Abstract

Airport terminals are considered transitional spaces in travelers’ journeys. They tend to be globalized in architectural features, competing to show their superiority by using the latest technologies and contemporary designs, yet it is often forgotten that they are the gateways to their host cities and that they should reflect their identity. This paper aims to investigate the impact of adopting the identity of the host city in the terminal’s design through different identity indicators, asking if it would enhance the user’s experience and motivate the passengers to explore the cultural side of the city. Through the analysis of four major airports in Saudi Arabia, identity indicators in the architectural design and interior settings were explored to understand how identity is reflected in each airport. A questionnaire was distributed to delve more into the impact of these identity indicators on the passengers’ experiences in the different spaces in the four airports. It appeared that these indicators create a sense of attachment and interaction between the users and the spaces, transforming them into places that have the potential to enhance travelers’ journeys and emotions to present a memorable and sustainable cultural user experience, elevating the quality of their trips.

1. Introduction

Airport terminals are one of the most emblematic building types of architecture that represent the new global wave of building types. Showing off their economic prowess and adaptability to human factors, novel building technology, and vibrant engaging user experience have eclipsed their design character as they are more inclined toward globalization and less associated with the cultural identity of the city they belong to, forgetting that the airport terminals are, as Dr. Rim Zougheib describes it, play a crucial role in shaping a city’s identity and image [1]. Examples of such airport terminals that are considered global international transit spaces are the airports of Singapore and Qatar. In this increasingly competitive industry, airports have recently started to actively promote customer retention and long-term success by aiming for customers to have positive opinions and attitudes while in the airport, feel involved with the airport, and have good psychological well-being there [2].

Massey believes that airports have a “global sense of space” [3] since they attract a diverse range of individuals with varying backgrounds, personalities, and travel destinations, encompassing places for work, trade, retail, recreation, communal areas, and logistics. Despite their symbolic nature, many airports are considered prime examples of “placelessness” as they have no special relationship with the places in which they are located, as stated by Edward Relph in his seminal “Place and Placelessness” [4]. Instead of designing a space standing for a certain culture, airport designers have created spaces that can stand as the background for any nationality. This could be changed by introducing identity features to the building, creating a “place” that is a great iconic representative of its location to become a narrative cultural “place” within its setting.

Saudi Arabia covers the vast majority of the Arabian Peninsula and includes various regions that are characterized by distinct landscapes, topographies, and architecture. As a result, its architectural heritage is extensive and varied. Economic and regional shifts during the late 1960s and early 1970s had a significant impact on Saudi Arabian architecture. This change was because of the increase in oil prices in the 1970s, which allowed the Saudi government to establish a strong, centralized administrative structure based mostly on oil revenue [5]. Recently, it has become one of the Middle East’s fastest-growing countries, changing the building industry and urban planning, as a number of massive projects are underway that will completely reshape the country and revitalize various cities and districts, including historic ones with rich cultural history and empty spaces [6].

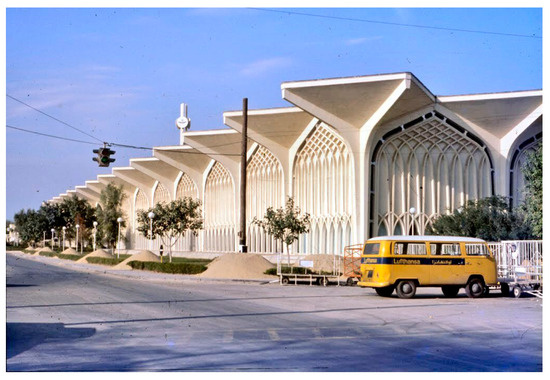

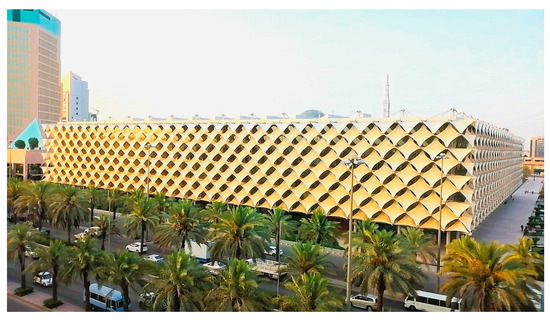

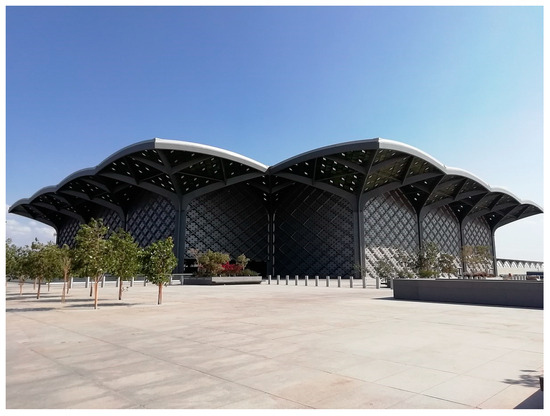

However, it is crucial to follow humanitarian architecture as it plays a significant role in establishing a balance between development and authenticity because of its dual roles as a guide for reconstruction and an agent of sustainable urban planning [7]. Modern Saudi cities have emerged quickly, paying little attention to the socio-cultural norms that shape their behaviors and create the country’s traditional built environment [8]. This situation has created a gap between modernity and tradition. In accordance, the central government has suitably increased its supervision and involvement and provided more political backing in areas like the construction of environmental infrastructure, environmental monitoring facilities, and inspection methods. Saudi Arabia has become steadfastly dedicated to preserving its rich cultural legacy while looking to the future. That is why incorporating traditional Arabian architecture into modern design is a key component of Vision 2030 [9]. The Saudi government has attempted to influence the architectural style of massive new governmental and public architectural projects, such as the Ministry of Interior, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, airport terminals, railway stations, central libraries, and office buildings, creating new contemporary hybrid models of architecture, resulting in a unique glocal architectural language carrying Saudi identity inspired from the traditional architecture but with a modern flavor, Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3.

An organization, the Saudi Heritage Commission, was established to fulfil Saudi’s 2030 vision concerning the preservation and promotion of the unique cultural heritage of Saudi Arabia. The Commission has fostered a sense of identity and belonging among local populations [10]. In an effort to balance the past and present and serve as a global source of inspiration for architectural innovation, current Saudi architecture aims to combine modern design with historical references to improve the urban landscape and quality of life [11]. Such a commission is important as it is believed that innovation in industrial and building technologies can be fueled by improvement in environmental regulation requirements [12]. In its new designs for transportation terminals, Saudi Arabia ensures the promotion of powerful identity characters that connect them to their contexts, backgrounds, and people.

Figure 1.

Dhahran Airport, 1960, with traditional architectural features appearing in the façade. Source: https://picryl.com/media/dhahran-airport-1960s-06-e289fd, accessed on 13 March 2025.

Figure 2.

King Fahad National Library, Riyadh, 1990, with a tent-inspired façade wrapping the whole building. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:King_Fahad_Library.jpg, accessed on 13 March 2025.

Figure 3.

Haramain High-Speed Rail Station in Al Madina, 2019, with traditional architectural patterns and palm-inspired columns. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Haramain_High_Speed_Railway_Station_in_Medina.jpg#Licensing, accessed on 13 March 2025.

1.1. Architectural Identity vs. Globalization in Airport Terminals

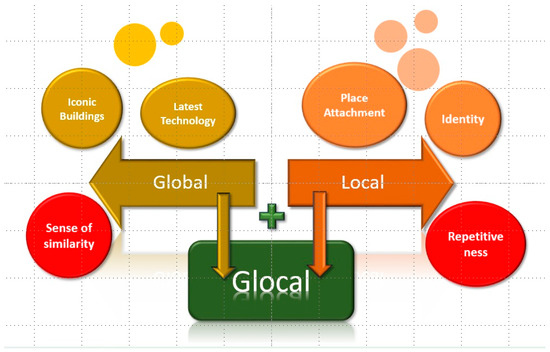

Due to the progression in urban homogenization, where local character falls victim to global styles and materials, globalization has had a significant impact on architecture. This impact eliminates regional architecture in favor of standardized functionality and efficiency over cultural identity [13]. However, local architecture is an important element that reflects cultural identity and creates a sense of place. Identity defines and distinguishes an object from other things. It works both ways, using certain characteristics, carrying the meaning of existence as Paul Brislin explains it, “… there is no doubt that a sense of identity is essential to survival—of individual, family, group and neighborhood” [14]. This means that identity is not only concerned with individuals but extends to define societies, countries, and whole regions. This shows that the identity notion is a complex issue that is present naturally, even if not summoned or recalled, as it gives a sense of attachment and belonging. Since identity is a representative of people, their culture, their lives, and their politics as Hamid and others clarify, “Identity is a complex issue because it stems from numerous determinants such as those from social and political order” [15] and since people and their societies are changing, identity therefore exists naturally and is always evolving as people inevitably change as a reaction to certain external stimuli. Martin Heidegger states that people should keep looking for a sense of belonging in any space through its architecture and urban setting, providing it with a sense of place [16]. A space turns into a place through the cultural, physical, and emotional value that it gains through past experiences [17]. Therefore, identity is a crucial component in creating interaction between a place and its users and promoting the entire context. Although globalized buildings succeed in making a statement and fostering the latest technological trends and attributes, they ultimately seem disconnected from the local identity, losing the distinctive personality and resulting in a sense of similarity, which is one of the drawbacks of globalization.

Consequently, identity and globalization are two opposing forces. There will always be exchange, attraction, and conflict between any two opposite forces, regardless of how powerful they may be [18]. Thus, architectural identity and globalization are and will always be competing forces that have to co-exist side by side, implying that creating hybrid models that boost both identity and globalized features in a glocal atmosphere is the most effective combination for public spaces, Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Opposing forces of local and global architecture with their advantages and disadvantages when combined they form glocal architecture, source: Authors.

Some places are characterized by being global, having a chaotic picture of different and opposing identities. Every major city around the world has developed airports as hubs for international transition and people flow, which is an iconic illustration of globalization. All global characteristics have drawn on the features of airports such as the used technology, leisure features, displaying and selling of consumer products, or even basic features of the architectural design. Airports can be referred to as “places of Globalisation” that are defined, or are at least heavily influenced, by the contemporary emphasis on leisure, consumption, and global mobility [19]. The functionality of the architectural design of airports and their environments has been fueled by globalization. Decision-makers are more concerned with achieving the desired visual impression by following the design idea or budget than they are with using local elements. Users have become disengaged from the built environment as a result of this homogeneity, which has produced similar physical places. Globalization has affected airports’ architecture, producing new appearances resulting from the blending of cultures and the disengagement from tradition, context, and, frequently, cultural origins [20]. Globalization and changing societal dynamics have led to a loss of “sense of place”, identity, and continuity in architectural development [21]. Consequently, global ideas are perceived as a threat to locals. The sense of ‘place’ is on the verge of disappearing due to external factors outside the control of its inhabitants. A global space’s globality is not negated by the addition of identity features; on the contrary, it is enhanced, and it adds to the value of the space, setting a special spirit for it [22]. The issue of “Identity vs. Globalization” could be considered a contemporary version of the case of place and placelessness raised by Edward Relph. Relph concentrates on people’s identities concerning their location while analyzing place in depth. Peng, et al. state that the process by which a person is evaluated is a representation of social and cultural interactions, which is the impact a location has on a person’s identity [23]. Auge also differentiated between a place and a mere space through the existence of identity, calling it a place and a non-place [24].

