener, O.Ö.; Jeong, W.; Haliburton, J.; Clayton, M.J. Utilizing 4D BIM Models in the Early Stages of Design. In Proceedings of the eCAADe 28—CAAD Curriculum, Zurich, Switzerland, 15–18 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, E.; Kim, M. BIM Awareness and Acceptance by Architecture Students in Asia. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2016, 15, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde Cantero, D. BIM as a Teaching Tool in Building Engineering Degree. In Proceedings of the EDIFICATE 2021 Conference Proceedings, Valencia, Spain, 4–5 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Y.; Kim, H.; Kim, N. Virtual Plan–Design–Build for Capstone Projects in the School of Architecture: CM & BIM Studios in Five-Year B.Arch. Program. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2016, 15, 279–286. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano, I.; Leitão, A. Integration of an Algorithmic BIM Approach in a Traditional Architecture Studio. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2019, 6, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, R.; Dean, W. Comprehensive BIM integration for architectural education using computational design visual programming environments. Build. Technol. Educ. Soc. 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, J.; McArthur, J.J. Data-Driven Design as a Vehicle for BIM and Sustainability Education. Buildings 2019, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamu, Z.A.; Thorpe, T. How universities are teaching BIM: A review and case study from the UK. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2016, 21, 119–139. [Google Scholar]

- García-Alvarado, R.; Forcael Durán, E.; Pulido-Arcas, J.A. Evaluation of Extreme Collaboration with BIM Modeling for the Teaching of Building Projects. Arquitetura Rev. 2020, 16, 137. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Rodríguez, M.; Álvarez-Arce, R. Drawing through a Screen: Teaching Architecture in a Digital World. In Proceedings of the JIDA’21—IX Jornadas Sobre Innovación Docente en Arquitectura, Valladolid, Spain, 11–12 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, J. Teaching for Quality Learning at University, 2nd ed.; Open University Press: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, P.; Koehler, M.J. Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2006, 108, 1017–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, E.; Kähkönen, K. BIM-enabled education: A systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the 10th Nordic Conference on Construction Economics and Organization, Tallinn, Estonia, 7–8 May 2019; pp. 261–269. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, K.G. Integrating VR-enabled BIM in building design studios, architectural engineering program, UAEU: A pilot study. In Proceedings of the 2020 Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences (ASET), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 4 February–9 April 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Author | Paper Title | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Curriculum Integration Studies | [29] | Challenges of Integrating BIM in Architectural Education | 2013 |

| [30] | Towards Greater Integration of BIM in the Architectural Design Curriculum: A Longitudinal Case Study | 2023 | |

| [31] | Practical Challenges of BIM Education | 2016 | |

| [32] | A Framework for Collaborative BIM Education Across the AEC Disciplines | 2012 | |

| 2. BIM in Design Studio Pedagogy | [33] | A-BIM: A New Challenge for Old Paradigms | 2019 |

| [34] | Challenge of Teaching BIM in the First Year of University | 2015 | |

| [35] | The Uptake of BIM: From BIM Teaching to BIM Usage in the Design Studio in the Bachelor Studies | 2017 | |

| [36] | Thinking the BIM Way: Early Integration of Building Information Modeling in Education | 2014 | |

| [37] | Towards studio 21: Experiments in design education using BIM | 2010 | |

| [38] | Teaching Construction Sciences with the Integration of BIM to Undergraduate Architecture Students | 2020 | |

| [39] | Studio Education for Integrated Practice Using BIM | 2010 | |

| [40] | Re: Thinking BIM in the Design Studio—Beyond Tools, Approaching Ways of Thinking | 2010 | |

| 3. BIM + VR/AR/Simulation Integration | [41] | BIM-enabled VR-based Pedagogical Framework in Architectural Design Studios | 2020 |

| [42] | Teaching Team for Digital Teaching and Transversal Coordination of the subjects of the Process Management Module of the Degree in Building. University of Granada | 2021 | |

| [43] | The Effects of Human Behavior Simulation on Architecture Major Students’ Fire Egress Planning | 2018 | |

| [44] | Illuminating the Design: Incorporation of Natural Lighting Analyses in the Design Studio Using BIM | 2010 | |

| 4. Collaborative/Interdisciplinary Learning | [45] | Experiencing BIM Collaboration in Education | 2013 |

| [46] | INTERCOM—A Platform for Collaborative Design Processes | 2020 | |

| [47] | A Theoretical Framework of a BIM-based Multi-disciplinary Collaboration Platform | 2011 | |

| [48] | BIM as a Transformer of Processes | 2016 | |

| [49] | Utilizing 4D BIM Models in the Early Stages of Design | 2010 | |

| 5. Awareness/Perception Studies | [50] | BIM Awareness and Acceptance by Architecture Students in Asia | 2016 |

| [51] | BIM as a Teaching Tool in Building Engineering Degree | 2021 | |

| [52] | Virtual Plan–Design–Build for Capstone Projects in the School of Architecture: CM & BIM Studios in Five-Year B.Arch. Program | 2016 | |

