Abstract

Analyzing how urban ritual spaces transform into everyday living environments is crucial for understanding the spatial structure of contemporary historical districts, particularly in the context of ancestral temples. However, existing research often neglects the integration of both building-level and block-level perspectives when examining such spatial transitions. Grounded in urban morphological principles, we identify the fundamental spatial units of ancestral temples and their surrounding blocks across the early 20th century and the post-1970s era. Using the topological characteristics of an access structure, we construct corresponding network graphs. We then employ embeddedness and conductance metrics to quantify each temple’s changing position within the broader block structure. Moreover, we apply community detection to uncover the structural evolution of clusters in blocks over time. Our findings reveal that, as institutional and cultural factors drive spatial change, ancestral temples exhibit decreased internal cohesion and increased external connectivity. At the block scale, changes in community structure demonstrate how neighborhood clusters transition from a limited number of building-based clusters to everyday living-oriented spatial clusters. These insights highlight the interplay between everyday life demands, land–housing policies, and inherited cultural norms, offering a comprehensive perspective on the secularization of sacred architecture. The framework proposed here not only deepens our understanding of the spatial transformation process but also provides valuable insights for sustainable urban renewal and heritage preservation.

1. Introduction

Analyzing urban spatial transformation requires examining not only physical changes but also social practices []. An everyday life perspective facilitates a deeper understanding of urban spatial evolution, which has become widely recognized in urban studies [,]. This observation also accords with Lefebvre’s production of space, which treats spatial evolution as a social process rather than a purely physical one []. Such a viewpoint highlights how individuals’ daily practices, along with institutional and cultural contexts, jointly shape spatial transformations [], thereby informing more rational and sustainable urban renewal strategies. Complex historical urban districts in China offer exemplary cases for such analysis, where daily life activities have progressively shaped residential patterns. In these complex historical districts, urban ancestral temples (‘citang’) served as central ritual spaces that played a vital role in traditional social organization and spatial governance. In recent transformations of such districts, these temples have transitioned from sacred spaces into everyday living environments, providing critical case examples for analyzing spatial change from an everyday life perspective. Further investigation not only enriches the understanding of residential morphological changes but also offers valuable insights for analyzing similar complex historical districts in the Global South [].

Current studies on the everyday appropriation of sacred and ritual spaces mainly focus on cultural and social transformations [], with particular attention to the declining influence of religion. Spatial research, however, often centers on church secularization and its relationship to public space. Chinese ancestral temples share similarities with Western sacred spaces in structuring daily life and residential functions, so examining the usage and rationale of sacred spaces lays some groundwork for analyzing transformations in Chinese temples. Nonetheless, urban ancestral temples in China function not only as sacred sites but also, more importantly, as ritual spaces—long regarded as integral to everyday life in traditional Chinese society [,]. Unlike churches, ancestral temples in China experienced drastic shifts through secularization, ultimately being reconfigured into residential living spaces. The shifts in ritual spaces largely coincide with newly arrived residents, who carved out private rooms and corridors within the temples, often encroaching upon or dismantling the original ceremonial halls, thereby creating a multi-household everyday living space (Figure 1). Over time, extensive modifications altered circulation, structural components, and internal layouts, which significantly shaped the spatial transformation. Rather than functioning solely as clan-based properties, many of these buildings now accommodate both private residences and shared communal facilities.

Figure 1.

Transformation from an ancestral temple to an everyday living space. Zeng Jing-yi’s (1829–1862) Temple, located in Nanjing. (a) An aerial photograph from the 1920s shows the temple’s spatial layout—with a gate house, a pleasure hall, and a rest hall; (b) the current condition of the ceremonial hall; (c) the utilization of shared spaces following the temple’s conversion into a living space.

In this study, we go beyond traditional research that focuses on the historical and cultural significance of ancestral temples or on preservation efforts and instead emphasize the dynamic spatial processes closely tied to everyday life and social organization. We examine the fundamental elements of everyday living spaces and further analyze how these temples shift in position within urban spatial networks while exploring the multiple forces that drive their transformation into common living environments. Accordingly, this research seeks to answer the following questions: What are the fundamental spatial elements of ancestral temples in different historical periods, and how do they change over time? What is the spatial relationship between ancestral temples and their surrounding neighborhoods, and how has it changed across different historical periods? Moreover, what are the overall spatial characteristics of the block in which the temple is situated, and how do these characteristics differ across various historical periods? What implications does this transformation hold for understanding spatial evolution and advancing sustainable urban renewal in complex historic districts?

To clearly address these unresolved issues, we identify specific research gaps and articulate corresponding hypotheses. First, the extant studies of ancestral temples concentrate predominantly on their historical and cultural significance but lack fine-grained, spatially explicit analyses of temple layouts. Second, no systematic characterization exists on how temple spatial configurations evolve in the shift from sacred ritual to residential function. Finally, few works unpack the multiple socio-spatial drivers that underlie these transformations. We mainly test two hypotheses in this research: (1) As ancestral temples become residential spaces, their connectivity to the surrounding urban fabric increases while their internal cohesion declines, driving a shift from a clear axial arrangement toward a more fragmented spatial pattern. (2) Changes in everyday living patterns—when coupled with land use and housing policy reforms—alter the structure of space use, such that periods of regulatory relaxation or intensified external pressures accelerate the domestication of temple spaces.

Our study employs graph theory as the primary analytical tool. By identifying the key structural elements of ancestral temple spaces and its surrounding block across different eras and building edges among them using spatial topology, we then derive a block-scale spatial graph based on fundamental units, with the ancestral temple represented as a subgraph. We then examine quantitative variations between subgraphs and block graphs, thereby capturing micro-level structural shifts that illuminate the temple’s changing role in overall urban configurations. We also apply a Louvain-based community detection approach to cluster the overall spatial relationships within the temple’s neighborhood, thereby revealing shifts in its structure.

The major contributions of this research are as follows:

- This study develops a method for constructing block-scale spatial network graphs—based on fundamental functional units—across multiple historical periods, thereby reflecting changes in everyday living patterns and effectively analyzing transformations in complex residential structures.

- By examining how changes in the subgraph–graph relationship shaped ancestral temples’ transition into everyday living spaces—and integrating community detection to reveal shifts in block-level spatial clusters—this study investigates the multiple factors that influence these transformations, thus uncovering the complex interplay between spatial configuration and social dynamics.

- The findings provide valuable insights for sustainable heritage preservation and community-driven urban renewal strategies in Chinese historic districts.

The remainder of this paper is as follows. Section 2 reviews the existing literature on ancestral temples and everyday life. Section 3 outlines the analytical framework employed in this study, while Section 4 presents a comparative case study. Section 5 discusses these findings and concludes with broader implications for urban renewal strategies.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sacred Spaces in Transition

2.1.1. Defining Sacred Space

Research on distinguishing between secular space and sacred space has a long tradition. Many scholars focus on whether sacred spaces should be viewed as public spaces [,], which is highly relevant for understanding how secular spaces are constituted. More crucial, however, is the role of sacred space in organizing residential and everyday living environments. In historical studies, the examination of sacred spaces has steadily expanded to include their impact on everyday life, reflecting an emerging perspective that underscores the structural unity of sacred and secular spaces. In other words, when sacred spaces function in their organizational capacity—as historical spaces or familial hubs—they essentially shape everyday life []. Sacred space materializes through ritual and social acts, reinforcing a sense of religious belonging while structuring daily routines []. In certain contexts, even ordinary family life can become a form of religious practice [], mirroring the role of ancestral temples in shaping daily life in traditional Chinese society. Analyzing sacred space within an urban system of everyday life offers a more comprehensive view of its dynamic evolution and the complex frictions within the broader urban ecosystem []. This implies that sacred space is closely entwined with its surrounding social system; when everyday life and social structures undergo drastic change, sacred space transforms accordingly. Some studies indicate that sacred space may disintegrate as social systems evolve []. Moreover, because sacred space helps organize everyday life, it becomes deeply embedded in local culture and identity []. Thus, examining the characteristics and transitions of sacred space is tantamount to analyzing the everyday fabric of its surrounding area. This process of spatial transformation can be categorized into seven types based on cultural and geographical distinctions, showing that the patterns of secularization in Europe differ from those in Confucian contexts such as China and Vietnam [].

