4.1. Shear Force and Vertical Displacement

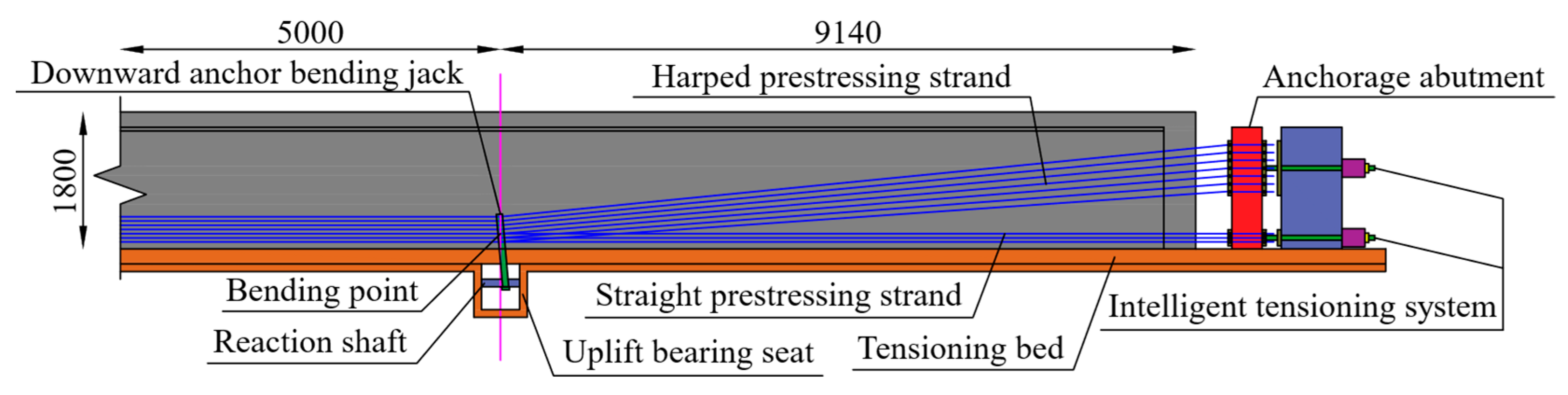

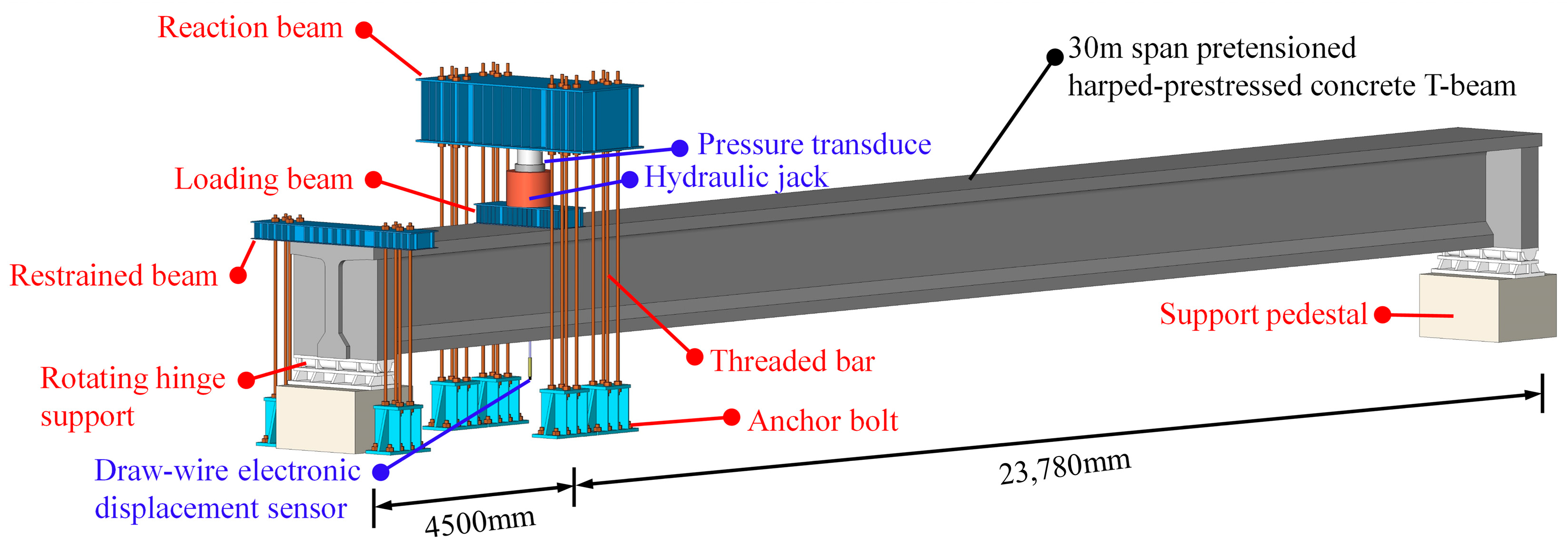

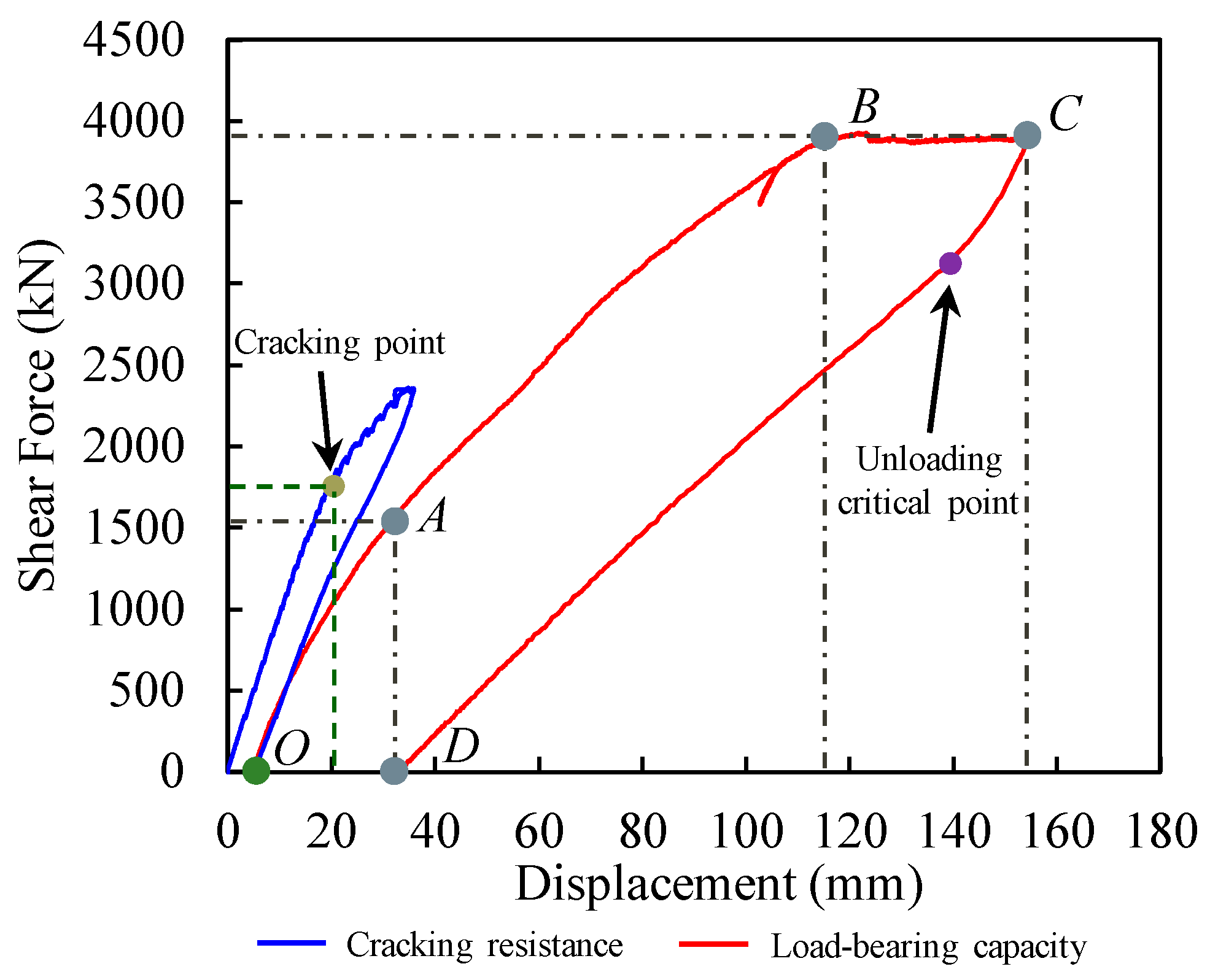

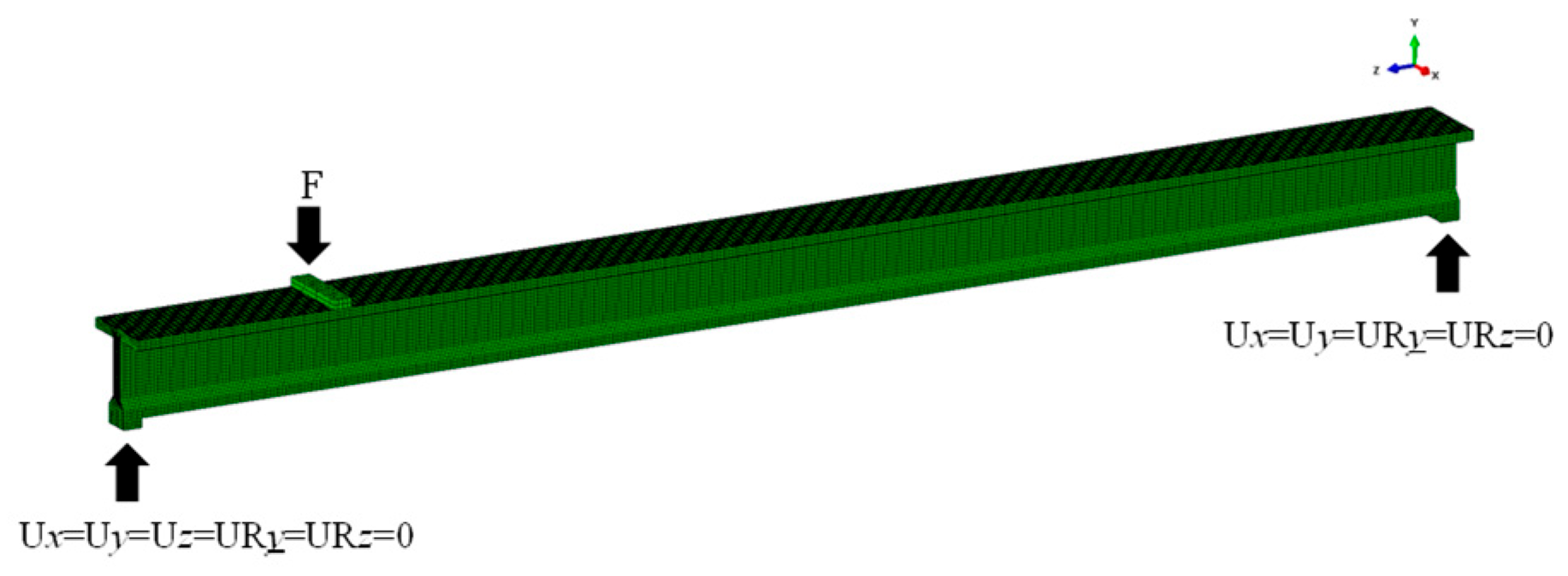

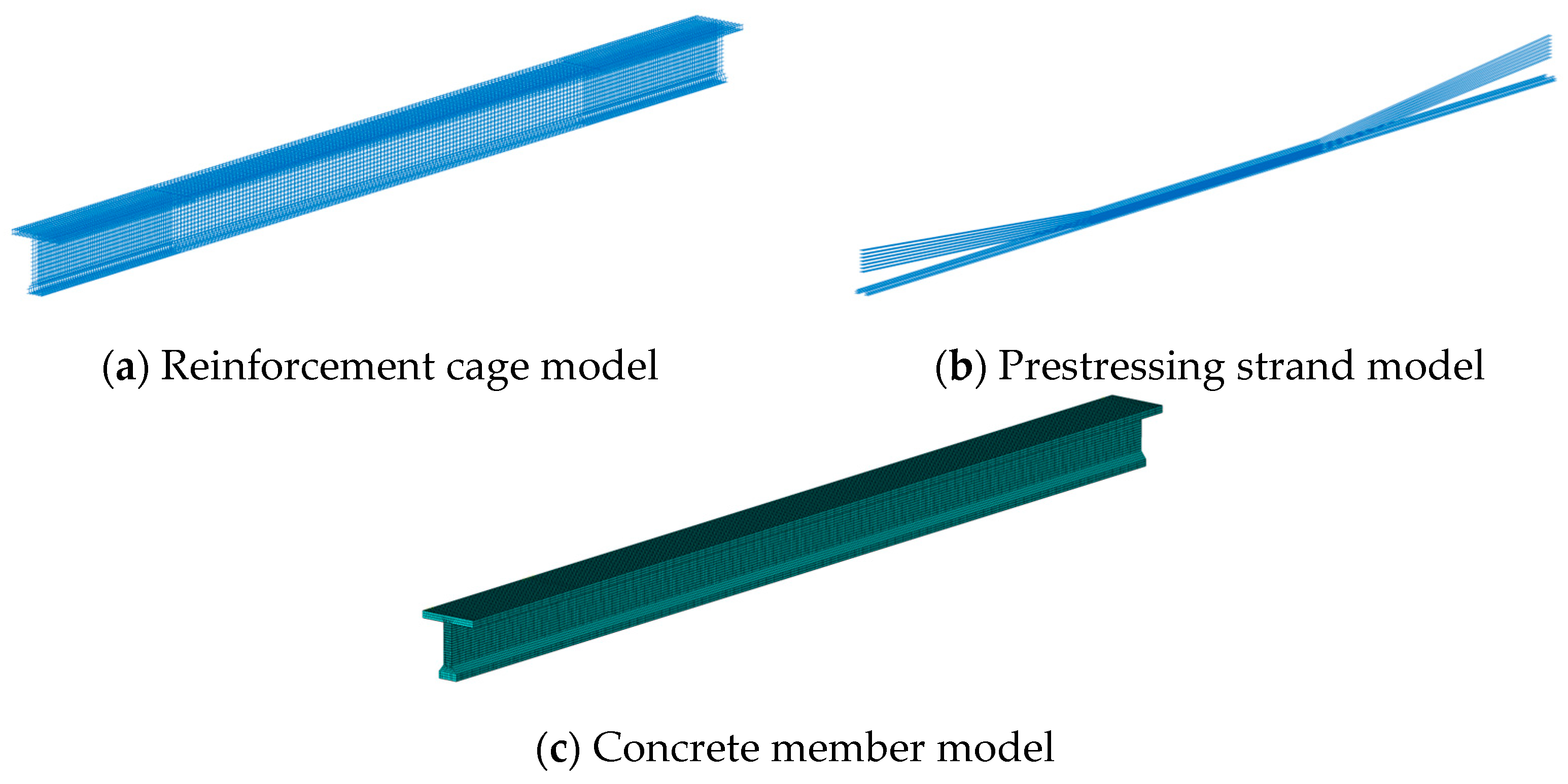

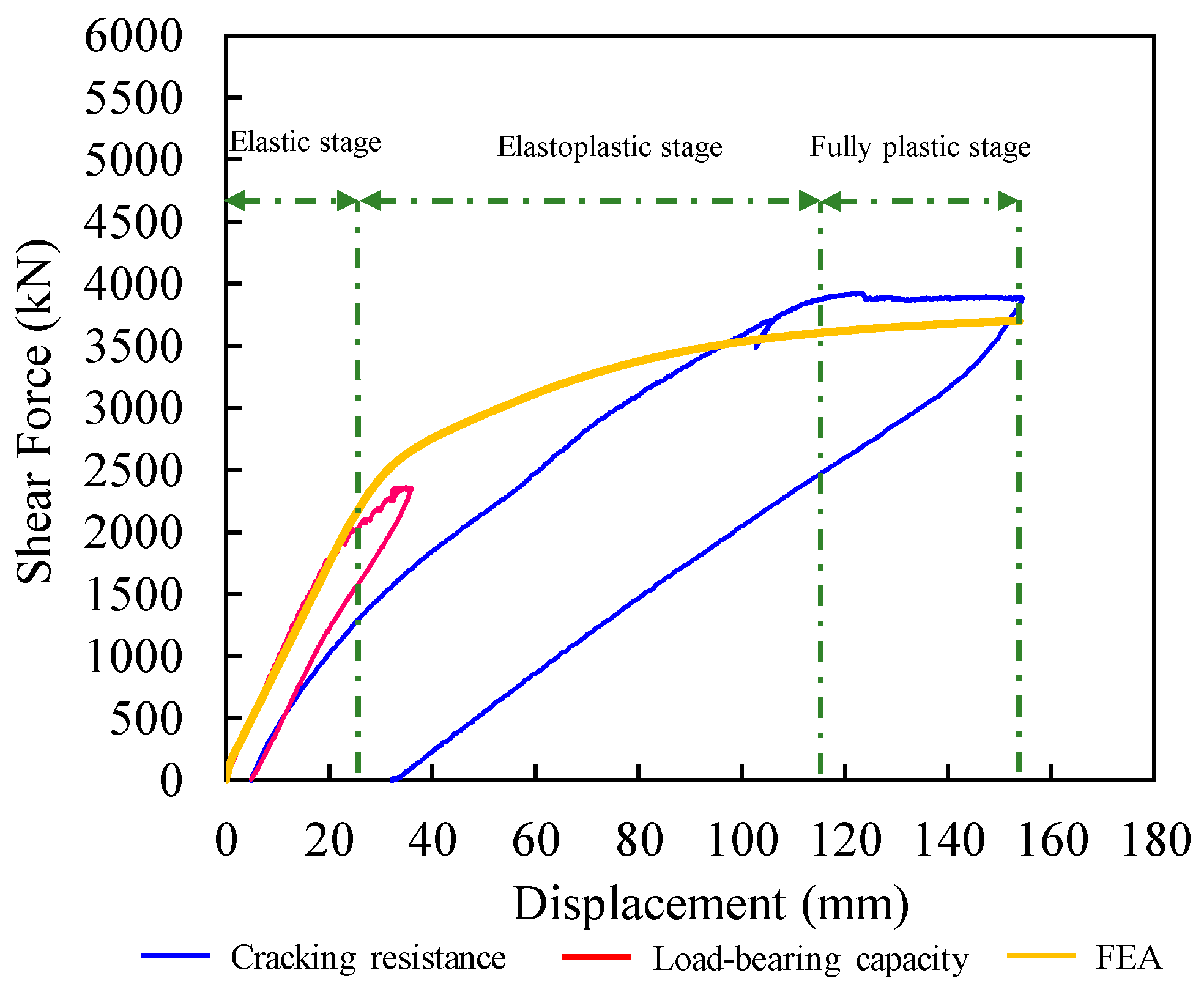

This study adopts the shear force value of the test beam segment as the representative value of the beam loading and plots the relationship curve between the shear force of the test beam segment and the displacement measurement points under a shear-span ratio (λ) of 2.5, as shown in

Figure 5.

From the shear force–displacement curve illustrated in

Figure 5, the entire process of the first loading can be broadly divided into the following three stages: the elastic stage, the cracking stage, and the unloading stage.

During the elastic stage, the load–displacement curve is essentially linear, with high shear stiffness and small deformation in the beam. When loading reached Load Case LC17 (corresponding to a load of 2100 kN and a shear force of 1766 kN in the test beam segment), a distinct inflection point appeared in the load–displacement curve. The stiffness of the test beam segment decreased, and significant nonlinear deformation occurred. At this point, fine vertical cracks began to form in the concrete near the loading section. The measured displacement at the loading section after completing this load case was 20.1 mm, indicating that the reduction in beam stiffness and the nonlinear deformation were primarily induced by crack propagation. Based on the previously described crack development, extensive shear diagonal cracks began to appear in the test beam after this load case. Therefore, this paper defines the shear force value of the test beam segment corresponding to LC17 as the experimental diagonal cracking shear force for the beam under a shear-span ratio (λ) of 2.5.

After cracking, the beam deformation increased more rapidly with further loading. Flexural–shear diagonal cracks emerged and developed quickly, while the concrete in the loading section gradually lost its load-carrying capacity. The tangent slope of the shear force–displacement curve gradually decreased but did not reach a plateau, indicating that the internal reinforcement and prestressing strands had not yielded. After completing Load Case LC24 (corresponding to a load of 2800 kN and a shear force of 2354 kN in the test beam segment), the measured displacement at the loading section was 35.9 mm, and the unloading process commenced.

