Abstract

Considering the complexity and hazardous nature of construction jobsites, selecting the effective safety risk control strategies is crucial to prevent accidents, protect labor crews, and achieve project objectives related to cost, schedule, and quality in the construction project. However, the evaluation of different safety strategies involves multiple conflicting criteria and uncertain expert judgments, making it a complex multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) problem. To address this problem, this study develops a fuzzy-integrated MCDM framework that combines two methods: Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process (FAHP), which systematically captures the relative importance of safety criteria under uncertainty, and ELECTRE III, which ranks alternative strategies by modeling preferences and veto conditions, reflecting real-world “non-compensatory” safety logic. FAHP determines criterion weights based on expert judgments, while ELECTRE III evaluates and ranks alternative safety strategies. The framework is validated through a piping construction case study, where it successfully identified the optimal safety plan. A sensitivity analysis is conducted to confirm the robustness of results, and comparative tests with other MCDM methods further support its reliability. Therefore, the proposed fuzzy-integrated framework offers an effective approach for evaluating safety risk control strategies, enhancing both safety and overall project performance, and advancing systematic safety management in the construction industry.

1. Introduction

As the construction jobsites are complex and hazardous, managing safety risks remains a critical challenge in the construction industry [1]. Effective safety risk control is essential not only for preventing accidents and protecting labor crews but also for achieving key project objectives related to cost, schedule, and quality [2]. In practice, project managers should consider a range of potential safety strategies, including personal protective equipment (PPE), advanced monitoring technologies, safety training programs, and temporary facility layouts [3,4]. Identifying the optimal safety strategy is therefore critical to establishing a reliable safety management system that ensures workforce protection throughout the construction process.

Evaluating safety risk control strategies remains challenging due to the multiple conflicting criteria and the uncertainty of expert judgments. For example, a strategy with superior safety performance, such as advanced harness systems or real-time monitoring equipment, may result in high costs, while a cost-effective alternative might compromise safety reliability. These trade-offs result in a complex multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) problem. Moreover, decision-making information is often imprecise and expressed in linguistic terms, relying on subjective expert judgements [5]. This challenge is compounded when selecting from a portfolio of combined strategies, such as integrating personal fall arrest systems for specific hazards like working at height with VR-based programs for general safety awareness. Despite the growing use of MCDM methods in construction safety, there still lacks a systematic approach to evaluate the combined safety strategies across heterogeneous site scenarios while simultaneously handling uncertain expert judgments and outranking-specific requirements, such as indifference, preference, and veto thresholds, that are essential for realistically modeling trade-offs in safety decision-making for construction projects.

To address this specific challenge, this study proposes a fuzzy-integrated MCDM framework for evaluating various combined safety strategies. The framework is designed to incorporate imprecise expert judgments and model critical outranking relationships across multiple safety-related requirements. Its feasibility and practical utility are demonstrated through a piping construction case study, providing project managers with a robust decision-support tool for enhancing safety planning and overall project performance.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Safety Risk Control in Construction Projects

The construction industry remains one of the most hazardous industries due to its complex and dynamic work environment [1]. The interaction of multiple trades, temporary structures, and dynamic work flows generates various safety risks [6]. Among all accident types, fall from height account for the majority of fatalities [7]. As the complexity of construction projects increases, the risk factors tend to interact in a coupled manner, forming a dynamically interdependent risk system instead of discrete and independent hazards.

Recent research has focused on enhancing construction safety performance through engineering and technological approaches, including the optimization and performance evaluation of scaffolding, formwork, and temporary supports in complex construction environments. For example, Jin and Goodrum [8] developed a knowledge-based decision-support framework that optimizes scaffolding planning by integrating technical evaluation and expert knowledge to enhance site safety, productivity, and cost efficiency. To improve labor productivity, safety performance and cost efficiency, Jin et al. [9] established a simulation-based multi-objective optimization approach for scaffolding space planning in industrial piping projects through optimal planning of resource allocation. Li et al. [10] proposed a hybrid CREAM-fuzzy-Bayesian framework to assess human reliability in scaffolding operations, identifying key factors influencing human error and providing insights for improving safety in work-at-height activities. In addition, Ojha et al. [11] systematically reviewed construction safety training methods, showing that immersive, environment-based training is more effective than traditional approaches in improving workers’ risk awareness and safety performance. Therefore, the studies highlight the critical role of integrated technical, human, and training-focused strategies to advance construction safety management.

Meanwhile, computer vision and automation technologies have facilitated the development of proactive approaches for hazard identification and monitoring. Deep learning algorithms trained on on-site video feeds can now recognize unsafe behaviors, unstable configurations, or missing safety gear with high accuracy. For instance, Khan et al. [12] proposed a smart safety hook system integrating computer vision with IoT-based monitoring to automatically detect and alert on fall-from-height risks on scaffolding, achieving over 98% accuracy across multiple real-time scenarios and reducing the manual workload of site managers. Building on sensor-based monitoring, Hong et al. [13] employed a Gramian angular field-based convolutional neural network using IMU data to automatically classify scaffolding workers’ compliance with safety regulations, demonstrating the feasibility of real-time, personalized safety management and training. Khan et al. [14] proposed a correlation-based mobile scaffold monitoring framework using Mask R-CNN combined with an object correlation detection module to identify workers’ unsafe behaviors, achieving an overall accuracy of 86% and demonstrating effective detection of both safe and unsafe actions in dynamic construction environments. The advanced methods demonstrate the potential of integrated computer vision and sensor-based systems for real-time, automated safety monitoring in construction.

Therefore, previous studies emphasize the critical role of engineering, technological, and human-centered interventions in enhancing construction safety performance. These approaches include optimization and performance evaluation of scaffolding and temporary supports, knowledge-based decision-support frameworks, human reliability assessment, immersive safety training, and computer vision-based real-time monitoring systems. While these strategies demonstrate significant potential in identifying hazards and improving safety management, most studies primarily focus on individual aspects of safety and lack a comprehensive, multi-criteria evaluation of alternative safety strategies. Furthermore, the decision-making process often involves multiple expert judgments, which are inherently uncertain and imprecise. These gaps highlight the need for systematic, multi-criteria decision-making approaches capable of integrating technical, human, and organizational factors to support effective safety risk control in construction projects.

2.2. Fuzzy Multi-Criteria Decision-Making in Construction Safety Management

Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) approaches have been widely applied in construction management to support performance evaluation and optimization under conflicting objectives [15,16,17]. In safety management, decision-making typically involves multiple experts, including site managers, engineers, and stakeholders, whose assessments are inherently subjective and uncertain. Consequently, traditional MCDM methods relying on crisp values may fail to adequately capture the ambiguity of expert judgments. To address this limitation, fuzzy set theory (FST) has been integrated into MCDM, enabling the representation of imprecise and qualitative information through linguistic variables and fuzzy numbers [18,19,20,21].

Fuzzy MCDM methods, such as Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), Fuzzy TOPSIS, and Fuzzy VIKOR, have demonstrated effectiveness in construction-related applications including site layout planning, risk assessment, and resource allocation [18,19,20,21]. By incorporating fuzzy logic, these approaches can better synthesize divergent expert opinions, quantify uncertainty, and provide a more realistic basis for evaluating alternative strategies. However, most existing fuzzy-MCDM applications in construction safety employ fully compensatory aggregation, which permits trade-offs that may be unacceptable in high-risk contexts. For example, a severe safety deficiency could be mathematically offset by superior performance on other criteria, undermining practical applicability in life-critical decisions. This limitation motivates the need for integrated approaches that combine fuzzy weighting with non-compensatory decision logic.

2.3. Fuzzy AHP and ELECTRE III in Construction Management

Effective evaluation of construction safety control strategies requires an MCDM method capable of (1) generating reliable criterion weights from uncertain expert judgments and (2) modeling non-compensatory trade-offs that reflect the real-world safety constraints. This section provides a focused review of Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process (FAHP) and ELECTRE III in construction management and justifies their integrated use in the present study.

