Abstract

Earthquake effects were investigated in single-story masonry buildings with walls of different heights and thicknesses. Five different masonry building models were created, with wall thicknesses ranging from 16 cm to 32 cm and wall heights ranging from 260 cm to 340 cm. In total, 25 different masonry building models were analysed using the STA4 CAD programme in accordance with the 2018 Turkish Earthquake Code. C-30 concrete and S-420 steel were used in the designed building models. A 12 cm thick reinforced concrete slab was designed. A live load of 0.2 t/m2 was designed on the slab. The mortar strength of the brick wall was taken as 30 MPa. A comparison of a reference building model with a height of 260 cm and a wall spacing of 16 cm with a building model with a floor spacing of 340 and a wall spacing of 32 cm shows that earthquake resistance can be increased by approximately 72%, and this increase in shear strength reaches approximately 89% and 95% in the “x” and “y” direction, respectively. When the wall thickness was doubled from 16 cm to 32 cm, the highest strength increases of approximately 94% was observed in the model with a wall height of 300 cm.

1. Introduction

While the use of classical masonry structures in Türkiye is decreasing in urban centres, it is still widely preferred in rural areas. According to 2023 data from the Turkish Statistical Institute (TÜİK), approximately 15–20% of Türkiye total housing stock consists of masonry structures. This percentage can exceed 30% in rural areas. Masonry structures are constructed from natural materials such as stone, brick, adobe, briquette, and wood, and assembled using their own weight or mortar [1]. A large portion of Türkiye lies within the Alpine-Himalayan Earthquake Zone, one of the world’s high-risk earthquake zones. Numerous devastating earthquakes have occurred in Türkiye and many countries within this earthquake zone over the past century. Therefore, buildings constructed in Turkey must be earthquake-resistant to protect them from the devastating effects of earthquakes [2]. The world is the best laboratory for studying the behaviour of buildings after earthquakes. Therefore, researchers have conducted numerous detailed studies after earthquakes, observing damage to structures and gaining valuable insights into the causes of damage. Ingham and Griffith conducted a study on the structural response of unreinforced masonry structures after the 2010 Darfield earthquake in Christchurch, New Zealand [3]. Augenti and Parisi investigated the structural damage in various buildings after the 2009 L’Aquila earthquake in Italy [4]. Evaluated the structural response of masonry structures and churches after the 22 February 2011 Christchurch earthquake [5]. The evaluated the damage of various structures such as reinforced concrete, masonry and adobe buildings in the 2010 Elazığ-Kovancılar earthquake [6]. The seismic response of engineered masonry structures after the 2010 Maule, Chile earthquake [7]. The conducted a field observation on the damage of unreinforced masonry structures during the 2011 Elazığ-Maden moderate earthquake in Türkiye [8]. The damage to different buildings in the 2011 Kütahya-Simav earthquake in Türkiye [9]. One of the most important factors affecting mortar joint thickness is the workmanship during the installation phase [10]. The high seismic vulnerability of masonry buildings is primarily related to the specific building configuration (the number of thin walls, open layout, improper connections between structural components). Also, to the inherent mechanical properties of the masonry material, which is characterised by a high degree of inelastic response and very low tensile strength [11]. These masonry structures were constructed by skilled architects and builders who attempted structural systems that, while generally adequate to carry gravity loads, were not always adequate to carry lateral loads resulting from earthquake shaking [12]. The presence of openings can result in a decrease in seismic performance indicators such as the shear bearing capacity and ductility of the walls and a change in the damage pattern of the walls, making walls with windows more susceptible to damage during earthquakes [13]. Masonry structures do not exhibit high dispersion in material properties and highly nonlinear responses and Tassios [14].

The adverse effects of earthquakes on historic masonry structures are a significant issue among architects, engineers, and preservationists regarding cultural heritage and life safety in earthquake-prone areas. Historically, seismic events have had devastating consequences, leaving indelible marks on the structural integrity and cultural significance of masonry structures. Seismic forces induced by earthquakes have impacted these structures, often resulting in serious damage or destruction [15,16,17,18,19]. The ability of CM structures to resist structural loading is achieved through the combined effects of masonry walls. Adjacent reinforced concrete restraining elements such as tie columns and tie beams, as well as plinth bands, sill bands, lintel bands, and roof slabs [20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. In CM, damage due to vertical loading alone is not considered a critical issue because walls are always designed to undergo relatively low axial compressive stress. Although designed to resist vertical loads, masonry structures may still experience critical damage modes when subjected to gravity and lateral seismic loading, as the low tensile strength of the wall may become a limiting factor. As reported in past literature, CM buildings have shown excellent performance during earthquakes [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. Aspect ratio has a significant effect on the behaviour of CM walls. Existing experimental studies are limited and do not provide a sufficient understanding of the effect of AR on CM behaviour. Especially considering the significant differences in materials and construction methodologies around the world [42]. To ensure the health of masonry structures throughout their service life, a damage assessment programme must be followed. With their complex structures, fragility assessment of these structures is mandatory to determine damage locations as well as their structural integrity [43,44,45,46]. Structures are expected to provide safety to the occupants [47]. It is known that seismic hazards can occur anywhere in the world and cause major losses [48,49]. Walls that do not meet these requirements will not be considered as load-bearing elements [50]. According to 2018 TEC section 11.5, walls to be considered as load-bearing elements must meet the requirements given in Table 1. Walls that do not meet these conditions will not be considered as load-bearing elements.

Table 1.

Geometric conditions acting on walls under shear force.

In this study, 25 different wall thickness/wall height ratios were created for 5 different wall heights and 5 different wall thicknesses, depending on the variables of wall thickness and wall height. The weights of the masonry building models designed with these wall models were calculated by analysing the base shear forces and seismic loads acting on these models in the “x” and “y” directions. The correlation coefficients between wall thickness and wall height and these parameters were determined, and intergroup comparisons were made for the 25 different models using statistical methods. Thus, it was determined through comparison tests which wall models were the same and which were different for the examined parameters, and the results were compared. Prediction models were created to estimate the weights of the building models created depending on the wall thickness and wall height ratios. The building base shear forces and seismic loads acting on these building models in the “x” and “y” directions, and it was observed that the prediction results can be represented the actual results with approximately. The analysis results are presented in tables and graphs.

