Abstract

The construction sector has a very high share in solving the energy demand of the world and global warming problems. Therefore, it had to increase studies on building materials-based heat storage and thermal insulation. Foam concrete is one of them, but its thermal and mechanical properties need to be improved. So, in this study, calcined marl was used as a replacement material to evaluate its thermal performance in the production of foam mortars. The aims of this study are to determine the physical, mechanical, and thermal properties of foam mortars produced with blended cements containing calcined marl at 0, 10, 30, and 50% ratios and to obtain novel and optimum design data for the foam concrete market. In conclusion, the optimum calcined marl replacement ratio is up to 30% in terms of both thermal performance and mechanical properties of foam mortars. Due to calcined marl, this study presents a foam mortar design with economic and low-carbon. And, thanks to the mixed designs of foam mortars prepared with blended cement containing novel calcined marl additive, it is observed that they improve the thermal insulation and heat storage ability of foam mortars and provide sufficient strength.

1. Introduction

The world has been focused on emission management and energy saving issues due to current findings regarding global warming and increases in energy demand [1]. The World Energy Outlook 2024 report [2] denoted that limiting global warming to 1.5 °C requires reducing emissions by 43% by 2030, 60% by 2035, and reaching net-zero in 2050. As with all sectors, the construction sector also has an important share in achieving these goals. Building life cycle processes such as material production, construction, operation, maintenance, repair, retrofitting, and demolition are responsible for both emissions and using intensive energy [3,4]. The easiest and most effectively managed of these processes is material production. The production processes of traditional cement need to be managed because they contribute to global warming (approximately 1 ton of CO2 emissions are released per 1 ton of cement) and to energy shortage at a high level (due to production using intense energy) [5,6,7]. The short-term solution to this situation is the replacement of clinkers with mineral additives [8,9]. This action also provides an increase in final product performance [10,11]. The natural marl is one of them as a clinker replacement material. It is quite novel as a cement additive in the clay group. Marl is defined as micro-calcite in nature. According to clay–limestone contents, it is named as argillaceous limestone or calcareous clay. It has high total porosity and low air permeability [12]. Also, natural marl gains high pozzolanic activity after the calcination process.

On the other hand, the efficient use of energy in buildings has necessitated the acceleration of heat storage and heat insulation studies. Meanwhile, foam concrete has been revealed as a promising candidate due to its unique thermal properties. Foam mortar, characterized by its lightweight structure and high insulation capabilities, is an optimal choice for energy-saving buildings. The foam concrete is also a material open to regulations for innovative approaches to energy-efficient building designs. Many studies in the literature satisfy expectations for improving building energy efficiency due to modified foamed mortar [11,13,14,15]. However, despite its inherent benefits, there is potential for enhancing the thermal performance of foam mortar further through various methods, including the incorporation of silica-rich additives and optimized mixing techniques [16]. For this reason, investigations on usability in terms of being an energy storage medium and the thermal insulation of foam concrete, a special class of concrete, have become increasingly remarkable [17,18,19,20,21,22]. In the literature, to further improve the thermal performance of the foam concrete, additional components with good heat transfer properties are used [16,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Therefore, the calcined marl in this study was used to determine the effect of its high silica content on the thermal performance of foamed mortars. Besides that, in this study, the use of calcined marl in foam mortars aims to improve not only thermal performance but also mechanical properties. These aims also support global environmental and energy policies. There are many studies on traditional mortar/concrete containing calcined marl blended cement in the literature [29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. However, there is no research on foam mortar/concrete containing calcined marl additive yet. The excellent properties of calcined marl (silica content, heat storage ability, pozzolanic activity, fineness, natural and novel alternative additive, high reserve) and foam concrete (lightness and thermal insulation) were combined in this study for a synergistic effect.

In summary, the aims of this study are to determine the variations in the physical, mechanical, and thermal properties of foam mortars produced by calcined marl blended cements and to obtain novelty and optimum design data for the foam concrete market. In addition to improving foam mortar’s thermal performance, this study aims to investigate novel approaches that minimize the building sector’s overall carbon footprint. Also, the use of calcined marl blended cement in foam concrete production will result in energy savings and reduced costs.

