1. Introduction

With the rapid development of the construction industry, engineering projects are becoming increasingly complex and large in scale, posing challenges for productivity management and operational efficiency [

1]. As a key component of construction production, construction equipment directly influences construction efficiency, and its associated costs represent a major portion of total project expenditure [

2]. Therefore, the intelligent management of construction equipment is essential for improving efficiency, reducing costs, and shortening the project duration. Due to the particularity of construction activities, many construction machines perform repetitive actions, and their productivity is typically determined by the number of cycles within a certain period of time [

3]. For instance, during excavator operations, a working cycle generally consists of digging, lifting, swinging, loading, and lowering. Recognizing excavator actions enables measurement of cycle counts and duration, providing critical data for productivity analysis and project management [

4]. Moreover, accurate recognition of excavator actions plays a critical role in safety monitoring, energy optimization, and operational scheduling [

5].

Traditional methods for excavator action recognition mainly rely on sensor technologies to collect the position and motion data of the target equipment for pose estimation and action classification. These technologies include the Global Positioning System (GPS) [

6,

7], Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) technology [

8,

9], Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) [

10] and Real-time Location Systems (RTLS) [

11], among others. Although effective in controlled environments, these systems often suffer from high costs, complex installation and maintenance, sensor aging, and environmental interference, limiting long-term stability in complex construction sites. Consequently, vision-based recognition methods have gained increasing attention due to their non-intrusive nature and ease of deployment.

Previous research has explored various activity recognition methods based on images or videos, including Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [

12], Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [

13], and Transformer-based architectures [

14,

15]. CNN has strong spatial feature extraction capabilities and is widely used in static image analysis and short-term action classification tasks [

16]. RNN and its variants, such as LSTM and GRU, can capture temporal dependencies in video sequences, providing advantages for modeling the dynamic characteristics of construction machinery actions [

16,

17,

18]. Transformers, incorporating global attention mechanisms, have demonstrated significant potential in capturing long-term temporal dependencies [

19,

20].

Despite these advances, excavator action recognition remains challenging due to the high similarity and continuity between actions, particularly during transitions, e.g., from digging to lifting or swinging to dumping. Differences often occur only in subtle component trajectories or posture changes [

21], which frequently lead to recognition errors. This misclassification problem not only occurs in automated vision-based recognition systems but also during manual annotation, particularly in the absence of consecutive frames for reference [

12]. To solve this problem, current studies have introduced the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks. Global spatial features are first extracted from each frame using image feature extraction methods such as CNN and ViT (Vision-based Transformer) [

12,

14], and then the LSTM captures the temporal relationships between consecutive frames for action recognition. However, in excavator action recognition, not all image features are relevant to the actions. CNN, ViT and similar algorithms encode background, non-critical components and other irrelevant details, resulting in long feature vectors with substantial noise. And the extracted features contain a large amount of irrelevant information and are purely three-dimensional, which prevents them from capturing the three-dimensional spatial relationships.

To overcome these limitations, this study proposes an excavator action recognition method based on skeletal keypoints and monocular depth estimation network. First, the YOLOv8 pose estimation model is used to locate the skeletal keypoints of excavator, obtaining the 2D coordinates [

22]. Then, the relative depth information of each keypoint is obtained through the monocular depth estimation network, resulting in the 3D spatial information of the excavator’s skeletal keypoints [

23]. Furthermore, the 3D spatial feature sequences of keypoints in consecutive frames are input into the LSTM network to learn the spatiotemporal variation patterns of the excavator, enabling accurate action classification [

16].

Compared with traditional classification methods based on single-frame images or 2D visual features, this study makes the following contributions:

A novel excavator action recognition method is proposed that integrates 2D skeletal keypoints with 3D depth information. By using the 3D spatial features of the excavator’s keypoints as input, the method reduces the length of the feature sequence while improving the accuracy of action recognition;

An LSTM-based temporal model is introduced, which incorporates the spatiotemporal relationships across consecutive frames, effectively reducing misclassification during action transitions and occlusions;

The method does not require additional hardware deployment and can directly utilize existing video surveillance resources on construction sites to perform action recognition and classification tasks.

Previous hybrid methods or skeleton-based methods have primarily relied on 2D image information, which can be easily affected by complex environmental interference, object occlusions, and action transitions, leading to recognition errors. Most past studies have focused on global image feature extraction while neglecting the importance of depth information, resulting in less precise feature extraction for excavator action recognition. To address this gap, this study proposes a novel excavator action recognition method based on skeletal keypoints and monocular depth estimation, providing a more accurate 3D spatial representation. This approach effectively resolves the accuracy issues faced by existing methods in complex scenarios.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents related work on excavator action recognition.

Section 3 details the proposed framework, including the specific components and implementation of each module.

Section 4 describes the experimental setup and training process.

Section 5 reports and discusses the experimental results. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper and discusses directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

Traditional excavator action recognition methods mainly rely on manual observation and recording, which are time-consuming, labor-intensive and easily influenced by subjective factors, resulting in low efficiency and limited accuracy [

24]. With the development of big data technology, internet technology, computer vision, and Building Information Modeling (BIM), the use of intelligent and automated technologies for excavator activity recognition has gradually become a research hotspot [

25]. Based on the data source, these research methods can be classified into non-vision-based methods and vision-based methods [

26].

2.1. Non-Vision-Based Action Recognition Methods

Non-visual-based methods primarily depend on sensor technologies to collect positional and motion data of target equipment for further analysis, such as Global Positioning System (GPS) [

6,

7], Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) [

8,

9], Inertial Measurement Units (IMU) [

10], and Real-Time Location System (RTLS) [

11].