In the Confucian context of China, while ancestral temples share some architectural similarities with ordinary dwellings, they differ significantly in terms of circulation and function, often incorporating elaborate ritual features and spatial layouts []. Serving as fundamental components of both urban and rural daily life, these temples were typically built to honor distinguished figures or ancestors. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, many lineages constructed symbolic ancestral temples as communal properties to worship common ancestors and hold major clan activities []. As a result, ancestral temples became integral to social governance, lineage cohesion, and cultural identity. Early research on their role in Chinese urban spaces and everyday life highlights these temples as political and administrative tools in traditional society, where ancestor worship facilitated governance []. Such functional attributes also illustrate the temple’s significance as a ritual space that contributed to spatial governance []. Other studies emphasize their integrative role in traditional culture, suggesting that ancestral temples, as markers of communal identity, helped forge collective cultural consciousness by reinforcing kinship ties and shared memories [,]. At the same time, it is widely recognized that ancestral temples function as spiritual and cultural cores in daily life []. Positioned at the center of spiritual life in traditional Chinese society, ancestral temples shaped both spatial organization and social structures.

Most existing studies have predominantly focused on the cultural and social significance of sacred spaces, whereas research on urban sacred space and its spatial relationship with the urban block at more micro-spatial scales remains limited. Our study aims to establish a more fine-grained analytical framework that emphasizes the micro-scale spatial dynamics of sacred spaces during their transformation into everyday living environments.

2.1.2. Transition to Everyday Use

As traditional social structures faded and land–housing reforms accelerated during the mid-20th century, these once exclusive ritual spaces were gradually subdivided and repurposed for multi-household living []. This transformation has often been interpreted as a secularization of sacred domains, thus attracting increasing scholarly attention []. Ancestral temples do not simply reflect a one-dimensional move toward secularization; rather, their evolution can be regarded as a pragmatic shift in functional uses, continually reshaping spatial production for everyday living []. Habraken’s “Supports” theory highlights the adaptability of built environments and the active role of occupants in configuring space []. This spatial and functional shift therefore resonates with Lefebvre’s notion of space as socially produced through everyday practices, representations, and lived experiences []. This transformation can also be analyzed as part of a broader social network [], not as an isolated phenomenon. Spatial change, moreover, is tightly intertwined with the habitus of individual actors and social struggles []. By connecting these changes to everyday life and local governance, scholars can better understand how ritual spaces become embedded in everyday spatial routines. Such shifts reflect the broader socioeconomic changes reshaping Chinese urban environments after the 1950s [].

Through continuous adaptation and reconfiguration, various elements—including institutional governance, community management, residents’ lifestyles, cultural norms, and social networks—have been identified as drivers of spatial change, underscoring the interplay of multiple factors []. First, cultural dimensions play a critical role in such spatial transformations. Studies indicate that such changes are influenced by regional cultures [,] because sacred space is inseparably tied to the social and spatial structures of its locale [,]. Clearly, this transformative process develops alongside changes in local daily lifestyles. Therefore, to analyze how sacred spaces transform and to understand their structural characteristics, it is essential to concentrate on everyday life and cultural contexts. This viewpoint provides an important theoretical basis for developing an analytical framework grounded in the fundamental units of daily life. Meanwhile, from an institutional and governance perspective, existing studies often interpret alterations in these composite spaces by examining urban governance and economic systems [,,]. Across many parts of the Global South, the transition from a standardized, singular temple space to a more complex form of common living is shaped by political regulation [] and is closely linked to state administrative systems []. Shifts in institutional arrangements thus provide valuable insights into these spatial reconfigurations. At the same time, ongoing acts of spatial modification and occupation frequently arise from individual interpretations of the built environment []. Indeed, the secularization of ritual spaces typically emerges alongside fundamental changes in lifestyles []. Hence, the evolution of complex residential structures should not be dismissed as unlawful encroachment but rather understood as a spatial transformation aligned with residents’ living patterns []. Changes in the built environment signal an evolution in the modes of dwelling; in turn, social networks emerge in close synergy with the shaping of living environments [].

Existing studies have provided a general analysis of the social structure and spatial functions of ancestral temples. However, the household-scale characteristics of spatial transformations and the underlying complex causes have yet to be clearly articulated. The shift in functional spaces toward collective living demands more explicit theoretical frameworks for explanation and interpretation.

In response to these complexities, we established the methodological foundations in the next section for examining ancestral temples’ transition at a micro-spatial scale.

2.2. Methodological Foundations

2.2.1. Morphological Principles

This study’s analysis of ancestral temples and urban spatial evolution involves research on urban morphology. Through morphological approaches, one can quantify the secularization of ritual spaces and offer detailed, precise accounts of their transformation characteristics. Traditional tools for examining spatial change still rely primarily on historico-geographical or process-typological approaches [,], which provide useful insights into fundamental shifts in spatial form. Building upon this foundation, existing studies employ various spatial tools—including classification and machine-learning methods—to analyze urban spatial structures at the building level [,] or infer the morphology of urban building spaces from plot or land unit ownership records [,,]. Such morphological methods, drawing on a range of data sources and perspectives, have established a solid foundation for interpreting urban spatial structures. However, to capture how everyday life actively shapes the city, it is necessary to examine fundamental living-oriented configurations within urban space. In morphological studies, some research already explores this dimension by focusing on small-scale spatial features and structures [,]. Building on these efforts, analyzing ancestral temples as they transition into common living environments calls for identifying the basic spatial elements closer to everyday life. In this regard, the concept of land de facto provides an essential basis for analyzing complex spaces and their evolution [], as it reveals the actual functional units of space. We propose further examining these fundamental units of daily life, thereby illustrating how the transition from ritual spaces to common living spaces is structurally manifested.

2.2.2. Graph Theory

After defining the basic spatial units of ancestral temples for different historical periods, we seek to investigate how these temples evolve within the broader urban structure. Graph theory, with its emphasis on relational structures, offers a valuable analytical tool []. Early approaches such as space syntax have already demonstrated how spatial configurations can be abstracted into structural relationships [,], laying a robust foundation for applying graph-based techniques in spatial studies. By modeling spatial connectivity, urban space can be regarded as a network, enabling a closer observation and measurement of its transformational processes [,] and revealing overall structural characteristics. In studies of spatial change rooted in everyday life, space syntax can be further extended by representing the smallest fundamental spatial units and constructing relationships among them via spatial or syntactic distance []. Compared with conventional morphological approaches, a graph-based method captures quantitative, system-wide properties of spatial structure. By modeling pairwise relationships among basic units, it reconstructs the global configuration from the bottom up—a capacity that is particularly valuable in high-density residential settings, where a network representation enriches the underlying data structure. Integrating the tree-like hierarchies of classical urban morphology with a full network topology therefore offers a more objective lens through which to reveal complex spatial patterns. Once constructed based on these basic units, such a graph enables standard indicators to reflect both overall and localized structural attributes. For instance, betweenness centrality can reveal each temple’s units within the larger spatial framework []. Changes in the structure of the block-scale graph reflect alterations in the broader spatial configuration of the neighborhood surrounding the ancestral temple. Moreover, treating the ancestral temple as a connected subgraph embedded in the wider neighborhood network allows metrics such as embeddedness to trace shifts in its positionality—an analytical advantage that stems directly from the graph representation.

In recent years, graph theory has increasingly been applied to micro-scale analyses of spatial form and its evolution []. Typically, however, such graph-based analysis is oriented toward building-centric perspectives []. When investigating the transformation of everyday common living spaces within former ritual environments, it becomes necessary to adopt an approach centered on the inhabitants’ viewpoint. Constructing graphs at the scale of individual residents may illuminate their social connections, along with the institutional influences they experience. In turn, graph-structured data can be used to parse the relationships and causal factors underlying spatial change []. However, this approach requires further refinement when applied to micro-scale analyses of everyday spatial transformations. This study thus proposes establishing resident-scale graphs to analyze the evolving spatial characteristics of ancestral temples and unravel the multiple forces at play behind these transformations.