The 2018 TEC stipulates a minimum brick wall thickness of 24 cm and a wall height-to-wall thickness ratio of 12. However, because masonry buildings are constructed in rural areas and without proper supervision, these requirements are not met. This situation can lead to masonry buildings being considered risky in terms of earthquakes. To determine the earthquake risk levels of masonry buildings, particularly those constructed in rural and economically disadvantaged areas, this study used wall thicknesses ranging from 16 cm to 32 cm (as observed in field applications). Story heights ranging from 260 cm to 340 cm2 to assess earthquake resistance for the worst-case scenario building models. To illustrate the situation in rural areas and highlight potential risks, 25 building models were created. Considering the minimum wall thickness of 24 cm and the wall height/wall thickness ratio of 12 cm specified in the earthquake regulations, the wall height (hef) is calculated as 12 × 24 = 288 cm. While this study could only be conducted for a single building model with a floor height of 288 cm and a wall thickness of 24 cm, in order to minimise costs in economically disadvantaged rural areas, the study examined how the seismic resistance of the building changes depending on whether the walls are thicker than the reference wall thickness of 24 cm, or whether the building has floor heights less or more than 288 cm. Therefore, wall thicknesses of 16, 20, 24, 28, and 32 cm were selected, and the seismic resistance of the building models was comprehensively investigated for these possible thicknesses. However, to observe how the seismic resistance of the structure changes when the reference floor height of 288 cm (hef = 24 × 12 = 288 cm) is not adhered to, and when floor heights are lower or higher than this, structural models were created using floor heights of 260, 280, 300, 320, and 340 cm to encompass possible scenarios. For statistical comparison tests, at least two dependent or independent groups are required. In this study, a comprehensive analysis was conducted using 25 different models. Five different wall thickness models for wall thicknesses and five different wall height models for wall heights used to examine the possibilities of non-compliance with regulations. Therefore, the creation of 25 statistically significant groups constituted a very large sample size encompassing all possibilities for the analysis. According to the 2018 TEC earthquake regulations, walls to be considered as load-bearing elements must meet the conditions given in Table 1. Walls that do not meet these conditions will not be considered as load-bearing element.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

In this study, the highest and lowest ratios between story height and wall thickness were compared. The ideal modelling of the structure emerged as a result of these comparisons. The strength of the mortar bonding the load-bearing wall materials used in the walls is of paramount importance. For this purpose, high-strength cement mortar was used. The 25 models used in this study were analysed according to the nonlinear behaviour of the material. According to the 2018 TEC earthquake code, unreinforced masonry buildings, load-bearing walls without reinforcement, and only masonry units were used for masonry structures. The single-story masonry structure was designed with five different story heights and five different wall thicknesses. The structure was modelled in accordance with the 2018 TEC [51]. Structural Analysis for Computer Aided Design (STA4CAD) is a programme used safely in public institutions and private sector building system designs in Türkiye. In StA4-CAD V.14.1 software, masonry brick walls are defined as panel structural elements. Brick wall properties are introduced to the panel element, enabling modelling as a masonry wall. In FEA3D analysis, panel elements are meshed and directly incorporated into the structural matrix, but in frame 3D analysis, they are reduced to constraint points and incorporated into the structural matrix. Panel elements are subdivided into finite elements, taking into account window and door openings. Each panel element is obtained through microanalysis as a finite element with brick wall properties. A general set of equations for each panel element is obtained through microanalysis, and a six-point finite element matrix is obtained using the sub-reduction method. This six-point finite element matrix is incorporated into the global matrix of the structure in the macroanalysis. In the microanalysis, the points to be reduced (N) are assigned as final points. By assigning the initial points (I) to the other points to be reduced, the stiffness matrix for the entire wall for N points is obtained using the Gaussian reduction method. After solving the structure matrix, the displacements can be substituted into the sub-reduction equation set for the panel, and the internal stresses can be obtained. The programme obtains the bar effects in the pier axis set for design purposes. The shell mesh matrix in the panel elements is prepared according to the wall shear and tensile properties, and the bending stiffness of the walls in the weak direction is not considered [52].

Concrete class C30 (compressive strength 30 MPa) and steel class S-420C (tensile strength of steel 420 MPa), which are widely used in our country and whose analysis results are accepted as accurate by official institutions, were used in all structural modelling. A masonry structure model with different story heights and wall thicknesses was created. Fully mixed bricks with load-bearing properties were used in the structure walls. The unit volume weight of the brick is 1.8 t/m3, Module of Elasticity, E = 2100 MPa, design strength fd = 1.4 MPa, and the cement mortar’s characteristics strength used in the brick courses is fuko = 0.35 MPa. The axis spacing of the structures in the plan was selected as 4.5 m for the largest span and 1 m for the smallest span. The number of axes in the “x” and “y” directions is equal, and there are 4 axes. The slab thickness in the building models is 12 cm. The story heights of the buildings were designed as 260 cm, 280 cm, 300 cm, 320 cm and 340 cm. These models were analysed according to the 2018 TEC and possible wall damage was examined. Stress values were calculated for “Collapse Prevention in Building”, “Controlled Damage” and “Limited Damage” performance levels. The behaviour of the building models under earthquake effects was analysed using Sta4cad. In the analysis, Earthquake Level 1 was selected as the reference value for the earthquake ground motion level (probability of exceedance in 50 years is 2%). The soil class is ZC, the structural behaviour coefficient is R = 2.5 and the resistance coefficient is D = 1.5. The spectrum characteristic period is Ta = 0.069 and Tb = 0.347, respectively, and the live load coefficient is 0.3. The bearing capacity and design stress of the soil are taken as 20 t/m2, and the bearing coefficient is 3000 t/m3.

Reinforced concrete calculations were made according to the bearing capacity method according to TS-500-2000, and the section reinforcement was calculated according to the gross section. The earthquake calculations were made using Mode Superposition and Dynamic Analysis methods. Foundations were taken into consideration in the earthquake calculations. The soil stress live load reduction coefficient was taken as 1.00. The differences between the earthquake-induced floor drifts and seismic moments in masonry building models with different story heights were analysed and compared using multiple comparison tests at a 95% confidence interval. Similar and different wall structures are shown in the tables.

In this study, the highest and lowest ratios between story height and wall thickness were compared. The ideal modelling of the structure emerged as a result of these comparisons. The strength of the mortar bonding the load-bearing wall materials used in the walls is of paramount importance. For this purpose, high-strength cement mortar was used.

The 25 models used in this study were analysed according to the nonlinear behaviour of the material. According to the 2018 TEC earthquake code, unreinforced masonry buildings, load-bearing walls without reinforcement, and only masonry units were used for masonry structures.

The 2018 TEC stipulates a minimum brick wall thickness of 24 cm and a wall height-to-wall thickness ratio of 12. However, because masonry buildings are constructed in rural areas and without proper supervision, these requirements are not met. This situation can lead to masonry buildings being considered risky in terms of earthquakes. To determine the earthquake risk levels of masonry buildings, particularly those constructed in rural and economically disadvantaged areas, this study used wall thicknesses ranging from 16 cm to 32 cm (as observed in field applications). Story heights used to range from 260 cm to 340 cm2 to assess earthquake resistance for the worst-case scenario building models. To illustrate the situation in rural areas and highlight potential risks, 25 building models were created. Considering the minimum wall thickness of 24 cm and the wall height/wall thickness ratio of 12 cm specified in the earthquake regulations, the wall height (hef) is calculated as 12 × 24 = 288 cm. While this study could only be conducted for a single building model with a floor height of 288 cm and a wall thickness of 24 cm, in order to minimise costs in economically disadvantaged rural areas, the study examined how the seismic resistance of the building changes depending on whether the walls are thinner or thicker than the reference wall thickness of 24 cm, or whether the building has floor heights less or more than 288 cm. Therefore, wall thicknesses of 16, 20, 24, 28, and 32 cm were selected, and the seismic resistance of the building models was comprehensively investigated for these possible thicknesses. However, to observe how the seismic resistance of the structure changes when the reference floor height of 288 cm (hef = 24 × 12 = 288 cm) is not adhered to, and when floor heights are lower or higher than this, structural models were created using floor heights of 260, 280, 300, 320, and 340 cm to encompass possible scenarios. For statistical comparison tests, at least two dependent or independent groups are required. In this study, a comprehensive analysis was conducted using 25 different models—five different wall thickness models for wall thicknesses and five different wall height models for wall heights—to examine the possibilities of non-compliance with regulations. Therefore, the creation of 25 statistically significant groups constituted a very large sample size encompassing all possibilities for the analysis.