For instance, Montaser et al. [

6] installed GPS sensors on trucks to obtain travel trajectories and spatial data, including direction, speed, time, and location. These data were then used to calculate truck productivity during earthmoving operations. Hu Lian et al. [

10] proposed an excavator bucket pose measurement method based on the BeiDou Navigation Satellite System (BDS) and Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU), which provides a foundation for intelligent guidance in precise excavator operations. Fang Y et al. [

27] developed a real-time active safety assistance framework for mobile crane lifting operations, which can accurately reconstruct crane movements in real time and provide proactive warnings, enabling operators to make timely decisions to mitigate risks. Lim et al. [

28] developed a portable Real-Time Location System (RTLS) using accelerometer and Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) sensors to track multiple laborers’ movements in confined construction sites, achieving high positioning accuracy in field tests and providing a practical solution for improving construction site safety.

However, non-visual-based methods for construction machinery action recognition still have several limitations, such as high sensor costs, susceptibility to aging, the need for regular replacement, and vulnerability to construction site conditions. These limitations restrict their long-term deployment in complex construction environments. Therefore, there has been a growing trend in recent years toward using vision-based methods for excavator action recognition.

2.2. Vision-Based Action Recognition Methods

With the widespread adoption of surveillance cameras in the construction sites, the acquisition of visual data has become more convenient and cost-effective [

26]. These cameras are typically installed at elevated positions, which also helps to reduce occlusions [

28]. Vision-based methods primarily acquire image or video data through surveillance cameras and use computer vision techniques to process and analyze the data for construction machinery action recognition [

29].

For example, Gong et al. [

30] developed a testing platform that integrates a Bag-of-Video-Feature-Words model with Bayesian learning methods to learn and classify actions of construction workers and equipment. Golparvar-Fard et al. [

31] extracted spatiotemporal interest points and described each feature using the Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG), representing videos as a set of feature vectors. A multi-class Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier was then used to automatically learn the distribution of spatiotemporal features and action categories, enabling earthmoving machinery action recognition. Kim I. S. et al. [

16] proposed a novel method for classifying excavator activities by processing visual information from video frames adjacent to the current frame. A pre-trained CNN model extracts sequential patterns of visual features from the video frames, and a BiLSTM analyzes the outputs of the pre-trained CNN to classify different excavator activities. Kim J. et al. [

12] proposed a vision-based action recognition framework that considers the sequential working patterns of earthmoving excavators and integrates excavator detection, tracking and action recognition for automated cycle time and productivity analysis.

Although vision-based methods have shown significant potential, they still face several challenges. Different excavator actions often exhibit subtle differences in spatial position and posture. This is particularly true during action transitions (e.g., lowering to digging or swinging to loading), which can cause confusion and reduce recognition accuracy [

12,

31]. Moreover, the construction environment is complex and dynamic, with factors such as varying illumination, occlusions, and cluttered backgrounds [

16,

30,

31], which make action recognition methods that rely solely on 2D image features prone to misclassification. In many studies using traditional algorithms such as CNN and Transformer for feature extraction, the input features contain redundant information, which reduces the accuracy of action recognition.

Therefore, the overall objective of this study is to develop an excavator action recognition method that combines 2D skeletal keypoints with 3D depth information. Specifically, the YOLOv8 pose estimation model is first used to locate the excavator’s skeletal keypoints and obtain 2D coordinate information. Subsequently, a monocular depth estimation network is employed to extract relative depth data from the images, and the 2D information is combined with the 3D depth to generate the excavator’s 3D spatial sequence features. These sequential features are then input into an LSTM model to learn the temporal dynamics and classify excavator actions. The proposed method enhances recognition accuracy, reduces redundancy, and achieves robust performance under complex construction conditions.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Framework

