Abstract

This study maps the maturity of construction safety culture in Indonesia across the design and construction phases and identifies priorities for improving the safety management system in construction. Building on a literature-derived framework of categories and subcategories, we conducted a two-round questionnaire-based expert elicitation (pilot and final rounds) and focus group discussions (FGDs) with a purposive panel of 12 experts representing key stakeholders (government/owners, contractors, consultants, and academia). Expert validation was used to assess alignment with field conditions and refine recommendations. The results show average maturity scores of 3.11 in the design phase and 3.36 in the construction phase, indicating a position between the compliant and proactive levels. Sub-category analysis indicates comparatively stronger performance in regulatory mechanisms and operational controls but persistent weaknesses in early-stage planning competence, time and resource allocation for safety, digitalization of safety management, and hazardous waste management. A cross-phase gap is evident: safety is more institutionalized during execution than it is embedded in upstream design decisions. The findings suggest that advancing beyond compliance requires an integrated approach that links national regulations with international project management guidance and construction-specific practices. We conclude by outlining how these frameworks’ integration can support a transition toward more proactive and ultimately resilient safety culture maturity in Indonesia’s construction sector.

1. Introduction

The construction industry remains one of the most hazardous sectors, where accidents often result in fatalities, material losses, and environmental harm [1,2]. Project planning and execution under constrained time and budget are among the characteristics that distinguish construction projects from those in other industries. These conditions contribute to hazardous environments and increase the risk of occupational accidents [3]. In addition, the development of a safety culture remains a major challenge within this industry, with most firms in Indonesia exhibiting only a reactive stage of safety culture maturity [4].

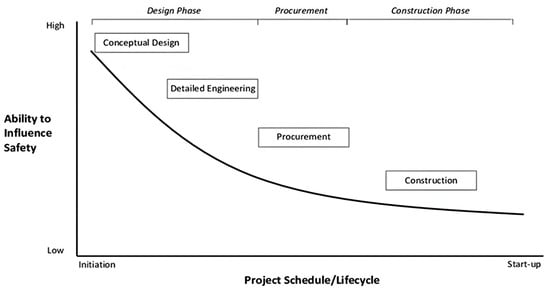

On the other hand, the implementation of various safety regulations in Indonesia remains fragmented, with partial distribution across sectoral authorities. As a result, Law No. 1/1970 and Government Regulation No. 50/2012 reinforce the perception that contractors solely take responsibility for safety in the construction industry [5]. Contrary to this contractor-centric perception, the responsibility for construction safety is collective—encompassing project owners, design and supervision consultants, contractors, and the wider supply chain [6]. Under Law No. 2 of 2017, construction actors including owners, consultants, and contractors, are mandated to apply standards of safety, security, health, and sustainability. Such standards include those related to materials, equipment, procedures, occupational health and safety, and environmental protection. The study by Endroyo et al. (2017) also revealed that the maturity of safety planning in the pre-construction stage is strongly correlated with safety resilience in the construction phase [7]. Projects marked by accidents involving casualties, property destruction, and environmental damage tend to reflect low levels of maturity in safety planning. Symbersky’s time–safety influence curve [8] further illustrates that the ability to influence safety is highest during conceptual and detailed design and declines sharply toward the construction phase (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Symbersky Theory.

Machfudiyanto et al. conceptualized construction safety as the condition in which potential hazards are controlled throughout the life cycle of a facility during execution, operation, maintenance, and partial or total demolition to prevent worker injuries, public harm, property damage, and environmental impacts [4]. This life-cycle view implies that safety culture must be mature not only in planning, but also during project execution, where the most acute risks materialize. Empirical studies in Indonesia show that, despite the existence of formal safety arrangements, on-site performance often deteriorates when workers have a low sense of control over their working conditions and face strong production pressures, revealing a gap between stated commitments and everyday practice during the construction phase [9,10]. Similar patterns are reported in other developing contexts, where construction organizations frequently operate at low safety culture maturity levels, safety is not treated as a core business risk, and written policies are weakly translated into routine site behaviors [11,12]. At the same time, international evidence confirms that poor safety management during execution directly leads to accidents, project delays, and financial losses, reinforcing the execution phase as a critical arena for safety culture performance [13]. Advancing beyond this reactive state requires robust institutional frameworks and coherent public policy that explicitly support safety management across the construction value chain [4]. Building on a structure–conduct–performance logic, Machfudiyanto et al. (2022) further argued that project organizational structures, behavioral dynamics, and performance incentives jointly shape safety management systems, and in turn, determine the maturity of safety culture and the level of safety performance achieved [2,14].

Ideally, a construction safety culture emerges from the aligned contributions of project owners, design consultants, supervising consultants, contractors, and the wider supply chain. However, whether the safety values, priorities, and practices of these actors are sufficiently integrated to support consistently high levels of safety performance across project phases is a central challenge. In Indonesia, the Construction Safety Management System (Sistem Manajemen Keselamatan Konstruksi, SMKK) mandated through Ministry of Public Works and Public Housing Regulation No. 10/2021 (Permen PUPR No. 10/2021) provides a technical framework for implementing safety, health, and sustainability standards. Yet, despite these regulatory developments, there is still no systematic evidence of the maturity of the safety culture in Indonesian building projects, nor of where the most critical gaps occur along the design–construction continuum. Without a phase-specific diagnosis of safety culture maturity, project owners, consultants, contractors, and regulators have limited guidance on where to prioritize their efforts, how to allocate resources, and how to monitor progress under the SMKK framework. This study seeks to provide an empirical baseline that can be used to target improvement actions, reinforce areas of relative strength, and ultimately contribute to reducing the persistently high burden of construction accidents in Indonesia by quantifying safety culture maturity separately for the design and construction phases and across key stakeholder groups.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Safety Culture in Construction

Safety culture is defined as the set of values, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors that shape organizational practices to safeguard workers, control risks, and minimize workplace accidents [15]. Hudson’s emphasized that it is manifested in an organization’s obligation to prevent incidents and its ability to anticipate hazards and implement preventive actions [16]. A positive safety culture is characterized by visible management commitment, transparent and effective communication, active worker engagement in safety initiatives, and continuous learning from experiences [3,17]. The construction sector requires a robust safety culture due to the elevated risk of accidents, such as those arising from working at height, using heavy equipment, or managing hazardous substances. A mature safety culture ensures that safety transcends administrative compliance and becomes a collective value upheld by every project participant.