2.2. Numerical Modelling Processes

The compression stresses in the walls will be compared to the allowable stresses based on the type of masonry wall. Loads from the walls and slabs will be taken into account in this calculation. The stress calculated by dividing the wall cross-section area by the reduced wall cross-section area of door and window openings will not exceed the allowable compression stress based on the wall type. The compression safety stress of the wall is 0.25 times the wall strength calculated from the compression strength tests of masonry units and mortar used in wall construction. Depending on the mortar class used in the wall and the average unconfined compression strength of the wall material given in TS-2510, the wall safety stress can be obtained from Table. Walls defined with panel elements can later be corrected collectively in terms of material classes here. After this definition, starting from beam information, walls should be converted to panel elements, and the material and voids in the wall should be defined. For solid walls, after finding the shear centres primarily by finding the shear rigidity of the walls, it is envisaged to distribute the equivalent earthquake loads to the solid walls with this shear spring rigidity. STA4CAD prepares stiffness matrices according to the shear rigidity for brick walls as panel elements. Designing masonry structures with finite elements is the method closest to real behaviour and is used in the design of new masonry structures and in linear/bilinear analyses. The finite element matrix used can be arranged according to the analysis method. By performing bilinear analyses, the gradual behaviours of the wall can be determined. Wall shearing rigidity is taken as K = A/h, bending rigidity is not taken into account. In the mechanical control between the void spaces, vertical stresses due to shear can be greater than the strength stress. if the compressive stresses due to shear can exceed the compressive strength stresses, in case of shear failure, mechanical sway occurs and the wall cannot bear the shear force. The shear force here is distributed to other wall elements.

2.3. Method

The effect of using solid-mix bricks of varying wall thicknesses in the construction of masonry walls on the load-bearing system was investigated. In load-bearing masonry walls, all horizontal and vertical joints were filled with bonding mortar. Door and window openings of the same size were provided at five different story heights and five different wall thicknesses. The 2018 TEC stipulates a minimum brick wall thickness of 24 cm and a wall height-to-wall thickness ratio of 12. However, because masonry buildings are constructed in rural areas and without proper supervision, these requirements are not met. This situation can lead to masonry buildings being considered risky in terms of earthquakes. To determine the earthquake risk levels of masonry buildings, particularly those constructed in rural and economically disadvantaged areas, this study used wall thicknesses ranging from 16 cm to 32 cm (as observed in field applications) and story heights ranging from 260 cm to 340 cm to assess earthquake resistance for the worst-case scenario building models. To illustrate the situation in rural areas and highlight potential risks, 25 building models were created. Considering the minimum wall thickness of 24 cm and the wall height/wall thickness ratio of 12 cm specified in the earthquake regulations, the wall height (hef) is calculated as 12 × 24 = 288 cm. While this study could only be conducted for a single building model with a floor height of 288 cm and a wall thickness of 24 cm, in order to minimise costs in economically disadvantaged rural areas, the study examined how the seismic resistance of the building changes depending on whether the walls are thinner or thicker than the reference wall thickness of 24 cm, or whether the building has floor heights less or more than 288 cm. Therefore, wall thicknesses of 16, 20, 24, 28, and 32 cm were selected, and the seismic resistance of the building models was comprehensively investigated for these possible thicknesses. However, to observe how the seismic resistance of the structure changes when the reference floor height of 288 cm (hef = 24 × 12 = 288 cm) is not adhered to, and when floor heights are lower or higher than this, structural models were created using floor heights of 260, 280, 300, 320, and 340 cm to encompass possible scenarios. For statistical comparison tests, at least two dependent or independent groups are required. In this study, a comprehensive analysis was conducted using 25 different models—five different wall thickness models for wall thicknesses and five different wall height models for wall heights—to examine the possibilities of non-compliance with regulations. Therefore, the creation of 25 statistically significant groups constituted a very large sample size encompassing all possibilities for the analysis. In all designed building models, the plan geometry, opening configuration, material properties, and all calculation parameters were kept constant. In wall models, only wall thicknesses and heights are variable.

In load-bearing masonry walls, all joints, both horizontal and vertical, are filled with binding mortar. The standardised minimum compressive strengths of the masonry units, as determined according to TS EN 772-1, shall not be less than fbmin = 5.0 MPa in the direction perpendicular to the horizontal joints and fbh min = 2.0 MPa in the direction parallel to the horizontal joints [53]. The minimum cube compressive strength values of the mortar to be used, as determined according to TS EN 1015-11, shall not be less than fm min = 5.0 MPa. The characteristic shear strength of the wall was obtained with the following expression. The expression fvk is calculated as follows, where “fvk” represents the characteristic shear strength of the wall obtained using the average vertical stresses on the wall, “fvko” represents the characteristic shear strength in the absence of axial stress, “σd” represents the vertical compressive stress calculated under the combined effect of vertical loads multiplied by load coefficients and seismic loads, and “fb” represents the standardised average compressive strength of the masonry unit (equivalent to a 100 mm × 100 mm specimen free from dimensional effects):

