Abstract

In this study, the relationships between the bearing capacity and settlement values of CL and CH clayey foundation soils and various soil parameters were analyzed in a multi-faceted manner. For this purpose, 55 test data sets for CL soils and 70 test data sets for CH soils were used. The bearing capacity, settlement values, and other soil parameters of these foundation soils were determined through experimental studies, and statistical analyses were conducted on the obtained results. Differences between the parameters of CL and CH soils were examined using the independent samples t-test, and significant differences were identified between the two clayey soil types. Overall, the differences between the parameters of CL and CH soils ranged from 1.67% to 30.89%. Prediction models were developed to estimate the bearing capacity and settlement values of both soil types based on other parameters. The correlation coefficients and significance levels between the bearing capacity and settlement values of CL and CH soils and the other soil parameters were also determined. Based on the analysis results, recommendations were proposed to increase bearing capacity and reduce settlement in CL and CH clayey soils.

1. Introduction

Geotechnical design begins with identifying key soil parameters and developing a representative soil profile for the site on which foundations will be constructed. These parameters—obtained through a combination of in situ exploration and laboratory testing—govern how loads are transferred to the ground and how the ground deforms in response [1,2,3,4]. For shallow foundations, two performance criteria dominate design: adequate bearing capacity and settlements kept within serviceability limits [5,6,7,8]. The former is controlled primarily by shear strength, while the latter reflects the soil’s compressibility and drainage characteristics under working loads [4,5,7,9,10].

The mechanics of bearing failure and settlement in clays have been studied for a century, from classical limit analyses and bearing-capacity formulations to modern reliability-based and empirical statistical approaches [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,11,12,13]. Settlement in fine-grained, saturated soils comprises an immediate (elastic) component and a time-dependent consolidation component; in highly plastic clays with low permeability, consolidation dominates and may govern serviceability [14,15,16].

Terzaghi’s one-dimensional consolidation theory provides the fundamental framework for interpreting dissipation of excess pore-water pressures and resulting volumetric strains, with the coefficient of consolidation Cv controlling the rate of settlement and compressibility indices (e.g., Cc, Cr) controlling its magnitude [2,3,8,10,13]. Because consolidation testing requires high-quality undisturbed specimens and is time-consuming, many studies have proposed predictive equations that relate compressibility indices to readily measured index properties such as liquid limit (LL), plasticity index (PI), natural water content wn, initial void ratio eo, specific gravity Gs, and unit weights [17,18,19,20,21,22,23].

These empirical or regression-based models aim to reduce cost and turnaround time without excessively compromising accuracy, although their transferability can be limited by local geology, depositional history, and stress path. While such correlations are abundant for compressibility, fewer studies have jointly examined how commonly measured parameters grain-size fractions, Atterberg limits, unit weights, groundwater level, and sampling depth/elevation statistically co-vary with both bearing capacity and settlement behaviours in clays using site-specific data sets [23,24]. Moreover, many correlations are reported for granular soils or mixed conditions, whereas design in soft to stiff clays in seismic and tectonically active basins (e.g., northwestern Türkiye) requires locally calibrated relations [3,16,25,26,27].

Within this broader context, Düzce and its surroundings provide a relevant natural laboratory. The region’s Quaternary deposits and documented geotechnical performance following major earthquakes have been extensively described in geological and engineering reports, which underline the variability of fine-grained units and the implications for foundation response [25,26,27]. Although these sources establish the geological framework and general geotechnical conditions, there remains a practical need for site-derived statistical evidence quantifying how routine parameters relate to bearing capacity and settlements for distinct clay classes [(e.g., CL vs. CH under EN/TS classification schemes, Turkish Standards Institution [TSE], 2006, 2000)]; [28,29,30,31].

This study addresses that gap by compiling a curated data set from boreholes in the Darıca and Azmimilli neighbourhoods of Düzce Province and conducting a statistical evaluation of soil parameters governing the bearing capacity and settlement behaviours of CL and CH clays.

Specifically, we

- (i)

- determine bearing capacity, settlements, and eleven complementary soil parameters from experimental programs;

- (ii)

- quantify parameter–response associations using correlation analysis with significance testing;

- (iii)

- assess differences between CL and CH using independent-samples t-tests; and

- (iv)

- develop predictive models for bearing capacity and settlement based on routinely measured variables.

In doing so, we build on classical soil mechanics and consolidation theory while leveraging the practical value of empirical and regression-based prediction in design workflows. The resulting relations are intended to support preliminary and detailed design stages by identifying which parameters most strongly govern capacity and settlement in local clays, and by providing calibrated, statistically defensible estimates for sites with similar geological context [2,17,28].

2. Study Area

The Düzce Basin, located in north-western Türkiye between 40°37′–41°07′ N latitudes and 30°49′–31°50′ E longitudes, occupies a transitional position between the Eastern Marmara and Western Black Sea regions (Figure 1) [30]. Covering an area of approximately 2593 km2, it represents one of the most active tectonic depressions along the North Anatolian Fault Zone (NAFZ). The basin is morphologically defined by a broad alluvial plain surrounded by steep mountainous terrains, where tectonic uplift and sedimentation have interacted throughout the Quaternary period to produce a flat, flood-prone topography.

Figure 1.

Study area (Google Maps/Düzce) [30].

The region’s humid temperate climate, high annual precipitation, and dense fluvial network feeding into the plain have led to continuous alluvial and lacustrine sedimentation, which in turn has produced soft, fine-grained soils with low bearing strength and high compressibility [31,32,33,34].

These conditions make the Düzce Basin a natural laboratory for understanding the relationship between geological, hydrological, and engineering properties of soils. Due to its unique geomorphological and hydroclimatic characteristics, the basin exhibits a delicate balance between sediment deposition, consolidation, and tectonic deformation. Consequently, it provides a highly suitable case study area for analyzing the statistical interactions among soil parameters, bearing capacity, and settlement behaviours of cohesive soils under both static and dynamic loading conditions.

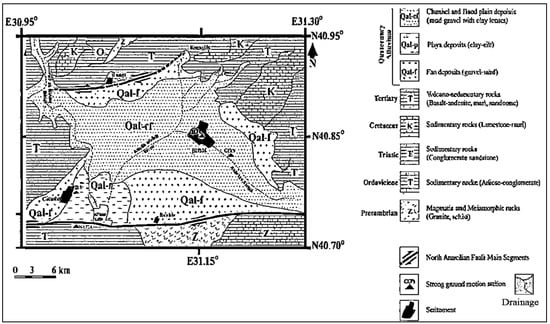

Geologically, the Düzce Basin consists of Plio–Quaternary basin-fill deposits overlying pre-Pliocene metamorphic and volcanic basement rocks, with sediment thickness exceeding 100 m and reaching up to 260 m in some areas [35,36,37,38,39]. These deposits are dominated by fluvial, alluvial, and lacustrine sediments formed under alternating high- and low-energy depositional regimes (Figure 2). Their predominantly clastic composition, gravel, sand, silt, and clay, reflects the periodic shifts between fluvial transport and lacustrine still-water deposition [40,41,42,43].

Figure 2.

Geological and stratigraphic framework of the Düzce Basin showing Plio–Quaternary alluvial and lacustrine deposits (Qal2, Qal3) [28,30,31].

Mineralogical analyses indicate that montmorillonite and chlorite dominate the clay fraction, with minor constituents of illite, quartz, feldspar, and calcite. These minerals, known for their high-water retention and swelling potential, explain the basin’s prevalent compressibility and settlement issues. According to the Unified Soil Classification System, the soils predominantly fall within CL (low to medium plasticity clays) and CH (high plasticity clays) groups, while minor portions belong to CL–ML and MH–OH transitional types [28]. The natural unit weight averages 17.68 kN/m3, the grain unit weight 26.3 kN/m3, and the clay-size fraction ranges from 9% to 40%, confirming the dominance of cohesive, low-permeability materials [28].

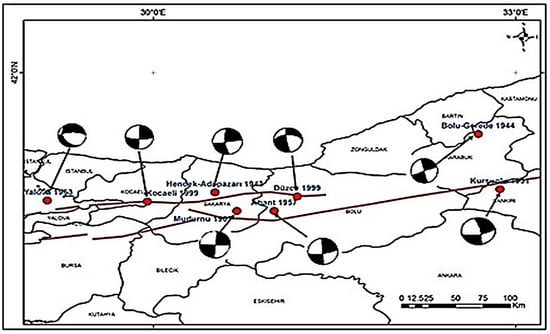

The Düzce Basin is directly aligned with the North Anatolian Fault (NAF), one of the world’s most active right-lateral strike-slip fault systems extending 1200–1600 km across northern Türkiye [35,36,37,38,39]. The Düzce Fault, which bounds the southern margin of the plain, acts as a principal structural boundary controlling both the basin’s formation and its ongoing tectonic activity [40,41,42,43].