3. Methodology

3.1. Method Architecture

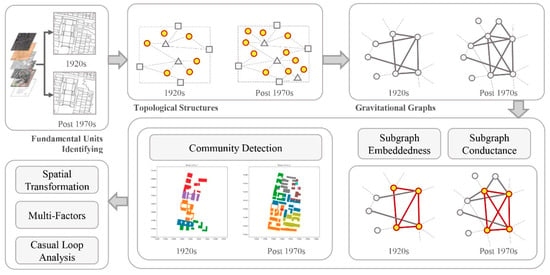

This study develops an analytical framework to investigate how ritual spaces transition into everyday living environments. As illustrated in Figure 2, unlike conventional analytical methods, we address spatial transformation by focusing on the relationship between ancestral temples and the surrounding urban context.

Figure 2.

Method architecture.

- Identifying the fundamental spatial units: Based on each historical period’s functional usage, we determine the minimal functional spaces of ancestral temples and their surrounding neighborhoods and then use topological relationships to represent the spatial network among these units. Details are provided in Section 3.2.

- Building graphs: By examining connections across different spatial layers, we link all minimal spatial units within the block that contains the ancestral temple, ultimately generating a gravitational graph of these units to quantify micro-scale spatial structures. Details are given in Section 3.3.

- Analyzing block-level clustering: Drawing on the gravitational graph, we investigate the clustered spatial structure of the block. In combination with the relationship between the subgraph (temple) and the overall graph (block), we explore how the temple’s spatial relationship with its neighborhood has changed over time. Details can be found in Section 3.3 and Section 3.4.

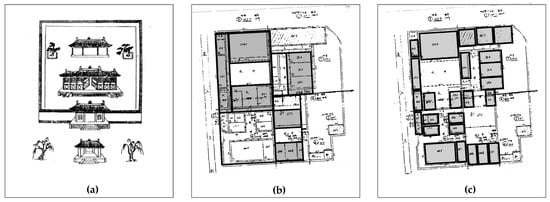

3.2. Fundamental Unit and Its Adjacency

During different historical periods, ancestral temples exhibit distinct spatial organizational characteristics. In traditional society, ancestral temples typically adhered to standard building codes for ancestral temples as outlined in The Ming Rites Collection, which requires a central axis that includes a gate house, a pleasure hall, and a rest hall, aligning with traditional social protocols and filial reverence (Figure 3a). At this stage, each building served as a node in the temple’s spatial network, functioning as the smallest unit for spatial organization and operating as an independent functional space. Following the collapse of traditional society, the spatial configuration of ancestral temples in contemporary times underwent significant changes, with daily living and functional usage emerging as the fundamental basis of space. Under this transformation, households delineated tenure de facto, such that each household’s occupied space became the primary node of the temple’s spatial network (Figure 3b,c). Each household, driven by its own living and social needs, constituted a distinct minimal unit within the temple’s spatial layout. Publicly and privately owned rooms coexisted, and each household’s spatial unit went beyond the confines of traditional plots or property boundaries, not necessarily coinciding with the original architectural divisions. Across these two periods, the fundamental spatial units transitioned from being defined primarily by architectural function to reflecting everyday living needs, thus evolving from a clearly ordered layout into a more complex coexistence. This shift captures how ancestral temples were used differently at various stages of history.

Figure 3.

The functional units of ancestral temples across different historical periods. (a) The Ming Rites Collection (written in the 1370s) codified the architectural layout of ancestral temples into standardized functional components. (b) The reconstructed layout of Tao-Lin’s Temple derived from a rental contract for public housing, illustrating the spatial configuration of functional units in the 1920s. (c) The distribution of basic functional units (households) extracted from the same rental contract, reflecting the spatial arrangement after the 1970s.

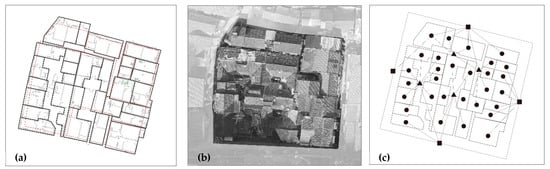

Building upon this definition of nodes, we can further consider the relationships among them to reflect the overall network properties of the urban space. In space syntax, connections between spatial units are determined by access relationships. Following this principle, we draw on the area structure approach [] to divide the block containing the ancestral temple into distinct spatial layers and establish their interconnections. We define three levels of space: (1) spaces occupied by households (in the contemporary era) or individual functional units (in the traditional era); (2) jointly held or shared spaces accessible to a subset of Level (1); and (3) public spaces that remain accessible at all times. All three levels are distinguished solely on the basis of spatial connectivity. Within these three layers, individual functional units and shared spaces are each represented as centroids (nodes), whereas city-scale public spaces are modeled using a dual-representation approach. Doors, corridors, or other direct connecting passages among these layers serve as potential access links (Figure 4). Using this method, we can represent the overall spatial configuration of both the temple and its surrounding block across different eras. From this layered structural map, we derive the topological distances that each fundamental unit must traverse to reach any other. The number of layers thus reflects the spatial relationships among these units at different historical periods, providing the foundation for building adjacency graphs and carrying out subsequent subgraph calculations.

Figure 4.

Spatial structure representation via the access structure. Within the block, we distinguish (1) individual functional units, (2) jointly held or shared spaces, and (3) public areas based on spatial and functional relationships. Their interconnections depend on whether these areas can directly reach one another. (a) illustrates the division of individual spaces in the example block; (b) presents an aerial photograph of the block; and (c) shows the resulting connectivity across these spatial layers. In the diagram, the public space layer is denoted by ■, shared spaces by ▲, and individual functional units by ●.

Here, spatial connectivity is employed solely as an analytical construct. We recognize that an excessively high level of connectivity can generate unintended side-effects, including security vulnerabilities and traffic congestion.

3.3. Graph Construction

Having defined each node and its interconnections, we can now represent the overall adjacency relations in the block where the ancestral temple is located. The proximity between nodes is determined by their topological distance, namely the cumulative number of spatial layers separating them. For instance, if the topological distance between two nodes is 1, they can connect directly, indicating a closer relationship. A distance of 3 implies that two intermediate layers must be traversed, suggesting a more distant relationship. Here, we adopt a gravitational approach [] to quantify the strength of connections between nodes, using a squared-inverse formula:

where denotes the strength of connection between nodes and . The constant is a scaling parameter, and (or ) represents the “mass” of each node, here calculated by its spatial footprint. is the number of path segments (or topological distances) required to move from node to node . Squaring moderates the influence of distance, aligning with real-world conditions. Consequently, we can construct a fully connected weighted adjacency graph to represent the gravitational relationships among all nodes in the block. We employ this spatial gravitational model because, compared to a rapidly decaying exponential or derivative-based function, it more smoothly reflects variations in topological distance among nodes. From this point, each node’s position within the graph can be calculated using complex network techniques.

However, to analyze the temple’s role within the urban spatial network, we must examine how the temple’s subgraph relates to the overall block graph. In this graph, we categorize nodes into two groups: those within the spatial boundary of the ancestral temple and those in the rest of the block. Likewise, relationships among nodes fall into three types: connections among temple-internal nodes, connections among non-temple nodes, and connections between temple nodes and non-temple nodes. To evaluate the temple’s status within the urban fabric, we focus primarily on changes in adjacency relationships between temple nodes and external nodes. We introduce the concepts of embeddedness and conductance to capture the subgraph’s position in the urban network and the extent of its external linkages. The graph-based model thus extends, rather than replaces, traditional morphological analysis. At the block scale, the graph records structural change by tracking the evolution of internal relationships; the temple’s transformation is read not as the relocation of a single architectural sequence but as one component of block-level reconfiguration. Graph metrics enable this study to transcend fixed scales, descriptive indices, and linear linkages, advancing a structure–quantification hybrid paradigm in which measurable patterns ground subsequent interpretive claims.