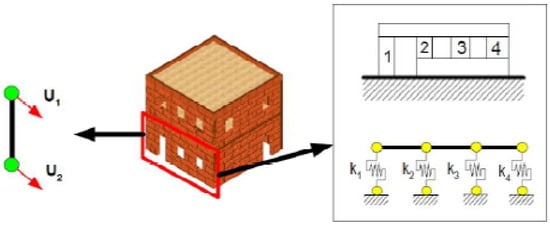

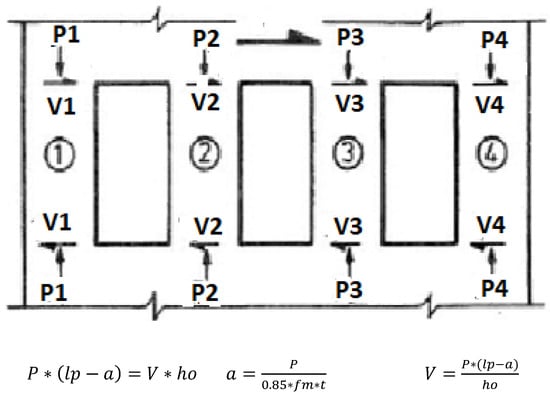

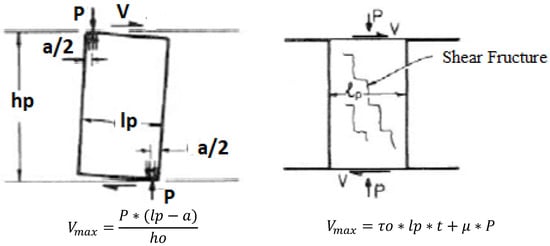

The building’s load-bearing system will be modelled, and a structural analysis will be performed under the combined effects of vertical and horizontal loads. Structural analysis can be performed using either finite element or equivalent bar methods. The method of modelling walls with shear spring rigidity allows for easy analysis using this method, which is used for the design and linear performance of masonry structures. In the example model below, the rigidities of the walls, pressure and shear forces and shear fructure and unsufficient cutting are shown as parallel shear spring elements in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 1.

The rigidities of the walls are considered as parallel shear spring elements.

Figure 2.

Wall with holes, Pressure force (Pi), and Shear Forces (Vi).

Figure 3.

Wall Block, Pressure, Shear Effects, Shear Fructure and Unsufficient Cutting.

In the analysis to be performed using the finite element method, the load-bearing wall can be modelled using detailed micro-modelling, simplified micro-modelling, or macro-modelling techniques. In the detailed micro-modelling technique, the components of the masonry wall (masonry units, horizontal and vertical mortar joints) are considered separately. In the simplified micro-modelling technique, horizontal and vertical mortar joints are neglected, and the expanded masonry units are separated from each other by average interface lines. In the macro-modelling technique, the masonry wall is considered as a composite material. Since the material considered in the model is a composite material, the ductility level is limited, linear performance analysis was used, and no analysis was performed regarding crack propagation and failure mechanisms.

In the analysis to be performed using the equivalent bar method, the rigidity of the masonry wall will be calculated by considering shear and bending deformations. The free height of the wall, H, is taken as the length from the top of the slab to the bottom of the slab (or lintel, if any). The wall length is taken as the length of the wall segment between the openings. For a rectangular cross-section wall segment, the elastic rigidity is calculated with the equation below, assuming that both ends are fixed. E and G are the modulus of elasticity and shear elasticity. A represents the horizontal cross-sectional area of the solid wall segment and I represent the moment of inertia of the solid wall segment. The Eduv value is taken as equal to 750

× fk (fk: characteristic compressive strength of the masonry wall) for the structural analysis. The shear modulus of the wall, Gduv, is taken as 40% of the modulus of elasticity.

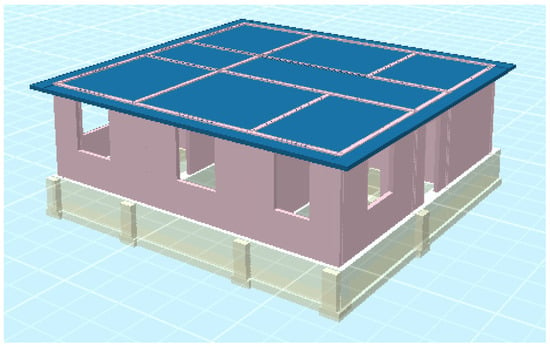

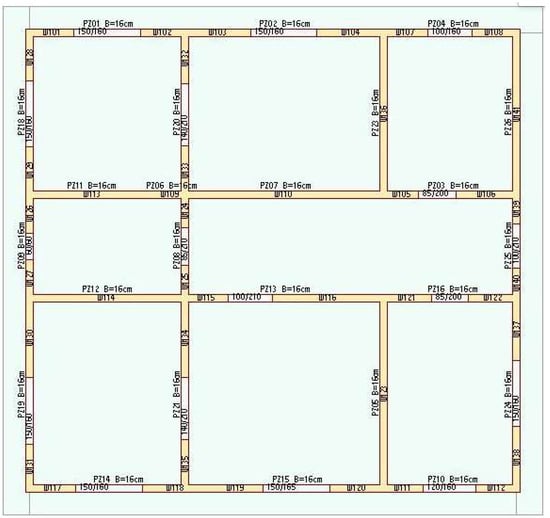

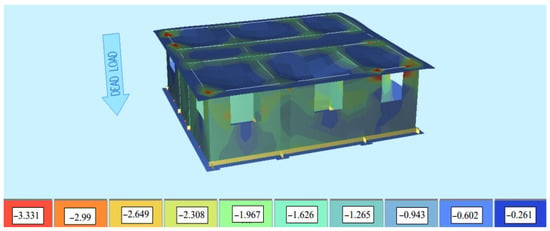

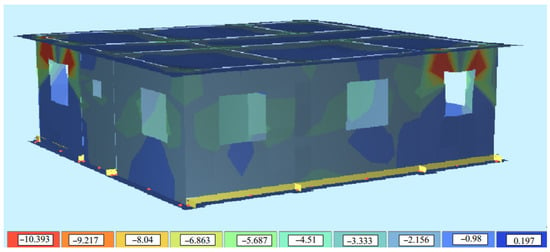

Three-dimensional views the floor plan of designed building models off the masonry building models were shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5. In load-bearing masonry walls, all joints, both horizontal and vertical, are filled with binding mortar.

Figure 4.

Three-dimensional view of designed building model.

Figure 5.

Floor plan of the building (x = 11 m, y = 10.3 m, Dimension 11 × 10.3 m).

3. Analysis of Building Models Under the Effect of Earthquake

Five different building models constructed with five different Masonry Wall Structures (MAS) were analysed under earthquake effects. The results of these analyses are presented in separate tables, graphs, and figures for each model. Seismic analyses were conducted in accordance with the 2018 TEC using Sta4Cad. The analysis results were calculated separately for the “x” and “y” directions for seismic loads and displacements in the masonry structures acting on different wall thicknesses for the building models and are presented in tables.

Analysis of the Effect of Wall Height on Masonry Structure Behaviour

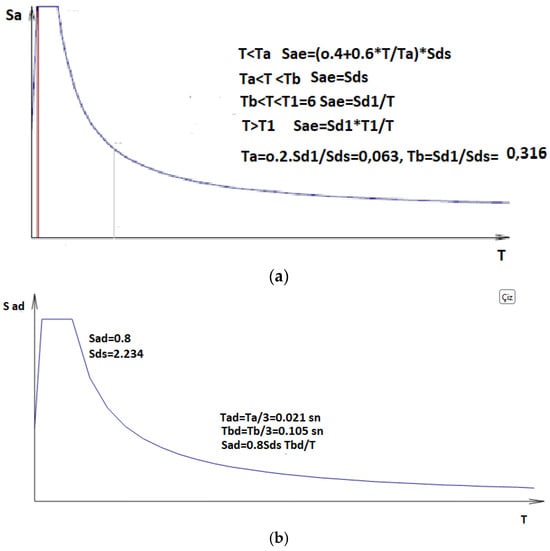

According to 2018 TEC, for solid walls, after first determining the shear stiffness of the walls and identifying the shear centres, seismic loads are distributed to the solid walls using this shear spring stiffness. STA4CAD programme has calculated matrices for brick walls as panel elements based on shear stiffness. With changes in wall thickness and wall height, shear and sliding stiffness values increase proportionally. Five different building wall heights with five different wall cross-sections were analysed under earthquake impact, and the analysis results were evaluated using separate tables, graphs, and figures for each model. The definitions of the concepts included in the analysis are provided below. Horizontal and vertical design spectrum values which were used in the analyses of the building were shown in Figure 6a,b.