Throughout the 20th century, the Düzce region has been the site of several major earthquakes, including the 1999 Düzce (Mw 7.2) and 1999 Kocaeli (Mw 7.4) events, as well as the 1967 Mudurnu (Ms 7.1), 1957 Bolu–Abant (Ms 7.0), 1944 Bolu–Gerede, and 1943 Hendek earthquakes [44,45,46,47,48]. The Kocaeli Earthquake produced a 145 km rupture divided into four main segments—Hendek, Karamürsel–Gölcük, İzmit–Sapanca, and Sapanca–Akyazı–Karadere [49,50,51,52,53,54]. Shortly afterward, the Düzce Earthquake extended this rupture by another 40 km along the Karadere segment, forming the eastern continuation of the August rupture [55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62]. Vertical displacements of up to 3 m were recorded south of Efteni Lake, which currently represents the depositional centre of the basin [63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71]. The high recurrence of seismic events demonstrates that the Düzce Basin is still an actively deforming pull-apart structure. These tectonic processes not only control the geometry of sedimentary units but also induce secondary effects such as groundwater table fluctuations, excess pore pressure generation, and cyclic degradation of soil structure, all of which reduce bearing capacity and increase settlement risk in engineering applications (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Seismotectonic framework of the Düzce Basin showing the North Anatolian Fault (NAF), major surface ruptures of the 1999 Kocaeli and Düzce earthquakes, modified [55,56,70,71,72,73].

The geotechnical environment of the Düzce Basin is defined by fine-grained cohesive soils, shallow groundwater, and high compressibility. Groundwater levels fluctuate between 0.1 and 2.6 m, creating near-saturated conditions that persist through most of the year. Laboratory and field investigations indicate that the upper 10 m of the clayey sequence is over consolidated due to historic geological loading, while deeper layers exhibit normally consolidated behaviour [28,69]. These stratified mechanical properties lead to non-linear settlement patterns under structural loads.

Oedometer and triaxial tests confirm that the soils possess low permeability and slow pore pressure dissipation, typical of CH clays with high plasticity. The compression index (Cc) and coefficient of consolidation (Cv) vary according to mineralogical composition, effective stress history, and depositional setting, reflecting the basin’s complex consolidation behaviour. Accurately determining these parameters is essential for assessing the long-term settlement and bearing performance of foundations in this region [55,56,57,58,59,60,61,70,71,72,73].

The combination of soft, water-saturated soils and high seismicity poses considerable challenges to foundation engineering. During strong ground motion, increased pore pressures and reduced effective stress may trigger liquefaction, subsidence, or excessive settlement, particularly in the central parts of the basin where clayey–silty lacustrine units dominate. Consequently, reliable statistical and analytical models that integrate both mechanical and hydraulic soil parameters are crucial for safe geotechnical design in this highly dynamic basin [56,57,58].

3. Analytical Estimation of Bearing Capacity and Settlement

The ultimate bearing capacity (Qult) of the soils was calculated using the Terzaghi (1943) formulation for shallow foundations, which is derived from Prandtl’s (1921) theory of plastic equilibrium in soils [1,2,4,7,15,17].

The general form of the bearing capacity equation is

where

Qult= c × Nc × Sc ×dc × ic + γ ×Df × Nq × Sq × dq × iq + 0.5 × γ ×B ×Nγ × Sγ × dγ × iγ.

Df = depth of foundation; B = width of footing; γ = unit weight of soil; c = cohesion

Nc, Nq, Nγ = bearing capacity factors measured for the respective value of angle of internal friction (ɸ)

Sc, Sq, Sγ = shape factors;

dc, dq, dγ = depth factors;

ic, iq, iγ = inclination factors;

In cohesive soils (silts and clays), the internal friction angle is often small or negligible; therefore, cohesion and unit weight become dominant parameters.

The literature indicates that the internal friction angle is smallest in clayey soils (0–25°), moderately higher in silty soils (20–32°), and highest in sandy soils (30–45°+), reflecting the progressive increase in particle interlocking and frictional resistance from fine-grained cohesive materials to coarse-grained granular soils [28,67,68,69,70,74].

The apparent cohesion arising from electrochemical bonding between clay particles and water molecules also contributes to shear resistance, especially in high-plasticity soils. For this reason, two analytical frameworks—the total stress approach (undrained condition) and the effective stress approach (drained condition)—were considered to reflect short- and long-term behaviours, respectively.

Settlement (S) values were estimated based on Terzaghi’s one-dimensional consolidation theory, which models the time-dependent compression of saturated clays under loading [1,2,21,22]. Consolidation parameters, particularly the compression index (Cc) and coefficient of consolidation (Cv), were obtained from oedometer tests. The total settlement (St) was expressed as the sum of immediate (Si), primary (Sc), and secondary (Ss) components, although primary consolidation was the dominant process for the investigated soils (St = Si + Sc + Ss).

3.1. Statistical Analysis Framework

Statistical analysis was conducted to determine the degree and direction of relationships between soil parameters and geotechnical responses (bearing capacity and settlement). Comparison tests, bivariate correlation and multivariate regression methods were employed using SPSS v.26 software [28,75].

Initially, Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) were computed to evaluate linear relationships among eleven independent soil parameters, including SPT-N30, groundwater depth, unit weight, water content, percent fines (No. 200 sieve), Atterberg limits, cohesion, and internal friction angle. Statistical significance was assessed at 95% (p < 0.05) and 99% (p < 0.01) confidence levels [75].

Following correlation analysis, multiple regression models were developed to predict both bearing capacity and settlement as dependent variables. Regression diagnostics—such as R2, adjusted R2, F-statistic, and standard error of estimate—were used to evaluate model reliability. Stepwise regression was applied to identify the most influential predictors while minimizing multicollinearity.

The statistical relationships were interpreted separately for CL and CH soils to highlight behavioural differences linked to plasticity and drainage conditions. A cubic regression model was found to yield the best performance (R2 = 0.79) for estimating bearing capacity, whereas a quadratic model achieved superior accuracy (R2 = 0.90) for settlement prediction. The models were validated through residual analysis and significance testing, confirming their robustness at a 95% confidence level.

The last studies conducted to date demonstrate that the variability of soil parameters and the interactions among these parameters play a decisive role in both bearing capacity and settlement performance criteria. Accordingly, the four studies reviewed represent classical, statistical, and probabilistic approaches used to understand bearing capacity–settlement behaviour across different soil types.

In the literature a study evaluated the relationships among soil parameters influencing foundation settlement and bearing capacity using extensive field and laboratory data. The study identified that water content, plasticity, and degree of compaction exhibit strong sensitivity with respect to settlement, whereas bearing capacity is more strongly governed by unit weight, cohesion, and internal friction angle [76,77,78]. Calculations based on classical bearing capacity theories (Terzaghi theory, Meyerhof theory, Hansen theory) and consolidation approaches revealed that regional soil characteristics significantly affect design parameters. By establishing a broad local geotechnical database, the study contributes to improving the reliability of engineering correlations.

The other study advanced beyond deterministic analyses by addressing the uncertainty arising from the natural variability of soil properties within a probabilistic framework [78,79,80]. The study discussed statistical concepts such as spatial variability, coefficient of variation, correlation length, and probability distributions. Using Monte Carlo simulations and random field theory, the authors demonstrated that uncertainty in bearing capacity predictions may reduce the estimated capacity by approximately 20–60%. This work provides a theoretical foundation emphasizing the importance of uncertainty-based design in geotechnical engineering.

Lastly, another study investigated the parameters affecting bearing capacity and settlement behaviour in gravelly soils through statistical analyses. SPT, grain-size distribution, unit weight, and water content data obtained from 27 boreholes were evaluated using regression models [28]. The results indicated that the SPT-N value is the most influential parameter in predicting both bearing capacity and settlement. Cubic regression models produced high-accuracy estimations, outperforming classical approaches and quantifying the relative importance of soil parameters.

When these three studies are evaluated collectively, three complementary approaches emerge in understanding the influence of soil parameters on bearing capacity and settlement behaviour:

- (1)

- Classical deterministic analyses reveal the direct effects of soil properties on foundation design.

