Abstract

Access to nature is fundamental to human health and wellbeing, yet opportunities for direct and frequent engagement with natural environments are often restricted for individuals in the 80+ age category, particularly those in care settings or living in remote locations. There is therefore an urgent need to enhance nature connections in care settings and provide personalised, restorative experiences that reflect individuals preferred natural features. This prefeasibility pilot study developed a framework to inform the design of therapeutic care settings, grounded in the principles of biophilic neuroarchitecture and designed to support ageing well. Conducted over six months in two care environments, the study applied the biophilic pattern of Complexity and Order to simulate Natural Analogues within immersive virtual settings. Mixed methods combining wearable sensor data and self-reported wellbeing measures were used to assess psychophysiological, emotional, and cognitive responses among participants aged 80 and above. Findings revealed that VR content aligned with individual nature preferences elicited higher levels of engagement, relaxation, and positive affect. This study demonstrates the potential for implementing biophilic design applications to develop therapeutic care settings which promote wellbeing and healthy ageing, particularly where access to real nature is infrequent or limited.

1. Introduction

There is a mismatch between human physiology and the environments individuals reside and work in; humans have evolved to adapt to external stimuli. Individuals spend much of their time inside buildings; connections to nature should be encouraged to maximise health and wellbeing outcomes. Inside buildings, everything is static and homogenous, and variations do not exist. Nature provides multisensory and dynamic instances, which are complex, ordered, and often predictable (i.e., seasons, sunsets and sunrises, tides, patterns). Biophilic design improves the health and wellbeing of patients when applied in healthcare facilities (i.e., improved recovery rates, less pain relief administration) [1] along with inspiration [2,3,4].

Disconnection from nature has a negative impact on individuals; access to nature is compromised when people are at their most vulnerable (hospitals, care facilities). Biophilic design applications can provide indirect contact with nature through Natural Analogues (images, artworks, materials). Biophilic neuroarchitecture focuses on the human experience by creating spaces to maximise health and wellbeing, with an emphasis on multisensory elements [5]. Connections to nature through dynamic and complex elements should be integrated to provide sensory-rich experiences, for example by replicating the patterns, forms, movements and sensory qualities of nature. Individuals in care settings need to thrive and live in a space and environment suited to their physiological and psychological requirements. However, the NHS Framework for Enhanced Health in Care Homes [6] states that 40% of residents suffer from psychological conditions, with depression being the most widespread. Additionally, individuals in the 80+ age category experience sensory decline and mobility impairments, which have also been associated with depression [7]. Furthermore, access to outdoor spaces and activities are dependent on staff availability and safety [8]. Consequently, under-stimulating care facilities have been linked to isolation and anxiety [9]. Current research is lacking on the topic of biophilic care settings, so this requires further exploration [10]. Biophilic applications are not included in mainstream care settings; subsequently, design guidelines are required to implement nature’s dynamic qualities to create therapeutic care settings.

According to the biophilic framework by Terrapin Bright Green (14 Patterns of Biophilic Design) [11], Nature in the Space has been successfully researched and measured against psychophysiological measurements; however, considerable gaps remain for Natural Analogues (e.g., patterns and biomorphic forms, material, Complexity and Order) [11]. Complexity and Order are defined as sensory-rich information which mimics nature’s order [11]. Elements include the patterns and forms found in nature [12]. Current research indicates individuals prefer aesthetics which embed Complexity and Order [12,13,14]. Complexity and Order in nature are assessed through fractal dimension. Many patterns in nature are fractals (i.e., clouds, tree branching and water patterns). Fractals in nature have influenced architecture and art to provide harmony and often appear on historic buildings from various traditions and on modern facades (i.e., tree branching, patterns repeated at different scales). Fractal perception studies have demonstrated that humans prefer fractals over non-fractal images as the former are visually easily processed [15]. Neurophysiological outcomes from fractals have been studied [13,14,15]. Mid D fractals (between 1.3 and 1.5) are proven to decrease stress and are more appealing [15]. Gaps in fractal dimensions remain and could potentially be assessed in VR [16]. In healthcare, facilities (i.e., paintings, photos) and technologies (i.e., TV, VR) could be employed for residents to experience simulated nature [1]. Fabrics and furnishings could reflect the rich dynamic qualities of nature fractals. Currently, there is insufficient research on VR for individuals in care facilities [17,18] and a lack of longitudinal studies in clinical settings [19]. Lastly, VR interventions should be elaborated upon preferences and include personalised content to maximise effectiveness [20].

Biophilic design applications are assessed against three health and wellbeing outcomes: emotion mood and preferences, stress reduction and cognitive performance. For stress reduction, skin conductance, heart rate, and blood pressure are commonly assessed through wearable biomonitoring sensors [21,22,23]. To assess emotion, mood and preferences, self-reported questionnaires such as PANAS and QOL [9,17,21] have been utilised for subjective health and wellbeing to identify beneficial outcomes. For cognitive performance, Stroop and memory tests have been employed along with functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS). fNIRS can study brain function by examining prefrontal cortex activation (blood flow) and has been applied in clinical trials, hypothesis and theory [24] whilst having the advantage of being portable, cost effective, and non-invasive [24,25], being suitable for people in the 65+ age category, as well as various patients [26].

