Abstract

The article presents the results of a comprehensive full-scale investigation of the influence of solar radiation on the thermal behavior of the exterior envelope systems of two residential buildings of different heights—a 9-storey building in Turkestan and a 25-storey building in Shymkent. The façade systems of both buildings consist of a multilayer enclosure with a ventilated air cavity, 100 mm wide in the 9-storey building and 50 mm wide in the 25-storey building. The objective of the study was to determine the diurnal and vertical dynamics of temperature fields, analyze the thermal inertia of the materials, and assess the effect of façade geometry on heat-transfer performance. Thermographic measurements were carried out during key periods of the day (7:00, 10:00, 13:00, and 17:00), which enabled coverage of the full solar-insolation cycle. The results showed that the maximum temperatures of the external cladding reached 48–52 °C for the 9-storey building and 53–58 °C for the 25-storey building, with a vertical temperature gradient of 3–7 °C. The temperature of the interior surface varied within 28–32 °C and 29–34 °C, respectively, reflecting the influence of both solar heating and the width of the ventilation cavity on heat transfer. It was found that reducing the air-gap width intensifies natural convection and decreases the thermal inertia of the system, resulting in sharper temperature fluctuations. The study demonstrates that current design standards insufficiently account for the vertical non-uniformity of solar exposure and the aerodynamic processes within the ventilation channel. The findings can be used in the design of energy-efficient façade systems, in the refinement of regulatory methodologies, and in the development of heat-transfer models for high-rise buildings under conditions of increased solar radiation.

1. Introduction

Since the early stages of architectural development, the external envelope of buildings has played a fundamental role in protecting humans from environmental impacts. Throughout history, its structural form and the materials used have undergone profound transformations—from primitive natural stones, clay blocks, and wooden components to modern multilayer façade systems integrating innovative thermal insulation and energy-efficient solutions [1,2,3]. The evolution of building envelopes is closely linked to climatic and technological factors: each historical period introduced its own materials and structural approaches aimed at achieving thermal comfort, durability, and architectural expression [4,5,6]. In recent decades, the development of façade technologies has become particularly dynamic under the influence of global trends in energy-efficient and sustainable construction. In cold climatic zones, the key parameters of external building envelopes traditionally include structural thickness and the performance of the thermal insulation layer, which together reduce heat loss. In contrast, in regions with hot or sharply continental climates, characterized by significant daily and seasonal temperature variations, ensuring thermal comfort requires a comprehensive approach [7,8,9]. Here, the building envelope must not only minimize heat loss during winter but also prevent indoor overheating in summer, enabling dynamic regulation of heat transfer depending on external conditions [10,11]. The historical development of façade systems has led to the widespread adoption of ventilated façades, which have demonstrated high performance in various climatic environments. Systems with a ventilated air cavity provide natural thermal regulation by convectively removing excess heat and exhibit strong insulating capacity while preserving the architectural expressiveness of the building. Despite their higher cost compared with traditional façade solutions, numerous studies confirm their substantial potential for reducing energy consumption and enhancing the durability of building envelopes [12,13].

The current stage of building physics development is characterized by increased attention to the effects of solar radiation on the thermal balance and energy performance of façades. As building height increases and the proportion of glazed and ventilated surfaces expands, the task of analyzing the distribution of solar radiation along the façade height and its influence on temperature fields, heat fluxes, and structural stability becomes increasingly relevant. It has been established that the intensity of solar irradiation varies significantly with height, creating non-uniform thermal loads that affect both the performance of envelope components and the indoor microclimate [14]. In this context, a comprehensive analysis of the impact of solar radiation on thermal processes in façade systems—including the distribution of temperature fields, the dynamics of heat transfer, and the stability of building envelopes at different height levels—has become an important direction of modern scientific research. Recent years have seen a substantial increase in the number of scholarly publications devoted to this topic, indicating growing interest in developing energy-efficient architectural solutions adapted to local climatic conditions. A review of the literature reveals the evolution of approaches to modeling thermal processes under solar radiation, as well as key regularities and existing limitations. For example, the study by Martínez-Rubio A. et al. [15], employing LiDAR technology, demonstrated that the intensity of solar radiation on façades varies considerably depending on building orientation and height. Higher zones exhibit greater radiation density, particularly on south- and west-facing surfaces, resulting in increased thermal loads and the need for heat-accumulating and reflective materials. The authors’ algorithm enabled the generation of detailed irradiance maps applicable for optimizing photovoltaic systems and selecting façade materials with regard to solar exposure. Experimental research conducted by Stazi F. et al. [16] and Sánchez M. et al. [17] showed that increasing the height of the ventilation cavity in a ventilated façade (up to 12 m) enhances natural convection and reduces the internal surface temperature by 4–10 °C. At the same time, airflow velocity and cooling efficiency increase proportionally with façade height. However, an effect saturation is observed in the upper part, indicating the need to optimize façade geometric parameters [18]. The works of Ciampi M. et al. [19] and Sanjuan C. et al. [20] confirmed that ventilated façades with open joints effectively reduce heat fluxes due to the chimney effect caused by solar heating of the external cladding. Thermal inertia of the cladding and the size of the air gap are strongly dependent on structural height and solar irradiation intensity. Particular interest lies in the study by Alqaed S. [21], which examines the annual solar radiation influence on façades incorporating phase-change materials (PCM). It was found that integrating PCM into double-skin façades reduces energy consumption by 5–11% during hot periods and up to 40% during cold periods, especially when the materials are placed in the upper façade zones, where the greatest thermal fluctuations occur. Studies by Tao Y. et al. [22,23] and Lin Z. et al. [24] confirmed that the angle of solar incidence and façade height directly affect natural ventilation and the distribution of temperature fields. At high solar angles (up to 75°), the effect of multiple reflections intensifies, causing localized heating in upper façade sections and necessitating adjustments to the thermal insulation and optical properties of materials. For buildings exceeding 8–10 stories, these factors become decisive in the design of natural ventilation and passive cooling systems [25]. Experimental studies by Fantucci S. et al. [26] and De Masi R. et al. [27,28] demonstrated that under strong solar radiation, opaque ventilated façades can reduce thermal loads on internal walls by 30–70%, with the height of the cavity and the configuration of louvers having a significant influence on heat-exchange efficiency. Taller façades provide a stable upward airflow, enhancing the thermal inertia of the system [29].

