1. Introduction

Over the past century, urbanisation has transformed global settlement patterns. While only 15% of the population lived in cities in 1900, the World Bank reported that 55% were urban residents by 2018, and projections suggest that two-thirds will live in cities by 2050 [

1]. This expansion has generated significant challenges, including urban sprawl, housing unaffordability, weak urban governance, rising inequality, and environmental degradation [

2]. This global trend has significantly heightened the demand for residential housing, particularly affecting young families’ access to suitable and affordable housing options [

3]. These challenges are most evident in rapidly growing cities, such as Riyadh, where housing preferences, family needs, and market realities interconnect to create complexities for multifamily housing markets and policymakers [

4].

The UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 11 underscores the need for inclusive, safe, and affordable housing by 2030, urging governments to align urban growth with social equity and sustainability targets [

5]. Target 11.1 emphasizes the importance of equitable and affordable housing with access to essential services for all individuals by 2030. Many governments worldwide, including the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, recognize the significance of housing and are allocating substantial portions of their gross domestic product to improve access to affordable and high-quality housing [

6,

7]. Despite these initiatives, affordability barriers and inadequate housing options remain significant challenges, particularly in cities experiencing rapid demographic and economic growth.

Saudi Arabia’s population increased from 7 million in 1974 to over 35 million in 2024 [

8], with urbanisation at around 85% in 2024 [

9]. Unlike many countries facing the challenges of ageing populations, Saudi Arabia is characterised by a distinctly youthful demographic with over half of its citizens under the age of 25 [

7]. This demographic surge, combined with rising incomes and limited supply, has produced an estimated shortage of more than one million housing units [

6]. Despite government initiatives and financial incentives, home-ownership rates remain low among middle- and low-income groups [

10,

11]. The combination of these factors, together with low homeownership rates, has created a severe housing affordability problem which affects middle- and low-income families the most. According to a recent report by Knight Frank [

12], apartment prices in Riyadh have increased by 75% between 2019 and 2024.

The solution to these problems requires comprehensive policies which support different household sizes and young family requirements [

6,

13]. Young families now represent a crucial population segment globally, and this largely determines the housing demand in the country [

14,

15]. Today’s cities require multifamily housing, especially apartments, as these provide an efficient way to use land and infrastructure while serving diverse residents. However, the extent to which these housing options adequately meet the specific needs of young families remains largely unexplored.

In this study, the term young families is used in an inclusive sense to reflect the demographic transitions occurring in Riyadh, where delayed marriage, rising singlehood, and extended periods of renting increasingly shape early housing trajectories. Accordingly, the target population was defined as adults aged 20–49 who either rent or own their first home, encompassing married couples with children, couples without children, and single adults forming independent households. While married households with children represent the traditional core of “family” housing demand, emerging literature in Saudi Arabia indicates that single earners and newly formed households increasingly contribute to pressures in the multifamily sector. The study therefore adopts a functional rather than strictly demographic definition of young families, recognising that all these household types engage in family formation processes and face similar affordability constraints in early adulthood.

Young families typically seek affordable dwellings that provide privacy, safety, and access to essential services. However, studies indicate that prevailing apartment designs often fail to meet these expectations, such as in Australia [

16] and Saudi Arabia [

11,

17]. Studies from Northern Europe show that cultural values, household size, and socioeconomic constraints work together to shape preferences [

18,

19]. The case of Riyadh is a clear example of this tension, where rapid urban growth collides with traditional expectations of space and family life. Although multifamily housing options are increasingly available, questions persist regarding whether these options align with the needs and aspirations of young families.

Although Saudi housing research has examined affordability and ownership more broadly, young families remain an underrepresented group in empirical studies, despite being central to the country’s long-term demographic and economic transformation. Their housing experiences are particularly relevant to Saudi Vision 2030 [

7], which seeks to raise homeownership among citizens, especially young families, while diversifying urban housing types. Yet few studies have explored how this demographic navigates the combined pressures of affordability, cultural expectations, and evolving urban lifestyles. By focusing on young families in Riyadh, this study addresses a clear gap in the national housing policy literature and provides evidence directly aligned with Saudi Vision 2030’s housing and livability targets.

Therefore, this study aims to achieve three specific research objectives that address the identified gaps in the understanding of family-oriented multifamily housing in Riyadh. First, it identifies and analyses the socioeconomic determinants that shape affordability perceptions and ownership intentions among young families in Riyadh. Second, it examines how young families perceive and prioritise key building and neighborhood attributes that influence residential satisfaction. Third, it investigates the barriers that constrain sustainable multifamily living for young families. These objectives address the limited empirical evidence on how young households navigate affordability pressures, evaluate apartment suitability, and experience the constraints of multifamily housing in the Saudi context.

Based on the literature and the theoretical expectations concerning housing behaviour in rapidly growing cities, the study draws from these objectives and advances three testable hypotheses: H1 posits that higher income, mortgage accessibility, and favourable price-income suitability positively predict both perceived affordability and homeownership intention. H2 proposes that smaller household size is associated with higher affordability perception and a greater likelihood of intending to buy an apartment. H3 posits that dissatisfaction with building management, privacy, maintenance, and shared facilities function as barriers to satisfactory and sustainable multifamily living among young families. These research objectives and hypotheses structure the empirical strategy and link the study’s conceptual rationale to its analytical design.

This framework provides an empirical foundation for formulating policy recommendations that advance affordable, inclusive, and culturally appropriate housing solutions within the rapidly urbanising contexts of the Middle East, while also offering broader comparative relevance for global housing research. This study also provides actionable insights for policymakers, developers, and urban planners to create sustainable and family-friendly housing solutions in rapidly growing cities.