The aim of this study was to develop a therapeutic design framework for care settings founded on the concept of Complexity and Order in biophilic design. The main objective was to assess virtual environments that simulate natural forms and patterns at different scales of fractal complexity and assess the health and wellbeing outcomes through a prefeasibility study in care settings. VR biophilic interventions were assessed against psychophysiological measurements (emotion, mood and preferences, stress reduction, and cognitive performance). An initial meeting at the facilities provided insights into key concepts to include in the study; a scoping review on biophilic existential therapy was developed to identify important concepts to include in the prefeasibility study. The ROSES protocol was employed (Reporting Standards for Systematic Evidence Synthesis) to maintain transparency and reproducibility [27]. Database searches carried out in November 2023 included the Web of Science and Scopus; search terms were broken down into “Existential Therapy” or “Humanistic Therapy”, or “Biophilic Care Homes” and “Biophilic Care.” A total of 99 articles were identified and 29 were retained. Progressive steps were implemented to select the most suitable studies for the scoping review: exclusion criteria included studies from 2005 onwards only, focused on both men and women and the above 65+ age group or at the EOL. In total, 29 articles were analysed and categorised (Appendix A). A deductive approach was employed for thematic analysis in NVIVO using established frameworks to provide a comprehensive understanding of biophilic existential therapy: identifying gaps. A codebook (key themes and sub themes) was added in NVIVO. Themes included biophilic health and wellbeing outcomes, dynamic design applications and existential aspects.

2. Materials and Methods

A pre-feasibility pilot study was conducted over a six-month period across two care facilities (a hospice and a care home). Mixed research methods were employed: a scoping review of observations (verbal and non-verbal, collected throughout the pilot study), a nature preference questionnaire to identify preferences and inform the VR content creation, and, finally, a protocol to assess the health and wellbeing outcomes from the interventions. Consent forms and participant information sheets were provided at each stage of the project and for each intervention. Assistance (reading, signing) was provided to participants with impairments. A 6-digit unique identifier was created for each participant (pseudonymisation). Participants were reminded at each stage of the project that they could withdraw at any point during the study.

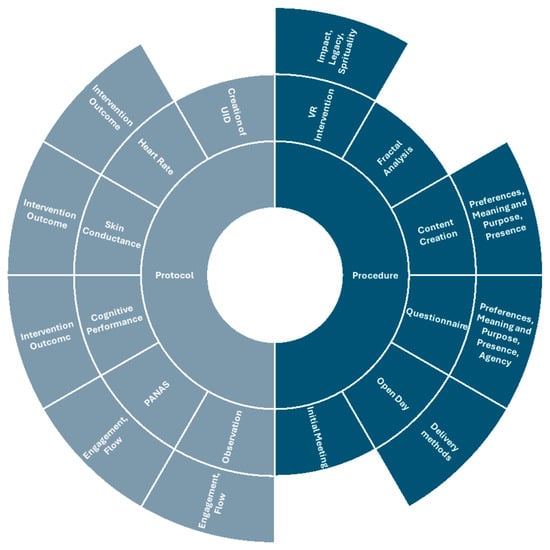

Pre-Feasibility Study Procedure

A procedure (Figure 1) was developed to guide the pre-feasibility study. Firstly, an inception meeting was held with the managerial team to inform the study, and an open day took place for the patients and residents to familiarise themselves with the project before taking part. Secondly, participants completed a nature preference questionnaire to identify individual preferences for us to reflect this in the VR content. The questionnaire in Qualtrics included the following:

- Demographic questions: Age, gender, and previous profession.

- The six-item Nature Relatedness Scale (NR-6) to assess connections and behaviours towards nature [28].

- The PELI questionnaire to identify preferences related to outdoor activities, weather, temperature, and frequency [29].

- Three open questions on sensory, mobility impairments and technological use, and favourite places in nature.

Figure 1.

Methodology framework and procedure.

Following this, scenes were created with the Insta360 camera (3 min); screenshots were assessed for fractal dimension (D value) in the FracLAC version 2.0 software plugin for Image J. Images were set to greyscale in Image J and analysed (scanned) using the box counting method. Participants viewed 2 environments in VR which represented statistical fractals in nature, comparing fractal dimensions of 1.5 (medium) and 1.7 (high). VR nature scenes were created locally and delivered to participants within two weeks.

- Level 1—a fractal dimension value around 1.5 (no visible dynamic and sensory qualities): a still landscape scene.

- Level 2—a fractal dimension value above 1.7 (dynamic and sensory qualities): a highly immersive scene.