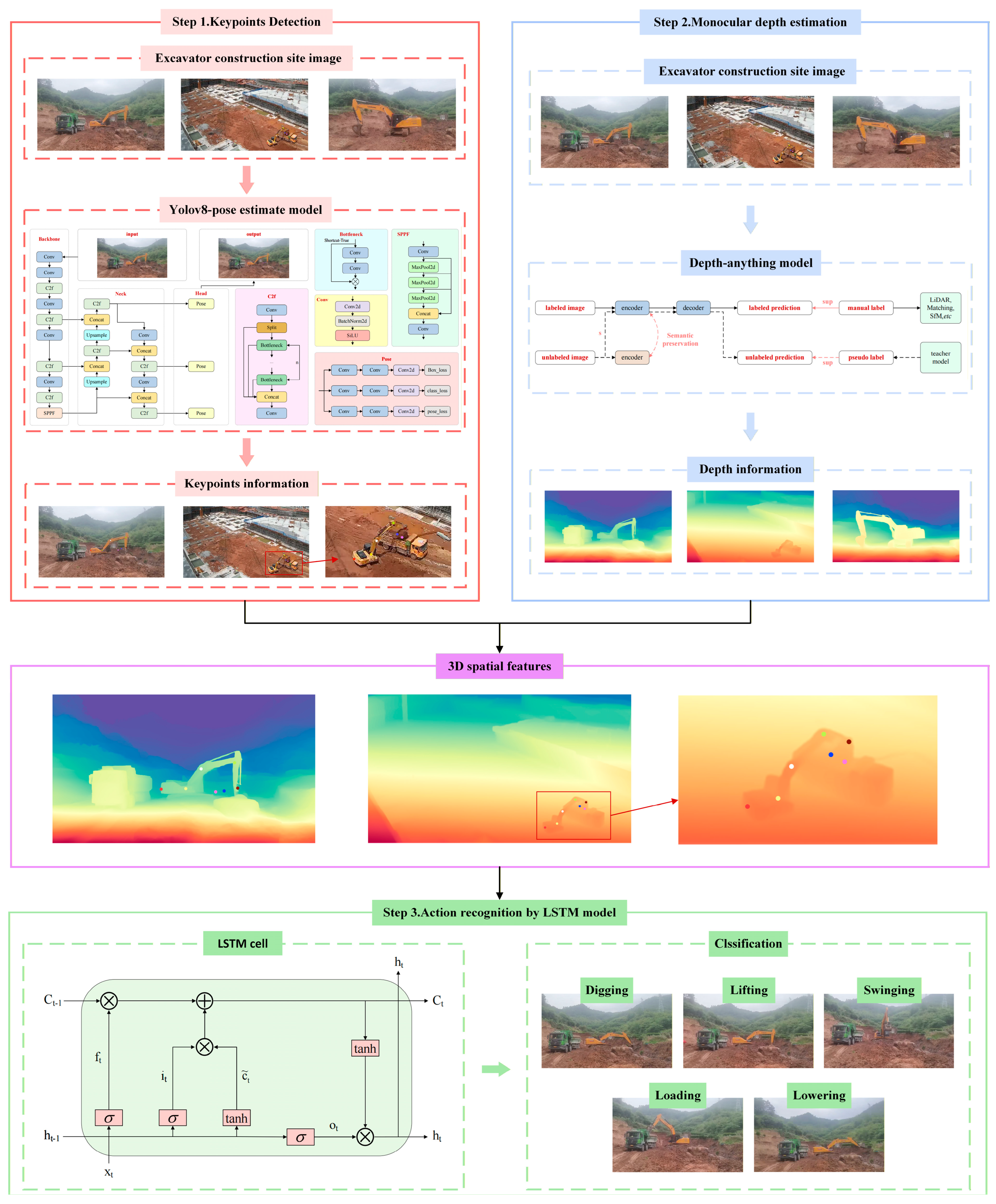

This section provides a detailed description of the proposed research framework, which mainly consists of three components: keypoint detection, monocular depth estimation, and the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model. The overall framework of the proposed method is illustrated in

Figure 1.

First, images of excavators from construction sites are collected and used as raw data that are input into two parallel processing branches. These raw data serve as the foundation for all subsequent analysis and processing. To extract useful information from the input images, this study employs two parallel models. In the first branch, the YOLOv8 pose estimation model is employed to detect excavators and estimate their skeletal keypoints [

32], producing the corresponding keypoint information as output. This model enables precise localization of the excavator’s keypoints, generating 2D skeletal keypoint information for the excavator [

33], and provides structured 2D keypoint data for subsequent action classification. In the second branch, the Depth-Anything model [

34] is applied to the same input images. This model generates pixel-level depth information from a single image, capturing the 3D spatial relationships within the scene [

35]. It provides 3D depth information for the excavator keypoints, compensating for the limitations of 2D keypoints in spatial representation. These two models operate in parallel, extracting skeletal keypoint information and depth information from the input images, respectively. The extracted keypoint and depth information are then integrated to form a 3D spatial feature sequence, which is input into the LSTM model. The LSTM model utilizes these feature data to learn and train on the temporal variations in the features. It can ultimately predict the action classes of images in an unseen test set, providing accurate recognition and classification of excavator actions [

16].

In summary, this study proposes an excavator action recognition method based on skeletal keypoints and a monocular depth estimation network. Compared with traditional methods that rely solely on 2D image features, the proposed method more comprehensively captures the excavator’s 3D spatial features and temporal dynamics. By providing more precise feature representations of the excavator’s action states, it enables accurate classification and recognition of excavator actions.

3.2. Keypoint Detection

Keypoint detection is a crucial step for capturing the spatial information of the excavator. Its purpose is to extract the precise locations of the excavator’s skeletal keypoints from 2D images and output them as structured keypoint coordinate information, enabling subsequent 3D spatial information fusion and action recognition.

For extracting skeletal keypoint features of the excavator, this study employs the YOLOv8 pose estimation model for keypoint detection. YOLOv8 (You Only Look Once, version 8) is an end-to-end object detection algorithm. Compared with traditional multi-stage methods, it offers advantages such as high detection speed, ease of deployment, and a balanced performance between accuracy and real-time capability [

32]. The YOLOv8 pose estimation model is built upon the YOLOv8 deep convolutional network and enables precise keypoint detection. The network architecture of YOLOv8 pose estimation mainly consists of the Backbone, Neck, and Head components, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

Backbone: The backbone network is primarily responsible for extracting and refining multi-scale visual features from the input image, serving as the foundation for subsequent detection tasks [

36]. It mainly consists of three key modules: Conv, C2f, and SPPF. The Conv module employs a standard convolutional layer (with a 3 × 3 kernel and a stride of 2) as the primary feature extraction layer. The BatchNorm2d layer performs normalization on each channel of the convolutional output. The SiLU function is used as the activation function. The C2f module is a lightweight key component in YOLOv8, which replaces the CSP module used in YOLOv5. The C2f module is a lightweight key component in YOLOv8, which replaces the CSP module used in YOLOv5. Its primary characteristic involves an input channel split, where a portion of the features is routed through multiple Bottleneck sub-modules to extract deep semantic information, while the remaining part is directly passed through as a shortcut branch to preserve the original features. Subsequently, the outputs from all branches are concatenated along the channel dimension, followed by a 1 × 1 convolution to achieve feature fusion and channel compression. The SPPF module is located at the end of the backbone network. It performs max pooling operations at multiple spatial scales, and then concatenates all the resulting feature maps with the original input [

37].