During the unloading stage, the beam deformation gradually recovered. Cracks concentrated at the junctions of the web, top flange, and diaphragm, as well as flexural–shear diagonal cracks propagating from the bottom of the bottom flange, gradually closed. When the shear force at the loading section reduced to near zero, the residual displacement at the loading section was 5 mm, as shown in

Figure 5.

As shown in

Figure 6, the shear force–displacement relationship obtained from the bearing capacity test can be divided into the following stages: the slight nonlinear stage (Points O–A), the elastoplastic deformation stage (Points A–B), the plastic yielding stage (Points B–C), and the unloading stage (Points C–D).

At the initial loading stage (Points O–A), the specimen was essentially in an elastic state. However, as indicated by the reloading curve in

Figure 6, the load–displacement relationship was not perfectly linear elastic; instead, a slight degradation in stiffness gradually occurred as loading progressed. Furthermore, the shear force corresponding to the first inflection point of the curve decreased. Around loading case LU4 (corresponding to a total load of 1562 kN and a shear force of 1313 kN in the test beam segment), the specimen began to enter the elastoplastic stage, with a corresponding displacement of 26.25 mm at the loaded section. Compared to the initial loading during the crack resistance test, the shear force value at which the test beam segment entered the elastoplastic stage decreased by 11.55%. The equivalent stiffness decreased by 16.34% compared to the tangent stiffness of the initial loading.

This is primarily attributed to the irreversible changes that had already occurred in the internal structure of the test beam after the first loading cycle. During the initial loading, a concrete damage zone filled with micro-cracks had formed at the tips of macroscopic cracks, and this damage could not be fully recovered. Simultaneously, even in regions without visible cracks, multiple micro-slips and defects had developed within the concrete matrix. Although the macroscopic cracks partially closed upon initial unloading, they could not return to their original state. These micro-cracks, formed during the initial loading, created multiple stress concentration zones during the reloading process. Even though these zones experienced