3.3.1. Subgraph Embeddedness

We employ embeddedness to quantify the degree to which a subgraph is integrated within the block graph. Although embeddedness is commonly calculated for individual nodes, here, we measure the strength of connections both among nodes within the subgraph and between subgraph nodes and external nodes, then take the ratio of these values [,]. From this perspective, a larger subgraph embeddedness value indicates that most of its connections occur internally, whereas a smaller value signifies that most connections involve external nodes. We calculate subgraph embeddedness with the following formula:

Here, is the sum of edge weights among nodes in subgraph , reflecting internal connectivity. For each node , is the total weight of edges linking to all other nodes; thus, captures the total connectivity of all nodes, encompassing both internal links and external connections. A larger subgraph embeddedness value indicates that the subgraph remains more independent, while a higher degree of external linkage leads to a smaller value.

3.3.2. Subgraph Conductance

Similarly, we use conductance to assess how permeable the subgraph’s boundary is with respect to the entire block graph []. By computing the minimal set of edges whose removal would sever links between the subgraph and its complement, we capture the subgraph’s external connectivity. We then compare that set of edges to either the subgraph or its complement, revealing whether the subgraph’s boundary is sparse—meaning that the subgraph is internally cohesive and relatively isolated from the outside. A higher conductance value implies a larger number of external edges, indicating that the subgraph is less autonomous and more readily integrates with the overall network. We compute conductance as follows:

Here, Equation (3) defines the subgraph conductance, where sums the edge weights between nodes in and those in its complement , reflecting the subgraph’s external connections. Meanwhile, takes the smaller of two volumes: one is , i.e., the total connectivity (sum of edge weights) for all nodes in ; the other is , representing the connectivity volume of the complement. The goal of computing is to normalize the subgraph’s external connections, so the resulting measure lies between 0 and 1. A value near 0 suggests few external links and a tightly knit subgraph, while a higher value indicates robust connections to the overall network.

Subgraph embeddedness measures the proportion of internal edge weights relative to the subgraph’s total, while subgraph conductance reflects the ratio of edge weights that must be removed to sever external connections, compared to the subgraph’s complement’s volume. High embeddedness and low conductance typically indicate a closely interconnected subgraph with limited external ties, while the opposite suggests that it is merely a local part of the network without clear community traits. Comparing these two values reveals how the temple subgraph’s isolation or connectivity evolves, whether during its ritual use or after transitioning to a common living space. These numeric shifts highlight the spatial transformation trends across two representative historical periods.

3.4. Community Structure

Beyond the foregoing analysis, we also need to examine the overall spatial structure of the urban block containing the ancestral temple. By comparing the block’s clustering patterns in two representative time periods, we can integrate subgraph characteristics to reveal shifts in the temple’s relationship with the surrounding urban space. Here, we conduct community detection for the block’s nodes across two time periods. Using the Louvain algorithm [] and gravitational relationships among nodes, we identify the block’s community structure. In other words, the block’s spatial gravitational network is partitioned into tightly interconnected clusters, in which nodes within the same cluster have stronger internal linkages, while ties between different clusters are comparatively weak.

For clustering in historic districts, the algorithm searches for the partition that maximizes the sum of intra-cluster edge weights, thus unveiling the block’s spatial structure across different historical epochs. In Equation (4), is the weight of the edge between nodes and ; is the weighted degree of node . The indicator function equals 1 if nodes and belong to the same community and 0 otherwise. The term is defined as , that is, half of the total edge weight in the network. Under the Louvain algorithm, the gravitational weights among block units are integrated into . Nodes that are topologically closer and exhibit stronger gravitational ties are thus more likely to be grouped into the same cluster.

Within the block graph constructed from the minimal functional spatial units, edges are determined by the gravitational model. The resulting clusters illustrate how these units interrelate. Comparing clustering outcomes at different historical periods reveals shifts in the block’s relational structure. By mapping these clusters onto physical geographic space, we can observe changes in the spatial organization of the block housing the ancestral temple. In access structure-based graphs, the resulting communities reflect accessibility distance between nodes. Unlike geometric distance, accessibility distance captures the relative ease of mutual reach, rendering the derived clusters more meaningful for real-world interpretation. In turn, by integrating the temple’s embeddedness and conductance as a subgraph, we can more clearly illuminate how the temple evolved from a ritual space into an everyday living environment.

4. Case Study

4.1. Case Description

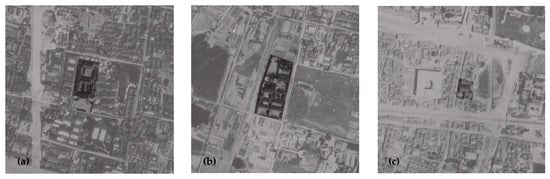

We selected three particularly representative types of temples—Zeng’s Temple, Li’s Temple, and Tao-Lin’s Temple—and their surrounding blocks in Nanjing, China, as a case study (Table 1). We selected ancestral temples in Nanjing for analysis because the city still preserves relatively intact temple compounds whose patterns of spatial change are broadly representative. Zeng’s Temple (Figure 5a) was built by the Zeng family to commemorate their ancestor Zeng Guoquan (1824–1890). Zeng’s Temple is a large-scale, single-axis ancestral complex. In addition to its main buildings for ritual and ceremonial functions along the central axis, it also features residential quarters on both sides for caretakers. Li’s Temple was built by the Li family to commemorate their ancestor Li Hongzhang (1823–1901). It is a typical dual-axis ancestral complex (Figure 5b). While retaining the primary axial ceremonial buildings, the two side wings were simplified, and on an additional axis, a large lotus pond and garden were constructed. Both of these large-scale temples were built primarily for familial ceremonies and ancestral worship, whereas Tao-Lin’s Temple was officially constructed by the Qing government, dedicated to Tao Shu (1779–1839) and Lin Zexu (1785–1850). Its purpose was to establish moral and patriotic exemplars, highlighting another dimension of ancestral temples—namely, educating contemporaries through the veneration of historical figures. Tao-Lin’s Temple is also a typical dual-axis complex, though smaller in scale than Li’s Temple (Figure 5c). These three temples not only represent different spatial configurations and functional patterns but also share a common trait: each is situated within a densely populated urban environment.

Table 1.

Key dimensions of each temple.

Figure 5.

Aerial views (1920s) of Zeng’s Temple (a), Li’s Temple (b), and Tao-Lin’s Temple (c). Zeng’s Temple features a single-axis design, whereas Li’s and Tao-Lin’s temples adopt dual-axis layouts. By this time, all three temples were situated in densely populated urban neighborhoods.

We utilize aerial photographs and cadastral maps to digitize ancestral temples and their surrounding neighborhoods (data were obtained from the School of Geography, Nanjing Normal University). These source materials allow us to extract building footprints, as well as the outlines of nearby streets and alleyways, and particular attention is paid to scaling and georeferencing. We align the historical maps with on-site survey measurements to maximize the usability of their spatial information. Once digitized, we record the temple’s location, footprint, and structural characteristics, along with changes in the surrounding street layout. We also obtain land parcel boundaries and area measurements, creating a comparative baseline that spans multiple eras. These data illuminate how ancestral temples and their urban contexts have evolved, revealing the original spatial and societal functions of the building. In the digitized plans for two different historical periods, buildings belonging to each temple were outlined in red (Figure 6). From changes in the building footprints, it appears that Zeng’s Temple has undergone no major structural modifications: its spatial sequence and overall layout remain largely recognizable. In contrast, Li’s Temple shows considerable change. Alongside the emergence of many small-scale buildings surrounding it, the formerly ceremonial courtyard space inside the temple has been subdivided by several new structures of varying sizes and orientations. Tao-Lin’s Temple underwent even more drastic changes at the block level. A pond located to the right of the original block was filled in, leading to extensive new construction and the subsequent merging of this area with the temple’s plot into a single block. Li’s Temple likewise added numerous new buildings to its formerly open courtyard space. Examining these developments in tandem with the fundamental functional units reveals two overarching trends: first, the original ceremonial axis was rapidly dismantled, undermining the ritual spatial order and resulting in a more dispersed configuration; second, building density increased, with smaller, fragmented structures multiplying, ultimately blurring any clear distinction between the temple and its adjacent urban fabric.