- (2)

- Statistical models quantify the relative importance and predictive strength of soil parameters, highlighting dominant variables such as SPT-N, water content, and unit weight.

- (3)

- Probabilistic approaches demonstrate how soil variability influences design reliability and expose the limitations of purely deterministic methods [28,75,81].

Therefore, in modern foundation engineering, integrating deterministic, statistical, and probabilistic methodologies offers a more robust and reliable assessment of bearing capacity and settlement behaviour.

3.2. Methodological Reliability and Limitations

It should be noted that all analyses were performed using real field and laboratory data, rather than controlled laboratory datasets. This enhances the representativeness of the results but introduces variability inherent to natural soil conditions. While empirical and analytical models were harmonized through statistical calibration, potential sources of uncertainty, such as sampling disturbance, groundwater fluctuation, and local heterogeneity, were considered in the interpretation of results. The combined use of geotechnical testing, analytical modelling, and statistical evaluation allows for a comprehensive understanding of the bearing capacity–settlement relationship in cohesive soils. The methodology thus provides a foundation for developing region-specific design parameters applicable to the seismically active Düzce Basin and similar alluvial settings.

3.3. Results and Statistical Evaluation

The descriptive statistical results of the CL-type and CH-type clayey soils are presented in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. These datasets summarize the main physical and mechanical characteristics, including bearing capacity, settlement, groundwater level, unit weight, water content, and Atterberg limits. A total of 55 measurements for CL soils and 70 measurements for CH soils were analyzed to establish the statistical distributions used in subsequent correlation and regression analyses.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of CL type clay soil samples.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of CH type clay soil samples.

In CL-type clay soils, the bearing capacity varies between 1.96 and 5.67 kgf/cm2 with a mean of 3.19 kgf/cm2, while settlement ranges from 0.88 to 5.83 cm (mean = 2.77 cm). The groundwater table fluctuates between 2 and 9 m, indicating significant hydrological variability within the investigated area. SPT-N30 values range from 6 to 53, reflecting the heterogeneous density and stiffness of the clayey layers. The unit weight (1.43–2.03 g/cm3) and water content (5.46–68.64%) show considerable variation, consistent with alternating layers of saturated and partially saturated clays. The liquid limit (18–49%) and plastic limit (8–24%) reveal moderate to high plasticity, classifying the soils mainly as CL-type (medium plasticity) according to the Unified Soil Classification System (USCS) [82,83,84,85,86]. The cohesion values (20.37–72.76 kPa) suggest moderate shear resistance, increasing with plasticity and clay mineral content (Table 1).

3.4. Methodology

This study combines geotechnical field data, laboratory testing, and statistical modelling techniques to evaluate the relationships among soil parameters, bearing capacity, and settlement behaviours of CL and CH type clayey soils in the Düzce Basin.

The workflow involves four principal stages:

- (i)

- Data acquisition and classification;

- (ii)

- Determination of soil strength and deformation parameters;

- (iii)

- Estimation of bearing capacity and settlement using analytical formulations;

- (iv)

- Statistical evaluation through descriptive statistics, comparison test, correlation and regression analyses.

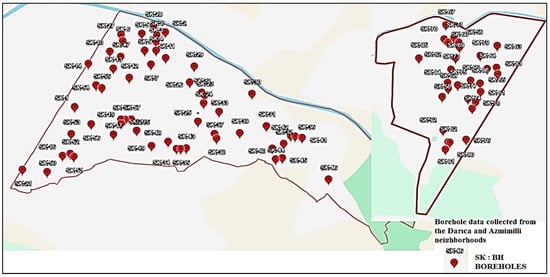

3.5. Data Acquisition and Laboratory Testing

A comprehensive subsurface investigation program was executed across the designated borehole locations to characterize the geotechnical conditions governing the project site. The dataset used in this research was obtained from 55 borehole for CL soils and 70 boreholes for CH soils drilled in the Darıca and Azmimilli neighbourhoods of Düzce city centre (Figure 4). Boreholes were advanced using rotary drilling techniques suitable for retrieving both disturbed and undisturbed samples. The boreholes were logged to various depths depending on lithological continuity, and undisturbed soil samples were collected for laboratory analysis (Figure 5). All tests were carried out in accordance with ASTM [83] and TSE EN ISO [84] standards to ensure data reliability and reproducibility.

Figure 4.

Geological framework of the Düzce Basin and locations of boreholes in the Darıca and Azmimilli neighbourhoods.

Figure 5.

Example of borehole BH1 (SK1), SPT, laboratory samples.

The Standard Penetration Test (SPT) was systematically performed at 1.5 m depth intervals, as well as at all identified strata interfaces, in accordance with internationally recognized geotechnical testing standards. Recorded SPT N-values were subsequently corrected for overburden pressure and energy ratio and were utilized as primary indicators of in situ density, stiffness, and relative consistency of the encountered soils. These parameters served as essential inputs for the evaluation of bearing capacity, settlement potential, and general foundation performance.

Disturbed and undisturbed soil specimens obtained during drilling were subjected to an extensive suite of soil mechanics laboratory tests. The testing program comprised determination of natural water content, bulk and dry unit weight, grain-size distribution (sieve and hydrometer analyses), Atterberg limits, unconfined compressive strength, triaxial shear tests (UU and CU configurations), and one-dimensional oedometer consolidation tests. The results facilitated rigorous soil classification and the derivation of key engineering parameters, including effective cohesion (c′), internal friction angle (φ′), constrained modulus (M), compressibility coefficient (mv), and consolidation characteristics [82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89].

The integration of field and laboratory findings provided a robust geotechnical framework for the site, enabling a refined assessment of ultimate and allowable bearing capacity, predicted settlement behaviour under structural loading, and the identification of potential ground improvement requirements. This comprehensive characterization forms the basis for subsequent geotechnical design, modelling, and risk evaluation in accordance with contemporary engineering practice.

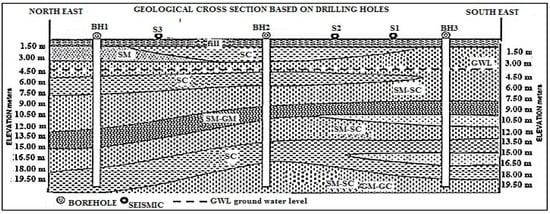

Borehole data collected from the Darıca and Azmimilli neighbourhoods reveal cyclic stratification composed of fine-grained gravel, silty sand, silt, and clay interlayers. The Qal2 unit consists primarily of brown-to-grey clayey–silty sand and gravel, while Qal3 deposits comprise thicker (up to 40 m) layers of silty clay and clayey silt that gradually transition to coarser sediments toward the basin margins. Standard Penetration Test (SPT-N30) values range from 10 to 50, indicating soil densities from loose to dense states, and reflecting the heterogeneity of depositional environments within the basin (Figure 6) [28].

Figure 6.

Cross-sectional representation of borehole lithology, groundwater table, and consolidation zones across the study area [28].

Laboratory testing included measurements of natural unit weight, water content, Atterberg limits (liquid and plastic limits), grain size distribution (No. 10 and No. 200 sieves), specific gravity, and unconfined compressive strength. Field data such as SPT-N30 values, groundwater levels, and excavation elevations were also recorded. The classification of soils into CL (low to medium plasticity) and CH (high plasticity) groups was based on the Unified Soil Classification System (USCS), supported by Atterberg limits and particle size analyses. In total, 55 data points for CL soils and 70 data points for CH soils were used in the statistical evaluation. The bearing capacity and settlement values were determined both analytically and experimentally, providing a comprehensive dataset for correlation modelling.

In CH-type clay soils, the bearing capacity ranges from 1.61 to 6.70 kgf/cm2 (mean = 3.31 kgf/cm2), while the settlement values vary between 1.13 and 5.77 cm (mean = 3.00 cm). Compared with CL soils, CH soils display slightly higher mean bearing capacity but also greater settlement, indicating higher compressibility. The SPT-N30 values (3–42) and unit weights (1.42–2.05 g/cm3) reveal that CH soils are denser but less uniform than CL soils. Water content (9.10–39.70%) and Atterberg limits—particularly the liquid limit (18–58.5%)—are higher, confirming the presence of high-plasticity clays with stronger interparticle bonding. The cohesion values, which range from 26.52 to 82.30 kPa, are notably greater than those of CL soils, reinforcing the observation that CH soils exhibit higher shear strength but lower drainage potential (Table 2).