2.2. Safety Culture Maturity Models

Hudson’s [18] Safety Culture Maturity Model enables the assessment of safety culture within construction projects by defining five maturity stages. Each stage illustrates the organization’s level of development in embedding safety within its operations, while also serving as a diagnostic tool for identifying gaps and opportunities to strengthen safety culture. These five stages of maturity level are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Maturity Level Scale [18].

The safety maturity model has been analyzed by construction safety (K2) practitioners. The model, adapted from the UK Coal Journey framework, categorizes the maturity of safety culture implementation into five stages: Basic, Reactive, Compliant (Planned), Proactive, and Resilient [19]. Pashya identified eight critical factors in developing a total construction safety culture: (a) leadership, (b) competence, (c) commitment, (d) policy, (e) project scope, (f) resources, (g) supervision, and (h) training. Further data analysis revealed that the key determinants are (i) leadership, (ii) supervision, and (iii) training [20].

Several peer-reviewed studies have applied Hudson’s safety culture maturity model (or similar frameworks) to the construction industry. These studies typically assess organizations on a five-level maturity ladder (e.g., from pathological to generative culture) and adapt it to local contexts. For example, Golabchi et al. (2025) proposed a safety maturity framework in Canada that integrates leading indicators to encourage proactive safety management, extending Hudson’s model toward prevention-oriented practices [21]. Chan (2023) applied the five-stage maturity framework to Hong Kong building projects, revealing gaps in maturity levels across clients, contractors, and subcontractors, and emphasizing the challenge of aligning safety culture across fragmented project stakeholders [22]. Trinh and Feng (2022), working in the Vietnamese construction context, enriched the maturity model by incorporating resilience dimensions such as anticipation, learning, and error management [23]. While these studies demonstrate the adaptability of Hudson’s framework, they generally treat safety culture as a unified organizational or project-level construct, with limited attention to how maturity may vary across the project lifecycle. In contrast, this study localizes the maturity framework to Indonesia’s construction sector and uniquely applies it in a phase-based assessment that distinguishes between the design and construction phases. This approach not only provides an empirical baseline of maturity for each phase but also identifies systematic gaps between them, thereby offering practical insight for targeted improvement under Indonesia’s evolving regulatory context (e.g., SMKK implementation).

In this study, we build on Hudson’s established five-level logic (from reactive to generative/proactive) and adapt it to the specific needs of construction projects by structuring the assessment around the two main project phases. Therefore, the proposed “phase-based safety culture maturity assessment” uses existing maturity levels but applies them separately to the design and construction phases and to a detailed set of safety-related subcategories. This disaggregated view enables the identification of phase-specific weaknesses that would remain hidden in a single, organization-wide maturity score.

2.3. Standards and Frameworks

Construction safety culture maturity cannot be separated from the regulatory and managerial frameworks that guide project implementation. In Indonesia, the SMKK, mandated under Law No. 2/2017 and further detailed in Permen PUPR No. 10/2021, provides the legal foundation for integrating safety management into all construction activities, although its implementation remains largely compliance-oriented [2]. At the international level, ISO 21500 offers general project management guidance, emphasizing the alignment of organizational objectives with project execution, including risk and safety considerations [24]. The PMBOK Construction Extension expands on the Project Management Institute’s framework by incorporating construction-specific practices such as safety planning, quality integration, and stakeholder coordination [25].

Together, these three frameworks form a critical reference for advancing safety culture maturity, as they provide complementary perspectives: SMKK ensures regulatory compliance, ISO 21500 emphasizes project governance and standardization, and the PMBOK Construction Extension integrates safety into practical project delivery. Integrating these standards offers a pathway to move beyond compliance-driven safety management toward a more proactive and resilient safety culture within Indonesia’s construction industry.

3. Methodology

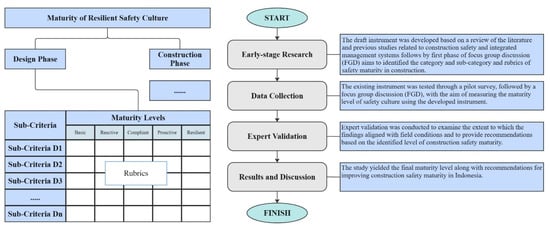

The resilient safety culture maturity framework is structured around measurable components, such as criteria, sub-criteria, maturity levels, and rubrics, based on established maturity models [23]. Maturity models operate by delineating stages or levels that gauge organizational or process completeness across various multidimensional indicators [26]. Accordingly, this study operationalizes safety culture maturity as a phase-based matrix. Rather than assigning a single maturity level to each organization, the framework assesses each sub-category’s maturity within the design and construction phases. The maturity level descriptors are derived from existing maturity models, particularly Hudson’s five-level approach, and are localized and contextualized for the Indonesian construction sector, then applied separately to each phase–sub-category combination. This design allows us to pinpoint the weakest phase of safety culture maturity at the sector level. In this study, the maturity framework should be interpreted as a structured conceptual and policy analysis tool based on expert judgment; it has not yet undergone large-sample psychometric testing (e.g., reliability and construct validity) and therefore should not be treated as a validated measurement scale. Future applications of the framework with larger, stratified samples could further examine how gaps differ among owners, contractors, and consultants. The structure of the maturity model and the research methodology is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Structure of the Maturity Model and the Research Flow.