| 6. Technological/Algorithmic Approaches | [53] | Integration of an Algorithmic BIM Approach in a Traditional Architecture Studio | 2019 |

| [54] | Comprehensive BIM Integration for Architectural Education—Using Computational Design Visual Programming Environments | 2019 | |

| [55] | Data-Driven Design as a Vehicle for BIM and Sustainability Education | 2019 | |

| 7. Meta/Review/Comparative Studies | [17] | BIM Curriculum Design in Architecture, Engineering, and Construction Education: A Systematic Review | 2016 |

| [56] | How Universities Are Teaching BIM: A Review and Case Study from the UK | 2016 | |

| [57] | Evaluation of Extreme Collaboration with BIM for the Teaching of Building Projects | 2020 | |

| [58] | Drawing through a Screen: Teaching Architecture in a Digital World | 2021 |

| Period | Dominant Themes and Research Focus |

|---|---|

| 2010–2013 |

|

| 2014–2017 |

|

| 2018–2020 |

|

| 2021–2025 |

|

| Cluster | 2010–2014 (Early) | 2015–2019 (Mid) | 2020–2023 (Recent) | Trend Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Construction & Process | Revit + Navisworks (4D BIM) | Revit + Solibri (clash detection) | BIM360/ACC (cloud collaboration) | Process-based BIM shifts to cloud-based collaboration |

| B. Algorithmic/Form-Generative | Rhino + Grasshopper (parametric design) | Revit + Dynamo (BIM parametrics) | Rhino–Revit interoperability/AI plugins | Expansion from form generation → computational logic integration |

| C. Immersive Visualization | Unity (basic VR) | Enscape/Twinmotion (real-time rendering) | Unreal Engine/XR integration | From visualization → experiential learning |

| D. OpenBIM & Interoperability | ArchiCAD + IFC (standard exchange) | Revit + IFC + BIMserver (openBIM workflow) | CDE, cloud-based openBIM | From file exchange → integrated open collaboration |

| Integration Level | Definition | Typical Educational Features |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1—Tool-based | BIM introduced as a software skill or drafting substitute | Focus on Revit/ArchiCAD tutorials; limited integration with design process |

| Level 2—Process-based | BIM used for coordination, workflow, or collaboration | Revit + Navisworks or Solibri used in project management or teamwork assignments |

| Level 3—Design-thinking Integration | BIM embedded into conceptual or algorithmic design process | Rhino/Grasshopper + Dynamo; BIM as cognitive design tool |

| Level 4—Curriculum-level Integration | BIM institutionalized across courses and disciplines | Multi-course or cross-departmental integration; OpenBIM frameworks |

| Category | Linkage Type | Main Focus | Educational Context | Pedagogical Role of BIM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interdisciplinary Linkages | Design–Construction Linkage | Integration of design studios with construction management courses | Collaborative studio using shared Revit/IFC models | Supports coordination and constructability understanding |

| Design–Digital Fabrication Linkage | Connection between computational design and digital fabrication | Rhino–Grasshopper–Revit integrated workflows | Enhances algorithmic thinking and fabrication logic | |

| Design–Management Linkage | Bridging project management and design courses | BIM-based planning and scheduling within studio context | Encourages data-driven decision-making | |

| Professional Linkages | Academic–Industry Collaboration | Joint projects between universities and industry partners | IPD/openBIM-based collaborative assignments | Provides real-world coordination experience |

| Expert-Involved Education | Participation of practitioners in studio teaching or reviews | Professional advisory or co-teaching sessions | Develops professional judgment and workflow literacy | |

| Technology-Integrated Curriculum | Incorporation of industry technologies (VR/AR, cloud BIM) | Practice-oriented curriculum reflecting industrial standards | Reinforces technological fluency and industry relevance |

| Category | Key Challenges Identified | Corresponding Educational Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Pedagogical and Curricular Challenges | ∙ Fragmented and tool-oriented instruction ∙ Lack of curricular integration across studio and construction courses ∙ Overemphasis on software over process and collaboration ∙ Limited accreditation and assessment frameworks for BIM learning | ∙ Integrate BIM progressively through curriculum (introductory → advanced stages) ∙ Combine standalone and embedded modules ∙ Link BIM with design studio pedagogy and sustainability ∙ Develop outcome-based rubrics and cross-course coordination |

| 2. Cognitive and Conceptual Challenges | ∙ Students struggle to shift from 2D abstraction to 3D object-based reasoning ∙ High initial cognitive load and steep learning curve ∙ Misunderstanding BIM as software rather than a design methodology | ∙ Scaffold BIM learning via conceptual visualization before tool training ∙ Promote “thinking the BIM way” and object-oriented cognition ∙ Introduce reflective design journals and visualization exercises ∙ Employ comparative learning (CAD → BIM transition projects) |