2.3.1. Fuzzy AHP for Robust Criterion Weighting Under Uncertainty

The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) is widely used for structuring complex decisions, yet its dependence on crisp pairwise comparisons limits its ability to represent uncertainty inherent in human judgment [22]. Fuzzy AHP (FAHP) integrates fuzzy set theory to express expert preferences using linguistic terms (e.g., “moderately more important”) mapped to triangular fuzzy numbers (TFNs), enabling more realistic modeling of ambiguity [23]. In construction safety, judgments concerning risk likelihood, severity, or the relative effectiveness of interventions are qualitative and often imprecise. FAHP has therefore been increasingly adopted to handle expert uncertainty.

Recent studies in construction management have demonstrated FAHP’s efficacy in handling such uncertainty. Ji et al. [24] proposed an improved FAHP-based factor analysis method to identify and weight dynamic safety risk sources during the construction of large and complex bridges. Zhao et al. [25] developed an operational safety risk assessment method for long and large highway tunnels based on FAHP, demonstrating greater rationality and accuracy compared to traditional AHP evaluations. Liu et al. [26] developed a combined weighting FAHP model to assess deep excavation construction risks, which improve the accuracy and reliability over traditional FAHP methods. The studies show that FAHP provides a reliable mechanism for deriving criterion weights under uncertainty. Furthermore, triangular fuzzy numbers (TFNs) are used in this study due to their interpretability and computational efficiency relative to trapezoidal or intuitionistic fuzzy sets, which offer higher complexity without significant gains in accuracy for pairwise comparisons.

2.3.2. ELECTRE III for Modeling Non-Compensatory Trade-Offs and Threshold-Based Preferences

ELECTRE III is an outranking method designed to handle imperfect and non-compensatory criteria [27]. For each criterion, it models decision-maker preferences via indifference (q), preference (p), and critical veto (v) thresholds. The indifference threshold defines the maximum performance difference deemed negligible; the preference threshold defines the minimum difference that establishes a clear preference; and the critical veto threshold defines a performance gap so severe that it can veto the outranking of one alternative by another, regardless of performance on other criteria [28].

This threshold system, particularly the veto threshold, enables ELECTRE III to explicitly represent non-compensatory relationships among safety criteria. In construction safety, a critical deficiency in one aspect (e.g., fall protection reliability) cannot be offset by superior performance in other criteria (e.g., cost efficiency or reduced training duration). Prior applications in construction illustrate the method’s capacity to manage such trade-offs. Pepple and Ikeremo [29] applied ELECTRE III for stock selection, demonstrating that ELECTRE III with a veto threshold effectively excludes alternatives failing critical criteria, ensuring robust decision-making across multiple performance, technical, and fundamental metrics, where a single poor-performing metric cannot be compensated by strong performance in other criteria. Kim et al. [30] used ELECTRE III to prioritize collaboration and integration strategies in construction, handling non-compensatory trade-offs where a critical risk (e.g., construction risk) could not be offset by strengths in other areas (e.g., financial or environmental risk).

2.3.3. Justification and Framework Novelty

Although integrated FAHP-ELECTRE III models exist in construction management, a systematic review reveals a specific methodological gap in safety planning: prior studies have not applied this integrated framework to the evaluation of construction safety control strategies, and crucially, they do not leverage the veto threshold of ELECTRE III to explicitly model the non-compensatory logic essential for safety-critical decisions. Concurrently, the dominant fuzzy-MCDM models in safety research (e.g., FAHP-TOPSIS, FAHP-VIKOR) are fully compensatory, permitting mathematically possible but practically unacceptable trade-offs where a severe safety flaw is offset by other benefits [31,32].

To address this gap, this study integrates FAHP for fuzzy weighting with ELECTRE III for threshold-based outranking, ensuring that a single critical safety deficiency can exclude a strategy even if other criteria are satisfied. The following research questions guide the study:

RQ1: How can uncertain, multi-expert judgments be synthesized into reliable criterion weights for evaluating construction safety control strategies?

RQ2: How can threshold-based, non-compensatory relationships, particularly safety veto conditions, be incorporated into safety decision modeling?

RQ3: How can a fuzzy-weighted outranking framework (FAHP–ELECTRE III) be constructed to generate rankings of safety control strategies under conflicting criteria?

Table 1 provides a comparative analysis of multiple MCDM integrations, highlighting their suitability for safety decisions.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of MCDM method integrations for safety strategy evaluation.

As shown in Table 1, the novelty and justification of the proposed FAHP-ELECTRE III integrated framework does not lie simply in combining two established methods. The major contribution is applying this specific combination to address a methodological gap in construction safety strategy evaluation, while most existing approaches rely on fully compensatory models, which cannot represent the non-negotiable constraints that exist in real safety management. FAHP is used to obtain criterion weights based on fuzzy expert judgments, and ELECTRE III applies these weights, together with preference and veto thresholds that reflect safety requirements, to perform pairwise outranking. This procedure ensures that a single critical weakness can exclude a strategy even if it performs well on other criteria. The integrated framework therefore produces a decision-support tool that handles subjective uncertainty and enforces the logic of risk control, offering more reliable and practical rankings of safety strategies than using either method alone or simple hybrids.

This research makes three contributions to the construction-safety MCDM literature: (1) It develops the FAHP–ELECTRE III framework to safety control strategy evaluation, integrating fuzzy uncertainty handling with veto-based non-compensation. (2) It introduces a safety-specific hierarchical structure grounded in hazard-control logic, operationalized through fuzzy weights and ELECTRE III thresholds. (3) It applies the model to piping construction, a high-risk domain with limited MCDM-based safety studies, providing actionable prioritization of safety strategies.

3. Research Methodology

This study develops a fuzzy-integrated multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) framework to evaluate safety risk control strategies in construction projects. As shown in Figure 1, the framework consists of fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process evaluation, multi-criteria performance assessment based on ELECTRE III and sensitivity validation.

Figure 1.

Research framework for optimal identification of safety risk control strategies.

The methodology consists of three phases. In the first phase, a hierarchical structure of safety performance criteria is designed to incorporate the key elements of construction management. The fuzzy AHP is then applied to determine the relative importance of each criterion. By incorporating expert judgment through fuzzy linguistic variables, this approach effectively addresses the uncertainty and subjectivity in construction safety-related decision-making processes.

In the second phase, the ELECTRE III method is utilized to evaluate and compare the performance of alternative safety management plans. By integrating both qualitative and quantitative indicators, ELECTRE III produces a comparative ranking that reflects the overall effectiveness of each alternative in controlling construction safety risks.

The third phase involves a sensitivity analysis to assess the robustness and stability of the ranking results. Additional comparative analyses are conducted using other MCDM methods, including MAVT, TOPSIS, and VIKOR, to verity the consistency and reliability of the proposed framework.

By integrating fuzzy AHP to model expert judgment and employing ELECTRE III to handle the assessment of multiple criteria, the proposed framework provides a systematic tool for evaluating safety strategies in complex construction environments. This approach explicitly addresses uncertainty and subjectivity, thereby improving the effectiveness and accuracy of the decision-making process and supporting the identification of robust safety management plans.

3.1. Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Model

This study develops an MCDM model to systematically evaluate safety risk control performance in construction projects. The model is established based on a systematic analysis of relevant literature and practical safety management requirements, forming a two-level hierarchical structure of evaluation criteria, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Hierarchy structure of criteria and sub-criteria.