The analysis of current research demonstrates that the influence of solar radiation on building façades exhibits a pronounced vertical non-uniformity. The intensity of irradiation changes along the height of the structure, causing variations in temperature fields and heat fluxes between the lower and upper zones. The upper sections of the façade, particularly those facing south and west, receive greater solar exposure, which leads to localized overheating of the cladding and alters the behavior of natural ventilation within the ventilated cavity [13,14].

The studies by Martínez-Rubio A. [15], Stazi F. [16], and Tao Y. et al. [22,23] confirm that convective processes and the chimney effect intensify with increasing façade height; however, their intensity is not linear—at a certain level, flow stabilization occurs, leading to a reduction in heat transfer. This highlights the need to account for height-dependent variations when designing façade systems.

Current thermal engineering standards do not fully reflect this effect: for the cold season, only averaged aerodynamic parameters are considered, while for the warm season, calculations typically include only the amplitude of temperature fluctuations without analyzing the distribution of solar irradiation along the façade height. As a result, the calculated values do not adequately represent the actual heat-transfer processes occurring in façade systems.

From a scientific perspective, there is a need to develop comprehensive heat and mass transfer models that incorporate the vertical distribution of solar radiation, the dynamics of airflows, and the specific characteristics of the thermal balance. At this stage, it is advisable to conduct full-scale experimental studies of solar irradiation on façades with different orientations and building heights in order to clarify the regularities of radiation load variations along the height and their impact on the performance of ventilated systems. The findings obtained will subsequently make it possible to improve computational models and regulatory approaches to the design of energy-efficient façades, which is particularly relevant for the sharply continental climate of Kazakhstan.

2. Materials and Methods

To conduct full-scale studies aimed at examining the influence of solar radiation on the façades of high-rise buildings, two representative objects were selected in the southern regions of the Republic of Kazakhstan—areas characterized by the highest levels of solar irradiance. The buildings are located within the geographical latitudes between 42°00′ and 44°00′, which makes it possible to characterize the specific features of solar exposure under sharply continental climatic conditions. The investigations were carried out during the hottest period of the year to capture the maximum radiation loads on the façade structures. As experimental sites, a 9-storey building in the city of Turkestan (Figure 1a) and a 25-storey building in the city of Shymkent (Figure 1b) were selected, with the hottest month chosen as the observation period in accordance with [30,31]. These buildings differ in height and architectural design, which enables an assessment of the influence of building height and orientation on the distribution of solar radiation over façade surfaces. Both buildings have an eastern orientation.

Figure 1.

Building façades: (a) 9-storey building in Turkestan (Option 1); (b) 25-storey building in Shymkent (Option 2).

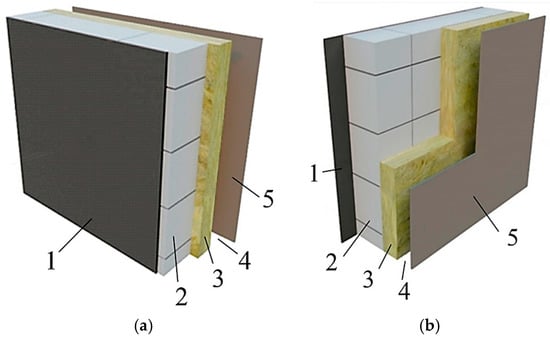

The structural solutions, geometric parameters, and thermophysical characteristics of the external building envelope for the examined structures are presented in Figure 2 and Table 1. These include the main elements of the façade systems, the types of materials used, the thickness and configuration of the envelope layers, as well as the values of thermal conductivity, heat absorption, vapor permeability, and density.

Figure 2.

Structural configuration of the external building envelope. (layer names 1–5 are presented in Table 1): (a) interior surface of the envelope; (b) exterior side of the envelope.

Table 1.

Geometric parameters and thermophysical characteristics of the external building envelope.

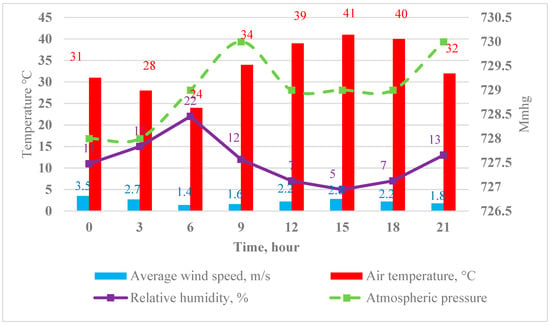

The key climatic conditions recorded during the full-scale surveys are presented below. The climatic parameters observed at the two sites were practically identical at the time of the investigation; therefore, they are combined into a single graph shown in Figure 3. The graphs illustrate the meteorological parameters that directly affect the intensity of solar radiation and the thermal behavior of façade structures, including ambient air temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed and direction. These data were obtained using automated meteorological stations [31] and characterize the weather conditions typical of the study period—the hottest month of the year. The climatic parameters presented form the basis for analyzing the distribution of solar energy along the façade height and for assessing the relationship between external climatic influences and temperature variations in the building envelope components.