The research was conducted in three stages. First, a literature review and initial FGDs were used to identify and refine categories and sub-categories relevant to safety culture maturity in Indonesia’s construction sector and to develop phase-based maturity rubrics. Second, data were collected through a structured questionnaire that operationalized these rubrics, complemented by follow-up FGDs. For each sub-category, experts selected the maturity level that best represents typical practice in Indonesian building projects (Basic/Pathological, Reactive, Compliant/Planned, Proactive, or Resilient).

Sampling was purposive and expert-based rather than statistically representative. The panel consisted of 12 experts selected to cover key stakeholder groups in Indonesian construction, including government/owners or regulators, state-owned and private contractors, consultants, and academia. Inclusion criteria were (i) at least 10 years of experience in medium- to large-scale construction projects; (ii) a senior role with responsibility for safety management, project delivery, or regulatory oversight; and (iii) familiarity with national safety regulations and internal safety management systems. The questionnaire was piloted with a subset of the panel to refine wording and ensure clarity (see Appendix A for the pilot instrument), then administered to the full panel, who completed it individually (see Appendix B for the final questionnaire) before participating in FGDs. The FGDs were used to discuss ratings, resolve major discrepancies where needed, and capture qualitative explanations of phase-specific maturity profiles. Participating state-owned contractors represented approximately 80% of the national state-owned construction sector, providing coverage of organizations involved in a substantial share of major projects.

Third, the consolidated findings were subjected to expert validation, in which the panel and additional senior academics reviewed the results for alignment with field conditions and refined the policy and practical recommendations.

4. Result

4.1. Categories and Sub-Categories

The initial stage of this research involved a systematic literature review followed by a focus group discussion to identify the critical dimensions of safety culture maturity within construction projects. Previous studies on safety management maturity [18,23,27,28] have highlighted that safety culture is a multidimensional construct that evolves through organizational learning, regulatory compliance, and stakeholder engagement. Building upon these insights, the review was extended to include Indonesian national and international standards, such as SMKK, ISO 21500 (Guidance on Project Management), and PMBOK Construction Extension, which emphasize the integration of safety into both the design and the execution phases of construction projects.

Structured set of categories and subcategories was developed to assess safety culture maturity. These dimensions were grouped into two major phases: (i) the Design Phase, where safety is embedded in planning and decision-making, and (ii) the Construction Phase, where safety management is operationalized in the field. Following the development of the category–sub-category framework for the design and construction phases, we engaged a purposive panel of experts to pilot the instrument, join the FGDs, and provide independent validation of the findings, as shown in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 2.

Categories, Sub-Categories, and Safety Culture Maturity Descriptions in the Design Phase.

Table 3.

Categories, Sub-Categories, and Safety Culture Maturity in the Construction Phase.

In the Design Phase (Table 2), seven categories were identified: Competence and Personnel of Designers (knowledge, skills, attitudes, and commitment to safety), Regulatory Environment (laws, codes, and professional accountability mechanisms), Tools and Resources (availability of technologies and training systems), Design for Safety Methods (risk management, integration of safety and quality, environmental considerations, and audit mechanisms), Contracts and Costs (allocation of responsibilities, time, budget, and safety-competent personnel), Influence of Owners/Clients (commitment and leadership), and Stakeholder Involvement and Collaboration (collaboration and communication mechanisms).

In the construction phase (Table 3), five categories were outlined: safety compliance and standards (compliance with K4 and inspection mechanisms), organizational governance and commitment (contractual arrangements, accountability, leadership, and incentive mechanisms), safety information management (planning, reporting, data utilization, audits, and accident investigation), operational safety management (document control, equipment and material management, worksite conditions, and waste management), and safety capacity building and innovation (digitalization of safety management and structured training programs).

Focus group discussions were conducted to further validate the subcategories within the design and construction phases. This process led to the identification of additional subcategories, namely, (D4’) Regulatory Requirements for Professional Engineer Accountability, (D9’) Evaluation and Audit Methods, (D11’) Time Considerations, (D11’’) Competent Construction Safety Personnel, (K5’) Reward and Punishment, and (K14’) Hazardous and Non-Hazardous Waste Management.

Together, these categories and subcategories represent a comprehensive maturity framework that integrates safety’s technical and organizational dimensions. They provide a systematic lens through which safety maturity can be measured across project phases while also serving as a reference point for identifying gaps between current practices and international standards.

4.2. Safety Culture Maturity Assessment

Following the pilot survey and first FGD, maturity levels for each sub-category were measured for both the design and construction phases in the next FGD phase. A panel of 12 domain experts was purposively chosen in this phase. The panel covered the principal actor groups in Indonesian projects: six from state-owned and large contractors, three from government/owner organizations, two from design consultancies, and one from academia. The cohort comprised experts occupying senior safety and project leadership roles; 6 reported >25 years of experience, 2 had 20–25 years, 2 had 15–20 years, and 2 had 10–15 years of experience. Educational attainment included 8 master’s, 2 doctoral, and 2 bachelor’s degrees. Further details can be found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Respondents Details.

This composition ensured that the instrument and subsequent interpretations were grounded in field realities across both phases, and it underpins the maturity results presented in Table 5 and Table 6 below.

Table 5.

FGD Results Analysis for Design Phase.

Table 6.

Analysis of FGD Results for the Construction Phase.