Neck: The neck network serves as a crucial component of the YOLOv8-pose estimate model for feature fusion. Its primary objective is to efficiently integrate multi-scale features extracted from different stages of the backbone network, enabling the model to capture rich multi-scale contextual information, which is essential for small object detection and accurate keypoint localization. The neck network is primarily composed of four modules: Concat, Upsample, C2f, and Conv. The Concat module is responsible for channel-wise concatenation of feature maps from different stages of the network. The Upsample module employs the bilinear interpolation method to resample low-resolution feature maps to higher resolutions. Within the neck network, the C2f module is further used for feature fusion and transformation, processing the feature maps after concatenation and upsampling [

38]. The Conv module in the neck network primarily fuses and enhances the multi-scale features from the backbone network that have undergone concatenation and upsampling, with a basic structure similar to that of the backbone network. The neck network fuses multi-scale feature maps from the backbone through both top-down and bottom-up pathways, enhancing the network’s ability to integrate features of objects at different scales.

Head: The head network serves as the final output part of the network. It adopts a decoupled structure and uses an anchor-free mechanism to improve detection performance, primarily consisting of the Pose module. The Pose module is a small convolutional network composed of several Conv layers. It receives feature maps at three different scales from the neck and simultaneously performs predictions for object detection and pose estimation [

39]. In this module, the Pose branch predicts the coordinates and confidence of keypoints, outputting the 2D position of each keypoint. The Box and Class branches (optional) perform the object detection tasks, including bounding box regression and class prediction.

To accurately describe the excavator’s motion states and spatial positions, this study defines seven keypoints based on the excavator’s operational characteristics and mechanical structure: excavator body end, excavator cab boom, excavator boom middle, excavator boom arm, excavator arm bucket, excavator right bucket end, and excavator left bucket end. As shown in

Figure 3, these keypoints form the skeletal structure of the excavator.

The excavator body end represents the rearmost position of the excavator chassis, reflecting the position and motion state of the chassis. The excavator cab boom represents the hinge between the front of the excavator cab and the base of the boom. It serves as the boundary between the upper rotating structure and the chassis and acts as the initial reference point for the boom system’s motion. The excavator body end and excavator cab boom together constitute the chassis of the excavator. The excavator boom middle represents the midpoint of the boom and serves as an auxiliary reference point, providing a more precise indication of the boom’s position, angle, and spatial changes during its movement. The excavator boom arm represents the hinge between the boom and the arm, which is critical for executing various excavator actions. Its motion trajectory directly determines the operational range of the excavator and is the part where movement changes are most pronounced during operation. The excavator arm bucket represents the connection between the arm and the bucket, influencing the bucket’s motion trajectory, operational state, and digging performance. It serves as a critical pivot point during action transitions. The excavator right bucket end and excavator left bucket end are located at the two ends of the bucket. Relative to the cab, these two points together define the working plane and operational state of the bucket, providing information on the bucket’s posture, angle, load condition, and spatial position.

Collecting and analyzing the 3D spatial information of these seven keypoints allows for precise identification of the excavator’s action categories and operational states, providing structured data for subsequent action classification tasks. Through the YOLOv8 pose estimate model, the excavator’s skeletal keypoint information can be accurately extracted. Compared with traditional keypoint detection methods based on handcrafted features or template matching, this method offers higher automation, stronger adaptability and better robustness to complex backgrounds.

3.3. Monocular Depth Estimation

In excavator action recognition tasks, relying solely on the excavator’s 2D skeletal keypoint information is insufficient to comprehensively represent its actual motion states. Due to the loss of depth information and perspective compression inherent in the projection of 3D scenes onto 2D images, different actions performed by the excavator in 3D space may appear highly similar or even identical in the 2D images. Analyzing actions based only on 2D keypoints can therefore result in feature redundancy across different actions, leading to misclassification.

Therefore, incorporating depth information of the excavator is essential, as it allows the skeletal keypoints to be accurately located in 3D space, thereby obtaining more precise and detailed spatial motion sequence features of the excavator. Current research on depth estimation primarily includes sensor-based methods, multi-view stereo and monocular depth estimation [

40]. Considering the practical conditions of construction sites, sensor deployment entails high costs and frequent maintenance, while the existing camera setup cannot meet the requirements of multi-view stereo. Therefore, this study adopts a monocular depth estimation method to obtain the excavator’s depth values, enabling depth estimation directly from images captured by construction site surveillance cameras.

Monocular depth estimation is a technique that predicts pixel-level depth information of a scene from a single 2D image. It can directly estimate scene depth in an end-to-end manner, with the primary task being to infer 3D spatial information from a 2D image in the absence of geometric constraints and stereo disparity [

41].

This study adopts the Depth Anything Model (DAM), a monocular depth estimation model trained on large-scale unlabelled data. The specific architecture of the model is illustrated in

Figure 4.

The Depth Anything Model (DAM) is a monocular depth estimation method based on a teacher-student collaborative learning framework. First, a trained teacher model is trained on a relatively small labeled dataset. The teacher model is then used to generate pseudo-labels for a large collection of unlabeled images. Finally, the student network, which forms the final model, is trained using this extensive pseudo-labeled dataset combined with more challenging data augmentation strategies, forming the overall model architecture [

34]. The overall architecture primarily consists of three components: teacher model training, pseudo-label generation and student model training.

Teacher model training: The teacher model is trained using a relatively small dataset with ground-truth depth annotations (e.g., depth data from LiDAR, SfM or multi-view matching). The input labeled images are first processed by an encoder to extract multi-scale features, which are then passed through a decoder to progressively restore spatial resolution, ultimately producing the corresponding depth predictions [

42].