Overall, these descriptive statistics highlight that the physical and mechanical heterogeneity of the Düzce Basin soils is controlled by variations in water content, particle size distribution, and mineralogical composition. The pronounced differences between CL and CH type clay soil groups, particularly in cohesion and liquid limit, underline the influence of plasticity and moisture on the bearing capacity and settlement behaviours of clayey foundations in the region

3.6. Bearing Capacity Analysis

The degree of association and relative significance among the geotechnical parameters influencing soil bearing capacity were assessed through correlation analysis, and the results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Correlation Analysis Results for CL Soil Samples.

In CL-type clayey soils, strong negative correlations were identified between bearing capacity and settlement, groundwater level, and the percentage of material passing through the No. 10 sieve. This indicates that bearing capacity tends to increase as settlement, groundwater level, and fine-grained content decrease. These relationships were found to be highly significant, with p values of 0.000, 0.006, and 0.004, respectively, confirming their statistical reliability at the 95% confidence level. A weaker but positive correlation was observed between bearing capacity and the percentage of material passing through the No. 200 sieve (p = 0.11), suggesting that a higher proportion of very fine particles may slightly enhance soil cohesion and, consequently, its load-bearing capacity. In contrast, settlement exhibited a strong negative correlation with bearing capacity (p = 0.000 *) and a positive, though less significant, correlation with groundwater level (p = 0.196 *). These findings highlight the combined influence of hydrogeological and textural properties on the mechanical response of CL clay soils. Similarly, correlation analysis for CH-type clayey soils revealed comparable trends, where variations in settlement, groundwater level, and fine content also played a dominant role in controlling bearing capacity. The detailed results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Correlation analysis results for CH clay soil samples.

In CH-type clayey soils; negative correlations were identified between bearing capacity, settlement, and groundwater level, indicating that the bearing capacity tends to increase as both settlement and groundwater level decrease. These relationships were statistically significant, with p values of 0.039 and 0.066, respectively, suggesting that pore water pressure and compressibility play a key role in limiting load-bearing performance. Conversely, positive correlations were observed between bearing capacity and excavation elevation, unit weight, and water content, with corresponding p values of 0.059, 0.024, and 0.000, respectively. These results indicate that soils located at higher elevations, with greater density and moisture, exhibit improved load-carrying capacity due to enhanced compaction and bonding among fine particles. A weaker but still positive relationship was also observed between bearing capacity and plastic limit (p = 0.113 *), suggesting that increased plasticity marginally contributes to shear strength. For the same soil group, settlement exhibited a strong inverse relationship with bearing capacity (p = 0.039 *), while it showed statistically significant positive correlations with liquid limit (p = 0.028 *), plasticity index (p = 0.006 *), and a slight negative correlation with water content (p = 0.092 *). These findings collectively highlight that both hydro-mechanical and plasticity-related properties govern the deformation and strength behaviour of high-plasticity clays. To further quantify the influence of these geotechnical parameters on bearing capacity, a multiple linear regression analysis was performed at the 95% confidence level. The resulting predictive models and their statistical parameters are summarized in Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 5.

Multiple linear regression analysis results for CL soil samples.

Table 6.

Multiple linear regression analysis results for CH soil samples.

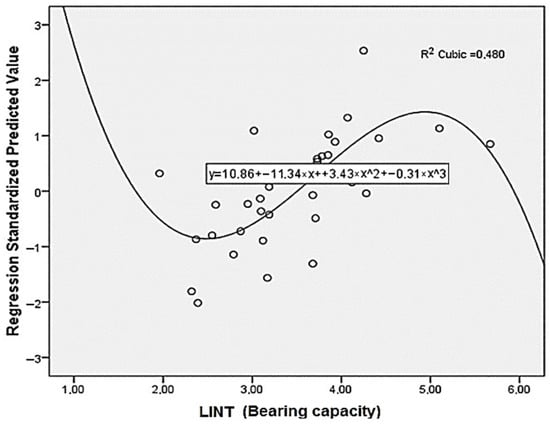

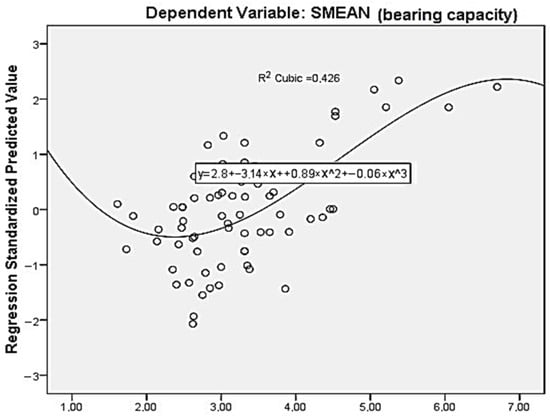

The dependent variable, bearing capacity, was predicted using cubic regression models derived from the analyzed soil parameters. The relationship between observed and model-estimated bearing capacities was illustrated through comparative plots, and the coefficient of determination (R2) values demonstrating the model fit are provided in Figure 7 and Figure 8.

Figure 7.

Cubic estimation model and R2 value for CL soil samples.

Figure 8.

Cubic estimation model and R2 value for CH clay soil samples.

3.7. Settlement Analysis; Consolidation Analysis Results

In order to estimate the settlement value of the soil depending on the soil parameters, which are independent variables, multiple linear regression analysis was performed at a confidence interval of 95% and the results are shown below (Table 7 and Table 8).

Table 7.

Multiple linear regression analysis results for settlement of CL clay soil samples.

Table 8.

Multiple linear regression analysis results for settlement of CH clay soil samples.

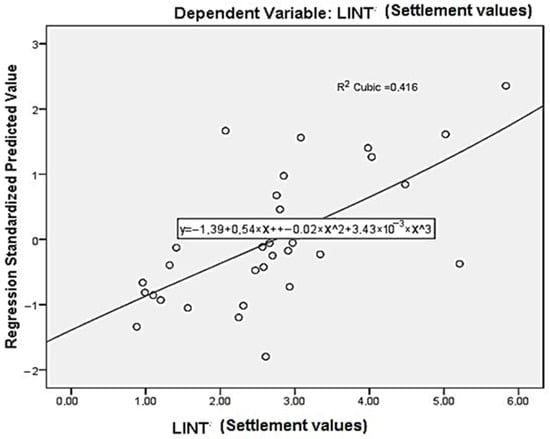

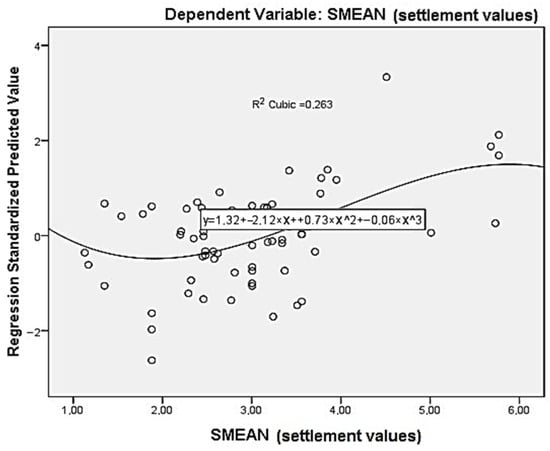

The dependent variable, the settlement values of the soil, was estimated with cubic mathematical estimation models according to the examined soil parameters, and the actual bearing capacity values and the estimated bearing capacity values were shown in graphs and correlation coefficients (R2) were given (Figure 9 and Figure 10).

Figure 9.

Cubic estimation model and R2 value for CL clay soil samples.

Figure 10.

Cubic estimation model and R2 value for CH clay soil samples.

3.8. Comparing the Bearing Capacity Parameters of CL and CH Soil Samples

An independent samples t-test was used to analyze whether there was a significant difference between the bearing capacity, settlement, internal friction angle, and cohesion coefficients of the examined Cl and CH type clay soil samples. The analysis results in terms of bearing capacity, settlement, internal friction angle, and cohesion coefficient are presented in tabular form below (Table 9).

Table 9.

Descriptive statistics for CL and CH soil samples.

When the average soil parameters presented in the table are examined, it becomes evident that CL-type clayey soils generally exhibit lower values of bearing capacity, settlement, cohesion, unit weight, water content, the proportion of material passing the No. 10 and No. 200 sieves, liquid limit, and plastic limit compared to CH-type clayey soils. Conversely, the internal friction angle and SPT-N30 values of CL soils are comparatively higher, indicating a denser structure and greater resistance to penetration. To statistically verify these differences between the two soil groups, an independent samples t-test was conducted. The comparative results of the geotechnical parameters for CL and CH clayey soils are presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

Independent samples t-test for the whole parameters of CL and CH soil samples.