2. Materials and Methods

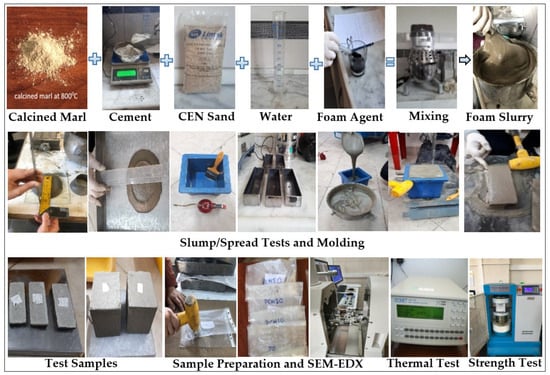

The use of different mineral additives such as fly ash, silica fume, and metakaolin has been proven to improve the properties of foam concrete by having a pozzolanic reaction, densifying the cement matrix, and improving the pore structure [36,37,38]. In this study, in order to increase the variety of mineral additives that can be used in foam concrete, calcined marl, which has very few studies on it, was used as a cement replacement material in foam concrete. The pozzolanic calcined marl was substituted for clinkers. The marl was supplied as a natural rock from Sinop/Erfelek in the north region of Türkiye. Some characteristics of natural marl are displayed in Table 1. X-ray fluorescence analysis was used to define the chemical composition of natural marl. The mineralogic–petrographic findings of the natural marl rock sample were determined with a polarizing microscope on its thin sections. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) was performed to observe the thermogram curve depending on the temperature of natural marl. The measurement parameters of the Seteram Labsys Evo brand device used in TGA have an operating temperature range of 15–1600 °C, a heating range of 5–30 °C/min, and a sensitivity of 6.7 μV/mW. In mixtures of foam mortar, Portland Cement (PC) coded as CEM I 42.5 R in compliance with EN197-1 was utilized from Ünye Cement Industry and Trade Inc., Ordu, Türkiye [39]. Some characteristics of the PC are displayed in Table 2. CEN standard sand (Limak-Trakya Cement Industry and Trade Inc., Kırklareli, Türkiye), the properties of which are defined in EN196-1 [40], was used in the production of test samples. A foaming agent (Artra Chemical Co., Ltd., Istanbul, Türkiye) obtained by the hydrolysis of animal proteins was utilized in this study. The foam agent is in liquid form. The foaming agent is a material that will not react with other materials of the mortar mixture. It solely permits the creation of air-storing bubbles. The foaming agent has a density of 1.09 ± 0.01 g/cm3. There are no detrimental minerals, salts, or organic materials at mixing water component utilized for mortar mixtures. As mold, the standard cubes (150 × 150 × 150 mm) and plates (20 × 60 × 150 mm) were used in strength and thermal performance tests, respectively. The foam mortars were stored in the molds for 2 days and in the curing tank for 26 days. The samples were 28 days old on the test day. The comparison method was used to evaluate the results. The flow chart of the production, curing, and testing processes of the test samples is given in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of natural marl.

Table 2.

Characteristics of CEM I 42.5R.

Figure 1.

Illustrative diagram of the production and test processes.

The information regarding the nomenclature of the test series is given in Table 3. The amounts of materials required to produce 1 m3 of foam mortars are given in Table 4. The spread values of test samples are approximately 145–150 mm, and the mini-slump test results are between 25 and 30 mm. The compressive strength tests were conducted on cube samples under uniaxial compressive stress as load control. Before the compressive strength tests, the ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) test, which is a non-destructive test method, was applied to the samples. Testing procedures for UPVs were performed in accordance with ASTM C 597 [41]. Afterwards, the foam mortars thinned by beating with a plastic hard mallet were examined by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) combined with Energy Dispersive X-Ray Analysis (EDX) for high-resolution imaging and elemental information. Determining tests of thermal performance of foam mortars were carried out according to EN ISO 8990 [42] and EN ISO 6946 [43]. The operating principle of the device used in the tests is the hot wire method, which complies with DIN 51046 [44] and EN 993-15 [45]. The solid surface probes of the ISOMET 2104 device measure the thermal conductivity (λ) at a sensitivity of 5% in the range of 0.04–0.06 W/mK and the volumetric specific heat (C) at a sensitivity of 15% in the range of 4 × 104–4 × 106 J/m3K, respectively. The measurements were made on five different points of the sample. During thermal performance tests, the ambient temperatures were in the range of 24.54–25.62 °C. It was studied on parameters such as thermal conductivity (λ), specific heat (cp), thermal diffusivity (α), and volumetric specific heat capacity (C) to determine the thermal properties of foam mortars. Brief descriptions and meanings of these parameters are as follows:

Table 3.

The nomenclature of the test series.

Table 4.

The component amounts of foam mortars for 1 m3 mixture.

- Density (ρ) is the amount of matter per unit volume of a material. It calculates as mass (m) divided by volume (V).

- The thermal conductivity coefficient (λ) is defined as watts (W) of the amount of energy passing through a unit area when the temperature difference between both surfaces of a material is 1 Kelvin (K),

- Specific heat (cp) is the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of a unit mass of a material by one degree.

- The thermal diffusivity coefficient (α) is defined as a velocity indicator of heat transferred from the hot side to the cold side for a material. It calculates thermal conductivity (λ) divided by volumetric specific heat capacity (C).

- The volumetric specific heat capacity (C) is defined as the multiplication of the specific heat capacity (cp) of the material by the density of the material (ρ).

According to these definitions [46], the lower λ value of a material, the less heat it conducts. In other words, it is a good insulator. Thermal diffusivity is a thermophysical property that describes the velocity at which heat is transferred through a material. The C and cp represent the specific heat of a material by volume and mass, respectively. They also provide information about the heat storage ability of the material.