Figure 6.

Architectural changes in the three temples and their neighborhoods from the 1920s to the 1970s. (a1,a2) Zeng’s Temple underwent minor alterations; (b1,b2) Li’s Temple saw major demolitions and reconstruction; (c1,c2) Tao-Lin’s Temple also experienced significant infill on former open land.

4.2. Graph and Subgraph

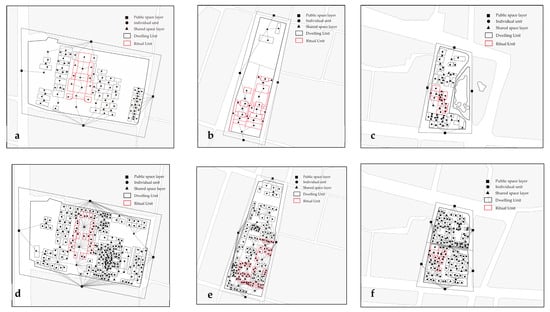

4.2.1. Constructing Graph

Building on the analysis in Section 3.2 of each temple’s fundamental spatial units and those of its surrounding block across different periods, we can construct a block-level spatial topology by examining access relationships. The network of units belonging to the temple, along with their interconnections, forms a subgraph within the larger block graph (Figure 7). From shifts in both the block-level graph and the temple subgraph, it becomes clear that further subdividing the temples into more complex spatial units does not necessarily cause dramatic spatial changes. Instead, adjustments in the relationship between the temple’s internal units and external nodes—or the balance between internal and external linkages—prove decisive for structural transformation. This rationale underpins our use of embeddedness and conductance as key indicators of each temple’s evolving position in the urban fabric. When converting the spatial topology into a gravitational network, we conducted multiple trials, ultimately setting the gravitational constant to 10 and using each unit’s area as its node mass. This approach yielded the overall gravitational relationships for the block. Because subgraph embeddedness, subgraph conductance, and community detection calculation are ratio-based, the scaling constant k cancels out algebraically; setting k = 10 serves only computational convenience.

Figure 7.

Spatial topological graphs of the three temple blocks. Sub-figures (a–c) display Zeng’s, Li’s, and Tao-Lin’s temples in the 1920s, while (d–f) show the same sites in the 1970s. The denser and more extensive edge webs in (d–f) indicate that spatial structure became markedly more complex over time.

4.2.2. Subgraph Analysis

By constructing fully connected weighted graphs for different time periods, we calculated the subgraph embeddedness and subgraph conductance for each stage (Table 2). All three temples—following changes in function and usage—display a decrease in subgraph embeddedness and an increase in subgraph conductance. Among these, the average decrease in subgraph embeddedness reached 51.3%, indicating a substantial reduction in the subgraph’s internal cohesion. This shift in embeddedness appears only marginally related to the number of residents in the surrounding neighborhood, suggesting a broader shared trend. Subgraph conductance rose across all three temples by an average of roughly 78%. In Zeng’s Temple (+158%), policy-led insertions introduced new openings toward adjacent lanes, replacing the former enclosed boundary and generating the largest conductance increase, even though daily activity remained focused on the main courtyard. In Li’s Temple (+14%), the historical dual-axis layout was largely retained; incremental infill along shared walls and covered corridors directed circulation inward, resulting in limited additional external flow and only a small conductance rise. In Tao-Lin’s Temple (+62%), the semi-open courtyard was extended outward, allowing several central nodes to integrate with peripheral clusters and producing a moderate conductance gain. These observations indicate that conductance is more sensitive to the location of new connections than to the number of added units: interventions that create direct external openings maximize conductance growth, inward-facing densification has a minimal impact, and controlled outward extension yields intermediate results.

Table 2.

Subgraph embeddedness and conductance metrics for each temple.

When ritual spaces are converted into living spaces, the increase in subgraph conductance varies considerably among different cases. Zeng’s Temple undergoes the largest change: from a spatial standpoint, numerous interior units emerge that have direct access to external areas, causing a dramatic rise in conductance from a low value to a much higher one. Li’s Temple exhibits the smallest change, indicating that, despite a shift toward more outward connections, the transformation was not particularly radical. By contrast, Tao-Lin’s Temple—initially never entirely isolated and already maintaining certain links with the outside—also sees a substantial increase in conductance, ultimately reaching the highest value. This underscores the temple’s notably enhanced connectivity with its surroundings.

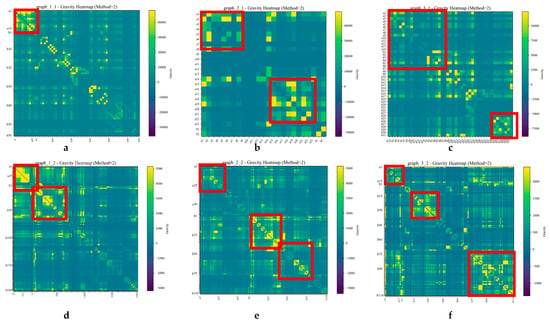

On the other hand, the overall spatial condition becomes relatively more disordered and dispersed. For instance, in the case of Zeng’s Temple, the neighborhood transitions from a relatively cohesive cluster to a scenario in which the temple-centered cluster is dissolved, although certain clustered features remain visible in the adjacent community (see Figure 8a,d). Paired heatmaps suggest that, even amid the seeming complexity of the neighborhood’s spatial relationships, identifiable pockets of clustering persist. From the perspective of resident interactions, this indicates that the transformed space exhibits the characteristics of common living, as neighbors form closely knit subgroups in their everyday relationships.

Figure 8.

Paired gravity heatmaps illustrating node-to-node attraction values. Panels (a–c) correspond to Zeng’s, Li’s, and Tao-Lin’s temples in the 1920s and panels (d–f) to the 1970s. Both axes list basic spatial units; colors range from blue (weak) to yellow (strong). Red rectangles highlight representative clusters. A higher proportion of yellow in (d–f) reveals more numerous and stronger inter-unit ties in the later period.

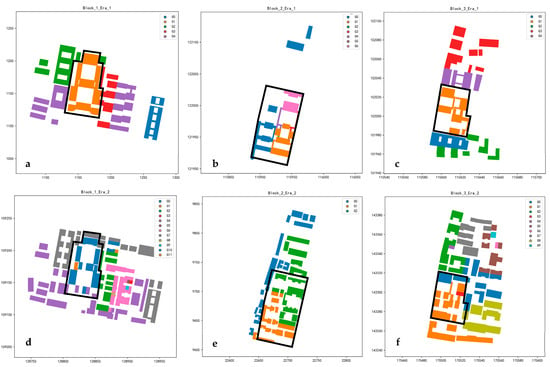

4.3. Spatial Structures of Blocks

Meanwhile, the Louvain-based community detection of the block further confirms our observations (see Figure 9). In Zeng’s Temple, external access remains confined to its original entrances, so the internal spatial structure largely retains its previous coherence, forming a relatively intact cluster. However, the units at the entrance differ from their earlier arrangement: due to changing usage patterns, the households near the entrance establish stronger spatial ties with adjacent buildings than with the temple’s internal residents, thereby merging into an external cluster. Li’s Temple exhibits the most significant spatial transformation. Initially, its dual-axis layout featured distinct clusters for ceremonial functions, residential areas, and leisure spaces—mirroring its original purpose. Yet, as numerous residential buildings were inserted and parts of the original structure were demolished, the temple’s clusters vanished, replaced by more noticeable internal–external groupings. The original ceremonial clusters effectively disintegrated. As for Tao-Lin’s Temple, changes in its entrance location caused newly arrived users to merge into a single, larger, and somewhat looser cluster. Moreover, because the occupants of the temple’s innermost buildings share close spatial ties with surrounding structures, they form part of a cluster that extends beyond the original boundaries of the temple complex.

Figure 9.

Plan-view spatial clustering patterns of each temple block. Sub-figures (a–c) represent the 1920s and (d–f) the 1970s for Zeng’s, Li’s, and Tao-Lin’s temples, respectively. Colors denote cluster IDs, and a black outline marks the ritual compound. By the 1970s (d–f), clusters inside the compound appear looser, and mixed groups spanning the temple boundary become more frequent.