The first level of the hierarchy comprises four main criteria, each representing a fundamental dimension of safety risk control: Personal Safety Equipment (C1) [35,36], Procedure Safety Management (C2) [35,36,37], Temporary Facility (C3) [36,37,38], and Cost (C4) [36,37,38]. These are further defined at the second level through a set of specific sub-criteria representing the key attributes. Under C1 criterion, the focus is placed on equipment ergonomics and human factors, characterized by the sub-criteria of wearing comfort (C11) [35,39,40], fall prevention performance (C12) [35,41,42,43,44,45], and human behavior consideration (C13) [35,36,41]. C2 criterion represents the organizational and procedural robustness, evaluated through inspection measures (C21) [35,37,38,42,44,46], real-time monitoring (C22) [35,37,38,46], adequate plan review (C23) [36,37,38,45,46], sufficient training (C24) [37,41,42,44,46], and communication among stakeholders (C25) [37,41,42]. C3 criterion refers to the physical configuration and structural integrity of on-site installations, defined by site layout planning (C31) [36,37,38,45], proper placement (C32) [36,37,38,43,44], and sufficient foundational strength (C33) [37]. Lastly, C4 criterion addresses economic considerations, evaluated through indicators such as installation efficiency (C41) [36,37,38,43,44,45], rental cost savings (C42) [44,45], maintenance cost-effectiveness (C43) [44], and facility dismantling rate (C44) [36,38,43,44]. Overall, this hierarchical structure provides a foundation for integrating expert judgment and quantitative assessment within a fuzzy-integrated MCDM methodology. It enables a comparison of alternative safety strategies, thereby supporting the identification of an evidence-based and optimally effective safety risk control plan for construction projects.

3.2. Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process Evaluation

The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), proposed by Saaty [47], provides a structured methodology for addressing MCDM problems by decomposing complex issues into hierarchical components. This approach enables systematic evaluation of the relative importance among various criteria through pairwise comparisons, where decision-makers indicate their preferences between criteria pairs. These judgments are subsequently synthesized to determine criterion weights. However, in real-world construction conditions, expert assessments are often characterized by ambiguity, uncertainty, and subjectivity. Limitations that the conventional AHP method is not fully designed to accommodate.

To address the challenges above, this study employs the fuzzy AHP, which incorporates fuzzy set theory [48,49] into the AHP approach. By utilizing triangular fuzzy numbers (TFNs) to represent linguistic expressions, Fuzzy AHP effectively transforms qualitative judgments into quantifiable measures. A TFN is defined by a triplet (l, m, u), where l denotes the lower bound, m the most possible value, and u the upper bound, as expressed in Equation (1). The membership function of a TFN, illustrated in Figure 3, ranges between 0 and 1, reflecting the degree of certainty associated with each judgment and offering a mathematical mechanism for handling evaluative uncertainty.

where l indicates the lower boundary, u the upper boundary, and m the most possible value. Thus, a TFN can be expressed as (l, m, u).

Figure 3.

The membership of the fuzzy number.

The fuzzy AHP methodology applied in this research can be summarized through four steps, which ensure both the integration of expert knowledge and the robustness of derived weights:

Step 1: Establish the linguistic scales. Qualitative judgments provided by experts, such as “equally important,” “moderately important,” and “very strongly important”, are converted into TFNs. Table 2 illustrates the mapping between linguistic expressions and their corresponding triangular fuzzy numbers.

Table 2.

Linguistic scales and their triangular fuzzy representations.

Step 2: Construct the fuzzy pairwise comparison matrix. Each pair of criteria is assessed through TFNs to reflect their relative importance. When a criterion is compared with itself, the TFN (1, 1, 1) is assigned. For all other comparisons, reciprocal fuzzy numbers are used to preserve consistency and maintain the logical structure of the matrix.

Step 3: Verify the consistency and assess group consensus. Although fuzzy logic accommodates uncertainty, it remains crucial to verify that expert judgments are logically consistent. The Consistency Ratio (CR), computed using the largest eigenvalue (λmax), the consistency index (CI), and the random index (RI), serves as a standard metric to assess the rationality of the comparisons (Table 3). If the CR is below the conventional threshold of 0.10, the matrix is considered acceptably consistent.

where n denotes the number of criteria or elements being compared, λmax represents the maximum eigenvalue of the fuzzy matrix, and RI corresponds to the random index values.

Table 3.

Values of random index (RI).

To further quantify the agreement among the experts, the Coefficient of Variation (CV) was calculated. For each pairwise comparison between criterion i and j, the CV was calculated based on the most probable values (m) of the triangular fuzzy numbers.

where and denotes the standard deviation and mean of m values provided by the experts, respectively.

A lower CV indicates a higher level of consensus. A threshold of CV ≤ 0.25 was adopted based on common practice in group decision-making studies [50,51]. When the initial CV for a comparison exceeded 0.25, a structured feedback round was conducted. The experts involved were anonymously informed of the group mean and distribution of responses and were invited to reconsider their judgment. This process was iterated until the CV for all comparisons fell below the threshold, ensuring a stabilized and consensual set of group judgments.

Step 4: Compute the fuzzy weights. The fuzzy comparison matrix is normalized, and the weights for criteria and sub-criteria are computed. Normalization ensures that the total of all fuzzy weights equals one.

where .

Step 5: Express the normalized fuzzy matrix. The weights of the criteria are assessed as Equation (6).

Through this approach, fuzzy AHP allows expert opinions to be systematically incorporated under uncertainty, providing a robust and reliable set of weights for evaluating criteria and sub-criteria in construction safety risk management.

3.3. Multi-Criteria Performance Assessment Based on ELECTRE III

ELECTRE III is an outranking-based method for MCDM problems that incorporates the concept of pseudo-criteria to account for uncertainty and imprecision in preferences as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

ELECTRE III decision-making process.

In this framework, the concordance index cj(i,k) quantifies the extent to which an alternative ai is at least as good as another alternative ak with respect to criterion j. This index is calculated using two thresholds: the indifference threshold (qj), defining the range within which two alternatives are considered equivalent, and the preference threshold (pj), beyond which one alternative is strictly preferred over the other. Mathematically, the concordance index is expressed as:

where qj and pj deonote the indifference and preference threshold, respectively [28].

To evaluate the overall preference, the global concordance index C(i,k), aggregates the partial concordance indices across all criteria, providing a comprehensive measure of the extent to which ai outranks ak, in Equation (8).

ELECTRE III further introduces a veto threshold (vj) to account for cases where a significant disadvantage on a single criterion can invalidate the overall preference. Based on this threshold, the discordance index dj(i,k) is defined to reflect the degree to which alternative ak strongly outperforms ai on criterion j. The discordance matrix is then constructed as Equation (9).

By integrating concordance and discordance information, ELECTRE III computes the outranking relation S(i,k), representing the overall degree to which ai outranks ak, as shown in Equations (10) and (11).

Finally, to determine the ranking of all alternatives, the net credibility score is employed, which synthesizes the pairwise outranking values. The net score for each alternative ai is calculated by:

where represents the overall priority of alternative ai. A high value of indicates a stronger outranking credibility and, consequently, a higher position in the final ranking.

To avoid ambiguity, all sub-criteria were defined and linked to measurable attributes. For each alternative strategy, the performance of each alternative against all sub-criteria was evaluated by experts using a 1–9 rating scale, where 1 represents low performance and 9 represents high performance. These ratings were derived from a comparative analysis of the strategies, supported by the experts’ professional experience and knowledge of industry practices. To enhance the reliability and objectivity of the evaluation, the individual expert ratings for each alternative on every sub-criterion were aggregated by calculating the mean value, which was then used as the input performance score in the ELECTRE III analysis.

4. Case Study

4.1. Case Study Background

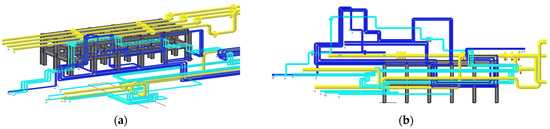

To demonstrate the applicability and feasibility of the proposed fuzzy-integrated MCDM framework, this study applies the method to an industrial piping construction project. The validation process utilizes a detailed 3D BIM model, shown in Figure 5, which accurately reflects the site conditions. The project involves a large-scale piping network with a length of 47.68 m, a width of 35.44 m, and a height of 21.17 m, with pipe diameters varying from 80 mm to 300 mm.