3. Results and Discussions

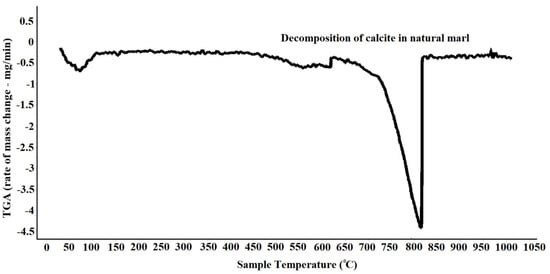

Calcined marl was used as a replacement material for the thermal and mechanical performance improvement of foamed mortars in the study. Natural marl could be expressed as a mudstone with varying proportions of silt and clays that is rich in calcium carbonate. When natural marl is calcined, it undergoes a chemical transformation. The calcination process increases the pozzolanic activity by driving off carbon dioxide and potentially altering the crystalline structure of the clay minerals. Figure 2 shows the thermal analysis of the natural marl in the present study. Figure 2 shows peaks at ~30 °C loss of adsorbed water, ~110 °C loss of crystallization water, and approximately in the range of 400–820 °C dehydroxylation of clay and decomposition of calcite. Decomposition of calcite is approximately in the range of 700–820 °C. According to the mineralogical investigations of the natural marl, the natural marl rock contains a large amount of montmorillonite along with other minerals. The mineral composition of the natural marl is presented in Table 5.

Figure 2.

Graph of TGA for natural marl.

Table 5.

Mineralogical analysis results of natural marl.

A pozzolan is a siliceous or siliceous-aluminous substance that has little to no binder value by itself. However, when it is finely ground, it will chemically react with calcium hydroxide at room temperature to create compounds with cementitious qualities [47]. For this reason, the marl used in the study was ground below the fineness of the PC used in the study. The pozzolanic activity of clays is also closely related to their having sufficient oxide concentrations. The oxide content acceptance criterion for a pozzolanic material is that the total percentage by mass of silica, alumina, and iron oxides must be above 70%. According to this, the chemical composition of natural marl contains 56.63% SiO2, 12.34% Al2O3, and 7.46% Fe2O3 (Table 1). The sum of these oxides is 76.43%. The calcined marl used in this study has sufficient oxide concentrations to fulfill the standard requirement of ASTM C 618-03 [48]. Additionally, the pozzolanic activity of a cementitious material could be defined with the strength activity index (SAI). So, the SAI of calcined marl was experimentally determined according to ASTM C618-22 [49]. If this index is determined to be 28 days, the strength is over a value of 75%. The examined pozzolanic material is named as having to enough activity. The SAI value of the sample produced by calcined marl is 78%. This value is compatible with the standard.

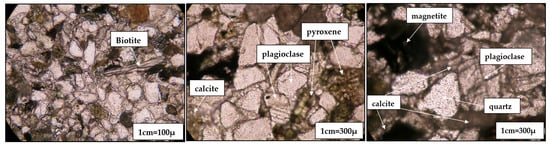

Moreover, to define the marl, mineralogical–petrographic analysis was carried out. The polarizing microscope images taken under a single light on thin sections obtained from rock samples belonging to the natural marl sample used in the study are presented in Figure 3. The images allow us to understand the mineral composition, petrographic information, and textural properties of the sample at the microscopic level. In the mineral composition of the sample, colorless, angular grains with distinct edges indicate quartz with a mosaic structure; one of the large grains in the center of the image exhibits very distinct cross-twinned lamellae. This twinning pattern is typical of the mineral plagioclase/feldspar. Also, calcites in the form of isotropic grains and a long leafy-striped biotite structure are in the middle right of the first image. The sample contains low-compacted, detrital minerals. It was deposited in a sedimentary environment and then underwent mild diagenesis. In the textural properties of the sample, the grains are distinct, and there is a clastic texture containing matrix or micritic carbonate filling between them. Clayey or carbonate matrix-supported structures among clasts are an indication of a low-energy environment during deposition. This indicates that the rock type of the examined sample is a mixture of clay+carbonate marl. Because marl is a carbonate rock with a clay matrix. The natural binder of the examined marl rock is calcite. The amount of calcite in natural marl rock is 17%. Table 5 shows other mineral distribution values in the rock. The matrix density of the sample is high. This situation could be interpreted as the rock having low porosity.

Figure 3.

Polarizing microscope views taken in single nicol on thin sections of natural marl rock.