The FGD results provide a nuanced picture of how experts perceive safety culture maturity across both phases. In the design phase (Table 5), most subcategories are concentrated between the compliant and proactive levels, with very few judgment at the basic or resilient ends of the spectrum. Regulatory aspects are seen as comparatively stronger: Regulations (D3) and Regulatory Requirements for Professional Engineer Accountability (D4’) each have two-thirds or more of experts placing them at proactive or higher (66.7% and 50.0% including the resilient share, respectively), indicating that formal frameworks are perceived as reasonably mature. Similarly, Environmental Management Planning (D9) and Guidelines and Codes of Practice (D4) show a strong tilt towards compliant and proactive assessments. In contrast, more structural and capability-related dimensions such as Knowledge, Experience, and Skills of Planners (D1), Contractual and Liability (D10), and Time Considerations (D11’) display substantial shares in the basic and reactive levels (up to 25.0% in some cases), signaling persistent difficulties in embedding safety expertise, contractual leverage, and dedicated planning time within design teams. Client-side dimensions (D12–D15) are generally perceived as compliant to proactive but, with non-trivial reactive shares, suggesting that owner commitment, leadership, collaboration, and communication are present but not consistently generative across projects.

The distribution shifts upward in the construction phase (Table 6), with experts more frequently classifying subcategories as compliant, proactive, or even resilient. Operational and monitoring functions are particularly strong: Safety Audits (K9) combines 50.0% proactive and 25.0% resilient assessments, while Accident Investigation (K10) and Document Control (K11) also show dominant proactive ratings (58.3% and 50.0%, respectively). Safety Reporting (K7) stands out with one-third of experts (33.3%) placing it at the resilient level, indicating that reporting mechanisms on many projects are relatively advanced. Leadership-oriented variables—Leadership and Commitment (K5) and Training (K16)—cluster around compliant to proactive, pointing to generally positive but still uneven stakeholder engagement in safety during execution. Conversely, Reward and Punishment Mechanisms (K5’), Hazardous and Non-Hazardous Waste Management (K14’), and Safety Digitalization (K15) retain higher shares in the reactive or low compliant bands, highlighting that behavioral incentives, environmental waste control, and technology adoption lag behind more traditional operational controls. Overall, the FGD confirms that while construction-phase practices are perceived to be more mature than design-phase practices, both phases still exhibit clear gaps in the strategic, behavioral, and innovation-related dimensions of safety culture.

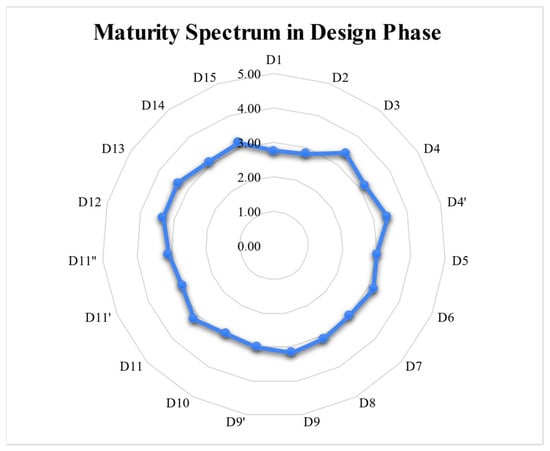

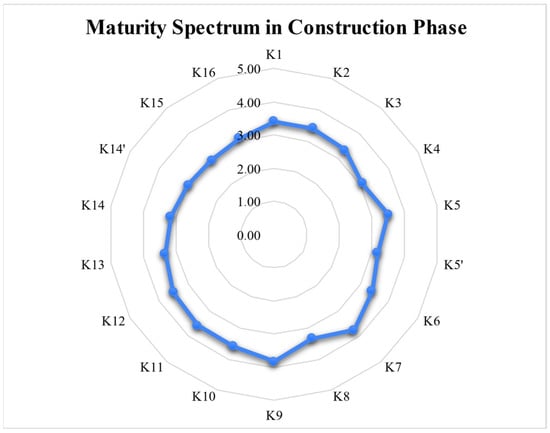

To move from qualitative expert judgments to numerical maturity scores, each expert’s allocation of a sub-category to one of the five maturity levels (Basic/Pathological, Reactive, Compliant/Planned, Proactive, Resilient) was coded from 1 to 5, respectively. For each sub-category in Table 2 and Table 3, we first calculated the mean score across the 12 experts. The phase-based averages of 3.11 (design) and 3.36 (construction) were then obtained by taking the arithmetic mean of all sub-category scores within each phase. Table 7 and Table 8 report the resulting sub-category-level scores, while the radar charts in Figure 3 and Figure 4 visualize the same data to highlight relative strengths and weaknesses within and across phases.

Table 7.

Value of Safety Culture Maturity in the Design Phase.

Table 8.

Value of Safety Culture Maturity in the Construction Phase.

Figure 3.

Maturity Spectrum in the Design Phase.

Figure 4.

Maturity Spectrum in the Construction Phase.

In the Design Phase, the average maturity score across all subcategories was 3.11, as shown in the radar chart below (Figure 3). The radar charts are used to pinpoint which criteria exhibit the lowest and highest maturity levels in each phase, thereby indicating where targeted interventions are most needed to improve overall safety culture maturity in both the design and construction phases. The radar chart in Figure 3 indicates that safety culture maturity is positioned between the compliant and proactive levels for the design phase.

Several subcategories, such as Regulations (3.42) and Regulatory Requirements for Professional Engineer Accountability (3.42), achieved relatively higher scores, suggesting that regulatory frameworks are sufficiently established. In contrast, aspects such as Knowledge and Skills of Planners (2.75) and Time Considerations (2.92) received lower scores, highlighting the challenges in embedding safety knowledge within planning teams and allocating sufficient time for safety integration.

In the construction phase, the overall maturity level was slightly higher (Figure 4), with an average score of 3.36. This reflects a stronger emphasis on operational safety practices compared with the design phase.