Pseudo-label generation: The dataset used in this study is self-collected, and obtaining ground-truth depth is challenging; therefore, it does not contain real depth annotations. In this study, the trained DAM is directly applied to a large set of unlabeled excavator images to generate predictions, producing pseudo-labels in the form of pseudo-depth maps. These pseudo-depth maps not only provide pixel-level depth information but also reduce prediction errors through confidence-based filtering and smoothing, maintaining particularly high accuracy for critical excavator components such as the boom and bucket.

Student model training: In the third stage, the pseudo-labels generated in the previous stage are used as supervisory signals to train the final student model. The student model has a structure similar to the teacher model, adopting an encoder–decoder architecture, but its parameters are reinitialized [

43]. After training, the student model is able to generate high-quality depth predictions for unlabeled excavator images. In the subsequent action recognition stage, this study utilizes the depth maps output by the student model as 3D features input to the LSTM model.

Through the DAM, depth information of the excavator can be accurately extracted and integrated with the keypoint coordinate information to form 3D spatial feature sequences. This process elevates the originally 2D keypoint features to 3D, yielding sequential information that precisely represents the excavator’s motion patterns and provides more accurate feature inputs for subsequent LSTM model training. Moreover, for image frames corresponding to action transitions, even when the 2D keypoint coordinates are identical or highly similar, actions can be distinguished based on differences in depth information, thereby improving the accuracy of action recognition. For images with partial occlusion, it can still provide richer spatial information of the excavator, facilitating the LSTM in learning and accurately recognizing its actions.

3.4. Long Short-Term Memory

Excavator operations are continuous and regular mechanical processes, where the action recognition in each frame is highly dependent on the states of preceding and subsequent frames. While traditional models such as CNN, Transformer and YOLO excel at extracting spatial features, but they treat each frame as an independent image and rely solely on static image information. As a result, they fail to capture the temporal dynamics between frames, which can easily lead to misclassification during action transitions.

In contrast, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks have significant advantages in processing temporal relationships and dynamic processes. Through the gating mechanisms of the forget gate, input gate, and output gate, LSTM can effectively learn, retain, and update the temporal dependencies present in long sequential data [

44]. For excavators, this means that the model can not only recognize the action state in the current frame but also understand the motion trends across preceding and succeeding frames, thereby improving the accuracy of action recognition.

The basic structure of an LSTM unit is illustrated in

Figure 5. A standard LSTM unit typically consists of the following components:

Input gate it: Determines which new information is stored in the cell state, consisting of a sigmoid layer and a tanh layer.

Forget gate ft: Determines how much information from the previous cell state (ct−1) should be retained or discarded.

Output gate ot: Determines the output at the current time step by analyzing the cell state (ct) to produce the final output.

Cell state ct: Used to preserve memory information across the temporal dimension, transmitting information through each time step in the network and carrying the long-term dependencies of the sequence.

All these gates are mapped to values between 0 and 1 through the sigmoid function. The input gate, forget gate, and output gate each operate in conjunction with a candidate cell state to regulate information flow within the LSTM unit [

45].

Specifically, for a given time step

t, with the input vector

xt and the previous hidden state

ht−1, the computation process of the LSTM is as follows:

where

is the candidate cell state, denotes the sigmoid activation function, tanh denotes the hyperbolic tangent activation function, ⊙ represents element-wise multiplication,

Wf,

Wi,

Wo,

WC are the input weight matrices,

Vf,

Vi,

Vo,

VC are the hidden state weight matrices, and

bf,

bi,

bo,

bC are the bias vectors.

In this study, to fully leverage the 3D spatial structure and temporal dynamic characteristics of the excavator, the keypoint coordinates extracted from 2D images are integrated with depth information and used as feature sequences for training the LSTM model. Specifically, each frame consists of 3D information from seven keypoints, including the x and y coordinates of each keypoint and the corresponding depth value. In other words, the excavator’s state in each frame is encoded as a 21-dimensional feature vector, which effectively represents the 3D spatial motion of the excavator, filters out a large amount of irrelevant information, and ensures that the input features provide a highly concise summary of the excavator’s motion state. Subsequently, consecutive frames are organized in temporal order to form an input sequence X = [x1,x2,……,xT], capturing the spatiotemporal features of the excavator. This sequence is then input into the LSTM model for training. The LSTM model can integrate the excavator’s 3D spatial sequence features with temporal dependencies to perform spatiotemporal learning and training, ultimately enabling accurate classification of the excavator’s actions.

The performance of an LSTM model is influenced by several design parameters. To optimize the model’s performance, we carefully select and adjust the following four key LSTM design parameters, as shown in

Table 1:

Hidden Units: The number of hidden units determines the model’s capacity. A larger number of hidden units enables the model to capture complex temporal patterns but may lead to overfitting and higher computational cost. We choose 32 hidden units to balance learning capability and computational efficiency.

Layer Count: The number of LSTM layers determines the network depth. More layers allow for learning more complex features, but excessive layers can cause gradient issues. We select 2 layers to effectively capture temporal dependencies while avoiding these problems.

Dropout Rate: Dropout helps prevent overfitting by randomly deactivating neurons during training. But a higher dropout rate may limit model capacity. We set the dropout rate to 0.3 to ensure regularization while maintaining sufficient model capacity.

Sequence Length: Sequence length defines how many consecutive frames are input into the LSTM. Longer sequences capture more temporal dependencies but increase computation and may cause gradient issues. We choose a sequence length of 10 frames to balance temporal capture and computation efficiency.