Therefore, global architecture could have some identity features that characterizes it without losing its globality and provide some attachment to its users for an authentic experience. At the same time, identity does not imply a return to the past and a lack of use of modern tools and technology. It is challenging to meet the cultural needs of all airports’ users due to their diverse backgrounds, but it is more important to adopt the local identity of the airport’s host city as a means of cultural empowerment.

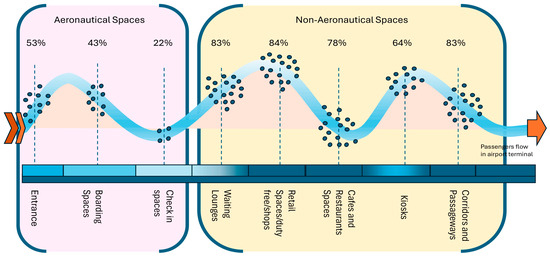

In terms of culture, airports could be viewed as spaces in-between, between a traveler’s home culture and a new one, or between two distinct cultures depending on the traveler’s point of departure and their destination. Passengers’ emotions vary between stress, excitement, nostalgia, anxiety, fatigue, and indifference. Introducing the architectural and arts cultural elements of the airport’s host country may have an instrumental role in attracting passengers’ attention, fostering cultural passion, and elevating their trips to a higher intellectual level. Airports stand as ambassadors of their countries to create a lasting impression of unique identity on travelers. The absence of this fingerprint leaves the airport as a non-place with no meaning and without an architectural impact on the user. It is well known that users’ behaviors differ in aeronautical spaces (e.g., boarding, check-in, and security) compared to non-aeronautical services (e.g., retail services, food courts, or booths and waiting lounges). These non-aeronautical spaces could be described as consumer spaces that attract travelers with their globalized features and should be looked at as fertile land for introducing the local culture to all travelers for the first time as a welcoming gesture and an advertising plan for more touristic impact. The architect should take advantage of the waiting time of the passengers, after the stress of completing traveling procedures, to involve them in a deeper cultural experience. It is one of the most essential responsibilities of architects to create experiences in space [25]. Benefitting from the waiting time in airport terminals can add a deep dimension to the traveling journey, creating interaction, memories, and place attachment. To engage passengers, relieve them from stress, and enhance their experience, easy and well-designed way-finding systems for ease of access and interior settings that deal intellectually with the passengers’ minds, attract their attention, increase their knowledge, and satisfy their curiosity are needed.

1.2. Identity Indicator Design Characteristics in Airport Terminals

Recognizing architectural identity is a multifaceted responsibility. Methods of detecting it are different according to the scale of the user experience, whether on a planning and urban scale, architectural scale, or interior scale. Airports provide a unique user experience that is distinct from any other space due to the nature of the mood and attitude of the users while they are in the airport. Kim et al. concluded that waiting and screening times evoke negative emotional responses [26]. Tiredness and rapidity in transferring from one hall to the other and the willingness to complete all traveling procedures deprive travelers of enjoying many spaces in the airport. The majority of travelers do not perceive the mass design of the airport or understand the intention of its designers. In addition to the ease of functionality and speediness in circulation, the morphological attributes of the airport are supposed to have a psychological impact on passengers by relieving their tension and boredom. Designing the identity features of the airport’s host country introduces a new dimension (twist) in experiencing the airport as a ‘place’ instead of being an area in between, putting the airport spaces as a vital milestone in the journey’s route. Whether the airport is a starting point in the journey, a transitional space, or a destination, local identity features open an interesting, informative, and critique-friendly path in the passenger’s journey, creating a moment of psychological relaxation and promoting cultural exchange. Different scholarly reviews discuss how identity elements should be used to deliver their message and meaning in different spaces. Alavi & Tanaka state that “Identity” is shaped by a variety of cultural, historical, social, economic, and environmental factors. Every community’s architecture contributes to clarifying its identity since it conveys its ideas, messages, and unique characteristics. A building’s form, materials, details, façades, history, and cultural references are a few examples of this [27]. Ali et al. state that place identity can be conceived through forms, images, and activities. They explain that people’s emotional impressions and reactions extracted from architectural expressions are important to understanding the spirit and essence of places [28]. Mahdavinejad and Saadatjoo added some other parameters that contribute to showing architectural identity, such as the construction technology and the relationship with the surroundings [29]. Many other scholars, such as Torabi and Berahman [30] and others have accentuated the importance of the surrounding context as an important parameter in sensing the architectural identity. Yücel & ArabacioĞlu elaborated more on the different categories of contextual impact on architectural identity, stating that physical context, sociocultural context, and local context all collaborate to shape place identity. They showed how defining contextuality as either cultural or physical is inconsistent [31]. Other scholars believe that social interactions, whether they are cultural, political, or economic, are vital as identity indicators [28]. Others have divided identity indicators into formal appearance, physical settings, and natural givens [22,32]. Khaznadar and Baper proposed a model that combines two opposing viewpoints to describe identity as a continuous process. The first asserts that architectural identity is the one passed down through the generations, whereas the second believes that new technology and scientific discoveries can create architectural identity [33]. Accordingly, identity indicators can be discussed from many perspectives according to the intentions and points of view of the researchers, while in the case of airport terminals and due to their specific nature, the constant reality perceived by its users is the intention of the architect that designed the airport, and the elements they used to express their ideas. Architectural expression elements are embodied in both the exterior appearance and interior settings of the airport.

In the case of airport terminals, demonstrating local identity needs a specific framework of indicators as it depends mainly on the mood of the passengers and their circulation flow in the spaces. Passengers might perceive the layout of the airport from the airplane or notice parts of the façade according to the portals from which they are entering or leaving. However, the interior settings should offer the most engaging user experience because travelers spend most of their time at airport terminals indoors. Enhancing passengers’ journeys in the airport with a cultural dimension will, unquestionably, elevate the travelers’ user experiences.

According to Patil & Raj, airport terminals serve as a city’s first image and symbolize it. As a result, the form and function of terminal buildings are as equally important as planning and architectural considerations [34]. Airports are considered miniature cities including multiple functions where different people with various backgrounds meet, communicate, and interact with each other. The huge areas of airport terminals, the large numbers of passengers who visit and interact with the terminals every day, and the numerous functions, whether hosted by different spaces or by the unique and complex infrastructure, convert the building into a functional hub and allow it to be dealt with as urban space that needs placemaking to elevate passengers’ experiences to new heights. Designing a quality space and transforming it into a place helps passengers to feel less stressed and attracts more customers to commercial spaces, forming a kind of connection between the passengers and the transformed places. By valuing the uniqueness of the identity, celebrating the differences, eliminating the inauthenticity of globalism, and engaging with local cultures, a new place is created. Fred Kent identified the benefit of turning spaces into places as converting them into a place that you want to stay in instead of a space that you cannot wait to get through [35]. This will turn the spaces into livable places where social interactions are enhanced and the well-being of users is improved [36].

2. Materials and Methods

This paper aims to explore the impact of identity indicators on passengers in Saudi airport terminals. Saudi Arabia has a rich cultural and traditional heritage that marks its identity. As an iconic Islamic country for Muslims worldwide and a major part of the Arabian Peninsula with its specific environmental and cultural heritage. Four main international airports in Saudi Arabia were chosen to be case studies. Saudi airports stand as gateways to introduce the kingdom to its visitors. Due to its religious significance, preconceived images are already printed in many of the visitors’ minds.

The research’s main hypothesis is that “identity indicators can redefine spaces in airport terminals to be ‘places’ creating new user experience”. This will lead to social and community engagement and will have touristic and economic implications.

2.1. Research Methodology

After the literature review defining the concept of places and placeness and showing the importance of creating places in airport terminals, identity indicators’ role was defined in comparison with global architectural elements. Different frameworks for understanding identity indicators in architectural expressions were discussed. In this study, we employed the comprehensive analysis approach to understand the concepts of designing the selected airport terminals in Saudi Arabia concerning the use of identity indicators. The first step in demonstrating how identity features were deployed in the architectural expressions in the airport terminals’ designs was to analyze the architectural concepts and ideas of the terminals and then validate their implementation in their designs. The second step was applying a questionnaire to understand the users’ perception of the identity indicators in airports and their emotional interaction with them. The quantitative and qualitative analysis of the questionnaire gave more insights into whether using identity indicators succeeded in representing the Saudi character, their noticeability, and their implications for the passengers and their user experience in airport terminals.

In order to evaluate identity indicators in Saudi Arabia’s airports, four airports were chosen to be case studies. Two of these airports stand as gateways for the kingdom in its religious role as they are portals for the two most important Islamic cities, Makkah and Al Madinah. The two airports are King Abdulaziz Airport in Jeddah and Prince Mohammad Bin Abdulaziz Airport in Al Madinah Almonawara. The other two airports are the capital city’s airport in Al Riyadh, which is King Khalid International Airport, and the airport in the economic capital of the kingdom in Dammam, which is King Fahd International Airport. The two cities, Al Riyadh and AL Dammam, are rich in two distinctive architectural cultural features, Najdi and Gulf heritage elements. Every airport is international, has a high passenger density, was constructed and inaugurated in a separate decade, spanning 40 years from the 1980s to the 2020s, and has a unique architectural design, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main information about the four airports chosen to be case studies. Source: Authors.

Table 1.

Main information about the four airports chosen to be case studies. Source: Authors.

| Airport | City | Year of Inauguration | Architect |

|---|---|---|---|

| King Khalid International Airport, KKIA | Riyadh | 1983 | Hellmuth, Obata & Kassabaum (HOK) |

| King Fahd International Airport, KFIA | Dammam | 1999 | Yamasaki & Associates |

| Prince Mohammad Bin Abdulaziz International Airport, PMAIA | Medina | 2015 | GMW Architects |

| King Abdulaziz International Airport, KAIA | Jeddah | 2019–2021 | SOM and Pascall & Watson |

Each airport was analyzed in terms of its identity indicators and how they relate to its architectural concepts and then compared to the questionnaire results that evaluate the impact of these identity indicators on passengers in the airport terminals.

2.1.1. King Khalid International Airport, KKIA

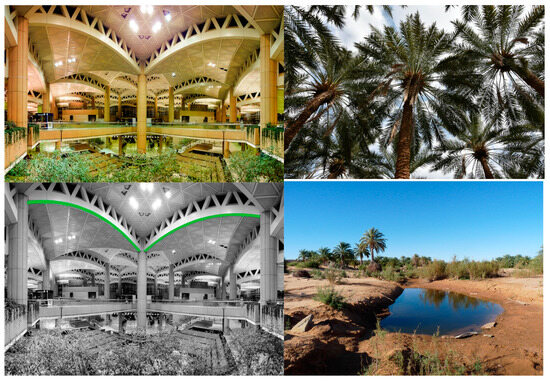

Inaugurated in 1983, the airport of the Saudi capital, Riyadh, King Khalid International Airport, was designed by HOK architects. As intended by the architects, the passengers’ first encounter with the airport is landing in a spacious clean oasis with trees and palms embedded everywhere, sunlight streaming through triangular openings in the multi-leveled roof, and water flowing down tiled banks into a pool [37]. The architects mimicked an indoor oasis essence, creating a surprising feeling of relaxation for a tired passenger expecting to land in the desert. This design led to a direct immersion in the identity of the host country, creating a welcoming contextual cultural environment.