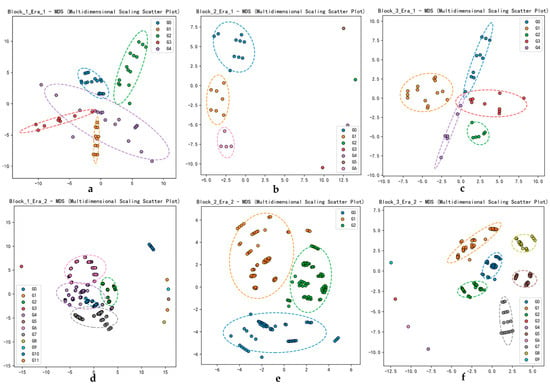

Analyzing the scatter diagrams of the clusters across these eras offers further insights into these changes (see Figure 10). Initially, Zeng’s Temple had few communities, each courtyard effectively forming its own cluster, while the relationships among clusters were relatively distant. After the temple was repurposed for residential use, the number of clusters surged, largely because of the increased number of functional units and a broader variety of topological linkages. During this stage, the overlaps between different clusters also intensified, reflecting the communal lifestyle and shared spaces that emerged with residential functionality. In Li’s Temple’s case, the block originally contained only the temple itself and a few scattered structures, so the clustering pattern was limited to a handful of temple-based functional groups, plus isolated buildings that did not coalesce into a cohesive community. After the temple was converted for residential use, the overall number of communities decreased—primarily because the newly formed clusters included many more units, with generally loose internal distances. This phenomenon aligns with the substantial influx of residents and the subsequent merging of previously distinct spaces. In the traditional era, Tao-Lin’s Temple exhibited a clustering pattern similar to that of Zeng’s Temple, with a small number of well-defined communities. However, as residential use intensified and the number of occupants grew, the number of clusters also rose. During this phase, internal connections within each cluster became more robust, giving rise to a new community structure.

Figure 10.

MDS scatter plots of building-level clusters (MDS Dim 1 vs. Dim 2). Panels (a–c) show the 1920s, panels (d–f) the 1970s, for Zeng’s, Li’s, and Tao-Lin’s temples, respectively. Each point is a building; dashed ellipses enclose the clusters identified in Figure 9. Denser point clouds and the greater overlap in (d–f) confirm that clusters grew larger and became less segregated over time.

The observed shifts in community structure are directly linked to changes in everyday spatial routines. Despite a sharp rise in subgraph conductance, Zeng’s Temple has retained a geographically stable pattern: daily activities still orbit the central courtyard (see Figure 9a,d). Yet the scatter plots reveal that, although the physical footprint appears unchanged, individual communities now converge into a single dense core that is increasingly difficult to differentiate (see Figure 10a,d). This trend coincides with the redistribution of domestic space and services from a concentrated to a more dispersed layout, progressively eroding the courtyard’s former centrality. In Li’s Temple, extensive spatial interventions have disrupted the original layout (see Figure 9b,e), and the scatter plots display fewer communities, each containing a larger set of nodes (see Figure 10b,e). The looser clustering of shared facilities and evolving social ties have produced a flatter, more diffuse structure. In Tao-Lin’s Temple, the smallest of the three cases, the community boundary originally defined by the temple has expanded; several interior nodes are now absorbed into neighboring clusters (see Figure 9b,f). The corresponding scatter plots show a tighter agglomeration of nodes (see Figure 10b,f), reflecting the proliferation and spatial dispersion of shared amenities. In short, the shift from a single, centralized service core to multiple, decentralized facilities—and the attendant growth in shared space—closely underpins these emerging community patterns.

5. Discussion

5.1. Drivers of Spatial Evolution

From the quantitative graph and subgraph results, it appears that when ancestral temples shift from ritual spaces to everyday living spaces, they undergo a structural transformation from relatively self-contained to markedly more dispersed, indicating a dramatic change. By using the temple’s gravitational network as a subgraph, we observe that its once relatively independent structural features begin to shift. Simultaneously, community detection at the block level reveals the dismantling of earlier community structures and the emergence of new clusters aligned with everyday residential patterns. These two findings mutually reinforce each other, confirming that in historically inhabited districts, the predominant community structure transitions from one centered on traditional dwelling and ritual practices to one rooted in daily life demands.

All three temples shift from closed ritual hierarchies to open residential networks. For Zeng’s Temple, everyday residential practices altered internal relationships, but because physical interventions were modest, changes in the broader community pattern remained limited. Li’s Temple enjoyed the greatest initial cohesion thanks to its dual-axis layout. A shortage of public housing, coupled with the temple’s prime location, prompted local authorities to demolish some original buildings and insert higher-density blocks, fracturing the ceremonial axis. These overlapping institutional mandates and daily needs radically reconfigured the community structure, leaving virtually no trace of the original layout. For Tao-Lin’s Temple, as state sponsorship and patriotic symbolism lost their priority over time, meeting residential demand became the overriding task. The erosion of symbolic meaning, together with new regulatory pressures, ultimately yielded the highest conductance and generated a block-spanning community that dissolved the temple boundary. All three temples share the quantitative signature of lower embeddedness and higher conductance; the different degrees and the shifts in community structure call for a further exploration of their underlying drivers.

Because space is a product of social relations and therefore fluid, its configuration is always contingent on prevailing lifestyles and historical context []. Changes in residential patterns correlate closely with shifts in spatial structure and involve multiple influencing factors (see Table 3). To radically break the original spatial configuration, reforms in land and housing property rights and transaction mechanisms are essential. Policy design and enforcement thus exert decisive influence on the fate of historical urban spaces []. Institutional factors thus play a pivotal role in converting ritual spaces into everyday living environments. While temples were originally conceived as instruments of moral instruction, they are progressively dismantled and re-assembled under new institutional logics to meet emerging residential needs. For example, changes in land policy led to the state acquisition of formerly private land, which was then redistributed to a broader population. Accompanying these institutional changes, the number of fundamental units in the three temples increased by 241% (from 55 to 188), 304% (from 25 to 101), and 286% (from 30 to 116). Although the overall spatial footprint remained unchanged, this substantial rise drove new space requirements. This resulted in uniform spatial dimensions for each household within the new common living arrangement; meanwhile, the influx of additional residents heightened the space’s susceptibility to everyday life influences. Additionally, the establishment of a formal housing system introduced significant differences between public and private housing. While private housing could be bought or sold, public housing remained state-owned, and acquiring a new residence required relinquishing one’s existing state-owned unit. Because management, allocation, and transaction rules diverged, the same physical structure could undergo distinctly different spatial modifications depending on whether it was classified as public or private. Under these evolving institutional conditions, daily life came to exert a fundamental influence on spatial structures. The reconfiguration of temple space embodies an ongoing negotiation among social groups over spatial advantages; such functional conversions remain inseparable from everyday practices that, through spatial appropriation, reshape both use and form [,]. Originally, ancestral temples were configured to meet formal ceremonial needs; once residential occupants arrived, however, large-scale ceremonial elements gave way to finer-grained, daily functional demands. As a result, installing essential facilities—such as kitchens and washrooms—within each household became crucial, effectively reorganizing the entire layout around individual requirements. Likewise, the shared spaces connecting these fundamental units came under greater demand. For example, in Zeng’s Temple, the number of shared spaces changed only slightly, from 27 to 28, yet the average number of fundamental units relying on each shared space rose from 2.15 to 6.07—a 182% increase. With limited space available, meeting diverse daily needs required progressively denser, more intensive adaptations. In addition, cultural factors significantly affect spatial transformation. Local traditions and customary practices continually renegotiate the value and meaning of inherited forms []. Traditional extended-family structures and cultural conventions remain deeply intertwined with ancestral temples, which often serve as central lineage symbols. The growing focus on individual value eroded these traditional forms, further reshaping them in everyday contexts.

Table 3.

Key factors in the spatial transformation.