4. Experiments

4.1. Data Collection

In this study, excavator operation videos were collected using on-site surveillance cameras and smartphones across multiple construction scenarios at two different construction sites. The images cover various scenarios, such as different lighting conditions, environmental changes, object occlusions and action transitions. A total of eight video clips were recorded, each lasting 1–5 min, with an overall duration of 20 min. Each clip contains at least five complete work cycles. Based on the collected videos, a sequential image dataset was created by extracting frames in temporal order. For each video, 80–120 high-quality images were selected. The dataset was then processed through cleaning and data augmentation techniques, including rotation, scaling, cropping, and brightness adjustment. These steps enhance the model’s robustness to varying environmental conditions. Based on the inherent characteristics and operational states of excavator operations, we classify excavator actions into five categories: digging, lifting, swinging, loading, and lowering. In contrast to many studies that categorize excavator actions into three types—digging, swinging, and loading—we define a complete work cycle of an excavator as comprising digging, lifting, swinging, loading, swinging, and lowering, based on the excavator’s operational states and movement trajectories. Our more detailed classification of excavator activities enables more precise capture and recognition of each work phase, which enhances the accuracy and reliability of the proposed action recognition method. Moreover, this refined classification helps to provide a more comprehensive understanding of excavator work behaviors, offering valuable data for subsequent safety monitoring and operational optimization.

In total, 875 images were collected in this study and were split into training and validation sets at a ratio of 4:1.

Figure 6 shows examples of the collected images, including excavator images captured under different scenes, distances and lighting conditions. To evaluate the applicability of the proposed method to partially occluded excavators, the dataset also includes a subset of images with occluded excavators, as shown in

Figure 6b. We believe that the created dataset is sufficient to validate the proposed method, as it includes images captured under various construction scenarios and at different distances. The dataset covers all action categories of the excavator, with nearly 200 images dedicated to each action category. Additionally, the images were collected in chronological order, which allows for capturing the entire work cycle of the excavator’s actions. The dataset also includes images from complex environments, such as those with occlusions and action transitions.

4.2. Experiments Details

Based on the constructed dataset, all experiments were conducted on a computing device equipped with an RTX 4060 GPU (manufactured by MECHREVO, Beijing, China), using the PyTorch (version 2.2.2) deep learning framework. The average runtime for processing a single video frame was approximately 25 ms, corresponding to 40 FPS, which ensures real-time applicability. To ensure experimental consistency and fairness, all experiments were conducted with consistent parameter settings. The input spatial sequence data were normalized, with an initial learning rate of 0.001, batch size of 32, and 600 training epochs. The Adam optimizer was used, with cross-entropy loss as the objective function, and an early stopping strategy was employed to prevent overfitting during training.

First, the collected excavator image dataset was manually annotated with skeletal keypoints to establish ground-truth labels. After annotation, the dataset was divided into training and validation sets at a ratio of 4:1, which were then used for model training and performance evaluation. Subsequently, the YOLOv8 pose estimate model was trained on the dataset to achieve automatic detection of the excavator’s keypoints. Using the trained model, keypoint detection can be performed on new images. The model outputs keypoint information in the form of 2D coordinates, including the x and y positions of each keypoint along with their corresponding confidence scores. Similarly, the collected raw image dataset is fed into the DAM to obtain depth maps of the excavator. By combining the depth values obtained from the DAM with the keypoint coordinate information derived from the YOLOv8 pose model, 3D spatial feature sequences were constructed. Finally, the 3D spatial feature sequences of the skeletal keypoints are input into the LSTM model for training, enabling temporal learning and action recognition based on the excavator’s spatiotemporal motion characteristics.

To evaluate the reliability and effectiveness of the proposed method, ablation experiments were conducted by comparing three different model configurations: Keypoints + LSTM, Depth + LSTM, and Keypoints + Depth + LSTM. This comparison aimed to assess the individual and combined contributions of skeletal keypoint information and depth information to the overall action recognition performance.

To further assess the performance advantages of the proposed method that integrates skeletal keypoints and depth information, this study compares it against several conventional image feature-based models, including CNN, ViT (Vision Transformer), CNN + LSTM, and ViT + LSTM. Among these, CNN and ViT represent typical approaches that rely solely on 2D spatial image features, whereas CNN + LSTM and ViT + LSTM incorporate temporal sequence modeling based on 2D spatial representations. This comparative analysis effectively highlights the improvements in action recognition accuracy achieved by the proposed method.

To evaluate the performance of the proposed method in practical construction site scenarios, a test set comprising 100 images was collected. These images were not included in either the training or validation sets and did not contain ground-truth labels. The test images were first input into the previously trained Keypoints + Depth + LSTM model for inference. For comparative analysis, the same test set was also evaluated using the best-performing CNN + LSTM model trained under identical conditions.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

The evaluation metrics were designed to provide an objective and quantitative assessment of the model’s performance, enabling the identification of its strengths and limitations and guiding subsequent optimization and improvement. To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the action recognition model, four metrics were adopted: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1 score. Accuracy represents the ratio of correctly classified samples to the total number of samples, as expressed in Equation (9). Precision measures the accuracy of the model’s positive predictions, representing the proportion of true positive instances among all samples classified as positive by the model, as shown in Equation (10). Recall measures the ability of the model to correctly identify true positive samples, that is, the proportion of all actual positive instances that are successfully detected by the model, as shown in Equation (11). The F1 score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a comprehensive evaluation of the model performance, as shown in Equation (12).

where True Positive (

TP) refers to instances where both the ground truth and the model prediction are positive, False Positive (

FP) refers to instances where the ground truth is negative but the model predicts them as positive, False Negative (

FN) refers to instances where the ground truth is positive but the model predicts them as negative, and True Negative (

TN) refers to instances where both the ground truth and the model prediction are negative.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Results of Keypoints Detection

The YOLOv8 Pose model was employed for excavator skeleton keypoint detection, using an input image size of 1920 × 1080 pixels for both training and prediction.