mutual extrusion, friction, interlocking, and shear during reloading, their mechanical performance was already compromised compared to the initial loading. All these factors contributed to the gradual development of a slight nonlinear state in the member during the early phase of reloading and a reduction in the shear force corresponding to the first inflection point.

After the member entered the elastoplastic deformation stage (Points A–B), the test beam segment exhibited significant nonlinear behavior overall. The tangent stiffness decreased markedly compared to the initial loading stage but remained relatively stable. This behavior results from several factors. Firstly, in the cracked sections, the tensile force was primarily carried by the reinforcing bars and prestressing strands, both of which exhibited essentially linear elastic behavior until reaching their yield strength. Secondly, the concrete in the compression zone had not yet reached its compressive strength during this stage, behaving approximately in a linear elastic manner. The combination of these two aspects formed a relatively stable load-bearing framework. Additionally, the existing cracks formed during the initial loading only needed to gradually reopen, eliminating the need to overcome the concrete’s tensile strength again to form new cracks. Compared to the nonlinear stage during initial loading, the equivalent shear stiffness in this stage decreased by 27.91%, indicating a reduction in the fracture energy required to propagate the cracks. Consequently, although the test beam entered the elastoplastic stage overall, the global shear stiffness remained at a relatively stable level.

When the loading reached case LU18 (corresponding to a total load of 4600 kN and a shear force of 3868 kN in the test beam segment), the specimen reached its ultimate limit state and entered the plastic yielding stage (Points B–C). At this point, the load–displacement curve reached a plateau, with the tangent stiffness essentially zero. The primary characteristic of the mechanical behavior was deformation rather than load-bearing capacity. The specimen dissipated the energy input by the loading apparatus through substantial plastic deformation, thereby achieving the intended ductile failure mode. Within the test beam segment, a plastic hinge had formed at the loaded section, leading to redistribution of internal forces, while the shear force remained essentially constant.