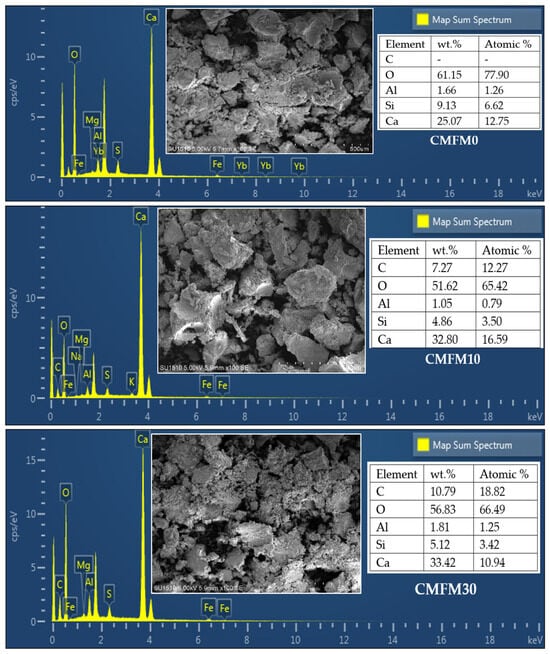

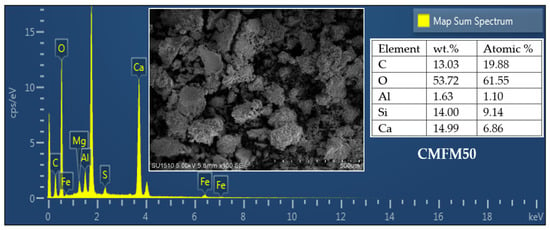

Afterwards, SEM-EDX analysis was performed on the samples. Some images and elemental information results obtained with SEM and EDX analysis performed on foam mortar samplings are shown in Figure 4. SEM photos shown in Figure 4 enable a more understandable examination of the foam mortar’s surface morphology and internal structure. The porous structure seen from photos of samples analyzed by SEM corresponds to the lightness of foam mortars. These surface morphologies of the foam mortar samples support our results regarding the thermal conductivity of this study. This is also an indication of the pore structure-thermal performance relationship. Moreover, these views are also an indicator of the accuracy of the methodology used in design energy saving foam mortar mixtures for building applications such as filling and insulation material. In addition, the thermal performance of foamed concrete depends on the pore size and pore structure of the cementitious matrices [38]. SEM analysis is also an appropriate method for the pore structure investigations of hardened foam mortars. So, according to SEM images of samples, the pore size and pore interconnectivity path of the CMFM0 (not contain calcined marl) sample were larger due to its higher fluidity. The increase in pore connection paths not only negatively affects the strength development of foam concrete but also makes the heat transfer path irregular in foam concrete [23]. However, as the replacement ratio of calcined marl increased, the pore interconnectivity paths, which are more clearly seen in the CMFM50 sample, became thinner, and the pore structure of the hardened samples improved. The SEM images support clear improvements in thermal performance of foam mortars.

Figure 4.

SEM images and EDX analysis results of foam mortar samplings.

To see the effect on the samples of the fineness difference between Portland cement and blended cement, a comparison was made between the foam concrete series produced with blended cements containing calcined marl ground below the cement fineness and the reference foam concrete series in terms of surface morphology. It was seen that the particle distribution was more uniform in the foam concrete series produced with blended cements containing calcined marl that has a higher Blaine fineness. Furthermore, as seen from elemental analysis results, increasing the amount of Ca element supports the strength results of the samples. Massive crystals of calcium hydroxide and small fibrous crystals of calcium silicate hydrate, hydration products, are seen from SEM images of CMFM10 and CMFM30. These explain increments in compressive strengths of foam mortars produced with calcined marl blended cement.