2. Literature Review

Housing preferences arise from the interplay between external, personal, and decision factors [

20]. External influences, such as policy frameworks, market dynamics, and regulatory environments, can shape affordability and availability [

21,

22]. At the same time, personal factors, such as cultural norms, household composition, income, and design preferences, can affect spatial needs [

23,

24]. Together, these aspects interact with decision factors that involve practical trade-offs, including cost, location, and dwelling type, that can directly determine housing choice. Furthermore, lifestyle is a strong predictor of residential satisfaction. Access to parks, schools, and healthcare enhances well-being [

25,

26,

27], while urban proximity reduces transport costs and commuter times [

28,

29]. Family-friendly design principles emphasize flexible layouts, communal areas, and safe play zones [

16,

30]. On the other hand, conventional high-density apartments often lack these features, leading to dissatisfaction [

31]. Collectively, these determinants highlight that housing preference is a multidimensional construct shaped by the interaction of structural conditions, individual characteristics, and lifestyle aspirations.

Unsurprisingly, affordability remains the most critical determinant of ownership [

32,

33], and rising house prices and restrictive credit conditions have intensified intergenerational inequalities [

4,

18]. Recent studies further confirm that the mismatch between household income levels and the escalating costs of market-supplied apartments has become a defining challenge in Saudi and regional housing markets [

25,

34,

35]. Alhajri [

25] attributes these difficulties to policy and planning frameworks that fail to balance land availability with household needs, while Alharbi [

35] observes that the COVID-19 pandemic intensified pre-existing shortages and cost pressures. International evidence further echoes these findings, with Kang et al. [

36] showing that high rental costs in metropolitan areas of the United States deter low-income renters, while Zhang et al. [

37] in China and Howell et al. [

38], also in the United States, document that rental growth routinely outpaces income gains, undermining financial stability. The broader socioeconomic dimension of this affordability crisis that links housing costs, displacement, and inequality has been highlighted in the European Union [

39], along with calls for coordinated policy interventions to close the widening price-to-income gap.

The process of moving from renting to owning a home creates special challenges for young families because of high costs and limited access to suitable housing [

32,

33,

40]. The lack of mortgage options and strict down payment requirements and rigid financing terms make it necessary for many families to seek help from their parents or extend their renting period. Research in Saudi Arabia shows that low-income homebuyers strongly want to own property (68%) but face obstacles from affordability and credit availability [

17,

41]. Also, 85% of Saudi citizens want to live in villas or duplexes because these housing types match their cultural values for privacy, family needs, and social standing [

6]. Personal elements, including cultural values and family dynamics, combined with personal choices about lifestyle, seem to create additional barriers which affect housing accessibility.

The literature increasingly recognises that spatial design affects community cohesion and inclusive designs, and community gardens promote interaction [

42,

43]. However, in many Middle Eastern settings, Western-inspired open-plan layouts conflict with local expectations for privacy, gender separation and extended-family living [

44]. Furthermore, the lack of communal facilities and functional shared indoor spaces weakens social sustainability and hinders community integration [

45]. Such deficiencies highlight the necessity for culturally adaptive building design that balances density with family well-being.

The literature also shows that the gap between what people want in housing and what the market provides continues to grow. Studies have exposed substantial differences between Saudi Arabian consumers and developers about essential housing features, which suggests the need for better communication and evidence-based urban planning [

11]. Recent Saudi literature on affordability grievances [

25,

34,

35] reinforces this concern, noting that policy responses have not kept pace with household expectations and demographic changes. Further afield, Cheng and Haan [

46] and Kulka et al. [

47] show that in North America, restrictive zoning and density limits in metropolitan areas suppress multifamily housing supply, while Tighe [

48] and Gabbe [

49] highlight that developer incentives and land-release mechanisms are central to moderating price escalation.

Housing markets around the world face similar challenges that do not match local cultural preferences and limit the development of multifamily housing, such as in Canada [

46] and the United States [

47,

48]. Research conducted in Turkey and Saudi Arabia showed that family-friendly features and adaptable floor plans and community involvement in design development led to better resident satisfaction and stronger community bonds [

50,

51]. The supply of affordable family-friendly housing remains restricted because of high construction expenses and restricted residential land availability and strict zoning regulations [

49,

52]. These findings suggest that housing affordability depends on design excellence and community health as well as financial accessibility.

Across the studies reviewed above, several common themes emerge that justify a more integrated interpretation of housing preferences and constraints. Taken together, these international and Saudi findings demonstrate that housing preferences are shaped by a combination of structural constraints, cultural expectations, and affordability pressures, and these dynamics appear particularly acute in rapidly urbanising contexts such as Riyadh. However, while the existing literature examines these dimensions individually, few studies consider how structural constraints, cultural expectations, and affordability pressures interact to shape multifamily housing outcomes. The literature suggests that potential homebuyers choose multifamily housing because of multiple factors which combine structural elements with personal needs and practical requirements. The combination of external policy factors with cultural values and household structures and individual life goals determines how affordable housing options are and how satisfied people are and whether they choose to become homeowners. The quality of design and availability of shared facilities between residents affect how people experience their living environment and sense of community connection. Nevertheless, few studies have examined these interactions specifically among young Saudi families, which this research directly addresses by integrating quantitative and qualitative evidence to reveal how affordability perceptions, cultural expectations, and governance issues shape the sustainability of multifamily housing in Riyadh.