Figure 3.

Key climatic parameters.

To perform a comprehensive analysis of the influence of solar radiation on the thermal stability of the external building envelopes, the full-scale observation program was structured into two consecutive stages. At the first stage, the impact of direct and diffuse solar radiation on the exterior façade surface was examined, taking into account façade orientation and geometric characteristics. The objective of this stage was to determine the patterns of solar flux distribution and to identify zones of increased radiative load on the façade surface.

At the second stage, the influence of solar radiation on the internal temperature of the external building envelope was investigated, allowing for an assessment of the thermal inertia of the materials and the nature of heat transfer through the multilayer façade structure. Measurements were carried out simultaneously on both the exterior and interior surfaces to determine the dynamics of temperature gradient variations within the construction.

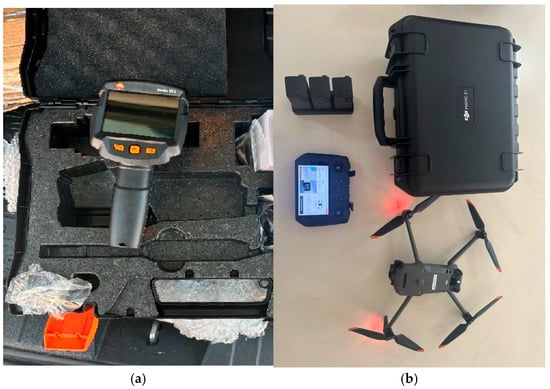

To enhance the reliability and representativeness of the data obtained, observations were conducted throughout the day, with the results presented for the most characteristic periods—7:00, 10:00, 13:00, and 17:00. This made it possible to cover the complete daily insolation cycle and to determine how the thermal state of the envelope changes depending on the sun’s position and radiation intensity. During the thermophysical surveys, a set of high-precision measuring instruments was used to record temperature fields on the surfaces of the external building envelopes, ensuring high accuracy and spatial detail of the data. For examining façades at low and medium heights, a Testo 871 thermal imager (Figure 4a) was employed, equipped with a highly sensitive infrared detector and real-time thermal anomaly visualization. This device enabled the recording of temperature distribution with an accuracy of ±0.1 °C and facilitated thermographic analysis of thermal inhomogeneities caused by solar radiation and variations in the thermophysical properties of the materials.

Figure 4.

Thermal imaging equipment: (a) Testo 871 thermal imager; (b) DJI Mavic 3 Enterprise Thermal quadcopter.

For surveying the façades of high-rise buildings, where contact and ground-based measurements were difficult to perform, a DJI Mavic 3 Enterprise Thermal quadcopter (Figure 4b) equipped with a high-resolution integrated thermal camera and stabilization system was used. The application of the unmanned aerial vehicle made it possible to carry out thermal imaging at various height levels of the façade, ensuring the acquisition of reliable data on the distribution of temperature fields along the entire height of the building.

The combined use of a ground-based thermal imager and an aerial imaging system provided an integrated approach to studying the thermal characteristics of the façade structures, enabling a comparison of local and height-dependent features of heat transfer under the influence of solar radiation.

3. Results and Discussion

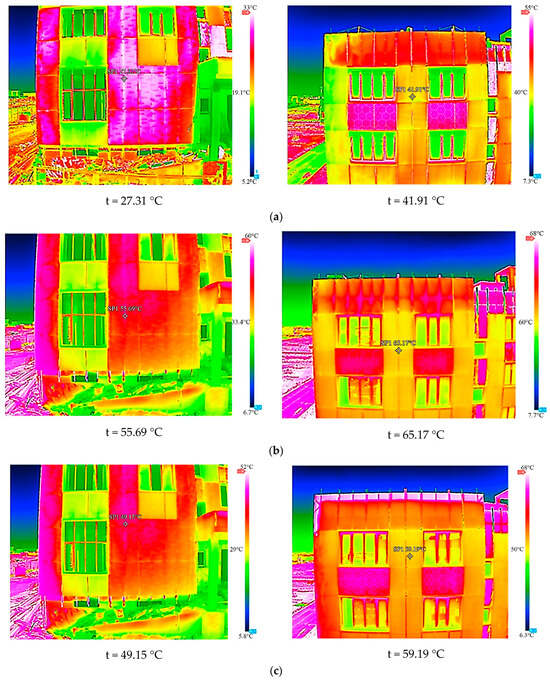

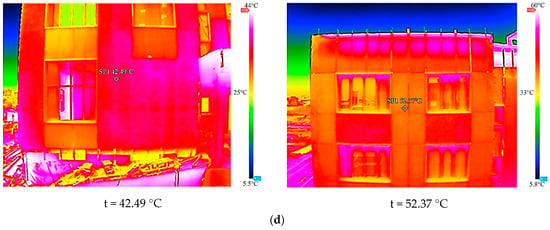

At the first stage of the survey, detailed thermal imaging of the exterior façades was carried out for both buildings. The study focused on the eastern orientation of each façade and covered all height levels—from the lower to the upper floors—allowing the identification of thermal anomalies, the assessment of temperature distribution uniformity, and the detection of potential areas of heat loss. The resulting thermograms are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Thermograms of the entire building façade: (a) 9-storey building in Turkestan; (b) 25-storey building in Shymkent.