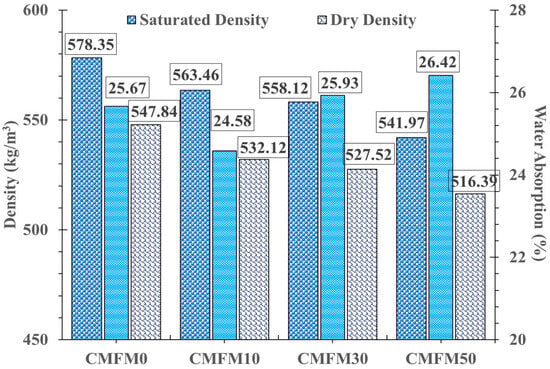

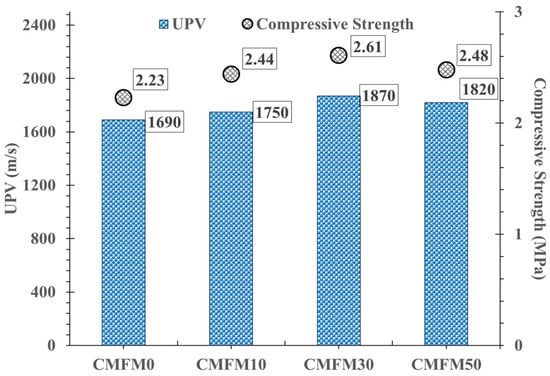

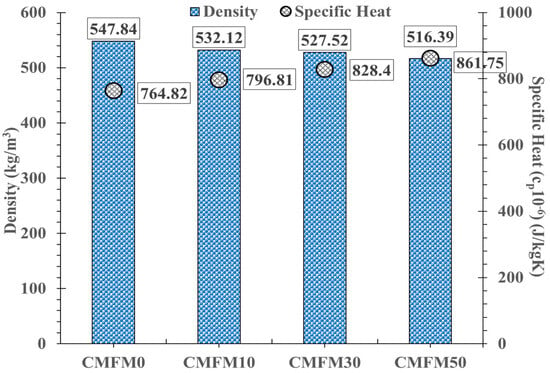

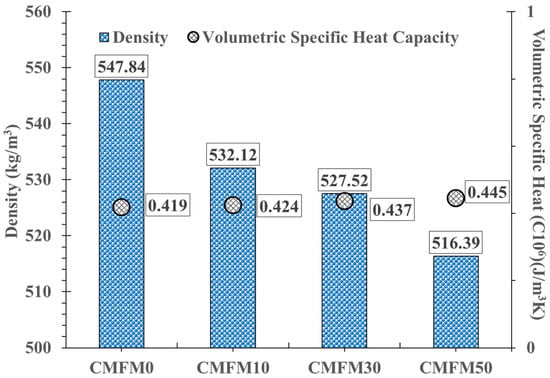

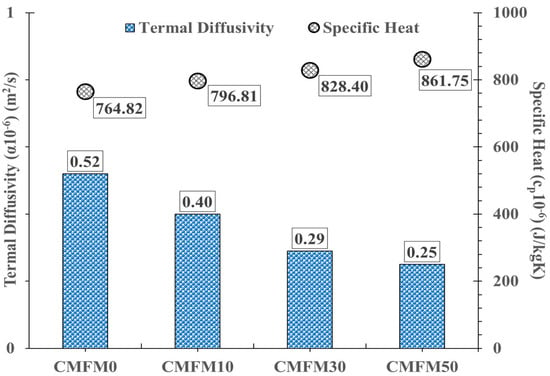

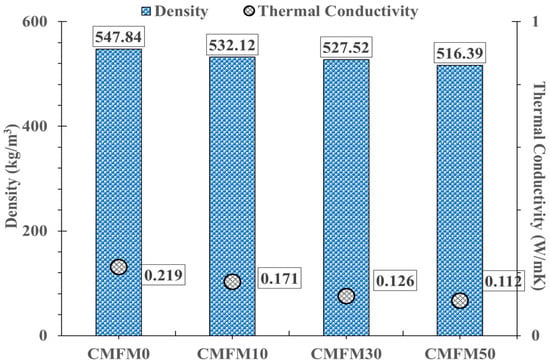

The saturated dry densities, water absorption, UPV, compressive strength, and thermal performance test results of elaborated foam mortar samples are comparatively given in Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Figure 5.

Saturated–dry density–water absorption relations.

Figure 6.

Strength–UPV relations.

Figure 7.

Specific heat–density relations.

Figure 8.

Volumetric specific heat capacity–density relations.

Figure 9.

Specific heat–thermal diffusivity relations.

Figure 10.

Thermal conductivity–density relations.

The densities for all foam mortar samples containing calcined marl decreased with the increase in calcined marl replacement ratios (Figure 5). This situation is a result of a decline in the density of the calcined marl [50,51]. The average percentages of water absorption of the series with calcined marl showed variation values according to the increasing presence of calcined marl. According to the water absorption test results, the reason why the water absorption values are slightly higher than the reference samples at 50% replacement ratio is the formation of a denser environment in the cement paste thanks to the calcined marl additive.

The compressive strengths of foam mortars increased up to a 30% replacement ratio (CMFM30) compared to the reference foam mortars (CMFM0) (Figure 6). The amount of increase is 17.04%. However, at a 50% replacement ratio, compressive strengths slightly decreased. The amount of decrease is 4.98%. Although this is decreasing, the strengths of the CMFM50 series are still better than those of the CMFM0 series, and the increases in compressive strengths are greater than the decreases. The minimum compressive strength in all test series of foam mortars is 2.48 MPa. Even this value conforms (>1.5 MPa) with TS EN 13655 [52]. This value is also 65.33% higher than the minimum requirement. It is thought that the improvement in the mechanical properties of foam mortars with calcined marl is related to the pozzolanic properties of calcined marl and the densified microstructure of cement paste due to calcined marl. The slight decrease in 28-day strength for samples at 50% replacement could be attributed to the decrease in the amount of binder. Additional binders formed at later ages in all of the test series with calcined marl, thanks to pozzolanic reactions, will contribute to the development of final strength. It is also known from the literature that, unlike materials with traditional Portland cement that reach their final strength at a very early age, materials with calcined marl reach their full strength within a few months. This difference can be explained by the slow hydration rate of the calcined marl and pozzolanic reactions during the dormancy period of several months. [53,54,55]. According to these explanations, considering that the only 28-day compressive strengths of the foam mortars produced in this study were studied, there is a strong expectation that the late-age strengths of foam mortars containing calcined marl will increase [22,30,32,34].