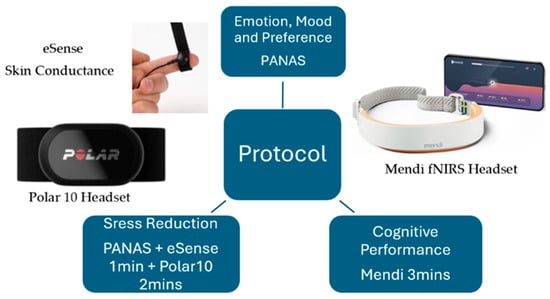

Finally, a protocol was developed to assess objective and subjective health and wellbeing outcomes from the fractal scenes viewed in VR. The Biophilic Therapy Monitoring Platform (BTMP, Figure 2) guided the VR intervention and aimed to determine whether Complexity and Order had merit for further exploration. Emotion, mood, preference and stress reduction were assessed through wearable sensors and the PANAS questionnaire (Qualtrics: interested, relaxed, happy, excited, dissatisfied, and surprised) [30]. Cognitive performance was measured with the Mendi Headset (fNIRS: 3 min). For stress reduction, a heart rate chest band (Polar 10) and eSense skin conductance sensors were employed. Sensors were worn during the entire intervention; the researcher reset the sensors for each level observed. Participants completed a short Qualtrics questionnaire (PANAS) for each level; the total intervention duration was 30 to 40 min, including setting up the instruments, and 2 min was the duration in each VR nature environment. Participants remained seated to limit cybersickness. Verbal and non-verbal observations were recorded throughout the VR intervention to assess behavioural differences between fractal levels. Data from the wearable sensors were extracted from their corresponding apps and included in the intervention record sheet along with feedback from participants. The raw data from the consumer-grade wearable sensors were processed locally and only reflect the processed data. We summarised the data, making them easier to manage. The duration of each wearable sensor (Figure 2) and the healthy ranges were defined within the app’s instructions and have been included within the outcomes table. For accuracy, the activity co-ordinator checked the outputs from the wearable sensors. Finally, a personal profile was developed for each participant to include all observations through each step of the procedure. Qualitative and quantitative data were analysed separately, looking for patterns in the data and identifying themes in the qualitative findings. Following this, data triangulation between psychophysiological responses (wearable sensors, verbal and non-verbal observations, PANAS questionnaire) was employed to compare individual and group subjective and objective findings.

- Wearable sensors (BTMP protocol).

Figure 2.

Biophilic Therapy Monitoring Platform (BTMP). eSense Skin Conductance [31], Polar 10 Headset [32], Mendi fNIRS Headset [33].

3. Results and Discussion

All participants agreed to have their data collected; seven completed the nature preference profile questionnaire, and four continued to the VR intervention stage. Participants were all in the 80+ age category, the median being 91 years old (mean: 91.5) with 6/8 female participants and 2/8 being male, all from a range of working backgrounds. All participants had either a mobility or a sensory impairment; 4/7 participants had both. In line with the literature, mild sensory and moderate mobility impairments did not impact the interventions as VR settings can be adjusted for hearing and vision impairments. VR interventions for individuals in the 80+ age category should include a pre-assessment of impairments to adjust and improve the VR experiences. Furthermore, no cases of cybersickness were reported during both the procedure and the protocol. From the observations, participants enjoyed interacting with the instruments and the technologies throughout the project; sensors provided instant feedback on aspects of their health and wellbeing. Although not all participants employed all the sensors (some health conditions may restrict the use of wearable technologies), wearable sensors are valuable in care facilities for both the patient and the care team as they can provide instant and visual reassurance when feedback and instructions for each sensor is provided. Two participants employed the Mendi fNIRS headset (due to Mendi not working during an intervention day). Two of the four participants employed Polar 10. According to the observations, physical impairments may restrict the use of the chest band. Three of the four participants trialled the eSense skin conductance sensor.

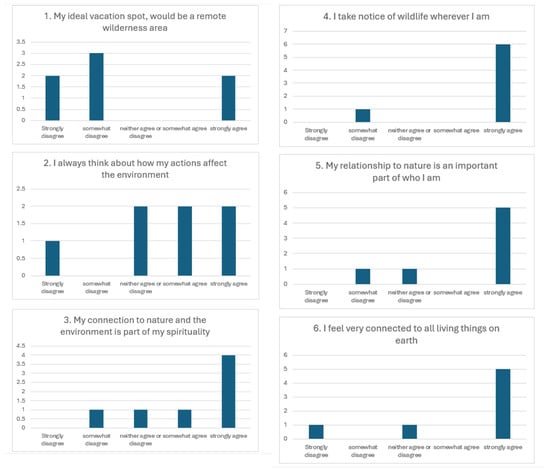

- Nature Preference Questionnaire

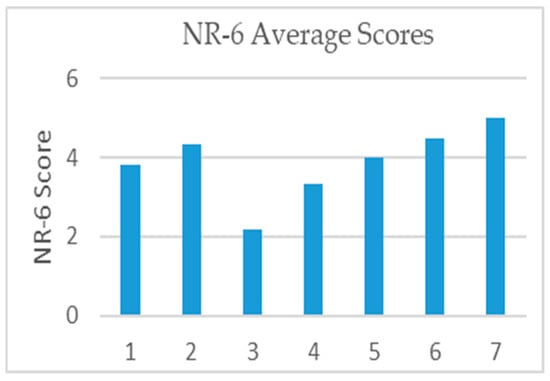

From the nature preference questionnaire, open questions on technological use showed that all participants employed a range of technologies: mobile phones, tablets, and laptops. From the pilot study procedure, it was observed that some participants were familiar with virtual reality (previous VR interventions had been offered at the facilities or through relatives), whilst others had never seen or used VR. Individuals in the 80+ age group have a strong connection to nature, reflecting the importance of being in and around nature in everyday life. The NR-6 scores showed that 6/7 participants had an above-average score of 3 (Figure 3). Observations of nature and wildlife, nature and spirituality, along with a sense of connection and nurture towards nature, were the most important aspects identified (further score details are in Appendix B). Furthermore, findings from the PELI questionnaire highlight the importance of access to nature for relaxation, fresh air, socialising, and taking part in activities. Frequent access to nature is a necessity but not always possible due to physical impairments. During the study, it was observed that nature was employed as a self-care tool; spirituality in nature, being available to observe nature (stand and stare), and seating preferences based on outside views of vegetation were identified as elements of this. Based on the responses to the open questions, participants preferred woodland and countryside scenes. Out of the seven participants who completed the nature preference profile questionnaire, four proceeded to the VR Intervention and four VR environments were created: two medium (Level 1)- and two high-fractal (Level 2) scenes (see Table 1 below). As the scenes were developed, the high-fractal scenes provided dynamic, multisensory and information-rich instances compared to the medium-fractal scenes, where sounds and movements in nature were less noticeable.

Figure 3.

NR-6 scores by participants.

Table 1.

Level 1 (L1) and Level 2 (L2).