After undergoing significant deformation at the ultimate state, the specimen began to unload (Points C–D). During the initial phase of unloading, the recovery stiffness was high. At this time, the test beam segment was under high stress, and no significant relative slip rebound had occurred at the cracked sections. The concrete on both sides of the cracks was in tight contact, with aggregate interlock providing high contact stiffness and shear resistance. As unloading continued and the load decreased to a critical unloading point, the load was no longer sufficient to keep the crack surfaces tightly pressed together to overcome their frictional and mechanical interlocking resistance. The concrete then began to exhibit significant relative slip rebound, and the aggregate interlock effect was broken. Beyond this critical point, the crack surfaces disengaged from full interlock and entered a stage dominated by sliding friction. Subsequently, as the load continued to decrease, the frictional resistance decreased at an almost constant rate. Therefore, the unloading curve maintained a low and stable value in the subsequent range until the load was completely removed. The residual displacement at the loaded section was 32.2 mm, as shown in

Figure 6.

In addition, the design shear force of a single beam under the action of Highway Class I and secondary dead loads was calculated in accordance with the General Specifications for Design of Highway Bridges and Culverts (JTG D60-2015) [

29]. The uniformly distributed lane load was taken as 10.5 kN/m, and the pedestrian load as 3.0 kN/m. The secondary dead load was accounted for by considering a 2 cm thick asphalt surface treatment, a 6–12 cm thick C25 concrete cushion layer, and crash barriers on both sides. The lateral distribution coefficients for the Highway Class I lane load and pedestrian load were computed using the lever rule method and the eccentric pressure method, respectively, with the number of traffic lanes taken as four. After incorporating the self-weight of the structure and performing load combinations, the design shear force at the support section was determined to be 962.6 kN. The ratio of the measured cracking load to the design value was 1.835, indicating that the new type of T-beam possesses relatively excellent crack resistance.

Additionally, by inputting the relevant material, geometric, and detailing parameters of the test beam into the Specifications for Design of Highway Reinforced Concrete and Prestressed Concrete Bridges and Culverts (JTG 3362-2018) [

30] and the Design Specifications for Highway Prefabricated Concrete Bridges (JTGT 3365-05-2022) [

31], the calculated shear capacities were 2946 kN and 2925 kN, respectively. Both calculation results are conservative, with deviations from the experimental result of approximately 25%. Similarly, inputting the relevant parameters into a variable-angle truss model—which allows for setting the corresponding inclination angle of the compressive strut based on the different mechanical characteristics of the beam—yielded a calculated shear capacity of 3966 kN for the test beam. This value is in close agreement with the measured result, showing a deviation of only 2.5%. The above findings demonstrate, on one hand, that this structural form provides an increased safety margin within the current design codes. On the other hand, they indicate that the variable-angle truss model, by setting the strut inclination angle according to the specific mechanical characteristics of the beam, enables a more accurate calculation of the beam’s shear capacity. Therefore, it is recommended to adopt this model for shear capacity analysis of beams.