Sub-categories with the highest maturity in the construction phase include Safety Audits (3.83), Safety Reporting (3.75), and Accident Investigation (3.58), indicating that monitoring, auditing, and reporting mechanisms are relatively more developed. Leadership also received a strong rating (3.50), reflecting positive stakeholder engagement in safety prioritization. However, subcategories such as Safety Digitalization (2.92) and Hazardous Waste Management (3.00) scored lower, suggesting that technological adoption and environmental safety management remain underdeveloped compared with international best practices.

The construction phase generally demonstrates higher maturity values than the design phase, particularly in operational aspects such as auditing, reporting, and accident investigation. Nonetheless, both phases remain clustered around the compliant level, indicating that Indonesia’s construction sector has not yet progressed to proactive or resilient maturity. The results point to a systemic gap in safety culture maturity: while formal regulations and operational monitoring mechanisms are relatively established, early-stage planning, time allocation for safety, workforce competence, and the integration of digital innovations remain weak. This pattern was reinforced during the FGD, where experts observed that compliance-driven practices dominated, with only limited evidence of proactive or generative safety culture emerging on projects. The maturity assessment was subsequently used as a basis to formulate a set of targeted, multi-stakeholder action plans aimed at lifting the maturity level of the most critical subcategories in both the design and construction phases.

The maturity assessment results were subsequently translated into a set of targeted action plans to guide stakeholders in improving the lowest-performing subcategories. For each sub-category with scores below the “managed” level (e.g., D1–Knowledge, Experience, and Skills of Planners; D2–Attitudes and Mindsets of Planners; D10–Contractual and Liability; D11’–Time Considerations; K15–Safety Digitalization), the expert panel first identified the underlying institutional and project-level causes of immaturity, drawing on their experience and on the quantitative maturity profiles. These preliminary diagnoses were then cross-checked through a desk study of project documents from multiple building projects, which confirmed recurring gaps such as limited integration of safety into design deliverables, weak contractual leverage for safety, insufficient dedicated time for safety planning, and fragmented or non-existent digital safety data systems. On this basis, the experts co-formulated concrete improvement actions for each sub-category, specifying not only the required change, but also measurable outcome indicators and clearly assigned responsible parties. The resulting action plan (Table 9) operationalizes the maturity assessment by linking diagnosed weaknesses to multi-stakeholder interventions and monitoring metrics that can be used to track progress over time and systematically elevate safety culture maturity across both the design and construction phases.

Table 9.

Action Plan for the Improvement of the Safety Culture Maturity Level.

5. Discussions

The results indicate an intermediate maturity level (between compliant and proactive), with the design phase lagging behind the construction phase. This confirms that safety practices are institutionalized to a certain extent, particularly in the construction phase, but remain largely compliance-driven rather than rooted in proactive organizational learning. Higher scores in the construction phase reflects stronger operational mechanisms, such as reporting, auditing, and accident investigation, whereas lower score in the design phase underscores persistent limitations in embedding safety knowledge, allocating adequate planning time, and fostering professional accountability [7].

Several strengths are evident. The presence of formal regulatory frameworks and mechanisms of accountability in the design stage align with national requirements such as Law No. 2/2017 and Permen PUPR No. 10/2021, which provide legal bases for construction safety management. The relatively high auditing and reporting scores in the construction phase indicate that Indonesian projects have begun to adopt systematic monitoring processes consistent with international safety management principles [38]. These developments are consistent with earlier findings that the formalization of safety processes is often the first critical step toward building a stronger safety culture [27].

At the same time, the study highlights notable weaknesses. Regardless of higher maturity scores in some design phase subcategories, such as Regulations and Regulatory Requirements for Professional Engineer Accountability (both 3.42), subcategories such as Knowledge and Skills of Planners (2.75) and Time Considerations (2.92) remain low. This asymmetry points to a safety culture in which design teams recognize the formal importance of safety but still tend to treat it as a compliance requirement or as the contractor’s responsibility, rather than as an integral design criterion. Limited exposure to construction safety in professional education, the absence of dedicated safety roles within design organizations, and fee structures that constrain the time available for safety integration all contribute to the tendency to prioritize technical deliverables and schedule over systematic design-for-safety reviews. This result also suggests that safety is still treated as secondary to cost and time efficiency [2].

By contrast, the construction-phase profile reflects a more operationally focused and compliance-driven safety culture. Sub-categories such as Safety Audits (3.83), Safety Reporting (3.75), Accident Investigation (3.58), and Leadership (3.50) achieve relatively high maturity, suggesting that regulatory enforcement and client requirements have strengthened on-site monitoring, incident documentation, and managerial attention to safety. However, Safety Digitalization (2.92) and Hazardous Waste Management (3.00) lag behind, indicating insufficient adoption of innovations such as BIM, IoT, and digital dashboards that are increasingly integrated into safety management in more advanced contexts [32,41]. This aligns with critiques that Indonesia’s construction safety management remains predominantly reactive, with limited systemic adoption of proactive and resilient practices [42]. The lower maturity of design phase subcategories related to planner competence and time allocation, compared with the relatively higher maturity of construction-phase auditing and reporting practices, thus reflect deeper institutional patterns. Responsibility for safety is still largely institutionalized around the construction site and the contractor’s obligations, whereas design organizations operate under weaker safety accountability, limited feedback from incident data and commercial pressures that compress the time available for safety-oriented design iteration. These structural and cultural features explain why safety culture maturity remains low in the design phase even within organizations that display comparatively stronger safety practices during construction.

A cross phase analysis further reveals a disconnect between the regulatory intent at the design stage and the actual implementation on site. While regulatory compliance characterizes design maturity, construction maturity reflects more robust operational practices. However, the lack of integration between these two phases means that safety considerations identified at the design level are not always translated effectively into field practice. This gap mirrors the findings of previous Indonesian studies that institutional fragmentation and weak inter-actor coordination hinder the evolution of a cohesive safety culture [4].