- Psychophysiological outcomes

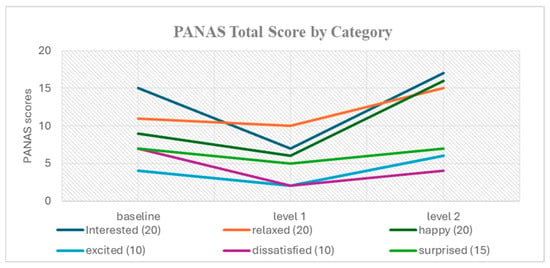

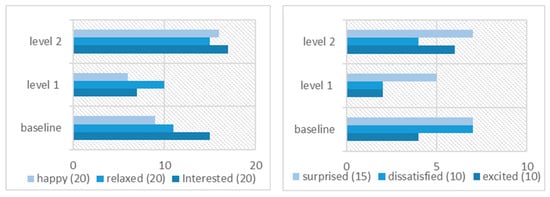

The graph below (Figure 4) represents the total score for all the PANAS responses, according to the Baseline, Level 1 and Level 2, in brackets against maximum response scores for each category. Not all participants responded to the same questions, and they were permitted to choose which to ignore. From the observations, 3/7 participants mentioned a lack of excitement and pride; this was also reflected in the PANAS questionnaire (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Subjective health and wellbeing outcomes from PANAS questionnaire (Baseline, L1, L2).

The bottom of Figure 5, to the left, shows the differences between levels, according to the highest responses and scores from the PANAS questionnaire. To the right represents the lowest scores and lowest responses. Level 1 achieved an inferior score compared to the Baseline.

Figure 5.

Subjective health and wellbeing outcomes from PANAS categories. (Baseline, L1, L2).

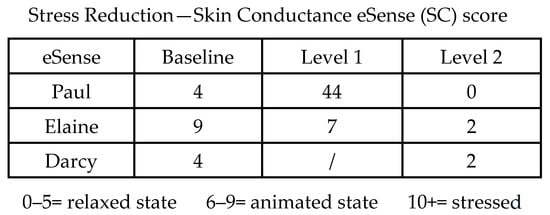

For skin conductance, the SC score decreased to a range of 0-2 for all three participants when comparing Level 2 to the Baseline (Figure 6). This is also in line with other studies [21].

Figure 6.

eSense scores for Baseline, L1 and L2.

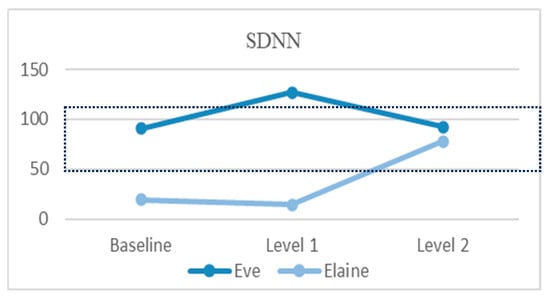

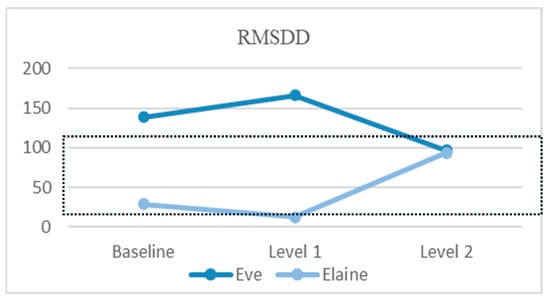

Measurements for heart rate from Polar 10 showed that both HRV and HR are inconclusive. However, SDNN and RMSDD are in the healthy range in Level 2 compared to Level 1 (Figure 7 and Figure 8). For SDNN, a higher score shows better coping with stress: with scores +100 being good and those of 50 or below being outside the healthy range. For RMSDD, the healthy reference ranges from 20 to 89 ms, while values below 19 ms and 107+ are outside of the healthy zone. Both ranges are highlighted by the dotted line. Both participants were outside the healthy zone before taking part in the intervention (Baseline SDNN for Elaine and RMSDD for Evelyn). This is also in line with the results of another study [22].

Figure 7.

SDNN scores: Baseline, L1 and L2.

Figure 8.

RMSDD scores: Baseline, L1 and L2.

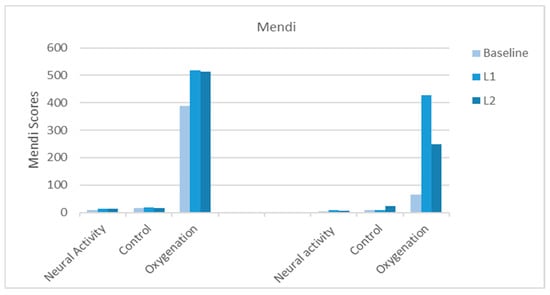

For cognitive performance (Figure 9), scores showed potential improvements for three categories when compared to the baseline. This is also in line with the results of other studies, in which cognitive performance tests showed an improvement after viewing a biophilic space. Memory improved by 14% based on the visual reaction time test and Stroop test [21]. However, during the interventions, participants were able to view the Mendi app game, and with further practice, this may have improved their scores. Mendi should be used without participants viewing the game to improve the reliability of the outputs.

Figure 9.

Mendi scores for Baseline, L1 and L2 (Paul (left) and Evelyn).