Figure 5.

Three-dimensional piping construction model: (a) 3D view; (b) Front Elevation.

The complexity of the project arises from several key factors. The layout of the pipe network results in a confined working environment, with multiple elevated work zones that increase the risk of falls and other spatial hazards. Additionally, the site faces constraints such as limited workspace and heavy machinery. The conditions increase the probability of accidents, making traditional safety planning methods, which typically depend on isolated risk assessments, insufficient for addressing the risks on site.

In this study, a set of alternative safety control strategies was considered, as summarized in Table 4, addressing key aspects such as personal protective equipment, safety monitoring technologies, safety training programs, and temporary facility arrangements. Each alternative represents a configuration of risk control measures according to site-specific conditions. The five alternative strategies (A1–A5) were formulated based on a combination of industry practices, equipment availability in the market, and typical configurations observed in similar piping projects. Each alternative represents a safety-investment level, ranging from high-investment integrated solutions (e.g., A1 with BIM + VR training and reinforced facilities) to low-cost and basic approaches (e.g., A5 with handbook training and lightweight structures). The integration of PPE, monitoring, training, and facility elements reflects real-world decision scenarios in which project managers typically select coordinated safety packages rather than assembling unrelated individual items.

Table 4.

Detailed configuration of potential alternatives.

Following the methodology described in Section 3.2, to evaluate these alternatives under multiple conflicting criteria, including PPE performance, procedural safety management, temporary facility planning, and cost efficiency, the proposed fuzzy AHP-ELECTRE III framework was applied. This case study allows for systematic ranking of the alternatives, facilitating the identification of the most effective combination of measures for the project. Implementing the optimal alternative can enhance safety protection during piping construction, mitigate potential hazards, and improve overall project performance to safety-related risks.

4.2. Fuzzy AHP Evaluation

During the analysis process in this study, a total of 15 decision makers participated. This sample size was determined with reference to prior methodological literature [52,53], which suggests that a panel of 10 to 20 experts effectively balances the need to capture diverse perspectives with the requirement for reliable group judgment. Furthermore, the appropriateness of utilizing 15 experts has been validated in recent multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) studies within the field of construction safety [5,54].

As described in Section 3.2, expert assessment is the first step in the fuzzy AHP, ensuring that the weight calculation incorporates diverse professional judgments. The composition of the expert panel was designed to encompass the key stakeholders involved in and affected by safety planning decisions on a construction project. Their demographic and professional characteristics are summarized in Table 5. The panel consisted of construction superintendents (33.3%), project managers (13.3%), operation managers (13.3%), OHS and cost managers (each 6.7%), and construction workers (26.7%). All members possessed substantial field experience, with an average professional tenure ranging from 8 to 20 years.

Table 5.

Demographic and professional characteristics of the participating experts.

Participants were distributed across three age groups: 25–34 years (26.7%), 35–44 years (40.0%), and 45–54 years (33.3%). The majority of experts were male (86.7%), and the remaining were female (13.3%). Regarding educational background, 66.7% of participants held a bachelor’s degree, 20.0% held a master’s degree or above, and 13.3% had a high school diploma. This diverse composition ensures that the evaluation incorporates both managerial oversight and practical on-site experience.

The study was conducted in accordance with ethical principles for research involving human participants. Experts provided the judgments only, and no personal or sensitive information was collected. As a non-interventional study using anonymized expert input, formal Institutional Review Board approval was not required. All participants were informed of the study purpose, provided informed consent, and could withdraw at any time.

Based on the expert assessment, the weight values of the main criteria and their corresponding sub-criteria were determined using the fuzzy AHP method. According to Section 3.2, the fuzzy AHP procedure involved synthesizing the judgments from the 15 experts into triangular fuzzy number (TFN) matrices, calculating Coefficient of Variation (CV), and verifying consistency (CR) to ensure reliable weights.

Specifically, to evaluate the judgments from the experts, the geometric mean method was applied to integrate the individual triangular fuzzy number (TFN) matrices into a single group comparison matrix. Based on the results of the expert survey, the coefficient of variation (CV) was calculated for each pairwise comparison across all criteria through Equation (4). All resulting CV values were consistently below 0.25, indicating a high degree of consensus among experts and reinforcing the reliability of the aggregated judgments.

The resultant aggregated TFNs were then mapped to the nearest value on the predefined linguistic scale to maintain consistency and interpretability in the final matrix [55,56]. In addition to consensus assessment, the logical coherence of the group judgments was verified by calculating the consistency ratio (CR) for each fuzzy comparison matrix. All CR values for the main criteria and sub-criteria matrices were below the conventional threshold of 0.10 as shown in Table 6, confirming that the judgments satisfied the required consistency standards.

Table 6.

Fuzzy pairwise comparison matrix towards decision criteria and sub-criteria.

To illustrate the calculation process, the pairwise comparison between C1 and C2 is illustrated below. The 15 experts provide linguistic judgments regarding the relative importance of C1 compared to C2, which were converted to TFNs according to Table 2. For instance, when an expert judged C1 as “moderately less important” than C2, the TFN was taken as (1/4, 1/3, 1/2). Using the geometric mean method, the TFNs provided by all experts were aggregated. Based on the expert judgments, the aggregated TFN was obtained as . This TFN was then mapped to the nearest value on the standard linguistic scale. As a result, the group comparison matrix entry for C1 vs. C2 in Table 6 was (1/3, 1/2, 1). The same procedure was repeated for all pairwise comparisons to establish the final fuzzy comparison matrices.

Table 6 presents the final fuzzy pairwise comparison matrix, where for the main criteria and sub-criteria, along with the associated weight vector. In addition, the normalized weights of all sub-criteria are determined, providing a quantification of the relative importance within each safety criterion. Specifically, the main criteria, including the personal protective equipment (C1), procedural safety management (C2), temporary facility planning (C3), and cost efficiency (C4), achieved weight values of 0.2490, 0.3705, 0.2183, and 0.1622, respectively, highlighting that procedural safety management is regarded as the most critical factor in the overall assessment.

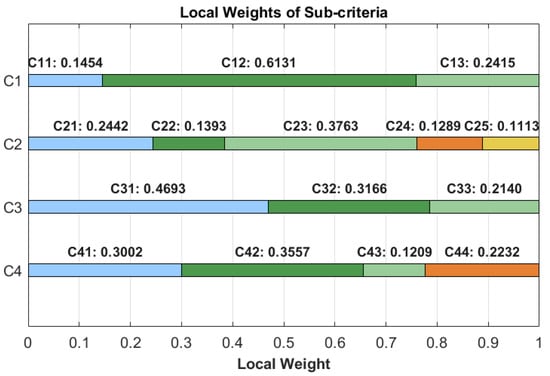

Among the sub-criteria shown in Figure 6, C12 under personal safety equipment, which represents fall prevention performance, has the highest local weight (0.6131), indicating its predominant influence on PPE selection decisions. Similarly, for procedural safety management (C23), representing adequate plan view, achieves the greatest importance (0.3763), while temporary facility planning is most influenced by site layout planning (C31, 0.4693). For cost-related considerations, rental cost saving (C42, 0.3557) has the largest contribution among the sub-criteria. These weight distributions provide a quantitative foundation for the subsequent multi-criteria evaluation of alternative risk control strategies, ensuring that the analysis accurately reflects expert judgments on the relative significance of various safety criteria in construction project management.

Figure 6.

The local weights of sub-criteria among different main criteria.