In accordance with the methodology presented in Section 2, thermograms were recorded throughout the daylight hours. This approach made it possible to trace the dynamics of temperature field variations in the building envelope depending on the degree of solar insolation and changes in the outdoor air temperature. The main results of the thermal imaging survey for Option 1 are presented in Figure 6, which shows thermograms of the lower and upper floors corresponding to the observation times.

Figure 6.

Thermograms of the exterior façade of the 9-storey residential building in Turkestan (Option 1): (a) 7:00; (b) 10:00; (c) 13:00; (d) 17:00.

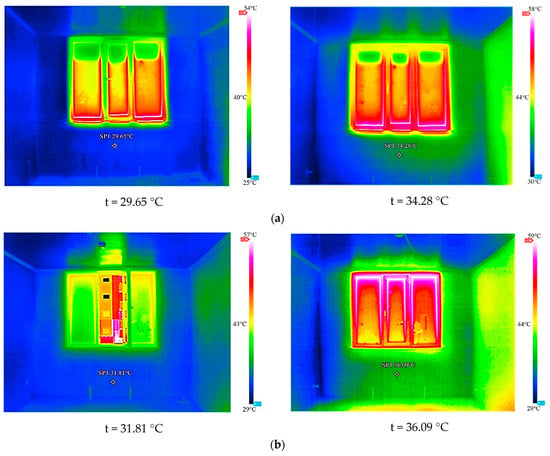

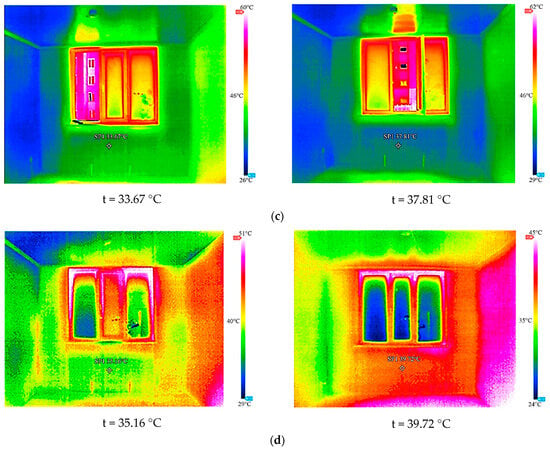

At the next stage of the survey, detailed thermal imaging of the interior surfaces of the external building envelope was carried out for both sites, covering all rooms from the lower to the upper floors. The investigation was also conducted throughout the daylight hours in accordance with the methodology described in Section 2. The main results of the thermal imaging survey of the interior surfaces for Option 1 are presented in Figure 7, where thermograms of only the lower and upper floors are shown.

Figure 7.

Thermograms of the interior surface of the external building envelope of the 9-storey residential building in Turkestan (Option 1): (a) 7:00; (b) 10:00; (c) 13:00; (d) 17:00.

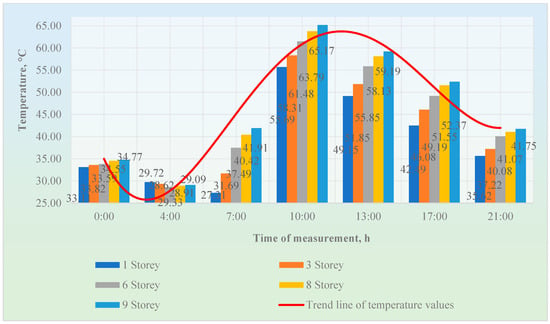

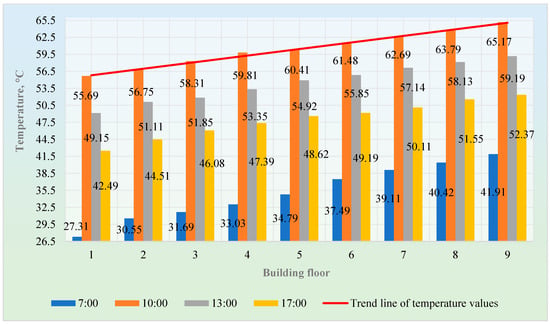

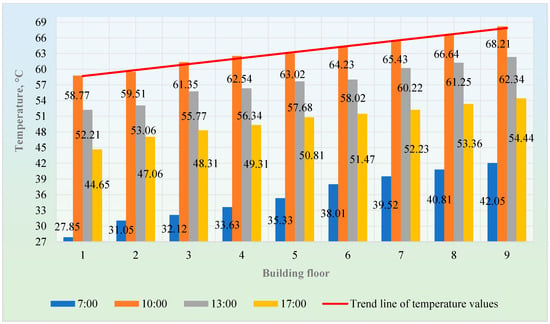

The analysis of the thermograms for Option 1, taking into account the influence of solar radiation on the cladding of the building’s external envelope and based on the data presented in Figure 6, is shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9. These figures illustrate the temperature distribution as a function of the observation time and building height, respectively. The conducted analysis makes it possible to trace the daily dynamics of façade heating and to identify areas of non-uniform temperature fields caused by the specific characteristics of solar insolation.

Figure 8.

Temperature on the exterior cladding surface of the building envelope at different floors of the 9-storey building in Turkestan as a function of time of day.

Figure 9.

Temperature on the exterior cladding surface of the building envelope at different floors and at different times of day for the 9-storey building in Turkestan.