Beyond these internal drivers, broader urban dynamics have been critical to the temple’s spatial transformation. Successive regime changes triggered a major wave of in-migration (state enterprise employees, military families, and others), creating an acute surge in housing demand. These newcomers also introduced diverse cultural norms and everyday practices, including different attitudes toward ancestral worship. These factors pushed the ancestral temple to evolve from a purely ceremonial facility into a space oriented toward daily living. Nanjing’s industrialization strategy concentrated factory workers near the urban core, directly intensifying spatial pressure in the dense neighborhood that hosts the ancestral temple. Finally, the replacement of the traditional street grid with a modern road network improved overall accessibility; lineage temples became far easier to reach, encouraging a more open spatial layout.

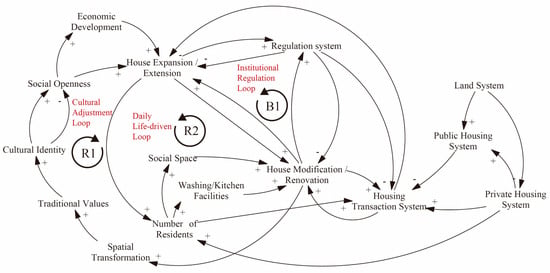

5.2. Causal Loops

As ancestral temples within cities transitioned into urban residential spaces, multiple interrelated forces shaping spatial and community structures interacted in feedback loops, thereby accelerating this drastic transformation. To shed light on these mechanisms, we employ a causal loop diagram [] to pinpoint the pivotal factors behind spatial change. We list an array of variables—including policy, social behavior, economic investment, cultural tradition, technological capacity, historical legacy, and geographical conditions—each represented as a node in the diagram. For every variable, we specify its direction of influence: a “+” sign means that an increase in one factor tends to raise another, whereas a “−” sign indicates a contrary effect. Building on the factors identified above, we develop a causal loop diagram depicting how ritual spaces evolve (Figure 11). Analysis reveals that spatial modification variables, such as “House Expansion/Extension” and “House Modification/Renovation”, occupy a central position in the diagram. This configuration underscores house- and space-related modifications as critical to the transformation of ritual spaces, shaped by both institutional and cultural constraints as well as by everyday life and economic forces.

Figure 11.

Causal loop diagram featuring three principal loops: Cultural Adjustment, daily life-driven, and Institutional Regulation.

The interactions among these factors produce three main loops:

- Cultural Adjustment Loop: As social openness and economic development increase, traditional values and cultural identity are re-stimulated. On the one hand, people begin to reinterpret traditional culture in a more open context; on the other, economic growth allows greater resources to be used to protect or renovate traditional spaces. Overall, R1 is a self-reinforcing loop in which culture and social openness mutually influence each other, resulting in a readjustment process.

- Daily Life-driven Loop: As the number of residents rises, so do demands for everyday functional spaces. To meet these needs, continual house remodeling and renovations take place, further accelerating spatial conversion—shifting from purely ritual usage to strengthened residential functions. The deeper this transition, the better it satisfies diverse daily requirements, in turn attracting more people and activities. R2 thus represents the fundamental engine of everyday life driving spatial change: when the original ritual layout no longer meets daily living needs, reconstruction or expansion becomes inevitable. If this loop keeps reinforcing itself, a ritual space eventually transforms into a fully common living environment.

- Institutional Regulation Loop: Excessive expansions, renovations, or demolitions can trigger intensified stricter regulatory measures (e.g., permits, fines, or demolitions of unauthorized structures). Enhanced regulation, in turn, suppresses over-modification, steering the system toward a balance. Acting as a self-balancing mechanism, this loop prevents unlimited spatial sprawl and unlawful construction. When regulation is lax, R2 (the daily life driven loop) may lead to overexpansion; when it is overly strict, legitimate updates can be hindered. B1 indicates the extent and pace of actual modifications, effectively acting as a control lever.

The three feedback loops do not operate in isolation; they jointly affect spatial transformation. The interplay between the daily life loop and the Institutional Regulation Loop (R2-B1) reveals how lax versus stringent regulation modulates the scale and frequency of everyday spatial alterations. Renovations and extensions driven by daily needs constantly conflict with formal controls, such as building permit procedures and penalties for unauthorized construction. When regulation is weak, frequent modifications intensify land use. When regulation tightens, transformation proceeds more slowly along planned, institutional guidelines. The interaction between the Cultural Adjustment Loop and the daily life loop (R1-R2) shows how cultural elements adjust their mode of adaptation under the pressure of everyday requirements. Lineage identity and family ethics slowly shape the form of spatial change. Rapidly evolving daily demands pressure traditional spaces to adapt faster. The exchange between Institutional Regulation and Cultural Adjustment (B1-R1) highlights the balance between cultural preservation and commercial redevelopment. Regulation safeguards heritage through historic building codes, yet overly rigid controls may constrain organic adaptation. Conversely, increasing commercialization and everyday appropriation often occur at the cost of eroding cultural features.

Throughout the conversion of ancestral temples from ritual spaces to residential spaces, spatial configurations are subject to varying influences from these different loops. At each stage, cultural and institutional factors continue to shift. We thus need to refine our analytical resolution down to the most fundamental spatial units to capture the structure of everyday living and thereby clarify the nature of spatial transitions. Viewing ancestral temples—originally devoted to ritual functions—as a prototypical case, this perspective enables a precise assessment of their spatial characteristics and transformation mechanisms.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study faces several constraints in its case selection, methodological design, and causal interpretation. Extending our research to a broader spectrum of sacred spaces and achieving deeper theoretical insight will require addressing the following limitations:

- Case study scope. Our empirical analysis centers on ancestral temples in residential historic districts of Nanjing. Applying the same approach to sacred spaces elsewhere in the Global South—such as Hindu temples, Islamic mosques, or Latin American churches repurposed in informal settlements—will demand culture-specific graph-construction rules. In Chinese ancestral temples, ritual spaces and residential buildings share a homologous layout, so functional ritual units can serve as graph nodes. In other contexts, however, the spatial syntax of sacred sites is closely tied to local behavioral norms and cultural practices; their structural trajectories may therefore diverge from the Chinese case.

- Methodological design. The present graph model uses proximity-based edges and treats node mass as the footprint area, an approach adequate for mid-scale temples within a distance-weighted gravity framework. Yet larger ritual complexes may require enriched weighting schemes that capture socio-functional importance—for example, social network or activity density—rather than surface area alone. Incorporating such metrics would avoid oversimplifying spaces whose social value outweighs their physical size.

- Causal loop representation. The causal loop diagram combines theoretical insights with two temporal snapshots. Limited time granularity and a small sample—partly due to urban demolition that has left few temples—reduce explanatory depth. Variables such as social openness were qualitative; future studies should test feedback loops with denser time series, a multi-city sample, and quantitative proxies for social openness.

5.4. Policy Implications for Urban Renewal

The spatial structure indicators proposed here constitute a practical toolkit for policy design. Modeling historic districts as graphs allows metrics such as embeddedness to function as real-time monitors of structural change, offering clear signals of impending disintegration or excessive openness. Planning level: Network indicators enable planners to intervene before historic layouts are eroded: community-scale spatial units can be delineated to safeguard the integrity of heritage structures. Monitoring level: We recommend establishing a long-term spatial network observatory. In historic quarters, the risk of over-adaptation is common; embedding metrics such as embeddedness in routine monitoring would set thresholds for permissible change, encourage adaptations that meet essential residential needs, and discourage unnecessary structural alterations. Practical deployment: Combining embeddedness with conductance also offers a quantitative basis for tiered renewal. Variations in these values allow historic districts to be divided into strict conservation zones and adaptive transformation zones. For each level, a community–government partnership can tailor the scale and intensity of interventions to the prevailing spatial structure.