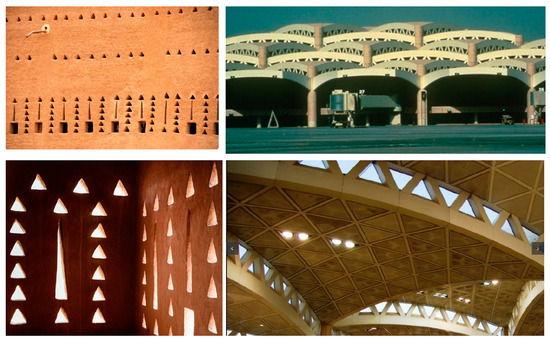

The architects drew on different traditional and cultural references, whether from the desert context, the oasis and tents from the Najdi heritage architecture and its triangular patterns, or from the Islamic architectural style that wraps the whole country and its arches, muqarnas, and shedding of light. The palm trees, a main feature of the Saudi contextual heritage, are translated abstractly in the structural columns, visually in the multi-height roof organization, and physically in the interior landscape of the airport (Figure 5 and Figure 6). The triangular, spherical arches that make up the terminal roofs are connected by trusses. Obata, one of the architects from HOK said, “Lifting these arches brought in the beautiful, natural, soft light” [37], Figure 7.

Figure 5.

The inspiration for KKIA from the idea of an oasis and palm trees. Source: Authors.

Figure 6.

The inspiration for KKIA from the traditional Najdi triangle. Source: Authors.

Figure 7.

Light and shadow in the interior space, KKIA. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:K.K.I.A_-TR-3_-_panoramio.jpg, accessed on 13 March 2025.

He described the design as growing from the inside out, revealing that the structure is the organizational element in the indoor spaces and the external form and mass design creator [37], Figure 8. The triangle patterns were used in the clerestory openings, shedding shadows on the floors. Triangular patterns also appear in the multi-leveled ceilings. These levels in the ceiling allow the façade to be emphasized as a consistent feature of the design (Figure 9). In an exquisite combination of Islamic, traditional, and futuristic design ideas, other indicators of identity are present in the central fountain, which uses Islamic geometrical shapes of triangles, forming a hexagon, Figure 9. Triangular patterns were used in tiling cuts in the floors with shades of beige colors in the interiors and exteriors inspired by the dunes of the desert. Traditional Najdi artwork and Islamic calligraphy art spread to cover the terminals’ walls Figure 10.

Figure 8.

Exterior façade of KKIA. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/activesteve/5256327212, accessed on 13 March 2025.

Figure 9.

The arched roof and the interior hexagonal fountain. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flughafen_Riyadh,_Innenaufnahmen_03.jpg, accessed on 13 March 2025.

Figure 10.

One of the artworks in KKIA terminal airport. Source: authors.

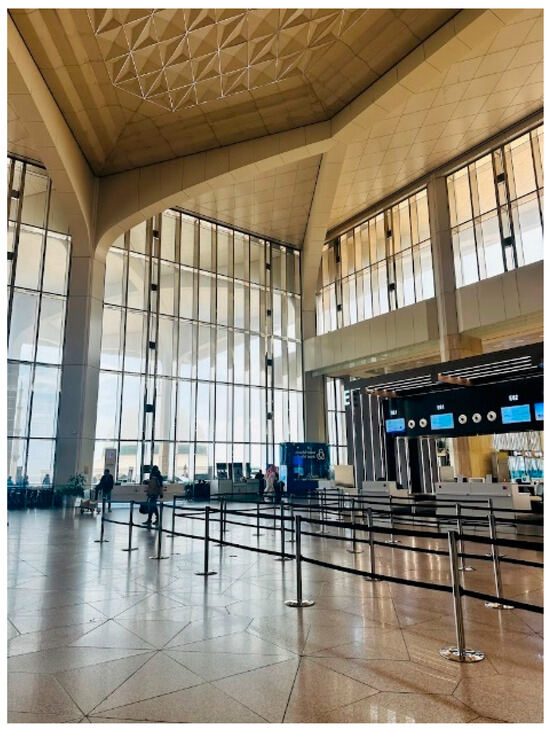

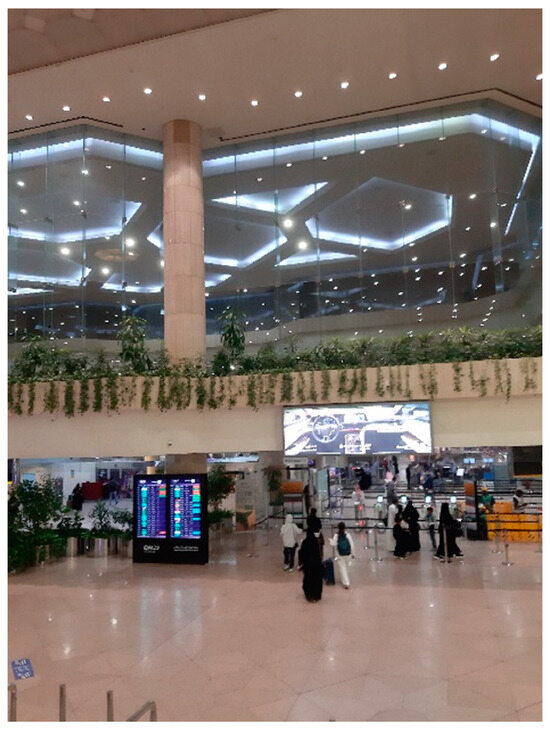

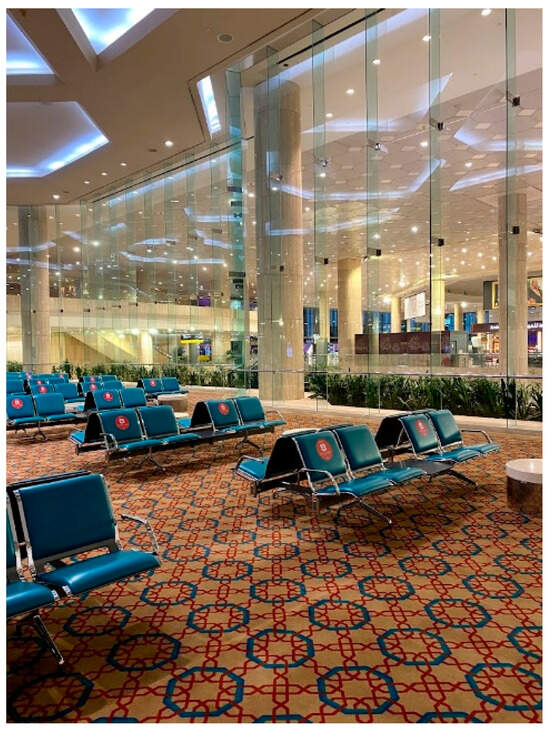

2.1.2. King Fahd International Airport, KFIA

Inaugurated in 1999, KFIA, the airport of the economic capital of Saudi Arabia, was designed by Yamasaki & Associates architects. The main concept intended by the architects was to emphasize efficiency, utility, and symbolism to signify Saudi Arabia’s past and culture in addition to the country’s ambitions for modernity [38]. The airport blends modern design with traditional Islamic architecture, reflecting Saudi Arabian culture through the use of arches, domes, geometric designs, calligraphy, and arabesques [39]. These motifs are seen in the airport’s interior and exterior flooring, walls, and ceilings. King Fahd International Airport (KFIA) could be characterized as a contemporary building

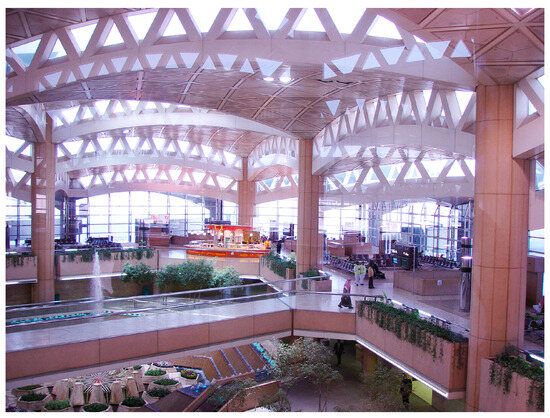

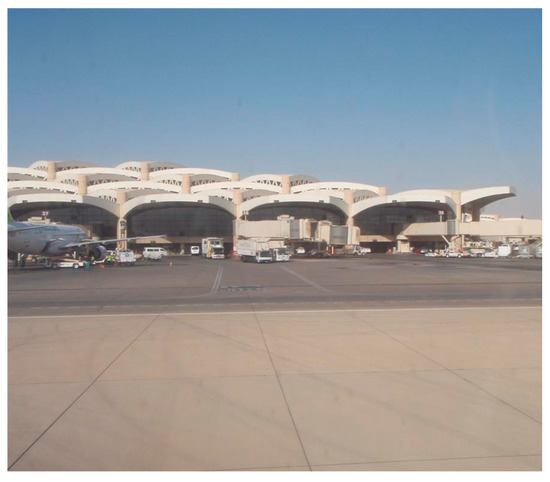

The main terminal building provides passengers with a vibrant and inviting entrance with its cantilever projecting a canopy carried by arched columns and modern glass façades. Large, sweeping arches support the airport’s roof, adding to the building’s overall architectural appeal and providing travelers with the first identity indicator Figure 11.

Once more, the abstraction of the palm tree is seen in the exterior arches and the columns continuing inside the building, creating geometrical patterns in the ceiling accentuated by false ceilings with hidden lights to emphasize the Islamic identity, Figure 12. Both the floors’ tiling cuts and the ceilings use these geometric patterns in a variety of ways, Figure 13. The fountain, with its three-dimensional geometric shape that integrates the beauty of plants and water in its octagonal shape, is another main focal point that can be perceived directly after entering the terminal. The dome above it in the ceiling is outlined with Islamic geometric patterns for more accentuation and easier perception from users on the floor, Figure 14. The huge volume of the airport and its area influenced the ease of perception of the space, as it is considered one of the largest airports worldwide, so smaller elements were needed to convey the identity characters to the users.

Figure 11.

The terminal of KFIA—Arched entrance. Source: Authors.

Figure 12.

The interior of the terminal of KFIA shows the use of arches and motifs. Source: Authors.

Figure 13.

Interior with Islamic geometric patterns on the ceiling, KFIA. Source: Authors.

Figure 14.

Octagonal fountain and dome above, KFIA. Source: Authors.

Islamic geometric patterns decorate the false ceilings along with the geometric tiling cuts that can be perceived from different corners in the airport to enhance the reference feeling, Figure 15 and Figure 16. As a first glimpse of the region’s traditional art, the walls are adorned with paintings, including vibrant calligraphy, traditional patterns, and views, Figure 17. The carpets also have both geometrical patterns and contemporary lines to accentuate the blend between the old and the modern, Figure 18.