Then the priority weights of the main criteria and sub-criteria were determined using the fuzzy AHP, as summarized in Table 7. Among the four main criteria, procedure safety management (C2) achieved the highest weight of 0.3705, indicating its dominant role in ensuring overall safety performance. This emphasizes that systematic safety management practices, such as inspection, monitoring, and safety training, play a vital role in effective safety risk control in construction projects. The second most important criterion is personal safety equipment (C1), with a weight of 0.2490, highlighting the critical contribution of reliable protective equipment to overall safety performance. Temporary facility planning (C3) ranked third (0.2183), while cost-related considerations (C4) is comparatively less significant (0.1622), indicating that safety-related factors outweigh economic concerns in safety risk control.

Table 7.

Weight values of main criteria and sub-criteria.

Based on the local weights and the priority weights of the main criteria, the global weights of sub-criteria are generated. Specifically, fall prevention performance (C12) obtained the highest global weight (0.153), ranking first among all sub-criteria, which shows that preventing falls remains the single most important safety factor in piping projects. Adequate plan review (C23) achieved the second-highest global weight (0.139), followed by inspection measures (C21, 0.090), reflecting the importance of both proactive planning and systematic oversight. Meanwhile, site layout planning (C31) ranked third with a global weight of 0.102, indicating its critical role in reducing hazards associated with spatial congestion and material handling. On the other hand, maintenance cost efficiency (C43, 0.020) had the lowest weight among all sub-criteria. This suggests that while cost efficiency is relevant, its influence on safety risk control is limited compared with the technical and procedural safety measures.

To further visualize the weighting results, Figure 7a illustrates a radar chart of the four main criteria. The diagram shows the dominance of procedure safety management (C2), forming the widest radius on the chart, followed by personal safety equipment (C1) and temporary facility planning (C3), while cost (C4) occupies the smallest area. This graphical chart confirms that managerial and procedural factor has a stronger influence on safety control decisions than cost-related ones. Meanwhile, Figure 7b presents the radar chart of all sub-criteria, which shows the relative significance across different safety domains. The figure highlights that fall prevention performance (C12), adequate plan review (C23), and site layout planning (C31) dominate the safety hierarchy, forming the three highest peaks in the chart. In contrast, maintenance cost efficiency (C43) and communication among stakeholders (C25) locate near the center, indicating their comparatively minor significance. The remaining sub-criteria achieved moderate weights, indicating their contributions to the overall model are consistent but relatively limited.

Figure 7.

Radar chart of main criteria and sub-criteria. (a) Radar chart of main criteria weights; (b) Radar chart of sub-criteria weights.

Building on these results, the high weight of procedure safety management (C2) indicates that construction companies should prioritize systematic safety practices, such as inspection, monitoring, training, and plan review, over focusing solely on new PPE or equipment investments. This suggests that some companies may currently over-invest in visible safety measures while under-investing in procedural measures that have greater impact on overall safety performance. Emphasizing these procedural measures can lead to more effective risk reduction and improved on-site safety outcomes.

4.3. ELECTRE III Outranking and Alternative Ranking

The FAHP-derived weights were subsequently integrated into the ELECTRE III model to perform the outranking analysis and determine the final ranking of alternatives. The determined weights from the FAHP analysis play a critical role in guiding the subsequent ELECTRE III ranking. Specifically, the high weight assigned to procedural safety management (C2, 0.3705) means that alternatives emphasizing robust procedures, inspections, and training (such as A1 and A3) are inherently favored in the ELECTRE III evaluation. Similarly, the high local weight of fall prevention performance (C12, 0.6131) ensures that alternatives incorporating advanced fall-protection PPE gain higher rankings. Conversely, criteria with lower weights, such as maintenance cost efficiency (C43, 0.020), exert minimal influence on the final ranking. This integration illustrates that FAHP is not a standalone step; rather, it provides the quantitative foundation for ELECTRE III, ensuring that the final alternative ranking reflects both expert judgment and the relative importance of multiple safety criteria. In practical terms, this shows that managers should prioritize procedural and PPE-related measures when allocating resources, as these factors most strongly affect the effectiveness of safety strategies.

To conduct the performance assessment scores required for the ELECTRE III outranking analysis, the raw evaluations from 15 experts were consolidated by calculating the arithmetic mean for each alternative under every criterion. This step yields an integrated assessment reflecting the collective judgment of the expert panel. The final averaged performance scores are reported in Table 8, which constitutes the basis for the subsequent normalization and outranking computations.

Table 8.

Performance scores of alternatives for ELECTRE III analysis.

Based on the initial performance scores from the experts, the ELECTRE III method was applied to integrate the obtained weights and determine the overall ranking of safety control alternatives. In this study, the indifference, preference, and veto thresholds were set to q = 0.05, p = 0.10, and v = 0.50. These threshold values are consistent with parameter settings adopted in previous studies [57,58]. The chosen values reflect expert consensus that differences below 5% are negligible, differences above 10% indicate a clear preference, and deviations exceeding 50% represent unacceptable performance. These thresholds were validated through expert discussion and ensure a stable and interpretable outranking structure.

Based on the parameters, the fuzzy preference matrix was computed, as presented in Table 9. The matrix presents the pairwise preference degrees S(i,j) among the five alternatives (A1–A5), where higher values indicate stronger preference of alternative i over j. Overall, the high pairwise credibility values (mostly exceeding 0.7) indicate a preference structure among the alternatives.

Table 9.

Preference matrix from the ELECTRE III model.

The aggregated results presented in Table 10 reveal that Alternative A1 achieved the highest net outranking flow (0.6873), followed by A3 (0.5028) and A2 (0.2422), ranking first, second, and third, respectively. A4 and A5 exhibited negative net flows, ranking fourth and fifth. The results indicate that the configuration of A1, characterized by advanced PPE, BIM–VR-based training, and centralized facility layout, offers an effective approach to safety risk control, whereas A4 and A5 demonstrate lower overall performance. These rankings represent Section 3.3 outputs and demonstrate how the proposed MCDM framework can identify the optimal combination of safety measures for complex piping projects.

Table 10.

Concordance results and final ranking of alternatives.

5. Discussions

5.1. Sensitivity Analysis

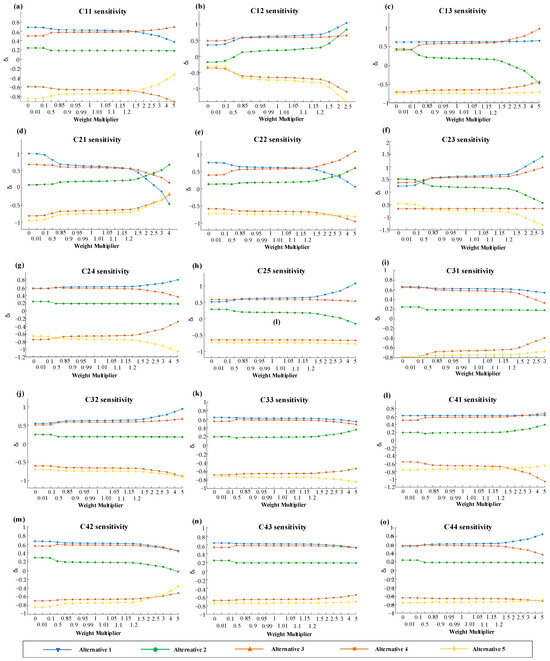

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the stability of the ELECTRE III ranking outcomes under variations in the weighting coefficients of the evaluation criteria. For each criterion, its original weight was adjusted according to the scaling factors shown in Figure 8 (ranging from 1% to 500% times the baseline value), while all other weights were proportionally normalized to maintain consistency in the total weight. After each adjustment, the ELECTRE III procedure was re-executed to obtain a new ranking of the five alternatives (A1–A5). The resulting ranking was then compared with the baseline ranking based on the original weights, and the magnitude of ranking change was recorded.

Figure 8.

Heatmap of ranking changes for criteria under weight perturbations (dark green: minimal change; medium green: moderate change; light green: substantial change).