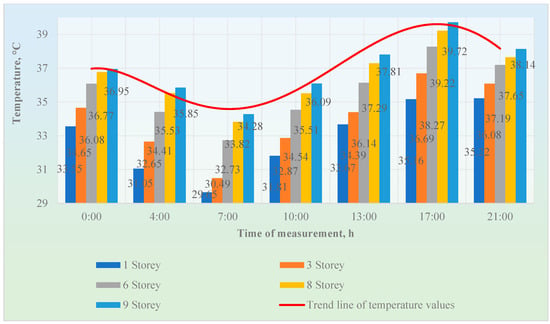

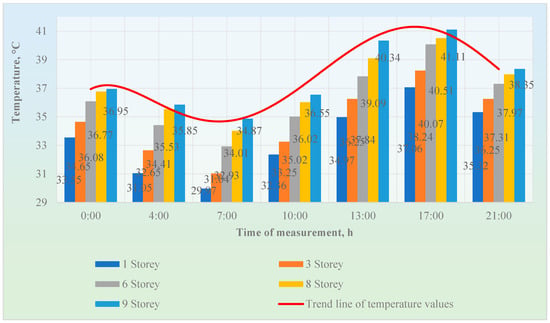

The variation in temperature values on the interior surface of the external building envelope under the influence of solar radiation, based on the thermograms shown in Figure 7, is presented in Figure 10 and Figure 11. These data make it possible to assess the degree of heat transfer through the envelope structure and to determine the impact of external heating on the thermal conditions of the indoor spaces.

Figure 10.

Temperature of the interior surface of the external building envelope at different floors of the 9-storey building in Turkestan as a function of time of day.

Figure 11.

Temperature of the interior surface of the external building envelope at different floors and at different times of day for the 9-storey building in Turkestan.

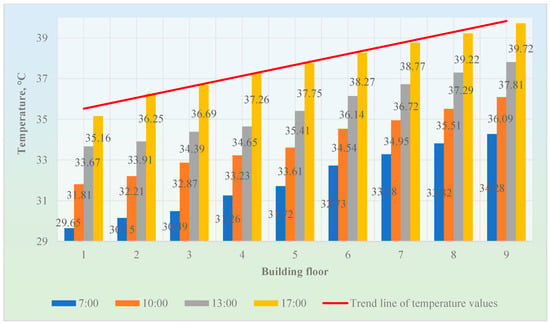

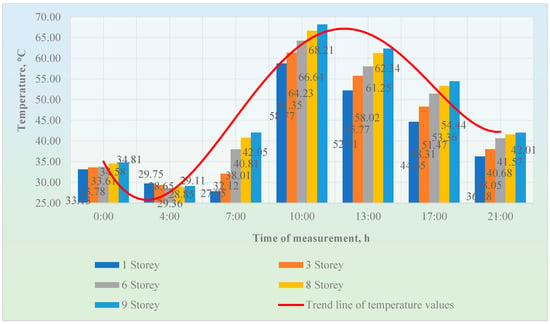

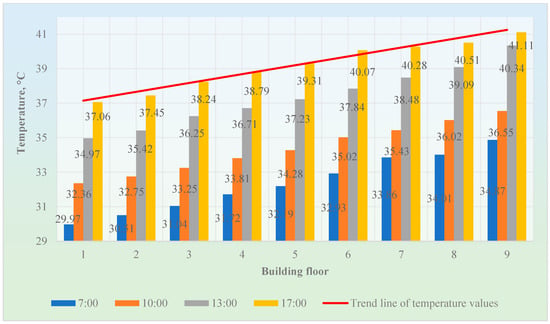

Since the survey procedure for Option 2 is identical to that of Option 1, the thermograms for this option are not presented here. Instead, an analysis of the temperature values on the envelope surfaces was carried out. The temperature variations on the exterior cladding are shown in Figure 12 and Figure 13, while the temperature variations on the interior surface of the external building envelope are presented in Figure 14 and Figure 15.

Figure 12.

Temperature on the exterior cladding surface of the building envelope at different floors of the 25-storey building in Shymkent as a function of time of day.

Figure 13.

Temperature on the exterior cladding surface of the building envelope at different floors and at different times of day for the 25-storey building in Shymkent.

Figure 14.

Temperature of the interior surface of the external building envelope at different floors of the 25-storey building in Shymkent as a function of time of day.

Figure 15.

Temperature of the interior surface of the external building envelope at different floors and at different times of day for the 25-storey building in Shymkent.

The full-scale investigations conducted on two residential buildings of different heights—a 9-storey building in Turkestan and a 25-storey building in Shymkent—made it possible to comprehensively assess the influence of solar radiation on the thermal behavior of external building envelopes with ventilated cavities. The climatic parameters during the surveys were nearly identical for both sites: high levels of solar radiation, peak daytime outdoor temperatures characteristic of the summer period, and low wind speeds recorded by automated meteorological stations (Figure 3). This ensures the comparability of the results and enables an analysis of the influence of façade geometry, building height, and ventilation cavity width on the formation of thermal processes.

Both buildings feature a multilayer external envelope structure consisting of a 200 mm aerated concrete masonry layer, a 100 mm mineral wool insulation layer, and a 10 mm exterior cladding made of composite panels. The key difference between the two variants lies in the width of the ventilated air cavity: 100 mm in the 9-storey building and 50 mm in the 25-storey building (Table 1). A desk-based assessment of the thermophysical properties of the materials indicates similar thermal conductivity values for the layers (λ of the insulation −0.035 W/(m·°C), λ of the aerated concrete −0.15 W/(m·°C)); however, the variation in the width of the air channel is expected to significantly affect the intensity of natural convection and the distribution of heat fluxes.