In another perspective, various studies in the literature emphasize that the SiO2 and Al2O3 content in the clayey materials used in the mixture has an important role in pozzolanic activity and hydration behavior [29]. Another study notes that the high SiO2 content enhances the formation of the CSH gel, improving the long-term strength of the product [56], and they emphasize that the optimum SiO2/Al2O3 ratio in clay content used in terms of reactivity and strength gain is between 2 and 4. Therefore, a suitable SiO2/Al2O3 ratio is quite important to optimize both mechanical properties and durability in cementitious applications. The SiO2/Al2O3 ratio of marl used in this study is 4.50 [30]. In another similar critical review study on cementitious materials, which included only calcined marl, a strong correlation was found between the change ratios (Al2O3+SiO2/MgO+CaO) of the oxides in the chemical content of calcined and the compressive strength. According to this, compressive strength values also increase as the Al2O3+SiO2 content increases [55]. Accordingly, the Al2O3+SiO2/MgO+CaO ratio of the natural marl in this study is 4.38. The natural marl composition used in this study has a fairly good proportional change to provide the desired compressive strength. This ratio supports the improvement in the compressive strength of the foam mortar samples produced in this study. Between the compressive strengths and UPV findings of foam mortars, similar trends were exhibited.

On the other hand, it is known from literature that calcined clays have high heat storage capacities [31]. The volumetric specific heat capacity of natural marl rock used in this study was determined as 1.83 × 106 J/m3K. The cp and C values of the CMFM50 series were 12.67% and 6.21% higher than those of the CMFMO series, respectively (Figure 7 and Figure 8). The increments in C and cp values with an increment in the calcined marl replacement ratio indicate improved heat storage ability of test samples in the dry state. Likewise, the decrease in the thermal diffusivity coefficient (α), which is another indicator of thermal performance, with the increase in the replacement ratio means that the heat energy is absorbed by the material, which is attributed to the improvement of the heat storage ability (Figure 9). The average thermal diffusivity coefficient of the series with calcine marl (CMFM50) were 51.92% lower than that of the series with PC (CMFM0). It is thought that marl particles are useful for the heat absorption ability of foam mortars. Thanks to these data, it could be interpreted that the use of calcined marl in foam mortar mixtures contributes to the improvement of heat energy storage ability in foam mortar.

A decline in the dry densities of foam mortars containing calcined marl blended cement, caused by the low density of calcined marl, resulted in similar trends in the thermal conductivity coefficients (λ) of those (Figure 10). The thermal conductivity coefficients of foam mortars containing calcined marl blended cement were between 0.112 and 0.171 W/mK. The main purpose of insulation materials is to reduce heat loss. This requires that their thermal conductivity be as low as possible. The average thermal conductivity coefficient of the series with calcine marl (CMFM50) were 48.86% lower than that of the series with PC (CMFM0). This situation could be expressed as the improvement of the thermal insulation abilities, such as the heat storage abilities of foam mortars produced with calcined marl blended cement. Moreover, these thermal improvements of foam mortars occurred without compromising their strength values.

4. Conclusions

The conclusions of this study on the improvement of thermal performance of foam mortar with calcined marl blended cement are below:

The compressive strengths of foam mortars containing calcined marl blended cement compared to those of reference foam mortars showed an improvement of up to 30% replacement ratios. The average thermal conductivity coefficient of the series with calcine marl (CMFM50) were 48.86% lower than that of the series with PC (CMFM0). This situation is interpreted as the improvement of the thermal insulation abilities of foam mortars produced with calcined marl blended cement. The cp and C heat storage values (of CMFM50 series were 12.67% and 6.21% higher than those of CMFMO series, respectively. The average thermal diffusivity coefficient of the series with calcine marl (CMFM50) was 51.92% lower than that of the series with PC (CMFM0). Accordingly, the heat storage abilities of foam mortars containing calcined marl blended cement were improved with an increase in the calcined marl replacement ratio.

Due to the use of calcined marl blended cement in the study, we present a novel foam concrete design with ecological, economical, and lower energy consumption, and it also improved the thermal performances of foam mortars in terms of heat storage and insulation without compromising sufficient strength. The results are promising in terms of improving the thermal performance of foamed concrete.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The author confirms that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the laboratories of Dicle University and Altaş Ready-Mixed Concrete Company.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| EDX | Energy Dispersive X-Ray |