| 3. Technical and Interoperability Challenges | ∙ Software incompatibility and limited IFC interoperability ∙ Lack of standard workflows across disciplines ∙ Inconsistent modeling practices and data exchange difficulties | ∙ Implement openBIM and IFC-based collaboration exercises ∙ Use cloud-based CDE platforms ∙ Develop technical literacy for data management and version control ∙ Provide hands-on troubleshooting sessions and peer tutoring |

| 4. Institutional and Resource Barriers | ∙ Limited faculty expertise and resistance to pedagogical change ∙ Insufficient infrastructure, licensing, and maintenance support ∙ Time constraints within traditional curricula | ∙ Establish faculty training and industry partnerships ∙ Use cross-institutional teaching collaborations ∙ Integrate BIM within accreditation criteria and learning outcomes ∙ Develop shared repositories and digital platforms |

| 5. Collaborative and Interdisciplinary Challenges | ∙ Persistent disciplinary silos between architecture, engineering, and construction programs ∙ Lack of communication and coordination skills ∙ Insufficient exposure to real-world team workflows | ∙ Interdisciplinary design studios and collaborative projects ∙ Role-based learning simulating IPD environments ∙ Integration of virtual and cloud-based collaboration ∙ Reflection on teamwork, leadership, and BIM management roles |

| Theme/Debate | Contrasting Perspectives | Recent Consensus/Trend |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Nature of BIM in Education | Tool-based approach: Focus on software operation and modeling proficiency. | Gradual shift toward BIM Thinking emphasizing cognitive and collaborative processes rather than tool mastery. |

| Process-/Thinking-based approach: BIM as a design cognition and collaborative reasoning framework. | ||

| 2. Timing of Integration in Curriculum | Early integration: Introduce BIM concepts in the first year to shape design thinking. | Increasing support for early spiral integration, yet optimal timing depends on faculty expertise and curricular load. |

| Late integration: Introduce BIM after foundational design skills are formed. | ||

| 3. Collaboration Model | OpenBIM / Cloud-based model: Emphasizes real-time sharing, transparency, and open data formats. | Mixed practice: open workflows for learning engagement, controlled protocols for accountability and quality. |

| Controlled CDE model: Focuses on role definition, version control, and managed workflows. | ||

| 4. Industry Linkage and Pedagogical Autonomy | Practice-driven view: Strengthen industry relevance, capstone mentorship, and professional readiness. | Balanced models combining live briefs and reflective academic inquiry are increasingly adopted. |

| Academic-driven view: Preserve exploratory and critical design learning independent of industry constraints. | ||

| 5. Policy and Regional Contexts | Top-down policy-driven adoption: e.g., government BIM mandates in Korea or Singapore accelerate curricular change. | Regional divergence remains; both pathways contribute to diffusion depending on institutional readiness. |

| Bottom-up academic initiatives: e.g., voluntary integration in Belgium or Chile driven by educators. | ||

| 6. Assessment and Accreditation | Drawing-/output-based evaluation: Focus on deliverables and visual quality. | Trend toward information-centric rubrics aligning learning outcomes with professional BIM competencies. |

| Information- and process-based evaluation: Emphasizes data quality, coordination, and decision traceability. |

| Category | Countries | Core Characteristics | Summary of Research Tendencies |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Early Theoretical Orientation | USA, UK | BIM as a cognitive and collaborative framework rather than a digital tool | Focused on theoretical foundations and pedagogical redefinition of BIM as a new design paradigm. |

| 2. Practice-Integrated Education | South Korea, Australia, New Zealand | Integration of design–construction–operation; capstone and industry-linked education | Emphasized practice-oriented learning and collaboration between academia and industry. |

| 3. Digital Convergence Education | Spain, Chile, Portugal, Brazil | BIM + VR, data-driven design, immersive learning | Highlighted post-COVID pedagogical innovation through digital and immersive technologies. |

| 4. Collaborative Platform Research | Germany, Norway, Czech Republic | Cloud-based collaboration, data interoperability | Explored BIM as a collaborative and data-sharing platform in educational contexts. |

| 5. Early BIM Education and Awareness | Thailand, UAE, China/Hong Kong | Early-stage integration of BIM literacy and cognitive understanding | Aimed to cultivate BIM thinking and digital literacy from the first year of study. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shin, Y.-j.; Kang, E. From Tool-Based Training to Integrated Studios: A Review of BIM Education in Architecture. Buildings 2026, 16, 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010166

Shin Y-j, Kang E. From Tool-Based Training to Integrated Studios: A Review of BIM Education in Architecture. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):166. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010166

Chicago/Turabian StyleShin, Yoon-jeong, and Eunki Kang. 2026. "From Tool-Based Training to Integrated Studios: A Review of BIM Education in Architecture" Buildings 16, no. 1: 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010166

APA StyleShin, Y.-j., & Kang, E. (2026). From Tool-Based Training to Integrated Studios: A Review of BIM Education in Architecture. Buildings, 16(1), 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010166