As shown in Figure 8, the color of each cell represents the number of positions by which the ranking of each criterion changes under the corresponding weight adjustment. Dark green indicates minimal change, medium green indicates moderate change, and light green indicates substantial change in the ranking. Most criteria, including C31, C32, C33, and C43, predominantly display dark green values, indicating very high stability, with their associated ranking outcomes remaining virtually unchanged under all weight variations. Criteria such as C11, C13, C12, C24, C25, C41, and C42 also show mostly dark green values, with occasional light green occurrences at extreme weight adjustments (e.g., weights exceeding 1.5 times the baseline), suggesting high stability with minor sensitivity under substantial weight increases. Conversely, C21, C22, and C44 contain a relatively higher proportion of light green values, reflecting moderate sensitivity, as their ranking positions are more affected when the weights are significantly increased. Overall, the predominance of dark green values across the majority of criteria confirms that the FAHP–ELECTRE III integrated model maintains strong robustness.

To further assess the robustness of the integrated FAHP–ELECTRE III decision-making framework, a sensitivity analysis was conducted by varying individual criterion weights (C11–C44) over a multiplier range of 0–5 times their baseline values. The corresponding δi values for the five alternatives (A1–A5) were plotted in Figure 9. This analysis provides insight into the stability of alternative rankings and identifies criteria exerting significant influence on decision outcomes.

Figure 9.

Sensitivity of the alternatives under varying criterion weights: (a) C11 sensitivity; (b) C12 sensitivity; (c) C13 sensitivity; (d) C21 sensitivity; (e) C22 sensitivity; (f) C23 sensitivity; (g) C24 sensitivity; (h) C25 sensitivity; (i) C31 sensitivity; (j) C32 sensitivity; (k) C33 sensitivity; (l) C41 sensitivity; (m) C42 sensitivity; (n) C43 sensitivity; (o) C44 sensitivity.

Criteria C31, C32, C33, C41, C42, C43, and C44 showed low sensitivity. For these criteria, δi values of all alternatives remained relatively stable across the entire weight multiplier range, with smooth curves and no significant intersections or divergence among top-ranked alternatives. A1 and A3 consistently ranked at the top across the weight range, maintaining a clear performance hierarchy. This indicates that the relative preference ordering is largely insensitive to changes in these criteria, allowing the weights to be assigned with relatively high flexibility without affecting overall decision outcomes.

Criteria C11, C13, C24, and C25 exhibited moderate sensitivity, with δi values of some alternatives showing noticeable changes as weights varied. For example, Figure 9a (C11) shows A1 gradually declining in δi while A3 increases, potentially affecting mid-tier rankings. Similarly, Figure 9c (C13) illustrates divergence among δi trajectories of A1 and A3. Despite occasional intersections in the δi trends of different alternatives, A1 and A3 consistently emerge as the top-performing options, with A1 ranking first in most scenarios and A3 occasionally attaining the highest ranking. These criteria therefore require careful weight assignment to ensure the stability of medium-performing alternatives, while the overall dominance of A1 and A3 remains largely intact.

Criteria C12, C21, C22, and C23 exhibited high sensitivity, with δi trajectories intersecting and potential ranking reversals under substantial weight changes. For example, increasing the C21 weight elevates A2 above both A1 and A3, making it the top-ranked alternative, while for C12, A2 surpasses A3 but remains behind A1, becoming the second. These results indicate that, although A1 and A3 generally remain among the highest-performing alternatives, high-sensitivity criteria can significantly alter the rankings of other alternatives under extreme weight scenarios, highlighting the importance of precise weight assignment.

Overall, the sensitivity analysis indicates that top-performing alternatives, particularly A1 and A3, consistently maintain high rankings across low- and moderately sensitive criteria, demonstrating the overall robustness of the FAHP–ELECTRE III framework. However, alternatives with moderate performance (A2, A4, and A5) exhibit more variable δi responses to moderately- and highly sensitivity criteria, particularly C11, C12, C13, C21, C22, and C23, which can induce shifts in mid- or lower-tier rankings and, in extreme cases, cause temporary reversals of top positions. These findings emphasize that, while A1 generally remains the optimal alternative and A3 occasionally attains the top ranking, careful weight assignment for sensitive criteria is crucial to preserve ranking stability and ensure reliable decision outcomes. Therefore, managers should prioritize these influential criteria during weight elicitation to optimize strategy implementation and resource allocation.

5.2. Comparisons of Different MCDM Methods

In order to evaluate the consistency and validity of the proposed FAHP–ELECTRE III framework, the alternative scores obtained from four MCDM methods, including ELECTRE III, MAVT, TOPSIS, and VIKOR, were compared. As shown in Figure 10, A1 consistently attains the highest score, confirming its dominant performance across the ELECTRE III, MAVT, and VIKOR methods. A3 closely follows, ranking second or third depending on the method, while A4 and A5 remain at the bottom across all approaches. Although the final scores differ due to varying computational processes, the relative distribution of alternative performance remains coherent. Notably, the score profiles obtained from the proposed FAHP–ELECTRE III model closely align with those of MAVT and VIKOR, indicating that the proposed method yields consistent and credible assessment outcomes within a multi-method framework.

Figure 10.

Alternative scores obtained from four multi-criteria decision-making methods: (a) ELECTRE III; (b) MAVT; (c) TOPSIS, and (d) VIKOR.

The ranking consistency among the four methods is further depicted in Figure 11, which visualizes the ranking positions of alternatives. The results reveal a high level of concordance in ranking results, where A1 maintains the top position and A4–A5 consistently occupy the lowest ranks across all methods. The only minor variation appears between A2 and A3, which interchange their rankings (second and third) under TOPSIS and other methods. This ranking difference can be explained by the calculation mechanism of TOPSIS, which evaluates alternatives based on their distances to the ideal and negative-ideal solutions. A2 attains relatively high scores on key criteria such as fall prevention performance (C12) and real-time monitoring (C22), whereas A3 demonstrates more balanced performance across criteria. As a result, the distance-based aggregation slightly favors A2, leading to its higher ranking in TOPSIS. This difference reflects the method’s sensitivity to peak performance on specific criteria rather than a contradiction in overall alternative performance. Therefore, this variation is mainly due to differences in normalization and aggregation across methods, rather than reflecting real conflicts in alternative performance. The generally parallel ranking lines indicate that the overall results are stable and consistent across methods. These findings confirm the framework’s robustness and its practical usefulness for multi-criteria decisions of safety risk control strategies in construction projects.

Figure 11.

Ranking trends of alternatives across four decision-making methods.

5.3. Synergy Analysis of the Optimal Strategy

Beyond identifying A1 as the top-ranked strategy, it is essential to clarify the mechanisms that explain why A1 configuration outperforms the others. The superiority of A1 arises from the synergy among its components rather than the isolated advantage of any single element. First, the use of high-performance fall-protection PPE directly addresses the most influential sub-criterion (C12), leading to a disproportionately large improvement in overall safety performance. Second, BIM-VR training amplifies this effect by enhancing workers’ hazard recognition and procedural compliance, thereby strengthening performance under C21 and C23, two criteria that are both highly weighted and highly sensitive in the model. Moreover, the centralized and reinforced temporary facility layout (C31) reduces spatial congestion and movement uncertainty, creating an environment in which both PPE and procedural controls operate more effectively. Finally, the integration of CCTV and RFID ensures continuous real-time monitoring, which interacts positively with the above measures by reducing response time and closing feedback loops between detection, training, and safe behavior. These interacting mechanisms create a compounded effect: each measure in A1 reinforces the effectiveness of the others, resulting in a level of performance that is not attainable when such elements are implemented individually or in weaker combinations (as in A2–A5). This explains why A1 consistently achieves the highest outranking flows across multiple MCDM methods and remains robust across sensitivity tests.

The findings of this study demonstrate that the integrated safety strategy A1, which combines advanced PPE, BIM–VR training, and centralized temporary facilities, consistently outperforms other alternatives. This result aligns with prior research emphasizing the importance of comprehensive safety management rather than isolated interventions [59,60]. These studies support our observation that organizational and managerial safety controls (such as inspection, training, plan review, oversight) may exert a stronger influence on on-site safety outcomes than mere provision of protective equipment [61,62].