The current literature on multifamily housing preferences, affordability, design, and social interactions has provided important insights to date. However, it lacks essential information about young families who live in cities experiencing rapid demographic and economic growth. Although several studies address affordability, design, or community factors in Saudi housing markets, none focus specifically on how these interact to influence young families’ experiences in multifamily settings. The absence of suitable housing solutions for young families in Riyadh requires research such as this study to conduct place-specific investigations which will help policymakers and planners create housing models that match the cultural and economic characteristics of young families in Riyadh and comparable urban areas.

3. Materials and Methods

This research used quantitative methods to study how young families in Riyadh choose their homes and view housing affordability. This was complemented with some qualitative analysis of written responses. The research focused on households containing adults between 20 and 49 years old who either owned their first home or rented. The online questionnaire reached a diverse group of Riyadh residents through various distribution channels from January to March 2024.

The questionnaire was administered using a non-probability sampling strategy that combined purposive and snowball/voluntary response methods. The purposive component involved distributing the survey link through the Ministry of Municipalities and Housing via the Ejar platform (Ministry of Municipalities and Housing, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia), which manages rental contracts, and the Mullak platform (Ministry of Municipalities and Housing, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia), which serves registered apartment owners and homeowners’ association members. This approach enabled direct access to tenants, prospective buyers, and existing owners relevant to the study population.

Additionally, the questionnaire reached additional young families and housing market participants through social media platforms including WhatsApp (Meta Platforms Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA), X (formerly Twitter) (X Corp., San Francisco, CA, USA) and Telegram (Telegram FZ-LLC, Dubai, United Arab Emirates). These channels were chosen because they serve as popular communication tools for Saudi Arabian users to connect with individuals seeking residential properties to buy or rent. The questionnaire reached property listing groups and apartment-buyer communities and homeownership discussion forums. This allowed for more diverse participants through multiple distribution channels and reached participants from various social classes and residential situations. This element of snowball and voluntary response sampling expanded participation but introduced the possibility of self-selection bias, as individuals with stronger housing concerns or more active engagement in the housing market may have been more inclined to respond. The questionnaire participants chose to participate voluntarily and received information about the academic research purposes and confidentiality, and no reward or compensation was offered. The research collected no personal data from participants and followed all necessary ethical guidelines for social science studies. To clarify, the questionnaire collected demographic and socioeconomic information such as age group, marital status, education level, household size, and income bracket; however, no personally identifiable information (e.g., names, contact details, national ID numbers, or addresses) was requested. This ensured full anonymity while still capturing the personal characteristics necessary for statistical analysis. The questionnaire received 651 responses, of which 639 were validated as complete responses.

While the final sample is diverse across income, tenure, education, and household characteristics, it is not statistically representative of all young families in Riyadh. For example, the sample includes a higher proportion of male respondents (67%), reflecting patterns of platform use and household decision-making roles in the region. These features of the sampling strategy limit the external validity of the findings and should be interpreted as providing insights into patterns and associations within a broad but non-random segment of the young family housing population rather than population-level estimates. Despite these limitations, the sampling strategy is appropriate for the study’s explanatory objectives, enabling the identification of key affordability constraints, housing preferences, and determinants of ownership intention among active participants in the Riyadh housing market.

Although the study focuses on young families, the sampling frame deliberately included a broad set of early-adulthood household types. Respondents aged 20–49 comprised married households with children, married couples without children, and single adults living independently. This decision reflects changing demographic patterns in Riyadh, where postponed marriage and rising individual household formation create overlapping housing needs during the family-formation period. Including single respondents therefore allows the analysis to capture the full range of early-stage housing preferences and constraints in the city’s multifamily sector. However, the resulting sample structure means that not all respondents represent traditional nuclear families, and this must be considered when interpreting the findings.

The questionnaire was designed on the basis of key themes identified in the literature review including affordability constraints, household and demographic characteristics, cultural expectations, design and spatial considerations, and neighbourhood-level factors, thus ensuring alignment with the study’s objectives and hypotheses. These themes informed the structure of the survey items used to examine socioeconomic determinants of affordability and homeownership intentions (H1 and H2), as well as perceptions of privacy, maintenance, management quality, and shared facilities relevant to residential satisfaction (H3).

For transparency, the final instrument comprised 17 closed-ended items organised into four sections. The first section captured demographic and household characteristics (age group, marital status, family size, education, income). The second examined the respondent’s housing situation and intentions, including current tenure, willingness to purchase an apartment, and perceived mortgage accessibility. The third section assessed the importance of building and neighbourhood attributes using five-point Likert scales covering layout, privacy, natural light, construction quality, security, and access to services. A final open-ended question invited respondents to describe the main challenges encountered in multifamily living.

After collection, the dataset underwent a systematic pre-processing stage to verify for accurate and complete data and maintain internal consistency. The imputation of missing values followed statistical rules which used modes for categorical data and medians for ordinal data. All responses about homeownership and affordability were checked to fix any inconsistencies that would disrupt data coherence.