Figure 15.

Islamic geometric patterns decorating the false ceilings, KFIA. Source: Authors.

Figure 16.

Ceiling and floor tiling with traditional geometric patterns, KFIA. Source: Authors.

Figure 17.

Paintings of calligraphy, KFIA. Source: Authors.

Figure 18.

Carpets with traditional patterns, KFIA. Source: Authors.

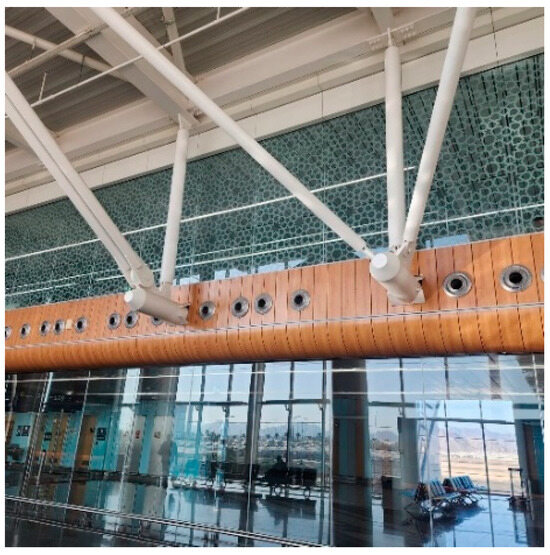

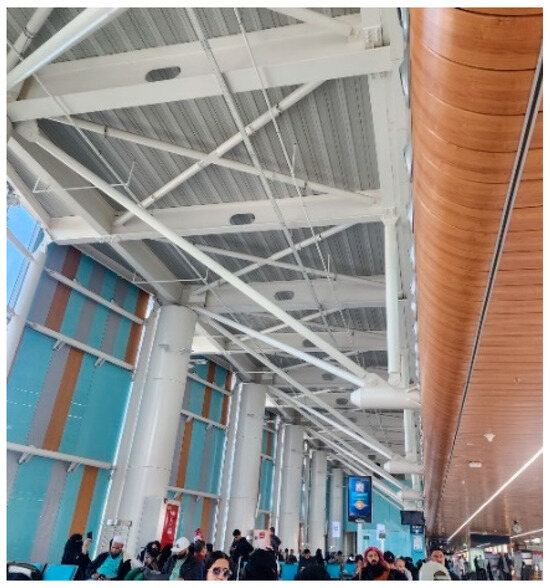

2.1.3. Prince Mohammad Bin Abdulaziz International Airport, PMAIA

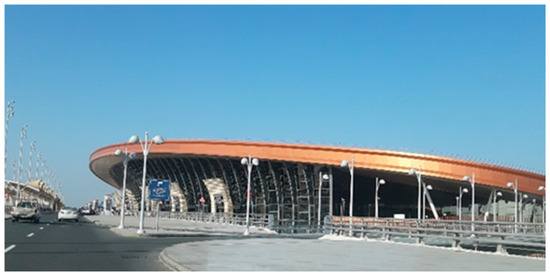

GMW Architects constructed the city’s airport with religious significance, and it was inaugurated in 2015. The main concept is picturing the dense palm tree fields in Al Madinah with their overlapping leaves and penetrating light [40]. Users’ first impression of the airport terminal is created when they are welcomed by the abstracted palm tree columns that support the floating canopy at the entrance façade. The top of the columns is covered in a flat surface, so the feeling of the dense field of palm trees with the anticipated interplay of light and shade is not there, Figure 19 and Figure 20.

Figure 19.

PMAIA entrance canopy held by the abstracted palm columns. Source: Authors.

Figure 20.

Wireframed octagonal columns. Source: Authors.

The grand canopy is the most remarkable element of the entire design and was created using columns of an octagonal group of radiating, intersecting, and concentric lines. It uses Islamic geometry patterns in abstracting the palm trees. These columns continue inside the airport to carry the visible sheets of the roof, Figure 21. Other than the occasional Islamic patterns on a wall or a glass partition, the airport’s interior design lacks any other noteworthy elements. Daylight flows into the interiors through the sleek glass façades surrounding the entire building. Between the modules of the columns, a small square of skylight appears to provide some daylight, Figure 21. A bridge covered in brown wooden sheets from below adds some warmth to the interior’s white, high-tech trusses, which are left to carry the wooden bridge with its circular openings, Figure 22 and Figure 23. Travelers’ attention is not captured by any artwork, water features, or interior plantation while they are waiting or walking through the terminal.

Figure 21.

Square skylights between column tops, PMAIA. Source: Authors.

Figure 22.

Patterns on glass and trusses holding the wooden bridge, PMAIA. Source: Authors.

Figure 23.

Trusses holding the wooden bridge, PMAIA. Source: Authors.

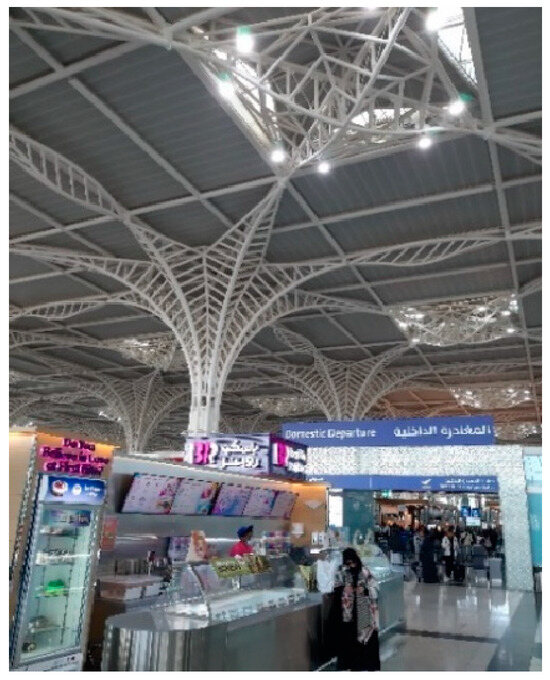

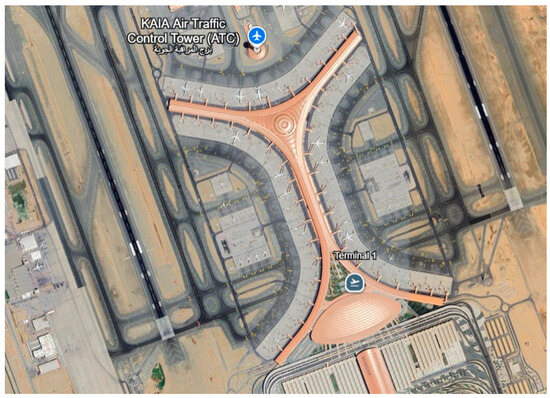

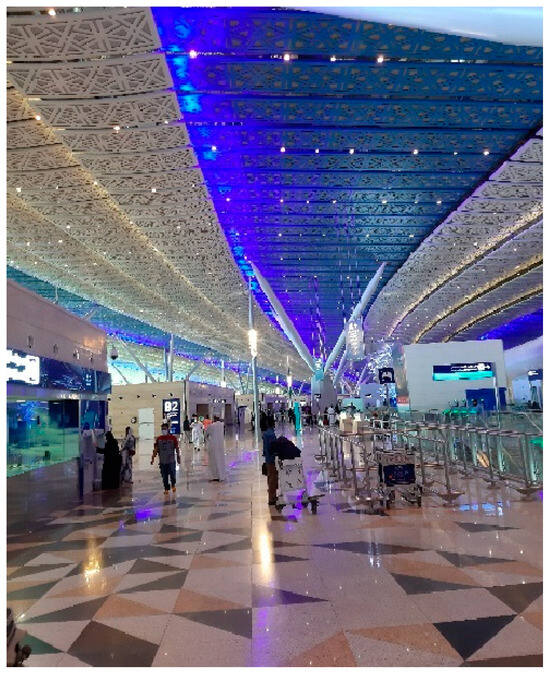

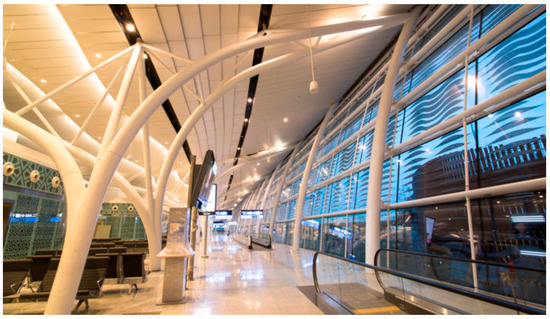

2.1.4. King Abdulaziz International Airport, KAIA

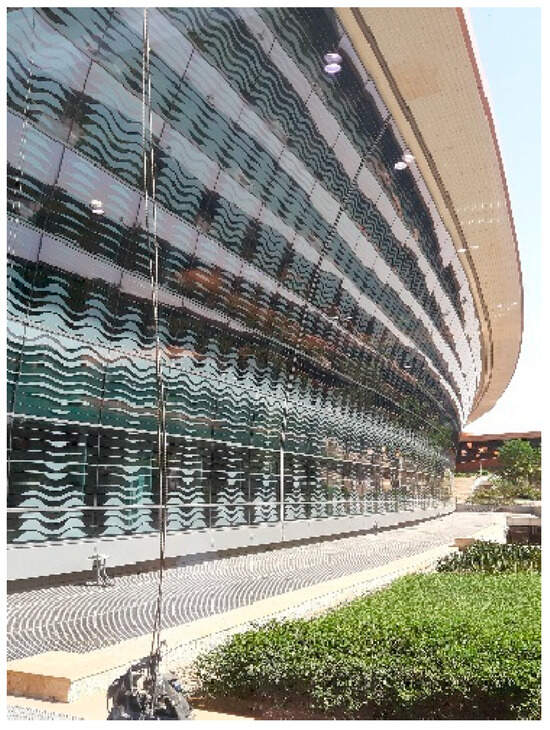

Inaugurated between 2019 and 2021, the airport of the city of Jeddah is the gateway leading to the holiest city in the Islamic religion, the city of Makkah. It was designed by Atkins and Pascall & Watson Architects [41]. While approaching the airport from the high bridges surrounding it, the stunning undulating red copper enveloping the airport’s curved masses, with the natural palm trees enclosed in between, catches the eyes, giving different metaphors connected to the context of the airport, such as the organic dunes, the waves of the sea, or a sea creature with its gills surrounded by the wavy car parking-shading canopies. The airport’s mass is four back-to-back curves enclosing a garden to incorporate the exterior landscape in the interior design and to allow for perceiving the exterior façades from the interior lounges in a holistic manner, Figure 24.

The first impression when standing in front of the airport’s façades is a contemporary dynamic atmosphere emitted from the mirrored glass façades with its vertical divisions and simple curved protruding gate, Figure 25.

Figure 24.

Stunning copper sheets enveloping the four back-to-back bracket mass enclosing gardens, source: https://www.google.com/maps/@21.6670858,39.1612563,2510m/data=!3m1!1e3?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MDQwOC4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D, accessed on 13 March 2025.