The observation program included comprehensive thermal imaging of the exterior façade surfaces (Figure 4), performed during key periods of the day—7:00, 10:00, 13:00, and 17:00—which made it possible to capture the full cycle of daily solar insolation. At the first stage, the dynamics of façade cladding heating were examined; at the second stage, the behavior of the interior surface of the external envelope was analyzed. Temperature measurements were recorded with high accuracy (up to ±0.1 °C), enabling the assessment of non-stationary processes and the identification of localized anomalies. The results of the thermographic observations for the 9-storey building (Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11) demonstrate a pronounced dependence of the exterior cladding temperature on the time of day: temperatures are lowest in the morning, within 32–35 °C, rise to 40–45 °C by 10:00, and reach their maximum at 13:00–48–52 °C on the upper floors. By 17:00, temperatures decrease to 38–42 °C, corresponding to the end of the period of direct solar exposure. The diurnal amplitude reaches 15–18 °C, with the upper floors consistently exhibiting temperatures 3–5 °C higher than the lower façade levels. The interior surface of the envelope also responds to external heating, but with a pronounced phase shift. As shown in Figure 10 and Figure 11, the temperature of the interior surface in the 9-storey building varies within 28–32 °C, which is 15–20 °C lower than the exterior cladding temperatures during daytime peaks. The difference between the temperatures of the upper and lower floors on the interior surface is 1.0–1.5 °C, reflecting attenuation of the height-dependent effect due to the thermal inertia of the aerated concrete masonry and insulation. Nevertheless, the trend toward higher temperatures at upper levels persists, confirming the influence of solar heating on the overall heat flux through the envelope. In contrast to the 9-storey building, the thermal processes observed in the 25-storey building exhibit a more pronounced character (Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15). The exterior cladding on the upper floors reaches 53–58 °C at 13:00, which is 5–7 °C higher than in the 9-storey case. For several floors, the amplitude of temperature fluctuations exceeds 20 °C. This difference is primarily associated with the reduced width of the ventilated air cavity −50 mm compared with 100 mm. A narrower channel increases the velocity of the upward airflow, which simultaneously intensifies heat exchange and reduces the thermal inertia of the air layer. As a result, the exterior cladding experiences more rapid heating, and temperature peaks form more quickly. The temperature of the interior surface of the external envelope in the 25-storey building ranges from 29 to 34 °C, which is 1–2 °C higher than in the 9-storey building. This increase is explained both by the more intense exterior heating and by the reduced air-gap thickness, which leads to higher convective transfer rates and weaker attenuation of the thermal wave within the cavity. The temperature difference between the lower and upper floors reaches 2.0–2.5 °C, confirming a stronger vertical thermal gradient in the high-rise building.

The height-dependent non-uniformity of façade heating identified in the full-scale observations is fully consistent with the findings of contemporary studies. As shown in the works of Martínez-Rubio A. [15] and Tao Y. [22,23], discussed in the literature review, the intensity of solar radiation increases with building height, and the upper façade zones are exposed to solar rays at steeper incidence angles. The studies by Stazi F. [16], Sánchez M. [17], and Lin Z. [24] confirm that high-rise façades generate more pronounced upward convection and may exhibit surface temperature increases of 4–10 °C compared with lower levels. The values obtained in the present study fall well within these ranges.

An analysis of existing regulatory approaches shows that the current normative framework [32,33,34,35] evaluates thermal processes primarily through the amplitude of temperature fluctuations, which is insufficient under real conditions of solar radiation exposure. The amplitude does not account for: the height-dependent non-uniformity of insolation; the phase shift in temperature; dynamic changes in convective airflow within the cavity; the accelerated heating effect in narrow ventilation channels; or evening and nighttime radiative-free cooling, during which the airflow rate in the cavity is not regulated by the standards. All these factors have a direct impact on indoor thermal comfort and building energy efficiency, and their absence from the normative calculation methodology reduces the accuracy of modeling actual heat flows.

The limitation of the work is the absence of continuous series of observations for many days and the inability to directly measure the air flow velocities in the ventilation layer, which is necessary for a more accurate determination of the aerodynamic characteristics of the system under various solar heating conditions. In addition, the study was carried out on full-scale objects with actually implemented structural solutions, and therefore full control of all geometric and structural parameters of facade systems was not ensured. In particular, within the framework of this stage of research, it is not possible to analyze buildings of the same number of storeys with different ventilation gap widths or, conversely, buildings of different number of storeys with identical air gap widths, which limits strict parametric comparison. It should also be noted that the research facilities are located in different cities, and although they belong to the same climatic zone and were surveyed under comparable meteorological conditions, no direct instrumental recording of the intensity of solar radiation on the facade surfaces was carried out on the day of the experiment. In this regard, the revealed differences are interpreted from the standpoint of the physical mechanisms of heat and mass transfer and compared with the data of previously published experimental and numerical studies. An additional limitation is that the results obtained relate to the hot season. To form a comprehensive understanding of the thermal behavior of ventilated facades during the annual cycle, it is necessary to expand the time coverage of observations, conduct multifactorial field experiments with control of solar radiation and aerodynamic parameters, as well as involve numerical modeling followed by experimental validation.

The findings of this study indicate that the influence of solar radiation on façade systems of high-rise buildings requires an integrated consideration of both thermal and aerodynamic factors. For a reliable quantitative assessment of these processes, it is recommended to continue the research in the form of a comprehensive multi-stage full-scale experiment, including the measurement of airflow velocity and structure within the ventilation cavity, analysis of the temporal cycles of heat transfer, and CFD modeling followed by validation. These data are essential for developing corrective coefficients and updating the regulatory framework for calculating the thermal stability of façades.