The dataset contained categorical and ordinal qualitative data. Statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.4.2; R Core Team, Vienna, Austria) and Microsoft Excel 2019 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) which supported both data preprocessing and inferential testing procedures. The R software enabled the researcher to convert the subjective questionnaire responses into numerical data for quantitative analysis. The researcher encoded categorical variables through label-encoding, where “Own” received a value of 1 and “Rent” received a value of 2. Age group was coded into three categories: 20–29, 30–39, and 40–49 years, reflecting the target population for young families and ensuring consistent comparison across household types. The researcher then used the cleaned dataset to apply non-parametric and regression-based methods through alignment with the analytical framework. To analyze the relationships between socio-demographic characteristics, perceptual variables, and housing preferences, a combination of non-parametric and regression-based statistical techniques was used. These techniques were chosen for their suitability in analysing categorical and ordinal data obtained from questionnaire responses. Non-parametric tests such as the Chi-Square Test of Independence, Mann–Whitney U Test, Kruskal–Wallis H Test, and Spearman’s Rank Correlation were used to identify significant associations and differences between groups. Regression models were then applied to explore predictive relationships, with Binary Logistic Regression estimating homeownership intentions and Ordinal Logistic Regression assessing satisfaction outcomes across ranked variables.

Statistical Methods Used for Analysis

The evaluation of housing choices and affordability barriers for young families in Riyadh was conducted using multiple statistical procedures. These analytical methods enable researchers to study how different types of variables relate to each other and identify associations and forecast variables that affect housing selection. Each statistical approach is accompanied by the relevant mathematical formula and practical applications. The statistical procedures were selected to test the study’s hypotheses and ensure coherence between conceptual expectations and empirical analysis. In line with H1 and H2, the analyses assess whether income, mortgage accessibility, price-income suitability, and household size predict affordability perceptions and homeownership intention. Preliminary non-parametric tests (χ

2, Mann–Whitney U, and Kruskal–Wallis) examine categorical and ordinal group differences related to these hypotheses, while Spearman’s correlation evaluates monotonic relationships among preference and satisfaction variables. Binary logistic regression models directly test the predictive components of H1 and H2, identifying socioeconomic determinants of willingness to purchase an apartment. The ordinal logistic regression model evaluates H3 by analysing how building management quality, privacy, maintenance, and shared facilities relate to overall satisfaction with multifamily living. Together, these procedures provide a coherent, theory-led analytical framework. A comprehensive discussion for each then follows in the

Section 4. All tests used two-tailed significance at

p < 0.05. Model performance was assessed using Log-Likelihood, Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), and McFadden’s pseudo-R

2 values.

The Chi-Square test is used to determine whether there is a significant association between two categorical variables. Relationships were assessed between age group and willingness to buy an apartment, current residence type and preferred apartment location, and marital status and preference for a mixed-community setting.

where

number of rows and

number of columns.

A non-parametric test called the Mann–Whitney U test is used to assess the differences between two independent groups when the dependent variable is ordinal (ranked data). It examined variations in perception of mortgage availability between homeowners and renters.

The p-value is determined based on the distribution of , and if , the difference between groups is statistically significant.

A non-parametric technique for comparing three or more independent groups is the Kruskal–Wallis test. It ascertains if the ordinal data replies of many groups differ in a statistically significant way. This test analysed differences in importance of neighborhood selection factors between respondents and where they prefer to live in Riyadh.

- 4.

Spearman’s Rank Correlation ()

The degree and direction of the monotonic link between two ordinal variables are measured using Spearman’s correlation. It is a non-parametric substitute for the Pearson correlation. This method was used to examine correlations between the perceived importance of apartment layout and housing preferences.

The value of ranges from −1 to 1:

- 5.

Binary Logistic Regression

The likelihood of a binary result (Yes/No) based on independent factors is modeled by logistic regression. Binary logistic regression was used to predict whether a respondent considers buying an apartment based on factors such as appropriate price income level, financial obligations, and family size.

Probability of purchasing an apartment;

Predictor variables (e.g., income, family size, affordability perception);

Intercept;

Coefficients for predictors.

- 6.

Ordinal Logistic Regression

Ordinal logistic regression models ordinal outcomes (e.g., housing satisfaction: Low, Medium, High) based on independent variables. This statistical analysis can predict how perceptions of apartment affordability vary based on educational level, marital status, and family size.

Formula

For an ordinal variable with

categories, the cumulative logit model is:

where

Cumulative probability of response ;

Threshold parameter for response ;

Coefficients for predictors.

4. Results

Of 639 participants, 67% were male and 33% female. The dominant age group was 30–39 years (41%), followed by 20–29 years (33%) and 40–49 years (13%) (

Figure 1). These age-group categories correspond to those defined in the

Section 3. While the study adopts an inclusive definition of young families, the demographic composition of the sample reveals meaningful variation in household structure. Married respondents represent the majority (59%) and therefore approximate the traditional family unit for which multifamily housing is typically designed. However, the presence of single respondents (37%), divorced (4%) and couples without children provides insight into the broader cohort of early-adult households contributing to multifamily housing demand in Riyadh. In terms of education, over half held undergraduate degrees (55%), reflecting Riyadh’s educated young-family demographic (

Figure 2). This profile supports the study’s focus on emerging middle-class households facing affordability constraints.

A thorough analysis of housing choices, affordability, and ownership likelihood among young families in Riyadh was completed using a variety of statistical approaches. The combination of ordinal and categorical analysis provided insights to emerge into the major variables influencing housing decisions.

Figure 3 shows how respondents evaluated apartments through a five-point Likert scale which ranges from strongly disagree to strongly agree. This shows that affordability and financing issues continue to affect respondents while they want better designed apartments with additional features. Nearly half of respondents (46%) disagreed or strongly disagreed that apartment prices in Riyadh are affordable for young families. A similar proportion (45%) expressed concern about the limited availability of mortgage loans. Although 31% agreed that they could secure a mortgage, opinions were evenly divided. Apartment size preferences were mixed: about 40% considered small units (below 120 m

2) suitable for young families, whereas 46% remained neutral or disagreed. Views on community living were also split, with 47% considering multifamily neighborhoods appealing, yet over half were neutral or unfavourable toward apartment-complex living. Roughly 40% agreed that residential complexes foster social interaction, and 40% supported the suitability of current apartment designs, though 39% were undecided. Importantly, 68% of participants preferred full-service complexes with amenities such as gyms and cafes, revealing a strong desire for enhanced living environments despite widespread financial constraints. These initial patterns are consistent with H1, as respondents’ affordability concerns and perceptions of mortgage accessibility appear closely linked to their overall views on housing suitability.