Figure 6.

(a) Horizontal design spectrum. (b) Vertical design spectrum.

Abbreviations in the figures are explained below:

T = Natural vibration period of the structure [s];

TA = Horizontal elastic design acceleration spectrum corner period [s];

TB = Horizontal elastic design acceleration spectrum corner period [s];

ST(ae) = Horizontal elastic design spectral acceleration [g];

SDS = Short period design spectral acceleration coefficient [dimensionless];

SD1 = Design spectral acceleration coefficient for 1.0 s period [dimensionless];

I = Building Importance Factor;

FS = Local ground effect coefficient for short period region;

F1 = Local ground effect coefficient for 1.0 s period;

R = Structural System Behaviour Factor;

VtE = Total equivalent earthquake load (base shear force) acting on the entire building in the earthquake direction [kN];

Vtx = Maximum obtained in the x direction by one of the modal calculation methods Total seismic load [kN].

Modal analysis, equivalent earthquake method, earthquake loads and different wall thicknesses and other parameters used in the analysis for the building models created from sections with a story height of 260 cm (Reference model) were given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Analysis parameters of the model buildings.

Earthquake loads occurring according to wall height and wall thickness in masonry building models are shown below for all building models in Table 3.

Table 3.

Modal analysis equivalent earthquake load and earthquake load.

Shear forces in the “x” and “y” directions depending on the wall height and wall thickness in masonry building models are shown for all building models in Table 4.

Table 4.

Storey shear capacity control of model masonry walls.

Seismic shear forces and limited damage cases in masonry structures were evaluated according to wall height and wall thickness. In wall models, increasing the wall thickness from 16 cm to 32 cm doubles the wall cross-sectional area, naturally increasing the wall’s moment of inertia, rigidity, and shear surface area. Furthermore, since the aspect ratio of a 16 cm thick wall and a 32 cm thick wall with the same wall height is also twice as large, the shear capacity increases by 94% between the two wall models. More detailed explanations regarding this situation, including the figure, equation, and calculation approaches, are provided under Section 2 topic.

4. Discussion

In the single-storey masonry building model, the relationships between the weight of the building, the earthquake loads and shear forces occurring in the building in cases where the building has five different wall thicknesses (16, 20, 24, 28 and 32 cm) and five different wall heights (260, 280, 300, 320 and 340 cm) were examined and comparisons were made depending on these parameters. In wall models, increasing the wall thickness from 16 cm to 32 cm doubles the wall cross-sectional area, naturally increasing the wall’s moment of inertia, rigidity, and shear surface area. Furthermore, since the aspect ratio of a 16 cm thick wall and a 32 cm thick wall with the same wall height is also twice as large, the shear capacity increases by 94% between the two wall models. More detailed explanations regarding this situation, including the figure, equation, and calculation approaches.

The data obtained are shown below as a 3D graphic in Figure 7 and Figure 8 so that the changes can be compared with each other. The graph shows five different wall thicknesses ranging from 16 cm to 32 cm on the “x” axis, and five different wall heights ranging from 260 cm to 340 cm on the “y” axis. The weights, earthquake loads, “x” and “y” direction shear forces of these wall models are shown on the “z” axis, respectively. The five different wall models are represented in five different colours in the graph, allowing for comparison between them.

Figure 7.

Behaviour of MWC10 building models under earthquake effect.

Figure 8.

Behaviour of 10.MWC 54 building models under earthquake effect.

4.1. Comparative Examination of Building Parameters

Building weights, earthquake loads, and shear forces for x and y directions obtained depending on the floor heights and wall thicknesses of the examined building models were obtained are shown below in Table 5.

Table 5.

Building parameters according to wall thickness and wall height.

4.2. Behaviour of Building Models Under Earthquake Effects

5. Statistical Analysis of Earthquake Parameters

In this study, the seismic behaviour, seismic forces, shear forces, and weights of 25 different structural models were analysed for 5 different wall heights and 5 different wall thicknesses, and the results were presented in tables. Statistical analyses were performed to evaluate the results of these diverse structural models. Correlation analysis is a statistical method used to discover whether there is a relationship between two variables/data sets and how strong that relationship might be. Regression analysis is performed to determine the relationship between two or more variables that have a cause-and-effect relationship, and to make estimations or predictions about that subject using this relationship. The independent samples t-test is used to test whether there is a statistically significant difference between two independent groups by looking at their means. These analyses are generally used to identify general trends and relationships among the data.

5.1. Correlation Analysis

The results are shown below according to the He/te values for the wall height classes (Table 6).

Table 6.

Correlation coefficients between He/te and other parameters.

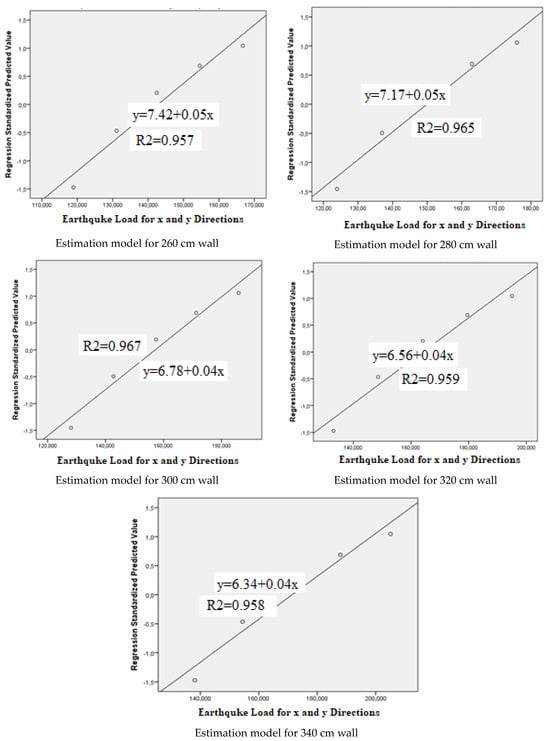

5.2. Prediction Models of the Earthquake Parameters

In the masonry building model, the earthquake loads occurring on the building were estimated according to the ratios of wall height and wall thickness (He/te). The results were shown in the table below (Table 7).

Table 7.