| UPV | Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric Analysis |

| CSH | Calcium-Silicate-Hydrate |

| PC | Portland Cement |

| CMFM | Calcined Marl Foam Mortar |

| SAI | Strength Activity Index |

| TS | Turkish Standards |

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials |

| DIN | Deutsches Institut für Normung |

References

- IEA. Energy Efficiency 2024; IEA: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-efficiency-2024 (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2024; IEA: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2024 (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. The State of Energy Innovation; IEA: Paris, France, 2025; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/the-state-of-energy-innovation (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- UNEP. United Nations Environment Programme, 2020 Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction: Towards a Zero-Emission, Efficient and Resilient Buildings and Construction Sector; Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://globalabc.org/resources/publications/2020-global-status-report-buildings-and-construction (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Onyelowe, K.C.; Ebid, A.M.; Vinueza, D.F.F.; Brito, N.A.E.; Velasco, N.; Buñay, J.; Muhodir, S.H.; Imran, H.; Hanandeh, S. Estimating the compressive strength of lightweight foamed concrete using different machine learning-based symbolic regression techniques. Front. Built Environ. 2024, 10, 1446597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhu, Z.; Shi, L.; Kang, X.; Wan, Y.; Huo, W.; Yang, L. Compressive strength and sensitivity analysis of fly ash composite foam concrete: Efficient machine learning approach. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2024, 192, 103634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohtadi, A.; Ghomeishi, M.; Dehghanbanadaki, A. Towards Sustainable Construction: Evaluating Thermal Conductivity in Advanced Foam Concrete Mixtures. Buildings 2024, 14, 3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.H.; Xie, Y.L.; Chen, Y. Innovative Multi-Functional Foamed Concrete Made from Rice Husk Ash: Thermal Insulation and Electromagnetic Wave Absorption. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 16112–16128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Wang, H.; Qin, L.; Sun, H.; Zhao, Y.; Kelehan, C. Experimental and numerical study on seismic performance of prefabricated new fly ash foam concrete structure. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2024, 178, 108462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Garrecht, H. Effects of Mixing Techniques and Material Compositions on the Compressive Strength and Thermal Conductivity of Ultra-Lightweight Foam Concrete. Materials 2024, 17, 2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintsaev, M.; Murtazaev, S.A.; Salamanova, M.; Bataev, D.; Saidumov, M.; Murtazaev, I.; Fediuk, R. Structural Formation of Alkali-Activated Materials Based on Thermally Treated Marl and Na2SiO3. Materials 2022, 15, 6576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.; Yu, J.; Lin, J.; Chen, Z.; Li, J. Experimental Investigations of Prefabricated Lightweight Self-Insulating Foamed Mortar Wall Panels. Structures 2024, 61, 106001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellatief, M.; Ahmed, Y.M.; Taman, M.; Elfadaly, E.; Tang, Y.; Abadel, A.A. Physico-Mechanical, Thermal Insulation Properties, and Microstructure of Geopolymer Foam Mortar Containing Sawdust Ash and Egg Shell. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 90, 109374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyatham, B.; Lakshmayya, M.T.S.; Chaitanya, D. Review on Performance and Sustainability of Foam Mortar. Mater. Today Proc. 2023; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.M.; Tayeh, B.A.; Majeed, S.S.; Aisheh, Y.I.A.; Salih, M.N.A. Ultra-Light Foamed Mortar Mechanical Properties and Thermal Insulation Perspective: A Comprehensive Review. J. CO2 Util. 2024, 83, 102827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhao, X.; Wang, X.; Song, T.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H. Elevated temperature properties of foam concrete: Experimental study, numerical simulation, and theoretical analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellatief, M.; Elrahman, M.A.; Alanazi, H.; Abadel, A.A.; Tahwia, A. A state-of-the-art review on geopolymer foam concrete with solid waste materials: Components, characteristics, and microstructure. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2023, 8, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, W.; Meng, T.; Zhao, X.; Pang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Liu, D.; Wang, R.; Yang, V.; et al. Lightweight, thermally insulating, fire-proof graphite-cellulose foam. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2204219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergan, P.G.; Greiner, C.J. A new type of large scale thermal energy storage. Energy Procedia 2014, 58, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Amin, M.; Ahmed, B.; Khan, K.; Arifeen, S.; Althoey, F. Foam mortar for lightweight construction applications: A comprehensive review of the research development and material characteristics. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2024, 63, 20240022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compaore, A.; Toure, J.-Y.N.K.; Klenam, D.E.P.; Merenga, A.S.; Asumadu, T.K.; Obayemi, J.D.; Rahbar, N.; Migwi, C.; Soboyejo, W.O. Foam concrete with mineral additives: From microstructure to mechanical/physical properties, workability and durability. Open Ceram. 2025, 23, 100812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, X.; Yalçınkaya, Ç.; Çopuroğlu, O.; Liu, Y. Evaluation of thermal insulation capacity and mechanical performance of a novel low-carbon thermal insulating foam mortar. Energy Build. 2024, 323, 114744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Sun, C.; Cheng, S.; Yang, C. Carbon sequestration and mechanical properties of foam concrete based on red mud pre-carbonation and CO2 foam bubbles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 426, 135961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ta, X.; Wan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, S.; Zhou, J. Effect of carbonation and foam content on CO2 foamed concrete behavior. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 23, 6014–6022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwarampudi, M.; Venkateshwari, B. Performance of light weight mortar with different aggregates—A comprehensive review. Discov. Civ. Eng. 2024, 1, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanim, A.A.J.; Amin, M.; Zeyad, A.M.; Tayeh, B.A.; Agwa, I.S.; Elsakhawy, Y. Effect of polypropylene and glass fiber on properties of lightweight concrete exposed to high temperature. Adv. Concr. Constr. 2023, 15, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Su, R.K.L. A Review on Durability of Foam Concrete. Buildings 2023, 13, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgün, Y. Alternatif puzolan kalsine marn içeren sürdürülebilir katkılı çimentolar. Dicle Üniv. Mühendis. Fak. Mühendis. Derg. 2019, 10, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgün, Y. Thermal performance of mortars/concretes containing calcined marl as alternative pozzolan. Emerg. Mater. Res. 2021, 10, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahhou, A.; Taha, Y.; Khessaimi, Y.E.; Hakkou, R.; Tagnit-Hamou, A.; Benzaazoua, M. Using calcined marls as non-common supplementary cementitious materials—A critical review. Minerals 2021, 11, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgün, Y. Behavior of concrete containing alternative pozzolan calcined marl blended cement. Period. Polytech. Civ. Eng. 2020, 64, 1087–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safhi, A.M.; Khesssaimi, Y.; Taha, Y.; Hakkou, R.; Benzaazoua, M. Calcined marls as compound of binary binder system: Preliminary study. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 58, 1049–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahhou, A.; Taha, Y.; Hakkou, R.; Benzaazoua, M.; Tagnit-Hamou, A. Assessment of hydration, strength, and microstructure of three different grades of calcined marls derived from phosphate by-products. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 84, 108640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, N.; Ozgünler, S.A.; Ozdamar, S. Investigation of production possibilities of natural hydraulic binders from marls. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 470, 140675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Qi, X.; Guo, S.; Zhang, L.; Ren, J. A systematic research on foamed concrete: The effects of foam content, fly ash, slag, silica fume and water-to-binder ratio. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 339, 127683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Ge, Z.; Sun, R.; Xu, X.; Lu, Y.; Ling, Y.; Zhang, H. Drying shrinkage, durability and microstructure of foamed concrete containing high volume lime mud-fly ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 327, 126990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishavkarma, A.; Venkatanarayanan, H.K. Assessment of pore structure of foam concrete containing slag for improved durability performance in reinforced concrete applications. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86, 108939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEN EN 197-1; Cement Part 1: Composition, Specification and Conformity Criteria for Common Cements. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2012.