Figure 4 shows how respondents rated ten apartment features in Riyadh, based on a five-point Likert scale (1 = “I don’t care”, 5 = “I care a lot”). The kernel density curves show the relative importance respondents assign to each feature. The most distinct peaks appear at the highest rating (5), indicating that participants clearly prioritise the features of number of rooms, quality of construction, security, underground parking, location and natural lighting when selecting apartments. Features such as building aesthetics and modern design also exhibit right-skewed distributions, suggesting that visual and stylistic qualities matter to a large proportion of buyers, but slightly less than spatial and structural considerations.

On the other hand, attributes like balcony/terrace, view, and building aesthetic show broader or flatter distributions, implying greater variability in personal preferences and showing that these amenities appeal strongly to some respondents but not so for others. Overall, the figure demonstrates that respondents’ preferences concentrate around functional and security-related features rather than luxury or environmental amenities. This suggests that apartment seekers in Riyadh tend to be practical, focusing on what their families need, what they can afford, and finding homes that are safe and well built.

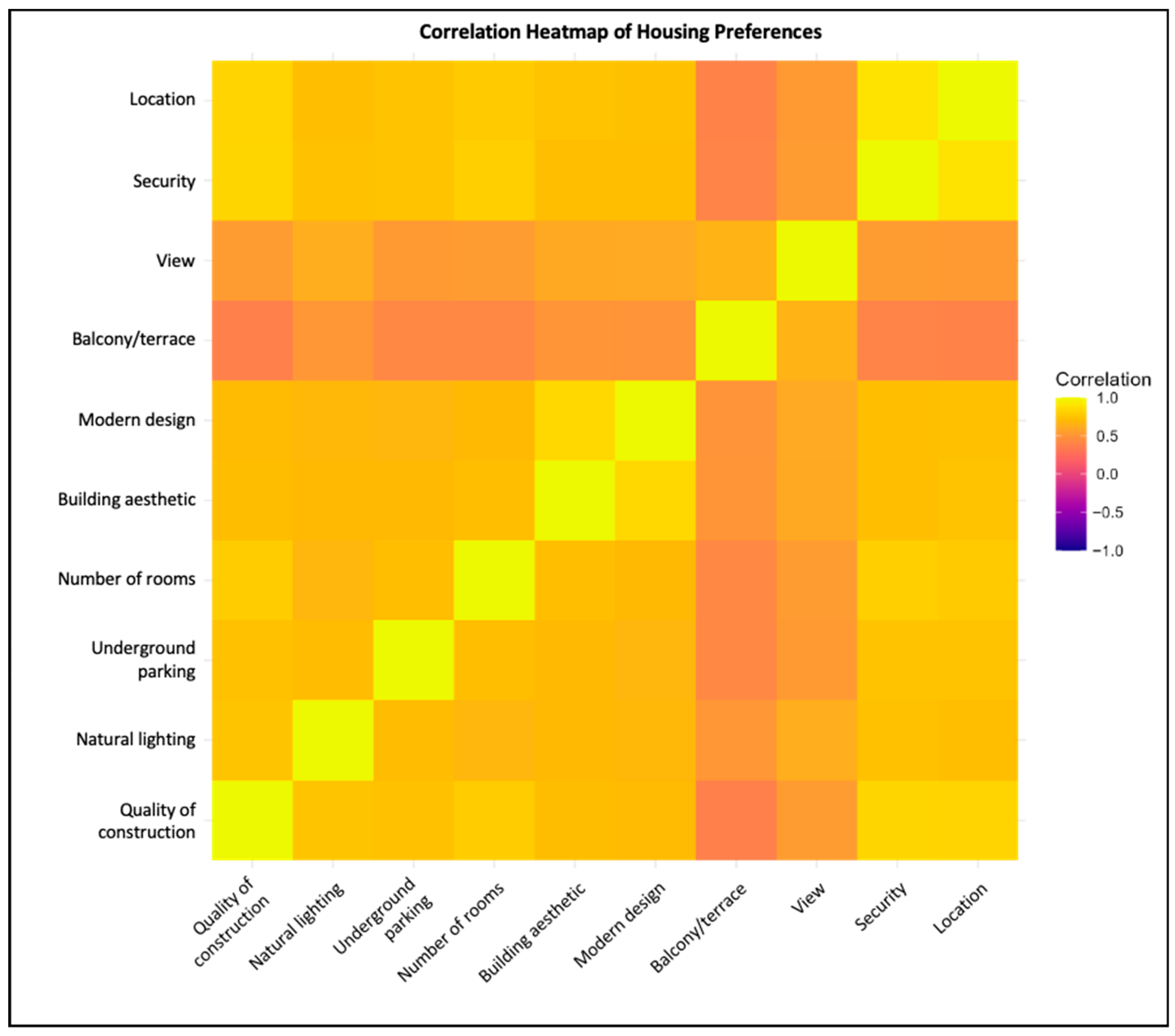

Spearman’s Rank Correlation analysis provides a visual representation of the correlation heatmap which displays how various housing preferences relate to each other (

Figure 5). Each relationship strength appears as color intensity where higher brightness indicates stronger connections. For example, respondents who value quality of construction in their housing decisions also highly value number of rooms, security and location. Interestingly, the correlation between security measures and residential locations demonstrate a positive relationship, suggesting that good neighborhood placement makes properties appear safer. On the other hand, numerous variables show weak associations, demonstrating that outdoor spaces (Balcony/terrace) contribute more negatively to overall house quality judgments. These findings demonstrate how architectural features and personal preferences affect homeowners’ selection of homes and could inform future residential architecture in Riyadh. While this analysis does not test H1 directly, the relationships between perceived quality, spatial needs, and security reinforce the broader role that economic expectations and purchasing capacity play in shaping residential evaluations, as expected in H1.