Moreover, consistent with the growing body of literature that applies fuzzy-MCDM to construction management and safety evaluation [33,63], the proposed fuzzy AHP–ELECTRE III framework offers a structured and robust decision-making approach capable of handling multiple conflicting criteria and uncertainty in expert judgment. While previous applications often used fuzzy AHP in combination with distance-based methods (e.g., fuzzy TOPSIS) or single-phase evaluations [33,63], our study extends these by combining fuzzy weighting, outranking, sensitivity analysis and cross-method validation (ELECTRE III, MAVT, TOPSIS, VIKOR) to deliver a more comprehensive and reliable safety strategy evaluation. This methodological advancement demonstrates a clear contribution to the field by offering a more comprehensive and practically applicable framework for construction safety risk control under uncertainty.

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Conclusions

This study proposed a fuzzy-integrated MCDM framework for the evaluation of safety risk control strategies in construction projects. The primary contribution of this research lies in developing a systematic model that combines fuzzy AHP and ELECTRE III to support decision-making in complex construction safety management. Specifically, the framework establishes a novel criteria hierarchy which incorporates multiple safety and productivity-related criteria and sub-criteria, which are evaluated to generate a final ranking of alternative safety strategies. The relative importance of criteria was assessed by experienced experts, and human judgment uncertainty was explicitly addressed using fuzzy theory. Specifically, fuzzy AHP was employed to determine criteria weights, and ELECTRE III was applied to rank alternatives based on these weights. A two-phase sensitivity analysis demonstrated that the ranking results remained relatively stable under variations in criteria weights, confirming the robustness and reliability of the proposed framework. Additionally, the results were further validated by comparing the rankings with other methods, showing high consistency across methods.

The findings suggest that the proposed fuzzy-integrated MCDM approach is an effective tool for decision-making in construction safety management, particularly when expert judgment and subjective knowledge play a key role. Based on the evaluation results, Alternative A1 was identified as the optimal strategy, providing actionable guidance for project managers. Specifically, managers should: (1) equip workers with advanced personal fall protection; (2) deploy dual-technology monitoring systems, such as high-resolution CCTV and RFID tracking methods, to ensure real-time oversight; (3) implement immersive digital training programs using techniques, such as BIM and VR, to enhance safety awareness and operational skills; and (4) adopt a centralized and structurally reinforced layout for temporary facilities to reduce site hazards. Prioritizing these integrated, technology-enhanced, and systematically coordinated safety measures ensures more effective risk control than fragmented or purely cost-driven interventions.

In addition, the sensitivity analysis identified C12 (fall prevention performance), C21 (inspection measures), and C23 (adequate plan review) as highly sensitive criteria that significantly affect alternative rankings. Therefore, the most critical managerial task is to accurately elicit the initial weights for these criteria during planning and decision-making, ensuring that the prioritization of safety measures reflects both expert judgment and the relative importance of these influential factors. This combined guidance facilitates a systematic evaluation of alternative safety strategies while providing a practical basis for resource allocation and risk mitigation during project planning and pre-construction stages.

6.2. Implications

Conceptually, this study advances construction safety decision-making theory by integrating fuzzy AHP and ELECTRE III to handle expert uncertainty, providing a structured multi-criteria evaluation framework, and highlighting the critical sensitivity of key criteria, such as C12, C21, C23 criteria, in strategy selection.

Practically, the results offer clear guidance: adopt integrated safety packages (advanced PPE, dual-tech monitoring, immersive training, robust facilities), focus weight elicitation on sensitive criteria, and use the framework for objective alternative comparison during planning to improve resource allocation and risk control.