Figure 25.

Gentle red copper curve with glass façades underneath with its vertical divisions and simple curved protruding gate in KAIA. Source: Authors.

Upon entering the terminal, passengers face three entities that merge to form the identity of the airport. The first is the Islamic patterns engraved on walls and furniture, forming the layered false ceilings, and abstracted on the floors’ marble cuts, Figure 26.

Figure 26.

Islamic patterns on false ceilings and abstracted on the floors’ marble cuts, KAIA. Source: Authors.

The second entity is the coastal identity of Jeddah, the host city of the airport, with a huge aquarium that extends to two floors in height and can be seen from different points in the airport, attracting passengers and creating a soothing, playful experience among them, Figure 27. The glass façades have wavy patterns imprinted on them, Figure 28. While heading to the waiting lounges, different artifacts grab passengers’ attention, such as hanging paper planes with different destinations written on them and the printed waves on the glass overlooking the huge exterior garden with a mix of a contemporary landscape and palm trees organized in harmony to make the long passages easier for the passenger, Figure 29. The third entity that controls the passenger’s perception is the contemporary atmosphere that envelopes the entire airport, whether its exterior façades or interior settings, especially in the curved branched white columns or the modern furniture distributed in different places, Figure 30.

Figure 27.

Aquarium extending two floors in height, KAIA. Source: Authors.

Figure 28.

Glass façades have wavey patterns imprinted on them, KAIA. Source: Authors.

Figure 29.

Contemporary landscape and palm trees in the court, perceived from inside, KAIA, Source: Authors.

Figure 30.

Curved, branched white columns, KAIA. Source: Authors.

It was noticed that the interior design of the consumer spaces in all airports adopted globalized features such as technology integration, cutting-edge materials, and fluidity of design with different percentages, forgetting all about identity and heritage indicators that, if used, would have generated a memorable artistic user experience.

3. Questionnaire Results and Analysis

A structured questionnaire was developed to understand travelers’ perceptions of identity indicators in the predetermined airport terminals. These perceptions include their experiences, emotions, and vision for development to create a sense of interaction with space. The questionnaire aims to establish if the identity indicators in the different airports were noticed by the travelers, their experiences and emotions when seeing them, and their impacts on the travelers’ sense of the space, leading it to be redefined as a place. The structured questionnaire was initially tested on 10 respondents as a pilot study to find out if it was clear enough and well understood and if it needed any modifications, especially since it was intended to be self-administrated. Hence, the structured, self-administered, web-based questionnaire with multiple-choice and rating scale questions was distributed digitally. The questionnaire was deactivated after receiving 100 online responses. It included four sections. The first was the demographic questions section. The demographics of the respondents are shown in the table below, Table 2.

Table 2.

The demographic statistics of the respondents, Source: Authors from questionnaire.

Table 2.

The demographic statistics of the respondents, Source: Authors from questionnaire.

| Respondents’ Demographics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 20–30 | 30–40 | 40–50 | 50–60 | Above 60 |

| Percentage (%) | 20 | 43 | 18 | 13 | 6 |

| Gender (%) | Male 38% | Female 62% | |||

| Nationality (%) | Saudi 81% | Non-Saudi 19% | |||

| Frequency of Travel | Once/year 4% | Twice/year 57% | Three or more times/year 39% | ||

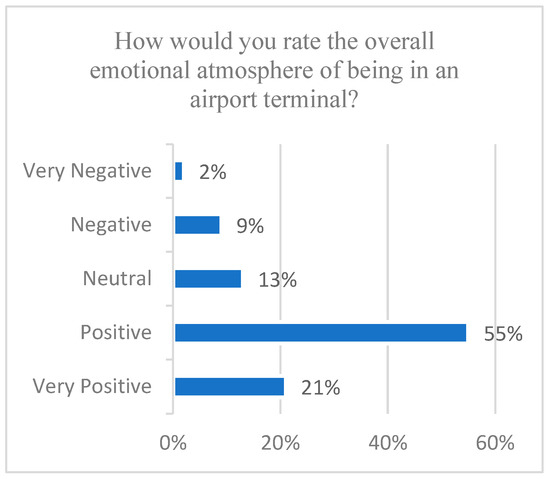

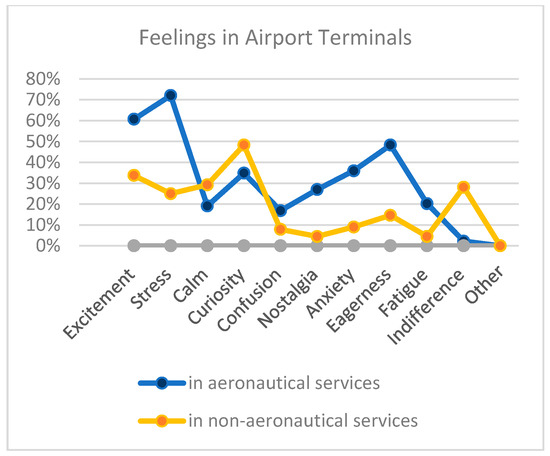

The second section included questions about the experiences in airports in general. It was important to know the overall emotional atmosphere of being in an airport terminal, which was noted as either very positive or positive with a total percentage of 76%, Figure 31. This indicates that airport terminals are spaces that have an impact on their users and that they are eligible to be elevated into places. Passengers have different feelings in the airport according to the zone they are present in. In aeronautical spaces, passengers’ feelings varied between excitement (61%) and stress (72%), while their feelings in the non-aeronautical spaces varied between curiosity (48%) and excitement (34%) or indifference (28%), as shown in Figure 32. This indicates that non-aeronautical spaces, which include the consumer spaces such as waiting lounges, duty-free shops, retail, food courts, and food booths, are the spaces where passengers will need something to change the mood of their trips away from the stress they felt in aeronautical spaces.

Figure 31.

Analysis of responses to rating the emotional experience in an airport terminal question. Source: Authors, from the questionnaire analysis.

Figure 32.

Comparison between feelings of passengers in aeronautical spaces and and non-aeronautical spaces. Source: Authors, from the questionnaire analysis.

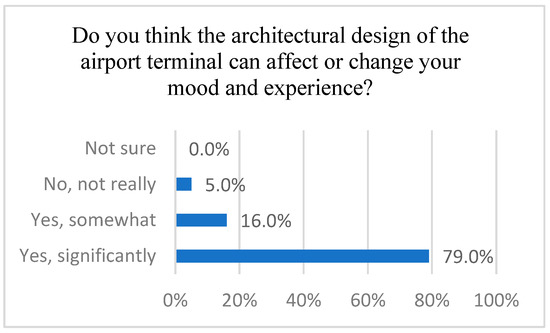

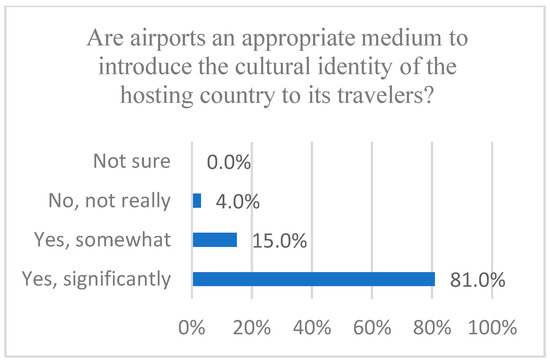

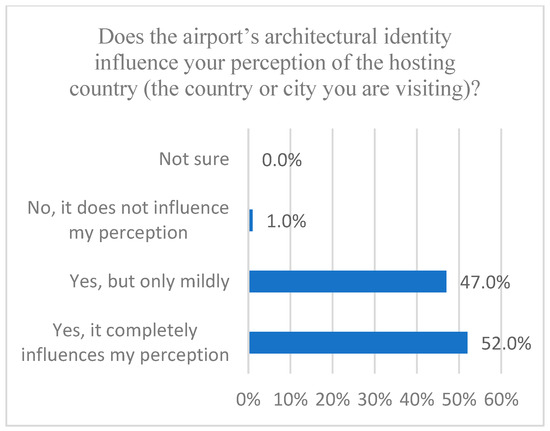

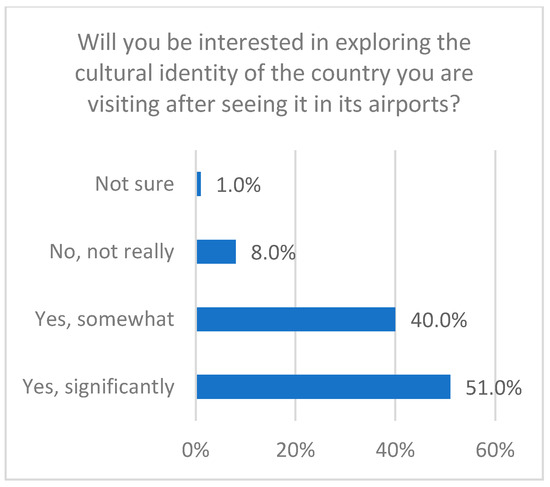

Most participants (95%) believed that the architectural design of the airport terminal has an effect and can change the passenger’s mood and experience, Figure 33. They even agree (96%) that an airport terminal is an appropriate medium to introduce the cultural identity of the host country to its travelers, Figure 34, and that it influences the passenger’s perception of the host country significantly (52%) or mildly (47%), Figure 35, and that they will be significantly interested (51%) or somewhat interested (40%) in exploring the cultural identity of the host country after seeing it in its airports, Figure 36.

Figure 33.

Answers to question about the effect of the architectural design of airport terminals on passengers mood. Source: Authors, from the questionnaire analysis.

Figure 34.

Source: Answers to question about the appropriatness of airport terminals to introduce the cultural identity of the hosting country. Source: Authors, from the questionnaire analysis.

Figure 35.

Answers to question about the influence of airport terminals on the respondents perception of the hosting country. Source: Authors from the questionnaire analysis.

Figure 36.

Answers to question about the respondents interest in exploring the cultural identity of hosting country. Source: Authors, from the questionnaire analysis.

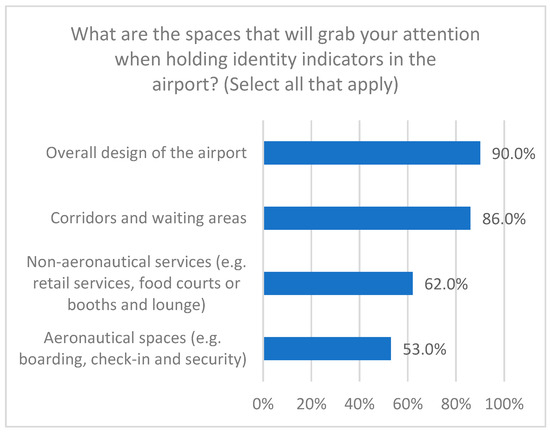

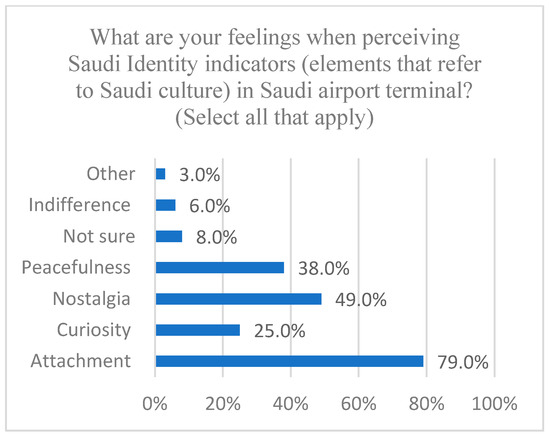

When the participants were asked about the spaces that would grab their attention when assessing identity indicators in the airport, most participants in the questionnaire (89%) stated that the overall design of the airport would grab their attention, followed by the waiting lounges (86%), Figure 37. When asked about the respondents’ feelings when perceiving the Saudi identity indicators in the airport terminals, their feelings varied between attachment to the place (79%), nostalgia (49%), and peacefulness (38%) among other feelings such as pride, sense of belonging and happiness for the impression the tourist gets from perceiving such indicators, Figure 38.