Although

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 present aggregate preference patterns, differences by household type were analysed elsewhere in the results. These variations are incorporated into the regression models that follow, which include household size and marital status as predictors. This approach allows us to quantify how affordability perceptions and residential preferences vary across family structures, even though the figures themselves report aggregated responses.

To further explore the relationships among key categorical variables, three Chi-Square tests of independence were conducted to determine whether demographic or behavioral factors significantly influenced housing-related preferences.

1. Age and apartment purchasing power: The analysis revealed a statistically significant association between respondents’ age group and their intention to purchase an apartment (χ2 = 20.04, p = 0.0005). Younger participants (aged 20–29) expressed lower readiness to buy, whereas older respondents (aged 40–49) were more inclined toward ownership. This likely reflects differences in financial stability and life stage.

2. Current residence type and preferred apartment location: No significant relationship was found between a respondent’s current type of residence and their preferred apartment location (χ2 = 14.25, p = 0.713). This suggests that location preferences are broadly shared across renters and homeowners, regardless of present housing tenure.

3. Marital status and preference for mixed communities: Similarly, no statistically significant link emerged between marital status and the preference for living in mixed-age or mixed-family communities (χ2 = 5.48, p = 0.706). Attitudes toward community composition therefore appear to transcend marital differences.

Overall, age exerts a meaningful influence on home-buying readiness, while current residence and marital status do not significantly shape preferences for apartment location or community mix. These findings suggest that affordability capacity, which is closely tied to age and economic maturity, remains the key factor driving apartment purchasing behavior in Riyadh. This pattern aligns with H2, which proposes that household characteristics, including family size, shape affordability evaluations and readiness to buy. The stronger purchasing readiness among older, more established households reflects differences in family size and income positioning as anticipated in H2.

This study used the Mann–Whitney U and Kruskal–Wallis tests to compare differences in questionnaire responses and identify variations in participants’ perceptions. The Mann–Whitney U Test analyzed whether homeowners and renters have different views about mortgage availability and the results indicate no significant difference between homeowners and renters as both groups view mortgage availability in Riyadh identically (W = 41040, p-value = 0.9178). The Kruskal–Wallis Test evaluated the importance levels of neighborhood selection variables according to where respondents wanted to live. The result (7.70, df = 6, p-value = 0.26) suggests that participants valued all neighborhood characteristics at relatively similar levels when selecting preferred areas in Riyadh.

This analysis used binary logistic regression, a statistical method that predicts the likelihood of one of two outcomes. In this case, whether a respondent intends to buy an apartment (Yes = 1, No = 0) based on several influencing factors. Three key predictors were tested: 1. Price relative to income. 2. Financial obligations. 3. Family size. The model summary is presented in

Table 1.

1. Price-Income Ratio: Measures respondents’ perceptions of how suitable apartment prices are relative to their family income. The relationship is positive but not statistically significant (β = 0.520, p = 0.307). Respondents who consider prices appropriate are more likely to intend to purchase than those who do not, however, this relationship is not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

2. Financial Obligations: Reflects whether respondents hold existing financial commitments. The effect is negligible (β = 0.006, p = 0.971), indicating that having other debts or payment obligations does not meaningfully influence ownership intentions.

3. Family Size: Captures the influence of household size. The coefficient is positive and statistically significant (β = 0.426, p = 0.047), suggesting that medium-sized families (4–5 members) are approximately 1.53 times more likely to intend to purchase an apartment than either very small or very large households.

Table 2 summarises how well the binary logistic regression model fits the data used to predict apartment-ownership intentions. The three methods of Log Likelihood, Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), and McFadden’s R

2 are standard measures of model performance. The Log Likelihood value of −424.097 indicates that the model fits the data moderately well but not strongly. The AIC score of 870.195 suggests the model could be improved by adding more relevant predictors. The model only accounts for 4.1% of the variation, according to McFadden’s

of 0.041, indicating that other factors, such as government housing policy, loan accessibility, and job stability, may have an impact on decisions to become homeowners. Financial commitments, family size, and acceptable pricing in relation to income level all contribute to the model, but their predictive potential seems to be limited, underscoring the need for other variables to strengthen the explanatory power.

The ordinal logistic regression model examines what factors influence how people perceive apartment affordability in Riyadh (

Table 3). The dependent variable is how affordable respondents think apartments are. The explanatory variables include education level (diploma, undergraduate, postgraduate); marital status (single, married, divorced); family size (2 and more than 5 persons); and perceived appropriate apartment purchase price based on family income (in Saudi Riyal, SAR). This type of regression was used because the dependent variable (perceived affordability) has ordered categories (e.g., very unaffordable, neutral, very affordable).