The implications for policy and practice are significant. For the government and regulators, the priority lies in strengthening the enforcement of SMKK and aligning national regulations with international frameworks such as ISO 21500 and the PMBOK Construction Extension [24,25,31]. Investment in structured training, technology-enabled safety monitoring, and bottom-up worker participation are necessary for contractors to accelerate the transition to proactive safety culture. For consultants and designers, it is crucial to embed safety-for-design principles, including risk management, quality-safety integration, and environmental planning, earlier in planning [7]. Cross-cutting efforts should emphasize the integration of digital tools as enablers of continuous improvement, echoing international evidence that integrated management systems can enhance both safety and productivity [43]. Overall, the phase gap suggests that future improvements should prioritize upstream design accountability and better cross phase coordination.

6. Conclusions

This study mapped the maturity of safety culture in Indonesia’s construction projects by assessing the design and construction phases using a purposive panel of 12 experts (questionnaire-based ratings, FGDs, and expert validation). The findings indicate that safety culture maturity remains at an intermediate level, with the design phase averaging 3.11 and the construction phase 3.36, positioned between compliant and proactive maturity. While notable strengths were identified, such as the existence of regulatory frameworks and relatively strong auditing and reporting practices, persistent weaknesses in early-stage planning, professional competence, resource allocation, digitalization, and environmental safety management were identified. These results demonstrate that Indonesia’s construction safety culture is still driven largely by compliance rather than proactive organizational learning, underscoring the need for systemic improvement.

Theoretically, this study contributes by demonstrating the importance of a phase-based maturity assessment, revealing asymmetries between design and implementation that are often overlooked in existing maturity models. It highlights that bridging the regulatory–operational gap requires more than compliance: it demands integrated action across stakeholders. Moving forward, the next critical step is to develop an integrated construction safety management framework that combines national regulations (SMKK), international project management standards (ISO 21500), and global best practices in project execution (PMBOK Construction Extension). This integrated approach can improve implementation efficiency and strengthen safety and environmental performance while supporting compliance and organizational learning [33,34,43,44,45,46]. These insights provide a roadmap for policymakers and industry stakeholders seeking to shift from compliance-driven to proactive and resilient safety culture.

Despite these contributions, this study has several limitations. First, the maturity assessment relies on a purposive panel of 12 experts, which represents a relatively small and non-random sample and may be subject to subjective evaluation bias, although it covers the main actor groups and approximately 80% of state-owned construction companies. Accordingly, the findings should be interpreted as an expert-assessed industry landscape rather than a statistically representative survey. In addition, the maturity scale was not subjected to formal statistical reliability and validity tests (e.g., internal consistency or construct validation) because the design focused on expert consensus within a small purposive panel. Second, the analysis is confined to Indonesian construction projects and reflects the specific regulatory and institutional context; therefore, the findings should be cautiously generalized to other countries or project types. Third, the study provides a cross-sectional snapshot based on expert judgments rather than longitudinal data or objective performance indicators such as multi-project accident statistics or audit scores. These limitations open up several directions for future research. Comparative studies across countries and organizational cultures could test the transferability of the safety culture maturity framework, whereas longitudinal studies could examine how maturity levels evolve as new regulations and safety initiatives are implemented. Studies that apply the instrument to larger samples of organizations and respondents should incorporate psychometric analyses to strengthen the framework’s measurement properties. Further work could also investigate how digital tools, such as BIM-based planning, integrated safety management systems, and data-driven monitoring platforms, interact with regulatory frameworks (e.g., SMKK and ISO-based standards) to accelerate the transition from compliant to proactive and resilient safety cultures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: R.A.M., A.S. and T.N.H.; Methodology: R.A.M., A.S. and T.N.H.; Validation: R.A.M., A.S. and T.N.H.; Formal analysis: M.Y.A.T. and M.A.R.M.; Investigation: R.A.M., A.S., T.N.H., M.Y.A.T. and M.A.R.M.; Data curation: R.A.M., A.S. and T.N.H.; Writing—original draft: R.A.M., A.S. and T.N.H.; Writing—review and editing: R.A.M. and M.Y.A.T.; Visualization: M.Y.A.T. and M.A.R.M.; Supervision: R.A.M.; Project administration: M.Y.A.T.; Funding acquisition: R.A.M., A.S. and T.N.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author would like to acknowledge the support of this work provided by the Directorate of Research Funding and Ecosystem, Universitas Indonesia, under Riset Kolaborasi Indonesia (RKI) Program 2025, Number of Contract PKS-615/UN2.R/HKP.05/2025.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

Appendix A. Pilot Survey

The pilot survey was conducted as the first round of the expert-panel process to validate and refine the proposed safety culture maturity sub-categories prior to the final maturity scoring. As shown in Table A1 (Design Phase) and Table A2 (Construction Phase), experts were asked a concise yes/no question for each sub-category—whether it is relevant and clearly defined for assessing safety culture maturity in the corresponding project phase. The Comments column in both tables was used to capture qualitative feedback, including suggested revisions to improve wording clarity, adjustments to reduce overlap between sub-categories, and proposals for additional sub-categories considered necessary based on field experience within the same category. Feedback from the pilot round was incorporated to finalize the sub-category list and definitions, which were then applied in the subsequent round for phase-wise maturity scoring.

Table A1.

Pilot Survey Sample Questionnaires for the Design Phase.

Table A1.

Pilot Survey Sample Questionnaires for the Design Phase.

| No. | Category | Sub-Category | Q: Is this Sub-Category Relevant and Clearly Defined for Assessing Design-Phase Safety Culture Maturity? (Y/N) | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Competence and Personnel of Designers | D1 | Knowledge, Experience, and Skills of Designers [29] | ||

Table A2.

Pilot Survey Sample Questionnaires for the Construction Phase.

Table A2.