This study still has several limitations. First, the number and selection of experts may influence the evaluation outcomes; although the panel of 15 experts was diverse, it may not capture all perspectives. Second, the framework was applied to a piping construction project, and its generalizability to other project types or industries requires further testing. Third, while fuzzy AHP addresses uncertainty in expert judgments, evaluations remain subjective, and potential biases may influence results. In addition, the sensitivity analysis in this study focuses on variations in criterion weights, and the effects of changes in ELECTRE III threshold values (indifference q, preference p, and veto v) on ranking stability were not explored. Future research could examine how threshold perturbations affect robustness and rank reversals, providing a more comprehensive assessment of framework reliability. Recognizing these limitations provides context for interpreting the findings and guides future research. Subsequent work should explore the impact of expert selection and number on outcomes and develop automated decision-support tools to integrate multiple expert assessments, enhancing the efficiency and reliability of safety planning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.J.; methodology, Z.X. (Ziheng Xu) and H.J.; validation, W.Z., H.J. and Z.X. (Zhen Xu); writing—original draft preparation, H.J. and Z.X. (Ziheng Xu); writing—review and editing, Z.X. (Zhen Xu) and H.J.; visualization, Z.X. (Ziheng Xu) and H.J.; supervision, Z.X. (Zhen Xu) and W.Z.; project administration, Z.X. (Zhen Xu); funding acquisition, H.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52508329).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the finds of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sanni-Anibire, M.O.; Mahmoud, A.S.; Hassanain, M.A.; Salami, B.A. A risk assessment approach for enhancing construction safety performance. Saf. Sci. 2020, 121, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, A.; Jha, K.N. Integrating quality and safety in construction scheduling time-cost trade-off model. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 147, 04020160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, N.D.; Behzadan, A.H.; Paal, S.G. Deep learning for site safety: Real-time detection of personal protective equipment. Autom. Constr. 2020, 112, 103085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Kim, T.; Park, Y.-J.; Kim, J.-M. Improving effectiveness of safety training at construction worksite using 3D BIM simulation. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 2473138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohandes, S.R.; Durdyev, S.; Sadeghi, H.; Mahdiyar, A.; Hosseini, M.R.; Banihashemi, S.; Martek, I. Towards enhancement in reliability and safety of construction projects: Developing a hybrid multi-dimensional fuzzy-based approach. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2023, 30, 2255–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Roberts, D.; Golparvar-Fard, M. Human-object interaction recognition for automatic construction site safety inspection. Autom. Constr. 2020, 120, 103356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newaz, M.T.; Ershadi, M.; Carothers, L.; Jefferies, M.; Davis, P. A review and assessment of technologies for addressing the risk of falling from height on construction sites. Saf. Sci. 2022, 147, 105618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Goodrum, P.M. Integrated decision support framework of optimal scaffolding system for construction projects. Algorithms 2023, 16, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Nahangi, M.; Goodrum, P.M.; Yuan, Y. Multiobjective optimization for scaffolding space planning in industrial piping construction using model-based simulation programming. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2020, 34, 06019001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Guo, Y.; Ge, F.-L.; Yang, F.-Q. Human reliability assessment on building construction work at height: The case of scaffolding work. Saf. Sci. 2023, 159, 106021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, A.; Seagers, J.; Shayesteh, S.; Habibnezhad, M.; Jebelli, H. Construction safety training methods and their evaluation approaches: A systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Construction Engineering and Project Management, Hong Kong, China, 7–8 December 2020; Korea Institute of Construction Engineering and Management: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2020; pp. 188–197. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.; Khalid, R.; Anjum, S.; Tran, S.V.-T.; Park, C. Fall prevention from scaffolding using computer vision and IoT-based monitoring. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 148, 04022051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Yoon, J.; Ham, Y.; Lee, B.; Kim, H. Monitoring safety behaviors of scaffolding workers using Gramian angular field convolution neural network based on IMU sensing data. Autom. Constr. 2023, 148, 104748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Saleem, M.R.; Lee, D.; Park, M.-W.; Park, C. Utilizing safety rule correlation for mobile scaffolds monitoring leveraging deep convolution neural networks. Comput. Ind. 2021, 129, 103448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monghasemi, S.; Nikoo, M.R.; Fasaee, M.A.K.; Adamowski, J. A novel multi criteria decision making model for optimizing time–cost–quality trade-off problems in construction projects. Expert Syst. Appl. 2015, 42, 3089–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedir, N.S.; Raoufi, M.; Fayek, A.R. Fuzzy Agent-Based Multicriteria Decision-Making Model for Analyzing Construction Crew Performance. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 04020053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grierson, D.E. Pareto multi-criteria decision making. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2008, 22, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Ding, L.; Luo, H.; Qi, S. A multi-attribute model for construction site layout using intuitionistic fuzzy logic. Autom. Constr. 2016, 72, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawan, P.; Lorterapong, P. A fuzzy-based integrated framework for assessing time contingency in construction projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2016, 142, 04015083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.; Jha, K. Evaluation of construction projects based on the safe work behavior of co-employees through a neural network model. Saf. Sci. 2016, 89, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Zhong, L.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, J.; Shen, C.; Pena-Mora, F. Multistakeholder conflict minimization–based layout planning of construction temporary facilities. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2018, 32, 04017080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plebankiewicz, E.; Kubek, D. Multicriteria selection of the building material supplier using AHP and fuzzy AHP. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2016, 142, 04015057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.-Q.; Zhang, N. Risk assessment of water inrush accident during tunnel construction based on FAHP-I-TOPSIS. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 449, 141744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, T.; Liu, J.-W.; Li, Q.-F. Safety Risk Evaluation of Large and Complex Bridges during Construction Based on the Delphi-Improved FAHP-Factor Analysis Method. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 2022, 5397032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Qiu, R.; Chen, M.; Xiao, S. Research on operational safety risk assessment method for long and large highway tunnels based on FAHP and SPA. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Song, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, D.; Sun, Y.; Zeng, T.; Xie, J. Risk assessment of deep excavation construction based on combined weighting and nonlinear FAHP. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1204721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, M.M. ELECTRE III model for value engineering applications. Autom. Constr. 2011, 20, 596–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M.; Bruen, M. Choosing realistic values of indifference, preference and veto thresholds for use with environmental criteria within ELECTRE. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1998, 107, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepple, M.-K.T.; Ikeremo, E.S. Multicriteria Decision Analysis for Stock Selection: A Comparative Study of ELECTRE III with Veto, TOPSIS, and PROMETHEE Methods. Int. J. Eng. Mod. Technol. 2025, 11, 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Ghimire, P.; Barutha, P.; Jeong, H.D. Risk-Based Decision-Making Framework for Implementation of Collaboration and Integration Strategies. J. Manag. Eng. 2024, 40, 04024041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worku, T.T. Formwork material selection and optimization by a comprehensive integrated subjective–objective criteria weighting MCDM model. Discov. Mater. 2025, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H.; Madanchian, M. A comprehensive survey and literature review on TOPSIS. Int. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. Eng. Technol. 2024, 15, 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Meng, X.; Zhang, M. Application of multiple criteria decision making methods in construction: A systematic literature review. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2021, 27, 372–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Na, S.; Dang, X.; Zhang, Y. Study of the Competitiveness of Quanzhou Port on the Belt and Road in China Based on a Fuzzy-AHP and ELECTRE III Model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, S.; Alipouri, Y.; Chamanzad, S. Smart Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for construction safety: A literature review. Saf. Sci. 2024, 170, 106368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, M.; Shakeri, E.; Ardeshir, A.; Malekitabar, H. Optimizing travel distance of construction workers considering their behavioral uncertainty using fuzzy graph theory. Autom. Constr. 2021, 124, 103574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Gambatese, J. Exploring the potential of technological innovations for temporary structures: A survey study. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, K.-T.; Vu, D.-N.; Hong, P.L.H.; Park, C. 4D-BIM-based workspace planning for temporary safety facilities in construction SMEs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borell, J.; Osvalder, A.-l.; Aryana, B. Evaluating the Correct Usage, Comfort and Fit of Personal Protective Equipment in Construction Work. Ergon. Des. 2024, 129, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar-Khanzadeh, F.; Bisesi, M.S.; Rivas, R.D. Comfort of personal protective equipment. Appl. Ergon. 1995, 26, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evanoff, B.; Dale, A.M.; Zeringue, A.; Fuchs, M.; Gaal, J.; Lipscomb, H.J.; Kaskutas, V. Results of a fall prevention educational intervention for residential construction. Saf. Sci. 2016, 89, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robson, L.S.; Lee, H.; Amick, B.C., III; Landsman, V.; Smith, P.M.; Mustard, C.A. Preventing fall-from-height injuries in construction: Effectiveness of a regulatory training standard. J. Saf. Res. 2020, 74, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuluaga, C.M.; Albert, A.; Winkel, M.A. Improving safety, efficiency, and productivity: Evaluation of fall protection systems for bridge work using wearable technology and utility analysis. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04019107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, S.; Gambatese, J. Risk and financial impacts of prevention through design solutions. Pract. Period. Struct. Des. Constr. 2013, 18, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Goodrum, P.M. Optimal fall protection system selection using a fuzzy multi-criteria decision-making approach for construction sites. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, Y.M.; Goh, W.M. Investigating the effectiveness of fall prevention plan and success factors for program-based safety interventions. Saf. Sci. 2016, 87, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. A scaling method for priorities in hierarchical structures. J. Math. Psychol. 1977, 15, 234–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Information and control. Fuzzy Sets 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy logic. Computer 1988, 21, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Tan, J.; Dong, G.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Che, C.; Yuan, S.; Teng, X.; Sun, X.; Wang, C. Formulating Assessment Criteria for Filiform Needle Manipulation Techniques: An e-Delphi Study. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2025. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Sun, S.; Deng, J.; Liu, S.; Yin, T.; Peng, Q.; Gong, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Zhou, B. Establishment and application of an index system for the risk of drug shortages in China: Based on Delphi method and analytic hierarchy process. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2022, 11, 2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saaty, T.L. The analytic hierarchy process mcgraw hill, New York. Agric. Econ. Rev. 1980, 70, 10–21236. [Google Scholar]

- Okoli, C.; Pawlowski, S.D. The Delphi method as a research tool: An example, design considerations and applications. Inf. Manag. 2004, 42, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayebi, A.; Abbasianjahromi, H.; Aghakarimi, M. Using a hybrid method to assess the consequence of hazards on the project success factors. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2025, 32, 8273–8303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data, P. Fuzzy analytical hierarchy process (FAHP) using geometric mean method to select best processing framework adequate to big data. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2021, 99, 207–226. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, J.J. Fuzzy hierarchical analysis. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1985, 17, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Huang, X. An extension of ELECTRE to multi-criteria decision making problems with extended hesitant fuzzy sets. Sci. Technol. 2018, 21, 328–343. [Google Scholar]

- Giannoulis, C.; Ishizaka, A. A Web-based decision support system with ELECTRE III for a personalised ranking of British universities. Decis. Support Syst. 2010, 48, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asah-Kissiedu, M.; Manu, P.; Booth, C.A.; Mahamadu, A.-M.; Agyekum, K. An integrated safety, health and environmental management capability maturity model for construction organisations: A case study in Ghana. Buildings 2021, 11, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Cheung, C.M.; Li, H.; Hsu, S.-C. Understanding the relationship between safety investment and safety performance of construction projects through agent-based modeling. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2016, 94, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Chan, A.H. Improving the safety performance of construction workers through individual perception and organizational collectivity: A contrastive research between Mainland China and Hong Kong. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Luo, X.; Feng, J.; Li, H.; Liu, B.; Jian, Y. Research on the impact of managers’ safety perception on construction workers’ safety behaviors. Buildings 2024, 14, 3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Pan, W. Review fuzzy multi-criteria decision-making in construction management using a network approach. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 102, 107103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.