The analysis of education, marital status, family size and perceived purchase price revealed the following:

Education—No significant influence on affordability perceptions. The p-values for Diploma (p = 0.104), Undergraduate (p = 0.302), and Postgraduate (p = 0.281) are all above 0.05. This means education level does not meaningfully change how people judge apartment affordability.

Marital status—Statistically significant (p = 0.039). Married respondents perceive apartments as less affordable (negative coefficient = −0.389), whereas divorced respondents show a slightly more positive perception (positive coefficient = 0.663, p ≈ 0.10).

Family size—Mostly non-significant, but borderline effects appear. Families of three members tend to view apartments as more affordable (β = 0.506, p ≈ 0.12), while families with more than five members lean toward seeing them as less affordable (β = −0.504, p ≈ 0.05).

Perceived purchase price—The most influential predictor of perceived affordability was respondents’ expected apartment purchase price based on family income. Those selecting 500,001–750,000 SAR showed a significantly lower affordability perception (β = −0.847, p = 0.025), whereas participants identifying higher expected price categories (≥750,000 SAR) perceived apartments as increasingly affordable (β = 0.95, 2.33 and 3.86, all p < 0.05). This suggests that individuals whose affordability expectations align with higher market prices are more confident in their capacity to purchase, while those with lower price expectations experience the strongest affordability constraints.

Hence, these findings highlight that affordability perception in Riyadh’s multifamily housing market is primarily shaped by economic self-assessment (price-income expectations) and household structure (marital status and family size), rather than by formal education. This outcome highlights the interaction between socioeconomic status and household composition in explaining perceived housing accessibility among young families. These results provide partial support for H2 by showing that differences in household size and marital status contribute to variation in affordability perception, although smaller households do not necessarily rate affordability higher.

The open-ended question invited respondents to describe the main challenges they faced in owning an apartment. Of the 639 completed questionnaires, 247 participants (39%) provided written comments. Affordability clearly dominated these responses, with approximately 70% referring to the high cost of apartment units and the mismatch between household income and prevailing market prices. Respondents consistently noted that the “income of young families does not match with the price of apartments,” and described apartments as “prices too high” and “too expensive for average families.” Some participants explained that current market conditions discourage ownership altogether, remarking that “prices make a person not think about owning an apartment, especially since the option of owning an apartment is a temporary option until the opportunity to own a house becomes available.” Others emphasised the combined burden of financing, with one respondent stating, “the very high prices of apartment units plus banks interest rate are the biggest obstacle, especially for middle-income earners and small families.” These responses collectively confirm that price-income mismatch and mortgage inaccessibility represent the primary barriers to apartment ownership among young families in Riyadh.

Beyond affordability, respondents identified several additional challenges that shape their perceptions of apartment suitability. Design-related issues were frequently mentioned, with comments referring to “poor apartment designs” that lack functional spaces such as “maids and laundry rooms.” Concerns regarding cultural alignment were also prominent, particularly relating to privacy and noise, with respondents stating that “apartments lack privacy, especially for conservative families” and reporting “noise and disturbances from neighbors.” Construction quality emerged as another recurring theme, including remarks such as “quality of finishing is bad” and a general “lack of confidence in construction quality.” Issues of management and governance were raised as well, with respondents noting the “lack of activation of the role of owners’ associations in building management” and “poor maintenance of apartment facilities.” These concerns were succinctly captured by one participant who stated, “Most of the apartments in Riyadh lack the design that meets the privacy and lifestyle of the Saudi family.” These findings strongly support H3, demonstrating that dissatisfaction with design suitability, privacy, construction quality, and building management is closely associated with negative perceptions of multifamily living among young families.

Taken together, the quantitative and qualitative findings provide integrated support for H1–H3 by showing that affordability expectations, household characteristics, and dissatisfaction with building management all play significant roles in shaping young families’ housing evaluations and intentions.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

The results of this study highlight the interconnected economic, cultural, and institutional factors shaping the sustainability of multifamily housing for young families in Riyadh. Because affordability pressures and design needs differ across household types, policy interventions must address both structural market constraints and the specific needs of families at different stages of formation. Achieving meaningful progress toward Saudi Vision 2030 housing and liveability goals suggests that coordinated policy responses, particularly those targeting affordability constraints, governance gaps, and culturally responsive design, could holistically address the most relevant barriers identified in this study. Drawing on the study’s quantitative and qualitative evidence, three policy implications are proposed. Together, they outline a pathway for improving affordability and public confidence in multifamily living by (1) introducing next-generation affordability strategies that address the price-income gap; (2) strengthening construction quality assurance and governance frameworks; and (3) embedding culturally and family-responsive design standards to enhance the social acceptance of multifamily housing in Saudi cities.

6.1. Policy Implication 1: Addressing the Price-Income Gap Through Next-Generation Affordability Strategies

These recommendations derive directly from the results that demonstrate that affordability stress is the dominant barrier, especially among married and larger households, and especially those with children who face the strongest pressure due to higher living costs and greater spatial requirements. Single respondents and couples without children experience affordability constraints primarily through rising rental prices and limited mortgage availability. Saudi Arabia has already implemented several affordability measures under Vision 2030, including Sakani mortgage subsidies and interest-rate support. This study therefore recommends next-generation affordability interventions that build on and go beyond the existing framework.

- (i)

Expand affordable rental housing and transitional tenure options. Most policy attention has focused on ownership, but the results show that many young families face long-term affordability barriers. It is proposed that:

Public–private rental partnerships are established, offering below-market rents for young families in exchange for tax incentives.

Lease-to-own pathways that credit part of the rent toward future down payments.