4.2. Crack Propagation State and Member Failure Mode

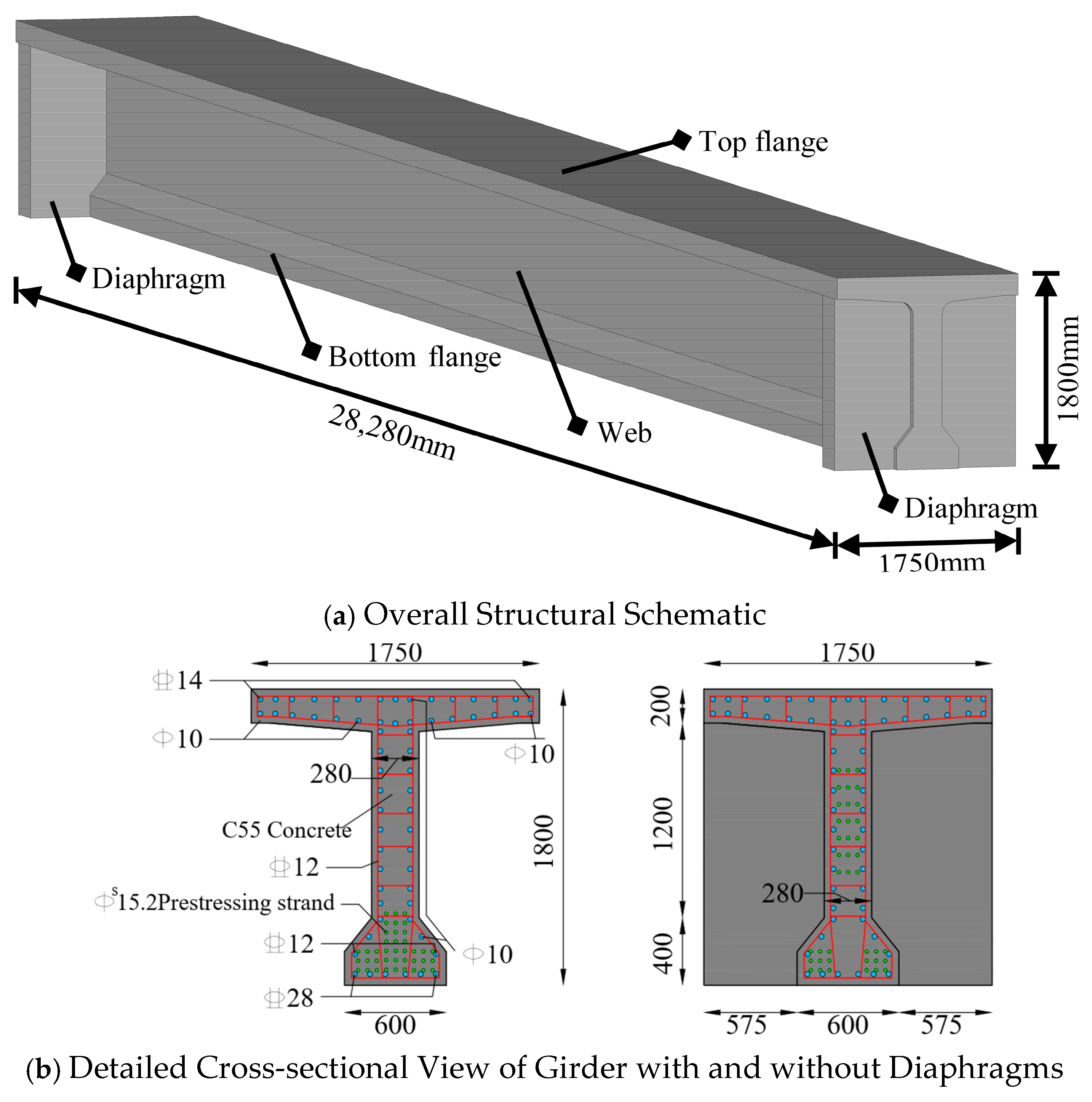

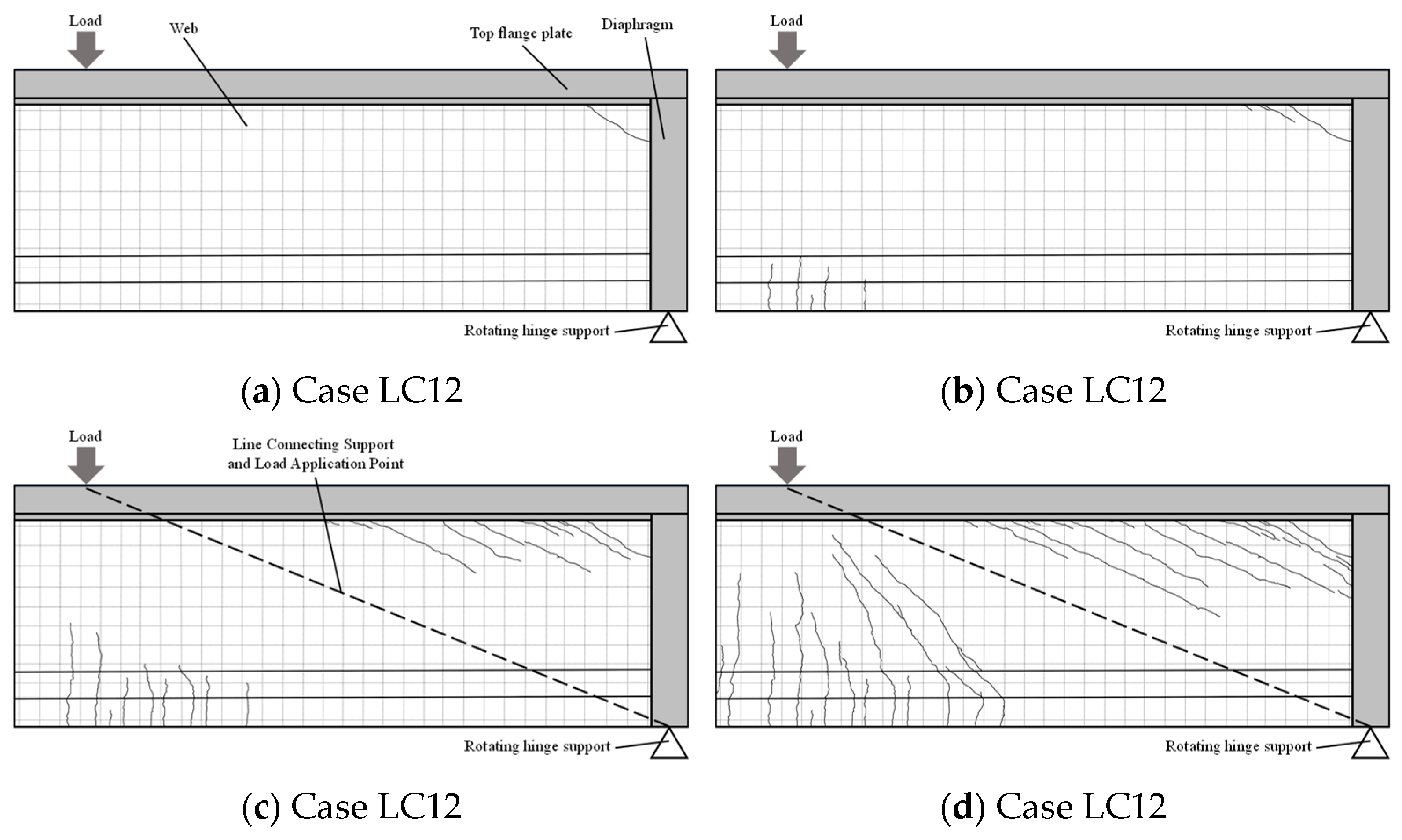

In the initial stage of the shear test loading, the test beam exhibited significant elastic characteristics, with minimal deformation observed in the beam segment. As the load was incrementally increased, a small number of micro-cracks first appeared at the junctions of the web, top flange, and diaphragm (under Working Condition LC12). The maximum crack width reached 0.12 mm, and these cracks developed obliquely from the root of the top flange toward the diaphragm, as illustrated in

Figure 7a.

With further increase in load, fine vertical flexural cracks began to emerge in the tension zone near the loading section (under Working Condition LC17). The maximum crack width in this region was 0.02 mm. However, at this stage, the widest cracks in the test beam segment were still located at the junctions of the web, top flange, and diaphragm, with a maximum crack width of 0.23 mm, as shown in

Figure 7b.

As the load continued to increase, the cracks at the junctions of the web, top flange, and diaphragm not only propagated further at their original locations (under Working Condition LC20) but also extended gradually toward the line connecting the support and the load application point. The crack paths aligned with this line, as depicted in

Figure 7c. With ongoing loading, the fine concrete cracks in the tension zone of the flexural–shear segment began to extend vertically for a short distance before developing obliquely toward the load application point. Some of these cracks approached the junction of the top flange and the web (under Working Condition LC24), demonstrating typical shear–compression failure behavior, as shown in

Figure 7d. At this point, distinct cracks had appeared in various regions of the test beam segment. The widest cracks remained at the junctions of the web, top flange, and diaphragm, with a maximum width of 0.24 mm. Additionally, as seen in

Figure 7, no oblique cracks were observed near the line connecting the support and the load application point throughout the test.

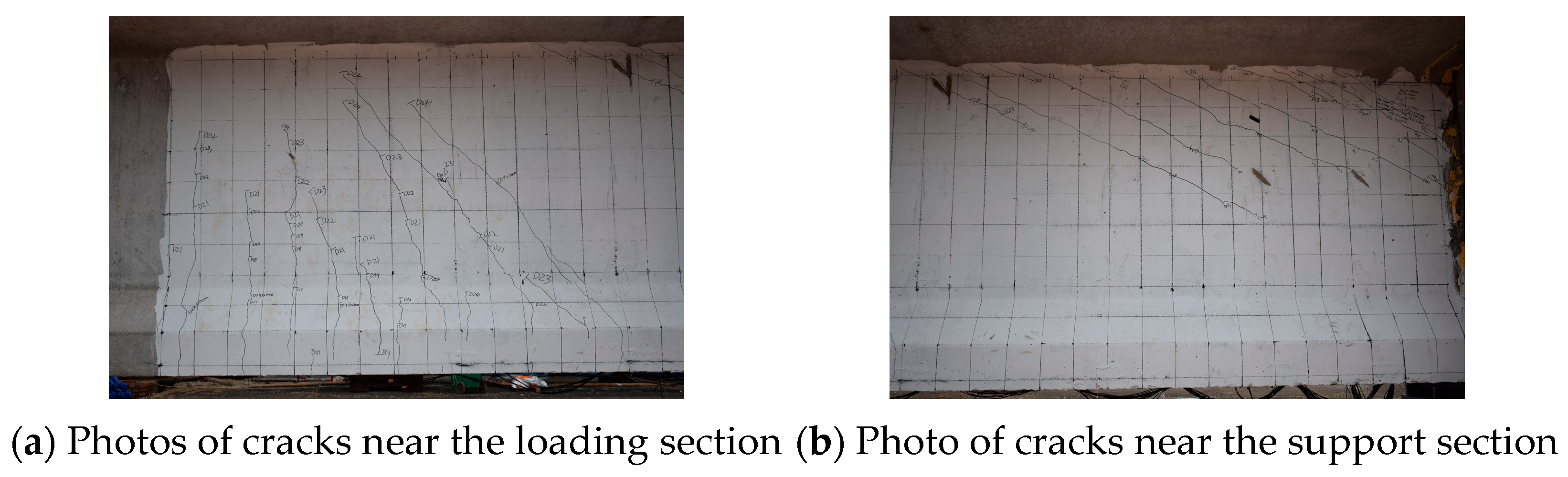

Figure 8 shows the photograph of crack development after the completion of loading in the bearing capacity test.

During the initial stage of the bearing capacity test up to the peak load of the previous shear test (2800 kN), no new crack propagation was observed in the test beam segment. Only the gradual reopening of existing cracks with increasing load was noted, reflecting the elastic recovery capability of the prestressing strands and ordinary reinforcement, as well as the crack closure effect of the concrete.