Both objective and subjective measures for stress reduction (PANAS responses; skin conductance and heart rate measurements) demonstrated the potential for improvements when comparing Level 1 to Level 2. Level 1 did not reach the participants’ expectations whereas Level 2 did. The self-reported questionnaire responses match the findings from other studies: biophilic interventions can decrease stress, and improve emotion [21] and mood [17]. All participants preferred Level 2, scenes with a fractal D value above 1.7. Level 1 (as shown in Figure 4) shows a dip in PANAS scores for medium-fractal scenes, with an increase from L1 to L2, and scores exceeding the Baseline score for happy, relaxed, interested, and excited. Dissatisfaction decreased slightly for both L1 and L2 compared to the Baseline; surprise remained the same for the Baseline and Level 2; however, it achieved a lower score for L1. From the observations, contentment, which reflected participants’ preferences (L2—high-fractal dimension: 1.7), had the greatest impact on health and wellbeing outcomes. Multiple verbal and non-verbal observations for Level 2 included awe, counting trees, gestures mimicking the scenes, and higher absorption. Multisensory-rich nature scenes which depict nature’s dynamic qualities through fractals are essential. Complexity and Order through patterns and forms can effortlessly be integrated to create therapeutic care settings. Previous studies have shown that physiological and cognitive responses are consistent between VR environments and physical exposure to nature [21,34,35]. However, the findings from the quantitative outcomes are not generalisable, so further studies are required to assess the impact of Complexity and Order through fractals in VR. A larger sample size is required to generalise these findings.

- Existential and spiritual aspects

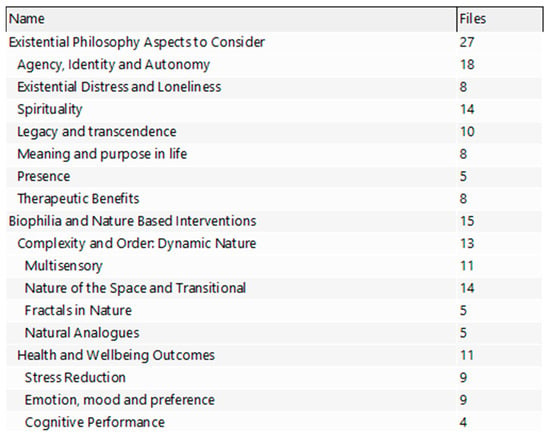

During the initial stages, existential concepts emerged from meetings with the managerial team and discussions with the participants. Existential and spiritual distress were recognised as a major concern for individuals in care settings [36,37]. Furthermore, existential comments were observed throughout the pilot study procedure; 3/7 participants mentioned a lack of excitement and pride, and this was also reflected in the PANAS questionnaire (Figure 6). Observations throughout the pilot study were added to NVIVO. An inductive approach was employed to identify participants’ experiences. Emerging themes included lack of excitement in life, spirituality in nature, impact, the importance of presence (being in the now) and presence through meaningful interactions (i.e., active listening and exchanging ideas). From the scoping review, predefined themes for the codebook included biophilic health and wellbeing outcomes, dynamic design applications, and existential aspects. The themes were assessed for frequency for all 29 papers (see Figure 10 for themes associated with frequency). Existential and philosophical aspects to consider within care settings included agency, identity and autonomy (18), along with legacy and transcendence (10), and spirituality (14). For biophilia and nature-based interventions multisensory nature (11) and Nature of the Space/transitional spaces (14) were the most common reoccurring themes.

Figure 10.

NVIVO-predefined codes and frequency.

Presence, i.e., being in the now, is challenging for participants in the 80+ age category, which was identified in the scoping review and observations. As VR is highly immersive, the sense of presence in nature is heightened; participants also noticed the content was taken recently and locally. According to responses to the nature questionnaire, nature provides spirituality and meaning. Finally, to comprehensively assess health and wellbeing outcomes for interventions in the 80+ age category, existential aspects must be integrated and evaluated through engagement or absorption (flow questionnaire). Future research should focus on micro-flow activities in care facilities [38]. Finally, design applications in cares settings should focus on nature’s multisensory aspects, and Complexity and Order, through fractal patterns, to provide information-rich and therapeutic spaces. Observations and outputs from NVIVO were included in a framework (Figure 11) which combines biophilic and existential aspects for consideration in therapeutic care settings.

Figure 11.

Framework for biophilic VR interventions in care settings.

4. Conclusions and Future Research

Biophilic neuroarchitecture informs the design of therapeutic care settings by supporting indirect contact with nature and improving health and wellbeing. This paper is focused on the biophilic application of Complexity and Order through Natural Analogues to inform the design of therapeutic care settings. Scenes in VR with medium- and high-fractal dimensions were evaluated against health and wellbeing outcomes. Subjective and objective health and wellbeing outcomes showed potential improvements when comparing the Baseline to Level 2. Scenes in L2 had a fractal dimension of 1.7 and included rich multisensory and dynamic elements, as well as a highly immersive VR environment when compared to Level 1, with a fractal dimension of 1.5. All four participants preferred fractal scenes in VR with a fractal dimension of 1.7. Emotion, mood, preferences and stress reduction improved in L2 compared to L1. Potential stress reductions were observed for both eSense and Polar 10 (RMSDD and SDNN) when comparing the Baseline to level 2. Medium-fractal scenes with a dimension of 1.5 scored lower than the Baseline. Fractals above 1.7 in VR provided a highly immersive space where the sense of presence was intensified. Mendi improved in all three outcomes (neural activity, control, and oxygenation) when comparing the Baseline to L1 and L2. Partial data from the interventions, however, suggest merit for further investigation. In line with the literature, mild sensory and moderate mobility impairments did not impact the interventions, as adjustments could be made. Furthermore, no cases of cybersickness were reported during both the procedure and the protocol.