Figure 37.

Answers to question about which spaces in airport terminals will grab the respondents attention if holding identity indicators. Source: Authors, from the questionnaire analysis.

Figure 38.

Answers to question about the respondents feelings when perceiving identity indicators in airport terminals. Source: Authors, from the questionnaire analysis.

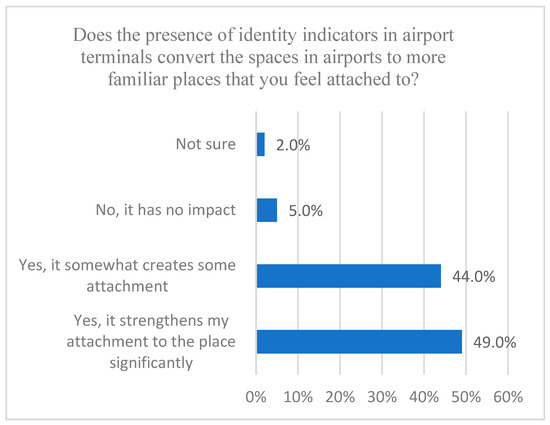

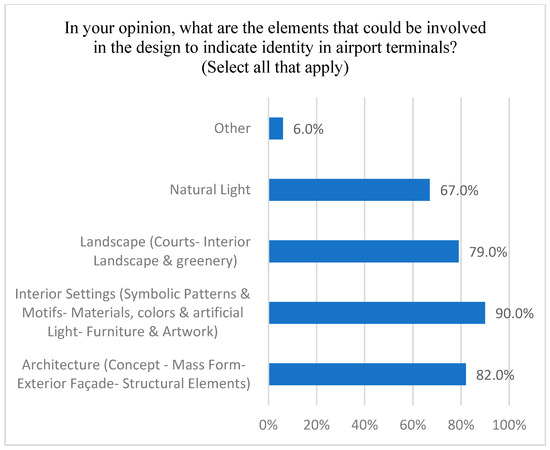

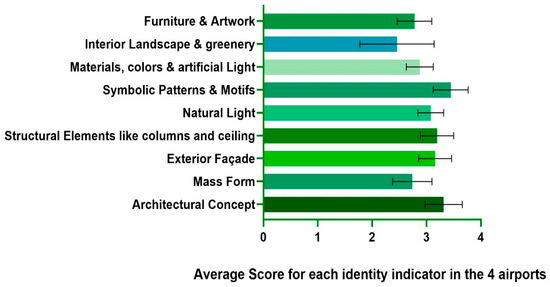

For another question about whether the presence of identity indicators makes the respondent more attached to the place, the answers were ‘yes, significantly’ (49%) and ‘yes, somewhat’ (44%), Figure 39. This shows how effective identity indicator elements can contribute to developing a sense of attachment to the space, which indicates the readiness of the respondents to interact with it. The respondents chose the ‘Interior Settings’ (Symbolic Patterns and Motifs—Materials’ Colors and Artificial Light—Furniture and Artwork) to be the highest impactful identity indicators (90%) and the ‘Architecture’ (Concept—Mass Form—Exterior Façade—Structural Elements) to be the second influential indicator with (82%) of the respondents choosing it, followed by landscape (Courts—Interior Landscape and Greenery) (79%), and natural light (67%). Other indicators were the sign systems, the sound of internal microphones, and the local food booths, shown in Figure 40.

Figure 39.

Answers to question about if identity indicators increase the familiarity of respondents to the spaces in airport terminals. Source: Authors, from the questionnaire analysis.

Figure 40.

Answers to a question about the elements of design that could be used as identity indicators in airport terminals. Source: Authors, from the questionnaire analysis.

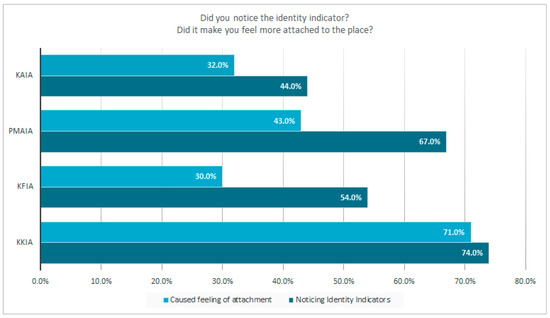

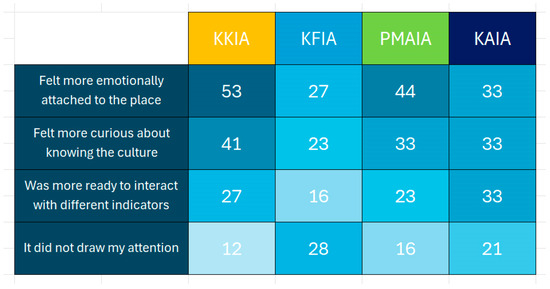

In the third section, specific questions about the four pre-set case studies were asked, starting with whether the identity indicators were noticed or not and if they had any impact on the respondents. The answers were reported as shown in Figure 41, revealing that they were noticed by the majority and had different levels of impact on them. King Khalid Airport came as the highest in noticing the identity indicators and the impact on the respondents, followed by King Fahad Airport. PMAIA’s identity indicators were noticed by 67% of the respondents but had an impact on fewer respondents. This might be due to the presence of the abstracted palms as columns at the entrance façade and then the disappearance of other identity indicators throughout the journey inside the airport. The identity indicators in KAIA were noticed by fewer respondents than any other airport in the study. This might be due to the coastal identity indicators that were used, such as the aquarium, printed waves on glass, white inclined branched columns, and landscape, which were seen as globalized features that do not refer to Jeddah only.

Figure 41.

A comparison between the percentages of respondents noticing the identity indicators in airports terminals and its impact on their attachment to the place. Source: Authors, from the questionnaire analysis.

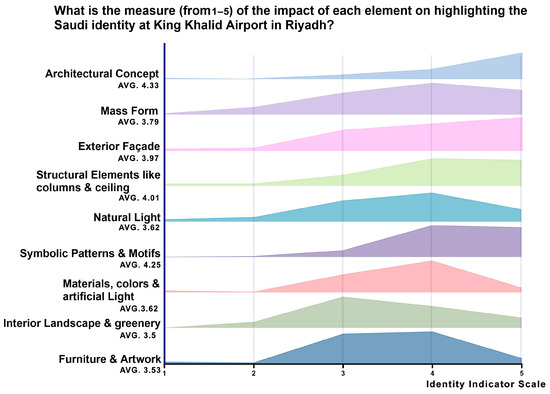

In the following section, a summary of identity indicators in every airport is given Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 and then compared by the weights of the impact of each identity indicator on the respondents, Figure 42, Figure 43, Figure 44 and Figure 45. This is important to understand the impact of each identity indicator on the airport visitors and if there is any kind of significance for one indicator over the others.

Table 3.

Summary of identity indicators in King Khalid International Airport. Source: Authors.

Table 3.

Summary of identity indicators in King Khalid International Airport. Source: Authors.

| Identity Indicators in King Khaled International Airport (KKIA) as Previously Analyzed | ||

|---|---|---|

| Architectural Intent | Concept | Inspired by the oasis in the desert, palm trees, and Najdi traditional architecture. |

| Mass Form | Geometrical triangular and hexagonal patterns with arches create the mass form. | |

| Exterior Façades | Glass façades connect the exteriors with the interiors with no identity references except the multi-level ceiling that continues to shape the façades’ morphology. | |

| Structural Elements | Multi-level roof with triangular openings as a clerestory creating an abstracted palm tree in the interior. | |

| Interior Settings | Symbolic Patterns | Triangular openings and floor tiling are inspired by traditional Najdi architecture. The arched multi-level roof alludes to the abstracted palm as a contextual identity. |

| Materials’ Color and Light | The impression of sitting in an oasis with light penetrating through the shade of palm tree leaves is created by the multi-level roof. The interior materials’ beige tones enhance the sense of sandy dunes. | |

| Interior Landscape | Fountains and flower boxes in Islamic geometric patterns. | |

| Artwork | Traditional Najdi paintings and calligraphy. | |

In King Khalid international Airport (KKIA), and according to the questionnaire response analysis, the architectural concept was the most apparent indicator to the respondents; the mass’s identity was less clear as it was not perceived by many of them, but the façades were more apparent, and the interpretation of the concept in the columns and ceiling was the most recognized. The patterns and motifs were the most impactful interior elements, followed by the materials’ colors and artificial light. The landscape was less significant than expected due to its presence at the entrance of the airport, where excitement, stress, and confusion were the most dominant feelings among passengers, as shown in Figure 42.

Figure 42.

Impact of Identity Indicators in KKIA. Source: Authors, from the questionnaire analysis.

As for the identity indicators in the King Fahad International Airport, they are summarized in the Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of identity indicators in King Fahad International Airport Source: Authors.

Table 4.

Summary of identity indicators in King Fahad International Airport Source: Authors.

| Identity Indicators at King Fahd International Airport (KFIA) as Previously Analyzed | ||

|---|---|---|

| Architectural Design | Concept | The airport prioritizes functionality with a blend of Islamic architectural features and sleek modern façades representing Saudi Arabia’s history and aspirations for modernization. |

| Mass Form | The mass has no distinct identity feature except for the dome and the two octagonal skylights that cannot be perceived from the outside. | |

| Exterior Façades | Sleek glass façade with a large canopy held with columns that branch into four branches forming arches as an arcade that welcomes cars in front of the building. | |

| Structural Elements | Columns at the façade with four beams act as branches connecting the exterior with the interior. Other columns in the interior are simple with no identity characteristics. | |

| Interior Settings | Symbolic patterns | Floor tiling cuts are inspired by traditional Islamic architecture. |

| Materials’ color and light | Hues of beige color in marble refer to desert colors and natural stone. Floor tiling cut into Islamic geometric patterns. No natural light is perceived inside the airport due to its huge size. | |

| Interior Landscape | Fountains and flower boxes in Islamic geometric patterns. | |

| Artwork | Traditional Islamic paintings, carpet colors and drawings, mosaics, and calligraphy designed by local artists. | |

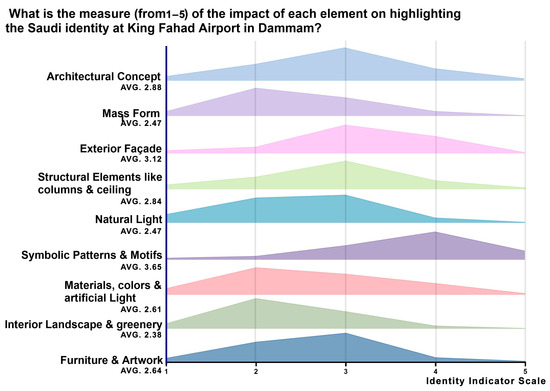

According to the response to the questionnaire analysis, in King Fahad International Airport (KFIA), the architectural concept as an identity indicator was not as impactful for the respondents as expected. The exterior façades are perceived more than the mass. The most significant identity indicator was the symbolic patterns, most of which are present in the non-aeronautical spaces. Despite the huge fountain and greenery with the Islamic pattern implying the conceptual identity of the terminal, it was not recognized by the respondents. This might be due to its presence at the entrance of the airport in the excitement, stress, and confusion zone, Figure 43.