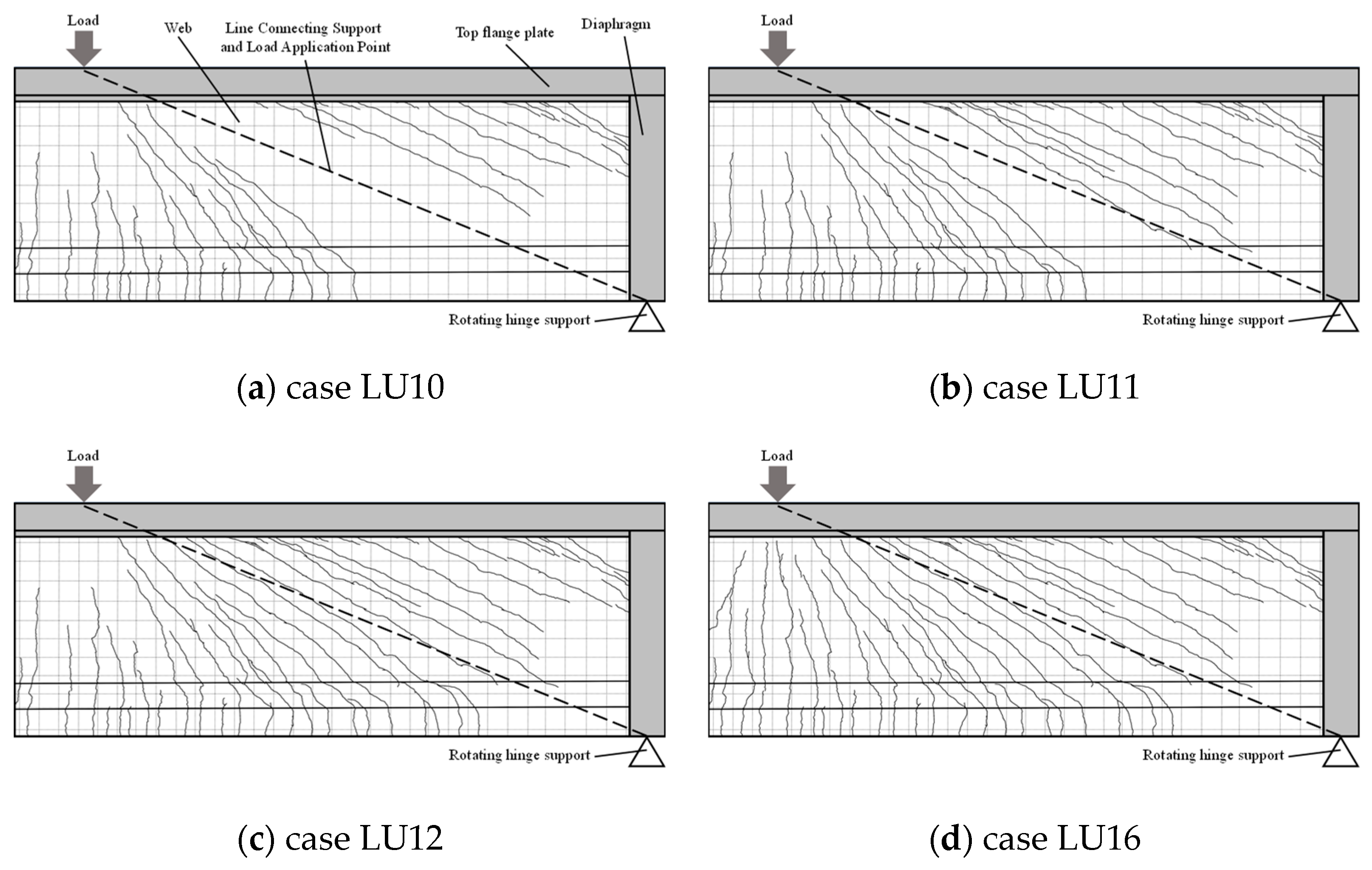

As the load exceeded the peak value of the first loading cycle, the cracks entered a propagation phase. The existing cracks extended further, gradually approaching the line connecting the support and the load application point. Inclined cracks originating from the bottom flange and extending towards the load application point reached the junction of the top flange and the web (Case LU10), as shown in

Figure 9a.

With further increase in load, inclined cracks generated from both the top and bottom flanges extended towards the respective ends of the line connecting the support and the load application point. An inclined short strut formed within the web region, while the concrete in the compression zone remained uncracked (Case LU11), as shown in

Figure 9b.

Upon additional loading, a critical diagonal crack penetrated the web formed along the line connecting the support and the load application point. Concurrently, the concrete in the web region gradually lost its load-bearing capacity, and the load was primarily resisted by the combined action of the concrete in the compression zone, ordinary reinforcement, and prestressing strands. Throughout this process, the crack widths continuously increased, yet the concrete in the compression zone remained intact until relatively high load levels were reached (Case LU12), as shown in

Figure 9c. This demonstrates the effective contribution of the polygonal tendons to the shear capacity of the structure and their restraining effect on crack development.

At the ultimate limit state, the concrete in the compressed zone of the web crushed, accompanied by a sharp increase in the overall displacement of the test beam. The load–displacement curve entered an approximately flat plateau segment, where the bearing capacity remained essentially stable while deformations continued to develop. The width of the critical diagonal crack increased rapidly, and a distinct plastic hinge mechanism formed near the loading section, indicating that the structure had entered the plastic yielding stage (Case LU16), as shown in

Figure 9d. This failure mode exhibits typical shear–compression failure characteristics. It also reflects the role of polygonal tendons in improving member ductility and shear performance. The mechanical behavior demonstrated significant stress redistribution capability and sustained shear capacity maintenance, illustrating the balance between the inherent brittle failure tendency of prestressed members and the requirement for ductility. A photograph of crack development after the completion of the bearing capacity test is shown in

Figure 10.

In conventional reinforced concrete beams, the propagation of diagonal cracks is primarily governed by the principal tensile stress exceeding the concrete’s tensile strength. The trajectory of the principal stress intuitively predicts the development path of diagonal cracks. Under the combined action of external shear and bending moments, the principal compressive stress trajectories are approximately parallel to the line connecting the load application point and the support, while the principal tensile stress trajectories are orthogonal to them. This region exhibits the highest level of principal tensile stress and is susceptible to the initiation and propagation of diagonal cracks.

Polygonal prestressing tendons apply a concentrated vertical force towards the centroid at the bending points of the concrete member. This vertical component acts in the opposite direction to the shear force induced by external loads, and its mechanical effect can be understood as introducing a reverse shear field in the web beforehand. The modification of the principal stress trajectories is specifically manifested as follows: the vertical component causes the principal compressive stress trajectories to become more “arched,” while the curvature of the principal tensile stress trajectories correspondingly decreases, becoming flatter. Most critically, this effectively reduces the principal tensile stress value along the potential diagonal crack development path and directly alters the direction of the principal stresses.

In the shear test (

Figure 7), the absence of diagonal cracks near the line connecting the support and load application point provides direct evidence that the vertical component of the prestressing force alters the principal stress distribution. The maximum principal tensile stress generated by external loads in this region is partially counteracted by the reverse effect of prestressing, preventing its value from reaching the concrete’s tensile strength for most of the loading stages. Consequently, the early appearance of diagonal cracks in this critical region is suppressed. Instead, diagonal cracks first appear in regions where the prestressing effect is weaker, such as the web, top flange, and junctions with the diaphragm.

In the bearing capacity test (

Figure 9), the formation path of critical diagonal cracks (extending from the top and bottom flanges toward the support and loading point, respectively) was also influenced by the vertical component of the prestressing force. This component, together with the internal reinforcement, established a more efficient force transfer path. Even as the concrete in the web gradually ceased to contribute, the concrete in the compression zone remained intact until higher load levels. This demonstrates that the vertical component effectively shared shear forces, delayed the crushing of the concrete in the compression zone, and allowed the member to undergo a longer plastic deformation process before failure (evident as a plateau in the load–displacement curve). This phenomenon results from an optimized internal force transfer mechanism following the redistribution of principal stresses.

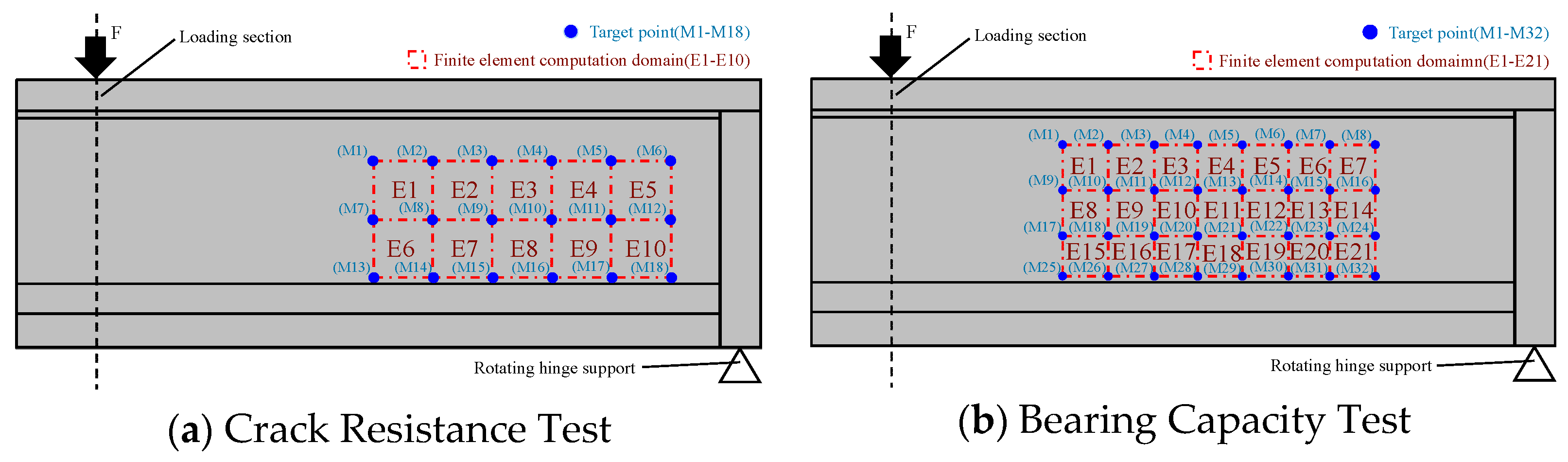

4.3. Beam Strain

In this test, target points of the NDI device were placed on the surface of the concrete web within the shear-span region to capture the specific displacements of each point during the step-by-step loading process. The average principal strain of the rectangle formed by the target points was calculated based on the theory of the 4-node rectangular element. For a 4-node rectangular element, each node has two degrees of freedom (displacements in the x and y directions), so the total displacement vector of the element is