Summaries of earthquake load prediction models based on He/te ratios in buildings.

The significance levels of the earthquake load prediction model obtained depending on the ratio of wall height to wall thickness (He/te ratio) for the created masonry structure model were examined with ANOVA analysis and the results are shown in the table below (Table 8).

Table 8.

ANOVA analysis results for earthquake load prediction models according to He/te ratio.

The coefficients and analysis results of the earthquake load prediction models obtained depending on the ratio of the wall height to the wall thickness (He/te ratio) for the created masonry structure model are shown in the table below (Table 9).

Table 9.

Coefficients and earthquake load prediction models according to He/te ratio.

Earthquake loads were estimated depending on the wall height and wall thickness ratios, and the equations and correlation coefficients of the prediction models are shown below separately for the building models (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Estimated earthquake loads depending on the wall height and wall thickness ratios.

The proposed regression equations are empirical adaptations specific to the analysed models, obtained from the data of this study, and should not be generalised. This study also evaluates that wall height-thickness of 260–26 cm, 270–27 cm, 280–28 cm, 290–29 cm, 300–30 cm etc. It is believed that a building model designed with a ratio of He/te = 10 between story height and wall thickness can more easily meet earthquake resistance requirements. This ratio could be applicable according to the 2018 TEC. It is considered that using the statistically obtained prediction models in place of code-based seismic design would not be appropriate.

5.3. Paired Samples T-Test

Paired samples t-test was performed in our building models, taking 260 cm wall height and 16 cm wall thickness as reference, in order to determine whether there is a difference between building weights, earthquake loads and shear forces in terms of other wall heights and wall thicknesses (Table 10).

Table 10.

Paired Samples t-test results.

6. Results and Recommendations

When the weights of the building models were examined, it was seen that the minimum weight for the reference building model with a height of 260 cm and a wall thickness of 16 cm was 1159.94 kN, the heaviest building model was 2000.01 kN for the building model with a height of 340 cm and a wall thickness of 32 cm. In terms of earthquake load, it was seen that the reference building with a height of 260 cm and a wall thickness of 16 cm could carry an earthquake load of 1166.42 kN. The building model with a height of 340 cm and a wall thickness of 32 cm could carry an earthquake load of 2011.08 kN. An increase of approximately 72.41% was observed in terms of building weights and earthquake load.

When looking at the shear forces occurring in the building models due to the earthquake effect, it is seen that the minimum shear force in the “x” direction for the reference building model with a height of 260 cm and a wall thickness of 16 cm is 2024.81 kN. The maximum shear force in the building model with a height of 340 cm and a wall thickness of 32 cm is 3843.58 kN, which corresponds to an increase of approximately 88.89% compared to the reference building model.

When looking at the shear forces occurring in the building models due to the earthquake effect, it is seen that the minimum shear force in the “y” direction for the reference building model with a height of 260 cm and a wall thickness of 16 cm is 1772.38 kN. The maximum shear force in the building model with a height of 340 cm and a wall thickness of 32 cm is 3451.80 kN, which corresponds to an increase of approximately 94.75% compared to the reference building model.

In the building models examined, the ratio of wall height to wall thickness for the reference building with a height of 260 cm and a wall thickness of 16 cm was 8.12, while for the building with a height of 340 cm and a wall thickness of 32 cm, this ratio was 10.63 (see Table 9). The relationships between the He/te values, the ratio of wall height to wall thickness in the building models, and the weight of the buildings, the seismic loads they could support, and the shear forces in the “x” and “y” directions were examined. Accordingly, as the wall height/wall thickness value increased, the weight, seismic load, and loads in the “x” and “y” directions of the building models decreased (see Table 10).

Prediction models were created to estimate the seismic loads induced in buildings based on the wall height and wall thickness ratios for five different building models. The generated prediction models were found to be able to predict earthquake loads (see Table 10).

The statistical significance of the differences in building weights, seismic loads, and shear forces in the x- and y-directions of the building models was examined using a paired-samples t-test. The analysis found that the differences in building weights, seismic loads, and shear forces in the x- and y-directions between the entire building models.

The ratio of wall height to wall thickness was found to be an important parameter for the earthquake-resistant design of masonry structures. Accordingly,

In a building model with a wall height of 260 cm, when the wall thickness is 16 cm (He/te = 16.25), the weight of the structure is 1159.94 kN, the generated seismic load is 1166.42 kN, the shear force in the x direction is 2034.81 kN and the shear force in the y direction is 1772.38 kN. When the wall thickness is 32 cm (He/te = 8.125), the weight of the structure is 1635.19 kN, the generated seismic load is 1635.19 kN, the shear force in the “x” direction is 3752.28 kN and the shear force in the “y” direction is 3373.74 kN. When the wall thickness is doubled, the weight of the structure and the earthquake load it can carry increase by 1.4 times. The shear forces in the “x” and “y” directions increase by about 1.85 and 1.90 times, respectively.

In a building model with a wall height of 340 cm and a wall thickness of 16 cm (He/te = 21.25), the weight of the structure is 1346.86 kN, the generated seismic load is 1354.31 kN, the shear force in the x direction is 2034.42 kN and the shear force in the y direction is 1805.92 kN, When the wall thickness is 32 cm (He/te = 10.62), the weight of the structure is 2000.01 kN, the generated seismic load is 2011.08 kN, the shear force in the “x” direction is 3843.58 kN and the shear force in the “y” direction is 3451.79 kN. When the wall thickness is doubled, the weight of the structure and the earthquake load it can carry increase by about 1.49 times. The shear forces in the “x” and “y” directions increase by about 1.89 and 1.91 times, respectively.

Among the building models created, it can be said that the 340 cm high wall provides the highest resistance increase against earthquake loads with an increase of approximately 1.94 compared to the other models, whereas the 260 cm high wall model has the least resistance increase against earthquake loads. For masonry structures to be designed, it is crucial to determine the optimum wall height, wall thickness, and wall height/wall thickness values by considering wall height/wall thickness ratios, building weights, seismic loads and shear forces, and construction costs. Further studies that consider all these parameters and optimum conditions would be appropriate, and cost considerations should be incorporated into the design process. This will enable designs to be evaluated not only from an earthquake-related perspective but also from a cost-effective perspective.