The existence of significant differences between the soil parameters of CL and CH type clayey soils was analyzed using an independent samples t-test. When the table was examined, it was determined that there were significant differences at the 95% confidence interval between the cohesion coefficients (Sig. 0.000), the amount of soil passing through the sieve no. 200 (Sig. 0.003), liquid limit (Sig. 0.000), and plastic limit values (Sig. 0.000) of CL and CH type clayey soils. While the average cohesion coefficient in CL type soil was found to be 46.96, the average in CH type soil was found to be 57.13 and this difference was found to be significant at the 95% confidence interval (Sig. 0.000). The amount of soil passing through sieve No. 200 was found to be 73.48% on average in CL type soil, while the average in CH type soil was found to be 82.87% and this difference was found to be significant at the 95% confidence interval (Sig. 0.003). The average Liquid Limit in CL type soil was found to be 41.00% on average in CH type soil, while the average in CH type soil was found to be 52.43% and this difference was found to be significant at the 95% confidence interval (Sig. 0.000). The average Plastic Limit in CL type soil was found to be 18.98% on average in CH type soil, while the average in CH type soil was found to be 22.53% and this difference was found to be significant at the 95% confidence interval (Sig. 0.000).

4. Discussion

The settlements that occur in soils consist of two components: elastic settlement and consolidation settlement. Elastic settlement is also defined as sudden settlement and occurs during the construction period when the structure load is transferred to the soil. Consolidation settlement is a process that takes a long time to complete. The settlements that cause damage to structures consist of the sum of these two elements. Especially in soils subjected to preloading, elastic collapse covers a significant part of the total collapse. Since the soil is heterogeneous, it is not expected to show the same behaviour on every side of the structure. In this case, there may be settlements exceeding the limit values in the structure in the soil section that is weaker in terms of settlement. Due to these settlements, additional stresses, cracks, and settlements may occur in the load-bearing elements of rigid structures.

Therefore, it is important to determine the magnitude of both settlement components as well as the rigidity of the structure. The settlements in the ground and the bearing capacity of the ground generally depend on important parameters such as the load acting on the ground, the unit weight of the ground, the cohesion coefficient of the ground, the internal friction angle, the Poisson ratio, the modulus of elasticity, the void ratio, the degree of saturation, the groundwater level, the rigidity coefficient of the ground, and the narrow side width of the foundation resting on the ground. However, which of these affect the bearing capacity and consolidation properties of the soil and whether the levels of effect are the same for all or different from each other are important issues.

The importance levels of the relationships between the bearing capacity and consolidation properties of the soil and other parameters should be known. While making these determinations, showing which of the physical properties of the examined soil affect the bearing capacity and settlement values with numerical values will contribute to the evaluation of the soil and the design of foundation models.

Correlation analyses were performed to determine the parameters that significantly affect the bearing capacity and settlement. Correlation analysis is a statistical method used to measure the strength and direction of the relationship between variables. The correlation coefficient, which varies between −1 and +1, measures the linear relationship between two variables regardless of the measurement units. A coefficient close to 0 indicates a weak relationship, while values approaching +1 or −1 indicate strong positive or negative relationships, respectively. The correlation levels between the parameters are summarized.

- 0.00–0.25 Very weak relationship

- 0.26–0.49 Weak relationship

- 0.50–0.69 Moderate relationship

- 0.70–0.89 High relationship

- 0.90–1.00 Very high relationship

Multiple linear regression analysis with 95% confidence interval was conducted to estimate the bearing capacity and consolidation behaviour of soil based on the effective parameters identified in the correlation analysis. Multiple linear regression is a statistical technique used to develop a mathematical model that quantifies the effect of multiple independent variables on a single dependent variable, thus allowing the dependent variable to be estimated as a function of the independent variables. Let us assume that Ŷ represents the dependent variable and x1, x2, x3, …, xn represent the independent variables. The relationship between the dependent and independent variables can be expressed as follows:

where Y is the dependent variable; a0 is the constant term of the equation; a0, a1, …, an are the coefficients of the independent variables x1, x2, …, xn are the independent variables; and ei is the error term, which represents the difference between the observed value and the predicted value (Y − Ŷ).

Ŷ = a0 + a1 × x1 + a2 × x2 + … + an × xn + ei

If each experimental data point is denoted by “yi” and their average by “ȳ”, the deviation from the mean (yi − ȳ) for each experimental data point is calculated using the least squares method. These deviations from the mean (yi − ȳ) are defined as the change for the experimental data. Total change is defined as the sum of explainable and unexplained changes.

Unexplained change is denoted by “ei” and is calculated as the error term of the i-th experimental data point using “ei = yi − ŷ”. Explainable change is the difference between the average of each predicted experimental result and the actual experimental result, calculated as “ŷ − ȳ”. In this case, the “Total change” can be calculated as follows:

where

(yi − ȳ) = (yi − ŷ) + (ŷ − ȳ)

yi: Real experimental data;

ȳ: Averages of actual experimental data;

ŷ: Predicted test results.

For prediction models obtained using multiple linear regression, the “Standard Error of Prediction” is calculated using the concept of total variation with the following expression:

The left side of the equation represents the total variability (sum of squared errors), the first term on the right side represents the unexplained variability (sum of squared errors), and the second term represents the explainable variability (sum of squared regression errors).

If the predictive model can predict each of the actual experimental results as the same value, the sum of unexplained variability (sum of squared errors) is zero “0”. In this case, the standard error “Se” of the prediction obtained with “n” data sets and “n − 2” degrees of freedom is calculated as follows:

5. Conclusions

Independent t-test was used to analyze whether there was a significant difference between the parameters of CL and CH soil types, and it was found that significant differences were found between the cohesion coefficient, the amount of soil exceeding N0 200, Liquid Limit, and Plastic Limit values, while no significant difference was found between the other parameters.

In this study, the bearing capacities and settlement values of CL and CH soil types were examined comparatively. Therefore, the relationships between the bearing capacities and settlement amounts of CL and CH soil types and other parameters were evaluated and interpreted.

The relationships between the other parameters are given as numerical values in Table 3 and Table 4. When the relationships between the bearing capacity and settlement amount of CL type soil and other parameters were examined.

In CL type soil, there is a highly significant negative relationship between bearing capacity and settlement at Sig. 0.000. There is a highly significant negative relationship with the groundwater level at Sig. 0.006. There is a highly significant negative relationship with the No. 10 sieve at Sig. 0.004. There is also a positive relationship with the amount of soil passing through the No. 200 sieve at Sig. 0.110. In this case, it has been determined that the bearing capacity of the soil will increase significantly as the amount of settlement, the groundwater level, and the amount of soil passing through the No. 10 sieve decrease. The bearing capacity will also increase as the amount of soil passing through the No. 200 sieve increases.

In CL type soil, there is a highly significant negative relationship between bearing capacity and settlement at Sig. 0.000. As the amount of settlement increases, the bearing capacity decreases. There is a positive relationship between the groundwater level and settlement at Sig. 0.196. It can be said that as the groundwater level increases, the amount of settlement will also increase.

A significant negative relationship (Sig. 0.039) was found between the bearing capacity and settlement in CH type soil. As the settlement amount increased, the bearing capacity decreased. As the groundwater level increased, the bearing capacity decreased with a significance level of Sig. 0.066. As the excavation elevation increased, the bearing capacity increased with a significance level of Sig. 0.059. As the unit weight increased, the bearing capacity increased with a significance level of Sig. 0.024. A significant positive relationship (Sig. 0.000) was found between water content and bearing capacity.

- In CH type soil, as the SPT-N30 value increased, the settlement increased with a significance level of Sig.0.028. As the plastic limit increased, the settlement increased with a significance level of Sig. 0.006. It was observed that there are differences between the parameters of CL type soil and CH type soil, ranging from 1.67% to 30.89%.

- The average bearing capacity of CL type soil is 3.19, while that of CH type soil is 3.31, and the bearing capacity of CH type soil is approximately 3.76% more.

- The average settlement of CL type soil is 2.77, while that of CH type soil is 3.00, and the settlement of CH type soil is approximately 8.30% more.

- The average internal friction angle of CL type soil is 5.33, while that of CH type soil is 5.02, and the angle of internal friction of CL type soil is approximately 6.17% more.

- The average cohesion coefficient of CL type soil is 46.96, while that of CH type soil is 57.13, and the cohesion coefficient of CH type soil is approximately 21.65% more.