- CEN EN 196-1; Methods of Testing Cement—Part 1: Determination of Strength. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- ASTM C 597; Standard Test Method for Pulse Velocity Through Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2009.

- CEN EN ISO 8990; Thermal Insulation—Determination of Steady-State Thermal Transmission Properties-Calibrated and Guarded Hot Box. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 1989.

- CEN EN ISO 6946; Building Components and Building Elements—Thermal Resistance and Thermal Transmittance—Calculation Methods. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- DIN 51046; Testing of Ceramic Materials; Determination of Thermal Conductivity up to 1600 °C According to the Hot Wire Method, Thermal Conductivity up to 2 WK−1m−1. The German Institute for Standardization: Berlin, Germany, 1976.

- CEN EN 993-15; Methods of Test for Dense Shaped Refractory Products—Determination of Thermal Conductivity by the Hot-Wire (Parallel) Method. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2006.

- Incropera, F.P.; De Witt, D.P.; Bergman, T.L.; Lavine, A.S. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer, 6th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Drissi, M.; Horma, O.; Mezrhab, A.; Karkri, M. Exploring Raw Red Clay as a Supplementary Cementitious Material: Composition, Thermo-Mechanical Performance, Cost, and Environmental Impact. Buildings 2024, 14, 3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C618-03; Standard Specification for Coal Fly Ash and Raw or Calcined Natural Pozzolan for Use in Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2003. [CrossRef]

- ASTM C618-22; Standard Specification for Coal Fly Ash and Raw or Calcined Natural Pozzolan for Use in Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.V.; Arunkumar, C.; Senthil, S.S. Experimental Study on Mechanical and Thermal Behavior of Foamed Concrete. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 8753–8760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambiar, E.K.K.; Ramamurthy, K. Influence of filler type on the properties of foam concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2006, 28, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TS EN 13655; Specification for Masonry Units—Foam Concrete Masonry Units. Turkish Standard Institue: Ankara, Türkiye, 2015.

- Badaoui, M.; Hebbache, K.; Douadi, A. Utilization of Algerian calcined clay in sustainable mortars considering thermal treatment and granulometry effects on mechanical properties. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliki, S.; Bayoussef, A.; Hakkou, R.; Hamidi, M.; Mansori, M.; Oussaid, A.; Loutou, M. Phosphate mine by-products as new cementitious binders for eco-mortars production: Experiments and machine learning approach. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 92, 109767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varas, M.J.; De Buergo, M.A.; Fort, R. Natural cement as the precursor of Portland cement: Methodology for its identification. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 2055–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yuan, Q.; Deng, D.; Peng, J.; Huang, Y. Effects of chemical and mineral admixtures on the foam indexes of cement-based materials. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2019, 11, e00232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).