Figure 43.

Impact of Identity Indicators in KFIA. Source: Authors, from the questionnaire analysis.

The identity indicators in Prince Mohamed Bin Abdulaziz International Airport in Almadinah Almonawarah (PMAIA) are summarized in the Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of identity indicators in Prince Mohamed Bin Abdulaziz International Airport Source: Authors.

Table 5.

Summary of identity indicators in Prince Mohamed Bin Abdulaziz International Airport Source: Authors.

| Identity Indicators at Prince Mohammad Bin Abdulaziz International Airport (PMAIA) as Previously Analyzed | ||

|---|---|---|

| Architectural Design | Concept | The airport’s main concept was creating a merge between the Islamic geometric patterns and the palm tree fields, recognizing the city’s landscape. This led to the design of columns resembling palm trees in abstract geometric patterns. |

| Mass Form | The mass is a clear rectangle with a flat roof and glass façades. | |

| Exterior Façades | Sleek glass façade with a large canopy held with abstracted palm columns. | |

| Structural Elements | Columns are inspired in their design by the abstracted palm trees formed from interwoven steel bars carrying a flat roof. White steel bars and bolts are left exposed. | |

| Interior Settings | Symbolic Patterns | Floor tiling cuts are plain, with no figurative patterns except in few spaces. Some arches and woodwork are present in special spaces in the airport such as the international duty-free section, restaurants, or lounges. |

| Materials’ Color and Light | Daylight penetrates the terminal from the glass façades enveloping the rectangular mass. Squares of artificial light between the caps of the columns give more plain light to the hall. White colors dominate the terminal interiors with a wooden brown interior bridge and patterned transparent glass. The seats are silver and metallic. | |

| Interior Landscape | No interior landscaping was seen. | |

| Artwork | Some geometrical patterned partitions are present in lounges, reflecting Islamic art. | |

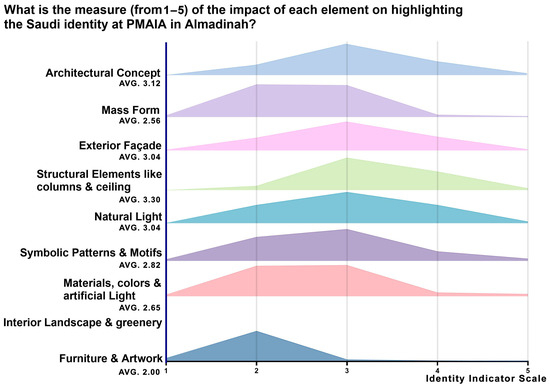

In Prince Mohamed bin Abdulaziz International airport (PMAIA), and according to the responses to the questionnaire, the concept is widely noticed in its implementation in the structural element. This raised the impact of both indicators followed by the natural light penetrating the ceiling between the abstracted columns integrated with the geometrical Islamic patterns holding the ceiling. Other interior identity indicators had less impact as they were marginal in the design, Figure 44.

Figure 44.

Impact of Identity Indicators in PMAIA. Source: Authors, from the questionnaire analysis.

The identity indicators in King Abdulaziz International Airport in Jaddah (KAIA) are summarized in the Table 6.

Table 6.

Summary of identity indicators in King Abdulaziz International Airport. Source: Authors.

Table 6.

Summary of identity indicators in King Abdulaziz International Airport. Source: Authors.

| Identity Indicators at King Abdul-Aziz International Airport (KAIA) as Previously Analyzed | ||

|---|---|---|

| Architectural Design | Concept | The airport draws its ideas from its coastal context, Islamic patterns, and Hijazi architecture in a contemporary vision. |

| Mass Form | The mass is formed from four back-to-back brackets, with links in between allowing for interior spaces forming courts integrating with the mass. | |

| Exterior Façades | Printed glass façades. | |

| Structural Elements | Columns are either thick at the entrance or white, branched columns carrying layered patterned false ceilings according to the zone. | |

| Interior Settings | Symbolic patterns | The floor tiling has different hues of triangular patterns in gradients with solid colors. |

| Materials’ Color and Light | Hues of beige and blues dominate the interiors, referring to the coastal identity of Jeddah. Light penetrates from the glass façades or from between the layered, patterned false ceiling. | |

| Interior Landscape | A huge aquarium acts as a focal point for all passengers to watch and grab photos beside. Regularly distributed palm trees are present in passages referring to the prevailing local greenery. | |

| Artwork | Traditional Islamic geometric patterns cover false ceilings, walls, and furniture. | |

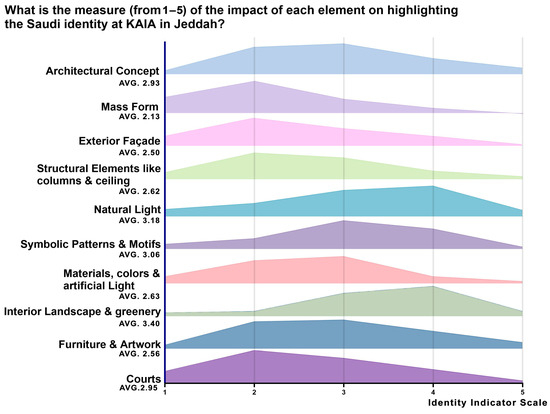

According tot the questionnaire analysis, in King Abdulaziz International airport (KAIA), the concept and its elements had less impact as identity indicators due to the globalized features that characterize them. The form of the mass introduced the integration of natural light from the walls and the courts with its palm trees that could be perceived from the interiors. The interior landscape, along with the symbolic patterns, were impactful when brought together, Figure 45.

Figure 45.

Impact of Identity Indicators in KAIA. Source: Authors, from the questionnaire analysis.

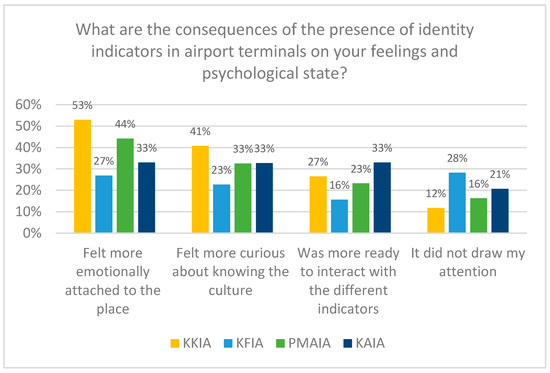

A question was presented about the consequences of the presence of identity indicators in airport terminals on the feelings and psychological state of the respondents, with them choosing all that apply. The answers are shown in Figure 46 and Figure 47.

Figure 46.

Source: Authors, from the questionnaire analysis.

Figure 47.

Heatmap of the impact of identity indicators on respondents in the four airports. Source: Authors, from the questionnaire analysis.

KKIA identity indicators were more impactful in the emotional attachment than the other terminals as it has the most complete user experience in the overall design, whether in the concept, columns’ design, patterns, natural light, interior greenery, or all elements contributing to the oasis feeling intended by the designer. The abstracted palms at the entrance of PMAIA had an emotional impact on the respondents as well. The interaction with the aquarium in KAIA was the most apparent in the interaction with the indicators. This gives the impression that some identity indicators should be dynamic and ready for interaction with the passengers, not only shown. This might justify the high percentage of “no effect” that the identity indicators had in KFIA, as they were not integrated with the design or the users’ experience. Even the main greenery and fountain designed in an Islamic pattern with a skylight was not perceived due to its presence in the aeronautical space and its huge scale, making it difficult to be fully perceived and experienced, Figure 47 and Figure 48

To understand the most significant identity indicator in impacting the respondents in the different airports, the identity indicators in the four airports were compared using one-way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparisons test Figure 48. The graph and statistical analysis show no significant difference between the identity indicators, indicating that all of them are of similar importance and impact.

Figure 48.

Average score for each identity indicator in the 4 airports ± standard deviation. The analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparisons test and presented using GraphPad Prism V.10.

In a question about the most suitable spaces in airports for implementing identity indicators in their designs (Select all that apply), the respondents chose most of the spaces that lie in the non-aeronautical spaces after finalizing the procedures of traveling, as shown in Figure 49.

Figure 49.

The weights of the importance of different spaces in applying identity iindicators along the passengers’ journey in the airport. Source: Authors, from the questionnaire analysis.

The respondents chose the retail spaces, duty-free spaces, waiting areas, and passageways as the most favorable spaces for having an identity indicator experience, Figure 49. This could be correlated with Figure 37, which favors the non-aeronautical spaces over the aeronautical ones, and Figure 32, which shows that the levels of stress and eagerness in these areas are less than in other areas, which allows passengers to enjoy their experiences.

4. Conclusions

This research verified its main hypothesis that “identity indicators can redefine spaces in airport terminals to be ‘places’ creating new user experience”. When a space in an airport terminal is described, the physical essence of the space, whether closed or open, and its functionality is explained, but its impact on its users is left out. To transform this space into a place, it has to acquire significance that gives it a personality to be recognized among other spaces. Airport terminals are fertile land ready to be transformed from a globalized ‘non-place’ into a unique representative ‘place’ of its host country by glocalizing its features, that is, presenting the identity of its host country by promoting identity indicators of its local heritage or culture with a modern flavor, in addition to the global features, keeping up with the latest cutting-edge technology in the field.

Picturing or modeling heritage elements or cultural aspects as identity indicators provides many layers of meanings to the place, creating a kind of attachment between it and the users, enabling them to engage and interact. Thereafter, the place will be recognized by its identity indicator. This recognition has many benefits, among which is acting as sustainable architectural marketing campaigns for their respective cities and countries.

Architectural identity can be represented in many forms; it can be historical or traditional or follow the identity of the context to carry the features of the location it belongs to. It can be implemented in the overall design of the terminal and its architectural concept, in interior or exterior landscape design, engraved patterns on walls or pieces of furniture, handrails or floors, hung artwork, and free-standing sculptures. In all cases, a place is created by offering a unique, impressive, and memorable experience to the user in addition to correct functionality and smooth circulation.