- The average SPT-N30 value for the CL soil is 13.91, while that for the CH soil is 11.80, meaning the SPT-N30 value for the CL soil is approximately 17.88% higher.

- The average unit weight of the CL soil is 1.79, while that for the CH soil is approximately 1.67% higher.

- The average water content of CL type soil is 21.89, while the water content of CH type soil is 24.17, and the water content of CH type soil is about 10.41% higher, the average amount of soil passing through the No. 10 sieve in CL type soil is 8.35, while the amount of soil passing through the No. 10 sieve in CH type soil is 10.93, while the amount of soil passing through the No. 10 sieve in CH type soil is about 30.89% higher, the average amount of soil passing through the No. 200 sieve in CL type soil is 73.48, while the amount of soil passing through the No. 200 sieve in CH type soil is 82.87, the average liquid limit in CL type soil is 41.00, while the amount of liquid limit in CH type soil is 52.43, while the liquid limit in CH type soil is about 30.89% higher, 12.87% higher, and the average plastic limit in CL type soil is 18.98, while the amount of plastic limit in CH type soil is 22.53, while the CH type the plastic limit of the soil was 18.98, while the plastic limit of the CH type soil was 22.53, and the plastic limit was found to be approximately 30.89% higher in the CH type soil. It was observed that the plastic limit of the type soil was approximately 18.70% higher.

Since this study includes the analysis of the bearing capacity and settlement values of CL and CH type clayey soils, the relationship coefficients between the bearing capacity and settlement values and other parameters are shown in tabular form and the results are evaluated comparatively (Table 11).

Table 11.

Comparison of the importance levels of CL and CH type clayey soil parameters.

When the table is examined, it is seen that there is a negative relationship between the bearing capacity, the amount of GWT, and settlement for both CL and CH soil types.

- It is observed that as the groundwater level and the amount of settlement increase, the bearing capacity of the soil decreases, and both have a very significant relationship.

- It was found that the amount of soil passing through the number 10 sieve significantly reduces the bearing capacity for the CL type soil (Sig. 0.04), while in the CH type soil, the bearing capacity increases significantly with increasing unit weight (Sig. 0.024) and water content (Sig. 0.00).

- It was found that the bearing capacity decreases significantly in the CL type soil (Sig. 0.000), while in the CH type soil, the settlement increases significantly with increasing SPT-N30 number (Sig. 0.028), and the settlement increases significantly with increasing plastic limit (Sig. 0.006).

The correlation coefficients and significance levels between soil parameters other than bearing capacity and settlement parameters for CL and CH soil types are shown below (Table 12).

Table 12.

Relationship and importance coefficients between parameters other than bearing capacity and settlement.

6. Summary of Findings and Recommendations

This study investigated the bearing capacity and settlement behaviours of CL and CH soils and focused on determining their relationships with various soil parameters through correlation analysis.

The results revealed a significant relationship between the bearing capacity of soil (ranging from 1.96 to 5.67 kgf/cm2 for CL soil and from 1,61 to 6.70 kgf/cm2 for CH soil).

The bearing capacity and settlement values of the CL and CH soils were estimated using multiple linear regression analysis, depending on other soil parameters, and moderate R2 values were found for both, as shown in the prediction models (See Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4).

It was observed that the bearing capacity and settlement values of the CH type soil were greater than those of the CL type soil (See Table 9). It was determined that there were significant differences between the CL type soil and the CH type soil in terms of the cohesion coefficient, the amount of soil passing the No. 200 sieve, the liquid limit, and the plastic limit values, and that there were no significant differences between these parameters (See Table 10).

According to these results, the soil parameters affecting the bearing capacity and settlement amount of the soil in terms of current engineering practices were expressed proportionally, and preliminary evaluations were made on how the bearing capacity and settlement amounts would be affected according to the soil parameters examined by the engineers. Moreover, it was shown which parameters have significant effects in which direction in gravel soils.

6.1. Accordingly, in CL Soil Type

When the relationships between bearing capacity and other parameters were examined, negative relationships were found between groundwater level, settlement, and the amount of soil passing through the number 10 sieve and bearing capacity.

Groundwater level was negatively correlated with bearing capacity at the 0.006 level of significance, with the amount of settlement at the 0.000 level of significance, and with the amount of soil passing through the number 10 sieve at the 0.004 level of significance. As these values increased, bearing capacity decreased.

While a negatively significant relationship was found between settlement and bearing capacity, no significant relationship was found between settlement and other parameters.

Positive relationships were found between the SPT-N30 value and the groundwater level at the 0.000 level of significance, negative relationships were found between the amount of soil passing through the number 200 sieve at the 0.000 level of significance, and positive relationships were found between the internal friction angle at the 0.031 level of significance.

Positive relationships were observed between unit weight and water content at the 0.005 level of significance, between the plastic limit at 0.004, and between the internal friction angle at 0.000. Negative relationships were observed between the amount of soil passing through sample number 10 and the cohesion coefficient at the 0.000 significance level.

Positive relationships were observed between water content and unit weight at the 0.005 significance level, between the plastic limit at 0.004 and the internal friction angle at 0.000. Negative relationships were observed between the amount of soil passing through sample number 10 and cohesion at 0.000.

While there was a negative relationship between the amount of soil passing through sample number 10 and the internal friction angle at 0.000, a positive relationship was found with cohesion at the 0.011 significance level.

A negative relationship was observed between the amount of soil passing through the 200 sieve and the groundwater level and raw SPT-N30 at 0.000, and a negative relationship was observed between the internal friction at 0.057. However, positive relationships were observed between the liquid limit and plastic limit at 0.000 and the cohesion coefficient at 0.017.

A negative relationship was observed between the liquid limit and the groundwater level at 0.023, and a positive relationship was observed between the amount of soil passing through the 200 sieve and the plastic limit at 0.000.

A negative relationship was observed between the plastic limit and the groundwater level at 0.002, and a positive relationship was observed between the soil passing through the 200 sieve and the liquid limit at 0.004.

Significant positive relationships were found between the angle of internal friction and excavation elevation, SPT-N30, unit weight, and water content, while significant negative relationships were found between the amount of soil passing through the No. 10 sieve and the cohesion coefficient.

Significant negative relationships were found between the cohesion coefficient and excavation elevation, unit weight, water content, and the angle of internal friction, while significant positive relationships were found between the amounts of soil passing through the No. 10 and No. 200 sieves.

6.2. Accordingly, in CH Soil Type

No significant relationship was found between the excavation elevation and other parameters.

Positive and significant relationships were found between the excavation elevation, unit weight, and water content, while a negative relationship was found with the amount of settlement.

A significant negative relationship (0.039) was found between settlement and bearing capacity, and a significant positive relationship was found between the plastic limit and SPT_N30.

A significant positive relationship was found between the SPT-N30 value and the groundwater level and settlement. However, a significant negative relationship was found between water content, the amount of soil passing through the 200 sieves, and the liquid limit.

A significant positive relationship was found between the unit weight and bearing capacity, while a significant negative relationship was found between the groundwater level and the amount of soil passing through the 10 sieves.

Positive relationships were observed between water content and bearing capacity, the amount of soil passing through the 200 sieves, and the liquid limit, while a negative relationship was observed between the groundwater level and SPT-N30.

Negative relationships were observed between the amount of soil passing through the 10 sieve and the unit weight and the amount of soil passing through the 200 sieves.

Significant positive relationships were observed between the amount of soil passing through the 200 sieve and the water content, liquid limit, and plastic limit. However, negative relationships were observed between the SPT-N30 value and the amount of soil passing through the 10 sieves.

Significant positive relationships were observed between the liquid limit water content, the amount of soil passing through the 200 sieves, and the plastic limit, while significant negative relationships were observed between the groundwater level and the SPTN-30.

Positive and significant relationships were observed between the plastic limit and slump, the amount of soil passing through the 200 sieves, and the liquid limit.

No significant relationship was found between the angle of internal friction and the other parameters.

No significant relationship was found between the cohesion coefficient and the other parameters.