4. Conclusions

The conducted field studies allowed us to identify quantitative features of the influence of solar radiation on the thermal regime of external fences of high-rise buildings. For a 9-storey building, the maximum temperature of the exterior cladding was 48–52 °C, and for a 25-storey building it was 53–58 °C, while the upper floors were 3–7 °C warmer than the lower ones. The temperature of the inner surface varied in the range of 28–32 °C and 29–34 °C, respectively, reflecting the combined effect of solar exposure and heat exchange conditions in the ventilated air layer.

A comparison of the temperature conditions of the two facade systems showed that with a decrease in the width of the air gap from 100 mm to 50 mm, there are more pronounced daily temperature fluctuations, faster formation of temperature maxima and an increase in the altitude temperature gradient. These features are interpreted as a manifestation of a change in the dynamics of heat exchange and a decrease in the ability of the system to smooth out external thermal effects. It should be noted that in the framework of this work, these conclusions are based on the analysis of temperature fields and their temporal dynamics and are not accompanied by the calculation of quantitative indicators of thermal inertia, such as the Thermal Time Constant or the coefficient of attenuation of temperature fluctuations (Decrement Factor).

The results obtained are consistent with modern experimental and numerical studies indicating the nonlinear nature of thermal processes in ventilated facades and increased temperature heterogeneity in the upper zones of high-rise buildings under the influence of solar radiation. At the same time, they emphasize the need for a more rigorous quantitative analysis of thermal dynamics in order to correctly assess the inertial properties of facade systems.

The practical significance of the work lies in the possibility of using the revealed patterns of temperature behavior of facades when pre-selecting the width of the ventilation gap, the type of cladding and natural ventilation modes for buildings operated in conditions of high insolation. The results can be useful in assessing the thermal comfort of rooms and forming recommendations for the design of energy-efficient facade systems, taking into account the high-altitude unevenness of solar heating.

Taking into account the identified limitations, it is advisable to conduct further comprehensive studies, including extended multi-day series of field observations, direct aerodynamic measurements in the ventilation gap, calculation of thermal inertia (Thermal Time Constant, Decrement Factor), as well as numerical modeling of heat and mass transfer followed by experimental validation. This will improve the accuracy of thermal engineering calculations and the validity of design solutions for facade systems of high-rise buildings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.Z. and A.Z.; Methodology, N.Z. and A.Z.; Investigation, N.Z., A.U. and T.T.; Data curation, T.T. and S.B.; Writing—original draft preparation, N.Z., A.Z. and A.U.; Writing—review and editing, N.Z., A.Z., S.B. and R.Z.; Supervision, N.Z., R.Z. and A.Z. Project administration, N.Z.; Funding acquisition, N.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP23486892).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