Pilot Survey Sample Questionnaires for the Construction Phase.

| No. | Category | Sub-Category | Q: Is this Sub-Category Relevant and Clearly Defined for Assessing Construction-Phase Safety Culture Maturity? (Y/N) | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Competence and Personnel of Designers | K1 | Knowledge, Experience, and Skills of Designers [29] | ||

Note: For brevity, only item K1 is reproduced here. Similar items were developed for all remaining design-phase sub-categories (K2–K16) and were used in the questionnaire; the full instrument is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Appendix B. Final Survey

The final questionnaire was administered to the full panel of 12 experts to produce phase-wise safety culture maturity scores. For each sub-category in the design phase and construction phase, experts were instructed to select (✓) the single maturity level that best reflects typical field conditions in Indonesian building projects. Each item provides brief behavioral descriptors for the five maturity levels—Basic, Reactive, Compliant, Proactive, and Resilient—to standardize interpretation and reduce ambiguity across expert roles. The selected maturity level was then coded on a five-point scale (1–5) and aggregated across experts and sub-categories to generate the sub-category and phase-level maturity profiles reported in the Results section. Sample items for the design and construction phases are provided in Appendix B.1 and Appendix B.2.

Appendix B.1. Questionnaire for Design Phase

Select (✓) the maturity level that best reflects the actual conditions in the field for each of the following planning-phase variables.

D1. Knowledge, experience, and skills of planners: Designers possess technical knowledge, practical skills, and professional experience in integrating safety considerations during the design phase.

- o

- Basic: Designers possess very limited technical knowledge and skills; safety is almost never considered in design, with no relevant professional experience.

- o

- Reactive: Designers seek safety knowledge and skills only after incidents or problems; experience is acquired reactively, not as core competency.

- o

- Compliant: Designers meet minimum standards and include safety to satisfy regulatory requirements, but not in a deep or innovative manner.

- o

- Proactive: Designers proactively update and enhance safety knowledge, skills, and professional experience; safety is a primary consideration from the outset of design.

- o

- Resilient: Designers exemplify mastery in safety-related knowledge, skills, and experience; safety is integrated into every design aspect and knowledge is actively shared with the team.

Note: For brevity, only item D1 is reproduced here. Similar items were developed for all remaining design-phase sub-categories (D2–D15) and were used in the questionnaire; the full instrument is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Appendix B.2. Questionnaire for Construction Phase

Select (✓) the maturity level that best reflects the actual conditions in the field for each of the following construction-phase variables.

K1. K4 Standards: Implementation of national occupational safety regulations (K4) as the legal basis and standard for applying workplace safety at construction sites.

- o

- Basic: National K4 occupational safety regulation is not applied; workers and management are unaware of or ignore K4 at the construction site.

- o

- Reactive: Standards are applied only when inspections occur or after an accident; compliance is temporary and inconsistent.

- o

- Compliant: K4 standards are implemented to the minimum required level with standard reporting and documentation, yet field application is sometimes a mere formality.

- o

- Proactive: K4 standards are not only met but integrated into all aspects of project execution; the entire team actively ensures routine compliance.

- o

- Resilient: Adherence to K4 has become part of the work culture; continuous innovation and improvement aim to reach and exceed the prescribed standards.