From the pilot study, existential and spiritual themes were identified as an important aspect to consider for the 80+ age category. The main existential concepts identified for inclusion in the study were meaning and purpose in life, presence (being in the now), spirituality, agency, impact and legacy, all of which could be addressed through nature interactions. Additionally, interventions should be assessed for absorption (via a flow questionnaire) to comprehensively assess health and wellbeing outcomes. Focus groups for participants to share ideas on how to apply Complexity and Order in care settings (i.e., agency, impact and legacy) should be integrated. There are many opportunities to include high-fractal patterns (i.e., technologies, architectural features, furnishings, views) to inform the design of therapeutic care settings. Current interactions with nature at the facilities include animal therapy, a potting shed, and flower bouquet making, as well as biophilic design applications (plants, animals, nature patterns on furnishings, nature artworks). Further research should include the following:

- A larger sample size of 20+ participants for data generalisation, with a control group.

- Practical design interventions (Complexity and Order assessed in situ).

- Focus groups employed to provide a space to in which share ideas around nature in care settings, maximise agency, impact, and legacy, and reflect preferences.

- Further exploration of organised complexity for the application category of Nature of the Space (transitional spaces, mobility and wayfinding, perceptual coherence).

- Assessment of VR interventions in care settings for engagement and absorption, for which a flow/presence questionnaire could be employed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.T., Y.X., A.K. and D.J.B.; Investigation, C.T.; Supervision, Y.X., A.K. and D.J.B.; Writing—Review And Editing, C.T., Y.X. and A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by international funding from Nottingham Trent University, and by Innovate UK through the Knowledge Transfer Partnership KTP 10004608.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Schools of Art and Design, Arts and Humanities and Architecture, Design and the Built Environment Research Ethics Committee (AADH REC) (protocol code 1557295, 2025-02-21).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere thanks to Beaumond House Hospice Care and MHA Care Homes for their invaluable support in facilitating and enabling this research. Their dedication and collaboration have been essential to the successful delivery of the project. We also gratefully acknowledge Vieunite Ltd. and Allsee Ltd. for generously providing the digital canvases that made the visual and interactive components of this work possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Scoping review—methods employed for identified papers.

Table A1.

Scoping review—methods employed for identified papers.

| Article Number and Source | CS | SR | TA | NI | FG | RT | ED | PS | ES | PP | QL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 [39] | x | ||||||||||

| 2 [40] | x | ||||||||||

| 3 [41] | x | x | x | ||||||||

| 4 [42] | x | x | |||||||||

| 5 [43] | x | x | x | ||||||||

| 6 [44] | x | x | |||||||||

| 7 [45] | x | x | |||||||||

| 8 [46] | x | ||||||||||

| 9 [47] | x | x | |||||||||

| 10 [48] | x | ||||||||||

| 11 [10] | x | ||||||||||

| 12 [49] | x | x | |||||||||

| 13 [50] | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| 14 [18] | x | ||||||||||

| 15 [51] | x | ||||||||||

| 16 [52] | x | ||||||||||

| 17 [53] | x | ||||||||||

| 18 [54] | x | x | x | ||||||||

| 19 [55] | x | ||||||||||

| 20 [56] | x | ||||||||||

| 21 [57] | x | ||||||||||

| 22 [58] | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| 23 [59] | x | x | |||||||||

| 24 [60] | x | x | |||||||||

| 25 [61] | x | x | |||||||||

| 26 [62] | x | x | |||||||||

| 27 [63] | x | x | |||||||||

| 28 [64] | x | x | |||||||||

| 29 [65] | x | x |

CS = case studies; SR = systematic review; TA = thematic analysis; NI = narrative interviews; FG: focus groups; RT = randomised control trial; ED = experimental design; PS = pilot study; ES = existential or spiritual questionnaire/discussions; PP = pre- and post-measure intervention; QL = questionnaires (environmental/QOl).

Appendix B

Figure A1.

Nature Relatedness Outcomes.

Appendix C

Figure A2.

Consent Form.

Schools of Art and Design, Arts and Humanities and Architecture, Design and the Built Environment Research Ethics Committee (AADH REC). Ethics application number: 1557295.

References

- Ulrich, R.S. Biophilic Theory and Research for Healthcare Design; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285328585_Biophilic_theory_and_research_for_healthcare_design (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Xing, Y.; Stevenson, N.; Thomas, C.; Hardy, A.; Knight, A.; Heym, N.; Sumich, A. Exploring biophilic building designs to promote wellbeing and stimulate inspiration. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0317372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, Y.; Kar, P.; Bird, J.J.; Sumich, A.; Knight, A.; Lotfi, A.; van Barthold, B.C. Developing an AI-Based Digital Biophilic Art Curation to Enhance Mental Health in Intelligent Buildings. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Williams, A.; Knight, A. Developing a biophilic behavioural change design framework—A scoping study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 94, 128278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adityo, A. Role of Neuroscience and Artificial Intelligence in Biophilic Architectural Design Based on the Principle of Symbiosis. J. Artif. Intell. Arch. 2024, 3, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS. The Framework for Enhanced Health in Care Homes the Framework for Enhanced Health in Care Homes 2020/21-Version 2. 2020. NHS England—Enhanced Health in Care Homes Framework. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/enhanced-health-in-care-homes-framework/ (accessed on 29 March 2023).