Similar studies can be conducted for soils containing varying proportions of sand, clay, silt, and gravel. By examining the relationships between bearing capacity, settlement, and other parameters in these soil types from a multifaceted perspective, the parameters that increase or decrease the bearing capacity and settlement of these soils, as well as their respective impact levels, can be determined. Based on these relationships, the bearing capacity and settlement rates of naturally or artificially prepared soils can be estimated, and necessary precautions can be taken. Furthermore, compacting these soil types and achieving maximum dry unit weight are also considered important.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data was compiled from municipal databases and university laboratory data. Additionally, access to data from privately owned land surveys is not possible due to confidentiality or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Terzaghi, K.; Peck, R.B. Soil Mechanics in Engineering Practice, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1943. [Google Scholar]

- Terzaghi, K.; Peck, R.B.; Mesri, G. Soil Mechanics in Engineering Practice; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Vickers, B. Laboratory Work in Soil Mechanics (No. Monograph). 1983. Available online: https://trid.trb.org/View/205995 (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Coduto, D.P. Foundation Design: Principles and Practices, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, J.E.; Guo, Y. Foundation Analysis and Design; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1996; Volume 5, p. 127. [Google Scholar]

- Skempton, A.W. The Bearing Capacity of Clays. In Selected Papers on Soil Mechanics; Emerald Publishing: Leeds, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerhof, G. The Ultimate Bearing Capacity of Foundations; Geotechnique: Penrith, Australia, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerhof, G.G. Some Recent Research on the Bearing Capacity of Foundations. Can. Geotech. J. 1963, 1, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulhawy, F.H.; Mayne, P.W. Manual on Estimating Soil Properties for Foundation Design. EL-6800, Project 1493-6; Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI): Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1990.

- Kaliakin, V. Soil Mechanics: Calculations, Principles, and Methods; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Peck, R.B.; Hanson, W.E.; Thornburn, T.H. Foundation Engineering, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Das, M.B. Principle of Geotechnical Engineering, 7th ed.; Cengage Learning: Stamford, CT, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Briaud, J.L. Geotechnical Engin: Unsaturated and Saturated Soils; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Das, B.M.; Sivakugan, N. Fundamentals of Geotechnical Engineering; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Prandtl, L. Bemerkungen über die Entstehung der Turbulenz. ZAMM-J. Appl. Math. Mech./Z. Angew. Math. Und Mech. 1921, 1, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbasar, V.; Kip, F. Zemin Mekaniği Problemleri; Çağlayan Kitabevi: Istanbul, Turkey, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lambe, T.W.; Whitman, R.V. Soil Mechanics SI Version Soil Mechanics in Engineering Practice, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Brinch Hansen, J. A Revised and Extended Formula for Bearing Capacity; Bulletin of the Danish Geotechnical Institute: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Vesic, A.S. Analysis of Ultimate Loads of Shallow Foundations. ASCE J. Soil Mech. Found. Div. 1973, 99, 45–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzuner, B.A. Temel Zemin Mekaniği; Derya Kitabevi: Trabzon, Turkey, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Burland, J.B.; Burbidge, M.C.; Wilson, E.J.; Terzaghi. Settlement of foundations on sand and gravel. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. 1985, 78, 1325–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, R.; Das, S.K. Settlement of shallow foundations on cohesionless soils based on SPT value using multi-objective feature selection. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2018, 36, 3499–3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, R.F. New method of consolidation–coefficient evaluation. J. Soil Mech. Found. Div. 1961, 87, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntohar, A.S. Reliability of the Method for Determination of Coefficient of Consolidation (cv). In Proceedings of the 13rd Annual Scientific Meeting Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia, 5–6 November 2009; Volume 5, p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mesri, G.; Feng, T.W. Constant rate of strain consolidation testing of soft clays and fibrous peats. Can. Geotech. J. 2019, 56, 1526–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manou, D.; Manakou, M.; Alexoudi, M.; Anastasiadis, A.; Pitilakis, K. Microzonation Study of Düzce, Turkey. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Recent Advances in Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering and Soil Dynamics and Symposium in Honor of Professor Izzat M. Idriss, San Diego, CA, USA, 24–29 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Holtz, R.D.; Kovacs, W.D.; Sheahan, T.C. An Introduction to Geotechnical Engineering; Prentice-hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1981; Volume 733. [Google Scholar]

- Güner, A.B.S.; Özgan, E. Statistical Analysis of Soil Parameters Affecting the Bearing Capacity and Settlement Behaviour of Gravel Soils. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TS EN ISO 17892-9; Geoteknik Araştırma Deney—Zeminler Için Laboratuvar Deneyleri. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/doc/58389693/TS-1900-12018 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Düzce Haritası. Available online: https://www.harita.gen.tr/81-duzce-haritasi/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Rourke, T.D.; Goh, S.H.; Menkiti, C.O.; Mair, R.J. Highway tunnel performance during the 1999 Duzce earthquake. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering (ICSMGE), Istanbul, Turkey, 27–31 August 2001; A.A. Balkema Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2002; Volume 2, pp. 1365–1368, ISBN 975-7180-06-8. [Google Scholar]

- Karadeniz, E.; Sunbul, F. Land Use and Land Cover Change in Duzce Region Following the Major Earthquake: Implications for ANN and Markov Chain Analysis. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emre, Ö. vd. (MTA), Varol, B. vd. (A.Ü.). 17 Ağustos 1999 Depremi Sonrası Düzce (Bolu) İlçesi Alternatif Yerleşim Alanlarının Jeolojik İncelemesi. TÜBİTAK (MTA Genel Müdürlüğü ve A.Ü. Ortak Araştırma Projesi). 1999. Available online: https://kutuphane.tbmm.gov.tr/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=263787&shelfbrowse_itemnumber=253416 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Özmen, B. Düzce-Bolu Bölgesi’nin Jeolojisi, Diri Fayları ve Hasar Yapan Depremleri s:1–14, 12 Kasım 1999 Düzce Depremi Raporu; Özmen, B., Bağcı, G., Eds.; Bayındırlık ve İskan Bakanlığı Afet İşleri Genel Müdürlüğü, Deprem Araştırma Dairesi: Ankara, Turkey, 2000.

- Yousefi-Bavil, K.; Koçkar, M.K.; Akgün, H. Development of a three-dimensional basin model to evaluate the site effects in the tectonically active near-fault region of Gölyaka basin, Düzce, Turkey. Nat. Hazards 2022, 114, 941–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasal, M.E.; Iyisan, R.; Yamanaka, H. Basin edge effect on seismic ground response: A parametric study for Duzce basin case, Turkey. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2018, 43, 2069–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lettis, W.; Barka, A. Geologic characterization of fault rupture hazard, Gumusova—Gerede Motorway. In Report Prepared for the Astaldi-Bayindir Joint Venture Turkey; Astaldi: Bolu, Turkey, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Şengör, A.M.C.; Yılmaz, Y. Tethyan evolution of Turkey: A plate tectonic approach. Tectonophysics 1981, 75, 181–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulutaş, E.; Coruk, Ö.; Karakaş, A. Local Geology Effects on Soil Amplification and Predominant Period in Düzce Basin, NW Turkey. Kocaeli J. Sci. Eng. 2000, 4, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocbay, A.; Orhan, T.; Culshaw, M.G.; Reeves, H.J.; Jefferson, I.; Spink, T.W. Geotechnical properties and the liquefaction potential of the soils around Efteni Lake (Düzce, Turkey). In Engineering Geology for Tomorrow’s Cities; Engineering Geology Special Publications; Geological Society: London, UK, 2009; Volume 22. [Google Scholar]