In the above equation,

ui and

vi represent the displacements of the i-th node in the x and y directions, respectively. For a 4-node rectangular element, the shape function

N is defined in the natural coordinate system (

ξ,

η) as follows:

For plane problems, the nodal displacements can be related to the strains within an element through the strain–displacement matrix

B [

32]. By taking the centroid of the element as the calculation point for strain, the strain vector at this point and the corresponding form of the

B matrix are expressed as follows:

In this equation, a and b represent the side lengths of the rectangular element along the x and y axes, respectively; ξn, ηn denote the natural coordinate system coordinates of the four corner points, which are i (−1, −1), j (1, −1), k(1, 1), and m (−1, 1); the coordinate at the centroid is (ξ, η) = (0, 0).

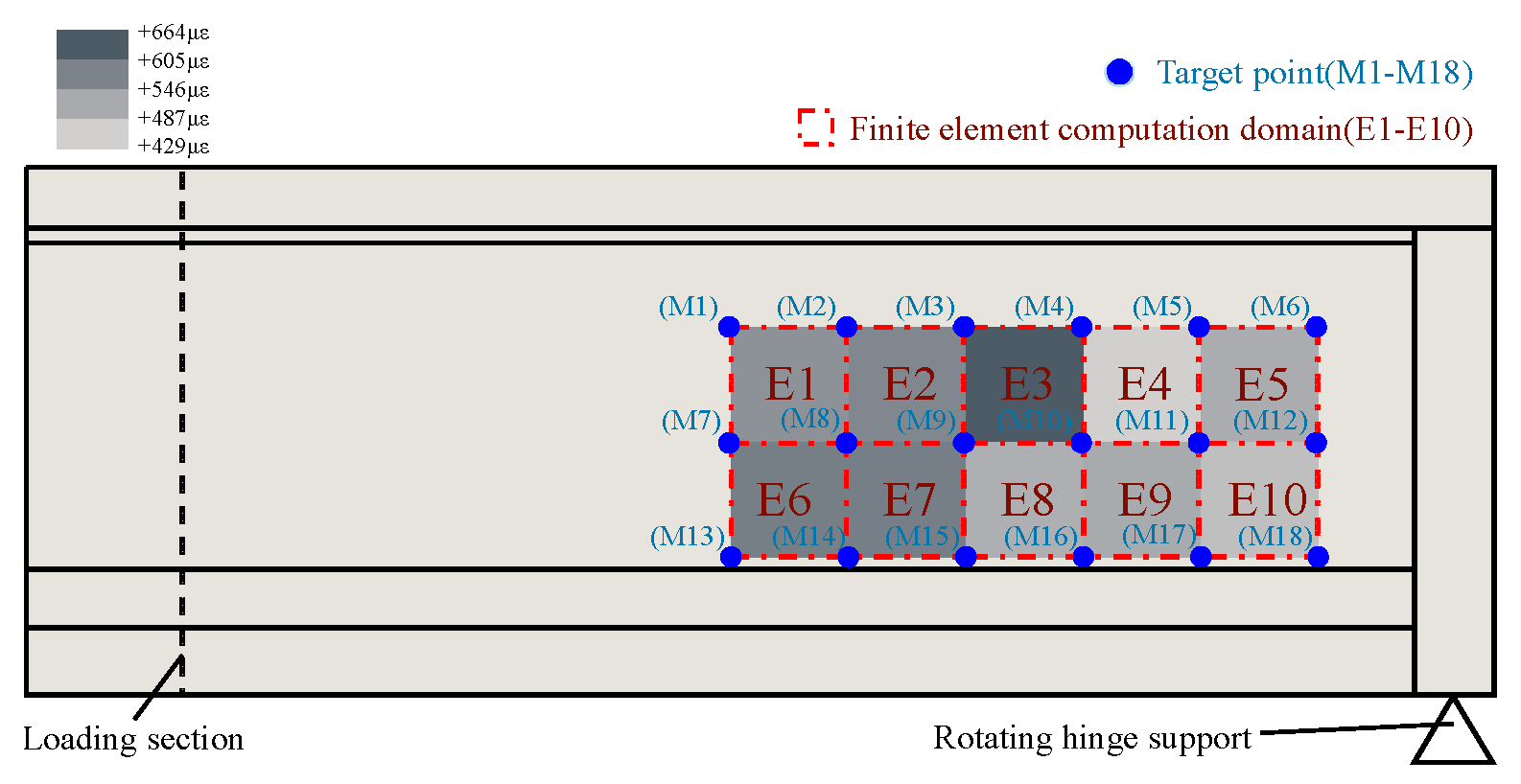

The principal strains of the rectangular elements in the web can be calculated by substituting the strain components

εx,

εy, and

γxy into the principal strain formula. The cloud diagrams of the principal strains for elements numbered E1 to E10 under the cracking load are shown in

Figure 11.

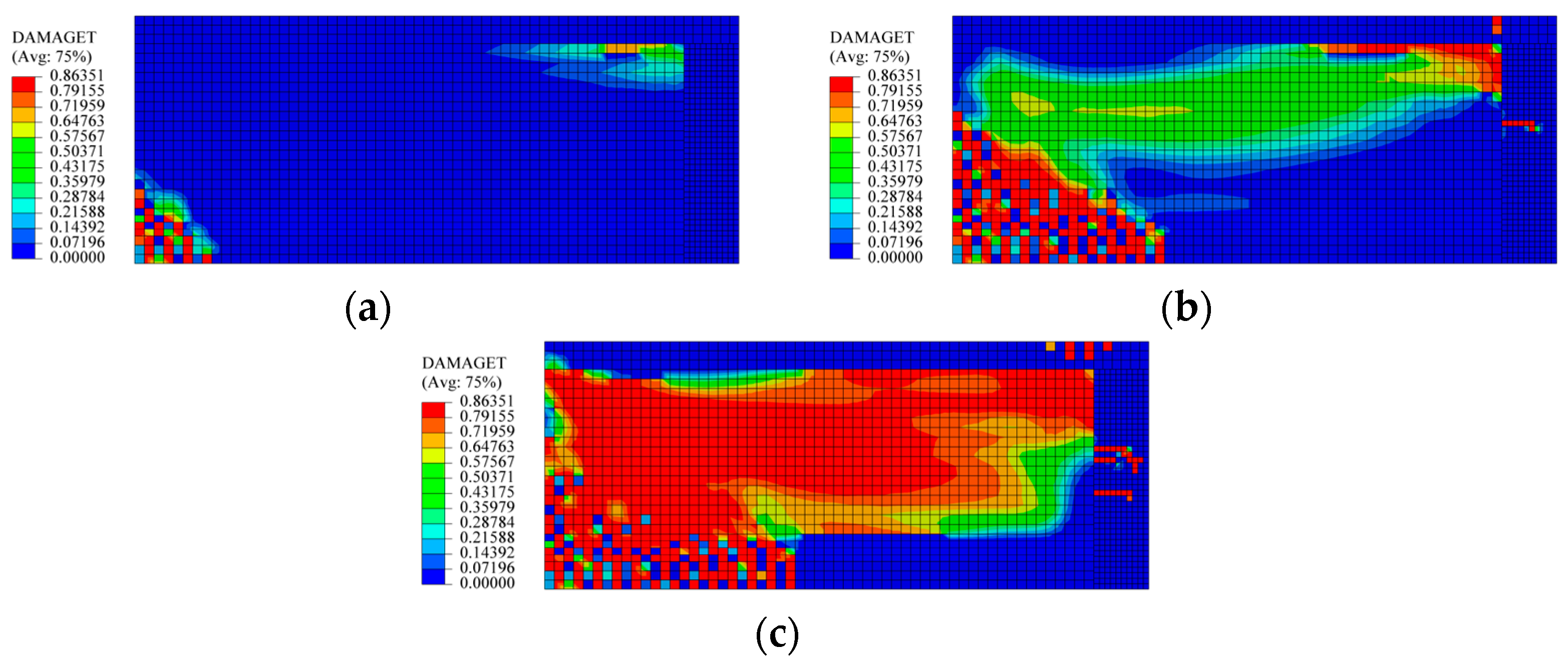

Since the computational domains of elements E1–E5 are largely covered by the crack propagation zone in the upper part of the beam web, their variation trends are generally similar. A sudden strain change occurs between load case LC17 (shear force of the test beam segment: 1766 kN) and LC18 (shear force of the test beam segment: 1850 kN), indicating that the concrete in this region exhibits significant nonlinear characteristics in its average strain trend due to cracking.