- du Feu, M.; Fergusson, K. Sensory impairment and mental health. Adv. Psychiatr. Treat. 2003, 9, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS. ROAM II—Research on Outdoor Activities in Care Homes. Latest News Around Nottinghamshire Trust. Available online: https://www.nottinghamshirehealthcare.nhs.uk/latest-news/roam-ii-research-on-outdoor-activities-in-care-homes-2136 (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Yeo, N.; White, M.; Alcock, I.; Garside, R.; Dean, S.; Smalley, A.; Gatersleben, B. What is the best way of delivering virtual nature for improving mood? An experimental comparison of high definition TV, 360° video, and computer generated virtual reality. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 72, 101500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.J.; Park, S.J. A Framework of Smart-Home Service for Elderly’s Biophilic Experience. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrapin Bright Green. 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design. Available online: https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/reports/14-patterns/ (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Alves, S.; Gulwadi, G.B.; Nilsson, P. An Exploration of How Biophilic Attributes on Campuses Might Support Student Connectedness to Nature, Others, and Self. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 793175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salingaros, N.A. The Biophilic Index Predicts Healing Effects of the Built Environment introduction: Biophilia and its effects on people. JBU J. Biourbanism 2019, 8, 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lavdas, A.A.; Schirpke, U. Aesthetic preference is related to organized complexity. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.P.; Spehar, B.; Van Donkelaar, P.; Hagerhall, C.M. Perceptual and Physiological Responses to Jackson Pollock’s Fractals. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2011, 5, 10034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveday, L. Fractals: The Hidden Beauty and Potential Therapeutic Effect of the Natural World. Available online: www.magdalenfarm.org.uk (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Yu, C.-P.; Lee, H.-Y.; Lu, W.-H.; Huang, Y.-C.; Browning, M.H. Restorative effects of virtual natural settings on middle-aged and elderly adults. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 56, 126863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntsman, D.D.; Bulaj, G. Healthy Dwelling: Design of Biophilic Interior Environments Fostering Self-Care Practices for People Living with Migraines, Chronic Pain, and Depression. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Yeo, N.L.; Vassiljev, P.; Lundstedt, R.; Wallergård, M.; Albin, M.; Lõhmus, M. A prescription for “nature”—The potential of using virtual nature in therapeutics. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2018, 2018, 3001–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.-C.; Yang, Y.-H. The Long-term Effects of Immersive Virtual Reality Reminiscence in People With Dementia: Longitudinal Observational Study. JMIR Serious Games 2022, 10, e36720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Zhu, S.; MacNaughton, P.; Allen, J.G.; Spengler, J.D. Physiological and cognitive performance of exposure to biophilic indoor environment. Build. Environ. 2018, 132, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Yuan, J.; Arfaei, N.; Catalano, P.J.; Allen, J.G.; Spengler, J.D. Effects of biophilic indoor environment on stress and anxiety recovery: A between-subjects experiment in virtual reality. Environ. Int. 2020, 136, 105427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuda, Q.; Bougoulias, M.E.; Kass, R. Effect of nature exposure on perceived and physiologic stress: A systematic review. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 53, 102514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Yücel, M.A.; Tong, Y.; Minagawa, Y.; Tian, F.; Li, X. Editorial: FNIRS in neuroscience and its emerging applications. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 960591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzetoglu, K.; Bunce, S.; Izzetoglu, M.; Onaral, B.; Pourrezaei, K. fNIR spectroscopy as a measure of cognitive task load. In Proceedings of the 25th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Cancun, Mexico, 17–21 September 2003; pp. 3431–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, C.; Xu, G.; Li, W.; Xie, H.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. A review on functional near-infrared spectroscopy and application in stroke rehabilitation. Med. Nov. Technol. Devices 2021, 11, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Macura, B.; Whaley, P.; Pullin, A.S. ROSES Reporting standards for Systematic Evidence Syntheses: Pro forma, flow-diagram and descriptive summary of the plan and conduct of environmental systematic reviews and systematic maps. Environ. Evid. 2018, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M. The NR-6: A new brief measure of nature relatedness. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Haitsma, K.S. PELI-Nursing Home-MDS 3.0 Section F-Version 2.0. Preference Based Living. 2014. Available online: https://www.preferencebasedliving.com/for-practitioners/practitioner/assessment/peli-questionnaires/peli-nursing-home-mds-3-0-section-f-version-2-0/ (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A. The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule—Expanded Form; University of Iowa: Iowa City, IA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- eSense Skin Response: Stress Tracking Biofeedback Wearable with iOS/Android App. Available online: https://www.iphoneness.com/cool-finds/esense-skin-response/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Amazon.co.uk: Sports & Outdoors. Polar H10 Heart Rate Monitor—ANT Plus, Bluetooth—Waterproof HR Sensor with Chest Strap—Built-in memory, Software Updates (H10, M-XXL, Black). Available online: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Polar-Monitor-Bluetooth-Waterproof-Sensor/dp/B07PM54P4N/ref=asc_df_B07PM54P4N?tag=bingshoppinga21&linkCode=df0&hvadid=79989546378269&hvnetw=o&hvqmt=e&hvbmt=be&hvdev=c&hvlocint=&hvlocphy=41423&hvtargid=pla-4583589104859483&th=1&psc=1 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Mendi.io. The Mendi Headset. Available online: https://www.mendi.io/products/mendi (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Kjellgren, A.; Buhrkall, H. A comparison of the restorative effect of a natural environment with that of a simulated natural environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, M.H.E.M.; Mimnaugh, K.J.; van Riper, C.J.; Laurent, H.K.; LaValle, S.M. Can Simulated Nature Support Mental Health? Comparing Short, Single-Doses of 360-Degree Nature Videos in Virtual Reality with the Outdoors. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Vaart, W.; van Oudenaarden, R. The practice of dealing with existential questions in long-term elderly care. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2018, 13, 1508197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellehear, A.; Garrido, M. Existential ageing and dying: A scoping review. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2022, 104, 104798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder, W.D.; Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Csikszentmihalyi, I.S. Optimal Experience: Psychological Studies of Flow in Consciousness. Optim. Exp. 1989, 24, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, R. Working with the Elderly: An Existential—Humanistic Approach. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2009, 50, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ounalli, H.; Mamo, D.; Testoni, I.; Murri, M.B.; Caruso, R.; Grassi, L. Improving Dignity of Care in Community-Dwelling Elderly Patients with Cognitive Decline and Their Caregivers. The Role of Dignity Therapy. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittelson, S.; Scarton, L.; Barker, P.; Hauser, J.; O’MAhony, S.; Rabow, M.; Guay, M.D.; Quest, T.E.; Emanuel, L.; Fitchett, G.; et al. Dignity Therapy Led by Nurses or Chaplains for Elderly Cancer Palliative Care Outpatients: Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2019, 8, e12213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewe, F. The Soul’s Legacy: A Program Designed to Help Prepare Senior Adults Cope with End-of-Life Existential Distress. J. Health Care Chaplain. 2016, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.O.-Y.; Lo, R.; Chan, F.; Woo, J. A Pilot Study on the effectiveness of Anticipatory Grief Therapy for Elderly Facing the end of Life. J. Palliat. Care 2010, 26, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalding, M.; Khalsa, P. Aging Matters: Humanistic and Transpersonal Approaches to Psychotherapy with Elders with Dementia. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2010, 50, 142–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, K.G. Young clinicians dealing with death: Problems and opportunities. Palliat. Support. Care 2015, 14, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hațegan, V. The Practice of Counseling Between Philosophy and Spirituality, an Interdisciplinary Approach—ProQuest. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2501297425?accountid=14693 (accessed on 8 November 2023).