The 2018 TEC stipulates a minimum brick wall thickness of 24 cm and a wall height-to-wall thickness ratio of 12. However, because masonry buildings are constructed in rural areas and without proper supervision, these requirements are not met. This situation can lead to masonry buildings being considered risky in terms of earthquakes. To determine the earthquake risk levels of masonry buildings, particularly those constructed in rural and economically disadvantaged areas, this study used wall thicknesses ranging from 16 cm to 32 cm (as observed in field applications) and story heights ranging from 260 cm to 340 cm to assess earthquake resistance for the worst-case scenario building models. To illustrate the situation in rural areas and highlight potential risks, 25 building models were created. Considering the minimum wall thickness of 24 cm and the wall height/wall thickness ratio of 12 cm specified in the earthquake regulations, the wall height (hef) is calculated as 12 × 24 = 288 cm. While this study could only be conducted for a single building model with a floor height of 288 cm and a wall thickness of 24 cm, in order to minimise costs in economically disadvantaged rural areas, the study examined how the seismic resistance of the building changes depending on whether the walls are thinner or thicker than the reference wall thickness of 24 cm, or whether the building has floor heights less or more than 288 cm. Therefore, wall thicknesses of 16, 20, 24, 28, and 32 cm were selected, and the seismic resistance of the building models was comprehensively investigated for these possible thicknesses. However, to observe how the seismic resistance of the structure changes when the reference floor height of 288 cm (hef = 24

× 12 = 288 cm) is not adhered to, and when floor heights are lower or higher than this, structural models were created using floor heights of 260, 280, 300, 320, and 340 cm to encompass possible scenarios. For statistical comparison tests, at least two dependent or independent groups are required. In this study, a comprehensive analysis was conducted using 25 different models—five different wall thickness models for wall thicknesses and five different wall height models for wall heights—to examine the possibilities of non-compliance with regulations. Therefore, the creation of 25 statistically significant groups constituted a very large sample size encompassing all possibilities for the analysis.

The values corresponding to the limit ratios (He/te ≤ 12) specified in Table 1 of the 2018 TEC are given in Table 2. However, as wall thickness increases, the resistance of the structure to shear forces increases because the moment of inertia, cross-sectional area, and mortar adhesion surface area of the wall also increase. The most important issue for designers is to decide which wall height to choose for which wall thickness in masonry structures and to design the structure accordingly. In this respect, it is considered that the recommended wall thickness for designers can be between 26 and 30 cm, and the wall height between 260 and 300 cm. Regulations define the minimum requirements/criteria. Therefore, it is considered appropriate that the ratio of the wall height to the wall thickness chosen for the design should be less than 12. In this case, for example, instead of choosing a wall thickness of 280/10 = 28 cm for a floor height of 280 cm (which is 23.3 cm), it is thought that designing it as such would be more suitable in terms of earthquake resistance. Because when the wall thickness is increased from 23.3 cm to 28 cm, the thickness increases by approximately 20%. This will also significantly affect the shear surface area, compressive surface area, rigidity of wall, moment of inertia, and adhesion properties of the mortar.

This study only investigated the effects of wall height and wall thickness on seismic resistance in masonry structures. It is considered beneficial to also examine wall height and thickness in terms of construction cost, material efficiency, and performance-based design objectives. In this case, a new study should be conducted to analyse different wall thicknesses, different wall heights, and different performance objectives, and how these differences affect construction costs can be revealed in another study. Thus, the effects of these parameters on the construction cost can also be determined.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Bayır, S.İ.; Özgan, E. Yığma Yapılarda Duvar Boşluk Oranlarının Binanın Deprem Davranışına Etkisi. In Teori ve Uygulamada Mimarlık, Planlama ve Tasarım; Section 4; Duvar Yayınları, Aralık: İzmir, Türkiye, 2024; pp. 61–72. ISBN 978-625-5530-84-4. Available online: https://www.duvaryayinlari.com/Webkontrol/IcerikYonetimi/Dosyalar/teori-ve-uygulamada-mimarlik-planlama-ve-tasarim_icerik_g4340_wI1WFviV.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Dolšek, M.; Fajfar, P. The effect of masonry infills on the seismic response of a four-storey reinforced concrete Frame a deterministic assessment. Eng. Struct. 2008, 30, 3186–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yön, B.; Onat, O. Failures of masonry dwelling triggered by East Anatolian Fault earthquakes in Turkey. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2020, 133, 106126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachakis, G.; Vlachaki, E.; Lourenço, P.B. Learning from failure: Damage and failure of masonry structures, after the 2017 Lesvos earthquake (Greece). Eng. Fail. Anal. 2020, 117, 104803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatar, O.; Sözbilir, H.; Koçbulut, F.; Bozkurt, E.; Aksoy, E.; Eski, S.; Özmen, B.; Alan, H.; Metin, Y. Surface deformations of 24 January 2020 Sivrice (Elazığ)–Doğanyol (Malatya) earthquake (Mw = 6.8) along the Pütürge segment of the East Anatolian Fault Zone and its comparison with Turkey’s 100-year-surface ruptures. Mediterr. Geosci. Rev. 2020, 2, 385–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingham, J.; Griftith, M. Performance of unreinforced masonry buildings during the 2010 Darfield (Christchurch, NZ). Aut. J. Eng. 2010, 11, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augenti, N.; Parisi, F. Learning from construction failures due to the 2009 L’Aquila Italy earthquake. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. ASCE 2010, 24, 536–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahya, V.; Genç, A.F. Evaluation of earthquake-related damages on masonry structures due to the 6 February 2023 Kahramanmaraş-Türkiye earthquakes: A case study for Hatay Governorship Building 2024. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 156, 107855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işık, E.; Avcil, F. Structural damages in masonry buildings in Adıyaman during the Kahramanmaraş (Turkiye) earthquakes (Mw 7.7 and Mw 7.6) on 06 February 2023. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 151, 107405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, L.; Cattari, S.; da Porto, F.; Magenes, G.; Penna, A. Seismic behaviour of ordinary masonry buildings during the 2016 central Italy. Earthq. Bull Earthq. Eng. 2019, 17, 5583–5607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, H.; Shkodrani, N.; Hysenlliu, M.; Harirchian, E. Damage and performance evaluation of masonry buildings constructed in 1970s during the 2019 Albania earthquakes. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 131, 105824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariq, M.; Abbas, H.; Irtaza, H.; Qamaruddin, M. Influence of openings on seismic performance of masonry building walls. Build. Environ. 2008, 43, 1232–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, F.; Augenti, N. Uncertainty in Seismic Capacity of Masonry Buildings. Buildings 2012, 2, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassios, T.P. Seismic engineering of monuments. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2010, 8, 1231–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, M. Earthquake response and damage patterns assessment of two historical masonry churches with bell tower. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 151, 107418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, M.; Milani, G. Seismic response and damage patterns of masonry churches: Seven case studies in Ferrara Italy. Eng. Struct. 2018, 177, 809–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghabeigi, P.; Farahmand-Tabar, S. Seismic vulnerability assessment and retrofitting of historic masonry building of Malek Timche in Tabriz Grand Bazaar. Eng. Struct. 2021, 240, 112418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krentowski, J.R.; Knyziak, P. Historical masonry buildings condition assessment by non-destructive and destructive testing. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 146, 107122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgun, T.; Ceylan, O.; Nasery, M.M.; Güler, O.; Sayin, B.; Uzdil, O.; Akcay, C. Seismic performance assessment and retrofitting proposal for a historic masonry school building (Bursa, Türkiye). Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e02087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meli, R.; Brzev, S.; Astroza, M.; Boen, T.; Crisafulli, F.; Dai, J.; Farsi, M.; Hart, T.; Mebarki, A.; Moghadam, A.S.; et al. Seismic Design Guide for Low-Rise Confined Masonry Buildings. In World Housing Encyclopedia; Publication WHE–2011–02; Earthquake Engineering Research Institute: Oakland, CA, USA, 2011; Volume 1, pp. 1–90. [Google Scholar]