- Yousefi-Bavil, K.; Koçkar, M.K.; Akgün, H. Development of A 3-D Topographical Basin Structure Based on Seismic and Geotechnical Data: Case Study at a High Seismicity Area of Gölyaka, Düzce, Turkey. In Proceedings of the 16th European Conference on Earthquake Engineering (16ECEE), Thessaloniki, Greece, 18–21 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Şimşek, O.; Dalgiç, S. Düzce Ovası killerinin konsolidasyon özellikleri ve jeolojik evrim ile ilişkisi. Geol. Bull. Turk 1997, 40, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Khanbabazadeh, H.; Hasal, M.E.; Iyisan, R. 2D seismic response of the Duzce Basin, Turkey. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2019, 125, 105754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, T.; Tank, S.B.; Tunçer, M.K.; Rokoityansky, I.I.; Tolak, E.; Savchenko, T. Asperity along the North Anatolian Fault imaged by magnetotellurics at Düzce, Turkey. Earth Planets Space 2009, 61, 871–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tigli, C.S.; Ates, A.; Aydemir, A. Geophysical investigations on the gravity and aeromagnetic anomalies of the region between Sapanca and Duzce, along the North Anatolian Fault, Turkey. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 2012, 212, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tank, S.B. Fault zone conductors in Northwest Turkey inferred from audio frequency magnetotellurics. Earth Planets Space 2012, 64, 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabulut, H.; Schmittbuhl, J.; Lengline, O.; Bouchen, M. Seismicity distribution and locking depth along the Main Marmara Fault, Turkey. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst 2016, 17, 954–965. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Garzón, P.; Becker, D.; Jara, J.; Chen, X.; Kwiatek, G.; Bohnhoff, M. The 2022 M W 6.0 Gölyaka–Düzce earthquake: An example of a medium-sized earthquake in a fault zone early in its seismic cycle. Solid Earth 2023, 14, 1103–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şengör, A.M.C.; Tüysüz, O.; Imren, C.; Sakınç, M.; Eyidoğan, H.; Görür, N.; Le Pichon, X.; Rangin, C. The North Anatolian fault: A new look. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2005, 33, 37–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouin, M.P.; Bouchon, M.; Karabulut, H.; Aktar, M. Rupture process of the 1999 November 12 Düzce (Turkey) earthquake deduced from strong motion and Global Positioning System measurements. Geophys. J. Int. 2004, 159, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimzadeh, S.; Askan, A.; Yakut, A. Assessment of Simulated Ground Motions in Earthquake Engineering Practice: A Case Study for Duzce (Turkey). Pure Appl. Geophys. 2017, 174, 3589–3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, V.G. A Case Study: Site-Specific Seismic Response Analysis for Base-Isolated Building in Düzce. Master’s Thesis, Izmir Institute of Technology, Urla, Turkey, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ambraseys, N.N.; Finkel, C.F. Long-term seismicity of Istanbul and of the Marmara Sea region. Terra Nova 1991, 3, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambraseys, N.N. The little-known earthquakes of 1866 and 1916 in Anatolia (Turkey). J. Seismol. 1997, 1, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyu, H.S.; Hartleb, R.; Barka, A.; Altunel, E.; Sunal, G.; Meyer, B.; Armijo, R. Surface rupture and slip distribution of the 12 November 1999 Duzce earthquake (M 7.1), North Anatolian fault, Bolu, Turkey. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2002, 92, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utkucu, M.; Nalban, S.S.; McCloskey, J.; Steacy, S.; Alptekin, Ö. Slip distribution and stress changes associated with the 1999 November 12, Düzce (Turkey) earthquake (Mw = 7.1). Geophys. J. Int. 2003, 153, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniraj, S.R. Design Aids in Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering; Tata McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero, O.R. Universal compression index equation; Closure. ASCE J. Geotech. Eng. 1983, 109, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačević, M.S.; Jurić-Kaćunić, D.; Librić, L.; Ivoš, G. Engineering soil classification according to EN ISO 14688-2:2018. Gradevinar 2018, 70, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniji, M.A. Investigating the Influence of Soil Properties on Foundation Settlement and Bearing Capacity. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Technology, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, Ogbomosho, Nigeria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kayser, M.; Gajan, S. Application of probabilistic methods to characterize soil variability and their effects on bearing capacity and settlement of shallow foundations: State of the art. Int. J. Geotech. Eng. 2014, 8, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzouz, A.S.; Krizek, R.J.; Corotis, R.B. Regression analysis of soil compressibility. Soils Found. 1976, 16, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambraseys, N.N.; Finkel, C. The Seismicity of Turkey and Adjacent Areas: A Historical Review, 1500–1800; Eren: Beyoğlu, İstanbul, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Barka, A. Slip distribution along the North Anatolian fault associated with the large earthquakes of the period 1939 to 1967. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 1996, 86, 1238–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barka, A.A.; Kadinsky-Cade, K. Strike-slip fault geometry in Turkey and its influence on earthquake activity. Tectonics 1988, 7, 663–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şaroğlu, F.; Emre, Ö.; Kuşçu, İ. Türkiye Diri Fay Haritası; MTA Genel Müd.: Ankara, Turkey, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Şengör, A.M.C.; Görür, N.; Şaroğlu, F. Strike Slip Faulting and Related Basin Formations in Zones of Tectonic Escape: Turkey as a Case Study; Biddle, K.T., Christie Blick, N., Eds.; Strike-Slip Faulting and Basin Formation; Special Publication; Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1985; pp. 227–264. [Google Scholar]

- Gurbuz, C.; Aktar, M.; Eyidogan, H.; Cisternas, A.; Haessler, H.; Barka, A.; Ergin, M.; Türkelli, N.; Polat, O.R.; Üçer, S.B.; et al. The seismotectonics of the Marmara region (Turkey): Results from a microseismic experiment. Tectonophysics 2020, 316, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucci, S.; Pantosti, D.; Barchi, M.R.; Palyvos, N. A complex seismogenic shear zone: The Düzce segment of North Anatolian Fault (Turkey). Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2007, 262, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emre, Ö.; Duman, T.Y.; Özalp, S.; Şaroğlu, F.; Olgun, Ş.; Elmacı, H.; Çan, T. Active fault database of Turkey. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2018, 16, 3229–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şengör, A.C.; Grall, C.; Imren, C.; Le Pichon, X.; Şengör, A.C.; Grall, C.; Imren, C.; Le Pichon, X.; Görür, N.; Henry, P.; et al. The geometry of the North Anatolian transform fault in the Sea of Marmara and its temporal evolution: Implications for the development of intracontinental transform faults. Can. J. Earth Sci. 2014, 51, 222–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayhan, M.E.; Koçyiğit, A. Displacements and Kinematics of the February 1, 1944 Gerede Earthquake (North Anatolian Fault System, Turkey): Geodetic and Geological Constraints. Turk. J. Earth Sci. 2010, 19, 285–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barka, A.; Akyu, H.S.; Altunel, E.; Sunal, G.; Çakir, Z.; Dikbas, A.; Yerli, B.; Armijo, R.; Meyer, B.; de Chabalier, J.B.; et al. The surface rupture and slip distribution of the 17 August 1999 Izmit earthquake (M 7.4), North Anatolian fault. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2002, 92, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, T.; Murty, B.R.S. Prediction of the preconsolidation pressure and recompression index of soils. Geotech. Test. J. 1985, 8, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SPSS Statistics, version 22 ed; IBM: Armonk, NY, USA, 2020.

- Örnek, M.; Laman, M.; Demir, A.; Yildiz, A. Prediction of bearing capacity of circular footings on soft clay stabilized with granular soil. Soils Found. 2012, 52, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerhof, G.G. Ultimate Bearing Capacity of Footings on Sand Layer Overlying Clay. Can. Geotech. J. 1974, 11, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.; Shanableh, A.; Hamad, K.; Tahmaz, A.; Arab, M.G.; Al-Sadoon, Z. Nomographs for predicting allowable bearing capacity and elastic settlement of shallow foundation on granular soil. Arab. J. Geosci. 2019, 12, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M. Practice in Geotechnical and Foundation Engineering. In Geotechnical and Foundation Engineering Practice in Industrial Projects; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 295–303. [Google Scholar]

- Darga, K.N. Evaluation of coefficient of consolidation in CH soils. Jordan J. Civ. Eng. 2016, 4, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Sivrikaya, O.; Togrol, E. Relations between SPT-N and qu. In Proceedings of the 5th International Congress on Advances in Civil Engineering, Istanbul, Turkey, 25–27 September 2002; pp. 943–952. [Google Scholar]

- Burmister, D.M. Identification and Classification of Soil: An Appraisal and Statement of Principles; ASTM STP 113; American Society for Testing and Materials: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D2435/D2435M; Standard Test Methods for One-Dimensional Consolidation Properties of Soils Using Incremental Loading. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2025.

- TS 1900 EN ISO 17892-5; İnşaat Mühendisliğinde Zemin Laboratuvar Deneyleri—Bölüm 2-Mekanik Özelliklerin Tayini Konsolidasyon Özelliklerinin Tayini. Türk Standartları Enstitüsü: Ankara, Turkey, 2006.

- TS 1500:2000; İnşaat Mühendisliğinde Zeminlerin Sınıflandırılması. Türk Standartları Enstitüsü: Ankara, Turkey, 2000.

- Unified Soil Classification System (USCS). Available online: https://dot.ca.gov/-/media/dot-media/programs/maintenance/documents/office-of-concrete-pavement/pavement-foundations/uscs-a11y.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- ASTM D4767; Standard Test Method for Consolidated Undrained Triaxial Compression Test for Cohesive Soils. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1988.

- ASTM D2850; Standard Test Method for Unconsolidated-Undrained Triaxial Compression Test on Cohesive Soils. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1970.

- TS EN ISO 17892-9; Geoteknik araştırma deney—Zeminler için laboratuvar deneyleri—Bölüm 9: Üç eksenli sıkıştırma deneyi. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.