This aligns with evidence from other contexts where diversified tenure models ease affordability pressure and improve housing mobility.

- (ii)

Introduce inclusionary zoning and land-value capture. Affordability stress is not only a mortgage issue but also a land-supply and pricing problem. It is therefore proposed that:

Establish inclusionary zoning requirements mandating that a percentage of new apartment developments be priced within affordable thresholds.

Land-value capture tools (e.g., development fees or value-sharing mechanisms) to fund affordable units near infrastructure investments.

These approaches may help to address structural price inflation driven by speculation and limited serviced land. Such models could enhance affordability, which could make multifamily housing more attractive for young families. These instruments could reduce the gap between price expectations and actual purchasing capacity, addressing the affordability perceptions highlighted in both the quantitative and qualitative findings.

6.2. Policy Implication 2: Strengthen Construction Quality Assurance and Governance in Multifamily Housing

The qualitative responses and satisfaction metrics indicate persistent concerns with maintenance, security, and building management, which justify strengthening governance and quality assurance mechanisms. The findings on mistrust in construction quality and poor building management indicate a governance gap. Repeated concerns about weak building standards and poor homeowners’ association management further reveal the need for institutional reform. The findings indicate that respondent satisfaction is closely linked to transparency and accountability in construction and management, suggesting that sustainability initiatives may need to incorporate these governance dimensions. The evidence indicates that the following measures could be considered to address the quality assurance and governance issues identified in this study:

Establishing a national building quality registry requiring post-occupancy performance audits and enforcing developer warranties and maintenance responsibilities during the first years of occupancy.

Expanding capacity-building programs for homeowners’ associations, supported by municipal oversight.

Promote cooperative and community-led housing models through cooperative housing initiatives where residents co-own and co-manage apartment complexes.

Improving governance mechanisms could enhance quality control, consumer protection, and social cohesion while simultaneously ensuring long-term building performance and fostering confidence in multifamily ownership structures.

6.3. Policy Implication 3: Embed Cultural and Family Responsive Design Standards in Multifamily Developments

Findings on high prioritization of privacy, layout suitability, and natural lighting support the need for culturally grounded design interventions. To strengthen social acceptance of multifamily living, the relevant governing bodies could:

Develop context-specific design guidelines for family-oriented apartments, whether at the municipal or project level, incorporating privacy zoning, flexible layouts, and provisions for extended family accommodation.

Incentivise developers who integrate culturally adaptive design elements through planning bonuses or reduced permit fees.

Encourage mixed-tenure, service-integrated housing that combines affordability with modern amenities without compromising cultural norms.

Implementing elements of these measures could help improve affordability and construction quality while strengthening public confidence in multifamily living.

These policy implications highlight that advancing multifamily housing for young families in Riyadh requires more than financial reform and demands an integrated approach linking affordability, governance, and cultural adaptation. The study contributes new empirical evidence showing how income-price perceptions, family structure, and design expectations intersect to shape residential satisfaction and ownership intentions. Implementing the proposed measures could improve affordability and construction quality and may also foster broader cultural acceptance of multifamily living. In doing so, these strategies could directly support objectives for inclusive, affordable, and resilient urban communities.

Several limitations should be noted. Firstly, regarding the study’s sampling strategy, because the study relied on purposive and voluntary response methods, respondents already engaged with the formal housing system were more likely to participate, while households using informal rental arrangements may be under-represented. The social media component also introduces self-selection bias, attracting individuals who are more active in the housing market. These dynamics help explain the demographic imbalance in the sample, including the higher proportion of male respondents, and limit the generalisability of the findings to all young families in Riyadh. Nonetheless, the sample captures a sufficiently diverse segment of active housing seekers to support the study’s explanatory objectives. Secondly, because the study uses cross-sectional data collected at a single point in time, it cannot determine cause-and-effect relationships. In addition, the findings are based on self-reported questionnaire responses, which may be influenced by how participants recall or choose to present their experiences. Moreover, relying mainly on quantitative data limits the ability to capture the subtle cultural factors that shape how families make housing decisions. Triangulating questionnaire data with qualitative or ethnographic evidence could provide deeper insight into the lived experiences, cultural expectations, and everyday decision-making processes that shape housing preferences.

A further limitation concerns the broad operational definition of young families. The sample includes married households with children, couples without children, and single adults, reflecting current household formation trends in Riyadh. This wide mix of household types may mask important differences between groups. Married households, for example, may experience stronger spatial and financial pressures than single respondents. Although marital status and family size were included as covariates, future research could stratify analyses by household type to clarify how preferences and affordability constraints vary across groups.

Future research could adopt mixed-methods or longitudinal approaches to reveal family expectations and affordability dynamics. Comparative analyses across other Saudi or Gulf cities would clarify regional variability in design and pricing pressures. Scenario modelling of mortgage and subsidy options could assess the effects of different policy frameworks. Lastly, participatory design workshops could capture gendered and inter-generational perspectives on multifamily suitability.

Finally, this study is among the first to quantitatively examine multifamily housing preferences among young Saudi families, revealing how cultural and economic perceptions jointly constrain ownership intentions. In summary, this study shows that affordability, cultural suitability, and governance weaknesses are linked together to restrain the sustainability of multifamily housing for young families in Riyadh. Economic interventions alone cannot resolve these challenges without parallel reforms in design standards and institutional oversight. By empirically linking household perceptions to broader structural conditions, this research advances understanding of how Saudi cities in transition can deliver inclusive and affordable multifamily housing consistent with the national development agenda and global sustainability goals.