The strain variations of elements E6–E10 remain essentially consistent throughout the entire loading process. Their computational domains hardly overlap with the crack propagation zone. Therefore, the average principal strain of these elements is always much smaller than that of elements E1–E5 under the same load cases, and only minor abrupt changes occur in some final load cases. This indicates that no significant cracking occurred in the concrete of this region during loading.

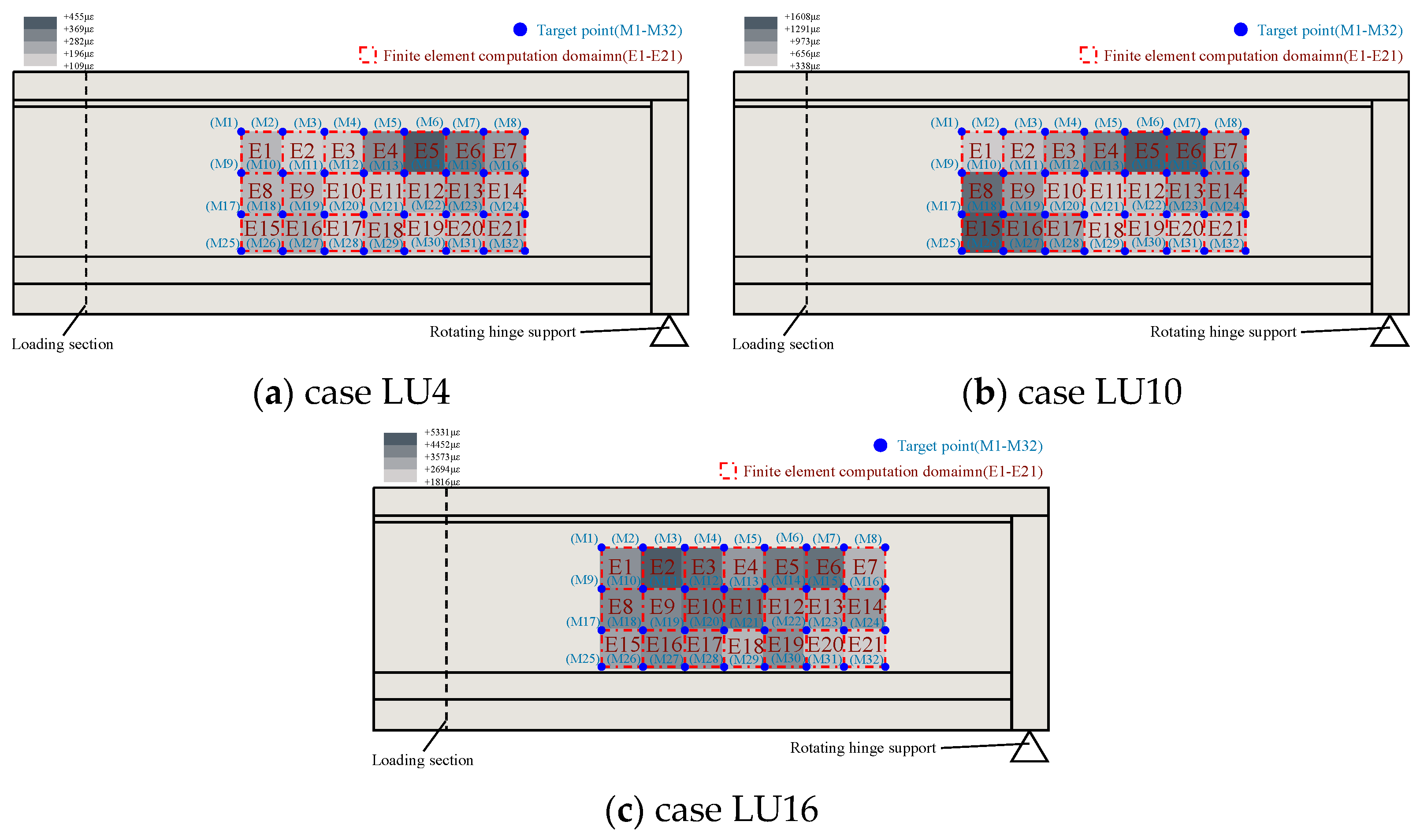

The minute displacements of target points (M1–M32) measured by the NDI equipment during the bearing capacity test were substituted into Equations (1)–(5) for calculation, yielding the average principal strains of each 4-node rectangular element (E1–E21) throughout loading cases LU1 to LU16. The cloud diagrams of average principal strain for each element under loading cases LU4, LU10, and LU16 are shown in

Figure 12. Throughout the entire loading process, the evolution of average principal strain in the rectangular elements of the test beam’s web exhibited distinct stages, closely associated with damage accumulation and internal force redistribution.

From no-load to Load Case LU4 (shear force in the test beam segment is approximately 1313 kN), the member exhibited primarily elastic behavior. The average principal strains of all elements increased slowly and linearly, indicating no significant degradation in the overall structural stiffness during this loading stage. The specific response is illustrated in

Figure 12a.

As the load increased and the member entered the elastoplastic stage, existing cracks gradually reopened. This led to a notable acceleration in the strain growth rate of elements directly intersected by the initial cracks (such as E4 to E7 and E15). However, the overall strain values were slightly lower than those during the first loading. This can be attributed to the fact that, although friction and aggregate interlock along the original crack surfaces provided some shear resistance, the overall stiffness was significantly lower than that of the intact concrete.

When the load further increased to Load Case LU10, the majority of the original cracks had fully reopened, and new cracks began to propagate outward from the vicinity of the original crack zones. Consequently, elements previously not directly affected by cracking (such as E2, E3, E16, E17, and elements in the mid-height of the web except E10) experienced a sudden increase in strain. This reflects the progressive spread of damage and the intensification of internal force redistribution, as shown in

Figure 12b.

By Load Case LU12 and beyond, critical diagonal cracks had fully developed and propagated through elements such as E10. These elements, located in key regions of the shear transfer path, exhibited a sharp increase in strain. After the concrete ceased to contribute effectively, shear forces were primarily resisted by the reinforcing bars and prestressing strands, leading to significant strain concentration.

Throughout the loading process, the evolution of the average principal strain in the rectangular elements of the test beam’s web displayed distinct stages closely associated with damage accumulation and internal force redistribution. During secondary loading, the premature reopening of cracks reduced the fracture energy demand and accelerated strain development. In the plastic stage, reinforcing bars and prestressing strands carried the majority of the tensile forces, resulting in strain concentration along the critical main crack paths. Ultimately, concrete crushing and the formation of plastic hinges led to deformation localization in critical regions. The overall behavior was characterized by a combined response of shear stiffness degradation, strain localization, and internal force redistribution.

Furthermore, from the perspective of quantitative strain analysis, the elements with the most concentrated and rapidly increasing strain (such as E10) are located along the path of the ultimately formed critical diagonal crack. This phenomenon quantitatively demonstrates that after the redistribution of internal forces, the transfer of forces eventually concentrates along the critical path dominated by reinforcing bars and prestressing tendons. The vertical component of the prestressing force alters the principal stress trajectories in the early stages, delaying the initiation of cracks; in the later stages, it works in conjunction with conventional reinforcement to form a more effective shear resistance mechanism.