References

- Kočí, V.; Bažantová, Z.; Černý, R. Computational analysis of thermal performance of a passive family house built of hollow clay bricks. Energy Build. 2014, 76, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Lu, J.; Wu, J.; Luo, X.; Shen, F. Suitable and energy-saving retrofit technology research in traditional wooden houses in Jiangnan, South China. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 45, 103550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhangabay, N.; Kudabayev, R.A.; Mizamov, N.; Imanaliyev, K.; Kolesnikov, A.; Moldagaliyev, A.; Merekeyeva, A. Study of the model of the phase transition envelope taking into account the process of thermal storage under natural draft and by air injection. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e02050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomponi, P.; Piroozfar, P.; Southall, R.; Ashton, P.; Farr, E. Energy performance of Double-Skin Façades in temperate climates: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 1525–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- María Ibañez-Puy, M.; Vidaurre-Arbizu, M.; Sacristán-Fernández, H.; Martín-Gómez, C. Opaque Ventilated Façades: Thermal and energy performance review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wei, A.; Zou, S.; Dong, Q.; Qi, J.; Song, Y.; Shi, L. Controlling naturally ventilated double-skin façade to reduce energy consumption in buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 202, 114649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhangabay, N.; Tagybayev, A.; Baidilla, I.; Sapargaliyeva, B.; Shakeshev, B.; Baibolov, L.; Duissenbekov, B.; Utelbayeva, A.; Kolesnikov, A.; Izbassar, A.; et al. Multilayer External Enclosing Wall Structures with Air Gaps or Channels. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleinik, P.P.; Korchagina; Yu, G. Modern technological solutions in façade design. Eng. Bull. Don 2020, 2, 1–9. Available online: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/sovremennye-tehnologicheskie-resheniya-v-dizayne-fasadov (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Kurbanaliyev, M.; Ragimov, S.H.; Kurbanaliyev, M. Influence of climatic conditions on façade design. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2020, 4, 118–122. Available online: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/vliyanie-klimaticheskih-usloviy-na-proektirovanie-fasadov (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Zhangabay, N.; Giyasov, A.; Bakhbergen, S.; Tursunkululy, T.; Kolesnikov, A. Thermovision study of a residential building under climatic conditions of South Kazakhstan in a cold period. Constr. Mater. Prod. 2024, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhangabay, N.; Giyasov, A.; Ibraimova, U.; Tursunkululy, T.; Kolesnikov, A. Construction and climatic certification of an area as a prerequisite for development of energy-efficient buildings and their external wall constructions. Constr. Mater. Prod. 2024, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, S.; Ip, K. Perspectives of double skin façades for naturally ventilated buildings: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 40, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhangabay, N.; Tursunkululy, T.; Ibraimova, U.; Abdikerova, U. Energy-Efficient Adaptive Dynamic Building Facades: A Review of Their Energy Efficiency and Operating Loads. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhangabay, N.; Zhangabay, A.; Utelbayeva, A.; Tursunkululy, T.; Sultanov, M.; Kolesnikov, A. Energy-Efficient Outdoor Fencing with Air Layers: A Review of the Effect of Solar Radiation on the Exterior Fencing of Buildings Made of Composite Material. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Rubio, A.; Sanz-Adan, F.; Santamaría-Peña, J.; Martínez, A. Evaluating solar irradiance over facades in high building cities, based on LiDAR technology. Appl. Energy 2016, 183, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stazi, F.; Vegliò, A.; Di Perna, C. Experimental assessment of a zinc-titanium ventilated facade in a Mediterranean climate. Energy Build. 2014, 69, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.N.; Sanjuan, C.; Suárez, M.J.; Heras, M.R. Experimental assessment of the performance of open joint ventilated facades with buoyancy-driven airflow. Sol. Energy 2013, 91, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinosci, C.; Semprini, G.; Morini, G.L. Experimental analysis of the summer thermal performances of a naturally ventilated rainscreen facade building. Energy Build. 2014, 72, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampi, M.; Leccese, F.; Tuoni, G. Ventilated facades energy performance in summer cooling of buildings. Sol. Energy 2003, 75, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjuan, C.; Sua´rez, M.; Gonza´lez, M.; Pistono, J.; Blanco, E. Energy performance of an open-joint ventilated facade compared with a conventional sealed cavity façade. Sol. Energy 2011, 85, 1851–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqaed, S. Effect of annual solar radiation on simple façade, double-skin facade and double-skin facade filled with phase change materials for saving energy. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 51, 101928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Yan, Y.; Fang, X.; Zhang, H.; Tu, J.; Shi, L. Solar-assisted naturally ventilated double skin façade for buildings: Room impacts and indoor air quality. Build. Environ. 2022, 216, 109002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Huang, H.; Fang, X.; Yan, Y.; Tu, J.; Shi, L. Solar radiation on naturally ventilated double skin facade in real climates: The impact of solar incidence angle. Renew. Energy 2024, 232, 121124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.H.; Song, Y.; Chu, Y. An experimental study of the summer and winter thermal performance of an opaque ventilated facade in cold zone of China. Build. Environ. 2022, 218, 109108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cai, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, F.; Yu, H.; Liu, J.; Miao, J.; Li, G.; Chen, T.; Feng, L.; et al. Performance study of ventilated energy-productive wall: Experimental and numerical analysis. Sol. Energy 2024, 273, 112512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantucci, S.; Serra, V.; Carbonaro, C. An experimental sensitivity analysis on the summer thermal performance of an Opaque Ventilated Façade. Energy Build. 2020, 225, 110354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Masi, R.F.; Festa, V.; Ruggiero, S.; Vanoli, G.P. Environmentally friendly opaque ventilated façade for wall retrofit: One year of in-field analysis in Mediterranean climate. Sol. Energy 2021, 228, 495–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Masi, R.F.; Festa, V.; Gigante, A.; Ruggiero, S.; Peter, G. Experimental analysis of grills configuration for an open joint ventilated facade in summertime. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 54, 104608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto Francés, V.M.; Sarabia Escriva, E.J.; Pinazo Ojer, J.M.; Bannier, E.; Soler, V.C.; Moreno, G.S. Modeling of ventilated facades for energy building simulation software. Energy Build. 2013, 65, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Code of Rules of the Republic of Kazakhstan 2.04-01-2017. Building Climatology: State Standards in the Field of Architecture, Urban Planning and Construction. Code of Rules of the Republic of Kazakhstan.—JSC “KazNIISA”, LLP “Astana Stroy-Consulting”. 2017. Approved and Enacted on 20 December 2017. 43p. Available online: https://gos24.kz/uploads/documents/2022-12/sp-rk-2.04-01-2017-stroitelnaya-klimatologiya.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Available online: https://kazhydromet.kz (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Code of Rules of the Republic of Kazakhstan 2.04-107-2022. Building Heat Engineering: State Standards in the Field of Architecture, Urban Planning and Construction. Code of Rules of the Republic of Kazakhstan.—JSC “KazNIISA”, LLP “Astana Stroy-Consulting”. 2013. Approved and Enacted on 1 July 2015. p. 80. Available online: https://online.zakon.kz/Document/?doc_id=39838250 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Code of Rules of the Republic of Kazakhstan 2.04-106-2012. Designing of thermal protection of buildings: State Standards in the Field of Architecture, Urban Planning and Construction. Code of Rules of the Republic of Kazakhstan. JSC “KazNIISA”, LLP “Astana Stroy-Consulting”. 2013. Approved and Enacted on 1 July 2015. p. 153. Available online: https://online.zakon.kz/Document/?doc_id=35957424 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- EN ISO 6946; Building Components and Building Elements. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: https://www.en-standard.eu/iso-6946-2017-building-components-and-building-elements-thermal-resistance-and-thermal-transmittance-calculation-methods/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- SP 50.13330.2024; Thermal Protection of Buildings. Russian Institute for Standardization: Moscow, Russia, 2024; p. 74. Available online: https://rsoserv.ru/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/SP-50.13330.2024-Svod-Pravil.-Teplovaya-zashhita-zdanij.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.