6. Conclusions

Analyzing spatial evolution in complex historical districts calls for an integrated approach that addresses both spatial and social dimensions. By identifying the smallest functional units and their interrelations, spatial analysis can adopt an everyday living perspective, effectively integrating spatial configurations with social relationships. This approach offers a valuable framework for understanding transformations in complex historical contexts. In this study, by identifying the smallest functional units of temple architecture, we employed an access structure-based method to construct a topological spatial graph of both the temples and their surrounding blocks. Through analyzing subgraph relations and conducting community detection at the block level, we effectively captured how temples, originally ritual spaces, transitioned from relative concentration to fragmentation and eventually into denser reconfigurations. Institutional, everyday life, and cultural factors all play significant roles in this evolution. Our findings shed light on the broader shift from traditional society to the contemporary era. It thus provides a technical foundation for future investigations into how residential functions and spatial forms evolve while offering valuable implications for urban renewal as well as the conservation and adaptive reuse of heritage buildings. The methods proposed here yield critical insights for urban planners and researchers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L. and Y.Z. (Yue Zhao); methodology, Z.L. and Y.X.; software, Z.L.; validation, Z.L., Y.Z. (Yue Zhao) and Y.X.; formal analysis, Z.L.; investigation, Z.L. and Y.Z. (Yinghao Zhao); resources, Z.L. and Y.Z. (Yinghao Zhao); data curation, Z.L. and Y.Z. (Yinghao Zhao); writing—original draft preparation, Z.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.L.; visualization, Z.L. and Y.Z. (Yinghao Zhao); supervision, Z.L. and Y.Z. (Yue Zhao); project administration, Z.L.; funding acquisition, Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52278009.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the fact that the source files were obtained through paid access.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Clark, J.; Wise, N. (Eds.) Urban Renewal, Community and Participation; The Urban Book Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-72310-5. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, E.W. The Spatiality of Social Life: Towards a Transformative Retheorisation. In Social Relations and Spatial Structures; Gregory, D., Urry, J., Eds.; Macmillan Education: London, UK, 1985; pp. 90–127. ISBN 978-1-349-27935-7. [Google Scholar]

- Tonkiss, F. Space, the City and Social Theory: Social Relations and Urban Forms; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. From the Production of Space. In Theatre and Performance Design; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, W.; Du, J. Towards Sustainable Urban Transition: A Critical Review of Strategies and Policies of Urban Village Renewal in Shenzhen, China. Land Use Policy 2021, 111, 105744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnell, S.; Oldfield, S. The Routledge Handbook on Cities of the Global South, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK; Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-415-81865-0. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, M. Secularization as Declining Religious Authority. Soc. Forces 1994, 72, 749–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, Z.; Hongying, K.; Ling, Z.; Zou, L.; Xie, X. Correlation between Ancestral Temple Worship Sacrifice Culture and Clan Etiquettes in Traditional Settlements of Jiangxi Province. J. Landsc. Res. 2016, 8, 42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kuah, K.E. The Changing Moral Economy of Ancestor Worship in a Chinese Emigrant District. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 1999, 23, 99–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S.; Smith, N. The Politics of Public Space; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-136-08130-9. [Google Scholar]

- van der Tol, M.; Gorski, P. Secularisation as the Fragmentation of the Sacred and of Sacred Space. Relig. State Soc. 2022, 50, 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.H.; Henrie, R. Perception of Sacred Space. J. Cult. Geogr. 1983, 3, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumdar, S.; Mazumdar, S. Sacred Space and Place Attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 1993, 13, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhai, B.A. The Household as Sacred Space. In Family and Household Religion: Toward a Synthesis of Old Testament Studies, Archaeology, Epigraphy, and Cultural Studies; Albertz, R., Nakhai, B.A., Olyan, S.M., Schmitt, R., Eds.; Penn State University Press: University Park, PA, USA, 2014; pp. 53–72. ISBN 978-1-57506-886-2. [Google Scholar]

- Day, K. The Construction of Sacred Space in the Urban Ecology. cro 2008, 58, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W. Placeness Production of Sacred Space, Resident Identity Differentiation and Daily Resistance: A Case Study of Qingkou Village of Hani Nationality in Southwest China. Tour. Trib. 2019, 34, 96–108. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar, S.; Mazumdar, S. Religion and Place Attachment: A Study of Sacred Places. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorokhov, S.A.; Dmitriev, R.V. Experience of Geographical Typology of Secularization Processes in the Modern World. Geogr. Nat. Resour. 2016, 37, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Zheng, W.; Yi, M.; Wu, C.; Wu, H. Architectural Space and Decorative Art of Ancestral Halls in Jiangxi Province: A Case Study of the Hall of Respecting Morality. J. Landsc. Res. 2019, 11, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Guoqing, M. The Ancestors’ Drawing Power: Mobile Clan-Based Groups and Social Memory: Examples from the Southeastern Han Chinese. Chin. Sociol. Anthropol. 2005, 37, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure, D. Emperor and Ancestor: State and Lineage in South China; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-8047-6793-4. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N. Governing Rural Culture: Agency, Space and the Re-Production of Ancestral Temples in Contemporary China. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Yin, D.; Zhu, H. Secularisation and Resistant Politics of Sacred Space in Guangzhou’s Ancestral Temple, China. Area 2019, 51, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Su, C.; Liu, L. Analysis of the Spatial Features and Living Protection of Ancestral Temples in Bayu Ancient Towns Based on the Concept of Cultural Landscape. J. Southwest China Norm. Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2021, 46, 150–158. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.; He, S. Changes in traditional urban areas and impacts of urban redevelopment: A case study of three neighbourhoods in nanjing, china. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2005, 96, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, S. God Is Dead: Secularization in the West; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2002; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N. Secularization, Sacralization and the Reproduction of Sacred Space: Exploring the Industrial Use of Ancestral Temples in Rural Wenzhou, China. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2017, 18, 530–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habraken, N.J. Supports: An Alternative to Mass Housing; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1-00-301471-3. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, O. Converting Houses into Churches: The Mobility, Fission, and Sacred Networks of Evangelical House Churches in Sri Lanka. Environ. Plan D 2013, 31, 1062–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Social Space and the Genesis of Appropriated Physical Space. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2018, 42, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Wu, P.; Wang, G.; Zhan, J. On the Impact of the Changes of Social Ideology and Institutions on Land Use in China since the 1950s. Geogr. Rev. Jpn. 2004, 77, 813–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriandjo, H.S.; Surya, B.; Salman, D.; Bahri, S.; Muhibuddin, A.; Yudono, A.; Syafri. Socio-spatial transformation model of urban architectural elements: The perspective of local communities in the corridor of boulevard ii, the coast of manado city, indonesia. JSSM 2023, 18, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSayyad, N. Informal Housing in a Comparative Perspective: On Squatting, Culture, and Development in a Latin American and a Middle Eastern Context. Rev. Urban Reg. Dev. 1993, 5, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbaye, J.; Dinardi, C. Ins and Outs of the Cultural Polis: Informality, Culture and Governance in the Global South. Urban Stud. 2019, 56, 578–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, J. Rethinking Secularization: A Global Comparative Perspective. In Religion, Globalization, and Culture; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 101–120. ISBN 978-90-474-2271-6. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, J. Is Secularization Global. In Neue Räume Öffnen: Mission Und Säkularisierungen Welweit; Verlag Friedrich Pustet: Ratyzbona, Germany, 2013; pp. 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, N.; Lombard, M.; Mitlin, D. Urban Informality as a Site of Critical Analysis. J. Dev. Stud. 2020, 56, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L. The Sacred and The Secular: Exploring Contemporary Meanings and Values for Religious Buildings in Singapore. Asian J. Soc. Sci. 1992, 20, 18–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A. Urban Informality: Toward an Epistemology of Planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2005, 71, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudva, N. The Everyday and the Episodic: The Spatial and Political Impacts of Urban Informality. Env. Plan A 2009, 41, 1614–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haid, C.G.; Hilbrandt, H. Urban Informality and the State: Geographical Translations and Conceptual Alliances. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2019, 43, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioux, L.; Scrima, F.; Werner, C.M. Space Appropriation and Place Attachment: University Students Create Places. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 50, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhoff, A. Nineteenth-Century Urbanization as Sacred Process: Insights from German Strasbourg. J. Urban Hist. 2011, 37, 828–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamete, A.Y. On Handling Urban Informality in Southern Africa. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2013, 95, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]