- Brzev, S. Earthquake-Resistant Confined Masonry Construction, 1st ed.; National Information Center of Earthquake Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur: Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, India, 2007; pp. 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bourzam, A.; Ikemoto, T.; Miyajima, M. Lateral resistance of confined brick wall under cyclic quasi-static lateral loading. In Proceedings of the Fourteenth World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Beijing, China, 12–17 October 2008; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bourzam, A.; Goto, T.; Miyajima, M. Shear capacity prediction of confined masonry walls subjected to cyclic lateral loading. Doboku Gakkai Ronbunshuu A 2008, 64, 692–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourzam, A.; Toshikazu, I.; Saiji, F.; Masakatsu, M. Influence of RC tie-columns due to dowel action on confined masonry panels subjected to in-plane cyclic loading. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2013, 5, 1924. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, K.; Kulkarni, S.M.; Subramaniam, S.; Murty, C.V.R.; Goswami, R.; Vijayanarayanan, A.R. Build A Safe House with Confined Masonry; Gujarat State Disaster Management Authority, Government of Gujarat: Gandhinagar, India, 2012.

- Tomaževič, M.; Klemenc, I. Seismic behaviour of confined masonry walls. Earth. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1997, 26, 1059–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfura, A.P.; Flores, P.J. Quindio, Colombia Earthquake, January 25, 1999: Reconnaissance Report; Technical Report MCEER-99-0017; Multidisciplinary Center for Earthquake Engineering Research, State University of New York at Buffalo: Buffalo, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- Galvis, F.A.; Miranda, E.; Heresi, P.; Dávalos, H.; Ruiz-García, J. Overview of collapsed buildings in Mexico City after the 19 September 2017 (Mw7. 1) earthquake. Earthq. Spectra. 2020, 36, 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, B.; Singhal, V.; Kaushik, H.B. Sustainable housing using confined masonry buildings. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzev, S.; Astroza, M.; Moroni, O. Performance of Confined Masonry Buildings in the February 27, 2010 Chile Earthquake; Earthquake Engineering Research Institute: Oakland, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 1–177. [Google Scholar]

- Bilek, S.L.; Satake, K.; Sieh, K. Introduction to the Special Issue on the 2004 Sumatra–Andaman Earthquake and the Indian Ocean Tsunami. Bull. Seism. Soc. Am. 2007, 97, S1–S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcocer, S.M.; Klingner, R.E. The Tecomán, México Earthquake, January 21, 2003: An EERI and SMIS Learning from Earthquakes Reconnaissance Report; Earthquake Engineering Research Institute: Oakland, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Meisl, C.S.; Safaie, S.; Elwood, K.J.; Gupta, R.; Kowsari, R. Housing Reconstruction in Northern Sumatra after the December 2004 Great Sumatra Earthquake and Tsunami. Earthq. Spectra. 2006, 22, 777–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boen, T. Sumatra Earthquake 26 Dec 2004; Earthquake Engineering Research Institute (EERI): Oakland, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Moroni, M.O.; Astroza, M.; Acevedo, C. Performance and Seismic Vulnerability of Masonry Housing Types Used in Chile. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2004, 18, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, B.H.; Alemi, F.; Ashtiany, G. Confined Brick Masonry Building with Concrete Tie-Columns and Beams; Iran, Report 27; World Housing Encyclopaedia, Earthquake Engineering Research Institute: Oakland, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- EERI. The Tehuacan, Mexico, Earthquake of June 15, 1999. In EERI Special Earthquake Report; Newsletter, Earthquake Engineering Research Institute: Oakland, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, M.; Bommer, J.J.; Pinho, R. Seismic Hazard Assessments, Seismic Design Codes, and Earthquake Engineering in El Salvador; The Geoglogical Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez, J.I.; Villarreal, J.I.; Centeno, M.R.; Gonzalez, B.G.; Correa, J.J.G.; Acevedo, C.R.; Salazar, I.S. Tehuacan, Mexico, Earthquake of June 15, 1999. Seismol. Res. Lett. 1999, 70, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, A.E. Performance of Masonry Structures during Extreme Lateral Loading Events. In Masonry in the Americas; ACI Publication, SP 147-4; American Concrete Institute: Detroit, MI, USA, 1994; pp. 85–126. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Jian, Z. Functions of tied concrete columns in brick walls. In Proceedings of the Ninth World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Tokyo, Japan, 2–9 August 1988; Japan Association for Earthquake Disaster Prevention: Tokyo, Japan, 1989; Volume 6, pp. 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Borah, B.; Kaushik, H.B.; Singhal, V. Analysis and Design of Confined Masonry Structures: Review and Future Research Directions. Buildings 2023, 13, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, A.M.; El-Attar, A.G.; Elwaly, A. DIM for detecting Cracks in Masonry Piers with Different Crack Patterns. JES J. Eng. Sci. 2022, 50, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korswagen, P.A.; Longo, M.; Meulman, E.; Rots, J.G. Crack initiation and propagation in unreinforced masonry specimens subjected to repeated in-plane loading during light damage. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2019, 17, 4651–4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, M.; Bcattini, G.; Betti, M. Multilevel structural evaluation and rehabilitation design of an historic masonry fortress. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 63, 105379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhosis, V.; Dais, D.; Smyrou, E.; Bal, I.E.; Drougkas, A. Quantification of damage evolution in masonry walls subjected to induced seismicity. Eng. Struct. 2021, 243, 112529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Z.; Shahzada, K.; Genturk, B. Seismic Capacity Assessment of Unreinforced Concrete Block Masonry Buildings in Pakistan Before and After Retrofitting. J. Earthq. Eng 2015, 19, 357–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1998-1:2004; Eurocode 8: Design of Structures for Earthquake Resistance–Part 1: General Rules, Seismic Actions and Rules for Buildings 2004. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2004.

- EN 1998-3:2005; Eurocode 8: Design of Structures for Earthquake Resistance–Part 3: Assessment and Retrofitting of Buildings. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- IBC. Norme Tecniche per le Costruzioni (‘‘Italian Building Code’’); Ministerial Decree Dated of 17-01-2018; Ministero delle Infrastrutture Trasporti: Rome, Italy, 2018.

- TBDY 2018 Principles for the Design of Buildings Subject to Earthquake Effects, Türkiye 2018, 251. Available online: https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/mevzuat?MevzuatNo=24468&MevzuatTur=7&MevzuatTertip=5 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- STA4 CAD. Structural Analysis for Computer Aided Design; STA4 CAD: İstanbul, Türkiye, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- TS EN 772; Specification for Masonry. Turkish Standards Institute Turkish Standard: Ankara, Türkiye, 2005.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.