Note: For brevity, only item K1 is reproduced here. Similar items were developed for all remaining construction-phase sub-categories (K2–K16) and were used in the questionnaire; the full instrument is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Suraji, A.; Arman, U.D. No failure no accident in man-made disasters in construction. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences, Padang, Indonesia, 29–30 September 2023; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machfudiyanto, R.A.; Latief, Y.; Suraji, A. Integration of Structure, Conduct, Performance Interrelation of Institutional Policy and Safety Culture in Construction Industry. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2022, 17, 3433–3446. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhry, R.M.; Fang, D.; Mohamed, S. Developing a Model of Construction Safety Culture. J. Manag. Eng. 2007, 23, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machfudiyanto, R.A.; Latief, Y.; Sagita, L.; Suraji, A. Identification of institutional safety factors affecting safety culture in construction sector in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Moscow, Russia, 10 March 2020; Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suraji, A. The Construction Sector of Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 19th Asia Construct Conference, Jakarta, Indonesia, 14–15 November 2013; Asia Construct: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Suraji, A.; Duff, A.R.; Peckitt, S.J. Development of Causal Model of Construction Accident Causation. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2001, 127, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endroyo, B.; Suraji, A.; Besari, M.S. Model of the Maturity of Pre-construction Safety Planning. In Procedia Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 171, pp. 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymberski, R. Construction project safety planning. TAPPI J. 1997, 80, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lestari, F.; Sunindijo, R.Y.; Loosemore, M.; Kusminanti, Y.; Widanarko, B. A Safety Climate Framework for Improving Health and Safety in the Indonesian Construction Industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadir, A.; Lestari, F.; Sunindijo, R.Y.; Erwandi, D.; Kusminanti, Y.; Modjo, R.; Widanarko, B.; Ramadhan, N.A. Safety Climate in the Indonesian Construction Industry: Strengths, Weaknesses and Influential Demographic Characteristics. Buildings 2022, 12, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adzivor, E.; Emuze, F.; Ahiabu, M.; Kusedzi, M. Scaling up a Positive Safety Culture among Construction Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Ghana. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.; Fugar, F.; Adinyira, E. Assessment of Health and Safety Culture Maturity in the Construction Industry in Developing Economies: A Case of Ghanaian Construction Industry. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2019, 18, 865–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kasasbeh, M.; Abudayyeh, O.; Olimat, H.; Liu, H.; Al Mamlook, R.; Alfoul, B.A. A Robust Construction Safety Performance Evaluation Framework for Workers’ Compensation Insurance: A Proposed Alternative to EMR. Buildings 2021, 11, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrayana, D.V.; Pribadi, K.S.; Marzuki, P.F.; Iridiastadi, H. Safety Leadership and Performance in Indonesia’s Construction Sector: The Role of Project Owners’ Maturity. Int. J. Saf. Secur. Eng. 2023, 13, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldenmund, F.W. The Nature of Safety Culture: A Review of Theory and Research. Saf. Sci. 2000, 34, 215–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, P. Safety management and safety culture: The long, hard and winding road. In Occupational Health & Safety Management Systems: Proceedings of the First National Conference; Pearse, W., Gallagher, C., Bluff, L., Eds.; Crown Content: Melbourne, Australia, 2001; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, A.R. Safety Management in Production. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. 2003, 13, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, P. Applying the Lessons of High Risk Industries to Health Care. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2003, 12, i7–i12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, P.; Hoult, S. The safety journey: Using a Safety Maturity Model for Safety Planning and Assurance in the UK Coal Mining Industry. Minerals 2013, 3, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashya, C.R.; Machfudiyanto, R.A.; Suraji, A. Fostering a Total Construction Safety Culture to Enhance Safety Performance in Indonesia’s New Capital City Establishment. Int. J. Saf. Secur. Eng. 2024, 14, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golabchi, H.; Pereira, E.; Lefsrud, L.; Mohamed, Y. Proposal of a safety maturity framework in construction: Implementing leading indicators for proactive safety management. J. Saf. Sustain. 2025, 2, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E. A multi-level safety culture maturity model for (new) building projects in Hong Kong. HKIE Trans. Hong Kong Inst. Eng. 2023, 30, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, M.T.; Feng, Y. A Maturity Model for Resilient Safety Culture Development in Construction Companies. Buildings 2022, 12, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 21500; Project, Programme and Portfolio Management-Context and Concepts. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Project Management Institute. Construction Extension to the PMBOK® Guide, 2nd ed.; Project Management Institute: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wendler, R. The Maturity of Maturity Model Research: A Systematic Mapping Study. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2012, 54, 1317–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, J.; Latief, Y.; Machfudiyanto, R.A. Building a Safety Culture in the Construction Sector: A model to assess the safety maturity of a company. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Bandung, Indonesia, 6–8 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mulyasari, W.; Ciptomulyono, U.; Sudiarno, A. A Critical Review of Safety Culture Maturity Model Tools. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, IEEM 2023, Singapore, 18–21 December 2023; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1083–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, C.K.I.C.; Belayutham, S.; Mohammad, M.Z.; Ismail, S. Development of a Conceptual Designer’s Knowledge, Skills, and Experience Index for Prevention through Design Practice in Construction. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 148, 04021199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Undang-undang (UU) Nomor 2 Tahun 2017; Tentang Jasa Konstruksi; Jakarta, Indonesia. 2017. Available online: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/37637/uu-no-2-tahun-2017 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Ministry of PUPR. Regulation of the Minister of Public Works and Housing of the Republic of Indonesia Number 10 of 2021 on Guidelines for Construction Safety Management Systems; Ministry of PUPR: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Afzal, M.; Shafiq, M.T. Evaluating 4D-BIM and VR for Effective Safety Communication and Training: A case Study of Multilingual Construction Job-Site Crew. Buildings 2021, 11, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, K.M.P.; Picchi, F.; Camarini, G.; Chamon, E.M.Q.O. Benefits in the Implementation of Safety, Health, Environmental and Quality Integrated System. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2015, 7, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.; Mendes, F.; Barbosa, J. Certification and Integration of Management Systems: The Experience of Portuguese Small and Medium Enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1965–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Tayeh, B.A.; Alaloul, W.S.; Aisheh, Y.I.A.; Frijah, M.M. The Role of Client in Fostering Construction Safety During the Planning and Design Stages. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 24, 1659–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Fang, D.; Li, N. Roles of Owners’ Leadership in Construction Safety: The Case of High-Speed Railway Construction Projects in China. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 1665–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiu, N.S.N.; Chan, D.W.M.; Sze, N.N.; Shan, M.; Chan, A.P.C. Implementation of Safety Management System for Improving Construction Safety Performance: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Buildings 2019, 9, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiu, N.S.N.; Chan, D.W.M.; Shan, M.; Sze, N.N. Implementation of Safety Management System in Managing Construction Projects: Benefits and Obstacles. Saf. Sci. 2019, 117, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Qiao, W. A hybrid STAMP-fuzzy DEMATEL-ISM Approach for Analyzing the Factors Influencing Building Collapse Accidents in China. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 45001:2018; Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Apriyati, R.; Latief, Y. Knowledge Base Integration Management System Quality, Safety and Environmental to Improve Organizational Performance in Construction Company. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 20–22 December 2020; IOP Publishing Ltd.: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, T.R.; Machfudiyanto, R.A.; Riantini, L.S. Conceptual Framework of Safety Leadership Relationship to Safety Culture in Increasing Safety Performance of Construction Projects. Indones. J. Multidisiplinary Sci. 2022, 1, 1037–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, N.; Omidvari, M.; Meftahi, M. The Effect of Integrated Management System on Safety and Productivity Indices: Case Study; Iranian Cement Industries. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 1180–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.X.; Lou, G.X.; Tam, V.W.Y. Integration of Management Systems: The Views of Contractors. Arch. Sci. Rev. 2006, 49, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, A.N.; Morgado, C.R.V.; De Souza, D.I. A Case Study on the Integration of Safety, Environmental and Quality Management Systems. In Proceedings of the Industrial Engineering Research Conference, Nashville, TN, USA, 19–23 May 2007; pp. 1190–1195. [Google Scholar]

- Moumen, M.; El Aoufir, H. Quality, Safety and Environment Management Systems (QSE): Analysis of Empirical Studies on Integrated Management Systems (IMS). J. Decis. Syst. 2017, 26, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.