- Tong, A.; Cheung, K.L.; Nair, S.S.; Tamura, M.K.; Craig, J.C.; Winkelmayer, W.C. Thematic Synthesis of Qualitative Studies on Patient and Caregiver Perspectives on End-of-Life Care in CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2014, 63, 913–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, M.L.; Fernández, P.C. From the Suffering of Old Age to the Fullness of Senectitude, a Philosophical Approach. Philosophia 2022, 50, 2069–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, T.; Hua, H.; Gunasagaran, S.; Veronica, N.G.; Srirangam, S.; Kuppusamy, S. Biophilic Design for Elderly Homes in Malaysia for Improved Quality of Life. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2023, 18, 96–112. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, T.; Masser, B.; Pachana, N. Using indoor plants and natural elements to positively impact occupants of residential aged-care facilities. In Proceedings of the XXIX International Horticultural Congress on Horticulture: Sustaining Lives, Livelihoods and Landscapes (IHC2014), Brisbane, Australia, 17 August 2014; pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, T.; Verderber, S. Biophilic Design Strategies in Long-Term Residential Care Environments for Persons with Dementia. J. Aging Environ. 2021, 36, 227–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelen, L.; Rahmann, M.; de Jong, E. Design for healthy ageing—The relationship between design, well-being, and quality of life: A review. Build. Res. Inf. 2021, 50, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noone, S.; Innes, A.; Kelly, F.; Mayers, A. The nourishing soil of the soul’: The role of horticultural therapy in promoting well-being in community-dwelling people with dementia. Dementia 2015, 16, 897–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, T.L.; Jao, Y.-L.; Tulloch, K.; Yates, E.; Kenward, O.; Pachana, N.A. Well-Being Benefits of Horticulture-Based Activities for Community Dwelling People with Dementia: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreiros, C.; Veas, E.; Pammer, V. Bringing Nature into our Lives: Using Biophilic Design and Calm Computing Principles to Improve Well-Being and Performance; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 10902 LNCS, pp. 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verderber, S.; Koyabashi, U.; Dela Cruz, C.; Sadat, A.; Anderson, D.C. Residential Environments for Older Persons: A Comprehensive Literature Review (2005–2022). Sage J. 2023, 16, 291–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglass-Molloy, H.; Law, M.M.; Le, B.; Katz, N. Spiritual distress in dialysis: A case report. Prog. Palliat. Care 2022, 31, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderman, A.; Harstäde, C.W.; Östlund, U.; Blomberg, K. Community nurses’ experiences of the Swedish Dignity Care Intervention for older persons with palliative care needs—A qualitative feasibility study in municipal home health care. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2021, 16, e12372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, K. Depression-linked beliefs in older adults with depression. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 29, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundström, M.; Blomqvist, K.; Edberg, A.; Rämgård, M. The context of care matters: Older people’s existential loneliness from the perspective of healthcare professionals—A multiple case study. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2019, 14, e12234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, M.; Edberg, A.; Rasmussen, B.H.; Beck, I. Being acknowledged by others and bracketing negative thoughts and feelings: Frail older people’s narrations of how existential loneliness is eased. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2018, 14, e12213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, Z.; Oboyle, C. How specialist palliative care nurses identify patients with existential distress and manage their needs. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2019, 25, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Österlind, J.; Ternestedt, B.; Hansebo, G.; Hellström, I. Feeling lonely in an unfamiliar place: Older people’s experiences of life close to death in a nursing home. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2016, 12, e12129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormann, J.E.; Liu, L.; Thorp, S.R.; Lang, A.J. Spiritual wellbeing mediates PTSD change in veterans with military-related PTSD. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2011, 19, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pati, D.; Freier, P.; O’boyle, M.; Amor, C.; Valipoor, S. The Impact of Simulated Nature on Patient Outcomes. HERD: Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2015, 9, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).