Figure 7 illustrates the visualization of the detected keypoints, with each keypoint clearly labeled. The detection results demonstrate that the model can accurately identify the main structural points of the excavator across different poses and working conditions.

For quantitative analysis, the spatial positions of each keypoint were extracted and recorded as 2D coordinates, which are stored in text file format for subsequent processing. The results indicate that the model achieves excellent detection performance and provides reliable structured data suitable for further temporal analysis or motion modeling. This confirms that the YOLOv8 Pose model is effective for excavator keypoint detection and can serve as a foundation for subsequent action recognition.

5.2. Results of Monocular Depth Estimation

The results of monocular depth estimation for the excavator are visualized in

Figure 8, where the output is presented as a color-coded depth map, with different colors representing varying depth values. Direct interpretation of the color depth map yields (R, G, B) values across three channels. To extract structured depth information suitable for quantitative analysis, the color depth map was first converted to grayscale. The resulting grayscale depth values were then combined with the 2D coordinates of the detected skeleton keypoints to compute the relative depth of each keypoint. Each keypoint is therefore associated with a single depth value, enabling the construction of a 3D spatial coordinate sequence for the excavator. The sequence contains 21 keypoints per frame, forming a structured 3D feature representation. The results show that the DAM can provide effective depth information, and this structured 3D data provides a data basis for subsequent action recognition.

5.3. Results of Ablation Experiments

The 3D spatial feature sequences obtained from the previous steps were input into the LSTM model for training and ablation studies. The results of the ablation study are shown in

Table 2. The proposed method achieved a precision of 93.44%, a recall of 87.21%, an F1 score of 89.68%, and an accuracy of 91.43%. Compared with the experiment using only keypoint information with LSTM, the precision increased by 6.31% and the recall by 1.67%. Compared with the experiment using only depth values with LSTM, the precision increased by 6.32% and the recall by 4.58%. These results indicate that combining keypoint and depth information substantially enhances the model’s detection performance.

5.4. Results of Comparative Experiments

The results of the comparative experiments are presented in

Table 3. As shown, the proposed method outperforms traditional image feature-based approaches [

12] across all evaluation metrics, which can be primarily attributed to the multimodal fusion of keypoints and depth values. Moreover, algorithms such as CNN and ViT extract features from all information in the entire image, which often includes a large amount of redundant data. In the comparative experiments, traditional methods employed feature sequences of length 512 as input, whereas the proposed method uses a much shorter sequence of length 21. Despite the reduced dimensionality, this sequence effectively captures the motion characteristics of the excavator, providing more precise and task-specific information. Consequently, the proposed method achieves higher recognition accuracy with fewer but more accurate features, demonstrating the effectiveness and efficiency of the multimodal 3D spatial representation.

5.5. The Test Results of the Application Scenarios

Examples of the test results on the test set are shown in

Figure 9. The proposed model is capable of accurately recognizing the categories of various actions, whereas the CNN + LSTM approach exhibits recognition errors across regular images, occluded images, and images corresponding to action transition segments.

The test set includes images with occlusions and action transition segments. For these occluded and action-transition images, the CNN + LSTM method tends to produce recognition errors. This is because CNN extracts features from the entire image. When occlusions occur, the extracted features contain excessive irrelevant information and insufficient effective information, making it difficult for the LSTM to accurately recognize the action. In contrast, the proposed method designs feature extraction based on the action characteristics of the excavator. Under occlusion, even if some skeletal keypoint information is blocked, the method can still determine the action category using the structured 3D spatial features of the remaining keypoints, thereby reducing misclassification. For images depicting action transition segments, their visual appearance often exhibits high similarity between consecutive frames. The CNN + LSTM method extract only 2D features without incorporating 3D spatial information, resulting in a high overlap of the extracted features and making it difficult for the LSTM to distinguish the specific action categories. In contrast, the 3D spatial information of the excavator’s skeleton keypoints can directly reflect the motion state in the images, allowing the model to capture features of action transitions more effectively. Consequently, the proposed method demonstrates more stable and robust classification performance across challenging scenarios.

In summary, the experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method outperforms traditional image feature-based approaches in terms of action recognition accuracy, feature utilization efficiency, and robustness under complex environments. It should be noted that all comparative methods were trained and tested on the same dataset under identical conditions, using the same training–testing splits and consistent experimental settings, thereby ensuring a fair and unbiased performance comparison. In addition, compared with image-based action recognition methods, the proposed method achieves a higher inference speed due to its lightweight skeletal representation. Specifically, our method runs at approximately 40 FPS, while under similar hardware conditions, due to the high computational cost of extracting convolutional features from high-resolution RGB frames, the running speed of image-based action recognition methods is usually below 25 FPS. By effectively leveraging structured 3D spatial features, the method enables more precise, stable, and reliable classification of excavator actions across diverse scenarios.

More importantly, the high-precision action recognition capability provides a solid foundation for practical applications in construction productivity analysis and work cycle monitoring. During excavator operations, a complete work cycle consists of consecutive actions such as digging, lifting, swinging, loading, and lowering. By accurately recognizing these actions, the number of work cycles and their durations can be recorded, enabling quantitative assessment of operational efficiency. Therefore, this study not only proposes a highly accurate excavator action recognition method but also provides a feasible and efficient technical approach for vision-based automated productivity evaluation of earthmoving operations.