According to the questionnaire held to understand the impact of identity indicators on the passengers in the identified Saudi airports built throughout the interval of 40 years, the most impressive airport in terms of identity indicators was KKIA, where the entire concept mimicked the context as an oasis for tired travelers amid the desert. In KFIA, the architect tried to modernize the identity indicators, so the elements were dispersed with no fixed identity. In addition, the large area of the airport made it challenging to perceive the identity indicators as a whole. As a result, the airport lacked a main theme or direction. The abstract palm tree columns at the PMAIA’s entrance, and their continuation throughout the airport, with modular skylights positioned between the columns, established a clear and prominent concept that users could understand and provided the terminal with a distinctive identity. As for KAIA, the study showed that the coastal identity was not recognized as an identity indicator due to its globality. Despite that, the aquarium attracted the passengers and created a desirable interactive experience. However, the passengers were less impacted by the more apparent and noticeable Islamic identity indicators as they were merged with modernized contemporary design features.

Identity indicators create a sensory experience in airport terminals, creating a relationship between the users/travelers and the place. Emotional attachment with identity indicators is dynamic and divergent according to different variables such as their place in the airport and the time of interaction within the traveling procedures during a trip. The presence of a dominant identity indicator that is eye-catching and interactive in the design to attract attention and affirm the identity is more impactful than having many dispersed themes of identity indicators distributed without a continuous scenario that engages passengers. On the other hand, presenting historical or traditional references as pasted elements on contemporary furniture might deprive designs of the required identity essence if not handled deeply.

Consumer spaces in airports, such as food courts and duty-free zones, could be viewed as opportunities to brand the cities in which they are located. Instead of utilizing globalized features to articulate these spaces, it is preferred to enhance identity indicators by designing them to resemble/visualize various traditional zones that are considered heritage, cultural, and touristic landmarks in the cities. This enhances the mental images the passenger conjures up in their mind, generating a narrative bond to the space, which is turned into a place and fosters a psychological and sustainable emotional connection with the city, promoting the city’s tourism and economic advancement. This could be achieved by using local materials and envisioning and depicting vernacular scenery and buildings in the interior design of the spaces.

Having interior courts in airport terminals connects passengers with the outdoor landscape and building’s façades to enhance their attachment to the exterior form of the airport, showing the concepts reflected in the façades and completing the image of the airport terminal’s mass as a landmark. At the same time, natural light has a healing and stress-relieving effect. It connects the travelers with the exterior world and might emphasize the identity indicator’s role with the shade and shadows it creates, such as its effect in KKIA and PMAIA.

Using identity indicators and mimicking heritage or touristic landmarks of the host country in the consumers’ zones in the airport terminals allows users to recognize the multi-dimensional nature of their experience in a place with its experiential, social, cultural, and aesthetic dimensions for better social encounters and interaction with the place, increasing users’ attachment to the place and likely serving as a catalyst in fostering the expected economic benefits.

It is recommended to introduce identity indicators to the entire airport design and to focus on the focal points, interior landscape, and interactive elements of artworks in non-aeronautical spaces, where the stress level decreases, and the curiosity emotions increase after finalizing the traveling procedures. This will make them more enjoyable and will allow them to have the expected impact on the passengers. All identity indicators are significant, with neither one prevailing over the other. It is the handling of the indicator and the level of its ability to be interactive that favors one over the other.

Using identity indicators in airport terminals is more of a need than a luxury, as it creates a sense of place that enhances the overall traveling experience and leaves a sustainable, memorable impression on passengers. The synergy between functionality and identity indicators in designing airport terminal spaces fosters the holistic experience that prioritizes user satisfaction and enhances the host country’s image and character.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.A.A.E.E. and H.M.N.A.; Methodology, Z.A.A.E.E.; Formal analysis, Z.A.A.E.E., H.M.N.A. and B.M.A.; Investigation, Z.A.A.E.E., H.M.N.A. and B.M.A.; Resources, H.M.N.A.; Data curation, Z.A.A.E.E., H.M.N.A. and B.M.A.; Writing—original draft, Z.A.A.E.E.; Writing—review & editing, Z.A.A.E.E. and H.M.N.A.; Visualization, H.M.N.A.; Supervision, H.M.N.A. and B.M.A.; Project administration, H.M.N.A. and B.M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zougheib, R.G. The Planning and Design of Terminal Buildings: A Case Study of Beirut International Airport. Art Archit. J. 2023, 4, 83–119. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Gayed, A.H.; Hassan, T.H.; Abdou, A.H.; Abdelmoaty, M.A.; Saleh, M.; Salem, A.E. Travelers’ Subjective Well-Being as an Environmental Practice: Do Airport Buildings’ Eco-Design, Brand Engagement, and Brand Experience Matter? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massey, D. Reading Human Geography. In A Global Sense of Place; Arnold: London, UK, 1997; pp. 315–323. [Google Scholar]

- Seamon, D.; Sowers, J. Review of Place and Placelessness, Edward Relph. In Key Texts in Human Geography; SAGE: London, UK, 2008; pp. 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hathloul, S.; Mughal, M.A. Urban Growth Management—The Saudi Experience. Habitat Int. 2004, 28, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscatelli, M. Rethinking the Heritage through a Modern and Contemporary Reinterpretation of Traditional Najd Architecture, Cultural Continuity in Riyadh. Buildings 2023, 13, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmayati, Y.; Alghunaim, J. Enhancing city authenticity through humanitarian architecture: A synergy of design and identity, case study, Al-Diriyah, Saudi Arabia. J. City Brand. Authent. 2024, 1, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hathloul, S.; Mughal, M.A. Creating identity in new communities: Case studies from Saudi Arabia. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1999, 44, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazette, T.G. How Vision 2030 Is Shaping Saudi Arabia’s Architectural Landscape. GA Design Group. 15 February 2025. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/how-vision-2030-shaping-saudi-arabias-architectural-landscape-plhoc?trk=news-guest_share-article (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Almakaty, S.S. Preserving and Promoting Saudi Heritage Nationally and Globally: The Role of the Saudi Heritage Commission. J. Ecohumanism 2025, 4, 1207–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, A. Saudi Arabia Launches Design Guidelines to Preserve Country’s “Distinctive Architectural Styles”. Dezeen, 27 March 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Shen, Y.; Yang, G. Does the local government multi-objective competition intensify the transfer of polluting industries in the Yangtze River Economic Belt? Environ. Res. 2024, 245, 118074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senderos, M.; Sagarna, M.; Otaduy, J.P.; Mora, F. Globalization and Architecture: Urban Homogenization and Challenges for Unprotected Heritage. The Case of Postmodern Buildings with Complex Geometric Shapes in the Ensanche of San Sebastián. Buildings 2025, 15, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, P. Identity, Place and Human experience. Archit. Des. 2012, 82, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, M.; Hanks, L.; Qi, W. Is it possible to define architectural identity more objectively? In Cities’ Vocabularies: The Influences and Formations; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Noobanjong, K. The Passenger Terminal at Suvarnabhumi International Airport and Thai Identity in the Midst of Globalization Era. J. Archit./Plan. Res. Stud. (JARS) 2018, 6, 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Akca, Y.B.Ö.; Erdogan, E. Struggle of airport terminals to establish a relationship with place: The case of esenboğa airport. In ICONARCH—International Congress of Architecture and Planning 2017; Konya Technical University Faculty of Architecture and Design: Konya, Turkey, 2017; pp. 741–752. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Zaidi, B.M.; Khalil, S.M. Globalization and its impact on the local identity of architecture. Period. Eng. Nat. Sci. 2023, 11, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Pisonero, R. High-Speed Rail Stations and Airports: Symbolic Infrastructures of Mobility as “Places of Globalisation”. Mitteilungen Osterr. Geogr. 2022, 1, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majerska-Pałubicka, B. Architecture vs. Globalization. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 960, 022078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambe, N.; Dongre, A. Contextualism: An Approach To Achieve Architectural Identity And Continuity. Int. J. Innov. Res. Adv. Stud. (IJIRAS) 2016, 3, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Alzahrani, A. Understanding the role of architectural identity in forming contemporary architecture in Saudi Arabia. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 11715–11736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Strijker, D.; Wu, Q. Place Identity: How Far Have We Come in Exploring Its Meanings? Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auge, M. Non-Places Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity; Verso: London, UK, 1997; pp. 77–78. [Google Scholar]

- Soltani, S.; Kirci, N. Phenomenology and Space in Architecture: Experience, Sensation. Int. J. Archit. Eng. Technol. 2019, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Park, J.W.; Choi, Y.J. A Study on the Effects of Waiting Time for Airport Security Screening Service on Passengers’ Emotional Responses and Airport Image. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, S.F.; Tanaka, T. Analyzing the Role of Identity Elements and Features of Housing in Historical and Modern Architecture in Shaping Architectural Identity: The Case of Herat City. Architecture 2023, 3, 548–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.; Mansour, Y.; Elshater, A.; Fareed, A. Assessing the Identity of Place through Its Measurable Components to Achieve Sustainable Development. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2022, 10, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavinejad, S.P. Identity in Contemporary Architecture of Saudi Arabia. J. Res. Islam. Archit. (JRIA) 2014, 1, 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Torabi, Z.; Berahman, S. Effective factors in shaping the identity of architecture. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 2013, 15, 106–113. [Google Scholar]

- Yücel, R.K.; ArabacioĞlu, F.P. Context knowledge in architecture: A systematic literature review. Megaron 2023, 18, 366–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL-Zahrani, M.A.M.; Leila, M.M.S.A. Strengthening the architectural identity of Makkah Al-Mukarramah’s buildings: An assessment of the impact of laws and regulations. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. 2022, 13, 37–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaznadar, B.M.A.; Baper, S.Y. Sustainable Continuity of Cultural Heritage: An Approach for Studying Architectural Identity Using Typo-Morphology Analysis and Perception Survey. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, D.R.; Raj, M.P. The Architecture of Airport Terminals: Gateway to a City. Creat. Space 2019, 7, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Concept, G.F. Public Furniture in the Art of Placemaking. 10 November 2021. Available online: https://www.internationalairportreview.com/whitepaper/171235/airport-furniture-in-the-art-of-placemaking/ (accessed on 7 December 2024).

- Nazura, P.; Akbar, G.; Edelenbos, J. Positioning place-making as a social process: A systematic literature review. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2021, 7, 1905920. [Google Scholar]

- Hobson, R. The Riyadh Gateway. In Aramco World Arab and Islamic Cultures and Connections; Aramco Services Company: Houston, TX, USA, 1984; Volume 35, pp. 6–19. [Google Scholar]

- Alkhabbaz, M.H. Yamasaki’s Dhahran Civil Air Terminal and the Shaping of Saudi Modernity. Prometheus 2017, 1, 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Sohail, M.S.; Al-Gahtani, A.S. Measuring service quality at King Fahd International Airport. Int. J. Serv. Stand. 2005, 1, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince Mohammed Bin Abdul Aziz International Airport New Terminal, Madinah. 20 August 2015. Available online: https://www.airport-technology.com/projects/prince-mohammed-bin-abdul-aziz-international-airport-new-terminal-madinah/?cf-view (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- King Abdulaziz International Airport. Vexcolt. 2020. Available online: https://www.vexcolt.com/project-details/kingairport/ (accessed on 25 March 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).