To further demonstrate the practical applicability of the proposed excavator action recognition method, a preliminary analysis of excavator action durations and work cycles was conducted based on on-site video data collected from two construction scenarios, and the corresponding productivity was calculated, as illustrated in

Figure 10. The figure presents the durations of individual actions, the total cycle time, and the number of work cycles for different excavators operating under the two construction scenarios. For consistency, five complete work cycles were selected for analysis in each scenario. As shown in

Figure 10a, the total cycle time for Excavator 1 was 108.37 s, with the swinging phase accounting for the longest duration (36.26 s), followed by digging (32.84 s) and loading (19.25 s). The lifting and lowering actions were relatively shorter, at 10.28 s and 9.74 s, respectively. Based on five recorded cycles, the estimated productivity reached 166 cycles per hour. In contrast,

Figure 10b indicates that Excavator 2 exhibited a shorter total cycle time of 94.22 s. Here, swinging remained the most time-consuming action (34.35 s), but digging duration decreased to 26.42 s, and loading was reduced to 17.15 s. Lifting and lowering times were also lower, at 7.35 s and 8.95 s, respectively. The productivity of Excavator 2 was correspondingly higher, reaching 191 cycles per hour.

6. Conclusions

This study proposes an excavator action recognition method based on skeleton keypoints and a monocular depth estimation network. By leveraging the characteristics of excavators, the YOLOv8 Pose model and the DAM are used to obtain the 3D spatial feature sequences of the excavator’s skeleton keypoints, which are then input into an LSTM model for action recognition. The proposed method achieves a precision of 93.44%, a recall of 87.21%, an F1 score of 89.68%, and an accuracy of 91.43%, demonstrating strong detection performance. The experimental results indicate that fusing the 2D coordinates of skeleton keypoints with 3D depth information can accurately and comprehensively capture the action characteristics of the excavator. Compared with traditional image-based feature extraction methods, this approach provides higher precision and robustness, enabling more accurate action recognition using fewer features.

Moreover, in challenging scenarios such as occlusions and action transitions, the proposed method is still able to accurately recognize actions, demonstrating strong robustness in complex construction environments. The action recognition method proposed in this study enables efficient and stable action classification, providing a reliable technical approach for productivity assessment and operational analysis in construction sites.

The novelty of the proposed method is reflected on two aspects:

Action classification based on excavator motion characteristics: This study focuses on the skeletal keypoints of excavators to capture their specific motion patterns. Existing hybrid methods or skeleton-based approaches mainly rely on 2D global image features, which often suffer from spatial ambiguity. In contrast, the proposed method employs monocular depth estimation to construct a 3D spatial representation of skeletal keypoints, enabling a more accurate description of the excavator’s motion states. Furthermore, an LSTM network is used to model temporal relationships and learn the dynamic evolution of excavator actions, thereby achieving more robust and accurate action recognition in complex construction environments.

Efficient feature representation and reduced redundancy: Unlike traditional methods that extract global features from raw 2D images using algorithms such as CNN or ViT and subsequently feed them into temporal networks for classification, the proposed approach significantly reduces the interference from redundant information. By shortening the input feature sequence and focusing on task-relevant skeletal and depth features, the method provides a more precise representation of the excavator’s motion states, leading to improved recognition accuracy.

Overall, the excavator action recognition framework based on skeletal keypoints and a monocular depth estimation network not only addresses the ambiguities inherent in 2D image representations but also mitigates noise interference present in traditional image feature-based methods. This provides a reliable and robust solution for excavator action recognition in complex construction scenarios.

Based on the proposed excavator action recognition method, future studies can apply it in various practical scenarios. For instance, in excavator productivity assessment, the recognized action categories can be used to calculate the number of work cycles and the duration of each cycle. By analyzing the duration of individual actions, the transition times between consecutive actions, and the overall cycle frequency, it is possible to quantitatively evaluate and optimize the operational efficiency of excavators. Specifically, through timestamp annotation of consecutive action transitions, two key productivity metrics can be computed: (1) cycle time, representing the total duration of a complete work sequence, which can be further broken down into the time spent on each individual action stage; and (2) productivity, defined as the number of work cycles completed per unit time (e.g., cycles per hour). In the field of construction safety, excavator action recognition can be used to monitor abnormal or hazardous operations. For example, it can detect whether there are personnel or obstacles along the excavator’s swing path, or whether digging has been performed beyond the designated safe operating range. Overall, the proposed method not only improves action recognition accuracy but can also be integrated with specific application scenarios, providing technical support for construction efficiency optimization and safety assurance.

This study also has certain limitations:

Dataset scale and diversity: The scale and diversity of the dataset are insufficient. The dataset used in this study was self-collected, with a limited number of samples and diversity, and primarily focused on a single type of construction machinery, which to some extent restricts the generalization ability of the model.

Annotation requirements for keypoint detection: The keypoint detection component requires a substantial amount of annotation work. At present, it still relies on manual labeling, which is both labor-intensive and time-consuming.

Lack of real-time implementation: The current study remains at the theoretical stage, primarily based on the analysis of collected static data, and has not yet achieved real-time monitoring and analysis capabilities, which limits the immediate applicability of the method in live construction environments.

To address the aforementioned limitations, future research can focus on the following aspects:

Dataset expansion and diversification: By collecting data from different types of machinery and various application scenarios to supplement and expand the dataset, in order to enhance the model’s generalization capability and applicability, and reduce reliance on a single data source.

Reduction in annotation workload: Future research could explore semi-supervised learning approaches, using a small amount of labeled data to guide the learning from large-scale unlabeled data. This strategy would alleviate the labor-intensive and time-consuming nature of manual keypoint annotation.

Application to real-world scenarios: Future work can aim to implement the proposed method in practical construction environments, such as for productivity assessment and operational analysis. By integrating the algorithmic framework into on-site monitoring systems, it would be possible to achieve real-time detection and analysis of excavator actions.